RNA-seq Software Showdown: A Performance Evaluation Guide for Precision Research

This article provides a comprehensive performance evaluation of RNA-seq software, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

RNA-seq Software Showdown: A Performance Evaluation Guide for Precision Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive performance evaluation of RNA-seq software, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It guides the selection of optimal tools for precise gene expression analysis by exploring foundational principles, comparing mainstream and emerging methodologies, offering troubleshooting strategies, and presenting validation benchmarks. The review synthesizes findings from major comparative studies to deliver actionable insights for designing robust, reproducible RNA-seq workflows that enhance biomarker discovery and therapeutic development.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles of RNA-seq Analysis

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become a cornerstone technology in genomics, enabling researchers to analyze gene expression with high precision and explore diverse biological questions [1]. The journey from raw sequencing reads to actionable biological insights involves a complex computational workflow, with each step influenced by numerous tool choices and methodological decisions. This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance and capabilities of modern RNA-seq analysis tools, drawing on recent benchmarking studies and the latest software developments. As the technology advances toward 2025, the field has witnessed significant evolution in both experimental approaches and bioinformatics pipelines, with growing emphasis on clinical applications, single-cell resolution, and multi-omics integration [1] [2].

Understanding this workflow is crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who must select appropriate tools and methodologies for their specific research contexts. Recent large-scale benchmarking efforts have revealed substantial variations in performance across different pipelines, particularly in detecting subtle differential expression with potential clinical significance [3]. This guide synthesizes evidence from these systematic evaluations to inform tool selection and workflow design, providing a structured framework for navigating the complex RNA-seq analysis landscape.

Experimental Design: Foundation of a Successful RNA-seq Study

Choosing Between RNA-seq Methodologies

The initial critical decision in any RNA-seq experiment involves selecting the appropriate sequencing methodology, which profoundly impacts downstream analysis options and biological conclusions. The choice between whole transcriptome sequencing and 3' mRNA-seq represents a fundamental trade-off between comprehensiveness and specificity, with each approach offering distinct advantages for particular research scenarios [4].

Table: Comparison of RNA-seq Methodologies

| Parameter | Whole Transcriptome Sequencing (WTS) | 3' mRNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Applications | Alternative splicing, novel isoforms, fusion genes, non-coding RNA analysis | Gene expression quantification, high-throughput screening, degraded sample analysis |

| Transcript Coverage | Distributed across entire transcript | Localized to 3' end |

| RNA Types Captured | Coding and non-coding RNAs | Polyadenylated mRNAs only |

| Recommended Sequencing Depth | Higher depth required (varies by application) | 1-5 million reads/sample |

| Workflow Complexity | More complex (requires rRNA depletion or polyA selection) | Streamlined (built-in polyA selection) |

| Data Analysis Complexity | Higher (requires normalization for transcript length) | Lower (direct read counting) |

| Optimal Sample Types | High-quality RNA, prokaryotic RNA | FFPE, degraded RNA, large sample numbers |

| Cost Considerations | Higher per sample (sequencing depth, library prep) | Lower per sample (reduced sequencing needs) |

Whole transcriptome sequencing provides a global view of all RNA types, making it indispensable for investigations requiring information about alternative splicing, novel isoforms, or fusion genes [4]. The random priming approach distributes reads across entire transcripts, enabling comprehensive transcriptome characterization but requiring more complex normalization procedures to account for transcript length biases. This method typically detects more differentially expressed genes due to its broader coverage but demands higher sequencing depth and more sophisticated bioinformatics support [4].

In contrast, 3' mRNA-seq specializes in accurate, cost-effective gene expression quantification through sequencing reads localized to the 3' end of polyadenylated RNAs [4]. This approach generates one fragment per transcript, simplifying data analysis through direct read counting without normalization for transcript coverage. While it detects fewer differentially expressed genes than whole transcriptome approaches, it provides highly similar biological conclusions regarding enriched gene sets and pathway activities, making it particularly suitable for large-scale expression profiling studies and projects involving challenging sample types like FFPE material [4].

Reference Materials and Benchmarking Studies

Recent advances in RNA-seq quality control have been driven by systematic benchmarking efforts using well-characterized reference materials. The Quartet project has introduced multi-omics reference materials derived from immortalized B-lymphoblastoid cell lines from a Chinese quartet family, providing samples with small inter-sample biological differences that reflect the subtle differential expression patterns often seen in clinical samples [3]. These materials complement the established MAQC reference samples characterized by larger biological differences, enabling comprehensive assessment of RNA-seq performance across varying experimental conditions.

A landmark 2024 benchmarking study across 45 laboratories using these reference materials revealed significant inter-laboratory variations in detecting subtle differential expressions [3]. This real-world assessment generated over 120 billion reads from 1080 libraries, systematically evaluating 26 experimental processes and 140 bioinformatics pipelines. The findings underscore the profound influence of experimental execution and analysis choices on results, highlighting the necessity of rigorous quality control measures, particularly for clinical applications where detecting subtle expression differences is critical [3].

The RNA-seq Computational Workflow: Tools and Performance

Core Analysis Steps and Tool Categories

The computational analysis of RNA-seq data follows a structured workflow with distinct stages, each addressing specific analytical challenges. Understanding the tools available for each step and their performance characteristics is essential for constructing robust, reproducible analysis pipelines.

Table: Core RNA-seq Workflow Steps and Representative Tools

| Workflow Stage | Key Tasks | Representative Tools | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Control | Assess sequence quality, adapter contamination, GC content, duplicates | FastQC, Trim Galore, Picard, RSeQC, Qualimap [5] | Critical for identifying sequencing errors and PCR artifacts; affects all downstream analysis |

| Read Alignment | Map reads to reference genome/transcriptome | STAR, HISAT2, TopHat2 [5] | Balance of speed, memory usage, and accuracy; affects splice junction detection |

| Quantification | Estimate gene/transcript abundance | featureCounts, HTSeq, Kallisto, Salmon, RSEM [5] | Key differences in precision for isoform-level quantification; impacts differential expression results |

| Differential Expression | Identify statistically significant expression changes | DESeq2, edgeR, Limma-Voom, NOISeq [5] | Varying statistical approaches and normalization methods; affects false discovery rates |

| Functional Analysis | Interpret biological meaning of results | GO, KEGG, GSEA, DAVID, clusterProfiler [5] | Dependency on quality of differential expression results and annotation databases |

The alignment stage presents a fundamental choice between genome mapping, transcriptome mapping, and de novo assembly strategies [5]. Genome-based alignment offers computational efficiency and sensitivity for detecting novel transcripts but requires a high-quality reference genome. Transcriptome mapping simplifies quantification but may miss unannotated features. De novo assembly becomes necessary when no reference is available but demands higher computational resources and sequencing depth (beyond 30x coverage) [5].

For quantification, tools like Kallisto and Salmon use pseudoalignment approaches that provide faster processing without full alignment, while traditional counting methods like featureCounts generate standard count matrices for differential expression analysis [5]. The choice between these approaches involves trade-offs between speed, accuracy, and compatibility with downstream differential expression tools.

Single-Cell RNA-seq Specialized Tools

The emergence of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has introduced additional analytical challenges and specialized tools. The scRNA-tools database currently catalogs over 1000 software tools designed specifically for scRNA-seq analysis, reflecting the rapid methodological development in this area [6].

Table: Leading Single-Cell RNA-seq Analysis Tools in 2025

| Tool | Platform | Primary Strengths | Applications | Integration Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scanpy | Python | Scalability for large datasets (>1M cells), memory optimization [2] | Large-scale scRNA-seq, spatial transcriptomics [2] | scvi-tools, Squidpy, scverse ecosystem [2] |

| Seurat | R | Data integration, versatility, multimodal support [2] | Cross-sample integration, spatial transcriptomics, CITE-seq [2] | Bioconductor, Monocle ecosystems [2] |

| SCVI-tools | Python | Deep generative modeling, batch correction [2] | Probabilistic modeling, transfer learning, multi-omic integration [2] | Scanpy, PyTorch, AnnData objects [2] |

| Cell Ranger | Pipeline | 10x Genomics data preprocessing, standardization [2] | Processing FASTQ to count matrices, multiome data [2] | Direct integration with Seurat and Scanpy [2] |

| Monocle 3 | R | Trajectory inference, pseudotime analysis [2] | Developmental biology, cellular dynamics [2] | UMAP-based dimensionality reduction [2] |

| BBrowserX | Commercial | User-friendly interface, integrated atlas data [7] | Exploratory analysis, visualization, AI-assisted annotation [7] | Seurat, Scanpy format compatibility [7] |

The single-cell analysis landscape in 2025 reflects a mature ecosystem with specialized tools operating within broadly compatible frameworks [2]. Foundational platforms like Scanpy and Seurat anchor most workflows, while advanced tools like SCVI-tools and Harmony enable sophisticated modeling of latent structures, correction of technical variance, and data denoising with increasing granularity. The integration of spatial context through frameworks like Squidpy, and refined trajectory inference using Monocle 3 and Velocyto, signal a shift toward dynamic, context-aware representations of cell states [2].

