eQTL Mapping: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

This comprehensive review explores expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) mapping as a pivotal methodology bridging genetic variation and gene expression.

eQTL Mapping: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) mapping as a pivotal methodology bridging genetic variation and gene expression. We cover foundational principles of cis- and trans-eQTLs, detailed methodological workflows from genotype quality control to advanced regression models, and address key troubleshooting challenges including overdispersion in RNA-seq data and false discovery control. Highlighting cutting-edge advances in single-cell eQTL mapping and multi-omics integration, we demonstrate how refined eQTL effect sizes facilitate transcriptome-wide association studies and colocalization analyses to pinpoint causal genes for complex traits. This resource provides researchers and drug development professionals with both practical guidance and strategic insights into the evolving landscape of genetic regulation studies.

Understanding eQTLs: Bridging Genetic Variation and Gene Regulation

Expression Quantitative Trait Loci (eQTLs) are genomic loci that explain variation in expression levels of mRNAs or proteins [1]. In essence, they are genetic variants—most commonly single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)—that are significantly associated with the quantitative trait of gene expression abundance [2] [1]. The fundamental principle underlying eQTL mapping is that gene expression itself can be treated as a quantitative trait that is genetically regulated, allowing researchers to identify specific genetic variants that influence how much of a particular gene's transcript is produced [2]. This approach has become a powerful tool for bridging the gap between genetic associations and functional biology, particularly for interpreting the mechanisms through which non-coding genetic variants identified in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) influence disease susceptibility and complex traits [2] [3].

The biological significance of eQTLs lies in their ability to elucidate the functional consequences of genetic variation. While GWAS have successfully identified thousands of genetic variants associated with various diseases and traits, the majority of these variants fall within non-coding regions of the genome, making their biological mechanisms difficult to interpret [2] [4]. eQTL studies address this challenge by connecting these non-coding variants to changes in gene expression, thereby providing crucial insights into the molecular pathways through which genetic variants exert their effects on phenotype [3]. This approach has proven particularly valuable for understanding complex polygenic diseases, where multiple genetic factors interact with environmental influences to determine disease risk and progression [2].

Classification and Characteristics of eQTLs

Fundamental Types of eQTLs

eQTLs are primarily categorized based on their genomic position relative to their target genes, which provides important clues about their potential mechanisms of action. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these primary eQTL types.

Table 1: Classification of Expression Quantitative Trait Loci

| eQTL Type | Genomic Position | Mechanism of Action | Detection Power |

|---|---|---|---|

| cis-eQTL | Proximal to gene (typically within 1 Mb) [3] | Direct effects on regulatory elements (promoters, enhancers) [3] | Higher (due to strong effect sizes) |

| trans-eQTL | Distant from gene (different chromosomal regions) [3] | Indirect effects via upstream regulators (transcription factors, signaling pathways) [3] | Lower (due to weaker effect sizes) |

| cis-acting | Within or near the gene [1] | Affects expression through local regulatory variants | Moderate to high |

| trans-acting | Does not coincide with gene location [1] | Encodes trans-acting factors like transcription factors | Low to moderate |

Key Characteristics and Context Specificity

Beyond their genomic position, eQTLs exhibit several important characteristics that influence their biological interpretation. Effect size varies considerably among eQTLs, with cis-eQTLs typically showing stronger effects than trans-eQTLs due to their direct interaction with local regulatory elements [2]. The allele frequency of eQTL variants also impacts their detection, with rare variants often requiring larger sample sizes to achieve statistical significance [5]. Additionally, eQTL effects demonstrate remarkable context specificity, meaning their influence on gene expression can vary substantially across different tissues, cell types, developmental stages, and environmental conditions [2].

The GTEx study revealed that eQTL tissue detection follows a U-shaped curve, wherein eQTLs tend to be either highly specific to certain tissues or broadly shared across many tissues [2]. This pattern suggests distinct molecular mechanisms underlying tissue-shared versus tissue-specific regulatory effects. Beyond tissue specificity, researchers have identified dynamic eQTLs whose effects change in response to various stimuli, including immune challenges [2], drug treatments [2], cellular stress [2], and disease states [2]. This context dependency highlights the importance of studying eQTLs across diverse biological conditions to fully capture their regulatory potential.

Biological Significance and Mechanisms of Action

Molecular Mechanisms of Gene Regulation

eQTLs influence gene expression through diverse molecular mechanisms that operate at multiple levels of gene regulation. cis-eQTLs typically function by altering sequences in regulatory elements such as promoters, enhancers, silencers, or insulator elements [3]. These variants may create or disrupt transcription factor binding sites, modify chromatin accessibility, or affect DNA methylation patterns, ultimately leading to changes in transcriptional initiation or efficiency. For example, a cis-eQTL located in a promoter region might directly affect the binding affinity of RNA polymerase or specific transcription factors, thereby modulating the rate of transcription initiation for the nearby gene.

trans-eQTLs operate through more indirect mechanisms, often involving the regulation of upstream factors that control the expression of target genes [3]. These may include genes encoding transcription factors, RNA-binding proteins, chromatin-modifying enzymes, or components of signaling pathways [3]. When genetic variation affects the expression or function of these regulatory molecules, it can create cascading effects on multiple downstream target genes, potentially distributed across different chromosomes. The complex regulatory networks coordinated by trans-eQTLs enable systems-level coordination of gene expression programs in response to genetic variation [3].

Relationship to Complex Traits and Diseases

eQTLs play a crucial role in translating genetic associations into biological insights for complex diseases and traits. Studies have consistently shown that SNPs reproducibly associated with complex disorders through GWAS are significantly enriched for eQTLs [1], suggesting that many disease-associated variants exert their effects by modulating gene expression rather than altering protein structure. This enrichment provides a powerful approach for prioritizing candidate genes and understanding biological pathways involved in disease pathogenesis.

In the context of autoimmune diseases such as spondyloarthropathies, eQTL analyses have helped elucidate the functional mechanisms underlying genetic associations in key immune pathways [3]. For example, eQTLs affecting genes in the IL-23/IL-17 axis have been identified as important regulators of immune function in these conditions [3]. Similarly, eQTLs near the HLA-B27 locus have provided insights into how this well-established genetic risk factor contributes to disease development through effects on antigen presentation and processing [3]. By connecting non-coding GWAS variants to specific gene expression changes, eQTL mapping enables researchers to move beyond mere statistical associations toward mechanistic understanding of disease biology.

Experimental Design and Methodological Framework

Core Data Requirements and Quality Control

Conducting a robust eQTL analysis requires careful integration of two primary data types: genotype data and gene expression data. The table below outlines the essential components and quality control steps for each data type.

Table 2: Data Requirements and Quality Control for eQTL Studies

| Data Type | Sources & Tools | Quality Control Metrics | Common Software |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype Data | Whole-genome sequencing, SNP arrays with imputation [5] | Missingness, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, minor allele frequency, relatedness, population stratification [5] | PLINK, VCFtools, GATK, BCFtools [5] |

| Expression Data | RNA-sequencing, microarrays [5] [6] | Normalization, outlier removal, count distribution, batch effects [5] [6] | edgeR, DESeq2, TMM normalization [6] |

Quality control represents a critical foundation for reliable eQTL discovery. For genotype data, this involves both sample-level QC (assessing missingness, gender mismatches, relatedness) and variant-level QC (evaluating Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, minor allele frequency, missingness) [5]. Population stratification must be carefully addressed through methods such as principal component analysis, as systematic differences in ancestry can create spurious associations if not properly accounted for in the statistical model [5]. For expression data, normalization approaches must be carefully selected based on the technology used, with methods such as TMM normalization commonly employed for RNA-seq data [6]. Additional covariates such as age, sex, batch effects, and cellular heterogeneity should be incorporated into the statistical model to reduce confounding and improve power.

Statistical Analysis Frameworks

The core statistical approach for eQTL mapping involves testing associations between each genetic variant and each gene's expression level, typically using linear regression models [5] [6]. However, specific implementations vary based on the nature of the data and research question. For cis-eQTL mapping, the analysis is usually restricted to variants within a predefined window around each gene (typically 1 megabase upstream and downstream of the transcription start site), reducing the multiple testing burden compared to genome-wide analysis [5]. For RNA-seq data, which produces count-based measurements that do not follow a normal distribution, researchers must choose between data transformation approaches (such as inverse normal transformation) [6] or methods specifically designed for count data, such as negative binomial models implemented in edgeR or DESeq2 [6].

