Navigating RNA-seq Library Preparation Biases: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Transcriptomic Analysis

RNA sequencing is a cornerstone of modern transcriptomics, yet its accuracy is fundamentally challenged by biases introduced during library preparation.

Navigating RNA-seq Library Preparation Biases: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Transcriptomic Analysis

Abstract

RNA sequencing is a cornerstone of modern transcriptomics, yet its accuracy is fundamentally challenged by biases introduced during library preparation. This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the foundational sources of bias from ligation to amplification, comparing methodological solutions for diverse applications including low-input and strand-specific sequencing, and offering troubleshooting strategies for optimization. By synthesizing evidence from recent comparative studies and technical evaluations, we outline a framework for validating library preparation methods to ensure data reliability, ultimately empowering robust experimental design and accurate biological interpretation in biomedical research.

Understanding the Roots: How Common Library Prep Steps Introduce Systematic Bias

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized biological research and clinical diagnostics. However, the intricate workflow of NGS, particularly for RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), introduces biases at nearly every step that can compromise data quality and lead to erroneous interpretation [1] [2]. A detailed understanding of these biases is essential for accurate data analysis and the development of improved protocols and bioinformatics tools. This technical support center provides a comprehensive guide to identifying, troubleshooting, and mitigating these pervasive biases in your NGS experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common sources of bias in RNA-seq library preparation? Biases can originate from nearly every step of the process. The most common sources include [2] [3]:

- Sample Preservation: RNA degradation during storage, especially in Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) samples, and cross-linking of nucleic acids with proteins.

- RNA Extraction: Inefficient purification or loss of specific RNA types (e.g., small RNAs) using certain methods like TRIzol.

- mRNA Enrichment: 3'-end capture bias during poly(A) selection and inefficiency in ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion.

- Fragmentation: Non-random fragmentation leading to reduced sequence complexity.

- Primer Bias: Inefficient priming or mispriming, particularly with random hexamers.

- Reverse Transcription: Inefficient or biased cDNA synthesis.

- Adapter Ligation: Substrate preferences of ligase enzymes causing sequence-dependent ligation efficiency.

- PCR Amplification: Preferential amplification of fragments with specific properties (e.g., neutral GC content), leading to uneven coverage and loss of library complexity.

2. How can I tell if my NGS library has a high degree of bias? Several indicators can signal a biased library [4]:

- Uneven coverage across the genome or transcriptome.

- High duplication rates in the sequencing data.

- Abnormal sequence content, such as significant AT or GC enrichment.

- The presence of adapter-dimers or other artifact sequences in quality control reports (e.g., a sharp peak at ~70-90 bp on a Bioanalyzer trace).

- Low library complexity, meaning a high number of PCR duplicates from a low number of original RNA molecules.

3. My sequencing run yielded very low coverage. What steps should I investigate first? Low yield can stem from multiple issues. A systematic troubleshooting approach is recommended [4]:

- Input Sample Quality: Verify RNA Integrity Number (RIN) or DNA quality. Check for contaminants (e.g., salts, phenol) that inhibit enzymes by ensuring good 260/230 and 260/280 ratios.

- Quantification: Use fluorometric methods (Qubit) instead of absorbance (NanoDrop) for accurate quantification of usable material.

- Fragmentation: Confirm that fragmentation produced the expected size distribution.

- Adapter Ligation: Ensure correct adapter-to-insert molar ratios and optimal ligation conditions.

- Purification: Review cleanup steps (e.g., bead ratios) to avoid accidental removal of the target library.

4. Are there PCR-free methods to avoid amplification bias? Yes, PCR-free protocols are available and are recommended when a large amount of high-quality input DNA is available [2]. These protocols circumvent PCR amplification by directly ligating adapters to the DNA fragments, thereby eliminating biases associated with unequal amplification. However, these methods require microgram quantities of input DNA and may still present other artifacts [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing PCR Amplification Bias

Problem: PCR amplification stochastically introduces biases, preferentially amplifying certain fragments over others. This leads to uneven coverage, loss of library complexity, and an overrepresentation of duplicates in sequencing data [2].

Solutions:

- Minimize PCR Cycles: Use the minimum number of PCR cycles necessary to generate sufficient library material [2].

- Polymerase Selection: Use high-fidelity polymerases, such as Kapa HiFi, which are designed for more uniform amplification compared to others like Phusion [2].

- PCR Additives: For extremely AT-rich or GC-rich sequences, use additives like TMAC (tetramethylammonium chloride) or betaine to help neutralize base-composition bias [2].

- PCR-Free Protocols: Whenever input material allows, adopt PCR-free library preparation methods [2].

Table 1: Troubleshooting PCR Amplification Bias

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| High duplicate read rate | Too many PCR cycles; low input complexity | Reduce PCR cycles; increase input material |

| Skewed coverage in GC-rich/AT-rich regions | Polymerase bias against extreme GC/AT content | Use PCR additives (TMAC, betaine); optimize extension temperature/time |

| Low library diversity | Preferential amplification of a subset of fragments | Switch polymerase (e.g., to Kapa HiFi); use unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) |

Guide 2: Mitigating Bias from RNA Input and Fragmentation

Problem: The quality, quantity, and fragmentation of the input RNA can significantly impact the representativeness of the final sequencing library. Degraded or low-input RNA reduces complexity, while non-random fragmentation creates length biases [2].

Solutions:

- Input RNA Quality: For degraded samples (e.g., FFPE), use high RNA input and switch to random priming for reverse transcription instead of oligo-dT [2].

- RNA Extraction Method: Select extraction methods optimized for your RNA species of interest. For example, the mirVana miRNA kit is reported to be superior for small RNA yield and quality compared to TRIzol [2].

- Fragmentation Method: Use chemical treatment (e.g., zinc-based fragmentation) rather than enzymatic methods (e.g., RNase III) for more random fragmentation [2]. Alternatively, fragment the cDNA after reverse transcription using mechanical or enzymatic methods [2].

Table 2: Troubleshooting RNA Input and Fragmentation Issues

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low mapping rates; 3'-bias in coverage | RNA degradation; use of oligo-dT on degraded RNA | Check RNA integrity (RIN); use random primers for RT |

| Loss of small RNA representation | Suboptimal RNA extraction method | Use specialized kits (e.g., mirVana) for small RNA isolation |

| Reduced sequence complexity | Non-random RNA fragmentation | Switch from enzymatic to chemical fragmentation methods |

Guide 3: Resolving Adapter Ligation and Primer Bias

Problem: The enzymes used in adapter ligation and reverse transcription can have sequence-dependent preferences, leading to the under-representation of certain sequences in your library [2].

Solutions:

- Adapter Design: Use adapters with random nucleotides at the ligation junctions. This helps to minimize the substrate preference of T4 RNA ligases [2].

- Ligation Conditions: Optimize adapter-to-insert molar ratios, temperature, and duration. For cohesive-end ligation, lower temperatures (12-16°C) and longer durations (overnight) can enhance efficiency, especially for low-input samples [5].

- Priming Strategy: To mitigate random hexamer priming bias, one proposed solution is to avoid converting RNA to double-stranded cDNA with random primers altogether. Instead, sequencing adapters can be ligated directly onto the RNA fragments themselves [2]. Bioinformatics tools can also be used to reweight read counts to adjust for this bias [2].

