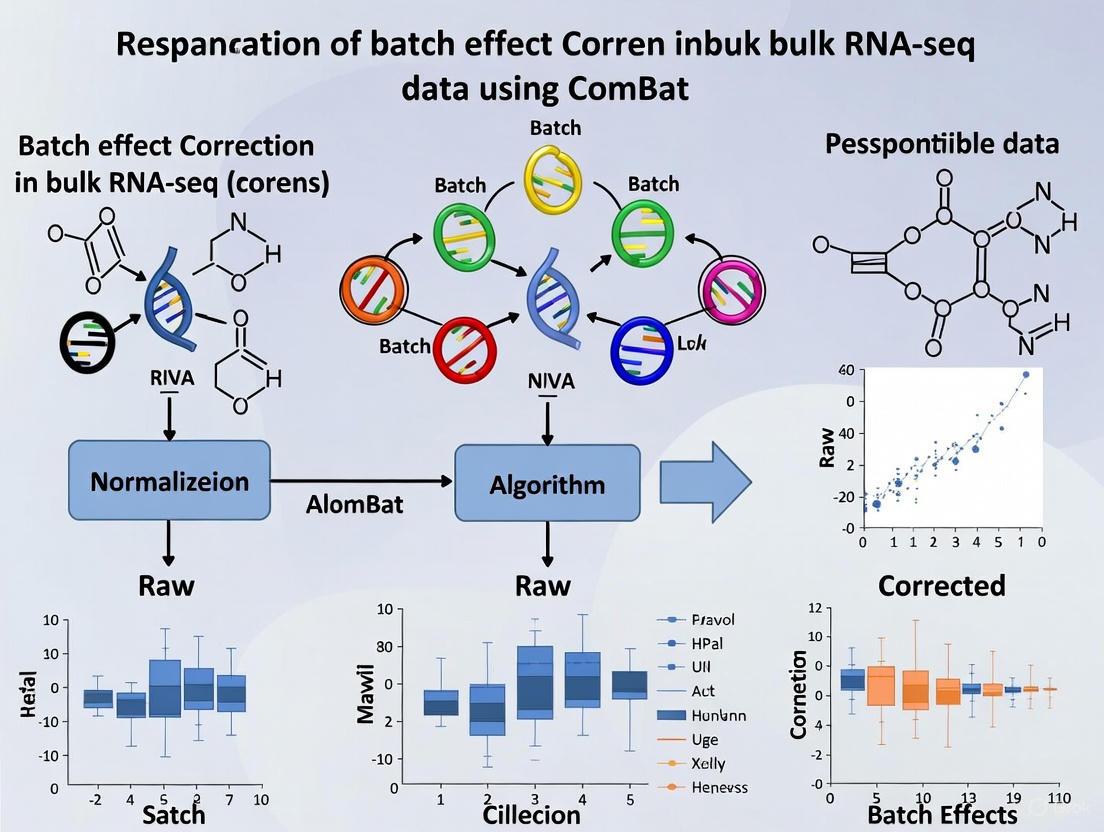

ComBat and Beyond: A Practical Guide to Batch Effect Correction in Bulk RNA-Seq

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and bioinformaticians on addressing batch effects in bulk RNA-sequencing data.

ComBat and Beyond: A Practical Guide to Batch Effect Correction in Bulk RNA-Seq

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and bioinformaticians on addressing batch effects in bulk RNA-sequencing data. It covers the foundational concepts of batch effects and their impact on differential expression analysis, explores the evolution and application of the ComBat family of methods—including the latest ComBat-ref algorithm—and offers best practices for implementation, troubleshooting, and validation. By comparing ComBat to other correction strategies and highlighting future directions, this guide aims to empower scientists to produce more reliable and reproducible transcriptomic insights, thereby accelerating drug discovery and biomedical research.

What Are Batch Effects and Why Do They Jeopardize Your RNA-Seq Analysis?

In the context of high-throughput genomic research, batch effects are defined as technical sources of variation that are introduced into data due to differences in experimental conditions and are unrelated to the biological factors of interest [1]. In RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) data, these non-biological variations arise from multiple technical sources during sample processing and sequencing across different batches, potentially confounding downstream analysis and leading to incorrect biological conclusions [2]. The profound impact of batch effects extends to increased data variability, reduced statistical power for detecting genuine biological signals, and in severe cases, completely misleading research outcomes that contribute to the reproducibility crisis in science [1]. One documented example illustrates how a change in RNA-extraction solution resulted in incorrect classification outcomes for 162 patients, 28 of whom subsequently received incorrect or unnecessary chemotherapy regimens [1]. As such, understanding, identifying, and correcting for batch effects constitutes a critical preprocessing step in bulk RNA-Seq analysis, particularly within research frameworks focusing on correction methods like ComBat.

Batch effects can originate at virtually every stage of a typical RNA-Seq workflow [1]. The fundamental cause can be partially attributed to fluctuations in the relationship between the actual abundance of an analyte and the instrument's measured intensity, breaking the assumption of a fixed, linear relationship across different experimental conditions [1]. Key sources include:

- Flawed or Confounded Study Design: Occurring during study design, this includes non-randomized sample collection or selection based on specific characteristics like age, gender, or clinical outcome, thereby confounding technical with biological variation [1].

- Sample Preparation and Storage: Variations in protocol procedures, such as differences in centrifugal forces during plasma separation, or variations in time and temperature prior to centrifugation, can cause significant changes in mRNA content [1].

- Sample Storage Conditions: Differences in storage temperature, duration, and the number of freeze-thaw cycles introduce substantial technical noise [1].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Disparities in reagents, personnel, laboratory environment, sequencing lanes, and the sequencing machines themselves are frequent culprits [2].

Profound Negative Impacts

The consequences of uncorrected batch effects are severe and multifaceted [1]:

- Misleading Conclusions: Batch effects can be erroneously identified as biologically significant findings, especially when batch and biological outcomes are highly correlated. In one notable case, purported cross-species differences between human and mouse were later attributed to batch effects related to data generation timepoints; after correction, data clustered by tissue type rather than species [1].

- Irreproducibility Crisis: Batch effects from reagent variability and experimental bias are identified as paramount factors contributing to irreproducibility in scientific research, potentially leading to retracted articles, discredited research findings, and significant financial losses [1].

- Reduced Statistical Power: In their most benign form, batch effects increase variability and dilute true biological signals, reducing the power to detect genuinely differentially expressed genes [1] [2].

Table 1: Documented Impacts of Batch Effects in Biomedical Research

| Impact Category | Consequence | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Misclassification | Incorrect patient stratification | Incorrect chemotherapy for 28 patients due to RNA-extraction solution change [1] |

| Species vs. Tissue Clustering | Biological misinterpretation | Human/mouse data clustered by species before correction, by tissue after correction [1] |

| Irreproducibility | Retracted publications, economic losses | Retraction of a serotonin biosensor study due to fetal bovine serum batch sensitivity [1] |

| Reduced Statistical Power | Failure to detect true positive effects | Decreased sensitivity in differential expression analysis [2] |

Detection and Visualization of Batch Effects

Experimental Design for Batch Effect Detection

Proactive experimental design is crucial for identifying and mitigating batch effects. While complete avoidance is ideal, certain strategies facilitate subsequent detection and correction:

- Balanced Design: Distributing samples from different biological conditions across all processing batches ensures that biological and technical variances are not confounded.

- Inclusion of Technical Replicates: Processing the same biological sample across different batches provides a direct measure of batch-associated technical variation.

- Randomization: The random assignment of samples to processing orders and sequencing runs minimizes systematic bias.

Visualization Techniques for Detection

Before correction, batch effects must be identified through both visual and quantitative means. The following visualization techniques are most commonly employed:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): A scatter plot of the top principal components (PCs) from the raw RNA-Seq data is examined. A strong separation of samples based on their batch (e.g., processing date) rather than biological condition in one of the early PCs is a classic indicator of a dominant batch effect [3].

