Bulk RNA Sequencing for Fusion Gene Detection: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Clinicians

Fusion genes are critical drivers in cancer and other diseases, serving as vital diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Bulk RNA Sequencing for Fusion Gene Detection: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Clinicians

Abstract

Fusion genes are critical drivers in cancer and other diseases, serving as vital diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets. This article provides a comprehensive overview of using bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) for fusion gene detection, addressing the needs of researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational principles of RNA-seq technology, detail robust methodological workflows and computational tools, address common challenges with optimization strategies, and present rigorous validation frameworks. By comparing bulk RNA-seq with emerging technologies like single-cell and long-read sequencing, this guide serves as a definitive resource for implementing accurate and clinically relevant fusion detection pipelines in both research and diagnostic settings.

Understanding Fusion Genes and the Role of Bulk RNA-seq

The Biological Significance of Fusion Genes in Cancer and Disease

Fusion genes are aberrant hybrid genes formed from the concatenation of two previously separate genes, typically resulting from chromosomal rearrangements such as translocations, interstitial deletions, or chromosomal inversions [1]. These genetic alterations are now recognized as pivotal players in cancer development, with their products functioning as key drivers of tumorigenesis in a wide spectrum of malignancies [2] [3]. The hybrid genes resulting from these rearrangements often display altered functions, leading to uncontrolled proliferation, evasion of cell death, and enhanced metastatic potential [3].

The discovery of fusion genes has revolutionized cancer diagnostics, allowing for more precise classification and prognostic assessments [3]. From a therapeutic perspective, fusion genes represent valuable targets for drug development, with targeted therapies significantly improving survival rates in specific cancers such as chronic myeloid leukemia and non-small cell lung cancer compared to traditional chemotherapy [3]. The advent of advanced sequencing technologies and sophisticated bioinformatics tools has dramatically accelerated the identification and characterization of these genetic anomalies, paving the way for their utilization in precision medicine approaches [2] [4].

Biogenesis and Functional Mechanisms

Fusion genes arise through several distinct molecular mechanisms, each with profound implications for their functional consequences. Chromosomal translocations represent the classic mechanism, where breaks in two different chromosomes lead to an exchange of genetic material, potentially placing an oncogene under the control of a strong promoter or creating a novel chimeric protein with oncogenic properties [1]. Interstitial deletions involve the loss of an internal chromosomal segment, potentially fusing two genes that were previously separated, while chromosomal inversions occur when a chromosome segment breaks and reinserts in reverse orientation, potentially creating novel gene fusions within the same chromosome [1].

The functional consequences of fusion gene formation are equally diverse. Many oncogenic fusion genes, such as BCR-ABL in chronic myeloid leukemia, result in constitutive activation of kinase domains that drives uncontrolled cellular proliferation [2] [1]. Alternatively, fusion events can place an oncogene under the control of a strong promoter or enhancer element from the partner gene, leading to significant overexpression of the oncogene [1]. Some fusion genes, particularly those involving transcription factors like PML-RARα in acute promyelocytic leukemia, can create chimeric transcription factors that disrupt normal differentiation programs [2].

Prevalence Across Cancer Types

Fusion genes demonstrate remarkable diversity in their distribution across cancer types, with varying prevalence rates that reflect tissue-specific susceptibilities to particular chromosomal rearrangements. The table below summarizes the prevalence of clinically relevant fusion genes across selected cancer types.

Table 1: Prevalence of Fusion Genes Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Key Fusion Genes | Prevalence | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head and Neck Cancer | FGFR3-TACC3, EGFR fusions, NRG1 fusions | 2.57% (66/2564 cases) [5] | Therapeutic target with TKIs |

| Prostate Cancer | TMPRSS2-ERG | ~50% of cases [6] | Diagnostic and prognostic marker |

| Soft Tissue Tumors | ASPSCR1-TFE3 (in sarcomas) | ~33% of cases [6] | Marker for specific sarcoma subtypes |

| Leukemias | BCR-ABL, PML-RARα | Varies by subtype [2] | Paradigm for targeted therapy |

| Lung Cancer | EML4-ALK | 3-7% of NSCLC [2] | Target for ALK inhibitors |

In head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC), a comprehensive analysis of over 13,000 tumors identified clinically relevant gene fusions in approximately 2.8% of cases, with the oropharynx representing the most common anatomical site (25 out of 66 fusion-positive cases) [5]. The most frequently observed fusions involved FGFR3 (19 cases), EGFR (6 cases), FGFR2 (6 cases), and NRG1 (5 cases) [5]. Notably, 72.7% of these fusions were characterized as "Oncogenic" or "Likely Oncogenic" according to the OncoKB database, highlighting their potential clinical relevance [5].

Table 2: Distribution of Fusion Genes by Anatomical Site in HNSCC

| Anatomical Site | Number of Fusion Genes | Most Common Fusion Types |

|---|---|---|

| Oropharynx | 25 | FGFR3, EGFR fusions |

| Oral Cavity | 20 | FGFR3, FGFR2 fusions |

| Larynx | 17 | Various |

| Other Sites | 4 | Various |

Detection Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

The accurate detection and characterization of fusion genes present significant technical challenges that have driven the development of specialized methodologies and computational tools. The limitations of conventional short-read sequencing for fusion detection are particularly pronounced in repeat-rich genomic regions and for determining complex fusion isoforms [6]. Third-generation sequencing technologies, such as PacBio's Single Molecule Real Time (SMRT) sequencing, offer unique advantages through their long read lengths (>40,000 bp with average length around 10,000-15,000 bp), enabling more comprehensive characterization of fusion events [1] [6].

Hybrid Sequencing Approach (IDP-fusion)

The IDP-fusion method represents an innovative hybrid sequencing approach that integrates third-generation sequencing long reads with second-generation sequencing short reads to detect fusion genes, determine fusion sites, and identify and quantify fusion isoforms [1]. This method addresses the limitations of each individual technology by combining the long-range information from PacBio sequencing with the accuracy of Illumina short reads.

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Fusion Gene Detection

| Tool Name | Sequencing Data Type | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| IDP-fusion | Hybrid (Long + Short reads) | Determines fusion sites at single-nucleotide resolution; identifies and quantifies isoforms [1] | Bulk RNA-seq |

| Anchored-fusion | Bulk and single-cell RNA-seq | High sensitivity for driver fusions; deep learning-based false positive filtering [4] | Low sequencing depth cases; scRNA-seq |

| pbfusion | PacBio Iso-Seq long reads | Flags reads spanning multiple genes; annotates transcriptional oddities [6] | Bulk and single-cell Iso-Seq data |

| STAR-Fusion | RNA-seq short reads | Optimized for sensitivity and specificity; widely used in large cohorts [5] | Large-scale cohort studies |

| Arriba | RNA-seq short reads | Fast visualization; high performance in benchmarking [5] | Clinical RNA-seq data |

Protocol: IDP-fusion for Fusion Gene Detection

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Prepare both PacBio long-read and Illumina short-read libraries from the same RNA sample.

- For PacBio sequencing, aim for sufficient coverage to detect rare fusion events (recommended minimum: 500,000 reads per sample).

- For Illumina sequencing, standard RNA-seq library preparation protocols apply, with recommended sequencing depth of at least 50 million read pairs per sample.

Fusion Gene Detection by Genome-wide Long Read Alignments:

- Align PacBio long reads to the reference genome (e.g., hg19) using GMAP.

- Examine all fragment alignments and define fusion gene candidates meeting these criteria:

- Both aligned fragments >100 bp in length.

- Fragments mapped to different chromosomes OR same chromosome with minimum distance of 100 kb OR different annotated genes.

- No significant overlap (>100 bp) between aligned fragments.

- No significant unaligned region (>100 bp) between aligned fragments.

- Filter ambiguous alignments by requiring consistent transcription strands and significant alignment identity differences (<0.2) between best and second-best alignments.

Precise Fusion Site Determination by Short Read Alignments:

- Construct Artificial Reference Sequences (ARSs) by extending each fragment alignment region by 2000 bp beyond alignment ends and concatenating.

- Align Illumina short reads to ARSs using splice-aware aligners.

- Identify precise fusion sites at single-nucleotide resolution based on spanning reads.

Fusion Isoform Identification and Quantification:

- Apply modified IDP (Isoform Detection and Prediction) to fusion gene models.

- Identify significantly expressed fusion isoforms using expression threshold (e.g., RPKM ≥10).

- Quantify isoform-level abundance for each fusion gene.

Anchored-fusion Protocol for Sensitive Detection

Anchored-fusion is a highly sensitive fusion gene detection tool designed for both bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing data, particularly valuable for cases with low sequencing depths or when targeting known driver fusion events [4].