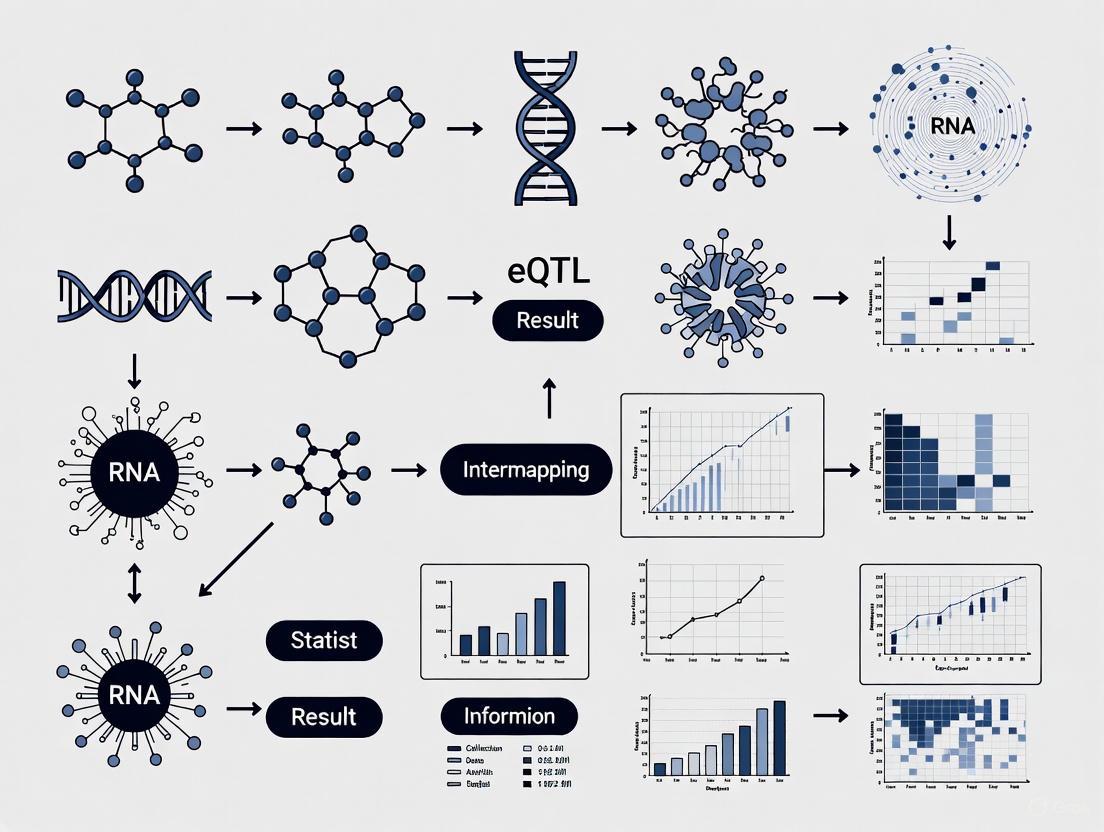

The following diagram illustrates the complete eQTL analysis workflow from raw data to biological interpretation:

Figure 1: eQTL Analysis Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps in expression quantitative trait loci analysis, from quality control of raw genotype and expression data through statistical testing to biological interpretation.

More advanced statistical frameworks continue to be developed to address specific challenges in eQTL mapping. For bulk RNA-seq data, where expression measurements represent averages across potentially heterogeneous cell populations, methods have been developed to estimate and account for cell-type composition [4]. For single-cell RNA-seq data, specialized approaches can leverage the increased resolution to identify cell-type-specific eQTLs, though these analyses must contend with technical artifacts and sparsity inherent to single-cell technologies [2] [4]. Integration methods that combine bulk and single-cell data, such as the IBSEP framework, show promise for enhancing cell-type-specific eQTL prioritization by leveraging the advantages of both data types [4].

Advanced Applications and Integrative Approaches

Integration with GWAS and Colocalization Analysis

One of the most powerful applications of eQTL data lies in its integration with GWAS results through colocalization analysis. This approach tests whether the same genetic variant is responsible for both the expression variation (eQTL signal) and the complex trait association (GWAS signal), providing evidence that the trait-associated variant may exert its effect by regulating gene expression [7]. Successful colocalization not only prioritizes candidate genes underlying GWAS loci but also suggests potential mechanisms of action. For example, colocalization analysis between vitamin D levels in the UK Biobank and molecular QTLs from the eQTL Catalogue revealed that most GWAS loci colocalized with both eQTLs and splicing QTLs, with visual inspection of QTL coverage plots helping to distinguish primary splicing effects from secondary consequences of large-effect expression changes [7].

The biological interpretation of colocalization results can be enhanced by examining the specific nature of the regulatory effect. For instance, eQTLs affecting alternative splicing (sQTLs) can be distinguished from those affecting overall expression levels through visualization of RNA-seq read coverage patterns [7]. These QTL coverage plots display normalized read coverage across gene regions stratified by genotype, allowing researchers to characterize whether a genetic association reflects changes in transcript initiation, splicing, or polyadenylation [7]. This level of mechanistic insight significantly advances our understanding of how non-coding genetic variants contribute to disease susceptibility.

Single-Cell and Context-Specific eQTLs

Recent technological advances have enabled the mapping of eQTLs at single-cell resolution (sc-eQTLs), revealing regulatory effects that are specific to particular cell types or states [2]. Traditional bulk RNA-seq approaches average expression across all cells in a sample, potentially obscuring regulatory effects that occur only in specific cell subpopulations. Single-cell RNA sequencing overcomes this limitation by enabling unbiased quantification of gene expression while preserving intercellular variability [2]. This approach has identified thousands of cell-type-specific and dynamic eQTLs in various tissues, including blood, brain, lung, and induced pluripotent stem cells [2].

Notable single-cell eQTL initiatives include the OneK1k project, which analyzed scRNA-seq data from 1.27 million peripheral blood mononuclear cells from 982 donors and identified numerous cell-type-specific eQTLs, 19% of which shared the same causal locus as a GWAS risk association [2]. Other studies have leveraged single-cell approaches to identify regulatory variants linked to COVID-19 severity [2] and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease [2]. These context-specific eQTLs provide unprecedented resolution into the cellular contexts where disease-associated genetic variants exert their functional effects, offering valuable insights for developing targeted therapeutic interventions.

Successful eQTL research relies on both high-quality experimental materials and sophisticated computational tools. The table below catalogues essential research reagents and resources that support various stages of eQTL studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for eQTL Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Repositories | eQTL Catalogue [8], GTEx Portal [2], eQTLGen [2] | Publicly available summary statistics | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/eqtl/ [8], https://gtexportal.org/ [2] |

| Genotype Calling | GATK [5], BCFtools [5], DeepVariant [5] | Variant detection from sequencing data | Open source tools |

| Quality Control | PLINK [5], VCFtools [5] | Genotype and sample QC | Open source tools |

| eQTL Mapping | Matrix eQTL [1], edgeR [6] | Association testing | Open source packages |

| Functional Validation | CRISPR-based perturbations [3], ChIP-seq [3] | Mechanistic follow-up | Experimental methods |

The eQTL Catalogue deserves particular emphasis as a comprehensive resource that provides uniformly processed gene expression and splicing QTLs from all available public studies on humans [8] [7]. This resource focuses specifically on cis-eQTLs and splicing QTLs (sQTLs) and has proven particularly useful for statistical geneticists exploring GWAS results who wish to associate non-coding GWAS SNP associations with molecular mechanisms such as perturbed gene expression or splicing [8]. The Catalogue is continuously updated, with recent enhancements including the addition of X chromosome QTLs, improved quantification of splicing and promoter usage QTLs using LeafCutter, and fine-mapping-based filtering to identify independent genetic signals [7]. These developments significantly improve the utility of the resource for interpreting complex trait associations.

The field of eQTL research continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends likely to shape future investigations. Multi-omic QTL mapping represents an important frontier, with researchers increasingly integrating eQTLs with other molecular QTL types such as protein QTLs (pQTLs), methylation QTLs (meQTLs), and chromatin QTLs (caQTLs) to build comprehensive models of how genetic variation influences molecular phenotypes across multiple regulatory layers [5]. Increased diversity in study populations represents another critical direction, as most eQTL studies to date have focused primarily on individuals of European ancestry, creating disparities in the applicability of findings across human populations [2]. Expanding eQTL mapping to underrepresented populations will improve the equity and generalizability of genetic insights.

