Batch Effects Removal in Bulk RNA-Seq: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Clinical Applications

Batch effects represent one of the most significant technical challenges in bulk RNA-sequencing analysis, capable of obscuring true biological signals and leading to irreproducible findings.

Batch Effects Removal in Bulk RNA-Seq: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Clinical Applications

Abstract

Batch effects represent one of the most significant technical challenges in bulk RNA-sequencing analysis, capable of obscuring true biological signals and leading to irreproducible findings. This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for understanding, implementing, and validating batch effect correction strategies. Drawing on current methodologies including advanced tools like ComBat-ref and foundational principles of experimental design, we explore systematic approaches for identifying batch effect sources, applying appropriate correction algorithms, troubleshooting common pitfalls, and rigorously validating results. By integrating these strategies into analytical workflows, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability and interpretability of transcriptomic data, ultimately accelerating translational research and biomarker discovery.

Understanding Batch Effects: Sources, Impact, and Diagnostic Strategies

What is a Batch Effect?

In molecular biology, a batch effect refers to the systematic technical variations introduced into high-throughput data when samples are processed in separate batches or under differing experimental conditions. These variations are not related to the biological subject of the study and, if left unaddressed, can confound the results, leading to inaccurate or irreproducible conclusions [1].

In the specific context of bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq), this translates to non-biological fluctuations in gene expression measurements. These fluctuations can be caused by numerous factors throughout the experimental workflow, such as the use of different reagent lots, changes in personnel, or the instrument's performance on different days [1] [2]. A key challenge is that these technical variations can be correlated with the biological outcomes of interest, making it difficult to distinguish true biological signals from technical noise [1] [3].

What Causes Batch Effects in RNA-Seq?

Batch effects can arise at virtually every stage of an RNA-Seq experiment. The table below summarizes the common sources of this technical variation.

Table: Common Sources of Batch Effects in RNA-Seq Experiments

| Stage of Workflow | Source of Variation | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Study Design | Flawed or Confounded Design [2] | Non-randomized sample collection; group assignment correlated with processing batch. |

| Sample Preparation | Protocol & Storage Inconsistencies [2] [4] | Differences in centrifugation force; RNA extraction method; sample storage temperature and duration; repeated freeze-thaw cycles. |

| Library Preparation | Reagent & Personnel Differences [1] | Different lots of kits and enzymes; varying incubation times; different technicians. |

| Sequencing | Instrument & Run Conditions [1] [3] | Different sequencing platforms or flow cells; instrument calibration drift; time of day the run was conducted. |

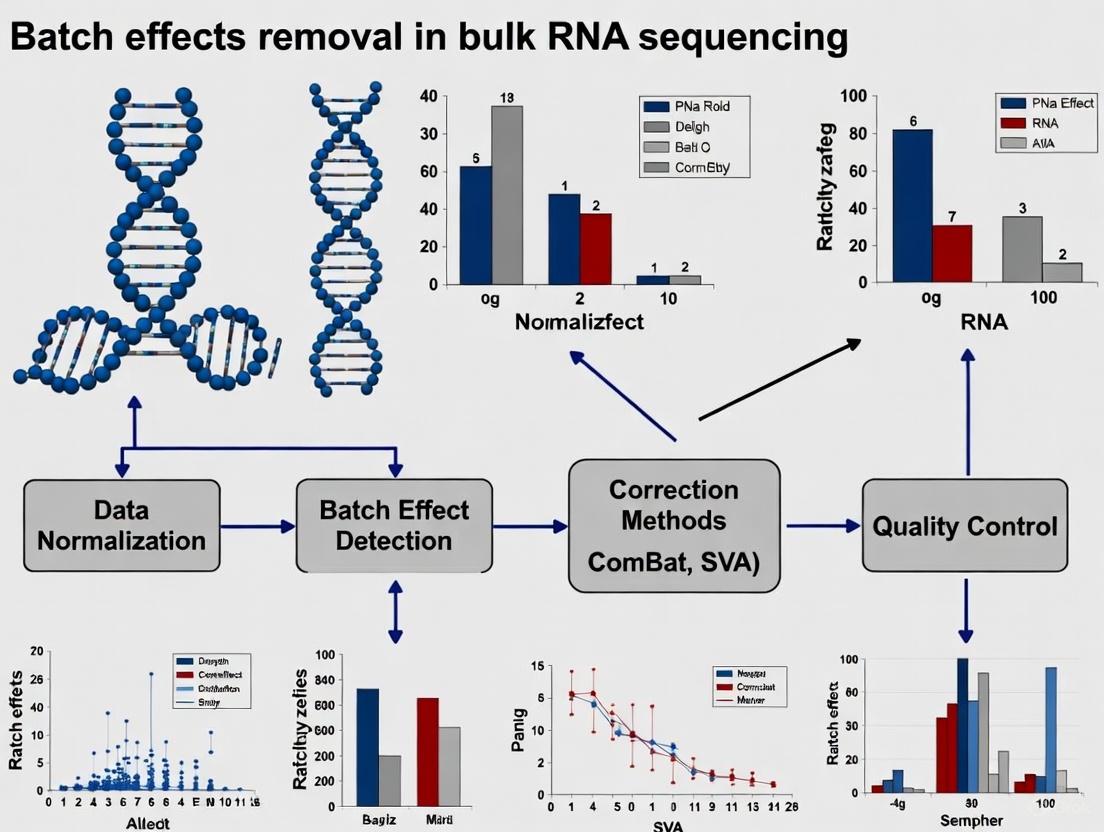

The following diagram illustrates how these factors introduce variation throughout the experimental lifecycle.

How to Detect Batch Effects

Before correction can begin, you must first identify the presence of batch effects in your dataset. The following table outlines the primary methods, ranging from visual inspection to quantitative metrics.

Table: Methods for Detecting Batch Effects in RNA-Seq Data

| Method Type | Description | How to Interpret Results |

|---|---|---|

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [5] | A dimensionality reduction technique that projects data onto axes of greatest variance. | If samples cluster strongly by processing batch or date—rather than by biological group—on a PCA plot (e.g., along PC1 or PC2), a batch effect is likely present. |

| Clustering & Visualization (t-SNE/UMAP) [5] | Non-linear dimensionality reduction techniques used to visualize high-dimensional data in 2D or 3D. | Similar to PCA, if cells or samples from the same biological group form separate clusters based on their batch of origin, this indicates a strong batch effect. |

| Quantitative Metrics [3] [5] | Statistical scores that measure batch mixing. | Metrics like the k-nearest neighbor batch effect test (kBET) or Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) quantitatively assess if batches are well-integrated. Lower values often indicate stronger batch separation. |

| Machine Learning Quality Scores [3] | Using a classifier to predict sample quality. | Systematic differences in predicted quality scores (e.g., Plow) between batches can indicate a batch effect related to technical quality. |

Several computational strategies have been developed to remove batch effects. The choice of method depends on your experimental design and the nature of your data.

Table: Common Batch Effect Correction Algorithms for RNA-Seq Data

| Method | Underlying Strategy | Key Advantage | Consideration/Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical Bayes (e.g., ComBat) [1] [6] | Location and Scale (L/S) adjustment using an empirical Bayes framework to standardize mean and variance across batches. | Easy to implement and widely used; effective when batch information is known. | Assumes batch effects are consistent across genes; may be less effective with time-dependent drift [7]. |

| Surrogate Variable Analysis (SVA) [1] | Matrix Factorization. Identifies unmodeled latent factors (surrogate variables) from the data that represent unwanted variation. | Does not strictly require known batch labels; can capture unknown sources of variation. | The orthogonality assumption between factors may not always hold in real data [6]. |

| Mutual Nearest Neighbors (MNN) [1] [8] | Identifies pairs of cells (one in each batch) that are mutual nearest neighbors in the expression space, assuming they represent the same biological state. | Corrects for cell-type-specific batch effects without requiring a global adjustment. | Computationally intensive for very large datasets; performance can depend on the order of batch correction. |

| Machine Learning-Based [3] | Uses a machine-learning model (trained on quality metrics) to predict and correct for quality-associated batch effects. | Can detect and correct batches based on quality differences without prior batch knowledge. | Correction is tied to quality metrics and may not address all sources of batch variation. |

| Deep Learning (e.g., DESC) [8] | An unsupervised deep embedding algorithm that iteratively clusters data while removing batch effects. | Can be performed without explicit batch information; jointly performs clustering and batch correction. | Requires significant computational resources; may be more complex to implement than traditional methods. |