Recent trends show a movement from ordering cells on continuous trajectories to integrating multiple samples and leveraging reference datasets, with Python gaining popularity while R remains widely used [6]. The field has also seen growing emphasis on open science practices, with tools embracing open-source licenses (particularly GPL variants for R and MIT/BSD licenses for Python) and code sharing, practices that correlate with increased recognition and citation impact [6].

Benchmarking Results: Experimental Performance Data

Multi-Center Benchmarking Insights

The 2024 Quartet project multi-center study provided comprehensive insights into the real-world performance of RNA-seq methodologies across 45 laboratories [3]. This large-scale evaluation employed multiple metrics to characterize RNA-seq performance, including signal-to-noise ratio based on principal component analysis, accuracy and reproducibility of absolute and relative gene expression measurements, and accuracy of differentially expressed gene detection.

The study revealed that experimental factors including mRNA enrichment strategies and library strandedness, along with each bioinformatics step, emerged as primary sources of variation in gene expression results [3]. Laboratories exhibited varying capabilities in distinguishing biological signals from technical noise, with significantly greater inter-laboratory variations observed when detecting subtle differential expression among Quartet samples compared to the larger differences in MAQC samples. Specifically, the average signal-to-noise ratio for Quartet samples was 19.8 (range 0.3-37.6) compared to 33.0 (range 11.2-45.2) for MAQC samples, highlighting the enhanced challenge of detecting subtle expression changes [3].

In absolute gene expression quantification, all laboratories showed lower Pearson correlation coefficients with the MAQC TaqMan datasets (average 0.825) compared to those with the Quartet TaqMan datasets (average 0.876), indicating that accurate quantification of broader gene sets presents greater challenges [3]. These findings underscore the importance of selecting appropriate analysis pipelines based on the specific experimental context and biological questions being addressed.

Long-Read RNA-seq Tool Performance

As long-read RNA sequencing technologies mature, specialized tools have emerged to handle their unique characteristics. A comprehensive 2023 benchmarking study evaluated long-read RNA-seq analysis tools using in silico mixtures to establish ground-truth datasets [8]. This evaluation combined spike-ins and computational mixtures to assess the performance of various analysis tools when applied to long-read data, addressing the growing importance of isoform-level resolution in transcriptomics.

The study revealed that long-read technologies provide crucial advantages for resolving complex transcriptomes, including complete isoform characterization and improved detection of structural variants [8]. However, the performance of analysis tools varied significantly in accuracy of transcript quantification, isoform detection, and differential expression analysis. These findings highlight the continued need for method development and standardization in long-read RNA-seq analysis, particularly as these technologies become more widely adopted in clinical and research settings.

Analysis Pipelines: From Command Line to Commercial Platforms

Accessible Pipeline Solutions

For researchers without extensive bioinformatics expertise, several user-friendly pipelines have been developed to streamline RNA-seq analysis. RNA-SeqEZPZ represents one such approach, offering a point-and-click interface for comprehensive transcriptomics analysis with interactive visualizations [9]. This automated pipeline packages all software within a Singularity container to eliminate installation issues and provides both graphical and command-line interfaces for flexibility.

The pipeline enables end-to-end analysis from raw FASTQ files through differential expression and pathway analysis, with scalability across computing platforms via a Nextflow implementation [9]. This approach demonstrates the growing trend toward making sophisticated RNA-seq analysis accessible to broader research communities, reducing computational barriers while maintaining analytical rigor and reproducibility.

Commercial Integrated Platforms

The commercial landscape for RNA-seq analysis has expanded significantly, with multiple platforms now offering integrated solutions for single-cell and bulk RNA-seq data.

Table: Commercial scRNA-seq Analysis Platforms (2025)

| Platform | Best For | Key Features | Cost Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nygen | AI-powered insights, no-code workflows [7] | Automated cell annotation, batch correction, cloud-based | Free tier (limited); Subscription from $99/month [7] |

| Omics Playground | Multi-omics collaboration [7] | Bulk RNA-seq, scRNA-seq, pathway analysis, drug discovery | Free trial (limited size); Contact for plans [7] |

| Partek Flow | Modular, scalable workflows [7] | Drag-and-drop workflow builder, local/cloud deployment | Free trial; Subscriptions from $249/month [7] |

| ROSALIND | Team collaboration, interpretation [7] | GO enrichment, automated annotation, interactive reports | Free trial; Paid plans from $149/month [7] |

| Loupe Browser | 10x Genomics data visualization [7] | 10x pipeline integration, spatial analysis, t-SNE/UMAP | Free (requires 10x data) [7] |

These platforms typically offer cloud-based infrastructure, encrypted data storage, compliance-ready backups, and varying levels of computational resources [7]. The choice between open-source tools and commercial platforms involves trade-offs between customization, cost, support, and computational expertise required, with commercial solutions generally offering lower barriers to entry for researchers without bioinformatics support.

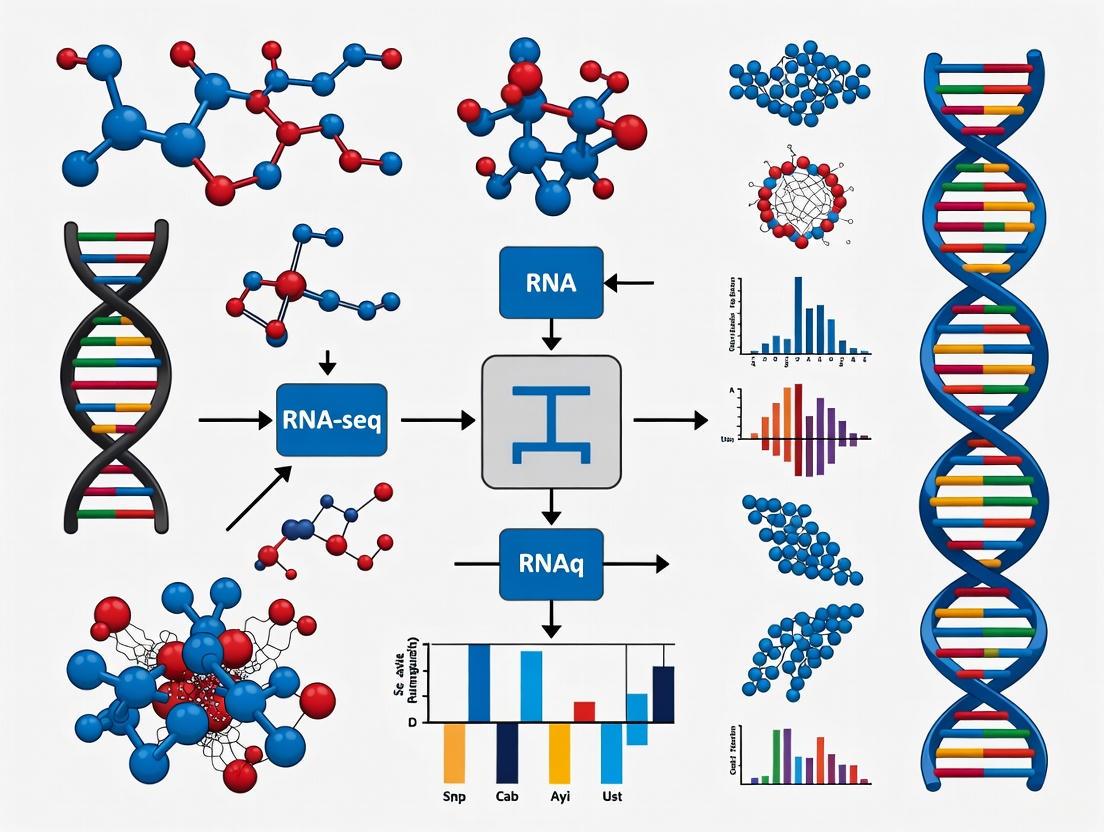

Visual Guide to the RNA-seq Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete RNA-seq analysis workflow, highlighting key decision points and tool categories at each stage:

RNA-seq Analysis Workflow and Key Decisions

Successful RNA-seq experiments require careful selection of reference materials, reagents, and computational resources. The following table details key components of a robust RNA-seq workflow:

Table: Essential RNA-seq Research Reagents and Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | Quartet reference materials, MAQC samples, ERCC spike-ins [3] | Quality control, pipeline benchmarking, cross-study normalization | Quartet for subtle expression, MAQC for large differences [3] |

| Spike-in Controls | ERCC RNA controls, SIRV standards [3] [8] | Quantification accuracy, normalization controls, quality assessment | Essential for evaluating technical performance [3] |

| Annotation Databases | GENCODE, RefSeq, Ensembl, NCBI GEO, ArrayExpress [5] | Gene annotation, expression database, metadata standards | Choice affects mapping rates and interpretation [4] |

| Data Repositories | GEO, SRA, ENA, ArrayExpress, ENCODE [5] | Data deposition, reproducibility, meta-analysis | Essential for open science and comparative studies |

| Computational Infrastructure | Cloud platforms, HPC clusters, Workflow systems (Nextflow, Snakemake) [9] | Data processing, storage, analysis scalability | Containerization (Singularity) aids reproducibility [9] |

These resources form the foundation of reproducible, high-quality RNA-seq research. Reference materials like the Quartet and MAQC samples enable standardized performance assessment across laboratories and platforms [3]. Spike-in controls provide internal standards for evaluating technical performance, particularly important for detecting subtle expression differences with potential clinical significance. Comprehensive annotation databases ensure accurate interpretation of results, while data repositories facilitate open science and collaborative research.

The RNA-seq analysis landscape in 2025 presents researchers with both unprecedented opportunities and significant challenges. The expanding toolkit of computational methods enables sophisticated biological discoveries but requires careful navigation to select appropriate methodologies for specific research contexts. Evidence from large-scale benchmarking studies indicates that experimental factors and bioinformatics choices collectively contribute to variations in results, emphasizing the importance of rigorous quality control and methodology selection [3].

As the field evolves toward clinical applications, the accurate detection of subtle differential expression becomes increasingly critical. The complementary use of reference materials like the Quartet and MAQC samples provides robust quality assessment across different expression ranges [3]. Similarly, the choice between whole transcriptome and 3' mRNA-seq approaches should align with research goals, weighing the need for comprehensive transcript characterization against the efficiency of targeted expression profiling [4].

The growing single-cell RNA-seq ecosystem offers powerful tools for cellular heterogeneity analysis but demands specialized computational approaches [2] [6]. Foundational platforms like Seurat and Scanpy continue to dominate, while specialized tools address specific challenges including integration, trajectory inference, and spatial context. Commercial platforms lower accessibility barriers but may limit customization compared to open-source alternatives [7].

By understanding the performance characteristics, strengths, and limitations of available tools, researchers can construct optimized RNA-seq workflows tailored to their specific biological questions and experimental designs. This objective comparison provides a framework for informed tool selection, supporting robust, reproducible RNA-seq analysis across diverse research applications.

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) experiments, quality control (QC) is not merely a technical formality but a critical step that ensures the accuracy of biological interpretations and the validity of downstream findings [10]. The reliability of conclusions drawn from RNA-seq, such as differential gene expression or transcript isoform quantification, is directly dependent on the quality of the data obtained at every stage of the experimental workflow [10]. Lack of proper quality control can lead to incorrect differential gene expression results, low biological reproducibility, wasted resources, and ultimately, findings with low publication potential [10]. Within the broader context of RNA-seq software comparison research, establishing robust QC protocols using tools like FastQC and MultiQC forms the essential first defense against technical artifacts and misleading biological conclusions.

The multi-layered nature of RNA-seq data—spanning sample preparation, library construction, sequencing performance, and bioinformatics processing—creates multiple points where errors or biases can occur [10]. Quality control serves to detect these deviations early, preventing cascading effects that could compromise entire analyses. This comparative guide examines the performance, integration, and practical application of key QC tools within modern RNA-seq pipelines, providing researchers with evidence-based recommendations for implementing effective quality assessment strategies.

Core QC Tool Capabilities

FastQC stands as the initial quality assessment tool for raw sequencing data, providing comprehensive metrics on base quality, GC distribution, adapter contamination, and read length distribution from FASTQ files [10]. It serves as the first line of defense in identifying potential issues originating from the sequencing process itself before proceeding to downstream analysis.

MultiQC addresses the challenge of summarizing and comparing QC results across multiple samples and analysis tools, revolutionizing QC reporting by aggregating results from many bioinformatics tools into a single interactive HTML report [11] [12] [13]. It recursively searches through directories for recognizable log files from supported tools (over 150 as of 2025), parses relevant information, and generates consolidated visualizations that enable researchers to quickly identify outliers and inconsistencies across entire datasets [11] [13] [14]. Unlike analytical tools, MultiQC does not perform analysis itself but creates standardized reports from existing tool outputs [14].

Expanding QC to Long-Read Technologies

With the maturation of long-read sequencing technologies such as Oxford Nanopore (ONT) and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio), specialized QC tools have emerged to address their unique characteristics. LongReadSum (2025) fills a critical gap as a high-performance tool for generating comprehensive QC reports for long-read data formats [15]. It efficiently processes large datasets and provides technology-specific metrics such as read length distributions (N50 values), base modification information, and signal-level data visualization from ONT POD5 and FAST5 files [15].

Table 1: Core Quality Control Tools for RNA-seq Analysis

| Tool | Primary Function | Input Formats | Key Metrics | Technology Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FastQC | Initial quality assessment of raw sequencing data | FASTQ, BAM, SAM | Base quality, GC content, adapter contamination, sequence duplication | Short-read sequencing |

| MultiQC | Aggregate and compare QC results from multiple tools and samples | Outputs from >150 bioinformatics tools | Summary statistics across samples, batch effect detection, consistency metrics | All sequencing technologies |

| LongReadSum | Comprehensive QC for long-read sequencing data | POD5, FAST5, unaligned BAM, FASTA, FASTQ | Read length distributions (N50), base modifications, signal intensity | Long-read sequencing (ONT, PacBio) |

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking Data

Integration in Validated RNA-seq Pipelines

Recent benchmarking studies of RNA-seq methodologies have consistently incorporated FastQC and MultiQC as essential QC components. A 2024 study evaluating 192 alternative RNA-seq methodological pipelines utilized FastQC for initial quality assessment of raw sequencing reads, establishing it as a fundamental first step in processing Illumina HiSeq 2500 paired-end RNA-seq data [16]. The researchers emphasized that proper quality control at the initial stages was crucial for obtaining accurate results in downstream quantification and differential expression analysis.

In a robust pipeline for RNA-seq data published in 2025, the preprocessing phase was performed using a combination of FastQC, Trimmomatic, and Salmon [17]. FastQC ensured quality control of raw sequencing reads by identifying potential sequencing artifacts and biases before any processing occurred. This pipeline specifically highlighted the importance of integrating multiple QC checkpoints throughout the analysis workflow, with MultiQC serving as the aggregating tool for comparing results across all samples [17].

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The performance of QC tools is often evaluated through their ability to identify problematic samples and technical artifacts that would compromise downstream analysis. In practical implementations, MultiQC has demonstrated particular value in processing complex datasets with multiple samples by providing:

- Unified Reporting: Compilation of results from FastQC, alignment tools (STAR), quantification tools (Salmon), and comprehensive QC tools (Qualimap) into a single interactive report [12]

- Batch Effect Detection: Identification of systematic technical variations arising from different experimental conditions, library preparation dates, or sequencing runs [12] [10]

- Sample-Level Comparison: Simultaneous visualization of key metrics across all samples, enabling rapid identification of outliers [11] [12]

For long-read RNA-seq technologies, LongReadSum addresses the growing need for efficient processing of large datasets, with benchmarks showing it can process an aligned BAM file (57 gigabases, N50 of 22 kilobases) from a single PromethION flow cell in approximately 15 minutes using 8 threads on a 32-core computer [15]. This performance is critical for handling the increasing data volumes generated by contemporary long-read sequencing platforms.