Protocol: Anchored-fusion for Targeted Fusion Search

Data Preprocessing:

- Process raw RNA-seq data through standard quality control steps (FastQC) and adapter trimming.

Anchored Fusion Detection:

- Specify a "gene of interest" often involved in driver fusion events.

- The algorithm anchors this gene and recovers non-unique matches of short-read sequences typically filtered out by conventional algorithms.

- Apply the hierarchical view learning and distillation (HVLD) deep learning module to filter false positive chimeric fragments generated during sequencing while maintaining true fusion genes.

Output and Validation:

- Review fusion calls with supporting read counts and fusion sequence details.

- For clinical applications, prioritize fusions with known oncogenic potential or those classified as "Oncogenic" or "Likely Oncogenic" in databases like OncoKB.

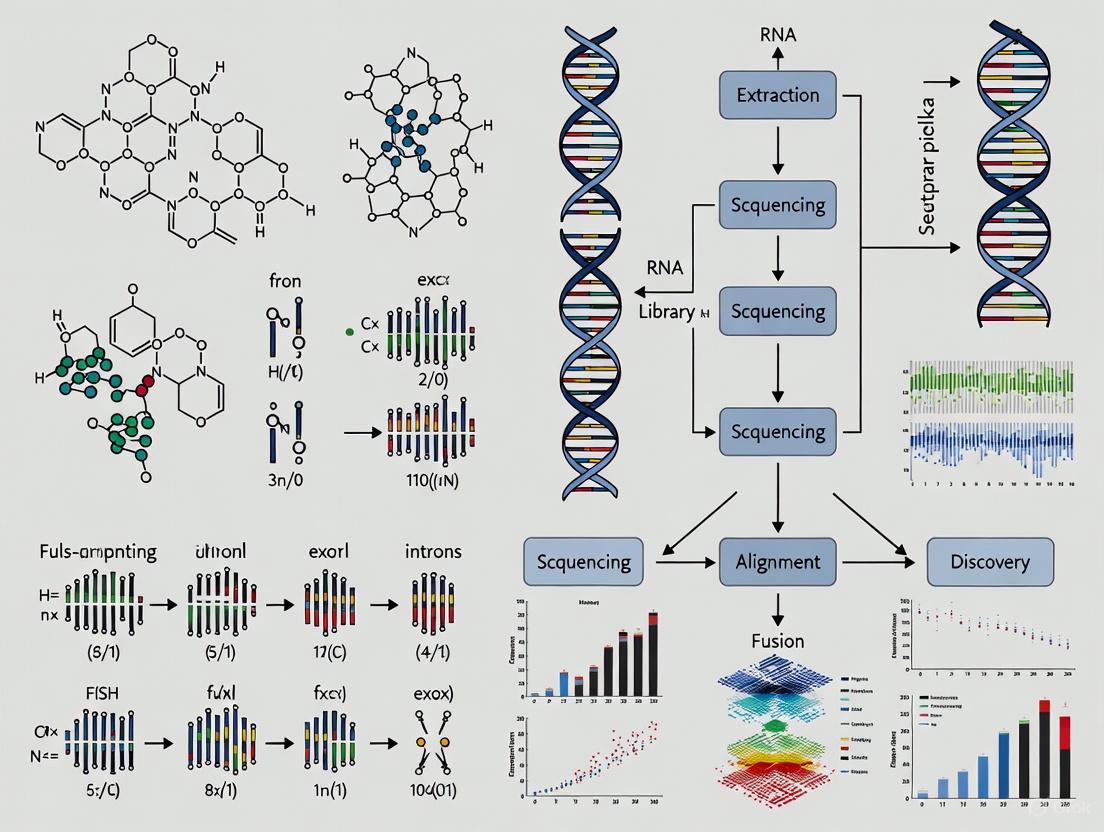

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points and methodologies in fusion gene detection:

Signaling Pathways and Therapeutic Targeting

Oncogenic fusion genes typically exert their effects through the dysregulation of critical signaling pathways that control cellular growth, differentiation, and survival. The most well-characterized mechanisms involve constitutive activation of kinase signaling, transcriptional dysregulation, and altered regulatory circuits.

The BCR-ABL fusion gene, resulting from the Philadelphia chromosome translocation, produces a chimeric protein with constitutively active tyrosine kinase activity that drives chronic myeloid leukemia [1]. This aberrant kinase activity activates multiple downstream pathways including JAK-STAT, MAPK, and PI3K-AKT, leading to uncontrolled proliferation and resistance to apoptosis [1]. Similarly, the EML4-ALK fusion in non-small cell lung cancer creates a cytoplasmic protein with constitutive ALK kinase activity that activates similar growth and survival pathways [2].

The following diagram illustrates key signaling pathways dysregulated by oncogenic fusion genes:

Therapeutic Implications and Clinical Translation

The unique nature of fusion genes makes them ideal tumor-specific drug targets [1]. The development of imatinib (Gleevec), which targets the BCR-ABL fusion protein in chronic myeloid leukemia, represents a paradigm of successful targeted therapy and has transformed CML from a fatal disease to a manageable chronic condition for many patients [1]. Similarly, ALK inhibitors such as crizotinib have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in patients with ALK fusion-positive lung cancers [2].

In head and neck cancers, the identification of targetable fusions presents new therapeutic opportunities. FGFR3 fusions, particularly FGFR3-TACC3, represent the most common targetable fusion class in HNSCC, with several FGFR inhibitors currently in clinical development or approved for other indications [5]. Notably, gain-of-function EGFR fusions have been identified in HNSCC, with literature evaluation showing that among 17 patients with various EGFR fusion-positive cancers who received EGFR TKI therapy, 15 achieved partial responses, one had a complete response, and one had stable disease [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful investigation of fusion genes requires carefully selected reagents and methodologies. The following table details essential materials and their applications in fusion gene research.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Fusion Gene Studies

| Category | Specific Reagents/Tools | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Kits | PacBio Iso-Seq library prep kits, Illumina RNA-seq library prep kits | Generation of sequencing libraries for long-read and short-read approaches [1] [6] |

| Computational Tools | IDP-fusion, Anchored-fusion, pbfusion, STAR-Fusion, Arriba | Detection of fusion genes from various sequencing data types [4] [1] [5] |

| Reference Databases | RefSeq, OncoKB, GENIE | Annotation of fusion events and determination of clinical relevance [1] [5] [6] |

| Cell Lines | MCF-7 breast cancer cells, known fusion-positive cell lines | Positive controls for method validation [1] |

| Targeted Inhibitors | Imatinib (BCR-ABL), Crizotinib (ALK), FGFR inhibitors | Functional validation of fusion gene oncogenicity and therapeutic applications [1] [5] |

Fusion genes represent critical molecular events in carcinogenesis with profound basic science and clinical implications. Their study has been revolutionized by advanced sequencing technologies and sophisticated computational tools that enable comprehensive characterization of these complex genetic alterations. The biological significance of fusion genes extends from their roles as drivers of oncogenic processes to their potential as highly specific therapeutic targets.

Future research directions will likely focus on overcoming current challenges, including the functional characterization of novel fusion events, understanding their interactions with tumor microenvironments, and elucidating mechanisms of resistance to fusion-targeted therapies. The continued refinement of therapeutic strategies through next-generation inhibitors and rational combination therapies tailored to specific genetic alterations will further enhance the clinical impact of fusion gene research. As the landscape of cancer treatment evolves, fusion genes stand at the forefront of precision medicine, offering new hope for patients through the transformation of genetic anomalies into therapeutic opportunities.

In the field of precision oncology, accurate detection of gene fusions is critical for diagnosis, prognosis, and selection of targeted therapies. While DNA sequencing (DNA-seq) has been the traditional approach for identifying genomic rearrangements, bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) provides distinct advantages for capturing transcript-level evidence that more accurately reflects functional gene expression [7]. This Application Note examines the comparative strengths of bulk RNA-seq and DNA-seq for fusion gene detection, providing detailed protocols and data-driven insights for researchers and drug development professionals.

Gene fusions are hybrid genes formed from the rearrangement of previously separate genes, often serving as drivers in various cancers [8]. These molecular events can lead to the production of oncogenic proteins that promote tumor growth and survival. The detection of these fusions is complicated by biological and technical factors, including diverse breakpoint locations, variable expression levels, and the limitations of different detection platforms [9] [10].

Bulk RNA-seq bridges the critical gap between DNA mutations and protein expression by directly sequencing the transcriptome, thus confirming whether a genomic rearrangement is actually expressed [7]. This transcript-level evidence is particularly valuable for clinical decision-making, as it focuses on functionally relevant alterations that are more likely to be therapeutically actionable.

