Strategies for Overcoming PCR Amplification Bias in Low-Input RNA-Seq Libraries: A Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on understanding, mitigating, and validating solutions for PCR amplification bias in low RNA sequencing libraries.

Strategies for Overcoming PCR Amplification Bias in Low-Input RNA-Seq Libraries: A Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on understanding, mitigating, and validating solutions for PCR amplification bias in low RNA sequencing libraries. We explore the foundational sources of bias introduced during library preparation, review current methodological advancements and optimized protocols for low-input samples, offer systematic troubleshooting and optimization strategies, and compare validation techniques to assess data fidelity. The synthesis of these approaches aims to equip scientists with practical knowledge to generate more accurate and reproducible transcriptomic data from precious samples, which is critical for advancing biomedical discovery and clinical applications.

Understanding the Root Causes: What is PCR Amplification Bias and Why is it Acute in Low RNA Libraries?

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My qPCR standard curve shows poor efficiency or high variability between replicates. What could be the cause? A: This is a classic sign of PCR amplification bias. Non-uniform amplification can arise from several factors:

- Inhibitors in Sample: Residual phenol, ethanol, salts, or heparin from RNA isolation can inhibit polymerase activity. Perform an additional clean-up step or dilute the template.

- Primer-Dimer Formation: This consumes reagents and competes with target amplification, skewing quantification. Use a melting curve analysis to confirm. Redesign primers with stricter criteria (e.g., avoid 3' complementarity) and optimize annealing temperature.

- Secondary Structure in Template: GC-rich regions or stem-loops can prevent efficient primer binding and elongation. Use a PCR additive like DMSO, betaine, or a specialized high-GC buffer. Consider using a polymerase blend optimized for complex templates.

- Low Template Concentration: At very low input levels, stochastic sampling of molecules becomes a significant variable. Pre-amplify your library or use digital PCR (dPCR) for absolute quantification at low copy numbers.

Q2: After sequencing my low-input RNA-seq library, I observe uneven gene body coverage and poor correlation between technical replicates. How is PCR bias involved? A: PCR amplification bias is a major contributor to these issues in low-input workflows. During library preparation, the PCR step can preferentially amplify:

- Shorter fragments, leading to 3' bias in coverage.

- Fragments with lower GC content, under-representing GC-rich regions.

- Specific sequences due to primer binding efficiency differences. This non-uniform amplification distorts the true molecular abundance, compromising differential expression analysis. Mitigation strategies include limiting PCR cycle number, using unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), and employing PCR enzymes with demonstrated low bias.

Q3: How can I experimentally measure the degree of PCR bias in my library prep protocol? A: A controlled spike-in experiment is the gold standard. Use an external, non-competitive control like the ERCC (External RNA Controls Consortium) Spike-In Mix. These are synthetic RNA molecules at known, defined concentrations. After preparing and sequencing your library alongside the spike-ins, compare the observed read counts to the expected input abundances. Deviation from the expected ratio quantifies the protocol's technical bias, including PCR amplification bias.

Q4: My digital PCR data shows a different quantification result than my qPCR data for the same low-abundance target. Which should I trust? A: For low-abundance targets, digital PCR (dPCR) is generally more accurate and less susceptible to amplification bias. qPCR relies on amplification efficiency, which can be skewed by inhibitors or template quality, especially at low concentrations. dPCR uses endpoint partitioning to count individual molecules, making it less dependent on amplification efficiency. The discrepancy likely highlights the quantification error introduced by non-uniform amplification in your qPCR assay.

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating PCR Bias with ERCC Spike-Ins

Objective: To quantify the amplification bias introduced during library preparation for low-input RNA sequencing.

Materials:

- Low-input RNA sample

- ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat #4456740)

- Library preparation kit (e.g., SMART-Seq v4, Tagmentation-based)

- High-fidelity, low-bias PCR enzyme (e.g., KAPA HiFi, Q5)

- Bioanalyzer/TapeStation

- Sequencing platform

Methodology:

- Spike-in Addition: Dilute the ERCC mix per manufacturer's instructions. Add a small, defined volume (e.g., 1 µl of a 1:100,000 dilution) to your low-input RNA sample before any reverse transcription or amplification step. The ERCC molecules span a wide range of lengths and GC content.

- Library Preparation: Proceed with your standard low-input RNA-seq library protocol. Crucially, limit the number of PCR cycles (e.g., 10-14 cycles) to minimize bias amplification.

- Quality Control: Assess library fragment size distribution using a Bioanalyzer.

- Sequencing: Pool and sequence libraries on an appropriate platform to achieve sufficient depth for spike-in detection.

- Data Analysis:

- Map reads to a combined reference genome (target organism + ERCC sequences).

- Extract read counts for each ERCC spike-in transcript.

- Plot Observed Read Count (log2) vs. Expected Input Concentration (log2).

- Calculate the correlation coefficient (R²) and slope. An ideal, unbiased amplification would yield a slope of 1 and high R². Deviations indicate bias.

Expected Data Table (Example):

| ERCC Spike-In ID | Expected Concentration (attomoles/µl) | Log2(Expected) | Observed Read Count | Log2(Observed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERCC-00116 | 3,000 | 11.55 | 8,500 | 13.05 |

| ERCC-00108 | 1,000 | 9.97 | 2,900 | 11.50 |

| ERCC-00130 | 250 | 7.97 | 480 | 8.91 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Analysis Result | Slope: 0.85 | R²: 0.89 |

Visualizations

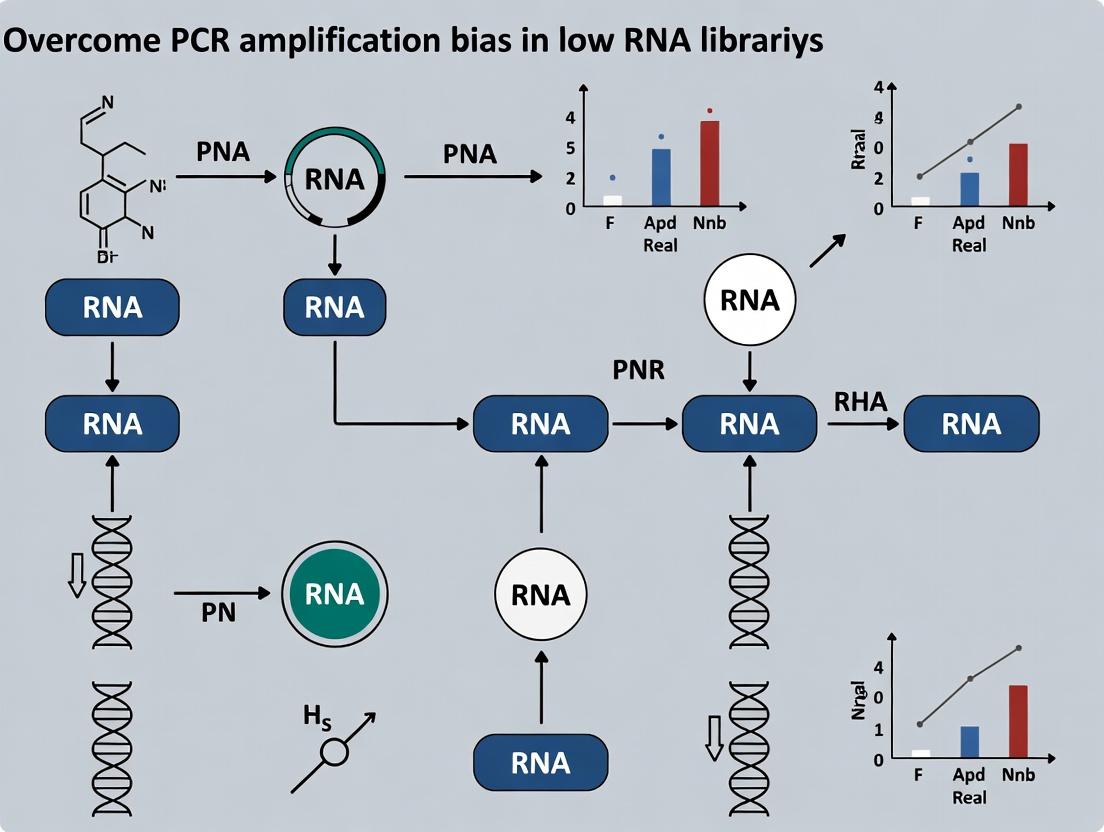

Diagram 1: PCR Amplification Bias in Library Prep Workflow

Diagram 2: Strategy to Overcome PCR Bias for Quantification

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Overcoming PCR Bias |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity, Low-Bias Polymerase (e.g., Q5, KAPA HiFi) | Enzymes engineered for superior accuracy and uniform amplification efficiency across diverse sequences (GC-rich, secondary structure), minimizing preferential amplification. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide tags added to each original molecule before PCR. Post-sequencing, PCR duplicates are identified and collapsed by UMI, removing amplification noise. |

| ERCC ExFold RNA Spike-In Mixes | Defined synthetic RNA controls at known concentrations. Added to samples pre-amplification to track and correct for technical bias, enabling normalization. |

| PCR Additives (DMSO, Betaine) | Reduce secondary structure in template DNA/RNA, promoting more consistent primer binding and elongation, especially for GC-rich targets. |

| Methylated Adapter- & dNTP-Compatible Enzymes | For tagmentation-based (e.g., ATAC-seq) or bisulfite-seq libraries, these enzymes prevent over-amplification of adapter-dimers and handle modified nucleotides. |

| Digital PCR (dPCR) Master Mix | Enables absolute quantification without a standard curve by partitioning reactions. Less affected by amplification efficiency differences, crucial for validating low-abundance targets. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My single-cell RNA-seq data shows high technical variability and dropout events. Is this due to amplification bias, and how can I confirm it? A: Yes, this is a classic symptom. Limited starting RNA requires extensive PCR amplification, which is non-linear and sequence-dependent. To confirm, spike-in controls (e.g., ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix) should be used. A strong correlation between the input spike-in molecule count and the final read count indicates good linearity. A high variance in spike-in recovery or a significant 3' bias in alignment metrics suggests amplification bias. Check your pre-amplification cDNA yield with a fluorometer; low yield often precedes high bias.