Table 2: Key QC Metrics and Their Interpretation in RNA-seq Analysis

| QC Metric | Optimal Range | Potential Issues | Impact on Downstream Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base Quality (Q-score) | > Q30 for majority of bases | Declining quality at read ends | Increased alignment errors, false variants |

| Alignment Rate | >70-80% for most species [12] | Low rates may indicate contamination or poor RNA quality | Reduced power for expression quantification |

| rRNA Content | <5% for ribo-depleted libraries | Inadequate rRNA depletion | Wasted sequencing depth on non-informative reads |

| Duplicate Rate | Variable, depends on expression level | Extremely high rates suggest low complexity or over-amplification | Biased expression estimates |

| 5'-3' Bias | Close to 1.0 | Significant deviation indicates RNA degradation | Inaccurate transcript-level quantification |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Standardized QC Workflow for RNA-seq

Implementing a comprehensive QC protocol requires methodical execution at multiple stages of the RNA-seq analysis pipeline. The following workflow represents a consensus approach derived from recent benchmarking studies and best practices:

Raw Data QC (FastQC)

- Execute FastQC on all raw FASTQ files:

fastqc *.fastq.gz - Evaluate key metrics: per-base sequence quality, adapter contamination, GC content distribution

- Use results to guide preprocessing parameters (e.g., trimming stringency)

Preprocessing and Alignment QC

- Perform adapter trimming and quality filtering using tools like Trimmomatic [17] or Cutadapt

- Realign processed reads to reference genome/transcriptome using appropriate aligners (STAR, HISAT2)

- Collect alignment statistics including mapping rates, insert sizes, and duplication levels

Aggregated Reporting (MultiQC)

- Run MultiQC on directory containing all QC outputs:

multiqc . - Generate comprehensive HTML report with interactive plots

- Identify sample outliers and systematic biases across the entire dataset

A typical MultiQC implementation for RNA-seq analysis would incorporate outputs from multiple tools simultaneously [12]:

Benchmarking Methodologies from Recent Studies

Comparative assessments of RNA-seq procedures provide valuable insights into optimal QC implementation. A systematic comparison from 2020 evaluated 192 analysis pipelines using different combinations of trimming algorithms, aligners, counting methods, and normalization approaches [16]. Their benchmarking protocol assessed accuracy and precision based on qRT-PCR validation of 32 genes and detection of 107 housekeeping genes, establishing a robust framework for evaluating pipeline performance.

For long-read RNA-seq, the Singapore Nanopore Expression (SG-NEx) project established a comprehensive benchmark in 2025 by profiling seven human cell lines with five different RNA-seq protocols, including short-read cDNA sequencing, Nanopore long-read direct RNA, and PacBio IsoSeq [18]. This resource enables systematic QC development for long-read data, addressing unique challenges in transcript-level analysis.

RNA-seq Quality Control Workflow Integrating FastQC and MultiQC

Core Software Tools

- FastQC: Initial quality assessment tool that provides comprehensive metrics on raw sequencing data, including per-base quality scores, GC content, adapter contamination, and overrepresented sequences [10]

- MultiQC: Aggregation tool that summarizes results from multiple bioinformatics analyses across many samples into a single interactive report, supporting over 150 common bioinformatics tools [11] [13]

- Trimmomatic: Flexible read trimming tool used for removing adapter sequences and low-quality bases, often employed after initial FastQC analysis [17] [16]

- Salmon: Pseudoalignment tool for transcript quantification that includes built-in QC metrics mapping rate and sample-specific bias detection [17] [12]

- LongReadSum: Specialized QC tool for long-read sequencing data that provides metrics including read length distributions (N50), base modification information, and signal-level data visualization [15]

- Housekeeping Gene Sets: Curated lists of constitutively expressed genes (e.g., 107 genes identified by [16]) used as reference standards for evaluating quantification accuracy across pipelines

- Spike-in Controls: Synthetic RNA sequences with known concentrations (e.g., ERCC, Sequin, SIRVs) added to samples to assess technical performance and enable normalization validation [18]

- qRT-PCR Validation: Orthogonal verification method using targeted amplification of selected genes to confirm RNA-seq findings, considered a gold standard for expression measurement [16]

Within the comprehensive evaluation of RNA-seq software performance, quality control tools like FastQC and MultiQC provide the essential first line of defense against technical artifacts and erroneous biological conclusions. The integration of these tools throughout the analytical pipeline—from raw data assessment to final aggregation of results—ensures the reliability and reproducibility of RNA-seq findings. As sequencing technologies evolve, particularly with the expanding adoption of long-read methodologies, QC tools must similarly advance to address new challenges in data quality assessment.

The benchmarking data and implementation protocols presented here provide researchers with evidence-based strategies for incorporating robust quality control into their RNA-seq workflows. By establishing standardized QC practices and leveraging the complementary strengths of specialized tools, the research community can enhance the validity of transcriptomic studies and strengthen the foundation for subsequent discoveries in basic research and drug development.

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, the initial preprocessing of raw sequencing reads is a critical step that significantly influences all subsequent results, from read mapping to the final interpretation of differential gene expression. Read trimming and filtering tools are designed to remove adapter sequences, primers, poly-A tails, and low-quality bases from high-throughput sequencing reads, thereby improving the quality of data used for downstream analyses. Among the numerous tools available, Trimmomatic and Cutadapt have emerged as two of the most widely used and cited solutions for these preprocessing tasks. Within the broader context of RNA-seq software comparison performance evaluation research, understanding the relative strengths, weaknesses, and optimal application scenarios for these tools is paramount for constructing robust and reproducible bioinformatics pipelines.

The fundamental importance of adapter trimming stems from the nature of library preparation in RNA-seq protocols. When the sequenced RNA fragment is shorter than the read length, the sequencer will continue reading into the adapter sequence. If not removed, these adapter sequences can prevent reads from mapping correctly to the reference genome or transcriptome, leading to inaccurate gene expression quantification. Furthermore, the presence of low-quality bases, particularly at the ends of reads, can similarly hinder alignment and introduce errors in variant calling and transcript assembly. While modern aligners can perform "soft-clipping" of unmapped ends, specialized trimming tools often provide more comprehensive and configurable cleaning of sequencing data.

Cutadapt

Cutadapt is a specialized tool primarily designed to find and remove adapter sequences, primers, poly-A tails, and other types of unwanted sequence from high-throughput sequencing reads in an error-tolerant way. Its core algorithm is based on a local alignment strategy that allows for a user-defined maximum error rate, making it robust to sequencing errors within the adapter sequence itself. Cutadapt supports a wide variety of adapter types, including regular 3' adapters (-a), regular 5' adapters (-g), and anchored versions of both, which require the adapter to appear in full at the very start (5') or end (3') of the read [19]. The tool can process both single-end and paired-end data and includes additional functionality for quality trimming, read filtering, and demultiplexing. A key feature of Cutadapt is its ability to search for and remove multiple different adapter sequences in a single run, which is particularly useful for demultiplexing pooled samples.

Trimmomatic

Trimmomatic employs a pipeline-based architecture where individual processing steps (such as adapter removal, quality filtering, or length thresholding) are applied to each read in a user-specified order. For adapter trimming, it offers two main algorithmic approaches: a "simple" algorithm that looks for approximate matches between the provided adapter sequence and the read, and a more sophisticated "palindrome" mode specifically designed for detecting contaminants at the ends of paired-end reads. Beyond adapter trimming, Trimmomatic incorporates multiple quality control features, including sliding window quality trimming, leading and trailing base trimming, and minimum length filtering. This comprehensive suite of processing steps allows users to construct a customized trimming pipeline tailored to their specific data quality challenges.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Multiple independent studies have systematically evaluated the performance of trimming tools, including Cutadapt and Trimmomatic, across various metrics and dataset types. The following tables summarize key findings from these comparative assessments.

