A Comprehensive Guide to Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Protocols: From Experimental Design to Data Validation

This article provides a complete roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals designing single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) experiments. It covers foundational principles, from understanding cellular heterogeneity and the critical importance of Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) to selecting the appropriate isolation method for your sample type. The guide details step-by-step methodological workflows for both high- and low-throughput platforms, offers solutions for common pitfalls in tissue dissociation and batch effects, and outlines essential techniques for validating scRNA-seq findings through spatial transcriptomics, protein-level assays, and functional studies. By integrating established best practices with the latest advancements, this resource aims to empower scientists to generate robust, reproducible, and biologically insightful single-cell data.

A Comprehensive Guide to Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Protocols: From Experimental Design to Data Validation

Abstract

This article provides a complete roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals designing single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) experiments. It covers foundational principles, from understanding cellular heterogeneity and the critical importance of Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) to selecting the appropriate isolation method for your sample type. The guide details step-by-step methodological workflows for both high- and low-throughput platforms, offers solutions for common pitfalls in tissue dissociation and batch effects, and outlines essential techniques for validating scRNA-seq findings through spatial transcriptomics, protein-level assays, and functional studies. By integrating established best practices with the latest advancements, this resource aims to empower scientists to generate robust, reproducible, and biologically insightful single-cell data.

Understanding Single-Cell RNA Sequencing: Core Principles and Experimental Foundations

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has emerged as a transformative technology that enables the profiling of gene expression at the ultimate level of biological resolution: the individual cell. Since its conceptual and technical breakthrough in 2009, scRNA-seq has fundamentally altered our ability to dissect cellular heterogeneity, revealing complex cellular landscapes that were previously obscured by bulk sequencing approaches [1] [2]. While traditional bulk RNA sequencing measures the average expression of genes across thousands to millions of cells, scRNA-seq captures the unique transcriptional profile of each individual cell, allowing researchers to identify rare cell populations, characterize novel cell types, and understand regulatory relationships between genes in a way that was never before possible [3].

The fundamental limitation of bulk sequencing lies in its inherent averaging effect. When tissue samples are processed as bulk populations, the resulting transcriptome represents a composite signal from all constituent cells, effectively masking the true biological diversity present within the sample [3]. This averaging can obscure critical biological phenomena, including rare but functionally important cell populations, continuous transitional states in developmental processes, and stochastic expression variations that may drive cell fate decisions [2]. scRNA-seq overcomes these limitations by separately profiling the transcriptomes of individual cells, enabling the direct observation and quantification of cellular heterogeneity within seemingly homogeneous populations [1].

Key Technological Advances Enabling scRNA-seq

Evolution of scRNA-seq Platforms and Methods

The rapid advancement of scRNA-seq has been driven by continuous improvements in both wet-lab methodologies and computational analytics. The core procedure involves isolating single cells, converting their RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA), amplifying the cDNA, and preparing sequencing libraries [1]. Early methods utilized limiting dilution, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), or micromanipulation for cell isolation, but these approaches were limited in throughput and efficiency [3]. The field has since evolved toward high-throughput platforms capable of processing tens of thousands of cells in a single experiment, with dramatic reductions in cost and increased automation [1].

Two primary amplification strategies have been developed for scRNA-seq: polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methods (e.g., SMART-seq2, Fluidigm C1, Drop-seq, 10x Genomics) and in vitro transcription (IVT)-based methods (e.g., CEL-seq, MARS-Seq) [1]. PCR amplification represents a non-linear amplification process that can generate sufficient material for sequencing from the minute quantities of RNA present in a single cell. The introduction of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) has been particularly valuable for addressing amplification biases, as these random barcodes label individual mRNA molecules during reverse transcription, enabling accurate quantification by effectively distinguishing between biological duplicates and PCR duplicates [1] [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Major scRNA-seq Technological Approaches

| Method Type | Examples | Amplification Strategy | Throughput | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plate-based | SMART-seq2, Fluidigm C1 | PCR-based (mostly) | Low to medium (96-800 cells) | Full-length transcript coverage; good sensitivity | Lower throughput; higher cost per cell |

| Droplet-based | 10x Genomics, inDrop, Drop-seq | PCR-based | High (thousands to millions of cells) | High throughput; cost-effective | 3' or 5' end counting only; shorter reads |

| Nanowell-based | Seq-Well, Microwell-seq | PCR-based | High (thousands to tens of thousands) | Portable; cost-effective | Lower mRNA capture efficiency |

| IVT-based | CEL-seq, MARS-seq | Linear amplification (IVT) | Medium to high | Better quantitative accuracy | 3' bias; more complex protocol |

Single-Cell Isolation Techniques

The initial step of isolating viable single cells is critical for successful scRNA-seq experiments. The choice of isolation method depends on the tissue type, cell properties, and research objectives [1]. The most common techniques include:

- Limiting Dilution: A traditional method where cell suspensions are diluted to statistically distribute individual cells into multi-well plates [3]. While simple and requiring no specialized equipment, this approach is inefficient with approximately one-third of wells typically containing cells when diluting to 0.5 cells per aliquot [3].

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): Currently the most widely used method, FACS enables the isolation of highly purified single cells based on fluorescently labeled antibodies targeting specific surface markers [3]. This method offers high purity and the ability to select specific cell populations but requires large starting cell numbers and may induce cellular stress [3].

- Microfluidic Technologies: These systems, including the commercial Fluidigm C1 platform, utilize microscale chambers for automated cell processing with minimal reagent volumes [3]. Microfluidics offers improved precision and reduced contamination risk but may be limited by cell size restrictions and lower throughput compared to newer methods [3].

- Droplet-Based Microfluidics: High-throughput platforms like the 10x Genomics Chromium system encapsulate individual cells in nanoliter-sized droplets containing barcoded beads [1]. This approach enables massive parallel processing of thousands to millions of cells at reduced cost, making it ideal for comprehensive atlas projects and detecting rare cell types [1] [2].

A critical consideration in single-cell isolation is the potential for inducing "artificial transcriptional stress responses" during tissue dissociation [1]. Studies have demonstrated that dissociation protocols, particularly those employing proteases at 37°C, can artificially alter transcriptional patterns and lead to inaccurate cell type identification [1]. To minimize these technical artifacts, dissociation at lower temperatures (e.g., 4°C) or utilization of single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) has been recommended, especially for sensitive tissues like brain [1].

Computational Analysis of scRNA-seq Data

Standard Bioinformatics Pipeline

The analysis of scRNA-seq data presents unique computational challenges due to its high dimensionality, technical noise, and sparsity [4] [3]. A standard analytical workflow encompasses multiple processing steps:

Quality Control and Filtering: The initial critical step involves removing low-quality cells that could compromise downstream analyses. Quality control typically examines three key metrics: the number of counts per barcode (count depth), the number of genes per barcode, and the fraction of mitochondrial counts per barcode [4]. Cells with low counts/genes may represent broken cells or empty droplets, while those with unexpectedly high counts may be doublets (multiple cells). High mitochondrial fractions often indicate compromised cell viability [4]. These metrics should be considered jointly rather than in isolation to avoid unintentionally filtering out biologically relevant cell populations [4].

Normalization and Batch Effect Correction: Normalization addresses differences in sequencing depth between cells, typically by scaling counts to counts per million (CPM) or similar metrics [5]. As datasets often combine cells from multiple experiments, batch effect correction methods are essential to remove technical variations unrelated to biological signals, enabling valid comparisons across datasets [4].

Feature Selection and Dimensionality Reduction: scRNA-seq data typically measure expression of thousands of genes across thousands of cells, creating a high-dimensional space. Dimensionality reduction techniques like principal component analysis (PCA) identify the most informative sources of variation [5]. Further non-linear methods such as t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) project cells into 2D or 3D spaces for visualization [4] [6].

Clustering and Cell Type Identification: Unsupervised clustering algorithms (e.g., Leiden, Louvain) group cells based on transcriptional similarity, revealing distinct cell populations [5]. Cluster identity is then inferred through differential expression analysis, comparing each cluster against others to find marker genes that can be matched to known cell types using reference databases [4].

Trajectory Inference: For developing systems or continuous biological processes, trajectory inference methods (pseudotemporal ordering) reconstruct the dynamic transitions cells undergo, such as differentiation pathways, by ordering cells along a continuum based on transcriptional similarity [2].