Q2: I am observing significant 3' bias in my low-input RNA-seq libraries. Which steps in my protocol are most likely the cause? A: 3' bias is primarily introduced during reverse transcription and template switching. In low-input protocols, these steps are less efficient, causing an over-representation of 3' ends. The key culprits are:

- Reverse Transcription Primer: An imperfectly designed or degraded oligo(dT) primer.

- Template Switching Oligo (TSO): Inefficient TSO activity during second-strand synthesis, common in SMART-seq-based protocols.

- PCR Amplification: Later cycles of PCR preferentially amplify shorter fragments (from the 3' end).

Q3: How can I mitigate amplification bias when I have sub-nanogram total RNA? A: Implement a combination of wet-lab and computational strategies:

- Use Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): Integrate UMIs during reverse transcription to tag each original molecule. Post-sequencing, UMI deduplication collapses PCR duplicates, revealing true transcript counts.

- Optimize PCR Cycles: Use the minimum number of PCR cycles necessary for library construction. Perform a qPCR side-reaction to determine the optimal cycle number before the main amplification.

- Employ a High-Fidelity, Bias-Reduced Polymerase: Use polymerases engineered for uniform amplification across GC-rich and GC-poor regions.

- Apply Computational Correction: Use tools like

UMI-toolsfor deduplication andsctransformorDESeq2(with spike-ins) for normalization, which can model and correct for technical noise.

Q4: My negative controls (no-template) are producing detectable libraries after amplification. What should I do? A: This indicates contamination or non-specific amplification.

- Decontaminate: Use a UV workstation, fresh reagents, and dedicated pipettes for pre-amplification steps.

- Optimize Enzyme Mixes: Ensure your reverse transcription and PCR mixes contain the correct inhibitors to prevent polymerase-mediated template-independent synthesis.

- Implement Strict QC: Use a bioanalyzer or tapestation. A smeared profile in the negative control is a clear red flag. Re-prepare all reagents if contamination is suspected.

Key Experimental Protocol: UMI-Based Low-Input RNA-seq with Spike-Ins

Objective: To generate a strand-specific RNA-seq library from 10-100pg of total RNA while controlling for amplification bias. Reagents: See "Research Reagent Solutions" table below. Workflow:

- RNA Isolation & QC: Use a column-based or magnetic bead-based kit. Assess degradation with a Bioanalyzer RNA Pico Chip. RIN > 7 is critical.

- Spike-in Addition: Dilute ERCC ExFold RNA Spike-In Mix 1:100,000 and add 1µl to your RNA sample.

- First-Strand Synthesis: In a single tube, combine RNA, dNTPs, and a primer containing an anchored oligo(dT) sequence, a UMI (8-10 random nucleotides), and a universal handle. Heat, then add reverse transcriptase and template-switching oligo (TSO).

- cDNA Amplification: Perform limited-cycle (10-14 cycles) PCR using a primer complementary to the universal handle and the TSO sequence. Use a high-fidelity, low-bias polymerase.

- Library Construction: Fragment amplified cDNA via sonication or enzymatic fragmentation. Perform end-repair, A-tailing, and ligation of indexed adapters.

- Final Library Amplification: Perform 8-10 cycles of PCR with primers containing P5 and P7 flow cell binding sites.

- QC & Sequencing: Quantify library with qPCR, assess size distribution on a Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity DNA chip. Sequence on an appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq, 2x150bp recommended).

Table 1: Impact of Input RNA and PCR Cycles on Bias Metrics

| Input RNA Amount | PCR Cycles (Post-RT) | % Reads Aligned to 3' UTR* | Spike-in Recovery (R²)* | Gene Detection (No. of Genes)* | Recommended Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ng | 10 | 15-25% | 0.98-0.99 | 10,000-12,000 | Standard bulk RNA-seq |

| 100 pg | 14 | 30-50% | 0.90-0.95 | 8,000-10,000 | Low-input bulk RNA-seq |

| 10 pg (Single Cell) | 18 | 50-70% | 0.85-0.92 | 5,000-7,000 | High-quality scRNA-seq |

| 1 pg | 22 | >70% | <0.80 | 1,000-3,000 | Challenging, high bias |

*Representative values from optimized protocols. % 3' UTR alignment and Spike-in R² are key bias indicators.

Table 2: Comparison of Amplification Kits for Low-Input RNA-seq

| Kit/Technology | Principle | Minimum Input | UMI Compatible? | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMART-seq2 | Template Switching | 1 cell | No (standard) | Full-length coverage, high sensitivity | High 3' bias, no inherent UMIs |

| 10x Genomics Chromium | Gel Bead-in-emulsion | 1 cell | Yes | High-throughput, cell hashing | Only 3' ends, platform-dependent |

| CEL-seq2 | In Vitro Transcription | 1 cell | Yes | Low amplification noise, strand-specific | Complex protocol, lower sensitivity |

| Quartz-seq2 | Two-step Template Switch | 1 cell | Yes | Extremely low contamination risk | Technically challenging protocol |

Visualizations

Title: Low-Input RNA-seq with UMI & Spike-in Workflow

Title: The Amplification Bottleneck Causes Multiple Biases

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in Low-Input RNA-seq | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| ERCC ExFold RNA Spike-In Mix | Artificial RNA molecules at known concentrations. Used to track technical variance, calculate recovery rates, and normalize for amplification bias. | Dilute accurately; add at the very first step of the protocol. |

| UMI Oligo(dT) Primers | Primers containing a cell barcode, a unique molecular identifier (UMI), and an oligo(dT) sequence. Tags each original mRNA molecule to allow computational removal of PCR duplicates. | Ensure random nucleotide region (UMI) is sufficiently long (8-10nt) to avoid collisions. |

| Template Switching Oligo (TSO) | A modified oligonucleotide that allows the reverse transcriptase to add additional sequence to the 5' end of the first cDNA strand. Enables amplification of full-length cDNA. | Critical for SMART-seq protocols. Efficiency drops with low input, causing 3' bias. |

| High-Fidelity, Low-Bias DNA Polymerase | Enzymes engineered for uniform amplification across sequences with varying GC content. Reduces sequence-dependent representation bias during the PCR steps. | Examples include KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix and Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase. |

| RNase Inhibitor | Protects the already minimal RNA template from degradation during sample preparation and reverse transcription. | Use a high-concentration, broad-spectrum inhibitor. |

| Magnetic Beads (SPRI) | Used for size selection and clean-up between enzymatic steps. Efficiently recovers low amounts of nucleic acids. | Maintain a consistent bead-to-sample ratio. Over-drying beads can decrease elution efficiency. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting PCR Amplification in Low RNA Libraries

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our qPCR amplification efficiency is low and inconsistent across targets when using low-input RNA libraries. What are the primary biophysical factors we should investigate first? A1: The three primary biophysical drivers to investigate are:

- Primer GC Content: Aim for 40-60%. GC content outside this range can lead to inefficient binding (too low) or non-specific, high-temperature annealing (too high).

- Amplicon Secondary Structure: Self-complementarity in the template RNA/DNA can form hairpins or G-quadruplexes, blocking polymerase progression.

- Primer Dimer Formation: Primer sequences with 3'-end complementarity can prime off each other, consuming reagents and generating false amplicons.

Q2: How can we accurately predict and mitigate secondary structure issues in our target amplicons? A2: Use in silico prediction tools (e.g., Mfold, NUPACK) at your specific annealing/extension temperature. Experimentally, mitigate using:

- PCR Additives: Include DMSO (1-5%), betaine (0.5-1.5 M), or formamide (1-3%) to destabilize secondary structures.

- Thermal Profile Adjustments: Implement a two-step PCR or a higher-temperature extension (e.g., 68-72°C) to help polymerase read through structures.

- Probe-Based Detection: Switch to hydrolysis (TaqMan) or hybridization probes to increase specificity over intercalating dyes.

Q3: We observe primer dimer artifacts in our post-amplification melt curves. How can we redesign primers to improve efficiency? A3: Follow these primer design rules:

- Check 3'-End Complementarity: Ensure no more than 2-3 complementary bases at the 3' ends of primer pairs.

- Optimize Length: Keep primers 18-25 nucleotides long.

- Modify Tm: Calculate melting temperatures (Tm) using a nearest-neighbor method (e.g., SantaLucia algorithm). Aim for a Tm difference of ≤2°C between forward and reverse primers.

