A Comprehensive Guide to Bulk RNA-seq Analysis: Mastering DESeq2 and edgeR for Robust Differential Expression

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and scientists performing differential expression analysis with DESeq2 and edgeR.

A Comprehensive Guide to Bulk RNA-seq Analysis: Mastering DESeq2 and edgeR for Robust Differential Expression

Abstract

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and scientists performing differential expression analysis with DESeq2 and edgeR. It covers the foundational principles of bulk RNA-seq, including count data properties and the negative binomial distribution used by both tools. The guide offers detailed, step-by-step methodological workflows from data import to result interpretation, alongside practical troubleshooting advice for common issues. Furthermore, it presents a comparative analysis of DESeq2 and edgeR, evaluating their performance across different sample sizes and data types to help users select the optimal tool. The content is designed to empower professionals in genomics and drug development to conduct statistically sound and biologically relevant transcriptomic studies.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Concepts and Data Preparation for Bulk RNA-seq

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has revolutionized transcriptomics by enabling genome-wide quantification of RNA abundance with high resolution and accuracy [1]. A fundamental characteristic of RNA-seq data is its count-based nature, where expression values represent discrete, non-negative integers corresponding to the number of sequencing reads mapped to each gene [2]. These counts are inherently noisy and exhibit substantial variability, necessitating specialized statistical models that can properly account for their unique distributional properties [2]. The core challenge in analyzing this data stems from its high-dimensional structure—typically tens of thousands of genes measured across a limited number of samples—combined with multiple sources of biological and technical variation [1] [3].

The selection of an appropriate statistical distribution for modeling RNA-seq counts is not merely a technical formality but a critical determinant of analytical accuracy. Improper models can lead to inflated false discovery rates, reduced power to detect true differential expression, and ultimately, unreliable biological conclusions [4] [5]. Among the various distributions considered for count data, the negative binomial distribution has emerged as the cornerstone for differential expression analysis in bulk RNA-seq workflows, particularly in widely adopted tools such as DESeq2 and edgeR [2] [6]. This preference stems primarily from its ability to handle overdispersion—a phenomenon where the variance in fragment counts exceeds the mean—which is routinely observed in RNA-seq datasets due to biological variability and technical artifacts [2] [4].

The Limitation of Traditional Distributions for RNA-seq Data

Poisson Distribution

The Poisson distribution represents the simplest model for count data, describing the probability of a number of independent events occurring in a fixed interval of time or space [2]. It is characterized by a single parameter (λ) where the variance equals the mean (σ² = μ). This property makes it suitable for modeling rare events with low counts, such as manufacturing failures or radioactive decay [2]. However, this fundamental assumption becomes problematic for RNA-seq data because genes with identical mean expression levels frequently exhibit different variances [2]. In reality, the variance of gene counts typically exceeds the mean, a discrepancy that becomes more pronounced with increasing biological variability between samples. Consequently, the Poisson distribution tends to underestimate variability in RNA-seq data, leading to artificially narrow confidence intervals and inflated type I errors in differential expression testing [4].

Binomial Distribution

The binomial distribution models the probability of achieving a specific number of "successes" in a fixed number of independent trials, each with the same probability of success [2]. For example, it can calculate the probability of obtaining four heads after five coin tosses. This distribution is inherently limited for RNA-seq applications because it presupposes a fixed upper bound (the number of trials) and a binary outcome structure [2]. RNA-seq data, in contrast, lacks a theoretical maximum count value—sequencing depth can vary substantially between experiments—and involves quantifying expression levels across hundreds to thousands of genes with complex, continuous-like expression patterns rather than simple binary outcomes [2].

The Overdispersion Problem in RNA-seq Data

Overdispersion represents a fundamental characteristic of RNA-seq count data where the observed variance systematically exceeds what would be expected under simpler parametric models like the Poisson distribution [4]. This phenomenon arises from multiple sources, including biological variability (genetic differences, physiological states, environmental responses), technical artifacts (library preparation biases, sequencing depth variations, batch effects), and measurement errors [2] [1]. The consequences of unaccounted overdispersion are severe: statistical tests lose calibration, p-values become artificially significant, and false discovery rates increase substantially [4] [5]. This problem is particularly acute in studies with small sample sizes, where accurately estimating variability from limited data is challenging [4].

Table 1: Comparison of Statistical Distributions for RNA-seq Count Data

| Distribution | Key Characteristics | Variance Structure | Suitability for RNA-seq | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poisson | Models rare, independent events | Variance = Mean | Poor | Underestimates true variability; fails to handle overdispersion |

| Binomial | Models fixed number of trials with binary outcomes | Variance = np(1-p) | Very Poor | Requires fixed upper limit; inappropriate for unbounded counts |

| Negative Binomial | Extension of Poisson with dispersion parameter | Variance = μ + αμ² | Excellent | Specifically designed to handle overdispersion in count data |

The Negative Binomial Distribution: Theoretical Foundation

Mathematical Formulation

The negative binomial distribution can be conceptually understood as a Poisson-gamma mixture model, where the Poisson parameter (λ) is itself a random variable following a gamma distribution [2]. This hierarchical structure provides the mathematical flexibility to accommodate extra-Poisson variation. The probability mass function for the negative binomial distribution is given by:

[ P(Y=k) = \frac{\Gamma(k+\frac{1}{\alpha})}{\Gamma(k+1)\Gamma(\frac{1}{\alpha})} \left(\frac{1}{1+\alpha\mu}\right)^{\frac{1}{\alpha}} \left(\frac{\alpha\mu}{1+\alpha\mu}\right)^k ]

where μ represents the mean of the distribution, and α ≥ 0 denotes the dispersion parameter that controls the extent of overdispersion relative to the Poisson distribution [2] [5]. The variance of the negative binomial distribution is given by Var(Y) = μ + αμ², explicitly modeling the relationship where variance increases as a quadratic function of the mean [5]. As α approaches zero, the negative binomial converges to the Poisson distribution, while larger values of α indicate greater overdispersion [2].

The Dispersion Parameter

The dispersion parameter (α) sits at the core of the negative binomial model's ability to handle RNA-seq data complexity. This parameter quantifies the extra-Poisson variation present in the counts and directly influences both the width of confidence intervals and the power of statistical tests [2] [5]. In practice, the dispersion parameter is not treated as fixed but is estimated from the data itself using empirical Bayes methods that share information across genes [6] [5]. This shrinkage approach stabilizes estimates, particularly for genes with low counts or few replicates, by borrowing strength from the overall distribution of dispersions across all genes [6] [5]. The relationship between mean expression and dispersion typically follows a predictable trend, which differential expression tools exploit to improve estimation accuracy [6].

Practical Implementation in Differential Expression Analysis

DESeq2 and edgeR: Negative Binomial-Based Workflows

DESeq2 and edgeR, the two most widely used tools for bulk RNA-seq differential expression analysis, both employ the negative binomial distribution as their statistical foundation but implement distinct approaches to parameter estimation and hypothesis testing [6]. DESeq2 utilizes a median-of-ratios normalization method to correct for differences in sequencing depth and library composition, followed by dispersion estimation using empirical Bayes shrinkage [1] [6]. The model then fits negative binomial generalized linear models (GLMs) and tests for differential expression using Wald tests or likelihood ratio tests [6] [5]. edgeR, conversely, typically applies the TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) normalization and offers multiple approaches for dispersion estimation, including the ability to model a common dispersion across all genes, trended dispersion based on mean expression relationships, or gene-specific dispersions [6] [5]. For hypothesis testing, edgeR provides both likelihood ratio tests and quasi-likelihood F-tests, with the latter generally offering more robust error control, particularly for studies with small sample sizes [6].

Addressing Specialized Analytical Challenges

Recent methodological developments have extended the negative binomial framework to address more complex analytical scenarios. The NBAMSeq package implements a negative binomial additive model that can capture nonlinear relationships between covariates and gene expression, which may be missed by standard linear models [5]. This flexibility is particularly valuable when analyzing the effect of continuous covariates such as age, disease severity scores, or time, where the assumption of linearity may not hold [5]. Similarly, the DEHOGT (Differentially Expressed Heterogeneous Overdispersion Genes Testing) method addresses scenarios where overdispersion patterns vary substantially between experimental conditions, improving detection power particularly in studies with limited replicates [4].