Table 1: Comparison of adapter trimming effectiveness across different tools

| Tool | Algorithm Type | Residual Adapters (Poliovirus iSeq) | Residual Adapters (SARS-CoV-2 iSeq) | Residual Adapters (Norovirus iSeq) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trimmomatic | Sequence-matching | Very Low | Very Low | Very Low |

| Cutadapt | Sequence-matching | Low | Low | Low |

| FastP | Sequence-overlapping | 12.54% | 13.06% | 3.51% |

| AdapterRemoval | Sequence-matching | Low (platform-dependent) | Low (platform-dependent) | Low |

| BBDuk | K-mer based | Very Low | Very Low | Very Low |

| Skewer | K-difference matching | Low (paired reads) | Low (paired reads) | Low |

Source: Data adapted from Mnguni et al. (2024) [20]

Table 2: Read quality metrics after trimming with different tools

| Tool | % Bases ≥Q30 (Poliovirus) | % Bases ≥Q30 (SARS-CoV-2) | % Bases ≥Q30 (Norovirus) | Read Length Retention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trimmomatic | 93.15 - 96.7% | 93.15 - 96.7% | 93.15 - 96.7% | Moderate |

| Cutadapt | - | - | - | High |

| FastP | 93.15 - 96.7% | 93.15 - 96.7% | 93.15 - 96.7% | Moderate |

| AdapterRemoval | 93.15 - 96.7% | 93.15 - 96.7% | 93.15 - 96.7% | Moderate |

| BBDuk | 87.73 - 95.72% | 87.73 - 95.72% | 87.73 - 95.72% | Low |

| Skewer | 87.73 - 95.72% | 87.73 - 95.72% | 87.73 - 95.72% | High |

Source: Data adapted from Mnguni et al. (2024) [20]. Note: Specific values for Cutadapt were not provided in the source, though it was included in the study.

Table 3: Impact on de novo assembly metrics after trimming

| Tool | N50 Value | Max Contig Length | Genome Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trimmomatic | Improved | Improved | 54.8 - 98.9% |

| Cutadapt | - | - | - |

| FastP | Improved | Improved | 54.8 - 98.9% |

| AdapterRemoval | Improved | Improved | 54.8 - 98.9% |

| BBDuk | Lowest | Lowest | 8 - 39.9% |

| Skewer | Improved | Improved | 54.8 - 98.9% |

| Raw Reads | Baseline | Baseline | 8.8 - 87.5% |

Source: Data adapted from Mnguni et al. (2024) [20]. Note: BBDuk-trimmed reads assembled into significantly shorter contigs with poor genome coverage.

A comprehensive study by Mnguni et al. (2024) evaluated six trimming programs on Illumina sequencing data of RNA viruses (poliovirus, SARS-CoV-2, and norovirus) and found that Trimmomatic and AdapterRemoval, both implementing traditional sequence-matching algorithms, most effectively removed adapter sequences across all datasets [20]. The same study reported that tools implementing traditional sequence-matching (Trimmomatic, AdapterRemoval) and overlapping algorithms (FastP) consistently produced reads with the highest percentage of quality bases (Q ≥ 30), ranging from 93.15% to 96.7% compared to 87.73% to 95.72% for other trimmers [20].

Another large-scale comparison by Williams et al. (2020) assessed 192 alternative methodological pipelines for RNA-seq analysis and included Trimmomatic, Cutadapt, and BBDuk as trimming options [16]. While their study focused on differential expression analysis, they noted that non-aggressive trimming should be applied together with wisely chosen read length thresholds to avoid unpredictable changes in gene expression and transcriptome assembly.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standardized Trimming Protocol for RNA-seq Data

To ensure reproducible and comparable results when evaluating trimming tools, researchers should follow a standardized experimental protocol. The following workflow outlines a typical methodology for assessing trimmer performance:

Diagram 1: Standard read preprocessing workflow

Sample Preparation: The benchmark RNA-seq dataset from the SEQC project, which includes Universal Human Reference RNA (UHRR) and Human Brain Reference RNA (HBRR), provides a well-characterized resource for evaluation. Alternatively, simulation data can be generated with known adapter contamination rates (e.g., 0.1%, 0.5%, and 1% of bases being adapter sequences) to precisely control the level of contamination [21].

Quality Control Assessment: Before trimming, assess raw read quality using FastQC v0.11.5 and aggregate results with MultiQC v1.9 to identify pre-existing quality issues, adapter contamination levels, and base quality distributions [20].

Parameter Standardization: To ensure fair comparisons, standardize critical parameters across tools:

- Quality threshold: Phred score > 20

- Minimum read length: 50 bp after trimming

- Adapter sequences: Illumina TruSeq adapters (for RNA-seq)

- Allowable mismatches: Consistent across tools (typically 0.1-0.2 error rate)

Execution with Multiple Threads: Run each trimming tool with 8 CPU threads to minimize processing time and mimic realistic usage scenarios [20] [16].

Performance Evaluation: Compare the following metrics post-trimming:

- Percentage of residual adapter sequences

- Number and percentage of surviving reads

- Distribution of read lengths after trimming

- Percentage of bases with Q ≥ 30

- Runtime and memory usage

- Impact on downstream analyses (mapping rates, assembly statistics)

Specialized Protocol for Viral Genome Analysis

For studies focusing on viral genomes, Mnguni et al. (2024) implemented a specialized protocol:

Sample Selection: Process libraries prepared from random cDNA of poliovirus clinical isolates and amplicons generated from SARS-CoV-2-positive nasopharyngeal swabs and norovirus-positive stool samples sequenced using Illumina 300-cycle (2 × 150 bp, paired-end) MiSeq v2 Micro and iSeq i1 kits [20].

Tool Parameterization:

- For Trimmomatic: Use "adapters and SW" mode with parameters

PE -threads 8 -phred33 ILLUMINACLIP:TruSeq3-PE.fa:2:30:10 LEADING:3 TRAILING:3 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15 MINLEN:36[21]. - For Cutadapt: Use standard parameters with quality cutoff of 20 and minimum length of 36 bp.

Downstream Assessment:

- Assemble trimmed reads de novo using SPAdes v3.15.3.

- Calculate N50, maximum contig length, and genome coverage.

- Perform SNP calling using BCFtools v1.10.2 with appropriate viral reference genomes.

- Evaluate SNP quality and concordance across trimming methods.

Impact on Downstream Analysis Results

The choice of trimming tool can significantly influence downstream RNA-seq analysis results, including gene expression quantification and variant detection. A 2020 study by Chen et al. compared the impact of data preprocessing with Cutadapt, FastP, Trimmomatic, and no trimming on mutation detection and HLA typing [22]. They found that mutation detection frequencies showed noticeable fluctuations and differences depending on the preprocessing method used. Most concerningly, HLA typing directly resulted in erroneous results when using certain trimming tools, highlighting the critical impact of preprocessing choices on clinically relevant applications [22].

In the context of de novo assembly, Mnguni et al. (2024) reported that all trimmers except BBDuk improved N50 and maximum contig length for viral genome assemblies compared to raw reads [20]. Trimmomatic-trimmed reads consistently assembled into long contigs with high genome coverage (54.8% to 98.9%), while BBDuk-trimmed reads produced the shortest contigs with poor genome coverage (8% to 39.9%) [20]. This demonstrates how trimming tool selection can dramatically affect assembly completeness, particularly for viral genomes.

Interestingly, a 2020 study by Tapia et al. suggested that read trimming might be a redundant process in the quantification of RNA-seq expression data, finding that accuracy of gene expression quantification from using untrimmed reads was comparable to or slightly better than that from using trimmed reads [21]. They noted that adapter sequences can be effectively removed by read aligners via 'soft-clipping' and that many low-sequencing-quality bases, which would be removed by read trimming tools, were rescued by the aligner [21]. This finding highlights the context-dependent value of trimming, suggesting that for certain applications (particularly when using modern aligners with soft-clipping capabilities), aggressive trimming may offer limited benefits while reducing usable data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential research reagents and computational tools for RNA-seq preprocessing evaluation

| Category | Item | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | SEQC RNA-seq Reference Samples (UHRR, HBRR) | Benchmark dataset with well-characterized expression profiles for method validation |

| HD753 Reference Genomic DNA | Contains known mutation variations at specific frequencies for evaluating trimming impact on variant detection | |

| Viral Isolates (Poliovirus, SARS-CoV-2, Norovirus) | Provide diverse sequence contexts for evaluating trimming performance across different genomes | |

| Library Prep Kits | TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Kit | Standardized library preparation for RNA-seq experiments |

| NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit | Library preparation for DNA-based studies, including HLA typing | |

| Accel-NGS 2S Plus DNA Library Kit | Specialized library preparation for cell-free DNA studies | |

| Software Tools | FastQC | Initial quality assessment of raw sequencing data |

| MultiQC | Aggregation of quality control metrics across multiple samples | |

| SPAdes | De novo assembly of trimmed reads for contig-based metrics | |

| BCFtools | Variant calling for evaluating trimming impact on mutation detection | |

| RSubread/featureCounts | Read alignment and quantification for gene expression analysis | |

| Validation Methods | TaqMan RT-PCR | Gold standard validation of gene expression results |

| HLA Typing Assays | Specialized validation for immunogenetics applications | |

| Digital PCR | Absolute quantification of specific targets for method validation |

Based on the comprehensive evaluation of experimental data and performance metrics, the following best practice recommendations emerge for selecting and implementing read trimming tools in RNA-seq analysis pipelines:

For maximum adapter removal effectiveness, particularly in applications where complete elimination of adapter sequences is critical (such as viral genome assembly or mutation detection), Trimmomatic demonstrates superior performance, consistently achieving near-complete adapter removal across diverse datasets [20].

