Bulk RNA-Seq Sequencing Depth Guide: Optimizing Depth and Read Length for Robust Results

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on determining optimal sequencing depth and read length for bulk RNA-Seq experiments.

Bulk RNA-Seq Sequencing Depth Guide: Optimizing Depth and Read Length for Robust Results

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on determining optimal sequencing depth and read length for bulk RNA-Seq experiments. It covers foundational principles linking depth to statistical power and data quality, offers methodological guidance for application-specific requirements—from differential expression to isoform detection—and presents troubleshooting strategies for challenging samples like FFPE or low-input RNA. The guide also synthesizes current empirical evidence and best practices from major consortia to help scientists design cost-effective and robust transcriptomic studies, ensuring data quality and reproducibility in both discovery and clinical settings.

Understanding Bulk RNA-Seq Fundamentals: How Depth, Read Length, and Experimental Design Impact Data Quality

In bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq), the quality and interpretability of data are fundamentally governed by two key experimental parameters: sequencing depth and read length. Sequencing depth, or read depth, refers to the total number of reads sequenced per sample, directly influencing the statistical power to detect transcripts, especially those that are lowly expressed [1] [2]. Read length determines the number of base pairs sequenced in each individual read, impacting the ability to uniquely map reads to the reference genome and to resolve specific transcript features such as splice junctions [1] [3]. Selecting the optimal combination of these metrics is not a one-size-fits-all process; it is a critical strategic decision that must be aligned with the specific biological questions, the organism's transcriptome complexity, and the quality of the starting RNA material [4]. A well-considered choice ensures that resources are used efficiently to generate biologically meaningful and statistically robust results, whether the goal is simple gene expression profiling or the complex task of novel transcript assembly.

Sequencing Depth and Read Length by Research Goal

The optimal configuration for an RNA-Seq experiment is primarily dictated by its overarching aims. The table below summarizes the recommended sequencing depth and read length for common research applications in bulk RNA-Seq.

Table 1: Recommendations for sequencing depth and read length based on research objective

| Research Objective | Recommended Sequencing Depth (Million Reads) | Recommended Read Length | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene-Level Differential Expression | 5 - 25 [1] [5] to 30 - 60 [4] | ≥ 50 bp, single-end or paired-end [1] [6] | Sufficient for snapshot of highly expressed genes; 15M reads may be adequate with good replication [6] [2]. |

| Detection of Lowly Expressed Genes | 30 - 60 [1] [6] | ≥ 50 bp, paired-end recommended [6] | Deeper sequencing increases power to detect and quantify low-abundance transcripts [1] [2]. |

| Isoform Detection & Alternative Splicing | 30 - 60 [1] to ≥ 100 [4] | Paired-end (2x75 bp or 2x100 bp) [1] [4] | Longer paired-end reads help cover exon junctions and resolve transcript structures [1] [6]. |

| Novel Transcriptome Assembly | 100 - 200 [1] [5] | Longer paired-end (e.g., 2x100 bp) [1] | Maximum depth and length are beneficial for comprehensive coverage and identification of novel features [7]. |

| Fusion Gene Detection | 60 - 100 [4] | Paired-end (2x75 bp or 2x100 bp) [4] | Paired-end reads are required to anchor breakpoints; longer reads provide cleaner resolution [4]. |

| Allele-Specific Expression | ≥ 100 [4] | Paired-end (2x75 bp or 2x100 bp) [4] | High depth is essential to accurately estimate variant allele frequencies and minimize sampling error [4]. |

| Small RNA / miRNA Analysis | 1 - 5 [1] [5] | Single-end 50 bp [1] | A 50 bp read typically covers the entire small RNA plus adapter for accurate identification [1]. |

| Targeted RNA Expression | ~3 [1] [5] | As per panel design | Focused panels require far fewer reads as they target a specific subset of genes [1]. |

The Critical Role of Experimental Design

Biological Replicates and Sequencing Depth

A cornerstone of robust RNA-Seq experimental design is understanding the relationship between sequencing depth and biological replication. While increasing depth improves the detection of lowly expressed genes, numerous studies have demonstrated that, for differential expression analysis, increasing the number of biological replicates provides greater statistical power than increasing sequencing depth per sample [6] [2]. Biological replicates, which are different biological samples under the same condition, are essential for measuring natural biological variation and ensuring findings are generalizable [6] [8]. Technical replicates, which involve re-sequencing the same biological sample, are generally considered unnecessary as technical variation in RNA-Seq is typically low compared to biological variation [6]. As a baseline, a minimum of three biological replicates per condition is recommended, with four or more being ideal for reliable detection of differentially expressed genes [6] [8] [9].

Sample Quality and Its Impact on Design

The quality and integrity of the input RNA significantly influence the success of an RNA-Seq experiment and must be considered when determining sequencing parameters. The DV200 metric (the percentage of RNA fragments longer than 200 nucleotides) is a key indicator, especially for partially degraded samples like those from Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tissues [4].

Table 2: Adjusting protocols and depth based on RNA integrity

| RNA Integrity (DV200) | Recommended Library Protocol | Recommended Sequencing Depth Adjustment |

|---|---|---|

| > 50% (High Quality) | Poly(A) or rRNA depletion; standard read lengths (2x75 bp - 2x100 bp) [4] | Standard depth for the research objective [4]. |

| 30 - 50% (Moderate Degradation) | Prefer rRNA depletion or capture-based protocols [4] | Increase depth by 25 - 50% to offset reduced complexity [4]. |

| < 30% (High Degradation) | Avoid poly(A) selection; use rRNA depletion or capture [4] | Significantly deeper sequencing (≥ 75-100 million reads) is required [4]. |

For degraded samples or those with limited input, incorporating Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) is highly recommended. UMIs are short random sequences added to each molecule before amplification, allowing for accurate bioinformatic removal of PCR duplicates. This ensures that the read count reflects the original RNA abundance and not amplification bias, which is particularly valuable when sequencing deeply [4].

Protocols and Best Practices

Protocol 1: Designing a Standard Differential Gene Expression Experiment

This protocol outlines the steps for a typical bulk RNA-Seq experiment aimed at identifying differentially expressed genes between two or more conditions.

- Define Hypothesis and Objectives: Clearly state the biological question and primary outcome (e.g., "Identify genes differentially expressed in treated vs. control cells").

- Determine Number of Biological Replicates:

- Select Sequencing Depth and Read Length:

- Library Preparation:

- Use a stranded mRNA-seq library preparation kit to retain information on the transcript strand, which improves annotation and is essential for certain analyses like antisense transcription.

- For high-quality RNA (RIN > 8, DV200 > 70%), poly(A) selection is appropriate to enrich for coding mRNA [9].

- Sequencing and Data Analysis:

- Multiplex all samples and sequence in the same lane/flow cell to avoid lane-specific batch effects [9].

- Perform standard QC (e.g., FastQC), align reads to a reference genome (e.g., HISAT2, STAR), and quantify gene expression (e.g., featureCounts, Salmon).

Protocol 2: Designing an Experiment for Isoform Detection and Novel Discovery

This protocol is for projects where the goal is to study alternative splicing, identify novel isoforms, or perform transcript-level quantification.

- Define Hypothesis and Objectives: Clearly state the targets (e.g., "Characterize all isoforms of gene X in a specific tissue," "Perform de novo transcriptome assembly").

- Prioritize Sequencing Depth and Length:

- Allocate a larger budget per sample for sequencing. Target a minimum of 100 million paired-end reads per sample [4].

- Use longer paired-end reads (2x100 bp or longer). The longer read length increases the likelihood that a single read will span multiple exons or an entire splice junction, which is critical for resolving isoform structures [1] [6].

- Library Preparation and RNA Quality:

- Use a stranded, total RNA library preparation protocol with rRNA depletion instead of poly(A) selection. This ensures the capture of both coding and non-coding RNAs, providing a more complete view of the transcriptome [9].

- Be exceptionally careful with RNA quality. Use high-quality RNA extraction methods and restrict analysis to samples with high RIN/RQS numbers where possible [6].

- Sequencing and Data Analysis:

- Sequence to the recommended depth. For novel transcript assembly, saturation may not be reached even at high depths, particularly for non-coding RNAs [7].

- Utilize assembly-focused bioinformatic pipelines (e.g., StringTie [7]) for transcript reconstruction and tools designed for isoform quantification (e.g., Cufflinks, StringTie).

