RNA-seq Alignment Tools Compared: A Practical Guide to STAR, HISAT2, and TopHat2 for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical step of read alignment in RNA-seq analysis.

RNA-seq Alignment Tools Compared: A Practical Guide to STAR, HISAT2, and TopHat2 for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical step of read alignment in RNA-seq analysis. It explores the foundational principles, practical application, and comparative performance of the three predominant aligners: STAR, HISAT2, and TopHat2. Drawing on recent benchmarking studies and community expertise, we deliver actionable methodologies, common troubleshooting solutions, and data-driven recommendations to help scientists optimize their transcriptomic pipelines for more accurate and reliable differential expression analysis, ultimately supporting robust biomarker discovery and clinical research.

The Bedrock of RNA-seq: Understanding Splice-Aware Alignment and Key Aligner Algorithms

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has established itself as a foundational technique in modern genomics, providing unprecedented detail about the transcriptional landscape of cells [1]. However, the journey from raw sequencing data to biological insight hinges on a critical computational step: alignment. The process of determining the genomic origin of sequenced RNA fragments is fundamentally different from and more complex than aligning DNA sequences. This complexity arises from a single, key biological reality—the presence of introns. Pre-messenger RNA transcripts undergo splicing, a process where introns are removed and exons are joined together to form a continuous template for protein synthesis [2]. Consequently, an RNA-seq read derived from a spliced mRNA may span multiple, non-contiguous genomic regions (exons) that can be separated by introns thousands of bases long. This creates the central challenge for RNA-seq alignment: the aligner must perform spliced alignment, detecting where a single read aligns to multiple exon segments in the genome, often without prior knowledge of splice site locations [2] [1].

Recognizing and accurately aligning across these splice junctions is not merely a technical detail; it is paramount for the correct interpretation of transcriptomic data. Failure to account for splicing can lead to misalignment, which in turn generates inaccurate gene expression quantifications, obscures alternative splicing events, and hinders the discovery of novel transcripts and isoforms [2] [3]. This application note delves into the unique demands of RNA-seq alignment, evaluates the performance of key splice-aware aligners within the context of ongoing genomics research, and provides detailed protocols to guide researchers and drug development professionals in obtaining biologically meaningful results.

Algorithmic Foundations of Splice-Aware Aligners

Core Data Structures for Spliced Alignment

Splice-aware aligners rely on sophisticated data structures to index the reference genome efficiently, enabling them to quickly locate potential alignment positions for a read, even when it is split across exons. The choice of data structure significantly impacts an aligner's runtime, memory usage, and sensitivity [4].

The FM-index (Full-text index in Minute space), which incorporates the Burrows-Wheeler Transform (BWT), is used by several modern aligners like HISAT2 and Bowtie2 [4]. This structure is highly memory-efficient, as the BWT allows for compression of the reference genome. The process involves creating an array of all possible suffix rotations of the genome, sorting them lexicographically, and storing the last column as the BWT. This creates runs of identical characters that can be compressed, reducing the memory footprint—a crucial advantage for large genomes like human [4].

In contrast, aligners like STAR utilize an uncompressed suffix array [4]. This structure lists all suffixes of the reference genome in alphabetical order, along with their starting positions. This allows for rapid exact matching of sequences. While suffix arrays generally offer faster lookup times than FM-indices, they come at the cost of significantly higher memory usage, which can be a limiting factor on some computer systems [4].

Table 1: Key Data Structures Used in Splice-Aware Aligners

| Data Structure | Underlying Algorithm | Representative Aligner(s) | Memory Usage | Lookup Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FM-Index | Burrows-Wheeler Transform (BWT) | HISAT2, Bowtie2 | Low | Fast |

| Suffix Array | Sorted array of genome suffixes | STAR | High | Very Fast |

| Hash Table | Pre-computed k-mer indexes | TopHat2 | Medium | Medium |

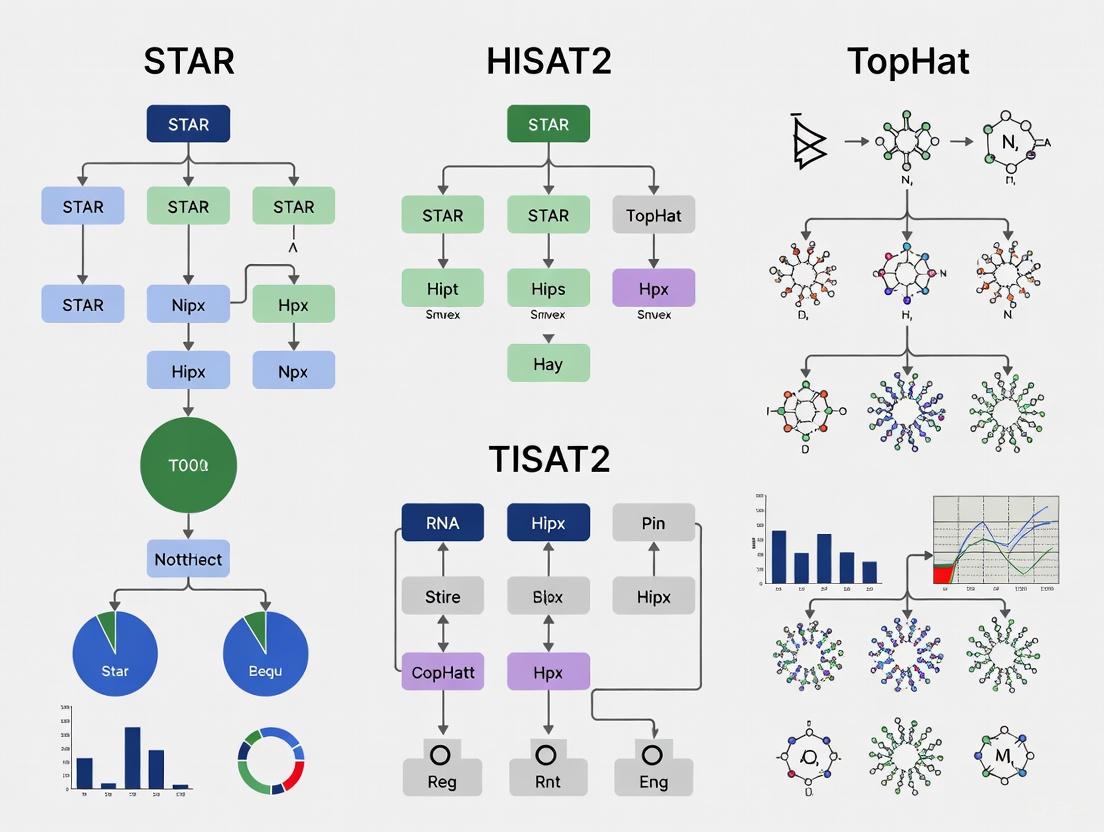

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow an aligner follows to resolve a spliced alignment, regardless of the specific data structure used.

Evolution of Aligner Performance and Methodology

The development of RNA-seq aligners has seen significant evolution, moving from early algorithms like TopHat2 to more efficient and accurate tools such as HISAT2 and STAR. Benchmarking studies have consistently highlighted this progression. A comprehensive comparison of aligners using RNA-seq data from the grapevine powdery mildew fungus found that all tested aligners performed well in terms of alignment rate and gene coverage with the exception of TopHat2, which HISAT2 superseded [4]. This sentiment is echoed in community forums, where a strong consensus advises against using TopHat, with one biostar post succinctly stating, "Spoiler: Dont use tophat!" [5].

The performance disparities between aligners are rooted in their algorithmic approaches. Tools like STAR, which uses a suffix array, excel in speed but require substantial memory (typically over 28 GB for the human genome) [5] [4]. In contrast, HISAT2 employs a hierarchical FM-index that allows for efficient and accurate alignment with significantly lower memory requirements, making it accessible for a wider range of computing environments [4] [1]. Another key consideration is robustness across different parameters; while most aligners can be configured for good performance, some, like STAR, maintain strong performance even with default settings, simplifying their use for non-bioinformaticsians [5].

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Common RNA-seq Aligners

| Aligner | Algorithm Type | Splice Junction Discovery | Typical Runtime | Memory Requirements | Key Differentiator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TopHat2 | Segmented read mapping | Reference annotation & de novo | Slow | Medium | Largely obsolete; superseded by newer tools [5] [4] |

| HISAT2 | Hierarchical FM-Index | Reference annotation & de novo | Fast | Low | Efficient memory use; good all-arounder [4] [6] [1] |

| STAR | Suffix Array | Primarily de novo | Very Fast | High (e.g., ~28GB human) | High accuracy, fast execution [5] [4] [1] |

| BBMap | Not Specified | Not Specified | Medium | Medium | High accuracy; fast indexing [5] |

Experimental Protocols for RNA-seq Alignment

Standard Workflow for Short-Read Alignment with HISAT2

The following protocol describes a robust workflow for aligning short-read RNA-seq data using HISAT2, which balances accuracy, speed, and computational efficiency [6] [1]. This protocol assumes quality control (QC) and read trimming have already been performed using tools like FastQC and Trimmomatic or fastp [7].

