PolyA Selection vs. Ribosomal Depletion: The Ultimate Guide to Bulk RNA-Seq Methods

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on choosing between polyA selection and ribosomal depletion for bulk RNA-Seq.

PolyA Selection vs. Ribosomal Depletion: The Ultimate Guide to Bulk RNA-Seq Methods

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on choosing between polyA selection and ribosomal depletion for bulk RNA-Seq. It covers the foundational principles of each method, their specific applications across different sample types (including intact, degraded, and FFPE samples), and practical troubleshooting advice. By synthesizing current research and comparative data, the article delivers actionable insights for experimental design, optimization, and data validation to ensure accurate and reliable transcriptome profiling in both basic research and clinical contexts.

Core Principles: How PolyA Selection and Ribosomal Depletion Shape Your Transcriptome View

In the field of transcriptomics, bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has revolutionized our ability to profile gene expression comprehensively. The core of any RNA-seq workflow lies in the critical first step of library preparation: the removal of highly abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA) which can constitute over 80% of a total RNA sample, thereby allowing efficient detection of informative transcripts [1]. Two principal methodologies have emerged to address this challenge—positive selection for polyadenylated RNA (polyA selection) and negative depletion of rRNA (rRNA depletion). These techniques employ fundamentally different mechanisms that directly influence transcriptome coverage, data interpretation, and experimental outcomes [2].

This technical guide provides an in-depth comparison of these two cornerstone methods, framed within contemporary clinical and research contexts. We delineate their operational mechanisms, comparative performance metrics across different sample types, and provide structured experimental protocols to inform methodological selection for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in transcriptome analysis.

Core Mechanistic Principles

Positive Selection (PolyA+ Selection)

The polyA selection method operates on the principle of affinity capture. It utilizes oligo(dT) primers or beads that hybridize specifically to the polyadenylated tails present on mature eukaryotic messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and many long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) [2]. This hybridization allows for the direct purification and enrichment of these polyA+ transcripts from the total RNA pool. The process effectively excludes ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), transfer RNAs (tRNAs), small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs), small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs), and other non-polyadenylated transcripts such as replication-dependent histone mRNAs [2]. Consequently, the resulting library is highly enriched for the protein-coding fraction of the transcriptome.

Negative Depletion (rRNA Depletion)

In contrast, the rRNA depletion method functions via subtractive hybridization. This technique employs sequence-specific DNA probes that are complementary to the sequences of various cytoplasmic and mitochondrial ribosomal RNAs [2]. These DNA probes hybridize to the rRNAs within the total RNA sample, forming RNA-DNA hybrids. The hybrids are subsequently removed from the solution through enzymatic digestion (e.g., using RNase H) or magnetic bead-based affinity capture [2]. Unlike polyA selection, this method does not discriminate based on the presence of a polyA tail. The remaining RNA pool after depletion includes both polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated species, such as pre-mRNAs, many lncRNAs, histone mRNAs, and some viral RNAs [2].

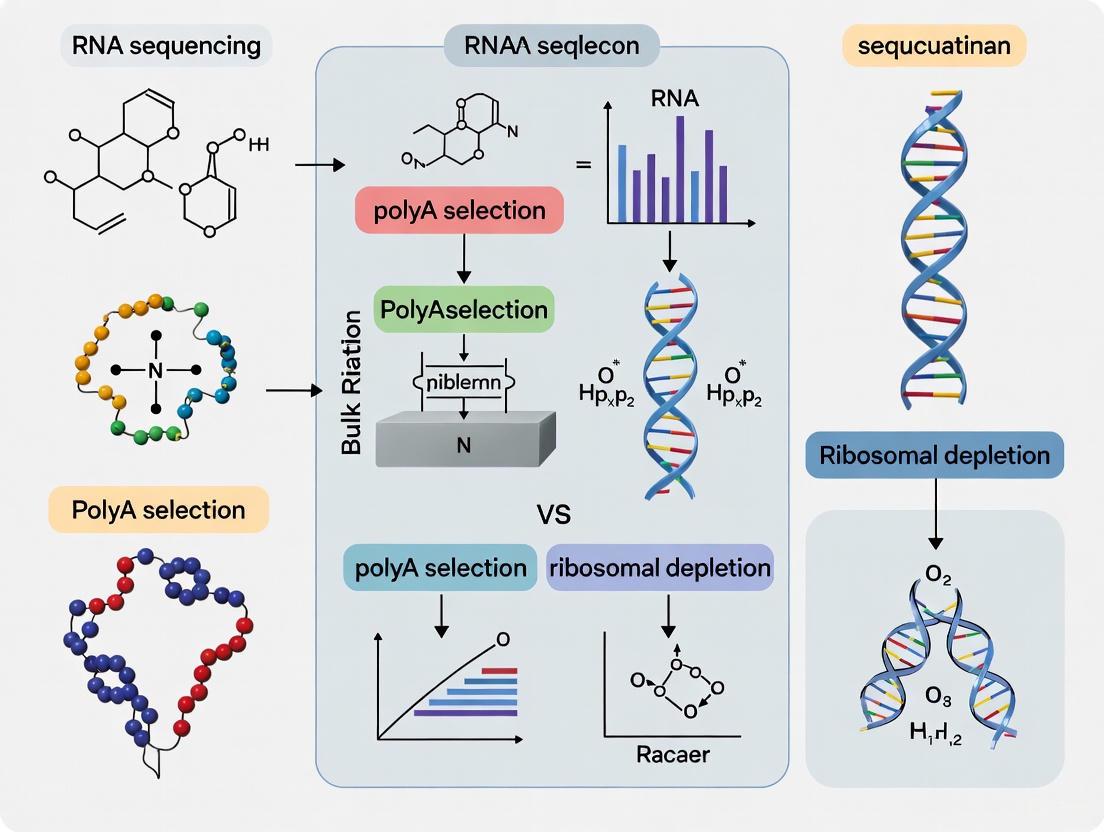

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental procedural differences between these two core methodologies:

Performance Comparison and Data Analysis

The choice between polyA selection and rRNA depletion has profound implications for data quality, content, and interpretation. A performance comparison based on clinical samples (human blood and colon tissue) reveals significant methodological differences [1].

Exonic Coverage and Sequencing Efficiency

A primary consideration in RNA-seq experimental design is sequencing efficiency, particularly the proportion of reads that map to exonic regions, which are most informative for gene-level quantification.

Table 1: Exonic Coverage and Sequencing Efficiency

| Sample Type | Method | Usable Exonic Reads | Required Increase in Sequencing Depth* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | PolyA+ Selection | 71% | Baseline |

| Blood | rRNA Depletion | 22% | 220% |

| Colon Tissue | PolyA+ Selection | 70% | Baseline |

| Colon Tissue | rRNA Depletion | 46% | 50% |

*To achieve exonic coverage equivalent to the polyA+ selection method. Data sourced from Zhao et al. (2018) [1].

The data demonstrates that polyA+ selection provides a substantially higher yield of usable exonic reads for gene quantification. The rRNA depletion method requires a significant increase in sequencing depth to achieve comparable exonic coverage, especially for blood-derived RNA [1]. This inefficiency stems from the fact that rRNA-depleted libraries capture a wider array of RNA biotypes, including intronic sequences from immature transcripts.

Transcriptome Feature Detection

While less efficient for exonic coverage, rRNA depletion offers a broader view of the transcriptome by capturing both polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated RNA species.

Table 2: Detected Transcriptome Features by RNA Biotype

| Gene Biotype | Detection by PolyA+ Selection | Detection by rRNA Depletion | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Coding Genes | Excellent | Excellent | PolyA+ is highly efficient for this class. |

| PolyA+ lncRNAs | Excellent | Excellent | |

| Non-PolyA+ lncRNAs | Not Detected | Detected | Includes histone mRNAs, some viral RNAs. |

| Pre-mRNAs / Nascent Transcripts | Minimal Detection | Significant Detection | Source of high intronic mapping rate. |

| Pseudogenes | Limited | Detected | |

| Small RNAs | Not Detected | Detected |

Analyses show that the rRNA depletion method captures a wider diversity of unique transcriptome features, including non-polyadenylated long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), pseudogenes, and small RNAs [1]. This comes at the cost of a significantly higher fraction of reads mapping to intronic regions, which reduces the efficiency of exon-level quantification but can provide valuable information on nascent transcription and transcriptional regulation [2].

Methodological Selection Guide

The decision between polyA selection and rRNA depletion is not a matter of one method being universally superior, but rather of selecting the right tool for the specific experimental context.