- Validate in silico: Use tools like Primer-BLAST to check for off-target binding and dimerization potential.

Q4: For low RNA library amplification, should we prioritize a one-step or two-step RT-qPCR protocol to minimize bias? A4: A two-step protocol (reverse transcription first, then qPCR) is generally recommended for reducing amplification bias in low RNA libraries. It allows for:

- Independent optimization of the RT and PCR steps.

- The use of gene-specific priming for cDNA synthesis, increasing target specificity.

- Archiving of cDNA for multiple qPCR assays.

- More consistent results when amplifying low-abundance targets, as the efficiency of each step can be separately tuned.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: High Cq Values and Failed Amplification of High-GC Targets

- Symptoms: Delayed quantification cycles (Cq > 35), plateau at low fluorescence, or complete amplification failure.

- Likely Cause: High GC content (>65%) leading to stable secondary structures and incomplete denaturation.

- Solution Pathway:

- Verify Amplicon: Check sequence GC% and predicted structure.

- Modify Buffer: Supplement with 1-3% DMSO or 1 M betaine.

- Optimize Cycling: Increase denaturation temperature to 98°C, lengthen denaturation time to 20-30 seconds, and use a two-step protocol (combine annealing/extension at 68-72°C).

- Consider Enzyme: Switch to a polymerase blend specifically engineered for high-GC content templates.

Issue: Variable Amplification Efficiency Between Replicates in Low RNA Samples

- Symptoms: High standard deviation in Cq values between technical replicates, leading to unreliable quantification.

- Likely Cause: Stochastic sampling effects due to very low starting template copies, compounded by inefficient primer binding or secondary structure.

- Solution Pathway:

- Increase Replicates: Perform a minimum of 6-8 technical replicates per sample.

- Use Digital PCR (dPCR): If available, transition to dPCR for absolute quantification, as it is less susceptible to amplification efficiency biases.

- Enhance Specificity: Redesign primers to optimal specs (see Q3) and use a hot-start polymerase to prevent non-specific activity during setup.

- Pre-Amplification: Perform limited-cycle (5-10 cycles) target-specific pre-amplification to increase template mass before qPCR, using careful normalization.

Table 1: Impact of GC Content on PCR Efficiency

| GC Content Range | Typical Amplification Efficiency | Key Challenges | Recommended Additives |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 40% | Variable, often reduced | Low Tm, non-specific binding | MgCl₂ (up to 4.5 mM) |

| 40% - 60% | Optimal (90-105%) | Minimal | None required |

| 60% - 70% | Reduced (70-90%) | Secondary structure, incomplete denaturation | DMSO (1-3%), Betaine (1 M) |

| > 70% | Highly variable, often fails | Extreme secondary structure, high Tm | DMSO (3-5%), Formamide (1-3%), 7-deaza-dGTP |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Secondary Structure & Primer Dimer Artifacts

| Symptom | Diagnostic Tool | Primary Solution | Alternative Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broad or multi-peak melt curve | Post-PCR melt curve analysis | Redesign primer to avoid self-complementarity | Use PCR additives (DMSO, betaine) |

| Low Tm peak (~65-75°C) | Melt curve or gel electrophoresis | Check for 3' primer complementarity; use hot-start enzyme | Increase annealing temperature |

| Amplification in NTC (No Template Control) | Melt curve & gel electrophoresis | Redesign primers; optimize Mg²⁺ concentration | Use touchdown PCR |

| Reaction plateau at low RFU | Amplification plot | Increase extension temperature/time; use polymerase enhancers | Redesign amplicon to shorter length |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Silico Analysis of Primer and Amplicon Biophysical Properties

- Objective: Predict secondary structure and dimer formation to guide primer design.

- Steps:

- Input your candidate primer sequences and target amplicon sequence into multiple tools.

- For Secondary Structure: Use Mfold (http://www.unafold.org/mfold/applications/dna-folding-form.php). Set temperature to your planned annealing/extension temp (e.g., 60°C, 72°C). Analyze the resulting diagrams for stable hairpins within the amplicon, particularly at the 3' ends.

- For Primer Dimers: Use OligoAnalyzer Tool (IDT) or NUPACK. Analyze both self-dimers and heterodimers for the primer pair. Pay special attention to ΔG values more negative than -5 kcal/mol and complementarity at the 3' ends.

- Select primer pairs with no predicted strong secondary structures at the 3' end and minimal dimerization potential.

Protocol 2: Empirical Optimization of PCR Additives for Difficult Amplicons

- Objective: Determine the optimal enhancer cocktail for amplifying a high-GC or structured target from a low RNA library.

- Reagents: Template cDNA (from low RNA input), primer pair, standard PCR master mix, DMSO, betaine, formamide, molecular grade water.

- Method:

- Prepare a master mix containing all components except additives.

- Aliquot the master mix into 8 tubes.

- Spike the tubes with the following additive combinations (final concentrations):

- Tube 1: Control (no additive)

- Tube 2: 1% DMSO

- Tube 3: 3% DMSO

- Tube 4: 0.5 M Betaine

- Tube 5: 1.0 M Betaine

- Tube 6: 1% DMSO + 0.5 M Betaine

- Tube 7: 1.5% Formamide

- Tube 8: 1% DMSO + 1.0 M Betaine

- Run qPCR with a standardized cycling protocol.

- Compare Cq values, amplification efficiency (from standard curve), and endpoint fluorescence.

- Confirm specificity via melt curve analysis. The condition yielding the lowest Cq, efficiency closest to 100%, and a single clean melt peak is optimal.

Visualizations

Troubleshooting PCR Bias in Low RNA Libraries

Optimized Workflow for Low RNA Library PCR

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Overcoming PCR Bias |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Hot-Start Polymerase | Reduces non-specific amplification and primer-dimer artifacts during reaction setup, crucial for low-template reactions. |

| PCR Enhancers (DMSO, Betaine) | Destabilizes secondary nucleic acid structures, enabling more efficient amplification of high-GC or structured targets. |

| Molecular Biology Grade BSA | Stabilizes the polymerase, neutralizes inhibitors potentially co-purified with low-concentration RNA, and improves reaction consistency. |

| RNase Inhibitor (for one-step RT-qPCR) | Protects fragile, low-abundance RNA templates from degradation during reverse transcription setup. |

| dNTP Mix (with 7-deaza-dGTP) | Alternative nucleotide that reduces base stacking, aiding in the amplification of extreme GC-rich templates. |

| Target-Specific Reverse Transcription Primers | Increases cDNA synthesis specificity and yield for genes of interest, improving downstream PCR detection limits. |

| Digital PCR (dPCR) Master Mix | Enables absolute quantification without a standard curve, mitigating the impact of amplification efficiency variations on quantitation. |

| Probe-Based qPCR Assays (e.g., TaqMan) | Provides higher specificity than intercalating dyes, reducing false signals from primer dimers or non-specific amplicons. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Low RNA-Seq Library Preparation

Thesis Context: This support center provides targeted solutions for mitigating cumulative bias in library preparation for low-input and single-cell RNA sequencing. The guidance is framed within the critical need to achieve accurate representation of the original transcriptome in downstream PCR-amplified libraries.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ Category 1: Reverse Transcription (RT) Bias

- Q1: My library shows severe 3' bias and underrepresentation of long transcripts. What is the cause?

- A: This is a hallmark of bias introduced during reverse transcription. Incomplete processivity of reverse transcriptase, especially with fragmented or degraded RNA (common in low-input samples), leads to truncated cDNA. These 5'-incomplete molecules are then lost in subsequent adapter ligation steps. RNA secondary structure can also cause premature termination.

- Q2: How can I reduce RT-induced bias?

- A: Implement the following:

- Use Thermostable Reverse Transcriptases: Enzymes like TGIRT or MarathonRT function at higher temperatures (55-60°C), reducing RNA secondary structure.

- Optimize Reaction Temperature & Time: A longer extension time (e.g., 90 minutes) at an elevated temperature can improve processivity.

- Include RNA Denaturants: Add reagents like betaine or sorbitol to the RT reaction to destabilize GC-rich secondary structures.

- Use Template-Switching (SMART) Protocols: This approach specifically captures the complete 5' end of the transcript during RT, mitigating 3' bias.

- A: Implement the following:

FAQ Category 2: Adapter Ligation Bias

- Q3: My library yield is low, and QC shows a broad size distribution. Could adapter ligation be the issue?

- A: Yes. Inefficient or biased ligation compounds prior biases. Key factors are:

- CDNA End Integrity: Truncated cDNA from RT has incompatible ends for ligation.

- Adapter Dimer Formation: Excess unblocked adapters ligate to each other, outcompeting genuine cDNA ligation and consuming sequencing capacity.

- Sequence-Dependent Ligation Efficiency: T4 DNA Ligase can have sequence preferences.

- A: Yes. Inefficient or biased ligation compounds prior biases. Key factors are:

- Q4: What steps improve adapter ligation efficiency and fairness?

- A:

- Repair cDNA Ends: Use a combination of polymerase and exonuclease to generate blunt, 5'-phosphorylated ends universally.

- Use Ligation-Free (Tagmentation) Methods: Protocols like Nextera use a transposase to fragment and tag DNA simultaneously, bypassing end-ligation bias.

- Employ Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): While not reducing bias, UMIs allow bioinformatic correction of PCR duplication bias, deconvoluting the final read count.

- Optimize Adapter-to-Insert Ratio: A precise molar ratio (e.g., 10:1) minimizes adapter dimer formation. Use double-stranded, truncated adapters with non-ligatable ends.

- A:

FAQ Category 3: PCR Amplification Bias

- Q5: Despite optimizing RT and ligation, my final library shows uneven gene coverage and duplicate reads. Why?

- A: This is PCR amplification bias, which exponentially compounds earlier biases. Molecules that are longer, have high GC content, or were more efficiently reverse-transcribed and ligated amplify more efficiently. Early-cycle stochasticity also leads to dominance of certain molecules.

- Q6: How do I minimize PCR bias in the final amplification?

- A:

- Use High-Fidelity, Low-Bias Polymerases: Enzymes like KAPA HiFi or Q5 are engineered for even amplification across diverse sequences.

- Limit PCR Cycles: Use the minimum number of cycles necessary for library detection. Perform a qPCR side-reaction to determine the optimal cycle number (Cq) for the main reaction.

- Incorporate UMIs: As stated, UMIs are essential for identifying and collapsing PCR duplicates bioinformatically.

- A:

Table 1: Impact of Reverse Transcriptase Choice on Coverage Uniformity

| Reverse Transcriptase Type | Optimal Temperature | Relative 5' Coverage* | Relative Full-Length Yield* | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type M-MLV | 37°C | 1.0 (Baseline) | 1.0 (Baseline) | Standard input |

| M-MLV RNase H- | 42°C | 1.8 | 2.1 | Moderate quality/degraded RNA |

| TGIRT-III | 60°C | 3.5 | 4.7 | Low-input, high-structure RNA |

Hypothetical values for illustration, based on common literature reports.

Table 2: Effect of PCR Cycle Number on Duplication Rates & Bias

| Number of PCR Cycles | Estimated Duplicate Rate* | Effective Library Complexity* | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 cycles | 5-10% | High | Ideal, often not feasible for low-input |

| 15 cycles | 15-25% | Moderate | Target for optimized workflows |

| 20+ cycles | 40-70%+ | Low | Leads to severe skewing; use UMIs |

Rates are illustrative and highly dependent on starting material.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Low-Bias, Template-Switching RT for Low-Input RNA

- Denature RNA: Combine 1-10 ng total RNA (or single-cell lysate) with 1µM Template-Switch Oligo (TSO) and dNTPs. Incubate at 72°C for 3 minutes, then hold at 4°C.

- Reverse Transcription: Add reverse transcriptase (e.g., Maxima H-), RNase inhibitor, and buffer. Use a thermocycler program: 42°C for 90 min, 10 cycles of (50°C for 2 min, 42°C for 2 min), 70°C for 15 min.

- cDNA Cleanup: Purify cDNA using SPRI beads at a 1.8x ratio. Elute in nuclease-free water.

Protocol 2: qPCR-Based Determination of Optimal Library Amplification Cycles

- Prepare Master Mix: Create a PCR mix containing your final library ligation product, high-fidelity polymerase, and SYBR Green dye.

- Run qPCR: Use a program: 98°C for 45s; 20-25 cycles of (98°C for 15s, 60°C for 30s, 72°C for 30s) with plate read.

- Calculate Cq: Determine the quantification cycle (Cq) where fluorescence crosses the threshold.

- Amplify Main Library: Perform the preparative PCR amplification of the library using Cq - 1 cycles.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Cascade of NGS Library Prep Bias

Diagram 2: Bias Mitigation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Low-Bias Library Prep

| Reagent | Function & Rationale | Example (for illustration) |

|---|---|---|

| Thermostable Group II Intron Reverse Transcriptase (TGIRT) | Operates at 60°C, minimizing RNA secondary structure, improving processivity and yield of full-length cDNA. | TGIRT-III Enzyme |

| Template-Switch Oligo (TSO) & RT Primer | Enables template-switching activity, ensuring capture of the complete 5' end of transcripts during RT, countering 3' bias. | SMART-Seq v4 Oligos |

| High-Fidelity, Low-Bias PCR Polymerase | Exhibits uniform amplification efficiency across different sequences and GC contents, reducing skew during library amplification. | KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences added before PCR; allow bioinformatic identification and correction of PCR duplicates. | TruSeq UMI Adapters |

| Magnetic SPRI Beads | Enable size selection and cleanup of nucleic acids without column losses; critical for maintaining yield from low-input samples. | AMPure XP Beads |

| Dual-Indexed Adapters | Allow multiplexing of samples. Using unique dual indices reduces index hopping errors and improves demultiplexing accuracy. | IDT for Illumina UD Indexes |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why do my low-input RNA-Seq results show inflated expression of high-GC content transcripts, and how can I correct this?

- Issue: PCR amplification during library preparation preferentially enriches fragments with optimal GC content, leading to skewed abundance measurements. This is particularly severe in low-input samples where more amplification cycles are required.

- Solution: Implement a post-sequencing computational correction using tools like

gcContentorcqn(Conditional Quantile Normalization). Additionally, validate with spike-in controls (e.g., ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix) that cover a range of GC contents. Consider switching to PCR-free or low-cycle amplification protocols if input amounts allow.

FAQ 2: My biomarker candidate list from FFPE samples differs drastically from matched frozen tissue. Is this due to amplification bias?

- Likely Cause: Yes. Formalin fixation causes RNA fragmentation and base modifications, which alter priming efficiency and introduce sequence-specific amplification bias. This compounds the standard PCR bias present in all low-RNA libraries.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Pre-sequencing: Use random hexamers for priming and repair RNA with agents like Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) to mitigate formalin damage.

- During Analysis: Apply deconvolution algorithms (e.g.,

Deblur,UMI-tools) that utilize Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) to distinguish biologically unique molecules from PCR duplicates. - Validation: Always confirm biomarkers using an orthogonal, amplification-free method (e.g., RNAscope, Nanostring) on the same sample set.

FAQ 3: How do I determine if my differential expression (DE) results are artifacts of amplification bias rather than true biology?

- Diagnosis: Correlate the log2 fold-change of your DE genes with their transcript GC content or predicted amplification efficiency. A significant correlation suggests bias.

- Protocol for Diagnosis:

- Calculate per-transcript GC% from your reference genome.

- Perform a linear regression of DE log2 fold-change against GC%.

- A statistically significant slope (p < 0.05) indicates GC bias.

- Solution: Re-analyze data using bias-aware DE tools like

Alpineorswish(which uses inferential replicates and is robust to amplification bias).

FAQ 4: What is the optimal method for normalizing low-input RNA-Seq data to account for amplification efficiency differences?

- Answer: Standard normalization (e.g., TPM, median-of-ratios) fails here. Use normalization methods that explicitly model technical factors.

- Recommended Workflow:

- Spike-in Normalization: Add known quantities of exogenous spike-in RNAs before amplification. Use their counts to normalize for global differences in amplification yield.

- RUVg Normalization: Use the

RUVgfunction in theRUVSeqpackage with either spike-ins or in silico empirical control genes (e.g., housekeeping genes stable across conditions) to remove unwanted variation.

Table 1: Impact of PCR Cycle Number on Duplication Rates and Bias in Low-Input Libraries

| Input RNA (pg) | PCR Cycles | % Duplicate Reads | GC Bias Coefficient (R²) | Detected Genes (CV < 20%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 | 12 | 15-25% | 0.08 | ~12,000 |

| 100 | 18 | 40-60% | 0.35 | ~9,500 |

| 10 | 22 | 70-85% | 0.52 | ~6,000 |

Data synthesized from , and current protocols. CV = Coefficient of Variation.

Table 2: Comparison of Bias Correction Methods for Differential Expression Analysis

| Method | Principle | Requires UMIs | Requires Spike-ins | Computational Cost | Effectiveness (Reduction in GC Correlation) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UMI Deduplication | Physical molecule counting | Yes | No | Low | High (>70%) |

| Conditional Quantile Normalization (CQN) | Statistical modeling of GC & length | No | No | Medium | Moderate (40-50%) |

| Spike-in Calibration | External reference scaling | No | Yes | Low | High for global shifts (>60%) |

| Alpine | Probabilistic modeling of amplification efficiency | No | No | High | Very High (>80%) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: UMI-Based Library Preparation for Low-Input RNA to Control Amplification Bias

- Objective: To accurately count original RNA molecules and eliminate quantitative noise from differential PCR amplification.

- Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" below.

- Steps:

- Reverse Transcription: Use a template-switching oligo (TSO) containing a unique molecular identifier (UMI) and adapter sequence. This tags each cDNA molecule with a unique random barcode.

- cDNA Amplification: Perform limited-cycle PCR (10-14 cycles) using primers compatible with your sequencing platform.

- Library Purification: Clean up the PCR product using a double-sided bead-based purification (e.g., 0.6x followed by 1.0x SPRI ratio) to remove primer dimers and short fragments.

- Sequencing: Sequence on a platform providing sufficient read depth to account for molecule tagging.

- Bioinformatics Processing: Use

UMI-toolsorzUMIspipeline to group reads by their UMI and genomic location, collapsing PCR duplicates into a single, accurate count.

Protocol: Validating Amplification Bias with Synthetic Spike-Ins

- Objective: To quantify and correct for sequence-specific amplification efficiency in your experimental setup.

- Steps:

- Spike-in Addition: Prior to any amplification, add a commercially available spike-in mix (e.g., ERCC, SIRV) containing known concentrations of diverse RNA sequences to your lysate.

- Proceed with Standard Protocol: Continue with your standard RNA-Seq library prep and sequencing.

- Analysis:

- Map reads to a combined reference (study genome + spike-in sequences).

- Plot observed vs. expected abundance for each spike-in transcript.

- Fit a model (e.g., loess regression) relating log2(observed/expected) to transcript GC content. This model defines your system's amplification bias.

- Apply this model to correct the counts of your endogenous genes.

Diagrams

Title: UMI Workflow to Counteract PCR Bias

Title: Downstream Impacts of Uncorrected Bias

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Bias Mitigation | Example Product/Brand |

|---|---|---|

| UMI Adapter Kits | Incorporates unique barcodes during cDNA synthesis to track original molecules. | SMART-Seq v4 Ultra Low Input Kit, Takara Bio |

| ERCC/SIRV Spike-In Mixes | Exogenous RNA controls with known concentration to calibrate and model amplification efficiency. | ERCC ExFold RNA Spike-In Mix (Thermo Fisher) |

| Template Switching Reverse Transcriptase | Enables efficient incorporation of UMI adapters during first-strand synthesis. | Maxima H Minus Reverse Transcriptase |

| High-Fidelity, Bias-Reduced Polymerase | PCR enzyme with uniform amplification across varying GC content. | KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix, Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase |

| Dual-Size Selection SPRI Beads | For precise library fragment purification, removing primer dimers that consume amplification yield. | AMPure XP Beads (Beckman Coulter) |

| PCR Duplicate Removal Software | Bioinformatics tools to process UMI data and derive accurate molecular counts. | UMI-tools, zUMIs, fgbio |

Modern Protocols and Reagents: Best Practices for Low-Input RNA Library Construction

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: My low-input RNA-seq library shows uneven coverage and high dropout rates after PCR amplification. What could be the cause and how can I mitigate this?

- Answer: This is a classic symptom of PCR amplification bias, which is exacerbated with low-input or low-quality RNA templates. Stochastic sampling of molecules early in the PCR cycle leads to inconsistent and non-linear amplification. To mitigate this:

- Minimize PCR Cycles: Use the minimum number of PCR cycles required for library generation (typically 8-12 cycles for low-input).

- Use a High-Fidelity Polymerase: Enzymes like KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix are engineered for high accuracy and superior performance on difficult templates, providing more uniform coverage.

- Optimize Input Quality: Use rigorous QC (e.g., Bioanalyzer) to ensure starting RNA/RTA is not degraded.

- Include Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): Incorporate UMIs during reverse transcription to bioinformatically correct for amplification duplicates.

FAQ 2: I am observing a high error rate in my final NGS data, specifically transitions/transversions. Could my polymerase choice be a factor?

- Answer: Yes, the intrinsic error rate (mutation frequency) of the polymerase directly impacts sequencing accuracy. Standard Taq polymerases lack proofreading (3'→5' exonuclease) activity, leading to higher error rates (~1 x 10⁻⁴ to 1 x 10⁻⁵). High-fidelity enzymes like KAPA HiFi, Q5, and Phusion contain proofreading activity, reducing error rates by 10-100 fold. See Table 1 for comparative data.

FAQ 3: When amplifying GC-rich regions from my cDNA library, I get poor yield or complete dropout. Which polymerase should I select?

- Answer: GC-rich regions are challenging due to secondary structure and high melting temperatures. You require a polymerase blend or engineered enzyme with strong processivity and stability.

- Recommendation: Use a specialized high-fidelity polymerase like KAPA HiFi, which contains a proprietary enzyme blend optimized for robust amplification across diverse GC contents. Supplement with GC enhancer buffers or additives like DMSO (typically at 3-5%) if necessary, but first optimize without additives as they can affect fidelity.

FAQ 4: My library amplification shows "jackpot" effects or significant size bias. How can I improve amplicon uniformity?

- Answer: Size bias often occurs when a polymerase has difficulty amplifying fragments of varying lengths uniformly, favoring shorter products. This compromises library complexity.

- Extend Elongation Time: Use a longer extension time (e.g., 30-60 seconds/kb) to ensure complete polymerization of longer fragments.

- Verify Polymerase Processivity: Select a polymerase known for high processivity (nucleotides incorporated per binding event). KAPA HiFi demonstrates high processivity, leading to more uniform representation of different fragment sizes.

- Optimize Template Integrity: Sheared or nicked DNA can cause premature termination, favoring shorter products.

Comparative Performance Data

Table 1: Comparative Performance of High-Fidelity PCR Enzymes

| Polymerase | Manufacturer | Error Rate (per bp) | Proofreading Activity | Processivity | Recommended for Low-Input/Complex Libraries? | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KAPA HiFi HotStart | Roche | ~2.8 x 10⁻⁷ | Yes | Very High | Yes | Superior uniformity, robust on difficult templates |

| Q5 Hot Start | NEB | ~2.8 x 10⁻⁷ | Yes | High | Yes | High fidelity, fast cycling |

| Phusion High-Fidelity | Thermo Fisher | ~4.4 x 10⁻⁷ | Yes | High | With caution* | High speed & yield |

| PrimeSTAR GXL | Takara Bio | ~8.5 x 10⁻⁶ | Yes | High | Yes | Excellent for long & GC-rich targets |

| Standard Taq | Various | ~1 x 10⁻⁴ to 1 x 10⁻⁵ | No | Moderate | No | Low cost, standard applications |

Note: Phusion may exhibit higher bias in ultra-low-input applications compared to KAPA HiFi.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Polymerase Bias in Low-Input RNA-seq Libraries

Objective: To compare the uniformity of coverage and amplification bias introduced by different high-fidelity polymerases during the PCR amplification step of low-input RNA-seq library construction.

Materials:

- Low-input RNA sample (e.g., 10 ng total RNA or 1 ng purified mRNA)

- KAPA RNA HyperPrep Kit (or equivalent)

- Test polymerases: KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix, Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity 2X Master Mix, Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase

- Purified, pre-amplified library from a higher-input control (for comparison)

- NGS Platform (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq)

- Bioinformatics tools for analysis (e.g., Picard Tools, samtools, custom R/Python scripts)

Methodology:

Library Preparation (Parallel Reactions):

- Starting with identical aliquots of the low-input RNA sample, perform reverse transcription and adapter ligation using the KAPA RNA HyperPrep Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions up to, but not including, the PCR amplification step.

- Split the adapter-ligated product into three equal portions.

PCR Amplification with Test Enzymes:

- Amplify each portion using a different test polymerase. Use the minimum recommended number of cycles (e.g., 10 cycles) for all reactions.

- Critical: Keep all other PCR conditions (primer concentration, reaction volume, cycling temperatures) as consistent as possible across polymerases. Use the manufacturer's recommended buffer for each enzyme.

- Include a negative control (no polymerase) for each condition.

Library QC and Pooling:

- Purify all PCR reactions using SPRI beads.

- Quantify libraries using qPCR (e.g., KAPA Library Quantification Kit) for accurate molarity.

- Pool the three libraries in equimolar amounts based on qPCR data.

Sequencing and Data Analysis:

- Sequence the pooled library on an Illumina platform to a sufficient depth (e.g., 50M paired-end reads).

- Bioinformatic Analysis: a. Demultiplex reads and align to the reference genome. b. Calculate coefficient of variation (CV) of coverage across a panel of ~1000 housekeeping genes. A lower CV indicates more uniform coverage. c. Analyze GC-bias by plotting mean coverage as a function of genomic GC content. d. Assess complexity by measuring the non-duplicate read fraction. e. Compare all metrics against the higher-input control library.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Low-Input RNA-seq Bias Mitigation |

|---|---|

| KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix | Proprietary polymerase blend designed for high fidelity, robustness, and uniform amplification from low-input and challenging templates. |

| Unique Molecular Indices (UMIs) | Molecular barcodes added during RT/cDNA synthesis to uniquely tag each original molecule, enabling computational removal of PCR duplicates. |

| RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 8.5 | High-quality input RNA minimizes artifacts and ensures representative reverse transcription, reducing later amplification skew. |

| SPRI (Solid Phase Reversible Immobilization) Beads | For consistent, high-recovery size selection and cleanup, critical for maintaining library balance after PCR. |

| qPCR-based Library Quant Kit | Accurate molar quantification of amplifiable libraries, essential for equitable pooling and avoiding sequencing bias from over/under-represented samples. |

| GC/AT Bias Assessment Tool (e.g., Picard CollectGcBiasMetrics) | Bioinformatic tool to quantify and visualize sequence coverage as a function of GC content, directly reporting polymerase performance. |

Visualizations

Title: Experimental Workflow for Comparing Polymerase Bias

Title: Relationship Between PCR Bias Causes and Mitigation Solutions

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My PCR-free library preparation yields extremely low concentration. What are the primary causes and solutions? A: Low yield in PCR-free protocols is common and often stems from input quantity/quality or fragmentation issues.

- Cause 1: Insufficient or degraded input material.

- Solution: Quantify input DNA/RNA using a fluorescence-based assay (e.g., Qubit). For RNA, check integrity via Bioanalyzer/TapeStation (RIN > 8 recommended). Increase input within the system's linear range.

- Cause 2: Inefficient tagmentation (for hybrid methods like SHERRY).

- Solution: Optimize the tagmentation enzyme-to-input ratio. Verify Mg²⁺ concentration in the reaction buffer, as it is critical for transposase activity. Use fresh, properly stored enzyme aliquots.

- Cause 3: Loss during bead-based cleanups.

- Solution: Ensure beads are at room temperature and thoroughly resuspended. Precisely follow the recommended sample-to-bead ratio and elution conditions. Perform a double-size selection to remove adapter dimers efficiently.

Q2: I observe high duplication rates in my final NGS data from isothermal amplification libraries. How can I mitigate this? A: High duplication rates indicate low complexity, often from over-amplification of limited starting material.

- Mitigation Strategy 1: Reduce the number of amplification cycles. For methods like MDA or SPIA, titrate the reaction time and enzyme amount. Use the minimum required to generate sufficient library mass for sequencing.

- Mitigation Strategy 2: Increase input material if possible. For single-cell or ultra-low-input protocols, ensure cell lysis is complete and reverse transcription is efficient to maximize template availability.

- Mitigation Strategy 3: Incorporate unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) during the initial reverse transcription or tagging step. This allows bioinformatic correction of PCR duplicates post-sequencing.

Q3: When using the SHERRY method for low-input RNA-seq, my cDNA synthesis after tagmentation seems inefficient. What could be wrong? A: SHERRY involves tagmentation of cDNA, so issues often originate in the prior reverse transcription (RT) step.

- Checkpoint 1: RT Reaction Integrity. Ensure the reverse transcriptase is active and the reaction mix contains RNase inhibitors. Use a template-switching oligo (TSO) compatible with your protocol.

- Checkpoint 2: Tagmentation Buffer Compatibility. The cDNA must be in a compatible buffer for the tagmentation enzyme (e.g., Tn5). Purify the cDNA and resuspend it in the recommended tagmentation buffer before proceeding.

- Checkpoint 3: Input Quantification. Re-quantify the double-stranded cDNA before tagmentation. Input into SHERRY tagmentation is typically 100pg-1ng.

Q4: How do I choose between PCR-free, hybrid tagmentation, and isothermal amplification for my low-biomass sample? A: The choice depends on input amount and the need to minimize bias.

| Method | Recommended Input | Key Advantage | Primary Bias Concern | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR-Free | High (≥ 100 ng) | Eliminates PCR bias & duplicates | Requires high input; sensitive to fragmentation bias | Genomic DNA-seq where input is not limiting. |

| Hybrid Tagmentation (e.g., SHERRY) | Low to Moderate (1 pg - 10 ng) | Fast, integrated workflow; reduces hands-on time | Tagmentation sequence preference bias | Low-input RNA-seq, high-throughput applications. |

| Isothermal Amplification (e.g., MDA, SPIA) | Ultra-Low (fg - 1 ng) | Extreme sensitivity; whole-genome/transcriptome amplification | Exponential amplification bias; uneven coverage | Single-cell genomics, clinical specimens with minimal material. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: SHERRY for Low-Input RNA-Seq Library Preparation Based on the SHERRY v2 protocol .

- First-Strand cDNA Synthesis: Combine 1-5 µL of RNA (1pg-1ng), 1 µL of Template-Switch Oligo (TSO), and 1 µL of dNTPs. Heat to 72°C for 3 min, then place on ice. Add 4 µL of reverse transcription master mix (containing RNase inhibitor, reverse transcriptase, and buffer). Incubate: 42°C for 90 min, 10 cycles of (50°C for 2 min, 42°C for 2 min), then 85°C for 5 min.

- Tagmentation & Amplification: Directly add 10 µL of tagmentation mix (containing Tn5 transposase assembled with sequencing adapters) to the 10 µL RT reaction. Incubate at 55°C for 10 min. Add 2.5 µL of Neutralization Buffer and incubate at room temp for 5 min.

- Library PCR: Add 27.5 µL of PCR mix containing index primers and a high-fidelity polymerase. Cycle: 72°C for 3 min; 98°C for 30 sec; 12-15 cycles of (98°C for 10 sec, 63°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 1 min); final extension at 72°C for 5 min.

- Cleanup: Purify with 0.8x ratio of SPRI beads. Elute in 15-20 µL of Tris-HCl (10 mM, pH 8.0). Quantify and check size distribution.

Protocol 2: Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA) for Whole Genome Amplification Adapted for ultra-low DNA input .

- Sample Denaturation: Combine up to 10 µL of sample (containing target DNA) with 1 µL of denaturation buffer (400 mM KOH, 100 mM DTT). Incubate at room temperature for 3 min.

- Neutralization and Master Mix Addition: Add 1 µL of neutralization buffer (400 mM HCl). Prepare MDA master mix on ice: containing reaction buffer, dNTPs, random hexamers, and φ29 DNA polymerase. Add master mix to the neutralized sample for a final volume of 25 µL.

- Isothermal Amplification: Incubate at 30°C for 4-8 hours. The reaction can be terminated by heating at 65°C for 10 min.

- Post-Amplification Cleanup: Purify the amplified product using a column-based purification kit to remove enzymes and salts. Elute in buffer compatible with downstream applications.

Visualizations

SHERRY Library Prep Workflow

Method Selection by Input Amount

Amplification Bias Comparison

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Protocol | Key Consideration for Low-Input |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesizes cDNA from RNA templates with high processivity and fidelity. Essential for template-switching in SHERRY. | Choose enzymes with high efficiency on short, degraded RNA and low RNase H activity. |

| Tagmentation Enzyme (e.g., Tn5) | Simultaneously fragments DNA and ligates sequencing adapters. Core of hybrid protocols like SHERRY. | Pre-loaded with adapters, activity must be optimized for low cDNA/DNA amounts to avoid over-fragmentation. |

| φ29 DNA Polymerase | Strand-displacing polymerase for isothermal amplification (MDA). High processivity and fidelity. | Prone to generating chimeras and bias; use with UMI and limit amplification time. |

| Template-Switching Oligo (TSO) | Provides a universal sequence at the 5' end of cDNA during RT, enabling amplification of full-length transcripts. | Sequence and chemistry (e.g., modified nucleotides) are critical for efficient template switching. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random barcodes added to each original molecule prior to amplification. | Enables bioinformatic correction of PCR duplicates, crucial for quantifying from amplified libraries. |

| SPRI Beads | Magnetic beads for size selection and cleanup of nucleic acids. | The bead-to-sample ratio is critical for recovery of low-concentration libraries and removal of adapter dimers. |

| Single-Cell Lysis Buffer | Efficiently releases nucleic acids while preserving integrity and inactivating RNases. | For ultra-low input, must be compatible with downstream enzymatic steps (RT, amplification). |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in Low-Input RNA-Seq Library Prep

Q1: After library preparation, my Bioanalyzer trace shows a pronounced peak below 150bp. What does this indicate and how can I fix it?

A: A sub-150bp peak typically indicates excessive adapter-dimer formation. This is a critical issue in low-input protocols where adapter:insert ratios are skewed.

- Primary Cause: Insufficient purification after adapter ligation or an imbalance in the reagent ratios during ligation.

- Solution:

- Increase the number of post-ligation clean-ups using SPRI beads. Perform two consecutive 0.9x ratio cleanups instead of one.

- Re-titrate the adapter dilution used. For inputs below 10ng, a 1:20 to 1:50 adapter dilution is often necessary.

- Incorporate a gel-cut or size-selection step post-PCR if the protocol allows.

- Thesis Context: Adapter dimers compete efficiently during PCR, introducing significant quantitative bias and reducing library complexity.

Q2: My libraries show high duplication rates post-sequencing despite starting with viable RNA. What are the likely sources of this bias?

A: High duplication rates point to low library complexity, often stemming from early technical bottlenecks.

- Primary Causes:

- PCR Over-amplification: The most common cause. Too many PCR cycles lead to clonal expansion of a few initial molecules.

- Inefficient Reverse Transcription or Fragmentation: Incomplete capture of starting material.

- Solutions & Protocol Adjustment:

- Quantify Pre-PCR: Use a qPCR-based assay (e.g., Kapa Library Quant) on your post-ligation material to determine the minimum necessary PCR cycles. Do not rely on fixed-cycle protocols for critical low-input work.

- Optimize Enzymatic Fragmentation: If using enzymatic fragmentation, ensure accurate reaction temperature and time. Verify size distribution on a Bioanalyzer before proceeding to RT.

- Use Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): Employ kits with UMI-based correction to computationally remove duplication bias.

Q3: I observe inconsistent gene body coverage and 3’ bias across my samples. Which kit steps should I investigate?

A: This indicates bias introduced during cDNA synthesis or amplification.

- Primary Cause: Inefficient or biased reverse transcription, especially common with random hexamer priming.

- Solution & Protocol:

- Priming Strategy: Consider kits that use a template-switching oligonucleotide (TSO) mechanism, which can improve full-length transcript representation.

- PCR Enzyme: Switch to a high-fidelity, GC-neutral polymerase. Some kits include polymerases better suited for balanced amplification.

- Protocol Modification: Add a pilot experiment comparing a standard kit protocol versus one incorporating a PCR Additive like 1M Betaine or 5% DMSO to mitigate GC-bias during amplification. See table below for data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the most critical step to minimize bias in low-input RNA-seq? A: The reverse transcription and initial cDNA amplification step is the most critical bottleneck. Bias introduced here is irreversibly locked in and amplified by subsequent PCR. Using kits with proven, high-efficiency RT and limiting pre-amplification cycles is paramount.

Q: Should I use ribosomal RNA depletion or poly-A selection for low-input samples (<10ng total RNA)? A: For low-input scenarios, poly-A selection is generally more efficient and consumes less material than ribosomal depletion. However, for degraded samples (e.g., FFPE) or non-polyadenylated RNA, selective rRNA depletion kits designed for low input are required. Choose based on your sample type and research question.

Q: How do I choose between singleplex and duplex (unique dual index) adapters? A: Always use unique dual indexes (UDIs). They enable higher levels of sample multiplexing and drastically reduce index hopping errors, which is crucial for sensitive detection in pooled libraries. The increased cost is negligible compared to the risk of data contamination.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Leading Low-Input RNA Library Prep Kits

| Kit Name (Manufacturer) | Recommended Input Range | PCR Cycles Required | UMI Included? | Key Bias Metric (Gene Body Coverage) | Reported Duplication Rate at 1ng input |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kit A (SMARTer V2) | 1pg - 10ng | 10-15 | No | Moderate 3' bias | 25-40% |

| Kit B (NEBNext Ultra II) | 1ng - 100ng | 12-15 | Optional | Low bias | 15-30% |

| Kit C (Takara Pico) | 1pg - 1ng | 18-22 | Yes | High 3' bias | 40-60%* (UMI-correctable) |

| Kit D (Clontech Smarter-Seq) | 10pg - 10ng | 12-14 | No | Lowest bias | 10-20% |

Data synthesized from current literature and manufacturer specifications. *Reported duplication rate before UMI correction.

Table 2: Impact of PCR Additives on GC Bias (Experimental Data)

| Condition | PCR Additive | % GC-rich Regions Recovered (vs. Control) | CV of Gene Expression (Lower=Better) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | None | 100% (Baseline) | 0.38 |

| Condition 1 | 1M Betaine | 142% | 0.29 |

| Condition 2 | 5% DMSO | 135% | 0.31 |

| Condition 3 | 1M Betaine + 5% DMSO | 155% | 0.26 |

Experiment: 500pg Universal Human Reference RNA (UHRR) prepared with Kit B, 14 PCR cycles, sequenced to 5M reads. GC-rich regions defined as >60% GC content.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: qPCR-Based Determination of Minimum PCR Cycles Purpose: To minimize over-amplification bias by determining the exact number of PCR cycles needed for each library.

- After adapter ligation and clean-up, split the library into 5 aliquots.

- Perform a pilot PCR amplification for each aliquot, varying cycles (e.g., 8, 10, 12, 14, 16).

- Clean up each reaction with a 0.9x SPRI bead ratio.

- Quantify each library using the Kapa Library Quantification Kit for Illumina (or equivalent qPCR assay) against a known standard.

- Plot yield (nM) versus cycle number. Choose the cycle number at the midpoint of the linear amplification phase for the remaining samples.

Protocol 2: Evaluating 3’ Bias with ERCC Spike-In Controls Purpose: To quantitatively compare the positional bias introduced by different kits.

- Spike-In Addition: Add 1µl of a 1:100,000 dilution of ERCC ExFold RNA Spike-In Mix to your low-input RNA sample before starting library prep.

- Library Preparation: Prepare libraries using the kits/protocols being compared.

- Sequencing & Analysis: Sequence all libraries to a minimum depth of 2M paired-end reads.

- Calculation: Map reads to the ERCC reference. For each spike-in transcript, calculate the read coverage ratio of the 5’ end to the 3’ end (e.g., first 20% vs last 20% of the transcript). A ratio of 1 indicates no positional bias; <1 indicates 3' bias.

- Summarize: Report the median 5’/3’ ratio across all detected spike-ins for each kit.

Diagrams

Diagram 1: Low-Input RNA-Seq Workflow & Bias Points

Diagram 2: UMI Correction of PCR Duplication Bias

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Low-Input RNA-Seq |

|---|---|

| ERCC ExFold RNA Spike-In Mixes (Thermo Fisher) | Artificial RNA controls at known concentrations used to quantitatively assess technical sensitivity, accuracy, and positional (3'/5') bias of the entire workflow. |

| KAPA Library Quantification Kit (Roche) | qPCR-based assay for precise, specific quantification of adapter-ligated fragments. Essential for determining the minimum required PCR cycles. |

| RNAClean XP / SPRIselect Beads (Beckman Coulter) | Solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) beads for size-selective purification and clean-up of nucleic acids. Critical for removing adapter dimers. |

| High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix (e.g., Kapa HiFi, Q5) | PCR enzymes with high processivity and low error rates, designed to minimize sequence bias and maintain representation during amplification. |

| PCR Additives (Betaine, DMSO) | Chemical additives that help neutralize GC-content bias during PCR, improving uniform coverage across genomic regions of varying GC content. |

| Unique Dual Index (UDI) Adapters | Adapters containing unique combinatorial barcode pairs that significantly reduce index hopping cross-talk between samples in a multiplexed sequencing run. |

FAQs & Troubleshooting

Q1: What are the primary amplification biases in low RNA input PCR, and how do Betaine and TMAC help? A: Low-input and low-complexity libraries suffer from two main biases: (1) GC-bias, where high-GC targets amplify poorly, and (2) formation of secondary structures (e.g., hairpins) that block polymerase progression. Betaine (a mol. crowding agent) and TMAC (tetramethylammonium chloride, a helix stabilizer) mitigate these issues.

- Betaine reduces the melting temperature difference between GC-rich and AT-rich sequences, promoting more uniform denaturation.

- TMAC specifically stabilizes AT base pairing, reducing nonspecific priming and secondary structure formation in AT-rich regions. Protocol: Add Betaine (final conc. 0.5-1.5 M) and/or TMAC (final conc. 15-60 mM) directly to the PCR master mix. Titrate concentrations for specific library types.

Q2: How should I modify my thermocycling profile when using these additives? A: Additives alter nucleic acid thermodynamics. A two-step or three-step protocol with adjusted temperatures is recommended. Detailed Modified Protocol:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 3 min.

- Cycling (35-40 cycles):

- Denaturation: 98°C for 10-20 sec (higher temp may be needed due to Betaine's stabilizing effect).

- Annealing/Extension:

- Two-step: 68-72°C for 30-60 sec/ kb.

- Three-step: Use if issues persist. Try 62-65°C for 20 sec (annealing) + 72°C for 30 sec/kb (extension).

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5 min. Critical: Include a no-additive control and a no-template control for every run.

Q3: My library yield is still low after additive optimization. What should I check? A: Follow this troubleshooting cascade:

- Verify RNA Integrity: Re-check RINe (RNA Integrity Number equivalent) on a Bioanalyzer/TapeStation. Low input amplifies degradation issues.

- Titrate Additives: High concentrations of Betaine (>2M) or TMAC (>80mM) can become inhibitory. Perform a matrix titration.

- Evaluate Polymerase: Switch to a high-fidelity, GC-rich or "biased-amplification resistant" polymerase blend designed for difficult templates.

- Check Primer Design: Re-evaluate primers for secondary structures and optimal Tm. Consider using a touchdown PCR program in conjunction with additives.

Q4: How do I quantify the improvement from these optimizations? A: Metrics must go beyond total yield. Use Bioanalyzer/TapeStation profiles and qPCR or ddPCR for specific targets.

- Calculate Enrichment Scores: Compare the fold-change in read coverage for previously under-represented genomic regions (e.g., high-GC promoters) after optimization.

- Assess Complexity: Evaluate the percentage of duplicate reads in sequencing data; a significant reduction indicates improved library complexity from more uniform amplification.

Data Summary Tables

Table 1: Additive Optimization Matrix for Low-Input PCR

| Additive | Typical Final Concentration Range | Primary Mechanism | Key Benefit | Potential Drawback |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Betaine | 0.5 M - 1.5 M | Reduces Tm differential, disrupts secondary structures | Evens GC-bias, increases yield | Can inhibit at >2.0 M; may require higher denaturation temp |

| TMAC | 15 mM - 60 mM | Stabilizes AT pairs, increases primer specificity | Reduces mis-priming, improves AT-rich target yield | Can reduce overall efficiency if overused; not for GC-rich only targets |

| Combination | Betaine: 1.0 M + TMAC: 30-40 mM | Combined mechanisms | Broad-spectrum bias reduction | Requires extensive optimization |

Table 2: Comparison of Standard vs. Modified Thermocycling Profiles

| Step | Standard Profile | Modified Profile (with Additives) | Rationale for Modification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denaturation | 95°C, 30 sec | 98°C, 10-20 sec | Counteracts the duplex-stabilizing effect of Betaine. |

| Annealing | Tm +3°C, 30 sec | Tm 0 to -5°C, 20 sec (if 3-step) | TMAC stabilizes primer binding, allowing lower Ta for specificity. |

| Extension | 72°C, 60 sec/kb | 68-72°C, 30-60 sec/kb | Some polymerase blends are efficient at lower, combined Anneal/Extend temps. |

| Cycle Number | 25-30 | 35-40 | Necessary to amplify limiting material from low-input libraries. |

Experimental Workflow Diagram

Title: Workflow for PCR Bias Optimization

Additive Mechanism Diagram

Title: Mechanism of Betaine and TMAC in Bias Reduction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in Low RNA Library PCR Optimization |

|---|---|

| Betaine (5M stock) | Molecular crowding agent that homogenizes melting temperatures and disrupts secondary structures to reduce GC-bias. |

| TMAC (1M stock) | Quaternary ammonium salt that stabilizes AT base pairing, improving primer specificity and reducing mis-priming in AT-rich regions. |

| High-Fidelity/GC-Rich Polymerase Mix | Engineered polymerases with high processivity and stability, often combined with enhancers, to amplify difficult templates efficiently. |

| Low-Bind Tubes & Tips | Minimizes adsorption of precious low-input nucleic acids to plastic surfaces during library preparation and amplification. |

| ddPCR/qPCR Master Mix | For precise, quantitative assessment of library complexity and target-specific enrichment pre- and post-optimization. |

| High-Sensitivity DNA/RNA Assay Kits | Essential for accurate quantification of low-concentration samples (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS, Bioanalyzer HS DNA chip). |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: We observe a significant loss of library diversity in our low-input RNA-seq experiments after the cDNA amplification PCR. What is the most likely cause and how can we mitigate it?

A: The most likely cause is excessive PCR amplification cycles, leading to bias where sequences with higher GC content or longer lengths amplify less efficiently, while duplicates (PCR clones) from initially abundant fragments dominate. To mitigate:

- Minimize PCR Cycles: Use the minimum number of cycles required for adequate library yield. Start by reducing cycles by 2-3 from your standard protocol.

- Optimize PCR Reagents: Use a high-fidelity, low-bias polymerase specifically optimized for library amplification.

- Implement Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): Incorporate UMIs during reverse transcription to bioinformatically identify and collapse PCR duplicates, distinguishing them from true biological duplicates.

Q2: How do we determine the absolute minimum number of PCR cycles needed for our low-input library prep without risking insufficient yield for sequencing?

A: Perform a cycle titration experiment.

- Split your final, adapter-ligated library into several identical aliquots.

- Amplify each aliquot with a different number of PCR cycles (e.g., 8, 10, 12, 14).

- Purify and quantify each library accurately using a fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit).

- Plot the yield (ng) against the cycle number. The minimum viable cycle number is where the yield curve begins to plateau, ensuring you are not in the exponential phase where small variations have large effects on bias.

Q3: Our negative control (no-template) shows high yield after library construction. Does this indicate contamination, and how does it relate to PCR cycle number?

A: High yield in a no-template control is a classic sign of primer-dimer formation and their subsequent over-amplification. This is directly exacerbated by high PCR cycle numbers. Primer-dimers compete with your library fragments for reagents, further reducing complexity.

- Troubleshooting Step: Run your final library on a high-sensitivity Bioanalyzer or TapeStation. A sharp peak ~100-150bp indicates primer-dimers.

- Solution: 1) Re-optimize PCR primer design and annealing conditions. 2) Use bead-based clean-up with a stringent size selection ratio (e.g., 0.8x-0.9x AMPure XP beads) to exclude small fragments. 3) Reduce PCR cycles, as primer-dimer formation becomes less impactful with fewer cycles.

Q4: When using UMIs, we still see uneven coverage. Can reduced PCR cycles help?

A: Yes. While UMIs correct for PCR duplicate bias, they do not correct for amplification bias (differential efficiency of amplifying different sequences). Reducing PCR cycles minimizes the accumulation of amplification bias, leading to more uniform coverage across transcripts of varying sequences and lengths, even after UMI deduplication.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Cycle Titration for Optimal Amplification

Objective: To empirically determine the minimum number of PCR cycles required for low-input RNA-seq libraries.

- Library Preparation: Proceed with your standard low-input RNA library prep protocol (e.g., using a commercial kit) through the adapter ligation step.

- Aliquot: Divide the final ligation product into 5 equal tubes.

- PCR Setup: Prepare a master mix containing a high-fidelity polymerase, primers, and dNTPs. Add equal volumes to each library aliquot.

- Amplify: Run the following PCR programs in parallel:

- Tube 1:

[Your Standard Cycle Count] - 4 - Tube 2:

[Your Standard Cycle Count] - 2 - Tube 3:

[Your Standard Cycle Count] - Tube 4:

[Your Standard Cycle Count] + 2 - Tube 5:

[Your Standard Cycle Count] + 4

- Tube 1:

- Purify & Quantify: Clean up each reaction with AMPure XP beads (0.9x ratio). Elute in equal volumes. Quantify yield using Qubit.

- Analyze: Plot yield vs. cycle number. Select the cycle number at the beginning of the linear plateau for future experiments.

Protocol 2: Post-Amplification Library Assessment for Complexity

Objective: To evaluate the impact of PCR cycle reduction on library complexity.

- Prepare Libraries: Generate libraries from the same low-input RNA sample using your standard cycle count (Control) and the reduced cycle count determined in Protocol 1 (Test).

- Sequencing: Sequence both libraries shallowly (e.g., 5M reads per library) on the same flow cell.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Alignment: Map reads to the reference genome/transcriptome.

- Duplicate Marking: Use UMI-aware tools (if UMIs used) or standard duplicate marking.

- Complexity Metrics: Calculate and compare:

- Fraction of Duplicate Reads: (Marked duplicates / Total reads).

- Number of Genes Detected: At a fixed read depth (via subsampling).

- Coverage Uniformity: Gene body 5'-3' coverage bias or evenness metrics.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of PCR Cycle Number on Library Metrics from a Low-Input (10 pg) Total RNA Sample

| PCR Cycles | Library Yield (nM) | % Duplicate Reads (w/o UMI) | Genes Detected (>5 reads) | Coverage Evenness Score (0-1)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 1.5 | 18% | 9,850 | 0.92 |

| 10 | 4.2 | 35% | 10,100 | 0.88 |

| 12 | 9.8 | 62% | 9,920 | 0.79 |

| 14 | 18.5 | 85% | 8,750 | 0.65 |

| 16 | 32.0 | 95% | 7,100 | 0.54 |

*Coverage Evenness Score: 1 represents perfect uniformity across transcript bodies.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Low-Bias Amplification

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Consideration for Complexity Preservation |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity, Low-Bias Polymerase | Amplifies adapter-ligated cDNA. | Enzymes engineered for uniform amplification across sequences minimize GC% and length bias. |

| Unique Molecular Indices (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide tags added during RT or early cycles. | Enables bioinformatic removal of PCR duplicates; essential for quantifying true molecule count. |

| Strand-Specific Adapters | Allow sequencing of the original RNA strand. | Preserves strand information, improving annotation and reducing false fusion/gene calls. |

| Magnetic Beads (e.g., AMPure XP) | Size selection and clean-up. | Stringent size selection (e.g., 0.8x bead ratio) removes primer-dimers that consume PCR reagents. |

| RNase Inhibitors | Protect RNA templates during early steps. | Critical for low-input samples to prevent degradation before amplification. |

| Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) PCR Primers | Modified primers for improved specificity. | Increase primer annealing efficiency, allowing for lower cycling temperatures and reduced mis-priming. |

Visualizations

Title: Cycle Titration Workflow for Determining Minimal PCR Cycles

Title: Relationship Between PCR Cycles, Bias, and Library Complexity

Diagnosing and Correcting Bias: A Step-by-Step Troubleshooting Framework

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Why is my duplicate read rate excessively high (>50%) in my low-input RNA-seq library? What does this signal, and how can I address it?

A: A high duplicate rate in low-input RNA libraries is a primary indicator of PCR amplification bias. It signals that during library preparation, a limited diversity of original cDNA molecules was over-amplified. This leads to skewed quantification and loss of rare transcripts.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Input Quality: Ensure RNA Integrity Number (RIN) is >7. Use a fluorometric assay for accurate low-concentration quantification.

- Optimize PCR Cycles: Reduce the number of PCR amplification cycles. Use 10-12 cycles for low-input protocols instead of standard 15.

- Use Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): Incorporate UMIs during reverse transcription to bioinformatically distinguish PCR duplicates from true biological duplicates.

- Switch Enzymes: Use a high-fidelity, bias-resistant polymerase specifically designed for low-input library prep.

Q2: My fragment size profile shows an abnormal peak or a shift from the expected distribution. What biases could this indicate?

A: Anomalies in the fragment size profile can signal selection bias during size selection or fragmentation bias.

- Narrow Peak or Missing Sizes: Indicates overly stringent size selection, which can systematically exclude certain transcript isoforms or GC-rich/poor regions.

- Smear or Multiple Peaks: May indicate RNA degradation or inefficient fragmentation, leading to non-uniform coverage.

- Corrective Protocol:

- Use a gel-free, bead-based size selection system for more consistent recovery.

- Calibrate the fragmentation time/temperature using a control sample.

- Analyze the size profile after each major step (cDNA synthesis, fragmentation, post-amplification) to pinpoint the issue stage.