Therapeutic applications of eQTL findings continue to grow, with drug target prioritization emerging as a particularly promising area. Notably, genes harboring paternal eQTLs show significant enrichment for drug targets [9], suggesting that parent-of-origin effects may have important implications for pharmaceutical development. Additionally, context-specific eQTLs identified in disease-relevant tissues and conditions offer opportunities for developing targeted interventions that account for both genetic background and environmental context [2]. As eQTL resources expand and methodologies refine, the integration of genetic regulatory information into therapeutic development pipelines will likely become increasingly routine.

In conclusion, eQTL mapping has transformed our understanding of the functional consequences of genetic variation and continues to provide crucial insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying complex traits and diseases. From fundamental concepts to advanced applications, the study of expression quantitative trait loci represents an essential framework for bridging the gap between statistical genetic associations and biological mechanism. As technologies advance and datasets grow, eQTL approaches will undoubtedly remain central to efforts to decipher the complex relationship between genotype and phenotype in human health and disease.

Expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) mapping has become an indispensable tool for interpreting the regulatory mechanisms of disease-associated genetic variants identified through genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [10] [11]. eQTLs are genomic loci where genetic variation, typically single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), is associated with changes in gene expression levels [12]. These regulatory associations are broadly categorized into two classes based on the genomic proximity between the variant and the target gene: cis-eQTLs and trans-eQTLs [12]. Understanding the distinct characteristics, detection methodologies, and biological mechanisms of these two eQTL classes is fundamental to elucidating how genetic variation shapes transcriptional networks and complex disease phenotypes [13].

cis-eQTLs represent "local" regulation, where the genetic variant is located near the gene it influences, typically within a 1 megabase (Mb) window from the transcription start site [10] [12]. In contrast, trans-eQTLs represent "distant" regulation, where the variant is located far from the target gene (>5 Mb) or on a different chromosome [10] [12]. This fundamental distinction in genomic proximity underlies critical differences in their effect sizes, detection power, replication rates, and underlying biological mechanisms, which will be explored in detail throughout this application note.

Fundamental Distinctions Between cis- and trans-eQTLs

Definition and Genomic Proximity

The primary distinction between cis- and trans-eQTLs lies in their spatial relationship to their target genes. The following table summarizes their core defining characteristics:

Table 1: Core Characteristics of cis- vs. trans-eQTLs

| Feature | cis-eQTL | trans-eQTL |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Distance | Within 1 Mb of the target gene [12] | >5 Mb from the target gene or on a different chromosome [10] [12] |

| Presumed Mechanism | Direct, local effects on promoter/enhancer function [10] | Indirect, often mediated by intermediary molecules like transcription factors [13] [14] |

| Typical Effect Size | Stronger [10] [15] | Weaker [10] [15] |

| Detection Power | Requires smaller sample sizes [10] | Requires very large sample sizes (e.g., N > 30,000) [10] |

| Tissue Specificity | Often conserved across tissues [10] [12] | Frequently tissue- or cell-type-specific [12] [16] |

Detection Rates and Sample Size Requirements

Large-scale consortium efforts have quantified the striking differences in detection rates between cis- and trans-eQTLs. In a meta-analysis of 31,684 individuals through the eQTLGen Consortium, cis-eQTLs were detected for 88% (16,987) of tested genes, demonstrating their pervasive nature [10]. In contrast, distal trans-eQTLs were identified for only 37% of the 10,317 trait-associated variants tested, affecting 6,298 genes [10]. This disparity stems primarily from the typically smaller effect sizes of trans-eQTLs, necessitating substantially larger sample sizes for their detection [10] [14]. The largest previous trans-eQTL meta-analysis in blood (N=5,311) identified trans-eQTLs for only 8% of tested SNPs, highlighting how increased sample size dramatically improves detection power for these subtle effects [10].

Diagram 1: Detection Power for eQTL Types

Underlying Regulatory Mechanisms

cis-eQTL Mechanisms

cis-eQTLs are thought to exert their effects through direct, local mechanisms by altering DNA sequence elements that directly influence gene transcription. They typically involve polymorphisms within regulatory regions such as promoters, enhancers, or other cis-regulatory elements that affect transcription factor binding, chromatin accessibility, or epigenetic modifications [10]. Evidence from capture Hi-C data indicates that lead cis-eQTL SNPs located more than 100 kb from the transcription start site show a significant 2.0-fold enrichment in overlapping with physical chromatin contacts, suggesting that long-range cis-eQTLs can function through direct chromosomal looping interactions that bring distal regulatory elements into proximity with their target genes [10].

trans-eQTL Mechanisms

trans-eQTLs operate through more complex, indirect mechanisms. A predominant mechanism identified through mediation analysis is cis-mediation, where a genetic variant first regulates the expression of a local gene (a cis-eQTL), and the product of that gene (e.g., a transcription factor or RNA-binding protein) subsequently regulates the expression of a distal target gene (the trans-eGene) [13] [14]. For example, in an analysis of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex tissue, over 60% of trans-eQTL variants showed evidence that a cis-eGene acted as a mediator for the trans-eQTL's effect on the trans-eGene [13]. This creates a regulatory cascade where the trans-effect is mechanistically explained by an intermediate cis-effect.

Diagram 2: cis-Mediation in trans-eQTL Mechanism

These mediated trans-effects often form trans-eQTL hotspots, where a single genomic region regulates the expression of multiple distant genes [13] [15]. These hotspots frequently involve key regulatory genes such as transcription factors, and their effects can be highly specific to environmental contexts, such as exposure to toxins like lead [15].

Experimental Protocols for eQTL Mapping

Bulk Tissue eQTL Mapping Protocol

The following protocol outlines a standard pipeline for genome-wide cis- and trans-eQTL mapping from bulk tissue RNA-seq data, based on methodologies from large consortia like eQTLGen and PsychENCODE [10] [13].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for eQTL Mapping

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Genotype Data | Provides genetic variant information for association testing | Whole-genome sequencing or SNP array data, imputed to reference panels (e.g., Haplotype Reference Consortium) [13] |

| RNA-seq Data | Quantifies genome-wide gene expression levels | Bulk tissue: 30-50 million reads per sample; Single-cell: 50,000 reads per cell [13] [16] |

| Covariates | Controls for technical and biological confounding | Genotype PCs, sex, study batch, PEER factors [13] |

| QTL Mapping Software | Performs association testing between genotypes and expression | QTLtools [13], Matrix eQTL, FastQTL |

Sample Preparation and Sequencing

- Genotype Data Processing: Process genomic DNA using standard whole-genome sequencing or SNP array protocols. Impute genotypes to a reference panel (e.g., Haplotype Reference Consortium) using the Michigan Imputation Server [13]. Apply standard quality control filters: sample call rate >98%, SNP call rate >95%, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium P > 1×10⁻⁶, and minor allele frequency >1%.

- RNA Sequencing: Extract total RNA from target tissue (e.g., whole blood, prefrontal cortex). Prepare stranded RNA-seq libraries using poly-A selection. Sequence to a minimum depth of 30 million reads per sample on an Illumina platform. Process raw sequencing data through a standardized pipeline for adapter trimming, quality control, and alignment to a reference genome (e.g., STAR aligner).

Expression Quantification and Normalization

- Gene Expression Quantification: Generate raw count matrices from aligned BAM files using featureCounts or similar tools. Filter out lowly expressed genes not detected in at least 10% of samples [13].

- Expression Normalization: Normalize raw counts using a two-step approach. First, apply quantile normalization to account for technical variation. Follow with inverse quantile normalization to map expression values to a standard normal distribution, effectively removing outliers and ensuring expression values are normally distributed for subsequent linear modeling [13].

Covariate Selection and Correction

- Covariate Selection: Calculate potential covariates including:

- Genotype principal components (PCs) to account for population stratification (typically 3-5 PCs) [13].

- Probabilistic estimation of expression residuals (PEER) factors to capture hidden confounders (e.g., 50 PEER factors for N~1,400 samples) [13].

- Technical factors (sequencing batch, RIN) and biological factors (sex, age).

- Covariate Regression: Regress out the selected covariates from the normalized expression matrix to generate residual expression values for QTL testing.