Table 3: Guidance for Method Selection in Experimental Design

| Experimental Situation | Recommended Method | Rationale | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eukaryotic RNA, High Quality (RIN ≥7) | PolyA+ Selection | Maximizes exonic coverage and power for gene-level differential expression. | Coverage skews toward the 3' end as RNA integrity decreases. |

| Degraded or FFPE RNA Samples | rRNA Depletion | More tolerant of RNA fragmentation; preserves 5' coverage better than polyA capture. | Intronic and intergenic fractions rise; confirm species-specific probe match. |

| Focus on Non-Polyadenylated RNAs | rRNA Depletion | Retains polyA+ and non-polyA species (e.g., histone mRNAs, many lncRNAs, pre-mRNA). | Residual rRNA can increase if probes are off-target. |

| Prokaryotic Transcriptomics | rRNA Depletion | PolyA+ capture is not appropriate for bacteria due to fundamentally different RNA biology. | Use species-matched rRNA probes for optimal depletion. |

| Low-Input RNA Protocols | Specialized Kits (e.g., SMART-Seq) | Methods using random primers (not oligo dT) are more suitable for degraded/low-input RNA [3]. | Performance can be improved by combining with rRNA depletion [3]. |

This guidance is corroborated by a 2024 study which found that for degraded RNA and low-input RNA, such as that from FFPE tissues, methods utilizing random primers (e.g., SMART-Seq) showed superior performance compared to standard polyA selection. Furthermore, the depletion of ribosomal RNA was shown to improve the performance of these methods by increasing expression level detection [3].

The following decision tree encapsulates the key selection criteria:

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure experimental reproducibility, this section outlines standardized protocols for both methods, incorporating best practices from the cited literature.

Protocol for PolyA+ Selection RNA-seq

Principle: Capture of polyadenylated RNA using surface-bound oligo(dT) probes [2] [1].

- Input Material: 10 ng–1 μg of high-quality total RNA (RIN ≥7 or DV200 ≥50%).

- Fragmentation: RNA is fragmented into 200–300 nucleotide pieces using heat and divalent cations.

- cDNA Synthesis: First-strand cDNA is synthesized using random hexamers and reverse transcriptase. Second-strand cDNA is synthesized using DNA Polymerase I and RNase H.

- Library Construction: Double-stranded cDNA undergoes end-repair, adenylation of 3' ends, and ligation of platform-specific sequencing adapters.

- Library Enrichment: Final libraries are enriched and amplified via PCR (typically 10-15 cycles).

- Quality Control: Assess library size distribution (e.g., Bioanalyzer) and quantify (e.g., qPCR).

Protocol for rRNA Depletion RNA-seq

Principle: Removal of ribosomal RNAs via hybridization to sequence-specific probes [1] [4].

- Input Material: 100 ng–1 μg of total RNA. Tolerates a wider range of RNA integrity.

- rRNA Removal: Total RNA is hybridized with biotinylated DNA probes complementary to cytoplasmic (5S, 5.8S, 18S, 28S) and mitochondrial rRNAs.

- Depletion: Probe-bound rRNA is removed using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads.

- Library Construction: The depleted RNA is purified and carried forward. Subsequent steps—fragmentation, cDNA synthesis, and library preparation—mirror the polyA+ selection protocol.

- Quality Control: As per polyA+ selection protocol. Additionally, check for residual rRNA content (e.g., using Bioanalyzer or RNA TapeStation).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq Library Preparation

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Method | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads | Affinity capture of polyA+ RNA | PolyA+ Selection | Efficiency drops significantly with degraded RNA. |

| Biotinylated rRNA Probes (e.g., Ribo-Zero, Globin-Zero) | Hybridize to and deplete rRNA sequences | rRNA Depletion | Probe specificity is critical; check for target organism. |

| Random Hexamer Primers | Initiate first-strand cDNA synthesis | Both | Used in both protocols after enrichment/depletion. |

| Template Switching Oligo | Used in SMART-Seq to generate full-length cDNA from low-input/degraded RNA [3] | Low-Input Methods | Enables sequencing of RNA where the 5' end is compromised. |

| Not-So-Random (NSR) Primers | Designed for more uniform reverse transcription | RamDA-Seq [3] | Aims to reduce bias in cDNA synthesis. |

| RNase H | Digests RNA in RNA-DNA hybrids | rRNA Depletion | Key enzyme in some depletion protocols. |

The strategic choice between positive polyA selection and negative rRNA depletion fundamentally shapes the scope and focus of an RNA-seq study. PolyA+ selection offers superior efficiency and precision for profiling mature, protein-coding mRNA, making it the default choice for intact eukaryotic samples where the research question centers on gene-level differential expression. In contrast, rRNA depletion provides a more comprehensive view of the transcriptome, encompassing non-coding and nascent transcripts, and demonstrates greater resilience with suboptimal sample types like FFPE tissues or samples with mixed RNA integrity. As the field advances, especially in clinical diagnostics where sample quality is often variable, the integration of method-specific performance metrics and the development of robust protocols for challenging samples will be paramount for unlocking the full potential of transcriptome sequencing in research and therapeutic development.

The choice between poly(A) selection and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion in bulk RNA-seq represents a fundamental methodological crossroads that directly dictates the resulting view of the transcriptome. This technical guide examines how each enrichment strategy defines the scope of biological investigation by capturing distinct RNA populations. Poly(A) selection provides a highly efficient, targeted view of protein-coding mRNA but systematically excludes entire classes of non-polyadenylated transcripts. In contrast, rRNA depletion offers a broader, more inclusive perspective of the transcriptional landscape, capturing both coding and non-coding RNA species, yet requires greater sequencing resources and careful optimization. The decision between these methods carries profound implications for experimental outcomes in gene expression studies, particularly in specialized applications involving degraded samples, prokaryotic partners, or non-coding RNA biology. This review synthesizes current evidence to equip researchers with a structured framework for selecting the optimal transcriptome coverage strategy based on specific experimental objectives, sample characteristics, and biological questions.

In bulk RNA-seq experiments, the transcriptome represents the complete set of RNA molecules present in a biological sample at a specific point in time. However, a fundamental challenge arises from the overwhelming abundance of ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which constitutes approximately 80-90% of total RNA in most cells [5]. This predominance of rRNA would consume the majority of sequencing resources if total RNA were sequenced directly, leaving limited capacity for profiling messenger RNA (mRNA) and other informative RNA species. Consequently, effective rRNA removal is a critical first step in most RNA-seq workflows, with two principal strategies employed: poly(A) selection and rRNA depletion.

These two methods operate on fundamentally different principles and consequently reveal different aspects of the transcriptome. Poly(A) selection is a positive enrichment strategy that targets the 3' polyadenylated tails characteristic of mature eukaryotic mRNA [6]. Conversely, rRNA depletion is a negative selection approach that uses hybridization probes to specifically remove rRNA molecules, preserving both polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated RNA species [7]. The choice between these methods directly determines which RNA molecules will be visible in subsequent analyses and which will be systematically excluded, thereby shaping all biological interpretations derived from the data.

Core Methodologies and Biological Basis

Poly(A) Selection: Targeting the 3' Tail

Biological Mechanism of Polyadenylation

The poly(A) selection method leverages a natural post-transcriptional modification process. In eukaryotic cells, mature messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules undergo 3' end processing whereby a stretch of 200-250 adenine nucleotides, known as a poly(A) tail, is added [6]. This tail serves critical biological functions: it protects the mRNA from degradation by exonucleases, facilitates nuclear export, and enhances translation efficiency by interacting with the 5' cap structure through protein intermediaries [6]. This conserved feature provides a molecular handle for selective mRNA capture.

Technical Protocol for Poly(A) Selection

The standard poly(A) selection protocol utilizes the base-pairing specificity between adenine and thymine to isolate polyadenylated RNA [6]. The workflow typically involves several key stages, as visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Poly(A) Selection Workflow. The process involves heat denaturation of total RNA followed by hybridization with oligo(dT) magnetic beads, washing to remove unbound RNA, and final elution of purified poly(A)+ RNA.

Following this general workflow, the specific procedural steps are critical for success:

Bead Preparation and RNA Denaturation: Oligo(dT) magnetic beads are resuspended, and total RNA is mixed with a high-salt binding buffer and heated to 65-70°C. This heat denaturation step is crucial for disrupting RNA secondary structures and making the poly(A) tails accessible for hybridization [6].

Annealing and Hybridization: The denatured RNA is incubated with the oligo(dT) beads at room temperature for 30-60 minutes. During this phase, the poly(A) tails of mRNA specifically bind to the complementary oligo(dT) sequences on the beads through A-T base pairing, which is stabilized by the high-salt buffer [6].

Washing and Elution: The bead-mRNA complex is captured using a magnet, and the supernatant containing non-polyadenylated RNA (rRNA, tRNA, etc.) is discarded. Multiple washes with high-salt buffer remove contaminants. Finally, purified poly(A)+ mRNA is eluted using low-salt buffer or nuclease-free water at 60-80°C, which disrupts the A-T bonds [6].