- t-SNE/UMAP Plot Examination: In clustering analysis visualized on a t-SNE or UMAP plot, the presence of batch effects is indicated when cells or samples from the same biological group cluster separately based on their batch origin. Before correction, batches often form distinct, non-overlapping clusters; after successful correction, biological groups should coalesce regardless of batch [3].

Quantitative Metrics for Assessment

To complement visual inspection, quantitative metrics offer objective measures of batch effect strength and the efficacy of correction methods. These are calculated on the data distribution before and after batch correction [3]:

- k-nearest neighbor Batch Effect Test (kBET): Measures the local mixing of batches by testing whether the batch distribution in the k-nearest neighbors of each cell matches the global batch distribution.

- Adjusted Rand Index (ARI): Quantifies the similarity between two data clusterings, such as clustering results before and after integration.

- Normalized Mutual Information (NMI): Measures the mutual dependence between the clustering assignments and the batch labels.

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Batch Effect Assessment

| Metric | Principle of Operation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| kBET | Tests local batch distribution vs. global distribution | A higher p-value indicates better batch mixing. |

| Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) | Measures similarity between clusterings | Values closer to 1 indicate higher concordance. |

| Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) | Quantifies mutual dependence between cluster assignments and batch | Values closer to 0 indicate successful removal of batch information. |

| Percentage of Corrected Random Pairs (PCR_batch) | Assesses the proportion of correctly integrated sample pairs | Values closer to 1 indicate better integration. |

Batch Effect Correction: Focus on ComBat and Advanced Methods

The ComBat method, utilizing an empirical Bayes framework to correct for both location (additive) and scale (multiplicative) batch effects, has been a cornerstone in batch effect correction [2]. Its key advantage lies in its ability to stabilize the variance estimates for small sample sizes, which is common in genomic studies. Recognizing that RNA-Seq data consists of count data, ComBat-seq was developed. It employs a generalized linear model (GLM) with a negative binomial distribution, preserving the integer nature of the count data, which makes it more suitable for downstream differential expression analysis with tools like edgeR and DESeq2 [2].

A recent refinement, ComBat-ref, builds upon ComBat-seq but introduces a critical innovation: it selects the batch with the smallest dispersion as a reference batch and adjusts all other batches toward this reference [2]. This method models the RNA-seq count data using a negative binomial distribution, and the model for the expected gene expression level μ for a gene g in batch i and sample j is:

log(μ_ijg) = α_g + γ_ig + β_cjg + log(N_j)

Where:

- α_g is the global background expression of gene g.

- γ_ig is the effect of batch i.

- β_cjg is the effect of the biological condition c.

- N_j is the library size for sample j.

The adjustment for a non-reference batch is then performed by applying the difference between the reference batch effect and the non-reference batch effect: log(μ~_ijg) = log(μ_ijg) + (γ_reference_g - γ_ig) [2].

Detailed Protocol: Applying ComBat-ref for Batch Correction

Objective: To remove technical batch effects from a bulk RNA-Seq count matrix prior to differential expression analysis.

Input: A raw count matrix (genes x samples) with associated metadata specifying batch and biological group for each sample.

Software: R statistical environment with the ComBat-ref package/script and DESeq2/edgeR for downstream analysis.

Procedure:

Data Preparation and Import:

- Ensure data is in a non-normalized count format (e.g., outputs from featureCounts or HTSeq).

- Create a data frame for the sample metadata that clearly defines the

batchandcondition(biological group) for each sample.

Model Fitting and Dispersion Estimation:

- The ComBat-ref algorithm pools gene count data within each batch and estimates a batch-specific dispersion parameter (λ_i) for each gene using a GLM fit, typically implemented via edgeR [2].

Reference Batch Selection:

- The algorithm automatically identifies the batch with the smallest dispersion parameter (λ) as the reference batch. The assumption is that this batch has the least technical noise.

Data Adjustment:

- The count data for all samples in non-reference batches are adjusted toward the reference batch using the model described above. The adjustment ensures that the final output remains as integer counts, compatible with downstream DE tools.

Output and Downstream Analysis:

- The output is a corrected integer count matrix.

- This matrix can be directly used for differential expression analysis with standard tools like DESeq2 or edgeR, including the

batchcovariate in the design formula to account for any residual variation.

Performance and Comparison of Correction Methods

ComBat-ref has demonstrated superior performance in simulations, particularly when there is significant variance in dispersion parameters across batches. In benchmark studies, it maintained a high True Positive Rate (TPR) in detecting differentially expressed genes, comparable to data without batch effects, while controlling the False Positive Rate (FPR), especially when using the False Discovery Rate (FDR) for statistical testing with edgeR or DESeq2 [2].

Table 3: Comparison of Batch Effect Correction Methods for Bulk RNA-Seq

| Method | Core Model | Input/Output Data | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat | Empirical Bayes (Normal) | Normalized data | Effective for microarray & normalized RNA-Seq; handles small sample sizes. | Not designed for raw count data. |

| ComBat-seq | Empirical Bayes (Negative Binomial) | Raw count data → Integer counts | Preserves integer counts; better power for DE analysis than ComBat. | Performance can drop with highly variable batch dispersions. |

| ComBat-ref | Empirical Bayes (Negative Binomial with Reference) | Raw count data → Integer counts | Highest statistical power; robust to varying batch dispersions. | Relatively new method. |

| Include Batch as Covariate (e.g., in DESeq2) | Generalized Linear Model | Raw count data | Simple; directly integrates into DE pipeline. | Assumes additive effects; may not handle complex batch structures well. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful management of batch effects requires both wet-lab reagents and dry-lab computational tools.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Category | Item/Software | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Standardized RNA Extraction Kits (e.g., from Qiagen, Thermo Fisher) | Minimizes technical variation introduced during RNA isolation. |

| Library Preparation Kits (e.g., Illumina TruSeq) | Using the same kit and lot number across all samples reduces batch variability. | |

| RNA Spike-In Controls (e.g., ERCC) | Added to samples to monitor technical performance and identify batch effects. | |

| Quantification Assays (e.g., Qubit, Bioanalyzer) | Ensures accurate and consistent measurement of RNA and library quality. | |

| Computational Tools | FastQC/Falco & MultiQC | Performs initial quality control on FASTQ files and aggregates reports. |

| Alignment & Quantification (HISAT2, STAR, featureCounts) | Generates the raw count matrix from sequencing reads [4]. | |

| R/Bioconductor | Primary environment for statistical analysis and batch correction. | |

| DESeq2 / edgeR | Industry-standard packages for differential expression analysis. | |

| ComBat/ComBat-seq/ComBat-ref | Specialized packages for batch effect correction within the empirical Bayes framework [2]. | |

| sva package | Contains the ComBat functions and tools for surrogate variable analysis. |

Batch effects remain a formidable challenge in bulk RNA-Seq analysis, with the potential to severely compromise data interpretation and research reproducibility. A systematic approach involving careful experimental design, rigorous detection via visualization and quantitative metrics, and appropriate application of correction algorithms is paramount. The evolution of the ComBat method, from its original form to ComBat-seq and the recent ComBat-ref, highlights a trajectory of increasing sophistication in handling the specific characteristics of RNA-Seq count data. Integrating these correction protocols, particularly ComBat-ref, into a standard bulk RNA-Seq workflow ensures that biological conclusions are driven by genuine biology rather than obscured by systematic technical noise, thereby strengthening the foundation of transcriptomic research and its applications in drug development.

Batch effects are systematic technical variations introduced during the processing of biological samples across different times, locations, or experimental platforms. These non-biological variations represent a pervasive challenge in high-throughput omics studies, particularly in bulk RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data analysis. When unaddressed, batch effects can obscure true biological signals, reduce statistical power to detect differentially expressed (DE) genes, and ultimately lead to irreproducible and misleading scientific conclusions [1]. The consequences are far-reaching, with documented cases showing how batch effects have directly resulted in incorrect patient classifications and inappropriate treatment decisions in clinical settings [1]. In one prominent example, a change in RNA-extraction solution caused shifts in gene-based risk calculations, leading to incorrect classifications for 162 patients, 28 of whom subsequently received incorrect or unnecessary chemotherapy regimens [1].