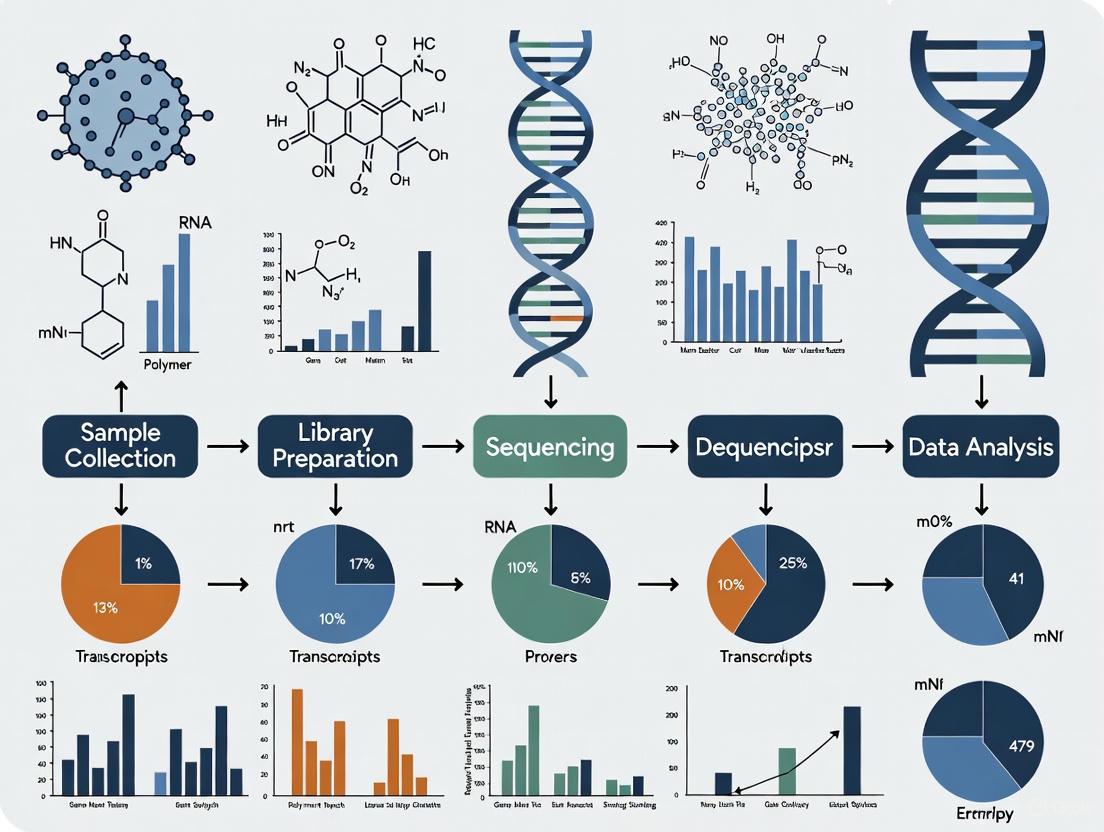

Visual Guide to Experimental Design

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points and recommendations for designing a bulk RNA-Seq experiment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of an RNA-Seq experiment relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions and their functions.

Table 3: Essential research reagent solutions for RNA-Seq experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stranded mRNA-Seq Kit | Library preparation that selectively enriches for polyadenylated RNA and preserves strand of origin. | Ideal for standard gene expression studies with high-quality RNA input [8]. |

| Total RNA-Seq Kit with rRNA Depletion | Library preparation that removes ribosomal RNA (rRNA) to enrich for other RNA species (mRNA, lncRNA). | Essential for isoform discovery, non-coding RNA analysis, or when working with degraded RNA (e.g., FFPE) where poly(A) tails may be lost [4] [9]. |

| RNA Integrity Number (RIN) / RQS Assay | Microfluidics-based assay (e.g., Bioanalyzer, TapeStation) to quantitatively assess RNA quality. | A critical QC step; RIN > 8 is recommended for mRNA-Seq, while rRNA-depletion protocols are more tolerant of lower RIN values [4] [6]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide tags added to each RNA molecule during library prep before amplification. | Corrects for PCR amplification bias and duplicates, crucial for accurate quantification, especially with low-input or degraded samples [4]. |

| Spike-in RNA Controls | Synthetic RNA molecules added in known quantities to the sample. | Serves as an internal control for monitoring technical performance, including sensitivity, dynamic range, and quantification accuracy across samples [8]. |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | Reagents (e.g., RNAlater) that immediately stabilize cellular RNA to prevent degradation. | Preserves RNA integrity during sample collection, storage, and transportation, especially from remote locations [8]. |

The Critical Link Between Biological Replicates and Sequencing Depth for Statistical Power

Bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) is a foundational tool in transcriptome analysis, yet many studies struggle with achieving sufficient statistical power for reliable results. Due to considerable financial and practical constraints, RNA-seq experiments often employ limited biological replication, with surveys indicating approximately 50% of studies on human samples use six or fewer replicates, a figure that rises to 90% for non-human samples [10] [11]. This tendency toward underpowered designs directly threatens the replicability of research findings. Recent large-scale replication projects in preclinical cancer biology have reported success rates as low as 46% [10] [11]. This application note examines the critical, and often misunderstood, relationship between biological replicates and sequencing depth, providing structured guidance and protocols to optimize experimental design for robust differential expression analysis.

Quantitative Guidelines for Experimental Parameters

The choice of replicates and sequencing depth is not one-size-fits-all but must be aligned with the specific goals of the study. The tables below summarize evidence-based recommendations for these parameters.

Table 1: Recommended Sequencing Depth for Bulk RNA-Seq Experiments

| Experimental Goal | Recommended Mapped Reads | Key Considerations and Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Differential Gene Expression (DGE) | 5 - 15 million [2] | A good bare minimum for a snapshot of highly expressed genes. |

| Standard Gene-Level DGE | 20 - 50 million [2] [4] | Provides a more global view of gene expression; a common standard in many published human RNA-Seq experiments [2]. |

| Robust Gene-Level DGE (Sweet Spot) | 25 - 40 million (paired-end) [4] | Stabilizes fold-change estimates across expression quantiles without wasting reads on already-well-sampled transcripts. |

| Isoform Detection & Alternative Splicing | ≥ 100 million (paired-end) [4] | Comprehensive isoform coverage requires significantly greater depth to capture a full range of splice events. |

| Fusion Detection | 60 - 100 million (paired-end) [4] | Ensures sufficient split-read support for breakpoint resolution by fusion callers. |

| Allele-Specific Expression (ASE) | ~100 million (paired-end) [4] | Essential depth to accurately estimate variant allele frequencies and minimize sampling error. |

Table 2: Recommended Number of Biological Replicates

| Scenario | Recommended Replicates per Condition | Rationale and Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute Minimum | 5 - 7 [10] [11] | Caution is advised with fewer than seven replicates due to high heterogeneity in results [11]. |

| Robust DEG Detection | ≥ 6 [10] | Considered necessary for robust detection of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) [10]. |

| Identifying Majority of DEGs | ≥ 12 [10] [11] | Required when it is important to identify the majority of DEGs across all fold changes [10]. |

| Target for Power (≥80%) | ~10 [11] | Suggested to achieve sufficient statistical power under budget constraints [11]. |

| ENCODE Standard | 2 or more [12] | Minimum standard; must demonstrate high replicate concordance (Spearman correlation >0.9) [12]. |

Experimental Protocols for Power Assessment and Replicability

Power Analysis Using the PROPER Tool

Power analysis is a critical step for planning a statistically sound RNA-seq experiment. The PROPER (PROspective Power Evaluation for RNAseq) Bioconductor package provides a comprehensive solution for complex RNA-seq data [13].

Detailed Methodology:

- Pilot Data Input: The procedure requires a pilot dataset, which can be real or simulated. For simulation, PROPER uses parameters estimated from public data sets (e.g., library size, normalized gene expression, dispersion, percent of genes that are differentially expressed, and log-fold changes of DEGs) [14].

- Simulation and Modeling: PROPER performs Monte Carlo simulations based on the negative binomial distribution, which accurately models the over-dispersion characteristic of RNA-seq count data. It simulates full RNA-seq experiments under various design scenarios (e.g., paired or unpaired samples, different numbers of replicates, different sequencing depths) [14] [13].

- Power Calculation: For each simulated experiment, PROPER runs differential expression analysis using established methods (e.g., DESeq2, edgeR) and calculates statistical power. Power is defined as the proportion of true DEGs that are correctly identified as significant at a specified False Discovery Rate (FDR) threshold [14] [13].