Technical Comparison: Bulk RNA-seq vs. DNA Sequencing

Fundamental Differences in Approach

DNA sequencing identifies structural variants and breakpoints at the genomic level, providing information about the potential for gene fusions to occur. It detects rearrangements regardless of whether the altered gene is transcribed or expressed [7]. Common DNA-based approaches include whole-genome sequencing (WGS), whole-exome sequencing, and targeted DNA panels. However, DNA-seq has limitations in fusion detection due to unpredictable breakpoint locations, large intronic regions, and the inability to distinguish expressed fusions from silent rearrangements [9].

Bulk RNA sequencing directly sequences the transcriptome, capturing only expressed gene fusions. This provides functional evidence of the fusion's activity and often enables more straightforward detection of the resulting chimeric transcript [8]. RNA-seq can identify fusion transcripts even when genomic breakpoints occur in difficult-to-sequence regions, as the intronic sequences are spliced out during mRNA processing [11].

Comparative Performance Data

Recent studies have quantitatively compared the performance of DNA-seq and RNA-seq for fusion detection in clinical samples. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from published studies:

Table 1: Comparative Performance of DNA-seq and RNA-seq in Fusion Detection

| Study Context | DNA-seq Detection Rate | RNA-seq Detection Rate | Concordance | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RET fusions in NSCLC (n=39) | 100% (by selection) | 79.5% (WTS), additional cases with targeted RNA-seq | 92.3% between DNA-seq and RNA-seq | Targeted RNA-seq identified additional RET+ cases missed by WTS | [9] |

| Gene fusions in solid tumors (n=60) | 93.4% concordance with previous results | 86.9% concordance with previous results | 100% after integrating both methods | DNA and RNA results complemented each other, reducing false negatives | [11] |

| Acute leukemia (n=467) | N/A (OGM used instead) | 9.4% uniquely identified by RNA-seq | 88.1% overall concordance | RNA-seq better for fusions from intrachromosomal deletions | [10] |

| Expressed mutation detection | Varied by panel design | Identified clinically relevant variants missed by DNA-seq | N/A | RNA-seq uniquely identified variants with significant pathological relevance | [7] |

The data demonstrate that DNA-seq and RNA-seq have complementary strengths, with integrated approaches achieving the most comprehensive fusion detection. RNA-seq particularly excels in confirming the functional expression of fusion events and identifying those that may be missed by DNA-based methods due to technical or biological factors.

Advantages of Bulk RNA-seq for Transcript-Level Evidence

Functional Relevance: RNA-seq directly sequences the transcriptome, confirming that a fusion gene is expressed and likely to produce a functional protein [7]. This is crucial for clinical decision-making, as not all genomic rearrangements lead to expressed fusion transcripts.

Simplified Detection: By sequencing spliced mRNAs, RNA-seq avoids the challenges of large intronic regions and complex genomic architectures that complicate DNA-based fusion detection [11]. The breakpoints in cDNA are typically more concentrated and predictable.

Enhanced Sensitivity for Certain Fusions: Some gene fusions are more readily detected at the RNA level, particularly those involving large intronic regions or complex rearrangements [9]. Targeted RNA-seq approaches can provide particularly sensitive detection of expressed fusions.

Comprehensive Transcript Information: Beyond fusion detection, RNA-seq provides additional information about expression levels, alternative splicing, and sequence variants within the fusion transcript [8].

Experimental Protocols

Integrated DNA-RNA Sequencing Protocol for Fusion Detection

This protocol describes a validated approach for simultaneous DNA and RNA sequencing from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples, enabling complementary fusion detection [11].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen) | Genomic DNA extraction from FFPE samples | Ensures high-quality DNA despite cross-linking from fixation |

| KAPA Hyper Prep Kit (KAPA Biosystems) | NGS library preparation for DNA sequencing | Compatible with degraded FFPE-derived DNA |

| GeneseeqPrime 425-gene panel | Targeted DNA sequencing | Covers known fusion partners and cancer-related genes |

| Archer Analysis Software v6.2.7 | Fusion transcript identification | Specifically designed for targeted RNA-seq data |

Workflow Steps:

Nucleic Acid Extraction:

- Extract genomic DNA from FFPE samples using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue kit [9].

- Extract total RNA from adjacent sections or the same sample, assessing RNA quality and integrity.

DNA Sequencing Library Preparation:

RNA Sequencing Library Preparation:

- Convert total RNA to cDNA using reverse transcriptase.

- Prepare libraries using targeted approaches (e.g., anchored multiplex PCR) that capture known and novel fusion partners [10].

- Sequence on Illumina platforms with sufficient depth for transcript quantification.

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- For DNA-seq: Align reads to reference genome (hg19/GRCh37) using BWA-MEM [9]. Call structural variants and fusions using tools like Delly [9].

- For RNA-seq: Identify fusion transcripts using specialized algorithms (Archer, CTAT-LR-Fusion, or DEEPEST) [10] [8].

- Integrate results from both approaches to validate fusions and reduce false positives/negatives.

Validation:

- Confirm novel or questionable fusions using orthogonal methods such as Sanger sequencing, FISH, or RT-PCR [11].

Integrated DNA-RNA Sequencing Workflow

Targeted RNA-seq Protocol for Expressed Mutation Detection

Targeted RNA-seq offers enhanced sensitivity for detecting expressed mutations and fusions, making it particularly valuable for clinical applications [7].

Workflow Steps:

Sample Preparation:

- Generate high-quality single-cell suspensions from fresh or frozen tissue using enzymatic or mechanical dissociation [12].

- Assess cell viability and count using trypan blue exclusion or automated cell counters.

- Extract total RNA, ensuring minimal degradation (RIN > 7 for optimal results).

Library Preparation with Targeted Enrichment:

- Use targeted RNA-seq panels (e.g., Afirma Xpression Atlas, 108-gene heme panel) designed with exon-exon junction covering probes [7] [10].

- Employ anchored multiplex PCR (AMP) chemistry that uses unidirectional gene-specific primers to capture novel fusion partners [10].

- Incorporate unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to correct for amplification biases and enable accurate quantification.

Sequencing:

- Sequence on Illumina platforms with appropriate read length (2x150bp recommended) and depth (minimum 20M reads per sample for targeted approaches).

- Include control samples with known fusion status for quality assessment.

Bioinformatic Analysis for Fusion Detection:

- Align reads to reference transcriptome using optimized splice-aware aligners (STAR, HISAT2).

- Implement specialized fusion detection algorithms (Archer, JAFFAL, FusionCatcher) with stringent filtering.

- Annotate fusions with clinical relevance and known drug targets.

- Control false positive rates using known negative position lists and statistical filtering [7].

Advanced Applications and Emerging Technologies

Complementary Approaches for Comprehensive Fusion Detection

While bulk RNA-seq provides critical transcript-level evidence, the most comprehensive fusion detection strategies integrate multiple complementary technologies:

Table 3: Multi-Modal Approaches to Fusion Detection

| Technology | Strengths | Limitations | Complementary Role with RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA-seq | Identifies genomic breakpoints; detects fusions regardless of expression | May miss fusions in complex genomic regions; cannot confirm expression | Provides genomic confirmation of RNA-identified fusions |

| RNA-seq | Confirms functional expression; avoids intronic complexity | Limited by gene expression levels; RNA degradation in FFPE | Primary method for detecting expressed fusions |

| FISH | Visual confirmation; single-cell resolution; works well on FFPE | Low throughput; limited to known targets | Validates fusions in tissue context; confirms rearrangement |

| OGM | Genome-wide view; detects structural variants | Cannot confirm transcription | Identifies rearrangements that may be missed by targeted approaches |

Recent studies demonstrate that combining DNA-seq and RNA-seq significantly improves fusion detection sensitivity and specificity. In one study of solid tumors, an integrated DNA-RNA sequencing approach achieved 100% sensitivity and specificity, identifying additional fusions missed by either method alone [11]. Similarly, in acute leukemia, combining targeted RNA-seq with optical genome mapping (OGM) provided the most comprehensive assessment of gene rearrangements, with each method uniquely identifying clinically significant events [10].

Computational Tools for Fusion Detection

Advanced computational methods are critical for accurate fusion detection from RNA-seq data. Emerging tools address specific challenges in fusion identification:

- CTAT-LR-Fusion: Detects fusion transcripts from long-read RNA-seq data, providing improved resolution of fusion isoforms [13].

- Anchored-fusion: A highly sensitive tool that anchors genes of interest to recover sequences typically filtered out by conventional algorithms, particularly useful for low-abundance fusions [14].

- DEEPEST: A statistical framework that minimizes false positives while maintaining sensitivity in bulk RNA-seq data [8].