QTL Association Testing

- cis-eQTL Mapping: For each gene, test all SNPs within a 1 Mb window of the gene's transcription start site. Use linear regression with an additive genetic model. In QTLtools, this is implemented with the

ciscommand [13]. - trans-eQTL Mapping: For each gene, test all SNPs located >5 Mb from the gene or on different chromosomes. Due to the massive multiple testing burden (trillions of tests), prioritize testing for trans-eQTLs by focusing on previously identified GWAS hits or using conditional methods [10].

Multiple Testing Correction

- Permutation Testing: Perform 1,000 permutations per gene by shuffering expression labels to establish null distributions of association statistics [10].

- FDR Control: Apply Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction to identify significant eQTLs at a desired threshold (e.g., FDR < 5% for cis-eQTLs, FDR < 25% for trans-eQTLs given lower power) [10] [13].

Single-Cell eQTL Mapping Protocol

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) enables the identification of cell-type-specific eQTLs masked in bulk tissue analyses [16]. The following protocol adapts the bulk approach for scRNA-seq data.

Single-Cell Data Generation and Processing

- Cell Processing and Multiplexing: Use a pooled multiplexing strategy to profile cells from hundreds of individuals simultaneously [16]. For gastric tissue, 399,683 cells from 203 individuals represents an appropriate scale [16].

- Cell-type Identification: Perform clustering based on gene expression patterns to identify distinct cell types. Use canonical markers to annotate cell populations (e.g., parietal cells express ATP4A) [16].

Expression Matrix Creation

- Pseudobulk Creation: For each individual and each cell type, aggregate raw counts across all cells of that type to create a pseudobulk expression profile. This approach increases power by reducing sparsity and enabling use of bulk QTL methods [17].

- Normalization: Normalize pseudobulk counts using the same two-step quantile normalization approach as for bulk data.

Cell-type-specific QTL Mapping

- Stratified Analysis: Run independent cis-eQTL mappings for each cell type using the pseudobulk expression matrices and standard cis-eQTL pipeline.

- Meta-Analysis: For increased power, perform a weighted meta-analysis across multiple single-cell datasets. Optimal weights can be based on the average number of molecules detected per cell, which outperforms simple sample-size weighting [17].

Diagram 3: Single-Cell eQTL Workflow

Applications in Disease Gene Prioritization

eQTL data, particularly trans-eQTLs, provides a powerful approach for prioritizing putative causal genes at disease-associated loci identified by GWAS. The following table demonstrates how different eQTL integration strategies contribute to gene discovery for complex traits:

Table 3: eQTL Applications in Disease Gene Discovery

| Application | Approach | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Polygenic Score Correlation | Correlate polygenic scores for 1,263 phenotypes with gene expression (eQTS analysis) | Expression of 13% (2,568) of genes correlated with polygenic scores, pinpointing potential driver genes for complex traits [10] |

| trans-eQTL Colocalization | Colocalization between trans-eQTLs and schizophrenia GWAS loci | Linked an additional 23 GWAS loci and 90 risk genes beyond what was possible using only cis-eQTLs [13] |

| Cell-type-specific TWAS | Integrate scRNA-seq eQTLs with GWAS using transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS) | Identified 15 gastric cancer risk genes with cell-type-specific regulation, including MUC1 upregulation in parietal cells associated with decreased cancer risk [16] |

| Network-based Mapping | Trans-PCO method maps trans effects of variants on gene networks | Identified 14,985 trans-eSNP-module pairs in blood, revealing how trait-associated variants affect biological pathways [18] |

cis- and trans-eQTLs represent distinct paradigms of gene regulation with profound implications for understanding the functional consequences of genetic variation. cis-eQTLs act locally with stronger effects and are more readily detectable, providing a direct link between genetic variants and proximal gene expression. In contrast, trans-eQTLs operate through complex, often mediated mechanisms with weaker effects, requiring massive sample sizes for detection but revealing extensive regulatory networks that connect genetic variation to systemic transcriptional changes. The integration of both cis- and trans-eQTL information, particularly with emerging single-cell technologies and advanced network analysis methods, provides a more complete picture of the regulatory architecture of complex traits and diseases. These approaches are illuminating the path from genetic variation to phenotype, offering new opportunities for understanding disease mechanisms and identifying therapeutic targets.

eQTLs as Functional Interpreters of GWAS Findings in Disease Loci

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have successfully identified thousands of genetic variants associated with complex diseases. However, a significant challenge remains in moving from these statistical associations to biological understanding, as the majority of disease-associated variants reside in non-coding regions of the genome [19] [20]. Expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) mapping has emerged as a powerful approach to address this interpretation gap by identifying genetic variants that influence gene expression levels. These eQTLs serve as crucial functional interpreters that can mechanistically link non-coding GWAS variants to their potential target genes and regulatory pathways [19] [21]. This application note provides a comprehensive framework for integrating eQTL data with GWAS findings to elucidate the functional consequences of disease-associated genetic variants, with detailed protocols for analysis, visualization, and interpretation suited for researchers and drug development professionals.

Background and Significance

The Interpretation Gap in GWAS Findings

Despite the success of GWAS in identifying disease-associated loci, approximately 90% of these variants fall within non-coding regions, making their functional characterization challenging [21]. These non-coding variants likely influence disease susceptibility through the regulation of gene expression rather than through direct protein alteration. This creates a critical interpretation gap where statistical associations are identified without clear mechanistic understanding of how these variants contribute to disease pathogenesis [19] [20].

eQTLs as Functional Bridges

Expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) represent genomic regions that regulate gene expression levels either in cis (proximal to the gene) or in trans (distal to the gene, often on different chromosomes) [19]. Cis-eQTLs typically influence gene expression by directly affecting regulatory elements such as promoters and enhancers located near the gene, while trans-eQTLs exert their effects indirectly by modulating upstream regulators including transcription factors, signaling pathways, or chromatin-modifying proteins [19]. The fundamental premise of using eQTLs to interpret GWAS findings is that if a GWAS variant associated with a disease also influences gene expression levels, it provides compelling evidence for a mechanistic link between that gene and the disease pathology [20].

Table 1: Classification of eQTL Types and Their Characteristics

| eQTL Type | Genomic Position | Mechanism of Action | Detection Power | Interpretive Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cis-eQTL | Proximal to gene (<1Mb) | Direct effects on promoters/enhancers | High | Straightforward gene assignment |

| trans-eQTL | Distant from gene (any chromosome) | Modulation of upstream regulators | Lower (requires larger sample sizes) | Reveals regulatory networks |

| Cell-type-specific eQTL | Any location | Context-dependent regulatory effects | Variable (depends on cell type availability) | High biological specificity |

Advancements in eQTL Methodologies

Recent methodological advances have significantly enhanced the resolution and context specificity of eQTL mapping. The emergence of single-cell eQTL (sc-eQTL) mapping has enabled the identification of cell-type-specific regulatory effects that were previously obscured in bulk tissue analyses [21] [17]. Additionally, novel computational approaches such as the JOBS (Joint model of bulk eQTLs as a weighted sum of sc-eQTLs) method have improved detection power by integrating bulk and single-cell eQTL data [21]. These advancements are particularly relevant for complex diseases where cellular heterogeneity may mask important biological signals.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Fundamental eQTL Mapping Protocol

The core protocol for eQTL mapping involves systematic analysis of correlations between genetic variants and gene expression levels across individuals. The following detailed methodology can be applied across various study designs and tissue types:

Data Collection and Quality Control

- Genotype Data: Perform standard GWAS quality control including filtering for call rate (>95%), Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p > 1×10⁻⁶), and minor allele frequency (>1%). Impute missing genotypes using reference panels (e.g., 1000 Genomes) [22].

- Expression Data: Process RNA-seq data with standard pipelines. Filter for genes with sufficient expression (e.g., >0.1 TPM in >20% of samples). Normalize for technical covariates and transform as needed [23] [22].

- Covariate Data: Collect and process potential confounding variables including age, sex, batch effects, and population structure (genetic principal components).

Cis-eQTL Mapping Analysis

- Define a cis-window for each gene (typically ±1 Mb from the transcription start site).

- For each gene-SNP pair within cis-windows, perform association testing using linear regression:

Expression ~ Genotype + Technical Covariates + Genetic Principal Components[22] [20]. - Apply multiple testing correction using Bonferroni correction or false discovery rate (FDR) control. A standard threshold is FDR < 0.05 or 0.10 [17].

- For enhanced power in small sample sizes, utilize permutation testing (1,000-3,000 permutations) to establish empirical significance thresholds [22].