- Stratified Analysis: A key feature is its ability to stratify power calculations by gene expression level and fold-change, allowing researchers to see if their design is adequate for detecting DEGs of biological interest, which often have modest fold-changes and/or low expression [13].

- Output and Visualization: The tool generates comprehensive visualizations, such as the

plotAllfunction, to display stratified power, enabling researchers to make an informed decision on the optimal balance between replicate number and sequencing depth for their specific goals and budget [13].

Bootstrapping for Estimating Replicability

For researchers who already have a dataset, a bootstrapping procedure can estimate the expected replicability and precision of their results, which is particularly valuable for small cohort sizes [10] [11].

Detailed Methodology:

- Subsampling: From the full dataset, repeatedly (e.g., 100 times) randomly select a small cohort of N biological replicates per condition, mirroring the size of the original or planned study [10] [11].

- Differential Expression Analysis: For each subsampled "experiment," perform a full differential expression analysis to identify a list of significant DEGs [10] [11].

- Metric Calculation: Calculate replicability and precision metrics by comparing the results across all subsampled experiments. Common metrics include the Jaccard index (overlap of DEG lists) and precision-recall curves [10] [11].

- Performance Prediction: The level of agreement (or disagreement) between the subsampled results serves as a strong predictor for the real-world replicability of the analysis. This procedure helps diagnose whether a small-scale study is prone to a high rate of false positives or is likely to yield precise, albeit potentially incomplete, results [10] [11].

Visualizing the Relationship Between Key Parameters

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for designing a powered RNA-seq experiment and how key parameters influence the final outcomes of statistical power and replicability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of a powered RNA-seq experiment relies on several key reagents and materials throughout the workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Bulk RNA-Seq

| Item | Function/Application | Specifications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stranded Library Prep Kit | Converts RNA into a sequencing-ready library. Preserves strand orientation of transcripts. | A stranded kit is essential for accurate transcriptome annotation. Must be compatible with RNA input amount and quality (e.g., for degraded FFPE samples) [4] [15]. |

| RNA Spike-In Controls | External RNA controls for technical validation and normalization. | The ENCODE consortium standardizes on the Ambion ERCC Spike-In Mix. Spike-in sequences are added to the genome index and used by quantification tools like RSEM [12]. |

| RNA Integrity Assay | Assesses RNA quality to inform sequencing depth requirements. | Use RIN (RNA Integrity Number) or DV200 (% of RNA fragments >200 nucleotides). DV200 >50% is suitable for standard protocols; 30-50% may require 25-50% more reads [4]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Tags individual RNA molecules to correct for PCR duplication bias. | Crucial for experiments with limited input (≤10 ng) or when sequencing very deeply (>80M reads) to distinguish biological expression from technical amplification [4]. |

| rRNA Depletion Reagents | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA to enrich for mRNA and non-coding RNA. | Preferred over poly(A) selection for degraded RNA samples (DV200 <30%) or when studying non-polyadenylated RNAs [4]. |

| Alignment & Quantification Software | Maps reads to a reference and estimates gene/transcript abundance. | STAR is recommended for splice-aware genome alignment and QC. Salmon (in alignment-based mode) or RSEM is recommended for accurate quantification, handling uncertainty in read assignment [15] [12]. |

| Differential Expression Tools | Identifies statistically significant changes in gene expression. | DESeq2 and edgeR are widely used and show top performance. They model count data using a negative binomial distribution to account for biological variability [14] [15]. |

The Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) Consortium has established comprehensive experimental guidelines and data standards to ensure the production of high-quality, reproducible genomic data. These standards provide a critical framework for researchers designing functional genomics experiments, offering evidence-based recommendations developed through extensive consortium-wide testing and validation. For scientists embarking on bulk RNA-seq research, ENCODE guidelines provide definitive baseline requirements for experimental parameters including sequencing depth, replicate numbers, and quality metrics, thereby reducing costly trial-and-error approaches. Adherence to these standards ensures data interoperability across studies and facilitates meaningful comparisons between datasets generated in different laboratories. This application note synthesizes the current ENCODE recommendations for bulk RNA-seq experiments, with particular emphasis on sequencing depth requirements within the broader context of experimental design.

Bulk RNA-seq Experimental Design

Core Sequencing Requirements

ENCODE has established specific technical standards for bulk RNA-seq experiments to ensure data quality and reproducibility. These requirements address key parameters that significantly impact data utility and reliability. The consortium recommends a minimum read length of 50 base pairs for all RNA-seq experiments, with support for both single-end and paired-end sequencing across all Illumina platforms [12]. The selection between these approaches depends on the experimental aims: paired-end sequencing is particularly recommended for isoform-level differential expression analysis as it provides better mapping across splice junctions.

Library preparation specifics are also addressed in the guidelines. Libraries must be generated from mRNA (poly(A)+), rRNA-depleted total RNA, or poly(A)- populations that are size-selected to be longer than approximately 200 bp to ensure focus on longer transcripts [12]. For experiments utilizing spike-in controls, ENCODE has standardized on the Ambion Mix 1 commercially available spike-ins at a dilution of approximately 2% of final mapped reads to create a standard baseline for RNA expression quantification [12].

A critical consideration in experimental design is the balance between sequencing depth and biological replication. The ENCODE consortium emphasizes that biological replicates are significantly more important than excessive sequencing depth for most gene-level differential expression analyses [6]. This principle guides researchers to allocate resources primarily toward adequate biological replication rather than ultra-deep sequencing, as proper replication enables more accurate estimation of biological variation and more robust statistical analysis.

Replicate Design and Statistical Power

Biological replication represents a cornerstone of reliable RNA-seq experimental design. ENCODE guidelines explicitly state that experiments should have two or more biological replicates, with exemptions granted only for exceptional circumstances such as assays using EN-TEx samples where experimental material is severely limited [12]. Biological replicates—where different biological samples of the same condition are used—are essential for measuring biological variation and must be distinguished from technical replicates, which are generally considered unnecessary in modern RNA-seq due to the relatively low technical variation compared to biological variation [6].

The relationship between replicate number and statistical power is a critical consideration. Research has demonstrated that increasing biological replicates provides substantially greater power for detecting differentially expressed genes than increasing sequencing depth [6]. While the absolute minimum is two replicates, best practices suggest three replicates as an absolute minimum, with four replicates representing the optimum minimum for robust differential expression analysis [9]. This replication strategy enables more precise estimates of mean expression levels and biological variation, leading to more accurate modeling and identification of truly differentially expressed genes.

For specialized RNA-seq applications, modified replicate guidelines exist. For shRNA knockdown followed by RNA-seq and CRISPR genome editing followed by RNA-seq, ENCODE specifies that each replicate should have 10 million aligned reads rather than the standard 30 million, and each experiment must include a corresponding control experiment [12]. Similarly, for siRNA knockdown experiments, each replicate requires 10 million aligned reads plus verification of the percentage knockdown of the targeted factor for each replicate relative to the control [12].

Table: ENCODE Bulk RNA-seq Sequencing Depth Requirements by Application

| Experiment Type | Minimum Aligned Reads | Replicate Requirements | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard bulk RNA-seq | 30 million | 2+ biological replicates | Spearman correlation >0.9 between isogenic replicates |

| Gene-level DE (limited material) | 15 million | >3 biological replicates | Sufficient with good number of replicates |

| Isoform-level DE (known isoforms) | 30 million | 2+ biological replicates | Paired-end reads recommended |

| Isoform-level DE (novel isoforms) | 60 million | 2+ biological replicates | Deeper sequencing required |

| shRNA/CRISPR knockdown | 10 million | 2+ biological replicates | Target verification required |

| Single-cell RNA-seq | 5 million | 10-20 individual experiments | Not considered biologically replicated |

Quality Assessment Metrics

ENCODE establishes clear quality thresholds for bulk RNA-seq data to ensure analytical reliability. A central quality metric is replicate concordance, measured through Spearman correlation of gene-level quantifications. The guidelines specify that isogenic replicates (replicates from the same donor) should demonstrate a Spearman correlation >0.9, while anisogenic replicates (replicates from different donors) should maintain a correlation >0.8 [12]. These thresholds provide objective criteria for assessing technical quality before proceeding with downstream analysis.