The typical workflow for diagnosing and correcting batch effects is summarized in the following diagram.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Proper experimental execution relies on key reagents and materials to maintain RNA integrity and data quality. The following table lists essential items for RNA-seq experiments and their functions in preventing technical variation.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-Seq

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Troubleshooting Tip |

|---|---|---|

| RNase-free Tips, Tubes & Water [4] | To prevent degradation of RNA samples by ubiquitous RNases. | Ensure all work surfaces and equipment are treated with RNase decontamination solutions. Wear gloves at all times. |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents (e.g., TRIzol) [4] | To immediately lyse cells/tissues and inactivate RNases, preserving the in vivo transcriptome. | For small tissue/cell quantities, adjust TRIzol volume proportionally to prevent excessive dilution and poor RNA precipitation. |

| RNA Cleanup Kits & Columns [9] | To purify RNA from salts, proteins, and other contaminants after extraction. | To avoid salt/ethanol carryover, ensure the column tip does not contact the flow-through. Re-centrifuge if unsure. |

| DNase I [9] | To digest and remove contaminating genomic DNA, which can interfere with accurate transcript quantification. | Include an DNase I digestion step during the cleanup process if downstream applications are sensitive to DNA contamination. |

| ERCC Spike-In Controls [10] | Synthetic RNA molecules of known concentration added to samples to standardize RNA quantification and assess technical performance. | Use to determine the sensitivity, dynamic range, and technical variation of an RNA-Seq experiment. Not recommended for very low-concentration samples. |

| Ribosomal RNA Depletion Kits [10] | To remove abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which otherwise dominates sequencing libraries, allowing for more efficient sequencing of mRNA and other RNAs. | Essential for samples with low RNA quality (e.g., FFPE) or when studying non-polyadenylated RNAs (e.g., bacterial transcripts, lncRNAs). |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) [10] | Short random barcodes added to each cDNA molecule before amplification to correct for PCR bias and duplicates in downstream analysis. | Highly recommended for low-input protocols and deep sequencing. Use bioinformatics tools (e.g., fastp, umi-tools) for UMI extraction and deduplication. |

Troubleshooting Guides

RNA Extraction and Quality Control

Problem: RNA Degradation

- Causes: RNase contamination; improper sample storage or storage for too long; repeated freezing and thawing of samples [4].

- Solutions:

- Use certified RNase-free consumables and work in a dedicated clean area.

- Store samples at -85°C to -65°C and avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles by aliquoting.

- Add samples directly to lysis buffer immediately upon removal from storage [4].

Problem: Genomic DNA Contamination

- Causes: Incomplete removal of DNA during extraction; high sample input [4].

- Solutions:

- Reduce the starting sample volume and ensure sufficient lysis reagent is used.

- Use reverse transcription reagents with a genome-removal module.

- Treat samples with DNase I during the RNA cleanup process [9].

Problem: Low RNA Yield or Purity

- Causes: Incomplete homogenization; reagent carryover (salt, ethanol); protein/polysaccharide contamination [4] [9].

- Solutions:

- Optimize homogenization conditions to ensure complete tissue disruption.

- Increase the number of ethanol wash steps during column-based cleanup.

- When aspirating supernatant, be careful not to disturb the pellet or the column membrane [4].

Batch Effect Correction

Problem: Overcorrection (Removing Biological Signal)

- Signs: Loss of expected cluster-specific markers; widespread expression of non-specific genes (e.g., ribosomal genes) across clusters; a significant overlap in markers between distinct cell types; scarcity of differential expression hits in expected pathways [5].

- Solutions:

- Use a less aggressive correction method. Algorithms that make weaker assumptions (e.g., MNN) may be preferable.

- Validate results with known biological truths. Ensure that expected differences between biological groups are preserved post-correction.

- Compare results from multiple correction algorithms to build consensus.

Problem: Poor Batch Mixing After Correction

- Causes: The chosen algorithm is not powerful enough for the strength of the batch effect; batches are completely confounded with biological groups; the correction model is misspecified [3] [8].

- Solutions:

- Consider a more advanced algorithm (e.g., a deep learning method like DESC) that can handle complex, non-linear batch effects.

- If batches are confounded with conditions, leverage external controls or housekeeping genes in methods like RUV to guide the correction.

- Manually inspect and remove severe outlier samples that may be skewing the correction [3].

Problem: Batch Information is Unknown

- Causes: In large consortium data or when meta-data is incomplete or mislabeled [6].

- Solutions:

- Use methods designed to detect hidden batch factors, such as SVA or DASC (Data-Adaptive Shrinkage and Clustering) [6].

- Leverage machine learning-based quality scores to detect and correct for quality-associated batches [3].

- Employ unsupervised methods like DESC that can remove batch effects without requiring prior batch labels [8].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between normalization and batch effect correction?

- A: Normalization corrects for technical variations that affect the entire sample, such as sequencing depth and library size. It operates on the raw count matrix. In contrast, batch effect correction addresses systematic differences between groups of samples (batches) that arise from factors like different reagents, personnel, or sequencing runs. It typically operates on normalized data [5].

Q2: Can good experimental design prevent the need for batch effect correction?

- A: While excellent experimental design is the first and most important line of defense—by randomizing samples across batches and including control samples—it cannot always entirely prevent batch effects. Technical variation is often inevitable in large, complex studies. Therefore, a combination of sound design and post-hoc computational correction is considered best practice [2] [7].

Q3: How do I know if my batch correction was successful?

- A: Success is evaluated by both visual and quantitative metrics.

- Visual: After correction, PCA and UMAP plots should show samples mixing according to their biological group, not their batch.

- Quantitative: Metrics like the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) or k-nearest neighbor batch effect test (kBET) should show improved scores, indicating better integration [5].

- Biological Validation: Known biological signals and differential expression results should remain strong and make biological sense [3].

Q4: Are batch effects the same in bulk and single-cell RNA-Seq?

- A: The core concept is the same, but the manifestation and correction strategies differ. Single-cell RNA-seq data is much sparser (with many zero counts) and exhibits higher technical variability. Consequently, batch effects are often more pronounced. While some algorithmic principles are shared, many methods are specifically designed for one data type or the other due to these differences in scale and data structure [2] [5].

Q5: What are Quality Control (QC) samples, and why are they critical?

- A: QC samples are pooled samples created by mixing a small amount of every sample in the study. They are analyzed at regular intervals (e.g., every 10 samples) throughout the sequencing run. Because they are theoretically identical, any drift in their measurements over time reflects technical instrument drift or batch effects. They are essential for monitoring data quality and are used by many advanced batch correction algorithms (e.g., SVR, RSC) to model and remove this drift [7].

Batch effects are systematic, non-biological variations introduced into high-throughput data due to changes in technical conditions. These can arise from variations in experimental procedures over time, the use of different laboratories or instruments, or differences in analysis pipelines [2]. In transcriptomics, these technical artifacts represent one of the most significant challenges to data reliability, potentially obscuring true biological signals and leading to incorrect conclusions [11] [12].

The fundamental cause of batch effects can be partially attributed to the basic assumption in omics data that instrument readout intensity has a fixed relationship with analyte concentration. In practice, this relationship fluctuates due to diverse experimental factors, making measurements inherently inconsistent across different batches [2].

Documented Consequences of Batch Effects

Clinical Trial Misclassification: In a clinical trial study, a change in the RNA-extraction solution introduced batch effects that caused a shift in gene-based risk calculations. This resulted in incorrect classification outcomes for 162 patients, 28 of whom subsequently received incorrect or unnecessary chemotherapy regimens [2].

Species vs. Tissue Differences: Research initially suggested that cross-species differences between human and mouse were greater than cross-tissue differences within the same species. However, reanalysis revealed that the data came from different experimental designs and were generated 3 years apart. After proper batch correction, the gene expression data clustered by tissue type rather than by species, demonstrating that the original conclusion was an artifact of batch effects [2].