The fundamental challenge stems from the basic assumption in quantitative omics profiling that instrument readouts linearly reflect biological analyte concentrations. In practice, fluctuations in this relationship across different experimental conditions create inevitable batch effects that compromise data reliability [1]. These effects manifest across all omics technologies, including transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, creating particular challenges for large-scale studies and multi-omics integration efforts [1] [5]. This application note examines the critical importance of batch effect correction, with a specific focus on ComBat-family methods for bulk RNA-seq data, and provides detailed protocols for implementing these approaches effectively.

The Impact of Batch Effects on Differential Expression Analysis

Consequences for Statistical Power and False Discoveries

Batch effects have profound implications for the analytical outcomes of differential expression studies. When batch effects are confounded with biological factors of interest, they can dramatically reduce the sensitivity to detect true differentially expressed genes while simultaneously increasing false discovery rates [2] [1]. This occurs because batch-induced variation introduces noise that obscures genuine biological signals, effectively diluting statistical power. In more severe cases, when batch effects correlate strongly with outcome variables, they can generate spurious associations that lead to completely false conclusions [1].

The magnitude of this problem becomes evident in simulation studies. When batch effects alter both the mean expression levels and dispersion parameters of count data, the true positive rate for DE detection can decrease substantially while false positive rates increase [2]. This dual threat makes batch effect correction not merely an optimization step but an essential component of rigorous bioinformatics analysis.

Quantitative Assessment of Batch Effect Impact

Table 1: Impact of Increasing Batch Effects on Differential Expression Analysis Performance

| Batch Effect Strength | Mean Fold Change | Dispersion Fold Change | True Positive Rate | False Positive Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 1.0 | 1.0 | 92.5% | 4.8% |

| Mild | 1.5 | 2.0 | 85.3% | 7.2% |

| Moderate | 2.0 | 3.0 | 72.1% | 12.5% |

| Severe | 2.4 | 4.0 | 58.7% | 21.3% |

Performance metrics derived from simulation studies demonstrate how increasing batch effect strength progressively degrades the reliability of differential expression analysis. Values are approximate and based on aggregated results from benchmark studies [2].

Method Categories and Underlying Principles

Batch effect correction algorithms can be broadly categorized into several classes based on their underlying statistical approaches. Location-scale (LS) methods, including ComBat, operate by matching the location (e.g., mean) and scale (e.g., standard deviation) of distributions across batches. Matrix factorization (MF) methods, such as SVA and RUV, identify directions of maximal variance associated with batch effects and remove these technical variations [6]. Reference-based methods leverage repeatedly measured samples or reference materials to estimate and correct batch effects [6] [5]. More recently, ratio-based approaches have gained prominence, particularly for challenging confounded scenarios where biological variables of interest completely align with batch variables [5].

The selection of an appropriate correction method depends on multiple factors, including study design, the severity of batch effects, and the level of confounding between batch and biological variables. No single method performs optimally across all scenarios, making it essential to understand the strengths and limitations of each approach [1].

The ComBat Family of Algorithms

ComBat represents one of the most established and widely-used methods for batch effect correction. Originally developed for microarray data, ComBat employs an empirical Bayes framework to correct for both additive and multiplicative batch effects [2]. The method estimates batch-specific parameters by borrowing information across genes, making it particularly effective for studies with small sample sizes per batch.

The ComBat approach has been extended specifically for RNA-seq count data through ComBat-seq, which uses a negative binomial generalized linear model to preserve the integer nature of count data while removing batch effects [2]. More recently, ComBat-ref has been introduced as a refined version that selects the batch with the smallest dispersion as a reference and adjusts other batches toward this reference, demonstrating superior performance in both simulated and real-world datasets [2].

Table 2: Comparison of ComBat-Family Methods for RNA-seq Data

| Method | Statistical Model | Data Type | Key Features | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat | Empirical Bayes with parametric priors | Continuous, normalized data | Borrows information across genes; stable for small batches | Normalized expression data (e.g., TPM, FPKM) |

| ComBat-seq | Negative binomial GLM | Count data | Preserves integer counts; avoids over-correction | Direct application to raw counts before DE analysis |

| ComBat-ref | Negative binomial with reference batch | Count data | Selects lowest-dispersion batch as reference; improves power | Batches with variable dispersion parameters |

ComBat-ref: Protocol for Batch Effect Correction in Bulk RNA-seq

ComBat-ref builds upon the ComBat-seq framework but introduces key innovations in reference batch selection and dispersion parameter handling. The method models RNA-seq count data using a negative binomial distribution, with each batch potentially having different dispersion parameters. Unlike ComBat-seq, which computes an average dispersion per gene across batches, ComBat-ref pools gene count data within each batch, estimates batch-specific dispersions, and selects the batch with the smallest dispersion as the reference [2].

The core model specification for ComBat-ref is as follows: For a gene g in batch i and sample j, the count nijg is modeled as:

nijg ~ NB(μijg, λig)

where μijg represents the expected expression level and λig is the dispersion parameter for batch i. The expected expression is modeled using a generalized linear model:

log(μijg) = αg + γig + βcjg + log(Nj)

where αg is the global background expression, γig is the batch effect, βcjg represents biological condition effects, and Nj is the library size [2].

Step-by-Step Implementation Protocol

Preprocessing and Data Preparation

Materials Required:

- RNA-seq Count Matrix: Raw read counts for genes (rows) across all samples (columns)

- Batch Information: Metadata specifying batch membership for each sample

- Biological Covariates: Experimental design factors of interest (e.g., treatment conditions)

- Computational Environment: R statistical environment with required packages

Procedure:

Data Input and Validation

Basic Quality Control and Filtering

Dispersion Estimation and Reference Batch Selection

ComBat-ref Implementation

Procedure:

Parameter Estimation

Quality Assessment of Correction

Differential Expression Analysis on Corrected Data

Performance Validation and Metrics

Procedure:

Batch Mixing Assessment

- Calculate principal components on corrected data

- Examine clustering of samples by batch in PCA space

- Compute intra-batch and inter-batch distances

Biological Signal Preservation

- Compare differentially expressed gene lists before and after correction

- Evaluate consistency with expected biological pathways

- Assess effect sizes for known condition-responsive genes

Statistical Power Evaluation

Advanced Applications and Integration Strategies

Handling Challenging Study Designs

Confounded Scenarios with Sample Remeasurement

In highly confounded case-control studies where biological effects are completely aligned with batch effects, specialized approaches like the ReMeasure method can be employed. This strategy utilizes a subset of remeasured samples across batches to estimate and correct for batch effects [6]. The implementation requires:

- Experimental Design: Select a subset of control samples for remeasurement in the case batch

- Model Fitting: Implement a linear mixed model that incorporates the correlation between original and remeasured samples

- Effect Estimation: Use maximum likelihood estimation to distinguish biological from technical effects

The performance of this approach depends strongly on the between-batch correlation, with higher correlations requiring fewer remeasured samples to achieve sufficient statistical power [6].

Reference Material-Based Approaches

For large-scale multi-omics studies, the ratio-based method using reference materials has demonstrated robust performance, particularly in completely confounded scenarios [5]. The protocol involves:

- Reference Material Selection: Choose appropriate reference samples (e.g., Quartet project reference materials)

- Concurrent Profiling: Process reference materials alongside study samples in each batch

- Ratio Calculation: Transform absolute feature values to ratios relative to reference measurements

This approach has shown superior performance compared to other methods like ComBat, SVA, and RUV when batch effects are strongly confounded with biological variables of interest [5].

