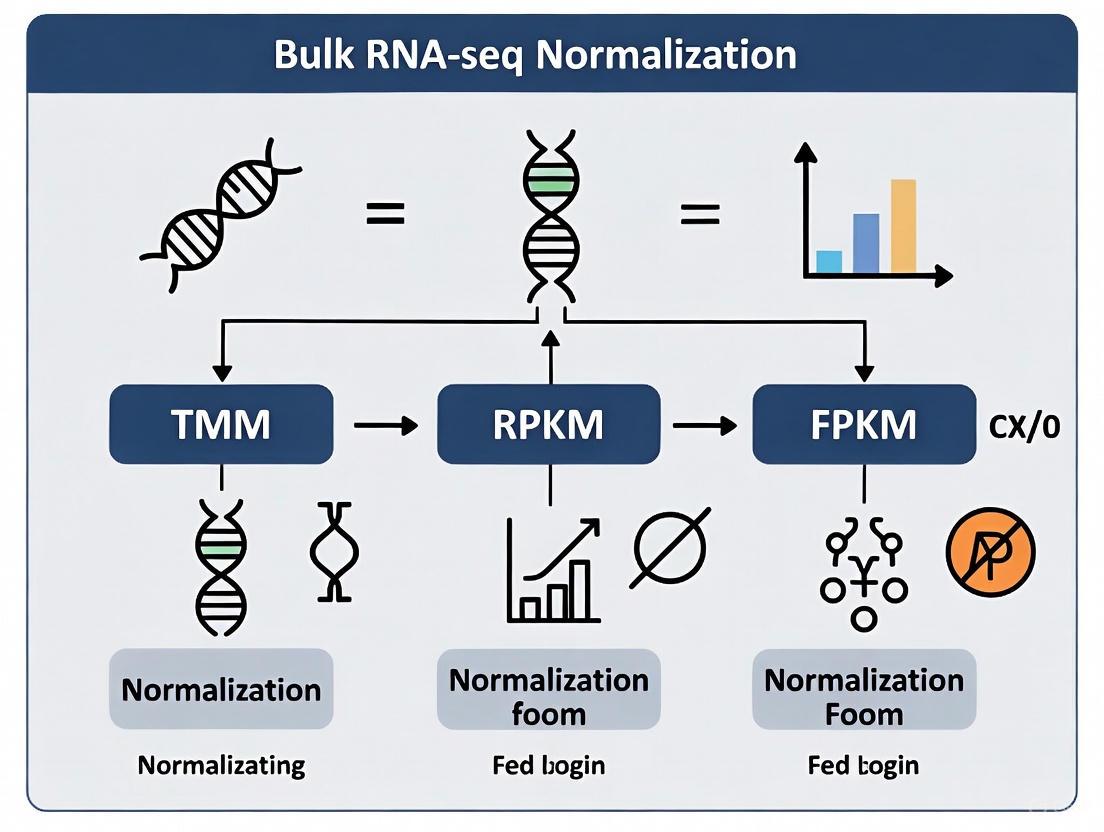

Bulk RNA-seq Normalization Methods Decoded: A Practical Guide to TMM, RPKM, FPKM, and Beyond for Reliable Gene Expression Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on navigating the critical step of normalization in bulk RNA-seq data analysis.

Bulk RNA-seq Normalization Methods Decoded: A Practical Guide to TMM, RPKM, FPKM, and Beyond for Reliable Gene Expression Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on navigating the critical step of normalization in bulk RNA-seq data analysis. We cover the foundational principles explaining why normalization is non-negotiable, detail the methodologies and calculations behind popular methods like TMM, RPKM, FPKM, TPM, and DESeq2, and offer troubleshooting for common pitfalls. By synthesizing recent benchmarking studies and validation protocols, this guide empowers scientists to select the optimal normalization strategy to ensure their downstream analyses, from differential expression to metabolic modeling, are biologically accurate and technically sound.

Why Normalize? Uncovering the Critical Sources of Technical Bias in RNA-seq Data

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become the cornerstone of modern transcriptomics, enabling genome-wide quantification of RNA abundance. However, the raw count data generated by sequencing platforms are not directly comparable due to multiple technical variables. Normalization is the critical mathematical adjustment of this raw data to account for technical biases, ensuring that observed differences reflect true biological variation rather than experimental artifacts. Without appropriate normalization, even well-designed studies risk generating misleading results, incorrect biological interpretations, and wasted resources. This application note details why normalization is indispensable and provides practical guidance for selecting and implementing appropriate normalization strategies in bulk RNA-seq analysis.

Why Normalization is Non-Negotiable: The Problem with Raw Counts

Raw RNA-seq counts are inherently biased by multiple technical factors that must be corrected before biological interpretation:

- Sequencing depth: Samples with more total reads will have higher counts, regardless of actual expression levels.

- Gene length: Longer genes accumulate more reads than shorter genes at identical expression levels.

- Library composition: Highly expressed genes in one sample can consume sequencing resources, skewing the representation of other genes.

- Technical variability: Batch effects, RNA quality, and library preparation protocols introduce non-biological variance.

The fundamental goal of normalization is to eliminate these technical confounders while preserving genuine biological signals, enabling accurate within-sample and between-sample comparisons [1] [2].

A Landscape of Normalization Methods

RNA-seq normalization methods can be categorized by their approach and application context. The table below summarizes the most common methods and their characteristics:

Table 1: Common RNA-Seq Normalization Methods and Their Applications

| Method | Category | Corrects For | Best Use Cases | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM (Counts Per Million) | Within-sample | Sequencing depth | Data visualization; not for DE | Does not correct for gene length or composition [2] |

| FPKM/RPKM | Within-sample | Sequencing depth + gene length | Gene expression within a single sample | Not ideal for cross-sample comparison due to variable totals between samples [3] [4] |

| TPM (Transcripts Per Million) | Within-sample | Sequencing depth + gene length | Within-sample comparison; some cross-sample applications | Sum of TPMs constant across samples; preferred over FPKM for proportion-based analysis [3] [2] |

| TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) | Between-sample | Sequencing depth + RNA composition | Differential expression analysis | Assumes most genes not differentially expressed; robust to skewed expression [5] [2] |

| RLE (Relative Log Expression) | Between-sample | Sequencing depth | Differential expression analysis | Used in DESeq2; similar assumptions to TMM [5] |

| Quantile | Between-sample | Distribution shape | Making distributions identical across samples | Assumes same expression distribution across samples; may remove biological signal in unbalanced data [6] [7] |

These methods are typically applied at different stages of analysis, from within-sample adjustments to cross-dataset integration:

Experimental Evidence: How Normalization Impacts Biological Interpretation

Case Study 1: Normalization Effects on Metabolic Model Reconstruction

A comprehensive 2024 benchmark study evaluated how normalization choices affect the reconstruction of condition-specific genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) using iMAT and INIT algorithms. The research compared five normalization methods (TPM, FPKM, TMM, GeTMM, and RLE) with Alzheimer's disease and lung adenocarcinoma datasets [5].

Table 2: Performance of Normalization Methods in Metabolic Model Reconstruction

| Normalization Method | Model Variability | Disease Gene Accuracy (AD) | Disease Gene Accuracy (LUAD) | Effect of Covariate Adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPM/FPKM (within-sample) | High variability in active reactions | Lower accuracy | Lower accuracy | Moderate improvement |

| RLE/TMM/GeTMM (between-sample) | Low variability in active reactions | ~0.80 accuracy | ~0.67 accuracy | Significant improvement |

| Key Finding: Between-sample methods reduced false positives at the expense of missing some true positives when mapping to GEMs. |

The study demonstrated that between-sample normalization methods (RLE, TMM, GeTMM) produced models with significantly lower variability and higher accuracy in capturing disease-associated genes compared to within-sample methods (TPM, FPKM). Furthermore, adjusting for covariates like age and gender improved accuracy across all methods [5].

Case Study 2: Reproducibility in Patient-Derived Xenograft Models

A 2021 study compared quantification measures using replicate samples from 20 patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models. The research evaluated which method minimized technical variation between replicates while preserving biological signals [4].