Comparing and Integrating scRNA-seq Datasets

As the number of publicly available scRNA-seq datasets grows, methods for comparing and integrating them have become increasingly important. Two main approaches exist for cross-dataset analysis [7]:

Label-Centric Comparison: This approach focuses on identifying equivalent cell types/states across datasets by comparing individual cells or groups of cells. Methods like scmap project cells from a new experiment onto an annotated reference dataset, similar to BLAST for sequence data, enabling rapid annotation and identification of novel cell states [7].

Cross-Dataset Normalization: These methods computationally remove experiment-specific technical and biological effects so that data from multiple experiments can be combined and analyzed jointly. This approach facilitates the identification of rare cell types that may be too sparsely sampled in individual datasets to be reliably detected [7].

Newer tools like scCompare utilize correlation-based mapping to transfer phenotypic identities from a reference dataset to a query dataset, with statistical thresholds to identify cells distinct from known phenotypes, enabling novel cell type discovery [5].

Applications: Revealing Biological Heterogeneity

Characterizing Cellular Diversity in Tissues and Organs

One of the most significant applications of scRNA-seq has been the comprehensive cataloging of cell types across tissues and organisms through atlas projects like the Human Cell Atlas, Tabula Muris, and Tabula Sapiens [1] [8]. These initiatives aim to create reference maps of all human cells, providing foundational resources for understanding healthy physiology and disease mechanisms. For example, the Tabula Sapiens has collected scRNA-seq data from 24 tissues across multiple donors, enabling cross-tissue comparisons and the identification of tissue-specific and shared cell populations [5].

In immunology, scRNA-seq has revealed unprecedented complexity within immune cell populations, identifying novel subsets of T cells with distinct functional specializations and activation states [6] [2]. Similarly, in neuroscience, scRNA-seq has transformed our understanding of brain complexity by characterizing dozens of neuronal and glial cell types that were previously indistinguishable [1] [3].

Unraveling Disease Mechanisms

In cancer research, scRNA-seq has demonstrated exceptional utility for characterizing tumor heterogeneity, the tumor microenvironment, and cellular mechanisms underlying treatment resistance [2] [3]. By profiling individual cells within tumors, researchers have identified rare subpopulations of therapy-resistant cells that persist after treatment and eventually drive relapse [3]. scRNA-seq of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) has also provided insights into metastasis mechanisms through minimally invasive liquid biopsies [3].

Protocols have been developed for applying scRNA-seq to challenging clinical samples, including bladder Ewing sarcoma, demonstrating the feasibility of generating high-quality data from difficult tumor tissues [9] [10]. Spatial transcriptomics technologies now complement scRNA-seq by preserving the spatial context of gene expression, bridging the gap between cellular heterogeneity and tissue architecture [9].

Tracing Developmental Trajectories

scRNA-seq is ideally suited for studying dynamic biological processes such as embryonic development, tissue regeneration, and cell differentiation [2]. By capturing cells at different stages along a developmental continuum, researchers can reconstruct lineage relationships and identify key transcriptional regulators driving fate decisions [2]. For example, studies of cardiomyocyte differentiation from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) using scRNA-seq have revealed how different protocols generate distinct cellular outcomes, enabling optimization of differentiation methods for regenerative medicine applications [5].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Isolation Reagents | Enzymatic dissociation cocktails (collagenase, trypsin), FACS antibodies, Dead cell removal kits | Tissue dissociation and viable cell isolation | Optimization needed for each tissue type; minimize stress responses |

| Library Preparation Kits | 10x Genomics Chromium, SMART-seq kits, Fluidigm C1 reagents | Single-cell capture, barcoding, and library construction | Throughput, cost, and transcript coverage vary by platform |

| Reverse Transcriptase Enzymes | Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (MMLV) RT with template-switching activity | cDNA synthesis from single-cell RNA | High efficiency needed due to low mRNA input |

| Amplification Reagents | PCR master mixes, In vitro transcription kits | cDNA amplification for sequencing library construction | Choice affects 3' bias and quantitative accuracy |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Barcoded oligonucleotides | Molecular counting and elimination of PCR duplicates | Essential for accurate quantification |

| Quality Control Assays | Bioanalyzer tapes, Fluorescent cell viability dyes, Ribonuclease inhibitors | Assessment of RNA quality, cell viability, and sample integrity | Critical for preventing experimental failure |

The expansion of scRNA-seq has been accompanied by the development of specialized databases and resources that facilitate data sharing, exploration, and reuse:

- Single Cell Portal (Broad Institute): A specialized platform for sharing and exploring scRNA-seq datasets with built-in visualization tools [8].

- CZ Cell x Gene Discover: Hosts over 500 scRNA-seq datasets with intuitive exploration capabilities through an open-source data exploration tool [8].

- Single Cell Expression Atlas (EMBL-EBI): Provides consistently processed and annotated scRNA-seq datasets across multiple organisms [8].

- PanglaoDB: A curated database of scRNA-seq datasets with annotated marker genes and automated cell type annotations [8].

- scRNAseq Package (Bioconductor): Provides programmatic access to dozens of curated scRNA-seq datasets in standardized formats for easy integration with analytical workflows [8].

These resources have become invaluable for researchers seeking to contextualize their findings within larger biological frameworks, generate hypotheses, and conduct meta-analyses across multiple studies [8].

Single-cell RNA sequencing has fundamentally transformed our approach to studying complex biological systems by providing unprecedented resolution into cellular heterogeneity. As the technologies continue to mature with improvements in throughput, sensitivity, and spatial context preservation, and as computational methods become more sophisticated and standardized, scRNA-seq is poised to become an increasingly integral component of both basic biological research and clinical applications. The ability to deconvolute tissue complexity, identify rare cell populations, track developmental trajectories, and understand disease mechanisms at single-cell resolution will continue to drive discoveries across fields from immunology to cancer biology to regenerative medicine, firmly establishing scRNA-seq as an essential tool for modern biological research.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized transcriptomic research by enabling the analysis of gene expression patterns at the level of the individual cell. This powerful genomic approach provides an unprecedented view of cellular heterogeneity and function within complex biological systems, allowing researchers to study cellular responses, identify rare cell populations, and trace developmental lineages in a way that was not possible with bulk RNA-seq methods [2]. The fundamental difference between these approaches lies in whether each sequencing library reflects an individual cell or an averaged group of cells, with scRNA-seq requiring specialized methodologies to overcome challenges such as scarce transcripts, inefficient mRNA capture, and amplification biases [11]. This protocol provides a comprehensive overview of the complete scRNA-seq workflow, from sample preparation through data analysis, framed within the context of single-cell RNA sequencing protocol for isolates research.

scRNA-seq Workflow: A Step-by-Step Guide

Sample Preparation and Single-Cell Isolation

The initial and most critical step in conducting scRNA-seq is the effective isolation of viable, single cells from the tissue of interest. The quality of this starting material profoundly impacts all subsequent steps and the ultimate quality of the data [2]. For human bladder Ewing sarcoma tissue, as an example, this begins with generating highly viable single-cell suspensions while maintaining RNA integrity [9] [10]. The choice of isolation strategy depends on the tissue type, experimental goals, and available resources.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Single-Cell Isolation Methods

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FACS [11] | Fluorescent-activated cell sorting | High precision, ability to sort based on markers | Higher cost, potentially lower viability post-sorting | Medium |

| Droplet-based [12] | Microfluidic partitioning of cells | High-throughput, cost-effective per cell | Requires specialized equipment | High (thousands to millions of cells) |

| Microfluidic devices (e.g., Fluidigm C1) [2] | Microfluidic chip capture | Precise cell handling, integrated workflow | Lower throughput, higher cost per cell | Low to medium |

| Laser capture microdissection | Laser-based isolation | Spatial context preservation | Technically challenging, low throughput | Low |

| Split-pooling with combinatorial indexing [2] | Sequential barcoding in plates | Avoids specialized equipment, scalable to millions of cells | Complex workflow, lower efficiency | Very high |

Emerging methodologies such as single-nuclei RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) offer advantages when tissue dissociation is challenging, or when working with frozen or fragile samples [2] [11]. Similarly, 'split-pooling' scRNA-seq approaches based on combinatorial indexing of single cells allow for the processing of large sample sizes (up to millions of cells) without requiring expensive microfluidic hardware [2].