These tools can be integrated into comprehensive pipelines that combine short-read and long-read sequencing data to maximize fusion detection sensitivity and accuracy.

Computational Fusion Detection Pipeline

Bulk RNA-seq provides critical advantages over DNA sequencing for obtaining transcript-level evidence of gene fusions in cancer research. By directly sequencing expressed transcripts, RNA-seq confirms the functional relevance of fusion events and enables detection of clinically actionable alterations that may be missed by DNA-based methods alone. The integrated protocol presented here, combining DNA and RNA sequencing approaches, offers researchers a comprehensive strategy for fusion detection with enhanced sensitivity and specificity.

As precision medicine continues to evolve, multi-modal approaches that leverage the complementary strengths of DNA and RNA sequencing will become increasingly important for patient stratification and therapeutic selection. The experimental frameworks and computational tools outlined in this Application Note provide researchers with practical methodologies for implementing these integrated approaches in both basic research and clinical translation contexts.

Gene fusions, arising from genomic rearrangements such as translocations, insertions, deletions, or inversions, are a critical class of molecular alterations in cancer [15]. They result in chimeric proteins that can act as potent oncogenic drivers, promoting tumorigenesis and cancer progression. The identification of these fusion events has moved to the forefront of precision oncology, as they serve not only as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers but also as high-value therapeutic targets for targeted therapies [15] [16]. The advent of RNA sequencing (RNAseq) technologies has been instrumental in systematically profiling these fusion genes across various cancer types, offering a comprehensive view of their landscape and clinical potential [8].

Fusion Genes as Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarkers

The presence of specific gene fusions can define distinct molecular subtypes of cancer, providing critical information for diagnosis, prognosis, and disease stratification.

Clinical Significance Across Cancers

Recurrent fusion genes have been successfully established as biomarkers in several malignancies. In acute myeloid leukemia, the RUNX1–RUNX1T1 fusion is a key diagnostic tool, while the TMPRSS2–ERG fusion serves as a prognostic biomarker in prostate cancer [8]. In colorectal cancer, a study detected the known KANSL1-ARL17A/B fusion in 69% of patients, highlighting a frequently occurring event [16].

Recent research has expanded this understanding to other solid tumors. In HR+/HER2– breast cancer, the presence of fusion genes is significantly associated with poorer clinical outcomes, including shorter overall survival (OS), recurrence-free survival (RFS), and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) [15]. Similarly, in advanced melanoma, a high tumor fusion burden (TFB-H) is correlated with a poor response to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB), reduced overall survival, and an increased mortality risk (Hazard Ratio = 2, P < 0.01) [17].

Association with Genomic Instability

The prognostic power of fusion genes often stems from their association with underlying genomic instability. In HR+/HER2– breast cancer, fusion-positive tumors are correlated with a higher mutation frequency of TP53, increased tumor mutation burden (TMB), a higher Ki67 index, and elevated homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) scores [15]. These tumors also show enrichment in gene sets related to DNA damage repair, cell cycle regulation, and inflammatory responses [15]. In melanoma, a high tumor fusion burden is strongly associated with chromosomal instability (β = 0.72, P < 0.01), heightened proliferation, and diminished immune cytolytic activity, suggesting a phenotype conducive to immune evasion [17].

Table 1: Prognostic Value of Gene Fusions in Different Cancers

| Cancer Type | Key Fusion Gene(s) | Prognostic Association |

|---|---|---|

| HR+/HER2– Breast Cancer | Various (e.g., KAT6B::ADK) | Shorter OS, RFS, and DMFS [15] |

| Advanced Melanoma | High Tumor Fusion Burden (TFB-H) | Poor response to ICB, reduced OS, increased mortality risk (HR=2) [17] |

| Colorectal Cancer | KANSL1-ARL17A/B | Detected with high frequency (69%) [16] |

Fusion Genes as Therapeutic Targets

Oncogenic fusion genes, particularly those involving kinases, represent a class of "druggable" targets, leading to the development of highly effective, targeted therapies.

Established Targeted Therapies

The paradigm of targeting fusion genes in cancer therapy is well-established. Fusion-driven cancers often exhibit oncogene addiction, making them particularly vulnerable to targeted inhibition. Notable examples include:

- EML4::ALK fusions in ~4% of lung cancers, targeted by ALK inhibitors (crizotinib, brigatinib, lorlatinib, alectinib) [15] [16].

- NTRK fusions in up to ~1% of solid tumors, targeted by larotrectinib and entrectinib, which are approved for pancancer, tissue-agnostic use [15].

- FGFR2 fusions in cholangiocarcinoma, targeted by infigratinib and pemigatinib [16].

- RET fusions, targeted by selpercatinib and pralsetinib in solid tumors [16].

Emerging Therapeutic Targets

Research continues to uncover new targetable fusions. In melanoma, fusions such as KIAA1549::BRAF represent therapeutic opportunities, potentially with novel type II RAF inhibitors [17]. A groundbreaking study in HR+/HER2– breast cancer identified ADK fusion genes as novel and recurrent drivers. The most common, KAT6B::ADK, was found to enhance metastatic potential and confer tamoxifen resistance [15]. Mechanistically, KAT6B::ADK activates ADK kinase activity through liquid–liquid phase separation, triggering the integrated stress response pathway [15]. Crucially, patient-derived organoids (PDOs) harboring KAT6B::ADK demonstrated increased sensitivity to ADK inhibitors, establishing ADK fusions as a compelling new therapeutic target [15].

Table 2: Selected Therapeutically Actionable Gene Fusions and Targeted Drugs

| Fusion Gene | Cancer Type | Targeted Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| EML4::ALK | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | Crizotinib, Alectinib, Lorlatinib [16] |

| NTRK | Various Solid Tumors (Pancancer) | Larotrectinib, Entrectinib [15] [16] |

| FGFR2 | Cholangiocarcinoma | Infigratinib, Pemigatinib [16] |

| RET | Various Solid Tumors | Selpercatinib, Pralsetinib [16] |

| KIAA1549::BRAF | Melanoma | Type II RAF inhibitors (in research) [17] |

| KAT6B::ADK (ADK fusions) | HR+/HER2– Breast Cancer | ADK inhibitors (in research) [15] |

Detection Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Accurate detection of fusion genes is paramount for their clinical application. RNA sequencing (RNAseq) has emerged as a powerful tool for this purpose, capable of revealing gene fusions, splicing variants, and mutations in a single test [8].

Bulk RNA Sequencing for Fusion Detection

Bulk RNAseq provides an average global gene expression profile from a tissue or cell population and is the most widely used technology for fusion discovery [8]. It can be tailored for different purposes: single-end short sequencing is cost-effective for differential gene expression, while paired-end longer sequencing on rRNA-depleted libraries offers more comprehensive information on alternative splicing, novel transcripts, and gene fusions [8].

Standard Bulk RNAseq Wet-Lab Protocol

The following is a generalized protocol for bulk RNA sequencing, adapted from experimental methods [18] [16]:

- Sample Collection and Preservation: Tissue samples are collected and either freshly frozen in RNA stabilizing solution (e.g., RNAlater) or formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE). For FFPE samples, a standardized formalin fixation time (e.g., 16 hours) is recommended [16].

- RNA Extraction: Total RNA is extracted from tissue slices using a commercial kit (e.g., QIAGEN RNeasy Kit), following the manufacturer's protocol [16].

- Library Preparation: Libraries are constructed using a kit such as the KAPA RNA Hyper with rRNA Erase kit for ribosomal RNA depletion. Samples are multiplexed using different adaptors [16].

- Quality Control: Library concentration is measured (e.g., using Qubit dsDNA HS Assay kit), and quality is assessed (e.g., with Agilent Tapestation) [16].

- Sequencing: Sequencing is performed on a platform such as the Illumina NovaSeq6000 for paired-end sequencing, typically with a read length of 75bp or 100bp, aiming for at least 15 million reads per sample [18] [16].

Computational Analysis Protocol

The bioinformatic detection of fusions from bulk RNAseq data involves a multi-step process [19]:

- Read Mapping and Gene Quantification: Raw sequencing reads (FASTQ files) are processed using a aligner like STAR with a reference transcriptome (e.g., GRCh38) and transcript annotation (e.g., Gencode) [19] [16].

- Fusion Calling: Fusion transcripts are detected using specialized software such as STAR-Fusion [16]. Identified candidates are typically filtered based on supporting evidence, requiring, for example, either a

JunctionReadCount > 1or aSpanningFragCount > 1[16]. - Differential Expression Analysis: Read counts are used for differential gene expression analysis between experimental groups using tools like DESeq2, with an adjusted p-value < 0.05 and a log2fold change considered significant [18].