The consortium employs uniform processing pipelines that generate comprehensive quality metrics, including Spearman correlation coefficients and read depth assessments [16] [12]. These pipelines use the STAR program for read alignment and the RSEM program for gene and transcript quantification, with alignment files mapped to standard reference sequences (GRCh38, hg19, or mm10) and gene quantifications annotated to GENCODE versions (V24, V19, or M4) [12]. This standardized approach ensures consistency across datasets generated by different consortium members.

Beyond technical metrics, ENCODE emphasizes the importance of metadata audits and experimental annotation. All experiments must pass routine metadata audits before public release, ensuring adequate documentation of experimental parameters, sample characteristics, and processing steps [12]. This comprehensive approach to quality assessment addresses both technical performance and experimental metadata integrity, providing multiple safeguards for data quality.

Experimental Protocols

Bulk RNA-seq Workflow

The ENCODE bulk RNA-seq pipeline follows a standardized workflow that can be applied to both replicated and unreplicated experiments, accommodating paired-end or single-end designs and both strand-specific and non-strand specific libraries [12]. The protocol begins with library preparation from mRNA sources, followed by sequencing with minimum length requirements, then proceeds through quality control, read alignment, and quantification steps. The workflow generates multiple output formats including BAM alignment files, bigWig signal files, and gene quantification files, providing researchers with both raw and processed data for analysis.

Library Preparation and Sequencing

The library preparation phase requires careful attention to RNA quality and appropriate selection of RNA fractions. The ENCODE protocol specifies that libraries must be generated from mRNA (poly(A)+), rRNA-depleted total RNA, or poly(A)- populations that are size-selected to be longer than approximately 200 bp [12]. For standard coding mRNA analysis, poly(A)+ selection is recommended, while for experiments investigating long non-coding RNA, the total RNA method with rRNA depletion should be employed [9].

RNA quality is a critical factor in library preparation success. The ENCODE guidelines emphasize that high RNA integrity (RIN > 8) is essential for mRNA library preparations [9]. For degraded RNA samples, such as those from clinical specimens, the total RNA method is more appropriate. During library preparation, inclusion of ERCC spike-in controls is standard practice in ENCODE protocols, using precisely defined concentrations that should result in approximately 2% of final mapped reads deriving from spike-in sequences [12].

For the sequencing phase itself, ENCODE recommends 30 million aligned reads per sample for standard bulk RNA-seq experiments [12]. While older projects targeted 20 million reads, the current standard of 30 million provides sufficient depth for most gene-level differential expression analyses. For specialized applications requiring detection of lowly-expressed genes or isoform-level analysis, deeper sequencing of 30-60 million reads is recommended, with the higher end of this range reserved for novel isoform discovery [6].

Data Processing and Analysis

The ENCODE uniform processing pipeline for bulk RNA-seq employs specific tools and standards to ensure consistent data processing across the consortium. The primary alignment is performed using the STAR program, with some historical data also processed using TopHat [12]. Following alignment, gene and transcript quantification is conducted with the RSEM program, which generates multiple expression measures including expected counts, TPM (transcripts per million), and FPKM (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million) [12].

A critical consideration in data analysis is the appropriate use of different quantification types. While gene-level quantifications can be used confidently for downstream analysis, transcript-level quantifications should be treated with caution because quantifications of individual transcript isoforms can differ substantially depending on the processing pipeline employed and are of unknown accuracy [12]. This distinction is important for researchers planning their analytical approach.

The pipeline produces several key output files that facilitate different types of downstream analysis. These include BAM files containing genome alignments, bigWig files containing normalized RNA-seq signal for visualization, and TSV files containing gene quantifications with spike-in measurements [12]. The quality metrics generated by the pipeline, including Spearman correlation values between replicates, provide objective measures for assessing data quality before proceeding with advanced analyses.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of ENCODE-standard bulk RNA-seq experiments requires specific reagents and materials that have been validated through consortium-wide use. These reagents address key aspects of the experimental workflow from sample preparation to sequencing, ensuring consistency and reproducibility across different laboratories and experimental batches.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Bulk RNA-seq Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| ERCC Spike-in Controls | RNA quantification standards | Ambion Mix 1, ~2% of final mapped reads [12] |

| Poly(A) Selection Beads | mRNA enrichment | For coding mRNA analysis [9] |

| rRNA Depletion Reagents | Total RNA preparation | For lncRNA studies [9] |

| Strand-Specific Library Prep Kit | Library construction | Maintains strand orientation information [12] |

| High-Sensitivity DNA Assay | Library quantification | Accurate quantification for sequencing [9] |

| STAR Aligner | Read alignment | Spliced transcript alignment to reference [12] |

| RSEM Software | Gene quantification | Calculates TPM, FPKM, expected counts [12] |

Antibody Validation Standards

For researchers incorporating chromatin analyses alongside transcriptomic profiling, ENCODE has established rigorous antibody characterization standards. These guidelines are particularly relevant for ChIP-seq experiments investigating transcription factor binding or histone modifications. The consortium requires two validated tests for each antibody—a primary and secondary characterization—with repetition required for each new antibody lot number [17].

For transcription factor antigens, the primary characterization typically involves immunoblot analysis performed on protein lysates from whole-cell extracts, nuclear extracts, or chromatin preparations. The ENCODE standard specifies that the primary reactive band should contain at least 50% of the signal observed on the blot, ideally corresponding to the expected size of the target protein [17]. When immunoblot analysis is unsuccessful, immunofluorescence demonstrating expected nuclear staining patterns serves as an acceptable alternative primary characterization method.

The secondary characterization for transcription factor antibodies involves independent validation such as similar immunoblot patterns across multiple cell types, immunostaining in a different cell type, or comparison with an independent antibody [17]. For histone modification antibodies, the primary test is typically peptide microarray or immunofluorescence, while the secondary test involves histone peptide immunoblot [18] [17]. These comprehensive validation requirements address common issues with antibody specificity and reactivity, ensuring that ChIP-seq data generated alongside RNA-seq profiles target the intended epitopes with minimal cross-reactivity.

The ENCODE standards and baseline recommendations provide an essential foundation for designing robust bulk RNA-seq experiments. By adhering to these evidence-based guidelines for sequencing depth, replicate numbers, quality metrics, and experimental protocols, researchers can generate high-quality, reproducible data that enables meaningful biological insights. The consortium's emphasis on biological replication over excessive sequencing depth, standardized processing pipelines, and clear quality thresholds offers a practical framework for efficient experimental design. As genomic technologies continue to evolve, these standards will undoubtedly be refined, but the core principles of rigor, reproducibility, and data interoperability will remain essential for advancing our understanding of gene regulation.

How RNA Quality (RIN/RQS and DV200) Influences Effective Sequencing Depth

In bulk RNA-seq research, the quality of input RNA is a fundamental determinant of data quality and reliability. The RNA Integrity Number (RIN) or RNA Quality Score (RQS) and the DV200 metric (percentage of RNA fragments >200 nucleotides) serve as crucial indicators of RNA suitability for sequencing applications. While RIN/RQS provides a comprehensive assessment of RNA degradation based on electrophoretic traces, DV200 specifically quantifies the proportion of fragments long enough for successful library construction [19] [20]. These metrics directly influence effective sequencing depth by determining the proportion of usable fragments, library complexity, and ultimately, the number of informative reads obtained per sample. Research demonstrates that RNA quality metrics correlate strongly with sequencing success, particularly for degraded samples from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues [19] [21]. Understanding these relationships enables researchers to optimize sequencing depth based on sample quality, ensuring cost-effective experimental design while maintaining data integrity.

Comparative Analysis of RNA Quality Metrics

Metric Definitions and Methodological Basis

RIN/RQS: This algorithm-based metric evaluates RNA integrity through analysis of the entire electrophoretic trace, incorporating the presence of ribosomal RNA peaks and degradation products. Scores range from 1 (completely degraded) to 10 (perfectly intact), with RIN ≥7 typically considered high-quality for standard RNA-seq applications [20]. The calculation employs a proprietary algorithm that considers various features of the electropherogram to generate an objective integrity measurement.

DV200: This metric calculates the percentage of RNA fragments exceeding 200 nucleotides in length, representing the fraction theoretically available for successful library preparation. Unlike RIN, DV200 does not depend on ribosomal peak ratios, making it particularly valuable for assessing FFPE-derived RNA where ribosomal peaks are often absent or altered [19] [21]. Related metrics include DV100 (fragments >100 nucleotides) which has shown particular utility for severely degraded FFPE samples [21].

