Allele-Specific Expression (ASE) from RNA-seq: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of allele-specific expression (ASE) analysis using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), a powerful approach for identifying cis-regulatory variation with significant implications for genetics, disease research, and...

Allele-Specific Expression (ASE) from RNA-seq: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of allele-specific expression (ASE) analysis using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), a powerful approach for identifying cis-regulatory variation with significant implications for genetics, disease research, and drug discovery. We cover foundational concepts of ASE and its biological mechanisms, including genomic imprinting, regulatory genetic variation, and X-chromosome inactivation. The guide details state-of-the-art methodological pipelines for ASE quantification, visualization, and statistical testing, alongside cutting-edge applications in stress response research and pharmaceutical development. We address key challenges in RNA-seq variant calling, including technical artifacts, low-coverage genes, and distinguishing true mutations from RNA-editing events, while offering practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies. Finally, we evaluate and compare available ASE analysis tools, discuss validation approaches, and explore future directions with emerging technologies like single-cell RNA-seq and long-read sequencing, providing researchers and drug development professionals with an essential resource for implementing and advancing ASE studies.

Understanding Allele-Specific Expression: Core Concepts and Biological Significance

Defining Allele-Specific Expression and Its Regulatory Mechanisms

Allele-specific expression (ASE) is a transcriptional phenomenon in diploid organisms where the two alleles of a gene—one inherited from each parent—are expressed at unequal levels [1] [2]. In standard biallelic expression, both alleles are transcribed equally, but ASE occurs when one allele is preferentially or exclusively expressed over the other due to various regulatory mechanisms [3]. This imbalance can range from subtle quantitative differences to complete monoallelic expression, where only one allele is actively transcribed [2].

ASE serves as a powerful tool for investigating cis-regulatory variation, as it directly measures the functional outcome of genetic and epigenetic differences between parental alleles within the same cellular environment [4]. The study of ASE has revealed that allelic imbalance affects a substantial proportion of the genome, with estimates suggesting that 10% to over 50% of genes exhibit some form of ASE depending on tissue type and environmental context [1] [2].

Classification and Mechanisms of ASE

Major Categories of ASE

ASE mechanisms can be categorized based on the underlying factors driving the expression imbalance. The two primary classes are sequence-dependent ASE and parent-of-origin-dependent ASE, with additional specialized forms contributing to the regulatory landscape [1].

Sequence-dependent ASE occurs when genetic variations between alleles directly influence their expression levels. These cis-acting regulatory variants may include single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in promoter regions that alter transcription factor binding, variants in enhancer elements that affect long-range regulatory interactions, or sequence changes that influence mRNA stability and processing [1]. The expression imbalance in this case is determined solely by the nucleotide identity of each allele, regardless of which parent contributed it.

Parent-of-origin-dependent ASE manifests when the expression level of an allele depends on whether it was maternally or paternally inherited, independent of its DNA sequence [1]. This category includes genomic imprinting, an epigenetic phenomenon characterized by parent-specific epigenetic marks such as DNA methylation and histone modifications that lead to silencing of one parental allele [1] [2].

Additional ASE Mechanisms

Beyond these primary categories, several specialized mechanisms contribute to allelic expression patterns:

- Random monoallelic expression (RMAE): An epigenetic mechanism where the choice of which allele is expressed appears stochastic and varies between individual cells, yet can become stable in cellular lineages [2] [3].

- X-chromosome inactivation: A form of dosage compensation in females where one X chromosome is largely silenced through epigenetic mechanisms to equalize expression with males who have only one X chromosome [3].

- Allele-specific expression effects mediated by cis-eQTLs: Heterozygous expression quantitative trait loci (cis-eQTLs) can cause ASE when regulatory variants affect the expression of nearby genes in an allele-specific manner [5] [3].