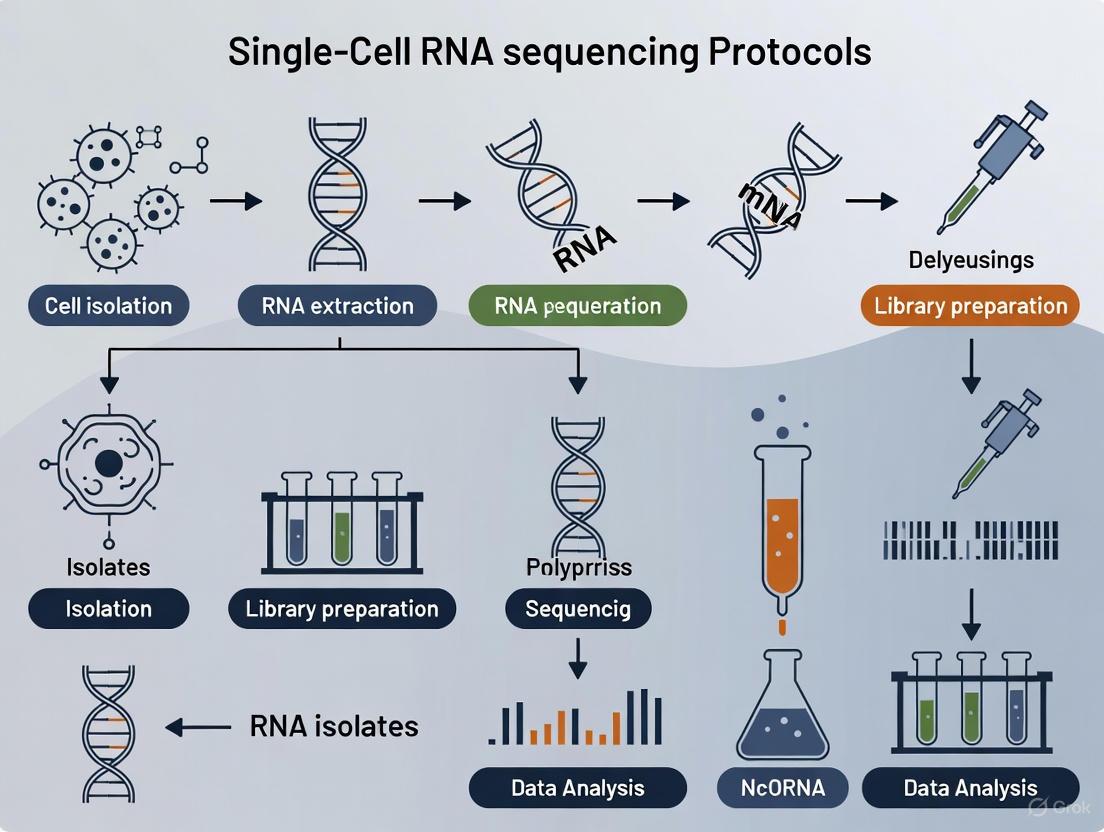

Figure 1: Sample Preparation and Single-Cell Isolation Workflow

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Once high-quality single-cell suspensions are obtained, the next critical phase involves preparing sequencing libraries. This process converts the minute amounts of RNA from individual cells into a format compatible with next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms. The fundamental steps include cell lysis, reverse transcription, cDNA amplification, and the addition of sequencing adapters [2].

A groundbreaking innovation in this field has been the development of droplet-based partitioning systems, such as the 10x Genomics Chromium platform. This technology combines single cells, reverse transcription reagents, and barcoded Gel Beads with oil on a microfluidic chip to form reaction vesicles called GEMs (Gel Beads-in-emulsion). Each functional GEM contains a single cell, a single Gel Bead, and reverse transcription reagents. Within each GEM, the cell is lysed, the Gel Bead dissolves to release barcoded oligonucleotides, and reverse transcription of polyadenylated mRNA occurs [12]. Crucially, all cDNAs originating from the same cell share an identical barcode, enabling bioinformatic mapping of sequencing reads back to their cell of origin after sequencing [12].

Table 2: Comparison of scRNA-seq Protocols and Technologies

| Protocol | Isolation Strategy | Transcript Coverage | UMI | Amplification Method | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium [12] | Droplet-based | 3'- or 5'-end counting | Yes | PCR | High-throughput cellular heterogeneity studies |

| Smart-Seq2 [11] | FACS | Full-length | No | PCR | Detection of low-abundance transcripts, isoform analysis |

| Drop-Seq [11] | Droplet-based | 3'-end | Yes | PCR | High-throughput, low cost per cell |

| CEL-Seq2 [11] | FACS | 3'-only | Yes | IVT | Reduced amplification bias |

| MATQ-Seq [11] | Droplet-based | Full-length | Yes | PCR | Accurate transcript quantification, variant detection |

| inDrop [11] | Droplet-based | 3'-end | Yes | IVT | Low cost per cell, efficient barcode capture |

The latest technological advancements include GEM-X technology, which generates twice as many GEMs at smaller volumes, reducing multiplet rates two-fold and increasing throughput capabilities. Modern platforms can process 80,000 to 960,000 cells per kit in a single instrument run with up to 80% cell recovery efficiency [12]. For enhanced sample compatibility, Flex assays enable profiling of fresh, frozen, and fixed samples, including FFPE tissues and fixed whole blood, providing crucial flexibility for clinical and longitudinal studies [12].

Figure 2: Library Preparation and Sequencing Workflow

Data Processing and Analysis

The transformation of raw sequencing data into biologically meaningful information requires a sophisticated computational workflow. After sequencing, the barcoded data must be processed to generate gene expression matrices and undergo multiple analytical steps to extract insights into cellular heterogeneity and function.

The initial computational processing typically involves tools like Cell Ranger (10x Genomics), which demultiplexes the sequencing data, aligns reads to a reference genome, and generates a feature-barcode matrix containing counts of RNA transcripts for each gene in each cell [12]. This raw count matrix, a numeric matrix of genes × cells, serves as the fundamental input for all subsequent analyses [13].

A critical preprocessing challenge arises from the nature of scRNA-seq data, which is inherently heteroskedastic—counts for highly expressed genes naturally vary more than for lowly expressed genes [13]. Various transformation approaches have been developed to address this issue:

- Delta method-based transformations: Include the shifted logarithm (e.g., log(y/s + yâ‚€)) and the inverse hyperbolic sine (acosh) transformation, which aim to stabilize variance across the dynamic range of expression [13]

- Pearson residuals: Implemented in tools like sctransform, these residuals are calculated as (ygc - μ̂gc)/√(μ̂gc + α̂g μ̂_gc²) after fitting a gamma-Poisson generalized linear model [13]

- Latent expression inference: Methods like Sanity and Dino that infer parameters of generative models to estimate latent gene expression values [13]

- Count-based factor analysis: Approaches like GLM PCA and NewWave that directly model count distributions to produce low-dimensional representations [13]

Benchmark studies have shown that a rather simple approach—the logarithm with a pseudo-count followed by principal-component analysis—often performs as well or better than more sophisticated alternatives [13].

Figure 3: Data Processing and Analysis Workflow

Essential Reagents and Computational Tools

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for scRNA-seq Workflows

| Reagent/Category | Function | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Viability Kits | Assess viability of single-cell suspensions | Fluorescent live/dead stains, trypan blue; aim for >80% viability |

| Dissociation Enzymes | Tissue-specific digestion to single cells | Collagenase, trypsin, liberase; optimized for tissue type |

| Barcoded Gel Beads | Cell barcoding and mRNA capture | 10x Genomics Barcoded Gel Beads with oligo-dT primers |

| Reverse Transcription Mix | cDNA synthesis from captured mRNA | Includes reverse transcriptase, nucleotides, buffers |

| Partitioning Oil & Chips | Microfluidic formation of GEMs | 10x Genomics Partitioning Oil & Microfluidic Chips |

| Library Preparation Kits | Preparation of sequencing-ready libraries | Include enzymes for fragmentation, adapter ligation, and amplification |

| Cleanup Beads | Size selection and purification | SPRIselect, AMPure XP beads for cDNA and library cleanup |

| UMI Reagents | Unique Molecular Identifiers for digital counting | Molecular barcodes to distinguish biological from technical variation |

Computational Tools for scRNA-seq Analysis

The analysis of scRNA-seq data relies on a robust ecosystem of computational tools and pipelines. The choice of tools depends on the experimental design, computational resources, and biological questions being addressed.