Protocol variations exist in bead-to-RNA ratios, incubation times, and wash stringency. Some workflows also perform cDNA synthesis directly on the beads to minimize sample loss [6].

rRNA Depletion: A Subtraction-Based Strategy

Biological Basis and Technical Principle

rRNA depletion takes a subtraction-based approach, directly targeting the abundant rRNA molecules for removal rather than positively selecting a specific RNA population. This method is independent of the polyadenylation status of transcripts, making it universally applicable across sample types, including those from prokaryotes [8]. The strategy relies on the design of sequence-specific probes that hybridize to rRNA molecules, followed by their physical removal or enzymatic degradation.

Two primary mechanisms are employed for rRNA removal:

- Probe Hybridization and Physical Removal: Biotinylated DNA oligonucleotides complementary to rRNA sequences are hybridized to total RNA. The resulting RNA-DNA hybrids are then captured and removed using streptavidin-coated paramagnetic beads [8].

- RNase H-Mediated Degradation: After hybridization of DNA probes to rRNA, the enzyme RNase H is introduced. This enzyme specifically cleaves the RNA strand of RNA-DNA hybrids, degrading the rRNA [8].

The efficiency of both methods depends critically on the specificity and comprehensive coverage of the designed probes against the target rRNA sequences (e.g., 18S, 28S, 5.8S, and 5S in eukaryotes) [7].

Detailed Protocol for Probe-Based rRNA Depletion

A robust protocol for customized rRNA depletion using biotinylated oligos is detailed below and illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. rRNA Depletion Workflow. The process involves hybridizing biotinylated DNA probes to rRNA in total RNA, capturing the probe-rRNA complexes with streptavidin beads, and separating the beads to leave an rRNA-depleted sample.

Key experimental steps and considerations include:

Probe Design: Probes (typically 25-50 bp) are designed to be complementary to the 5', middle, and 3' regions of major rRNA transcripts (e.g., 28S alpha, 28S beta, 18S) to ensure depletion of both full-length and degraded rRNA. Specificity must be verified using tools like BLAST to minimize off-target hybridization to non-rRNA transcripts [8].

Hybridization and Capture Optimization: Total RNA is hybridized with a pool of biotinylated oligonucleotide probes. Empirical testing is required to determine the optimal template-to-probe ratio; a mass ratio of 1:2 (RNA:probes) is often effective [8]. For example, 2 µg of total RNA may be hybridized with 4 µg of probes.

Bead-Based Removal and Iterative Depletion: Streptavidin-coated paramagnetic beads are added to capture the biotinylated probe-rRNA complexes. The beads are magnetically separated, and the supernatant containing the rRNA-depleted RNA is recovered. Multiple rounds of depletion (e.g., three rounds) may be necessary to reduce rRNA content to below 5% of total RNA [8].

Comparative Analysis: Coverage, Applications, and Limitations

Direct Comparison of Technical Performance

The choice between poly(A) selection and rRNA depletion involves trade-offs across multiple performance parameters, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Technical Comparison: Poly(A) Selection vs. rRNA Depletion

| Feature | Poly(A) Selection | rRNA Depletion |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Target | Mature poly(A)+ mRNA [2] | Both poly(A)+ and non-poly(A) RNAs [2] |

| Ideal RNA Integrity | Requires high integrity (RIN ≥7) [2] | Works with degraded/FFPE RNA [9] [2] |

| Transcriptome Breadth | Narrow (protein-coding mRNA focus) [6] | Broad (coding & non-coding RNAs) [7] |

| Coverage Uniformity | 3' bias, especially in degraded RNA [7] | More uniform 5' to 3' coverage [7] |

| Sequencing Efficiency | High (fewer reads needed for mRNA) [6] | Lower (more reads required) [6] |

| Organism Applicability | Eukaryotes only [2] | Eukaryotes and prokaryotes [10] |

| Key Limitations | Misses non-poly(A) RNAs (e.g., histone mRNAs, many lncRNAs) [2] [6] | Higher cost per sample; potential residual rRNA [6] |

Quantitative Performance in Experimental Studies

Empirical studies directly comparing these methods provide critical insights for experimental planning. Table 2 summarizes key quantitative findings from published research.

Table 2. Experimental Performance Metrics from Comparative Studies

| Study & Context | Poly(A) Selection Performance | rRNA Depletion Performance | Biological Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ma et al., 2019 (Murine Liver) [9] | Detected more differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Read distribution biased toward longer transcripts. | Fewer DEGs detected, but captured key pathways reliably. Less sensitive to transcript length. | Both methods yielded highly similar biological conclusions for pathway enrichment, despite differences in DEG count. |

| Fieth et al., 2022 (Sponge Holobiont) [10] | Effective for eukaryotic host transcriptome. Very poor for capturing bacterial symbiont mRNAs. | Effective for simultaneous capture of both host eukaryotic and bacterial symbiont transcriptomes. | rRNA depletion is the required method for holistic host-symbiont (holobiont) transcriptomic profiling. |

| Wrobel et al., 2019 (Custom Depletion) [8] | N/A in this study. Poly(A) enrichment misses many non-coding and immature transcripts. | Reduced rRNA to <5% with 12 custom probes. 50 non-rRNA transcripts showed co-depletion. | Custom rRNA depletion is highly efficient and specific, providing a viable alternative for non-model organisms. |

| Chung et al., 2015 (Sequencing Efficiency) [6] | ~50% fewer reads needed in colon, ~220% fewer in blood for similar gene-level coverage vs. depletion. | Requires significantly more sequencing depth to achieve exonic coverage comparable to poly(A) selection. | Poly(A) selection is more resource-efficient for standard mRNA profiling. |

Suitability and Limitations by Research Application

Optimal Applications for Poly(A) Selection

- Standard Gene Expression Profiling: When the research question focuses exclusively on differential expression of protein-coding genes in eukaryotic systems with high-quality RNA, poly(A) selection is the most efficient and cost-effective choice [9] [6].

- High-Throughput Studies: For large-scale screening experiments involving many samples (e.g., drug screening, genetic perturbations), the lower sequencing depth requirement makes poly(A) selection economically advantageous [9].

- 3' mRNA-Seq (QuantSeq): Specialized applications like QuantSeq, which use oligo(dT) priming for library construction, are ideal for rapid, cost-effective gene expression quantification, particularly from challenging sample types like FFPE material [9].

When rRNA Depletion is Mandatory or Preferred

- Prokaryotic Transcriptomics or Host-Symbiont Studies: Bacterial mRNAs lack stable poly(A) tails, making rRNA depletion the only viable option. This is also critical for dual RNA-seq of infected tissues or holobiont systems [10].

- Analysis of Non-Polyadenylated RNAs: Studies focusing on long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), circular RNAs, histone mRNAs, or other non-coding RNAs that lack poly(A) tails require rRNA depletion [2] [6].

- Degraded or FFPE Samples: When working with archived clinical samples (FFPE) or other degraded RNA where the poly(A) tail may be lost or compromised, rRNA depletion provides more robust and uniform transcript coverage [9] [2].

- Analysis of Transcriptional Dynamics: rRNA depletion retains pre-mRNA and intronic reads, which can be leveraged to study nascent transcription, splicing kinetics, and other transcriptional regulatory mechanisms [2].

Successful implementation of poly(A) selection or rRNA depletion requires specific reagents and careful quality control. Table 3 outlines key components of the experimental toolkit.

Table 3. Research Reagent Solutions for Transcriptome Enrichment

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads | Capture poly(A)+ RNA via hybridization to the poly(A) tail. | Core component of poly(A) selection kits. Bead-to-RNA ratio is critical for yield [6]. |

| Biotinylated DNA Probes | Sequence-specific probes hybridize to rRNA for depletion. | Can be commercial kits or custom-designed for model and non-model organisms [8]. |

| Streptavidin Paramagnetic Beads | Capture and remove biotinylated probe-rRNA complexes. | Used in custom and some commercial rRNA depletion protocols [8]. |

| RNase H | Enzyme that degrades RNA in RNA-DNA hybrids. | Used in RNase H-mediated depletion protocols (e.g., NEB kits) to degrade rRNA [8]. |

| High-Salt Binding Buffer | Stabilizes A-T base pairing during hybridization. | Essential for efficient capture in poly(A) selection [6]. |

| RNA Integrity Analyzer (e.g., Bioanalyzer) | Assesses RNA Quality (RIN/DV200) pre- and post-enrichment. | Critical for QC; DV200 is particularly informative for FFPE samples [2]. |

The decision between poly(A) selection and rRNA depletion is foundational, irrevocably shaping the scope and validity of transcriptomic findings. There is no universally superior method; the optimal choice is dictated by the specific biological question, sample characteristics, and available resources.

For research focused exclusively on protein-coding gene expression in eukaryotes with high-quality RNA, poly(A) selection remains the most efficient and targeted approach. However, for investigations requiring a comprehensive view of the transcriptional landscape—including non-coding RNAs, bacterial transcripts, or samples with compromised RNA integrity—rRNA depletion is the indispensable, albeit more resource-intensive, alternative.