Multi-Omic Data Integration

Batch effect correction becomes increasingly complex in multi-omics studies where different data types have distinct technical variations. A systematic evaluation of correction strategies for proteomics data found that protein-level correction generally outperforms precursor or peptide-level correction [7]. The recommended workflow includes:

- Protein Quantification: Generate protein-level abundance values using methods like MaxLFQ

- Batch Effect Assessment: Evaluate batch contributions using PCA and variance component analysis

- Correction Implementation: Apply ratio-based or ComBat correction at the protein level

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Effective Batch Effect Correction

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function in Batch Effect Management |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | Quartet multi-omics reference materials [5] | Provides stable benchmarks for ratio-based correction across batches |

| QC Samples | Universal human reference RNA, pooled plasma samples [7] | Monitors technical variation and enables normalization |

| Process Controls | Spike-in RNAs, labeled standard peptides [1] | Distinguishes technical from biological variation |

Troubleshooting and Optimization Guidelines

Common Challenges and Solutions

Over-correction and Signal Loss:

- Symptoms: Loss of known biological signal, reduced separation between conditions

- Diagnosis: Examine PCA plots before and after correction; assess known DE genes

- Solutions: Adjust ComBat-ref parameters; consider less aggressive correction methods; validate with positive controls

Incomplete Batch Effect Removal:

- Symptoms: Residual batch clustering in PCA, batch-associated covariates in DE results

- Diagnosis: Calculate batch effect metrics (e.g., PVCA, LISI)

- Solutions: Ensure proper model specification; include relevant covariates; consider interaction terms

Computational Limitations:

- Symptoms: Long run times, memory constraints with large datasets

- Solutions: Implement feature selection prior to correction; use approximate algorithms; increase computational resources

Performance Optimization Strategies

- Feature Selection: Pre-filter genes to include only highly variable genes, reducing dimensionality and improving correction efficiency

- Parameter Tuning: Optimize the empirical Bayes parameters through cross-validation

- Visualization Diagnostics: Implement comprehensive visualization (PCA, heatmaps, density plots) to assess correction quality

- Benchmarking: Compare multiple correction methods using both simulated and real datasets to select the optimal approach for specific data characteristics

Batch effect correction remains an essential step in bulk RNA-seq analysis, with ComBat-family methods providing robust solutions for diverse experimental scenarios. The recently developed ComBat-ref algorithm demonstrates particular promise for datasets with variable dispersion across batches, offering improved sensitivity and specificity in differential expression analysis [2]. As multi-omics studies continue to increase in scale and complexity, reference material-based approaches and ratio methods show increasing importance, especially for completely confounded scenarios where traditional methods fail [5].

The field continues to evolve with several promising directions. Integration of machine learning approaches, development of multi-omics specific correction strategies, and improved reference materials all represent active areas of research. Nevertheless, the foundation provided by established methods like ComBat and its refinements continues to offer reliable approaches for addressing the pervasive challenge of batch effects in biomedical research. Through careful implementation of these protocols and thoughtful consideration of experimental design, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability and reproducibility of their differential expression analyses.

Batch effects represent a significant challenge in bulk RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) experiments, introducing systematic non-biological variations that can compromise data reliability and obscure genuine biological signals [2]. These technical artifacts arise from various sources throughout the experimental workflow, from initial sample collection to final sequencing, and can substantially impact downstream differential expression analysis if not properly addressed. In the context of ComBat-based correction methodologies, understanding these sources is paramount for effective experimental design and subsequent batch effect mitigation. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of major batch effect sources, detailed protocols for their identification, and practical strategies for their minimization within the framework of ComBat-ref and related correction algorithms.

Library Preparation-Associated Variation

Library preparation introduces substantial technical variability through several key factors:

Table 1: Library Preparation Sources of Batch Effects

| Source | Impact on Data | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Input RNA Quantity | Minimal significant alteration to gene expression profiles [8] | Comparison of different input RNA quantities in primary B and CD4+ cells |

| Enrichment Method | Strong batch effect; different gene counts and coverage [9] [10] | PolyA vs. ribo-depletion methods show distinct clustering in PCA |

| Strand-Specificity | Affects anti-sense transcription detection [10] | Pico kit detected ~20% more genes with anti-sense signal than TruSeq |

| cDNA Library Storage | No significant impact on expression profiles [8] | Different storage times evaluated using primary blood cells |

| rRNA Depletion Efficiency | Varies by kit; affects usable reads [10] | Pico kit retained 40-50% ribosomal reads vs. ~7% for TruSeq |

The choice between polyA enrichment and ribosomal RNA depletion represents one of the most significant sources of batch effects during library preparation. These different enrichment methods yield substantially different profiles in gene expression counts and coverage patterns, creating strong batch effects that can confound downstream analysis [9]. Furthermore, strand-specificity capabilities vary across library prep kits, significantly impacting the detection of anti-sense transcription. In comparative studies, the Pico kit demonstrated approximately 20% greater sensitivity in identifying genes with anti-sense signal compared to TruSeq, highlighting how kit selection alone can introduce substantial variation [10].

Sequencing Run-Related Variation

Sequencing parameters and platform characteristics contribute significantly to batch effects:

Table 2: Sequencing Run Sources of Batch Effects

| Source | Impact on Data | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Flow Cell Lane Effects | Lane-to-lane technical variation | Demonstrated in multiplexed designs [11] |

| Read Depth | Affects low-expression gene detection [12] | >30M reads recommended for lowly-expressed genes |

| Read Length | Impacts isoform detection and alignment [12] | ≥50bp recommended for gene-level DE; longer for isoforms |

| Instrument Type | Platform-specific biases | Different platforms (Illumina, SOLiD, 454) show variation |

| Sequence Date | Inter-run technical variation | Samples processed at different times show systematic differences [13] |

Sequencing runs conducted on different days or using different flow cell lanes introduce systematic variations that manifest as batch effects. The concept of "batch" in this context can encompass any grouping of samples processed separately, including those sequenced in different lanes, on different flow cells, or on different instruments [13] [11]. These technical variations can be on a similar scale or even larger than the biological differences of interest, significantly reducing statistical power to detect genuinely differentially expressed genes [2].

Sample Processing and Origin Variation

Sample-specific factors introduce both biological and technical variability:

Sample Collection Time Points: Processing samples at different times introduces systematic variation, especially in large-scale studies that cannot process all samples simultaneously [14].

Reagent Lots: Different batches of reagents, including growth factors, enzymes, and purification kits, introduce measurable batch effects [12] [14].

RNA Extraction Methods: Variations in RNA extraction protocols or personnel performing extractions significantly impact RNA quality and introduce batch effects [12]. Were all RNA isolations performed on the same day? By the same person? If not, batches exist [12].

Cell Type and Preservation: Cryopreservation of cell samples versus fresh processing may introduce variation, though studies show minimal impact on expression profiles [8].

Sample Origin: Biological samples from different sources (e.g., primary tissue vs. organoids) exhibit substantial batch effects beyond technical variation [15].

Experimental Protocols for Batch Effect Detection

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for Batch Effect Detection

Purpose: To visually identify batch-driven clustering patterns in gene expression data.

Materials:

- Normalized count matrix (e.g., TMM, RLE)

- R statistical environment

- Metadata table with batch and condition information

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Load normalized count data and sample metadata

- PCA Calculation:

- Visualization and Interpretation:

Interpretation: Samples clustering primarily by technical factors (e.g., library method) rather than biological conditions indicate strong batch effects requiring correction [9].

Quality Metric-Based Batch Detection

Purpose: To identify batches using machine-learning-derived quality scores.

Materials:

- FASTQ files from RNA-seq experiment

- seqQscorer tool or similar quality assessment software [13]

- R environment for statistical testing

Procedure:

- Quality Score Calculation:

- Process each sample with seqQscorer to obtain Plow scores (probability of being low quality)

- Use maximum of 10 million reads per FASTQ file to reduce computation time

- Generate quality features from full files and subsets (1,000,000 reads)

Batch Effect Detection:

- Perform Kruskal-Wallis test to identify significant Plow score differences between batches

- Calculate designBias metric to assess correlation between Plow scores and sample groups

- Significance threshold: p-value < 0.05 indicates batch effect related to quality

Visualization:

- Create boxplots of Plow scores grouped by batch

- Generate PCA plots colored by Plow scores

- Evaluate clustering metrics (Gamma, Dunn1, WbRatio) before and after quality-based correction

Interpretation: Significant differences in quality scores between processing groups indicate quality-related batch effects. However, batch effects may also arise from sources unrelated to quality metrics [13].