Step 1: Genome Index Preparation

- Download the reference genome sequence (e.g., in FASTA format) and the corresponding annotation file (GTF format) for your organism.

- Construct the HISAT2 index. This is a one-time step for a given genome and annotation.

- Use the command:

- For a more comprehensive index that includes known splice sites, first extract splice site and exon information: Then build the index with:

Step 2: Read Alignment

- Run the alignment process. The typical command is:

- Key parameters to consider:

--rna-strandness RF: Specify for strand-specific libraries (e.g., Illumina TruSeq).--min-intronlen 20and--max-intronlen 500000: Adjust intron size boundaries appropriate for your organism.--dta: Use this option if the output is intended for transcript assemblers like StringTie, as it reports alignments tailored for downstream assembly.

Step 3: Post-Alignment Processing

- Convert the SAM (Sequence Alignment Map) output to its binary, compressed BAM format, and sort the alignments by genomic coordinate.

- Index the sorted BAM file to allow for rapid visualization and access.

Specialized Protocol for Long-Read Alignment with uLTRA

The emergence of long-read sequencing technologies (PacBio and Oxford Nanopore) for RNA-seq presents new challenges, primarily due to higher error rates and the need to span complex, full-length transcripts [2] [3]. uLTRA is a specialized aligner designed to address these challenges, particularly improving accuracy for small exons [2].

Step 1: Indexing the Reference Genome and Annotation

- uLTRA requires a pre-built index of the genome and annotation. This step uses a custom indexing strategy that partitions the genome into parts, flanks, and segments based on the provided annotation.

- Run the indexing command:

Step 2: Aligning Long Reads

- Align reads in FASTA or FASTQ format using the pre-built index.

- The basic alignment command is:

- uLTRA employs a novel two-pass collinear chaining algorithm. In the first pass, it uses Maximal Exact Matches (MEMs) to identify candidate gene regions. In the second pass, it uses a dynamic programming formulation to chain together genomic segments, allowing for accurate alignment across small exons that other long-read aligners often miss [2].

Step 3: Integration with Minimap2 for Comprehensive Coverage

- To also detect novel transcripts in unannotated genomic regions, uLTRA can be run as a wrapper around minimap2.

- In this mode, uLTRA will select the best alignment for each read between its own result and the primary alignment from minimap2, providing comprehensive coverage of both annotated and novel regions [2].

The overall workflow for a complete RNA-seq analysis, from raw data to differential expression, integrating both short- and long-read approaches, is summarized below.

Successful RNA-seq alignment requires a combination of software tools, reference data, and computational resources. The following table details key components of the research toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq Alignment

| Tool/Resource | Category | Primary Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| HISAT2 | Alignment Software | Spliced alignment of short RNA-seq reads | Recommended for standard experiments due to low memory footprint and high accuracy [4] [6]. |

| STAR | Alignment Software | Spliced alignment of short RNA-seq reads | Ideal when computational resources are ample; offers very fast execution [5] [1]. |

| uLTRA | Alignment Software | Spliced alignment of long RNA-seq reads | Specialized for accurate alignment of small exons in PacBio/ONT data [2]. |

| FastQC | Quality Control | Visual assessment of raw read quality | Used pre-alignment to identify adapter contamination and quality drops [1]. |

| fastp | Preprocessing | Trimming adapters and low-quality bases | Improves subsequent alignment rates and accuracy [7]. |

| SAMtools | File Manipulation | Processing and indexing alignment files | Essential for converting, sorting, and indexing SAM/BAM files [1]. |

| Reference Genome (FASTA) | Reference Data | Genomic sequence for mapping | Must be of high quality and from a reputable source (e.g., ENSEMBL, UCSC). |

| Annotation File (GTF/GFF) | Reference Data | Genomic coordinates of known genes | Guides aligners to known splice junctions and exon structures [1]. |

The critical need for splice awareness in RNA-seq alignment is an incontrovertible requirement for accurate transcriptome analysis. As this document has detailed, the ability of an aligner to correctly resolve the location of reads spanning splice junctions directly impacts all downstream biological interpretations, from differential gene expression to novel isoform discovery. The field has matured significantly, with modern tools like HISAT2 and STAR offering robust solutions for short-read data, and specialized algorithms like uLTRA emerging to tackle the unique challenges of long-read sequencing [4] [2].

Future developments in transcriptome informatics will continue to be driven by advancements in sequencing technologies and algorithmic innovation. The recent comprehensive assessment by the LRGASP consortium highlights key trends, including that longer, more accurate reads produce more precise transcript models and that increased read depth improves quantification accuracy [3]. For researchers in both academia and drug development, the path forward involves carefully selecting alignment tools based on the specific experimental question, the organism being studied, and the available computational resources. As the integration of orthogonal data and the use of replicate samples becomes standard practice, the reliability of detecting rare and novel transcripts will only increase, further solidifying RNA-seq as an indispensable tool for unlocking the complexities of the transcriptome and advancing therapeutic discovery.

The alignment of sequencing reads to a reference genome is a foundational step in the majority of genomic and transcriptomic analyses [4]. The sheer volume of data produced by modern high-throughput sequencing technologies makes the brute-force comparison of each read to every position in a reference genome computationally impractical [8] [9]. To overcome this challenge, alignment algorithms rely on sophisticated indexing strategies to rapidly narrow the search space, determining the potential genomic origin of millions of reads in a feasible time. The development of these algorithms is intrinsically linked to advances in sequencing technology, with new data characteristics driving algorithmic innovation [8]. Two pivotal data structures have shaped modern aligners: the FM-Index and the Suffix Array. These structures form the computational core of widely used RNA-seq alignment tools such as STAR, HISAT2, and the now largely superseded TopHat2 [4] [10]. Understanding their underlying mechanics is crucial for researchers to select the appropriate tool and interpret its results accurately.

Core Algorithmic Foundations

The FM-Index and Burrows-Wheeler Transform

The FM-Index (Full-text index in Minute space) is a compressed, yet searchable, suffix array-like structure that has become a cornerstone of many modern aligners due to its favorable balance of speed and memory efficiency [4] [11]. Its most critical component is the Burrows-Wheeler Transform (BWT), which is designed to create runs of identical characters in a sequence, thereby making the data more compressible [4].

The process of creating an FM-index involves several steps. First, all possible cyclic rotations of the reference genome string are generated. These rotations are then sorted lexicographically. The BWT itself is the last column of this sorted matrix. To enable efficient searching, the algorithm also constructs a rank table that records the number of times each character appears up to any given position in the BWT, and a lookup table that stores the first occurrence of each character in the sorted list of rotations [4].

Aligners such as HISAT2 and Bowtie2 utilize the FM-index for its low memory footprint. For example, HISAT2 employs a hierarchical indexing strategy that uses a global FM-index to anchor alignments rapidly, supplemented by tens of thousands of small local FM-indexes (~48,000 for the human genome) to resolve ambiguous or spliced alignments efficiently. This design allows HISAT2 to align RNA-seq reads, including those spanning splice junctions, while requiring only about 4.3 gigabytes of memory for the human genome [10].

The Suffix Array

A suffix array is a simpler, uncompressed data structure that serves as a space-efficient alternative to the suffix tree, an earlier indexing method [4]. To construct a suffix array for a reference genome, all possible suffixes of the sequence are first generated. The starting positions of these suffixes are then recorded, and the list of suffixes is sorted alphabetically. This final, sorted list of starting indices is the suffix array [4].

The key advantage of suffix arrays lies in their fast lookup time for exact matches. Because the suffixes are sorted, all sequences sharing a common prefix are adjacent in the array. This allows an algorithm to quickly locate the genomic position of any read by performing a binary search over the suffix array. However, a significant disadvantage is their memory requirement, which can be substantial for large genomes [4].

The aligner STAR is a prominent example that uses suffix arrays. Its algorithm involves searching for Maximal Mappable Prefixes (MMPs)—the longest subsequences of a read that exactly match one or more locations in the reference genome. By finding these MMPs, STAR can quickly identify candidate genomic locations, even for reads that cross splice junctions. This method is highly accurate but demanding on resources, requiring approximately 28 GB of RAM for the human genome [8] [10].