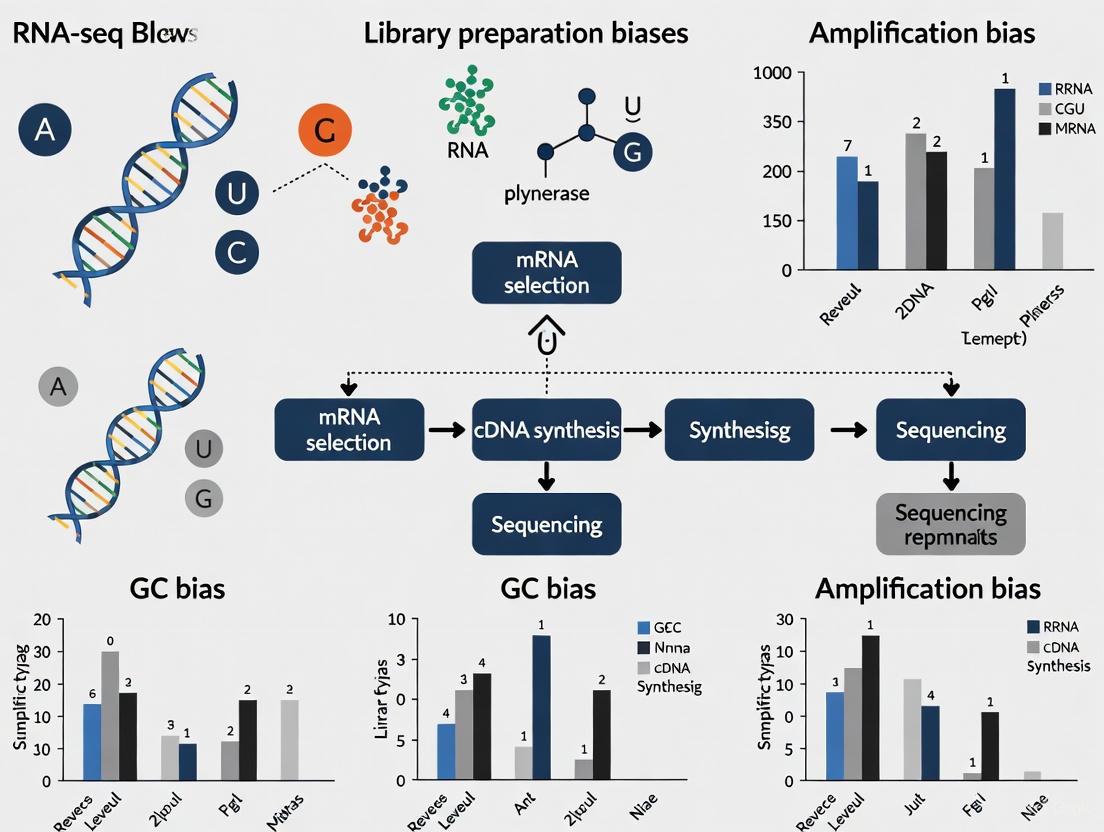

The following diagram illustrates a generalized NGS workflow for RNA-seq with key sources of bias highlighted at each stage.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and materials used in NGS library preparation, along with their functions and considerations for mitigating bias.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Their Roles in Mitigating NGS Bias

| Reagent/Material | Function in Workflow | Considerations for Bias Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits (e.g., mirVana) | Isolate and purify RNA from samples. | Select kits validated for your RNA species of interest (e.g., small RNAs) to avoid selective loss [2]. |

| Oligo-dT Beads / rRNA Depletion Kits | Enrich for polyadenylated mRNA or remove ribosomal RNA. | Be aware of 3'-end capture bias with oligo-dT. Use rRNA depletion for non-polyadenylated transcripts or degraded RNA [2]. |

| Fragmentation Reagents (Enzymatic vs. Chemical) | Break RNA into appropriately sized fragments for sequencing. | Chemical fragmentation (e.g., zinc) is often more random than enzymatic (RNase III), reducing sequence-based bias [2]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesize first-strand cDNA from RNA template. | Use high-efficiency enzymes. Consider random hexamer bias and explore alternative strategies like direct RNA ligation [2]. |

| Adapter Oligos | Provide sequences necessary for binding to the flow cell and indexing. | Use adapters with random base extensions at ligation ends to combat ligase sequence preference [2]. Ensure correct molar ratios to prevent adapter-dimer formation [5]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (e.g., Kapa HiFi) | Amplify the adapter-ligated library to generate sufficient mass for sequencing. | Selected for uniform amplification across sequences with varying GC content to minimize PCR bias [2]. |

| Solid Phase Reversible Immobilization (SPRI) Beads | Purify and size-select nucleic acid fragments between enzymatic steps. | Precisely control bead-to-sample ratios to avoid skewed size selection and loss of desired fragments [4]. |

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) library preparation, the ligation of adapter sequences to RNA fragments is a fundamental step that enables subsequent amplification and sequencing. However, this process is not neutral; T4 RNA ligases used in these procedures demonstrate strong sequence-specific biases and structure-specific preferences that systematically distort the representation of RNA species in the final sequencing library [6] [7]. This ligation bias originates from the inherent substrate preferences of the enzymes themselves, particularly T4 RNA Ligase 1 (Rnl1) and truncated T4 RNA Ligase 2 (Rnl2tr) [6] [8]. When certain RNA fragments ligate more efficiently than others due to their terminal sequences or structural features, the resulting sequencing data no longer accurately reflects the original RNA abundances, potentially leading to erroneous biological conclusions [2] [1]. Understanding and mitigating this bias is therefore crucial for any researcher relying on RNA-seq data for transcriptome analysis, small RNA discovery, or quantitative gene expression studies.

Mechanisms: How Ligation Bias Occurs

Ligation bias in RNA-seq libraries arises through two primary, interconnected mechanisms: sequence-specific preferences and structural constraints.

Sequence-Specific Bias of RNA Ligases

The RNA ligases used in library preparation do not treat all sequence ends equally. Comprehensive studies using randomized RNA pools have demonstrated that these enzymes have intrinsic preferences for certain nucleotides at positions near the ligation junction [6] [8]. One study found that the thermostable ligase Mth K97A exhibited a strong preference for adenine and cytosine at the third nucleotide from the ligation site [8]. This means that RNA fragments with preferred nucleotides at their ends will be overrepresented in the final library, while those with disfavored sequences will be underrepresented, creating a distorted view of the actual RNA population.

Structural Bias: RNA and Adaptor Co-folding

Beyond primary sequence, the secondary structure of RNA fragments and their ability to co-fold with adapter sequences significantly impacts ligation efficiency [7]. Research has shown that over-represented sequences in sequencing libraries are more likely to be predicted to have secondary structure and to co-fold with adaptor sequences [8] [7]. These structures can either facilitate or hinder the ligation reaction by making the RNA ends more or less accessible to the ligase enzyme. One investigation noted that "over-represented fragments were more likely to co-fold with the adaptor," suggesting that certain RNA-adaptor combinations form favorable structural contexts that promote efficient ligation [8].

The following diagram illustrates the key experimental findings on the sources and impacts of ligation bias:

Experimental Evidence and Quantitative Data

Multiple studies have systematically quantified the extent and impact of ligation bias in RNA-seq library preparation. The following table summarizes key experimental findings from the literature:

Table 1: Quantitative Evidence of Ligation Bias from Experimental Studies

| Study System | Experimental Approach | Key Finding on Bias Magnitude | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized RNA pool [8] | Comparison of library preparation protocols | Most abundant sequences were present ≥5 times more than expected without bias; CircLig protocol reduced over-representation by approximately half compared to standard protocol | Even the best available protocols significantly distort RNA representation |

| Defined miRNA mixtures [7] | Comparison of miRNA detection with different adaptors | Using randomized adaptors in both ligation steps produced HTS results that better reflected the starting miRNA pool | Adaptor sequence directly impacts quantification accuracy |

| Mouse insulinoma cells [9] | Comparison of Illumina v1.5 vs. TruSeq protocols | 102 highly expressed miRNAs were >5-fold differentially detected between protocols; some miRNAs (e.g., miR-24-3p) showed >30-fold differential detection | Choice of commercial library prep kit drastically affects results |

| Small RNA sequencing [6] | Testing of modified adaptor strategies | Identified reproducible discrepancies specifically arising from ligation or amplification steps, with T4 RNA ligases as the predominant cause of distortions | Points to a specific enzymatic step as the primary source of bias |

The evidence consistently demonstrates that ligation bias is not a minor technical artifact but a substantial factor that can dramatically alter the perceived abundance of RNA species, potentially leading to incorrect biological interpretations.

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Ligation Problems

Researchers encountering potential ligation bias in their RNA-seq experiments can use the following troubleshooting guide to identify and resolve common issues:

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Ligation-Related Issues in RNA-Seq

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uneven RNA representation | Sequence-specific ligase preference; RNA secondary structure | Use pooled adaptors with random nucleotides at ligation boundaries; employ structured adaptors that promote uniform ligation | Demonstrated to recover miRNAs that evade capture by standard methods [9] and reduce bias [6] [7] |

| Low library diversity | Inefficient ligation of certain RNA species; high adapter dimer formation | Use chemically modified adapters that inhibit dimer formation; optimize adapter concentration and purification steps | Kits addressing adapter dimers produce higher-quality results with lower input RNA [9] |

| Inconsistent results between protocols | Different adapter sequences and ligation conditions | Standardize library preparation method across experiments; when comparing datasets, account for protocol differences bioinformatically | Different Illumina protocols produced strikingly different miRNA profiles from the same RNA sample [9] |

| Poor ligation efficiency | Enzyme inhibitors; suboptimal reaction conditions | Ensure RNA is free of contaminants (salts, EDTA, phenol); use fresh ATP-containing buffer; optimize enzyme concentration and incubation time | Reaction efficiency decreases with degraded ATP and inhibitors [10] [11] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do different commercial library preparation kits produce different results from the same RNA sample? Different kits use distinct adapter sequences and ligation conditions, which interact variably with the diverse sequences and structures in your RNA population. Studies have shown that these differences can cause >30-fold variation in the detection of some miRNAs [9]. This occurs because each adapter sequence has different ligation efficiencies with different RNA ends, and each ligase enzyme has its own sequence and structure preferences [6] [7].