Impact on Research Reproducibility

A Nature survey found that 90% of respondents believed there is a reproducibility crisis in science, with over half considering it significant [2]. Batch effects from reagent variability and experimental bias are paramount factors contributing to this problem [2].

The Reproducibility Project: Cancer Biology failed to reproduce over half of high-profile cancer studies, highlighting the critical importance of eliminating batch effects across laboratories [2]. In one notable case, authors of a study published in Nature Methods had to retract their article on a fluorescent serotonin biosensor when they discovered the sensor's sensitivity was highly dependent on the batch of fetal bovine serum used in experiments [2].

Detection and Diagnosis: A Troubleshooting Guide

Visual Detection Methods

| Method | Procedure | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Perform PCA on raw data and analyze top principal components [5] [11]. | Scatter plots showing sample separation by batch rather than biological source indicate batch effects [5]. |

| t-SNE/UMAP Plots | Visualize cell groups on t-SNE or UMAP plots, labeling by batch and biological condition [5] [13]. | Cells clustering by batch instead of biological similarity signal batch effects [5] [13]. |

| Clustering Analysis | Create heatmaps and dendrograms from expression data [13]. | Samples clustering by processing batch rather than treatment group indicate batch effects [13]. |

Quantitative Metrics for Batch Effect Assessment

| Metric | Purpose | Ideal Value |

|---|---|---|

| k-nearest neighbor Batch Effect Test (kBET) | Tests whether batch labels are randomly distributed among nearest neighbors [5] [12]. | Higher acceptance rate indicates better mixing. |

| Local Inverse Simpson's Index (LISI) | Measures diversity of batches in local neighborhoods [14] [12]. | Values closer to 1 indicate better batch mixing [5]. |

| Average Silhouette Width (ASW) | Evaluates cluster compactness and separation [12]. | Higher values indicate better-defined clusters. |

| Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) | Measures clustering accuracy against known cell types [12] [15]. | Values closer to 1 indicate better preservation of biological structure. |

Frequently Asked Questions: Detection

Q: How can I distinguish between true biological differences and batch effects? A: True biological differences typically manifest as changes in specific pathways or coordinated gene expression patterns, while batch effects often affect genes uniformly across unrelated biological processes. Including control samples across batches can help distinguish these effects [12].

Q: What if I don't have complete batch information? A: Methods like Surrogate Variable Analysis (SVA) can estimate hidden sources of variation that may represent batch effects, even when batch variables are unknown or partially observed [11] [12].

Batch Effect Correction Methodologies

Experimental Design Strategies

The most effective approach to batch effects is prevention through proper experimental design:

- Randomization: Distribute samples from all biological conditions across processing batches [12]

- Balancing: Ensure equal representation of phenotype classes across batches [16]

- Replication: Include at least two replicates per group per batch for robust statistical modeling [12]

- Controls: Use pooled quality control samples and technical replicates across batches [12]

Computational Correction Methods

| Method | Algorithm Type | Best For | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat/ComBat-seq | Empirical Bayes framework [17] [11] [12] | Bulk RNA-seq with known batch variables [12] | Requires known batch info; may not handle nonlinear effects [12] |

| limma removeBatchEffect | Linear model adjustment [11] [12] | Integration with differential expression workflows [11] | Assumes additive batch effects; known batch variables [12] |

| Harmony | Iterative clustering with PCA [5] [12] | Single-cell data; large datasets [5] [13] | Faster runtime; good performance on complex data [5] [13] |

| Seurat CCA | Canonical Correlation Analysis [5] [13] | Single-cell data integration [5] | Lower scalability for very large datasets [13] |

| Mixed Linear Models | Random effects modeling [11] | Complex designs with nested/hierarchical batches [11] | Handles multiple random effects; computationally intensive [11] |

Step-by-Step Correction Protocol

Using ComBat-seq for Bulk RNA-seq Data

Using Harmony for Single-Cell RNA-seq Data

Validation of Correction Effectiveness

After applying batch correction, validate using:

- Visual Inspection: Re-run PCA and UMAP plots - batches should now mix while biological conditions remain distinct [11] [13]

- Quantitative Metrics: Recalculate kBET, LISI, ASW, and ARI - these should show improved batch mixing while maintaining biological separation [12]

- Biological Validation: Check that known cell-type markers or expected differential expression patterns are preserved [13]

Advanced Considerations and Special Cases

Avoiding Overcorrection

Overcorrection occurs when batch effect removal also eliminates biological signal. Warning signs include:

- Distinct cell types clustering together on UMAP plots [13]

- Complete overlap of samples from very different biological conditions [13]

- Cluster-specific markers comprising ubiquitous genes like ribosomal genes [5]

- Loss of expected differential expression hits [5]

Handling Challenging Scenarios

Substantial Batch Effects: For datasets with strong technical or biological confounders (different species, technologies, or organoid vs. primary tissue), advanced methods like sysVI (using conditional variational autoencoders with VampPrior and cycle-consistency constraints) may be necessary [14].

Imbalanced Samples: When cell type proportions differ substantially across batches, methods like Harmony and LIGER generally handle imbalance better than anchor-based approaches [13].

Multi-omics Integration: Batch effects in multi-omics data are particularly complex as they involve multiple data types with different distributions and scales, requiring specialized integration approaches [2].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Consistent Reagent Lots | Minimize technical variation | Use single manufacturing batch for entire study when possible [2] |

| Pooled QC Samples | Monitor technical variation across batches | Process alongside experimental samples for normalization [12] |

| Internal Standards | Control for technical variability | More common in metabolomics; adapted for transcriptomics [12] |

| Reference Datasets | Benchmark performance | Well-characterized samples processed alongside experiments [14] |

Computational Tools Checklist

- Experimental Design: R package 'randomizeBE' for sample randomization

- Quality Control: FastQC, MultiQC for sequencing quality assessment

- Batch Detection: PCA, UMAP, kBET, LISI metrics

- Correction Methods: ComBat-seq (bulk), Harmony (single-cell), sysVI (complex batches)

- Validation: ARI, ASW, biological marker preservation checks

Batch effects represent a formidable challenge in transcriptomics research with demonstrated potential to derail scientific conclusions and compromise reproducibility. Through rigorous experimental design, appropriate application of computational correction methods, and thorough validation of correction outcomes, researchers can mitigate these technical artifacts. The framework presented in this technical support guide provides a systematic approach to identifying, correcting, and validating batch effects, thereby safeguarding the biological integrity and reproducibility of transcriptomics research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are batch effects in bulk RNA-seq analysis? Batch effects are systematic technical variations introduced during the experimental process that are unrelated to the biological questions of interest. These non-biological variations can arise from multiple sources, including different sequencing runs or instruments, variations in reagent lots, changes in sample preparation protocols, different personnel handling the samples, or time-related factors when experiments span weeks or months [11]. In bulk RNA-seq data, these effects can confound downstream analysis by introducing patterns that may be mistakenly interpreted as biological signals [3].

2. Why is PCA particularly useful for detecting batch effects? Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a dimensionality reduction technique that transforms potentially correlated variables into principal components (PCs) that are linearly uncorrelated [18]. The first few PCs capture the largest possible variance in the dataset [19]. Batch effects often represent substantial systematic variation in the data, making them visible as strong patterns along principal components when samples cluster by batch rather than by biological condition [11]. This makes PCA an excellent visual diagnostic tool for initial batch effect detection before proceeding with formal statistical testing [3].

3. What PCA patterns suggest the presence of batch effects? When visualizing the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2), clear clustering of samples according to their processing batch rather than their biological group strongly indicates batch effects [11]. Additional signs include separation along higher-order principal components that correlates with batch information, and significant differences in quality metrics (such as machine-learning-derived Plow scores) between batches [3]. The percentage of variance explained by early PCs that correlates with batch variables also provides quantitative evidence of batch influences [18].

4. Can PCA reliably distinguish batch effects from biological signals? While PCA can visualize strong batch effects, it cannot automatically distinguish technical artifacts from genuine biological variation [3]. This distinction requires careful experimental design and additional analytical approaches. When batch information is known, coloring samples by batch in PCA plots makes technical patterns apparent [11]. For unknown batches, correlation with quality metrics and differential expression analysis of genes contributing to suspect PCs can help determine the nature of the variation [3].