Performance Characteristics Across Sample Types

Recent systematic comparisons reveal distinct performance advantages for each metric depending on sample preservation methods. For high-quality RNA from fresh-frozen specimens, RIN and DV200 show strong correlation and comparable predictive value for sequencing outcomes. However, for FFPE and other compromised samples, DV200 demonstrates superior performance in predicting library preparation efficiency and sequencing success [19]. One comprehensive study found that DV200 showed stronger correlation with the amount of NGS library product than RINe (R² = 0.8208 versus 0.6927), with receiver operating characteristic analysis confirming DV200's better predictive power for efficient library production [19].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of RNA Quality Metrics for Sequencing Applications

| Metric | Sample Type | Correlation with Library Yield | Optimal Cutoff Value | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RIN/RQS | Fresh-frozen | R² = 0.6927 [19] | >7 for standard protocols [4] | Comprehensive integrity assessment | Less reliable for degraded samples |

| DV200 | FFPE/Degraded | R² = 0.8208 [19] | >66.1% for library efficiency [19] | Independent of ribosomal peaks | May overestimate if cross-linked |

| DV200 | Fresh-frozen | Strong correlation | >70% for standard protocols [4] | Direct measure of usable fragments | Less informative about overall integrity |

| DV100 | Severely degraded FFPE | High predictive value [21] | >80% for gene detection [21] | Better for highly fragmented RNA | Less commonly reported |

Quantitative Relationships Between RNA Quality and Sequencing Parameters

RNA Quality Impact on Library Construction and Sequencing Depth

The integrity of input RNA directly influences library complexity and sequencing requirements through multiple mechanisms. High-quality RNA (RIN >8, DV200 >70%) generates libraries with greater diversity, enabling comprehensive transcriptome coverage at moderate sequencing depths. In contrast, degraded samples produce libraries with reduced complexity, requiring increased sequencing depth to detect the same number of genes [4]. Research demonstrates that for FFPE samples with DV200 values below 50%, increasing sequencing depth by 25-50% can partially compensate for reduced library complexity [4]. The relationship between RNA quality and usable sequencing depth follows a non-linear pattern, with significant reductions in effective depth occurring below specific quality thresholds.

Table 2: Sequencing Depth Recommendations Based on RNA Quality Metrics

| Application | RNA Quality | Recommended Depth | Read Length | Protocol Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Expression | RIN ≥8, DV200 >70% | 25-40 million PE reads [4] | 2×75 bp [4] [1] | Standard poly(A) enrichment |

| Differential Expression | DV200 30-50% | +25-50% more reads [4] | 2×75-2×100 bp [4] | rRNA depletion preferred |

| Isoform Detection | High quality (RIN ≥8) | ≥100 million PE reads [4] | 2×100 bp [4] | Stranded, paired-end designs |

| Isoform Detection | Moderate degradation | +25-50% above standard [4] | 2×100 bp [4] | rRNA depletion essential |

| Fusion Detection | DV200 >50% | 60-100 million PE reads [4] | 2×75-2×100 bp [4] | Paired-end required |

| FFPE (DV200 <30%) | Severely degraded | Avoid or sequence very deep [4] | 2×100 bp | Specialized protocols needed |

Evidence-Based Thresholds for Sequencing Success

ROC curve analyses have established specific quality metric thresholds predictive of successful library preparation. For the amount of 1st PCR product per input RNA (>10 ng/µl), the optimal cutoff values were determined to be RIN >2.3 and DV200 >66.1%, with DV200 demonstrating superior predictive power (AUC 0.99 vs. 0.91 for RIN) [19]. For FFPE samples specifically, a DV100 >80% provided the best indication of gene diversity and read counts upon sequencing [21]. These thresholds enable evidence-based sample triage decisions, minimizing resource waste on samples unlikely to yield meaningful data.

Experimental Protocols for RNA Quality Assessment and Sequencing

Standardized RNA Quality Control Protocol

Materials Required:

- Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 or TapeStation system with appropriate RNA screening kits

- Qubit Fluorometer with RNA HS Assay kit for accurate quantification [20]

- DNase treatment reagents (if not included in extraction kit)

- Nuclease-free water and consumables

Procedure:

- Extract RNA using methods appropriate for sample type (FFPE-specific kits for archived tissues)

- Treat with DNase to remove genomic DNA contamination (critical for accurate quantification) [20]

- Quantify RNA using fluorometric methods (Qubit) for accurate concentration measurement

- Assess integrity using Bioanalyzer/TapeStation electrophoresis systems

- Calculate RIN/RQS and DV200 values from electropherogram traces

- Based on quality metrics, determine suitability for sequencing and appropriate input amounts

For FFPE samples, include additional verification steps such as quantitative PCR to assess amplifiable RNA content, as this better reflects the functional quantity available for library preparation [21].

Library Preparation Strategies for Degraded RNA

Protocol selection must align with RNA quality to optimize outcomes:

For DV200 >50%:

- Standard poly(A) selection or rRNA depletion protocols can be employed

- Input amount: 10-100 ng total RNA depending on degradation level

- TruSeq RNA Access or similar kits designed for varying input quality [19]

For DV200 30-50%:

- rRNA depletion protocols are strongly recommended over poly(A) selection

- Increase RNA input by 1.5-2× to compensate for reduced usable fragments

- Incorporate unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to account for amplification bias [4]

- Consider specialized FFPE-optimized kits (Roche KAPA RNA HyperPrep with RiboErase) [20]

For DV200 <30%:

- rRNA depletion is essential; poly(A) selection will introduce severe 3' bias

- Maximum recommended RNA input (100-500 ng)

- UMIs are crucial for accurate quantification

- Expect significantly reduced library complexity and increased sequencing requirements [4] [20]

Decision Framework for Sequencing Depth Adjustment

The relationship between RNA quality and required sequencing depth follows predictable patterns that can be formalized into a decision framework. This framework enables researchers to systematically adjust sequencing parameters based on pre-sequence quality metrics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for RNA Quality Assessment and Sequencing

| Category | Product/Platform | Specific Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Quality Assessment | Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100/TapeStation | RIN/RQS and DV200 calculation | Microfluidics-based electrophoresis, standardized metrics |

| RNA Quantification | Qubit Fluorometer with RNA HS Assay | Accurate RNA quantification | RNA-specific fluorescence, minimal DNA/protein interference |

| FFPE RNA Extraction | Promega ReliaPrep FFPE Total RNA Kit | RNA from archived samples | Optimized for cross-link reversal, high yield/quality ratio [22] |

| FFPE RNA Extraction | Roche KAPA RNA HyperPrep with RiboErase | Degraded RNA library prep | Efficient rRNA depletion, compatible with low-quality inputs [20] |

| Library Preparation | Illumina TruSeq RNA Access | Degraded RNA sequencing | Designed for variable input quality, compatible with FFPE RNA [19] |

| NGS Platform | Illumina HiSeq 2500/3000/4000 | RNA-seq applications | 2×100 bp reads optimal for splice junction detection [20] |

RNA quality metrics, particularly DV200 for degraded samples, provide essential guidance for determining appropriate sequencing depth and methodology. The systematic integration of quality assessment into experimental design enables researchers to make evidence-based decisions about sample inclusion, library preparation strategies, and sequencing depth requirements. By aligning sequencing parameters with RNA quality, researchers can maximize data quality while optimizing resource allocation, particularly valuable when working with biobank samples and clinical specimens where quality varies substantially. As RNA-seq applications continue to expand in both basic research and clinical contexts, the rigorous application of these quality-informed sequencing strategies will ensure robust, reproducible, and biologically meaningful results.

Application-Specific Guidelines: Matching Sequencing Strategy to Your Biological Question

In the field of bulk RNA sequencing, researchers continually face the challenge of balancing data quality with budgetary constraints. The selection of appropriate sequencing depth represents a critical design parameter that directly influences both the scientific validity and practical feasibility of transcriptomic studies. As the technology has evolved from a discovery tool into a cornerstone of clinical and translational genomics, best practices have shifted from following a single recipe to making informed choices driven by specific study goals and sample quality [4]. Within this context, a consensus has emerged around a specific range of 25-40 million reads per sample as a cost-effective sweet spot for one of the most common applications in functional genomics: differential gene expression analysis.

This application note examines the technical justification, practical implementation, and economic rationale behind this optimal read depth, providing researchers with evidence-based protocols for designing robust and efficient RNA-seq experiments.

Establishing the Benchmark: The 25-40 Million Read Recommendation

Consensus Across Guidelines

Multiple independent sources from both academic and industry perspectives converge on the 25-40 million read range as optimal for standard differential expression analyses. This consensus spans consortium recommendations, core facility protocols, and manufacturer guidelines, creating a robust foundation for experimental design.