The findings revealed that normalized count data (using between-sample methods like TMM or RLE) outperformed TPM and FPKM in several key metrics:

- Superior clustering of replicate samples from the same PDX model

- Lowest median coefficient of variation across replicates

- Highest intraclass correlation coefficient values

This evidence demonstrates that methods designed for between-sample comparison provide more reliable results for differential expression analysis [4].

Decision Framework: Selecting the Right Normalization Strategy

Protocol: Choosing an Appropriate Normalization Method

Define your research question and comparison type

- For within-sample gene expression comparison (e.g., identifying the most highly expressed genes in a sample): Use TPM or FPKM

- For between-sample comparison (e.g., differential expression between conditions): Use between-sample methods (TMM, RLE)

Assess your dataset characteristics

- Check for global shifts in transcript distribution using PCA before normalization

- Evaluate whether basic assumptions of normalization methods are met:

- TMM/RLE: Most genes not differentially expressed

- Quantile: Similar expression distribution across samples

Address covariates and batch effects

- Identify known technical batches (sequencing date, library preparation)

- Consider biological covariates (age, sex, cell type composition)

- Apply covariate adjustment after initial normalization when needed [5]

Validate your normalization choice

- Examine reduction in technical variation between replicates

- Verify preservation of expected biological signals

- Assess whether results align with orthogonal validation methods (e.g., qPCR)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for RNA-Seq Normalization

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization Reagents (e.g., PAXgene) | Preserve RNA integrity during sample collection | Critical for maintaining RIN >7 for polyA-selection protocols [8] |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Remove abundant ribosomal RNA | Increases sequencing depth for non-rRNA targets; assess off-target effects on genes of interest [8] |

| Stranded Library Prep Kits | Preserve transcript orientation | Essential for identifying overlapping transcripts and accurate isoform quantification [8] |

| Spike-in Controls | Monitor technical variation | External RNA controls added before library prep for normalization quality assessment [7] |

| Quality Control Tools (FastQC, MultiQC) | Assess RNA and library quality | Identify adapter contamination, sequencing biases, and RNA degradation [1] |

Advanced Considerations and Future Directions

Normalization Challenges with Unbalanced Data

Traditional normalization methods assume symmetric distribution of differentially expressed genes and that most genes are not differentially expressed. These assumptions fail in specific biological contexts:

- Different tissues or developmental stages with varying total RNA content

- Cancer vs. normal cells with global shifts in transcription

- Small targeted arrays (e.g., miRNA panels) with limited invariant genes

For these unbalanced scenarios, specialized methods have been developed that use data-driven invariant gene sets or external controls as reference [7].

The Emerging Impact of Transcriptome Size Variation

Recent research has highlighted that transcriptome size—the total number of RNA molecules per cell—varies significantly across cell types and conditions. A 2025 study revealed that conventional single-cell RNA-seq normalization methods that force equal transcriptome sizes across cells can distort biological signals and impair deconvolution of bulk RNA-seq data [9]. While this study focused on single-cell applications, it underscores the importance of considering transcriptome size variations in bulk analyses, particularly when comparing tissues with fundamentally different RNA content.

Normalization is not merely a computational convenience but an essential prerequisite for biologically meaningful RNA-seq analysis. The choice of normalization method directly impacts which genes are identified as differentially expressed, how samples cluster in dimensional space, and ultimately what biological conclusions are drawn from the data. Between-sample normalization methods like TMM and RLE generally provide more robust performance for differential expression analysis, while within-sample methods like TPM are suitable for assessing relative transcript abundance within individual samples. As transcriptomic technologies evolve and applications diversify, understanding the principles and practical implications of normalization will remain fundamental to extracting accurate biological insights from RNA-seq data.

The fine detail provided by sequencing-based transcriptome surveys suggests that RNA-seq is likely to become the platform of choice for interrogating steady-state RNA. However, contrary to early expectations that RNA-seq would not require sophisticated normalization, the reality is that normalization continues to be an essential step in the analysis to discover biologically important changes in expression [10]. Technical variability in RNA-seq data arises from multiple sources throughout the experimental process, and this variability can substantially obscure biological signals if not properly addressed [11].

The fundamental challenge stems from the fact that RNA-seq is a digital sampling process that captures only a tiny fraction (approximately 0.0013%) of the available molecules in a typical library [12]. This low sampling fraction means that technical variability can lead to substantial disagreements between replicates, particularly for features with low coverage [12]. Furthermore, the counting efficiency of different transcripts varies due to sequence-specific biases, with GC-content having a particularly strong sample-specific effect on gene expression measurements [11].

This Application Note examines three primary sources of technical variability—sequencing depth, gene length, and RNA composition—and provides detailed protocols for normalization methods that address these challenges in the context of bulk RNA-seq experiments.

Sequencing Depth and Sampling Limitations

Sequencing depth refers to the number of reads generated per sample, which directly impacts the power to detect transcripts, especially those expressed at low levels. In practice, technical variability is too high to ignore, with exon detection between technical replicates being highly variable when coverage is less than 5 reads per nucleotide [12].

The relationship between sequencing depth and transcript recovery follows a pattern of diminishing returns. For de novo assembly, the amount of exonic sequence assembled typically plateaus using datasets of approximately 2 to 8 Gbp, while genomic sequence may continue to increase with additional sequencing, primarily due to the recovery of single-exon transcripts not documented in genome annotations [13].

Table 1: Impact of Sequencing Depth on Key Analysis Outcomes

| Sequencing Depth | Exon Detection Consistency | TCRαβ Reconstruction Success | Transcript Assembly Completeness |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 0.25 million PE reads | Highly variable | < 1% of cells | Limited to highly expressed genes |

| 0.25-1 million PE reads | Improved for moderate-high expression | >80% success rate | Recovery of most annotated exons |

| 1-5 million PE reads | Good for most exons | >95% success rate | Plateau of annotated exonic regions |

| >5 million PE reads | High consistency | ~100% success rate | Increasing single-exon, unannotated transcripts |

The sampling limitations of RNA-seq technology mean that even with millions of reads, we are surveying only a tiny fraction of the RNA molecules present in a sample. This sampling artifact can force differential expression analysis to be skewed toward one experimental condition if not properly adjusted [10].

Gene Length Bias

The number of reads mapping to a gene is not only dependent on its expression level but also on its transcript length. Longer genes generate more fragments than shorter genes with similar expression levels, creating a fundamental bias in raw count data [10] [14]. This bias prevents direct comparison of expression levels between genes within the same sample without appropriate normalization.

Gene length bias is particularly problematic when trying to identify changes in the expression of shorter transcripts, such as non-coding RNAs or specific isoforms, as the length effect can mask true biological differences. Normalization methods like RPKM, FPKM, and TPM were specifically designed to account for this bias by normalizing counts by transcript length [3] [14].

RNA Composition Effects

One of the most counterintuitive yet critical sources of technical variability arises from RNA composition differences between samples. The proportion of reads attributed to a given gene depends not only on that gene's expression level but also on the expression properties of the entire sample [10].

A hypothetical scenario illustrates this effect: if sample A contains twice as many expressed genes as sample B, but both are sequenced to the same depth, a gene expressed in both samples will have approximately half the number of reads in sample A because the reads are distributed across more genes [10]. This composition effect means that library size scaling alone is insufficient for normalization when comparing samples with different RNA repertoires.

In real biological contexts, composition effects occur when one condition has a set of highly expressed genes that "use up" sequencing capacity, thereby proportionally reducing the counts for all other genes in that sample. This can lead to false positives in differential expression analysis if not properly corrected [10].

Figure 1: Sources of Technical Variability in RNA-seq Experiments. Multiple technical factors introduce biases that can obscure biological signals if not properly addressed during normalization.

Normalization Methods: Theoretical Foundations

RPKM/FPKM and TPM

RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads) and its paired-end counterpart FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase per Million mapped fragments) were among the first normalization methods developed for RNA-seq data [3] [14]. These approaches normalize for both sequencing depth and gene length, allowing comparison of expression levels within a sample.