Table 2: Comparison of Negative Binomial-Based Differential Expression Tools

| Tool | Normalization Approach | Dispersion Estimation | Testing Methodology | Special Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | Median-of-ratios | Empirical Bayes shrinkage | Wald test or LRT | Automatic outlier detection, independent filtering, strong FDR control |

| edgeR | TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) | Common, trended, or tagwise | Likelihood ratio test or Quasi-likelihood F-test | Efficient with small samples, multiple testing strategies |

| NBAMSeq | Median-of-ratios (DESeq2-style) | Bayesian shrinkage | Generalized additive model tests | Captures nonlinear effects, smooth functions of covariates |

| DEHOGT | Custom normalization | Heterogeneous across conditions | Likelihood-based | Handles condition-specific overdispersion, improved power for small n |

Experimental Protocols for Differential Expression Analysis

Sample Preparation and Sequencing

Proper experimental design is paramount for generating reliable RNA-seq data. Researchers should include a minimum of three biological replicates per condition, though more may be required when biological variability is high [1]. Biological replicates represent genetically distinct individuals subjected to the same experimental condition, essential for capturing population-level variability, as opposed to technical replicates which involve repeated measurements of the same biological sample [7]. For standard differential expression analyses, sequencing depths of 20-30 million reads per sample are generally sufficient, though this may increase for studies focusing on low-abundance transcripts or for detecting subtle expression changes [1]. Prior to library preparation, RNA quality should be rigorously assessed using appropriate metrics (e.g., RIN > 8), and consistent library preparation protocols should be maintained across all samples to minimize technical batch effects [1] [3].

Computational Workflow

A standardized computational workflow for negative binomial-based differential expression analysis typically includes the following stages:

Quality Control and Trimming: Assess raw sequence quality using FastQC or multiQC, then remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases using tools such as fastp or Trim Galore [1] [3]. This critical first step eliminates technical artifacts that could interfere with accurate alignment and quantification.

Read Alignment and Quantification: Map cleaned reads to a reference genome or transcriptome using aligners like STAR or HISAT2, or employ alignment-free quantification with Salmon or Kallisto [8] [1] [3]. These tools incorporate statistical models to estimate transcript abundances, with Salmon being particularly noted for its accuracy and speed [8] [1].

Count Matrix Import and Preparation: Import quantification results into R/Bioconductor using specialized packages like tximeta (for Salmon output) or tximport, which automatically handle transcript-to-gene summarization and generate appropriate offset matrices to account for differential isoform usage [8].

Exploratory Data Analysis: Perform principal component analysis (PCA) and sample clustering to identify potential batch effects, outliers, or unexpected sample relationships [8] [9]. This qualitative assessment helps validate experimental integrity before formal statistical testing.

Differential Expression with Negative Binomial Models: Implement either DESeq2 or edgeR following their respective workflows, including appropriate normalization, dispersion estimation, and statistical testing [8] [6] [9]. For complex experimental designs with multiple factors, ensure the design matrix properly encodes all relevant biological conditions and technical covariates.

Results Interpretation and Visualization: Generate diagnostic plots such as MA-plots (log-fold change versus mean expression) and volcano plots to visualize differential expression results, and perform functional enrichment analysis to extract biological insights from significant gene lists [7] [9].

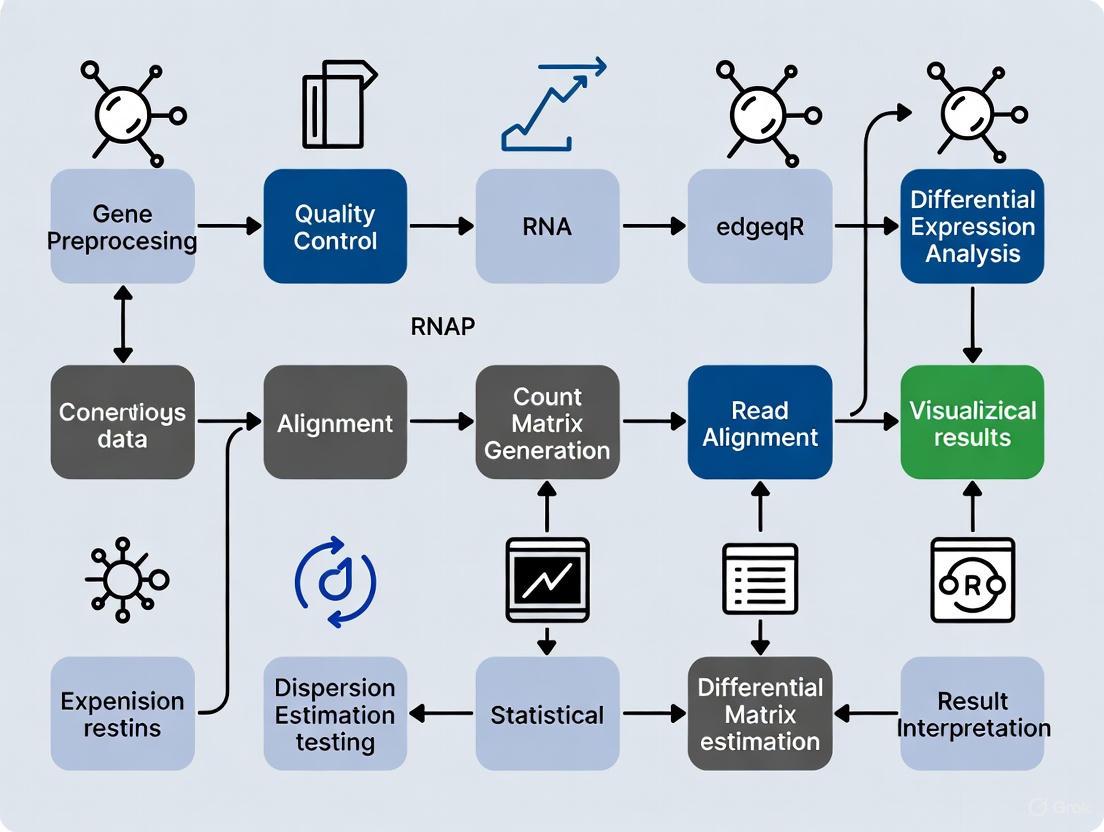

Figure 1: Standard RNA-seq Differential Expression Workflow

Wet-Laboratory Reagents

- RNA Extraction Kits (e.g., TRIzol, column-based kits): Maintain RNA integrity and prevent degradation during sample preparation, crucial for accurate quantification of in vivo expression levels.

- Poly-A Selection or Ribodepletion Kits: Enrich for messenger RNA by targeting polyadenylated transcripts or removing ribosomal RNA, respectively, ensuring efficient sequencing of informative transcripts.

- Reverse Transcriptase and RNA Library Prep Kits: Convert RNA to complementary DNA (cDNA) and add sequencing adapters with unique molecular identifiers to control for amplification biases.

- Quantification and Quality Control Tools (e.g., Bioanalyzer, Qubit): Precisely measure RNA concentration and integrity before library preparation, with minimum quality thresholds (RIN > 8) recommended for reliable results.

- Sequenceing Reagents and Platforms (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq, NextSeq): Generate high-throughput digital readouts of transcript abundance, with appropriate sequencing depth (20-40 million reads/sample) for the experimental design.

Computational Tools and Environments

- R and Bioconductor: Open-source statistical computing environment providing specialized packages (DESeq2, edgeR, limma) for negative binomial-based differential expression analysis [8] [6] [9].

- Python Ecosystems (InMoose, pydeseq2): Python implementations of established R tools, offering similar functionality with nearly identical results for enhanced interoperability between bioinformatics pipelines [10].

- Quality Control Pipelines (FastQC, multiQC, fastp): Assess sequence quality, adapter contamination, and other technical metrics to ensure data quality before formal analysis [1] [3].

- Alignment and Quantification Software (STAR, HISAT2, Salmon, Kallisto): Map reads to reference genomes or directly estimate transcript abundances using alignment-free methods [8] [1] [3].

- High-Performance Computing Resources: Computational clusters or cloud computing platforms capable of handling memory-intensive processing of large RNA-seq datasets, particularly for alignment and quantification steps.

