A Comprehensive Guide to Alternative Splicing Analysis with Bulk RNA-Seq: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Applications

This article provides a complete roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals conducting alternative splicing (AS) analysis using bulk RNA sequencing.

A Comprehensive Guide to Alternative Splicing Analysis with Bulk RNA-Seq: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a complete roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals conducting alternative splicing (AS) analysis using bulk RNA sequencing. It covers the foundational biology of AS and its significance in disease and development, explores the landscape of computational tools and methodologies for detecting splicing variations, addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for robust experimental design, and outlines best practices for validation and comparative analysis. By integrating the latest methodological advancements and empirical findings, this guide aims to empower scientists to generate biologically accurate and clinically relevant insights from splicing data, ultimately advancing drug discovery and precision medicine.

Understanding Alternative Splicing: Biological Significance and Transcriptome Diversity

The central dogma of molecular biology outlines the flow of genetic information from DNA to RNA to protein. A critical, regulated juncture in this pathway is the processing of precursor messenger RNA (pre-mRNA) into mature mRNA, a process dominated by splicing. In eukaryotes, the majority of multi-exon genes do not produce a single mRNA transcript but undergo alternative splicing (AS), where different combinations of exons are joined to generate multiple distinct isoforms from a single gene locus [1]. This process, coupled with mechanisms like alternative polyadenylation (APA), dramatically expands the informational capacity of the genome, serving as a major driver of proteome diversity and functional complexity [2].

Understanding the principles governing AS is not merely an academic pursuit but a foundational element of modern molecular biology and therapeutic development. In humans, over 95% of multi-exon genes are subject to AS, and dysregulation of splicing is a hallmark of numerous diseases, including cancers and neurodegenerative disorders [3] [4]. For researchers and drug development professionals, analyzing AS patterns provides critical insights into cellular states, disease mechanisms, and potential therapeutic targets. This document frames the core principles and methodologies for AS analysis within the context of bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) research, providing a bridge from the fundamental mechanics of spliceosome action to the functional interpretation of proteomic outcomes.

Foundational Principles of Pre-mRNA Splicing and Regulation

2.1 The Spliceosome and Splicing Signals Pre-mRNA splicing is catalyzed by the spliceosome, a dynamic mega-dalton complex composed of five small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs) and numerous associated proteins [1]. Its function is to recognize specific conserved sequence motifs within the pre-mRNA:

- The 5′ splice site (donor site)

- The 3′ splice site (acceptor site)

- The branch point sequence

- The polypyrimidine tract [1] Through a series of coordinated assembly steps and transesterification reactions, the spliceosome excises introns and ligates adjacent exons to form the mature mRNA.

2.2 Modes of Alternative Splicing AS subverts constitutive splicing patterns to produce variant transcripts. The major canonical types include:

- Cassette Exon (Exon Skipping): The most common and highly conserved type in mammals, where an exon is either included or skipped [3].

- Alternative 5′ or 3′ Splice Sites: Selection of different donor or acceptor sites, lengthening or shortening an exon.

- Intron Retention (IR): The failure to remove an intron, which is particularly prevalent in plants and linked to stress responses, and also significant in mammalian systems like cell fate transitions [1] [5].

- Mutually Exclusive Exons: Selection of one exon from a pair or set, often encoding structurally distinct protein domains.

- Alternative First or Last Exons: Changes in transcription start or polyadenylation sites, altering the N- or C-terminus of the protein [2].

2.3 Cis and Trans Regulation of Splicing Choices The selection of splice sites is not automatic but is tightly regulated by a combination of cis-acting RNA sequence elements and trans-acting factors.

- Cis-Regulatory Elements: These include exonic splicing enhancers (ESEs), exonic splicing silencers (ESSs), and their intronic counterparts (ISEs and ISSs). They are short, degenerate sequences that serve as binding platforms for regulatory proteins [1].

- Trans-Acting Factors: The primary regulators are RNA-binding proteins (RBPs), most notably the Serine/Arginine-rich (SR) proteins and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs). SR proteins typically bind enhancers and promote exon inclusion by recruiting core spliceosomal components, while hnRNPs often bind silencers and promote exon exclusion [1] [3]. The dynamic balance and tissue-specific expression of these factors ultimately determine the splicing outcome, integrating signals from development, cellular stress, and disease states.

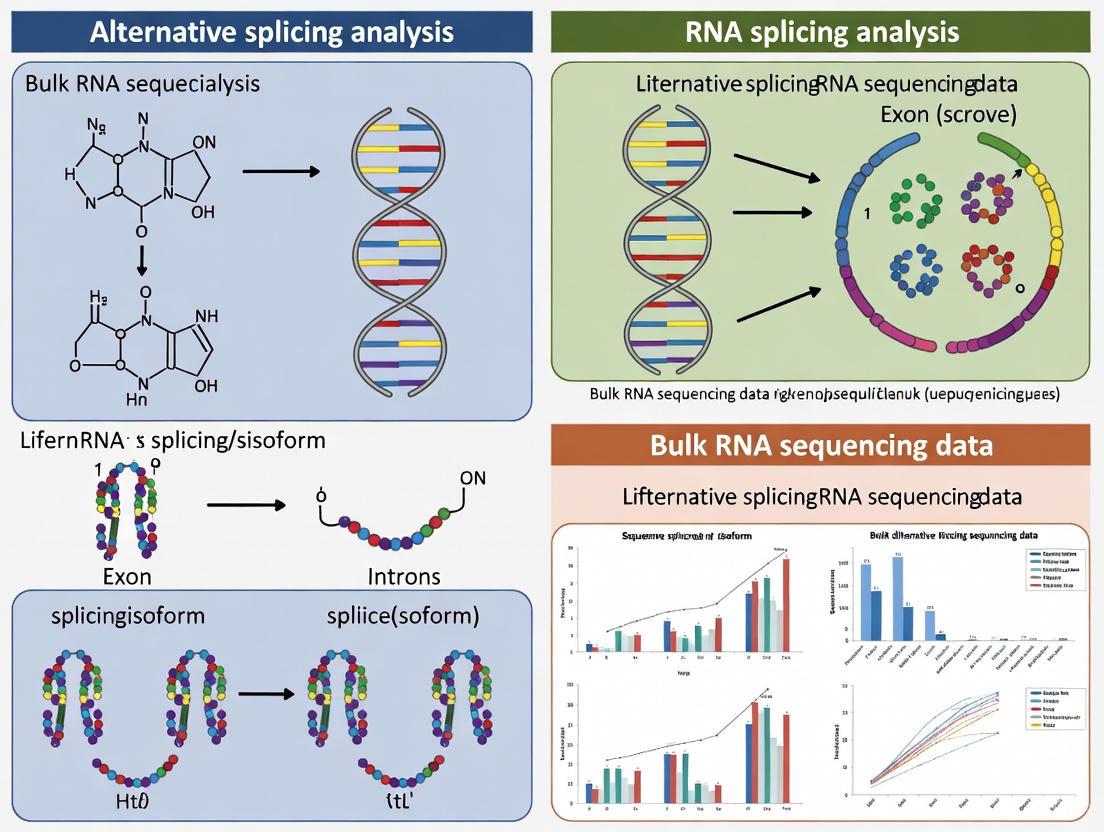

Diagram: Core Splicing Regulation Pathway

Technological and Computational Frameworks for Analysis

3.1 Sequencing Platforms for Splicing Detection Bulk RNA-seq is the cornerstone for transcriptome-wide AS analysis. The choice between short-read and long-read technologies presents a trade-off between scale, accuracy, and isoform resolution.

Table 1: Comparison of RNA Sequencing Platforms for AS Analysis [1] [6]

| Feature | Short-Read (e.g., Illumina) | Long-Read (PacBio HiFi) | Long-Read (Oxford Nanopore) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read Length | Short (50-300 bp) | Long (1-10+ kb) | Very Long (1-100+ kb) |

| Primary Template | cDNA | cDNA | cDNA or direct RNA |

| Base Accuracy | Very High (>99.9%) | Very High (HiFi >99.9%) | Moderate (~96-99%) |

| Key Strength | High quantitative power, low cost per base | Full-length isoform resolution with high accuracy | Direct RNA seq, detects modifications, extreme length |

| Key Limitation | Indirect isoform inference; misses complex loci | Higher cost, lower throughput than short-read | Higher error rate can complicate splice site mapping |

| Best for AS | Quantifying known AS events (Psi) across many samples | De novo isoform discovery, complex loci | Detecting RNA modifications affecting splicing, novel isoforms |

3.2 Computational Tools for AS Identification and Quantification Analyzing RNA-seq data to detect AS requires specialized computational tools that calculate metrics like Percent Spliced-In (PSI or Ψ), which quantifies the inclusion level of a particular exon or splice junction.