TPM (Transcripts Per Kilobase Million) represents an evolution of RPKM/FPKM with a different order of operations [3]. While RPKM/FPKM first normalizes for sequencing depth then gene length, TPM reverses this order: it first normalizes for gene length, then for sequencing depth. This seemingly minor difference has profound implications—TPM values sum to the same constant (1 million) across samples, making them directly comparable in terms of the proportion of transcripts each gene represents [3] [14].

Table 2: Comparison of RNA-seq Normalization Methods

| Normalization Method | Formula | Recommended Use | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| RPKM/FPKM | Reads/(Gene length × Total reads) × 10^9 | Within-sample gene comparisons | Not comparable across samples with different RNA composition |

| TPM | (Reads/Gene length) / Σ(Reads/Gene length) × 10^6 | Within- and between-sample comparisons | Still affected by RNA composition differences |

| TMM | Uses weighted trimmed mean of log expression ratios | Differential expression between samples | Assumes most genes are not differentially expressed |

The calculation of these metrics follows specific workflows:

Figure 2: RPKM/FPKM vs. TPM Calculation Workflows. Though mathematically similar, the different order of operations in TPM ensures that values sum to the same constant across samples, facilitating comparison.

TMM Normalization

The Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) method addresses a critical limitation of RPKM/FPKM and TPM: their susceptibility to RNA composition effects [10]. TMM operates on the assumption that most genes are not differentially expressed between samples, and uses this assumption to calculate scaling factors that account for composition biases.

The TMM algorithm selects a reference sample and calculates scaling factors for all other samples based on a weighted trimmed mean of the log expression ratios (M-values) [10] [15]. This approach robustly summarizes observed M values by trimming both the M values and the absolute expression levels (A values) before taking the weighted average, with precision weights accounting for the fact that log fold changes from genes with larger read counts have lower variance on the logarithm scale [10].

The resulting normalization factors can be incorporated into statistical models for differential expression analysis by adjusting the effective library sizes, thus accounting for the sampling properties of RNA-seq data [10].

Experimental Evidence of Technical Biases

Liver vs. Kidney Case Study

A publicly available dataset comparing technical replicates of liver and kidney RNA sources demonstrates the necessity of sophisticated normalization [10]. When standard normalization (accounting for total number of reads) was applied, the distribution of log ratios between liver and kidney samples was significantly offset toward higher expression in kidney, with housekeeping genes also showing a significant shift away from zero [10].

The explanation for this bias was straightforward: a prominent set of genes with higher expression in liver consumed substantial sequencing "real estate," leaving less capacity for sequencing the remaining genes in the liver sample. This proportionally distorted the expression values toward being kidney-specific [10]. Application of TMM normalization to this pair of samples corrected this composition bias, demonstrating the practical importance of appropriate normalization methods.

Protocol-Dependent Composition Effects

Different RNA extraction and library preparation protocols can dramatically alter the RNA repertoire that ultimately gets sequenced. A comparison of poly(A)+ selection and rRNA depletion protocols demonstrated strikingly different transcriptomic profiles from the same biological sample [16].

With poly(A)+ selection, the most abundant category was protein-coding genes, while rRNA depletion resulted in small RNAs being the most abundant category [16]. Consequently, TPM values from the different protocols were not directly comparable—in blood samples, the top three genes represented only 4.2% of transcripts in poly(A)+ selection but 75% of transcripts in rRNA depletion [16]. This massive shift in transcript distribution means that expression levels of many genes are artificially deflated in rRNA depletion samples relative to poly(A)+ selected samples.

Protocols for Effective Normalization

Best Practices for Differential Expression Analysis

A recommended workflow for bulk RNA-seq analysis involves multiple steps to ensure robust results:

Step 1: Read Alignment and Quantification Use a splice-aware aligner like STAR to align reads to the genome, facilitating generation of comprehensive QC metrics. Then use alignment-based quantification with tools like Salmon to handle uncertainty in read assignment and generate count matrices [17].

Step 2: Normalization Method Selection

- For differential expression analysis, incorporate TMM normalization within statistical frameworks like edgeR [15].

- For within-sample gene comparisons, use TPM values [14].

- Avoid using RPKM/FPKM for cross-sample comparisons, especially when RNA composition may differ [16].

Step 3: Accounting for Additional Biases Implement additional normalization steps to address sequence-specific biases like GC-content effects. Conditional quantile normalization has been shown to improve precision by 42% by removing systematic bias introduced by deterministic features such as GC-content [11].

Experimental Design Considerations

Sequencing Depth Guidelines Based on empirical studies, aim for at least 20-30 million reads per sample for standard differential expression analysis in bulk RNA-seq. For detection of low-abundance transcripts or complex applications like de novo assembly, 50-100 million reads may be necessary [13].

Replication Strategy Include both technical and biological replicates in experimental designs. Technical replicates help quantify and account for technical variability, while biological replicates are essential for drawing conclusions about biological conditions [12].

Protocol Consistency Maintain consistent library preparation protocols throughout an experiment. When comparing across datasets, be aware that different protocols (e.g., poly(A)+ selection vs. rRNA depletion) yield fundamentally different RNA repertoires that complicate direct comparison of normalized expression values [16].

Figure 3: RNA-seq Experimental Design and Analysis Workflow. Proper planning at each step minimizes technical variability and ensures biologically meaningful results.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for RNA-seq Normalization Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| STAR Aligner | Spliced alignment of RNA-seq reads to genome | Provides comprehensive QC metrics; enables subsequent alignment-based quantification [17] |

| Salmon | Alignment-based or pseudoalignment quantification | Handles read assignment uncertainty; generates count matrices for downstream analysis [17] |

| EdgeR | Differential expression analysis package | Implements TMM normalization within statistical framework for DE testing [15] |

| Trim Galore! | Adapter and quality trimming | Essential preprocessing step; removes technical sequences that interfere with alignment [13] |

| Poly(A) Selection Beads | mRNA enrichment protocol | Isolates mature mRNAs; creates specific RNA repertoire biased toward protein-coding genes [16] |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Removal of ribosomal RNA | Retains broader RNA classes including immature transcripts; alters TPM distribution [16] |

| Universal Human Reference RNA (UHRR) | Standard reference material | Enables assessment of technical variability and normalization accuracy across experiments [11] |

Technical variability in RNA-seq data arising from sequencing depth, gene length, and RNA composition effects presents significant challenges that must be addressed through appropriate normalization methods. While RPKM/FPKM and TPM provide solutions for within-sample comparisons and length biases, they remain susceptible to composition effects that can skew differential expression analysis between samples with different RNA repertoires.

The TMM normalization method offers a robust solution for composition biases by leveraging the assumption that most genes are not differentially expressed, while additional considerations like GC-content normalization can further improve precision. Researchers should select normalization approaches based on their specific experimental context and comparison goals, always mindful that even "normalized" values like TPM may not be directly comparable across different library preparation protocols.

By understanding these sources of technical variability and implementing appropriate normalization strategies, researchers can ensure that their RNA-seq analyses reveal true biological signals rather than technical artifacts.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become the most popular method for transcriptome profiling, replacing gene expression microarrays in many applications [4]. The analysis of RNA-seq data, however, presents unique challenges due to technical variations introduced during library preparation, sequencing, and data processing. Normalization serves as a critical computational procedure to remove these non-biological variations, ensuring that differences in gene expression measurements reflect true biological signals rather than technical artifacts [2].

The complexity of RNA-seq normalization necessitates a structured approach across multiple levels of analysis. This framework organizes normalization into three distinct stages: within-sample correction (accounting for gene length and sequencing depth), between-sample normalization (enabling comparative analysis across specimens), and cross-dataset harmonization (addressing batch effects when integrating multiple studies) [2]. Understanding this hierarchical structure is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working with transcriptomic data, as improper normalization can lead to false conclusions in downstream analyses such as differential expression testing and biomarker discovery [18].

Within the context of bulk RNA-seq analysis, this framework provides a systematic approach to selecting appropriate normalization methods—including TMM, RPKM, FPKM, and others—based on the specific analytical goals and experimental design. The following sections detail each stage, providing practical guidance for implementation and highlighting applications in pharmaceutical and clinical research settings.