For flexibility in handling diverse adapter configurations and specialized sequence types, Cutadapt offers more granular control through its support for multiple adapter types (regular, anchored, and non-internal) and ability to handle IUPAC wildcard characters [19].

For time-sensitive applications or when processing large datasets, consider that several studies have noted significant differences in processing speed between tools, with some modern alternatives like fastP offering substantially faster processing times, though potentially at the cost of some accuracy in adapter detection [23] [24].

For clinical applications where variant detection accuracy is paramount, carefully validate the impact of your chosen trimming tool on mutation calling, as studies have demonstrated tool-specific fluctuations in mutation detection frequencies and potential for erroneous results in downstream applications like HLA typing [22].

Finally, researchers should consider that the necessity of trimming itself may be application-dependent. For standard gene expression quantification using modern aligners with soft-clipping capabilities, minimal or no trimming may yield comparable or even superior results to aggressive trimming, while significantly reducing analysis time [21].

The optimal choice between Trimmomatic, Cutadapt, or alternative trimming tools ultimately depends on the specific research context, data characteristics, and analytical priorities. By understanding the performance characteristics and limitations of each tool documented in systematic comparisons, researchers can make informed decisions that enhance the reliability and reproducibility of their RNA-seq analyses.

In the field of transcriptomics, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become the predominant method for quantifying gene expression. The computational analysis of RNA-seq data can broadly follow two divergent paths: alignment-based methods, which map reads to a reference genome, and pseudoalignment methods, which assign reads to transcripts without precise base-level mapping [25]. This guide objectively compares the performance, underlying algorithms, and ideal applications of these two approaches within the broader context of RNA-seq software evaluation, providing researchers and drug development professionals with evidence-based insights for selecting appropriate methodologies.

Core Computational Principles

Alignment-Based Methods

Traditional alignment involves finding the exact genomic origin of each sequencing read.

- Spliced Alignment: Unlike DNA-seq tools, RNA-seq aligners must account for introns. Tools like STAR and HISAT2 use sophisticated algorithms to handle reads that span exon-exon junctions [26] [27].

- Reference Genome: Reads are mapped to a reference genome, requiring a high-quality, annotated genome sequence [26].

- Output: Produces sequence alignment/map (SAM) or binary alignment/map (BAM) files detailing the precise genomic coordinates of each read [26].

Pseudoalignment Methods

Pseudoalignment sacrifices precise genomic location for dramatic gains in speed and efficiency.

- Transcriptome-Based: Reads are directly assigned to transcripts from a reference transcriptome using k-mer matching or lightweight algorithms [25] [28].

- Probabilistic Assignment: Tools like Salmon and Kallisto use probabilistic models to resolve multi-mapping reads, often providing more accurate transcript-level quantification [25] [28].

- Algorithmic Efficiency: By avoiding base-by-base alignment, these methods bypass computationally intensive steps, working directly with pre-built transcript indices [28].

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Experimental benchmarks reveal distinct performance trade-offs between these approaches. The following table synthesizes findings from systematic evaluations [25] [28] [29].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Representative Alignment and Pseudoalignment Tools

| Performance Metric | STAR (Alignment) | HISAT2 (Alignment) | Salmon (Pseudoalignment) | Kallisto (Pseudoalignment) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speed (Relative) | Moderate | Fast | Very Fast | Extremely Fast |

| Memory Usage | High (~30GB human genome) | Moderate (~5GB) | Low | Low |

| Base-Level Accuracy | High (≥90%) [27] | High | N/A (No base-level output) | N/A (No base-level output) |

| Junction Detection Accuracy | Varies [27] | Varies [27] | N/A | N/A |

| Quantification Accuracy | High when combined with featureCounts | High when combined with featureCounts | High (with bias correction) | High |

| Key Strength | Sensitive splice junction detection [30] | Balanced resource use [28] [31] | Speed & transcript-level resolution [25] | Speed & simplicity [25] |

Impact on Differential Expression Analysis

The choice of alignment method directly influences downstream differential expression (DE) results. A systematic comparison of 192 analysis pipelines found that while overall results between pipelines were comparable, the specific combination of tools significantly impacted the final list of differentially expressed genes [29]. Studies have shown that pseudoaligners like Kallisto and Salmon show similar precision and accuracy to the best alignment-based pipelines when followed by robust DE tools like DESeq2 or limma-voom [25].

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

Benchmarking Alignment Accuracy

Rigorous assessment of aligners requires controlled simulations and defined metrics.

- Base-Level Accuracy Assessment: Using simulated RNA-seq data from a well-annotated genome (e.g., Arabidopsis thaliana), researchers introduce known variations like single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Accuracy is measured by the percentage of correctly mapped read bases compared to the known simulated origin [27].

- Junction-Level Accuracy Assessment: The same simulated data is used to evaluate how well aligners detect reads spanning splice junctions. Performance is measured by sensitivity (ability to find true junctions) and precision (avoiding false junctions) [27].

Validating Quantification Performance

Evaluating the final gene expression estimates is crucial.

- qRT-PCR Validation: The "gold standard" for validation. Researchers select a panel of genes (e.g., 32 genes in a 2020 study) and measure their expression using qRT-PCR. The correlation between qRT-PCR results and the expression values derived from RNA-seq pipelines serves as the benchmark for accuracy [29].

- Housekeeping Gene Stability: Constitutively expressed genes are used to measure the precision and technical variability of different pipelines. Pipelines that show lower variation across these genes are considered more robust [29].

Workflow Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental procedural differences between alignment-based and pseudoalignment-based RNA-seq analysis workflows.

Successful RNA-seq analysis depends on both computational tools and high-quality biological references.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Resources for RNA-seq Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome | GENCODE, Ensembl, RefSeq, UCSC | Provides the coordinate system for alignment. Quality and annotation completeness are critical for accurate mapping and quantification [26]. |

| Annotation File (GTF/GFF) | GENCODE, Ensembl | Links genomic coordinates to gene and transcript models; essential for the summarization step in alignment-based workflows [26]. |

| Alignment-Based Tools | STAR, HISAT2, Subread | Perform splice-aware mapping of reads to a reference genome, generating BAM files for downstream analysis [28] [27]. |

| Pseudoalignment Tools | Salmon, Kallisto | Rapidly assign reads to transcripts and generate count estimates without producing base-level alignments [25] [28]. |

| Quantification Tools | featureCounts, HTSeq (for BAM) | Used in alignment workflows to generate count matrices from BAM files. Integrated into pseudoaligners [26]. |

| Differential Expression Tools | DESeq2, edgeR, limma-voom | Statistical packages that take a count matrix as input to identify significantly differentially expressed genes between conditions [25] [28]. |

| Quality Control Tools | FastQC, MultiQC, RSeQC, Qualimap | Assess read quality, alignment metrics, and coverage uniformity to ensure data integrity at each step [28] [32]. |

Alignment and pseudoalignment represent two fundamentally different computational philosophies for RNA-seq analysis. Alignment-based methods (e.g., STAR, HISAT2) provide detailed genomic context, including the discovery of novel splice junctions, at the cost of greater computational resources [27] [30]. In contrast, pseudoalignment methods (e.g., Salmon, Kallisto) offer exceptional speed and efficiency for transcript quantification, making them ideal for rapid gene expression profiling in well-annotated organisms [25] [28].