- Processing Pipelines: Cell Ranger (10x Genomics) provides a comprehensive solution for processing raw sequencing data into gene-cell count matrices, performing secondary analysis including clustering, and generating preliminary visualizations [12]

- Quality Control: Tools like FastQC for sequencing quality assessment, and scRNA-seq specific metrics including genes per cell, UMIs per cell, and mitochondrial percentage

- Primary Analysis Platforms: Seurat and Scanpy represent two of the most widely used frameworks for comprehensive scRNA-seq analysis, providing functions for normalization, feature selection, dimensionality reduction, clustering, and differential expression [9] [13]

- Visualization Software: Loupe Browser (10x Genomics) enables interactive exploration of scRNA-seq data without requiring programming expertise [12]

- Specialized Applications: Monocle and Slingshot for trajectory inference; CellPhoneDB for cell-cell communication analysis; and SCENIC for gene regulatory network inference

For researchers seeking to contextualize their findings within existing knowledge, numerous public databases host scRNA-seq datasets, including GEO/SRA, Single Cell Expression Atlas (EMBL), Single Cell Portal (Broad Institute), CZ Cell x Gene Discover, and the scRNAseq package on Bioconductor, which provides curated datasets as SingleCellExperiment objects for easy integration with analysis pipelines [8].

The scRNA-seq workflow represents a transformative methodology for investigating cellular heterogeneity and function at unprecedented resolution. From careful sample preparation through sophisticated computational analysis, each step in the process contributes to the generation of high-quality data capable of revealing novel biological insights. As the technology continues to evolve, with improvements in throughput, sensitivity, and compatibility with diverse sample types, scRNA-seq is poised to drive further discoveries across biomedical research, drug discovery, and clinical applications. The integration of spatial transcriptomics methods, as demonstrated in bladder Ewing sarcoma protocols [9] [10], further enhances this powerful approach by adding crucial spatial context to single-cell gene expression profiles. For researchers embarking on scRNA-seq studies, attention to protocol details at each stage—from cell isolation to data transformation—is essential for obtaining reliable, interpretable results that advance our understanding of cellular biology in health and disease.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling the dissection of gene expression at an unprecedented resolution, revealing cellular heterogeneity, identifying rare cell types, and illuminating developmental trajectories that are obscured in bulk sequencing approaches [1] [14]. The fundamental principle underlying all scRNA-seq technologies is the conversion of RNA from individual cells into cDNA libraries that can be sequenced, but the methodological approaches diverge significantly in how they capture transcript information [1] [15]. Since the first conceptual breakthrough in 2009, the field has rapidly evolved into two primary technological paradigms: full-length transcript protocols that sequence complete mRNA molecules, and 3' or 5' end counting protocols that focus on the terminal regions of transcripts [1] [15]. The choice between these pathways represents a critical decision point for researchers, with significant implications for experimental design, data quality, analytical possibilities, and resource allocation. This application note provides a comprehensive comparison of these approaches, offering structured guidance for researchers navigating this complex technological landscape within the context of a broader thesis on single-cell RNA sequencing protocols for isolates research.

Full-Length Transcript Sequencing Protocols

Full-length scRNA-seq methods are designed to capture and sequence complete mRNA molecules from the 5' cap to the 3' poly-A tail, preserving the entire transcript sequence information. These protocols typically employ oligo-dT priming to target the poly-A tail of mRNAs, followed by reverse transcription utilizing template-switching oligonucleotides (TSO) to capture the 5' end [16] [17]. The SMART-seq (Switching Mechanism at 5' End of RNA Template) technology and its subsequent iterations (SMART-seq2, SMART-seq3, SMART-seq HT) represent the most widely adopted implementations of this approach [17]. These methods generate sequencing libraries that cover the entire transcript length, enabling comprehensive characterization of transcriptional landscapes.

Key advantages of full-length protocols include their ability to detect alternative splicing events, single nucleotide variants, allele-specific expression, and comprehensive isoform diversity [16] [15]. Methods like RamDA-seq have further expanded these capabilities to include total RNA sequencing, capturing both polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated RNAs, including nascent transcripts, histone mRNAs, long noncoding RNAs, and enhancer RNAs [16]. This comprehensive coverage comes with specific technical requirements, including higher sequencing depth per cell to adequately cover full-length transcripts, which typically results in higher costs per cell and lower overall throughput compared to end-counting methods [17] [15].

3'/5' End Counting Protocols

End counting methods represent a fundamentally different approach that focuses sequencing efforts on either the 3' or 5' ends of transcripts, utilizing unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) for precise transcript quantification [1] [18]. These protocols typically employ droplet-based microfluidics systems (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium, Drop-seq, inDrop) or combinatorial indexing strategies (e.g., FIPRESCI) to process thousands to hundreds of thousands of cells in a single experiment [1] [19]. The core innovation lies in the incorporation of cell barcodes and UMIs during reverse transcription, enabling massive multiplexing and accurate digital counting of transcript molecules.

The 5' end methods (e.g., STRT-seq, FB5P-seq, FIPRESCI) capture the beginning of transcripts, providing advantages for identifying transcription start sites, promoter usage, and enhancer activity [18] [19]. Additionally, 5' end protocols are particularly suited for immune repertoire sequencing as they naturally cover the variable regions of T-cell receptors (TCR) and B-cell receptors (BCR) [18] [19]. In contrast, 3' end methods (e.g., Drop-seq, Chromium, Seq-Well) focus on the transcript termini, providing robust gene expression quantification with high cell throughput [15]. Both approaches sacrifice complete transcript information for dramatically increased scalability and reduced per-cell costs, making them ideal for large-scale atlas projects and studies focusing on cellular heterogeneity rather than isoform diversity.

Visual Comparison of Core Methodologies

The following workflow diagrams illustrate the fundamental technical differences between full-length and end-counting approaches, highlighting key branching points in experimental design.

Comparative Analysis: Technical Specifications and Performance Metrics

Direct comparison of full-length versus end-counting protocols requires evaluation across multiple technical parameters. The following tables provide a structured analysis of key characteristics, performance metrics, and cost considerations to inform experimental design decisions.

Technical Specifications and Applications

Table 1: Core Technical Characteristics of Major scRNA-seq Protocol Types

| Parameter | Full-Length Protocols | 3' End Counting | 5' End Counting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcript Coverage | Complete mRNA molecule (5' to 3') | 3' terminal region only | 5' start region only |

| Priming Strategy | Oligo-dT + template switching | Oligo-dT with barcodes | Oligo-dT or random with barcodes |

| UMI Incorporation | Limited implementations (e.g., SMART-seq3) | Standard feature | Standard feature |

| Throughput (Cells) | Low to medium (96-1,000 cells) | High (10,000-100,000 cells) | High (10,000-100,000 cells) |

| Sensitivity (Genes/Cell) | High (7,000-10,000 genes) | Medium (1,000-5,000 genes) | Medium (1,000-5,000 genes) |

| Key Applications | Alternative splicing, mutation detection, isoform discovery | Cell typing, trajectory inference, differential expression | Immune repertoire, transcription start sites, enhancer activity |

| Representative Methods | SMART-seq2, SMART-seq3, RamDA-seq, MATQ-seq | 10x Genomics Chromium, Drop-seq, Seq-Well | STRT-seq, FB5P-seq, FIPRESCI |

Performance Benchmarking and Cost Analysis

Table 2: Performance and Practical Considerations for Selected Protocols

| Protocol | Type | Genes/Cell | Cells/Run | Cost/Cell (€) | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMART-seq3 | Full-length | ~10,000 | 96-384 | ~12 | High sensitivity, UMIs, isoform information | Lower throughput, higher hands-on time |

| G&T-seq | Full-length | ~9,500 | 96 | ~12 | Parallel genome & transcriptome, high sensitivity | Complex workflow, low throughput |

| Takara SMART-seq HT | Full-length | ~8,000 | 96-384 | ~73 | Automation friendly, consistent performance | Highest cost, medium sensitivity |

| 10x Chromium (3') | 3' end | 1,000-5,000 | 10,000 | ~0.70 | High throughput, standardized, easy use | Limited transcript information |

| FB5P-seq | 5' end | 2,000-5,000 | 96-384 | ~2.70 | Immune repertoire, FACS integration | Medium throughput, specialized application |

| FIPRESCI | 5' end | 1,000-4,000 | 100,000+ | <0.50 | Massive scalability, low multiplet rate | Complex barcoding, newer method |

Detailed Methodologies: Protocol Implementation

Full-Length Protocol: SMART-seq3 Workflow

SMART-seq3 represents the cutting edge of full-length scRNA-seq protocols, incorporating UMIs while maintaining full-length transcript coverage [17]. The detailed experimental procedure encompasses the following critical stages:

Single-Cell Isolation and Lysis: Individual cells are sorted into 96- or 384-well plates containing lysis buffer using FACS or microfluidic platforms. The lysis buffer typically includes detergents (e.g., Triton X-100), RNase inhibitors, dNTPs, and oligo-dT primers. Each well receives a single cell, and plates are immediately frozen on dry ice and stored at -80°C until processing.