Q2: Can I bioinformatically correct for ligation bias after sequencing? While some bioinformatic methods exist to partially compensate for ligation bias, such as read count reweighing schemes [2], they cannot fully eliminate bias introduced during the physical library preparation process. The most effective approach combines wet-lab biochemical optimizations (like using pooled adapters) with bioinformatic corrections, as post-sequencing corrections cannot recover RNAs that completely failed to ligate during library preparation [8] [9].

Q3: How does RNA quality affect ligation bias? RNA quality significantly impacts ligation efficiency and bias. Degraded RNA with fragmented ends presents diverse terminal sequences that may ligate with varying efficiencies, increasing bias [2] [12]. High-quality RNA with minimal degradation provides more consistent ligation substrates. Always quality-check RNA using methods like Bioanalyzer/TapeStation (RIN >8 recommended) and use nuclease-free techniques to prevent degradation [12] [9].

Q4: Are there specific RNA types more susceptible to ligation bias? Yes, small RNAs with significant secondary structure near their termini are particularly prone to ligation bias because structure affects adapter accessibility [7]. Some miRNAs with specific terminal sequences may be consistently under-represented with certain adapter sets [9]. RNAs with extreme GC content may also exhibit biased representation due to structural constraints and melting temperature considerations during ligation [2] [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues key reagents and methodologies discussed in the literature for mitigating ligation bias:

Table 3: Research Reagents and Methods for Reducing Ligation Bias

| Reagent/Method | Purpose/Function | Evidence of Efficacy |

|---|---|---|

| Pooled Adapters (e.g., NEXTflex V2) | Adapters with random nucleotides at ligation boundaries provide diverse ligation contexts | Detects miRNAs missed by standard methods; correlates better with RT-qPCR data [9] |

| trRnl2 K227Q mutant | Reduced bias variant of T4 RNA Ligase 2 | Associated with almost half the level of over-representation compared to standard protocol [8] |

| CircLigase-based protocol | Single adaptor approach that avoids T4 Rnl1 | Results in less over-representation of specific sequences than standard protocol [8] |

| Structured Adapters | Adapters with complementary regions that promote uniform circularization | Encourages consistent structural context for all miRNAs, reducing bias [7] [9] |

| Chemical modification of adapters | Prevents adapter dimer formation | Increases proportion of informative sequencing reads, especially critical for low-input samples [9] |

Experimental Protocol: Pooled Adapter Strategy for Bias Reduction

This protocol is adapted from studies that successfully reduced ligation bias using adapter pooling strategies [6] [9]. The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps:

Adapter Design and Synthesis

- Design 5' and 3' adapters with 2-4 random nucleotides (NN or NNNN) at the ligation boundaries [6] [9].

- For additional bias reduction, consider designing adapters with short complementary regions that encourage formation of uniform structures during ligation [7].

- Synthesize the adapter pools using mixed base chemistry to ensure diversity.

- For 3' DNA adapters, include 5' rAPP and 3'ddC modifications to prevent self-ligation and circularization [6].

Library Preparation Steps

- Starting Material: Use high-quality, high-integrity RNA (RIN >8) to minimize additional sources of bias [12] [9].

- 3' Adapter Ligation:

- Ligate the pooled 3' adapter to RNA using truncated T4 RNA Ligase 2 (Rnl2tr) or the bias-reduced mutant K227Q in an appropriate buffer.

- Use ATP-free conditions for this step when using pre-adenylated adapters [6].

- Purification: Purify the ligation products by denaturing PAGE to precisely isolate RNA-adapter conjugates and remove excess adapter [6] [9].

- 5' Adapter Ligation:

- Ligate the pooled 5' adapter using T4 RNA Ligase 1 (Rnl1) with ATP-containing buffer [6].

- Reverse Transcription and Amplification:

- Final Purification: Gel-purify the completed library to remove PCR artifacts and adapter dimers.

Data Analysis Considerations

- Pre-processing: Trim the random bases from the beginning and end of sequencing reads before alignment [9].

- Quality Assessment: Compare the distribution of detected RNAs to expected abundances when working with defined samples.

- Validation: Consider validating key findings with an orthogonal method such as RT-qPCR, especially for RNAs of particular biological interest [9].

This protocol leverages the principle that providing diverse adapter sequences increases the probability that each RNA species will encounter an adapter with which it can ligate efficiently, thereby producing a more representative library that better reflects the true composition of the original RNA sample [6] [7] [9].

Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) constitutes a formidable challenge in transcriptome studies, representing over 80-90% of total RNA in most cells [13] [14] [15]. This overwhelming abundance necessitates efficient removal or enrichment strategies to enable meaningful sequencing of informative RNA species. The two predominant methods for addressing this challenge—polyA+ selection and rRNA depletion (ribodepletion)—employ fundamentally different principles, each introducing specific biases and technical considerations that impact downstream data interpretation [2] [14].

Within the broader context of research on RNA-seq library preparation biases, understanding the methodological choice between these approaches becomes paramount. This technical support center document synthesizes current evidence to guide researchers in selecting appropriate protocols, troubleshooting common issues, and implementing best practices tailored to their experimental goals, sample types, and biological questions.

Core Technology Comparison: Mechanisms and Technical Specifications

Fundamental Mechanisms of Action

PolyA+ Selection utilizes oligo-dT primers or beads to hybridize to the polyadenylated 3' tails of mature messenger RNAs (mRNAs) [16] [17]. This mechanism selectively enriches for polyadenylated transcripts while excluding rRNAs, transfer RNAs (tRNAs), and other non-polyadenylated species. This method provides a targeted approach but is inherently limited to transcripts containing intact polyA tails.

rRNA Depletion (Ribodepletion) employs sequence-specific DNA or RNA probes complementary to ribosomal RNA sequences [18] [16]. These probes hybridize to rRNA molecules, which are subsequently removed from the total RNA pool through magnetic bead capture or enzymatic digestion. This strategy preserves both polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated transcripts, offering a broader view of the transcriptome.

The workflow for each method can be visualized as follows:

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The choice between polyA+ selection and rRNA depletion significantly impacts key sequencing metrics and data quality. Performance varies substantially across sample types, RNA integrity levels, and target organisms.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of rRNA Depletion vs. PolyA+ Selection Across Sample Types

| Performance Metric | Blood Samples | Colon Tissue | FFPE Samples | Bacterial Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usable Exonic Reads | 22% (rRNA depletion) vs. 71% (polyA+) [14] | 46% (rRNA depletion) vs. 70% (polyA+) [14] | ~20% (rRNA depletion) [15] | Highly variable by depletion method [18] |

| Intronic/Intergenic Reads | ~62% (rRNA depletion) vs. ~32% (polyA+) [15] | Similar pattern as blood but less pronounced [14] | >60% (rRNA depletion) [15] | Not applicable |

| Additional Reads Needed for Equivalent Exonic Coverage | 220% more with rRNA depletion [14] | 50% more with rRNA depletion [14] | Protocol dependent [15] | Method dependent [18] |

| rRNA Removal Efficiency | Up to 97-99% with optimized probes [16] | Up to 97-99% with optimized probes [16] | Comparable to polyA+ in fresh-frozen [15] | Varies by kit: 65-95% [18] |

Table 2: Transcript Detection Capabilities by RNA Biotype

| RNA Biotype | PolyA+ Selection | rRNA Depletion | Key Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-coding mRNA | High detection efficiency [14] | High detection efficiency [14] | Both methods suitable for coding transcripts |

| Long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) | Limited to polyadenylated forms [14] | Comprehensive detection [13] [14] | rRNA depletion essential for complete lncRNA profiling |

| Histone mRNAs | Not detected (lack polyA tails) [17] | Detected [17] | Critical consideration for epigenetics studies |

| Pre-mRNA & Nascent Transcripts | Minimal detection [14] | Significant detection [14] [15] | rRNA depletion enables analysis of transcriptional regulation |

| Small RNAs | Not efficiently captured [14] | Detected but may require specific protocols [14] | Specialized small RNA protocols recommended |

| Non-polyadenylated Viral RNAs | Not detected [17] | Detected [17] | Important for virology and pathogen discovery |

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

Library Preparation and Quality Control Issues

Observation: High adapter-dimer peaks (~127 bp) on Bioanalyzer

- Possible Causes: Addition of undiluted adapter; RNA input too low; RNA over-fragmented or lost during fragmentation; inefficient ligation [19].

- Effects: Adapter-dimer will cluster and be sequenced, wasting sequencing capacity.

- Solutions: Dilute adaptor (10-fold dilution) before setting up ligation reaction; clean up PCR reaction again with 0.9X SPRIselect Beads (note: second clean up may reduce library yield) [19].

Observation: Additional Bioanalyzer peak at higher molecular weight (~1,000 bp)

- Possible Causes: PCR artifact from over-amplification [19].