Table 1: Comparison of Core Indexing Algorithms in Read Alignment

| Feature | FM-Index | Suffix Array |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Principle | Burrows-Wheeler Transform (BWT) of the reference genome [4] | Sorted array of all suffixes of the reference genome [4] |

| Memory Footprint | Low (e.g., ~4.3 GB for HISAT2 on human genome) [10] | High (e.g., ~28 GB for STAR on human genome) [10] |

| Primary Strength | Excellent balance of speed and memory efficiency; high compressibility [4] [11] | Very fast lookup time for exact matches and long sequences [4] [8] |

| Common Aligners | HISAT2, Bowtie2, BWA [4] [11] | STAR, MUMmer4 [4] [8] |

| Typical Use Case | Fast alignment on standard workstations; large-scale batch processing [10] | Rapid alignment on high-memory servers; handling long reads and complex splicing [8] |

Algorithm Implementation in RNA-Seq Aligners

HISAT2: Hierarchical FM-Indexing for Spliced Alignment

HISAT2 leverages a sophisticated hierarchical indexing strategy built upon the FM-index to address the specific challenge of aligning RNA-seq reads across splice junctions. Its index is composed of two layers: a global FM-index representing the entire genome, and approximately 48,000 local FM-indexes, each covering a genomic region of about 64,000 base pairs [10]. This architecture is exceptionally efficient, requiring only 4.3 GB of memory for the human genome.

The alignment logic for handling spliced reads is systematic. The algorithm first attempts to find full-length, un-spliced alignments. For reads that do not align fully, HISAT2 searches for alignments that span known or novel splice sites. It categorizes exon-spanning reads based on the length of the "anchor" sequence on each exon. Reads with long anchors (e.g., >16 bp on both exons) can often be mapped directly using the global index. The power of the local indexes becomes apparent with reads that have intermediate-length anchors (8-15 bp); since a local index covers a small genomic region, a short sequence that would be ambiguous genome-wide can often be placed uniquely within a local index [10]. HISAT2's default mode uses a hybrid, quasi-single-pass approach that incorporates splice sites discovered from earlier reads when aligning subsequent reads, achieving high sensitivity without the runtime cost of a full two-pass analysis [10].

STAR: Suffix Array-Based Mapping for Complex Transcriptomes

STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) employs an algorithm centered on suffix arrays to achieve high accuracy and speed, particularly for longer reads. Its core operation involves searching for Maximal Mappable Prefixes (MMPs), which are the longest subsequences from the start of a read that exactly match the reference genome [8].

The STAR protocol follows a structured workflow. In the first step, the reference genome is processed to construct a suffix array index, which is memory-intensive but enables extremely fast exact matching. For each read, STAR performs a sequential search for MMPs. If the entire read is mapped as a single MMP, it is reported as an un-spliced alignment. If not, the algorithm allows the MMP to be shortened, creating a "seed" alignment, and the process repeats for the remaining portion of the read. This method naturally enables the detection of splice junctions, as the gaps between non-overlapping MMPs within a single read are inferred to be introns [8]. STAR also offers a two-pass mode (STARx2), where splice junctions discovered in a first pass over all samples are used to inform a second, more sensitive alignment round. While this increases sensitivity, it also more than doubles the runtime [10].

Figure 1: The STAR alignment algorithm workflow based on Maximal Mappable Prefixes (MMPs) and suffix arrays.

Comparative Experimental Performance

Empirical evaluations of these aligners reveal distinct performance profiles, allowing researchers to make informed choices based on their specific experimental needs and computational constraints.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of RNA-Seq Aligners [4] [6] [10]

| Aligner | Core Algorithm | Reported Speed (Reads/Second) | Memory Usage (Human Genome) | Alignment Sensitivity (Simulated Data) | Key Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HISAT2 | Hierarchical FM-Index | ~110,000 | ~4.3 GB | High (Default mode) [10] | Ideal for standard workstations; general RNA-seq profiling [6] [10] |

| STAR | Suffix Array | ~81,000 | ~28 GB | High [10] | Best for servers; rapid processing of large datasets; complex splicing analysis [8] [6] |

| TopHat2 | FM-Index (via Bowtie) | ~2,000 | Moderate | Lower than modern aligners [4] [10] | Largely superseded by HISAT2; included for historical context [4] [12] |

To implement the protocols and analyses described, researchers require access to specific computational resources and software tools. The following table details these essential components.

Table 3: Essential Computational Resources for RNA-Seq Alignment Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome | A curated, high-quality genome sequence for the target species. Serves as the map for aligning reads. | Used by all aligners (HISAT2, STAR, etc.). Files in FASTA format (e.g., GRCh38 for human) [13] [6]. |

| Genome Annotation File | Provides genomic coordinates of known genes, transcripts, and splice sites (GTF/GFF format). | Improves accuracy of spliced alignment. HISAT2 and STAR can use these known splice sites to guide alignment [13] [10]. |

| High-Performance Computing | Adequate CPU (cores) and RAM (memory) to run alignment tools efficiently. | HISAT2 can run on a desktop with 16GB RAM. STAR typically requires a server with >32GB RAM for the human genome [5] [10]. |

| Quality Control Tools | Assess the quality of raw sequencing data (FASTQ files) before alignment. | Tools like FastQC or Falco check for per-base sequence quality, adapter contamination, and GC content [13] [14]. |

| Sequence Trimming Tools | Remove low-quality bases and adapter sequences from reads to improve alignment rates. | Trimmomatic or Cutadapt are used pre-alignment to clean the data [13] [14]. |

Detailed Protocol for a Benchmarking Experiment

To objectively evaluate the performance of different alignment algorithms, the following protocol outlines a systematic benchmarking experiment using simulated RNA-seq data.

Experimental Aims and Objective Evaluation Metrics

Primary Aim: To quantitatively compare the accuracy, computational efficiency, and splice junction detection performance of FM-index-based (HISAT2) and suffix-array-based (STAR) aligners under controlled conditions.

Key Evaluation Metrics:

- Alignment Sensitivity: The proportion of simulated reads correctly aligned to their true genomic origin, including exact splice junction boundaries [10].

- Splice Site Precision & Recall: Precision is the fraction of correctly predicted splice sites among all predictions. Recall (sensitivity) is the fraction of true splice sites that were successfully detected [10].

- Computational Efficiency: Total runtime and peak memory usage, measured on a standardized computing node [4] [10].

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Data Simulation

- Use an RNA-seq read simulator (e.g., based on the Flux Simulator) to generate a dataset of ~20 million paired-end reads (e.g., 100 bp length) from a reference transcriptome (e.g., human GRCh38) [10].

- Introduce a realistic sequencing error profile (e.g., 0.5% mismatch rate).

- Critical Parameter: Ensure the simulation model includes a distribution of fragment lengths and expresses transcripts at varying levels to mimic a real experiment.

Step 2: Aligner Execution

- Run each aligner (HISAT2, STAR) on the identical simulated dataset.

- For HISAT2: Use the default parameters for a balance of speed and sensitivity. Optionally, run a second iteration where you provide a GTF file of known annotations (

--known-splicesite-infile). - For STAR: Run the standard one-pass mode. Subsequently, run the two-pass mode (

--twopassMode Basic) which can increase splice junction discovery. - Control: Include an older aligner like TopHat2 for baseline performance comparison.

Step 3: Data Collection and Analysis

- For each run, record the wall-clock time and maximum memory usage.

- Extract the alignment results in SAM/BAM format.

- Using the ground truth from the simulation, calculate alignment sensitivity and splice site precision/recall for each tool. This can be done with custom scripts or tools like

rseqc. - Compile the results into a comparative table (see Table 2 for an example structure).

Figure 2: A high-level workflow for a computational benchmarking experiment comparing RNA-seq aligners.

The Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference (STAR) aligner employs a unique sequential seed alignment strategy that fundamentally differs from other FM-index-based aligners, enabling unprecedented sensitivity in detecting splice junctions and complex RNA-seq mappings. At the core of STAR's design is a two-step process that first identifies maximal mappable prefixes (MMPs) through suffix array indexing, followed by a clustering/stitching/scoring step that reconstructs full read alignments [15]. This approach allows STAR to detect splice junctions de novo without relying on pre-existing junction databases, giving it a significant advantage when working with poorly annotated genomes or novel splicing events [15].