Reverse Transcription and Template Switching: Reverse transcription is performed using Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (M-MLV) reverse transcriptase with template-switching activity. The reaction includes:

- Template Switching Oligo (TSO) with unique molecular identifiers (UMIs)

- Oligo-dT primer containing well-specific barcodes

- Betaine and MgClâ‚‚ to enhance reaction efficiency

- Incubation: 90 min at 42°C, followed by enzyme inactivation at 70°C

cDNA Amplification and Purification: Full-length cDNA is amplified via PCR (18-22 cycles) using ISPCR primers. The amplification reaction utilizes a high-fidelity DNA polymerase with proofreading activity. Amplified cDNA is purified using solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) beads with a 0.6-0.8× bead-to-sample ratio to remove primers, enzymes, and short fragments.

Library Preparation and Sequencing: Tagmentation-based library preparation (e.g., Nextera XT) fragments the cDNA and adds sequencing adapters. Library quality is assessed using capillary electrophoresis (e.g., Bioanalyzer), and quantification is performed via fluorometry. Sequencing is typically performed on Illumina platforms with 2×150 bp paired-end reads to ensure complete transcript coverage.

End-Counting Protocol: FIPRESCI Workflow for 5' End Sequencing

FIPRESCI (FIve PRime End Single-cell Combinatorial Indexing) combines droplet microfluidics with combinatorial indexing to achieve massive throughput for 5' end sequencing [19]. The protocol involves these key steps:

Cell Permeabilization and Reverse Transcription: Cells or nuclei are fixed and permeabilized to allow reagent access while maintaining structural integrity. Reverse transcription is performed using oligo-dT primers or random hexamers in suspension. For nuclei preparations, this step captures nuclear transcripts including nascent RNA.

Combinatorial Pre-Indexing with Tn5 Transposase: Permeabilized cells/nuclei are distributed across a 96-well plate, with each well containing Tn5 transposase loaded with unique barcoded oligonucleotides. The Tn5 simultaneously fragments and tags cDNA molecules with well-specific barcodes (Round 1 barcoding). Critically, the reaction occurs without SDS to maintain Tn5 binding to cDNA.

Droplet-Based Barcoding with High Overloading: Pre-indexed cells are pooled and loaded into a microfluidic droplet system (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium) at high concentrations (10-20× standard loading). Within droplets, cDNA undergoes template switching with TSO containing:

- Droplet-specific barcodes (Round 2 barcoding)

- Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs)

- PCR handle sequences

Library Amplification and Target Enrichment: Droplets are broken, and barcoded cDNA is pooled and amplified via PCR (12-14 cycles). For immune repertoire analysis, an additional targeted PCR enrichment is performed using constant region primers for TCR or BCR sequences. Final libraries are quantified and sequenced with a custom read structure to decode combinatorial indices.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials and Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Their Applications in scRNA-seq Protocols

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Protocol Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reverse Transcriptases | M-MLV RT, SmartScribe | cDNA synthesis with template switching | Universal, critical for full-length |

| Template Switching Oligos | TSO with LNA modifications, TSO with UMIs | 5' cDNA capture, enhances efficiency | Full-length protocols, some 5' end |

| Barcoding Systems | 10x Barcoded Gel Beads, Custom Tn5 | Cell and molecular indexing | End-counting methods, combinatorial indexing |

| Amplification Kits | NEBNext Ultra II FS, KAPA HiFi | cDNA amplification, library preparation | Universal with protocol-specific optimization |

| Library Prep Kits | Nextera XT, Illumina TruSeq | Sequencing library generation | Method-dependent selection |

| Cell Viability Assays | Propidium iodide, DAPI, Calcein AM | Assessment of cell integrity pre-processing | Universal quality control |

| mRNA Capture Beads | Oligo-dT Magnetic Beads | mRNA purification from lysate | G&T-seq, other purification-needed protocols |

Application Contexts: Matching Protocols to Biological Questions

Guidance for Protocol Selection

The optimal scRNA-seq protocol depends fundamentally on the specific research question and experimental constraints. The following decision framework provides guidance for selecting the most appropriate methodology:

Choose Full-Length Protocols When: Investigating alternative splicing patterns in cancer subtypes [15], characterizing isoform diversity in neuronal development [16], identifying allele-specific expression in heterogeneous tissues [15], or studying non-polyadenylated RNAs (e.g., enhancer RNAs, histone mRNAs) using specialized methods like RamDA-seq [16].

Choose 3' End Counting When: Constructing cell atlases of complex tissues (e.g., human cell atlas projects) [1], analyzing cellular heterogeneity in tumor microenvironments [14], performing large-scale drug screening with single-cell resolution [14], or tracing developmental trajectories with high cell numbers [15].

Choose 5' End Counting When: Studying adaptive immune responses with paired TCR/BCR sequencing [18] [19], investigating transcription start site usage and promoter activity [19], analyzing cis-regulatory elements and enhancer activity [19], or requiring high-throughput analysis with immune receptor profiling.

Emerging Applications and Future Directions

Recent methodological advances continue to expand scRNA-seq applications. The integration of spatial transcriptomics with single-cell approaches addresses the limitation of lost spatial context in conventional scRNA-seq [14]. Multi-omics technologies like G&T-seq enable parallel analysis of genome and transcriptome from the same cell, providing opportunities to connect genotypes with transcriptional phenotypes [17]. Combinatorial indexing strategies like FIPRESCI push throughput boundaries, enabling massive-scale experiments approaching millions of cells [19]. Additionally, long-read single-cell sequencing is emerging as a powerful approach for direct isoform characterization without inference, as demonstrated in bulk Iso-Seq studies of immune cells [20].

The strategic selection between full-length and end-counting scRNA-seq protocols represents a fundamental decision point in experimental design, with significant implications for data quality, analytical capabilities, and resource allocation. Full-length methods provide comprehensive transcript information essential for isoform-level analyses but at higher per-cell costs and lower throughput. Conversely, end-counting approaches offer unprecedented scalability for cellular heterogeneity studies while sacrificing detailed transcript structure information. As the field continues to evolve, emerging technologies like combinatorial indexing and long-read single-cell sequencing promise to further expand these capabilities. By understanding the technical foundations, performance characteristics, and application fit of these distinct approaches, researchers can make informed decisions that align methodological capabilities with biological questions, ultimately maximizing the scientific return on investment in single-cell transcriptomics.

The Role of Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) and Spike-Ins in Quantitative Accuracy

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biomedical research by enabling the characterization of transcriptomes at the resolution of individual cells, revealing cellular heterogeneity that is obscured in bulk RNA sequencing approaches [21] [2]. Despite its transformative potential, a significant challenge in scRNA-seq lies in achieving precise quantitative accuracy in transcript measurement due to multiple technical variables including amplification biases, molecular capture efficiency, and sequencing artifacts [22] [23]. The minute starting amounts of RNA in individual cells (typically 10âµâ€“10ⶠmRNA molecules) necessitate substantial amplification, which introduces quantitative distortions that can compromise data integrity [24] [2].

To address these challenges, two powerful methodological approaches have been developed: Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) and spike-in controls. UMIs are short, random nucleotide sequences (typically 4-12 bases) that are incorporated during reverse transcription to uniquely tag individual mRNA molecules, enabling bioinformatic correction for amplification biases [24] [1]. Spike-in controls are synthetic RNA molecules added in known quantities to samples, serving as internal standards for quality control and normalization [23] [25]. When implemented together within a scRNA-seq workflow, these tools provide a robust framework for achieving unprecedented quantitative accuracy in single-cell transcriptomics, which is particularly crucial for applications in drug development and precision medicine where reliable quantification of subtle transcriptional changes is essential [26].