Table 3: Normalization Methods for RNA-seq Count Data

| Method | Sequencing Depth Correction | Gene Length Correction | Library Composition Correction | Suitable for DE Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM | Yes | No | No | No |

| RPKM/FPKM | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| TPM | Yes | Yes | Partial | No |

| Median-of-ratios (DESeq2) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| TMM (edgeR) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

Advanced Considerations and Future Directions

As RNA-seq methodologies continue to evolve, statistical approaches must adapt to address emerging challenges. For studies incorporating multiple continuous covariates or time-series designs, extensions of the negative binomial model such as NBAMSeq offer enhanced flexibility to capture non-linear expression responses [5]. The development of methods like DEHOGT, which specifically addresses heterogeneous overdispersion across experimental conditions, demonstrates ongoing refinements to improve detection power, particularly for studies with limited sample sizes [4]. The recent emergence of cross-platform implementations such as InMoose, which provides Python equivalents of established R tools, reflects growing emphasis on interoperability and reproducibility across computational environments [10].

Future methodological developments will likely focus on integrating negative binomial models with single-cell RNA-seq analytical frameworks, addressing the even more pronounced overdispersion and zero-inflation characteristics of single-cell data. Similarly, multi-omics integration approaches that combine RNA-seq with other data types (e.g., epigenomics, proteomics) will require further extension of these foundational statistical models. Throughout these developments, the negative binomial distribution will remain central to RNA-seq analysis, providing a robust mathematical foundation for extracting meaningful biological insights from count-based sequencing data while properly accounting for their complex variability structure.

Figure 2: Statistical Distribution Comparison for RNA-seq Data

In bulk RNA-seq data analysis, normalization is a critical preprocessing step to account for technical variations, enabling meaningful biological comparisons between samples. The core challenge stems from the fact that the total number of sequenced reads (library size) can vary substantially between samples, and the RNA composition of samples may differ significantly due to biological conditions [11]. Without proper normalization, these technical artifacts can lead to false conclusions in differential expression analysis. Among the various normalization methods developed, the Median Ratio Normalization (RLE) used in DESeq2 and the Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) implemented in edgeR have emerged as two of the most widely adopted and robust scaling normalization methods [12] [13]. Both methods operate under the core principle that most genes are not differentially expressed across conditions, and they aim to estimate sample-specific scaling factors that minimize these technical biases. Despite their similar philosophical foundations, their statistical approaches and implementation details differ in ways that can impact analytical outcomes in specific experimental contexts.

Theoretical Foundations and Algorithmic Workflows

DESeq2's Median Ratio Normalization (RLE)

The Median Ratio Normalization method, also referred to as Relative Log Expression (RLE) normalization, is based on the fundamental assumption that the majority of genes in a dataset are not differentially expressed [11]. This method constructs a pseudo-reference sample against which all individual samples are compared. The step-by-step mathematical procedure is as follows:

Step 1: Pseudo-Reference Sample Creation - For each gene across all samples, calculate the geometric mean. This creates a virtual reference sample that represents the typical expression profile. The geometric mean for gene g is calculated as:

Geometric Mean_g = (∏_{k=1}^{n} X_{g,k})^{1/n}

where X_{g,k} represents the count for gene g in sample k, and n is the total number of samples [11].

Step 2: Ratio Calculation - For each gene in each sample, compute the ratio of its count to the corresponding pseudo-reference value:

Ratio_{g,k} = X_{g,k} / Geometric Mean_g

Step 3: Size Factor Determination - For each sample, the size factor (normalization factor) is calculated as the median of all gene ratios for that sample:

Size Factor_k = median(Ratio_{g,k})

This median-based approach makes the method robust to outliers, including highly differentially expressed genes [11].

The underlying statistical framework of DESeq2 models raw counts using a negative binomial distribution and incorporates these size factors into its generalized linear model for differential expression testing [6].

edgeR's Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM)

The TMM normalization method also operates under the assumption that most genes are not differentially expressed, but implements a different strategy based on pairwise sample comparisons [14]. The algorithm proceeds as follows:

Step 1: Reference Sample Selection - Typically, the sample whose upper quartile of gene counts is closest to the average upper quartile across all samples is chosen as the reference, though users can specify an alternative reference [15].

Step 2: M-value and A-value Calculation - For each gene g when comparing sample k to the reference sample r, compute:

M_g = log₂((X_g/k / N_k) / (X_g/r / N_r))

A_g = ½ · log₂((X_g/k / N_k) · (X_g/r / N_r))

where X_g/k and X_g/r are counts for gene g in the test and reference samples, and N_k and N_r are the total library sizes for the respective samples [14].

Step 3: Data Trimming and Weighting - Trim the data by removing genes with extreme M-values (default: 30% from top and bottom) and genes with extreme A-values (default: 5% from each end). This trimming eliminates genes that are potentially differentially expressed or have very low expression, which could disproportionately influence the normalization [14].

Step 4: Normalization Factor Calculation - Compute the weighted mean of the remaining M-values, where weights are derived from inverse approximate variances, to obtain the log normalization factor. The final TMM scaling factor is the exponential of this value [15] [14].

edgeR incorporates these normalization factors into its statistical framework based on negative binomial generalized linear models, either as offsets or by adjusting the effective library sizes [6] [15].

Table 1: Core Algorithmic Differences Between RLE and TMM Methods

| Aspect | DESeq2's RLE (Median Ratio) | edgeR's TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) |

|---|---|---|

| Reference | Geometric mean across all samples (pseudo-reference) | One actual sample as reference |

| Core Calculation | Median of ratios to pseudo-reference | Weighted trimmed mean of log ratios |

| Data Trimming | Implicit via median robustness | Explicit trimming of extreme M and A values |

| Weighting Scheme | No explicit weighting | Inverse variance weighting |

| Handling of Zero Counts | Problematic for geometric mean | Genes with zero counts in either sample are excluded |

Comparative Analysis of Normalization Performance

Theoretical and Practical Comparisons

Research has demonstrated that while RLE and TMM share similar conceptual foundations, they can yield different results in practice depending on the data characteristics. A comparative study on tomato fruit set RNA-seq data showed that while RLE and MRN (a variant similar to RLE) normalization factors exhibited positive correlation with library size, TMM factors showed no significant correlation with library size [12] [13]. This fundamental difference in behavior stems from their distinct algorithmic approaches to estimating scaling factors.

In terms of performance under different experimental conditions, both methods generally perform well when the assumption of non-DE for most genes holds true. However, studies have indicated that TMM may have advantages in specific scenarios. In a hypothetical situation where case samples have half the number of expressed transcripts compared to controls (but identical sequencing depth), TMM normalization successfully corrected for this composition bias, while library size scaling alone failed dramatically [15]. The TMM method's explicit trimming of extreme values makes it particularly robust to situations where a substantial proportion of genes are differentially expressed or when there are extreme outliers [14].

Impact on Differential Expression Analysis

The choice of normalization method can significantly impact downstream differential expression results. While both methods are widely adopted and generally produce concordant results for clear differential expression patterns, discrepancies can emerge for genes with moderate fold changes or in datasets with complex expression landscapes [6]. Benchmarking studies have shown that the agreement between DEGs identified by DESeq2 and edgeR is generally high, though not perfect, with the level of concordance dependent on factors such as sample size, effect size, and data quality [6] [3].

Table 2: Performance Characteristics Under Different Experimental Conditions

| Experimental Condition | RLE (DESeq2) Performance | TMM (edgeR) Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Simple two-condition design | Excellent | Excellent |

| Large proportion of DE genes | Robust but may be influenced if majority are DE | Highly robust due to explicit trimming |

| Presence of extreme outliers | Moderately robust (median-based) | Highly robust (explicit trimming) |

| Data with high zero counts | May be problematic for geometric mean | TMMwsp variant handles zeros effectively |

| Complex multi-factor designs | Excellent (integrates with GLM) | Excellent (integrates with GLM) |

| Very small sample sizes (n < 5) | Good performance | Good performance, efficient with small samples |

Practical Implementation Protocols

DESeq2 RLE Normalization Protocol

Materials and Reagents:

- Raw count matrix (genes × samples)

- R statistical environment (version 4.0 or higher)

- DESeq2 package (version 1.30.0 or higher)

- Sample metadata table with experimental design

Experimental Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Load raw count data into R, ensuring that row names correspond to gene identifiers and column names to sample identifiers. Prepare a metadata data.frame describing the experimental design.