Unlike HISAT2, which uses a Hierarchical Graph FM index (HGFM) to generate multiple local small indices, STAR's algorithm systematically maps each seed according to its MMP, allowing it to discover splice junction locations within each read sequence a priori [15]. STAR's suffix array implementation obviates the need for the Burrows-Wheeler transform (BWT) and FM-index structures used by most modern aligners, including HISAT2 and Bowtie2 [4] [15]. This architectural difference enables STAR to achieve superior performance in alignment accuracy, particularly for longer transcripts and at junction boundaries, though at the cost of higher computational resources compared to HISAT2 [4] [16].

Sequential Seed Alignment: Core Algorithmic Principles

Maximal Mappable Prefix (MMP) Discovery

STAR's sequential seed alignment begins with the identification of Maximal Mappable Prefixes (MMPs) - the longest subsequences from the start of a read that exactly match one or more locations in the reference genome. The algorithm initiates mapping from the first base of each read and extends sequentially until it encounters a mismatching base or reaches the end of the read [15]. For each read, this process generates multiple MMPs of varying lengths, which serve as the fundamental "seeds" for subsequent alignment steps. This sequential approach contrasts with fixed-length k-mer strategies used by other aligners, allowing STAR to dynamically adapt to local sequence complexity and variation.

The MMP search leverages suffix arrays as the core data structure for rapid sequence lookup. Suffix arrays provide an efficient means of finding exact matches by storing all suffixes of the reference genome in sorted order, enabling binary search operations with O(log n) time complexity [4]. When STAR encounters a position where the current MMP cannot be extended further, it terminates that MMP and begins a new MMP starting at the next unmapped position in the read. This process continues until the entire read is processed into a set of non-overlapping MMPs that collectively cover the complete read sequence.

Clustering, Stitching, and Scoring

Following MMP identification, STAR enters the clustering and stitching phase where discontinuous MMPs are assembled into complete alignments. MMPs that map to nearby genomic positions are grouped into clusters, with the algorithm evaluating possible arrangements that respect biological constraints such as splice junction motifs and gap sizes [15]. During stitching, MMPs separated by intronic gaps are connected through splice-aware alignment that accounts for canonical GT-AG splice signals and other biological splicing patterns.

The scoring system evaluates potential alignments based on multiple criteria, including the number and length of matching bases, gap penalties, splice junction quality, and mismatch tolerance. Alignment scoring assigns weights to longer anchors and considers anchor distance, prioritizing alignments with strong supporting evidence [17]. This comprehensive evaluation allows STAR to accurately resolve complex mapping scenarios involving alternative splicing, sequencing errors, and genetic variations while maintaining high sensitivity for both constitutive and alternative splicing events.

Performance Comparison with HISAT2 and TopHat2

Table 1: Comparative Performance of RNA-seq Aligners Across Key Metrics

| Aligner | Alignment Algorithm | Indexing Strategy | Splice Junction Sensitivity | Memory Usage | Speed | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAR | Sequential seed alignment with MMPs | Suffix array | Highest (90%+ base-level accuracy) [15] | High (∼30GB human genome) [16] | Fast (400M reads/hour) [16] | Novel junction discovery, long transcripts [4] |

| HISAT2 | Hierarchical Graph FM-index | HGFM (local indices) | Medium (improved over TopHat2) [15] | Moderate | ∼3x faster than STAR [4] | Standard differential expression, limited resources |

| TopHat2 | Traditional FM-index | BWT/FM-index | Lower (superseded by HISAT2) [4] | Moderate | Slowest | Legacy compatibility only |

Table 2: Alignment Performance on Different Transcript Lengths

| Aligner | Short Transcripts (<500 bp) | Long Transcripts (>500 bp) | Junction Base-Level Accuracy | Overall Alignment Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAR | Good | Excellent [4] | 80%+ [15] | >90% unique mapping [16] |

| HISAT2 | Good | Good [4] | Moderate | High |

| BWA | Excellent | Moderate [4] | N/A | Highest (except long transcripts) [4] |

STAR demonstrates particular strength in junction base-level resolution, where it achieves over 80% accuracy in detecting splice junction boundaries according to benchmarking studies using Arabidopsis thaliana data [15]. In base-level assessments, STAR outperforms other aligners with overall accuracy exceeding 90% under various testing conditions [15]. The aligner shows remarkable consistency across different levels of sequence polymorphism introduction, maintaining robust performance even with significant SNP densities [15].

When considering computational efficiency, HISAT2 operates approximately 3-fold faster than STAR and requires less memory, making it suitable for researchers with limited computational resources [4]. However, users report that STAR achieves significantly higher mapping rates (>90% unique mapping) compared to other aligners, which sometimes report mapping rates as low as 50% on complex or draft genomes [16]. This performance advantage is particularly evident when working with highly fragmented genomes or those containing ambiguity symbols, where STAR's suffix array approach demonstrates superior robustness [16].

Experimental Protocol for STAR Alignment

Genome Indexing

The first critical step in STAR alignment is genome indexing, which creates the suffix array data structure necessary for rapid sequence lookup. The indexing process requires two input files: a reference genome in FASTA format and gene annotation in GTF or GFF format. The basic command structure is:

Key parameters include --sjdbOverhang, which specifies the length of genomic sequence around annotated junctions and should be set to read length minus 1, and --runThreadN, which determines the number of parallel threads to utilize during indexing. For a typical mammalian genome, the indexing process requires approximately 30GB of RAM and generates index files occupying roughly 30-40GB of disk space [16].

Read Alignment

Once the genome index is prepared, read alignment can be performed using the following protocol:

This command executes the sequential seed alignment process, generating several output files including sorted BAM alignment files, splice junction tables, and gene count matrices. The --outFilterMultimapNmax parameter controls how many multimapping locations are reported for reads that align to multiple positions, while the --alignIntronMin and --alignIntronMax parameters define realistic intron size boundaries that help filter biologically implausible alignments [18] [19].

Post-Alignment Processing

Following STAR alignment, several quality control and processing steps are essential for downstream analysis:

These post-processing steps validate alignment quality and prepare data for differential expression analysis. The SJ.out.tab file contains detailed information about detected splice junctions, including genomic coordinates, strand information, and read counts supporting each junction [19].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for STAR Alignment

| Resource Type | Specific Tool/Resource | Function in Protocol | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome | NCBI RefSeq, Ensembl, UCSC Genome Browser | Provides genomic coordinate system for alignment | Species-specific, version-controlled, with annotation |

| Annotation File | GTF/GFF format from GENCODE, Ensembl | Defines gene models for junction awareness | Comprehensive splice isoform information |

| Quality Control | FastQC, MultiQC | Pre-alignment read quality assessment | Identifies adapter contamination, base quality issues [20] |

| Trimming Tool | Trimmomatic, BBDuk | Removes adapter sequences and low-quality bases | Quality and adapter trimming [18] |

| Sequence Alignment | STAR | Splice-aware read alignment | Sequential seed alignment, junction discovery [15] |

| Alignment Processing | SAMtools, Picard | BAM file manipulation and metrics | Sorting, indexing, duplicate marking [21] |

| Quantification | featureCounts, HTSeq | Generate gene-level count matrix | Read counting per gene [6] |

Successful implementation of STAR alignment requires appropriate computational infrastructure. For mammalian genomes, we recommend a minimum of 32GB RAM and multiple CPU cores, with storage capacity sufficient for large reference indices (∼30GB) and temporary files generated during alignment [16]. The nf-core RNA-seq workflow provides a standardized pipeline that incorporates STAR alignment alongside quality control and quantification steps, ensuring reproducibility and best practices implementation [19].

When preparing samples for sequencing, we strongly recommend paired-end library preparation with read lengths of at least 75bp to maximize junction detection sensitivity. The additional information from paired-end reads significantly improves mapping accuracy, particularly for distinguishing between paralogous genes and resolving complex splicing patterns [19]. For strand-specific libraries, proper configuration of the --outSAMstrandField parameter is essential for maintaining strand information throughout the alignment process.

Applications in Drug Development and Biomedical Research

STAR's high sensitivity alignment strategy offers particular value in pharmaceutical research and biomarker discovery, where comprehensive transcriptome characterization is essential. In cancer research, STAR's ability to detect novel splice variants and fusion transcripts enables identification of neoantigens and therapeutic targets that might be missed by less sensitive aligners [21]. The aligner's robust performance with degraded samples, such as formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, makes it particularly valuable for clinical trial analyses utilizing archival specimens [18].

In infectious disease applications, STAR's sequential seed alignment provides advantages for studying host-pathogen interactions through dual RNA-seq experiments. The algorithm's sensitivity to low-abundance transcripts and ability to characterize viral splicing events supports comprehensive investigation of infection mechanisms and host response pathways [4]. For vaccine development, STAR's accurate quantification of immune-related genes and their isoforms facilitates precise characterization of vaccine-induced transcriptional changes [17].