Advancing Detection: Newer Sequencing Technologies and Algorithms

While bulk RNAseq is powerful, it has limitations, including an inability to resolve cellular heterogeneity. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq), such as the 10X Genomics Chromium system, can dissect intra-tumor heterogeneity and identify rare cell populations expressing drug-resistant fusion variants [8]. Furthermore, long-read isoform sequencing (e.g., PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) enables the detection of fusion transcripts at unprecedented resolution in both bulk and single-cell samples [20]. Tools like CTAT-LR-Fusion have been developed to leverage long-read data, maximizing the detection of fusion splicing isoforms and fusion-expressing tumor cells [20].

To address speed and sensitivity in clinical settings, new computational algorithms are being created. Fuzzion2, a gene fusion pattern-matching program, uses fuzzy pattern matching to analyze unmapped RNA-seq samples in minutes with high accuracy, facilitating rapid clinical turnaround [21].

FFPE vs. Fresh Frozen Samples

A critical consideration in clinical diagnostics is the use of FFPE tissues, where RNA is heavily degraded. A landmark study comparing matched FFPE and freshly frozen (FF) colorectal cancer samples found no statistically significant difference in the number of chimeric transcripts detected by RNAseq, validating the use of widely available FFPE archives for fusion detection [16].

Diagram 1: Clinical significance of gene fusions, illustrating their dual role as biomarkers and targets leading to improved patient outcomes through informed treatment selection.

Successful fusion gene research relies on a suite of wet-lab and computational tools.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Fusion Gene Analysis

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Example Products / Tools |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization Reagent | Preserves RNA integrity in fresh tissues prior to extraction. | RNAlater (Ambion) [16] |

| RNA Extraction Kit | Isolves high-quality total RNA from tissues (FFPE or fresh). | QIAGEN RNeasy Kit [16] |

| RNAseq Library Prep Kit | Constructs sequencing libraries; often includes rRNA depletion. | KAPA RNA Hyper with rRNA Erase kit [16] |

| Sequencing Platform | Generates high-throughput RNA sequencing data. | Illumina NovaSeq6000 [18] |

| Alignment & Fusion Caller | Maps RNAseq reads and identifies chimeric fusion transcripts. | STAR aligner, STAR-Fusion [16] |

| Differential Expression Tool | Statistically analyzes gene expression changes. | DESeq2 R package [18] [19] |

| Long-Read Fusion Caller | Detects fusion transcripts from long-read sequencing data. | CTAT-LR-Fusion [20] |

| Rapid Pattern-Matching Tool | Expedited fusion detection for clinical turnaround. | Fuzzion2 [21] |

Diagram 2: Multi-Omics Profiling Workflow, showing the integrated genomic, transcriptomic, and functional pipeline from sample to clinical or research application.

Market Perspective and Future Directions

The critical role of gene fusions in oncology is reflected in the growing diagnostic and therapeutic markets.

The global gene fusion testing market was valued at US$ 0.7 billion in 2024 and is projected to grow at a CAGR of 12.1% to reach US$ 2.5 billion by 2035 [22]. This growth is driven by the increasing incidence of cancer and rising demand for personalized medicine. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is the dominant technology segment, holding a 42.1% market share in 2024 due to its ability to perform comprehensive genomic profiling [22].

Concurrently, the market for fusion-targeted therapies is also expanding. The NRG1 fusion-targeted therapy market, for instance, is projected to grow from USD 133.1 million in 2025 to approximately USD 242.9 million by 2035, at a CAGR of 6.2% [23]. This underscores the transition of fusion genes from research discoveries to integral components of clinical oncology, guiding the use of targeted treatments in specific patient populations.

Future directions will likely involve the broader integration of multi-omics profiling (genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic) to fully characterize the functional impact of fusions [15], the increased use of single-cell and spatial RNA sequencing to understand fusion heterogeneity within the tumor microenvironment [8], and the continuous development of more potent and selective inhibitors against fusion-driven cancers.

The detection of fusion genes is a critical component of precision oncology, as many represent actionable therapeutic targets or valuable diagnostic biomarkers [16]. Bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has emerged as a powerful tool for this purpose, capable of revealing gene fusions, splicing variants, and mutations within a single test [8]. However, the utility of bulk RNA-seq is constrained by two fundamental limitations: the obscuring nature of cellular heterogeneity and the technical challenges affecting detection sensitivity. This application note details these challenges and provides structured experimental protocols to enhance the reliability of fusion gene detection in research and drug development.

Key Challenges in Bulk RNA-Seq for Fusion Detection

The Problem of Cellular Heterogeneity

Bulk RNA-seq utilizes a tissue or cell population as starting material, resulting in an averaged gene expression profile from the entire sample [8]. This averaging effect presents a significant challenge in fusion detection.

Table 1: Impact of Cellular Heterogeneity on Fusion Detection

| Challenge | Consequence for Fusion Detection | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Averaged Expression Profile | Signals from rare cell populations (e.g., a small subclone harboring a fusion) are diluted, potentially falling below the detection threshold [8]. | Complement with single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) on selected samples [24]. |

| Obscured Cell-Type Specificity | Difficulty in determining whether a fusion is present in all tumor cells or a specific subtype, complicating biological interpretation [12]. | Computational deconvolution using single-cell reference maps [12]. |

| Stromal Contamination | High levels of RNA from non-tumor cells (e.g., immune or stromal cells) can mask fusion transcripts originating from tumor cells [8]. | Enrich for target cell populations (e.g., via flow sorting) prior to RNA extraction. |

The primary issue is that bulk RNA-seq provides a population-level average, meaning a fusion transcript expressed in a rare subpopulation of cells may be diluted by the RNA from non-expressing cells, rendering it undetectable [8]. This is particularly problematic for detecting fusions in minor subclones that may be responsible for therapeutic resistance.

Limitations in Detection Sensitivity

Sensitivity in bulk RNA-seq is influenced by multiple experimental and computational factors, from sample quality to data analysis.

Table 2: Factors Affecting Detection Sensitivity and Specificity

| Factor | Impact on Sensitivity/Specificity | Quantitative Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Quality (FFPE vs. Fresh Frozen) | FFPE RNA is heavily degraded, theoretically reducing sensitivity. However, one study found no statistically significant difference in the number of chimeric transcripts detected between matched FFPE and Fresh Frozen samples [16]. | Read length of 75 bp can be sufficient for fusion detection in FFPE samples [16]. |

| Sequencing Depth | Low sequencing depth may not provide sufficient coverage to detect rare fusion transcripts. | In one study, an average of 15 million raw reads per sample was used for successful fusion detection [16]. |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Different fusion detection tools show a "degree of discrepancy," and false positives are a known challenge [16]. | Tools like DEEPEST can minimize false positives and improve sensitivity [8]. Use tools like STAR-Fusion with thresholds (e.g., JunctionReadCount >1) [16]. |

A major concern has been the use of Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) samples, where RNA is heavily degraded. However, recent research indicates that with modern protocols, fusion detection from FFPE RNA can be as effective as from freshly frozen tissue, a critical finding for leveraging vast clinical archives [16].

Experimental Protocols for Robust Fusion Detection

Protocol: RNA-Seq from Matched FFPE and Fresh Frozen Tissues

This protocol is adapted from a study that successfully detected fusions in colorectal cancer samples without significant performance loss in FFPE material [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

| Reagent / Tool | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| RNAlater Stabilizing Solution | Preserves RNA integrity in fresh tissues immediately after surgery. |

| QIAGEN RNeasy Kit | For extraction of total RNA from both FFPE slices and stabilized fresh tissue. |

| KAPA RNA Hyper with rRNA Erase Kit | For library construction and ribosomal RNA depletion (essential for FFPE RNA). |

| STAR-Fusion Software | A key bioinformatic tool for identifying chimeric transcripts from RNA-seq data. |

| ChimerDB Database | A curated database for classifying detected fusions as novel or known. |

Workflow Diagram

Methodology:

- Sample Collection: For each patient, split tumor tissue post-surgery. Place one portion in RNAlater solution and store at -70°C (Fresh Frozen, FF). Fix the other portion in formalin for a standardized duration (e.g., 16 hours) and embed in paraffin (FFPE) [16].

- RNA Extraction: Extract total RNA from both FFPE slices and stabilized fresh tissue using the QIAGEN RNeasy Kit or equivalent, following the manufacturer's protocol.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Perform library construction and ribosomal RNA depletion using the KAPA RNA Hyper with rRNA Erase kit. Multiplex libraries and sequence on a platform such as an Illumina system for paired-end reads (e.g., 75 bp length) [16].