DESeqDataSet Creation:

Normalization Execution:

Size Factor Extraction:

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If many genes have zero counts across all samples, consider pre-filtering to improve geometric mean calculation.

- If convergence issues arise during subsequent differential expression analysis, examine size factors for extreme values that might indicate sample quality issues.

edgeR TMM Normalization Protocol

Materials and Reagents:

- Raw count matrix (genes × samples)

- R statistical environment (version 4.0 or higher)

- edgeR package (version 3.32.0 or higher)

- Sample metadata table with experimental design

Experimental Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Load raw count data as described for DESeq2 protocol.

DGEList Object Creation:

Normalization Execution:

Normalized Data Access:

Troubleshooting Tips:

- For data with high proportions of zeros, consider using method = "TMMwsp" (TMM with singleton pairing) for improved stability.

- Examine the plotMDS(dge) output to identify potential sample outliers that might unduly influence the TMM calculation.

Visualization of Normalization Workflows

DESeq2 Median Ratio Normalization (RLE) Workflow

Diagram 1: DESeq2 RLE normalization creates a pseudo-reference sample from geometric means, then calculates size factors as the median of each sample's gene ratios to this reference.

edgeR TMM Normalization Workflow

Diagram 2: edgeR TMM normalization selects a reference sample, calculates log ratios, trims extreme values, then computes weighted means to determine normalization factors.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-Seq Normalization Studies

| Resource | Type | Function in Normalization | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference RNA Samples | Biological Standard | Benchmarking normalization performance | External RNA Controls Consortium (ERCC) spikes |

| RNA Extraction Kits | Laboratory Reagent | Ensure high-quality input material | Qiagen RNeasy, TRIzol reagent |

| Library Prep Kits | Laboratory Reagent | Generate sequencing libraries | Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA |

| Alignment Software | Computational Tool | Generate raw count data | STAR, HISAT2, Salmon |

| Statistical Environment | Computational Platform | Execute normalization algorithms | R Statistical Environment |

| Analysis Packages | Computational Resource | Implement normalization methods | DESeq2, edgeR, limma |

| Quality Control Tools | Computational Resource | Assess normalization effectiveness | FastQC, MultiQC, ggplot2 |

Application-Specific Recommendations

The choice between DESeq2's RLE and edgeR's TMM normalization should be guided by specific experimental considerations and data characteristics. Based on comparative studies and methodological evaluations, we recommend:

For standard experimental designs with balanced conditions and no extreme global expression shifts, both methods perform excellently and will yield highly concordant results [12] [16]. The choice can be based on researcher familiarity with the respective packages for downstream analysis.

For datasets with suspected asymmetric differential expression or when a substantial proportion of genes are expected to be DE, TMM may have advantages due to its explicit trimming of extreme values, making it more robust to violations of the "most genes not DE" assumption [14].

For complex multi-factor experiments where integration with sophisticated generalized linear models is required, both methods integrate well with their respective package's modeling frameworks, and the choice may depend on which package's complete analytical workflow better suits the research question [6].

For data with unusual characteristics (extreme composition biases, very small sample sizes, or high proportions of zeros), we recommend running both normalization methods and comparing the resulting lists of differentially expressed genes. Substantial discrepancies should be investigated carefully, potentially using additional validation methods [17] [3].

DESeq2's Median Ratio Normalization and edgeR's TMM represent two sophisticated, robust, and theoretically grounded approaches to RNA-seq count normalization. While both operate under the core principle that most genes are not differentially expressed, their mathematical implementations differ significantly—RLE using a median-based approach with a pseudo-reference, and TMM employing a trimmed mean framework with an actual reference sample. Despite these differences, extensive benchmarking has demonstrated that both methods perform well across a wide range of realistic experimental scenarios, with subtle advantages emerging for each method in specific contexts. Researchers should understand the underlying assumptions of each method and select the approach most appropriate for their experimental design, while recognizing that normalization remains a critical step in RNA-seq analysis that can substantially impact biological interpretations.

In bulk RNA-seq analysis, the accuracy and reliability of differential expression results from tools like DESeq2 and edgeR fundamentally depend on the correct preparation and formatting of input data. These methods employ specialized statistical models designed explicitly for raw count data, which must account for sequencing depth, biological variability, and experimental design. Improperly formatted inputs—such as normalized counts instead of raw integers or incomplete metadata—compromise statistical integrity and can lead to biologically misleading conclusions. This protocol details the essential requirements for preparing count matrices and metadata, ensuring researchers can generate robust, reproducible differential expression results within a comprehensive bulk RNA-seq workflow.

Count Matrix Specifications and Structure

The count matrix forms the quantitative foundation for differential expression analysis, representing raw, unnormalized sequencing reads assigned to each genomic feature across all samples.

Core Requirements and Data Type

Data Type: The matrix must contain raw, integer counts of sequencing reads or fragments. These values are non-negative integers representing the number of times a sequence was assigned to a specific gene [18] [19]. DESeq2 and edgeR's statistical models are specifically designed for raw counts, which allow for correct assessment of measurement precision through the mean-variance relationship [18] [20]. Providing pre-normalized counts, such as those adjusted for library size, disrupts this relationship and leads to nonsensical results.

Matrix Structure: The count matrix is structured as an

m x nmatrix, wherem(rows) corresponds to the number of genes or genomic features, andn(columns) corresponds to the number of samples in the experiment [18] [19]. The row names must be unique gene identifiers (e.g., Ensembl Gene IDs, Entrez IDs, or official gene symbols), while column names should correspond to unique sample identifiers that match the metadata sheet.

Generation and Content Specifications

The count values are generated by aligning sequencing reads to a reference genome or transcriptome and then counting the number of fragments that unambiguously overlap with each gene's exonic regions [21] [18]. Tools such as HTSeq-count or featureCounts are commonly used for this purpose [21] [19]. The resulting counts are proportional to both the abundance of RNA from that gene and the total number of sequenced fragments in the sample.

Table 1: Acceptable and Unacceptable Count Matrix Formats

| Aspect | Recommended Format | Format to Avoid | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Type | Integer counts (raw) | Normalized values (e.g., FPKM, TPM, RPKM) | Statistical models require raw counts to model precision [11] [18] |

| Matrix Orientation | Rows = Genes, Columns = Samples | Rows = Samples, Columns = Genes | Standard expected input for DESeq2/edgeR functions |

| Gene Identifiers | Stable, non-duplicated IDs (e.g., Ensembl ID) | Duplicated or ambiguous gene names | Prevents misassignment and loss of data during analysis |

| Missing Data | 0 for no expression |

NA or blank cells |

Algorithms are designed to handle true zero counts |

Metadata Requirements and Experimental Design

The metadata sheet, often called the sample table or colData, provides the critical experimental context that enables correct statistical modeling and interpretation of results.

Essential Components and Structure

The metadata must be structured as a data frame or table where rows correspond to samples and columns correspond to experimental variables and sample information [18] [19]. The row names of the metadata table must exactly match the column names of the count matrix. This exact matching is crucial, as DESeq2 and edgeR use this correspondence to link expression data with experimental conditions.

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between the count matrix and metadata, and how they are integrated to create an analysis-ready object.

Critical Variables and Covariates

Primary Conditions: The metadata must include the primary experimental conditions being tested (e.g., treatment vs. control, time points, tissue types) [21]. These factors are incorporated directly into the design formula of the statistical model.

Technical Covariates: Include technical factors such as sequencing batch, lane effects, or library preparation date that could introduce systematic variability. These can be included in the design formula to account for their effects [21].

Biological Covariates: Biological variables such as sex, age, genotype, or clinical characteristics should be included if they might influence gene expression independently of the primary condition [21].