The implementation of STAR within standardized workflows like nf-core/rnaseq ensures reproducible analysis across multi-center clinical trials and collaborative drug development programs [19]. This reproducibility is essential for regulatory compliance and validation of biomarker signatures in precision medicine applications. As RNA-seq technologies continue to evolve toward longer reads and single-cell applications, STAR's fundamental alignment strategy provides a robust foundation for adapting to these emerging methodologies in pharmaceutical research.

The standard protocol for RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) analysis involves aligning short sequencing reads to a reference genome to determine their origin and abundance. For years, the predominant approach has relied on a single, linear reference genome, which represents only a small number of individuals and lacks population diversity [22]. This reliance introduces significant biases, as sequences from individuals not represented in the reference may align incorrectly or fail to align altogether, particularly in highly polymorphic regions [22] [4]. This limitation can adversely affect downstream analyses, such as variant calling and gene expression quantification, by reducing sensitivity and accuracy. The fundamental challenge has been to develop an alignment method that efficiently incorporates known genetic variation without becoming computationally prohibitive. HISAT2 addresses this challenge through a novel indexing scheme that uses a graph-based representation of a population of genomes, enabling more accurate alignment while maintaining speed and manageable memory requirements [22] [23].

Algorithmic Foundation: The Hierarchical Graph FM Index (HGFM)

Core Concept: From Linear Sequence to Genome Graph

HISAT2 fundamentally enhances the Burrows-Wheeler Transform (BWT) and Ferragina-Manzini (FM) index, which are the core technologies behind many modern aligners like Bowtie and BWA [22] [4] [9]. While these conventional methods index a single, linear reference sequence, HISAT2 creates a linear graph of the reference genome and then incorporates known genomic variants—such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions, and deletions—as alternative paths through this graph [22]. In this graph representation, bases are represented as nodes, and their relationships are represented as edges. Any path through the graph defines a string of bases that exists in either the reference genome or one of its known variants, thereby capturing genetic diversity without the need for a completely separate reference for each individual [22].

The key innovation is the transformation of this genome graph into a prefix-sorted graph, which is more efficient for search and storage. This is achieved through a table representation that leverages the Last-First (LF) mapping property, a crucial characteristic of the FM-index. This property allows the implicit construction of edge information without storing node IDs directly, leading to a substantial reduction in memory requirements [22].

Hierarchical Indexing for Practical Efficiency

To make graph-based alignment fast and practical, HISAT2 implements a Hierarchical Graph FM index (HGFM) [22] [24]. This two-tiered indexing strategy consists of:

- A global GFM index that represents the entire population of human genomes, incorporating known variants.

- A large collection of small, local FM indexes (approximately 57,000 bases each) that collectively cover the entire reference genome and its variants [22] [23].

This hierarchical design offers two critical advantages. First, it enables efficient searching within local genomic regions, which is particularly beneficial for aligning RNA-seq reads that span multiple exons. Second, because these local indexes are small, they can fit within a CPU's cache memory, which is significantly faster than accessing standard RAM, thereby dramatically accelerating the lookup process [22] [24]. HISAT2's implementation requires approximately 6.2 GB of memory for an index that includes the entire human genome (GRCh38) and about 14.5 million common small variants from dbSNP [22] [23]. The incorporation of these variants incurs only a 50-60% increase in CPU time compared to aligning against a linear reference, a reasonable trade-off for the substantial gain in accuracy [22].

Handling Repetitive Sequences

A common challenge in read alignment is handling repetitive sequences that map to numerous genomic locations. HISAT2 incorporates a dedicated repeat index to manage this efficiently [22] [23]. Instead of attempting to report all possible alignments for a highly repetitive read—which would consume prohibitive disk space—HISAT2's repeat indexing approach aligns such reads directly to canonical repeat sequences. This results in one representative repeat alignment per read, streamlining output and conserving resources while still providing the necessary information for downstream analyses [23].

Table 1: Key Components of the HISAT2 Hierarchical Graph FM Index (HGFM)

| Index Component | Description | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Global Graph FM Index (GFM) | Represents the entire reference genome and a large catalogue of known variants (SNPs, indels) as a graph. | Provides the overall map for alignment, capturing population genetic diversity. |

| Local FM Indexes | ~57 Kb indexes that collectively cover the entire genome; small enough to fit in CPU cache. | Enables rapid local search and is crucial for sensitive spliced alignment of RNA-seq reads. |

| Repeat Index | Index of canonical repeat sequences in the genome. | Efficiently handles highly repetitive reads by producing a single, representative alignment. |

Workflow and Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and data structure of the HISAT2 alignment system, from reference and variant input to the final read alignment.

Performance and Comparative Analysis

Benchmarking Against Other Aligners

Extensive benchmarking studies have evaluated HISAT2's performance against other popular RNA-seq aligners. In a study focused on the plant pathogen Erysiphe necator, HISAT2 demonstrated a favorable balance of alignment rate, gene coverage, and speed. It was found to be approximately three times faster than the next fastest aligner, making it highly efficient for large-scale studies [4]. Another study using simulated data from Arabidopsis thaliana highlighted that while the aligner STAR achieved superior base-level alignment accuracy, HISAT2 provided robust performance, with its efficiency being a key advantage [24] [15].

Advantages of a Variant-Aware Index

The primary advantage of HISAT2's graph-based index is its improved accuracy when aligning reads from individuals with genetic differences from the linear reference. By incorporating known variants into the index, HISAT2 reduces the genetic distance between the read and the reference. This leads to fewer mismatches and more confident alignments in polymorphic regions. This capability is crucial for applications like HLA typing and DNA fingerprinting, where precise mapping in highly variable regions is essential [22]. Compared to other variant-aware aligners that may use memory-intensive k-mer based indexes, HISAT2's GFM implementation is notably more practical for standard computing environments [22].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of HISAT2 with Other RNA-Seq Aligners

| Aligner | Key Algorithmic Feature | Reported Performance Advantages | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| HISAT2 | Hierarchical Graph FM Index (HGFM) | High speed and memory efficiency; accurate spliced alignment; incorporates variants. | Balance of speed, accuracy, and resource usage. |

| STAR | Suffix Array-based seed search | High base-level alignment accuracy; superior splice junction discovery [24] [15]. | Higher memory consumption than HISAT2 [4]. |

| TopHat2 | Earlier FM-index based method | Superseded by HISAT2, which offers greater sensitivity and speed [24] [4]. | No longer recommended for new analyses. |

| SubRead | Aligner of both DNA and RNA-seq | High junction base-level accuracy for alternative splicing analysis [24] [15]. | — |

| BWA | BWT/FM index on linear genome | Good overall performance and alignment rate for DNA sequences [4]. | Not designed for spliced alignment of RNA-seq reads. |

Practical Application Notes and Protocols

A Standard RNA-Seq Analysis Protocol with HISAT2

The following protocol outlines a typical RNA-seq differential expression analysis workflow using HISAT2 for read alignment.

Step 1: Pre-alignment Quality Control (QC) and Trimming

- Procedure: Use tools like

fastporTrim Galoreto remove adapter sequences and trim low-quality bases from raw sequencing reads (FASTQ files). Generate QC reports to assess base quality and sequence content [7]. - Rationale: This step improves the overall mapping rate and alignment accuracy by removing technical artifacts that could interfere with the alignment process.

Step 2: Download and Prepare the Reference Index

- Procedure: Download a pre-built HISAT2 index for your organism of interest (e.g., human, mouse) from the HISAT2 website. Alternatively, build a custom index using

hisat2-buildwith a reference genome sequence (FASTA) and optional annotation files (GTF) for splice sites and known variants (VCF) [23]. - Example Command for Custom Indexing:

Step 3: Align Reads to the Reference

- Procedure: Run HISAT2, specifying the index, processed FASTQ files, and relevant parameters. For RNA-seq data, HISAT2 automatically performs spliced alignment. Providing a known splice junction file (extracted from a GTF annotation) can further improve sensitivity.

- Example Command for Paired-End Alignment:

- Critical Parameters:

--rna-strandness: Specifies stranded library preparation protocol (e.g., RF for Illumina's stranded TruSeq) [25].--dta: Reports alignments tailored for transcript assemblers like StringTie, which can improve downstream assembly accuracy.--novel-splice-site-outside: Enables discovery of novel splice junctions not in the provided annotation.