Fundamental Principles of UMIs

Technical Implementation and Mechanism of Action

Unique Molecular Identifiers function as molecular barcodes that are attached to each cDNA molecule during the initial reverse transcription step, prior to any amplification [24]. The core principle is that all PCR amplicons derived from a single original mRNA molecule will share an identical UMI sequence. Following sequencing, bioinformatics pipelines can collapse reads with identical UMIs and mapping coordinates into a single count, thereby eliminating artifactual inflation from PCR duplicates [24] [25]. This process, known as deduplication, ensures that the final count for each transcript reflects the true number of original molecules rather than amplification artifacts.

The effectiveness of UMI-based counting depends on several critical parameters. The length and complexity of the UMI sequence directly influences the maximum number of molecules that can be uniquely tagged. For instance, a 10-nucleotide UMI can theoretically generate 4¹Ⱐ(1,048,576) unique combinations, which is generally sufficient for tagging the approximately 100,000-1,000,000 mRNA molecules typically found in a mammalian cell [24]. However, UMI sequences are susceptible to errors during PCR amplification and sequencing, necessitating computational error correction strategies that typically involve collapsing UMIs within a certain Hamming distance (e.g., 1-2 nucleotides) of each other [22].

Practical Considerations for UMI Design and Implementation

The quantitative performance of UMIs is significantly influenced by experimental design choices. A comprehensive study evaluating UMI-based scRNA-seq protocols revealed that UMI lengths of at least 8 nucleotides are necessary for accurate RNA counting across a wide range of expression levels, with shorter UMIs exhibiting elevated collision rates that lead to undercounting [22]. Furthermore, specific protocol steps can dramatically impact counting accuracy. For example, in tSCRB-seq protocol implementations that omit cleanup steps after reverse transcription, residual primers can cause substantial UMI overcounting, linearly correlating with sequencing depth rather than true biological expression [22].

Table 1: Impact of UMI Length on Quantitative Accuracy

| UMI Length | Theoretical Diversity | Molecular Exponent* | Counting Accuracy | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 nt | 256 | ~0.6 | Low | Severe undercounting due to limited diversity |

| 6 nt | 4,096 | <0.8 | Moderate | Elevated collision rates |

| 8 nt | 65,536 | ~0.8 | Good | Accurate for most expression levels |

| 10 nt | 1,048,576 | ~0.8-1.0 | Excellent | Optimal for full expression range |

| 12 nt | 16,777,216 | ~1.0 | Excellent | Minimal collisions, higher sequencing cost |

The molecular exponent describes the relationship between input molecules and UMI counts (ideal value = 1) [23]

Spike-In Controls: Types and Applications

Categories of Spike-In Controls

Spike-in controls can be broadly categorized into two main types: synthetic RNA spike-ins and cellular spike-ins. The most widely used synthetic spike-ins are the External RNA Controls Consortium (ERCC) standards, which comprise 92 synthetic RNA transcripts with varying lengths and GC content, mixed at known concentrations that span a wide dynamic range [23] [25]. These are typically added to cell lysates at the beginning of library preparation. More recently, "molecular spikes" have been developed that incorporate built-in UMIs, creating an experimental ground truth that enables direct assessment of a protocol's RNA counting performance [22] [27].

Cellular spike-ins involve adding well-characterized cells (e.g., mouse 32D cells into human samples) prior to processing, creating internal controls that enable detection and correction for sample-specific contamination. This approach has proven particularly valuable for identifying cross-contamination from cell-free RNA, which can constitute up to 20% of reads in primary tissue samples [26].

Implementation Framework for Spike-In Controls

The effective use of spike-in controls requires careful experimental planning. For synthetic RNA spike-ins like ERCC standards, they should be added at the earliest possible stage of library preparation—ideally during cell lysis—to subject them to the entire experimental workflow alongside endogenous transcripts [23]. The spike-in molecules should cover the entire expected dynamic range of endogenous expression, with concentrations calibrated to match the expected RNA content of the cells being studied [23].

For cellular spike-ins, the reference cells should be fixed to prevent any transcriptional responses during processing, and typically comprise 5-10% of the total cell population [26]. Cross-species spike-ins (e.g., mouse cells in human samples) are particularly advantageous as they allow unambiguous separation of spike-in and sample-derived transcripts during bioinformatic analysis through alignment to separate reference genomes [26].

Diagram 1: Spike-in implementation workflow illustrating parallel paths for synthetic and cellular spike-ins

Integrated Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Molecular Spikes for scRNA-seq Validation

Molecular spikes with built-in UMIs provide a robust method for validating the quantitative performance of scRNA-seq protocols [22] [27]. The following protocol outlines their implementation:

Reagents Required:

- Molecular spike RNA pools (5′ or 3′ molecular spikes with 18-nt spUMIs)

- scRNA-seq library preparation kit (e.g., Smart-seq3, 10x Genomics)

- Standard cell culture reagents for the chosen cell line

Procedure:

- Spike-in Calibration: Dilute molecular spikes to appropriate concentrations spanning the expected expression range of endogenous transcripts (typically 1-1,000 molecules per cell).

- Sample Preparation: Add calibrated molecular spikes to single-cell suspensions of HEK293FT cells or other relevant cell lines.

- Library Preparation: Process samples according to standard scRNA-seq protocols (e.g., Smart-seq3 for full-length coverage or 10x Genomics for 3′-tagging).

- Sequencing: Sequence libraries following platform-specific recommendations.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Extract spUMI sequences from aligned reads

- Apply error correction using a Hamming distance of 2 nucleotides

- Exclude over-represented spUMIs across cells to remove potential biases

- Compare observed spUMI counts to expected values to calculate counting accuracy

Validation Metrics: The protocol should yield a strong correlation (r² > 0.99) between observed error-corrected counts and the known number of spiked molecules across the tested concentration range [22].

Protocol 2: Cellular Spike-ins for Contamination Detection

This protocol utilizes cross-species cellular spike-ins to identify and correct for RNA contamination in scRNA-seq experiments [26]:

Reagents Required:

- Mouse 32D cells (for human samples) or other cross-species cell lines

- Methanol for fixation

- Single-cell suspension of primary tissue (e.g., human pancreatic islets)

- 10X Chromium platform or similar droplet-based system

Procedure:

- Spike-in Cell Preparation: Fix approximately 5×10ⵠmouse 32D cells in methanol and store at -80°C until use.

- Sample Preparation: Dissociate primary human tissue (e.g., pancreatic islets) to single-cell suspension and determine viable cell count.

- Spike-in Addition: Thaw fixed mouse cells and add to human cell suspension at a ratio of 1:20 (mouse:human cells).

- Single-Cell Processing: Immediately load the mixed cell suspension onto the 10X Chromium controller following manufacturer's instructions.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Proceed with standard 10X Genomics library preparation and sequencing.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Align sequences to a combined human-mouse reference genome

- Separate cells by species origin using the ratio of human:mouse reads

- Quantify cross-species contamination by measuring human reads in mouse cells

- Apply computational decontamination algorithms to correct endogenous cell expression profiles

Quality Assessment: Effective implementation typically reduces contamination artifacts from >15% to <2% of reads, significantly improving detection of true biological signals, particularly for low-abundance transcripts [26].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of scRNA-seq Protocols with Spike-in Controls

| scRNA-seq Protocol | Sensitivity (50% Detection Probability) | Accuracy (Pearson Correlation with Spike-ins) | UMI Efficiency | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMART-seq2 | ~10 molecules | 0.85-0.95 | N/A (Full-length) | Alternative splicing, mutation detection |

| 10X Genomics (3′) | ~100 molecules | 0.80-0.90 | ~80% | High-throughput cell atlas construction |

| CEL-seq2 | ~10 molecules | 0.75-0.85 | ~75% | Plate-based targeted studies |

| MARS-seq | ~50 molecules | 0.70-0.80 | ~70% | High-throughput screening |

| Drop-seq | ~100 molecules | 0.75-0.85 | ~75% | Cost-effective large-scale studies |

| inDrop | ~10 molecules | 0.75-0.85 | ~75% | High-sensitivity applications |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for UMI and Spike-in Applications