The ENCODE long-RNA data standards remain the most widely referenced public specification for bulk RNA-Seq, recommending sequencing depths of ≥30 million mapped reads for typical poly(A)-selected RNA-Seq [4]. This benchmark is further refined by technical reviews and manufacturer guidelines that specifically converge on 25–40 million paired-end reads per human sample as a sweet spot for robust gene quantification [4]. Core facilities at major research institutions have adopted similar standards, with Northwestern University's NUSeq core recommending 20-25 million reads per sample for general gene expression profiling [23].

Technical Rationale

The 25-40 million read range represents an optimization point where sequencing depth adequately captures the transcriptional landscape without generating redundant data. At this depth, fold-change estimates stabilize across expression quantiles without wasting reads on already-well-sampled transcripts [4]. This depth provides sufficient sampling to ensure that:

- Expression estimates stabilize for moderately to highly expressed genes

- Statistical power increases for detecting biologically meaningful differences

- Technical variability decreases through comprehensive transcript sampling

- Cost efficiency maximizes by avoiding diminishing returns of deeper sequencing

Sequencing Depth Recommendations by Research Application

The optimal sequencing depth varies substantially depending on the specific biological questions being addressed. The table below summarizes recommended read depths and configurations for common research applications in human studies:

Table 1: RNA-Seq Sequencing Recommendations by Research Application

| Research Application | Recommended Depth | Read Configuration | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Gene Expression | 25-40 million reads [4] [23] | PE 75 bp [4] | Cost-effective for robust gene quantification |

| Isoform Detection & Alternative Splicing | ≥100 million reads [4] | PE 100 bp [4] | Requires longer reads to span multiple exons |

| Fusion Gene Detection | 60-100 million reads [4] | PE 75-100 bp [4] | Higher depth needed for split-read support |

| Allele-Specific Expression | ~100 million reads [4] | Paired-end [4] | Essential for accurate variant allele frequency |

| Small RNA Sequencing | 4-5 million reads [23] | SE 50 bp [1] | Sufficient due to small transcriptome size |

| Total RNA-Seq (rRNA-depleted) | 20-25 million reads [23] | SE 50/75 bp or PE [23] | Similar to mRNA-seq for gene expression |

For differential expression studies specifically, the 25-40 million read recommendation applies particularly to high-quality RNA samples with RNA Integrity Number (RIN) ≥8 or DV200 >70% [4]. The selection of paired-end 75 bp reads provides the additional advantage of more accurate transcript mapping compared to single-end protocols, while remaining cost-effective [4] [23].

Economic Considerations in Experimental Design

Cost-Benefit Analysis of Sequencing Depth

The 25-40 million read recommendation emerges not only from technical considerations but also from economic practicality. Beyond approximately 40 million reads, experiments encounter diminishing returns where additional sequencing yields progressively fewer novel transcript discoveries [4]. As one benchmarking study demonstrated, the new detections rate (NDR) - the number of newly detected genes per million additional reads - drops significantly as sequencing depth increases [24].

Recent methodological advances have further refined the cost-benefit calculus. Early barcoding protocols such as Prime-seq demonstrate that library generation costs can be reduced by almost 50-fold compared to standard TruSeq preparations while maintaining equivalent performance for differential expression analysis [25]. Similarly, BRB-seq and related approaches achieve accurate gene expression quantification with only 5 million reads per sample through 3' mRNA-seq multiplexing, though with some trade-offs in isoform-level information [26].

The Critical Role of Biological Replication

A fundamental principle in experimental design is the prioritization of biological replication over excessive sequencing depth. Multiple studies have demonstrated that increasing replicate number provides greater statistical power for detecting differential expression than simply sequencing the same samples more deeply [27].

In toxicogenomics dose-response studies, increasing from 2 to 4 replicates significantly enhanced reproducibility, with over 550 genes consistently identified across most sequencing depths compared to high variability with only 2 replicates [27]. This principle holds particular importance for differential expression studies, where the power to detect true biological differences depends more on replicate number than on extreme sequencing depth.

Table 2: Cost Distribution for mRNA-seq Using Different Library Prep Methods

| Cost Component | Illumina TruSeq | NEBnext Ultra II | BRB-seq/QuantSeq |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction & QC | $6.3-$11.2 | $6.3-$11.2 | $6.3-$11.2 |

| Library Preparation | $68.7 | $41.3 | $24.0 |

| Sequencing (S4 Flow Cell) | $36.9 | $25.9 | $4.6 |

| Data Analysis | ~$2.0 | ~$2.0 | ~$2.0 |

| Total Cost Per Sample | ~$113.9 | ~$75.5 | ~$36.9 |

Sample Quality and Experimental Success

RNA Quality Metrics and Their Impact

RNA integrity represents perhaps the most critical factor influencing sequencing outcomes. The recommended 25-40 million read depth assumes high-quality RNA samples with the following characteristics:

- RNA Integrity Number (RIN) ≥8 or RQS ≥8 [4] [23]

- DV200 >70% [4]

- Absence of genomic DNA contamination [23]

For samples with compromised RNA quality, such as those from Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tissues, alternative approaches are necessary. The DV200 metric (percentage of RNA fragments >200 nucleotides) becomes particularly valuable for assessing degraded samples [4].

Adapting Protocols for Suboptimal Samples

When working with degraded or low-quality RNA, researchers should consider both protocol modifications and sequencing adjustments:

- DV200 30-50%: Increase sequencing depth by 25-50% and prefer rRNA depletion over poly(A) selection [4]

- DV200 <30%: Avoid poly(A) selection; use capture or rRNA depletion with higher input and ≥75-100 million reads [4]

- FFPE samples: Combine unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) with rRNA-depletion protocols and increase total reads by 20-40% [4]

- Limited input (≤10 ng RNA): Incorporate UMIs to collapse PCR duplicates and consider low-input specialized protocols [4]

Implementation Protocols and Workflow

Experimental Design Workflow

The following diagram outlines the key decision points in designing a cost-effective RNA-seq experiment for differential expression analysis:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bulk RNA-Seq

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Reagents | Isolation of high-quality total RNA | TRIzol (solvent-based), QIAgen RNeasy Kit (silica-based column) [26] |

| RNA Quality Assessment | Evaluate RNA integrity and quantity | Bioanalyzer RNA-6000-Nano chip (RIN generation) [26] [23] |

| Poly(A) Selection Beads | Enrichment for mRNA | Oligo(dT) magnetic beads [4] [23] |

| rRNA Depletion Reagents | Removal of ribosomal RNA (for total RNA-seq) | Ribosomal RNA subtraction kits [4] [23] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Construction of sequencing-ready libraries | TruSeq Stranded mRNA, NEBNext Ultra II, Prime-seq [4] [26] [25] |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Correction for PCR amplification bias | Random barcodes incorporated during reverse transcription [4] [25] |

| ERCC Spike-in Controls | Technical standards for quantification | Ambion ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix [12] |

The establishment of 25-40 million reads as a sweet spot for differential gene expression analysis represents a maturation point in bulk RNA-seq methodology. This optimized range balances technical robustness with economic practicality, enabling researchers to design studies with appropriate statistical power while maximizing resource utilization. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve and costs decrease further, the fundamental principles of matching sequencing strategy to biological questions and sample quality will remain paramount.

Future developments in early barcoding methods [25], molecular indexing, and multi-modal sequencing integration will continue to refine these recommendations, but the 25-40 million read benchmark serves as a validated starting point for experimental design in differential expression studies. By adhering to these evidence-based guidelines and prioritizing biological replication over excessive depth, researchers can generate statistically robust, reproducible, and interpretable transcriptomic data that advances scientific discovery.

In bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), the choice of sequencing depth is a fundamental determinant of data quality and biological insight. While standard gene expression profiling can be accomplished with moderate depth, comprehensive isoform detection and alternative splicing analysis present a significantly greater challenge. Alternative splicing, a key mechanism for proteomic diversity, allows a single gene to produce multiple distinct mRNA isoforms. It is prevalent in vertebrates, with an estimated 90% of human genes undergoing this process [28]. The accurate identification of these isoforms is essential for understanding cellular differentiation, organismal development, and the molecular basis of diseases, including cancer and neurological disorders [28].