5. What are the limitations of using only PCA for batch effect diagnosis? PCA primarily captures linear relationships and may miss complex batch effects that manifest non-linearly [18]. It also provides visualization but not quantitative measures of batch effect magnitude, and its effectiveness depends on the strength of batch effects relative to biological signals [3]. Additionally, PCA results can be sensitive to data preprocessing steps and normalization methods [19]. Therefore, PCA should be used alongside other diagnostic approaches such as clustering metrics and differential analysis of control genes [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Clustering Results in Downstream Analysis

Symptoms:

- Samples cluster by processing date rather than biological group

- Poor clustering evaluation scores (low Gamma and Dunn1 values, high WbRatio)

- Unexpectedly few differentially expressed genes between biological conditions [3]

Diagnostic Steps:

- Generate PCA plot colored by batch [11]

Examine clustering metrics Calculate between-cluster to within-cluster variance ratios (WbRatio), Gamma, and Dunn1 indices to quantify separation quality [3].

Check for quality-batch correlation Calculate correlation between sample quality metrics (e.g., Plow scores) and batch groupings [3].

Solutions:

- Apply batch correction methods if PCA shows clear batch clustering

- Remove outlier samples identified in PCA that disproportionately influence clustering

- Include batch as a covariate in differential expression models [11]

Problem: Suspected Batch Effects But No Batch Information Recorded

Symptoms:

- Unexplained variance patterns in PCA plots

- Clustering correlates with temporal rather than biological variables

- Quality metrics show systematic differences across sample subgroups [3]

Diagnostic Steps:

- Perform PCA without batch coloring [19]

Calculate surrogate variables Use factor analysis or surrogate variable analysis (SVA) to identify hidden batch effects [11].

Correlate PCs with sample metadata Test associations between principal components and available sample metadata (collection date, extraction date, etc.) [3].

Solutions:

- Apply unsupervised batch correction methods like ComBat-seq without known batches

- Use quality-aware correction approaches that leverage machine-learning-predicted sample quality

- Include surrogate variables in statistical models to account for unknown batch effects [3]

Table 1: Clustering Metrics for Batch Effect Assessment [3]

| Metric | Ideal Value | Indicates Batch Effect | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| WbRatio | Lower (→0) | Higher (→1) | Ratio of within-to-between cluster distance |

| Gamma | Higher (→1) | Lower (→0) | Between-cluster similarity measure |

| Dunn1 | Higher (→1) | Lower (→0) | Ratio of smallest inter-to-intra cluster distance |

| DEGs | Higher count | Lower count | Number of differentially expressed genes |

Table 2: PCA Interpretation Guide for Batch Effect Diagnosis [3] [19]

| PCA Pattern | Batch Effect Likelihood | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Clear separation by known batch | High | Apply batch correction; include batch in models |

| Separation along PC1/PC2 correlated with quality metrics | High | Quality-aware correction; outlier removal |

| Mixed clustering with no batch pattern | Low | Investigate biological explanations |

| Separation only in higher PCs (PC3+) | Moderate | Assess variance explained; consider limited correction |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Comprehensive PCA Workflow for Batch Effect Detection

Materials:

- Normalized RNA-seq count matrix

- Sample metadata with batch information

- R statistical environment with packages: stats, ggplot2, limma [11]

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing

- Filter low-expressed genes (keep genes expressed in ≥80% of samples)

- Normalize using TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) or similar method

- Log-transform count data if necessary [11]

PCA Implementation ```r

Transpose count matrix for PCA (samples as rows)

counttbllowrmt <- as.data.frame(t(counttbllow_rm))

Perform PCA with scaling

pcaprep <- prcomp(counttbllowrm_t, scale. = TRUE)

pcasummary <- summary(pcaprep) varianceexplained <- pcasummary$importance[2,1:2] * 100 ``` [11]

Visualization and Interpretation

- Plot PC1 vs PC2 colored by batch and biological condition

- Examine higher PCs (PC3, PC4) for additional batch patterns

- Calculate variance explained by each component [18]

Statistical Correlation Analysis

- Test for significant differences in quality scores between batches using Kruskal-Wallis test

- Calculate designBias metric to quantify confounding between batch and biological groups [3]

Protocol 2: Quality-Aware Batch Effect Assessment

Materials:

- FASTQ files or quality metrics

- Machine learning quality predictor (seqQscorer)

- Batch annotation data [3]

Methodology:

- Quality Score Calculation

- Derive quality features from FASTQ files (full files or subset of 1 million reads)

- Compute Plow scores using pre-trained classifier - probability of sample being low quality [3]

Batch-Quality Correlation Analysis ```r

Test for quality differences between batches

kruskaltest <- kruskal.test(Plow ~ batch, data = samplemetadata) designBias <- cor(Plow, as.numeric(factor(batch))) ``` [3]

Integrated Visualization

- Create combined plots showing PCA patterns and quality score distributions by batch

- Identify outlier samples with disproportionately low quality scores [3]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Batch Effect Diagnostics [3] [11] [20]

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| prcomp() (R stats) | Principal Component Analysis | Initial data exploration and visualization |

| ComBat-seq | Batch effect correction | RNA-seq count data with known batches |

| limma removeBatchEffect() | Batch effect removal | Normalized expression data |

| seqQscorer | Quality assessment | Machine-learning-based sample quality prediction |

| sva package | Surrogate variable analysis | Hidden batch effect detection |

Workflow Diagrams

PCA Batch Effect Detection Workflow

Batch Effect Correction Decision Guide

Conceptual Foundations: Defining the Processes

What is Normalization?

Normalization is a foundational preprocessing step in RNA-seq data analysis that adjusts raw read counts to account for technical variations that prevent meaningful comparisons between samples. Its primary purpose is to correct for factors such as sequencing depth (the total number of reads per sample) and, in some methods, gene length [21] [22].

The core assumption underlying most between-sample normalization methods is that the majority of genes are not differentially expressed across the experimental conditions [21] [22]. Methods like TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) and RLE (Relative Log Expression) operate on this principle, calculating scaling factors to adjust library sizes so that expression levels become comparable across samples [22] [23]. Without normalization, a sample with a larger library size would appear to have higher expression for most genes, potentially obscuring true biological differences [21].

What is Batch Effect Correction?

Batch effect correction addresses a different challenge: systematic technical variations introduced when samples are processed in different batches, at different times, by different personnel, or using different sequencing platforms [24] [20] [12]. Unlike normalization, batch effect correction typically requires knowledge of the batch labels and aims to remove these non-biological variations while preserving genuine biological signals [5] [12].

These batch effects can be substantial enough to obscure true biological differences, potentially leading to false discoveries in downstream analyses like differential expression testing [24] [12]. Advanced methods like ComBat-ref use statistical models, including negative binomial distributions for RNA-seq count data, to adjust batches toward a reference with minimal dispersion [24].

Direct Comparison: Purpose, Methodology, and Stage

The table below summarizes the key distinctions between these two essential data processing steps:

| Feature | Normalization | Batch Effect Correction |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Makes samples comparable by correcting for sequencing depth and gene length [21] [22] | Removes technical variations due to different processing batches [24] [20] |

| Core Assumption | Most genes are not differentially expressed [21] [22] | Batch effects are technical, non-biological variations that can be modeled and removed [24] |

| Stage in Workflow | Earlier preprocessing step [22] [5] | Later adjustment step, often performed after normalization [22] [5] |

| Dependency | Can be performed without batch information [22] | Requires knowledge of batch labels [12] |

| Common Methods | TMM, RLE, TPM, FPKM [22] [23] | ComBat, ComBat-ref, limma's removeBatchEffect [24] [12] |

The Analytical Workflow: Sequential Implementation

A proper RNA-seq preprocessing pipeline applies normalization before batch effect correction. The following workflow diagram illustrates this sequence and its impact on data structure:

RNA-seq Preprocessing Sequence

This workflow demonstrates how normalization first creates comparable expression values, after which batch effect correction utilizes batch metadata to remove additional technical biases, ultimately producing data suitable for robust biological interpretation [22] [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

How can I detect batch effects in my data?