Batch Effect Workflow and Relationships

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Their Functions in Batch Effect Management

| Reagent/Kits | Function | Batch Effect Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Spike-in Controls (e.g., SIRVs) | Internal standards for normalization | Enable technical variability assessment between batches [14] |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | Preserve RNA integrity during storage | Minimize degradation-induced variation across sample batches |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Remove ribosomal RNA | Kit-to-kit variability affects gene coverage; maintain consistent lot [10] |

| PolyA Selection Beads | Enrich for mRNA | Different batches may exhibit varying efficiency; test new lots |

| Library Prep Kits | cDNA synthesis and adapter ligation | Significant source of batch effects; use same kit and version [10] |

| Enzymes (Reverse Transcriptase, Polymerase) | cDNA synthesis and amplification | Lot-to-lot variability affects library complexity and duplication rates |

| Quantification Assays | Measure RNA and library quality | Critical for identifying quality-related batch effects [13] |

Integration with ComBat-ref Batch Correction

The sources of batch variation detailed above directly inform the application of ComBat-ref methodology. This refined batch effect correction method employs a negative binomial model specifically designed for RNA-seq count data and innovates by selecting a reference batch with the smallest dispersion, then adjusting other batches toward this reference [2]. Understanding the technical sources of variation enables researchers to:

- Define appropriate batches for ComBat-ref analysis based on library prep dates, sequencing runs, or reagent lots

- Preserve biological signal by distinguishing technical artifacts from genuine biological variation

- Improve differential expression detection by reducing false positives and increasing statistical power

ComBat-ref has demonstrated superior performance in both simulated environments and real-world datasets, including growth factor receptor network (GFRN) data and NASA GeneLab transcriptomic datasets, significantly improving sensitivity and specificity compared to existing methods [2]. By systematically addressing the sources of batch variation outlined in this application note and employing robust correction methods like ComBat-ref, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability and interpretability of their RNA-seq analyses.

In high-throughput genomic studies, such as bulk RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq), batch effects represent a significant challenge to data integrity and biological interpretation. These effects are defined as systematic non-biological variations between groups of samples (batches) that arise from experimental artifacts [16]. The sources of batch effects are numerous and can include factors such as processing time, reagent lots, laboratory personnel, sequencing platforms, and library preparation protocols [9] [13]. In the context of a broader thesis on batch effect correction using ComBat methodologies for bulk RNA-seq data, it is crucial to recognize that these technical variations can be on a similar scale or even larger than the biological differences of interest, potentially compromising the validity of downstream analyses and leading to false conclusions [2].

The critical importance of detecting and visualizing batch effects precedes any correction efforts. Without proper detection, researchers cannot determine the extent of technical variation present in their data, nor can they assess the effectiveness of any batch correction method applied, including ComBat-based approaches. Effective visualization serves as both a diagnostic tool for identifying unwanted variation and a validation metric for evaluating correction performance. This protocol focuses specifically on visualization techniques that enable researchers to detect and assess batch effects prior to applying computational correction methods like ComBat-ref, an advanced batch effect correction method that builds upon ComBat-seq by employing a negative binomial model and selecting a reference batch with the smallest dispersion for optimal adjustment of other batches [2].

Theoretical Foundation of Batch Effect Detection

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) Fundamentals

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a dimensionality-reduction technique that transforms potentially correlated variables into a smaller set of uncorrelated variables called principal components [17]. These components are linear combinations of the original variables that capture the maximum variance in the data, with the first principal component (PC1) representing the direction of highest variance, the second component (PC2) capturing the next highest variance under the constraint of being orthogonal to PC1, and so on [17]. When applied to gene expression data from RNA-seq experiments, PCA reduces the dimensionality from thousands of genes to a few principal components that can be visualized in two or three dimensions, allowing researchers to identify overarching patterns and structures in the data.

In the context of batch effect detection, PCA is particularly valuable because it reveals the major sources of variation in the dataset. When batch effects are present and represent a substantial source of variation, samples tend to cluster by batch rather than by biological condition in the PCA plot. This occurs because the systematic technical differences between batches manifest as coordinated changes in the expression of many genes, which PCA captures as dominant patterns of variance [9]. The interpretation of PCA results relies on examining the scatter plots of the first few principal components and observing whether the data points group according to known batch variables rather than the biological factors of interest.

Limitations of Standard PCA and Advanced Alternatives

While standard PCA (often called "unguided PCA") is widely used for batch effect detection, it has an important limitation: it will necessarily capture the largest sources of variation in the data, regardless of whether these are biologically relevant or technical in nature [16]. If batch effects are not the greatest source of variation, they may not be apparent in the first few principal components, leading to false confidence in the data quality. This limitation has prompted the development of more specialized approaches.

Guided PCA (gPCA) represents an advanced alternative specifically designed for batch effect detection [16]. Unlike standard PCA, which operates solely on the expression data matrix, gPCA incorporates a batch indicator matrix to guide the decomposition toward identifying variations associated with batch. This approach enables the calculation of a test statistic (δ) that quantifies the proportion of variance attributable to batch effects, complete with a statistical significance assessment through permutation testing [16]. The gPCA method thus provides both a visualization tool and a quantitative assessment of batch effects, addressing the limitations of standard PCA.

Table 1: Comparison of Visualization Methods for Batch Effect Detection

| Method | Key Principle | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard PCA | Identifies directions of maximum variance in expression data [17] | Intuitive visualization; Widely implemented; Fast computation | May miss batch effects that aren't the largest variance source; Subjective interpretation |

| Guided PCA (gPCA) | Uses batch indicator matrix to guide variance decomposition [16] | Provides statistical test for batch effects; More sensitive to batch-specific variance | Requires a priori knowledge of batches; Less familiar to many researchers |

| t-SNE/UMAP | Non-linear dimensionality reduction preserving local structure [18] | Can capture complex batch patterns; Effective for visualizing cluster separation | Computational intensity; Parameters sensitive; May overemphasize small differences |

| Hierarchical Clustering | Groups samples based on expression similarity across all genes [18] | Visualizes overall similarity patterns; Heatmap integration shows gene patterns | Difficult with many samples; Tree interpretation can be subjective |

| Machine Learning-Based Quality Assessment | Uses quality metrics predicted from sequence data to detect batches [13] | Can detect batches without prior annotation; Identifies quality-related batch effects | Requires quality prediction model; May miss quality-unrelated batch effects |

Experimental Protocols for Batch Effect Visualization

Sample Preparation and Experimental Design

The foundation for reliable batch effect detection begins with proper experimental design. To enable effective batch effect visualization and subsequent correction, studies must incorporate balanced design where each biological condition is represented across multiple batches [9]. This design is crucial because it allows statistical methods to distinguish between biological effects and technical artifacts. For example, if all samples from one biological condition are processed in a single batch while samples from another condition are processed in a different batch, it becomes impossible to determine whether observed differences are truly biological or merely technical in origin.

Researchers should meticulously document all potential sources of batch variation, including but not limited to: library preparation dates, sequencing lanes, reagent lots, personnel involved, and instrument calibration records. This documentation creates the necessary metadata for interpreting visualization results and for performing batch correction procedures. Additionally, the inclusion of technical replicates across different batches and control samples that are consistent across batches can significantly enhance the ability to detect and quantify batch effects [13]. When preparing samples for RNA-seq analysis that will subsequently undergo ComBat-based correction, it is essential to ensure that the experimental design includes at least some representation of each biological condition in every batch, as ComBat and similar methods cannot correct for batch effects when batches are completely confounded with biological conditions [9].