Step 4: Post-alignment Processing and Downstream Analysis

- Procedure: Convert the SAM output to BAM format, sort, and index it using tools like SAMtools. Then, use quantification tools (e.g., featureCounts, HTSeq) or transcript assemblers (e.g., StringTie) to generate count matrices for differential expression analysis with tools like DESeq2 or edgeR [7].

- Rationale: HISAT2's alignment file is the input for quantifying gene and transcript abundance, the primary goal of many RNA-seq studies.

Table 3: Key Resources for HISAT2-Based RNA-Seq Analysis

| Resource / Reagent | Type | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome (FASTA) | Data File | The baseline genomic sequence against which reads are aligned (e.g., GRCh38 for human). |

| Genome Annotation (GTF) | Data File | Provides coordinates of known genes, transcripts, and exons; used for extracting splice sites for HISAT2 and for quantification. |

| Variant Call Format (VCF) File | Data File | Contains known population variants (e.g., from dbSNP); can be incorporated into the HISAT2 index for variant-aware alignment. |

| HISAT2 Software Suite | Software Tool | The core aligner executable, including the hisat2 aligner and hisat2-build indexer. |

| Pre-built HISAT2 Index | Data File | A ready-to-use index for common model organisms, available from the HISAT2 website, saving computation time. |

| Fastp / Trim Galore | Software Tool | Pre-processing tools for quality control, adapter trimming, and filtering of raw sequencing reads. |

| SAMtools | Software Tool | A suite of utilities for post-processing alignments, including SAM/BAM conversion, sorting, indexing, and statistics. |

Specialized Applications and Extensions

The flexibility of the underlying HISAT2 algorithm has enabled its extension to specialized sequencing technologies. HISAT-3N is a variant designed for nucleotide conversion (NC) techniques such as bisulfite sequencing (BS-seq) and SLAM-seq [26]. These methods involve specific base changes (e.g., C-to-T in BS-seq) that standard aligners treat as errors, leading to mapping failures. HISAT-3N implements a three-nucleotide (3-nt) alignment strategy, where converted bases are masked before alignment, allowing for rapid and accurate mapping of NC-seq data. Benchmarks show that HISAT-3N offers greater alignment accuracy and higher scalability with smaller memory requirements compared to other NC-specific aligners like Bismark and SLAM-DUNK [26].

In the early development of RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) analysis, the determination of where short sequence fragments originated within a reference genome represented a foundational computational challenge. This process, known as read alignment, required specialized "splice-aware" algorithms capable of recognizing exon-intron boundaries in eukaryotic transcripts [4]. Among the first tools to effectively address this challenge was TopHat2, which emerged as a historical standard that enabled researchers to reconstruct transcriptomes by aligning RNA-Seq reads across splice junctions [10]. During its peak adoption, TopHat2 served as a critical component in countless transcriptomic studies, facilitating discoveries across diverse fields from basic biology to clinical research [4].

TopHat2 operated using a multi-step alignment strategy that first mapped reads to the reference genome without allowing gaps, then identified potential exons, assembled transcripts, and finally detected splice junctions to guide the full alignment [10]. This method represented a significant advancement over previous approaches, as it could discover novel splice sites without relying exclusively on existing gene annotations. For several years, TopHat2 maintained its position as one of the most widely cited tools in the RNA-Seq analysis workflow, earning thousands of citations and establishing itself as the default choice for many research laboratories [5].

However, the rapid evolution of sequencing technologies and computational methods eventually revealed substantial limitations in TopHat2's approach. The emergence of faster, more accurate, and more resource-efficient aligners such as HISAT2 and STAR ultimately displaced TopHat2 from its dominant position [27] [10]. Understanding both TopHat2's historical contributions and its technical constraints provides valuable insights into the evolution of bioinformatics tools and informs contemporary software selection processes for modern transcriptomic studies.

Key Limitations and Performance Deficiencies

Comprehensive benchmarking studies and user experiences have consistently identified several critical limitations in TopHat2 that ultimately led to its replacement by next-generation aligners.

Computational Efficiency Constraints

TopHat2's multi-pass alignment strategy proved computationally intensive, resulting in significantly slower processing times compared to subsequent tools. Performance evaluations demonstrated that HISAT2, TopHat2's direct successor, achieved alignment speeds approximately 62 times faster than TopHat2 when processing the same dataset [10]. This substantial performance disparity meant that analyses requiring days to complete with TopHat2 could be finished in hours with newer aligners, dramatically accelerating research workflows.

The memory requirements of TopHat2, while less demanding than some contemporary tools like STAR, still posed challenges for researchers with limited computational resources. TopHat2 utilized the Bowtie alignment algorithm with FM-indexing, which required less memory than suffix array-based methods but still necessitated substantial computational resources for processing large datasets [10]. As sequencing capacities expanded, this limitation became increasingly problematic for laboratories attempting to process multiple samples simultaneously.

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics of RNA-Seq Aligners

| Aligner | Alignment Speed (reads/second) | Memory Usage | Alignment Rate (%) | Splice Junction Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TopHat2 | 1,954 [10] | Moderate [10] | 85.85% [27] | Moderate [24] |

| HISAT2 | 121,331 [10] | Low (4.3 GB) [10] | 93.69% [27] | High [24] |

| STAR | 81,412 [10] | High (28 GB) [10] | >90% [24] | High for base-level [24] |

Alignment Accuracy and Sensitivity Limitations

Empirical evaluations using both simulated and real RNA-Seq datasets have consistently demonstrated TopHat2's inferior alignment accuracy compared to modern alternatives. A study comparing aligners using chicken embryo transcriptomic data reported that TopHat2 successfully aligned only 85.85% of reads, significantly fewer than the 93.69% achieved by HISAT2 [27]. This discrepancy in alignment rates directly impacted the sensitivity of downstream analyses, potentially missing biologically relevant transcripts and expression signals.

The accuracy of splice junction detection represents another area where TopHat2 underperforms relative to contemporary tools. Benchmarking research using Arabidopsis thaliana data revealed that TopHat2 demonstrated lower precision in identifying exon-intron boundaries, particularly for complex splicing patterns or novel splice sites [24]. This limitation stemmed from TopHat2's reliance on a more primitive indexing strategy compared to the hierarchical FM-index approach implemented in HISAT2 or the suffix array method used by STAR [4] [10].

Handling of Complex Transcriptomic Features

TopHat2 demonstrated particular limitations when analyzing transcripts with non-canonical splice sites or complex splicing patterns. While the tool effectively identified common GT-AG splice junctions, its performance diminished when encountering rare splice site variants or complex alternative splicing events [10]. This constraint reduced its utility for comprehensive transcriptome characterization, particularly in organisms with diverse splicing mechanisms.

The alignment of reads with short anchors—where only a few bases match each exon—proved challenging for TopHat2's algorithm. HISAT2 addressed this limitation through its hierarchical indexing approach, which enabled more sensitive detection of reads with minimal exon anchoring [10]. This advancement significantly improved the alignment of difficult-to-map reads that TopHat2 frequently missed or assigned incorrectly.

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Methodologies

Standardized Alignment Assessment Framework

Researchers conducting comparative evaluations of RNA-Seq aligners typically employ a standardized workflow to ensure fair and reproducible assessments. The process begins with quality control using tools like FastQC to evaluate read quality, adapter contamination, and other technical metrics [28]. Following quality assessment, read trimming is performed using utilities such as Trimmomatic or Cutadapt to remove low-quality bases and adapter sequences [28].

For reference-based alignment, each aligner requires genome indexing using its specific algorithm before the actual alignment process. TopHat2 utilizes Bowtie indices, HISAT2 employs its hierarchical FM-index, and STAR builds genome indices using suffix arrays [24] [10]. The alignment step processes the cleaned FASTQ files against a reference genome, producing SAM/BAM format files containing mapping positions and splicing information.

Post-alignment quality assessment is conducted using tools like Qualimap or MultiQC to evaluate mapping statistics, while featureCounts or HTSeq performs read quantification [28]. For benchmarking studies, alignment accuracy is typically assessed by comparing results against simulated data with known alignment positions or validated gene models to calculate sensitivity, precision, and false discovery rates [24].