Batch effects are most readily identified through visualization techniques before and after correction. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is particularly valuable for this purpose. In PCA plots of uncorrected data, samples often cluster by batch rather than by biological condition [5] [25]. Similarly, t-SNE or UMAP visualizations may show separation driven by technical batches rather than biological groups [5] [12]. In one reported case, a researcher observed that control and treatment samples formed three distinct groups based on collection day rather than experimental condition, clearly indicating batch effects [25].

What are the key signs of overcorrection?

Overcorrection occurs when batch effect removal inadvertently eliminates genuine biological variation. Key indicators include [5] [12]:

- Loss of expected markers: Canonical cell-type or condition-specific markers fail to appear as differentially expressed

- Poor cluster specificity: Cluster-specific markers show substantial overlap between distinct cell types

- Non-biological markers: A high proportion of cluster markers comprise ubiquitously expressed genes (e.g., ribosomal genes)

- Diminished differential expression: Few or no significant hits in pathways expected to show differences based on experimental design

Which method should I choose for bulk RNA-seq?

Method selection depends on your dataset characteristics and experimental design:

- ComBat/ComBat-ref: Effective when batch information is clearly defined, using empirical Bayes framework to adjust for known batch variables [24] [12]

- limma's removeBatchEffect: Suitable for known, additive batch effects; integrates well with differential expression workflows [12]

- SVA (Surrogate Variable Analysis): Useful when batch variables are unknown or partially observed; estimates hidden sources of variation [12]

How do I validate successful batch effect correction?

Effective correction should be assessed using both visual and quantitative approaches. Visually, PCA and UMAP plots should show improved mixing of samples from different batches while maintaining separation by biological condition [5] [12]. Quantitative metrics provide objective validation, with effective correction indicated by [26] [12]:

- High scores (closer to 1): ARI (Adjusted Rand Index), LISI (Local Inverse Simpson's Index)

- Low scores: ASW_batch (Average Silhouette Width for batch)

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The table below catalogues key computational tools and their applications in RNA-seq data preprocessing:

| Tool/Method | Primary Function | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| edgeR (TMM) | Between-sample normalization | Corrects for differences in sequencing depth [22] [23] |

| DESeq2 (RLE) | Between-sample normalization | Adjusts for library size variations using median ratios [23] |

| ComBat-ref | Batch effect correction | Adjusts multiple batches toward a low-dispersion reference batch [24] |

| limma | Batch effect correction | Removes known batch effects using linear models [12] |

| SVA | Batch effect correction | Identifies and adjusts for unknown sources of variation [12] |

Experimental Design: Proactive Batch Effect Management

While computational correction is valuable, the most effective approach to batch effects is proactive experimental design [12]:

- Randomization: Distribute biological conditions across all processing batches

- Balancing: Ensure each biological group is represented in each batch

- Replication: Include multiple replicates per condition in each batch

- Consistency: Use consistent reagents, protocols, and personnel throughout the study

- Metadata Collection: Meticulously document all potential batch variables for later correction

Proper experimental design significantly reduces technical confounding and enhances the reliability of computational correction methods [12].

Batch Correction Methodologies: From Traditional to Cutting-Edge Approaches

Batch effects represent systematic technical variations that can confound results in bulk RNA sequencing experiments. These non-biological variations arise from differences in experimental conditions such as sequencing runs, reagent batches, personnel, or laboratory environments [11]. Within bulk RNA-seq research, linear regression-based methods provide statistically robust approaches for mitigating these technical artifacts while preserving biological signals of interest. This technical support center focuses on two prominent linear regression-based methods: removeBatchEffect() from the limma package and rescaleBatches() from the batchelor package, providing troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols for researchers and drug development professionals implementing these methods within their batch effect correction workflows.

Method Specifications and Comparative Analysis

Technical Specifications

Table 1: Core functional specifications of removeBatchEffect() and rescaleBatches()

| Parameter | removeBatchEffect() | rescaleBatches() |

|---|---|---|

| Input Data | Numeric matrix of log-expression values [27] | Log-expression matrices or SingleCellExperiment objects [28] |

| Batch Arguments | Factor/vector for batch; optional second batch factor [27] | Multiple objects (one per batch) or batch factor for single object [28] |

| Covariate Support | Matrix/vector of numeric covariates [27] | Not directly supported |

| Design Matrix | Required to preserve treatment conditions [27] | Not applicable |

| Return Value | Numeric matrix of corrected log-expression values [27] | SingleCellExperiment with corrected assay [28] |

| Primary Use Case | Preparing data for visualization or unsupervised analyses [27] | Scaling counts across batches with similar cell populations [29] |

Algorithmic Workflows

Figure 1: Algorithmic workflows for removeBatchEffect() and rescaleBatches() methods

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: removeBatchEffect() Implementation

Preprocessing Requirements:

- Normalize raw count data using TMM (edgeR) or variance stabilizing transformation (DESeq2) [11]

- Convert normalized counts to log-counts-per-million (log-CPM) values

- Ensure batch information is encoded as factor variables

Implementation Code:

Critical Considerations:

- Always specify a design matrix that includes biological factors of interest to prevent their removal [27]

- For complex designs with multiple technical covariates, use the

covariatesparameter [30] - The function is not recommended for use prior to differential expression analysis; instead include batch in the linear model [27] [31]

Protocol 2: rescaleBatches() Implementation

Preprocessing Requirements:

- Perform log-transformation of normalized count data with known pseudo-count [28]

- Ensure all batches contain the same genes in the same order

- Verify assumption of similar cell population compositions across batches [29]

Implementation Code:

Critical Considerations:

- Method assumes identical population composition across batches [29]

- Effectively addresses scaling differences but preserves other batch-associated variances

- Particularly useful when batch effects manifest as systematic scaling differences [28]

Troubleshooting Guide

FAQ 1: When should I use removeBatchEffect() versus including batch in my linear model?

Problem: Uncertainty about whether to correct data prior to analysis or include batch in statistical models.

Solution: The removeBatchEffect() function is specifically intended for preparing data for visualization or unsupervised analyses such as PCA, clustering, or heatmaps [27]. For differential expression analysis, it is statistically preferable to include batch as a covariate in your linear model rather than pre-correcting the data [31]. For example, in DESeq2 or edgeR, include batch in the design formula (e.g., design = ~batch + treatment) rather than using removeBatchEffect() before analysis.

FAQ 2: Why does my PCA plot still show batch effects after using removeBatchEffect()?

Problem: Incomplete batch effect removal visualized in dimensionality reduction plots.

Solution: This issue can stem from several causes:

- Insufficient batch specification: Ensure all relevant batch factors are included. For complex batch structures, consider using the

batch2parameter for independent batch effects orcovariatesfor continuous technical variables [27] [30]. - Incorrect design matrix: Verify your design matrix properly specifies biological conditions to preserve. An underspecified design may remove biological variance along with batch effects.

- Strong batch-biology confounding: When batch effects are completely confounded with biological conditions, complete removal is statistically challenging [31].

- Visualization artifacts: Ensure PCA is performed on the corrected matrix rather than the original data.

FAQ 3: How do I handle continuous covariates in batch effect correction?

Problem: removeBatchEffect() expects categorical batch variables by default.

Solution: The function accepts continuous covariates through the covariates parameter [30]. For example, to correct for bisulfite conversion efficiency (a continuous variable) in methylation data:

This functionality enables correction for continuous technical variables such as conversion efficiency, RNA integrity numbers, or other quantitative quality metrics.

FAQ 4: What are the indications of over-correction and how can I avoid it?

Problem: Batch effect correction removes biological signals along with technical artifacts.

Solution: Over-correction manifests as:

- Distinct cell types clustering together in dimensionality reduction plots [13]

- Complete overlap of samples from different biological conditions

- Loss of known biological markers in downstream analyses

Prevention strategies:

- Always specify a design matrix that protects biological variables of interest

- Compare corrected and uncorrected visualizations to ensure biological separation is maintained

- Use conservative parameter settings initially and gradually increase correction strength

- Validate with positive control genes known to be biologically relevant

FAQ 5: How do I validate that batch correction has been effective?

Problem: Uncertainty about assessing batch correction success.

Solution: Implement a multi-faceted validation approach:

- Visual inspection: Examine PCA plots pre- and post-correction with points colored by batch [11] [25]. Successful correction shows intermingling of batches.