The Three Stages of RNA-seq Normalization

Stage 1: Within-Sample Normalization

Within-sample normalization addresses technical factors that affect gene expression measurements within individual samples, primarily sequencing depth and gene length [2]. Sequencing depth refers to the total number of reads generated per sample, which varies between experiments due to technical rather than biological reasons. Gene length bias arises because longer transcripts typically yield more sequencing fragments than shorter transcripts at the same expression level [2]. Without correction, these factors prevent accurate comparison of expression levels between different genes within the same sample.

The most common within-sample normalization methods include:

- CPM (Counts Per Million): Normalizes for sequencing depth only by scaling raw counts by the total number of reads multiplied by one million [2]. Suitable for comparing expression of the same gene across samples but not for comparing different genes within a sample.

- RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase Million) and FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase Million): Adjust for both sequencing depth and gene length. RPKM is designed for single-end experiments, while FPKM is used for paired-end RNA-seq where two reads can correspond to a single fragment [4] [3] [2].

- TPM (Transcripts Per Million): Similar to RPKM/FPKM but employs a different order of operations—normalizing for gene length first, then sequencing depth [3]. This approach ensures that the sum of all TPM values in each sample is constant, facilitating comparison of the proportion of reads mapped to a gene across samples [3].

The calculation methods for these normalization approaches are as follows:

| Method | Formula | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| CPM | ( \text{CPM} = \frac{\text{Reads mapped to gene}}{\text{Total reads}} \times 10^6 ) | Sequencing depth normalization only |

| RPKM/FPKM | ( \text{RPKM/FPKM} = \frac{\text{Reads/Fragments mapped to gene}}{\text{Gene length (kb)} \times \text{Total reads (million)}} ) | Within-sample gene expression comparison |

| TPM | ( \text{TPM}i = \frac{\frac{ri}{li} \times 10^6}{\sumj \frac{rj}{lj}} ) where (ri): reads mapped to gene i, (li): length of gene i | Within-sample comparison with consistent sample sums |

Table 1: Within-sample normalization methods and their applications

While these within-sample normalized values are suitable for comparing gene expression within a single sample, they are insufficient for cross-sample comparisons due to additional technical variations between samples [2]. Specifically, RPKM and FPKM have been shown to introduce biases in cross-sample comparisons because the sum of normalized reads can differ between samples, making it difficult to determine if the same proportion of reads mapped to a gene across samples [3].

Stage 2: Between-Sample Normalization

Between-sample normalization enables meaningful comparisons of gene expression across different biological specimens by accounting for technical variability introduced during sample processing and sequencing. This stage is critical for downstream analyses such as differential expression testing, where the goal is to identify biologically relevant changes rather than technical artifacts [18].

The fundamental challenge in between-sample normalization stems from the compositionality of RNA-seq data—changes in the expression of a few highly expressed genes can create the false appearance of differential expression for other genes because the total number of reads is fixed [18]. Between-sample normalization methods address this by assuming that most genes are not differentially expressed or that the expression of certain control genes remains constant across conditions.

Figure 1: Between-sample normalization methods and their underlying assumptions

Key between-sample normalization methods include:

- TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values): Implemented in the edgeR package, TMM assumes most genes are not differentially expressed [2] [5]. It calculates scaling factors between samples by comparing each sample to a reference after trimming extreme log-fold changes and absolute expression levels [2].

- RLE (Relative Log Expression): Used by DESeq2, this method similarly assumes that most genes are non-DE and calculates size factors as the median of the ratios of each gene's count to its geometric mean across all samples [5].

- Quantile Normalization: Makes the distribution of gene expression values identical for each sample by replacing values with the average across samples for genes of the same rank [2].

Experimental evidence demonstrates that between-sample normalization methods like TMM and RLE outperform within-sample methods for cross-sample comparisons. A comparative study on patient-derived xenograft models revealed that normalized count data (using between-sample methods) showed lower median coefficient of variation and higher intraclass correlation values across replicate samples compared to TPM and FPKM [4]. Similarly, a benchmark study on metabolic network mapping showed that RLE, TMM, and GeTMM (a gene length-corrected version of TMM) produced more consistent results with lower variability compared to within-sample methods like TPM and FPKM [5].

Stage 3: Cross-Dataset Normalization

Cross-dataset normalization, often referred to as batch correction, addresses technical variations introduced when integrating RNA-seq data from multiple independent studies, sequencing platforms, or experimental batches. These batch effects can constitute the greatest source of variation in combined datasets, potentially masking true biological signals and leading to incorrect conclusions if not properly addressed [2].

The need for cross-dataset normalization has grown with the increasing practice of meta-analyses that combine data from public repositories to increase statistical power or validate findings across diverse populations. Batch effects arise from differences in sample preparation protocols, sequencing technologies, laboratory conditions, personnel, and reagent batches across experiments conducted at different times or facilities [2].

Figure 2: Cross-dataset normalization approaches for batch effect correction

Common cross-dataset normalization approaches include:

- Limma and ComBat: These methods remove batch effects when the sources of variation (e.g., sequencing date, facility) are known [2]. Both use empirical Bayes statistics to estimate prior probability distributions from the data, effectively "borrowing" information across genes in each batch to make robust adjustments even with small sample sizes.

- Surrogate Variable Analysis (SVA): Identifies and estimates unknown sources of variation using singular value decomposition or factor analysis after initially correcting for known batch effects [2].

- Training Distribution Matching (TDM): Specifically designed for cross-platform normalization, TDM transforms RNA-seq data to make it compatible with machine learning models trained on microarray data, enabling the creation of larger, more diverse training datasets [19].

A critical consideration in cross-dataset normalization is that between-sample normalization should typically be applied before batch correction to ensure gene expression values are on the same scale across samples [2]. Additionally, covariates such as age, gender, and post-mortem interval (for specific tissues) should be considered, as they can significantly impact results in disease studies [5].

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Protocol: Comparative Analysis of Normalization Methods

This protocol outlines a systematic approach for evaluating different normalization methods using replicate samples, based on experimental designs from published studies [4] [5].

Materials and Reagents

- RNA-seq datasets with biological replicates (minimum 3 replicates per condition)

- Computing environment with R/Bioconductor

- Normalization software: DESeq2 (for RLE), edgeR (for TMM), and standard tools for TPM/FPKM calculation

Procedure

- Data Acquisition: Obtain RNA-seq data from public repositories (e.g., NCI PDMR, TCGA) or generate new data. Ensure datasets include biological replicates for assessing technical variability.

- Quantification: Generate raw count data using alignment-based (e.g., STAR, HTSeq) or alignment-free (e.g., Salmon, kallisto) methods.

- Normalization Implementation:

- Apply within-sample methods (TPM, FPKM) using standard formulas

- Implement between-sample methods (TMM, RLE) using DESeq2 and edgeR packages

- Perform cross-dataset normalization using limma or ComBat when integrating multiple datasets

- Evaluation Metrics:

- Calculate coefficient of variation (CV) between replicates

- Compute intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for the same gene across replicates

- Perform hierarchical clustering to assess replicate concordance

- Evaluate false positive rates in differential expression analysis

Expected Results

Based on comparative studies, between-sample normalization methods (TMM, RLE) should demonstrate lower median CV and higher ICC values compared to within-sample methods (TPM, FPKM) [4]. Hierarchical clustering should group replicate samples from the same biological origin more accurately with between-sample normalization methods.

Protocol: Normalization for Metabolic Network Mapping

This specialized protocol describes RNA-seq normalization for constructing condition-specific genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), particularly relevant for drug development applications [5].

Materials and Reagents

- RNA-seq data from disease and control samples (e.g., Alzheimer's disease, cancer)

- Human metabolic network reconstruction (e.g., Recon3D)

- iMAT or INIT algorithm for metabolic model construction

- Covariate information (age, gender, clinical variables)

Procedure

- Data Preprocessing: Obtain RNA-seq counts for metabolic genes in the reconstruction model.

- Normalization Application:

- Apply five different normalization methods (TPM, FPKM, TMM, GeTMM, RLE) to the count data

- Generate covariate-adjusted versions using linear models

- Model Construction: Map normalized expression values to the metabolic network using iMAT or INIT algorithms to generate personalized metabolic models.