As the field advances with emerging applications in single-cell biology, spatial transcriptomics, and precision medicine, the principles outlined in this guide will continue to inform experimental design. By aligning methodological strengths with specific research objectives, scientists can ensure their chosen path through the transcriptomic landscape reveals the biological insights they seek, rather than the artifacts of their chosen method.

In bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), the choice between polyadenylated (polyA) selection and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion is a fundamental upstream decision that profoundly shapes the composition and interpretation of sequencing data [2]. This choice is particularly decisive for the relative proportions of reads mapping to exonic, intronic, and intergenic regions of the genome. These mapping distributions are not merely technical artifacts; they reflect the underlying biology of the RNA species captured and have direct implications for the accuracy of gene quantification, the detection of novel features, and the biological conclusions that can be drawn.

PolyA selection enriches for mature, protein-coding mRNA by capturing RNAs with polyA tails using oligo-dT primers, thereby focusing the dataset on spliced transcripts. In contrast, rRNA depletion removes abundant ribosomal RNAs from total RNA, preserving a much broader spectrum of RNA species, including pre-mRNA, non-polyadenylated long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and other non-coding RNAs [2] [11]. The core distinction lies in the fact that polyA selection targets a specific RNA feature (the tail), while rRNA depletion targets specific RNA sequences (rRNA). This fundamental difference cascades through the entire data analysis pipeline, resulting in distinctly structured datasets.

Quantitative Impact on Read Distribution

The methodological difference between library preparations leads to starkly divergent profiles in where reads map across the genome. The table below summarizes the typical distribution of reads from polyA-selected and rRNA-depleted libraries in different biological contexts.

Table 1: Comparison of Read Distribution Profiles between Library Prep Methods

| Sample Type | Library Method | Exonic Reads | Intronic Reads | Intergenic Reads | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Blood | polyA+ Selection | ~71% | Lower | Lower | [1] |

| Human Blood | rRNA Depletion | ~22% | Substantially Higher (~50% of bases) | Substantially Higher | [1] [12] |

| Human Colon | polyA+ Selection | ~70% | Lower | Lower | [1] |

| Human Colon | rRNA Depletion | ~46% | Substantially Higher (~33% of bases) | Substantially Higher | [1] [12] |

| Human Breast Tumor (FF) | polyA+ Selection | 62.3% | Lower | Lower | [12] |

| Human Breast Tumor (FF) | rRNA Depletion | 20-30% | Majority of reads | Majority of reads | [12] |

| D. melanogaster | polyA+ Selection | Highest | Lower | Higher than intronic | [13] |

| D. melanogaster | rRNA Depletion | Highest (but lower than polyA+) | Higher than polyA+ | Lower than polyA+ | [13] |

The data reveals a consistent pattern: rRNA depletion libraries consistently yield a significantly lower fraction of exonic reads and a concomitantly higher fraction of intronic and intergenic reads compared to polyA-selected libraries. This effect is so pronounced that for a blood sample, 220% more reads must be sequenced with rRNA depletion to achieve the same level of exonic coverage as polyA+ selection; for colon tissue, this number is 50% [1]. This has major implications for sequencing cost and the effective depth of coverage for the target transcriptome.

Biological and Technical Origins of Read Types

The observed data structure is a direct consequence of the RNA species captured by each method.

Intronic reads are a hallmark of rRNA-depleted libraries, but their presence can be attributed to several biological and technical factors:

- Nascent Transcription and Pre-mRNA: A primary source of intronic signal is the capture of unspliced pre-mRNA by rRNA depletion. These transcripts contain intronic sequences that have not yet been removed by the splicing machinery [14]. This is not merely "contamination" but a reflection of transcriptional activity. Studies have shown that longer introns tend to have higher RNA-seq coverage in rRNA-depleted data, supporting the model of co-transcriptional splicing, where splicing occurs while the RNA polymerase is still transcribing the gene [14].

- Genomic DNA Contamination: Trace amounts of genomic DNA (gDNA) contaminating the RNA sample can align to intronic (and intergenic) regions. Unlike pre-mRNA, gDNA contamination typically produces reads mapping to both strands of the intron [14].

- Stable Intronic RNAs and Non-Coding RNAs: Some intronic sequences give rise to functional non-coding RNAs or stable lariat RNAs, which can be captured by rRNA depletion [14].

- Unannotated Transcripts and Exons: Some intronic reads may point to previously unannotated exons or transcript isoforms not present in the reference annotation [14].

Intergenic reads, which map outside of annotated gene boundaries, are also more abundant in rRNA-depleted data. Their origins include:

- Non-polyadenylated Non-Coding RNAs: rRNA depletion captures a wide array of non-coding RNAs (e.g., some lncRNAs, enhancer RNAs) that are not polyadenylated and may be located in intergenic regions [1] [2].

- Novel Transcripts: These reads can indicate the presence of entirely novel, unannotated transcripts.

- Genomic DNA Contamination: Similar to intronic reads, gDNA contamination will also contribute to intergenic signals.

polyA+ Selection Minimizes Non-Exonic Reads

PolyA selection effectively minimizes intronic and intergenic reads by design. Since it captures only RNAs with polyA tails, it selectively enriches for mature, spliced mRNAs, where introns have been removed. It also excludes the majority of non-polyadenylated non-coding RNAs. Consequently, the resulting data is highly concentrated on exonic regions, providing high power for protein-coding gene quantification [1] [2].

Diagram 1: How library prep defines RNA species and read types. polyA+ selection filters for mature mRNA, leading to high exonic reads. rRNA depletion retains a mixed population, resulting in high intronic and intergenic reads.

Experimental Protocols for Comparative Analysis

To ensure reproducible and accurate comparisons between polyA selection and rRNA depletion, a standardized experimental and computational workflow is essential. The following protocol, synthesized from multiple studies, provides a robust framework.

Sample Preparation and Library Construction

- RNA Extraction: Isolate total RNA from the biological material of interest (e.g., human blood, colon tissue, cell lines) using a standardized kit (e.g., Zymo Research RNA Clean and Concentrator [11]). RNA Integrity Number (RIN) or RQS/DV200 values should be assessed (e.g., via Agilent Bioanalyzer) [1] [2].

- Library Preparation (in parallel):

- polyA+ Selection: Use a kit such as SMARTSeq V4 (Takara) that employs oligo-dT primers to capture and reverse-transcribe polyadenylated RNA [11].

- rRNA Depletion: Use a ribodepletion kit such as Ribo-Zero Gold (Illumina) or SoLo Ovation (Tecan). For non-model organisms, ensure the use of species-specific probes (e.g., a custom 200-probe set for C. elegans rRNA sequences) [11].

- Sequencing: Sequence all libraries on a platform such as Illumina to a sufficient depth (e.g., 50 million reads per replicate) using paired-end sequencing [1].

Computational Analysis and QC Pipeline

A unified computational pipeline, such as the Transcriptome Analysis Pipeline (TAP), should be used to process all data uniformly [13].

- Alignment: Perform splicing-aware alignment to the reference genome (e.g., GRCh38 for human) using a aligner such as STAR [13] [15].

- Read Classification: Classify aligned reads based on their overlap with genomic annotations (GTF file). A standard definition is:

- Quantification: Generate gene-level counts using tools like HTSeq or Salmon, considering only exonic reads for classical gene expression analysis [17] [13].

- Quality Control:

Diagram 2: Unified workflow for comparing library methods. Samples are processed in parallel through library prep, then analyzed with a single pipeline to ensure consistent comparison.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMARTSeq V4 | Library Prep Kit | polyA+ selection for full-length cDNA | Optimal for intact, eukaryotic RNA [11]. |

| Ribo-Zero Gold | Library Prep Kit | Depletion of cytoplasmic rRNA from human/mouse/rat | Standard for human clinical samples; less efficient in non-models [1] [12]. |

| Ovation SoLo with Custom AnyDeplete | Library Prep Kit | rRNA depletion with custom probes | Essential for non-model organisms (e.g., C. elegans) [11]. |

| RNA Clean & Concentrator | RNA Purification Kit | Cleanup and concentration of RNA post-extraction | Critical for obtaining high-quality input material [11]. |

| Agilent Bioanalyzer | Instrument | Assesses RNA Integrity (RIN) | RIN ≥7 recommended for polyA+ selection [2]. |

| STAR Aligner | Software | Splicing-aware alignment of RNA-seq reads to a genome | Standard for accurate read mapping and junction detection [15]. |

| Picard Tools | Software Suite | Generates QC metrics (e.g., read distribution) | CollectRnaSeqMetrics is key for data structure analysis [18]. |

| MultiQC | Software | Aggregates results from multiple tools into a single report | Essential for visualizing and comparing QC metrics across samples [18]. |

The choice between polyA selection and rRNA depletion is not a matter of one method being universally superior, but rather of selecting the right tool for the specific research objective. The resulting data structure—defined by the balance of exonic, intronic, and intergenic reads—is a direct and predictable outcome of this choice.