- Computational Fusion Detection: Process FASTQ files with a dedicated fusion detection tool like STAR-Fusion [16]. Apply a minimum threshold (e.g., JunctionReadCount > 1 or SpanningFragCount > 1) to filter results.

- Fusion Annotation and Validation: Classify fusions as known or novel by querying databases like ChimerDB and the Mitelman Database. Potentially clinically actionable fusions, such as those involving kinase genes, should be prioritized for experimental validation (e.g., by RT-PCR or Sanger sequencing) [16].

Protocol: A Computational Approach to Enhance Biomarker Discovery

Intra-tumor heterogeneity can lead to poor reproducibility of RNA-seq-based biomarkers. This protocol outlines a computational strategy to select more robust prognostic gene signatures.

Workflow Diagram

Methodology:

- Data Analysis: Analyze multiple bulk RNA-seq datasets from patient cohorts (e.g., lung cancer). For each gene, assess its expression homogeneity within individual tumors, independent of high inter-tumor variability [8].

- Signature Selection: Prioritize genes that demonstrate homogeneous expression within tumors for building a prognostic signature. Research indicates that such genes often "encode expression modules of cancer cell proliferation and are often driven by DNA copy-number gains" [8].

- Validation: Test the resulting gene signature in independent patient cohorts. Signatures built on homogeneously expressed genes have been shown to minimize sampling bias and offer more robust prognostic performance [8].

Concluding Remarks

While bulk RNA-seq remains a powerful and cost-effective tool for fusion gene discovery, its limitations regarding cellular heterogeneity and detection sensitivity must be actively managed. The experimental protocols detailed herein provide a framework to enhance the rigor and reproducibility of fusion detection. By implementing careful sample processing, leveraging modern computational tools, and adopting robust biomarker selection strategies, researchers can more reliably uncover therapeutically actionable genomic events, thereby accelerating oncology research and drug development.

Implementing a Robust Bulk RNA-seq Fusion Detection Pipeline

Within the field of cancer genomics, the detection of fusion genes via bulk RNA sequencing (bRNA-seq) has become indispensable for diagnosis, subtyping, and targeted therapeutic interventions [14]. The reliability of such analyses, however, is profoundly dependent on a rigorously designed experiment. Choices made during the experimental design phase—specifically regarding biological replicates, sequencing depth, and read length—directly determine the sensitivity, specificity, and overall statistical power of a study. A poorly designed experiment can lead to false negatives, failing to detect critical driver fusions, or false positives, misdirecting research and clinical decisions. This Application Note details the critical steps in designing a robust bRNA-seq experiment for fusion gene detection, providing structured protocols and data standards to guide researchers and drug development professionals.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of a bRNA-seq experiment for fusion detection requires a suite of specific reagents and analytical tools. The following table catalogues the essential components.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Fusion Detection bRNA-seq

| Item Name | Function/Description | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(A) Selection or rRNA Depletion Kits | Enrichment for messenger RNA (mRNA) from total RNA. | Poly(A) selection is standard for most whole-transcriptome applications. rRNA depletion is necessary for degraded RNA or when including non-polyadenylated transcripts [25]. |

| Stranded RNA Library Prep Kit | Creates a sequencing library that preserves the original strand orientation of the transcript. | Crucial for accurately determining the orientation of fusion partners, which is essential for validating the fusion transcript structure [26]. |

| ERCC RNA Spike-In Controls | Exogenous RNA controls mixed with the sample RNA in known concentrations. | Allows for monitoring of technical performance and can aid in the quantification of absolute transcript abundance [25]. |

| Anchored-Fusion Software | A computational tool designed for highly sensitive fusion gene detection. | Particularly useful for detecting fusions involving genes with high sequence homology or in data with low sequencing depth by anchoring on a gene of interest [14]. |

| STAR Aligner | A splice-aware aligner for mapping RNA-seq reads to the reference genome. | The standard aligner in many processing pipelines, including the ENCODE Uniform Processing Pipeline for bRNA-seq [25] [26]. |

| Salmon | A tool for transcript quantification using pseudoalignment. | Provides fast and accurate quantification of transcript abundance, which can be integrated with alignment-based workflows for improved count matrices [26]. |

Core Experimental Parameters: Protocols and Data Standards

Biological Replicates and Statistical Power

Detailed Protocol:

- Experimental Design: For a standard case-control experiment, a minimum of three biological replicates per condition is considered the baseline. Biological replicates are defined as RNA samples extracted from different specimens or cultures (e.g., tumors from different patients or different primary cell cultures) representing the same biological condition [25].

- Sample Randomization: Process replicates in a randomized order across different library preparation batches and sequencing lanes to avoid confounding technical batch effects with biological effects.

- Quality Control Metric: Following data processing, calculate the Spearman correlation of gene-level quantification (e.g., FPKM or TPM) between all pairs of replicates. The ENCODE consortium standards require a Spearman correlation of >0.9 between isogenic replicates to demonstrate high replicate concordance [25].

Justification: Biological replicates account for the natural variation within a population. Without an adequate number of replicates, statistical tests for differential expression of the fusion gene or its downstream targets will be underpowered, leading to unreliable conclusions. The high correlation threshold ensures that the observed gene expression profiles are consistent and reproducible.

Sequencing Depth (Read Depth)

Sequencing depth, or the number of reads per sample, is a primary determinant for the sensitivity of fusion detection, as it affects the ability to capture low-abundance transcripts.

Detailed Protocol:

- Define Project Aims: The required read depth is directly tied to the goals of the study. Refer to Table 2 for specific recommendations.

- Calculate Total Reads: Determine the total number of reads needed by multiplying the reads per sample by the total number of samples. For example, 30 samples sequenced at 40 million reads each requires a total of 1.2 billion reads.

- Sequencing Lane Allocation: Divide the total reads required by the output of your chosen sequencing flow cell (e.g., an Illumina NovaSeq S4 flow cell produces ~4-5 billion reads) to determine how many lanes to allocate for your project [27].

Table 2: Recommended Sequencing Depth for bRNA-seq Applications

| Experimental Goal | Recommended Reads per Sample | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Targeted Fusion Panel | ~3 million reads | Panels like the TruSight RNA Pan Cancer are highly multiplexed and target specific genes, requiring far fewer reads [27]. |

| Gene Expression Profiling | 5 - 25 million reads | Sufficient for a snapshot of highly expressed genes but may miss low-expression transcripts and fusions [27]. |

| Standard Whole-Transcriptome (incl. Fusion Detection) | 30 - 60 million reads | The typical range for most published bRNA-seq studies. Provides a global view of gene expression and allows for the detection of medium- to high-abundance fusion transcripts [27]. |

| In-depth Fusion Discovery & Transcript Assembly | 100 - 200 million reads | Necessary for comprehensive detection of low-abundance fusions, novel transcript discovery, and accurate alternative splicing analysis [27]. |

| ENCODE Project Standard | Minimum 30 million aligned reads | The updated ENCODE standard for bulk RNA-seq of long RNAs to ensure robust gene quantification [25]. |

Read Length

Detailed Protocol:

- Library Type Determination: For fusion detection and general transcriptome analysis, paired-end (PE) sequencing is mandatory. Single-end data is not recommended for differential expression or fusion analysis, as paired-end reads provide information from both ends of a fragment, greatly improving mapping accuracy and the ability to identify splice junctions [26].

- Read Length Selection:

- For gene expression quantification, shorter paired-end reads (e.g., PE 50 bp or PE 75 bp) are often sufficient to minimize reading across multiple splice junctions while counting all RNAs [27].

- For novel transcriptome assembly, annotation, and robust fusion detection where precise breakpoint identification is key, longer paired-end reads (e.g., 2x100 bp or 2x150 bp) are beneficial. They enable more complete coverage of transcripts and better identification of novel variants and splice sites [27] [28].

Justification: Longer reads are more likely to span the unique sequences on either side of a fusion breakpoint, providing direct evidence of the fusion event and simplifying computational detection compared to shorter reads, which may require complex and error-prone assembly to reconstruct the fusion transcript [28].

Integrated Experimental Workflow

The following diagram synthesizes the critical steps and decision points in designing a bRNA-seq experiment for fusion gene detection, from sample preparation to data analysis.

The rigorous detection of fusion genes in bulk RNA-seq data is a cornerstone of modern cancer research and drug development. This protocol has outlined the non-negotiable pillars of a robust experimental design: sufficient biological replicates to ensure statistical power, adequate sequencing depth to capture the dynamic range of transcript expression—particularly for low-abundance fusion events—and the use of paired-end reads of appropriate length to accurately resolve transcript structures. By adhering to these established standards and leveraging specialized tools like Anchored-fusion, researchers can generate high-quality, reliable data capable of uncovering novel oncogenic drivers and informing critical therapeutic decisions.