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for Aligner Benchmarking

| Step | Tool Options | Key Outputs | Quality Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Control | FastQC, MultiQC [28] | QC reports, per-base quality | Phred scores, adapter contamination |

| Read Trimming | Trimmomatic, Cutadapt, fastp [28] | Filtered FASTQ files | Retained read percentage, quality profiles |

| Genome Indexing | Aligner-specific methods [24] [10] | Genome indices | Index size, generation time |

| Alignment | TopHat2, HISAT2, STAR [24] [10] | SAM/BAM files | Alignment rate, splice junctions detected |

| Quantification | featureCounts, HTSeq [28] | Count matrices | Assigned reads, multi-mapping statistics |

Reference-Based Benchmarking Using Simulated Data

Comprehensive aligner evaluations often employ simulated datasets where the true origin of each read is known, enabling precise accuracy measurements. The Polyester tool provides a robust framework for generating such simulated RNA-Seq data with biologically realistic characteristics, including differential expression signals and alternative splicing patterns [24]. This approach allows researchers to systematically introduce specific genomic variations, such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), to assess aligner performance under controlled conditions.

Benchmarking studies using Arabidopsis thaliana data have demonstrated that at the read base-level assessment, STAR showed superior performance with over 90% accuracy across different testing conditions, while SubRead excelled in junction base-level assessment with over 80% accuracy [24]. TopHat2 consistently underperformed in these evaluations, particularly in junction-level accuracy where precise splice site identification is critical [24].

Table 3: Essential Resources for RNA-Seq Alignment Analysis

| Resource Type | Specific Tools | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Quality Control | FastQC, MultiQC [28] | Assess read quality, GC content, adapter contamination, and sequence duplication |

| Read Trimming | Trimmomatic, Cutadapt [28] | Remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases to improve alignment accuracy |

| Reference Genomes | ENSEMBL, UCSC, NCBI | Provide species-specific genomic sequences for read alignment and annotation |

| Gene Annotations | GTF/GFF files [28] | Define genomic coordinates of genes, exons, and transcripts for guided alignment |

| Alignment Software | HISAT2, STAR, TopHat2 [24] [10] | Perform splice-aware mapping of RNA-Seq reads to reference genomes |

| Quantification Tools | featureCounts, HTSeq [28] | Generate count matrices by assigning aligned reads to genomic features |

| Performance Assessment | Qualimap, Picard Tools [28] | Evaluate mapping statistics, coverage uniformity, and other quality metrics |

Transition to Modern Alignment Solutions

The limitations of TopHat2 precipitated a transition to more efficient and accurate alignment solutions, with HISAT2 and STAR emerging as the contemporary standards. HISAT2, developed by the same team that created TopHat2, implemented a hierarchical graph FM-index (HGFM) that enabled faster mapping with lower memory requirements [10]. This approach allowed HISAT2 to achieve 62-fold speed improvements over TopHat2 while maintaining higher accuracy, making it the natural successor for most applications [10].

STAR employs a fundamentally different algorithm based on suffix arrays that provides ultra-fast alignment capabilities, though with higher memory requirements than HISAT2 [10]. STAR's unique strength lies in its two-pass alignment method, which enhances splice junction detection sensitivity by leveraging information from initial alignments to guide subsequent mapping [10]. This approach has proven particularly valuable for detecting novel splice sites and complex splicing patterns that challenge other aligners.

For researchers considering aligner selection, the choice between HISAT2 and STAR typically involves balancing computational resources against analytical requirements. HISAT2 offers an optimal balance of accuracy and efficiency for standard computing environments, with minimal memory requirements (approximately 4.3 GB for the human genome) making it accessible for researchers without high-performance computing infrastructure [10]. STAR excels in processing speed and junction detection but demands substantial RAM (approximately 28 GB for human genome alignment), necessitating robust computational resources [10].

TopHat2 occupies an important position in the history of bioinformatics as a pioneering tool that enabled widespread adoption of RNA-Seq technology during a critical period of genomic innovation. Its development addressed the fundamental challenge of splice-aware alignment when few alternatives existed, supporting countless research discoveries and establishing analysis paradigms that influenced subsequent tool development. The tool's limitations in speed, accuracy, and resource efficiency ultimately reflected the rapid pace of advancement in both sequencing technologies and computational methods rather than fundamental flaws in its design approach.

The transition from TopHat2 to modern aligners illustrates broader trends in bioinformatics tool development, including the prioritization of computational efficiency for handling exponentially growing dataset sizes and the refinement of algorithms for improved biological accuracy. Contemporary alternatives like HISAT2 and STAR have built upon TopHat2's foundational concepts while implementing more sophisticated indexing strategies and alignment methodologies. For current researchers, understanding TopHat2's legacy provides valuable context for selecting contemporary tools and anticipating future developments in the evolving landscape of transcriptomic analysis.

RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) has emerged as a powerful tool for assessing genome-wide gene expression, revolutionizing various fields of biology and drug development [29]. The bioinformatic analysis of an RNA-Seq experiment involves a series of consequential steps where the output of one step becomes the input for the next. This process transforms raw sequencing data into biologically meaningful insights about differential gene expression [30]. Central to this pipeline are specific file formats that store and communicate different types of data at each stage. Understanding these formats—FASTQ, BAM/SAM, and GTF/GFF—is fundamental for researchers interpreting RNA-Seq results, especially in the context of aligning sequences using tools like STAR, HISAT2, and TopHat2 [5] [4] [31]. This guide provides a detailed overview of these essential formats, their roles in the analysis workflow, and practical protocols for their manipulation, framed within contemporary research on alignment tools.

The Analyst's Toolkit: Essential File Formats Explained

FASTQ: The Raw Sequence Data Container

The FASTQ format is the standard output from high-throughput sequencing instruments such as Illumina machines and stores the raw nucleotide sequences (reads) along with their corresponding quality scores [32] [33].

Structure: Each sequence in a FASTQ file occupies four lines:

- Sequence Identifier: Begins with a

@character, followed by a unique identifier and optional description. - The Raw Sequence Letters: The actual nucleotide sequence (e.g.,

GATTTGGGGTTCAAAGCAGTATCGATCAA...). - Separator Line: Often just a

+character, sometimes followed by the sequence identifier again. - Quality Scores: Encodes the quality for each base in the sequence using ASCII characters [32] [34].

- Sequence Identifier: Begins with a

Quality Scores (Phred Score): The quality score represents the probability that the corresponding base call is incorrect. This score is Phred-scaled and is encoded using a specific ASCII character [32]. The table below illustrates this relationship.

Table 1: Interpretation of Phred Quality Scores

| Phred Quality Score | Probability of Incorrect Base Call | Base Call Accuracy | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 1 in 10 | 90% | Low-quality regions, often trimmed |

| 20 | 1 in 100 | 99% | Minimum acceptable for many analyses |

| 30 | 1 in 1,000 | 99.9% | Standard goal for high-quality sequencing |

| 40 | 1 in 10,000 | 99.99% | High-quality benchmarks |

- Role in Pipeline: FASTQ files are the starting point for RNA-Seq analysis. They are first subjected to quality control (QC) using tools like FastQC and preprocessing (e.g., adapter trimming and quality filtering) with tools like fastp or Trim Galore before alignment [30] [35].

BAM/SAM: The Alignment Map Formats

Once quality-controlled reads are aligned to a reference genome, the results are stored in BAM or SAM formats. These files describe how, and where, each read aligns to the reference sequence [33].

- SAM (Sequence Alignment/Map): This is a human-readable, tab-delimited text format. It consists of a header section (starting with

@) and an alignment section [32] [33]. - BAM (Binary Alignment/Map): This is the compressed, binary representation of SAM. It is much more efficient in terms of storage and computational processing speed, making it the standard for downstream analysis [33] [34].

Key Fields in an Alignment Line: A typical SAM/BAM alignment line has 11 mandatory fields. Crucial ones for RNA-Seq include:

- QNAME: Query template name (read identifier).

- FLAG: Bitwise flag indicating properties of the alignment (e.g., paired-end, strand, etc.).

- RNAME: Reference sequence name (chromosome).

- POS: 1-based leftmost mapping position.

- CIGAR: String that compactly represents the alignment (e.g.,

8M2I4M1D3Mfor 8 matches, 2 insertions, 4 matches, 1 deletion, 3 matches) [33]. - MAPQ: Mapping quality (Phred-scaled probability the alignment is wrong).

Role in Pipeline: BAM files are the primary output of aligners like STAR and HISAT2. They are used for visualizing alignments in genome browsers and, most importantly, for quantifying how many reads map to each gene [30] [35]. The BAI (BAM Index) file is a companion binary index that allows for quick random access to specific genomic regions within a large BAM file [33].

GTF/GFF: The Genome Annotation Formats

GFF (General Feature Format) and GTF (Gene Transfer Format) are file formats used to describe the coordinates and structure of genomic features such as genes, exons, transcripts, and coding sequences [33].

Structure: Both are tab-delimited text files with nine fields per line [33]:

- seqname: The reference sequence (e.g., chromosome name).