- For primary focus on protein-coding gene expression: polyA+ selection is the recommended method. It delivers superior exonic coverage, higher power for differential expression at a given sequencing depth, and is more cost-effective for this specific goal [1] [2].

- For exploratory transcriptomics or studies of non-coding RNA: rRNA depletion is necessary. It is essential for capturing non-polyadenylated RNAs (lncRNAs, pre-mRNAs, histone mRNAs) and provides a more complete picture of transcriptional activity [1] [11].

- For degraded or FFPE samples: rRNA depletion is strongly preferred due to its resilience to RNA fragmentation, as it does not rely on an intact 3' polyA tail [12] [2].

Ultimately, the decision must be guided by the biological question, the organism, and the quality of the input RNA. Researchers must be aware that the data structure resulting from their chosen protocol directly influences the analytical strategies required and the biological interpretations that can be made.

The Critical Role of RNA Integrity (RIN) in Method Selection

In bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), the choice between poly(A) selection and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion is a foundational experimental decision. The integrity of the input RNA sample, most commonly quantified as the RNA Integrity Number (RIN), is a critical determinant for this choice, directly influencing data quality, coverage, and biological conclusions. RIN scores, typically ranging from 1 (degraded) to 10 (intact), provide a standardized measure of RNA quality by evaluating the ratio of ribosomal RNA bands. When RNA degrades, transcripts fragment and often lose their poly(A) tails, creating a fundamental compatibility issue with poly(A) selection protocols. This technical guide examines how RIN values should guide the selection between poly(A) selection and rRNA depletion, providing a structured framework for researchers to optimize their transcriptomics studies within the broader context of gene expression research.

How RNA Integrity Affects Library Preparation Methods

The Fundamental Mechanisms of Poly(A) Selection and rRNA Depletion

The core mechanisms of the two major enrichment strategies explain their differing dependencies on RNA integrity.

Poly(A) Selection relies on oligo(dT) beads or similar matrices to hybridize and capture RNA molecules bearing polyadenylated tails. This process specifically enriches for mature, polyadenylated messenger RNA (mRNA) by leveraging the base pairing between thymine residues on the beads and adenine residues in the poly(A) tail [6]. The protocol typically involves denaturing total RNA to expose the poly(A) tail, incubating with oligo(dT) beads for hybridization, washing away non-polyadenylated RNA species, and finally eluting the purified mRNA [6]. This mechanism effectively targets a specific biochemical feature—the 3' poly(A) tail—making it highly dependent on the preservation of this terminal structure.

rRNA Depletion operates on a different principle, using sequence-specific DNA probes designed to hybridize to abundant ribosomal RNA sequences (both cytoplasmic and mitochondrial). These probe-rRNA hybrids are subsequently removed through RNase H digestion or affinity capture, leaving behind a complex pool of both polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated RNA species [2]. This "negative selection" approach does not depend on any single RNA feature but rather removes specific unwanted targets, making it more resilient to partial RNA degradation.

Impact of RNA Degradation on Transcript Capture

RNA degradation typically proceeds in a 5'→3' direction, often involving deadenylase enzymes that progressively shorten the poly(A) tail—the very feature targeted by poly(A) selection [6]. As integrity decreases:

- For poly(A) selection: Degraded RNA with shortened or missing poly(A) tails fails to hybridize efficiently with oligo(dT) beads, leading to significant capture bias toward intact transcripts and under-representation of affected molecules [2] [6].

- For rRNA depletion: Since this method does not depend on the 3' tail for capture, fragmented RNA molecules retaining their probe-binding regions can still be effectively depleted of rRNA, allowing more representative sampling of the remaining transcriptome [2] [19].

The following diagram illustrates the core methodological differences and their relationship with RNA integrity:

Quantitative Data Comparison: Method Performance Across RIN Values

Coverage and Bias Metrics

RNA integrity directly impacts sequencing coverage distribution and gene detection capability differently for each method. The following table summarizes key quantitative differences observed across RIN values:

Table 1: Performance Metrics of RNA Enrichment Methods Across RIN Values

| Performance Metric | Poly(A) Selection | rRNA Depletion |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum Recommended RIN | 7-8 [2] | No strict minimum [2] |

| 3' Bias with Degradation | Severe (strong skew toward 3' end) [2] [6] | Minimal (more uniform coverage) [2] |

| Exonic Mapping Rate | High (70-85%) [2] [20] | Moderate (50-70%) with higher intronic reads [2] |

| Residual rRNA | Typically <1% [2] | 5-20% (probe-dependent) [2] [11] |

| Typical Sequencing Depth | 25-40 million reads [4] [20] | 50-80 million reads [4] |

| Detection of Non-polyA Transcripts | No [2] [6] | Yes (lncRNAs, histone mRNAs, etc.) [2] [6] |

Experimental Validation Studies

Empirical studies directly comparing both methods across RNA quality gradients provide compelling evidence for RIN-based selection:

A paired-design study using human CD4+ T cells from 40 donors with RIN values >8.6 demonstrated that while both methods perform well with high-quality RNA, significant divergences emerge with controlled degradation [4]. Poly(A) selection showed progressively stronger 3' bias as integrity decreased, while rRNA depletion maintained more uniform transcript coverage.

Research on low-input C. elegans samples found that rRNA depletion with species-specific probes provided superior performance for degraded samples, detecting an expanded set of noncoding RNAs and showing reduced noise for lowly expressed genes compared to poly(A) selection methods [11].

A comprehensive analysis of fragmented and FFPE (Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded) RNA samples concluded that rRNA depletion "is more resilient on fragmented and FFPE RNA" and "usually preserves 5′ coverage better than poly(A) capture" [2]. FFPE samples typically have RIN values below 4, making them largely incompatible with poly(A) selection.

Method Selection Framework and Experimental Protocols

Decision Matrix for Method Selection

The following structured framework integrates RIN values with experimental objectives to guide appropriate method selection:

Table 2: RNA-Seq Method Selection Guide Based on RIN and Research Goals

| Situation | Recommended Method | Rationale | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eukaryotic RNA, RIN ≥8, coding mRNA focus | Poly(A) selection | Concentrates reads on exons; maximizes power for gene-level differential expression [2] | Check RNA quality using Bioanalyzer/TapeStation; expect high exonic mapping rates |

| RIN 5-7, eukaryotic samples | rRNA depletion | Tolerant of partial fragmentation; preserves coverage of transcript 5' ends [2] | Use species-matched probes; sequence more deeply to compensate for lower efficiency |

| RIN <5, FFPE, or heavily degraded | rRNA depletion | Does not rely on intact 3' tails; most resilient option for compromised samples [2] | Expect higher intronic/intergenic reads; requires careful probe selection |

| Need non-polyadenylated RNAs | rRNA depletion | Retains both poly(A)+ and non-poly(A) species (lncRNAs, histone mRNAs, pre-mRNAs) [2] [6] | Confirms detection of target non-coding RNAs in pilot data |

| Prokaryotic transcriptomics | rRNA depletion | Poly(A) capture inappropriate for bacterial mRNA [2] | Essential to use species-matched rRNA probes |

| Mixed-quality sample cohort | rRNA depletion (for consistency) | Single protocol performs adequately across all quality levels [2] | Avoids protocol-switching artifacts in integrated analysis |

Practical Implementation Protocols

Poly(A) Selection Protocol (adapted from [6]):

- Bead Preparation: Resuspend oligo(dT) magnetic beads thoroughly to ensure even distribution.

- RNA Denaturation: Mix 100ng-5μg total RNA with high-salt binding buffer. Heat to 65-70°C for 2 minutes to disrupt secondary structures, then immediately place on ice.

- Hybridization: Combine denatured RNA with beads. Incubate at room temperature for 30-60 minutes with gentle mixing to allow poly(A)-oligo(dT) hybridization.

- Washing: Place tube on magnet, discard supernatant. Wash beads 2-3 times with high-salt buffer to remove non-specifically bound RNA.

- Elution: Add warm (60-80°C) low-salt buffer or nuclease-free water to release purified poly(A)+ RNA.

- Quality Control: Assess yield and purity (e.g., Bioanalyzer). Proceed to library construction.

Key Considerations: Bead-to-RNA ratio is critical; insufficient beads reduce yield while excess may increase non-specific binding [6]. For low-input samples (<100 ng), consider specialized low-input protocols.

rRNA Depletion Protocol (adapted from [2] [19]):

- Probe Hybridization: Mix total RNA (10ng-1μg) with sequence-specific DNA probes targeting rRNA species. Heat to 70°C for 2 minutes, then incubate at relevant temperature (probe-specific) for 10-15 minutes.

- rRNA Removal:

- RNase H Method: Add RNase H to digest RNA in DNA-RNA hybrids. Follow with purification to remove fragments.

- Affinity Capture Method: Use bead-coupled probes or biotinylated probes with streptavidin beads to physically remove rRNA complexes.