Table 1: Classification of Allele-Specific Expression Mechanisms

| ASE Category | Primary Driver | Key Features | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence-dependent | Genetic variation | Based on nucleotide identity; consistent across tissues | Promoter SNPs, enhancer variants |

| Parent-of-origin | Epigenetic marks | Depends on parental origin; tissue-specific patterns | Genomic imprinting |

| Random monoallelic | Epigenetic + stochastic | Varies between cells; stable in lineages | Olfactory receptor genes, immune genes |

| X-inactivation | Epigenetic | X-chromosome specific; dosage compensation | X-linked genes in females |

Biological Significance and Research Applications

ASE analysis provides unique insights into gene regulation with significant implications for understanding phenotypic diversity, disease mechanisms, and evolutionary processes. The detection of ASE helps bridge the gap between genotype and phenotype by revealing how genetic and epigenetic variation functionally impacts gene expression [1] [4].

In complex genetic diseases like dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), ASE analysis has identified regulatory mechanisms in known disease genes and revealed novel candidate genes that were missed by conventional genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and differential expression analyses [4]. Similarly, in cancer biology, ASE patterns can reveal allelic dysregulation that may underlie or reflect disease states [6] [3].

The tissue-specific and context-dependent nature of ASE underscores the importance of environmental and developmental factors in gene regulation. Studies have shown that ASE patterns can vary significantly between tissues, change during differentiation, and respond to environmental stimuli such as dietary changes [1] [5]. This dynamic regulation highlights the complexity of the genotype-to-phenotype map and emphasizes the need for context-specific analyses.

Methodological Approaches for ASE Analysis

RNA Sequencing-Based Detection

Modern ASE analysis predominantly utilizes RNA sequencing technologies, which enable genome-wide quantification of allelic expression imbalances [3]. The fundamental requirement for ASE detection is the ability to distinguish between maternal and paternal transcripts, typically achieved by leveraging heterozygous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within transcribed regions [1] [3].

The basic analytical approach involves:

- Alignment of RNA-seq reads to a reference genome or transcriptome that incorporates known genetic variants

- Identification of heterozygous SNPs where both alleles are expressed

- Quantification of allelic ratios by counting reads containing each allele

- Statistical testing to identify significant deviations from the expected 1:1 ratio

Advanced methods have been developed to address technical challenges such as mapping bias, where reads containing non-reference alleles may align less efficiently [6]. Tools like EMASE implement hierarchical alignment strategies that resolve ambiguities by considering the nested structure of genes, isoforms, and alleles, significantly improving accuracy compared to methods that discard multi-mapping reads [6].

Single-Cell ASE Analysis

Recent technological advances enable ASE analysis at single-cell resolution (scASE), revealing cell-to-cell heterogeneity in allelic expression that is masked in bulk analyses [5]. Specialized computational methods such as DAESC have been developed to address the statistical challenges of single-cell ASE data, including low read counts per cell and the need to account for non-independence of cells from the same individual [5].

scASE analysis has uncovered dynamic changes in allelic regulation during cellular differentiation and in disease states, providing unprecedented insights into the cell-type-specificity of regulatory variants [5].

Experimental Designs for ASE Studies

Reciprocal cross designs in model organisms like mice are particularly powerful for distinguishing parent-of-origin effects from sequence-dependent effects [1]. By comparing F1 offspring from reciprocal crosses (where the maternal and paternal strains are swapped), researchers can determine whether expression imbalances are consistent (indicating sequence-dependence) or switch according to parental origin (indicating imprinting or other parent-of-origin effects) [1].