Protocol 1: PCA-Based Batch Effect Detection

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for detecting batch effects using principal component analysis of RNA-seq data, with specific examples implemented in R.

Data Preprocessing and Normalization

Begin with raw count data from RNA-seq experiments. For bulk RNA-seq data intended for ComBat-related analyses, follow these preprocessing steps:

PCA Computation and Visualization

After normalization, perform PCA and create visualization plots:

Interpretation Guidelines

When analyzing the resulting PCA plot, examine the following aspects:

Batch Clustering: If samples cluster primarily by batch rather than biological condition, this indicates strong batch effects. For example, if all ribo-depleted samples separate from polyA-enriched samples along PC1, this suggests library preparation method is a major source of variation [9].

Variance Explained: Check the percentage of variance explained by the first two principal components. If the batch-associated components capture a substantial portion of the total variance (e.g., >20%), batch effects are likely significant.

Condition Separation Within Batches: Ideally, biological conditions should separate consistently within each batch. If condition separation occurs in different directions across batches, this indicates batch-condition interactions that are particularly problematic for downstream analysis.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for PCA-based batch effect detection:

Figure 1: Logical workflow for PCA-based batch effect detection

Protocol 2: Guided PCA for Statistical Batch Effect Detection

For a more rigorous, statistically grounded approach to batch effect detection, guided PCA (gPCA) provides a quantitative alternative to standard PCA visualization.

Implementation of gPCA

The gPCA method can be implemented using the gPCA R package available via CRAN [16]:

Interpretation of gPCA Results

The gPCA method produces a test statistic δ that represents the proportion of variance due to batch effects in the experimental data. Large values of δ (values near 1) indicate that batch effects account for most of the variation captured by the first principal component [16]. The associated p-value, obtained through permutation testing, indicates whether the observed batch effect is statistically significant. A significant p-value (typically < 0.05) provides evidence that batch effects are present beyond what would be expected by chance alone.

Protocol 3: Complementary Visualization Methods

While PCA is highly valuable for batch effect detection, supplementary visualization approaches provide additional perspectives and can confirm findings from PCA analysis.

t-SNE and UMAP Visualizations

t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) are non-linear dimensionality reduction techniques that can sometimes reveal batch effects that PCA might miss:

When using t-SNE or UMAP, the same principle applies: if samples cluster primarily by batch rather than biological condition, batch effects are likely present. These methods are particularly sensitive to local structures in the data and can sometimes reveal subtle batch effects that linear methods like PCA might not capture [18].

Hierarchical Clustering and Heatmaps

Hierarchical clustering provides another visualization approach for detecting batch effects:

In the resulting dendrogram, if samples primarily cluster by batch rather than biological condition, this indicates substantial batch effects. This method visualizes the overall similarity between samples based on their complete expression profiles, providing a complementary view to PCA [18].

Quantitative Assessment of Visualization Results

Metrics for Batch Effect Severity

To move beyond qualitative visual assessment, researchers can employ quantitative metrics to evaluate the severity of batch effects detected through visualization methods. These metrics provide objective measures to compare batch effects across datasets and to assess the effectiveness of correction methods.

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Assessing Batch Effect Severity

| Metric | Calculation Method | Interpretation | Threshold Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| gPCA δ Statistic | Proportion of variance due to batch from guided PCA [16] | Higher values indicate stronger batch effects | δ > 0.3 suggests substantial batch effects |

| Percentage Variance Explained | Variance in PC1 or PC2 attributed to batch | Higher percentage indicates stronger batch influence | >20% variance in batch-associated PC indicates significant batch effect |

| Cluster Separation Metrics | Silhouette width, Dunn index, or Gamma statistic comparing batch vs condition separation [13] | Higher values for batch separation indicate stronger batch effects | Batch silhouette width > condition silhouette width indicates problematic batch effects |

| Differential Expression by Batch | Number of genes differentially expressed between batches without biological reason | Higher numbers indicate stronger batch effects | >100 DEGs between batches suggests substantial batch effect |

Case Study: Batch Effect Visualization in Practice

A practical example from a publicly available RNA-seq dataset (GSE163214) demonstrates the application of these visualization techniques. In this dataset, initial PCA visualization showed clear separation by batch, with samples from batch 1 clustering separately from samples from batch 2 along the first principal component [13]. This visual assessment was supported by poor clustering evaluation scores (Gamma = 0.09, Dunn1 = 0.01) and very few differentially expressed genes between biological conditions (DEGs = 4), indicating that batch effects were obscuring the biological signal.

After applying batch correction methods, the PCA plot showed improved clustering by biological condition rather than batch, with corresponding improvements in clustering metrics (Gamma = 0.32, Dunn1 = 0.17) and an increase in differentially expressed genes between true biological conditions (DEGs = 12-21) [13]. This case study illustrates how visualization methods serve both to identify batch effects and to validate the success of correction procedures.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Batch Effect Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| sva Package (R/Bioconductor) | Contains ComBat-seq for batch correction and surrogate variable analysis for batch effect detection [13] | Bulk RNA-seq data analysis | Available via Bioconductor; requires known batch information |

| gPCA Package (R) | Implements guided PCA with statistical test for batch effects [16] | Statistical detection of batch effects in high-throughput data | Available via CRAN; provides δ statistic and p-value |

| edgeR | Provides TMM normalization and data preprocessing for RNA-seq data [9] | Preparing RNA-seq count data for batch effect visualization | Available via Bioconductor; used for normalization before PCA |

| ggplot2 | Creates publication-quality visualizations of PCA and other plots [9] | All visualization needs for batch effect assessment | Available via CRAN; flexible plotting system for R |

| Harmony | High-performing batch integration method that can visualize corrected space [19] | Complex batch effect scenarios across multiple batches | Available for R and Python; useful for multi-batch studies |

| Seurat RPCA | Reciprocal PCA method effective for batch correction visualization [19] | Large datasets with substantial technical variation | Available for R; handles heterogeneous datasets well |

Integration with ComBat-Based Batch Effect Correction

Connecting Visualization to Correction

The visualization methods described in this protocol play a crucial role in the broader context of ComBat-based batch effect correction for bulk RNA-seq data. Effective visualization enables researchers to make informed decisions at multiple stages of the analysis pipeline:

Pre-Correction Assessment: Before applying ComBat-ref or similar methods, visualization determines whether batch correction is necessary and which batches require adjustment.

Method Selection: The pattern of batch effects observed in visualizations can inform the choice of correction method. For instance, when batches show differential dispersion (varying levels of technical variability), ComBat-ref specifically addresses this by selecting the batch with the smallest dispersion as a reference when adjusting other batches [2].

Post-Correction Validation: After applying batch correction methods, the same visualization techniques are used to verify that batch effects have been successfully mitigated without removing biological signals of interest.

The relationship between batch effect visualization and correction methodologies is illustrated in the following workflow:

Figure 2: Integrated workflow combining batch effect visualization and correction

Avoiding Over-Correction and Preserving Biological Signal

A critical consideration when integrating visualization with batch correction is the risk of over-correction, where biological signals are inadvertently removed along with technical artifacts [18]. Visualization methods provide essential safeguards against this problem by enabling researchers to verify that biological patterns remain after correction. Signs of over-correction include:

- Distinct cell types or conditions clustering together after correction when they were separate before correction

- Complete overlap of samples from very different biological conditions that should show some separation

- Loss of biologically meaningful differentially expressed genes in downstream analysis

To minimize over-correction risks, researchers should always compare pre-correction and post-correction visualizations, ensuring that biologically expected patterns are maintained while technical batch effects are reduced. ComBat-ref specifically addresses some of these concerns by preserving the count data for the reference batch and adjusting other batches toward this reference, maintaining greater fidelity to the original biological signals [2].