- Quantitative metrics: Utilize metrics like ASW (average silhouette width) or LISI (local inverse Simpson's index) to quantify batch mixing [13].

- Biological preservation: Verify that known biological differences remain detectable after correction.

- Negative controls: Ensure batch-associated genes (identified in pre-correction analysis) no longer show significant association with batch.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential computational tools for batch effect correction in bulk RNA-seq

| Tool/Package | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| limma | removeBatchEffect() function | Linear model-based batch effect removal for visualization [27] |

| batchelor | rescaleBatches() function | Count scaling across batches for single-cell and bulk data [28] |

| edgeR | TMM normalization, model fitting | Differential expression analysis with batch covariates [11] |

| sva | ComBat, ComBat-seq | Empirical Bayes batch effect adjustment [11] |

| DESeq2 | Generalized linear models | Differential expression with batch factors in design formula [31] |

Advanced Integration Strategies

Complex Experimental Designs

For studies with multiple batch effects and biological covariates, a combined approach often yields optimal results:

Figure 2: Decision framework for batch effect correction method selection

Method Selection Guidelines

Choose removeBatchEffect() when:

- Dealing with strong, categorical batch effects

- Need to preserve specific biological conditions via design matrix

- Preparing data specifically for visualization or exploratory analysis

Choose rescaleBatches() when:

- Batch effects manifest primarily as scaling differences

- Population composition is similar across batches

- Working with log-transformed count data

For differential expression analysis, include batch in the model rather than pre-correcting:

Linear regression-based methods provide powerful, interpretable approaches for batch effect correction in bulk RNA sequencing research. The removeBatchEffect() function offers precise control over which factors to preserve and remove, while rescaleBatches() provides a robust scaling approach for count data. Implementation requires careful consideration of experimental design, appropriate parameter specification, and thorough validation to ensure successful technical artifact removal without compromising biological signals. By adhering to the protocols and troubleshooting guidelines presented herein, researchers can effectively address batch effects while maintaining the integrity of their biological findings.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between ComBat and ComBat-seq? A1: ComBat is designed for continuous, normalized data from platforms like microarrays, assuming a log-normal distribution. In contrast, ComBat-seq is specifically for raw count data from RNA-sequencing experiments, which it models using a negative binomial distribution, thereby preserving the integer nature of the counts for downstream analysis with tools like DESeq2 and edgeR [32] [11].

Q2: My data still shows batch effects after running ComBat-seq. What could be wrong? A2: This can occur for several reasons:

- Incorrect Input: ComBat-seq requires raw, unnormalized count data as input. Providing normalized data (e.g., TPM, FPKM) will lead to incorrect results [33].

- Weak or No Batch Effect: If the batch effect is minimal to begin with, the correction will not dramatically alter your data. Always visualize your data with PCA before and after correction to assess the initial batch effect [34].

- Unbalanced Design: If your biological conditions are confounded with batches (e.g., all controls in one batch and all treatments in another), it becomes statistically very difficult for any method, including ComBat-seq, to disentangle the batch effect from the biological signal [35].

Q3: Are there risks to using these batch correction methods? A3: Yes, a major risk is overfitting, especially when the study design is unbalanced. The method can over-adjust the data, artificially creating or amplifying the appearance of your biological groups of interest. This can lead to exaggerated confidence in downstream analyses. A sanity check using permuted batch labels can reveal this issue [35].

Q4: What is ComBat-ref and how does it improve upon ComBat-seq? A4: ComBat-ref is an enhancement of ComBat-seq that introduces a reference batch strategy. It selects the batch with the smallest dispersion as a reference and adjusts all other batches toward it. This approach has been shown to provide superior statistical power and better control of false positives in differential expression analysis, especially when batches have different levels of variability [24].

Q5: Should I correct my data before or account for batch during differential expression analysis? A5: The statistically safer approach is to include batch as a covariate directly in your statistical model for differential expression analysis (e.g., in DESeq2 or limma). This avoids the potential overfitting risks associated with pre-correcting the data itself. Data correction with ComBat methods is often used when you need a "batch-free" dataset for other types of analyses, like clustering or visualization, but should be done with caution [35].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: ComBat-seq correction appears to have no effect on my data. Solution:

- Verify Input Data: Ensure you are using a matrix of raw, integer counts. Do not use log-transformed or otherwise normalized data [11] [33].

- Check for Pervasive Batch Effects: Perform PCA on the raw counts (using

plotPCAin DESeq2 after variance-stabilizing transformation) to confirm a batch effect exists. If samples don't separate by batch in the pre-correction PCA, there may be little for ComBat-seq to correct [34]. - Inspect Model Parameters: Double-check that the

batchandgroupfactors you are providing to theComBat_seqfunction are correctly specified.

Problem 2: I get warnings or errors when running ComBat in Scanpy (single-cell data). Solution: The warnings often relate to internal numerical operations (like "divide by zero" or Numba compilation warnings). While they may not always indicate a complete failure, they can be symptomatic of issues.

- Standardization Warning ("Found 0 numerical variables"): This can indicate an issue with how the data matrix is entered.

- Numba/Convergence Warnings: These are often internal to the algorithm. However, if your downstream clustering results are poor (e.g., batches remain separate), it suggests the correction did not work effectively. In such cases, consider alternative batch integration methods provided by Scanpy, such as

scvi-toolsorHarmony[36].

Problem 3: After batch correction, my biological signal seems too good to be true. Solution:

- Perform a Permutation Test: This is a critical sanity check. Shuffle your batch labels and re-run ComBat. If you still get perfect clustering by biological group after this random shuffling, it indicates the method is overfitting and you cannot trust the result [35].

- Prefer Modeling over Correction: If your design is unbalanced, the most robust solution is to avoid pre-correcting the data altogether. Instead, include the batch factor as a covariate in a linear model during differential expression testing using established frameworks like

limmaorDESeq2[35].

Experimental Protocols & Validation

The following protocols outline how to validate the performance and efficacy of ComBat methods, which is crucial for any thesis methodology chapter.

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Batch Effect Correction Power

Objective: To quantitatively and visually assess the effectiveness of ComBat, ComBat-seq, and ComBat-ref in removing technical batch variation while preserving biological signal.

Materials and Reagents:

- Meta-dataset: A publicly available dataset comprising several smaller datasets merged together, ensuring known batch and biological labels. Examples include the Breast Cancer and Colon Cancer datasets used in the pyComBat validation [32] or the GFRN/NASA GeneLab data used for ComBat-ref [24].

- Software Tools: R (with

sva,limma,edgeRpackages) or Python (withinmoose/pyComBatpackage). - Computational Environment: Standard desktop or high-performance computing cluster.

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Download the constituent datasets and merge them into a single count matrix.

- Annotate samples with their respective batch and biological condition labels.

- For microarray-style data (ComBat), normalize with RMA or a similar method. For RNA-seq data (ComBat-seq/ComBat-ref), use raw counts [32].

- Batch Effect Correction:

- Apply each of the three methods (

ComBat,ComBat-seq, andComBat-ref) to the merged dataset using the known batch labels. - For ComBat-seq and ComBat-ref, the biological condition can be provided as the

groupparameter to protect it during correction.

- Apply each of the three methods (

- Evaluation:

- Visual Inspection: Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the data before and after correction. Plot PC1 vs. PC2, coloring points by batch and shaping points by biological condition. Successful correction is indicated by the mixing of batches while biological conditions remain separable [32] [37].

- Quantitative Metrics: For a more rigorous benchmark, calculate the Relative Squared Error between the output of a new implementation (e.g., pyComBat) and the standard R implementation to ensure algorithmic fidelity [32].

Protocol 2: Downstream Differential Expression Analysis Validation

Objective: To ensure that slight differences in corrected data between implementations do not significantly alter biological conclusions from differential expression (DE) analysis.

Methodology:

- DE Analysis on Corrected Data:

- Using the batch-corrected data from each method, perform a DE analysis comparing biological conditions (e.g., Primary Tumors vs. Normal Tissues) with a standard tool like

limma(for ComBat-corrected data) oredgeR/DESeq2(for ComBat-seq/ComBat-ref corrected data) [32].