Table 2: Key Analytical Tools for ASE Detection

| Tool Name | Application Scope | Key Features | Input Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| EMASE | Bulk RNA-seq | Hierarchical read allocation; resolves multi-mapping reads | RNA-seq + genetic variants |

| DAESC | Single-cell RNA-seq | Beta-binomial model; handles haplotype switching | scRNA-seq + multiple individuals |

| ASEP | Population RNA-seq | Gene-based ASE detection across populations | RNA-seq + genotype data |

| AlleleSpecificExpression | Bulk RNA-seq | End-to-end pipeline; individual and group analyses | RNA-seq + optional genotype data |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Bulk RNA-seq ASE Analysis Protocol

Sample Preparation and Sequencing

- Extract high-quality RNA from tissues or cells of interest

- Prepare strand-specific RNA-seq libraries following standard protocols

- Sequence to sufficient depth (typically 30-50 million reads per sample) to detect allelic imbalances with statistical power

Data Preprocessing

- Perform quality control using tools like FastQC

- Trim adapter sequences and low-quality bases with Trimmomatic or similar tools

- Align reads to a diploid transcriptome reference that incorporates known variants using splice-aware aligners like STAR or HISAT2

ASE Detection and Quantification

- Identify heterozygous SNPs using genotype data or from RNA-seq alone

- Count allele-specific reads at heterozygous positions

- Apply statistical models (typically binomial or beta-binomial) to identify genes with significant allelic imbalance

- Correct for multiple testing using FDR or similar methods

Validation and Interpretation

- Validate key findings using orthogonal methods such as pyrosequencing or droplet digital PCR

- Integrate with epigenetic data (DNA methylation, histone modifications) to identify potential mechanisms

- Correlate ASE patterns with phenotypic data when available

Single-Cell ASE Analysis Protocol

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

- Prepare single-cell suspensions from target tissues

- Use droplet-based or plate-based scRNA-seq platforms (10X Genomics, Smart-seq2)

- Include molecular barcodes to maintain cell identity

Data Processing and ASE Calling

- Process raw sequencing data with cellranger or similar pipelines to generate count matrices

- Perform cell quality control, filtering out low-quality cells and doublets

- Assign cells to cell types using clustering and marker gene identification

- For each cell type, identify heterozygous SNPs and quantify allelic counts

- Use specialized scASE tools (DAESC, scDALI) that account for sparse data and sample structure

Downstream Analysis

- Test for differential ASE between conditions, cell types, or along pseudotemporal trajectories