- Purification: Recover depleted RNA using column-based or bead-based clean-up.

- Quality Control: Assess depletion efficiency (e.g., Bioanalyzer, qPCR for residual rRNA). Residual rRNA >20% may indicate probe mismatch.

Key Considerations: Species-specific probe design is essential, particularly for non-model organisms [2] [11]. Pilot testing is recommended when working with novel species or sample types.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for RNA Selection Methods

| Reagent / Resource | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads | Capture polyadenylated RNA via hybridization | Core component of poly(A) selection; enables automation [6] |

| Sequence-Specific rRNA Probes | Hybridize to ribosomal RNA for depletion | Species-matched design critical for efficiency [2] [11] |

| RNase H Enzyme | Digests RNA in DNA-RNA hybrids | Key for enzymatic rRNA depletion methods [2] |

| High-Salt Binding Buffer | Stabilizes A-T base pairing | Critical for poly(A) selection efficiency [6] |

| Magnetic Separation Stand | Immobilizes magnetic beads during washes | Essential for both methods during wash steps |

| Bioanalyzer/TapeStation | Assesses RNA integrity and library quality | Critical for RIN determination and QC pre-/post-selection |

| DNase I | Removes genomic DNA contamination | Important for accurate RNA quantification [20] |

RNA Integrity Number serves as a pivotal decision point in the choice between poly(A) selection and rRNA depletion for bulk RNA-seq. The fundamental relationship is straightforward: as RIN decreases, the advantage shifts decisively toward rRNA depletion.

For researchers designing transcriptomics studies, the following best practices are recommended:

- Always quantify RNA integrity using standardized methods (RIN, DV200) before selecting library preparation method.

- Establish sample quality thresholds specific to your research objectives, with RIN ≥8 for poly(A) selection and no strict minimum for rRNA depletion.

- Employ rRNA depletion for heterogeneous sample cohorts where RNA quality varies, as it provides more consistent performance across quality levels.

- Validate probe specificity when working with non-model organisms or specialized sample types.

- Anticipate sequencing depth needs based on method selection—rRNA depletion typically requires 1.5-2× greater sequencing depth than poly(A) selection for similar gene detection sensitivity.

By aligning method selection with RNA integrity metrics and experimental goals, researchers can optimize data quality, maximize informational yield, and ensure biologically meaningful results from their transcriptomics investments.

Strategic Application: Choosing the Right Method for Your Sample and Research Question

A critical, irreversible first step in any bulk RNA-sequencing experiment is the choice of how to handle the overwhelming abundance of ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which constitutes 80-98% of the total RNA in a typical mammalian cell [21] [22]. This decision determines which RNA molecules enter the sequencing library and fundamentally shapes all downstream data and analyses [2]. The two principal strategies are poly(A) selection, which enriches for polyadenylated transcripts, and rRNA depletion (ribodepletion), which removes rRNA and sequences the remaining transcriptome [2] [23]. This guide provides a structured framework for choosing between these methods based on three core factors: the organism of study, the quality of the input RNA, and the specific transcripts of interest, all within the context of optimizing bulk RNA-seq research.

Core Principles: poly(A) Selection vs. rRNA Depletion

poly(A) Selection: Capturing the Tailed Transcriptome

Mechanism: This method leverages the polyadenylated tails found on most mature eukaryotic messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and some long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs). Through hybridization with oligo(dT) primers or beads, these tailed transcripts are selectively captured from the total RNA pool [2] [23].

Captured Transcripts:

- Included: Mature eukaryotic mRNA, many polyadenylated lncRNAs.

- Excluded: rRNA, transfer RNA (tRNA), small nuclear/nucleolar RNA (sn/snoRNA), and non-polyadenylated mRNAs such as replication-dependent histone mRNAs [2] [24].

rRNA Depletion: A Broader View of the Transcriptome

Mechanism: This method uses sequence-specific DNA or RNA probes that are complementary to rRNA sequences (e.g., 5S, 5.8S, 18S, 28S). The probe-rRNA hybrids are subsequently removed from the sample, typically via RNase H digestion or magnetic bead capture [2] [25].

Captured Transcripts:

- Included: Both poly(A)+ and non-polyadenylated species. This includes mature mRNA, pre-mRNA (containing introns), many lncRNAs, histone mRNAs, and some viral RNAs [2] [26].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflows and outcomes of these two methods.

The Decision Framework: A Three-Filter Approach

The optimal enrichment method is determined by systematically evaluating the organism, RNA integrity, and target transcripts [2]. The following table provides a consolidated overview for quick comparison.

Table 1: Method Selection Framework for poly(A) Selection vs. rRNA Depletion

| Filter | Criteria | Recommended Method | Key Rationale | Potential Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | Eukaryotic (good annotation) | poly(A) Selection | Efficiently targets mature, polyadenylated mRNA [2] [23]. | Misses non-poly(A) RNAs; not suitable for prokaryotes [2]. |

| Prokaryotic, Archaeal, or Metatranscriptomic | rRNA Depletion | Necessary as bacterial mRNA lacks stable poly(A) tails [2] [25]. | Requires species-matched probes to avoid high residual rRNA [2] [25]. | |

| RNA Integrity | Intact (RIN/RQS ≥ 7, DV200 ≥ 50%) | poly(A) Selection | Provides high exonic fractions, optimal for gene-level DE analysis [2]. | Coverage skews strongly to the 3' end as integrity drops [2] [9]. |

| Degraded or FFPE | rRNA Depletion | More resilient to fragmentation; better preserves 5' coverage [2] [9]. | Intronic/intergenic fractions rise; may need deeper sequencing [2] [26]. | |

| Target Transcripts | Mature, coding mRNA | poly(A) Selection | Concentrates reads on exons, boosting power for gene-level DE [2]. | Loss of non-coding and nascent transcriptional signal [2] [24]. |

| Non-polyadenylated RNAs (e.g., histone mRNAs, many lncRNAs, pre-mRNA) | rRNA Depletion | Retains both poly(A)+ and poly(A)- species in one assay [2] [23]. | Higher library complexity requires greater sequencing depth [26]. |

Impact on Data Output and Analysis

The choice of method directly shapes your data and its interpretation:

- poly(A) Selection Data: Characterized by high exonic mapping rates and relatively low residual rRNA. This concentrates sequencing power on annotated exons, which is ideal for statistical tests of differential gene expression. A key limitation is 3' bias, where coverage tilts toward the 3' end of transcripts, especially with partially degraded RNA. This can lead to under-representation of long transcripts [2] [26].

- rRNA Depletion Data: Yields a broader transcriptomic profile. The mapping rates will include significant intronic and intergenic fractions. Intronic reads can track nascent transcriptional activity, while exonic reads reflect post-transcriptional processed mRNA. Modeling these signals together allows researchers to separate transcriptional from post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms [2].

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Protocol for poly(A) Selection and Library Preparation

This protocol is adapted from standard practices for intact eukaryotic RNA [2] [27].

- Total RNA Quality Control: Verify RNA integrity using an Agilent Bioanalyzer. A RNA Integrity Number (RIN) or RQS of ≥7 is recommended [2].

- poly(A) RNA Capture:

- Incubate total RNA with oligo(dT) magnetic beads. The poly(A) tails of mature mRNAs hybridize to the oligo(dT) sequences.

- Use a magnetic stand to separate the bead-bound poly(A)+ RNA from the rest of the total RNA.

- Wash the beads to remove nonspecifically bound RNA, including rRNA and other non-poly(A) species.

- Elution: Elute the purified poly(A)+ RNA from the beads, typically using nuclease-free water or elution buffer at an elevated temperature.

- Stranded Library Preparation:

- Fragment the eluted RNA to a desired size distribution.

- Perform reverse transcription using random primers to generate first-strand cDNA.

- Synthesize the second strand. To preserve strand-of-origin information, incorporate dUTP in place of dTTP during second-strand synthesis [23].

- Perform end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation.

- Treat the library with Uracil-Specific Excision Reagent (USER) enzyme to digest the dUTP-containing second strand, ensuring only the first strand is amplified [23].

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the library with a limited number of PCR cycles using primers complementary to the adapters.

- Library QC: Quantify the final library and validate its size distribution using a Fragment Analyzer or similar system before sequencing.

Protocol for rRNA Depletion and Library Preparation

This protocol, suitable for a wide range of sample types including degraded RNA and prokaryotic samples, is based on hybridization and bead capture methods [2] [25].

- RNA Quality and DNA Digestion: Quality-check the total RNA. Ensure complete removal of genomic DNA with a rigorous DNase treatment, as any contaminating DNA will be sequenced and manifest as high intergenic read alignment [28].

- Hybridization with rRNA Probes:

- Denature the total RNA and hybridize it with a pool of biotinylated DNA oligonucleotides that are complementary to the rRNA sequences (e.g., for 5S, 16S, and 23S rRNAs in bacteria).