Effective visualization of batch effects using PCA and complementary methods forms an essential foundation for reliable bulk RNA-seq analysis, particularly in the context of ComBat-based correction methodologies. The protocols outlined in this document provide researchers with comprehensive approaches for detecting, quantifying, and visualizing unwanted technical variation in their data. By implementing these visualization techniques as routine components of the analytical pipeline, researchers can make informed decisions about when and how to apply batch correction methods like ComBat-ref, validate the effectiveness of these corrections, and ultimately ensure that their biological conclusions are supported by robust data rather than confounded by technical artifacts. As batch effect correction methodologies continue to evolve, with advanced approaches like ComBat-ref demonstrating superior performance in maintaining statistical power for differential expression analysis [2], the importance of effective visualization will only increase, enabling researchers to fully leverage the potential of high-throughput genomic data while minimizing the impact of technical artifacts.

Implementing ComBat: From Classic Algorithms to Cutting-Edge Refinements

In genomic research, batch effects introduce systematic technical variations that can compromise data integrity and lead to erroneous biological conclusions. These non-biological variations arise from differences in experimental conditions, processing times, reagent lots, sequencing platforms, or laboratory personnel [9]. When combining datasets from different batches for analysis, these effects can create heterogeneity that obscures true biological signals and reduces statistical power in downstream analyses [2]. While normalization methods can address overall distributional differences between samples, they often fail to correct for compositional batch effects at the individual gene level [9].

The Empirical Bayes framework provides a powerful statistical approach for batch effect correction by leveraging information across all genes to improve parameter estimates, even when sample sizes within batches are small. This approach allows for robust adjustment of batch effects while preserving biological signals of interest. Two prominent methods employing this framework are ComBat and ComBat-seq, each designed for specific data types and analytical needs [20] [21].

ComBat was originally developed for microarray data and assumes a continuous, log-normal distribution of expression values. It has since been widely adopted across various genomic data types. ComBat-seq represents a specialized adaptation for RNA-seq count data, which follows a negative binomial distribution, thereby preserving the integer nature of sequencing counts throughout the correction process [21]. This distinction is crucial because applying methods designed for continuous data to discrete count data can introduce biases and reduce power in downstream differential expression analyses [2].

Theoretical Foundations and Methodological Evolution

Core Mathematical Framework

The Empirical Bayes approach implemented in both ComBat and ComBat-seq operates by pooling information across features (genes) to improve parameter estimation for individual features. This is particularly valuable when dealing with small sample sizes, where per-gene estimates would be unstable. The method estimates batch-specific parameters through an empirical Bayes shrinkage approach, then removes these technical artifacts while preserving biological variability.

ComBat employs a location and scale adjustment model that accounts for both additive and multiplicative batch effects. For a given gene g in batch i, the model assumes: [ Y{ig} = \alphag + \gamma{ig} + \delta{ig} \varepsilon{ig} ] where (Y{ig}) represents the expression value, (\alphag) is the overall gene expression, (\gamma{ig}) and (\delta{ig}) are the additive and multiplicative batch effects, and (\varepsilon{ig}) represents the error term. The Empirical Bayes approach estimates the batch effect parameters by pooling information across all genes, then applies these estimates to adjust the expression values [20] [21].

ComBat-seq modifies this framework specifically for count-based data by using a negative binomial regression model: [ n{ijg} \sim NB(\mu{ijg}, \lambda{ig}) ] where (n{ijg}) represents the count for gene g in sample j from batch i, (\mu{ijg}) is the expected expression level, and (\lambda{ig}) is the dispersion parameter for batch i [2]. This model better captures the mean-variance relationship typical of RNA-seq data and preserves the integer nature of counts after adjustment, making it more suitable for downstream analyses with tools like edgeR and DESeq2.

Evolution to Reference-Based Methods

Recent methodological advances have introduced reference batch approaches that further enhance the Empirical Bayes framework. ComBat-ref represents one such evolution, building upon ComBat-seq's negative binomial model but incorporating a strategic selection of a reference batch with the smallest dispersion [2] [22]. This approach preserves the count data for the reference batch while adjusting other batches toward this reference, improving statistical power in differential expression analysis.

The model in ComBat-ref estimates parameters through a generalized linear model: [ \log(\mu{ijg}) = \alphag + \gamma{ig} + \beta{cj g} + \log(Nj) ] where (\beta{cj g}) represents the effects of biological condition (cj) on gene *g*'s expression, and (Nj) is the library size for sample j [2]. For adjustment, the method computes: [ \log(\tilde{\mu}{ijg}) = \log(\mu{ijg}) + \gamma{1g} - \gamma{ig} ] where batch 1 is the reference batch with the smallest dispersion. This approach maintains high statistical power even when significant variance exists between batch dispersions [2].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

ComBat-seq Standard Protocol

The following protocol describes a standard workflow for applying ComBat-seq to RNA-seq count data, with execution possible in either R or Python environments.

Materials and Software Requirements

- RNA-seq count matrix: Raw read counts (integer values) for genes across all samples

- Batch information: Categorical variable specifying batch membership for each sample

- Biological covariates: Optional model matrix for biological conditions of interest

- Computational environment: R (with sva package) or Python (with inmoose/pyComBat package)

- Memory resources: Sufficient RAM to handle the size of the count matrix

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Preparation and Input

- Format count data as a matrix with genes as rows and samples as columns

- Ensure count data consists of integers (raw counts rather than normalized values)

- Create a batch vector specifying batch membership for each sample

- Optional: Create a model matrix for biological conditions to preserve during correction

Parameter Configuration

- For R implementation: Use

ComBat_seq()function from the sva package - For Python implementation: Use

pycombat_seq()function from the inmoose package - Set

shrinkparameter to TRUE for Empirical Bayes shrinkage (recommended for small sample sizes) - Set

shrink.dispparameter to TRUE to shrink dispersion estimates

- For R implementation: Use

Execution and Output

- Run ComBat-seq with the count matrix, batch vector, and optional model matrix

- The function returns an adjusted count matrix with the same dimensions as the input

- Adjusted counts remain as integers, suitable for downstream differential expression analysis

Reference Batch Protocol (ComBat-ref)

The ComBat-ref protocol extends ComBat-seq with a reference batch approach that enhances performance when batch dispersions vary significantly.

Additional Requirements

- Dispersion estimation: Method to estimate dispersion parameters for each batch

- Reference batch selection: Criteria for selecting the batch with smallest dispersion

Procedure

Dispersion Estimation and Reference Selection

- Estimate dispersion parameters for each batch using edgeR or DESeq2

- Calculate median dispersion values for each batch across all genes

- Select the batch with the smallest median dispersion as the reference batch

Model Fitting and Adjustment

- Fit a negative binomial generalized linear model (GLM) to the count data

- Include batch and biological condition terms in the model

- Adjust non-reference batches toward the reference batch using the formula: [ \log(\tilde{\mu}{ijg}) = \log(\mu{ijg}) + \gamma{1g} - \gamma{ig} ]

- Set adjusted dispersions to the reference batch values ((\tilde{\lambda}i = \lambda1))

Count Adjustment and Validation

- Calculate adjusted counts by matching cumulative distribution functions

- Ensure zero counts remain zeros after adjustment

- Validate correction effectiveness through PCA visualization and clustering metrics

Performance Comparison and Evaluation

Method Performance Across Experimental Conditions

Extensive evaluations have been conducted to assess the performance of ComBat, ComBat-seq, and related methods across various data types and batch effect scenarios. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from published comparative studies.

Table 1: Performance comparison of batch correction methods

| Method | Data Type | Preserves Biological Signal | Batch Effect Removal | Computational Efficiency | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat | Microarray, normalized data | Moderate | Effective for location effects | High | Not ideal for count data |

| ComBat-seq | RNA-seq count data | Good | Effective for composition effects | Moderate | Reduced power with dispersion differences |

| ComBat-ref | RNA-seq count data | Excellent | Effective with reference batch | Moderate | Requires sufficient samples per batch |

| Harmony | scRNA-seq, embeddings | Excellent [23] | Effective with cell type differences | High | Does not modify count matrix directly |

| BBKNN | scRNA-seq, k-NN graph | Moderate [23] | Varies with data structure | High | Only corrects neighborhood graph |

Quantitative Assessment in Simulation Studies

Simulation studies provide controlled environments to evaluate batch correction methods by introducing known batch effects and measuring correction effectiveness. The following table summarizes results from a comprehensive simulation comparing ComBat-seq and ComBat-ref under varying batch effect intensities.