RNA Extraction and Quality Control for Optimal Library Preparation

The reliable detection of fusion genes—hybrid genes formed from chromosomal rearrangements—is critical for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic decision-making [28] [29]. In bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) research, the success of fusion detection assays is profoundly dependent on the quality and integrity of the input RNA [30]. Suboptimal RNA quality can lead to false negatives, particularly for lowly expressed or novel fusion transcripts, thereby compromising research conclusions and potential clinical applications [28]. This application note details standardized protocols for RNA extraction and quality control, specifically tailored to support robust fusion gene detection within a bulk RNA-Seq research framework.

RNA Quality Thresholds for Successful Fusion Detection

The performance of whole transcriptome sequencing (WTS) assays for fusion gene detection is intrinsically linked to RNA quality. Establishing and adhering to strict quality thresholds is essential for ensuring assay sensitivity and specificity.

Table 1: Quality Control Thresholds for Fusion Gene Detection Assays

| Quality Metric | Minimum Threshold | Optimal Performance Range | Measurement Instrument |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Degradation (DV200) | ≥ 30% [30] | ≥ 50% [30] | Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer |

| RNA Input (FFPE) | 100 ng [30] | 10-200 ng [31] | Qubit Fluorometer |

| Fusion Transcript Input | 40 copies/ng [30] | >40 copies/ng [30] | - |

| Mapped Reads | 80 Million reads [30] | ~25 Gigabases data [30] | Sequencing Output |

| RNA Integrity Number (RIN) | Not specified for FFPE | Assessed via DV200 [31] | Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer |

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples, a common source for oncology research, present specific challenges due to RNA degradation. Studies validating WTS assays for fusions have defined a DV200 value of ≥ 30% as the threshold for acceptable RNA degradation [30]. For samples with DV200 ≥ 50%, the fragmentation step during library preparation can be skipped, leading to improved outcomes [30]. The input requirements and sequencing depth are also critical; for example, one validated assay requires a minimum of 80 million mapped reads to achieve a sensitivity of 98.4% for known fusions [30].

RNA Extraction and QC Experimental Protocol

RNA Extraction from FFPE Samples

The following protocol is adapted from methods used in validated fusion detection studies [31] [30].

Materials:

- Tissue Material: 10 sections of a 5 x 5 mm² FFPE tissue block with tumor content exceeding 20% [30].

- Extraction Kit: RNeasy FFPE Kit (Qiagen) or AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit (Qiagen) [31] [30].

- Equipment: Microtome, water bath, centrifuge, vortex mixer, NanoDrop 8000, Qubit Fluorometer, and Agilent TapeStation 4200 or Bioanalyzer [31].

Procedure:

- Sectioning: Cut 10 serial sections of 5-10 µm thickness from the FFPE block using a microtome.

- Deparaffinization:

- Add 1 mL of xylene (or a suitable xylene substitute) to the samples and vortex vigorously.

- Centrifuge at full speed for 5 minutes. Carefully remove the supernatant without disturbing the pellet.

- Repeat the xylene wash step once.

- Ethanol Wash:

- Wash the pellet twice with 1 mL of 100% ethanol, vortexing and centrifuging each time. Ensure the pellet is fully dislodged during washing.

- After the final wash, air-dry the pellet briefly (5-10 minutes) to ensure all ethanol has evaporated.

- RNA Extraction:

- Follow the manufacturer's instructions for the RNeasy FFPE Kit. This typically involves:

- Digesting the tissue with proteinase K to reverse formalin cross-links.

- Binding RNA to a silica membrane column.

- Washing with appropriate buffers.

- Eluting RNA in nuclease-free water.

- Follow the manufacturer's instructions for the RNeasy FFPE Kit. This typically involves:

- Storage: Store purified RNA at -80°C if not used immediately.

RNA Quality Control Assessment

A multi-perspective QC strategy is recommended, assessing RNA at the sample, raw read, and alignment levels [32].

Procedure:

- Quantification and Purity:

- Integrity and Size Distribution:

- Pre-sequencing Library QC: After library preparation, assess the library's concentration, average fragment size, and profile using the Qubit and LabChip GX Touch or similar systems [31] [30].

Diagram Title: RNA Extraction and QC Workflow for Fusion Detection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following reagents and kits are fundamental for executing the RNA extraction and library preparation workflows required for sensitive fusion gene detection.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-Seq in Fusion Detection

| Item | Function/Application | Example Product/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kit (FFPE) | Purifies RNA from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues, reversing cross-links. | RNeasy FFPE Kit (Qiagen) [31] [30] |

| rRNA Depletion Kit | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA to enrich for mRNA and other RNA species, crucial for FFPE samples. | NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit (Human/Mouse/Rat) [30] |

| Stranded RNA Library Prep Kit | Prepares sequencing libraries that preserve strand orientation of transcripts, improving fusion breakpoint accuracy. | Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep [33], NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit [30] |

| RNA Integrity Assessment | Determines RNA quality (DV200, RIN) via electrophoretic separation; critical for sample QC. | Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer System [31] [30] |

| RNA Spike-in Controls | Adds synthetic RNA transcripts to monitor technical variability and quantification accuracy. | ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix [29] |

| Targeted Enrichment Panels | Biotinylated probes to enrich for genes involved in fusions, increasing detection sensitivity. | SureSelect XTHS2 RNA Kit [31] |

The rigorous application of the RNA extraction and quality control protocols outlined in this document forms the foundation for successful fusion gene detection in bulk RNA-Seq research. By adhering to the defined quality thresholds—particularly the DV200 metric for FFPE samples—and utilizing the appropriate toolkit, researchers can significantly enhance the sensitivity and reliability of their assays, thereby ensuring the generation of robust and actionable data for cancer research and drug development.

Within the field of cancer genomics, the detection of fusion genes from bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data has become an indispensable component of both research and clinical diagnostics. Gene fusions, hybrid genes formed from the combination of two previously independent genes, are pivotal drivers in tumorigenesis and serve as critical diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets in numerous cancers [28]. The computational identification of these events from sequencing data presents significant challenges, necessitating robust, standardized workflows to ensure accuracy and reproducibility. This document outlines a comprehensive computational protocol for detecting gene fusions from bulk RNA-seq data, from initial quality control of raw sequencing reads to the final calling of high-confidence fusion events. The workflow is framed within the context of advancing fusion gene detection research, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed methodological guide that integrates current best practices and emerging computational tools.

The journey from raw sequencing data to a validated list of gene fusions involves multiple, interconnected computational stages. Each stage is designed to address specific challenges, such as data quality, alignment ambiguity, and the high false-positive rate inherent in fusion detection algorithms. The overarching goal is to maximize sensitivity for true positive fusions while rigorously filtering out technical artifacts. The principal stages of the workflow are (1) Raw Read Trimming and Quality Control, (2) Sequence Alignment and Expression Quantification, (3) Fusion Calling and Initial Filtering, and (4) Downstream Validation and Interpretation. Adherence to this structured workflow is essential for generating reliable, analytically valid results that can inform downstream biological insights and potential clinical applications. The following sections provide a detailed, step-by-step protocol for each stage, including specific software recommendations, parameters, and data handling procedures.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Raw Read Trimming and Quality Control

The initial processing of raw sequencing reads in FASTQ format is critical for the success of all subsequent analyses. This stage assesses data quality and removes technical sequences that could interfere with alignment.

- Procedure:

- Quality Assessment: Run FastQC on the raw FASTQ files to generate a comprehensive quality report for each sample. Key metrics to examine include per-base sequence quality, sequence duplication levels, adapter contamination, and overrepresented sequences [34].

- Adapter Trimming: Use Trimmomatic to remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases from the reads. A typical command for paired-end data is: This command removes Illumina adapters, trims low-quality bases from the start and end of reads, and discards reads shorter than 36 base pairs [34].

- Post-Trimming QC: Re-run FastQC on the trimmed FASTQ files to confirm that quality issues have been resolved.

- Aggregate Reports: Use MultiQC to aggregate FastQC and Trimmomatic reports from all samples into a single, unified HTML report, facilitating a cohort-level assessment of data quality [34].

Sequence Alignment and Expression Quantification

Following quality control, the trimmed reads are aligned to a reference genome, and gene expression is quantified. This step provides the aligned data necessary for fusion detection and can also be used for expression-based filtering of results.

- Procedure:

- Genome Alignment with STAR: Perform spliced alignment of the trimmed reads to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) using the STAR aligner. STAR is a splice-aware aligner that is widely used in RNA-seq pipelines and is effective for fusion detection [26] [35]. The two-pass alignment method is recommended for improved detection of novel junctions, which is crucial for finding fusion events [35].

- Expression Quantification with Salmon: For expression quantification, the pseudo-alignment tool Salmon is recommended for its speed and accuracy in handling transcript-level ambiguity [26]. Salmon can be run in alignment-based mode using the BAM file generated by STAR. The resulting transcript abundance estimates (TPM, counts) are vital for subsequent filtering of fusion candidates based on the expression levels of the partner genes [26].

Fusion Calling and Initial Filtering

This is the core analytical step where potential fusion events are identified from the aligned RNA-seq data. Given that no single tool is perfect, employing a consensus-based approach is highly advisable.

- Procedure:

- Multi-Tool Fusion Calling: Run at least two fusion detection algorithms on the STAR-aligned BAM files. Popular and effective tools include:

- JAFFAL: Identifies fusions from long-read data but has also been adapted for short-read; it is effective at finding known and novel fusions [28] [36].

- Arriba or STAR-Fusion: These are specialized, high-performance tools designed for fusion detection from STAR-aligned RNA-seq data.

- Anchored-fusion: A highly sensitive tool useful for targeted searches of specific driver genes, even in low-depth data [14].

- Generate Consensus Calls: Compare the outputs of the different fusion callers to create a high-confidence set of candidates. Fusions detected by multiple independent algorithms are more likely to be genuine.

- Apply Systematic Filtering: Implement a rigorous filtering strategy to remove common artifacts. Key filters include [28]:

- Read Support: Require a minimum number of supporting reads (e.g., ≥ 3 spanning or split reads).

- Gene Types: Exclude fusions involving non-relevant genes such as mitochondrial, ribosomal, HLA, or pseudogenes.

- Strand Consistency: Remove fusions with incompatible strand orientations for the partner genes.

- Recurrence: Flag or remove fusions that are recurrent across an unusually high percentage of samples in a cohort, as they may represent systematic artifacts.

- Expression Filtering: Filter out fusion candidates where the partner genes show very low expression, as these are less likely to be functional or real.

- Multi-Tool Fusion Calling: Run at least two fusion detection algorithms on the STAR-aligned BAM files. Popular and effective tools include:

Downstream Validation and Interpretation

The final stage involves validating the high-confidence fusion candidates and interpreting their potential biological and clinical significance.

- Procedure:

- Manual Inspection: Visualize the aligned reads supporting the fusion breakpoints using a tool like IGV (Integrative Genomics Viewer). This allows for manual verification of the split-read and spanning-read evidence.

- Experimental Validation: Where possible, confirm high-priority fusion events using an orthogonal method such as RT-PCR followed by Sanger sequencing or by using a targeted DNA- and RNA-based NGS panel [11].

- Functional Annotation: Annotate the validated fusions for their potential functional impact. This includes determining if the fusion is in-frame, assessing the retention of key functional protein domains, and cross-referencing with known fusion databases (e.g., Mitelman Database, ChimerDB) to determine if it is a known, recurrent event [36].

- Clinical Actionability: For clinically oriented studies, interpret the findings in the context of available targeted therapies. For example, fusions involving genes like ALK, ROS1, RET, and NTRK are often directly actionable [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Fusion Detection

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| STAR Aligner | Splice-aware aligner for mapping RNA-seq reads to a reference genome; its two-pass mode is crucial for sensitive novel junction discovery [26] [35]. |

| Salmon | Fast and accurate tool for transcript-level expression quantification from RNA-seq data; expression estimates are used to filter low-confidence fusion candidates [26]. |

| JAFFAL | Fusion detection tool effective for identifying both known and novel gene fusions; frequently used in benchmarking studies [28] [36]. |

| Anchored-fusion | A highly sensitive fusion detection tool that anchors a gene of interest, recovering non-unique matches often filtered out by other algorithms; ideal for targeted searches [14]. |

| GFvoter | A fusion caller for long-read data that uses a multivoting strategy with multiple aligners and tools to achieve high accuracy, demonstrating the power of consensus approaches [36]. |

| Trimmomatic | A flexible and efficient pre-processing tool for removing adapters and trimming low-quality bases from raw RNA-seq reads [34]. |

| FastQC & MultiQC | Tools for quality control; FastQC analyzes individual samples, and MultiQC aggregates results across all samples for a project-level view [34]. |

| Reference Standards | Commercially available DNA/RNA samples with validated fusions (e.g., from GeneWell) used to technically validate the entire workflow's accuracy and sensitivity [11]. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and dependencies between the key stages of the computational workflow.

Computational Workflow for Fusion Calling

Performance Benchmarks and Data Presentation

Evaluating the performance of different fusion detection tools is essential for selecting appropriate methods. The following table summarizes the precision and recall of several tools as benchmarked on real and simulated datasets.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Fusion Detection Tools on Real and Simulated Datasets (adapted from [36])

| Tool | Average Precision (%) | Average Recall (%) | Average F1 Score | Key Strength / Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFvoter | 58.6 | Varies by dataset | 0.569 | Superior precision-recall balance; uses multivoting strategy [36]. |

| LongGF | 39.5 | Varies by dataset | 0.407 | Effective for long-read sequencing data analysis [36]. |

| JAFFAL | 30.8 | Varies by dataset | 0.386 | Capable of finding known and novel fusions; used in combined workflows [28] [36]. |

| FusionSeeker | 35.6 | Varies by dataset | 0.291 | Identifies fusions and reconstructs transcript sequences [36]. |

Note: Performance metrics are highly dependent on the specific dataset, sequencing platform, and tumor type. The F1 score, the harmonic mean of precision and recall, provides a single metric for overall performance comparison. A consensus approach that integrates calls from multiple tools often outperforms any single tool.

Gene fusions are hybrid genes formed by the juxtaposition of two previously independent genes, typically resulting from genomic rearrangements such as chromosomal translocations, deletions, or inversions [37]. These chimeric transcripts play significant roles as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets in oncology, with approximately 16.5% of cancer cases harboring at least one driving RNA fusion event [38]. The detection of fusion genes has evolved substantially with the advent of next-generation sequencing technologies, particularly RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), which provides a sensitive and efficient approach for identifying novel fusion events [39].

The clinical importance of fusion detection is underscored by numerous examples where fusion genes drive oncogenesis. Well-characterized fusions include BCR-ABL1 in chronic myeloid leukemia, EML4-ALK in non-small cell lung cancer, and TMPRSS2-ERG in prostate cancer [40] [37]. These discoveries have immediate therapeutic implications, as many gene fusions can be targeted with specific drugs. For instance, patients with NTRK fusions can be treated effectively with larotrectinib, while ALK fusions respond to crizotinib, ceritinib, and alectinib [41] [11].

RNA-seq has emerged as the primary method for fusion detection due to several advantages over DNA-based approaches. By focusing on the transcribed portion of the genome, RNA-seq avoids the challenges associated with large intronic regions and provides direct evidence of functionally expressed fusion events [39] [42]. However, fusion detection from RNA-seq data presents computational challenges, including distinguishing true positive fusions from artifacts introduced during library preparation, sequencing, and alignment [43] [41].

Computational Approaches for Fusion Detection

Algorithm Classifications and Strategies

Fusion detection algorithms employ distinct strategies to identify chimeric transcripts from RNA-seq data. Based on their alignment approaches, these tools can be categorized into three main classes [43]:

- Whole paired-end approach: Tools such as deFuse and FusionHunter align full-length paired-end reads to a reference genome and use discordant alignments to generate putative fusion events, which are subsequently filtered using additional information.

- Paired-end + fragmentation approach: Tools including TopHat-fusion, ChimeraScan, and Bellerophontes first identify discordant alignments from full-length paired-end reads, then create a pseudo-reference containing putative fusion events. Unaligned reads are fragmented and realigned to this pseudo-reference to identify junction-spanning reads.

- Direct fragmentation approach: Methods like MapSplice, FusionMap, and FusionFinder fragment every read before alignment and identify fusion candidates by aligning these fragments directly to a genomic reference.

Table 1: Classification of Fusion Detection Algorithms by Alignment Strategy

| Alignment Approach | Representative Tools | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Paired-End | deFuse, FusionHunter | Uses discordant alignments of full-length paired-end reads; applies filtering to select candidates |

| Paired-End + Fragmentation | TopHat-fusion, ChimeraScan, Bellerophontes | Two-step process: identifies discordant alignments, then creates pseudo-reference for realigning unaligned reads |

| Direct Fragmentation | MapSplice, FusionMap, FusionFinder | Fragments all reads before alignment; aligns fragments to reference genome to find fusion candidates |

Critical Filtering Strategies