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic RNA Spike-ins | ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix (Thermo Fisher) | Protocol normalization and sensitivity assessment | Covers 6 logs of dynamic range; 92 transcripts |

| Molecular Spikes | 5′ and 3′ molecular spikes with spUMIs [22] | Direct assessment of RNA counting accuracy | Built-in 18-nt UMIs; enables ground-truth validation |

| Cellular Spike-ins | Mouse 32D cells, Human Jurkat cells [26] | Contamination detection and correction | Cross-species application recommended |

| UMI Library Prep Kits | 10X Genomics Chromium, SMART-seq3, CEL-seq2 | Incorporation of UMIs during cDNA synthesis | Varying UMI lengths (6-12 nt) impact counting accuracy |

| Bioinformatics Tools | UMI-tools, zUMIs, UMIcountR [22] [23] | Demultiplexing, error correction, and deduplication | Hamming distance parameters must be optimized |

| Reference Transcriptomes | Combined species references (e.g., human-mouse) | Bioinformatic separation of spike-in and sample reads | Essential for cellular spike-in analysis |

Data Analysis Framework

Bioinformatics Processing Pipeline

The analysis of UMI and spike-in scRNA-seq data requires specialized bioinformatic processing to extract quantitative insights. A standardized workflow encompasses multiple stages:

Primary Processing:

- Demultiplexing: Separate sequencing data by sample barcodes

- UMI Extraction: Identify and record UMI sequences from read headers or sequences

- Alignment: Map reads to an appropriate reference genome (possibly combined species for cellular spike-ins)

- Deduplication: Collapse reads with identical UMIs and mapping coordinates

Spike-in Specific Processing:

- Spike-in Identification: Separate endogenous and spike-in reads using predefined identifiers

- Contamination Assessment: For cellular spike-ins, quantify cross-species alignment rates

- Normalization: Use spike-in derived factors to adjust for technical variability between samples

- Error Correction: Apply UMI error correction using hierarchical clustering or network-based approaches

Diagram 2: Bioinformatic workflow for processing UMI and spike-in scRNA-seq data

Normalization Strategies Using Spike-ins

Spike-in controls enable sophisticated normalization approaches that account for technical variability in capture and amplification efficiency. The most effective methods include:

Spike-in Based Size Factors: Calculate size factors for each cell based on spike-in counts to normalize for technical differences in capture efficiency, applying the formula:

SF_cell = median(spike-in counts_cell / mean spike-in counts across all cells)

Multipath Normalization: Combine spike-in derived factors with endogenous content factors to address both capture efficiency and sequencing depth variations.

Contamination Correction: For cellular spike-ins, use the contamination profile observed in spike-in cells to computationally remove background contamination from endogenous cell expression data [26].

These normalization strategies have been shown to significantly improve quantitative accuracy, particularly when analyzing subtle transcriptional changes in drug response studies or identifying rare cell populations [26].

Applications in Drug Development and Biomedical Research

The implementation of UMI and spike-in controls has enabled particularly impactful applications in pharmaceutical research and development, where quantitative accuracy is paramount for reliable decision-making.

In drug mechanism-of-action studies, researchers have employed spike-in controlled scRNA-seq to elucidate cell-type-specific drug effects in complex tissues. For example, when applying this approach to human and mouse pancreatic islets treated with various drugs including artemether and a FOXO inhibitor, researchers obtained precise quantification of cell-specific drug effects, observing that FOXO inhibition induced dedifferentiation of both alpha and beta cells [26]. This level of quantitative resolution enables more confident identification of cell-type-specific responses and potential off-target effects during preclinical drug evaluation.

In oncology applications, UMI-enhanced scRNA-seq has proven invaluable for characterizing tumor heterogeneity and identifying rare drug-resistant subpopulations that might be missed without rigorous quantitative controls. The ability to accurately count transcripts using UMIs allows researchers to distinguish true biological variation from technical artifacts, enabling more reliable identification of biomarkers and drug targets [2]. Furthermore, cellular spike-in approaches have been instrumental in detecting and correcting for ambient RNA contamination in tumor microenvironments, where high levels of cell death can significantly compromise data quality [26].

The integration of these quantitative controls has also accelerated the development of cell atlases in regenerative medicine, providing reference standards for cellular composition and expression levels that enable robust comparison across studies, laboratories, and experimental conditions [1] [21]. As single-cell technologies continue to evolve toward clinical applications, UMI and spike-in methodologies will play an increasingly critical role in ensuring the reproducibility and reliability of results that inform therapeutic development.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling the examination of gene expression patterns at the ultimate level of resolution: the individual cell. This technology has become the state-of-the-art approach for unravelling the heterogeneity and complexity of RNA transcripts within individual cells, as well as revealing the composition of different cell types and functions within highly organized tissues/organs/organisms [1]. Since its conceptual breakthrough in 2009, scRNA-seq has provided massive information across different fields, leading to exciting new discoveries in understanding cellular composition and interactions [1]. The ability to profile gene expression activity in individual cells represents one of the most authentic approaches to probe cell identity, state, function, and response, allowing researchers to classify, characterize, and distinguish each cell at the transcriptome level [1]. This technical capability has opened two particularly powerful application domains: the discovery and characterization of rare cell populations that are functionally important but often missed in bulk analyses, and the tracing of lineage trajectories that reveal developmental pathways and cellular differentiation processes. These applications are transforming our understanding of cellular heterogeneity, disease mechanisms, and developmental biology, providing unprecedented insights into the complex organization of biological systems from humans to model animals and plants [1].

Discovering Rare Cell Types

Technological Foundation and Principles

The power of scRNA-seq to identify rare cell populations stems from its ability to analyze transcriptomes at single-cell resolution for over millions of cells in a single study [1]. Unlike traditional bulk RNA sequencing, which measures average gene expression across thousands or millions of cells, thereby obscuring rare cellular signatures, scRNA-seq captures the unique transcriptional profile of each individual cell. This capability is particularly valuable for identifying rare but functionally critical cell types that exist in low frequencies within tissues, such as stem cells, progenitor cells, or rare pathological cells [1]. The technological foundation for this application involves several key steps: single-cell isolation and capture, cell lysis, reverse transcription (conversion of RNA into cDNA), cDNA amplification, and library preparation [1]. The dramatic reduction in cost and significant increase in automation and throughput have made large-scale scRNA-seq studies feasible, enabling comprehensive cataloging of cellular diversity [1]. The introduction of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) has further enhanced the quantitative nature of scRNA-seq by effectively eliminating PCR amplification bias, thereby improving the accuracy of rare cell population identification [1].

Experimental Protocol for Rare Cell Discovery

Sample Preparation and Single-Cell Suspension: The initial critical step involves generating high-quality single-cell suspensions from the tissue of interest. For live cell dissociations, this typically includes a combination of enzymatic digestion of extracellular components and mechanical disruption to separate cells while maintaining viability [28]. The dissociation process must be performed rapidly to minimize transcriptomic responses to dissociation stress. Performing digestions on ice can help mediate these transcriptional responses, though this may slow digestion times as most commercially available enzymes are optimized for activity at 37°C [28]. Recently, fixation-based methods have been applied to relieve some of these issues by essentially stopping the transcriptomic response. Methods include methanol maceration optimized for single cell sequencing (ACME) or reversible dithio-bis(succinimidyl propionate) (DSP) fixation immediately following cell dissociation [28]. For tissues that are difficult to dissociate, single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) provides an alternative approach that solves problems related to tissue preservation and cell isolation [1].

Cell Capture and Library Preparation: Current commercially available solutions for cell capture and library generation vary in their mechanisms and capacity. The 10x Genomics platform offers a droplet microfluidics solution with the flexibility to capture as few as 500 or as many as 20,000 cells with their latest GEM-X v4 assay [28]. Illumina provides a vortex-based single cell droplet capture solution that can process a wide range of inputs without microfluidics platform restrictions [28]. Alternative approaches include sorting cells into microwells (BD Rhapsody, Singleron) with larger maximal size capacity than microfluidics approaches, and plate-based combinatorial barcoding solutions (Scale BioScience, Parse BioScience) that can return over 100,000 cells [28]. The choice of platform depends on the specific research requirements, including the number of cells needed, cell size characteristics, and project scale.