Table 2: Performance metrics of ComBat methods in simulation studies

| Method | Batch Effect Strength | True Positive Rate | False Positive Rate | Statistical Power | FDR Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat-seq | Low (meanFC=1.5, dispFC=1) | 0.89 | 0.05 | High | Adequate |

| ComBat-seq | High (meanFC=2.4, dispFC=4) | 0.72 | 0.06 | Moderate | Adequate |

| ComBat-ref | Low (meanFC=1.5, dispFC=1) | 0.91 | 0.04 | High | Good |

| ComBat-ref | High (meanFC=2.4, dispFC=4) | 0.88 | 0.05 | High | Good |

Data adapted from ComBat-ref validation studies [2]. Performance metrics represent average values across 10 simulation replicates with 500 genes (100 differentially expressed). ComBat-ref demonstrates superior maintenance of true positive rates even under strong batch effects with differential dispersion across batches.

Real-World Data Applications

In addition to simulation studies, both ComBat-seq and ComBat-ref have been validated on real-world datasets. In the Growth Factor Receptor Network (GFRN) data and NASA GeneLab transcriptomic datasets, ComBat-ref demonstrated significantly improved sensitivity and specificity compared to existing methods [2]. Similarly, evaluations on multi-platform sequencing data comparing ribosomal reduction and polyA-enrichment protocols showed that ComBat-seq effectively corrected technical batch effects while preserving biological differences between Universal Human Reference (UHR) and Human Brain Reference (HBR) samples [9].

Implementation and Computational Considerations

Software Implementations

The ComBat methods are available through multiple software implementations, each with specific advantages for different computational environments.

Table 3: Software implementations of ComBat methods

| Implementation | Language | Functions | Key Features | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sva | R | ComBat(), ComBat_seq() | Reference implementation, comprehensive options | Standard |

| pyComBat | Python | pycombatnorm(), pycombatseq() | Same mathematical framework, 4-5x faster than R [21] | High |

| Scanpy | Python | combat() | Integrated with single-cell analysis workflow | Moderate |

| inmoose | Python | pycombatnorm(), pycombatseq() | Open-source, GPL-3.0 license | High |

Successful application of ComBat methods requires both experimental reagents and computational resources. The following table outlines key components of the batch correction toolkit.

Table 4: Essential research reagents and computational tools for ComBat analysis

| Category | Item | Specification | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | RNA extraction kits | High-quality, minimal degradation | Ensure high-quality input material |

| Library preparation kits | Consistent lots across batches | Minimize technical variation | |

| Sequencing controls | Spike-in RNAs, ERCC controls | Monitor technical performance | |

| Computational Tools | Quality assessment | FastQC, MultiQC | Evaluate read quality across batches |

| Alignment software | STAR, HISAT2 | Consistent mapping across samples | |

| Count quantification | featureCounts, HTSeq | Generate count matrices for analysis | |

| Statistical environment | R (4.0+), Python (3.6+) | Implement ComBat functions | |

| Batch correction | sva, pyComBat | Perform empirical Bayes correction | |

| Validation Resources | Positive control genes | Housekeeping genes, known markers | Verify biological signal preservation |

| Negative control genes | Non-differentially expressed genes | Assess over-correction |

Advanced Applications and Integration with Downstream Analyses

Integration with Differential Expression Analysis

The primary application of ComBat-seq and ComBat-ref is preprocessing RNA-seq count data prior to differential expression (DE) analysis. When properly applied, these methods can significantly improve the sensitivity and specificity of DE detection by removing technical artifacts that would otherwise confound biological comparisons [2]. The integer output of ComBat-seq makes it particularly compatible with DE tools like edgeR and DESeq2, which are optimized for count data.

The workflow typically involves:

- Raw count collection from alignment and quantification tools

- Filtering to remove lowly expressed genes

- Batch correction using ComBat-seq or ComBat-ref

- Differential expression analysis using standard count-based methods

This integrated approach has demonstrated comparable performance to batch-free data in simulation studies, even when significant variance exists between batch dispersions [2].

Application in Multi-Study Meta-Analyses

ComBat methods are particularly valuable in meta-analyses that combine datasets from multiple studies, laboratories, or experimental platforms. In such scenarios, batch effects can be substantial due to differences in protocols, reagents, and sequencing technologies. The Empirical Bayes framework effectively addresses these challenges by modeling study-specific technical effects while preserving cross-study biological signals.

A representative application involved integrating breast cancer transcriptomic data from three independent studies that used different library preparation methods. ComBat-seq successfully corrected for technical differences, enabling a powerful combined analysis that identified consistent biomarker patterns across studies [9].

Troubleshooting and Methodological Considerations

Common Challenges and Solutions

Despite their robustness, ComBat methods may encounter specific challenges in practical applications. The table below outlines common issues and recommended solutions.

Table 5: Troubleshooting guide for ComBat and ComBat-seq applications

| Challenge | Potential Causes | Diagnostic Approaches | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incomplete batch effect removal | Strong batch effects overlapping with biological signal | PCA visualization coloring by batch and condition | Include biological covariates in model matrix |

| Loss of biological signal | Over-correction due to confounded design | Compare DE results before/after correction | Use reference batch approach (ComBat-ref) |

| High false positive rates | Inadequate shrinkage with small sample sizes | Check shrinkage parameters in model | Enable shrinkage options (shrink=TRUE) |

| Numerical instability | Extreme outliers or zero-inflation | Examine distribution of counts before correction | Filter low-count genes, apply gentle normalization |

| Long computation time | Large datasets (>1000 samples) | Profile code execution | Use pyComBat implementation for speed [21] |

Design Considerations for Optimal Performance

To maximize the effectiveness of ComBat methods, several experimental design considerations should be incorporated:

Balance biological conditions across batches: Ensure each batch contains representatives of all biological conditions of interest. This enables the method to distinguish technical artifacts from biological signals.

Include replicate samples within batches: Technical replicates help estimate batch-specific parameters more reliably.

Avoid completely confounded designs: When batch and condition are perfectly correlated, no statistical method can separate their effects.

Record all potential batch variables: Document processing dates, reagent lots, personnel, and instrument details to inform batch variable specification.

Plan for sufficient sample sizes: While Empirical Bayes methods work with small batches, having at least 3-5 samples per batch improves parameter estimation.

When properly implemented with appropriate experimental design, ComBat and ComBat-seq provide powerful solutions for addressing technical variability in genomic studies, enabling more accurate and reproducible biological discoveries.

Batch effects represent a fundamental challenge in high-throughput genomics, constituting systematic non-biological variations introduced during sample processing and sequencing across different batches. These technical artifacts can be comparable in magnitude to genuine biological differences, significantly compromising data reliability and statistical power in differential expression analysis [2]. In bulk RNA-seq experiments, batch effects arise from various sources including different sequencing times, personnel, reagent lots, equipment, and library preparation protocols, ultimately obscuring true biological signals and potentially leading to erroneous conclusions [24].

The development of effective batch effect correction methods has evolved substantially, with early approaches including empirical Bayes frameworks (ComBat), surrogate variable analysis (SVASeq), and removal of unwanted variation (RUVSeq) [2]. While popular differential analysis packages like edgeR and DESeq2 allow batch inclusion as a covariate in linear models, these approaches often demonstrate reduced statistical power when batch dispersions vary significantly [2]. ComBat-seq emerged as a significant advancement by employing a negative binomial model specifically designed for count data, preserving integer counts crucial for downstream analysis with tools like edgeR and DESeq2 [2]. However, even ComBat-seq exhibits notably lower power in differential expression analysis compared to batch-free data, particularly when using false discovery rate (FDR) for statistical testing [2].