- Validation:

- Compare the number of active reactions in generated models

- Assess variability across samples for each normalization method

- Evaluate accuracy in capturing disease-associated genes using known biomarkers

Expected Results

Between-sample normalization methods (RLE, TMM, GeTMM) should produce metabolic models with lower variability in active reactions compared to within-sample methods (TPM, FPKM) [5]. Covariate adjustment should further improve accuracy, particularly for diseases with strong age or gender associations.

Successful implementation of RNA-seq normalization requires both computational tools and methodological knowledge. The following table summarizes key resources for researchers conducting normalization analyses.

| Resource Type | Specific Tools/Methods | Application Context | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Within-Sample Methods | TPM, FPKM, RPKM | Single-sample analysis, gene expression comparison within sample | TPM provides consistent sample sums; FPKM/RPKM suitable for single-sample comparisons only [3] [2] |

| Between-Sample Methods | TMM (edgeR), RLE (DESeq2), Quantile | Differential expression, cross-sample comparisons | Assume most genes not differentially expressed; robust to composition effects [18] [2] [5] |

| Cross-Dataset Methods | ComBat, limma, SVA, TDM | Data integration, meta-analysis, machine learning | Require prior between-sample normalization; TDM enables cross-platform compatibility [2] [19] |

| Experimental Design | Biological replicates, spike-in controls | All normalization stages | Replicates essential for evaluating normalization performance; spike-ins assess technical variability [4] [18] |

| Implementation Platforms | R/Bioconductor (DESeq2, edgeR, limma), Python | Practical application | DESeq2 and edgeR provide integrated normalization and DE analysis; limma extends to batch correction [2] [5] |

Table 2: Essential resources for implementing RNA-seq normalization across the three stages

The three-stage framework for RNA-seq normalization provides a systematic approach to addressing technical variations at different levels of analysis. Within-sample normalization enables accurate gene expression comparisons within individual specimens, between-sample methods facilitate robust cross-sample analyses, and cross-dataset normalization allows integration of diverse studies while minimizing batch effects.

Current evidence indicates that between-sample normalization methods like TMM and RLE generally outperform within-sample methods for comparative analyses, demonstrating lower variability and better replication concordance [4] [5]. The selection of appropriate normalization methods, however, remains context-dependent, requiring consideration of experimental design, biological questions, and data characteristics. As RNA-seq applications continue to evolve in pharmaceutical and clinical research, adherence to this structured normalization framework will enhance the reliability and reproducibility of transcriptomic findings.

In bulk RNA-seq analysis, accurate gene expression quantification hinges on a clear understanding of the fundamental units of measurement: reads, fragments, and transcripts. These units form the basis of all downstream normalization and differential expression analyses. A read represents the raw sequence data output, a fragment corresponds to the original RNA molecule segment, and a transcript reflects the biological entity of interest. Confusion between these units can lead to improper normalization and incorrect biological interpretations [3] [16].

The relationship between these units is critical for selecting appropriate normalization methods such as TMM, RPKM, FPKM, and TPM. These methods account for technical variations including sequencing depth, gene length, and RNA population composition to enable valid comparisons within and between samples [10] [2]. This document provides a comprehensive framework for understanding these core quantification units and their practical applications in bulk RNA-seq normalization.

Defining the Fundamental Units

Reads

In sequencing, a read is the string of base calls (A, T, C, G) derived from a single DNA (or RNA-derived) fragment, representing the sequencer's attempt to "read" that fragment's nucleotides [20]. Reads serve as the fundamental raw data unit in RNA-seq, with their quality and length significantly impacting downstream analyses.

- Read Length: The number of nucleotides sequenced from a fragment, fixed by sequencing chemistry and instrument configuration [20]

- Configuration: Single-end sequencing reads one fragment end, while paired-end sequences both ends, providing better mapping resolution and structural variant detection [20]

- Impact on Quantification: Longer reads (100-250 bp) improve transcript isoform detection and mapping across exon junctions [20]

Fragments

A fragment refers to the original segment of RNA (or cDNA) molecule from which reads are generated [3]. This distinction becomes crucial in paired-end sequencing protocols.

- Relationship to Reads: In paired-end sequencing, two reads can correspond to a single fragment, though sometimes one read may represent a fragment if its pair fails to map [3]

- Quantification Impact: Counting fragments rather than reads prevents double-counting when both ends of a fragment successfully map to the same transcript

- Protocol Dependency: Fragment length distribution varies experimentally and must be considered in abundance estimation [21]

Transcripts

A transcript represents the biological RNA molecule of interest, serving as the ultimate target of quantification efforts. Transcript abundance reflects genuine biological expression levels rather than technical measurements [21].

- Biological Significance: Transcript concentration represents the actual number of RNA molecules per cell or unit volume

- Quantification Challenge: Inference from reads/fragments is indirect and requires normalization for technical factors

- Effective Length: The number of positions where a mapped read could start, calculated as transcript length minus read length plus one [21]

Table 1: Key Characteristics of RNA-seq Quantification Units

| Unit | Definition | Primary Use | Technical Dependencies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read | String of base calls from sequencing | Raw data input | Sequencing depth, base quality |

| Fragment | Original RNA/cDNA segment | Paired-end quantification | Library preparation, fragmentation |

| Transcript | Biological RNA molecule | Expression analysis | Gene length, isoform complexity |

Mathematical Relationships and Normalization Methods

From Reads to Expression Values

The transformation of raw read counts to comparable expression values follows a logical progression with distinct normalization steps. The following workflow illustrates this transformation process from raw sequencing data to normalized expression values:

Normalization Methods Framework

RPKM and FPKM

RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads) and FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase per Million mapped fragments) represent closely related normalization approaches that account for both sequencing depth and gene length [22] [16].

RPKM Calculation:

- Divide read counts by total reads (in millions) for sequencing depth normalization

- Divide result by transcript length in kilobases [3]

FPKM Calculation:

- Identical to RPKM but uses fragments instead of reads to accommodate paired-end data [3]

Limitations: Both RPKM and FPKM produce values with sample-specific sums, complicating direct comparison between samples as the same RPKM/FPKM value may represent different proportional abundances in different samples [3] [16].

TPM

TPM (Transcripts Per Million) addresses a key limitation of RPKM/FPKM by reversing the normalization order [3].

TPM Calculation:

- Divide read counts by transcript length in kilobases (yielding Reads Per Kilobase)

- Sum all RPK values and divide by 1,000,000 for a "per million" scaling factor

- Divide RPK values by this scaling factor [3]

Advantage: TPM values sum to the same constant (1,000,000) across samples, enabling direct comparison of a transcript's proportional abundance between samples [3].

TMM

The TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) method operates on raw counts and focuses specifically on between-sample normalization for differential expression analysis [10].

TMM Calculation:

- Select a reference sample and compute log fold-changes (M-values) and absolute expression levels (A-values) for all genes

- Trim extreme M-values and A-values (typically 30% and 5%, respectively)

- Calculate weighted mean of remaining M-values to obtain scaling factor [10]

Application: TMM factors are incorporated into statistical models for differential expression testing by adjusting effective library sizes, addressing composition biases where highly expressed genes in one condition reduce available sequencing "real estate" for other genes [10].

