A Comprehensive Guide to Evaluating Differential Expression Analysis Tools: From Foundations to Clinical Applications

This article provides a systematic evaluation of differential gene expression (DGE) analysis tools for RNA sequencing data, addressing critical considerations for researchers and drug development professionals.

A Comprehensive Guide to Evaluating Differential Expression Analysis Tools: From Foundations to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a systematic evaluation of differential gene expression (DGE) analysis tools for RNA sequencing data, addressing critical considerations for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore foundational concepts in bulk and single-cell RNA-seq analysis, compare methodological approaches across leading tools like DESeq2, edgeR, limma, and MAST, and offer practical optimization strategies for experimental design and troubleshooting. Through validation frameworks and performance benchmarking, we synthesize evidence-based recommendations for tool selection across diverse biological contexts, enabling more reliable biomarker discovery and therapeutic target identification in biomedical research.

Understanding Differential Expression Analysis: Core Concepts and Data Challenges

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized transcriptomics by enabling comprehensive, genome-wide quantification of RNA abundance. RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) is a high-throughput technology that detects and quantifies the transcriptome in biological samples, providing unprecedented detail about the RNA landscape. Unlike earlier methods like microarrays, RNA-Seq offers more comprehensive transcriptome coverage, finer resolution of dynamic expression changes, improved signal accuracy with lower background noise, and the ability to identify novel transcripts and isoforms [1] [2] [3].

The fundamental principle behind RNA-Seq involves converting RNA molecules into complementary DNA (cDNA) fragments, which are then sequenced using high-throughput platforms that simultaneously read millions of short sequences (reads). The resulting data captures both the identity and relative abundance of expressed genes in the sample [2]. A key application of RNA-Seq is Differential Gene Expression (DGE) analysis, which identifies genes with statistically significant abundance changes across different experimental conditions, such as treated versus control groups or healthy versus diseased tissues [2].

The RNA-Seq Workflow: From Raw Data to Biological Insights

Transforming raw sequencing data into meaningful biological insights requires a robust, multi-step analytical pipeline. The standard RNA-Seq workflow consists of sequential computational and statistical steps, each with multiple methodological options.

Preprocessing and Read Quantification

The initial phase focuses on processing raw sequencing data to generate accurate gene expression counts [2].

- Quality Control (QC): Raw sequencing reads in FASTQ format are first assessed for potential technical errors, including leftover adapter sequences, unusual base composition, or duplicated reads. Tools like FastQC and multiQC are commonly employed for this initial quality assessment [2] [4].

- Read Trimming and Filtering: This step cleans the data by removing low-quality base calls and adapter sequences that could interfere with accurate mapping. Tools such as Trimmomatic, Cutadapt, or fastp perform this trimming. It is critical to avoid over-trimming, which reduces data quantity and weakens subsequent analysis [2] [4] [3].

- Alignment (Mapping): The cleaned reads are aligned to a reference genome or transcriptome to identify their genomic origins. This can be done with traditional aligners like STAR or HISAT2, or through faster pseudo-alignment methods such as Kallisto or Salmon, which estimate transcript abundances without base-by-base alignment [2] [5].

- Post-Alignment QC and Quantification: After alignment, poorly aligned or multimapping reads are filtered out using tools like SAMtools or Picard. The final step involves counting the reads mapped to each gene, producing a raw count matrix that summarizes expression levels for each gene across all samples. Tools like featureCounts or HTSeq-count typically perform this counting [2].

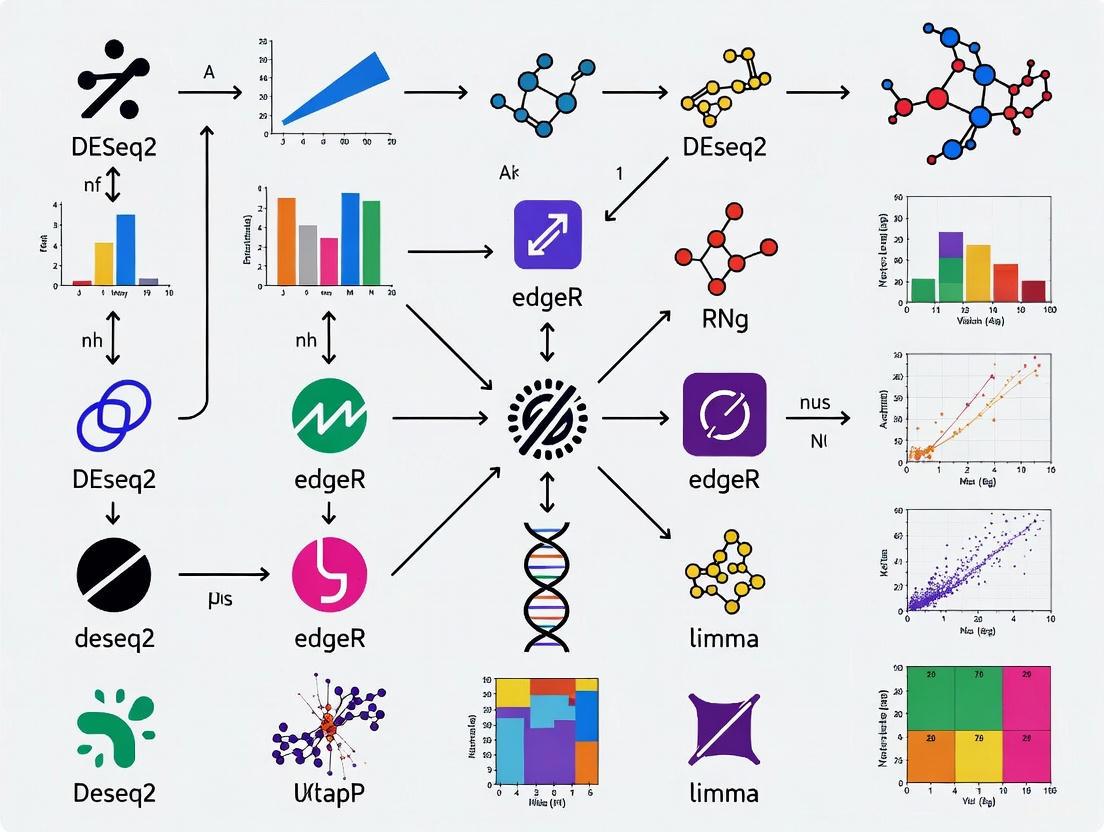

The following diagram illustrates this multi-stage preprocessing workflow:

Experimental Design Considerations

The reliability of DGE analysis heavily depends on thoughtful experimental design, particularly regarding biological replicates and sequencing depth [2].

- Biological Replicates: While DGE analysis is technically possible with only two replicates, the ability to estimate biological variability and control false discovery rates is greatly reduced. A single replicate per condition does not allow for robust statistical inference and should be avoided for hypothesis-driven experiments. A minimum of three replicates per condition is often considered the standard, though more replicates increase power to detect true differences, especially when biological variability is high [2].

- Sequencing Depth: This refers to the total number of reads sequenced per sample. Deeper sequencing captures more reads per gene, increasing sensitivity to detect lowly expressed transcripts. For standard DGE analysis, approximately 20–30 million reads per sample is often sufficient. Requirements can be guided by pilot experiments, existing datasets, or power analysis tools [2].

Normalization Techniques

The raw counts in the gene expression matrix cannot be directly compared between samples because the number of reads mapped to a gene depends not only on its true expression level but also on the sample's sequencing depth (total number of reads) and library composition (transcript abundance distribution) [2] [5]. Normalization mathematically adjusts these counts to remove such technical biases. The table below compares common normalization methods:

Table: Comparison of RNA-Seq Normalization Methods

| Method | Sequencing Depth Correction | Gene Length Correction | Library Composition Correction | Suitable for DE Analysis | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM (Counts per Million) | Yes | No | No | No | Simple scaling by total reads; heavily affected by highly expressed genes [2]. |

| RPKM/FPKM | Yes | Yes | No | No | Adjusts for gene length; still affected by differences in library composition between samples [2]. |

| TPM (Transcripts per Million) | Yes | Yes | Partial | No | Scales each sample to a constant total (1 million); reduces composition bias compared to RPKM/FPKM [2]. |

| Median-of-Ratios (DESeq2) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Robust to composition biases; affected by large shifts in expression [2] [5]. |

| TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values, edgeR) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Robust to composition biases; performance can be affected by which genes are trimmed [2] [5]. |

Differential Gene Expression Analysis: A Comparative Guide

Differential Gene Expression (DGE) analysis identifies genes with statistically significant abundance changes between experimental conditions. Numerous tools have been developed, each with distinct normalization approaches, statistical models, and performance characteristics [2] [5].

- DESeq2: Employs empirical shrinkage estimation of dispersions and logarithmic fold-changes. It uses a negative binomial model and performs well across various conditions [6] [2].

- edgeR: Uses a negative binomial model with a variety of analysis options, including exact tests, generalized linear models (GLM), quasi-likelihood methods, and robust variants designed to handle outlier counts [6].

- voom/limma: Transforms normalized count data to model the mean-variance relationship, enabling the application of linear models originally developed for microarray data. Can be combined with sample weighting (voomSW) for improved performance when sample quality varies [6] [7].

- ALDEx2: A log-ratio transformation-based method that uses a Dirichlet-multinomial model to account for the compositional nature of sequencing data. It is known for high precision (few false positives) [5].

- NOISeq: A non-parametric method that can be particularly robust to variations in sample size and data characteristics [8].

Performance Benchmarking of DGE Tools

Comparative studies have evaluated DGE methods under various simulated and real experimental conditions. Key performance metrics include the Area Under the Receiver Operating Curve (AUC), which measures overall discriminatory ability; True Positive Rate (TPR) or power; and control of false discoveries via the False Discovery Rate (FDR) [6].

The table below synthesizes performance data from multiple benchmarking studies, providing a comparative overview of how different tools perform under various conditions:

Table: Performance Comparison of Differential Expression Analysis Tools

| Tool | Overall AUC | Power (TPR) | False Positive Control | Performance with Small Sample Sizes | Robustness to Outliers | Key Strengths and Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | High | Medium-High | Good | Good | Good | Steady performance across various conditions; good overall choice [6] [7]. |

| edgeR | High | High | Good (varies by method) | Good | Good (robust version) | High power; multiple variants for different scenarios (e.g., edgeR.rb for outliers) [6] [8]. |

| edgeR (robust) | High | High | Medium | Good | Excellent | Particularly outperforms in presence of outliers and with larger sample sizes (≥10) [6]. |

| edgeR (quasi-likelihood) | Medium-High | Medium | Good | Good | Good | Better false discovery rate control and false positive counts compared to other edgeR methods [6]. |

| voom/limma | High | Medium | Good | Good | Good | Overall good performance for most cases; powers can be relatively low [6]. |

| voom with sample weights | High | Medium-High | Good | Good | Excellent | Outperforms other methods when samples have amplified dispersions or quality differences [6]. |

| ALDEx2 | Medium-High | Medium (increases with sample size) | Excellent | Medium (requires sufficient samples) | Good | Very high precision (few false positives); good for compositional data analysis [5]. |

| NOISeq | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Excellent | Excellent | Most robust method in one study; non-parametric approach less sensitive to sample size changes [8]. |

| ROTS | High | Medium-High (especially for unbalanced DE) | Good | Good | Good | Outperforms other methods when differentially expressed genes are unbalanced between up- and down-regulated [6]. |

Impact of Experimental Conditions on Tool Performance

The performance of DGE tools can vary significantly depending on specific experimental conditions:

- Proportion of DE Genes: Some methods, including certain edgeR variants and voom with quantile normalization, show decreased performance as the proportion of DE genes increases. DESeq2, edgeR robust, and voom with TMM generally maintain stable performance regardless of DE proportion [6].

- Sample Size: Performance of all methods generally improves with larger sample sizes. NOISeq has been noted for particular robustness to changes in sample size [8].

- Presence of Outliers: The robust versions of edgeR (edgeR.rb) and voom with sample weights (voom.sw) are specifically designed to handle datasets with outlier counts or samples with amplified technical variability [6].

- Balance of DE Genes: When the number of up-regulated and down-regulated DE genes is highly asymmetric, ROTS applied to raw count data has been shown to outperform other methods [6].

The relationships between experimental conditions and optimal tool selection can be visualized as follows:

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking DGE Tools

Benchmarking studies typically employ carefully designed experiments to evaluate DGE tool performance. The following protocol summarizes key methodologies from recent comprehensive assessments.

- Simulated Data: Generated using packages like polyester in R, which simulates RNA-Seq read counts following a negative binomial distribution. Simulation allows precise knowledge of true differentially expressed genes, enabling accurate calculation of false discovery rates and power [5].

- Spike-in Data: Uses RNA transcripts of known concentration added to samples in known differential ratios. These provide true positive controls but may represent only technical variability [6].

- Real Biological Datasets: Publicly available RNA-Seq data from repositories like NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA). These provide realistic biological variability but lack perfect knowledge of true DE genes, often requiring validation with qRT-PCR [5] [3].

Performance Metrics and Validation

- qRT-PCR Validation: Considered the gold standard for validating DGE results. Studies typically select a subset of genes (both differentially expressed and non-differential) for technical validation using TaqMan assays or similar methods. The ΔΔCt method is commonly used for quantification, with normalization based on stable reference genes or global median expression [3].

- Calculation of Performance Metrics:

- True Positive Rate (TPR): Proportion of true DE genes correctly identified as significant.

- False Discovery Rate (FDR): Proportion of significant genes that are not truly differentially expressed.

- Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC): Overall measure of discriminatory power across all possible significance thresholds.

- False Positive Counts (FPCs): Number of significant genes identified in datasets with no true differentially expressed genes (Type I error control) [6].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The table below details key reagents, software tools, and resources essential for implementing a complete RNA-Seq and DGE analysis workflow.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for RNA-Seq Analysis

| Category | Item/Software | Primary Function | Example Applications/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | RNA Isolation Kit | Extraction of high-quality total RNA | Minimum RIN (RNA Integrity Number) of 8.0 recommended for library prep |

| TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit | Construction of sequencing-ready libraries | Creates strand-specific cDNA libraries with dual indexing | |

| RNA Spike-in Controls | Technical controls for normalization | External RNA Controls Consortium (ERCC) spikes | |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq/SiSeq | High-throughput short-read sequencing | Sequencing-by-synthesis; dominant platform for RNA-Seq |

| PacBio Sequel | Long-read sequencing for isoform detection | Resolves complex transcript isoforms without assembly | |

| Oxford Nanopore | Real-time long-read sequencing | Direct RNA sequencing; very long reads possible | |

| Computational Tools | FastQC, multiQC | Quality control of raw sequencing data | Assesses per-base quality, adapter contamination, GC content |

| Trimmomatic, fastp | Read trimming and adapter removal | Critical for removing low-quality bases and technical sequences | |

| STAR, HISAT2 | Splice-aware alignment to reference genome | Maps reads to genomic coordinates, accounting for introns | |

| Salmon, Kallisto | Pseudoalignment and transcript quantification | Faster than traditional alignment; estimates transcript abundance | |

| DESeq2, edgeR | Differential expression analysis | Implements negative binomial models with robust normalization | |

| IGV (Integrative Genomics Viewer) | Visualization of aligned reads | Enables manual inspection of read coverage across genomic regions |

RNA-Seq technology provides a powerful platform for comprehensive transcriptome analysis, with DGE being one of its most prominent applications. The optimal DGE analysis workflow depends on multiple factors, including experimental design, sample characteristics, and biological question. Based on current benchmarking evidence, DESeq2, edgeR (particularly its robust variant), and voom/limma with TMM normalization generally demonstrate strong overall performance across diverse conditions. For specialized scenarios—such as datasets with outliers, highly unbalanced differential expression, or very small sample sizes—alternative tools like NOISeq, ROTS, or ALDEx2 may offer advantages.

Future developments in RNA-Seq analysis will likely focus on improved handling of multi-omics integration, single-cell RNA-Seq data, spatial transcriptomics, and the incorporation of artificial intelligence approaches to extract deeper biological insights from complex transcriptomic datasets.

Key Characteristics of Bulk vs. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Data

Within the framework of evaluating differential expression analysis tools, understanding the fundamental nature of the input data is paramount. Bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) represent two primary approaches for transcriptome analysis, each generating data with distinct characteristics that directly influence the choice and performance of downstream computational methods. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two data types, focusing on their key properties, experimental generation, and implications for differential expression analysis in drug development and basic research.

Tabular Comparison of Key Characteristics

The core differences between bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing data stem from their resolution, which in turn dictates their cost, complexity, and primary applications.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Bulk vs. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Data

| Feature | Bulk RNA-Seq | Single-Cell RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Average gene expression across a population of cells [9] [10] [11] | Gene expression profile of each individual cell [9] [12] |

| Cost per Sample | Lower (approximately 1/10th of scRNA-seq) [10] | Higher [9] [10] |

| Data Complexity | Lower, more straightforward analysis [9] [10] | Higher, requires specialized computational methods [9] [10] [13] |

| Detection of Cellular Heterogeneity | Limited, masks differences between cells [9] [10] | High, reveals distinct cell populations and states [9] [10] [11] |

| Rare Cell Type Detection | Limited, easily masked by abundant cells [10] [14] | Possible, can identify rare and novel cell types [10] [11] [14] |

| Gene Detection Sensitivity | Higher, detects more genes per sample [10] | Lower per cell, but aggregated across many cells [10] |

| Primary Data Challenge | Batch effects, confounding from cellular heterogeneity [15] | Technical noise, dropout events (excess zeros), and sparsity [16] [12] [17] |

| Typical Data Structure | Matrix of read counts for genes (rows) across samples (columns) [18] | Matrix of read counts for genes (rows) across individual cells (columns), often with Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) [12] |

Experimental Protocols and Data Generation

The distinct characteristics of bulk and single-cell data are a direct result of their differing laboratory workflows.

Bulk RNA-Seq Experimental Workflow

Bulk RNA-seq protocols begin with a population of cells or a piece of tissue. RNA is extracted from the entire population, fragmenting the transcriptome and creating a sequencing library where the cellular origin of each RNA molecule is lost, resulting in an average expression profile [9] [11] [18]. The key steps include:

- Total RNA Extraction: RNA is isolated from the entire sample [9].

- Library Preparation: RNA is converted to cDNA, fragmented, and sequencing adapters are ligated. Enrichment for poly-adenylated mRNA or depletion of ribosomal RNA is common [9] [15] [18].

- Sequencing & Quantification: Libraries are sequenced on a high-throughput platform. The resulting reads are aligned to a reference genome, and expression is quantified as the number of reads mapped to each gene for each sample, producing a count matrix [15] [18].

Single-Cell RNA-Seq Experimental Workflow

In contrast, scRNA-seq workflows begin by physically separating individual cells before library construction, preserving cell-of-origin information [9] [12]. A common high-throughput method, droplet-based sequencing, involves:

- Single-Cell Suspension: Creation of a viable, single-cell suspension from tissue via enzymatic or mechanical dissociation [9] [12].

- Cell Partitioning & Barcoding: Single cells are isolated into nanoliter-scale droplets (GEMs) along with barcoded beads. Each bead contains millions of oligonucleotides with a unique cell barcode, a unique molecular identifier (UMI), and a poly(dT) sequence. Within each droplet, cell lysis occurs, and mRNA is barcoded with the cell's unique identifier [9] [11].

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Barcoded cDNA from all cells is pooled, amplified, and prepared for sequencing. After sequencing, computational pipelines use the cell barcodes to attribute each read to its cell of origin and use UMIs to correct for PCR amplification bias, generating a count matrix of genes by individual cells [9] [12] [13].

Experimental Data Supporting the Comparisons

The theoretical differences between bulk and single-cell data are consistently demonstrated in practical research applications.

Case Study in Cancer Research

A study on human B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) leveraged both bulk and single-cell RNA-seq. While bulk analysis provided an overall expression profile, scRNA-seq was critical for identifying the specific developmental cell states that drove resistance or sensitivity to the chemotherapeutic agent asparaginase. This illustrates how bulk analysis can pinpoint differential expression, but single-cell resolution is required to attribute those expression changes to specific, and sometimes rare, subpopulations within a heterogeneous sample [9].

Characterizing Tumor Microenvironments

In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), scRNA-seq identified a rare subpopulation of tumor cells at the invasive front undergoing a partial epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (p-EMT), a program linked to metastasis. This rare but critical population's signal is typically diluted and obscured in bulk sequencing of the entire tumor mass [11]. Similarly, another scRNA-seq study of metastatic lung cancer revealed tumor heterogeneity and changes in cellular plasticity induced by cancer, insights not accessible via bulk profiling [10].

Power and Experimental Design

The statistical power for detecting differentially expressed genes (DEGs) is influenced differently in the two technologies. For bulk RNA-seq, power is primarily determined by the number of biological replicates, with sequencing depth being a secondary factor [17]. In contrast, power in scRNA-seq depends on the number of cells sequenced per population and the complexity of the cellular heterogeneity. Bulk RNA-seq data, being an average, is less sparse and often modeled with a negative binomial distribution. scRNA-seq data, however, contains a substantial number of zero counts (dropouts) due to both biological absence of transcription and technical artifacts, requiring specialized zero-inflated or other statistical models to accurately identify DEGs [16] [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Platforms

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-Seq

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium System | An integrated microfluidic platform for partitioning thousands of single cells into GEMs for barcoding and library preparation [9] [11]. |

| Barcoded Gel Beads | Microbeads containing oligonucleotides with cell barcodes and UMIs, essential for tagging all mRNA from a single cell in droplet-based scRNA-seq [9] [11]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences that label individual mRNA molecules, allowing for the accurate quantification of transcript counts by correcting for PCR amplification bias [12]. |

| STAR Aligner | A popular splice-aware aligner used to map sequencing reads to a reference genome, commonly used in both bulk and single-cell pipelines [18] [13]. |

| Salmon / kallisto | Tools for rapid transcript-level quantification of RNA-seq data using pseudo-alignment, which can be applied to both bulk and single-cell data analysis [18]. |

| Seurat / Scanpy | Standard software toolkits for the comprehensive downstream analysis of scRNA-seq data, including filtering, normalization, clustering, and differential expression [13]. |

| Limma-voom / DESeq2 / edgeR | Established statistical software packages for performing differential expression analysis on bulk RNA-seq count data [17] [18]. |

| Cyproterone acetate-d3 | Cyproterone acetate-d3, MF:C24H29ClO4, MW:420.0 g/mol |

| (S)-Stiripentol-d9 | (S)-Stiripentol-d9 |

Bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing are complementary technologies that generate data with fundamentally different properties. The choice between them is not a matter of superiority but of experimental goal. Bulk RNA-seq remains a powerful, cost-effective tool for generating high-level transcriptional signatures and comparing average gene expression across well-defined conditions or large cohorts. In contrast, single-cell RNA-seq is indispensable for deconvoluting cellular heterogeneity, discovering novel cell types or states, and understanding complex biological systems at their fundamental unit—the individual cell. For researchers evaluating differential expression tools, this distinction is critical: the statistical methods and computational tools must be specifically chosen and validated for the type of data—population-averaged or single-cell—that they are designed to interpret.

The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has fundamentally transformed biological research by enabling the investigation of transcriptomic landscapes at unprecedented cellular resolution. This technology has proven invaluable for uncovering cellular heterogeneity, identifying novel cell populations, and reconstructing developmental trajectories [19]. However, the analysis of scRNA-seq data presents unique computational challenges that distinguish it from traditional bulk RNA sequencing approaches. Three interconnected technical issues—drop-out events, cellular heterogeneity, and zero inflation—represent significant hurdles that can compromise the accuracy and interpretability of differential expression analyses [20] [21].

Drop-out events describe the phenomenon where a gene is expressed at a moderate or high level in one cell but remains undetected in another cell of the same type [19]. This technical artifact arises from the minimal starting amounts of mRNA in individual cells, inefficiencies in reverse transcription, amplification biases, and stochastic molecular interactions during library preparation [20] [22]. The consequence is a highly sparse gene expression matrix where zeros may represent either true biological absence (biological zeros) or technical failures (non-biological zeros) [20]. The inability to distinguish between these zero types compounds the challenge of cellular heterogeneity, where genuine biological variation between cells becomes conflated with technical noise [21]. Zero inflation—an excess of zero observations beyond what standard count distributions would predict—further complicates statistical modeling and differential expression testing [20] [21].

These technical artifacts collectively impact the performance of differential expression analysis tools, potentially leading to reduced detection power, inflated false discovery rates, and biased estimation of fold-changes [21]. This comparative guide evaluates how current computational approaches contend with these challenges, providing researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate methodologies based on empirical performance benchmarks.

Understanding the Nature of Zeros in scRNA-seq Data

Classification of Zero Types

The excessive zeros observed in scRNA-seq datasets originate from distinct biological and technical sources, each with different implications for data analysis. Understanding this distinction is critical for selecting appropriate analytical strategies [20].

Biological zeros represent the true absence of a gene's transcripts in a cell, reflecting the actual transcriptional state [20]. These zeros occur either because a gene is not expressed in a particular cell type or due to transcriptional bursting, where genes transition between active and inactive states in a stochastic manner [20]. Biological zeros carry meaningful information about cellular identity and function, and their preservation in analysis is often desirable.

Non-biological zeros (often called "dropouts") arise from technical limitations in the scRNA-seq workflow [20]. These can be further categorized as:

- Technical zeros: Occur during library preparation steps, including inefficient cell lysis, mRNA capture, reverse transcription, or cDNA amplification [20].

- Sampling zeros: Result from limited sequencing depth, where transcripts expressed at low levels are not sampled for detection [20].

The proportion of these zero types varies significantly across experimental protocols. Tag-based UMI protocols (e.g., Drop-seq, 10x Genomics Chromium) typically exhibit different zero patterns compared to full-length protocols (e.g., Smart-seq2) [20]. Unfortunately, distinguishing biological from non-biological zeros in experimental data remains challenging without additional biological knowledge or spike-in controls [20].

Impact on Downstream Analyses

The prevalence of zeros in scRNA-seq data has profound implications for downstream analyses:

- Cell Clustering: Zero inflation can distort distance metrics between cells, potentially obscuring genuine biological subgroups or creating artificial clusters based on technical artifacts [19] [22].

- Differential Expression: Excessive zeros violate the distributional assumptions of standard statistical models, leading to biased dispersion estimates and reduced power to detect true expression differences [21].

- Trajectory Inference: Dropout events can disrupt the continuity of developmental trajectories, making it difficult to reconstruct accurate pseudotemporal ordering of cells [22].

The following diagram illustrates the sources and impacts of zeros in scRNA-seq data:

Computational Strategies for Addressing Technical Challenges

Philosophical Approaches to Handling Zeros

Computational methods have adopted three distinct philosophical approaches to contend with zeros in scRNA-seq data:

Imputation-Based Methods: These approaches, including DrImpute and MAGIC, treat zeros as missing data that require correction [22]. DrImpute employs a hot-deck imputation strategy that identifies similar cells through clustering and averages expression values within these clusters to estimate missing values [22]. The algorithm performs multiple imputations using different clustering results (varying the number of clusters k and correlation metrics) and averages these estimates for robustness [22]. Similarly, MAGIC uses heat diffusion to share information across similar cells, effectively smoothing the data to reduce sparsity [22]. While imputation can improve downstream analyses like clustering and trajectory inference, it risks introducing false signals by imputing values for truly unexpressed genes [22].

Embracement Strategies: Contrary to imputation, some methods propose leveraging dropout patterns as useful biological signals [19]. The "co-occurrence clustering" algorithm binarizes scRNA-seq data, transforming non-zero counts to 1, and clusters cells based on the similarity of their dropout patterns [19]. This approach operates on the hypothesis that genes within the same pathway exhibit correlated dropout patterns across cell types, providing a signature for cell identity [19]. Demonstrations on peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) datasets showed that dropout patterns could identify major cell types as effectively as quantitative expression of highly variable genes [19].

Statistical Modeling Approaches: These methods explicitly model the zero-inflated nature of scRNA-seq data through specialized distributions. Zero-inflated negative binomial (ZINB) models, as implemented in ZINB-WaVE, represent the data as a mixture of a point mass at zero (representing dropouts) and a negative binomial count component (representing true expression) [21]. These models can generate gene- and cell-specific weights that quantify the probability that an observed zero is a technical dropout versus a biological zero [21]. These weights can then be incorporated into standard bulk RNA-seq differential expression tools to improve their performance on scRNA-seq data [21].

Weighting Strategies for Bulk RNA-seq Tools

A particularly effective approach involves using ZINB-derived weights to "unlock" bulk RNA-seq tools for single-cell applications [21]. The ZINB-WaVE method computes posterior probabilities that a given count was generated from the NB count component rather than the dropout component:

[ w{ij} = \frac{(1 - \pi{ij}) f{\text{NB}}(y{ij}; \mu{ij}, \thetaj)}{f{\text{ZINB}}(y{ij};\mu{ij}, \thetaj, \pi_{ij})} ]

where (w{ij}) represents the weight for cell i and gene j, (\pi{ij}) is the dropout probability, and (f{\text{NB}}) and (f{\text{ZINB}}) are the NB and ZINB probability mass functions, respectively [21].

These weights are then incorporated into bulk RNA-seq tools like edgeR, DESeq2, and limma-voom, which readily accommodate observation-level weights in their generalized linear models [21]. This approach effectively down-weights potential dropout events during dispersion estimation and statistical testing, recovering the true mean-variance relationship and improving power for differential expression detection [21].

Experimental Benchmarking of Differential Expression Tools

Benchmarking Methodology

Comprehensive evaluation of differential expression tools requires carefully designed benchmarking studies that assess performance across diverse datasets and experimental conditions. The following experimental protocol synthesizes best practices from multiple recent evaluations [23] [7] [24]:

Dataset Selection and Preparation:

- Synthetic Data Generation: Using tools like compcodeR to simulate count data from negative binomial distributions with known differential expression status, enabling calculation of true positive and false positive rates [23]. Parameters should include varying sample sizes (from small [n=3] to large [n=100] per condition), different proportions of truly differentially expressed genes, and varying effect sizes [23].

- Real Biological Datasets: Inclusion of publicly available datasets with validated cell types or conditions, such as the Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell (PBMC) dataset from 10X Genomics or cancer datasets from GEO with healthy versus tumor tissue comparisons [19] [24].

- Data Preprocessing: Consistent quality control applied across all comparisons, including filtering of low-quality cells and lowly expressed genes, with normalization methods appropriate for each tool [7].

Performance Metrics:

- Sensitivity and Specificity: True positive and true negative rates in synthetic datasets where the true differential expression status is known [23].

- False Discovery Control: Comparison of nominal versus actual false discovery rates, particularly at standard thresholds (e.g., FDR < 0.05) [7].

- Agreement Measures: Concordance between tools in real datasets assessed through correlation of p-values, log-fold-changes, and overlap of significantly differentially expressed gene lists [24].

- Stability: Consistency of results across repeated simulations or subsampled datasets [23].

Experimental Design Considerations:

- Sample Size Variability: Explicit evaluation of tool performance with small sample sizes (3-10 samples per condition) common in pilot studies versus larger cohorts [23].

- Batch Effects: Assessment of robustness to technical confounding factors [7].

- Computational Efficiency: Measurement of runtime and memory requirements, particularly important for large-scale single-cell studies [25].

The following workflow diagram outlines a standardized benchmarking approach:

Comparative Performance of Differential Expression Tools

Recent benchmarking studies have evaluated the performance of leading differential expression tools when applied to single-cell RNA-seq data, with particular attention to their ability to handle zero inflation and other technical challenges.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Differential Expression Tools on scRNA-seq Data

| Tool | Underlying Model | Zero Inflation Handling | Small Sample Performance | Computational Efficiency | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| edgeR | Negative Binomial GLM | Observation weights [21] | Moderate [23] | High [24] | Robust dispersion estimation, extensive community use |

| DESeq2 | Negative Binomial GLM | Observation weights [21] | Moderate [23] | Moderate [24] | Conservative inference, reliable FDR control |

| limma-voom | Linear modeling of log-CPM | Observation weights [21] | Good [7] | High [24] | Flexibility for complex designs, empirical Bayes moderation |

| dearseq | Non-parametric variance model | Not specifically addressed | Good with small samples [7] | Moderate [7] | Robust to outliers, suitable for complex designs |

| MAST | Hurdle model | Explicit zero-inflation component [21] | Good [21] | Moderate [21] | Specifically designed for scRNA-seq, accounts for cellular detection rate |

| DElite | Tool aggregation | Combined approach [23] | Excellent with small samples [23] | Lower (multiple tools) [23] | Integrates four tools, improved detection power |

Table 2: Quantitative Benchmarking Results Across Dataset Types (Synthetic Data) [23]

| Tool/Method | Sensitivity (Small n) | Specificity (Small n) | F1 Score (Small n) | Sensitivity (Large n) | Specificity (Large n) | F1 Score (Large n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | 0.68 | 0.92 | 0.72 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| edgeR | 0.72 | 0.89 | 0.74 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.95 |

| limma-voom | 0.75 | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.96 |

| dearseq | 0.71 | 0.94 | 0.75 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.94 |

| DElite (Fisher) | 0.81 | 0.91 | 0.82 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.97 |

The DElite package represents an innovative approach that combines results from multiple individual tools (edgeR, limma, DESeq2, and dearseq) [23]. By aggregating evidence across methods, it aims to provide more robust differential expression calls, particularly valuable for small sample sizes where individual tools may struggle [23]. The package implements six different p-value combination methods (Lancaster's, Fisher's, Stouffer's, Wilkinson's, Bonferroni-Holm's, Tippett's) to integrate results across the constituent tools [23]. Validation studies demonstrated that the combined approach, particularly using Fisher's method, improved detection power while maintaining false discovery control in synthetic datasets with known ground truth [23].

Impact of Normalization Methods

Normalization represents a critical preprocessing step that significantly impacts differential expression results, particularly for scRNA-seq data with its characteristic zero inflation [7]. Different normalization approaches can either mitigate or exacerbate technical artifacts:

- TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values): Implemented in edgeR, corrects for compositional biases between samples by scaling factors based on a trimmed mean of log expression ratios [7].

- DESeq2's Median of Ratios: Assumes most genes are not differentially expressed and computes size factors based on the median ratio of counts relative to a geometric mean reference [7].

- Upper Quartile (UQ): Uses the upper quartile of counts as a scaling factor, potentially more robust to zero inflation than total count normalization [26].

- Gene-Wise Normalization (Med-pgQ2, UQ-pgQ2): Per-gene normalization after per-sample median or upper-quartile global scaling has shown improved specificity for data skewed toward lowly expressed genes with high variation [26].

Benchmarking studies have revealed that while common methods like TMM and DESeq2's median of ratios yield high detection power (>93%), they may trade off specificity (<70%) in datasets with high technical variation [26]. Gene-wise normalization approaches can improve specificity (>85%) while maintaining good detection power (>92%) and controlling the actual false discovery rate close to the nominal level [26].

Integrated Analysis Platforms and Emerging Solutions

Comprehensive scRNA-seq Analysis Ecosystems

The computational challenges of single-cell analysis have spurred the development of integrated platforms that provide end-to-end solutions from raw data processing to biological interpretation:

Table 3: Integrated scRNA-seq Analysis Platforms

| Platform | Key Features | Zero Inflation Handling | Usability | Cost Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nygen | AI-powered cell annotation, batch correction, Seurat/Scanpy integration [25] | Not specified | No-code interface, cloud-based [25] | Freemium (free tier, $99+/month) [25] |

| BBrowserX | BioTuring Single-Cell Atlas access, automated annotation, GSEA [25] | Not specified | No-code interface, AI-assisted [25] | Free trial, custom pricing [25] |

| Partek Flow | Drag-and-drop workflow builder, pathway analysis [25] | Not specified | Visual interface, local/cloud deployment [25] | $249+/month [25] |

| InMoose | Python implementation of limma, edgeR, DESeq2 [24] | Via original tool capabilities | Programming required, Python ecosystem [24] | Open source [24] |

| Galaxy | Web-based, drag-and-drop interface [27] | Via tool selection | Beginner-friendly, no coding [27] | Free public servers [27] |

These platforms aim to make sophisticated single-cell analysis accessible to researchers without extensive computational expertise, though they may sacrifice flexibility compared to programming-based approaches [25]. Performance benchmarks specific to their handling of dropout events are often not comprehensively documented in independent evaluations.

Interoperability Between R and Python Ecosystems

The historical dominance of R in bioinformatics has created challenges for integration with the expanding Python ecosystem in data science and machine learning [24]. The InMoose library addresses this gap by providing Python implementations of established R-based differential expression tools (limma, edgeR, DESeq2) that serve as drop-in replacements with nearly identical results [24]. Validation studies demonstrated almost perfect correlation (Pearson correlation >99%) between InMoose and the original R tools for both log-fold-changes and p-values across multiple microarray and RNA-seq datasets [24]. This interoperability facilitates the construction of integrated analysis pipelines that leverage strengths from both ecosystems while avoiding cross-language technical barriers.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful differential expression analysis requires both biological and computational "reagents." The following table outlines key resources for robust experimental design and analysis:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq DE Analysis

| Reagent/Tool | Category | Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Wet-lab reagent | Corrects for amplification bias, enables more accurate quantification [20] | 10x Genomics, Drop-seq [20] |

| Spike-in RNAs | Control reagents | Distinguish technical zeros from biological zeros, normalize samples [20] | ERCC (External RNA Controls Consortium) [20] |

| ZINB-WaVE | Computational method | Models zero inflation, generates observation weights [21] | R/Bioconductor package [21] |

| DrImpute | Computational method | Imputes dropout events using cluster-based similarity [22] | R package [22] |

| DElite | Computational framework | Integrates multiple DE tools for consensus calling [23] | R package [23] |

| InMoose | Computational environment | Python implementation of established DE tools [24] | Python package [24] |

| Normalization Methods | Computational algorithm | Corrects for technical variation, composition biases [7] [26] | TMM, DESeq2's median of ratios, Med-pgQ2 [7] [26] |

The comprehensive evaluation of differential expression tools reveals several key insights for researchers confronting dropout events, cellular heterogeneity, and zero inflation in scRNA-seq data:

Tool Selection Guidelines:

- For small sample sizes (n < 10 per condition), combined approaches like DElite or robust methods like dearseq provide superior detection power while controlling false discoveries [23] [7].

- When computational efficiency is critical for large datasets, edgeR and limma-voom offer excellent performance with manageable computational requirements [24].

- For maximum reliability in well-powered studies (n > 20 per condition), DESeq2's conservative approach provides strong false discovery control [23] [24].

- When integrating with Python-based workflows, InMoose provides nearly identical results to original R implementations, facilitating cross-ecosystem interoperability [24].

Methodological Recommendations:

- Weighting strategies that downweight likely dropout events significantly improve the performance of bulk RNA-seq tools on single-cell data [21].

- Normalization methods should be selected based on data characteristics, with gene-wise approaches (Med-pgQ2, UQ-pgQ2) particularly beneficial for data skewed toward lowly expressed genes [26].

- Experimental design should prioritize biological replication over sequencing depth when possible, as most tools show markedly improved performance with increased sample size [23].

Future Directions: The field continues to evolve with several promising avenues for addressing these persistent challenges. Deep learning approaches show potential for more accurate imputation of dropout events and distinction of biological versus technical zeros [27]. Multi-omic integration strategies that combine scRNA-seq with epigenetic or proteomic measurements may provide orthogonal evidence to resolve ambiguous expression patterns [25]. As the technology matures, establishing standardized benchmarking frameworks and community-wide acceptance criteria will be essential for validating new computational methods [7].

The optimal approach to differential expression analysis in the presence of technical artifacts ultimately depends on the specific biological question, experimental design, and data characteristics. By understanding the strengths and limitations of available tools, researchers can make informed decisions that maximize the biological insights gained from their single-cell studies.

The advent of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has completely transformed the study of transcriptomes by enabling quantitative analysis of gene expression and transcript variant discovery. A fundamental aspect of comparative RNA-seq experiments involves differential expression analysis, which identifies genes or features whose expression changes significantly across different biological conditions. The statistical frameworks used for this analysis are built upon specific probability distributions that model the unique characteristics of count-based sequencing data. The choice of an appropriate statistical model is crucial, as it directly impacts the reliability and accuracy of identifying true biological signals amid technical variations.

RNA-seq data presents several analytical challenges that distinguish it from other gene expression technologies. The data takes the form of counts of sequencing reads mapped to genomic features, resulting in non-negative integers that exhibit specific mean-variance relationships. Furthermore, different experiments generate varying total numbers of reads, known as sequencing depths, which must be properly accounted for during analysis. Additional complexities include overdispersion (variance exceeding the mean) and the presence of excess zeros in single-cell RNA-seq data. These characteristics have led to the development of three primary classes of statistical approaches: Poisson models, negative binomial models, and non-parametric methods, each with distinct strengths and limitations for handling the intricacies of RNA-seq data.

Mathematical Foundations of Key Distributions

Poisson Distribution

The Poisson distribution is a discrete probability distribution traditionally used to model count data where events occur independently with a known constant rate. For RNA-seq data, this translates to modeling the number of reads mapped to a particular gene. The probability mass function of the Poisson distribution is defined as:

[ p(x; \lambda) = \frac{\lambda^x e^{-\lambda}}{x!} ]

where (x) is the non-negative integer count of reads, and (\lambda > 0) is the rate parameter representing both the mean and variance of the distribution. This equality between mean and variance ((E(X) = Var(X) = \lambda)) is a key characteristic of the Poisson distribution [28].

Early RNA-seq analysis methods employed Poisson models under the assumption that technical replicates could be well characterized by this distribution. However, a significant limitation emerged when analyzing biological replicates: RNA-seq data typically exhibits overdispersion, where the variance exceeds the mean. This occurs because biological samples contain additional sources of variation beyond technical noise. When overdispersion is present but not accounted for, Poisson models tend to overstate significance, leading to inflated false positive rates in differential expression analysis [29] [30].

Negative Binomial Distribution

The negative binomial distribution addresses the limitation of Poisson models by explicitly modeling overdispersed count data. It is a discrete probability distribution that models the number of failures in a sequence of independent trials before a specified number of successes occurs. The probability mass function for the generalized negative binomial distribution is:

[ p(x; r, p) = \frac{\Gamma(x + r)}{x! \Gamma(r)}(1-p)^rp^x ]

where (r \in \mathbb{R}^{\geq 0}) represents the size or dispersion parameter, (p \in [0,1]) is the probability parameter, and (\Gamma) is the gamma function [28].

A particularly useful property of the negative binomial distribution is that it can be derived as a gamma-Poisson mixture distribution. This hierarchical formulation assumes the data follows a Poisson distribution with a mean parameter that itself follows a gamma distribution:

[ \begin{cases} Y \sim \textrm{Pois}(\theta) \ \theta \sim \textrm{gamma}(r, \frac{p}{1-p}) \end{cases} ]

The resulting distribution has a quadratic mean-variance relationship:

[ Var = \mu + \frac{\mu^2}{\phi} ]

where (\mu) is the mean and (\phi) is the dispersion parameter. This relationship allows the negative binomial distribution to effectively model the overdispersion commonly observed in RNA-seq data, making it the foundation for popular tools like edgeR and DESeq [28] [31].

Table 1: Parameterizations of Negative Binomial Distribution

| Index | Gamma Parameterization | NB Parameterization | Variance Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gamma(\left(r, \frac{p}{1 - p}\right)) | NB(\left(r,p\right)) | (\frac{pr}{(1-p)^2}) |

| 2 | Gamma(\left(r, \frac{p}{r} \right)) | NB(\left(r, \frac{p}{p+r}\right)) | (p + \frac{p^2}{r}) |

| 3 | Gamma(\left(r, p \right)) | NB(\left(r, \frac{p}{p+1}\right)) | (p + \frac{p^2}{r}) |

Relationship Between Distributions

The negative binomial and Poisson distributions are connected through a limiting relationship. As the dispersion parameter (\phi) approaches infinity (or equivalently, as (r \to \infty) in certain parameterizations), the negative binomial distribution converges to a Poisson distribution. This relationship is formally expressed as:

[ \lim_{r \to \infty} \textrm{NB}\left( r, \frac{\lambda}{r + \lambda}\right) = \textrm{Pois}(\lambda) ]

This mathematical relationship explains why negative binomial models can handle both overdispersed data (small (\phi)) and approximately Poisson-distributed data (large (\phi)) [28].

For single-cell RNA-seq data, the relationship between mean and variance follows a consistent pattern across genes. Empirical analyses have demonstrated that the variance of gene expression counts can be modeled as:

[ Var = \mu + 0.3725 \mu^2 ]

This corresponds to a negative binomial distribution with dispersion parameter (\phi \approx 2.684), effectively capturing the overdispersion inherent in single-cell data [31].

Figure 1: Relationships between statistical distributions used in RNA-seq analysis. The negative binomial (NB) distribution can be derived as a Gamma-Poisson mixture and converges to Poisson as the dispersion parameter increases. Non-parametric methods provide a robust alternative to these parametric approaches.

Non-Parametric Methods

Theoretical Foundations

Non-parametric methods for RNA-seq differential expression analysis offer a flexible alternative to parametric models by not assuming specific underlying probability distributions for the data. This approach is particularly valuable when distributional assumptions are violated or when parameter estimation is challenging due to small sample sizes or outliers.

The theoretical rationale for non-parametric methods stems from several observed limitations of parametric approaches. Violation of distributional assumptions or poor estimation of parameters in Poisson and negative binomial models often leads to unreliable results [32]. Additionally, parametric methods can be heavily influenced by outliers in the data, which are common in RNA-seq datasets where a small number of highly expressed genes may dominate the read counts in their respective classes [29].

Non-parametric methods finesse these difficulties by relying on data-driven procedures and resampling techniques that eliminate the need for explicit distributional assumptions. These methods are generally more robust across diverse data types and provide more reliable false discovery rate (FDR) estimates when the underlying distributional assumptions of parametric methods are violated [29].

Representative Non-Parametric Approaches

Several non-parametric methods have been specifically developed for RNA-seq differential expression analysis:

LFCseq is a non-parametric approach that uses log fold changes as a differential expression test statistic. For each gene, LFCseq estimates a null probability distribution of count changes from a selected set of genes with similar expression strength. This contrasts with the NOISeq approach, which relies on a null distribution estimated from all genes within an experimental condition regardless of their expression levels. Through extensive simulation studies and real data analysis, LFCseq demonstrates an improved ability to rank differentially expressed genes ahead of non-differentially expressed genes compared to other methods [32].

NPEBseq (Non-Parametric Empirical Bayesian-based Procedure) adopts a Bayesian framework with empirically estimated prior distributions from the data without parametric assumptions. This method uses a Poisson mixture model to estimate prior distributions of read counts, effectively addressing biases caused by the sampling nature of RNA-seq. The approach provides reliable estimation of expression levels for lowly expressed genes that are often problematic for parametric methods. Evaluation on both simulated and publicly available RNA-seq datasets showed improved performance compared to other popular methods, especially for experiments with biological replicates [30].

The Wilcoxon statistic-based method represents another non-parametric approach that uses rank-based procedures to identify differentially expressed features. This method employs a resampling strategy to account for different sequencing depths across experiments, making it applicable to data with various outcome types including quantitative, survival, two-class, or multiple-class outcomes. Simulation studies show that this method is competitive with the best parametric-based statistics when distributional assumptions hold and outperforms them when assumptions are violated [29].

Table 2: Comparison of Non-Parametric Methods for RNA-Seq Analysis

| Method | Test Statistic | Null Distribution Estimation | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| LFCseq | Log fold change | From genes with similar expression strength | Improved ranking of DE genes |

| NPEBseq | Empirical Bayes factor | Poisson mixture model from all data | Handles lowly expressed genes well |

| Wilcoxon-based | Rank-based statistic | Resampling accounting for sequencing depth | Works with multiple outcome types |

| NOISeq | Absolute differences & fold changes | From all genes within a condition | Effective FDR control |

Performance Comparison and Experimental Evaluation

Benchmarking Studies

Comprehensive benchmarking studies have been conducted to evaluate the performance of different statistical distributions and methods for RNA-seq differential expression analysis. These studies typically use both simulated datasets with known ground truth and real biological datasets to assess methods across multiple performance metrics.

In one such evaluation, the non-parametric LFCseq approach was shown to effectively rank differentially expressed genes ahead of non-differentially expressed genes, achieving improved overall performance in differential expression analysis. The method's gene-specific null distribution estimation strategy proved particularly advantageous compared to approaches that estimate null distributions from all genes regardless of expression levels [32].

Another study evaluating NPEBseq demonstrated its superior performance compared to three popular methods (edgeR, DESeq, and NOISeq) across both simulated and publicly available RNA-seq datasets. The method performed well for experiments with or without biological replicates, successfully detecting differential expression at both gene and exon levels [30].

For single-cell RNA-seq data, a recent review classified differential expression analysis approaches into six major classes: generalized linear models, generalized additive models, Hurdle models, mixture models, two-class parametric models, and non-parametric approaches. Each class addresses specific limitations in handling the unique characteristics of single-cell data, including high-level noises, excess overdispersion, low library sizes, sparsity, and a higher proportion of zeros [33].

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

Robust evaluation of differential expression methods typically follows a standardized protocol:

Dataset Selection: Both simulated and real biological datasets are used. Simulation allows controlled assessment with known ground truth, while real data validates biological relevance.

Normalization: All datasets undergo appropriate normalization to account for sequencing depth variations. Common approaches include TMM (trimmed mean of M values) used in edgeR, goodness-of-fit method in PoissonSeq, or quantile normalization.

Method Application: Each evaluated method is applied to the processed datasets using standardized parameters.

Performance Metrics Calculation: Key metrics include:

- Sensitivity and specificity

- False discovery rate (FDR)

- Area under ROC curve

- Consistency across replicates

Biological Validation: For real datasets, results may be validated using qRT-PCR or through consistency with established biological knowledge.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for differential expression analysis. The choice of statistical model depends on data characteristics such as replicate type, presence of outliers, and sample size.

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Distributional Models Across Data Types

| Distribution/Model | Technical Replicates | Biological Replicates | Zero-Inflation | Outlier Robustness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poisson | Excellent (mean = variance) | Poor (underestimates variance) | Poor | Poor |

| Negative Binomial | Good | Excellent (models overdispersion) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Non-parametric | Good | Excellent | Good | Excellent |

| Hurdle Models | Moderate | Good | Excellent | Good |

Practical Implementation and Researcher's Toolkit

Selection Guidelines

Choosing an appropriate statistical model for RNA-seq differential expression analysis depends on multiple factors:

For data with technical replicates only: Poisson models may be sufficient due to the approximate equality of mean and variance in technical replicates [29].

For biological replicates: Negative binomial models are generally preferred due to their ability to account for biological variability through the dispersion parameter [28] [33].

For small sample sizes or suspected outliers: Non-parametric methods provide more robust results as they do not rely on precise parameter estimation or distributional assumptions [32] [29].

For single-cell RNA-seq data with excess zeros: Either specialized negative binomial models that account for zero-inflation or non-parametric approaches are recommended [33].

When RNA spike-ins are available: Models that incorporate spike-in data for technical variability calibration, such as those implemented in DECENT or BASiCS, provide more accurate results [33].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for RNA-Seq Differential Expression Analysis

| Tool Name | Statistical Foundation | Primary Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| edgeR | Negative binomial | Bulk & single-cell RNA-seq | Robust dispersion estimation |

| DESeq/DESeq2 | Negative binomial | Bulk RNA-seq | Size factor normalization |

| LFCseq | Non-parametric | Bulk RNA-seq | Log fold change with local null distribution |

| NPEBseq | Non-parametric empirical Bayes | Bulk RNA-seq | Poisson mixture modeling |

| NOISeq | Non-parametric | Bulk RNA-seq | Noise distribution estimation |

| SAMseq | Non-parametric | Bulk RNA-seq | Wilcoxon statistic with resampling |

| MAST | Hurdle model | Single-cell RNA-seq | Modeling of zero-inflation |

| D3E | Non-parametric | Single-cell RNA-seq | Cramer-von Mises distance |

| Senp1-IN-3 | Senp1-IN-3, MF:C36H58N2O4, MW:582.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| PROTAC BRD4 Degrader-12 | PROTAC BRD4 Degrader-12, MF:C62H77F2N9O12S4, MW:1306.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The choice of statistical distribution for RNA-seq differential expression analysis significantly impacts the identification of biologically relevant genes. Negative binomial models currently represent the most widely adopted approach, particularly for bulk RNA-seq data with biological replicates, due to their effective handling of overdispersion. However, non-parametric methods offer robust alternatives that perform well across diverse data types, especially when distributional assumptions are violated or when analyzing complex experimental designs with multiple outcome types.

As RNA-seq technologies continue to evolve, particularly with the rising prominence of single-cell sequencing, statistical methods must adapt to address new challenges including increased sparsity, amplified technical noise, and more complex experimental designs. Future methodological developments will likely focus on integrating multiple distributional approaches, enhancing computational efficiency for massive datasets, and providing more nuanced interpretations of differential expression in the context of biological networks and pathways.

Regardless of the specific method chosen, careful attention to experimental design, appropriate normalization, and consideration of data-specific characteristics remain essential for generating biologically meaningful results from RNA-seq differential expression analyses.

Normalization serves as a critical preprocessing step in RNA-sequencing data analysis, directly influencing the accuracy and reliability of downstream differential expression results. This review objectively compares two widely adopted between-sample normalization methods—the Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) from the edgeR package and the Relative Log Expression (RLE) from the DESeq2 package—within the broader context of evaluating differential expression analysis tools. We examine their underlying assumptions, computational methodologies, and performance characteristics based on experimental data from published benchmarks. Evidence from multiple studies indicates that while TMM and RLE share core assumptions and often produce similar results, their subtle differences can impact downstream analyses, including differential expression detection and pathway analysis. This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a structured comparison to inform their analytical choices.

In RNA-sequencing analysis, normalization corrects for technical variations to ensure that observed differences in gene expression reflect true biological signals rather than artifacts of the experimental process. Technical biases such as sequencing depth (the total number of reads per sample), library composition (the relative abundance of different RNA species), and gene length must be accounted for to enable valid comparisons between samples [34] [35]. Without proper normalization, differential expression analysis can be skewed, leading to elevated false discovery rates or reduced power to detect true differences [36].

The Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) and Relative Log Expression (RLE) represent two prominent between-sample normalization methods embedded within popular differential expression analysis packages edgeR and DESeq2, respectively [37] [36]. Both methods operate under a key biological assumption that the majority of genes are not differentially expressed across the conditions being compared [37] [38]. This review synthesizes evidence from comparative studies to evaluate how these normalization techniques perform under various experimental conditions and how they influence subsequent biological interpretations.

Methodological Foundations

The Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM)

The TMM normalization method, introduced by Robinson and Oshlack, estimates scaling factors between samples to account for differences in RNA production that are not attributable to true biological changes in gene expression [36]. The method operates by designating one sample as a reference and then comparing all other test samples against this reference.

The computational procedure involves the following steps:

- Calculate M-values and A-values: For each gene g in a test sample compared to the reference sample, the log-fold-change (M-value) and average log-expression (A-value) are computed:

- M-value = logâ‚‚( (X{g,test}/N{test}) / (X{g,ref}/N{ref}) )

- A-value = ½ * log₂( (X{g,test}/N{test}) * (X{g,ref}/N{ref}) ) Here, X represents the count and N represents the library size.

- Trim extreme values: To ensure robustness, the method trims genes with extreme M-values (log-fold-changes) and extreme A-values (expression levels) by a default of 30% from both ends [36] [38].

- Compute the weighted average: The TMM factor for the test sample is calculated as the weighted mean of the remaining M-values. The weights are derived from the inverse of the approximate asymptotic variances, giving more influence to genes with higher counts and lower expected variance [36].

- Adjust library sizes: The computed TMM factor is used to adjust the original library sizes, creating an "effective library size" for use in downstream differential expression analysis [38].

The Relative Log Expression (RLE)

The RLE normalization method, developed by Anders and Huber and used in DESeq2, relies on the median ratio of gene counts between samples [37] [38]. Its procedure is as follows:

- Compute a pseudo-reference sample: For each gene, its geometric mean across all samples is calculated.

- Calculate gene-wise ratios: For every gene in each sample, the ratio of its count to the pseudo-reference count is computed.

- Determine the scale factor: The scale factor for a given sample is taken as the median of all gene-wise ratios for that sample [37] [38]. This step directly utilizes the core assumption that most genes are not differentially expressed, and thus the median ratio should represent the technical scaling factor.

- Normalize counts: Finally, all counts in a sample are divided by its calculated scale factor to obtain normalized expression values.

Table: Summary of Core Methodologies for TMM and RLE Normalization

| Feature | TMM (edgeR) | RLE (DESeq2) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Assumption | Majority of genes are not DE | Majority of genes are not DE |

| Primary Statistic | Trimmed mean of M-values (log-fold-changes) | Median of ratios to a pseudo-reference |

| Handling of Extreme Values | Trims by M-values and A-values | Uses the median, which is inherently robust |

| Output | Normalization factor for effective library size | Scale factor for direct count adjustment |

| Implementation | calcNormFactors in edgeR |

estimateSizeFactorsForMatrix in DESeq2 |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points for both normalization methods:

Diagram: Workflow comparison of TMM and RLE normalization methods. Both methods start from a raw count matrix and operate under the core assumption that most genes are not differentially expressed (DE), but they diverge in their computational approaches to estimate scaling factors.

Experimental Comparisons and Performance Benchmarks

Protocol for Benchmarking Studies

Benchmarking studies typically employ a combination of real and simulated RNA-seq datasets to evaluate normalization performance. A standard protocol involves:

- Dataset Selection: Studies often use a real RNA-seq dataset with biological replicates as a ground truth. A common example is a tomato fruit set dataset comprising 34,675 genes across 9 samples (3 stages with 3 replicates each) [39] [40]. Simulated datasets are also generated where the true differential expression status of each gene is known, allowing for precise calculation of false discovery rates (FDR) and true positive rates [40].

- Application of Normalization Methods: Different normalization methods (TMM, RLE, MRN, etc.) are applied to the selected dataset(s) using their respective standard implementations in R/Bioconductor (e.g.,

calcNormFactorsfor TMM in edgeR andestimateSizeFactorsForMatrixfor RLE in DESeq2) [39]. - Downstream Analysis: Differential expression analysis is performed on the normalized data using the corresponding statistical frameworks (edgeR for TMM and DESeq2 for RLE).

- Performance Metrics: The outcomes are evaluated based on metrics such as:

Comparative Performance Data

Empirical comparisons consistently demonstrate that TMM and RLE normalization methods perform similarly in many contexts and often cluster together in terms of their downstream outcomes.

Table: Summary of Comparative Performance from Published Studies

| Study Context | Key Finding | Implication for Downstream Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Tomato Fruit Set RNA-Seq Data [39] [42] | TMM factors showed no significant correlation with library size, while RLE factors exhibited a positive correlation. | Choice of method may influence results when sample library sizes vary considerably and this variation is confounded with experimental conditions. |

| Simulated & Real Data Benchmark [40] | Methods like TMM and RLE showed similar behavior, forming a distinct group from within-sample methods (e.g., TPM, FPKM). Only ~50% of significant DE genes were common across methods. | Normalization choice significantly influences the final DE gene list, highlighting the need for careful method selection. |

| Personalized Metabolic Model Building [41] | RLE, TMM, and GeTMM produced condition-specific metabolic models with low variability in the number of active reactions, unlike TPM/FPKM. | Between-sample methods like TMM and RLE provide more consistent and stable inputs for complex downstream analyses like metabolic network reconstruction. |

| Hypothetical Two-Condition Test [38] | Both TMM and RLE correctly identified that only 25 of 50 transcripts were DE in a controlled scenario, whereas analysis with no normalization incorrectly called all 50 as DE. | Both methods effectively control for composition bias and are robust for simple experimental designs. |

A study mapping normalized data to genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) for Alzheimer's disease and lung adenocarcinoma found that RLE, TMM, and GeTMM enabled the generation of more consistent metabolic models with lower variability across samples compared to within-sample methods like TPM and FPKM [41]. Furthermore, the models derived from RLE and TMM normalized data more accurately captured disease-associated genes, with average accuracy of approximately 0.80 for Alzheimer's disease and 0.67 for lung adenocarcinoma [41].

Successful implementation and benchmarking of RNA-seq normalization methods require a suite of software tools and data resources.

Table: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool or Resource | Function/Brief Explanation | Relevant Method |

|---|---|---|

| edgeR [38] | A Bioconductor R package for differential analysis of RNA-seq data. It implements the TMM normalization. | TMM |

| DESeq2 [37] | A Bioconductor R package for differential gene expression analysis. It uses the RLE median-ratio method for normalization. | RLE |

| R/Bioconductor [39] | An open-source computing environment providing a comprehensive collection of packages for the analysis of high-throughput genomic data. | General Platform |

| Tomato Fruit Set Dataset [39] | A published RNA-seq dataset (34,675 genes x 9 samples) frequently used as a real-world test case for method comparisons. | Benchmarking |

| Simulated Data [40] | Computer-generated RNA-seq data where the true differential expression status is known, allowing for precise estimation of false discovery rates. | Benchmarking |

| iMAT/INIT Algorithms [41] | Algorithms used to build condition-specific genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) from transcriptome data, used to assess functional impact of normalization. | Downstream Validation |

Impact on Downstream Analysis and Biological Interpretation

The choice of normalization method can profoundly affect the biological conclusions drawn from an RNA-seq study. Research indicates that the differences between TMM and RLE, while often subtle, can be consequential.

Differential Expression Lists: A comparative analysis revealed that only about 50% of genes identified as significantly differentially expressed were common when different normalization methods were applied to the same dataset [40]. This lack of consensus underscores that the normalization step is a significant source of variation in DE analysis, potentially more influential than the choice of the downstream statistical test itself.

Stability and Variability: In studies requiring the integration of transcriptomic data into genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), between-sample normalization methods like TMM and RLE produced models with significantly lower variability in the number of active reactions compared to within-sample methods [41]. This stability is crucial for obtaining reproducible and reliable mechanistic insights.

Functional Enrichment and Pathway Analysis: The interpretation of PCA models and subsequent pathway enrichment analyses has been shown to depend heavily on the normalization method used [43]. Different normalization techniques can alter gene ranking and correlation patterns, leading to divergent biological narratives regarding the most affected pathways and functions.

The following diagram summarizes the cascading impact of normalization choice on various stages of a typical RNA-seq data analysis workflow:

Diagram: Cascading impact of normalization on downstream analysis. The choice between TMM and RLE normalization can influence the list of differentially expressed genes, the outcome of multivariate analyses like PCA, the results of functional enrichment, and ultimately, the biological interpretation. Key supporting findings from the literature are highlighted in red.

Based on the collective evidence from published benchmarks and methodological reviews, both TMM and RLE are robust and effective normalization methods for RNA-seq data, particularly suited for differential expression analysis. Their shared foundation—the assumption that most genes are not differentially expressed—makes them more appropriate for between-sample comparisons than within-sample methods like RPKM/FPKM or TPM.

While TMM and RLE often yield highly concordant results, especially in simple two-condition experiments, discrepancies can arise in more complex designs. These differences can propagate through the analysis pipeline, affecting the final list of candidate genes and the biological pathways deemed significant. Therefore, the choice between them should not be considered automatic. Researchers are encouraged to understand the specific characteristics of their dataset, such as the presence of extreme library size differences or extensive global transcriptional shifts, which might favor one method over the other. When conclusions are critical, conducting analyses with both methods and assessing the robustness of key findings can be a prudent strategy. Ultimately, the selection of a normalization procedure is a foundational decision that significantly influences the analytical landscape of an RNA-seq study.

DGE Tool Arsenal: Methodologies, Applications, and Experimental Designs