Validation and Replication

- Split data into discovery and replication sets, or replicate findings in independent cohorts.

- Perform sensitivity analyses to assess robustness to covariate adjustment and normalization methods.

Colocalization Analysis Protocol

Colocalization analysis determines whether the same underlying genetic variant is responsible for both GWAS and eQTL signals, providing evidence for a causal relationship:

Data Preparation

- Extract GWAS summary statistics for the region of interest, including p-values, effect sizes, and standard errors for all variants.

- Obtain eQTL summary statistics from relevant tissues or cell types, formatted with consistent variant identifiers [20].

- Calculate or obtain linkage disequilibrium (LD) matrices for the population of interest.

Colocalization Testing

- Implement statistical colocalization tests (e.g., COLOC, eCAVIAR) to assess whether one shared variant explains both signals.

- Set prior probabilities for shared associations (typical defaults: p1 = 1×10⁻⁴, p2 = 1×10⁻⁴, p12 = 1×10⁻⁵).

- Compute posterior probabilities for five hypotheses: (1) no association with either trait, (2) association with GWAS only, (3) association with eQTL only, (4) association with both, different variants, (5) association with both, shared variant.

Interpretation and Validation

- Consider colocalization supported when posterior probability for shared variant (H4) > 0.70-0.80.

- Perform sensitivity analyses to assess robustness to prior specifications.

- Visually inspect regional association plots to confirm colocalization [20].

Table 2: Key Software Tools for eQTL and Colocalization Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Input Requirements | Output | Access |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eQTpLot | Visualization of eQTL-GWAS colocalization | GWAS and eQTL summary statistics | Integrated plots showing colocalization | https://github.com/RitchieLab/eQTpLot [20] |

| JOBS | Joint analysis of bulk and single-cell eQTLs | Bulk and single-cell eQTL data | Enhanced power eQTL detection | Custom implementation [21] |

| METAL | Weighted meta-analysis of eQTL studies | Summary statistics from multiple studies | Combined effect estimates | https://github.com/statgen/METAL [17] |

| COLOC | Bayesian colocalization analysis | GWAS and eQTL summary statistics | Posterior probabilities for colocalization | R package [20] |

Single-Cell eQTL Meta-Analysis Protocol

Single-cell RNA sequencing enables eQTL mapping at cellular resolution but presents challenges for meta-analysis due to technical variability and smaller sample sizes. The following protocol outlines best practices for single-cell eQTL meta-analysis based on recent methodological developments:

Dataset Processing and Harmonization

- Process each single-cell dataset individually using standardized pipelines (e.g., CellRanger, Seurat).

- Generate pseudobulk expression profiles by aggregating counts per donor per cell type.

- Perform cis-eQTL mapping separately for each dataset using pseudobulk profiles [17].

Weighted Meta-Analysis Implementation

- Extract summary statistics (effect sizes, standard errors, p-values) from each dataset.

- Apply weighted meta-analysis using optimal weights. Recent evidence suggests:

- Combine statistics using inverse-variance weighted fixed-effects models:

β_meta = Σ(w_i * β_i) / Σ(w_i)wherew_i = 1 / (SE_i)².

Significance Evaluation and Multiple Testing Correction

- Perform 1,000 gene-level permutations to establish empirical null distributions.

- Apply Benjamini-Hochberg FDR correction to the top eQTL per gene.

- Consider associations significant at FDR < 10% [17].

Data Presentation and Visualization

Structured Data Presentation

Effective presentation of eQTL and GWAS integration results requires clear organization of complex multidimensional data. The following tables provide standardized formats for reporting key findings:

Table 3: Summary of Significant Colocalization Results Between GWAS and eQTL Signals

| GWAS Trait | Genomic Locus | Candidate Gene | Lead SNP | GWAS p-value | eQTL p-value | Colocalization Posterior Probability | Tissue/Cell Type | Potential Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ankylosing Spondylitis | 1p31.3 | IL23R | rs11209026 | 3.2×10⁻¹² | 2.1×10⁻¹⁰ | 0.92 | CD4+ T cells | IL-23/IL-17 axis dysregulation [19] |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease | 2q37.1 | ERAP1 | rs27434 | 6.8×10⁻⁰⁹ | 4.3×10⁻⁰⁸ | 0.87 | Monocytes | Antigen processing and presentation [19] |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 12q15 | TYK2 | rs34536443 | 2.4×10⁻¹⁰ | 7.9×10⁻⁰⁹ | 0.79 | Multiple immune cells | Cytokine signaling threshold modulation [19] |

Table 4: Comparison of eQTL Meta-Analysis Weighting Strategies

| Weighting Strategy | Use Case | Mathematical Formulation | *Relative Performance | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | Homogeneous datasets with similar quality | wi = √Ni | Baseline | Simplest to implement [17] |

| Standard Error | Datasets with variable precision | wi = 1 / (SEi)² | Best for multiple datasets (+50% eGenes) | Requires sharing standard errors [17] |

| Counts Per Cell | Single-cell pairwise meta-analysis | w_i = mean(UMIs/cell) | Excellent for pairwise analyses (+36% eGenes) | Captures technical quality [17] |

| Average Number of Cells | Single-cell studies with variable coverage | w_i = mean(cells/donor) | Excellent for pairwise analyses | Reflects cellular resolution [17] |

*Performance metrics relative to sample size weighting based on benchmark studies [17]

Advanced Visualization Techniques

Visualization is critical for interpreting the complex relationships between GWAS and eQTL signals. The eQTpLot R package provides specialized visualization capabilities [20]:

Colocalization Visualization

- Generate scatter plots showing -log10(p-values) for GWAS (y-axis) against eQTL (x-axis) associations.

- Color points by linkage disequilibrium with the lead variant to highlight regional patterns.

- Overlay smoothed curves indicating the strength of association across the genomic region.

Direction of Effect Visualization

- Implement the "congruence" parameter to divide variants into:

- Congruous: Same direction of effect on gene expression and GWAS trait.

- Incongruous: Opposite directions of effect.

- Use contrasting colors (e.g., blue vs. red) to visually distinguish these categories [20].

- Implement the "congruence" parameter to divide variants into:

Multi-Tissue Visualization

- For pan-tissue or multi-tissue analyses, implement the "CollapseMethod" parameter with options:

- "min": Selects the smallest eQTL p-value across tissues.

- "mean"/"median": Averages p-values and normalized effect sizes (NES) across tissues.

- "meta": Performs sample-size-weighted meta-analysis across tissues [20].

- For pan-tissue or multi-tissue analyses, implement the "CollapseMethod" parameter with options:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 5: Key Research Reagent Solutions for eQTL Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Category | Specifications | Application | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population scRNA-seq Datasets | Data Resource | 10X Genomics V2/V3, Smart-seq2 | Cell-type-specific eQTL mapping | OneK1K, eQTLGen [21] [17] |

| Bulk Tissue eQTL References | Data Resource | Large sample sizes (>30,000) | Benchmarking and power assessment | eQTLGen, GTEx [20] [17] |

| eQTL Analysis Software | Computational Tool | R/Python implementations | Statistical analysis and visualization | eQTpLot, mashr, fastSTRUCTURE [20] [24] |

| Quality Control Pipelines | Computational Tool | Standardized processing | Data harmonization and normalization | CellRanger, Seurat, STAR [17] |

| GWAS Summary Statistics | Data Resource | Disease-specific associations | Colocalization analysis | GWAS Catalog, disease consortia [19] [20] |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

The integration of eQTL data with GWAS findings has profound implications for drug discovery and development, enabling:

Target Prioritization and Validation

- eQTL colocalization provides orthogonal evidence for causal gene identification, enhancing confidence in potential drug targets.

- Direction of effect analysis helps predict whether therapeutic intervention should increase or decrease target activity [20].

Drug Repurposing Opportunities

- Integration of eQTL data with knowledge bases can identify existing drugs that modulate expression of candidate genes.

- The JOBS framework has demonstrated successful identification of novel drug classes for autoimmune diseases through this approach [21].

Clinical Trial Enrichment

eQTL analysis has transformed from a specialized genetic approach to an essential tool for functional interpretation of GWAS findings. The protocols and applications outlined in this document provide researchers with a comprehensive framework for integrating eQTL data into their disease genomics workflow. As single-cell technologies and advanced meta-analysis methods continue to evolve, the resolution and utility of eQTL mapping for drug discovery will further increase, solidifying its role as a cornerstone of functional genomics in the coming years.

Expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) mapping has revolutionized our understanding of how genetic variation influences gene expression, thereby bridging the gap between genotype and phenotype. An eQTL is a genomic locus that explains variation in the expression levels of mRNAs [25]. eQTLs are categorized based on their genomic position relative to their target gene: cis-eQTLs are located proximal to the gene they regulate, typically affecting regulatory elements such as promoters and enhancers, while trans-eQTLs exert their effects distantly, often through intermediate regulators like transcription factors or signaling pathways [19] [2]. The identification of eQTLs provides a powerful biological mechanism to interpret findings from genome-wide association studies (GWAS), particularly for variants in non-coding regions with previously unknown functions [19] [2].

The functional interpretation of most statistically associated variants from GWAS has been a significant challenge. eQTL analysis addresses this by directly linking genetic variants to changes in gene expression, thereby elucidating the molecular genetic pathways that contribute to complex traits [2]. This approach is particularly valuable for understanding the genetic architecture of immune-mediated diseases, where context-specific gene regulation plays a crucial role in disease pathogenesis.

The IL-23/IL-17 Axis: A Prime Example from eQTL Research

The IL-23/IL-17 axis represents a pivotal pro-inflammatory signaling pathway that plays a central role in host defense, autoimmune diseases, and chronic inflammation [26] [27] [28]. This axis centers on the function of T helper 17 (Th17) cells, a distinct subset of CD4+ T cells. IL-23, a heterodimeric cytokine composed of p40 and p19 subunits, is produced primarily by dendritic cells and macrophages [19] [26]. It promotes the differentiation, expansion, and maintenance of Th17 cells, which subsequently produce effector cytokines including IL-17A, IL-17F, TNF-α, and IL-6 [26] [27].

IL-17A (commonly referred to as IL-17) is the most prominent family member and functions as a highly versatile proinflammatory cytokine. The IL-17 family comprises six structurally related cytokines (IL-17A through IL-17F) that signal through a five-member receptor family (IL-17RA through IL-17RE) [28]. IL-17A and IL-17F activate downstream signaling primarily through IL-17RA and IL-17RC heterodimers, initiating a cascade that leads to the production of antimicrobial peptides, chemokines, and other inflammatory mediators [27] [28].

Table 1: Key Cytokines and Receptors in the IL-23/IL-17 Axis

| Component | Type | Function in the Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| IL-23 | Heterodimeric cytokine (p40/p19) | Drives Th17 cell differentiation, expansion, and maintenance [26] |

| IL-17A | Effector cytokine | Induces inflammatory mediators; stimulates keratinocyte proliferation [27] |

| IL-17F | Effector cytokine | Shares functions with IL-17A but with reduced potency [28] |

| IL-17RA | Receptor subunit | Common signaling subunit for multiple IL-17 family cytokines [28] |

| IL-17RC | Receptor subunit | Forms heterodimer with IL-17RA for IL-17A/F signaling [28] |

| IL-23R | Receptor subunit | Confers specificity for IL-23 binding and signaling [19] |

Genetic Regulation of the Axis by eQTLs

eQTL studies have been instrumental in elucidating how genetic variation influences the IL-23/IL-17 axis and contributes to inflammatory disease susceptibility. Several key genes in this pathway are regulated by identified eQTLs:

IL23R eQTLs: Multiple studies have identified cis-eQTLs that modulate IL23R expression, particularly in immune cell subsets such as CD4+ T cells. These regulatory variants contribute to dysregulated IL-23-mediated signaling in genetically predisposed individuals [19]. The identification of these eQTLs provides a biological mechanism for the strong genetic association between IL23R polymorphisms and inflammatory diseases.

TYK2 eQTLs: Genetic variants in TYK2, which encodes a tyrosine kinase essential for IL-23 signal transduction, have been shown to influence cytokine signaling thresholds. This ultimately impacts Th17 cell differentiation and effector function, demonstrating how eQTLs can fine-tune signaling pathways [19].

Cell-Type Specificity: A crucial finding from eQTL research is that these regulatory effects often show significant cell-type specificity. For instance, cis-eQTLs for IL23R and TYK2 are active in CD4+ T cells but may be absent in other cell types, highlighting the importance of examining eQTLs in relevant cellular contexts for understanding disease mechanisms [19].

The following diagram illustrates the core IL-23/IL-17 signaling pathway and its key genetic regulators identified through eQTL studies:

Methodological Framework for eQTL Mapping

Core Experimental Protocols

The standard workflow for eQTL mapping involves integrating genotype data with gene expression data from the same individuals to identify statistically significant associations. The following protocol outlines the key steps:

1. Study Design and Sample Collection

- Recruit a sufficient number of participants (typically hundreds to thousands) to achieve adequate statistical power [2] [17].

- Collect appropriate tissue or cell samples relevant to the biological question. For immune-mediated diseases like those involving the IL-23/IL-17 axis, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or specific immune cell subsets are commonly used [19] [17].

- For cell-type-specific eQTLs, consider single-cell RNA sequencing or sorted cell populations to avoid confounding effects from cellular heterogeneity [2].

2. Genotyping and Quality Control

- Perform genome-wide genotyping using microarray technologies or whole-genome sequencing.

- Apply standard quality control filters: exclude samples with high missing genotype rates, remove SNPs with low minor allele frequency (typically <5%), and test for deviations from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium [22] [25].

3. Gene Expression Profiling

- Extract total RNA from samples using standardized protocols.

- Perform RNA sequencing using platforms such as Illumina NovaSeq, generating sufficient sequencing depth (typically 50-100 million reads per sample for bulk RNA-seq) [25].

- Align reads to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) using aligners like STAR.

- Quantify gene-level counts using tools such as featureCounts [25].

- Filter lowly expressed genes (e.g., total read count <200 or zero counts in many samples).

- Normalize expression data using methods such as Variance Stabilizing Transformation (VST) in DESeq2 or the TMM method [25].

4. Covariate Adjustment

- Account for technical covariates (e.g., batch effects, sequencing platform) and biological covariates (e.g., age, sex) that might confound eQTL associations.

- Use principal component analysis (PCA) or PEER factors to account for hidden confounders [29] [17].

5. Statistical Association Testing

- For cis-eQTL mapping, typically test SNPs within a 1 Mb window around the transcription start site of each gene.

- Perform regression analysis with genotype as the predictor and normalized expression as the response variable.

- For bulk RNA-seq data, linear regression or non-parametric methods can be used. For single-cell data, specialized methods accounting for zero-inflation are recommended [2] [17].

- Correct for multiple testing using False Discovery Rate (FDR) methods, with significance typically defined as FDR <5% [17] [25].

6. Validation and Functional Characterization

- Replicate significant eQTLs in independent cohorts.

- Perform colocalization analysis to determine if GWAS and eQTL signals share the same causal variant [19] [29].

- Use functional assays such as CRISPR-based perturbations or chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) to validate regulatory mechanisms [19].

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Recent methodological advances have enhanced the resolution and accuracy of eQTL mapping:

Single-Cell eQTL Mapping: The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has enabled the identification of cell-type-specific eQTLs that were previously masked in bulk tissue analyses [2]. Specialized computational approaches are required to account for the unique characteristics of scRNA-seq data, including sparsity (dropouts), technical noise, and complex count distributions [2] [17].

Meta-Analysis Approaches: For increased statistical power, researchers often combine eQTL summary statistics from multiple studies through meta-analysis. Weighted meta-analysis (WMA) approaches optimally integrate results across datasets, with weights based on sample size, standard error, or single-cell-specific parameters such as average number of cells per donor or molecules detected per cell [17].

Multi-omics Integration: Integrating eQTL data with other molecular QTLs, such as methylation QTLs (mQTLs) and protein QTLs (pQTLs), through methods like summary-data-based Mendelian randomization (SMR) provides a more comprehensive understanding of causal pathways from genetic variation to disease [29].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in a modern eQTL mapping study:

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for eQTL Studies

| Reagent/Platform | Specific Function | Application in eQTL Research |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | High-throughput sequencing | RNA sequencing for gene expression profiling [25] |

| Illumina TruSeq RNA Sample Prep Kit | cDNA library preparation | Construction of sequencing libraries from RNA [25] |

| QIAzol Lysis Reagent | RNA isolation | Total RNA extraction from tissue samples [25] |

| 10X Genomics Chromium | Single-cell partitioning | Single-cell RNA sequencing for cell-type-specific eQTLs [17] |

| Smart-seq2 | Full-length scRNA-seq | Alternative platform for single-cell eQTL studies [17] |

| SOMAscan Platform | Proteomic profiling | Protein quantification for pQTL studies [29] |

| Olink Explore Platform | Multiplex protein detection | Validation of protein-level associations [29] |

Concluding Perspectives

eQTL mapping has transformed our understanding of how genetic variation regulates gene expression in the IL-23/IL-17 pathway and other key biological systems. The methodological framework outlined here provides researchers with robust tools to identify context-specific regulatory variants and elucidate their functional consequences. As single-cell technologies and multi-omics integration continue to advance, eQTL studies will offer increasingly precise insights into disease mechanisms and identify novel therapeutic targets for immune-mediated disorders.

Tissue and Cell Type Specificity in eQTL Effects

Expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) mapping has emerged as a powerful approach for elucidating the functional consequences of genetic variants and unraveling the causal mechanisms underlying complex diseases [11]. While traditional eQTL studies conducted in bulk tissues have identified numerous genetic variants regulating gene expression, they mask the substantial heterogeneity present within complex tissues. Tissue and cell type specificity in eQTL effects represents a critical layer of biological complexity that must be resolved to accurately connect genetic associations to molecular mechanisms. This application note frames this specificity within the broader context of eQTL mapping research, providing detailed protocols and analytical frameworks for researchers investigating genetic regulation across diverse cellular environments.

Recent advances in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) have enabled the detection of eQTLs at unprecedented resolution, revealing that a substantial fraction of genetic regulatory effects operate in a cell-type-specific manner [30] [16]. These findings have profound implications for understanding disease pathogenesis, particularly for complex traits where specific cell types mediate genetic risk. The integration of single-cell eQTL mapping with genome-wide association studies (GWAS) now provides a powerful framework for identifying cell-type-specific susceptibility genes and understanding how genetic variants exert their effects in precise cellular contexts.

Key Concepts and Definitions

eQTL Fundamentals

An expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) refers to a genetic variation associated with the expression level of a specific gene [11]. eQTLs are classified based on their genomic position relative to the target gene: cis-eQTLs are located near the gene (typically within 1 Mb), while trans-eQTLs are located on different chromosomes or far from the target gene. The primary goal of eQTL mapping is to explain the regulatory mechanisms linking genetic variations to complex traits or diseases.

Cellular Specificity in Genetic Regulation

Cell-type-specific eQTLs are genetic variants whose effects on gene expression are detectable only in certain cell types, even when those cell types coexist within the same tissue environment. This specificity arises from differences in cellular context, including:

- Cell-type-specific chromatin accessibility and epigenetic states

- Presence of cell-type-specific transcription factors

- Differences in signaling pathway activity

- Variation in cellular maturation or activation states

The biological significance of cell-type-specific eQTL effects lies in their ability to reveal the precise cellular contexts through which genetic variants influence disease risk, thereby providing critical insights for targeted therapeutic development.

Quantitative Evidence for Cell-Type-Specific eQTL Effects

Recent Single-Cell eQTL Studies

Table 1: Key Findings from Recent Single-Cell eQTL Studies Demonstrating Cell-Type-Specific Effects

| Study Focus | Sample Size | Cell Types Analyzed | Key Finding on Specificity | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HERV regulation in immune cells | 981 donors, 1.2M cells | 9 immune cell types from PBMCs | Identified 3,463 conditionally independent eQTLs linked to retroviral elements, majority showing cell-type-specific effects [30] | Nature Communications (2025) |

| Gastric cancer susceptibility | 203 individuals, 399,683 cells | 19 gastric cell subpopulations | 81% (6,909/8,498) of independent eQTLs exhibited cell-type-specific effects [16] | Cell Genomics (2025) |

| Immune cell eQTLs | Publicly available OneK1K dataset | PBMCs from healthy donors | HERV expression patterns showed markedly lower similarity across cell types compared to gene expression profiles [30] | Nature Communications (2025) |

Magnitude of Specificity Effects

The quantitative evidence from recent large-scale studies demonstrates the substantial proportion of eQTLs with cell-type-specific effects. In gastric tissue, Bian et al. (2025) discovered that the vast majority (81%) of independent eQTLs showed specificity for particular cell types [16]. Similarly, in immune cells, the regulation of human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs) was found to be highly cell-type-specific, with distinct genetic variants influencing HERV expression in different immune cell populations [30].

These findings highlight that cellular context dramatically shapes how genetic variants influence gene expression, with implications for understanding the mechanistic basis of disease associations. The cell-type-specific eQTLs identified in these studies were frequently linked to disease-associated genetic variants, providing functional interpretation for GWAS hits.

Experimental Protocols for Cell-Type-Specific eQTL Mapping

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing with Multiplexed Designs

Purpose: To capture gene expression heterogeneity across cell types while maintaining donor identity for genetic analyses.

Workflow:

Sample Preparation and Pooling

- Obtain fresh tissue samples (e.g., gastric mucosa, PBMCs) from genotyped donors

- Process tissues to single-cell suspensions using appropriate dissociation protocols

- Implement a pooled multiplexing strategy, labeling cells from individual donors with distinct barcodes (e.g., 203 individuals across 27 pools) [16]

- Include technical replicates (e.g., 30 replicates from 9 individuals) for quality control

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Generate scRNA-seq libraries using 3' or 5' counting methods (10X Genomics)

- Sequence to sufficient depth (typically 50,000 reads per cell)

- Include genotype-based sample demultiplexing to assign cells to individual donors

Quality Control and Filtering

- Remove doublets and low-quality cells using tools like Scrublet

- Apply stringent QC filters: minimum genes/cell, maximum mitochondrial percentage

- Retain only high-quality singlets for downstream analysis (e.g., 399,683 cells from 203 individuals) [16]

Cell-Type-Specific eQTL Mapping Analysis

Purpose: To identify genetic variants that regulate gene expression in specific cell types.

Methodology:

Cell Type Annotation

- Perform dimensionality reduction (PCA, UMAP) on filtered gene expression matrix

- Identify cell clusters using graph-based methods (Louvain, Leiden)

- Annotate cell types using canonical marker genes defined in previous studies [16]

- For immune cells: CD4+ T cells (CD4), CD8+ T cells (CD8), B cells (MS4A1), NK cells, monocytes

- For gastric epithelium: mucous neck cells (MUC6), pit cells (MUC5AC), chief cells (PGA4), parietal cells (ATP4A)

Expression Matrix Preparation

- For each cell type, create pseudobulk expression profiles by aggregating counts per donor

- Normalize expression data to account for technical covariates (sequencing depth, batch effects)

- Filter lowly expressed genes/HERVs (e.g., require expression in >20 cells) [30]

eQTL Mapping

- Perform genotyping quality control and imputation

- Test association between genetic variants and gene expression separately for each cell type

- Use linear models adjusting for relevant covariates (age, sex, genetic ancestry, technical factors)

- For cis-eQTL mapping, test variants within 1 Mb of gene transcription start site

- Apply multiple testing correction (Bonferroni or false discovery rate)

Specificity Assessment

- Compare eQTL effect sizes across cell types using statistical tests for heterogeneity

- Classify eQTLs as cell-type-specific when significant in only one cell type or showing significantly different effects across types

Integration with Disease Associations

Purpose: To connect cell-type-specific eQTLs with disease pathogenesis.

Approach:

Co-localization Analysis

- Test for shared causal variants between eQTL signals and GWAS risk loci

- Use statistical methods (e.g., COLOC) to calculate posterior probabilities of co-localization

- Identify cell types where disease-associated variants likely exert regulatory effects

Transcriptome-Wide Association Study (TWAS)

- Build genetic prediction models of gene expression using eQTL reference panels

- Test associations between predicted expression and disease risk

- Identify genes whose genetically regulated expression is associated with disease in specific cell types

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cell-Type-Specific eQTL Mapping

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-cell RNA-seq kits (10X Genomics) | Capturing transcriptome of individual cells | Profiling 399,683 gastric cells from 203 individuals [16] | Choose 3' vs 5' based on need for immune receptor sequencing |

| Cell hashing antibodies (TotalSeq) | Sample multiplexing by labeling cells from different donors | Processing 233 samples across 27 pools [16] | Enables dramatic cost reduction through sample pooling |

| Cell dissociation kits (tissue-specific) | Tissue processing to single-cell suspensions | Preparing PBMCs or gastric mucosa cells [30] [16] | Optimization needed to preserve RNA quality and cell viability |

| GENCODE annotations | Reference transcriptome for read alignment | Distinguishing independent HERV transcription from host genes [30] | Regular updates incorporate new gene models |

| UCSC Genome Browser annotations | Genomic element annotation | Obtaining HERV annotations (GRCh38/hg38) [30] | Includes repetitive elements not in standard gene annotations |

| CellRanger software | Processing scRNA-seq data | Aligning reads to combined gene-HERV reference [30] | Configure for unique mapping reads to handle repetitiveness |

Visualization and Data Interpretation

Analytical Workflow for Cell-Type-Specific eQTL Discovery

Interpretation Guidelines

When interpreting cell-type-specific eQTL results, several key considerations emerge:

Technical Artifacts vs. Biological Specificity: Ensure that cell-type-specific effects are not driven by differences in cell type abundance, power variations, or technical artifacts. Use balanced designs and include relevant covariates in statistical models.