Table 2: Essential Metadata Components for DESeq2 and edgeR

| Metadata Field | Description | Example Format | Importance for Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| SampleID | Unique identifier for each sample | SRR1039508, Patient_001 | Must match column names in count matrix [18] |

| Primary Condition | Main experimental factor | "control", "treated" | Used in design formula for differential testing |

| Batch | Technical processing batch | "batch1", "batch2" | Can be included to correct for technical variation |

| Biological Replicate | Origin of biological sample | "mouse1", "mouse2" | Distinguishes independent biological sources |

| Sex/Gender | Biological sex of subject | "M", "F" | Accounts for sex-specific expression effects |

| Library Size | Total reads per sample (optional) | 28345121 | Can be used for quality assessment |

Data Preprocessing and Normalization Protocols

Before formal differential expression analysis, proper preprocessing ensures data quality and prepares counts for robust statistical testing.

Pre-filtering Low Count Genes

Pre-filtering the count matrix removes genes with minimal expression, reducing memory requirements and increasing analytical power. DESeq2 automatically applies filtering, but manual pre-filtering can be implemented:

This filtering approach retains genes with sufficient expression to be biologically meaningful while reducing multiple testing burden [22].

Normalization Methods

DESeq2 and edgeR employ sophisticated normalization procedures to account for technical artifacts while preserving biological signal. DESeq2 uses the median-of-ratios method [11], which accounts for both sequencing depth and RNA composition. This method calculates a size factor for each sample by comparing counts to a pseudo-reference sample and uses the median of these ratios for normalization [11].

edgeR typically uses the trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) method, which similarly corrects for sequencing depth and RNA composition while being robust to highly differentially expressed genes [11]. Both methods are performed automatically within their respective packages when using standard analysis workflows.

Table 3: Normalization Methods Comparison for RNA-seq Data

| Method | Sequencing Depth Correction | RNA Composition Correction | Gene Length Correction | Suitable for DE? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 (median-of-ratios) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes [11] |

| edgeR (TMM) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes [11] |

| CPM | Yes | No | No | No |

| TPM | Yes | Partial | Yes | No |

| RPKM/FPKM | Yes | No | Yes | No |

Quality Control and Integration Workflow

A comprehensive quality control protocol ensures the integrity of the data before proceeding to differential expression testing.

Sample Matching and Object Creation

The following workflow diagram outlines the critical steps for integrating count matrices and metadata into analysis-ready objects for DESeq2 and edgeR, including essential quality checks.

Implementation Protocols

For DESeq2, create a DESeqDataSet object using:

For edgeR, create a DGEList object using:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Tools and Resources for Bulk RNA-seq Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | Differential expression analysis using negative binomial distribution | Primary analysis for count data with shrinkage estimation [20] |

| edgeR | Differential expression analysis using empirical Bayes methods | Alternative to DESeq2 with robust statistical framework [23] |

| HTSeq-count/featureCounts | Generate count matrices from aligned BAM files | Read quantification for genomic features [21] [19] |

| STAR/HISAT2 | Spliced alignment of reads to reference genome | Read mapping for traditional alignment-based workflow [1] [18] |

| Salmon/kallisto | Pseudoalignment for transcript quantification | Fast, alignment-free quantification [1] [24] |

| tximport | Import transcript-level estimates to gene-level | Bridge between pseudoaligners and count-based methods [18] |

| biomaRt | Gene identifier conversion and annotation | Resolving gene ID mismatches and adding annotation [22] |

In the analysis of bulk RNA-seq data, a critical step in the workflow prior to differential expression analysis with tools like DESeq2 and edgeR is the pre-filtering of low-expressed genes. This process involves removing genes with consistently low read counts across samples in the dataset. While RNA-seq datasets measure the expression of tens of thousands of genes, a substantial proportion of these genes exhibit minimal to no expression, providing little biological information for downstream analyses [25]. The practice of pre-filtering is not merely a data reduction technique but a statistically sound strategy that enhances the power and reliability of subsequent analyses. Within the context of a comprehensive DESeq2 and edgeR bulk RNA-seq workflow, effective pre-filtering reduces multiple testing burdens, mitigates the influence of technical noise, and improves the detection of biologically relevant differentially expressed genes [26] [27]. This application note details the rationale, methodologies, and practical implementation of gene filtering strategies to optimize analytical outcomes for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Rationale for Pre-filtering

Biological and Statistical Justifications

The removal of low-expressed genes is justified from both biological and statistical perspectives. Biologically, genes that are not expressed at biologically meaningful levels in any experimental condition are unlikely to be of interest for understanding the phenotypic differences under investigation [25]. From a statistical viewpoint, genes with very low counts provide little power for differential expression detection and can distort mean-variance relationships in the data, which are fundamental to statistical models used in packages like DESeq2 and edgeR [25].

Systematically adding noise to feature data has been shown to significantly degrade classification performance across a range of machine learning algorithms [26]. Filtering out genes with low read counts minimizes this interference, ensuring that detected patterns have greater biological relevancy. This is particularly important in biomarker discovery, where the goal is to identify robust gene signatures that generalize well across patient populations [26].

Impact on Downstream Analysis

Pre-filtering significantly influences multiple testing correction, a critical step in high-throughput genomic analyses. RNA-seq datasets typically contain measurements for over 10,000 genes, necess adjustment for false discovery rates (FDR). Without filtering, the inclusion of thousands of low-count genes that have no chance of being differentially expressed unnecessarily strict multiple testing corrections, reducing the power to detect truly significant changes [25].

Research has demonstrated that applying a systematic strategy for removal of uninformative biomarkers representing up to 60% of transcripts in different sample size datasets leads to substantial improvements in classification performance, higher stability of resulting gene signatures, and better agreement with previously reported biomarkers [26]. The performance uplift from gene filtering depends on the machine learning classifier chosen, with L1-regularised support vector machines showing the greatest performance improvements in experimental sepsis biomarker discovery [26].

Quantitative Foundations of Gene Filtering

Threshold Determination Methods

Table 1: Common Thresholds for Low-Expression Filtering

| Method | Typical Threshold | Basis | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum Count | 5-10 reads | Absolute read count | Small datasets, preliminary filtering |

| Counts-Per-Million (CPM) | 0.5-1 CPM | Library size normalized | Between-sample comparison |

| Proportion-Based | 10-25% of samples | Data completeness | Signature stability |

| Variance-Based | IQR > 0.25-0.75 quantile | Expression variability | Exploratory analyses |

The optimal threshold for filtering low-expressed genes depends on multiple factors including sample size, sequencing depth, and the specific biological question. A commonly used approach implemented in the edgeR package is the filterByExpr function, which automatically determines appropriate filtering thresholds based on the experimental design [27] [25]. This function keeps genes that have at least a minimum number of reads in a minimum number of samples, with the specific thresholds determined by the sample library sizes and the minimum group sample size [25].

For a typical dataset, the filterByExpr function might retain approximately 58% of originally detected genes when using a min.count threshold of 10 [25]. Alternative approaches include quantile-based filtering, which may retain a higher percentage of genes (approximately 75% with a 0.25 quantile cutoff), and variance-based filtering, which can be more restrictive (retaining only 25% of genes with a 0.75 quantile cutoff) [25].

Impact Assessment of Filtering Strategies

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Filtering Methods

| Filtering Method | Genes Retained | DEGs Detected | Classification Performance | Signature Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Filtering | 100% | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| filterByExpr | ~58% | Increased | Substantial improvement | Higher |

| Quantile (0.25) | ~75% | Moderate increase | Moderate improvement | Moderate |

| Variance-Based | ~25% | Variable | Application-dependent | Variable |

The performance of different filtering strategies can be evaluated based on their impact on downstream analyses. Systematic assessment of applying transcript level filtering demonstrates that removal of uninformative and potentially biasing biomarkers leads to substantial improvements in classification performance, higher stability of resulting gene signatures, and better agreement with previously reported biomarkers [26]. The optimal filtering approach depends on the specific analytical goals, with more stringent filtering generally beneficial for classification tasks, while milder filtering may be preferable for exploratory biomarker discovery.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol 1: Standardized Pre-filtering for Differential Expression Analysis

This protocol describes a standardized approach for pre-filtering low-expressed genes prior to differential expression analysis with DESeq2 or edgeR.

Materials:

- Raw count matrix from RNA-seq quantification

- R statistical environment (version 4.0 or higher)

- edgeR and DESeq2 packages installed

Procedure:

Load Count Data: Import the raw count matrix into R, ensuring genes are represented as rows and samples as columns.