The choice between them should be guided by the research question and available resources. For projects focused on novel transcript discovery or working with non-model organisms without comprehensive transcriptomes, alignment-based pipelines remain essential. For large-scale differential expression studies where speed, storage, and cost are primary concerns, pseudoalignment provides a robust and highly efficient alternative. As benchmarking studies consistently show, there is no single "best" pipeline; understanding these key computational differences empowers researchers to make informed, strategic decisions for their transcriptomics research and drug development programs [29].

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, normalization is not merely a preliminary step but a critical correction for technical variability that can otherwise obscure true biological signals. Technical biases arise from multiple sources, including varying sequencing depths, library preparation protocols, and RNA composition differences between samples. Without appropriate normalization, these non-biological artifacts can lead to false conclusions in differential expression analysis, fundamentally compromising research validity and reproducibility. This guide objectively compares the performance of leading normalization methods within the broader context of RNA-seq software evaluation, providing researchers with experimental data and methodologies to inform their analytical choices.

Understanding Technical Biases in RNA-Seq Data

Technical biases in RNA-seq data originate from multiple experimental and sequencing processes. Library preparation protocols can introduce significant variability through efficiency differences in reverse transcription, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification. Sequencing depth variations cause samples with higher total read counts to appear to have higher expression across all genes. Gene length bias allows longer transcripts to generate more fragments than shorter transcripts at the same actual abundance. RNA composition effects occur when highly expressed genes in some samples consume disproportionate sequencing resources, skewing the apparent expression of other genes.

These technical artifacts manifest in downstream analyses as batch effects, where samples processed together cluster by technical rather than biological factors. Without correction, these biases can invalidate differential expression results, leading to both false positives and false negatives. Research indicates that inappropriate normalization can affect the expression levels of up to 70% of genes in severe cases, substantially impacting subsequent biological interpretations [25] [33].

Comparative Analysis of Normalization Methods

Multiple normalization strategies have been developed to address different aspects of technical bias, each with distinct theoretical foundations and applications.

Table 1: Key RNA-Seq Normalization Methods and Their Characteristics

| Method | Full Name | Key Principle | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| TPM | Transcripts Per Million | Normalizes for both sequencing depth and gene length | Within-sample comparison; RNA composition stabilization |

| FPKM | Fragments Per Kilobase Million | Similar to TPM but applied to fragments instead of transcripts | Gene expression quantification in single-sample analyses |

| TMM | Trimmed Mean of M-values | Assumes most genes are not differentially expressed | Between-sample comparison; implemented in edgeR |

| RLE | Relative Log Expression | Uses median ratio of gene counts relative to geometric mean | Between-sample comparison; implemented in DESeq2 |

| Upper Quartile | Upper Quartile | Scales counts using upper quartile of gene counts | Robust to highly expressed differentially expressed genes |

Performance Evaluation: Experimental Data

Independent evaluations have systematically compared these normalization methods to establish their relative performance. One comprehensive study analyzing multiple RNA-seq datasets found that TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) demonstrated superior performance in accurately identifying differentially expressed genes, closely followed by RLE (Relative Log Expression) normalization [25]. The same study reported that TPM and FPKM methods showed comparatively lower performance in between-sample comparisons, though TPM remains valuable for within-sample transcript distribution analysis.

Table 2: Normalization Method Performance Comparison

| Method | DEG Accuracy | Handling Sequencing Depth | Composition Bias Correction | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMM | Highest | Excellent | Strong | edgeR |

| RLE | High | Excellent | Strong | DESeq2 |

| TPM | Moderate | Good | Partial | Multiple tools |

| FPKM | Moderate | Good | Partial | Multiple tools |

| Upper Quartile | Moderate-High | Good | Moderate | Various packages |

These performance differences significantly impact downstream biological interpretation. In benchmark studies, pipelines utilizing TMM normalization generated more biologically reproducible results when validated against quantitative PCR data, demonstrating superior sensitivity and specificity in differential expression detection [25].

Experimental Protocols for Normalization Assessment

Benchmarking Methodology

To objectively evaluate normalization performance, researchers employ standardized benchmarking workflows:

Reference Dataset Selection: Use well-characterized RNA-seq datasets with external validation (e.g., qRT-PCR confirmed differentially expressed genes) or spike-in controls.

Pipeline Configuration: Implement identical alignment and quantification steps (e.g., STAR aligner with featureCounts quantification) while varying only normalization methods.

Performance Metrics: Evaluate using:

- False Discovery Rate (FDR): Proportion of falsely identified differentially expressed genes

- Sensitivity: Ability to detect true differentially expressed genes

- AUC-ROC: Overall classification performance

- Rank Correlation: Agreement with validated reference gene lists

Bias Assessment: Quantify residual technical artifacts using:

- PCA plots to visualize batch effect correction

- Distance matrices to assess sample clustering by biological versus technical factors

This methodology was employed in a recent comprehensive evaluation of 288 analysis pipelines, which revealed that proper normalization parameter selection could improve differential expression accuracy by 15-25% compared to default settings [23].

Case Study: Normalization Impact in Toxicogenomics

A 2025 comparative study of microarray and RNA-seq platforms provided concrete evidence of normalization's critical role. When analyzing cannabinoid effects on hepatocytes, researchers found that RLE normalization in DESeq2 effectively minimized platform-specific biases, enabling consistent transcriptomic point of departure (tPoD) values between RNA-seq and microarray technologies despite their fundamentally different measurement principles [34]. This consistency in toxicological benchmarking underscores how proper normalization facilitates comparable results across diverse technological platforms.

Integration in Analysis Workflows

Normalization does not function in isolation but as part of integrated analysis pipelines. The sequential relationship between processing steps and their impact on normalization efficacy is visualized below:

RNA-Seq Analysis Workflow with Normalization

The effectiveness of normalization depends heavily on upstream processing decisions. For example, alignment tools like STAR and HISAT2 exhibit different sensitivity in mapping reads to splice junctions, which subsequently affects count distributions and normalization performance [28] [35]. Similarly, quantification approaches (alignment-based vs. pseudoalignment) generate distinct count distributions that respond differently to normalization methods.

Research Reagent Solutions for Normalization Validation

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Normalization Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Normalization Assessment | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Spike-In Controls | External standards to quantify technical variance; validate normalization accuracy | ERCC (External RNA Controls Consortium) RNA Spike-In Mixes |

| Reference RNA Samples | Well-characterized biological standards for cross-platform normalization comparison | Universal Human Reference RNA, Brain RNA Standard |

| Quality Control Kits | Assess RNA integrity before library preparation; identify samples requiring specialized normalization | Agilent Bioanalyzer RNA kits, TapeStation |

| Alignment Software | Generate raw count data for subsequent normalization | STAR, HISAT2, TopHat2 |

| Differential Expression Tools | Implement specific normalization methods with statistical frameworks | DESeq2 (RLE), edgeR (TMM), limma-voom |

Spike-in controls are particularly valuable for normalization assessment, as they provide known concentrations of exogenous transcripts that enable direct measurement of technical bias. Studies utilizing ERCC spike-ins have demonstrated that global normalization methods like TMM and RLE effectively correct for concentration-dependent biases when properly implemented [33] [34].

Normalization serves as the critical bridge between raw RNA-seq data and biologically meaningful results by systematically removing technical biases. Among available methods, TMM and RLE normalization consistently demonstrate superior performance in comparative benchmarks, though optimal selection depends on specific experimental designs and biological questions. As RNA-seq applications expand into clinical and regulatory domains, robust normalization becomes increasingly essential for generating reliable, reproducible results that can inform drug development and safety assessment. Researchers should prioritize normalization method selection with the same rigor applied to experimental design and laboratory protocols, validating choices against orthogonal methods when investigating novel biological systems or preparing results for regulatory submission.

Toolkit Deep Dive: Aligners, Quantifiers, and Differential Expression Tools

The accurate alignment of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) reads is a foundational step in transcriptomic analysis, enabling downstream applications such as gene expression quantification, novel transcript discovery, and alternative splicing analysis. Splice-aware aligners must precisely map reads that are separated by introns, often ranging from thousands to hundreds of thousands of bases. STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) and HISAT2 (Hierarchical Indexing for Spliced Alignment of Transcripts 2) have emerged as two of the most widely used tools for this challenging computational task. While both are designed to handle spliced alignments, they employ fundamentally different algorithms and indexing strategies that lead to significant differences in performance, accuracy, and computational resource requirements.