- source: The source of the annotation (e.g., a prediction algorithm or database).

- feature: The type of feature (e.g.,

gene,exon,mRNA). - start: The starting position of the feature (1-based).

- end: The ending position of the feature.

- score: A confidence score or

.if not available. - strand: The strand (

+,-, or.). - frame: For CDS features, indicates the reading frame (

0,1,2, or.). - attribute: A semicolon-separated list of tag-value pairs providing additional information (e.g., gene IDs, names).

GTF vs. GFF: GTF is a specific variant of GFF (often considered GFF version 2.5). The main practical difference is in the formatting of the attribute field, with GTF having stricter rules. For many tasks, they are functionally similar and can be interconverted with tools like

gffread[35].Role in Pipeline: The GTF/GFF file is essential for the alignment and quantification steps. Splice-aware aligners like STAR and HISAT2 use the GTF file during genome indexing to incorporate known splice junction information, which dramatically improves alignment accuracy for eukaryotic RNA-Seq data [35]. Subsequently, quantification tools like featureCounts use the GTF file to determine which aligned reads (in the BAM file) should be counted for which gene [36] [35].

Comparative Analysis of Alignment Tools in Modern RNA-Seq Research

The choice of aligner significantly impacts the results of an RNA-Seq study. While TopHat2 was once a widely used tool, it has been superseded by newer, more accurate, and efficient aligners [5] [4].

Table 2: Comparison of HISAT2, STAR, and TopHat2 Aligners

| Feature | HISAT2 | STAR | TopHat2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Underlying Algorithm | FM-Index (using Bowtie2) [4] [31] | Suffix Array [4] [31] | FM-Index (using Bowtie) |

| Speed | Very Fast (~3x faster than next fastest) [4] | Fast [5] | Slow [5] |

| Memory Usage | Low [5] | High (e.g., ~28GB for human) [5] | Moderate |

| Alignment Accuracy | High, but can be prone to misaligning reads to retrogene loci [31] | High, generates precise alignments, robust for FFPE samples [31] | Lower performance, particularly with default settings [5] [4] |

| Recommended Use Case | Standard analyses, especially on systems with limited RAM [5] | Analyses requiring high precision; complex genomes; FFPE samples [31] | Generally not recommended for new projects [5] |

Research comparing aligners using real-world data, such as FFPE breast cancer samples, has highlighted these performance differences. One study found that STAR generated more precise alignments than HISAT2, which was more prone to misaligning reads to retrogene genomic loci [31]. This underscores the importance of tool selection for clinical and complex research data.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: A Standard RNA-Seq Alignment and Quantification Workflow

This protocol outlines the steps from raw FASTQ files to a count matrix, suitable for differential expression analysis with tools like DESeq2 or edgeR [36] [35].

Research Reagent Solutions (Software & Data)

Table 3: Essential Tools and Materials for the RNA-Seq Protocol

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| SRA Toolkit | Downloads sequencing data from public repositories like NCBI SRA [36]. |

| FastQC | Performs initial quality control on raw FASTQ files, generating an HTML report [35]. |

| fastp / Trim Galore | Trims adapter sequences and low-quality bases from reads [36] [35]. |

| STAR Aligner | A splice-aware aligner for mapping RNA-Seq reads to a reference genome [35]. |

| HISAT2 Aligner | A memory-efficient, splice-aware aligner [35]. |

| SAMtools | Utilities for processing, sorting, indexing, and viewing SAM/BAM files [36] [34]. |

| featureCounts | Quantifies reads that map to genomic features (e.g., genes) defined in a GTF file [35]. |

| Reference Genome (FASTA) | The genome sequence of the target organism (e.g., from ENSEMBL). |

| Genome Annotation (GTF) | The file containing coordinates of genes, exons, and other features for the genome [35]. |

Procedure

Data Acquisition and Quality Control

Read Trimming and Cleaning

- Trim adapters and low-quality bases using Trim Galore, which automates the use of Cutadapt and FastQC.

- Re-run FastQC on the trimmed FASTQ files to confirm improved quality.

Genome Indexing (Preparatory Step)

- This is a one-time step for a given genome and annotation combination.

- For STAR [35]:

- For HISAT2: First build a HISAT2 index from the FASTA file, or download a pre-built one.

Read Alignment

Read Quantification

- Use

featureCountsto generate a count table based on the aligned BAM files and the GTF annotation file [35]. The resultingcounts.txtfile is the final output of this stage and serves as the input for differential expression analysis in R with packages like DESeq2 or edgeR.

- Use

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete RNA-Seq data analysis pipeline, highlighting the key file formats at each stage.

Diagram 1: RNA-Seq analysis workflow and file formats.

Advanced Protocol: Pathogen-First Mapping for Dual RNA-Seq

In studies of host-pathogen interactions (dual RNA-Seq), pathogen reads can be a small fraction of the total dataset. A traditional "host-first" mapping approach can lead to the misalignment of shorter pathogen reads to the host genome. An alternative "pathogen-first" mapping strategy can recover more true pathogen reads [36].

Procedure

- Follow steps 1-3 from the standard protocol to download and clean the dual RNA-Seq reads.

- Create two separate reference genome indices: one for the pathogen (e.g., using BWA) and one for the host (e.g., using HISAT2) [36].

- First Mapping Pass - Pathogen:

- Align the cleaned reads directly to the pathogen genome.

- Extract Unmapped Reads:

- Use SAMtools to extract reads that did not align to the pathogen.

- Convert these unmapped reads back to FASTQ format using

bedtools bamtofastq[36].

- Second Mapping Pass - Host:

- Align the unmapped reads (which are predominantly host) to the host genome using a standard RNA-Seq aligner like HISAT2 or STAR [36].

- Proceed with quantification and downstream analysis for the host and pathogen BAM files separately.

This method prevents the loss of pathogen information and provides a more accurate picture of the pathogen's transcriptome during infection [36].

Diagram 2: Pathogen-first mapping for dual RNA-Seq.

From Theory to Practice: A Step-by-Step Alignment Workflow from Raw Reads to Count Matrix

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, the steps taken before alignment—quality control and adapter trimming—are not merely procedural formalities but foundational determinants of all downstream results. The reliability of conclusions regarding differential gene expression, transcript isoform detection, and biological interpretation is directly contingent upon the quality of the initial data processing [37]. Inadequate quality control can lead to incorrect differential expression results, low biological reproducibility, and ultimately, wasted resources and compromised scientific conclusions [37]. This protocol establishes a robust framework for pre-alignment processing, specifically designed to support sophisticated alignment methodologies such as STAR, HISAT2, and TopHat2 within a comprehensive RNA-seq research thesis. By implementing systematic quality assessment with FastQC and strategic read trimming with either fastp or Trimmomatic, researchers ensure that their alignment inputs are optimized for accuracy, thereby enhancing the validity of all subsequent analytical outcomes.

Theoretical Foundation: Quality Metrics and Trimming Algorithms

Decoding FASTQ Quality Scores

The FASTQ file format serves as the fundamental data structure for next-generation sequencing reads, containing both sequence data and corresponding quality information [38]. Each read within a FASTQ file comprises four lines: a header (beginning with @), the nucleotide sequence, a separator line (often beginning with +), and a quality score string where each character encodes the probability of an incorrect base call [38].

The Phred quality score (Q) is calculated logarithmically as Q = -10 × log10(P), where P represents the probability that a base was called erroneously [38]. This probabilistic interpretation enables straightforward assessment of base-calling reliability:

Table 1: Interpretation of Phred Quality Scores

| Phred Quality Score | Probability of Incorrect Base Call | Base Call Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 1 in 10 | 90% |

| 20 | 1 in 100 | 99% |

| 30 | 1 in 1000 | 99.9% |

| 40 | 1 in 10,000 | 99.99% |

In practice, RNA-seq data generally requires a minimum quality score of Q30 for confident downstream analysis, indicating a 99.9% base call accuracy rate [37].

Adapter Contamination and Its Consequences

Adapter sequences become incorporated into reads primarily when the DNA fragment length is shorter than the sequencing read length, resulting in "read-through" into the adapter sequence [39]. This phenomenon occurs frequently in RNA-seq libraries where insert size distribution may include fragments shorter than the read length [39]. The presence of residual adapter sequences poses significant challenges for alignment, as these non-biological sequences prevent reads from mapping correctly to the reference genome or transcriptome, thereby reducing mapping efficiency and potentially introducing biases in transcript quantification [40].

Algorithmic Approaches to Quality Trimming

Trimming tools employ distinct algorithmic strategies for identifying and removing adapter sequences and low-quality bases: