mRNA vs Total RNA Sequencing: A Bulk RNA-seq Guide for Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on choosing between bulk mRNA and total RNA sequencing.

mRNA vs Total RNA Sequencing: A Bulk RNA-seq Guide for Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on choosing between bulk mRNA and total RNA sequencing. It covers foundational principles, methodological workflows, and application-specific selection criteria. The content addresses common experimental challenges, including sample size optimization and data analysis, and explores validation strategies through comparative analysis with single-cell techniques. By synthesizing current methodologies and market trends, this guide aims to inform robust experimental design and effective utilization of RNA-seq technologies in biomedical research.

Decoding the Transcriptome: Core Principles of mRNA and Total RNA Sequencing

In the field of genomics, the transcriptome represents the complete set of RNA transcripts produced by the genome at a specific time and under specific conditions [1]. Unlike the static genome, the transcriptome is dynamic, changing in response to developmental stages, environmental stimuli, and disease states, thus providing a snapshot of active biological processes [1] [2]. For researchers investigating gene expression in bulk tissues, two principal methodological approaches have emerged: coding mRNA sequencing and whole transcriptome (total RNA) sequencing. The choice between these strategies significantly influences the breadth of biological information that can be captured, the experimental design, and the interpretation of results [3] [4].

This technical guide examines the fundamental distinctions between these approaches, their appropriate applications in research and drug development, and provides a framework for selecting the optimal method based on specific research objectives. Understanding these technologies is crucial for designing experiments that can effectively answer specific biological questions, particularly in precision oncology, biomarker discovery, and therapeutic development [5] [6].

Core Technological Differences

The fundamental distinction between coding mRNA sequencing and whole transcriptome sequencing lies in the scope of RNA species captured during library preparation. This initial decision determines the landscape of biological information accessible in downstream analyses.

Capturing the Coding Transcriptome: mRNA Sequencing

mRNA sequencing (mRNA-Seq) employs a targeted strategy designed to enrich for messenger RNA, which constitutes only 3-7% of the total RNA in a typical mammalian cell [4] [7]. This method capitalizes on the polyadenylated (poly-A) tail that characterizes most mature eukaryotic mRNAs. During library preparation, oligo(dT) primers complementary to the poly-A tail are used to selectively reverse-transcribe these mRNAs into cDNA, effectively isolating them from the abundant non-polyadenylated RNA species [3] [8]. The primary advantage of this approach is its efficiency; by focusing sequencing resources on protein-coding transcripts, it provides superior depth for gene expression quantification while minimizing wasted reads on non-informative RNA types like ribosomal RNA (rRNA) [8] [4].

Capturing the Complete RNA Landscape: Total RNA Sequencing

Whole transcriptome sequencing (Total RNA-Seq) takes a comprehensive approach by aiming to sequence all RNA molecules, both coding and non-coding. Since ribosomal RNA can constitute 80-90% of the total RNA content, a critical preprocessing step involves the depletion of rRNA using sequence-specific probes, without distinguishing between polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated transcripts [9] [4]. This preservation of the entire RNA population enables researchers to investigate not only protein-coding genes but also a diverse array of non-coding RNAs, including long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs), and other regulatory RNA elements that lack poly-A tails [9]. This unbiased capture provides a systems-level view of transcriptional activity.

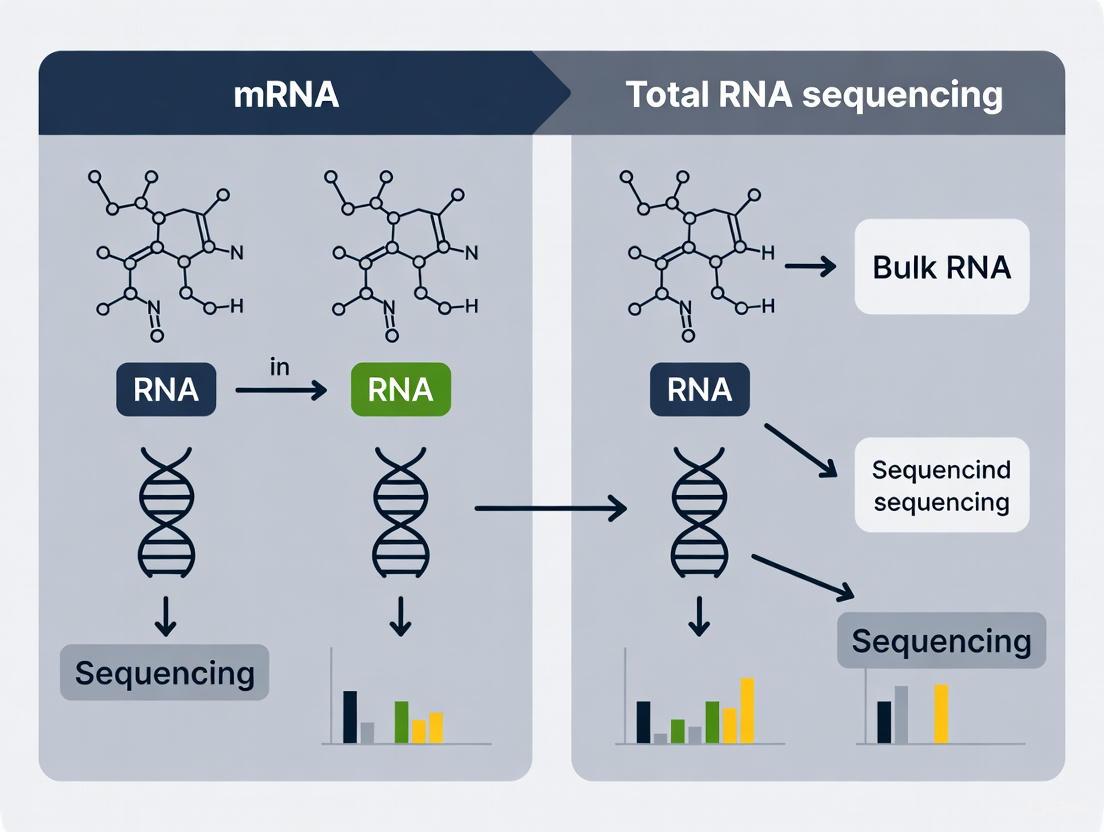

The workflow differences are illustrated in the following diagram:

Comparative Analysis of Methods

The choice between mRNA-Seq and Total RNA-Seq involves trade-offs between comprehensiveness, cost, sensitivity, and technical requirements. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of each method:

| Parameter | mRNA Sequencing | Whole Transcriptome Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Target RNA Species | Polyadenylated mRNA [3] [8] | All RNA species (coding and non-coding) except rRNA [9] [4] |

| Key Enrichment Method | Poly(A) selection [4] | Ribosomal RNA depletion [9] |

| Typical Read Depth | 25-50 million reads/sample [4] | 100-200 million reads/sample [4] |

| Ideal Applications | Differential gene expression, large-scale screening [3] | Novel transcript discovery, splicing analysis, non-coding RNA study [3] [9] |

| Strength | Cost-effective for coding transcriptome, higher depth for mRNA, simpler analysis [3] [4] | Comprehensive view, detects non-coding RNAs, not dependent on poly-A tails [9] |

| Limitation | Misses non-polyadenylated transcripts, 3' bias in some protocols [3] | Higher cost per sample, more complex data analysis, requires more input RNA [4] |

| Sample Quality Requirements | Requires high-quality RNA with intact 3' ends [3] | More tolerant of partial RNA degradation [3] |

Performance and Outcome Comparisons

Studies have directly compared these methodologies to evaluate their performance. Ma et al. (2019) found that while whole transcriptome sequencing detected more differentially expressed genes, 3' mRNA-Seq (a specific form of mRNA sequencing) was more effective at detecting short transcripts and provided highly similar biological conclusions in pathway analyses [3]. The reproducibility between biological replicates was similar for both methods [3].

When examining pathway analysis results, the top upregulated gene sets identified by whole transcriptome sequencing were consistently captured by 3' mRNA-Seq, though with some variation in statistical ranking beyond the very top hits [3]. This suggests that for many experimental goals, particularly those focused on identifying major pathway alterations rather than subtle, secondary effects, both methods can provide biologically congruent results.

Experimental Design and Protocol Guidance

mRNA Sequencing Workflow

The standard mRNA-Seq protocol involves several key stages:

RNA Extraction and QC: Isolate total RNA using appropriate methods. Assess RNA quality and integrity using methods such as RIN (RNA Integrity Number). A minimum of 25 ng of high-quality (RIN > 8) input RNA is recommended for standard kits [8].

Poly(A) Enrichment: Incubate total RNA with oligo(dT) magnetic beads to bind polyadenylated RNA. Wash away non-polyA RNA, then elute the enriched mRNA [8] [4].

Library Preparation: Fragment the purified mRNA and reverse transcribe using random primers. Synthesize the second strand. Ligate sequencing adapters, often including unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to correct for PCR amplification bias [8].

Sequencing: For differential expression analysis, single-read sequencing of 50-75 bp length at a depth of 25-50 million reads per sample is typically sufficient. For isoform identification, paired-end sequencing is recommended [6].

Total RNA Sequencing Workflow

The Total RNA-Seq protocol differs primarily in the enrichment strategy:

RNA Extraction and QC: Isolate total RNA. Quality control is critical, though this method is more tolerant of partially degraded samples [9].

rRNA Depletion: Use species-specific probes (e.g., Ribo-Zero, RiboMinus) to hybridize and remove abundant ribosomal RNAs. This preserves both polyA+ and polyA- transcripts, including non-coding RNAs [9] [4].

Library Preparation: Fragment the rRNA-depleted RNA and convert to cDNA using random primers. This approach generates reads distributed across the entire transcript length, enabling detection of splicing variants and structural alterations [9].

Sequencing: Requires deeper sequencing (100-200 million reads/sample) to adequately cover the diverse transcriptome. Paired-end sequencing is recommended for most applications to facilitate transcript assembly and variant detection [6] [4].

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points in selecting the appropriate methodology:

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Successful implementation of transcriptome studies requires careful selection of reagents and tools. The following table outlines key solutions for researchers:

| Reagent/Tool Category | Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| MRNA Enrichment Kits | Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads, Poly(A) Pull-down | Selectively isolates polyadenylated mRNA from total RNA, crucial for reducing non-coding background [8] [4] |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Ribo-Zero, RiboMinus | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA (constitutes 80-90% of total RNA) to enable sequencing of other RNA species [9] [4] |

| Library Prep Systems | Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep, Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep | Converts RNA to sequencing-ready libraries while preserving strand information; kit selection depends on RNA input type [9] [8] |

| RNA Integrity Tools | Bioanalyzer, TapeStation, RIN scoring | Assesses RNA quality and degradation level; critical for determining sample suitability and interpreting results [6] |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NextSeq 1000/2000, NovaSeq, MiSeq i100 | Determines throughput, read length, and cost; selection depends on project scale and required depth [8] |

| Analysis Pipelines | DRAGEN RNA Pipeline, Cell Ranger, STAR aligner | Performs alignment, quantification, and differential expression; some are optimized for specific applications [8] |

Applications in Research and Drug Development

The distinct capabilities of mRNA-Seq and Total RNA-Seq make them suitable for different phases of research and development:

Target Discovery and Validation

In early discovery phases, Total RNA-Seq provides a comprehensive landscape for identifying novel therapeutic targets, including non-coding RNAs with regulatory functions and alternative splice variants associated with disease states [9] [6]. This unbiased approach is particularly valuable in oncology, where it has enabled the discovery of novel gene fusions that drive cancer progression and can be targeted with specific inhibitors [6]. Once key targets are identified, mRNA-Seq offers a cost-effective method for validating expression patterns across large sample cohorts, providing the statistical power needed to establish clinical relevance [3] [10].

Biomarker Development

Transcriptome-based biomarkers have shown increasing utility in clinical oncology for disease classification, prognosis, and treatment prediction [5] [6]. While mRNA-Seq panels can effectively quantify established biomarker signatures, Total RNA-Seq enables the discovery of novel biomarker classes, including long non-coding RNAs and microRNAs that may offer improved diagnostic specificity [6]. For clinical implementation, focused mRNA-Seq panels (such as the FoundationOne Heme panel) provide a practical approach for detecting clinically actionable gene fusions and expression signatures in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples [6].

Toxicological and Mechanistic Studies

In toxicology and mechanistic pharmacology, Total RNA-Seq provides a systems-level view of drug responses, capturing both intended effects on target pathways and off-target impacts on diverse biological processes [2]. The ability to monitor non-coding RNAs adds valuable insight into regulatory mechanisms that may underlie toxicity or efficacy limitations. For high-throughput compound screening, mRNA-Seq offers a streamlined approach to rank candidates based on expression changes in key pathway genes, enabling prioritization for more comprehensive follow-up studies [3] [10].

The decision between a focused coding mRNA analysis and a comprehensive whole transcriptome approach represents a fundamental strategic choice in experimental design. mRNA sequencing provides an efficient, cost-effective method for quantitative gene expression analysis, particularly suited for large-scale studies where the primary interest lies in protein-coding genes. In contrast, whole transcriptome sequencing delivers a more complete picture of transcriptional activity, enabling discovery of non-coding RNAs, splice variants, and novel transcripts that may play critical roles in disease biology.

As transcriptomics continues to evolve, these technologies will remain essential tools for unraveling the complexity of biological systems, identifying therapeutic targets, and developing clinically actionable biomarkers. By aligning methodological choices with specific research objectives and practical constraints, scientists can maximize the insights gained from their transcriptomic studies and advance drug development efforts.

In bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) research, the choice between poly(A) enrichment and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion represents a fundamental methodological crossroads that directly defines the transcriptional landscape accessible for investigation. This decision is critical within the broader context of mRNA sequencing versus total RNA sequencing, as the library preparation method dictates which RNA species are captured and consequently shapes all downstream biological interpretations [11] [4]. Poly(A) enrichment selectively targets the 3' polyadenylated tails of mature messenger RNAs (mRNAs), while rRNA depletion employs removal strategies to reduce the overwhelming abundance of ribosomal RNA, thereby revealing the remainder of the transcriptome [12]. This technical guide provides an in-depth comparison of these two core approaches, detailing their mechanisms, experimental protocols, performance characteristics, and decision-making frameworks to enable researchers to align library construction with their specific scientific objectives.

Core Mechanistic Principles

Poly(A) Enrichment: Capturing Mature mRNA

Poly(A) enrichment is a targeted capture method that leverages the polyadenylated tails present on most eukaryotic mature mRNAs. The process utilizes oligo(dT) primers or probes covalently attached to magnetic beads that specifically hybridize to the poly(A) tail sequences [11] [12]. Following hybridization, magnetic separation allows for the selective isolation of polyadenylated RNAs while removing non-polyadenylated species, including rRNA, transfer RNA (tRNA), and various non-coding RNAs that lack poly(A) tails [4]. This mechanism effectively enriches for protein-coding transcripts, which typically constitute only 3-7% of the total RNA in mammalian cells [4].

A significant technical consideration is this method's inherent bias toward the 3' end of transcripts, which arises from the oligo(dT) priming location [11] [12]. This 3' bias becomes more pronounced with partially degraded RNA, such as that extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, where incomplete transcripts may only retain their 3' regions [11]. Additionally, capture efficiency may vary based on poly(A) tail length, potentially underrepresenting transcripts with shorter tails [11].

rRNA Depletion: Revealing the Broader Transcriptome

Ribosomal RNA depletion takes an alternative approach by directly removing the abundant rRNA molecules that constitute approximately 80-90% of total RNA [11] [13]. This method utilizes sequence-specific DNA or locked nucleic acid (LNA) probes that are complementary to conserved rRNA regions across multiple ribosomal subunits (e.g., 18S, 28S, 5S, 5.8S) [12] [13]. Following hybridization, probe-rRNA hybrids are removed through either RNase H digestion or affinity capture with streptavidin-coated magnetic beads [12]. This depletion strategy preserves both polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated RNA species, providing a broader view of the transcriptome that includes pre-mRNA, many long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), circular RNAs, and other non-coding RNA classes that would be excluded by poly(A) selection [11] [4].

A critical technical consideration for rRNA depletion is the requirement for species-specific probes, which necessitates verification of probe compatibility, particularly when working with non-model organisms [11] [12]. Incomplete rRNA removal can result in high residual rRNA content, significantly reducing the effective sequencing depth for target transcripts [13].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Detailed Workflow: Poly(A) Enrichment

The poly(A) enrichment protocol follows a series of standardized steps designed to selectively isolate polyadenylated RNA species. Most commercial kits, such as the Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA kit, utilize a robust methodology that has been extensively validated in comparative studies [14] [15].

Procedure:

- RNA Quality Assessment: Verify RNA integrity using metrics such as RNA Integrity Number (RIN) ≥ 8 or DV200 ≥ 50% to ensure suitability for poly(A) selection [11] [12].

- Oligo(dT) Hybridization: Incubate total RNA with magnetic beads conjugated to oligo(dT) primers. Typical input amounts range from 10 ng to 1 μg total RNA, with higher quality inputs yielding better enrichment [11] [14].

- Magnetic Separation: Place the reaction tube on a magnetic stand to separate bead-bound poly(A)+ RNA from the supernatant containing non-polyadenylated RNA.

- Wash Steps: Perform multiple wash steps with appropriate buffers to remove non-specifically bound RNA while maintaining poly(A)+ RNA binding.

- Elution: Release the enriched poly(A)+ RNA from the beads using elution buffer, typically with heat treatment.

- Library Construction: Proceed with standard RNA-Seq library preparation including fragmentation, reverse transcription, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification [14].

Critical Optimization Parameters:

- Beads-to-RNA Ratio: Studies demonstrate that increasing the oligo(dT) beads-to-RNA ratio significantly enhances enrichment efficiency. For yeast RNA, increasing the ratio from 13.3:1 to 50:1 reduced residual rRNA from 54.4% to 20% [13].

- Multiple Enrichment Rounds: Implementing two consecutive rounds of poly(A) selection can dramatically reduce rRNA contamination to less than 10% [13].

- RNA Input Quality: The method performs optimally with high-quality RNA; degraded samples yield strong 3' bias and underrepresentation of long transcripts [11] [12].

Detailed Workflow: rRNA Depletion

rRNA depletion protocols employ probe-based hybridization to selectively remove ribosomal RNA, preserving the diversity of the remaining transcriptome. Commercial kits such as the RiboMinus Transcriptome Isolation Kit use species-specific probes tailored to particular organisms [13].

Procedure:

- Probe Hybridization: Incubate total RNA with biotinylated DNA or LNA probes complementary to rRNA sequences (e.g., 18S, 28S, 5S, 5.8S). Input requirements are typically flexible, accommodating 100 ng to 1 μg of total RNA, including degraded samples [11] [12].

- rRNA-Probe Complex Removal: Add streptavidin-coated magnetic beads to bind the biotinylated probe-rRNA complexes, followed by magnetic separation to remove rRNA from the solution.

- Supernatant Collection: Recover the supernatant containing the rRNA-depleted RNA.

- RNA Purification: Concentrate and clean the rRNA-depleted RNA using ethanol precipitation or commercial cleanup kits.

- Library Construction: Proceed with standard RNA-Seq library preparation. The resulting libraries typically exhibit more uniform coverage across transcript bodies compared to poly(A)-enriched libraries [11].

Critical Optimization Parameters:

- Probe Specificity: Ensure probe sets match the target organism's rRNA sequences. Mismatched probes result in high residual rRNA levels, sometimes exceeding 40-50% of total reads [11] [13].

- Sample Compatibility: This method is particularly effective for prokaryotic samples, degraded RNA (FFPE, low RIN), and non-model organisms where poly(A) tails may be absent or variable [11] [12].

- Comprehensive Depletion: Verify that the probe set targets all abundant rRNA species, including 5S rRNA, which is sometimes overlooked in commercial kits [13].

Performance Comparison and Data Output Analysis

Direct comparative studies reveal significant differences in the performance characteristics and data output between poly(A) enrichment and rRNA depletion methods. These differences have profound implications for experimental design, sequencing depth requirements, and analytical approaches.

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Library Preparation Methods

| Performance Metric | Poly(A) Enrichment | rRNA Depletion |

|---|---|---|

| Usable exonic reads (blood) | 71% | 22% |

| Usable exonic reads (colon) | 70% | 46% |

| Extra reads needed for same exonic coverage | — | +220% (blood), +50% (colon) |

| Sequencing depth requirement | Lower (e.g., 13.5M reads for microarray-equivalent detection) | Higher (35-65M reads) |

| Transcript types captured | Mature, coding mRNAs, polyadenylated lncRNAs | Coding + noncoding (lncRNAs, snoRNAs, pre-mRNA) |

| 3'–5' coverage uniformity | Pronounced 3' bias | More uniform coverage |

| Performance with low-quality/FFPE samples | Reduced efficiency | Robust with degraded RNA |

| Residual rRNA content | Very low (<5%) | Variable (5-50%) depending on probe efficiency |

The data in Table 1 highlights a fundamental trade-off: poly(A) enrichment provides higher efficiency for capturing protein-coding sequences, while rRNA depletion offers broader transcriptome coverage at the cost of higher sequencing depth requirements. The substantial difference in usable exonic reads means that to achieve similar coverage of coding regions, rRNA depletion requires 50-220% more sequencing reads depending on tissue type, directly impacting project costs [11].

Impact on Transcriptome Analysis

Different library preparation methods can influence biological interpretations in transcriptome analysis:

Gene Expression Quantification: Studies comparing library preparation methods have found that while the lists of differentially expressed genes may vary between methods, the enriched biological pathways show strong concordance. One study found that a low-input, strand-specific rRNA depletion kit (SMARTer Stranded Total RNA-Seq Kit) identified 55% fewer differentially expressed genes compared to TruSeq poly(A) enrichment, but pathway enrichment conclusions remained consistent [15].

Alternative Splicing Analysis: The traditional TruSeq poly(A) method demonstrated superior performance for detecting splicing events, identifying approximately twice as many alternative splicing events (alternative 5' and 3' splicing sites, exon skipping, intron retention) compared to full-length cDNA methods [14]. The uniform coverage provided by rRNA depletion can be advantageous for splicing analysis despite lower overall detection rates.

Anti-sense Transcription: Strand-specific rRNA depletion protocols have shown enhanced sensitivity for detecting anti-sense transcription compared to poly(A) selection, with approximately 1.5% of gene-mapping reads corresponding to anti-sense strands versus 0.5% in TruSeq [15].

Decision Framework and Applications

Method Selection Guidelines

Choosing between poly(A) enrichment and rRNA depletion requires careful consideration of experimental goals, sample characteristics, and resource constraints. The following decision framework provides guidance for method selection:

Table 2: Decision Matrix for Library Preparation Method Selection

| Experimental Scenario | Recommended Method | Rationale | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eukaryotic RNA, high quality (RIN ≥8), coding mRNA focus | Poly(A) Enrichment | High exonic read yield (~70%), cost-effective for gene expression | Coverage skews to 3' end as RNA quality decreases |

| Degraded/FFPE samples, low RIN | rRNA Depletion | Tolerant of fragmentation, doesn't rely on intact poly(A) tails | Higher intronic/intergenic reads; verify probe matching |

| Non-coding RNA analysis (lncRNAs, snoRNAs, histone mRNAs) | rRNA Depletion | Captures both poly(A)+ and non-poly(A) species | Residual rRNA may reduce effective sequencing depth |

| Prokaryotic transcriptomics | rRNA Depletion | Poly(A) capture ineffective for bacterial mRNA | Requires species-specific rRNA probes |

| Alternative splicing/isoform analysis | rRNA Depletion | More uniform coverage across transcript body | Detects fewer splicing events than TruSeq [14] |

| Low-input samples (<10 ng total RNA) | Poly(A) Enrichment | More efficient with limited material, used in single-cell protocols | May require protocol modifications for ultralow inputs |

| Large-scale gene expression studies | Poly(A) Enrichment | Lower sequencing costs, simplified analysis | Limited to polyadenylated transcripts |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-Seq Library Preparation

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads | Selective capture of polyadenylated RNA via hybridization to poly(A) tails | Efficiency improves with increased beads-to-RNA ratio; optimal performance requires high-quality RNA [13] |

| Sequence-Specific rRNA Depletion Probes | Hybridize to ribosomal RNA for selective removal | Species-specific design critical; incomplete coverage leads to high residual rRNA [11] [13] |

| Strand-Specific Library Prep Kits | Maintain transcript orientation information during cDNA synthesis | Essential for identifying antisense transcription; multiple kits now compatible with both methods [15] |

| RNA Integrity Assessment Reagents | Evaluate RNA quality (RIN, DV200) | Critical for method selection; poly(A) enrichment requires RIN ≥8 for optimal performance [12] |

| RNase H Enzyme | Degrades RNA in DNA-RNA hybrids | Used in specific rRNA depletion protocols for targeted rRNA degradation [12] |

The strategic decision between poly(A) enrichment and rRNA depletion for RNA-Seq library preparation fundamentally shapes the scope and focus of transcriptomic investigations. Poly(A) enrichment offers an efficient, cost-effective approach for profiling mature mRNA expression in high-quality eukaryotic samples, while rRNA depletion provides a comprehensive view of the transcriptome that includes diverse non-coding RNA species and performs robustly with challenging sample types. The methodological choice should be guided by experimental objectives, sample characteristics, and resource constraints rather than technical convenience. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve, understanding these core differences empowers researchers to design more informed experiments, optimize resource allocation, and extract biologically meaningful insights from their transcriptomic data.

In the field of transcriptomics, the choice between mRNA sequencing and total RNA sequencing is foundational, dictating the scope, quality, and type of biological insights a study can yield. This decision hinges on a clear understanding of the quantitative and qualitative data each method produces. mRNA sequencing, often focusing on the 3' end of transcripts, is engineered for precise, cost-effective quantification of gene expression levels. In contrast, total RNA sequencing (or Whole Transcriptome Sequencing) provides a comprehensive, qualitative view of the entire transcriptome, enabling the discovery of novel isoforms, fusion genes, and non-coding RNA biology. This guide delineates the technical strengths of each approach within the context of bulk RNA research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the framework necessary to select the optimal method for their specific experimental goals.

Core Methodological Differences and Their Impact on Data

The nature of the data generated—whether richly quantitative or broadly qualitative—is fundamentally determined by the library preparation protocol.

mRNA Sequencing (3’ mRNA-Seq)

This method is designed for accurate digital counting of transcripts. Library preparation typically uses oligo(dT) primers to target the poly-A tails of protein-coding messenger RNAs (mRNA) [16] [17]. This results in sequencing reads that are clustered at the 3' end of transcripts. A key advantage is that it generates one fragment per transcript, which simplifies downstream quantification and eliminates the need for complex normalization based on transcript length [16]. This streamlined process is not only cost-effective but also robust for degraded samples, such as those from FFPE tissues, as it only requires the 3' end of the transcript to be intact [16].

Total RNA Sequencing (Whole Transcriptome Sequencing)

This approach aims to capture a complete picture of the transcriptional landscape. It starts with total RNA and uses random primers for cDNA synthesis, which facilitates an even coverage of the entire transcript length [16] [17]. To prevent ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which can constitute 80-90% of total RNA, from dominating the sequencing library, a critical depletion step is performed [4] [17]. This allows for the detection of both poly-adenylated and non-polyadenylated RNA species, including long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), microRNAs, and other non-coding RNAs [4]. The requirement for full-transcript coverage demands a higher sequencing depth than 3' mRNA-Seq to power qualitative discoveries [16] [17].

The logical relationship between methodological choices and their downstream consequences for data output can be visualized as follows:

Quantitative and Qualitative Data Outputs: A Detailed Comparison

The methodological divergence directly translates into distinct data outputs, each with unique strengths.

Quantitative Strengths of 3’ mRNA-Seq

- Accurate Gene Expression Quantification: By generating a single read count per transcript, 3' mRNA-Seq provides a direct digital measure of gene abundance that is not skewed by transcript length [16].

- Cost-Effectiveness for Large Studies: Due to its lower required sequencing depth (typically 1-5 million reads per sample), it is ideal for profiling large numbers of samples, such as in high-throughput drug screening or large cohort studies [16].

- Robustness with Challenging Samples: It performs reliably with partially degraded RNA (e.g., from FFPE samples) because its target region—the 3' end—is more likely to survive degradation [16] [17].

Qualitative Strengths of Total RNA-Seq

- Discovery of Novel Transcripts and Isoforms: Full-transcript coverage allows for the identification of novel splice variants, fusion genes, and untranslated regions (UTRs) [16] [18].

- Analysis of the Non-Coding Transcriptome: It is the only option for profiling non-coding RNAs (e.g., lncRNAs, miRNAs) that lack poly-A tails and are missed by standard mRNA-Seq [4] [17].

- Comprehensive Splicing Analysis: With reads spanning exon-intron boundaries, researchers can analyze alternative splicing events and allele-specific expression [16] [19].

Table 1: Method Selection Based on Research Objectives and Applications

| Research Objective | Recommended Method | Key Applications & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Gene Expression (DGE) | 3' mRNA-Seq | Cost-effective, accurate quantification for large numbers of samples; highly reproducible [16] [17]. |

| High-Throughput Screening | 3' mRNA-Seq | Streamlined workflow and lower per-sample sequencing cost enables profiling of thousands of samples [16]. |

| Transcript Isoform Discovery | Total RNA-Seq | Full-length transcript coverage is required to identify alternative splicing, novel isoforms, and fusion genes [16] [18]. |

| Non-Coding RNA Analysis | Total RNA-Seq | Detects all RNA types, including lncRNAs and miRNAs, which are often not polyadenylated [4] [17]. |

| Working with Degraded RNA | 3' mRNA-Seq | More tolerant of RNA degradation common in FFPE samples, as it only requires an intact 3' end [16]. |

Table 2: Technical and Practical Considerations

| Parameter | 3' mRNA-Seq | Total RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Types Captured | Protein-coding polyadenylated mRNA only [17] | All RNA types (coding and non-coding) after rRNA depletion [4] [17] |

| Typical Sequencing Depth | Low (e.g., 25-50 million reads/sample) [4] | High (e.g., 100-200 million reads/sample) [4] |

| Data Analysis Complexity | Lower (straightforward read counting) [16] | Higher (requires sophisticated alignment and isoform resolution) [16] |

| Project Cost (per sample) | Lower | Higher |

| Annotation Dependence | High (requires well-annotated 3' UTRs) [16] | Lower (can discover novel, unannotated features) [18] |

Experimental Protocols for Robust Data Generation

Protocol for 3’ mRNA-Seq Library Preparation and Analysis

This protocol is optimized for accurate gene expression quantification.

- RNA Extraction & QC: Extract total RNA using a silica-membrane column method. Assess RNA integrity and purity using an Agilent Bioanalyzer or similar system. For FFPE samples, use specialized extraction kits designed for cross-linked RNA [18].

- Poly-A Selection and Library Prep: Use magnetic oligo(dT) beads to selectively enrich for polyadenylated RNA. Reverse transcribe the purified mRNA using an oligo(dT) primer. The resulting cDNA is then fragmented, and sequencing adapters are ligated [16] [17].

- Sequencing: Sequence the libraries on an Illumina platform. A read depth of 25-50 million reads per sample is generally sufficient for most quantitative applications [4].

- Bioinformatic Quantification:

- Alignment: Map sequencing reads to a reference genome using a splice-aware aligner like STAR or HISAT2 [20] [21].

- Quantification: Use a tool like featureCounts or HTSeq to count the number of reads mapping to each gene's annotation [20]. Since each read originates from the 3' end, no length normalization is required, simplifying to a counts-per-gene table [16].

- Differential Expression: Input the raw count matrix into statistical tools like DESeq2 or edgeR to identify significantly differentially expressed genes between conditions [20].

Protocol for Total RNA-Seq Library Preparation and Analysis

This protocol is designed for comprehensive transcriptome characterization.

- RNA Extraction & QC: Follow the same rigorous extraction and QC steps as above. The integrity of the full transcript is more critical for this method.

- rRNA Depletion and Library Prep: Use commercial kits with probes complementary to rRNA species (e.g., RiboZero, RiboFree) to remove ribosomal RNA from the total RNA sample. The remaining RNA, enriched for mRNA and non-coding RNAs, is then reverse-transcribed using random hexamer primers. This ensures coverage across the entire transcript. Strand-specific library construction is highly recommended to determine the originating DNA strand [4] [17].

- Sequencing: Sequence the libraries to a higher depth, typically 100-200 million reads per sample, to ensure sufficient coverage for isoform-level analysis [4].

- Bioinformatic Analysis for Qualitative Discovery:

- Alignment and Assembly: Map reads with an aligner like STAR. Then, use a transcript assembler such as StringTie or Cufflinks to reconstruct transcripts from the aligned reads, which may reveal novel isoforms [20].

- Quantification and DE: Use tools like Cuffdiff or Salmon that can estimate abundance at the transcript level (e.g., in TPM - Transcripts Per Million) and perform differential expression analysis for isoforms [20].

- Splicing and Fusion Analysis: Employ specialized tools to detect alternative splicing events (e.g., rMATS) and gene fusions (e.g., STAR-Fusion, Arriba).

The workflow for RNA-seq data analysis, while varying in specifics between the two methods, follows a common conceptual pathway to transform raw sequencing data into biological insights, as outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA Sequencing

| Item | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads | Selectively binds to and purifies polyadenylated RNA from total RNA samples. | Essential for the initial enrichment step in 3' mRNA-Seq library preparation [17]. |

| Ribosomal RNA Depletion Probes | Probes that hybridize to and facilitate the removal of abundant rRNA. | Critical for total RNA-Seq to increase the fraction of informative sequencing reads from non-rRNA species [4] [17]. |

| Strand-Specific Library Prep Kit | Preserves the information about which DNA strand originated the RNA transcript. | Vital for total RNA-Seq to accurately annotate genes and distinguish overlapping transcripts on opposite strands [4]. |

| RNA Integrity Check Kits | Provides a quantitative measure of RNA degradation. | Used in QC for both methods; crucial for determining the suitability of a sample for total RNA-Seq [21] [18]. |

| Universal Human Reference RNA | A standardized control RNA sample from a pool of cell lines. | Serves as a benchmark for normalizing experiments and assessing technical performance across runs [21]. |

The choice between mRNA and total RNA sequencing is not a matter of one method being superior to the other, but of strategic alignment with research objectives. 3' mRNA-Seq is the undisputed champion for quantitative analysis, offering precision, robustness, and efficiency for focused questions in differential gene expression, especially in large-scale or pharmacogenomic studies. Total RNA-Seq is the premier tool for qualitative discovery, providing an unbiased, genome-wide lens to explore the full complexity of the transcriptome, from novel isoforms to the regulatory world of non-coding RNAs. By understanding the intrinsic strengths and data outputs of each method, researchers can make an informed decision that optimally leverages these powerful technologies to advance scientific discovery and drug development.

In the context of a broader thesis on mRNA versus total RNA sequencing for bulk research, understanding which RNA species are captured is fundamental to experimental design. While mRNA sequencing specifically targets protein-coding transcripts through poly-A enrichment, total RNA sequencing provides a more comprehensive view of the transcriptome by capturing both coding and non-coding RNA species. The key RNA molecules researchers can expect to capture include messenger RNA (mRNA), long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), microRNA (miRNA), and various other non-coding RNAs, each with distinct biological functions and methodological considerations for sequencing. The choice between these approaches significantly impacts the scope of biological insights, particularly in disease research and drug development where non-coding RNAs are increasingly recognized as critical regulators [22] [23] [24].

RNA Species: Characteristics and Research Applications

Table 1: Key RNA Species in Sequencing Research

| RNA Type | Size Range | Primary Function | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA | Varies (typically 0.5-10+ kb) | Protein coding; translates genetic information into proteins | Gene expression studies, biomarker discovery, therapeutic target identification [22] |

| lncRNA | >200 nucleotides | Epigenetic regulation, transcriptional control, cellular differentiation | Cancer diagnostics, prognostic modeling, therapeutic development [23] [25] |

| miRNA | ~22 nucleotides | Post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression via mRNA degradation or translational repression | Biomarker discovery, therapeutic applications, regulatory network analysis [26] [27] |

| Other ncRNAs | Varies | Diverse regulatory functions including splicing, translation, and epigenetic modifications | Cellular mechanism studies, diagnostic applications [24] |

Market Outlook and Research Emphasis

The research tools and services market for these RNA species reflects their growing importance in biomedical research. The mRNA sequencing market is projected to grow from USD 3,965.8 million in 2025 to USD 8,561.7 million by 2035, at a CAGR of 8.0% [22]. The lncRNA sequencing market, while smaller at approximately $1.5 billion in 2025, is projected to expand at a significantly faster CAGR of 15% from 2025 to 2033, highlighting the increasing research focus on this RNA class [23]. Similarly, the miRNA tools and services market is expected to grow from USD 455.70 million in 2024 to USD 2,432.31 million by 2034, at a remarkable CAGR of 18.23% [27].

Methodological Approaches: Capture, Enrichment, and Sequencing

Experimental Workflows for RNA Species Capture

Table 2: Methodological Comparison for RNA Species Capture in Bulk Sequencing

| Methodology | Target RNA Species | Key Steps | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA Sequencing | Protein-coding transcripts | Poly-A selection, library preparation, sequencing (typically Illumina) | High specificity for coding transcripts, well-established protocols | Misses non-polyadenylated RNAs, biased toward 3' end [22] |

| Total RNA Sequencing | Comprehensive transcriptome (including rRNA, lncRNA, other ncRNAs) | rRNA depletion, library preparation, sequencing | Captures coding and non-coding transcripts, more complete transcriptome view | Higher proportion of non-informative reads (e.g., rRNA) [24] |

| Specialized miRNA Sequencing | Small RNAs (~22 nt miRNAs) | Size selection, adapter ligation, library preparation | Optimized for small RNA detection, high sensitivity for miRNAs | Specialized protocols required, may miss larger RNAs [26] |

Figure 1: RNA Capture Methods Workflow - Different enrichment strategies target specific RNA classes from total RNA samples.

Advanced Integrated Approaches

Contemporary research increasingly employs integrated methodologies that combine bulk and single-cell approaches. For instance, studies on bladder cancer and neuroblastoma have demonstrated the power of combining bulk RNA sequencing with single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to identify key prognostic genes and immune microenvironment factors [28] [25]. These integrated approaches allow researchers to contextualize population-level findings with cellular resolution, particularly valuable for understanding tumor heterogeneity and rare cell populations.

Specialized tools have been developed to facilitate these analyses. The inDAGO platform provides a user-friendly interface for dual RNA-seq analysis, enabling simultaneous profiling of protein-coding and non-coding transcripts from two interacting organisms, which is particularly valuable in host-pathogen or cross-kingdom interaction studies [29]. Similarly, the Scan framework incorporates 27 network inference methods to identify sample-specific miRNA regulation from both bulk and single-cell RNA-sequencing data, addressing the critical challenge of biological heterogeneity in regulatory network analysis [30].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Reagents for RNA Sequencing Studies

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina Nova 6000, 10x Genomics Chromium | High-throughput sequencing, single-cell analysis | Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) dominates mRNA sequencing due to accuracy and scalability [22] |

| Library Prep Kits | CleanTag adapters, Rsubread, Smart-seq | RNA library construction, adapter ligation | CleanTag adapters reduce adapter-dimer formation in miRNA sequencing [26] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Seurat, inDAGO, Scan, DoubletFinder | Data processing, quality control, differential expression | inDAGO enables dual RNA-seq analysis without programming expertise [29] [30] |

| Specialized Algorithms | Hermes, Cupid, LongHorn, BigHorn | ncRNA target prediction, network analysis | Cupid improves miRNA target prediction accuracy using competition principles [24] |

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Networks in RNA Biology

Figure 2: RNA Regulatory Networks - Complex interactions between different RNA species create layered gene regulatory systems.

The regulatory relationships between different RNA species create sophisticated networks that maintain cellular homeostasis. miRNAs regulate gene expression by binding to target mRNAs, leading to translational repression or degradation [26] [30]. lncRNAs can function as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) that "sponge" miRNAs, thereby preventing them from interacting with their mRNA targets [24]. This ceRNA network, as mapped by algorithms like Hermes, represents a regulatory layer as extensive as transcription factor networks, facilitating crosstalk between key driver genes and pathways in cancers [24].

Advanced algorithms have been developed to decipher these complex relationships. The Cupid algorithm enhances miRNA target prediction accuracy by leveraging the principle that competition among targets for shared miRNAs provides stronger evidence for genuine interactions [24]. LongHorn expands target prediction to lncRNAs by integrating four established regulatory mechanisms (guide, co-factor, decoy, and switch) from thousands of patient profiles [24]. These computational tools are essential for moving from simply identifying RNA species to understanding their functional roles in biological systems and disease pathologies.

Application in Disease Research and Therapeutic Development

The capture and analysis of different RNA species has profound implications for disease research and drug development. In cancer biology, integrated analysis of mRNA and non-coding RNA profiles has enabled the development of prognostic models with significant clinical potential. For instance, in neuroblastoma research, cuproptosis-related lncRNAs (CRlncRNAs) have been used to construct risk models that significantly improve patient stratification accuracy [25]. Similarly, in prostate cancer, immune-related lncRNA and mRNA signatures (ILMS) have demonstrated superior ability to predict clinical outcomes and immunotherapeutic response compared to 70 other published signatures [31].

The therapeutic applications of RNA research are expanding rapidly. The success of mRNA vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated investment in mRNA-based therapeutics, with applications expanding to oncology, rare diseases, and infectious diseases [22]. Beyond mRNA, research has identified lncRNAs that modulate the DNA damage response pathway in cancer cells, with promising applications in synthetic lethality approaches for pediatric sarcoma patients [24]. By silencing specific lncRNAs in patients with mutations in DNA damage response proteins, researchers aim to increase tumor sensitivity to radiotherapy while reducing toxicity.

Technical Challenges and Emerging Solutions

Despite significant advances, technical challenges remain in the comprehensive capture and analysis of diverse RNA species. miRNA sequencing faces particular difficulties including adapter-dimer formation, limited input material, and technical biases during reverse transcription and amplification [26]. Single-cell RNA sequencing, while powerful for exploring cellular heterogeneity, contends with high costs, technical complexity, limited data quality, high dropout rates, and fewer genes detected per cell [24].

Emerging methodologies are addressing these limitations. For miRNA sequencing, optimized protocols like Sandberg Protocol II with CleanTag adapters suppress adapter-dimer formation and improve reproducibility [26]. The half-cell genomics approach enables simultaneous co-sequencing of miRNAs and mRNAs from the same single cell by splitting lysate into two fractions, providing direct insight into post-transcriptional regulation [26]. Parallel single-cell small RNA and mRNA co-profiling methods like PSCSR-seq V2 allow high-throughput co-profiling of miRNAs alongside rich mRNA information from thousands of individual cells [26].

The field is also advancing through the integration of artificial intelligence and multi-omics approaches. AI algorithms are being incorporated into miRNA analysis tools to enhance predictive capabilities and provide deeper insights into miRNA functions and interactions [27]. The integration of miRNA data with other omics layers, such as transcriptomics and proteomics, offers a more holistic perspective on molecular interactions and biological networks [27]. These technological innovations are critical for overcoming current limitations and fully realizing the potential of RNA sequencing in both basic research and clinical applications.

From Lab to Insight: Workflow, Applications, and Strategic Selection

The journey of RNA sequencing begins with the isolation of high-quality RNA, a step where methodological choices immediately begin to diverge based on research goals. RNA extraction represents a fundamental point of differentiation in sequencing workflows, as the method employed can significantly influence downstream results. Studies have demonstrated that different RNA isolation techniques can preferentially extract certain RNA species, potentially introducing batch effects in meta-analyses [32]. For instance, classic hot acid phenol extraction has been shown to better solubilize membrane-associated mRNAs compared to commercial column-based kits, which could masquerade as differential expression in downstream analyses [32]. This technical variability underscores the importance of consistent RNA isolation methods, particularly when comparing datasets across different experiments or laboratories.

The quality and integrity of extracted RNA must be rigorously assessed before proceeding to library preparation, with methods and metrics tailored to the sample type. For challenging sample types like formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, which yield fragmented and chemically modified RNA, quality assessment through metrics such as DV200 (percentage of RNA fragments >200 nucleotides) becomes crucial [33]. For standard fresh-frozen samples, RNA Integrity Number (RIN) provides a reliable quality measure, with values above 8.0 generally recommended for most sequencing applications [32].

Library Preparation Fundamentals: Poly(A) Enrichment Versus Ribosomal RNA Depletion

Following RNA extraction, library preparation constitutes the most substantial point of divergence between mRNA and total RNA sequencing workflows. This critical process determines which RNA species will be captured and sequenced, fundamentally shaping the biological questions that can be addressed.

Poly(A) Enrichment for mRNA Sequencing utilizes oligo(dT) beads or primers to selectively target the polyadenylated tails of messenger RNAs [4] [3]. This approach efficiently captures mature protein-coding transcripts while excluding non-polyadenylated RNA species. The process is highly specific to eukaryotic mRNA due to their poly(A) tails, making it unsuitable for prokaryotic studies where most transcripts lack this feature. A significant advantage of this method is its automatic removal of ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which constitutes 80-90% of total RNA, without requiring additional depletion steps [4]. This efficiency allows for deeper sequencing of coding regions with fewer total reads, typically requiring only 25-50 million reads per sample compared to 100-200 million for total RNA-seq [4].

Ribosomal RNA Depletion for Total RNA Sequencing employs probe-based methods to remove abundant ribosomal RNAs, preserving both coding and non-coding RNA species [4] [18]. This comprehensive approach enables researchers to investigate diverse RNA populations including transfer RNAs (tRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and other non-polyadenylated transcripts [4]. The rRNA depletion strategy is particularly valuable for exploring regulatory RNAs, studying prokaryotic transcriptomes, or investigating samples where RNA degradation may have compromised poly(A) tails, such as in archival FFPE specimens [3]. Modern commercial kits for total RNA sequencing, such as the Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep Ligation with Ribo-Zero Plus and TaKaRa SMARTer Stranded Total RNA-Seq Kit, have been optimized to effectively minimize ribosomal RNA content to less than 1% in fresh samples, though performance may vary with degraded samples [33].

Table 1: Key Differences Between mRNA-seq and Total RNA-seq Library Preparation

| Parameter | mRNA Sequencing | Total RNA Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Target RNA Species | Polyadenylated mRNA only | All RNA species except rRNA |

| Enrichment Method | Poly(A) selection using oligo(dT) | Ribosomal RNA depletion |

| Suitable for Prokaryotes | No | Yes |

| Typical Sequencing Depth | 25-50 million reads/sample [4] | 100-200 million reads/sample [4] |

| Captures Non-coding RNAs | Limited | Comprehensive (lncRNAs, miRNAs, etc.) |

| Cost Considerations | Lower per-sample sequencing costs | Higher per-sample sequencing costs |

Experimental Design and Workflow Selection Criteria

Choosing between mRNA and total RNA sequencing requires careful consideration of multiple experimental factors. The decision tree below illustrates the key decision points for selecting the appropriate workflow:

Beyond the primary considerations illustrated above, sample-specific factors further guide method selection. For projects with limited starting material, mRNA-seq often provides better sensitivity, as it focuses sequencing power on a smaller fraction of the transcriptome [4]. When studying archival FFPE samples, 3' mRNA-seq methods that target the region around poly(A) tails can be more robust despite RNA fragmentation, though both approaches can be adapted with specialized kits [33] [3]. The choice of library preparation method also affects the utility of different RNA quality assessment metrics—while RIN values are broadly applicable, DV200 may better predict performance with degraded samples [33].

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Performance

Direct comparisons of library preparation methods reveal important performance differences that impact data quality and experimental outcomes. A comprehensive evaluation of RNA-seq methods compared traditional approaches (TruSeq) with full-length double-stranded cDNA methods (SMARTer and TeloPrime), finding that the traditional method detected approximately twice as many expressed genes and splicing events as TeloPrime, with stronger correlation between TruSeq and SMARTer [34]. This demonstrates how the fundamental chemistry of library preparation influences gene detection sensitivity.

For FFPE samples, recent comparisons show that specialized kits can maintain performance with significantly reduced input requirements. The TaKaRa SMARTer Stranded Total RNA-Seq Kit v2 achieved comparable gene expression quantification to the Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep Ligation with Ribo-Zero Plus despite requiring 20-fold less RNA input, a crucial advantage for limited clinical samples [33]. Both kits generated data with high concordance in differential expression analysis (83.6-91.7% overlap) and pathway enrichment results, though with differences in ribosomal RNA content and intronic mapping rates [33].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of RNA-seq Library Preparation Methods

| Performance Metric | Traditional mRNA-seq (TruSeq) | Full-length cDNA Methods (SMARTer) | 3' mRNA-seq (QuantSeq) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Detection Sensitivity | High [34] | Moderate [34] | Moderate for 3' ends [3] |

| Coverage Uniformity | Uniform across transcript [34] | More uniform coverage [34] | Focused on 3' end [3] |

| Expression Quantification Accuracy | High correlation with standards [34] | Good correlation with TruSeq [34] | Good for gene-level [3] |

| Alternative Splicing Detection | Highest detection rate [34] | Moderate detection rate [34] | Limited by 3' bias [3] |

| Recommended Applications | Comprehensive transcriptome analysis, splicing studies [34] | Full-length transcript characterization | High-throughput expression profiling, degraded samples [3] |

The choice between methods also significantly impacts cost structure and experimental efficiency. While total RNA-seq provides more comprehensive transcriptome coverage, it requires deeper sequencing (typically 100-200 million reads per sample) to adequately capture diverse RNA species, increasing per-sample costs [4]. In contrast, mRNA-seq focusing on polyadenylated transcripts typically requires only 25-50 million reads per sample, making it more cost-effective for large-scale gene expression studies [4]. This efficiency enables researchers to process more samples within the same budget, increasing statistical power for differential expression analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Successful implementation of RNA sequencing workflows requires careful selection of laboratory methods and reagents. The following table summarizes key solutions used in the featured experiments and their applications:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for RNA Sequencing Workflows

| Reagent/Kit | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep with Ribo-Zero Plus [33] | rRNA depletion for total RNA-seq | FFPE and fresh frozen samples | Effective rRNA removal (<1% rRNA), preserves strand information |

| TaKaRa SMARTer Stranded Total RNA-Seq Kit v2 [33] | rRNA depletion for total RNA-seq | Low-input samples (20-fold less input) | Low RNA input requirement, maintains expression accuracy |

| 10x Genomics Chromium Single Cell Platform [35] | Single-cell partitioning and barcoding | Single-cell RNA sequencing | High-throughput cell barcoding, microfluidic partitioning |

| Lexogen QuantSeq 3' mRNA-Seq [3] | 3' end mRNA sequencing | High-throughput expression profiling | Low sequencing depth requirements, cost-effective |

| TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit [34] | Poly(A) enrichment for mRNA sequencing | Comprehensive transcriptome analysis | High gene detection sensitivity, optimal for splicing analysis |

| Hot Acid Phenol RNA Extraction [32] | Total RNA isolation | Yeast and microbial samples | Enhanced recovery of membrane-associated transcripts |

The optimal RNA sequencing workflow depends on a balanced consideration of research objectives, sample characteristics, and practical constraints. For research focused exclusively on protein-coding gene expression with limited samples or budget, mRNA sequencing with poly(A) enrichment provides a cost-effective solution with streamlined data analysis [4] [3]. When comprehensive transcriptome characterization is required—including non-coding RNAs, prokaryotic samples, or instances where poly(A) tails may be compromised—total RNA sequencing with ribosomal depletion offers the necessary breadth despite higher sequencing costs [4] [18].