Initial Data Assessment: Calculate basic statistics including total genes, percentage of zero counts, and mean counts per gene.

Apply filterByExpr Filtering (edgeR):

Alternative: Custom Threshold Filtering:

Proceed with Standard DE Analysis: Continue with standard DESeq2 or edgeR workflow using the filtered count matrix.

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Optimized Filtering for Biomarker Discovery

This protocol describes a specialized filtering approach optimized for machine learning applications in biomarker discovery, based on recent research findings [26].

Materials:

- Normalized count matrix from RNA-seq data

- R or Python environment with necessary ML libraries

- Clinical or phenotypic metadata for sample groups

Procedure:

Data Preparation: Begin with normalized count data (e.g., using DESeq2's median of ratios normalization or variance stabilizing transformation).

Two-Stage Filtering Approach:

Stage 1: Low Count Filtering

Stage 2: Outlier Filtering

Validation of Filtering Efficacy:

- Compare classification performance (e.g., AUC) with and without filtering

- Assess feature stability through bootstrap resampling

- Evaluate biological coherence of selected features

Proceed with ML Modeling: Use the filtered dataset for subsequent machine learning tasks, noting that L1-regularised support vector machines have shown particularly strong performance improvements with appropriately filtered data [26].

Workflow Integration and Visualization

RNA-seq Pre-filtering Workflow

RNA-seq Pre-filtering Decision Workflow: This diagram illustrates the strategic decision points for selecting appropriate pre-filtering methods based on analytical goals, showing the divergent paths for differential expression analysis versus machine learning applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| edgeR (filterByExpr) | Automated filtering threshold determination | Differential expression analysis |

| DESeq2 (independent filtering) | Automated within DESeq2 pipeline | Standard DE analysis without manual filtering |

| Custom CPM-based filtering | Flexible threshold implementation | Study-specific filtering needs |

| Genefilter package | Variance-based filtering | Exploratory data analysis |

| TCGAbiolinks | Integrated filtering for TCGA data | Cancer genomics applications |

| Salmon/Kallisto | Pseudoalignment and quantification | Rapid transcript quantification |

| STAR aligner | Spliced alignment to genome | Reference-based alignment |

| FastQC/MultiQC | Quality control assessment | Pre-alignment data assessment |

Pre-filtering of low-expressed genes represents a critical step in bulk RNA-seq analysis workflows that significantly enhances analytical power and biological interpretability. The strategic removal of uninformative genes reduces multiple testing burden, decreases technical noise, and improves the stability and performance of downstream analyses. The optimal filtering approach depends on the specific analytical goals, with automated methods like filterByExpr providing robust performance for standard differential expression analyses, while more sophisticated two-stage approaches incorporating outlier detection offer advantages for machine learning applications. Implementation of these pre-filtering strategies within DESeq2 and edgeR workflows provides researchers and drug development professionals with a powerful approach to extract more meaningful biological insights from RNA-seq data.

Within the framework of a bulk RNA-seq workflow utilizing tools like DESeq2 and edgeR, rigorous quality control (QC) is the foundational step that ensures the reliability of all subsequent biological interpretations. High-dimensional transcriptomic data necessitates robust methods to visualize overall data structure, identify outliers, and assess technical variability before proceeding to differential expression testing [28]. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and sample clustering are two cornerstone techniques for this exploratory phase, providing an unsupervised glimpse into the strongest trends and inherent groupings within a dataset [29]. This application note details the integrated use of PCA and hierarchical clustering to evaluate sample quality and homogeneity, a critical protocol for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in transcriptomics research.

Theoretical Background

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

PCA is a dimensionality reduction technique that transforms high-dimensional data into a new coordinate system defined by its principal directions of variance, the Principal Components (PCs) [30]. The first PC captures the largest possible variance in the data, with each succeeding component capturing the next highest variance under the constraint of orthogonality to the preceding components [31]. For RNA-seq data, which typically contains expression values for thousands of genes across a much smaller number of samples, PCA allows researchers to project samples into a 2D or 3D space defined by the first two or three PCs. This projection facilitates the visualization of overall data structure, revealing whether samples from the same experimental condition cluster together and highlighting any potential outliers driven by technical artifacts or unexpected biological variation [29] [31]. The percentage of total variance explained by each PC indicates how well the low-dimensional representation reflects the original dataset [30].

Hierarchical Clustering

Hierarchical clustering is an algorithm that builds a nested tree structure (a dendrogram) from data based on their pairwise similarities [29]. A common "bottom-up" approach begins by treating each sample as its own cluster and then successively merges the two most similar clusters until all samples belong to a single tree [30]. The resulting dendrogram provides an intuitive visualization of sample relationships, where the length of the branches represents the degree of similarity—samples with shorter branches are more alike [30]. When visualized alongside a heatmap of the expression data, it allows researchers to simultaneously observe sample groupings and the gene expression patterns that drive them [29]. Unlike PCA, which filters out weaker signals, a heatmap presents the entire observed data matrix, which can include noise but also preserves weak patterns [29].

Complementary Roles in Quality Control

PCA and hierarchical clustering serve complementary roles in QC. PCA is optimal for visualizing the strongest, most dominant patterns in the data, often those separating different sample groups, and is highly effective for spotting outliers in the low-dimensional space [29] [31]. Hierarchical clustering, through the dendrogram and heatmap, provides a detailed view of global similarity and helps identify specific genes contributing to sample groupings [29]. In practice, the most dominant patterns identified by PCA often correspond well with the primary clusters observed in hierarchical clustering [29]. However, hierarchical clustering will always generate clusters even in the absence of strong biological signal, whereas PCA will appear as a diffuse cloud of points in such a scenario, making PCA a more honest indicator of data structure [29].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of PCA and Hierarchical Clustering for QC.

| Feature | Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Hierarchical Clustering |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Dimensionality reduction and visualization of major variance trends [30] [31] | Grouping samples into a tree structure based on overall similarity [30] [29] |

| Output | Scatter plot (PC1 vs. PC2); Scree plot (variance explained) [30] [31] | Dendrogram; often combined with a heatmap [29] |

| Strengths | Excellent for identifying outliers and major sample groupings; Filters out noise [29] [31] | Intuitive visualization of sample relationships; Shows underlying expression data [29] |

| Considerations | Only displays a fraction of total variance; Patterns may be masked in large, complex datasets [32] | Can find clusters even without true signal; Visualization can be complex with many samples [32] [29] |

Protocols and Application Notes

Pre-Analysis: Data Preprocessing and Normalization

The input for PCA and clustering in an RNA-seq context is typically a normalized count matrix. It is critical that the data has undergone proper preprocessing and normalization to remove technical artifacts and enhance comparability across samples [28].

- Generate Count Matrix: Use tools like STAR [28] or HISAT2 [28] for read alignment, followed by transcript assembly (e.g., with StringTie [28]) and quantification (e.g., with featureCounts [28] or Salmon [28]) to produce a matrix of raw read counts per gene for each sample.

- Normalize Data: Normalization is a critical step to account for differences in library size and RNA composition [28]. Within the DESeq2 workflow, this is handled internally via its median-of-ratios method to calculate size factors [28]. For edgeR, the trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) is used [28]. These normalized counts are then suitable for transformation (e.g., variance stabilizing transformation in DESeq2) prior to visualization.

Protocol 1: Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

This protocol details the steps to perform and interpret PCA for sample-level QC.

Procedure:

- Input Preparation: Start with a normalized and transformed (e.g., VST in DESeq2) count matrix. The matrix should have genes as rows and samples as columns.

- Execute PCA: Perform PCA on the transposed matrix (samples as rows, genes as variables). Most statistical software environments (R, Python) and specialized bioinformatics platforms like Qlucore or Metabolon's platform have built-in PCA functions [29] [31].

- Visualization and Interpretation:

- Scree Plot: Generate a scree plot to visualize the proportion of total variance explained by each principal component. This helps determine how many PCs are needed to adequately represent the data.

- PCA Scatter Plot: Create a 2D scatter plot of the samples using the first two PCs (PC1 vs. PC2). Color and shape the points based on known experimental factors (e.g., genotype, treatment, batch).

- Interpretation: Examine the plot for clustering of samples by known conditions. Samples from the same condition should cluster closely. Isolated samples or those grouping with the wrong condition are potential outliers that warrant investigation. The axes show the percentage of variance explained, indicating the strength of the pattern displayed [30].

Figure 1: A simplified workflow for performing and interpreting PCA in RNA-seq quality control.

Protocol 2: Hierarchical Clustering

This protocol outlines the steps for performing hierarchical clustering to assess sample similarity.

Procedure:

- Input Preparation: Use the same normalized and transformed count matrix as for PCA.

- Calculate Distance Matrix: Compute a pairwise distance matrix between all samples. Common distance measures include Euclidean distance (for normalized, continuous data) or correlation-based distances (1 - Pearson correlation).

- Perform Clustering: Apply a hierarchical clustering algorithm (e.g., Ward's method [30]) to the distance matrix to build a dendrogram.

- Visualization and Interpretation:

- Dendrogram: Plot the dendrogram. The structure shows how samples are nested based on similarity.

- Heatmap Integration: For a more comprehensive view, plot the dendrogram alongside a heatmap of the expression matrix (often for a subset of highly variable genes). This links sample similarity to specific expression patterns.

- Interpretation: Check if samples from the same experimental condition cluster together on the same major branches of the tree. Samples that are outliers, forming their own branch or clustering with a different group, should be flagged for further inspection.

Figure 2: A workflow for performing hierarchical clustering and interpreting the resulting dendrogram.

Advanced Protocol: Combined HCA and PCA (hcapca)

For very large or complex datasets with many samples, a single PCA model can become ineffective as the first few PCs may explain a very small percentage of the total variance, obscuring meaningful patterns [32]. A powerful solution is to first group strains using hierarchical clustering and then perform PCA on the smaller, more chemically homogeneous subgroups [32].

Procedure:

- Hierarchical Clustering: Perform HCA on the full, normalized dataset to generate a dendrogram of all samples.

- Cluster Cutting: Define a dissimilarity cutoff to divide the dendrogram into distinct, smaller sub-groups (clusters). This can be automated or guided by domain knowledge.

- Sub-group PCA: Perform a separate PCA on the samples within each sub-group.

- Interpretation: Within these smaller, more homogeneous groups, the PCA model is more robust, and the explained variance for the first PCs is significantly higher, making it easier to identify outliers and subtle patterns that were masked in the global analysis [32].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Issues in PCA and Clustering.

| Issue | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Samples do not cluster by known condition in PCA | High technical variation; Batch effects; Incorrect normalization [33] | Investigate for batch effects; Verify normalization strategy; Check for outlier samples. |

| First two PCs explain very little variance (<20%) | Dataset is very large and complex with no single dominant pattern [32] | Use the hcapca approach [32]; Inspect later PCs; Focus analysis on highly variable genes. |

| One sample is a clear outlier in PCA and dendrogram | Sample preparation failure; Sequencing artifact; Extreme biological outlier | Examine QC metrics for that sample (mapping rate, rRNA content); Consider exclusion if justified. |

| Clusters in heatmap are driven by very few genes | The chosen gene set may not be informative for the biological question. | Use a larger set of genes, such as all expressed genes or the top highly variable genes. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Software Tools.

| Item / Tool | Function in PCA/Clustering QC |

|---|---|

| DESeq2 / edgeR | Primary tools for normalization (size factors, TMM) and differential expression; Provide the normalized count matrix for downstream QC [28]. |

| FastQC / MultiQC | Provides initial quality assessment of raw sequence data; critical for identifying issues before alignment and quantification [28]. |

| STAR / HISAT2 | Spliced read aligners that map RNA-seq reads to a reference genome, a prerequisite for generating an accurate count matrix [28]. |

| featureCounts / HTSeq | Quantification tools that count the number of reads overlapping genomic features (genes) to build the raw count matrix [28]. |

| R / Python | Programming environments with extensive statistical and graphical capabilities (e.g., stats, ggplot2, scikit-learn packages) for executing PCA and hierarchical clustering. |

| Qlucore Omics Explorer | Commercial software designed for rapid, interactive exploration of high-dimensional data, including PCA and heatmap visualization [29]. |

| Galaxy Project | Web-based platform providing accessible, point-and-click interfaces for running a wide variety of bioinformatics tools, including those for RNA-seq QC and visualization [7]. |

Integrating PCA and hierarchical clustering into the initial QC phase of a bulk RNA-seq workflow is non-negotiable for robust data interpretation. These unsupervised methods provide a critical lens through which researchers can verify data quality, identify technical confounders like batch effects and outliers, and gain initial confidence that biological replicates are consistent. Before applying sophisticated differential expression tools like DESeq2 and edgeR, ensuring that the input data passes these fundamental QC checks lays the groundwork for generating biologically accurate and statistically significant results, thereby de-risking the entire research and drug development pipeline.

From Raw Data to Results: Step-by-Step Analysis Workflows

DESeq2 is a powerful and widely used R/Bioconductor package for determining differential expression from RNA-seq count data. It utilizes a negative binomial generalized linear model to account for the count-based nature of the data and the overdispersion commonly observed in sequencing experiments [34] [35]. The core analysis workflow integrates multiple statistical components to test for significant differences in gene expression between experimental conditions. The fundamental model employed by DESeq2 can be represented as [35]: $$ K{ij} \sim \textrm{NB}( \mu{ij}, \alphai) $$ $$ \mu{ij} = sj q{ij} $$ $$ \log2(q{ij}) = x{j.} \betai $$ Here, counts $K{ij}$ for gene *i* and sample *j* follow a Negative Binomial distribution with fitted mean $\mu{ij}$ and a gene-specific dispersion parameter $\alphai$. The fitted mean comprises a sample-specific size factor ($sj$) and a parameter ($q{ij}$) proportional to the expected true fragment concentration. The coefficients $\betai$ provide the log2 fold changes for each gene corresponding to columns in the model matrix $X$ [35].

This application note details three fundamental components of the DESeq2 pipeline—the DESeqDataSet object container, the estimateSizeFactors normalization procedure, and the nbinomWaldTest for statistical inference—providing detailed protocols for researchers conducting differential expression analyses in bulk RNA-seq experiments.

The DESeqDataSet Object: Foundation for Analysis

Object Creation and Structure

The DESeqDataSet is the central data structure that stores raw count data, sample metadata, and the model formula, serving as the input container for all subsequent DESeq2 functions [34] [36]. This object extends the SummarizedExperiment class, organizing data into several key components [37]:

counts: A matrix of non-normalized integer read counts, with rows representing genomic features (genes/transcripts) and columns representing samples.colData: A DataFrame containing sample metadata with information on experimental conditions (e.g., treatment, batch, genotype).design: A formula that expresses how counts depend on the variables incolData, typically specified as~ factor_of_interest.

Table 1: Core Components of the DESeqDataSet Object

| Component | Data Type | Description | Essential Content |

|---|---|---|---|

counts |

Integer matrix | Raw count data | Rows = genes, columns = samples |

colData |

DataFrame | Sample metadata | Experimental conditions, replicates |

design |

Formula | Model design | ~ condition + batch (variables must match colData columns) |

rowRanges |

GRanges | Genomic ranges | Gene/transcript coordinates (optional) |

assays |

List | Additional matrices | Normalized counts, dispersion estimates |

Initialization Methodology

The DESeqDataSet is typically created using the DESeqDataSetFromMatrix() function when count data is already loaded into R as a matrix [36]. The protocol below outlines the critical steps:

Protocol 1: Constructing a DESeqDataSet from a Count Matrix

Prepare the count matrix: Ensure the count data is in a numeric matrix format with gene identifiers as row names and sample names as column names. Preliminary filtering to remove genes with extremely low counts across all samples is recommended to reduce computational load [36].

Prepare the column data: Create a DataFrame where rows correspond to samples (in the same order as the count matrix columns) and columns represent experimental factors. Convert categorical variables to factors with appropriate reference levels [38].

Specify the design formula: Construct a model formula that captures the experimental design. The last factor in the formula is typically the condition of interest for differential expression testing [34] [39].