Table 2: Selected Computational Methods for AS Analysis from Bulk RNA-seq Data

| Tool Name | Primary Function | AS Events Detected | Key Principle / Approach | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rMATS | Differential AS analysis | SE, MXE, A5SS, A3SS, RI | Uses a hierarchical model on junction-spanning and exon reads to compare PSI between groups. | [2] |

| SUPPA2 | Differential AS & APA | Multiple AS events & APA | Calculates PSI from transcript expression; fast pattern generation across conditions. | [2] [7] |

| LeafCutter | Differential intron splicing | Intron clusters (splicing changes) | Identifies variable intron excision events without reliance on annotated splice sites. | [2] |

| MAJIQ | Quantification & visualization | Complex local splicing variations | Builds splicing graphs to model and quantify confidence in PSI changes. | [2] |

| Whippet | Differential AS analysis | Multiple AS events | Uses a lightweight probabilistic model leveraging gene annotation. | [2] |

3.3 Experimental Validation Protocols Findings from computational analysis must be validated with targeted molecular biology assays.

- Protocol 1: Semi-Quantitative RT-PCR for Isoform Detection

- Primer Design: Design primers in constitutive exons flanking the alternative region to amplify all isoforms.

- cDNA Synthesis: Use high-quality, DNase-treated RNA and reverse transcriptase with random hexamers or oligo-dT.

- PCR Amplification: Use a high-fidelity polymerase. Perform cycle titration to ensure amplification remains in the exponential phase for semi-quantitative comparison [1].

- Analysis: Separate products via agarose or polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Bands can be excised and sequenced for confirmation. For higher resolution, use capillary electrophoresis (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer) [1].

- Protocol 2: Digital Droplet PCR (ddPCR) for Absolute Isoform Quantification

- Assay Design: Design TaqMan probes or EvaGreen assays specific to each isoform (e.g., spanning an exon-exon junction unique to that isoform).

- Partitioning & PCR: The reaction mix is partitioned into ~20,000 nanoliter-sized oil droplets. Each droplet acts as an independent PCR reactor [1].

- End-Point Reading & Quantification: Droplets are read as positive or negative for fluorescence. Absolute copy numbers are calculated using Poisson statistics, without the need for a standard curve, offering high precision for low-abundance isoforms [1].

- Protocol 3: Minigene Splicing Reporter Assay

- Construct Cloning: Clone the genomic region of interest (containing the alternative exon and its flanking introns) into an exon-trapping vector between two constitutive exons.

- Transfection: Transfect the construct into relevant cell lines.

- RNA Isolation & Analysis: Isolve RNA 24-48 hours post-transfection and analyze splicing patterns via RT-PCR specific to the minigene transcript. This assay isolates the splicing regulation of a specific locus from genomic context [1].

Diagram: Bulk RNA-seq AS Analysis Workflow

From Splicing to Functional Proteome Consequences

4.1 Predicting and Modeling Structural Impacts The ultimate consequence of AS is a change in protein sequence, which can have profound effects on structure and function. Computational protein structure prediction tools like AlphaFold2 now enable systematic investigation of these impacts. Studies predicting structures for thousands of human splice isoforms reveal that AS can alter secondary structure composition, surface charge distribution, and protein compactness (radius of gyration) [4]. Crucially, AS often buries or exposes post-translational modification (PTM) sites, fundamentally altering regulatory potential. For example, alternative splicing of the BAX gene modulates exposure of phosphorylation sites, affecting its pro-apoptotic activity [4].

4.2 Functional Enrichment and Biological Interpretation To move from a list of differentially spliced genes to biological insight, functional enrichment analysis is essential. Genes undergoing AS during specific processes—like the fast chemical reprogramming (FCR) of somatic cells—are enriched in stage-specific pathways. In late FCR stages, spliced genes relate to ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, while in established induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), they are enriched in signaling pathways like mTOR and PI3K-Akt [5]. This indicates AS plays stage-specific regulatory roles. Similarly, cross-species analysis has identified AS events in genes related to stress response and neuronal function as being associated with maximum lifespan (MLS), suggesting a role for splicing in longevity [3].

4.3 Integration with Single-Cell and Spatial Context While bulk RNA-seq measures average splicing patterns, emerging technologies contextualize isoform expression. Long-read single-cell RNA-seq (e.g., Nanopore) allows isoform resolution at the cellular level, revealing cell-type-specific splicing and intra-cell isoform heterogeneity [8]. Integrating bulk-derived AS insights with single-cell atlases (e.g., Tabula Sapiens) can predict in which cell types a structurally distinct isoform is expressed, linking molecular form to cellular function [4].

Table 3: Summary of Key Experimental Validation Methods

| Method | Primary Application | Key Metric | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT-PCR / Capillary Electrophoresis | Detect & semi-quantify known isoforms. | Amplicon size / peak area. | Low-cost, rapid, high-specificity. | Low throughput; semi-quantitative. |

| Digital Droplet PCR (ddPCR) | Absolute quantification of specific isoforms. | Copies/μL of target isoform. | High precision, absolute quantification, no standard curve needed. | Low multiplexing; requires specific assay design. |

| Minigene / Splicing Reporter | Functional testing of cis-elements and trans-factors. | PSI from reporter transcript. | Isolates regulatory sequence; can test mutants. | May lack full genomic/chromatin context. |

Diagram: From Splicing Event to Functional Hypothesis

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Splicing Analysis

| Item | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality RNA Isolation Kits | Obtain intact, degradation-free RNA for accurate isoform representation. | Prioritize methods with effective DNase treatment and inhibitors of RNases. |

| Ribonuclease H (RNase H)-deficient Reverse Transcriptases | Generate full-length cDNA without degrading the RNA template during first-strand synthesis. | Essential for long amplicons in validation assays. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerases | Amplify cDNA for validation (RT-PCR) with minimal errors, ensuring accurate isoform sequence. | Critical for downstream sequencing of amplicons. |

| Spliceosome & RBP Inhibitors | Mechanistic studies (e.g., Pladienolide B for SF3B1). | Tools to perturb splicing and study immediate downstream effects. |

| Isoform-Specific Antibodies | Validate protein-level consequences of AS via western blot or immunofluorescence. | Rare; often require custom generation against isoform-unique peptides. |

| Long-Read Sequencing Kits | For full-length isoform discovery (PacBio) or direct RNA modification analysis (Nanopore). | Choice depends on need for accuracy vs. read length/modification detection [6]. |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines & Software | Align reads, quantify expression, identify and differentially test AS events (e.g., rMATS, SUPPA2). | Containerized versions (Docker/Singularity) ensure reproducibility [2]. |

| Splicing-Focused Databases | Query known isoforms, conservation, and tissue-specific patterns (e.g., VastDB, Ensembl). | Provide context for novel findings [5]. |

Alternative splicing (AS) is a fundamental post-transcriptional process that enables a single gene to produce multiple mRNA isoforms by differentially including or excluding exonic and intronic regions [9]. This mechanism is a major source of proteomic diversity and a critical regulator of development, tissue specificity, and cellular differentiation [10]. In humans, over 95% of multi-exon genes undergo alternative splicing [11], and its dysregulation is implicated in numerous diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and muscular dystrophies [12] [13].

The advent of bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has revolutionized the study of AS, providing a high-throughput, quantitative platform for discovering and quantifying splicing variations across biological conditions. Within the framework of a bulk RNA-seq research thesis, precise identification and quantification of splicing events—primarily exon skipping (ES), intron retention (IR), and alternative 5′/3′ splice site (ASSS) selection—are paramount. These events represent distinct mechanistic outcomes with unique biological implications and technical challenges for detection. This application note details the molecular basis, detection methodologies, and analytical protocols for these major splicing types, providing a practical guide for researchers and therapeutic developers.

Molecular Mechanisms and Biological Significance

Splicing is catalyzed by the spliceosome, a dynamic complex of small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs) and associated proteins that recognize conserved sequences at exon-intron boundaries: the 5′ splice site (SS), branch point sequence (BPS), polypyrimidine tract (PPT), and 3′ SS [10] [9]. The selection of these sites is regulated by cis-acting RNA elements (enhancers and silencers) and trans-acting RNA-binding proteins (e.g., SR proteins and hnRNPs), which together form a complex "splicing code" [11] [9].

Exon Skipping (ES), or cassette exon, is the most prevalent AS event in mammals [11] [9]. It involves the complete exclusion of an exon from the mature mRNA, along with its flanking introns. ES can lead to the loss of protein domains, affect protein-protein interactions, or cause a frameshift. It is a primary therapeutic target; for example, antisense oligonucleotides (AONs) are designed to skip exons harboring deleterious mutations in DMD to restore the reading frame in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) [12].

Intron Retention (IR) occurs when an intron is not removed and remains in the mature mRNA. It is the most common AS event in plants but less frequent in mammals, where it is often associated with nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) or regulation of gene expression [11] [9]. Retained introns can introduce premature termination codons or alter the protein's C-terminus if located in the final exon.