Emerging methodologies continue to expand experimental possibilities. Single-cell RNA sequencing technologies, such as the 10x Genomics platform, now enable researchers to profile transcriptional heterogeneity at unprecedented resolution, complementing bulk approaches that provide population-level insights [35] [5] [10]. For specialized applications involving degraded samples like FFPE tissues, targeted methods such as 3' mRNA-seq offer robust alternatives to standard protocols [33] [3]. By carefully matching methodological approaches to biological questions, researchers can design RNA sequencing workflows that maximize insights while optimizing resource utilization.

The foundational choice between messenger RNA sequencing (mRNA-Seq) and total RNA sequencing (total RNA-Seq) is a critical determinant of success in transcriptomic studies. Within the context of bulk RNA sequencing research, this decision dictates the scope, depth, and biological applicability of the findings. mRNA-Seq, which focuses on polyadenylated (poly(A)) transcripts, provides a cost-effective method for profiling protein-coding genes [4]. In contrast, total RNA-Seq offers a comprehensive landscape of the transcriptome by capturing both coding and non-coding RNA species, albeit at a higher cost and with greater computational demands [4] [3]. This technical guide provides an in-depth comparison of these methodologies, framing them against specific research applications: gene expression quantification, isoform detection, and novel transcript discovery. We synthesize current protocols, data analysis tools, and experimental design considerations to empower researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the optimal strategy for their investigative goals.

Core Technology Comparison: mRNA-Seq vs. Total RNA-Seq

The fundamental difference between these two bulk RNA-Seq approaches lies in the initial steps of library preparation, which dictate the subset of RNA molecules that will be sequenced.

mRNA-Seq utilizes poly(A) enrichment to selectively capture RNA molecules with poly(A) tails. This primarily targets messenger RNAs (mRNAs) but will also capture other polyadenylated non-coding RNAs. This method effectively excludes ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which constitutes 80-90% of total RNA, without the need for a specific depletion step [4]. This makes it highly efficient for focusing on the protein-coding transcriptome.

Total RNA-Seq (also referred to as Whole Transcriptome Sequencing) employs rRNA depletion to remove the abundant ribosomal RNA components. This retains not only mRNAs but also a vast array of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) that lack poly(A) tails, such as long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs), and transfer RNAs (tRNAs) [4] [3].

Table 1: Decision Framework for Selecting Between mRNA-Seq and Total RNA-Seq

| Application Factor | Choose mRNA-Seq when... | Choose Total RNA-Seq when... |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Research Goal | Quantifying gene expression of protein-coding genes [4] [3] | Discovering novel non-coding RNAs, fusion genes, or performing global transcriptome analysis [4] [3] |

| Transcript Type of Interest | Focus is exclusively on poly(A)+ transcripts (mRNAs) [4] | Interest includes non-polyadenylated RNAs (e.g., many lncRNAs, pre-mRNAs) [4] [3] |

| Sample Input Material | Starting material is limited (requires less input) [4] | Sufficient starting material is available [4] |

| Project Budget | Budget is constrained; requires lower sequencing depth (25-50 million reads/sample) [4] | Budget allows for higher sequencing depth (100-200 million reads/sample) [4] |

| Sample Quality | Working with degraded samples (e.g., FFPE) where 3' ends are preserved [3] | RNA is intact, allowing for full-transcript coverage [4] |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key procedural divergences between these two primary approaches to bulk RNA sequencing:

Application 1: Gene Expression Quantification

For the precise quantification of gene expression levels, particularly in large-scale studies, mRNA-Seq is often the preferred and most cost-effective method [4] [3]. Its efficiency stems from concentrating sequencing reads on the biologically informative protein-coding transcriptome, which represents only 3-7% of the mammalian transcriptome [4]. This allows for robust differential gene expression analysis with a lower sequencing depth (typically 25-50 million reads per sample) compared to total RNA-Seq [4].

A specialized and highly efficient variant for gene expression counting is 3' mRNA-Seq (e.g., QuantSeq). This method generates libraries by priming directly from the 3' end of poly(A) RNAs, localizing all reads to the 3' untranslated region (UTR) [3]. This provides a single fragment per transcript, simplifying data analysis to straightforward read counting without the need for complex normalization for transcript length and concentration. It is ideal for high-throughput screening of many samples and is robust for degraded material like FFPE samples [3].

Table 2: Gene Expression Quantification Method Profiles

| Method | Key Principle | Typical Reads/Sample | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard mRNA-Seq | Poly(A) enrichment captures full-length transcripts [4] | 25-50 million [4] | Provides full-transcript information; standard for DE analysis [4] | Less efficient than 3' mRNA-Seq for pure counting [3] |

| 3' mRNA-Seq | Oligo(dT) priming at 3' UTR; one fragment per transcript [3] | 1-5 million [3] | Cost-effective; high-throughput; simple analysis; works on degraded RNA [3] | Lacks information on alternative splicing or 5' ends [3] |

| Total RNA-Seq | rRNA depletion preserves all RNA classes [4] | 100-200 million [4] | Can correlate mRNA with non-coding RNA expression [4] | Higher cost; reads "wasted" on rRNAs if not fully depleted [4] |

Studies comparing 3' mRNA-Seq to whole transcriptome methods have found that while the latter detects a higher absolute number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs), the biological conclusions at the level of pathway and gene set enrichment are highly concordant. For instance, in a study of murine livers under a high-iron diet, the top upregulated gene sets (e.g., "Response of EIF2AK1 to Heme Deficiency") were consistently ranked as the most significant by both methods, confirming that 3' mRNA-Seq reliably captures key biological signals [3].

Application 2: Isoform Detection and Alternative Splicing

For the analysis of alternative splicing and transcript isoform diversity, Total RNA-Seq with long-read sequencing technologies is superior. Short-read sequencing, while accurate, struggles to unambiguously assign exons to the same transcript due to a lack of long-range connectivity information [36] [37]. Long-read sequencing (LRS) technologies, such as those from Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio), sequence entire RNA molecules in a single read, enabling direct and precise observation of full-length transcript isoforms [36] [37].

The power of this approach is exemplified in neuropsychiatric research. A 2025 study profiling 31 risk genes in the human brain using nanopore amplicon sequencing identified 363 novel RNA isoforms and 28 novel exons. In genes like ATG13 and GATAD2A, the majority of expression was derived from previously undiscovered isoforms, dramatically altering the understanding of their genomic structure and potential protein products [37].

Experimental Protocol: Long-Read Isoform Discovery

A detailed methodology for long-read isoform discovery, as applied to human brain samples, involves the following steps [36] [37]:

- Sample Acquisition and RNA Extraction: Obtain high-quality tissue samples (e.g., from biobanks like GTEx). For brain studies, regions of interest may include the cerebellar hemisphere, frontal cortex, and putamen. Extract total RNA using a dedicated kit (e.g., Qiagen PAXgene Tissue miRNA kit) [36].

- Library Preparation for Long-Read Sequencing: Reverse-transcribe the isolated total RNA into cDNA. For comprehensive coverage, use a cDNA-PCR protocol. This is compatible with platforms like ONT MinION and GridION.

- Targeted Amplicon Sequencing (for deep gene profiling): Design primers to cover the full coding region of target genes, from the first to the last exon. For genes with complex alternative starts/ends, use multiple primer sets.

- Two-Pass Read Alignment: Align base-called reads to the reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) using a specialized aligner like Minimap2. A two-pass approach is recommended:

- First Pass: Perform initial alignment and extract splice junctions.

- Junction Filtering: Score junctions using a tool like 2passtools and filter low-confidence junctions based on metrics from a machine learning model.