The transition from gene-level to isoform-level analysis necessitates a substantial increase in sequencing depth. This application note establishes the technical basis for employing ≥100 million paired-end reads to achieve robust isoform detection, delineates specific experimental scenarios requiring this depth, and provides detailed protocols for researchers and drug development professionals operating within a bulk RNA-seq framework.

Sequencing Depth Requirements by Biological Application

The required sequencing depth is primarily dictated by the biological question. The following table summarizes the recommended read depths and lengths for key applications in human studies, based on recent community benchmarks and manufacturer guidelines [4] [1].

Table 1: RNA-Seq Sequencing Recommendations for Different Research Aims

| Research Aim | Recommended Depth (Mapped Reads) | Recommended Read Length | Key Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Gene Expression | 25 - 40 million [4] | 2x75 bp paired-end [4] | Cost-effective stabilization of fold-change estimates for highly expressed genes. |

| Isoform Detection & Alternative Splicing | ≥100 million [4] | 2x75 bp or 2x100 bp paired-end [4] | Ensures sufficient coverage to resolve low-abundance isoforms and splice junctions. |

| Fusion Gene Detection | 60 - 100 million [4] | 2x75 bp (2x100 bp optimal) [4] | Provides cleaner junction resolution and adequate split-read support for breakpoint anchoring. |

| Allele-Specific Expression (ASE) | ~100 million [4] | 2x75 bp paired-end [4] | Essential to accurately estimate variant allele frequencies and minimize sampling error. |

For isoform detection, conventional depths used for differential expression capture only a fraction of splice events [4]. Deeper sequencing (≥100 million reads) ensures that lowly expressed but biologically critical transcripts are sampled, enabling the construction of a complete and quantitative picture of the transcriptome's complexity.

Wet Lab Workflow: From Sample to Sequencer

A meticulous wet lab protocol is critical for successful high-depth isoform studies. The following workflow details the key steps from sample preparation to library qualification.

Sample Quality Assessment and Input

- RNA Integrity Measurement: Quantify RNA Integrity Number (RIN) or RNA Quality Score (RQS) using an instrument such as the Agilent Bioanalyzer. Acceptable threshold: RIN/RQS ≥ 8. Alternatively, use the DV200 metric (percentage of RNA fragments >200 nucleotides). Proceed with standard protocols if DV200 > 70% [4].

- Input RNA Mass: For high-quality RNA (RIN≥8, DV200>70%), use 100 ng - 1 µg of total RNA as input for library preparation. For degraded samples (e.g., FFPE), higher input (e.g., 200 ng - 500 ng) may be required to compensate for reduced intact RNA content [4] [8].

- gDNA Removal: Treat all RNA samples with DNase I to eliminate genomic DNA contamination, which can lead to false-positive intron retention calls [29].

Library Preparation Protocol

This protocol is optimized for stranded, paired-end libraries to preserve strand-of-origin information, which is crucial for accurate isoform annotation.

- RNA Selection: Perform poly(A) selection for mRNA enrichment if studying polyadenylated transcripts and RNA is high-quality (DV200 > 50%). For degraded samples (DV200 < 50%) or to capture non-polyadenylated RNA, use ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion kits [4].

- cDNA Synthesis: Generate double-stranded cDNA using reverse transcriptase and random hexamer primers, followed by second-strand synthesis. Avoid excessive PCR cycles to minimize duplication artifacts.

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate platform-specific sequencing adapters to the blunt-ended, A-tailed cDNA fragments.

- Library Amplification & Size Selection: Amplify the library with a limited-cycle PCR (e.g., 8-12 cycles). Perform a clean-up and size selection step (e.g., using SPRI beads) to remove adapter dimers and select for inserts of the desired length.

- Library QC: Quantify the final library using a fluorescence-based method (e.g., Qubit). Assess library size distribution and confirm the absence of primer dimers using a high-sensitivity DNA kit on the Agilent Bioanalyzer or TapeStation. Validate library molarity via qPCR compatible with your sequencing platform.

Incorporating Controls

- Spike-in Controls: Use synthetic RNA spike-ins (e.g., ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix). These controls serve as an internal standard for assessing technical performance, dynamic range, and quantification accuracy across samples [8] [12].

- Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): For studies with limited input (≤10 ng) or highly degraded RNA, use library protocols that incorporate UMIs. UMIs enable accurate correction for PCR duplicates, which is critical when sequencing deeply (>80M reads) to distinguish biological signal from technical artifact [4].

A Decision Framework for High-Depth Sequencing

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for determining when to deploy ≥100 million paired-end reads in your bulk RNA-seq experiment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Successful high-depth RNA-seq experiments rely on a suite of specialized reagents and computational tools.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Isoform Detection

| Category | Item | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sample QC | Bioanalyzer RNA Nano Kit | Assesses RNA Integrity (RIN) and sample quality. Critical for determining the appropriate library prep protocol. |

| Library Prep | Poly(A) Selection Beads | Enriches for polyadenylated mRNA. Use with high-quality RNA (RIN≥8). |

| rRNA Depletion Kit | Removes ribosomal RNA. Essential for degraded samples (FFPE) or for capturing non-polyA RNA. | |

| Stranded cDNA Synthesis Kit | Generates sequencing libraries that preserve strand information, crucial for accurate isoform annotation. | |

| Sequencing Controls | ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix | Synthetic RNA controls added to the sample pre-library prep. Used to monitor technical performance and normalize quantification. |

| Specialized Reagents | UMI Adapters | Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) are short random sequences ligated to each molecule pre-amplification, allowing for precise removal of PCR duplicates. |

| Computational Tools | IsoQuant [28] | A highly effective tool for isoform detection with long-read sequencing, also applicable for short-read data analysis. Excels in precision and sensitivity. |

| Bambu [28] | A machine learning-based tool for transcript discovery and quantification that demonstrates strong performance in benchmarks. | |

| StringTie2 [28] | A widely used and computationally efficient tool for transcript assembly and quantification from RNA-seq data. |

The strategic selection of sequencing depth is a cornerstone of effective bulk RNA-seq experimental design. For researchers aiming to move beyond gene-level expression and delve into the complex world of isoform diversity, alternative splicing, and allele-specific regulation, committing to ≥100 million paired-end reads is a necessary investment. This depth, coupled with robust laboratory protocols, careful sample quality control, and advanced computational tools, unlocks a higher-resolution view of the transcriptome. By adhering to these guidelines, scientists and drug developers can ensure their data possesses the complexity and precision required to uncover meaningful biological insights and advance therapeutic discovery.

This application note details experimental and computational protocols for detecting two critical molecular features in cancer and genetic research: fusion genes and allele-specific expression (ASE). The accurate identification of fusion gene breakpoints and the resolution of allelic imbalances from bulk RNA-Seq data present distinct challenges, with sequencing depth and library preparation choices being paramount. Framed within the broader context of establishing sequencing depth requirements for bulk RNA-Seq, this guide provides detailed methodologies, data standards, and bespoke workflows to empower researchers and drug development professionals in generating reliable, analytically valid results for these specific applications.

In the era of precision medicine, moving beyond standard gene expression profiling to a more nuanced analysis of the transcriptome is essential. The detection of fusion genes, hybrid genes formed from previously independent genes, is crucial for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic targeting [30]. Concurrently, allele-specific expression (ASE) analysis, which measures the relative expression of parental alleles, serves as a powerful tool for uncovering cis-regulatory variation that often eludes genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and standard differential expression analyses [31] [32].

The resolution required to detect these features—namely, the precise mapping of genomic breakpoints for fusions and the quantitative assessment of allelic ratios for ASE—imposes specific and demanding requirements on bulk RNA-Seq experimental design. A critical consideration is the inherent trade-off between sequencing depth and the number of biological replicates; studies have demonstrated that increasing replicate count from 2 to 6, even at a moderate depth of 10 million reads per sample, boosts statistical power more significantly than increasing depth from 10 million to 30 million reads with fewer replicates [2]. This note outlines tailored strategies that balance these factors to optimize the detection of fusion breakpoints and ASE variants.

Sequencing Depth and Experimental Design Requirements

Successful detection is contingent upon appropriate sequencing depth and library construction. The requirements differ based on the primary analytical goal.