- Effects: If ratio is low compared to library, may not problematic for sequencing.

- Solutions: Reduce number of PCR cycles to prevent primers from becoming limiting in late cycles [19].

Observation: Broad library size distribution

- Possible Causes: Under-fragmentation of RNA [19].

- Effects: Library will contain longer insert sizes, potentially affecting sequencing efficiency.

- Solutions: Increase RNA fragmentation time [19].

Method-Specific Performance Issues

Problem: High residual rRNA in ribodepletion libraries

- Potential Cause: Probe mismatch, especially in non-model organisms or with pan-prokaryotic kits [13] [18] [17].

- Solutions: Use species-specific probes; for non-model organisms, consider custom-designed probes [13] [18]; pilot a few samples and check percent rRNA before scaling [17].

- Technical Note: One study developed a custom set of 200 probes specifically matching C. elegans rRNA sequences, which significantly improved depletion efficiency compared to mammalian-optimized probes [13].

Problem: Strong 3' bias in polyA+ selected libraries

- Potential Cause: RNA degradation, particularly common in FFPE or clinically derived samples [15] [17].

- Solutions: For degraded samples, switch to rRNA depletion rather than increasing sequencing depth; use RNA integrity metrics (RIN/DV200) to guide method selection [17].

- Technical Note: rRNA depletion demonstrates more uniform coverage along transcript bodies and preserves 5' coverage better in compromised RNA [15] [17].

Problem: Low detection of non-coding RNAs

- Potential Cause: Using polyA+ selection, which excludes non-polyadenylated transcripts [13] [14].

- Solutions: Implement rRNA depletion to capture non-polyadenylated species including many lncRNAs, pre-processed RNAs, and regulatory RNAs [13] [16].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I choose polyA+ selection versus rRNA depletion for my RNA-seq experiment?

A: The decision should be guided by three key factors: (1) organism, (2) RNA integrity, and (3) research focus [17]:

- Choose polyA+ selection for: Intact eukaryotic RNA (RIN ≥7 or DV200 ≥50%); primary focus on coding mRNA; gene-level differential expression studies [14] [17].

- Choose rRNA depletion for: Degraded or FFPE samples; need to detect non-polyadenylated RNAs (lncRNAs, histone mRNAs, viral RNAs); prokaryotic transcriptomics; studies requiring information on nascent transcription [15] [16] [17].

Q2: How does RNA quality impact method selection?

A: RNA quality significantly affects performance:

- High-quality RNA: Both methods work well, with polyA+ selection providing higher exonic mapping rates for coding genes [14].

- Degraded/FFPE RNA: rRNA depletion outperforms polyA+ selection due to better tolerance of fragmentation and crosslinks [15] [17]. PolyA+ selection on degraded RNA produces strong 3' bias and under-represents long transcripts [17].

Q3: What are the key differences in data output between these methods?

A: The methods produce fundamentally different data profiles:

- PolyA+ selection: Higher percentage of reads mapping to exonic regions; more efficient for gene-level quantification of protein-coding genes; lower sequencing depth required for equivalent exon coverage [14].

- rRNA depletion: Captures wider diversity of transcript types; higher percentage of intronic reads (indicative of pre-mRNA); requires more sequencing depth to achieve equivalent exon coverage; enables detection of non-polyadenylated RNAs [13] [14] [15].

Q4: Are there organism-specific considerations for rRNA depletion?

A: Yes, organism-specific optimization is critical:

- Prokaryotes: PolyA+ selection is not appropriate; rRNA depletion or targeted capture is standard [18] [17].

- Non-model eukaryotes: Commercial pan-eukaryotic kits may have suboptimal efficiency; custom probes designed against specific rRNA sequences significantly improve performance [13].

- Clinical samples: Blood samples may require additional globin RNA depletion alongside rRNA removal for optimal detection of low-expression transcripts [20].

Q5: How can I improve my ribodepletion efficiency?

A: Several strategies can enhance depletion:

- Use species-specific probes rather than pan-species kits [13] [18].

- Validate probe matching through pilot studies before scaling [17].

- For bacteria, consider methods that target 5S rRNA in addition to 16S and 23S rRNA [18].

- Ensure high-quality total RNA input through proper extraction and handling [16].

Essential Protocols and Methodologies

Experimental Workflow for Method Comparison

For researchers conducting comparative evaluations of polyA+ selection versus ribodepletion, the following experimental design provides a robust framework:

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for rRNA Depletion and PolyA+ Selection Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Ribo-Zero Gold, RiboMinus, riboPOOLs, SoLo Ovation [13] [18] [15] | Remove ribosomal RNA via hybridization and magnetic bead capture; efficiency varies by species specificity [18]. |

| PolyA+ Selection Kits | SMARTSeq V4, TruSeq RNA Library Prep Kit [13] [21] | Enrich polyadenylated transcripts using oligo-dT primers or beads; optimized for eukaryotic mRNA [14]. |

| Custom Probe Design Services | Tecan Genomics Custom AnyDeplete, self-designed biotinylated probes [13] [18] | Species-specific rRNA depletion for non-model organisms; significantly improves efficiency [13]. |

| Library Preparation Systems | NEBNext Ultra Directional RNA Kit, TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Kit [19] [21] | Post-enrichment/depletion library construction; impact strand-specificity and bias patterns [2]. |

| RNA Quality Assessment Tools | Agilent Bioanalyzer, Qubit Fluorometer, RNA Integrity Number (RIN) [13] [21] | Critical for method selection; determines suitability for polyA+ selection [17]. |

| Bias Reduction Additives | Kapa HiFi Polymerase, PCR additives (TMAC, betaine) [2] | Reduce GC bias and improve amplification uniformity; particularly important for extreme GC content genomes [2]. |

The choice between polyA+ selection and rRNA depletion represents a fundamental experimental design decision that shapes all subsequent data interpretation. Within the broader research context of RNA-seq library preparation biases, evidence consistently demonstrates that each method offers distinct advantages and limitations that must be aligned with research objectives.

For coding transcript quantification in eukaryotes with high-quality RNA, polyA+ selection provides superior efficiency and exonic coverage. For comprehensive transcriptome characterization, including non-polyadenylated species, or when working with degraded clinical samples or prokaryotes, rRNA depletion offers the necessary breadth and tolerance. Critically, custom species-specific probe design significantly enhances ribodepletion performance, particularly for non-model organisms [13] [18].

As transcriptomics continues to evolve toward more nuanced applications—including single-cell sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, and multi-omics integration—understanding these foundational methodological choices remains essential for generating biologically meaningful, technically robust data that advances both basic research and drug development.

PCR amplification is a fundamental step in preparing DNA and RNA sequencing libraries. However, this process introduces various artifacts that can significantly skew quantitative measurements in your data. Understanding these artifacts—including PCR duplicates, amplification bias, and mispriming events—is crucial for accurate interpretation of sequencing results, particularly in quantitative applications like gene expression analysis [22] [23] [24].

This guide addresses the most common PCR-related artifacts, their impact on data integrity, and provides practical solutions for identification and troubleshooting within the context of RNA-seq library preparation bias research.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are PCR duplicates and how do they affect my RNA-seq data?

PCR duplicates are multiple identical reads originating from a single original DNA or RNA fragment due to PCR amplification [23]. In RNA-seq experiments, they can artificially inflate counts for specific transcripts, leading to inaccurate gene expression measurements [25] [26]. However, it's important to distinguish true PCR duplicates from "natural duplicates" (multiple independent fragments from highly expressed genes), as removing the latter can introduce bias [26].

How can I identify if PCR artifacts are affecting my data?

Several indicators suggest PCR artifact contamination:

- Inability to verify RNA-seq results with qPCR (failure to confirm 18 out of 20 differentially expressed genes) [25]

- High percentages of identical reads (approximately 25% reads removed during deduplication) [25]

- Recurrent ambiguous base calls at specific genomic positions [22]

- Spurious peaks with flush 3' ends in short RNA-seq data [24]

What causes uneven amplification across different sequences?

Multi-template PCR often results in non-homogeneous amplification due to sequence-specific factors [27]. Even with a slight (5%) amplification efficiency disadvantage relative to other templates, a sequence can be underrepresented by approximately two-fold after just 12 PCR cycles [27]. This bias occurs due to:

- Sequence-specific amplification efficiencies independent of GC content

- Adapter-mediated self-priming mechanisms

- Primer binding site mutations in evolving templates like viruses [22]

Should I always remove duplicate reads from RNA-seq data?

Not necessarily. For RNA-seq data, 70-95% of read duplicates may be "natural duplicates" from highly expressed genes rather than technical PCR duplicates [26]. Removing these natural duplicates can bias expression quantification. Computational methods that leverage heterozygous variants can help distinguish between natural and PCR duplicates for accurate estimation of true PCR duplication rates [26].

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Suspected PCR Artifacts in RNA-seq Data

Symptoms:

- Discrepancy between RNA-seq and qPCR validation results [25]

- Unexplained differential expression with high duplicate reads [25]

- Spurious peaks or inconsistent coverage across samples [24]

Solutions:

- Computational Assessment: Use tools like

PCRduplicatesto estimate true PCR duplication rates by leveraging heterozygous variants in your data [26]. - Sequence Analysis: Check for flush 3' ends in read alignments and complementarity to RT-primer sequences, which may indicate reverse transcription mispriming [24].

- Deduplication Strategy: Apply appropriate deduplication based on your experiment type. For DNA-seq, most duplicates are technical, while for RNA-seq, most may be biological [26].

Problem: Primer-Related Artifacts in Targeted Sequencing

Symptoms:

- Recurrent ambiguous base calls or consistent base calling errors [22]

- Amplicon drop-outs in specific regions [22]

- Rapid accumulation of ambiguous bases during new variant emergence [22]

Solutions:

- Primer Scheme Updates: Continuously monitor and update primer schemes to address viral evolution [22].

- Spike-in Primers: Implement custom "spike-in" primers for emerging variants with primer binding site mutations [22].

- Reference Genome Optimization: Use reference genomes with closer genetic distance to your samples to improve read mapping [22].

Problem: Non-Homogeneous Amplification in Multi-template PCR

Symptoms:

- Progressive skewing of coverage distributions with increased PCR cycles [27]

- Severe depletion of specific amplicon sequences [27]

- Inaccurate abundance measurements in quantitative applications [27]

Solutions:

- Cycle Optimization: Minimize PCR cycles to reduce amplification skew while maintaining sufficient library complexity [23].

- Deep Learning Prediction: Utilize computational models (1D-CNNs) to predict sequence-specific amplification efficiencies during experimental design [27].

- Alternative Enzymes: Consider thermostable group II intron-derived reverse transcriptases (TGIRT) to avoid mispriming artifacts [24].

Quantitative Impact of PCR Artifacts

Table 1: Common PCR Artifacts and Their Quantitative Impacts

| Artifact Type | Primary Cause | Effect on Quantitative Data | Typical Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR Duplicates | Over-amplification of original fragments | Artificial inflation of read counts for specific sequences | 5-30% in RNA-seq [26] |

| Amplification Bias | Sequence-specific efficiency differences | Skewed abundance measurements; under-representation of low-efficiency templates | 2% of sequences with very poor efficiency (<80% of mean) [27] |

| Primer-Index Hopping | Mismatches in primer binding sites | Ambiguous base calls; amplicon drop-outs; omitted defining mutations | Rapid accumulation during variant emergence [22] |

| RT Mispriming | Non-specific annealing of RT primers | False cDNA ends; spurious peaks in coding exons | 10,000+ sites per dataset in affected studies [24] |

Table 2: Comparison of Computational Detection Methods for PCR Artifacts

| Method | Target Artifact | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heterozygous Variant Analysis [26] | PCR duplicates | Distinguishes technical vs. natural duplicates; Works on existing data | Requires heterozygous sites in genome |

| Mispriming Identification Pipeline [24] | RT mispriming | Identifies artifacts with minimal complementarity (2 bases); Filters spurious peaks | Requires specific sequence patterns |

| Deduplication Tools | PCR duplicates | Standard in most pipelines; Reduces redundant reads | Risk of removing biological duplicates in RNA-seq |

| Deep Learning Models [27] | Amplification bias | Predicts efficiency from sequence alone; Designs homogeneous libraries | Requires training data; Complex implementation |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Estimating True PCR Duplication Rate from Sequence Data

This protocol estimates the PCR duplication rate while accounting for natural duplicates using heterozygous variants [26].

- Identify Duplicate Clusters: Group reads with identical outer mapping coordinates.

- Select Heterozygous Sites: Use known or called heterozygous SNVs in your sample.

- Analyze Allele Patterns: For duplicate clusters of size 2 overlapping heterozygous sites:

- Clusters with opposite alleles indicate natural duplicates

- Clusters with identical alleles indicate PCR duplicates

- Calculate Proportions: Estimate unique DNA fragments using the formula:

- U₂ = [1·(C₂ - 2C₂₁) + 2·2C₂₁] / C₂

- Where C₂ = total clusters of size 2, C₂₁ = clusters with opposite alleles

- Extend to Larger Clusters: Apply mathematical modeling to estimate proportions for larger cluster sizes.

Protocol 2: Identifying and Removing RT Mispriming Artifacts

This computational pipeline identifies cDNA reads produced from reverse transcription mispriming [24].

- Read Alignment: Use a global aligner (BWA) for sequencing reads.

- Filter Non-coding RNAs: Remove reads mapping to known non-protein-coding genes.

- Identify Flush-ended Peaks: Find genomic positions with >10 reads having identical 3' ends.

- Check Adapter Complementarity: Identify peaks adjacent to:

- Dinucleotides matching the 3' adapter (k-mer sites)

- Dinucleotides not matching the 3' adapter (non-k-mer sites)

- Apply Mispriming Criteria: Classify as mispriming sites if:

- At least two bases match the 3' end of the 3' adapter

- No non-k-mer site with similar flush ends within 20 bases

- Filter Artifactual Reads: Remove reads identified as mispriming artifacts.

Experimental Workflow: From RNA Extraction to Artifact Detection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Methods for Managing PCR Artifacts

| Reagent/Method | Primary Function | Advantages | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) [26] | Tags individual molecules before amplification | Enables precise distinction of PCR duplicates from natural duplicates | Requires specialized library prep modifications |

| Low-Bias Library Prep Kits [28] | Reduces sequence-dependent amplification bias | Novel splint adaptor design; Broader input range; Simplified protocol | Commercial solution with associated costs |

| RiboGone Depletion Kits [29] | Removes ribosomal RNA from samples | Essential for random-primed protocols; Reduces wasteful rRNA sequencing | Specific to mammalian RNA in this variant |

| Thermostable Group II Intron RT (TGIRT) [24] | Reverse transcription with reduced mispriming | Template-switching activity avoids mispriming; Higher fidelity | Alternative enzyme system requiring protocol adjustment |

| SMARTer Stranded RNA-Seq Kit [29] | Maintains strand information with random priming | Works with degraded RNA (FFPE samples); >99% strand accuracy | Requires rRNA depletion or polyA selection |

| NEBNext Low-bias Small RNA Library Prep Kit [28] | Minimizes bias in small RNA representation | Fast protocol (3.5 hours); Broad input range; Handles 2'-O-methylated RNA | Specifically optimized for small RNA species |

| Artic Network Primers with Spike-ins [22] | Targeted enrichment for viral sequencing | Customizable for emerging variants; Continuously updated designs | Specific to viral genome applications |

Relationship Between PCR Cycles, Efficiency, and Coverage Skew

Effective management of PCR amplification artifacts requires both experimental and computational approaches. By implementing the detection methods and mitigation strategies outlined in this guide, researchers can significantly improve the quantitative accuracy of their sequencing data and draw more reliable biological conclusions.

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Addressing Common Experimental Issues

Q1: My RNA-seq data shows uneven coverage, with poor representation of transcript ends. What could be the cause and how can I fix it?

Uneven coverage often stems from RNA fragmentation bias. Using RNase III for fragmentation is not completely random and can reduce sequence complexity [2]. To resolve this:

- Switch fragmentation methods: Use chemical treatment (e.g., zinc) instead of enzymatic digestion for a more random fragmentation pattern [2].

- Fragment after cDNA synthesis: Reverse transcribe intact RNA into cDNA first, then fragment the cDNA using mechanical or enzymatic methods [2].

- Verify with QC: Use quality control tools like RNA-SeQC to check for 3'/5' bias in your coverage metrics [30].

Q2: My library preparation seems to have a strong priming bias. How can I make my library more representative?

Priming bias, often from random hexamer mispriming, can skew transcript representation [2]. To mitigate this:

- Bypass random priming: For some protocols, you can ligate sequencing adapters directly onto RNA fragments, avoiding the cDNA synthesis step that uses random hexamers [2].

- Use a read count reweighing scheme: Apply computational correction post-sequencing to adjust for the bias and create a more uniform read distribution [2].

- Optimize primer choice and temperature: For gene-specific primers, ensure the sequence is unique to the target. Performing reverse transcription at a higher temperature with a thermostable enzyme can also increase primer binding specificity [31].

Q3: I am working with degraded RNA samples (e.g., FFPE). How can I minimize biases during library prep?

Degraded RNA requires specific adjustments to counteract biases introduced by fragmentation and priming [2]:

- Use random primers: Instead of oligo(dT) primers, which require an intact poly-A tail, use random hexamers for cDNA synthesis to ensure coverage across the entire fragment length of degraded RNA [31].

- Increase input material: Use a higher amount of starting RNA to compensate for degradation [2].

- Select a bias-resistant protocol: Choose a reverse transcriptase that works efficiently with degraded samples and consider PCR additives like betaine for AT/GC-rich regions [2] [31].

Table 1: Common Biases, Their Effects, and Quantitative Improvement Methods

| Bias Type | Effect on Coverage Uniformity | Improvement Method | Key Metric for QC |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Fragmentation Bias [2] | Reduced complexity; non-random fragment start/end sites. | Use chemical (e.g., zinc) instead of RNase III fragmentation [2]. | Coverage continuity; gap metrics (RNA-SeQC) [30]. |

| Random Hexamer Priming Bias [2] | Non-uniform read start sites; under-representation of transcript 5' ends. | Use direct RNA adapter ligation or read count reweighing [2]. | Uniformity of read start site distribution. |

| Adapter Ligation Bias [2] | Under-representation of sequences difficult to ligate. | Use adapters with random nucleotides at ligation extremities [2]. | Ligation efficiency measured by percentage of usable reads. |

| PCR Amplification Bias [2] | Preferential amplification of cDNA with neutral GC content; distortion of abundance. | Use polymerases like Kapa HiFi; reduce PCR cycles; additives (TMAC/betaine) for extreme GC% [2]. | Duplication rate; GC bias curve (RNA-SeQC) [30]. |

Experimental Protocols for Bias Mitigation

Protocol 1: Minimizing Fragmentation Bias with Chemical Treatment This protocol replaces enzymatic RNA fragmentation with divalent metal cations to generate more random fragments [2].

- Input: 1 µg of high-quality total RNA.

- Fragmentation Buffer Preparation: Prepare a 100 mM Zinc Chloride (ZnCl₂) solution in nuclease-free water.

- Reaction Setup: Combine RNA and fragmentation buffer to a final concentration of 10 mM ZnCl₂. Incubate at 70°C for 5-15 minutes (requires optimization for desired fragment size).

- Reaction Stop: Add 10 mM EDTA to chelate zinc and stop the reaction.

- Purification: Purify the fragmented RNA using RNA clean-up beads or columns. Proceed to library construction.

Protocol 2: Computational Correction for Random Hexamer Bias This bioinformatics protocol adjusts for non-uniform priming [2].

- Input Data: A BAM file containing aligned RNA-seq reads.

- Identify Primer Start Sites: Parse the alignment file to map the genomic positions corresponding to the start of each read (the presumed random hexamer binding site).

- Calculate Weighting Factors: For each transcript, model the expected uniform distribution of read starts. Calculate a weight for each read based on the observed vs. expected frequency of start sites in its region.

- Reweigh Read Counts: Apply the calculated weights to the read counts during transcript quantification.

- Output: A corrected count matrix for downstream differential expression analysis.

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 2: Strategies for Bias Mitigation

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bias Mitigation

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Role in Mitigating Bias |

|---|---|---|

| Zinc Chloride (ZnCl₂) [2] | Chemical RNA fragmentation agent. | Provides a more random fragmentation pattern compared to enzymatic methods like RNase III, reducing fragmentation bias and improving coverage uniformity. |

| Random Hexamers with Random Nucleotide Adapters [2] | Primers for cDNA synthesis and adapters for ligation. | Adapters with random nucleotides at ligation ends reduce substrate preference of ligases, mitigating adapter ligation bias. |

| Kapa HiFi Polymerase [2] | Enzyme for PCR amplification of libraries. | Reduces PCR amplification bias by offering superior performance and less GC-content preference compared to other polymerases like Phusion. |

| Betaine or TMAC [2] | PCR additives. | Helps neutralize extreme GC or AT content in templates, allowing for more uniform amplification of sequences with varying GC content. |

| RNA-SeQC [30] | Bioinformatics software for quality control. | Provides key metrics (like 3'/5' bias, coverage continuity, GC bias) to detect and quantify the presence of biases in the final dataset, informing inclusion criteria. |

| Thermostable Reverse Transcriptase [31] | Enzyme for synthesizing cDNA from RNA. | Withstands higher reaction temperatures, minimizing RNA secondary structures that cause reverse transcription bias and lead to truncated cDNA and poor coverage. |

Choosing Your Arsenal: Comparative Analysis of Library Prep Kits and Strategies

Key Comparisons at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core technical and practical differences between stranded and non-stranded RNA-seq protocols to guide your experimental design.

| Feature | Stranded RNA-seq | Non-Stranded RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Protocol Complexity | More complex; additional steps (e.g., dUTP marking, strand degradation) [32] [33] | Simpler and more straightforward [32] [33] |

| Strand Information | Preserved. Determines if a read is from the sense or antisense DNA strand [32] | Lost. Cannot determine the transcript's strand of origin [32] |

| Quantitative Accuracy | More accurate, especially for genes with overlapping genomic loci on opposite strands [34] | Less accurate for overlapping genes; can misassign reads [34] |

| Read Ambiguity | Lower (~2.94% of reads ambiguous) [34] | Higher (~6.1% of reads ambiguous) [34] |

| Ideal Applications | Novel transcript/antisense discovery, genome annotation, complex transcriptome analysis [32] [33] | Gene expression profiling in well-annotated organisms, large-scale studies [32] |

| Cost & Input | Generally higher cost and may require more input RNA [35] | More cost-effective and can work with lower input amounts [35] [33] |

Experimental Protocols in Practice

Core Methodologies for Stranded RNA-seq

The dUTP second-strand marking method is a leading and widely adopted protocol for stranded RNA-seq [34].

- RNA Fragmentation & First-Strand Synthesis: RNA is first fragmented. First-strand cDNA synthesis is performed using random primers and reverse transcriptase [32] [33].

- Second-Strand Synthesis with dUTP Labeling: The second cDNA strand is synthesized using a nucleotide mix where dTTP is replaced with dUTP. This labels the second strand, distinguishing it from the first [32] [34].

- Adapter Ligation & Strand Degradation: Sequencing adapters are ligated to the double-stranded cDNA. Before PCR amplification, the second strand (containing uracils) is enzymatically degraded using Uracil-DNA-Glycosylase (UDG). This ensures only the first strand is amplified, preserving the strand information of the original RNA transcript [32] [34].

Key Technical Considerations for Robust Experiments

- RNA Quality is Paramount: RNA Integrity Number (RIN) >7 is generally recommended for high-quality sequencing. For degraded samples (RIN <6), ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion is more suitable than poly-A enrichment, which requires intact mRNA [35] [36].

- Minimize PCR Duplicates: The combination of low RNA input and high PCR cycle numbers can lead to a high rate of PCR duplicates, reducing library diversity and increasing noise. Using Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) is highly recommended for low-input experiments to accurately identify and account for these artifacts [37].

- rRNA Depletion Strategy: While rRNA depletion (via probe-based hybridization or RNase H methods) enriches for informative transcripts, be aware of its variable efficiency and potential for off-target effects on some genes of interest [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Category | Item | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Library Prep | dUTP Nucleotides | Labels the second strand of cDNA during synthesis, enabling its subsequent degradation and strand preservation [32] [34]. |

| Uracil-DNA-Glycosylase (UDG) | Enzymatically degrades the dUTP-labeled second cDNA strand, preventing its amplification [32] [34]. | |

| Strand-Switching Enzymes | Used in some protocols (not detailed in results) for cDNA synthesis and adapter addition. | |

| Sample QC | Agilent BioAnalyzer/TapeStation | Provides an electrophoretogram and RNA Integrity Number (RIN) to assess RNA quality [35] [36]. |

| Depletion/Enrichment | Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads | Enriches for polyadenylated mRNA from high-quality, intact total RNA [35] [36]. |

| Ribosomal RNA Depletion Kits | Removes abundant rRNA using probes, allowing sequencing of non-polyadenylated transcripts and degraded RNA [35] [36]. | |

| Bias Mitigation | Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide tags added to each RNA molecule before amplification, allowing bioinformatic identification and removal of PCR duplicates [37]. |

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

Q1: My RNA samples are partially degraded (RIN ~5). Can I still use a stranded protocol, and what is the best enrichment strategy? Yes, you can. For degraded RNA samples, ribosomal RNA depletion is strongly recommended over poly-A selection. Poly-A selection requires an intact 3' tail, which is often missing in degraded RNA. rRNA depletion targets ribosomal sequences directly and is not dependent on the RNA's integrity for enrichment [35] [36].

Q2: In my non-stranded data, I see evidence of expression in genomic regions with no annotated genes on that strand. What could this be? This is a classic limitation of non-stranded data. What appears to be expression from an unannotated region could, in fact, be antisense transcription originating from the opposite strand of an annotated gene. Without strand information, it is impossible to assign these reads correctly. Switching to a stranded protocol is essential for discovering and validating such antisense transcripts and long non-coding RNAs [32] [34].

Q3: My stranded library yield is low. What are the potential causes? Low yield in stranded preps can be attributed to its more complex workflow.

- Check RNA Input and Quality: Ensure you are using the recommended input amount and that the RNA is of high quality (RIN >7) [35] [36].

- Verify Enzymatic Steps: The additional enzymatic steps, particularly the second-strand degradation, can impact overall yield. Confirm that enzyme concentrations and reaction conditions are optimal [32].

- Assess PCR Amplification: An excessive number of PCR cycles can lead to duplicates and artifacts, but too few may result in low yield. Follow kit recommendations and consider using UMIs to monitor duplicate rates if you need to adjust cycles [37].

Q4: When is it acceptable to use the simpler, non-stranded protocol? Non-stranded RNA-seq is a valid and cost-effective choice when your primary goal is to quantify gene expression levels in an organism with a well-annotated genome, and you do not anticipate significant challenges from overlapping antisense transcripts. It is suitable for large-scale differential expression studies where strand information is not a priority [32] [33].

Decision Workflow for Protocol Selection

In the broader context of research on RNA-seq library preparation biases, the move towards low-input and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has brought the issue of amplification bias into sharp focus. These advanced methods require significant amplification of minute starting amounts of genetic material, making them particularly susceptible to distortions that can compromise data integrity and lead to erroneous biological interpretations [2] [38]. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers identify, understand, and correct for these challenges, enabling more robust and reliable experimental outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary sources of amplification bias in low-input RNA-seq? Amplification bias in low-input protocols primarily arises from the stochastic variation in amplification efficiency during the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). This can lead to the skewed representation of certain transcripts, where some molecules are over-amplified while others are under-amplified [2] [4]. Additional sources include the mispriming or nonspecific binding of primers [2], and the use of reverse transcriptases with varying efficiencies in converting RNA to cDNA, especially from fragmented or low-quality RNA templates [2] [38].

2. How does single-cell RNA-seq sensitivity relate to amplification bias? Sensitivity in scRNA-seq refers to the ability to detect a high number of transcripts per cell. Amplification bias directly threatens this sensitivity by introducing technical noise. Incomplete reverse transcription and uneven amplification of low-abundance transcripts can lead to "dropout" events, where a gene is falsely observed as not being expressed in a cell [38]. Therefore, mitigating amplification bias is crucial for improving sensitivity and accurately capturing a cell's true transcriptome.

3. What are the best practices to minimize amplification bias? Key strategies to minimize bias include:

- Using Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): UMIs are random barcodes that label individual mRNA molecules before amplification. This allows bioinformatics tools to count original molecules and correct for amplification duplicates [38] [39].

- Optimizing PCR Cycles: Using the minimum number of PCR cycles necessary to generate sufficient library material is critical, as overcycling exacerbates biases [2] [4]. As shown in the table below, kits optimized for low input may require fewer cycles.

- Selecting Appropriate Enzymes: Using high-fidelity polymerases specifically designed for unbiased amplification of GC-rich regions can help reduce bias [2] [40].

- Employing Spike-In Controls: Adding known quantities of exogenous RNA transcripts can help monitor and normalize for technical variation, including amplification efficiency [38].

4. My sequencing data shows a high rate of duplicate reads. Is this related to amplification bias? Yes, a high duplication rate is a classic signature of over-amplification during library preparation [4]. When the starting material is limited, as in low-input and single-cell experiments, the same original molecules can be repeatedly sequenced after excessive PCR cycles. The use of UMIs is the most effective way to distinguish between technical duplicates (from PCR) and biological duplicates (from truly highly expressed genes) [39].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Library Complexity and Sensitivity

Observation: The final sequencing data detects fewer genes than expected, with low unique molecule counts and a high degree of duplication.

| Possible Cause | Effect on Data | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low or degraded RNA input [2] [4] | Incomplete transcript coverage, high technical noise, and dropout of low-expression genes. | - Standardize cell lysis and RNA capture protocols [38].- Use high-quality, intact RNA with RIN > 8 for bulk low-input.- Assess RNA quality with a Bioanalyzer, not just spectrophotometry [4]. |

| Inefficient reverse transcription [2] | Loss of specific transcript classes and introduction of 3'-end bias. | - Use reverse transcriptases with high processivity and thermostability.- Incorporate template-switching oligonucleotides (TSO) for full-length cDNA capture [40]. |

| Suboptimal PCR amplification [2] [4] | Skewed representation of transcripts, over-representation of high-abundance genes, and high duplicate rates. | - Reduce the number of PCR cycles to the minimum necessary [2] [41].- Use polymerases known for uniform amplification across GC-content ranges (e.g., Kapa HiFi) [2].- For single-cell studies, always incorporate UMIs [38]. |

Problem 2: Amplification Bias and Uneven Coverage

Observation: Specific genes or regions are over-represented, coverage across transcript bodies is uneven, or there is a strong GC-content bias.

| Possible Cause | Effect on Data | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| PCR over-amplification [2] [41] | Formation of PCR artifacts (e.g., high-molecular-weight peaks on Bioanalyzer), increased chimeric reads, and flattening of expression distribution. | - Systematically titrate and reduce PCR cycle numbers. A guide from NEB suggests that extra high-molecular-weight peaks can be a direct result of over-amplification [41]. |

| Primer bias [2] | Under-representation of transcripts that do not prime efficiently with random hexamers. | - Use primers with balanced nucleotide representation.- For specific applications, consider ligation-based library methods that avoid random priming [2]. |

| Non-optimal polymerase | Preferential amplification of transcripts with neutral GC-content, leading to loss of AT-rich or GC-rich sequences. | - Switch to a polymerase mix engineered for unbiased amplification [2].- For extreme genomes, use PCR additives like TMAC or betaine [2]. |

The following table summarizes performance data from a comparison of different ultra-low-input RNA-seq kits, highlighting key metrics relevant to sensitivity and bias such as transcript detection and mappability.

Table 1: Sequencing Metrics Comparing Ultra-Low-Input cDNA Synthesis Methods (using 10 pg Mouse Brain Total RNA) [40]

| Metric | SMARTer Ultra Low v3 | SMART-Seq v4 | SMART-Seq2 Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| * cDNA Yield (ng)* | 4.7 - 6.0 | 10.6 - 12.6 | 8.1 - 11.2 |

| Number of Transcripts (FPKM >1) | ~9,400 | ~12,500 | ~10,100 |

| Reads Mapped to Genome (%) | 96 - 97% | 95 - 96% | 72 - 93% |

| Reads Mapped to Exons (%) | 73% | 76% | 66 - 67% |

| Key Improvement | Baseline | Higher sensitivity & yield | Incorporation of LNA technology |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Amplification Bias Using Spike-In Controls

Purpose: To quantitatively monitor technical variation and amplification efficiency across samples in a low-input RNA-seq experiment.

Materials:

- ERCC Spike-In Mix (or similar exogenous RNA control mix)

- Low-input RNA-seq library preparation kit (e.g., SMART-Seq v4)

- Bioanalyzer or TapeStation

- High-throughput sequencer

Methodology:

- Spike-In Addition: Prior to cDNA synthesis, add a defined, small amount of the ERCC spike-in RNA mix to each cell lysate or purified RNA sample. The amount should be consistent across all samples in the experiment [38].

- Library Preparation: Proceed with the standard low-input or single-cell library prep protocol, including reverse transcription, cDNA amplification, and library construction [40].

- Sequencing and Alignment: Sequence the libraries and align the reads to a combined reference genome that includes the host genome and the spike-in sequences.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the expression level (e.g., TPM or read counts) for each spike-in RNA.

- Plot the observed expression against the known input concentration for each spike-in. A protocol with low amplification bias will show a strong linear correlation across the entire dynamic range.

- Use the spike-in measurements to normalize the biological transcript data, correcting for global differences in amplification efficiency between samples [38].

Protocol 2: UMI-Based Correction for Amplification Duplicates

Purpose: To accurately count original mRNA molecules and remove technical duplicates introduced during PCR.

Materials:

- Library prep kit with integrated UMI design (e.g., 10x Genomics, STRT-seq)

- Computational tools for UMI deduplication (e.g., UMI-tools, zUMIs)

Methodology:

- Library Construction with UMIs: Use a protocol where UMIs are incorporated during the initial reverse transcription step, typically within the primers. This ensures each original cDNA molecule is tagged with a unique random barcode [39] [42].

- Sequencing: Perform paired-end sequencing. One read is dedicated to the transcript, and the other (or part of the same read) captures the UMI and cell barcode.

- Bioinformatic Deduplication:

- Extract UMIs and cell barcodes from the sequencing reads.

- Align the transcript reads to the reference genome.

- Group reads that align to the same genomic position and share the same cell barcode and UMI. These are considered PCR duplicates originating from a single mRNA molecule.