Understanding the trade-offs between these aligners is crucial for researchers designing RNA-seq experiments, particularly as studies scale to larger sample sizes and more complex genomes. This comparison guide provides an objective evaluation of STAR and HISAT2 performance based on current benchmarking studies, experimental data, and practical implementation considerations. We examine key performance metrics including alignment accuracy, computational efficiency, memory usage, and suitability for different experimental contexts, providing researchers with evidence-based recommendations for selecting the appropriate tool for their specific research needs.

Algorithmic Approaches and Indexing Strategies

The fundamental differences between STAR and HISAT2 begin with their core algorithmic approaches to the spliced alignment problem. STAR utilizes a novel strategy based on maximal mappable prefixes (MMPs) and employs suffix arrays to rapidly identify splice junctions without relying on pre-existing annotation databases [27]. This method involves two primary steps: first, a seed-searching step that identifies MMPs from the beginning of each read, and second, a clustering/stitching/scoring step that combines these seeds into complete alignments across splice junctions. This approach allows STAR to detect novel splice sites de novo but requires significant memory resources to maintain the necessary data structures.

In contrast, HISAT2 employs a hierarchical indexing scheme based on the Ferragina-Manzini index (a derivation of the Burrows-Wheeler transform) that organizes the reference genome into a global whole-genome index and numerous small local indices [27]. This hierarchical approach allows HISAT2 to efficiently map reads to specific genomic regions with reduced memory overhead compared to STAR. HISAT2 builds upon its predecessors (TopHat2 and HISAT) by incorporating the ability to align reads across splice sites while simultaneously handling single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), making it particularly suited for studies involving genetic variation [36].

The indexing strategies directly impact practical implementation. STAR typically requires 30-38GB of RAM for the human genome, while HISAT2 operates efficiently with approximately 6.7GB for the same reference [36] [37]. This substantial difference in memory requirements can be a decisive factor for researchers working in resource-constrained environments or analyzing data from large-scale studies with multiple simultaneous alignment operations.

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

Comprehensive Comparison Metrics

Independent benchmarking studies have evaluated STAR and HISAT2 across multiple performance dimensions using standardized datasets and simulation approaches. These evaluations reveal a complex trade-space where neither tool dominates across all metrics, emphasizing the importance of selecting aligners based on specific research priorities.

Table 1: Base-Level and Junction-Level Alignment Accuracy

| Performance Metric | STAR | HISAT2 | Testing Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Base-Level Accuracy | >90% | ~85-90% | Arabidopsis thaliana with introduced SNPs [27] |

| Junction Base-Level Accuracy | ~75-80% | ~70-75% | Arabidopsis thaliana with introduced SNPs [27] |

| Exon Skipping Detection | 100% (all events detected) | Limited data | rLAS method with known splicing events [38] |

| Mapping Rate | Slightly lower | Slightly higher | Targeted RNA long-amplicon sequencing [38] |

| Splice Junction Discovery | Higher sensitivity for novel junctions | Good for annotated junctions | Various eukaryotic genomes [39] |

Table 2: Computational Resource Requirements

| Resource Metric | STAR | HISAT2 | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Memory Usage (Human Genome) | 30-38 GB | ~6.7 GB | Default settings [37] [36] |

| Alignment Speed | Faster with sufficient resources | Slower but more consistent | Speed advantages depend on available RAM [40] |

| Scalability | Requires high-memory nodes | Runs efficiently on standard hardware | Cloud optimization possible for both [40] |

| Index Size | Large (~30GB for human) | Moderate (~4.4GB for human) | Both benefit from SSD storage [36] |

Experimental Protocols in Benchmarking Studies

The performance data presented in this comparison are derived from rigorously designed benchmarking studies that employed standardized methodologies to ensure fair and reproducible evaluations:

Base-Level and Junction-Level Assessment Protocol: Researchers simulated RNA-seq reads from the Arabidopsis thaliana genome using Polyester, introducing annotated SNPs from The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR) at known positions to create ground truth data [27]. This approach allowed precise measurement of alignment accuracy at both base resolution and splice junction resolution. Each aligner was evaluated using default parameters, with performance quantified by the percentage of correctly mapped bases and correctly identified junction boundaries.

Targeted RNA Long-Amplicon Sequencing (rLAS) Protocol: This specialized evaluation focused on detecting known splicing events in patient-derived samples [38]. The experimental workflow involved: (1) targeted amplification of specific transcripts using the rLAS method, (2) deep sequencing of amplified regions, (3) alignment using both STAR and HISAT2 (with two mapping tools combined with four splicing detection tools), and (4) manual verification of splicing events using IGV visualization. This protocol provided validation using real biological samples with previously characterized splicing mutations.

Large-Scale Multi-Center Study Protocol: The Quartet project conducted the most extensive RNA-seq benchmarking to date, involving 45 laboratories using different experimental protocols and analysis pipelines [3]. The study employed well-characterized reference materials with spike-in controls to assess technical performance across multiple sites. Algorithms were evaluated based on signal-to-noise ratios, accuracy of absolute and relative gene expression measurements, and reliability in detecting subtle differential expression patterns.

Visualization of Alignment Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the core algorithmic differences between STAR and HISAT2, highlighting their distinct approaches to read alignment and splice junction detection:

Error Profiles and Systematic Artifacts

Recent research has revealed that both aligners can introduce specific types of systematic errors, particularly when dealing with repetitive genomic regions. A 2023 study demonstrated that both STAR and HISAT2 can generate "phantom" introns through erroneous spliced alignments between repeated sequences [39]. These artifacts occur when flanking sequences of putative introns show significant similarity, potentially leading to falsely spliced transcripts in downstream analyses.

The EASTR tool was developed specifically to address these systematic alignment errors and has been tested on outputs from both aligners. When applied to human brain RNA-seq data, EASTR removed 3.4% of HISAT2 and 2.7% of STAR spliced alignments on average, with the majority of these representing non-reference junctions [39]. The prevalence of these artifacts was significantly higher in rRNA-depleted libraries (6.4-8.0% of alignments flagged) compared to poly(A)-selected libraries (1.0-1.2% flagged), suggesting that library preparation method influences alignment accuracy.

These findings highlight the importance of considering error profiles when selecting an aligner, particularly for studies focusing on repetitive regions, transposable elements, or organisms with high repeat content. Post-alignment filtering tools like EASTR can significantly improve the reliability of downstream analyses by removing these systematic artifacts.

Table 3: Key Experimental Resources for RNA-seq Alignment Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in Alignment Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | Quartet Project RNA references, MAQC samples, ERCC spike-in controls | Provide ground truth for benchmarking alignment accuracy and quantifying technical variance [3] |

| Quality Control Tools | FastQC, fastp, Trim Galore, MultiQC | Assess read quality, adapter contamination, and generate comprehensive QC reports [41] [37] |

| Alignment Algorithms | STAR (2.7.10b+), HISAT2 (2.2.1+) | Perform core splice-aware alignment of RNA-seq reads to reference genomes [38] [40] |

| Reference Genomes | ENSEMBL, GENCODE, TAIR (Arabidopsis), UCSC | Provide standardized genome sequences and annotations for alignment [27] [3] |

| Error Detection Tools | EASTR, SAMtools, Qualimap | Identify and remove systematic alignment artifacts, validate mapping quality [39] |

| Downstream Analysis | featureCounts, RSEM, Salmon, StringTie2, DESeq2 | Quantify gene expression, assemble transcripts, perform differential expression [37] [39] |

| Computational Infrastructure | High-memory servers (STAR), Standard workstations (HISAT2), Cloud computing (AWS) | Provide necessary computational resources for alignment operations [36] [40] |

Best Practices and Implementation Recommendations

Based on the cumulative evidence from benchmarking studies, we recommend the following best practices for selecting and implementing splice-aware aligners:

When to prefer STAR: Select STAR for projects where detection of novel splice junctions and maximum alignment sensitivity are prioritized, and when sufficient computational resources (≥32GB RAM per process) are available. STAR is particularly well-suited for clinical RNA-seq applications where comprehensive junction discovery is critical, and for large-scale analyses where its faster alignment speed (with adequate resources) can significantly reduce processing time [40] [3]. The recent development of cloud-optimized STAR implementations further enhances its suitability for large-scale genomic initiatives.