- Use species-matched probes for optimal efficiency. Probe mismatch is a common failure mode that leaves high residual rRNA [2] [25].

- rRNA Removal:

- Add streptavidin-coated magnetic beads to the hybridization mix. The biotin on the probes binds tightly to the streptavidin on the beads.

- Use a magnetic stand to capture the bead-probe-rRNA complexes, leaving the desired, rRNA-depleted RNA in the supernatant.

- Recovery of Depleted RNA: Carefully transfer the supernatant, which contains the enriched mRNA and other non-rRNA transcripts, to a new tube.

- Library Preparation:

- Since the RNA pool includes non-polyadenylated transcripts, use random primers for first-strand cDNA synthesis, not oligo(dT) primers [24].

- Follow steps for second-strand synthesis (optionally with dUTP for stranded libraries), adapter ligation, and PCR amplification as described in the poly(A) protocol.

- Library QC: Quantify and validate the final library as before.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for rRNA Depletion

| Kit/Reagent | Function/Basis | Key Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| riboPOOLs | DNA oligonucleotide probes, biotinylated for bead capture [25]. | Available as species-specific or pan-prokaryotic; shown to be an efficient replacement for discontinued RiboZero [25]. |

| RiboMinus | Biotinylated DNA probes for hybridization-based depletion [25]. | Pan-prokaryotic design; efficiency can be lower than species-specific options [25]. |

| NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit | Utilizes RNase H to digest DNA probe-rRNA hybrids [21]. | Effective for human/mouse/rat; requires careful handling to minimize off-target digestion [21] [25]. |

| Biotinylated Probes (Self-Designed) | Custom probes designed from rRNA gene sequences for magnetic bead capture [25]. | Allows for fully customized, cost-effective depletion; requires in-house design and validation [25]. |

| scDASH (CRISPR-based) | Post-library depletion using Cas9 nuclease to cleave rRNA cDNA sequences [21]. | Circumvents low-input limitations; applied after cDNA synthesis and amplification [21]. |

Troubleshooting Common Pitfalls

- High Residual rRNA in Depletion Workflows: This is most often caused by probe mismatch, especially when working with non-model organisms or pathogens [2] [25]. Solution: Pilot a few samples with different probe sets if available, and always check the percentage of rRNA reads in the initial sequencing data before scaling up the study. Consider using custom-designed probes [25].

- Strong 3' Bias in poly(A) Data: This indicates that the input RNA was more degraded than anticipated [2]. Solution: Do not try to solve this by simply sequencing deeper. For future samples of similar quality, switch to an rRNA depletion protocol, which is more tolerant of fragmentation [2].

- High Intergenic or Intronic Reads: In rRNA depletion data, this is expected and can be biologically informative (e.g., intronic reads indicate nascent transcription) [2]. However, if the rates are exceptionally high, it may indicate gDNA contamination [28]. Solution: Implement a secondary, rigorous DNase treatment during the RNA extraction or cleanup step [28].

The decision between poly(A) selection and rRNA depletion is a foundational one in bulk RNA-seq experimental design. There is no universal best choice; the optimal path is determined by a logical assessment of the organism being studied, the quality of the sourced RNA, and the specific transcriptional features under investigation. By applying the three-filter framework outlined in this guide—organism, RNA quality, and target transcripts—researchers can make a principled and defensible choice. Consistency is also critical; once a method is selected, it should be applied uniformly across all samples within a study to ensure robust and comparable results [2]. This structured approach ensures that the upstream RNA enrichment strategy is optimally aligned with the downstream biological questions, maximizing the value and reliability of the generated transcriptomic data.

Optimal Use Cases for PolyA Selection in Eukaryotic mRNA Profiling

Polyadenylated (polyA) selection remains a cornerstone technique in eukaryotic transcriptomics, offering a targeted approach for messenger RNA enrichment. This technical guide delineates the optimal use cases for polyA selection within the broader context of RNA sequencing methodologies, particularly in comparison to ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion. By examining the underlying mechanisms, experimental protocols, and analytical considerations, we provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for deploying this method effectively. The analysis reveals that polyA selection is uniquely advantageous for specific applications including quantitative gene expression studies, high-throughput drug screening, and any research context requiring cost-efficient mRNA profiling from high-quality RNA samples.

PolyA selection is a targeted enrichment strategy that leverages the polyadenylated tails present on most mature eukaryotic messenger RNAs (mRNAs). This method specifically captures these molecules using oligo(dT) probes, effectively isolating protein-coding transcripts from the total RNA pool which is dominated by ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and other non-coding RNA species [6]. In the landscape of bulk RNA-seq research, polyA selection and rRNA depletion represent two divergent philosophical approaches to transcriptome assessment: the former offers a focused view of the mature, protein-coding transcriptome, while the latter provides a broader surveillance of both coding and non-coding RNA species [2] [4]. Understanding the technical specifications, advantages, and limitations of polyA selection is fundamental to experimental success, particularly in drug development where resources must be allocated efficiently and conclusions drawn with precision [29].

The biological basis for polyA selection lies in the post-transcriptional modification process of polyadenylation, whereby a stretch of 200-250 adenine nucleotides is added to the 3' end of nascent mRNA molecules by poly(A) polymerase [6]. This poly(A) tail plays crucial roles in mRNA stability, nucleocytoplasmic export, and translation efficiency [30] [31]. From a technical perspective, polyA selection capitalizes on this universal feature of mature eukaryotic mRNAs through hybridization between the poly(A) tail and oligo(dT) probes immobilized on magnetic beads or other solid supports [6]. This binding mechanism forms the foundation of a highly specific enrichment process that effectively removes rRNA, transfer RNA (tRNA), and other non-polyadenylated RNAs, thereby concentrating the mRNA fraction for downstream sequencing applications [2].

PolyA Selection Mechanism and Standardized Protocols

Core Mechanism and Binding Chemistry

The polyA selection process operates through precise molecular interactions between the poly(A) tail of mature mRNAs and complementary oligo(dT) sequences immobilized on solid supports, typically magnetic beads [6]. This mechanism leverages the strong and specific base pairing between adenine (A) and thymine (T) nucleotides, which is further stabilized under high-salt binding conditions [6]. The selection process begins with RNA denaturation through brief heating to 65-70°C, which disrupts secondary structures and makes the poly(A) tail accessible for hybridization [6]. Subsequent incubation with oligo(dT) beads under appropriate buffer conditions allows for specific capture of polyadenylated RNAs, while non-polyadenylated species (including rRNA and tRNA) are removed through washing steps [6]. The final elution, typically using low-salt buffers or nuclease-free water at elevated temperatures (60-80°C), dissociates the A-T bonds and releases purified mRNA for downstream applications [6].

The following diagram illustrates the sequential workflow of the polyA selection protocol:

Standardized Experimental Protocol

The standardized protocol for polyA selection follows a consistent workflow across commercial systems, with minor variations in incubation times and buffer compositions [6]. The table below outlines the critical steps and key considerations for implementation:

Table 1: Standardized PolyA Selection Protocol and Optimization Considerations

| Step | Description | Key Parameters | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bead and RNA Preparation | Resuspend oligo(dT) magnetic beads; heat total RNA (65-70°C) in high-salt binding buffer | 100 ng-5 µg input RNA; heating time: 5-10 minutes | RNA quantity and quality critical; ratio of beads to RNA must be optimized |

| Annealing/Hybridization | Mix beads and denatured RNA; incubate for oligo(dT) binding | Room temperature incubation: 5-60 minutes; salt concentration optimization | Longer incubation may increase yield but extends processing time |

| Washing | Magnetic separation followed by 2-3 washes with high-salt buffer | 2-4 washes typically recommended | More washes increase purity but may decrease yield; balance based on application |

| Elution | Release mRNA using low-salt buffer or nuclease-free water at elevated temperature | Temperature: 60-80°C; time: ~2 minutes | Higher temperatures improve elution efficiency but risk RNA degradation |

| Optional On-Bead Workflow | Direct progression to cDNA synthesis without elution | Library preparation directly from beads | Reduces handling loss and processing time; becoming increasingly popular |

Variations in commercial implementations typically focus on bead-to-RNA ratios, with some protocols recommending fixed volumes (e.g., 2 µL beads per 5 µg RNA) while others suggest linear scaling with input amount [6]. Similarly, incubation conditions range from shorter periods (5-10 minutes) leveraging fast hybridization kinetics to longer incubations (60 minutes) aimed at maximizing yield from limited samples [6]. For junior scientists implementing this technique, critical success factors include: adjusting bead volumes when input RNA deviates significantly from standard 5 µg amounts; running pilot tests with varied incubation times to optimize yield; and monitoring RNA quality post-elution using appropriate quality control measures such as Bioanalyzer assessment [6].