Table 2: Comparison of RNA-seq Normalization Methods

| Method | Normalization For | Primary Application | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPKM/FPKM | Gene length, Sequencing depth | Within-sample comparison | Intuitive interpretation | Sample-specific sums limit between-sample comparison |

| TPM | Gene length, Sequencing depth | Within- and between-sample comparison | Constant sum across samples | Still requires between-sample normalization for DE analysis |

| TMM | Library composition, Sequencing depth | Between-sample differential expression | Robust to differentially expressed genes | Requires raw counts, not applicable to already normalized data |

Experimental Protocols for Quantification

RNA-seq Library Preparation and Sequencing

Proper experimental design is crucial for accurate quantification. The following protocol outlines key steps:

Sample Preparation:

- RNA Isolation: Purify RNA using appropriate methods for sample type (blood, tissue, cell lines)

- RNA Selection: Employ either poly(A)+ selection (enriching mature mRNAs) or rRNA depletion (capturing both mature and immature transcripts) [16]

- Fragmentation: Fragment RNA to 200-500 bp fragments compatible with sequencing platforms

- cDNA Synthesis: Reverse transcribe to cDNA with adaptor ligation

Sequencing Considerations:

- Use paired-end sequencing (e.g., 2×100 bp or 2×150 bp) for improved mapping accuracy and isoform detection [17]

- Sequence all samples to comparable depth (e.g., 20-30 million reads per sample for standard differential expression studies)

- Include technical replicates to assess variability and biological replicates to capture population variation

Read Processing and Quantification Pipeline

The nf-core RNA-seq workflow provides a robust framework for processing raw sequencing data into quantification values [17]:

Input Requirements:

- Paired-end FASTQ files for all samples

- Reference genome FASTA file and annotation GTF file

- Sample sheet specifying sample IDs, file paths, and strandedness

Processing Steps:

- Quality Control: Assess read quality using FastQC

- Read Alignment: Map reads to reference genome using STAR, a splice-aware aligner [17]

- Transcriptome Projection: Convert genomic alignments to transcriptomic coordinates

- Quantification: Generate counts using Salmon in alignment-based mode to model uncertainty in read assignment [17]

Output:

- Gene-level and transcript-level count matrices

- Comprehensive quality control metrics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for RNA-seq Quantification

| Category | Item | Function | Example Products/Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | Poly(A) Selection Beads | Enrichment of mRNA from total RNA | Oligo(dT) magnetic beads |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Removal of ribosomal RNA | Ribozero, NEBNext rRNA Depletion | |

| Library Prep Kits | cDNA synthesis, adaptor ligation | Illumina TruSeq, NEBNext Ultra II | |

| Computational Tools | Read Alignment | Mapping reads to reference genome | STAR, HISAT2, Bowtie2 |

| Quantification | Estimating transcript abundances | Salmon, Kallisto, RSEM | |

| Differential Expression | Statistical analysis of expression changes | edgeR, DESeq2, limma-voom | |

| Reference Data | Genome Sequence | Reference for read alignment | ENSEMBL, UCSC genome databases |

| Gene Annotations | Transcript structure definitions | ENSEMBL GTF, RefSeq, GENCODE |

Critical Considerations for Accurate Quantification

Technical Biases and Challenges

Several technical factors can compromise quantification accuracy if not properly addressed:

- Library Composition Bias: When a few genes dominate transcript abundance, they reduce sequencing coverage for other genes, skewing proportional comparisons [10]

- Protocol Selection Effects: Poly(A)+ selection and rRNA depletion produce fundamentally different RNA populations, making direct TPM comparison invalid between protocols [16]

- Gene Length Effects: Longer genes naturally accumulate more reads independent of actual expression level [22] [2]

- Multimapping Reads: Reads mapping to multiple genomic locations create ambiguity in assignment, requiring probabilistic resolution [21]

Normalization Method Selection Guidelines

Choice of normalization strategy should align with specific research questions:

- Within-Sample Comparisons: TPM provides the most interpretable measure of relative transcript abundance [3]

- Differential Expression Analysis: TMM normalization of raw counts followed by statistical testing with methods like edgeR or DESeq2 offers robust performance [10]

- Cross-Study Comparisons: Batch correction methods (ComBat, limma) must be applied after within-dataset normalization to address technical variability [2]

Validation and Quality Assessment

- Spike-In Controls: Implement external RNA controls of known concentration to monitor technical performance

- Housekeeping Genes: Monitor expression of stable reference genes across samples as internal quality check

- QC Metrics: Assess sequencing depth, mapping rates, and coverage uniformity before proceeding to differential expression analysis

A Deep Dive into Normalization Methods: From RPKM/FPKM to TMM and DESeq2

In bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) analysis, the initial digital read counts obtained from sequencing instruments cannot be directly compared without proper normalization. Raw read counts are influenced by two significant technical biases: sequencing depth (the total number of reads per sample) and gene length (the transcript length in kilobases). Without correction, longer genes will naturally have more reads mapped to them than shorter genes expressed at the same biological abundance, and samples with deeper sequencing will show higher counts across all genes independent of true expression levels. Within-sample normalization methods specifically address these biases to enable meaningful comparison of gene expression levels within a single sample [2] [14].

The most commonly used within-sample normalization methods are RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase Million), FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase Million), and TPM (Transcripts Per Kilobase Million). While these methods share similar goals and mathematical foundations, they differ importantly in their calculation approaches and appropriate applications. Understanding these methods is crucial for proper interpretation of RNA-Seq data, as misapplication can lead to incorrect biological conclusions [3] [16]. These normalization approaches rescale expression values to account for technical variability, thereby revealing the biological signals of interest.

Core Normalization Methods: Calculations and Comparisons

RPKM and FPKM Normalization

RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase Million) was developed for single-end RNA-seq experiments, where each read corresponds to a single fragment. The calculation follows three sequential steps [3] [23]:

- Calculate per million scaling factor: Divide the total reads in the sample by 1,000,000

- Normalize for sequencing depth: Divide read counts by the scaling factor to get Reads Per Million (RPM)

- Normalize for gene length: Divide RPM values by gene length in kilobases to obtain RPKM

FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase Million) is virtually identical to RPKM but designed for paired-end RNA-seq experiments. In paired-end sequencing, two reads can correspond to a single fragment, and FPKM ensures that these fragments are not double-counted [3] [14]. The distinction between reads and fragments represents the only practical difference between RPKM and FPKM. For single-end sequencing, RPKM and FPKM yield identical results [14].

The RPKM/FPKM calculation can be represented by the following formula:

$$RPKM{i} ~or~FPKM{i} = \frac{q{i}}{l{i} * \sum{j} q{j}} * 10^{9}$$

Where $q{i}$ represents raw read or fragment counts for gene i, $l{i}$ is feature length, and $\sum{j} q{j}$ corresponds to the total number of mapped reads/fragments [4].

TPM Normalization

TPM (Transcripts Per Kilobase Million) represents a modification of the RPKM/FPKM approach with a changed order of operations. While TPM accounts for the same technical variables (sequencing depth and gene length), it reverses the normalization sequence [3] [23]:

- Normalize for gene length first: Divide read counts by the length of each gene in kilobases, yielding Reads Per Kilobase (RPK)

- Calculate per million scaling factor: Sum all RPK values in a sample and divide by 1,000,000

- Normalize for sequencing depth: Divide RPK values by this scaling factor to obtain TPM

The TPM calculation formula is:

$$TPM = \frac{{q{i}/l{i}}}{{\sum{j} (q{j}/l_{j})}} * 10^{6}$$

Where $q{i}$ represents reads mapped to transcript i, $l{i}$ is transcript length, and the denominator sums the length-normalized counts across all transcripts [16].

This reversed order of operations has important implications. In TPM, the sum of all normalized values per sample is constant (approximately 1 million), making comparative interpretation more straightforward [3] [23]. As noted in StatQuest, "When you use TPM, the sum of all TPMs in each sample are the same. This makes it easier to compare the proportion of reads that mapped to a gene in each sample" [3].

Table 1: Comparison of Within-Sample Normalization Methods

| Method | Full Name | Sequencing Type | Order of Operations | Sum of Normalized Values | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPKM | Reads Per Kilobase Million | Single-end | Depth then Length | Variable across samples | Within-sample gene comparison [14] |

| FPKM | Fragments Per Kilobase Million | Paired-end | Depth then Length | Variable across samples | Within-sample gene comparison [14] |

| TPM | Transcripts Per Kilobase Million | Both | Length then Depth | Constant (1 million) | Within-sample comparison; preferred for cross-sample analysis [3] [14] |

Comparative Analysis of Normalization Performance

Theoretical and Practical Differences

The different calculation approaches lead to distinct practical properties. Because TPM normalization ends with the per-million scaling, the sum of all TPM values across a sample is constant (1 million). This provides a natural interpretation: a TPM value represents the number of transcripts you would expect to see for a gene if you sequenced exactly one million full-length transcripts [2] [16]. This property makes TPM values more intuitive for understanding relative transcript abundance within and between samples.

In contrast, RPKM and FPKM values sum to different totals across samples due to their calculation method. This means that identical RPKM/FPKM values for a gene in two different samples do not necessarily indicate the same proportional abundance [3] [23]. As one analysis explains, "With RPKM or FPKM, the sum of normalized reads in each sample can be different. Thus, if the RPKM for gene A in Sample 1 is 3.33 and the RPKM in Sample 2 is 3.33, I would not know if the same proportion of reads in Sample 1 mapped to gene A as in Sample 2" [3].

Experimental Comparisons in Biological Research

Empirical studies have compared the performance of these normalization methods in real research scenarios. A 2021 study published in Translational Medicine compared TPM, FPKM, and normalized counts using replicate samples from 20 patient-derived xenograft models spanning 15 tumor types [4]. The researchers evaluated reproducibility using coefficient of variation, intraclass correlation coefficient, and cluster analysis.

This research found that normalized count data (using between-sample methods) tended to group replicate samples from the same model together more accurately than TPM and FPKM data. Furthermore, normalized count data showed lower median coefficient of variation and higher intraclass correlation across replicates compared to TPM and FPKM [4]. These findings highlight that within-sample normalization methods alone may be insufficient for cross-sample comparisons in differential expression analysis.

A 2024 benchmark study further investigated how normalization methods affect downstream analysis when building condition-specific metabolic models [24]. The study compared five normalization methods (TPM, FPKM, TMM, GeTMM, and RLE) using Alzheimer's disease and lung adenocarcinoma datasets. The research found that within-sample normalization methods (TPM and FPKM) produced metabolic models with high variability across samples in terms of active reactions, while between-sample methods (TMM, RLE, GeTMM) showed considerably lower variability [24].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of Normalization Methods

| Performance Metric | RPKM/FPKM | TPM | Between-Sample Methods (TMM, RLE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Within-sample comparison | Suitable [14] | Suitable [14] | Not primary purpose |

| Cross-sample comparison | Not recommended [14] [25] | Limited suitability [25] [16] | Recommended [4] [25] |

| Sum of normalized values | Variable [3] | Constant (~1 million) [3] | Variable |

| Effect on downstream analysis | High variability in metabolic models [24] | High variability in metabolic models [24] | Lower variability in metabolic models [24] |

| Reproducibility across replicates | Lower compared to normalized counts [4] | Lower compared to normalized counts [4] | Higher in replicate analysis [4] |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Workflow for Calculation and Analysis

The following workflow diagram illustrates the procedural steps for implementing within-sample normalization methods:

Detailed Protocol for TPM Calculation

For researchers implementing these calculations directly, here is the step-by-step protocol for TPM normalization, which is currently considered the most robust among the within-sample methods [3]:

Step 1: Normalize for gene length

- Input: Raw read counts for each gene

- For each gene, divide the read count by the transcript length in kilobases

- This yields Reads Per Kilobase (RPK) values

- Formula: $RPKi = \frac{\text{read count}i}{\text{transcript length in kb}}$

Step 2: Calculate sample-specific scaling factor

- Sum all RPK values in the sample

- Divide this sum by 1,000,000 to create the "per million" scaling factor

- Formula: $\text{Scaling factor} = \frac{\sum RPK_i}{1,000,000}$

Step 3: Normalize for sequencing depth

- Divide each RPK value by the scaling factor calculated in Step 2

- This yields the final TPM values

- Formula: $TPMi = \frac{RPKi}{\text{Scaling factor}}$

Validation check: The sum of all TPM values in the sample should equal approximately 1,000,000 [3] [23].

For RPKM/FPKM calculation, the protocol differs in the order of operations: normalize for sequencing depth first (RPM calculation), then normalize for gene length.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for RNA-Seq Normalization

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| RSEM | Transcript quantification and TPM calculation [4] | Standalone software package |

| Kallisto | Pseudoalignment and TPM calculation [16] | R package or standalone |

| Salmon | Transcript quantification and TPM calculation [16] | R package or standalone |

| SAMtools | Processing alignment files [4] | Command-line tool |

| HTSeq | Generate raw read counts from BAM files [4] | Python package |

| DESeq2 | Between-sample normalization and differential expression [4] [24] | R/Bioconductor package |

| edgeR | Between-sample normalization and differential expression [24] | R/Bioconductor package |

Applications and Limitations in Research Contexts

Appropriate Use Cases

Within-sample normalization methods serve specific purposes in RNA-Seq analysis. RPKM, FPKM, and TPM are all appropriate for comparing expression levels of different genes within the same sample [2] [14]. For example, these methods can answer questions such as "Is Gene A more highly expressed than Gene B in this specific sample?" after accounting for differences in gene length and sequencing depth.

TPM has become the preferred within-sample metric because it enables more straightforward comparisons across samples. As noted in the literature, "TPM is a better unit for RNA abundance since it respects the invariance property and is proportional to the average relative molar concentration, and thus adopted by the latest computational algorithms for transcript quantification" [16]. When visualizing gene expression patterns in heatmaps or conducting exploratory analysis across limited sample sets, TPM values often provide a reasonable starting point.

Critical Limitations and Misapplications

A critical limitation of all within-sample normalization methods is that they do not account for library composition effects, which can create significant biases in cross-sample comparisons [4] [16]. These composition effects occur when a few highly expressed genes consume a substantial portion of the sequencing depth, thereby distorting the apparent expression of other genes in the sample [18].

As explicitly stated in current literature, "RPKM, FPKM, and TPM represent the relative abundance of a transcript among a population of sequenced transcripts, and therefore depend on the composition of the RNA population in a sample" [16]. This means that differences in transcript distribution between samples – such as those caused by different RNA extraction methods, library preparation protocols, or biological conditions – can make TPM values incomparable despite their normalization [16].

For differential expression analysis between conditions, specialized between-sample normalization methods like TMM (edgeR) or RLE (DESeq2) are generally recommended over direct comparison of TPM values [4] [25]. These methods specifically address composition biases that within-sample normalization cannot correct.

Within-sample normalization methods RPKM, FPKM, and TPM play essential roles in RNA-Seq data analysis by accounting for technical biases from gene length and sequencing depth. While RPKM and FPKM served as early standards, TPM has emerged as the preferred method due to its constant sum across samples, which facilitates more intuitive interpretation. However, researchers must recognize that these within-sample methods have limitations, particularly for cross-sample comparisons, where between-sample normalization approaches generally provide more robust results for differential expression analysis. Proper selection of normalization strategies remains fundamental to deriving accurate biological insights from RNA-Seq data.

The evolution of RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data analysis has witnessed a significant shift in normalization methodologies, moving from traditional measures like RPKM and FPKM towards Transcripts Per Million (TPM). This application note delineates the critical procedural distinction in TPM's calculation order—normalizing for gene length before sequencing depth—and its profound impact on the accuracy of transcriptomic studies. Framed within a comprehensive evaluation of bulk RNA-seq normalization methods, including TMM, RPKM, and FPKM, we provide structured quantitative comparisons, detailed experimental protocols, and essential reagent solutions. This resource is designed to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the knowledge to implement TPM effectively, thereby enhancing the reliability of inter-sample comparisons and downstream analyses in translational research.

Normalization is a critical first step in bulk RNA-seq data analysis, correcting for technical variations to enable valid biological conclusions. Key technical biases include sequencing depth (the total number of reads per sample) and gene length (longer genes generate more reads at identical expression levels) [2]. Without correction, these factors mask true biological differences and lead to false discoveries.

The field has developed a spectrum of normalization methods, often categorized by their application scope:

- Within-sample normalization: Adjusts for gene length and sequencing depth to compare expression levels of different genes within the same sample. RPKM, FPKM, and TPM fall into this category [2].

- Between-sample normalization: Adjusts for differences in library composition and size to enable comparisons of the same gene across different samples. Methods like TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) and RLE (Relative Log Expression) are designed for this purpose [2] [5].

Understanding this distinction is vital for selecting the appropriate tool. While RPKM/FPKM and TPM are often grouped together, a fundamental difference in their calculation order places TPM in a superior position for specific applications, a nuance explored in this note.

The TPM Paradigm: A Critical Difference in Order of Operations

The Mathematical Foundation

TPM, RPKM, and FPKM all account for sequencing depth and gene length, but the order of operations in TPM calculation confers a distinct advantage [3] [14].

RPKM/FPKM Calculation Workflow:

- Normalize for sequencing depth: Divide the read counts for a gene by the total number of reads (in millions) in the sample, yielding Reads/Fragments Per Million (RPM).

- Normalize for gene length: Divide the RPM values by the gene length in kilobases to yield RPKM or FPKM [3].

TPM Calculation Workflow:

- Normalize for gene length: Divide the read counts for each gene by its length in kilobases, giving Reads Per Kilobase (RPK).

- Sum all RPK values in a sample and divide this number by 1,000,000 to obtain a sample-specific scaling factor.

- Normalize for sequencing depth: Divide each RPK value by this scaling factor to yield TPM [3].

The following diagram visualizes this critical difference in workflow:

The Profound Impact: Proportionality and Sample Comparison

The reversed order of operations has a profound practical consequence: in TPM, the sum of all TPM values in each sample is always equal to one million [3] [14].

This property makes TPM a proportional measure. If a gene has a TPM value of 500 in two different samples, it represents the same proportion of the total transcribed mRNA in each sample (500 / 1,000,000 = 0.05%) [3]. This is not guaranteed with RPKM/FPKM, where the sum of normalized counts can vary between samples, making it difficult to determine if the same proportion of reads mapped to a gene across samples [3]. Consequently, TPM is generally considered more accurate for comparing the relative abundance of a specific transcript across different samples [14].

Comparative Quantitative Analysis of Normalization Methods

The following table synthesizes findings from key benchmarking studies to provide a clear, structured comparison of popular normalization methods, highlighting their performance in various analytical contexts.

Table 1: Benchmarking of RNA-seq Normalization Methods Across Different Analytical Applications

| Normalization Method | Category | Key Assumption/Principle | Performance in Differential Expression (DE) Analysis | Performance in Metabolic Model Reconstruction (iMAT) [5] | Recommendation for Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPM | Within-sample | Sum of normalized counts is constant per sample. | Less suitable for DE analysis alone; outperformed by between-sample methods [4]. | High variability in model size and content; high number of predicted affected reactions [5]. | Within-sample comparisons; cross-sample comparisons when total RNA content is similar [14] [26]. |

| FPKM/RPKM | Within-sample | Normalizes for depth then length. | Not recommended for DE analysis; similar or inferior performance to TPM [4]. | Performance similar to TPM; high variability and high number of predicted affected reactions [5]. | Not recommended for between-sample comparisons. Use for gene count comparisons within a single sample [14]. |

| TMM | Between-sample | Most genes are not differentially expressed. | Robust performance; used by edgeR for DE analysis [4] [5]. |

Low variability in model size; consistent and lower number of significantly affected reactions [5]. | Between-sample comparisons; DE analysis when library sizes and compositions differ. |

| RLE | Between-sample | Similar assumption to TMM; used by DESeq2. |

Robust performance; considered a best practice for DE analysis [5]. | Low variability in model size; consistent performance comparable to TMM [5]. | Between-sample comparisons; DE analysis, especially with DESeq2. |

| Normalized Counts (e.g., via DESeq2/edgeR) | Between-sample | Employs sophisticated scaling factors (e.g., RLE, TMM). | Superior performance: Highest intraclass correlation (ICC) and lowest coefficient of variation (CV) among replicates [4]. | Not explicitly tested, but underlying principles inform RLE/TMM. | Best choice for DE analysis and cross-sample comparisons [4]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Best-Practice Bulk RNA-seq Analysis with STAR and Salmon

This protocol outlines a hybrid workflow that leverages the alignment quality control of STAR with the accurate, uncertainty-aware quantification of Salmon [17].

- Objective: To generate high-quality gene-level count matrices from raw RNA-seq FASTQ files, suitable for both within-sample (TPM) and between-sample (Normalized Counts) analyses.

- Experimental Principles: This workflow addresses two levels of uncertainty: 1) identifying the transcript of origin for each read, and 2) converting these assignments into a count matrix that models probabilistic assignments [17].

Workflow Diagram:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Input Preparation:

- Obtain paired-end RNA-seq FASTQ files. The use of paired-end reads is strongly recommended for more robust expression estimates [17].

- Prepare a sample sheet in the nf-core format, specifying sample IDs, paths to FASTQ files (

fastq_1andfastq_2), and strandedness (recommended: "auto"). - Obtain the reference genome sequence (FASTA) and annotation (GTF/GFF) files for your species.

Spliced Alignment with STAR:

- Use the STAR aligner to perform splice-aware alignment of reads to the reference genome.

- This step generates BAM files, which are crucial for generating comprehensive quality control (QC) metrics for individual samples [17].

Alignment-Based Quantification with Salmon:

- Use Salmon in its alignment-based mode, using the BAM files generated by STAR as input.

- Salmon will internally project the genomic alignments onto the transcriptome and use its statistical model to estimate transcript abundances, effectively handling the uncertainty in read assignments [17].

- The primary output of this step is a set of sample-level abundance estimates in TPM.

Gene-Level Count Matrix Generation:

- Aggregate the sample-level transcript abundance estimates from all samples into a single gene-level count matrix.

- Tools like

tximportin R can be used to summarize transcript-level TPM and estimated counts to the gene level, creating the final matrices for downstream analysis.

Protocol: Differential Expression Analysis with Normalized Counts

While TPM is valuable for qualitative assessment, differential expression analysis requires between-sample normalized counts for optimal performance [4].

- Objective: To identify genes that are statistically significantly differentially expressed between two or more biological conditions.

- Experimental Principles: This protocol relies on count-based methods that explicitly model the mean-variance relationship in RNA-seq data, using robust between-sample normalization factors like TMM or RLE [4] [5].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Input: Start with the gene-level raw count matrix generated in Section 4.1.

- Normalization and Model Fitting:

- Use established Bioconductor packages such as

DESeq2oredgeR. - In

DESeq2, theDESeqDataSetFromMatrixfunction is used to create a data object. The internalDESeqfunction then performs its default normalization (RLE) and fits negative binomial generalized linear models to test for differential expression. - In

edgeR, thecalcNormFactorsfunction calculates scaling factors using the TMM method, which are then used in the subsequent statistical testing (e.g.,glmQLFTest).

- Use established Bioconductor packages such as

- Result Interpretation: Extract the list of significantly differentially expressed genes based on False Discovery Rate (FDR) adjusted p-values and log2 fold changes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents, tools, and software essential for implementing the protocols described in this application note.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Bulk RNA-seq Analysis

| Item Name | Specifications / Version | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| STAR Aligner | Version 2.7.x or higher | Spliced alignment of RNA-seq reads to a reference genome; generates BAM files for QC and downstream quantification [17]. |

| Salmon | Version 1.5.0 or higher | Fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript abundances; can operate in alignment-based mode for use with STAR BAM files [17]. |

| nf-core/rnaseq | A community-built, peer-reviewed pipeline | Automated, reproducible workflow that orchestrates the entire process from FASTQ to count matrix, including STAR and Salmon [17]. |

| DESeq2 R Package | Bioconductor release | Performs differential expression analysis from raw count data using its RLE normalization and negative binomial models [4] [5]. |

| edgeR R Package | Bioconductor release | Performs differential expression analysis from raw count data using the TMM normalization method [5]. |

| Reference Transcriptome | e.g., GENCODE, Ensembl | A comprehensive set of transcript sequences and annotations (FASTA and GTF); essential for alignment and quantification. |

| External RNA Controls (ERCC) | ERCC Spike-In Mixes | Artificial RNA spikes at known concentrations; used in specialized protocols to establish experimental ground truth for normalization assessment [27]. |

The "TPM Revolution" is rooted in a fundamental yet simple change in calculation order that transforms the metric into a proportional measure, offering a significant advantage over RPKM/FPKM for comparing transcript abundance across samples. This application note has detailed the mathematical underpinnings, quantitative performance, and practical protocols for implementing TPM and other normalization methods.