- Using the batch-corrected data from each method, perform a DE analysis comparing biological conditions (e.g., Primary Tumors vs. Normal Tissues) with a standard tool like

- Result Comparison:

- Extract the list of statistically significant differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using a standard threshold (e.g., FDR < 0.05 and |logFC| > 1.5).

- Compare the lists of DEGs obtained from data corrected by different ComBat implementations or methods. The overlap should be very high, indicating robust biological findings regardless of the specific tool used [32].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Key Characteristics of ComBat, ComBat-seq, and ComBat-ref

| Feature | ComBat | ComBat-seq | ComBat-ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Distribution | Log-Normal [32] | Negative Binomial [32] [24] | Negative Binomial [24] |

| Input Data Type | Normalized continuous data (e.g., log2 microarray) | Raw integer counts [32] [11] | Raw integer counts [24] |

| Reference Batch | No | No | Yes (lowest dispersion) [24] |

| Primary Application | Microarray data [32] | Bulk RNA-seq count data [32] | Bulk RNA-seq count data [24] |

| Output Data | Continuous values | Integer counts [32] | Integer counts [24] |

| Key Advantage | Handles small sample sizes, parametric & non-parametric | Preserves counts for DE tools; handles over-dispersion [32] | Improved power & specificity in DE analysis [24] |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of ComBat Implementations (Based on pyComBat Validation Study)

| Metric | R ComBat (Parametric) | Scanpy ComBat | pyComBat (Parametric) | R ComBat-Seq | pyComBat-Seq |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speed (Relative to R) | 1x (Baseline) | ~1.5x Faster | ~4-5x Faster [32] | 1x (Baseline) | ~4-5x Faster [32] |

| Correction Efficacy | High (Baseline) | High / Similar [32] | High / Similar (Mean Relative Diff. ≈ 0) [32] | High (Baseline) | Identical Output [32] |

| Downstream DE Impact | Baseline DEGs | N/A | No significant difference in DEG lists [32] | Baseline DEGs | N/A |

Methodological Workflows and Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for applying and validating Empirical Bayes batch correction methods in a research project.

Workflow for Applying Empirical Bayes Batch Correction

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function in Context | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| sva R Package | The original implementation of ComBat and ComBat-seq [32]. | Contains the ComBat and ComBat_seq functions. Essential baseline for all methods. |

| inmoose Python Package | Contains pyComBat and pyComBat-seq, a faster Python implementation [32]. | Offers equivalent correction power to R with improved computational speed. |

| limma R Package | Used for differential expression analysis of continuous data and provides the removeBatchEffect function [11]. |

An alternative to ComBat for normalized data. |

| edgeR / DESeq2 | Standard packages for differential expression analysis of count data [24] [11]. | The primary tools for which ComBat-seq and ComBat-ref prepare corrected count data. |

| Public Meta-Datasets | Provide real-world data with known batch effects for method validation [32] [37]. | e.g., GSE48035 (PolyA vs Ribo), TCGA meta-sets. Critical for benchmarking. |

| PCA Visualization | The primary diagnostic tool for visualizing batch effects and the success of their correction [37] [34]. | Should be performed before and after correction. |

Core Algorithm & Technical Specifications

What is the fundamental mathematical model behind ComBat-ref?

ComBat-ref employs a negative binomial model specifically designed for RNA-seq count data. The model accounts for both biological and technical variation using a generalized linear model (GLM) framework. For a gene ( g ) in batch ( i ) and sample ( j ), the count ( n_{ijg} ) is modeled as:

( n{ijg} \sim \text{NB}(\mu{ijg}, \lambda_{ig}) )

where ( \mu{ijg} ) is the expected expression level and ( \lambda{ig} ) is the dispersion parameter for batch ( i ) and gene ( g ). The expected expression is modeled as:

( \log(\mu{ijg}) = \alphag + \gamma{ig} + \beta{cj g} + \log(Nj) )

Here, ( \alphag ) represents the global background expression, ( \gamma{ig} ) is the batch effect, ( \beta{cj g} ) represents biological condition effects, and ( N_j ) is the library size for sample ( j ) [24].

How does the reference batch selection work?

ComBat-ref innovates by selecting a reference batch with the smallest dispersion rather than using an average dispersion across batches. The algorithm:

- Estimates a batch-specific dispersion parameter ( \lambda_i ) for each batch by pooling gene count data within the batch.

- Selects the batch with the smallest dispersion as the reference batch (e.g., batch 1).

- Preserves the count data for this reference batch without modification.

- Adjusts all other batches toward this reference batch, setting their adjusted dispersion to ( \lambda_1 ) [24].

This approach maintains high statistical power comparable to data without batch effects, even when significant variance exists in batch dispersions [24].

How does the actual adjustment process work?

For batches ( i \neq 1 ) (where batch 1 is the reference), the adjusted gene expression level ( \tilde{\mu}_{ijg} ) is computed as:

( \log(\tilde{\mu}{ijg}) = \log(\mu{ijg}) + \gamma{1g} - \gamma{ig} )

The adjusted dispersion is set to ( \tilde{\lambda}i = \lambda1 ). The adjusted count ( \tilde{n}{ijg} ) is then calculated by matching the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the original distribution ( \text{NB}(\mu{ijg}, \lambdai) ) at ( n{ijg} ) and the CDF of the adjusted distribution ( \text{NB}(\tilde{\mu}{ijg}, \tilde{\lambda}i) ) at ( \tilde{n}_{ijg} ). The method ensures zero counts remain zero and prevents adjusted counts from becoming infinite [24].

Performance Comparison & Experimental Data

How was ComBat-ref evaluated in simulation studies?

ComBat-ref was tested using realistic simulations of RNA-seq count data generated with the polyester R package. The simulation design included [24]:

- Data Structure: 500 genes, with 50 up-regulated and 50 down-regulated genes (mean fold change of 2.4).

- Experimental Design: Two biological conditions and two batches, with three samples per condition-batch combination (12 samples total).

- Batch Effects: Varied levels of batch effects using:

- meanFC: Factor altering gene expression levels in one batch (levels: 1, 1.5, 2, 2.4).

- dispFC: Factor increasing dispersion in batch 2 relative to batch 1 (levels: 1, 2, 3, 4).

- Replication: Each of the 16 experiments was repeated ten times to calculate average statistics.

Table 1: Simulation Parameters for ComBat-ref Evaluation

| Parameter | Description | Values Tested |

|---|---|---|

| Total Genes | Number of genes in simulation | 500 |

| DE Genes | Differentially expressed genes | 100 (50 up, 50 down) |

| Fold Change | Mean fold change for DE genes | 2.4 |

| Batches | Number of technical batches | 2 |

| Conditions | Number of biological conditions | 2 |

| Replicates | Samples per condition-batch combination | 3 |

| mean_FC | Batch effect on expression levels | 1, 1.5, 2, 2.4 |

| disp_FC | Batch effect on dispersion | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

How does ComBat-ref compare to other batch correction methods?

In simulation studies, ComBat-ref demonstrated superior performance, particularly in challenging scenarios with high dispersion batch effects [24]:

- When disp_FC = 1 (no dispersion differences): ComBat-seq and previous methods performed well with high True Positive Rate (TPR), while ComBat-ref showed slightly lower False Positive Rate (FPR).

- As disp_FC increased: ComBat-ref maintained significantly higher sensitivity than all other methods, including ComBat-seq and NPMatch.

- In challenging scenarios (high dispFC and meanFC): ComBat-ref maintained TPR comparable to cases without batch effects.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Batch Correction Methods

| Method | Key Approach | Performance in High disp_FC | False Positive Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat-ref | Reference batch with minimum dispersion | High sensitivity maintained | Controlled |

| ComBat-seq | Average dispersion across batches | Lower sensitivity | Slightly higher than ComBat-ref |

| NPMatch | Nearest-neighbor matching | Good TPR | High (>20% in all experiments) |

| Previous BC Methods | Various (e.g., ComBat) | Performance decreased significantly | Variable |

Troubleshooting & Implementation Guide

What are common issues when implementing ComBat-ref?

Problem: Unbalanced batch designs leading to over-correction

Issue: When batches contain unbalanced proportions of biological groups, batch correction methods including ComBat may remove biological signal along with technical variation [35].