Alternative 5′ or 3′ Splice Site (ASSS) Selection involves the use of different donor (5′) or acceptor (3′) sites within an exon or intron. This leads to the extension or truncation of an exon, subtly altering the protein's coding sequence [11] [13]. The selection between competing splice sites is influenced by their intrinsic strength, the local concentration of splicing factors, and a competitive mechanism where nearby sites influence each other's usage [14].

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of these major event types.

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Alternative Splicing Events

| Event Type | Description | Prevalence in Humans | Potential Functional Impact | Therapeutic Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exon Skipping (ES) | Complete exclusion of an exon from the mature transcript. | ~30% of AS events; most common pattern [11]. | Domain loss, altered protein function, frameshift. | AONs (Eteplirsen) to skip exon 51 in DMD for DMD [12]. |

| Intron Retention (IR) | An intron remains in the final mRNA. | Less common; frequent in untranslated regions (UTRs) [11]. | Introduction of PTCs (leading to NMD), altered C-terminus, regulatory non-coding RNAs. | Targeted for degradation or modulation of gene expression levels. |

| Alt. 5′/3′ Splice Site (ASSS) | Use of alternative donor (5′) or acceptor (3′) sites. | ~25% of AS events [11]. | Subtle insertion/deletion in coding sequence, minor protein domain alteration. | Correction of cryptic splice site usage caused by deep-intronic mutations [13]. |

Detection and Quantification from Bulk RNA-Seq Data

Accurate analysis of AS from short-read bulk RNA-seq data involves specific computational strategies. The core metric for quantification is the Percent Spliced In (PSI or Ψ), which estimates the relative inclusion level of an exon, intron, or alternative splice site [15].

3.1. Computational Approaches and Tools Analysis pipelines can be categorized into splice-junction-centric and exon-centric methods. Junction-centric tools (e.g., rMATS, MAJIQ, LeafCutter) quantify reads spanning splice junctions to infer PSI. Exon-centric tools (e.g., DEXSeq) model reads covering exonic regions to test for differential usage. A significant advancement is the incorporation of exon-exon junction reads alongside exon counts, which resolves double-counting issues and enhances power, particularly for detecting ASS and IR events [16].

For large-scale or heterogeneous datasets (e.g., GTEx, TCGA), tools like MAJIQ v2 are essential. It employs a Local Splicing Variation (LSV) framework that captures complex events and unannotated junctions, and uses a Bayesian model to quantify PSI and confidence intervals. Its "HET" module applies non-parametric tests to handle sample heterogeneity effectively [15].

3.2. Performance of Detection Methods The choice of tool significantly impacts detection capability. Benchmarking studies show that methods incorporating junction information (DEJU) outperform traditional exon-only (DEU) approaches [16].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Splicing Detection Methods for Different Event Types [16]

| Splicing Event Type | Key Challenge in Detection | Recommended Method (High Power & Controlled FDR) | Method with Notable Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exon Skipping (ES) | Distinguishing skipping from constitutive exon. | DEJU-edgeR/limma, rMATS, MAJIQ v2. | Basic DEXSeq (lower power for complex genes). |

| Intron Retention (IR) | Differentiating true retention from pre-mRNA contamination or reads from unprocessed RNA. | MAJIQ v2, DEJU-edgeR/limma (specifically designed for IR). | Most standard DEU workflows (fail to detect IR) [17]. |

| Alt. Splice Site (ASSS) | Identifying subtle changes in exon boundaries. | DEJU-edgeR/limma, MAJIQ v2 (LSV framework). | Exon-only DEU approaches (lack junction resolution). |

3.3. Visualization of Splicing Analysis Workflow The following diagram illustrates a generalized computational workflow for differential splicing analysis from raw RNA-seq reads to biological insight, integrating steps from alignment, quantification, statistical testing, and visualization.

Diagram Title: Computational Workflow for Differential Splicing Analysis

Detailed Experimental and Analytical Protocols

4.1. Protocol: Validating Exon Skipping Using RT-PCR and Sequencing This protocol is used to experimentally confirm in silico predictions of exon skipping, common in therapeutic development for diseases like DMD [12].

- RNA Isolation & QC: Extract total RNA from treated and control cells/tissues using TRIzol. Assess integrity (RIN > 8.0) via Bioanalyzer.

- cDNA Synthesis: Perform reverse transcription using 1 µg of total RNA, oligo(dT) primers, and a reverse transcriptase.

- PCR Amplification: Design primers in the exons flanking the predicted skipped exon. Perform PCR with a high-fidelity polymerase. Include a control amplifying a constitutively spliced gene.

- Gel Electrophoresis: Resolve PCR products on a 2-3% agarose gel. The skipped isoform will produce a smaller band than the full-length product.

- Purification & Sequencing: Excise gel bands, purify the DNA, and perform Sanger sequencing to confirm the exact junction.

4.2. Protocol: Differential Splicing Analysis with MAJIQ v2 on a Large Dataset This protocol is designed for robust analysis of heterogeneous data across many samples, such as different brain regions or cancer subtypes [15].

- Data Preparation: Compile BAM alignment files for all samples. Prepare a sample table defining group affiliations (e.g., condition, tissue).

- Build Splice Graphs: Run the MAJIQ builder to create a unified splice graph for each gene, incorporating annotated and de novo junctions.

- Quantify Splicing Variations: Run the MAJIQ quantifier to compute PSI (Ψ) distributions for all LSVs in each sample group.

- Identify Differential LSVs: Apply the MAJIQ HET test to identify LSVs with significant ΔPSI between groups (e.g., |ΔΨ| > 0.2, probability > 0.95).

- Visualize Results: Use VOILA v2 to visualize complex splicing events, generating splice graphs and posterior distribution plots for top hits.

4.3. Protocol: Targeted Analysis of Alternative Splice Sites via Amplicon-Seq This protocol is useful for deep investigation of specific ASS events predicted by tools like those in [14] or for screening patient variants.

- Design Amplification Strategy: Design long-range PCR primers to amplify the genomic region encompassing the alternative exon and its flanking constitutive exons.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Amplify the region from cDNA, prepare an Illumina amplicon library, and perform paired-end 2x150 bp or 2x250 bp sequencing for sufficient junction overlap.

- Mapping & Junction Analysis: Map reads to the reference genome using a sensitive aligner (e.g., BWA-MEM). Extract and count all unique splice junction combinations.

- Quantify Site Usage: Calculate the PSI for each competing 5' or 3' splice site by dividing its junction read count by the sum of all junction reads for that alternative splicing event.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Splicing Research

| Item | Function / Description | Example Use Case / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Splice-Aware Aligner | Aligns RNA-seq reads across splice junctions. | STAR [16] or HISAT2 for generating BAM files for downstream analysis. |

| Splicing Quantification Software | Quantifies PSI and detects differential splicing. | MAJIQ v2 [15] for complex/heterogeneous data; rMATS for standard case-control studies. |

| Antisense Oligonucleotides (AONs) | Chemically modified RNAs/DNAs that bind pre-mRNA to modulate splicing. | Induce exon skipping (Eteplirsen for DMD) [12] or block cryptic splice sites. |

| U7 snRNA Vector System | Engineered snRNA for sustained in vivo expression of antisense sequences. | Used in recombinant AAV vectors for long-term exon skipping therapy in muscle [12]. |

| Splicing Reporter Minigenes | Plasmid constructs containing a genomic region of interest cloned into an exon-intron-exon reporter. | Validate the impact of genetic variants or ASOs on splicing patterns in vitro [13]. |

| RT-PCR Reagents & Gel Electrophoresis | Standard molecular biology tools for isoform detection. | Rapid, low-cost validation of major splicing changes (e.g., exon skipping) [12]. |

The precise analysis of exon skipping, intron retention, and alternative splice site usage is a cornerstone of modern transcriptomics and a critical component of a bulk RNA-seq research thesis. The integration of sophisticated computational tools like MAJIQ v2 [15] and DEJU [16] with targeted experimental validation provides a robust framework for discovering disease-relevant splicing dysregulation.

The translational impact is profound. Exon skipping therapies for DMD exemplify successful "splice-switching," with approved AONs and advanced AAV-U7snRNA vectors in clinical trials [12]. Furthermore, the systematic annotation of splice-disruptive variants is enhancing diagnostic yield and revealing new targets for RNA-targeted therapies in neurological and other disorders [13]. As long-read sequencing and single-cell technologies mature, they will further refine our understanding of splicing diversity. However, bulk RNA-seq remains essential for its cost-effectiveness, statistical power in cohort studies, and well-established analytical pipelines, continuing to be an indispensable tool for researchers and drug developers aiming to decode and manipulate the splicing code for therapeutic benefit.

The Critical Role of Splicing in Development, Cell Differentiation, and Disease

Biological Context and Analytical Imperative

Alternative splicing (AS) is a fundamental post-transcriptional regulatory mechanism, affecting over 90% of multi-exon human genes and enabling a limited genome to produce a vast diversity of protein isoforms [8]. In development, precise splicing patterns dictate cell fate determination and lineage specification. During differentiation, splicing shifts remodel the cellular proteome to support specialized functions. Dysregulation of this precise control is a hallmark of disease; aberrant splicing contributes directly to pathologies including cancer, intellectual disability, and autism spectrum disorders [8].

Bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) remains a cornerstone for profiling these splicing dynamics across tissues and patient cohorts. It provides a population-average view essential for identifying consistent splicing signatures associated with biological states or clinical outcomes. The core analytical challenge lies in accurately quantifying transcript isoforms from short sequencing reads that may ambiguously map to multiple splice variants [18]. Moving from gene-level expression to isoform-resolution analysis is therefore critical for a mechanistic understanding of how splicing influences biology and disease.

Foundational Analytical Framework for Splicing from Bulk RNA-seq

A robust analysis of alternative splicing from bulk RNA-seq data requires a multi-step computational workflow designed to handle uncertainty in read assignment and quantify splice variant abundance.

Core Workflow Steps:

- Read Alignment & Quantification: Sequencing reads are aligned to a reference genome using a splice-aware aligner (e.g., STAR). Subsequently, tools like Salmon or RSEM perform transcript-level quantification, using statistical models to resolve the uncertainty when reads map to multiple isoforms [18].

- Splicing Event Identification: Quantified transcripts are analyzed to detect specific types of splicing events (e.g., exon skipping, alternative 5'/3' splice sites).

- Differential Splicing Analysis: Statistical testing is applied to identify events whose usage (e.g., Percent Spliced In, PSI) changes significantly between experimental conditions or patient groups.

The following workflow diagram outlines this generalized pipeline for differential splicing analysis.

Diagram: Bulk RNA-seq Splicing Analysis Workflow.

Experimental Protocol: Splicing-Focused Bulk RNA-seq Library Preparation and Sequencing

This protocol details the steps for generating sequencing libraries suitable for alternative splicing analysis from total RNA [19] [18].

Materials and Equipment

- Total RNA samples (RIN > 8.0 recommended).

- Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Kit (e.g., NEBNext) [19].

- RNA-seq Library Prep Kit for Illumina (e.g., NEBNext Ultra II).

- SPRIselect Beads or equivalent for size selection and clean-up.

- Thermal cycler, magnetic stand, and microcentrifuge.

- High-sensitivity DNA assay (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer).

- Illumina sequencing platform (e.g., NextSeq, NovaSeq).

Step-by-Step Procedure

A. mRNA Enrichment and Fragmentation

- Isolate polyadenylated mRNA from 50 ng – 1 µg of total RNA using poly(A) magnetic beads. This step depletes ribosomal RNA.

- Elute the purified mRNA in nuclease-free water.

- Fragment the mRNA using divalent cations under elevated temperature (e.g., 94°C for 5-15 minutes) to generate fragments of 200-300 base pairs.

B. First and Second Strand cDNA Synthesis

- Synthesize first-strand cDNA using random hexamer priming and reverse transcriptase.

- Synthesize the second-strand cDNA using DNA Polymerase I and RNase H, creating double-stranded cDNA.

C. Library Construction

- End Repair/A-Tailing: Repair fragment ends and add a single 'A' nucleotide to the 3' ends to facilitate adapter ligation.

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate indexed sequencing adapters with a single 'T' overhang to the cDNA fragments.

- Library Amplification: Perform 8-12 cycles of PCR to enrich for adapter-ligated fragments and incorporate full-length adapter sequences.

D. Quality Control and Pooling

- Clean the amplified library using SPRIselect beads at a 0.8x-1.0x bead-to-sample ratio to remove short fragments and reactants.

- Quantify the final library using a fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit) and assess the size distribution via Bioanalyzer. Expect a peak at ~300-400 bp.

- Pool equimolar amounts of uniquely indexed libraries for multiplexed sequencing.

E. Sequencing

- Sequence the pooled library on an Illumina platform. For optimal splicing analysis, use paired-end sequencing (e.g., 2x150 bp) to generate reads long enough to span splice junctions [18].

Computational Tools for Splicing Analysis: A Comparative Guide

A wide array of computational tools has been developed to detect and quantify alternative splicing events from RNA-seq data. They can be broadly categorized by their primary function and methodological approach [2].

Table 1: Computational Tools for Alternative Splicing Analysis from Bulk RNA-seq Data

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Method/Approach | Key Strength | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rMATS | Differential AS detection | Uses a hierarchical model to compare splice junction counts. | Models biological variance; handles replicates well. | [2] |

| SUPPA2 | Differential AS & APA | Calculates PSI from transcript expression; fast profiling. | High speed; integrates alternative polyadenylation. | [2] |

| LeafCutter | Differential intron splicing | Clusters intron excision events without prior annotation. | Detects novel and complex splicing events. | [2] |

| MAJIQ | Quantification & differential AS | Builds local splice graphs to model complex splicing variations. | Resolves complex splicing variations effectively. | [2] |

| DEXSeq | Differential exon usage | Tests for differential usage of exonic bins between conditions. | Generalizable to any genomic feature. | [2] |

The analysis can target seven major types of alternative splicing events, each with distinct functional consequences for the resulting mRNA and protein.

Diagram: Major Types of Alternative Splicing Events.

Successful splicing analysis relies on both wet-lab reagents and bioinformatic resources. The following table details key solutions.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Splicing Analysis

| Category | Item / Solution | Function & Importance | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab | Poly(A) mRNA Selection Beads | Enriches for mature, polyadenylated mRNA, removing rRNA that would dominate sequencing. | NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Beads [19]. |

| Wet-Lab | Stranded Library Prep Kit | Preserves strand-of-origin information, crucial for accurate transcript annotation and splicing detection. | Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep. |

| Wet-Lab | High-Fidelity Polymerase | Reduces PCR errors during library amplification, ensuring sequence fidelity for variant detection. | Q5 Hot Start Polymerase. |

| Bioinformatic | Splice-Aware Aligner | Aligns RNA-seq reads across splice junctions by allowing gaps in the alignment. | STAR, HISAT2 [18]. |

| Bioinformatic | Transcript Quantifier | Estimates isoform abundance from aligned reads, resolving multimapping ambiguity. | Salmon (alignment-based mode), RSEM [18]. |

| Bioinformatic | Splicing Analysis Tool | Performs statistical testing for differential splicing between sample groups. | rMATS, SUPPA2 (see Table 1) [2]. |

| Reference | High-Quality Annotation | Provides a reference set of known transcripts and splice junctions for quantification. | GENCODE, Ensembl GTF files. |

From Analysis to Therapeutic Insight

Integrating splicing analysis into a broader research thesis provides a direct path to mechanistic and translational discovery. In cancer research, identifying tumor-specific splice variants (neoantigens) can reveal novel therapeutic targets and immunotherapies. For neurodevelopmental disorders, elucidating splicing dysregulation in genes like RBFOX or MECP2 can pinpoint critical windows for intervention.

The emerging integration of single-cell and spatial long-read sequencing, as exemplified by tools like Longcell which addresses UMI recovery and isoform quantification challenges [8], promises to map splicing heterogeneity within tissues. This refines our understanding from population averages to cellular microenvironments, revealing how splicing contributes to cell fate decisions in development or tumor microevolution in disease. Ultimately, the systematic application of these bulk RNA-seq protocols and analytical frameworks is foundational for dissecting the critical role of splicing across biology and advancing RNA-targeted therapeutics.

The Central Role of Alternative Splicing in Human Disease and Therapy

Alternative splicing (AS) is a fundamental post-transcriptional mechanism through which a single gene can generate multiple mRNA isoforms, leading to proteomic diversity. Recent analyses indicate that approximately 95% of human multi-exon genes undergo alternative splicing [20]. This process is not merely a source of diversity; its dysregulation is a direct contributor to disease pathogenesis. It is estimated that 15-50% of human genetic diseases involve mutations that disrupt normal splicing patterns, affecting everything from core splice sites to splicing regulatory elements (SREs) [20] [21]. Consequently, the precise patterns of splicing in a tissue or cell type are not just molecular noise but are rich sources of disease-specific targets and clinically actionable biomarkers.

In cancer, for instance, splicing dysregulation can create isoforms that drive tumorigenesis, promote metastasis, or confer drug resistance. The splicing factor/binding site axis represents a promising but complex therapeutic frontier. As evidenced by the development of splicing modulator compounds (SMCs) like BPN-15477, targeted correction of pathogenic splicing is a viable therapeutic strategy [22]. This compound was shown to correct aberrant splicing in the ELP1 gene linked to familial dysautonomia and was predicted via a deep learning model to be capable of correcting splicing defects in 155 other disease genes [22]. For drug discovery professionals, this underscores a dual opportunity: splicing variants can be the therapeutic target themselves, or their unique expression profiles can serve as biomarkers for patient stratification, treatment response, and disease monitoring.

Computational Landscape for Splicing Analysis from Bulk RNA-Seq

The advent of high-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has been transformative for splicing analysis. Bulk RNA-seq analysis of splicing has evolved from quantifying known isoforms to detecting complex, unannotated local splicing variations (LSVs) across heterogeneous sample sets. The core metric for quantification is the Percent Spliced In (PSI or Ψ) value, which measures the relative inclusion of an exon or junction [15].

A critical challenge in the field is the accurate analysis of large-scale, heterogeneous datasets (e.g., from consortia like GTEx). Traditional tools that assume homogeneous sample groups often fail or lose power with such data. Next-generation pipelines like MAJIQ v2 address this by introducing heterogeneous (HET) test statistics that quantify PSI per sample before group comparison, enhancing robustness and power [15]. Furthermore, tools must grapple with transcriptome complexity, where a significant fraction of splicing variations involve unannotated junctions or complex patterns not captured by simple event types [15] [23].

Table 1: Common Types of Alternative Splicing Events and Their Features

| Splicing Event Type | Description | Approximate Frequency in Humans [20] | Potential Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exon Skipping (ES) | An exon is either included or skipped in the mature mRNA. | ~38.4% (Most common) | Can lead to loss or gain of protein domains, altering function or stability. |

| Alternative 3' Splice Site (A3SS) | Selection between different splice sites at the 3' end of an upstream exon. | ~18.4% | Changes the C-terminal boundary of an upstream exon, potentially affecting protein sequence. |

| Alternative 5' Splice Site (A5SS) | Selection between different splice sites at the 5' end of a downstream exon. | ~7.9% | Changes the N-terminal boundary of a downstream exon. |

| Intron Retention (IR) | An intron is retained in the mature transcript. | ~2.8% | Often introduces a premature termination codon (PTC), leading to nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) or a protein with an inserted sequence. |

| Mutually Exclusive Exons (MXE) | One of two adjacent exons is included, but never both. | Part of ~32.4% "Other" | Provides a switch between two distinct protein modules. |

Table 2: Selected Computational Tools for Bulk RNA-seq Splicing Analysis

| Tool Name | Core Methodology | Key Strength | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAJIQ v2 [15] | Bayesian modeling of Local Splicing Variations (LSVs); HET non-parametric tests. | Handles large, heterogeneous datasets; detects complex & de novo events. | Large cohort studies (e.g., GTEx), differential splicing across many conditions. |

| rMATS [24] | Statistical modeling of reads spanning junction pairs for defined event types. | High precision for classical event types; widely used and validated. | Standard differential splicing analysis between controlled experimental groups. |

| SpliceSeq [25] | Alignment to splice graphs; functional consequence prediction. | Intuitive visualization; links splicing changes to protein function via UniProt. | Prioritizing splicing events with likely functional, pathogenic impact. |

| AStalavista [23] | Systematic identification and categorization of AS events from annotation. | Provides a universal "AS code" nomenclature; characterizes full splicing landscape. | Categorizing and comparing global splicing patterns across annotations or species. |

| IRFinder [24] | Specialized quantification of intron retention from RNA-seq. | High accuracy for detecting and quantifying IR events. | Studies where intron retention is a key focus (e.g., some cancers, viral infection). |

Application Note 1: Protocol for Differential Splicing Analysis in Drug Response Studies

Objective: To identify splicing alterations associated with drug treatment or resistance using bulk RNA-seq data from cell lines or patient-derived samples.

Experimental Design:

- Sample Groups: Include treated vs. untreated controls, isogenic sensitive vs. resistant cell lines, or patient pre- vs. post-treatment samples. Minimum 3-4 biological replicates per group is strongly recommended.

- RNA-seq Library Preparation: Use poly-A selection to enrich for mature mRNA. Paired-end sequencing (e.g., 2x150 bp) with a depth of 50-100 million reads per sample is standard for splicing analysis to ensure sufficient junction coverage.

- Controls: Spike-in RNA controls (e.g., ERCC) can help monitor technical variance.

Bioinformatics Protocol (Using MAJIQ v2 as an example):

- Read Alignment and Preprocessing:

- Align reads to the human reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) using a splice-aware aligner like STAR.

- Process aligned BAM files: sort, index, and optionally remove duplicates.

- Build Splicing Graphs:

- Run

majiq buildwith a reference transcript annotation (e.g., GENCODE). This creates a splice graph for each gene, incorporating known and de novo detected junctions. For incremental analysis of large projects, MAJIQ v2 allows adding new samples without rebuilding from scratch [15].

- Run

- Quantify Splicing Variations:

- Run

majiq quanton your sample groups. This calculates the PSI (Ψ) and its posterior distribution for every Local Splicing Variation (LSV) in each sample/group. For heterogeneous data, specify the--hetflag to use sample-wise quantification.

- Run

- Identify Differential Splicing (DS):

- Run

majiq deltapsito compare groups (e.g., treated vs. control). This calculates ΔPSI (change in PSI) and the probability that |ΔPSI| > a threshold (e.g., 0.2 or 20%). Output is a list of LSVs with significant changes.

- Run

- Visualization and Interpretation:

- Use VOILA v2 (the companion visualizer for MAJIQ) to inspect significant LSVs. It can generate simplified splice graphs showing PSI across groups for hundreds of samples [15].

- Integrate gene ontology (GO) analysis on genes with significant DS events to identify enriched biological pathways affected by the drug.

Key Consideration: Always plan for experimental validation of top hits using an orthogonal method such as RT-PCR with capillary electrophoresis or nanostring nCounter on independent samples.

Application Note 2: Protocol for Identifying Splicing-Derived Biomarkers

Objective: To discover and prioritize tissue- or disease-specific splicing variants as potential diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers.

Workflow Overview:

- Discovery Cohort Analysis: Perform differential splicing analysis (as in Protocol 3.1) on a well-powered cohort comparing disease vs. normal tissues. Focus on events with large ΔPSI magnitude and high statistical significance.

- Prioritization Filter:

- Specificity: Prioritize events that are tissue-specific or show minimal variation in normal tissues [20]. Tools like MAJIQ v2's "Modulizer" can help classify events [15].

- Function: Use annotation (e.g., via SpliceSeq [25]) to prioritize events that alter critical protein domains, active sites, or structured motifs.

- Detectability: Favor events where the splice junction boundaries are amenable to detection by qPCR, droplet digital PCR (ddPCR), or targeted RNA-seq assays.

- Biomarker Assay Development:

- Design junction-spanning TaqMan assays or amplicon-seq probes specific to the biomarker isoform.

- Optimize assay using a training set of samples.

- Validation: Test the biomarker assay on a large, independent validation cohort of patient samples, linking the splicing signature to clinical outcomes (e.g., survival, therapy response).

Diagram 1: Workflow for Splicing Biomarker Discovery & Validation

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Splicing Studies

| Category | Item / Resource | Function in Splicing Research | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Poly-A Selection Beads | Isolate mature, poly-adenylated mRNA from total RNA for RNA-seq library prep. | Essential for standard RNA-seq protocols to focus on spliced transcripts. |

| Ribonuclease H (RNase H) | Used in assays to specifically degrade RNA in DNA-RNA hybrids (R-loops), which can influence splicing. | Useful for studying R-loop mediated splicing regulation. | |

| Splicing Modulator Compounds (SMCs) | Small molecules that bind the spliceosome or splicing factors to influence splice site choice. | BPN-15477 [22]; tools for mechanistic studies & therapeutic leads. | |

| Molecular Tools | Minigene Splicing Reporters | Plasmid-based systems containing a genomic region of interest to study splicing regulation in vivo. | Critical for validating the impact of mutations or SREs on splicing [21]. |

| Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs) | Chemically modified oligonucleotides that bind pre-mRNA to block or enhance splice site usage. | Used for functional validation and as a therapeutic modality (e.g., Nusinersen for SMA). | |

| Clontech SMARTER cDNA Kits | Generate high-quality cDNA from low-input RNA for isoform-specific PCR validation. | For validating RNA-seq findings via RT-PCR. | |

| Computational Resources | SpliceAid-F / SpliceAid 2 | Database of experimentally validated splicing factor binding motifs and sites [21]. | Predicts SREs and interprets the effect of sequence variants. |

| Ensembl / GENCODE Annotation | Comprehensive, regularly updated transcript annotation for the human genome. | Provides the reference "splice graph" for alignment and quantification. | |

| GTEx Portal | Repository of normal tissue RNA-seq data. | Serves as a critical baseline for assessing tissue-specificity of splicing events. |

Advanced Frontiers: Integrating Splicing Analysis into Target Discovery

The future of splicing in drug discovery lies in integration and precision. Key frontiers include:

- Single-Cell Splicing Resolution: New computational frameworks like SCSES (2025) are overcoming the sparsity of scRNA-seq data to impute reliable PSI values, allowing the mapping of splicing heterogeneity within tumors and its correlation with drug-resistant cell states [24]. This can reveal rare, targetable subpopulations.

- AI-Driven Target Prediction: As demonstrated with BPN-15477, deep learning models (e.g., CNNs) trained on RNA-seq data from SMC-treated cells can identify responsive sequence signatures [22]. These models can then scan databases like ClinVar to predict which patient mutations are correctable by a given SMC, enabling a precision medicine approach.

- Integrative Multi-Omics: Combining splicing data with genetic variants (e.g., eQTLs for splicing - sQTLs), chromatin accessibility (ATAC-seq), and RBP binding (CLIP-seq) can elucidate the full regulatory network governing a pathogenic splicing event, revealing upstream therapeutic nodes.

Diagram 2: Therapeutic Targeting of a Splicing-Centric Disease Pathway

Concluding Synthesis

The systematic analysis of alternative splicing through bulk RNA-seq has matured from a basic research activity to a cornerstone of modern therapeutic discovery. The protocols and frameworks outlined here enable researchers to transition from identifying splicing correlates of disease to validating causal splicing targets and developing robust isoform-specific biomarkers. The integration of sophisticated computational tools (like MAJIQ v2 for bulk, SCSES for single-cell) with experimental validation creates a powerful pipeline for translating splicing biology into novel clinical assets. As the field progresses, the convergence of deep learning, single-cell genomics, and targeted splicing therapeutics promises to unlock a new class of precision medicines for a wide array of genetically defined disorders.

Bulk RNA-Seq as a Key Tool for Transcriptome-Wide Splicing Profiling

Bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) is a foundational technology for transcriptome-wide profiling of gene expression and, crucially, for the systematic analysis of alternative splicing (AS) [26]. By sequencing RNA from a population of cells, it provides an averaged but comprehensive snapshot of the transcriptome, enabling the identification and quantification of diverse RNA isoforms produced from a single gene locus [2]. Within a broader thesis on alternative splicing analysis, bulk RNA-Seq serves as the primary, high-throughput discovery tool. It allows researchers to detect splicing variations across different biological conditions—such as disease states, developmental stages, or drug treatments—on a genome-wide scale [15]. The ability to profile splicing in a transcriptome-wide manner is critical for understanding the complex regulatory networks underlying cellular differentiation, homeostasis, and disease pathogenesis, including cancer and autoimmune disorders [27] [28].

The analysis of alternative splicing via bulk RNA-Seq involves specific computational and statistical challenges distinct from differential gene expression analysis. The goal is to accurately quantify shifts in the relative abundance of mRNA isoforms. This is typically measured by metrics like the Percent Spliced In (PSI or Ψ), which represents the proportion of transcripts that include a particular exon or splice junction [15]. The power of bulk RNA-Seq in this context is its scalability and cost-effectiveness for profiling large sample cohorts, which is essential for achieving the statistical power needed to detect subtle but biologically significant splicing changes [29]. As part of an integrated analytical thesis, findings from bulk RNA-Seq often form the hypothesis-generating bedrock, which can be further validated with targeted assays or explored at single-cell resolution [27] [30].

Quantitative Foundations of Splicing Analysis

Catalog of Alternative Splicing Events

Alternative splicing generates transcriptomic diversity through several canonical patterns. The table below defines the primary AS event types analyzed in bulk RNA-Seq data and their functional implications [2].

Table 1: Primary Types of Alternative Splicing Events Detectable by Bulk RNA-Seq

| Event Type | Description | Key Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Exon Skipping (Cassette Exon) | The complete inclusion or exclusion of an exon in the mature mRNA. | Most common in mammals; can lead to loss/gain of protein domains. |

| Alternative 5' Splice Site (Alt 5'SS) | Selection between different donor splice sites at the 5' end of an intron. | Alters the N-terminal boundary of the upstream exon. |

| Alternative 3' Splice Site (Alt 3'SS) | Selection between different acceptor splice sites at the 3' end of an intron. | Alters the C-terminal boundary of the downstream exon. |

| Mutually Exclusive Exons | Two or more exons are used in a mutually exclusive manner. | Provides structurally distinct protein variants. |

| Intron Retention | An intron remains in the mature mRNA instead of being spliced out. | Often leads to nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) or truncated proteins. |

Statistical Power and Sample Size Considerations

Detecting differential splicing with confidence requires careful experimental design. The following table outlines key parameters influencing statistical power, drawing from large-scale benchmarking studies [29] [31].

Table 2: Parameters Influencing Statistical Power for Differential Splicing Detection

| Parameter | Recommended Practice | Rationale and Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Replicates | Minimum of 3-4 per condition; 6-8 for robust detection of subtle changes. | Accounts for natural biological variation; essential for reliable statistical testing [31]. |

| Sequencing Depth | Typically 30-50 million paired-end reads per sample for mammalian genomes. | Ensures sufficient coverage across splice junctions for accurate PSI quantification. |

| Read Length | Paired-end reads (e.g., 2x100 bp or 2x150 bp) are strongly recommended. | Provides better alignment accuracy across splice junctions and isoform resolution [18]. |

| Effect Size (ΔPSI) | Studies should be powered to detect a minimum ΔPSI of 0.1-0.2 (10-20%). | Smaller effect sizes require substantially more replicates to distinguish from technical noise [29]. |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Aim for high SNR through quality library prep and sequencing. | Low SNR drastically reduces the ability to detect true biological differences, especially with subtle effects [29]. |

Computational Tools for Splicing Quantification

A wide array of specialized software tools has been developed to identify and quantify AS events from bulk RNA-Seq alignment files. The selection of a tool depends on the specific analysis goals [2] [15].

Table 3: Selected Computational Tools for Alternative Splicing Analysis from Bulk RNA-Seq

| Tool Name | Core Methodology | Key Feature | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAJIQ/VOILA [15] | Quantifies Local Splicing Variations (LSVs) and PSI using a Bayesian framework. | Handles complex, unannotated events; excellent for large, heterogeneous datasets. | Discovery-based analysis of complex splicing across many samples/conditions. |

| SUVA [28] | Detects and quantifies five types of AS events using splice junction reads. | Calculates the ratio of alternatively spliced to constitutively spliced reads (pSAR). | Focused analysis of canonical AS event types. |

| rMATS | Uses a hierarchical Bayesian model for PSI estimation and differential analysis. | Robust statistical model for replicate data; well-established. | Differential splicing analysis with biological replicates. |

| LeafCutter | Clusters intron splicing events without relying on existing transcript annotations. | Annotation-free; identifies novel intron clusters and cryptic splicing. | De novo discovery of splicing quantitative trait loci (sQTLs). |

| DEXSeq | Models exon usage counts to test for differential exon usage. | Generalized linear model framework; integrates well with differential expression pipelines. | Exon-level differential usage analysis. |

Detailed Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol I: End-to-End Splicing Analysis Workflow

This protocol outlines the complete process from sample preparation to the visualization of differential splicing results.

1. Experimental Design & Sample Preparation:

- Define conditions and ensure a minimum of three biological replicates per group [31].

- Extract high-quality total RNA. Assess RNA Integrity Number (RIN > 8 recommended).

- Use stranded, paired-end library preparation protocols (e.g., Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA). This preserves strand information, critical for accurate transcript and splice junction assignment [18] [29].

2. Sequencing & Primary Data Generation:

- Sequence libraries to a minimum depth of 30 million paired-end reads (e.g., 2x100 bp) on an Illumina platform [29].

- Demultiplex samples and generate FASTQ files. Perform initial quality control with

FastQC.

3. Bioinformatics Processing (Using nf-core/RNAseq Pipeline):

- Alignment: Use a splice-aware aligner (e.g., STAR) to map reads to the reference genome and transcriptome [18].

- Quantification: Employ alignment-based quantification with Salmon or RSEM to estimate transcript abundances. This step models uncertainty in read assignment to isoforms [18].

- Execution: The nf-core/RNAseq Nextflow pipeline automates these steps, including quality control (QC), alignment, and quantification, ensuring reproducibility [18].

4. Splicing Analysis (Using MAJIQ v2 as an Example):

- Build Splice Graph: Run the

majiq buildcommand using the genome alignment (BAM) files and a gene annotation file (GTF). This step constructs a splice graph for each gene, incorporating unannotated splice junctions [15]. - Quantify Splicing Variations: Run

majiq quanton the built model to compute PSI (Ψ) values for all detected Local Splicing Variations (LSVs) in each sample [15]. - Differential Splicing Analysis: Run

majiq deltapsito compare conditions. The MAJIQ HET test is recommended for heterogeneous datasets, as it applies robust rank-based statistics without assuming a shared PSI per group [15].

5. Visualization & Interpretation:

- Use the companion tool VOILA to visualize significant LSVs. Inspect splice graphs, PSI distributions across samples, and read coverage to validate findings [15].

- Filter results for confidence (e.g.,

|ΔPSI| > 0.2and probabilityP(|ΔPSI| > 0.2) > 0.95). - Perform functional enrichment analysis (e.g., Gene Ontology, KEGG) on genes harboring significant differential splicing events.

Bulk RNA-Seq Splicing Analysis Workflow

Protocol II: Statistical Framework for Subtle Splicing Changes

Detecting subtle differential splicing—critical for clinical or subtype analyses—requires stringent quality control and statistical modeling [29].

1. Quality Control and Signal-to-Noise Assessment:

- Calculate the Principal Component Analysis (PCA)-based Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) for your expression or PSI matrix [29].

- Interpretation: A low SNR indicates high technical noise obscuring biological signal. For studies aiming to detect subtle changes, samples or libraries with SNR < 12 should be investigated and potentially excluded [29].

2. Utilizing Spike-In Controls for Normalization:

- Spike-in controls (e.g., ERCC RNA or SIRVs) can be added during library preparation [29] [31].

- Use these controls to assess technical variability, dynamic range, and to aid in the normalization of splicing metrics, particularly when global transcriptomic changes are large.

3. Application of Heterogeneous Group Statistics:

- When analyzing datasets with high biological variability (e.g., patient samples) or combining public datasets, standard group-wise tests may fail.

- Apply the MAJIQ HET module, which uses non-parametric, rank-based tests (like Mann-Whitney U) on per-sample PSI estimates. This method is more robust to outliers and non-normal distributions common in heterogeneous data [15].

4. Batch Effect Correction:

- If samples were processed in different batches, apply batch correction methods (e.g., using

limma::removeBatchEffectorComBat) to the PSI matrix or read counts before differential testing [30].

Statistical Framework for Splicing Analysis

Research Reagent and Resource Toolkit

The following table lists essential reagents, controls, and software resources critical for ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of bulk RNA-Seq splicing profiling experiments.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Splicing-Focused RNA-Seq

| Category | Item | Function and Application in Splicing Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Library Prep | Stranded mRNA-Seq Kit (e.g., Illumina TruSeq Stranded) | Preserves strand orientation of reads, which is mandatory for accurate annotation of splice junctions and antisense transcripts [18] [29]. |

| Spike-In Controls | ERCC ExFold RNA Spike-In Mixes (Thermo Fisher) | A set of synthetic RNAs at known concentrations. Used to assess technical sensitivity, dynamic range, and accuracy of isoform quantification across samples [29]. |

| Spike-In Controls | SIRV Spike-In Controls (Lexogen) | A set of synthetic isoform variants with known ratios. Specifically designed to benchmark the performance of isoform detection and quantification in RNA-Seq experiments [31]. |

| Alignment & Quantification | STAR Aligner & Salmon | STAR performs fast, accurate splice-aware alignment to the genome [18]. Salmon performs alignment-based or alignment-free quantification, effectively modeling uncertainty in read assignment to isoforms [18]. |

| Splicing Analysis Software | MAJIQ v2 & VOILA v2 | A dedicated suite for quantifying Local Splicing Variations (LSVs), performing differential analysis (including for heterogeneous data), and visualizing complex splice graphs and results [15]. |

| Reference Materials | Quartet Project Reference RNA Samples | Well-characterized reference materials from a family quartet. Used for inter-laboratory benchmarking, especially for assessing performance in detecting subtle differential expression and splicing [29]. |

| Validation | TaqMan Assays or RT-qPCR Primers | Designed across specific splice junctions for independent, targeted validation of key differential splicing events identified in the RNA-Seq analysis [28]. |

A Practical Workflow for Splicing Analysis: From Raw Data to Biological Insight

The comprehensive analysis of alternative splicing (AS) from bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) data is a cornerstone of modern functional genomics, with direct implications for understanding disease mechanisms and identifying therapeutic targets. It is estimated that approximately 90% of human genes undergo alternative splicing, generating transcriptomic diversity crucial for development and cellular differentiation [32]. The accurate detection and quantification of splicing events—such as exon skipping, alternative 5'/3' splice site usage, and intron retention—are fundamentally dependent on the initial step of read alignment. Splice-aware aligners must precisely map sequencing reads that span exon-exon junctions to a reference genome, a computationally intensive task critical for all downstream analyses [33].

Within this framework, HISAT2 and STAR have emerged as two preeminent, yet algorithmically distinct, splice-aware aligners. The choice between them directly influences the sensitivity, accuracy, and reliability of subsequent differential splicing analysis, a key component of a thesis focused on AS in bulk RNA-Seq. HISAT2 employs a hierarchical graph FM-index (GFM) to efficiently map reads against a population of genomes, offering a balanced memory footprint [34]. In contrast, STAR utilizes a highly efficient seed-and-extend algorithm based on uncompressed suffix arrays, prioritizing mapping speed at the cost of greater memory (RAM) usage [35]. Recent studies highlight that while both tools perform robustly, subtle differences in their handling of spliced alignments can lead to variances in the identification of non-canonical junctions and variant calls, potentially impacting biological conclusions [36] [37] [33]. This article provides detailed application notes and protocols to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the optimal alignment strategy for alternative splicing research.

Comparative Analysis: HISAT2 vs. STAR for Splicing-Focused Research

Selecting the appropriate aligner requires a clear understanding of performance trade-offs. The following tables synthesize quantitative data from recent benchmarking studies to guide decision-making.

Table 1: Performance and Benchmarking Overview

| Metric | HISAT2 | STAR | Research Context & Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Algorithm | Hierarchical Graph FM-index (HGFM) [34] | Seed-and-extend with uncompressed suffix arrays [35] | HISAT2 is designed for efficient mapping against a graph representing genetic variation. STAR excels in raw speed for mapping to a linear reference. |

| Typical Mapping Rate | ~93.7% - 99.5% [32] [36] | ~90.5% - 99.5% [36] [35] | Both achieve high rates. HISAT2 may show marginally higher on-target rates in targeted sequencing (rLAS) [32]. |

| Splice Junction Detection | Effective for canonical and non-canonical sites [34]. | High precision for canonical and novel junctions; superior for fusion transcript detection [35]. | STAR's two-pass mode is recommended for novel junction discovery [35]. Both may generate spurious junctions in repetitive regions [37]. |

| Computational Profile | Lower memory footprint. Faster index building. | High memory usage (e.g., ~32GB for human genome). Very fast alignment [33] [35]. | HISAT2 is suitable for resource-constrained environments. STAR requires high-performance hardware but reduces wall-clock time. |

| Impact on Downstream Variant Calling | Contributes to alignment-specific variant sets [33]. | Different splice junction mapping can lead to divergent variant identification [33]. | A study found less than 2% overlap in potential RNA editing sites called from different aligners, highlighting a major source of discrepancy [33]. |

Table 2: Decision Framework for Aligner Selection

| Research Priority | Recommended Aligner | Rationale and Protocol Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Bulk RNA-Seq (Splicing & Expression) | STAR (if resources allow) | Superior speed for large datasets facilitates rapid iteration. Use --twopassMode Basic for comprehensive novel junction discovery [35]. |

| Constrained Computational Resources | HISAT2 | Efficient memory use allows operation on standard workstations or clusters with smaller nodes [34] [33]. |

| Targeted or Long-Amplicon Sequencing (e.g., rLAS) | HISAT2 or STAR | Performance is comparable [32]. Choice may depend on lab pipeline familiarity. HISAT2 showed a slightly higher on-target rate in one evaluation [32]. |

| Dual RNA-Seq (Host-Pathogen) | Combination Approach | For complex eukaryotic hosts, a pathogen-first mapping strategy is critical. Map to pathogen genome first with BWA, then unmapped reads to host genome with HISAT2/STAR to minimize misalignment [38]. |

| Maximizing Reproducibility & Minimizing False Junctions | Either, plus EASTR post-processing | Both aligners can create false spliced alignments in repetitive regions [37]. Running the EASTR tool to filter alignments post-alignment significantly improves accuracy [37]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The following protocols are optimized for alternative splicing analysis in a bulk RNA-Seq context.

Protocol 1: Standard Spliced Alignment Workflow with STAR for Novel Junction Discovery This protocol uses STAR's two-pass mode to maximize sensitivity for novel alternative splicing events, which is essential for discovery-based research [35].

- Genome Index Generation (One-time):

Critical Parameters:

--sjdbOverhangshould be set to (Read Length - 1). Using a comprehensive annotation (GTF) during indexing improves initial junction detection [35].

- Two-Pass Alignment for Novel Splice Junction Detection:

Application Note: The

SJ.out.tabfiles from the first pass are pooled via--sjdbFileChrStartEndto create a enhanced junction database for the final alignment, dramatically improving sensitivity to sample-specific splicing [35].

Protocol 2: Memory-Efficient Alignment with HISAT2 for Targeted Splicing Analysis This protocol is optimized for targeted sequencing data (like rLAS) or environments with limited RAM, where HISAT2's efficiency is advantageous [32] [34].

- Build Index with Known Splice Sites: Note: Building the index is separate from preparing splice site files. The index is built from the FASTA file alone [34].

- Alignment with Annotation Guidance:

Application Note: The

--dta(downstream transcriptome assembly) option reports alignments best suited for assemblers like StringTie, which is a common step in splicing isoform reconstruction. The--no-softclipoption can be beneficial for targeted amplicon data where full-read alignment is desired [32] [34].

Protocol 3: Post-Alignment Filtering with EASTR to Eliminate Systematic Errors Both HISAT2 and STAR can produce false spliced alignments in repetitive regions [37]. This post-processing step is highly recommended to improve the fidelity of downstream splicing analysis.

- Run EASTR on alignment (BAM) files:

- Use filtered BAM for downstream analysis: The

alignments_filtered.bamfile will have alignments supporting spurious junctions removed. Studies show EASTR filtering substantially reduces false positive introns and exons during transcript assembly, improving the accuracy of novel isoform detection [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents, Software, and Materials for Splicing-Aware Alignment Workflows

| Item Name | Type | Function in Splicing Analysis | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| rLAS (Targeted RNA Long-Amplicon Seq) Reagents [32] | Wet-lab Method | Enables deep sequencing of specific low-expressing transcripts for splicing variants. | Critical for validating splicing events in candidate disease genes cost-effectively [32]. |

| Stranded RNA-Seq Library Prep Kit | Wet-lab Consumable | Preserves strand-of-origin information, crucial for accurately assigning reads to the correct transcript and splicing isoform. | Used in standard bulk RNA-Seq protocols for splicing. |

| Dual RNA-Seq Library Prep | Wet-lab Method | Allows concurrent analysis of host and pathogen transcriptomes, relevant for infectious disease splicing studies [38]. | Protocol involves careful RNA isolation to preserve both host and pathogen RNA [38]. |

| Splice-Aware Aligner (STAR/HISAT2) | Core Software | Maps RNA-seq reads across splice junctions to the reference genome. | Fundamental first step. Choice affects all downstream results [36] [33]. |

| EASTR (Emending Alignments Tool) [37] | Post-processing Software | Identifies and removes falsely spliced alignments caused by repetitive sequences, reducing false positive splicing events. | Should be run after alignment and before transcript assembly/quantification [37]. |

| Splicing Analysis Suite (rMATS/MAJIQ) [32] | Downstream Software | Quantifies differential splicing from aligned reads. | Performance varies; rMATS excels at exon skipping, MAJIQ handles diverse event types [32]. |

| Reference Genome & Annotation (GTF) | Data File | Provides the coordinate system and known gene models for alignment and quantification. | Critical for alignment (--sjdbGTFfile in STAR) and quantification. Use the same version consistently. |

| High-Performance Compute Node | Hardware | Provides the necessary memory and CPU for alignment, especially for STAR with large genomes. | ≥32 GB RAM recommended for human genome alignment with STAR [35]. |

Visualization of Workflows and Decision Pathways

(Diagram 1: Standard Bulk RNA-Seq Splicing Analysis Workflow)

(Diagram 2: Decision Tree for Selecting a Splice-Aware Aligner)

Event-Based vs. Isoform-Based Quantification Approaches

In bulk RNA sequencing research, the analysis of alternative splicing (AS) is fundamental for understanding transcriptome diversity, cellular differentiation, and disease mechanisms. Accurate quantification of splicing variations is computationally challenging due to the sequence similarity between isoforms originating from the same gene locus [39]. Two predominant computational paradigms have emerged to address this challenge: event-based and isoform-based quantification. Event-based methods quantify specific, localized splicing variations—such as exon skipping or intron retention—by measuring the proportion of reads supporting one event outcome over another [40]. In contrast, isoform-based methods aim to estimate the absolute or relative abundance of full-length transcript isoforms, treating each complete mRNA molecule as a quantitative unit [41].

The choice between these approaches has significant implications for a research project. Event-based analysis is often more statistically powerful for detecting specific, known changes in splicing patterns, while isoform-based analysis provides a comprehensive, systems-level view of transcriptional output but faces greater inherent uncertainty [42]. This article provides detailed application notes and protocols for both methodologies, framed within the context of a broader thesis on alternative splicing analysis using bulk RNA-seq. It is designed to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the knowledge to select, implement, and interpret these critical analytical strategies.

Event-based and isoform-based quantification represent fundamentally different ways of modeling the transcriptome. Their core differences in methodology directly influence their applications, strengths, and limitations.

Event-Based Quantification focuses on discrete, categorical splicing changes. It reduces the complexity of the transcriptome by examining predefined types of AS events, such as Skipped Exons (SE), Alternative 5' or 3' Splice Sites (A5SS, A3SS), Mutually Exclusive Exons (MXE), and Retained Introns (RI) [40]. The output is typically a "Percent Spliced In" (PSI or Ψ) value, representing the proportion of transcripts from a gene that include a particular sequence element (e.g., an exon). This approach is highly interpretable, as it links directly to specific mechanistic changes in RNA processing. Tools like rMATS, MAJIQ, and SUPPA2 are prominent examples [42] [43].

Isoform-Based Quantification attempts to solve the more general problem of estimating the abundance of every annotated (and sometimes novel) transcript isoform. Methods like Salmon, Kallisto, and RSEM use probabilistic models to resolve the origin of sequencing reads that map to multiple isoforms, outputting estimates in counts or Transcripts Per Million (TPM) [39] [41]. This provides a complete picture of transcriptional output but is notoriously difficult due to the shared exonic sequences among isoforms, especially with short-read data.

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the two approaches:

Table 1: Core Methodological Comparison of Quantification Approaches

| Aspect | Event-Based Quantification | Isoform-Based Quantification |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Unit | Local splicing event (e.g., exon, splice site). | Full-length transcript isoform. |

| Typical Output Metric | Percent Spliced In (PSI/Ψ). | Counts, TPM, or FPKM. |

| Primary Challenge | Accurate read counting for event junctions and bodies. | Resolving multi-mapping reads to correct isoforms. |

| Interpretability | Directly links to a specific biological mechanism. | Requires downstream analysis to infer splicing changes. |

| Examples of Tools | rMATS, MAJIQ, SUPPA2, DEXSeq [42] [40]. | Salmon, Kallisto, RSEM, StringTie [39] [41]. |

| Best Suited For | Detecting specific, known types of differential splicing. | Global profiling, isoform switching, novel isoform discovery. |

Performance benchmarks indicate that the choice of approach and tool significantly impacts results. In a systematic evaluation of differential splicing tools, exon-based methods (a subtype of event-based) and certain event-based tools like rMATS and MAJIQ generally scored well on precision and recall [42] [43]. Meanwhile, studies on isoform quantification show that while alignment-free tools like Salmon and Kallisto are fast and accurate on idealized data, accuracy degrades with complex gene structures, lowly expressed transcripts, and incomplete annotations [39] [41]. Notably, isoform-based quantification of genes like TP53, which produces isoforms with antagonistic functions (e.g., pro-apoptotic full-length vs. anti-apoptotic Δ133 variants), is critical for understanding functional outcomes in cancer [39].

Diagram 1: Conceptual workflow for event and isoform analysis.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Event-Based Differential Splicing Analysis with rMATS

This protocol uses rMATS (replicate Multivariate Analysis of Transcript Splicing), a widely used, computationally efficient tool for detecting differential splicing from replicate RNA-seq experiments [40].

1. Prerequisite Data Preparation:

- Sequence Alignment: Align RNA-seq reads (paired-end recommended) to the reference genome using a splice-aware aligner such as STAR [18]. Output coordinate-sorted BAM files for each sample.

- Sample Grouping: Create a text file listing the BAM file paths, separated into two groups (e.g., treatment vs. control).

2. Running rMATS Quantification: Execute rMATS using the following command structure:

Critical Parameters:

--b1/--b2: Text files containing paths to BAM files for each condition.--gtf: Reference transcriptome annotation in GTF format.--readLength: Must match your sequencing read length.--libType: Strandedness of your library (fr-unstranded,fr-firststrand,fr-secondstrand).--novelSS: Enable to detect splicing events using novel (unannotated) splice sites.

3. Output Interpretation:

rMATS generates results for five event types: Skipped Exon (SE), Alternative 5' Splice Site (A5SS), Alternative 3' Splice Site (A3SS), Mutually Exclusive Exon (MXE), and Retained Intron (RI). The key output file JC.raw.input.*.txt contains:

- Inclusion/Exclusion Counts: Read counts supporting the included and excluded isoforms.