- Second Pass: Re-align reads using the filtered junction list to guide alignment, significantly improving accuracy [36].

- Transcriptome Assembly and Quantification: Process the aligned reads through a specialized isoform discovery tool. The following diagram illustrates the bioinformatic pipeline for this critical step.

Key tools for this assembly step include Bambu [36] and IsoLamp, a newer pipeline optimized for amplicon sequencing which has demonstrated high precision and recall in benchmarking studies [37].

Application 3: Novel Transcript Discovery

The discovery of entirely unannotated transcripts—including novel protein-coding genes and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs)—demands the most comprehensive approach: Total RNA-Seq combined with long-read sequencing and sophisticated bioinformatic pipelines [36]. This strategy is crucial because novel transcripts, by definition, are absent from standard poly(A) enrichment-based annotations, and their full-length structure cannot be resolved by short reads.

A landmark 2025 study utilized this approach on human brain tissues, employing three separate bioinformatic tools to analyze long-read data from eight cerebellar hemisphere, five frontal cortex, and six putamen replicates [36]. By taking the consensus across tools, the study curated a high-confidence set of 170 novel RNA isoforms, consisting of 104 novel mRNAs and 66 novel lncRNAs. A notable finding was the tissue-specific expression of a novel lncRNA, BambuTx1299, which was predominantly expressed in the cerebellar hemisphere (mean CPM of 5.979) [36]. This highlights how total RNA-Seq can uncover novel regulatory elements with potential tissue-specific functions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced RNA Sequencing

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| PAXgene Tissue Kit | Stabilizes RNA in tissue samples immediately upon collection, preserving the in vivo transcriptome profile for later analysis [36]. | PreAnalytiX [36] |

| Total RNA Extraction Kit | Isolates the complete RNA population, including coding, non-coding, and ribosomal RNA, for total RNA-Seq. | Qiagen PAXgene Tissue miRNA kit [36] |

| rRNA Depletion Probes | Selectively removes abundant ribosomal RNA from a total RNA sample, enriching for informative transcripts prior to library prep. | Used in total RNA-Seq workflows [4] [3] |

| Oligo(dT) Beads | Enriches for polyadenylated RNA molecules by binding to their poly(A) tails; core of mRNA-Seq protocols. | Used in mRNA-Seq and 3' mRNA-Seq workflows [4] [3] |

| cDNA-PCR Kit (ONT) | Prepares sequencing-ready libraries from RNA for Oxford Nanopore long-read sequencers. | Used in the protocol by Glinos et al. (2022) [36] |

| SIRV Spike-in RNA | Provides a known set of isoform sequences at defined ratios; used as a quantitative control to benchmark the accuracy of isoform discovery and quantification tools [37]. | Lexogen Spike-in RNA variants (SIRVs) [37] |

Integrated Data Analysis Workflow

A robust bioinformatic analysis is essential for interpreting RNA-Seq data, regardless of the initial library preparation method. The following workflow outlines a standard pipeline for processing raw sequencing data into biologically interpretable results, integrating tools and steps from the cited research [38].

Key Software Tools:

- Terminal-based Processing: FastQC for quality control; Trimmomatic for adapter trimming; HISAT2 or STAR for alignment; featureCounts for gene-level quantification [38].

- R/Bioconductor for Analysis: DESeq2 for differential expression analysis; pheatmap and ggplot2 for generating publication-quality visualizations like heatmaps and volcano plots [38].

- Specialized Isoform Tools: Bambu [36] and IsoLamp [37] for long-read data to discover and quantify known and novel isoforms.

The choice between mRNA-Seq and total RNA-Seq in bulk sequencing research is not a matter of one being universally superior to the other, but rather a strategic decision based on the primary biological question. As detailed in this guide, mRNA-Seq remains the most efficient and cost-effective tool for focused gene expression quantification, especially in large-scale studies. In contrast, Total RNA-Seq is indispensable for exploratory research aimed at discovering novel transcripts, non-coding RNAs, and comprehensively characterizing transcriptome complexity. The advent of accurate long-read sequencing has further amplified the power of total RNA-Seq, revealing a previously hidden layer of transcriptomic diversity, as evidenced by the discovery of hundreds of novel isoforms in the human brain [36] [37]. By aligning experimental goals with the strengths of each method—and leveraging the appropriate bioinformatic tools—researchers can design robust transcriptomic studies that effectively advance our understanding of biology and disease.

The reliability of bulk RNA sequencing data is fundamentally influenced by two critical pre-analytical factors: the biological sample type and the quantity of input RNA available. The choice between messenger RNA (mRNA) and total RNA sequencing strategies must be guided by the specific characteristics of the sample material, which can range from pristine frozen tissues to highly degraded archival specimens. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues and whole blood present unique challenges that necessitate specialized protocols and rigorous quality control. Furthermore, translational research often deals with limited material, requiring robust low-input methods. This guide provides a comprehensive technical framework for selecting and optimizing RNA sequencing approaches based on sample type and input requirements, enabling researchers to generate high-quality transcriptomic data within the context of bulk sequencing research.

Sample Type-Specific Considerations and Protocols

The success of an RNA-seq experiment is largely determined at the sample collection and preparation stages. The following sections detail the specific considerations, challenges, and optimized protocols for the most common sample types encountered in research and clinical settings.

FFPE Samples

Challenges and Characteristics: FFPE tissues are invaluable for retrospective clinical studies due to their wide availability and long-term storage potential. However, the formalin fixation process induces RNA fragmentation, cross-linking, and chemical modifications, resulting in degraded RNA that is suboptimal for sequencing [33] [39]. Despite these challenges, optimized protocols can successfully generate high-quality data from FFPE material.

Optimized Experimental Protocols:

- Pathologist-assisted Macrodissection: For heterogeneous tissues, precise macrodissection is critical. Implement a workflow that prioritizes high tumor content regions for DNA extraction and infiltrated tumor microenvironment regions for transcriptomic analysis [33]. This may require two distinct FFPE blocks from the same surgical specimen.

- RNA Quality Assessment: Use the DV200 value (percentage of RNA fragments >200 nucleotides) for quality control. While samples with DV200 <30% are generally considered too degraded, samples with DV200 values ranging from 37% to 70% can yield usable data with appropriate protocols [33].

- Library Preparation Protocol Selection: For FFPE-derived RNA, ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion protocols are strongly preferred over poly(A) selection, as the fragmented RNA may not contain intact poly(A) tails [39]. Two robust kit options are:

- Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep Ligation with Ribo-Zero Plus: Demonstrates excellent alignment performance (higher percentage of uniquely mapped reads), effective rRNA depletion (0.1% rRNA content), and lower duplication rates (10.73%) [33].

- TaKaRa SMARTer Stranded Total RNA-Seq Kit v2: Achieves comparable gene expression quantification with 20-fold less RNA input, a crucial advantage for limited samples, though with higher rRNA content (17.45%) and increased duplication rates (28.48%) [33].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of FFPE-Compatible Library Prep Kits

| Performance Metric | Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep | TaKaRa SMARTer Stranded Total RNA-Seq v2 |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum Input RNA | Standard (~100ng) | 20-fold lower than Illumina |

| rRNA Depletion Efficiency | 99.9% (0.1% rRNA content) | 82.55% (17.45% rRNA content) |

| Duplicate Rate | 10.73% | 28.48% |

| Uniquely Mapped Reads | Higher percentage | Lower percentage |

| Intronic Mapping | 61.65% | 35.18% |

| Gene Detection | Comparable | Comparable |

| Cost & Time | Standard | Increased sequencing depth required |

Quality Control Recommendations: Implement a decision-tree model based on pre-sequencing metrics. Recommended minimum thresholds include RNA concentration ≥25 ng/μL and pre-capture library output ≥1.7 ng/μL to achieve adequate sequencing data. Post-sequencing, samples should demonstrate median sample-wise correlation ≥0.75, ≥25 million reads mapped to gene regions, and detection of ≥11,400 genes with TPM >4 [39].

Blood Samples

Challenges and Characteristics: Whole blood is an easily accessible but challenging sample type due to high ribonuclease (RNase) activity that can rapidly degrade RNA, and the presence of abundant globin mRNAs and ribosomal RNAs that can consume a significant portion of sequencing reads if not properly managed [40].

Optimized Experimental Protocols:

- RNA Stabilization at Collection: Immediately upon collection, use specialized blood collection tubes containing RNA-stabilizing reagents such as PAXgene or Tempus tubes. These tubes inactivate RNases, yielding gene expression data that accurately reflects the blood's state at sampling. Consistency in tube type per experimental setting is critical, as different systems can yield substantial differences in gene expression profiles [40].