Bioinformatic Analysis and Clustering: Following sequencing, bioinformatic analysis is performed to identify rare cell populations. This process involves mapping reads to an adequate reference to generate a count matrix, followed by downstream analyses of expression profiles [28]. Clustering analysis has become an essential tool for interpreting and revealing cell types and functional states within these complex datasets [29]. Advanced clustering methods such as Seurat, PhenoGraph, SC3, and Scanpy are employed to identify groups of cells with similar expression patterns [30] [29]. The recently developed scMSCF (single-cell Multi-Scale Clustering Framework) introduces a multi-dimensional PCA strategy for dimensionality reduction, combined with K-means clustering and a weighted ensemble meta-clustering approach enhanced by a self-attention-driven Transformer model to optimize clustering performance [29]. This method has demonstrated improved ability to identify diverse cell populations, achieving on average 10-15% higher ARI, NMI, and ACC scores compared to existing methods [29].

Key Applications and Impact

The discovery of rare cell types through scRNA-seq has profound implications across multiple research domains. In developmental biology, scRNA-seq has enabled the identification of rare progenitor populations during organogenesis and tissue formation [1]. In cancer research, the technology has revealed rare tumor-initiating cells and resistance-conferring subpopulations within heterogeneous tumors [1]. In neuroscience, scRNA-seq has uncovered specialized neuronal subtypes that were previously unrecognized [1]. The application of scRNA-seq to build comprehensive cell atlases for various organisms and tissues represents one of the most significant contributions of this technology, serving as key resources for better understanding and treating diseases [1]. These atlases provide high-resolution catalogs of cells in living organisms, enabling researchers to reference rare cell populations across different conditions and disease states.

Table 1: scRNA-seq Clustering Methods for Rare Cell Type Identification

| Method | Key Features | Advantages for Rare Cell Discovery | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seurat | Integrates normalization, scaling, PCA; constructs cell similarity graph via k-nearest neighbors | Effective community detection; widely validated | [30] [29] |

| PhenoGraph | Constructs cell relationships using k-nearest neighbors; applies community detection algorithms | Suitable for biologically related cell types with subtle expression differences | [29] |

| SC3 | Utilizes multiple clustering results to enhance clustering decisions | Improved consensus approach for robust clustering | [29] |

| scMSCF | Combines multi-dimensional PCA, K-means, weighted ensemble meta-clustering, and Transformer model | 10-15% higher ARI, NMI, and ACC scores; captures complex dependencies | [29] |

| SHARP | Ensemble strategies based on random projections | Improved clustering speed and accuracy for large, noisy datasets | [29] |

Tracing Lineage Trajectories

Fundamental Concepts and Historical Development

Lineage tracing represents an essential approach for understanding cell fate, tissue formation, and human development [31]. At its core, lineage tracing encompasses any experimental design aimed at establishing hierarchical relationships between cells, enabling researchers to investigate cell morphology, differentiation, clonal expansion, and gene inheritance/expression [31]. The resolution and methodological approach define the limits of an analysis, balancing precision and generalizability. The field has evolved significantly from its origins in the late 1800s, when Charles Whitman reported the direct observation of germ layer differentiation in leeches [31]. The introduction of labeling technologies represented a major advancement, beginning with Eric Vogt's 1929 fate mapping of an amphibian blastula using Nile Blue [31]. The late 20th century witnessed exponential development of gene editing technologies, particularly through the manipulation of reporter genes that circumvented limitations of earlier approaches [31]. The introduction of green fluorescent protein (GFP) as an endogenous reporter in 1994 marked a massive shift for lineage tracing, giving cells the potential to express reporters without the need for an external stimulus [31]. These historical developments laid the foundation for modern lineage tracing approaches that integrate sophisticated imaging with scRNA-seq technologies.

Imaging-Based Lineage Tracing Techniques

Site-Specific Recombinase Systems: Central to imaging-based lineage-tracing research are site-specific recombinase (SSR) systems, with Cre-loxP remaining one of the most fundamental and commonly used [31]. These systems can knock-in/knock-out alleles and influence gene expression with a great degree of cell and temporal specificity. In lineage tracing, Cre-loxP systems are commonly applied in clonal analysis studies, where Cre recombinase excises a STOP codon between two adjacent loxP binding sites, activating a fluorescent reporter gene [31]. The specificity of this activation depends on Cre, whose expression can be driven by cell-type-specific promoters or ubiquitously expressed. A significant limitation of single fluorescent reporters is their difficulty in resolving cell populations at the single-cell level due to the challenge of distinguishing clonal groups within homogenously labelled populations [31]. Sparse labelling approaches can circumvent this by titrating the activating agent in inducible models to limit recombination to a limited number of cells within the population, thus allowing for spatial separation [31].

Dual Recombinase Systems: The Cre-loxP system can be combined with analogous technologies like Dre-rox to create dual recombinase systems [31]. These systems take advantage of the site specificity of recombinases and offer multiple experimental design strategies beneficial to lineage tracing, including expression occurring following recombination of either Cre or Dre, both Cre and Dre, or Cre in the absence of Dre [31]. Dual systems have been successfully applied to determine the origin of regenerative cells in remodelled bone, investigate cellular origins of alveolar epithelial stem cells post-injury, and develop novel genetic techniques for evaluating senescence [31]. For example, a Cre/Dre dual system was used to distinguish otherwise homogenous periosteal tissue into distinct layers and evaluate layer contributions in fracture regeneration [31].

Multicolour Lineage Tracing Approaches: A major advance in imaging-based lineage tracing was the introduction of multicolour reporter cassettes, beginning with "Brainbow," capable of expressing up to four different fluorescent proteins driven by stochastic Cre-loxP-mediated excision and/or inversion [31]. This technology has since been adapted to several experimental models and inspired numerous analogous technologies [31]. The R26R-Confetti reporter represents one of the most popular adaptations due to its widespread applicability to existing Cre models [31]. Lineage-tracing studies now incorporate confetti reporters for clonal analysis at the single-cell level in various tissues, including hematopoietic, epithelial, kidney, and skeletal cells [31]. Multicolour models are also being applied in live-imaging studies; for example, confetti reporters have recently been used in intravital imaging to trace macrophage origin and proliferation in mammary glands in real time [31].

Table 2: Lineage Tracing Techniques and Their Applications

| Technique | Mechanism | Resolution | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cre-loxP System | Site-specific recombination activates reporter expression | Population to single-cell (with sparse labelling) | Broad applicability; clonal analysis; inducible systems |

| Dual Recombinase Systems | Combined recombinase systems (e.g., Cre-loxP/Dre-rox) | Enhanced cellular resolution | Distinguishing homogeneous tissue layers; simultaneous tracking of multiple populations |

| Multicolour Reporters (Brainbow, Confetti) | Stochastic recombination generates multiple fluorescent hues | Single-cell | Clonal analysis in hematopoetic, epithelial, kidney, skeletal cells; intravital imaging |

| MADM (Mosaic Analysis with Double Markers) | Sparse labelling with two markers | Single-cell | Developmental lineage tracing; sparse tissue analysis |

| Nucleoside Analogues (BrdU, EdU) | Incorporation into cellular DNA during proliferation | Population level | Identifying proliferating cell populations; label dilution indicates proliferation history |

Integration with scRNA-seq for Lineage Tracing

The integration of lineage tracing with scRNA-seq represents a powerful approach that combines the strengths of both techniques. Modern flagship studies are rigorous and multimodal, validating hypotheses by a multitude of distinct methods [31]. It has become increasingly common for such studies to incorporate advanced microscopy, state-of-the-art sequencing technology, and multiple biological models [31]. The resulting datasets continue to increase in size and complexity, necessitating sophisticated and integrative approaches to experimental design and analysis [31]. scRNA-seq contributes to lineage tracing by providing transcriptomic profiles that reveal cellular states and transitions along differentiation trajectories. Computational methods for trajectory inference, such as pseudotime analysis, can reconstruct the sequence of gene expression changes as cells progress along developmental pathways [28]. While these analysis pipelines are rapidly maturing, gold standards for data integration methods and trajectory inference are still lacking, representing an active area of methodological development [28]. The combination of experimental lineage tracing with computational trajectory inference from scRNA-seq data enables robust reconstruction of developmental hierarchies and validation of lineage relationships.

Integrated Experimental Workflows

Comprehensive scRNA-seq Experimental Pipeline