Create the DESeqDataSet object:

Figure 1: Workflow for creating a DESeqDataSet object from component inputs.

estimateSizeFactors: Normalization for Library Size Differences

Theoretical Basis of Size Factor Estimation

The estimateSizeFactors function implements the "median ratio method" for normalizing library sizes across samples [40]. This procedure corrects for differences in sequencing depth and RNA composition without relying on spike-in controls or assuming that most genes are non-differentially expressed. The method operates under the principle that, for most genes, the ratio of observed count to a pseudo-reference value (geometric mean across samples) should be approximately constant within a sample [34] [39].

The calculation for each gene i and sample j involves:

- Computing the geometric mean of counts for each gene across all samples.

- Calculating the ratio of each sample's count to this geometric mean for every gene.

- Deriving the size factor for sample j as the median of these ratios, excluding genes with zero counts in any sample or where the geometric mean is zero.

Normalization Protocol and Alternative Methods

Protocol 2: Implementing estimateSizeFactors in DESeq2

Access the function: The method is automatically called within the

DESeq()wrapper function but can be executed separately for exploratory analysis.Examine results: Retrieve size factors to verify normalization effectiveness.

Quality assessment: Size factors should correlate with, but not be identical to, library sizes. Investigate any samples with extreme size factor values that might indicate quality issues.

Table 2: Size Factor Estimation Methods in DESeq2

| Method | Function Call | Use Case | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard (ratio) | estimateSizeFactors(object, type="ratio") |

Most experiments | Robust, standard approach | Fails with many zeros |

| poscounts | estimateSizeFactors(object, type="poscounts") |

Data with many zeros | Handles zero-inflated data | Modified geometric mean |

| iterate | estimateSizeFactors(object, type="iterate") |

Complex zero patterns | Iterative estimation | Computationally intensive |

| User-defined | sizeFactors(dds) <- values |

Spike-in controls | Incorporates external controls | Requires prior knowledge |

Alternative algorithms are available for specialized applications. The "poscounts" method calculates a modified geometric mean using only positive counts, making it suitable for data with many zeros (e.g., single-cell RNA-seq) [40]. The "iterate" method alternates between estimating dispersions and finding size factors by numerically optimizing the likelihood of the intercept-only model, which can be beneficial for complex datasets where the standard method fails [40].

nbinomWaldTest: Statistical Testing for Differential Expression

Theoretical Foundation of the Wald Test in DESeq2

The nbinomWaldTest implements Wald tests for significance of coefficients in a Negative Binomial GLM, using previously calculated size factors and dispersion estimates [41]. After fitting the GLM coefficients, DESeq2 assumes a zero-centered normal prior distribution for non-intercept coefficients to moderate large fold changes in genes with low counts—an approach known as Tikhonov/ridge regularization [41]. The prior variance is estimated by matching the 0.05 upper quantile of observed maximum likelihood coefficients to a zero-centered normal distribution [41].

The final coefficients are maximum a posteriori estimates using this prior. For Wald test p-values, these coefficients are scaled by their standard errors and compared to a standard normal distribution (or a t-distribution if useT=TRUE is specified) [41]. This approach provides a computationally efficient method for testing hypotheses about model coefficients.

Implementation Protocol

Protocol 3: Executing nbinomWaldTest

Prerequisites: Ensure the

DESeqDataSethas already been processed withestimateSizeFactorsandestimateDispersionsbefore running the Wald test.Key parameters: Several arguments control the test behavior:

Extract results: Use the

results()function to generate a table of differential expression statistics.

Figure 2: Statistical workflow of the nbinomWaldTest procedure.

Alternative Testing Strategies

While the Wald test is the default in DESeq2 for pairwise comparisons, the nbinomLRT (Likelihood Ratio Test) provides an alternative approach suitable for testing multiple levels of a factor or assessing the significance of full models versus reduced models [41] [34]. The LRT examines whether the increased likelihood of the data under the more complex model justifies the additional parameters by comparing the ratio of likelihoods to a χ² distribution [34].

Table 3: Comparison of Statistical Tests in DESeq2

| Feature | nbinomWaldTest | nbinomLRT |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Use | Pairwise comparisons | Multi-level factors, complex designs |

| Distribution | Standard normal or t-distribution | χ² distribution |

| Speed | Faster | Slower |

| Precision | Better for small sample sizes with useT=TRUE |

Less precise for small samples |

| Applications | Standard treatment vs. control | Time course, nested models |

Integrated Experimental Protocol

Complete DESeq2 Workflow

This integrated protocol outlines a complete differential expression analysis from raw counts to results interpretation, incorporating the three core components detailed in this application note.

Protocol 4: Comprehensive DESeq2 Differential Expression Analysis

Data Preparation and Experimental Design

DESeqDataSet Construction

Pre-processing and Quality Control

- Filter low-count genes:

dds <- dds[rowSums(counts(dds)) > 5,] - Examine library sizes:

colSums(counts(dds)) - Perform exploratory analysis (e.g., PCA) on transformed counts:

- Filter low-count genes:

Normalization and Dispersion Estimation

- The

DESeq()wrapper function automatically executes the three core steps: - This single command performs:

- Size factor estimation (

estimateSizeFactors) - Dispersion estimation (

estimateDispersions) - Model fitting and Wald testing (

nbinomWaldTest)

- Size factor estimation (

- The

Results Extraction and Interpretation

- Filter results based on adjusted p-value and log2 fold change thresholds:

Table 4: Troubleshooting Common Issues in DESeq2 Analysis

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

nbinomWaldTest convergence warnings |

Extreme count outliers or overdispersion | Increase maxit parameter; check for contamination |

| Size factors of extreme magnitude | A few highly expressed genes dominating calculation | Use controlGenes parameter to specify housekeeping genes |

| Many genes with Cook's distance outliers | True biological outliers or poor replicates | Increase minReplicatesForReplace or disable outlier replacement |

| Dispersion plot shows unusual patterns | Inadequate sample grouping or hidden batch effects | Revisit experimental design; include additional covariates |

Table 5: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DESeq2 RNA-seq Analysis

| Resource Type | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function in Analysis | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome | ENSEMBL, UCSC, NCBI genomes | Provides genomic coordinates for read alignment and counting | TxDb.Hsapiens.UCSC.hg19.knownGene [42] |

| Alignment Software | TopHat2, STAR, HISAT2 | Aligns RNA-seq reads to reference genome | tophat2 -o output -p 8 genome reads.fastq [42] |

| Counting Tools | HTSeq, featureCounts | Generates raw count data from aligned reads | summarizeOverlaps(exonsByGene, BamFileList) [42] |

| Normalization Control | Housekeeping genes, Spike-in RNAs | Alternative normalization for specialized experiments | estimateSizeFactors(controlGenes=housekeeping) [40] |

| Quality Assessment | FastQC, MultiQC, DESeq2's PCA | Evaluates sample quality and technical variation | plotPCA(vsd, intgroup="condition") [43] |

The DESeq2 pipeline represents a sophisticated statistical framework for differential expression analysis that integrates robust normalization through estimateSizeFactors, appropriate variance modeling via dispersion estimation, and rigorous statistical testing using nbinomWaldTest. The DESeqDataSet object serves as the foundational container that maintains data integrity throughout this process. This application note has provided detailed protocols for implementing these core components, emphasizing proper experimental design, quality control, and interpretation of results. When correctly implemented following these guidelines, DESeq2 offers researchers a powerful method for extracting biologically meaningful insights from RNA-seq count data, with applications spanning basic research through drug development programs.

Within the context of bulk RNA-seq workflow research, the edgeR package is a fundamental tool for differential expression analysis. As a Bioconductor package, edgeR employs statistical methods based on the negative binomial distribution to model count data and identify genes exhibiting significant expression changes between experimental conditions [44]. This protocol focuses on three core components of the edgeR pipeline: the creation of a DGEList object to store data, the estimation of dispersion using estimateDisp, and hypothesis testing with glmQLFTest. These functions form the backbone of a robust differential expression analysis, enabling researchers and drug development professionals to uncover biologically relevant transcriptional changes with statistical confidence.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential computational reagents for edgeR analysis

| Reagent/Software | Function in Analysis | Example/Tool |

|---|---|---|