- Identify genes with cell-type-specific ASE patterns

- Integrate with scATAC-seq or other single-cell epigenomic data when available

Visualization and Data Interpretation

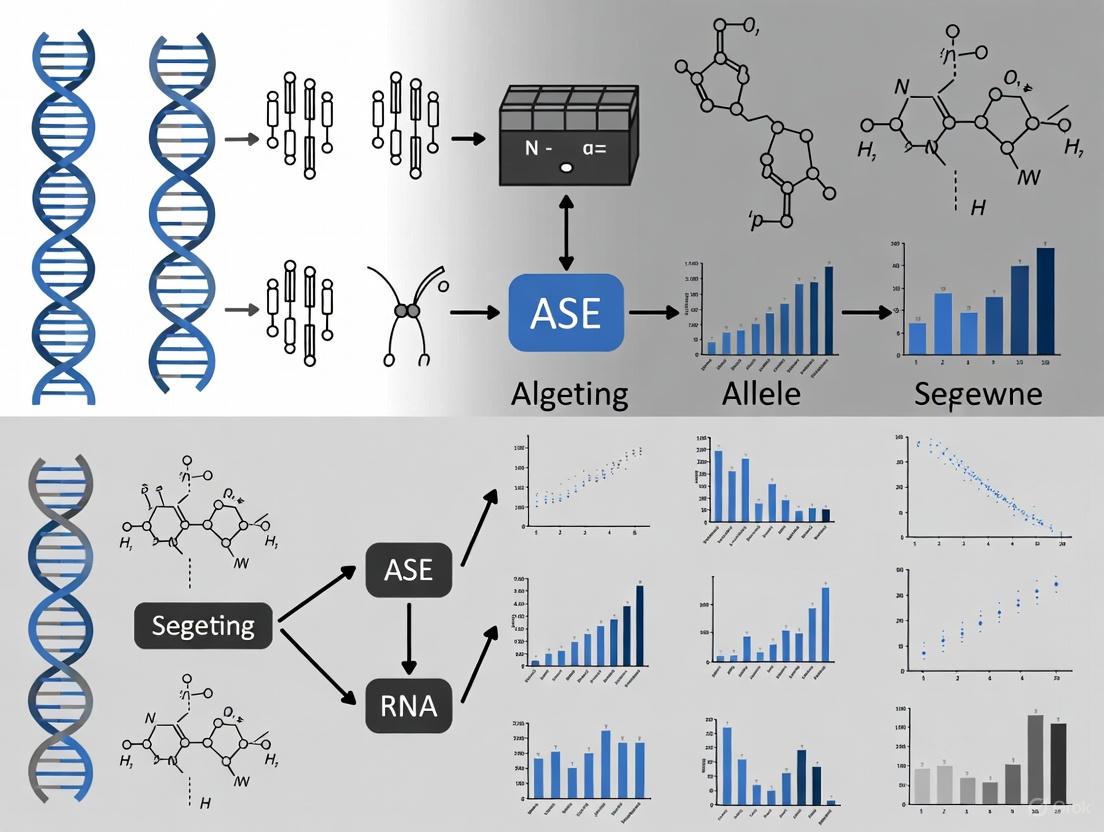

Effective visualization is crucial for interpreting ASE data. The following diagram illustrates the core analytical workflow for ASE detection from RNA sequencing data:

Diagram 1: ASE Analysis Workflow

The classification of ASE mechanisms relies on integrated analysis of genetic and epigenetic data. The following diagram illustrates the decision process for distinguishing between primary ASE types:

Diagram 2: ASE Mechanism Classification

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ASE Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Application Context | Key Features/Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Models | F1 hybrid mice (e.g., LG/J x SM/J) [1] | Reciprocal cross designs | Genetically diverse inbred strains for distinguishing ASE mechanisms |

| Sequencing Technologies | Illumina RNA-seq, 10X Genomics scRNA-seq [5] | Transcriptome profiling | High-throughput sequencing of expressed transcripts |

| Alignment References | Diploid transcriptome references [6] | Read mapping | Incorporates known variants to reduce reference allele bias |

| Computational Tools | EMASE [6], DAESC [5], AlleleSpecificExpression pipeline [4] | ASE detection and analysis | Specialized algorithms for bulk and single-cell ASE quantification |

| Variant Databases | dbSNP, 1000 Genomes Project [3] | Heterozygous SNP identification | Catalog of known genetic variants for informativity assessment |

| Quality Control Tools | FastQC, Trimmomatic [3] | Data preprocessing | Assessment and improvement of sequence data quality |

| Epigenetic Resources | Roadmap Epigenomics [5], ENCODE | Mechanism interpretation | Reference maps of DNA methylation, histone modifications |

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, ASE analysis faces several methodological challenges. Current limitations include:

Technical Artifacts: Reference allele bias during read alignment can artificially inflate ASE signals if not properly corrected [6]. Multi-mapping reads pose particular challenges, as they comprise the majority of sequencing data (>85% in some cases) and require sophisticated allocation methods [6].

Computational Limitations: Most existing pipelines lack end-to-end automation, requiring researchers to combine multiple tools in complex workflows [7]. Support for single-cell RNA-seq data remains limited, with few methods specifically designed for sparse single-cell data [5] [7].

Biological Complexity: The dynamic nature of ASE across tissues, developmental stages, and environmental contexts creates analytical challenges for distinguishing consistent regulatory effects from transient stochastic variation [1] [5].

Future methodological developments will likely focus on integrated multi-omic approaches that combine ASE data with epigenomic, proteomic, and spatial genomic information [7] [2]. As single-cell technologies mature, increased attention will be directed toward understanding cell-to-cell heterogeneity in allelic expression and its functional consequences [5]. The development of more automated, user-friendly pipelines will make ASE analysis accessible to a broader research community, potentially revealing new insights into gene regulation across diverse biological contexts and disease states [4] [7].