Multiple Testing Burden: The number of statistical tests increases substantially when analyzing multiple cell types. Implement stringent correction methods while maintaining sensitivity to detect true effects.

Functional Validation: Prioritize cell-type-specific eQTLs for experimental follow-up based on strength of association, linkage to disease, and potential biological relevance. CRISPR-based editing in specific cell types can provide definitive evidence of causality.

Biological Mechanism: Explore potential mechanisms underlying specificity through integration with epigenomic data (ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq) from purified cell types, focusing on cell-type-specific transcription factor binding and chromatin accessibility.

Application to Disease Mechanism Elucidation

The power of cell-type-specific eQTL mapping lies in its ability to illuminate disease mechanisms. In gastric cancer, this approach identified 15 genes associated with GC risk through cell-type-specific expression, including MUC1 upregulation exclusively in parietal cells linked to decreased GC risk [16]. For autoimmune diseases, single-cell eQTL mapping of human endogenous retroviruses revealed these elements as important mediators of genetic effects in specific immune cell types [30].

These findings demonstrate how cell-type-specific eQTL analyses can pinpoint precise cellular contexts where disease-associated genetic variants operate, providing direct insights for therapeutic targeting and personalized medicine approaches. The integration of these regulatory maps with disease genetics continues to transform our understanding of complex trait architecture.

eQTL Mapping Workflows: From Data Processing to Advanced Models

Expression Quantitative Trait Locus (eQTL) mapping represents a powerful methodology that identifies genetic variants influencing gene expression levels, serving as a crucial bridge between genomic variation and phenotypic manifestation [19] [11]. This technique correlates two fundamental data types—genotype information (genetic variation) and expression data (molecular phenotype)—to elucidate how genetic differences regulate gene expression across individuals, tissues, and cell types [31]. The resulting insights are transforming our understanding of complex disease mechanisms, particularly for immune-mediated disorders, cancers, and other polygenic conditions [19] [32]. As single-cell technologies advance, eQTL mapping has expanded to reveal previously undetectable cell-type-specific regulatory effects, offering unprecedented resolution into the genetic architecture of gene regulation [17] [31]. This application note details the essential data components, processing methodologies, and analytical frameworks required for robust eQTL mapping, providing researchers with practical protocols for implementation within modern genetic research programs.

Core Data Components for eQTL Mapping

Successful eQTL mapping requires the integration of two primary data modalities: genotype data capturing genetic variation across individuals, and expression data quantifying transcriptional activity. The quality, scale, and processing of these datasets directly determine analytical power and resolution.

Table 1: Essential Genotype Data Components and Specifications

| Data Component | Description | Processing Requirements | Quality Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Variants | Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions/deletions (indels) from genome-wide arrays or sequencing [33] | Imputation using reference panels (e.g., 1000 Genomes), stringent quality control filters [33] | Call rate >98%, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium p > 1×10⁻⁶, minor allele frequency >1% |

| Genotype Format | Individual-level genetic data in PLINK, VCF, or BGEN formats with sample identifiers [33] | Phasing to determine haplotype structure, alignment to reference genome | Genotype concordance >99%, phasing accuracy >95% |

| Sample Metadata | Donor demographics, ancestry, technical batches, sample collection protocols [33] | Covariate adjustment for population stratification, batch effects | Complete phenotypic information, documented processing steps |

Table 2: Expression Data Modalities and Considerations

| Expression Data Type | Description | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk RNA-Sequencing | Gene expression measured from tissue homogenate or cell populations [33] | High sequencing depth, established protocols, cost-effective for large cohorts | Cellular heterogeneity masks cell-type-specific signals [17] |

| Single-Cell/Nucleus RNA-Seq | Expression profiling at individual cell resolution using cellular barcoding [17] [31] | Identifies cell-type-specific eQTLs, reveals rare cell population effects | Lower genes detected per cell, higher technical noise, increased cost [17] |

| Microarray Expression | Fluorescent hybridization-based expression quantification [33] | Lower cost, rapid processing, established normalization methods | Limited dynamic range, pre-defined gene set, lower sensitivity |

Experimental Design and Data Processing Workflows

Sample Collection and Study Design Considerations

eQTL mapping study designs fall into two primary categories: population-based studies sampling natural variation, and experimental crosses controlling genetic background [31]. Population studies typically involve hundreds to thousands of unrelated individuals, capturing natural genetic diversity but requiring careful control for population stratification [33]. Family-based or experimental cross designs reduce heterogeneity but may limit generalizability. Recent innovations include "cell village" approaches that pool genetically distinct cell lines for single-cell eQTL mapping, though resolution remains limited by donor number rather than cell count [31]. For disease-focused applications, sampling relevant tissues and cell types under appropriate conditions significantly increases detection of biologically meaningful eQTLs [32].

Genotype Processing Protocol

- Quality Control: Apply stringent filters to genetic variants: remove SNPs with call rate <98%, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium p < 1×10⁻⁶, and minor allele frequency <1% in the study population [33].

- Imputation: Perform genotype imputation using reference panels (e.g., 1000 Genomes Phase 3) to infer missing genotypes and increase variant resolution [33]. Use software such as Minimac4 or IMPUTE2.

- Phasing: Determine haplotype phases using tools like SHAPEIT or Eagle to reconstruct chromosome segments inherited from each parent.

- Population Stratification: Calculate principal components of genetic relationship matrix to correct for ancestry differences among samples.

Expression Data Processing Protocol

- RNA-Seq Alignment: Process raw sequencing reads through quality control (FastQC), adapter trimming, and alignment to reference transcriptome (STAR or HISAT2).

- Quantification: Generate gene-level counts using featureCounts or transcript-level estimates with salmon/kallisto.

- Normalization: Apply normalization methods appropriate for downstream eQTL mapping, such as TMM for bulk RNA-seq or specialized methods for single-cell data to address technical artifacts [33].

- Quality Assessment: Filter low-quality samples based on alignment rates, ribosomal RNA content, and expression correlation with other samples. Remove genes expressed in too few samples or cells.

eQTL Mapping Methodologies and Analysis

Statistical Framework and Implementation

The core statistical approach tests for association between each genetic variant and expression phenotype while controlling for potential confounders. The basic model can be represented as:

E = βG + ΣγᵢCᵢ + ε

Where E represents normalized expression, G is genotype dosage, β is the effect size of the eQTL, Cᵢ are covariates, and γᵢ their coefficients [17]. Covariate selection is critical and typically includes:

- Technical factors: sequencing batch, processing date, quality metrics

- Biological confounders: age, sex, ancestry principal components

- Expression-specific factors: cellular composition, RNA integrity, mitochondrial content

For single-cell eQTL mapping, pseudobulk approaches aggregate counts across cells for each donor and cell type before applying standard eQTL methods, while mixed models can directly incorporate the single-cell count structure [17].

Meta-Analysis Approaches for Multi-Study Integration

As sample size limitations constrain statistical power, particularly in single-cell studies, meta-analysis approaches that combine summary statistics across datasets have become essential [17]. Federated meta-analysis methods address privacy concerns by sharing only summary statistics rather than individual-level data.

Table 3: Weighting Strategies for eQTL Meta-Analysis

| Weighting Scheme | Application Context | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | Square root of cohort sample size [17] | Simple implementation, requires minimal information | Does not account for study-specific quality differences |

| Standard Error | Inverse variance weighting using effect size precision [17] | Optimal statistical properties when effects are consistent | Requires sharing standard errors, increasing data sharing burden |