Solution:

- Design Stage: Whenever possible, ensure balanced distribution of biological groups across batches during experimental design.

- Analysis Stage: If facing unbalanced data, account for batch in downstream statistical analysis rather than relying solely on pre-corrected "batch-free" data [35].

- Validation: Perform negative controls using permuted batches to verify that biological signals remain valid after correction [35].

Problem: High false positive rates in downstream DE analysis

Issue: Some batch correction methods can introduce artifacts that increase false discoveries.

Solution:

- Use ComBat-ref's approach of setting adjusted dispersion to the reference batch's dispersion, which enhances statistical power while controlling false positives when using FDR-adjusted p-values in tools like edgeR or DESeq2 [24].

- Always use false discovery rate (FDR) rather than unadjusted p-values for statistical testing in downstream analysis [24].

Problem: Choosing between parametric vs. non-parametric estimation

Issue: Incorrect choice of estimation method can lead to suboptimal batch correction.

Solution:

- Use prior plots to check if kernel density estimates (black line) and parametric estimates (red line) of batch effects overlap.

- If lines do not overlap well, use the non-parametric method, which makes no distributional assumptions but takes longer to run [38].

What preprocessing steps are required before applying ComBat-ref?

- Input Data: ComBat-ref requires raw count data as input and returns batch-corrected raw counts [39].

- Normalization: Do not normalize data before ComBat-ref. Apply standard normalization (e.g., for DESeq2 or edgeR) after obtaining corrected counts [39].

- Data Formatting: Ensure unique row identifiers and properly formatted sample information files with exact column labels: "Array", "Sample", and "Batch" [38].

Workflow Visualization

ComBat-ref Algorithm Workflow

Researcher's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents & Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Resources for ComBat-ref Implementation

| Resource Type | Specific Tool/Format | Role in ComBat-ref Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R Programming Environment | Primary platform for method implementation |

| Simulation Tool | polyester R Package | Generate realistic RNA-seq count data for validation |

| DE Analysis Tools | edgeR, DESeq2 | Downstream analysis with batch-corrected counts |

| Input Format | Raw Count Matrix | Required input format (genes × samples) |

| Metadata Format | Sample Information File | Tab-delimited file with batch and covariate information |

| Validation Approach | Permuted Batch Controls | Negative controls to verify biological signals |

Key Parameters for Successful Implementation

- Reference Batch Selection: Always validate that the selected reference batch truly has the smallest dispersion across major gene groups.

- Dispersion Estimation: Use pooled gene count data within each batch for robust dispersion parameter estimation.

- Model Specification: Include all relevant biological covariates in the GLM specification to prevent removal of biological signal.

- Downstream Analysis: Use FDR-adjusted p-values rather than unadjusted p-values when testing for differential expression after correction.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between "accounting for" and "removing" a batch effect?

- Answer: "Accounting for" a batch effect involves including batch as a covariate in your statistical model during differential expression analysis. The underlying data is not modified; instead, the statistical inferences (e.g., p-values, fold changes) are adjusted to account for the batch variable [40]. This is the standard and recommended approach for differential expression testing in tools like DESeq2 and edgeR. In contrast, "removing" a batch effect involves mathematically transforming the expression data itself to eliminate the technical variation before downstream analysis. This is often necessary for other analyses like clustering or machine learning [40].

FAQ 2: How do I correctly set up the design formula in DESeq2 to adjust for batch effects?

- Answer: When creating your DESeq2 object, you should specify a design formula that includes both your batch variable and your primary condition of interest. It is crucial that your experimental design is not confounded, meaning that each batch must contain replicates of each biological condition [41] [40].

FAQ 3: I am getting a "model matrix is not full rank" error in DESeq2. What does this mean and how can I fix it?

- Answer: This error occurs when one or more variables in your design formula are linear combinations of each other, making the model unsolvable [40]. A common cause is a confounded design where a specific biological condition is perfectly aligned with a single batch (e.g., all "Control" samples are in "batch1" and all "Treated" samples are in "batch2"). To fix this, you must ensure your experimental design includes all conditions represented in every batch. If the design is confounded, batch correction using this method becomes impossible [37].

FAQ 4: How can I visually check for batch effects in my data and validate that the correction worked?

- Answer: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is the most common method. Before correction, you create a PCA plot from your normalized counts (e.g., using

vstin DESeq2) and color the points by batch. If samples cluster strongly by batch rather than biological condition, a batch effect is present [11] [37]. After "accounting for" batch in your DESeq2 model, the statistical output is corrected, but the PCA plot of the counts will look the same. To create a "corrected" plot for visualization, you can apply theremoveBatchEffectfunction from thelimmapackage to the transformed counts (e.g., VST or log counts), and then re-run the PCA [40].

FAQ 5: Is it acceptable to use batch-corrected count data (e.g., from ComBat-seq) as direct input for DESeq2 or edgeR?

- Answer: No, it is generally not recommended. Differential expression tools like DESeq2 and edgeR are specifically designed to model raw count data using distributions like the negative binomial. Feeding them pre-corrected data can disrupt their internal modeling of variance and lead to unreliable statistical inferences [11] [40]. The preferred method is to provide the raw counts and include the batch in the design formula.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: My samples still cluster by batch in a PCA plot after including batch in the DESeq2 design model.

- Diagnosis: This is expected behavior. Including batch in the design formula adjusts the statistical test for differential expression but does not alter the original count matrix used for visualization [40].

- Solution: To visualize the data with the batch effect removed, use a transformation and batch removal function on the normalized data. This should only be done for visualization and exploratory analysis, not for differential expression testing.

Problem: I have an unbalanced design where one of my biological groups is missing from a batch.

- Diagnosis: This is a case of a confounded design, which makes it impossible to statistically separate the effect of the batch from the effect of the missing condition [40] [37].

- Solution: Options are limited. You can:

- Reframe your analysis: Focus on a differential expression question that can be answered within the batches that have the necessary groups.

- Use an alternative method: For exploratory purposes, methods like Surrogate Variable Analysis (SVA) that can estimate unknown sources of variation might be attempted, but they require careful validation to avoid removing biological signal [11] [12].

Comparison of Batch Adjustment Strategies

The table below summarizes the core approaches to handling batch effects in bulk RNA-seq analysis.

| Method | Description | Use Case | Key Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusion as Covariate | Includes batch as a factor in the statistical model for differential expression. Does not alter raw data. | Standard differential expression analysis. | DESeq2, edgeR, limma [11] [41] [40] |

| Direct Data Correction | Uses a statistical model to adjust the expression values to remove batch effects. | Preparing data for clustering, visualization, or machine learning [40]. | ComBat-seq (for counts), limma::removeBatchEffect (for normalized data) [11] [24] |

| Advanced / Reference-Based | Selects a high-quality reference batch and aligns other batches to it, aiming to improve power. | Integrating batches with widely different technical variances. | ComBat-ref [24] |

Experimental Protocols for Covariate Adjustment

Protocol 1: Standard Batch Adjustment in a DESeq2 Workflow

This protocol details the primary method for performing differential expression analysis while accounting for known batch effects.

- Data Input: Start with a raw count matrix and a metadata table that includes both the

conditionandbatchfor each sample. - Create DESeq2 Object: Construct the DESeqDataSet with a design formula that includes

batchbeforecondition. - Run Differential Expression Analysis: Execute the standard DESeq2 pipeline.

- Extract Results: Query the results for the comparison of interest. The statistics will now be adjusted for the

batcheffect.

Protocol 2: Standard Batch Adjustment in an edgeR Workflow

This protocol outlines the equivalent procedure using the edgeR package.

- Create DGEList: Generate a DGEList object containing the raw counts and sample metadata.

- Calculate Normalization Factors: Apply TMM normalization to account for library composition.

- Define Model and Estimate Dispersions: Create a design matrix that includes the batch and condition, then estimate the common, trended, and tagwise dispersions.

- Perform Model Fit and Testing: Fit a generalized linear model and conduct a likelihood ratio test for differential expression.

Workflow Diagram for Batch Effect Management

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for diagnosing and handling batch effects in a bulk RNA-seq analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The table below lists key computational tools and their functions for managing batch effects in bulk RNA-seq.