- Collapse these duplicate reads into a single count, representing one original molecule. This process yields a digital count of gene expression that is resistant to amplification bias [38] [42].

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 2: Amplification Bias Correction Strategies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for Mitigating Bias in Low-Input RNA-seq

| Item | Function | Example Product/Technology |

|---|---|---|

| UMI-Adopted Kits | Enables accurate counting of original mRNA molecules by tagging each with a unique barcode before amplification, allowing for bioinformatic correction of PCR duplicates. | 10x Genomics Single Cell Kits, STRT-seq [38] [42] |

| High-Sensitivity RT Kits | Improves the efficiency of reverse transcription from very small amounts of RNA, often using template-switching technology to capture full-length transcripts. | SMART-Seq v4 Ultra Low Input RNA Kit [40] |

| Spike-In Control RNAs | Provides an external standard to monitor technical variance, detection limits, and amplification efficiency across experiments. | ERCC ExFold RNA Spike-In Mixes [38] |

| Bias-Reduced Polymerases | Polymerase enzymes engineered for uniform amplification efficiency across transcripts with varying GC-content, preventing skewed representation. | Kapa HiFi Polymerase [2] |

| Computational Tools | Software packages designed to perform UMI deduplication, batch effect correction, and normalization of sequencing data. | UMI-tools, NBGLM-LBC, Seurat, Harmony [38] [42] |

FAQs: Kit Selection and Performance

Q1: How do I choose the right RNA-seq kit based on my sample type and research goals?

The choice of kit critically depends on your sample's quality, quantity, and the RNA species you aim to capture. The following table summarizes the optimal applications for different kit technologies:

| Kit Technology / Brand | Ideal Sample Input | Key Applications and Strengths |

|---|---|---|

| SMARTer Ultra Low / SMART-Seq v4 [43] | 1–1,000 cells; 10 pg–10 ng total RNA (High quality, RIN ≥8) | Full-length transcript analysis for single-cells or ultra-low input; oligo(dT) priming for polyA+ mRNA [43]. |

| SMARTer Stranded [43] | 100 pg–100 ng total RNA | Maintains strand orientation (>99% accuracy); ideal for degraded RNA (e.g., FFPE) and non-polyadenylated RNA; requires rRNA depletion [43]. |

| SMARTer Universal Low Input [43] | 200 pg–10 ng total RNA (Degraded, RIN 2-3) | Random-primed for heavily degraded or non-polyadenylated RNA from sources like FFPE or LCM [43]. |

| NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA [44] | Standard input ranges | Strand-specific library preparation; comprehensive troubleshooting guides for common library prep issues [44]. |

| Swift Biosciences Rapid RNA [45] | Not specified in results | Fast, stranded RNA-Seq library construction utilizing patented Adaptase technology [45]. |

Q2: What are the specific RNA quality requirements for these kits, and how should I assess them?

RNA Integrity Number (RIN) is a critical metric. SMARTer Ultra Low kits, which use oligo(dT) priming, require high-quality input RNA with a RIN ≥8 to ensure full-length cDNA synthesis [43]. In contrast, the SMARTer Universal Low Input Kit is designed for degraded RNA with a RIN of 2-3 [43]. For quantity and quality assessment, the use of the Agilent RNA 6000 Pico Kit is recommended, especially for low-concentration samples [43].

Q3: My RNA is degraded or from FFPE tissue. Which kit should I use?

For degraded samples, random-primed kits are superior to oligo(dT)-based ones. The SMARTer Stranded RNA-Seq Kit or the SMARTer Universal Low Input RNA Kit for Sequencing are specifically designed for this purpose [43]. These kits require prior ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion to prevent up to 90% of reads from mapping to rRNA [43].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Library QC and Sequencing Issues

Common problems observed during library quality control on the Bioanalyzer and their solutions are outlined below.

| Observation | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Bioanalyzer peak at 127 bp (Adapter-dimer) [44] | - Addition of undiluted adapter- RNA input too low- Inefficient ligation | - Dilute adapter (10-fold) before ligation- Perform a second PCR cleanup with 0.9X SPRI beads [44] |

| Bioanalyzer peaks below 85 bp (Primer dimers) [44] | - Incomplete removal of primers after PCR cleanup | - Clean up PCR reaction again with 0.9X AMPure beads [44] |

| High-molecular weight peak (~1,000 bp) [44] | - PCR over-amplification | - Reduce the number of PCR cycles [44] |

| Broad library size distribution [44] | - Under-fragmentation of RNA | - Increase RNA fragmentation time [44] |

| Low percentage of reads mapping to target after depletion [46] | - DNA contamination in input RNA- Compromised probe integrity- Incorrect target sequence used for probe design | - Treat sample with DNase I and purify- Verify probe integrity and storage conditions- Ensure the target sequence used for design is RNA, not cDNA [46] |

Troubleshooting Bias in Library Preparation

Library preparation is a major source of bias in RNA-seq data [2]. The table below details common biases and methods for improvement.

| Bias Source | Description | Suggestion for Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| Priming Bias [2] | Random hexamer priming can cause non-uniform read coverage. | For small RNA sequencing, use adapters with random nucleotides (degenerate bases) at ligation boundaries to mitigate sequence-dependent bias [47]. |

| Adapter Ligation Bias [2] [47] | T4 RNA ligases have substrate preferences, favoring certain RNA sequences over others. | Use adapters with random nucleotides at the extremities to be ligated to increase sequence diversity and ligation efficiency [2]. |

| PCR Amplification Bias [2] | Preferential amplification of cDNA with neutral GC content; bias propagates through cycles. | - Use polymerases like Kapa HiFi [2].- Reduce the number of PCR cycles [2].- For high GC content, use additives like TMAC or betaine [2]. |

| mRNA Enrichment Bias [2] | 3'-end capture bias during poly(A) selection. | For a broader transcriptome view, use rRNA depletion instead of poly-A enrichment to capture non-coding RNAs [2]. |

| Fragmentation Bias [2] | Non-random fragmentation using RNase III reduces library complexity. | Use chemical treatment (e.g., zinc) for fragmentation instead of enzymatic methods [2]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Agilent RNA 6000 Pico Kit [43] | Accurately assesses RNA quantity and integrity (RIN) for low-concentration samples, a critical first step in sample QC. | Essential for quantifying ultra-low input and single-cell samples [43]. |

| Ribosomal RNA Depletion Kits [43] [46] | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA, dramatically increasing the percentage of informative mRNA and non-coding RNA reads. | Required for random-primed kits (e.g., SMARTer Stranded). Examples: RiboGone kit [43] or NEBNext RNA Depletion Core Reagent Set [46]. |

| NucleoSpin RNA XS Kit [43] | Purifies high-quality RNA from small sample sizes (e.g., up to 1x10^5 cultured cells) without a carrier. | Use of a poly(A) carrier is not recommended as it interferes with oligo(dT)-primed cDNA synthesis [43]. |

| SPRIselect / AMPure XP Beads [44] | Used for size-selective cleanup of DNA libraries, such as the removal of adapter dimers and primer artifacts. | A second cleanup (0.9X ratio) can resolve persistent adapter-dimer peaks [44]. |

| Degenerate Adapters [47] | Adapters with random nucleotides at ligation boundaries reduce sequence-specific ligation bias. | A key feature of kits like Bioo Scientific's NEXTflex V2 for small RNA sequencing, improving correlation with RT-qPCR data [47]. |

Experimental Workflow and Bias Mapping

RNA-seq Library Preparation Workflow

FAQs on RNA Quality and Degradation

What are the main challenges when working with RNA from FFPE samples?

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues present several specific challenges for RNA extraction and sequencing. The formalin fixation process causes chemical modifications including RNA fragmentation, cross-linking of nucleic acids with proteins, and oxidation. The paraffin embedding process further degrades nucleic acids through heat and dehydration. Consequently, RNA from FFPE samples is typically highly fragmented and chemically modified, which leads to lower yields and can introduce biases in downstream applications like RNA-seq. This results in challenges such as lower sequencing coverage, potential loss of transcript diversity, and the introduction of sequencing artifacts. [48] [49] [50]

What quality metrics are most reliable for assessing FFPE RNA?

For FFPE-derived RNA, traditional metrics like the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) are often not adequate. Research supports the use of fragmentation-based metrics and PCR-based methods:

- DV200 (Percentage of RNA fragments >200 nucleotides) is a key indicator. While one Illumina report suggested a DV200 of 70% as a threshold, recent peer-reviewed studies indicate that a DV100 >80% provides the best indication of success for whole transcriptome sequencing, correlating well with gene detection rates. [50]

- PCR-based methods (qPCR or ddPCR) can quantify amplifiable RNA, which is crucial for determining effective input quantity for library prep, as fragmentation and cross-links can make a portion of the RNA unusable. [50]