Table 1: Recommended Sequencing Specifications for Detection Goals

| Detection Goal | Recommended Mapped Reads (Per Sample) | Key Considerations | Recommended Library Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fusion Genes (Basic DGE context) | 20 - 50 million [2] [1] | Sufficient for exon-to-exon fusion discovery in poly(A)+ data. | poly(A)+ or rRNA-depleted |

| Fusion Genes (Breakpoint Resolution) | 30 - 60 million [1] | Higher depth improves resolution of intronic and intergenic breakpoints from intronic reads. | rRNA-depleted (Total RNA) [33] |

| Allele-Specific Expression (ASE) | 30 million+ (aligned) [12] | Higher depth reduces noise in quantifying allelic ratios, especially for lowly expressed genes. | poly(A)+ or rRNA-depleted |

| Transcriptome Assembly & Novel Splice Variants | 100 - 200 million [1] | Extreme depth required for de novo reconstruction of complex transcripts. | Stranded, paired-end |

Beyond depth, other experimental parameters are critical:

- Read Length: For gene expression and fusion detection, 50-75 bp single-end reads may suffice. For novel transcript assembly and improved splice junction mapping, longer paired-end reads (e.g., 2x100 bp) are beneficial [1].

- Replicates: The ENCODE consortium mandates a minimum of two biological replicates, with a Spearman correlation of >0.9 between them for gene quantifications [12].

- RNA Integrity: A RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 8 is recommended for high-quality library preparation [34].

Protocol for Fusion Gene and Breakpoint Detection

Experimental Workflow and Reagents

The following workflow and toolkit are designed for the sensitive detection of fusion transcripts, including their precise genomic breakpoints, from patient tissue or cell line samples.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Fusion Detection

| Item | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Total RNA Isolation Kit | Purifies all RNA species, including pre-mRNA with intronic sequences. | RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) with DNase I treatment to remove genomic DNA [34]. |

| rRNA Depletion Reagents | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA, enriching for pre-mRNA and other non-coding RNAs. | Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep Kit, with Illumina Unique Dual (UD) indexes for sample multiplexing [33] [34]. |

| High-Output Sequencing Platform | Generates the required sequencing depth and read length. | Illumina NextSeq 2000 system (P3 flowcell) for 2x101 bp paired-end sequencing [34]. |

| Bioanalyzer / TapeStation | Assesses RNA quality and library fragment size. | Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 to confirm RIN > 8 [34]. |

Detailed Computational Analysis Protocol

The following steps correspond to the computational phase of the workflow above.

- RNA Sequencing Data Acquisition: Sequence libraries to a depth of 30-60 million paired-end reads per sample to ensure sufficient coverage for breakpoint resolution [1]. Data formats are typically demultiplexed FASTQ files.

- Pre-processing and Quality Control: Use tools like Trim Galore (wrapper for Cutadapt and FastQC) to remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases (Q-score < 30) and discard short reads (< 20 bp) [34]. This step is critical for clean data.

- Genome Alignment: Align high-quality reads to a reference genome using a splice-aware aligner such as STAR [12]. For fusion detection, it is vital that the alignment step is configured to output chimeric or split reads, which are the primary evidence of fusion events.

- Fusion Calling with Breakpoint Resolution: Employ specialized algorithms designed to detect fusion transcripts and their underlying genomic breakpoints.

- Dr. Disco: This algorithm is specifically highlighted for its ability to leverage intronic and intergenic reads from rRNA-depleted RNA-Seq data to identify exact genomic breakpoints, moving beyond simple exon-to-exon junctions [33]. It uses the entire reference genome as its search space.

- FindDNAFusion: A combinatorial pipeline that integrates multiple fusion-calling tools (e.g., JuLI, Factera) to improve detection accuracy to ~98% for genes with intronic bait probes [35]. It includes a blacklist for filtering common artifacts and criteria for selecting reportable fusions.

- Visualization and Validation: Manually inspect candidate fusions using integrated genome browsers. Crucially, all bioinformatic predictions, especially novel or complex rearrangements, must be validated by orthogonal methods such as Sanger sequencing, RT-PCR, or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) [30] [35].

Protocol for Allele-Specific Expression Analysis

Experimental Workflow and Reagents

This protocol focuses on detecting allelic imbalance from bulk RNA-Seq data, which acts as a proxy for cis-regulatory variation.

Detailed Computational Analysis Protocol

The following steps correspond to the computational phase of the ASE workflow.

- Sequencing and Alignment: Generate RNA-Seq data according to standard gene expression profiling recommendations (>30 million aligned reads) [12]. Align reads using the STAR aligner as part of a standardized Bulk RNA-seq pipeline (e.g., the ENCODE pipeline) [12].

- Variant Calling and Quality Control: Process the aligned BAM files using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) best practices for RNA-seq short variant discovery (SNPs and indels) [31]. This step identifies heterozygous sites within expressed regions.

- Allele-Specific Expression Quantification: Count the reads supporting each allele at heterozygous loci. Several tools are available for this step:

- ASEP: Utilizes a generalized linear mixed-effects model to detect ASE across a population of individuals, accounting for correlations of SNPs within the same gene [34].

- MBASED and GeneiASE: Perform ASE analysis at the gene level by aggregating evidence from multiple heterozygous SNPs within a single sample [34].

- Statistical Analysis and Interpretation:

- ASE Score Calculation: Represent ASE as the absolute deviation from the expected heterozygous biallelic frequency of 0.5. An ASE score threshold of 0.966 can be used to distinguish true heterozygous loci from sequencing artifacts when genotype data is available [31].

- Population-level Analysis: Identify genes with significant shared imbalance across a cohort. For example, in a dilated cardiomyopathy study, genes like ABLIM1, TNNT2, and AKAP13 showed imbalance in a large majority of samples, highlighting their potential regulatory role [31].

- Differential ASE (dASE): Compare allelic imbalance between phenotypically distinct groups (e.g., disease subtypes) using non-parametric tests like the Mann-Whitney U test to find cis-regulatory differences associated with specific phenotypes [31].

Integrating fusion and ASE analysis with genomic data provides a more comprehensive biological picture. For instance, identifying a fusion gene's genomic breakpoint via Dr. Disco [33] can be complemented by investigating whether it leads to allelic imbalances in nearby genes or itself via ASE analysis [31]. Furthermore, tools like FusionAI demonstrate the potential of deep learning to predict fusion breakpoints directly from DNA sequence, offering a new avenue for understanding the genomic context of breakage [36].

In conclusion, the resolution of fusion gene breakpoints and allelic imbalances demands a deliberate and informed approach to bulk RNA-Seq experimental design. Key to this is selecting the appropriate library type (rRNA-depleted for full breakpoint resolution) and committing to adequate sequencing depth (30-60 million reads) and biological replication. The protocols and standards detailed herein provide a robust framework for generating high-quality data capable of uncovering these critical molecular events, thereby advancing our understanding of cancer genetics, complex traits, and personalized therapeutic strategies.

Choosing Between Poly(A) Selection and rRNA Depletion Based on Sample Integrity and Goals

In bulk RNA-Seq experiments, the initial choice of library construction method is a critical determinant of success. The two primary strategies—Poly(A) selection and rRNA depletion—fundamentally shape the transcriptome you measure, influencing data quality, analytical possibilities, and biological conclusions [37]. This protocol provides a structured framework for selecting the optimal method based on sample integrity, organism, and research objectives, ensuring robust and interpretable results.

Core Principles and Method Comparison

Underlying Mechanisms

- Poly(A) Selection: This method uses oligo-dT primers or probes to hybridize and enrich for RNA molecules possessing a poly(A) tail. It specifically targets mature eukaryotic messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and many long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) with poly(A) tails, while excluding ribosomal RNA (rRNA), transfer RNA (tRNA), and other non-polyadenylated species [37] [38].

- rRNA Depletion (Ribo-Depletion): This method employs sequence-specific DNA probes that bind to cytosolic and mitochondrial ribosomal RNAs. The rRNA-probe hybrids are subsequently removed, typically via RNase H digestion or affinity capture. This retains both polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated RNAs, including pre-mRNAs, many lncRNAs, histone mRNAs, and some viral RNAs [37] [38].

Comparative Workflow and Data Output

The following diagram illustrates the procedural and outcome differences between the two methods.

Decision Framework and Guidelines

The choice between methods hinges on three primary filters: the organism, RNA integrity, and the biological question regarding which RNA species are of interest [37].

Method Selection Table

The table below summarizes key scenarios and the recommended library preparation method.

| Situation | Recommended Method | Rationale | Potential Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eukaryotic RNA, good integrity, coding-mRNA focus | Poly(A) Selection | Concentrates sequencing reads on exons of mature mRNAs, boosting statistical power for gene-level differential expression [37]. | Coverage skews strongly toward the 3' end as RNA integrity decreases; long transcripts may be undercounted [37]. |