Comparative Analysis: PolyA Selection vs. rRNA Depletion

When designing a transcriptomics study, the choice between polyA selection and rRNA depletion represents a fundamental decision point that dictates which RNA species will be captured and analyzed. Each method offers distinct advantages and limitations that must be weighed against experimental objectives [2].

Technical Performance and Coverage Characteristics

The two methods differ significantly in their technical performance and coverage characteristics across the transcriptome:

Table 2: Performance Comparison Between PolyA Selection and rRNA Depletion Methods

| Performance Metric | PolyA Selection | rRNA Depletion |

|---|---|---|

| Target RNA Species | Mature polyadenylated mRNA only [2] [6] | Both polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated RNAs [2] [4] |

| Exonic Coverage | High (concentrates reads on exons) [2] | Lower due to distribution across transcriptome |

| Intronic Coverage | Minimal [2] | Significant (retains pre-mRNA and nascent transcripts) [2] [31] |

| 3' Bias | Pronounced with degraded RNA [2] [6] | More uniform 5' to 3' coverage [2] |

| Sequencing Efficiency | High - fewer reads needed for gene-level coverage [2] [6] | Lower - requires deeper sequencing [2] |

| Detection of Long Genes | May underrepresent long transcripts [32] | Superior for long muscle genes (e.g., TTN, NEB, DMD) [32] |

| RNA Integrity Requirement | Requires high-quality RNA (RIN ≥7) [2] | Tolerant of degraded/FFPE RNA [2] |

The differential detection capabilities between methods extend to specific gene classes. rRNA depletion demonstrates superior performance in capturing long transcripts, particularly relevant in disease contexts such as muscular disorders where genes like titin (TTN), nebulin (NEB), and dystrophin (DMD) exceed 100 kb in length and are significantly under-represented in polyA-based approaches [32]. Additionally, rRNA depletion preserves non-polyadenylated transcripts including many long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), replication-dependent histone mRNAs, and nascent pre-mRNAs that are systematically excluded from polyA selection protocols [2] [31].

Decision Framework for Method Selection

The following decision diagram provides a structured approach for selecting between polyA selection and rRNA depletion based on key experimental parameters:

This decision framework highlights the scenarios where polyA selection is unequivocally preferred: when the research question focuses specifically on protein-coding genes, RNA integrity is high, and the experimental design prioritizes sequencing efficiency and cost-effectiveness [9] [2]. Conversely, rRNA depletion is indicated when working with degraded samples, studying non-polyadenylated RNAs, or requiring comprehensive transcriptome coverage including intronic regions [2] [32].

Optimal Application Scenarios for PolyA Selection

Gene Expression Quantification and Drug Discovery

PolyA selection excels in applications requiring precise quantification of gene expression levels, particularly in large-scale studies where cost efficiency and streamlined workflows are paramount [9]. The method's focus on mature mRNAs translates to exceptional exonic coverage and improved statistical power for differential expression analysis at equivalent sequencing depths [2]. In drug discovery pipelines, where hundreds or thousands of samples may be screened under various compound treatments, polyA selection offers significant practical advantages [29]. The method's compatibility with 3' mRNA-Seq approaches, such as QuantSeq, enables ultra-high-throughput expression profiling with minimal sequencing requirements (1-5 million reads per sample) and simplified data analysis through direct read counting without normalization for transcript length [9].

The efficiency of polyA selection in drug discovery extends to mode-of-action studies, where researchers need to identify expression patterns and pathway activation in response to therapeutic candidates [9] [29]. While whole transcriptome approaches may detect more differentially expressed genes due to their broader coverage, biological conclusions regarding affected pathways and processes remain highly consistent between methods [9]. This makes polyA selection particularly valuable for large-scale screening phases, where researchers can efficiently identify conditions of interest before proceeding to more targeted, in-depth investigations using comprehensive transcriptome methods on smaller sample subsets [9].

Specialized Research Contexts Favoring PolyA Selection

Beyond general expression profiling, several specialized research scenarios particularly benefit from polyA selection:

- Studies of cytoplasmic mRNA processing and translation: Since polyA selection specifically targets mature, cytoplasmic mRNAs, it is ideal for research focused on post-transcriptional regulation, translation efficiency, or mRNA stability [30] [6].

- Expression analysis in model organisms with well-annotated 3' UTRs: The effectiveness of polyA selection depends on accurate 3' transcript annotations [9]. In well-characterized systems like human and mouse, where 3' UTR annotations are comprehensive, polyA selection provides excellent quantification accuracy.

- Integration with single-cell RNA sequencing platforms: Most droplet-based single-cell RNA sequencing technologies rely on polyA selection for cell barcoding and mRNA capture, making bulk polyA-selected data highly comparable for integrative analyses [4].

- Viral transcriptomics in eukaryotic systems: Many viruses utilize host polyadenylation machinery, making polyA selection suitable for studying viral gene expression in infected cells [2].

Practical Implementation and Research Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of polyA selection requires specific reagents and materials optimized for the capture process:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for PolyA Selection

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Technical Specifications | Optimization Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads | Capture polyadenylated RNA through hybridization | Bead size: 1-2 µm; oligo(dT) length: 15-25 nt; binding capacity: ~5 µg mRNA/µL beads | Scale bead volume according to input RNA; avoid using expired beads |

| High-Salt Binding Buffer | Stabilize A-T base pairing during hybridization | Typically contains 1M LiCl or similar salt; may include Tris-EDTA and detergent | Maintain precise salt concentration; prepare fresh batches periodically |

| RNA Denaturation Solution | Disrupt RNA secondary structures | May contain dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or formamide; often combined with heating | Limit denaturation time to prevent RNA degradation |

| Low-Salt Elution Buffer | Dissociate mRNA from beads after washing | Nuclease-free water or 1mM EDTA; typically preheated to 60-80°C | Optimize temperature balance: higher temperature improves yield but risks degradation |

| RNase Inhibitors | Prevent RNA degradation during processing | Protein-based or chemical inhibitors; included in commercial kits | Essential for processing low-input samples; add to all solutions |

Quality Control and Troubleshooting

Robust quality control measures are essential throughout the polyA selection process. Input RNA should demonstrate high integrity (RNA Integrity Number ≥7 or DV200 ≥50%) for optimal results [2]. Post-selection assessment should include evaluation of yield, purity (via 260/280 and 260/230 ratios), and size distribution using appropriate methods such as Bioanalyzer or TapeStation electrophoretograms [33]. Common challenges include low yield (often addressed by optimizing bead-to-input ratios and hybridization times), rRNA contamination (indicative of insufficient washing or degraded starting material), and 3' bias (a hallmark of RNA degradation) [2] [6]. For large-scale studies, implementing spike-in controls (such as SIRVs) provides an internal standard for assessing technical performance, normalization, and data quality [29].

PolyA selection remains an indispensable tool in the transcriptomics arsenal, particularly suited for research focused on protein-coding gene expression in eukaryotic systems. Its optimal use cases include quantitative gene expression studies, high-throughput drug screening, and any application where cost-effective mRNA profiling from high-quality RNA samples is desired. While rRNA depletion offers broader transcriptome coverage and greater tolerance for degraded samples, polyA selection provides unmatched efficiency and precision for its intended applications. As transcriptomic technologies continue to evolve, understanding these methodological distinctions enables researchers to align experimental design with biological questions, ensuring scientifically sound and resource-efficient outcomes in both basic research and drug development contexts.

In the realm of bulk RNA-seq research, the critical choice between poly(A) selection and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion defines the transcriptome you measure. While poly(A) selection has been a longstanding method for enriching mature messenger RNAs, ribosomal depletion has emerged as the indispensable technique for a wide array of challenging yet scientifically crucial scenarios. This guide details the specific experimental conditions—degraded RNA samples, Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tissues, and studies targeting non-polyadenylated transcripts—where rRNA depletion is not merely an alternative, but a necessity for comprehensive and accurate transcriptome profiling.

Mechanisms of Ribosomal Depletion

Ribosomal depletion strategies work by selectively removing abundant rRNA molecules, which can constitute 80-90% of total RNA, thereby allowing sequencing resources to be focused on informative transcripts [34] [35]. Two primary methodological approaches achieve this:

- Bead-Based Capture Methods: These methods, utilized by kits such as Illumina's Ribo-Zero and Lexogen's RiboCop, employ biotinylated DNA oligonucleotides that are complementary to rRNA sequences [36]. These probes hybridize to the rRNA, and the resulting RNA-DNA hybrids are subsequently captured and removed using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads [34].

- RNase H-Mediated Degradation: This approach, used in kits like NEBNext rRNA Depletion and Kapa RiboErase, involves hybridizing single-stranded DNA probes to rRNA [36]. The enzyme RNase H is then used to specifically degrade the RNA strand of the resulting DNA-RNA hybrids, effectively depleting the rRNA from the sample [34].

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision pathway for selecting the appropriate rRNA depletion method based on experimental parameters:

Key Applications for Ribosomal Depletion

Degraded RNA and FFPE Samples