Allele-specific expression (ASE) refers to the unequal expression of the two parental alleles of a gene in diploid organisms. While most genes exhibit balanced expression from both chromosomal copies, ASE occurs when genetic or epigenetic variations cause exclusive or preferential expression of one allele [7]. This phenomenon serves as a powerful tool for understanding gene regulation with significant functional and clinical implications, particularly in drug discovery and development [7].

The detection and quantification of ASE patterns provide crucial insights into cis-regulatory mechanisms that influence gene expression, including genomic imprinting, cis-acting regulatory variants, and X-chromosome inactivation [8]. In agricultural species, ASE genes have been linked to economically important traits, while in humans, ASE analysis helps establish connections between genotype and phenotype [8]. Current analysis pipelines face notable limitations including a lack of end-to-end solutions, restricted options for multi-omics integration, and insufficient support for single-cell sequencing technologies [7].

Genomic Imprinting

Genomic imprinting represents a unique type of ASE where autosomal genes are monoallelically expressed from either the paternal or maternal allele due to epigenetic modifications established during gametogenesis [8]. This parent-of-origin specific expression pattern results from epigenetic marks that silence one allele in a parent-specific manner.

Key Characteristics:

- Stable epigenetic memory: Maintained through cell divisions

- Reversible: Reset during gametogenesis

- Developmental regulation: Often associated with embryonic growth and development

The evidence for genomic imprinting in chickens remains controversial. While some studies reported potential imprinting of IGF2 in chicken embryos, others found biallelic expression of this gene and other mammalian imprinted gene orthologs including INS, ASCL2/CASH4, UBE3A, Dlk1, GATM, and M6P/IGF2R [8]. Recent genome-wide investigations using RNA-Seq have yielded conflicting evidence, with most studies indicating absence of genomic imprinting in chicken embryos and postnatal brains, though one study reported thousands of SNPs with parent-of-origin effects in adult chickens [8].

Cis-Regulatory Variation

Cis-regulatory variation represents a major source of ASE, where sequence polymorphisms in regulatory regions affect transcription factor binding, chromatin accessibility, or epigenetic modifications, leading to differential allele expression [9]. These cis-regulatory modules (CRMs) include sequences that influence the timing, magnitude, and frequency of transcription through coordinated action of transcription factors and other binding partners [9].

In citrus hybrids, studies using a locally phased genome assembly revealed that approximately 30% of variation in allele-specific expression could be attributed to haplotype-associated factors, with allelic levels of chromatin accessibility and three histone modifications in gene bodies having the most influence [9]. Structural variants in promoter regions, particularly those involving hAT and MULE-MuDR DNA transposable elements, were significantly associated with allele-specific expression patterns [9].

Table 1: Quantitative Analysis of ASE Patterns Across Studies

| Study System | Total Genes Analyzed | Genes with ASE | Percentage with ASE | Primary Biological Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicken Embryonic Brain [8] | ~28,400 | 5,197 | 18.3% | Cis-regulatory variants |

| Chicken Embryonic Liver [8] | ~26,800 | 4,638 | 17.3% | Cis-regulatory variants |

| Citrus Hybrid [9] | Genome-wide | 30% of ASE variation | Attributable to haplotype-associated factors | Cis-regulatory variants & chromatin state |

Chromosomal and Dosage Effects

Sex chromosomes present unique cases of ASE due to dosage compensation mechanisms. In chickens, which have a ZW/ZZ sex determination system (females ZW, males ZZ), Z-linked gene expression is partially compensated between sexes, though the mechanism differs from mammalian X-chromosome inactivation [8]. This partial dosage compensation represents a form of chromosomal ASE that ensures balanced gene expression despite chromosomal heteromorphy.

Experimental Design for ASE Studies

RNA-Seq Experimental Considerations

A thorough and careful experimental design is the most crucial aspect of RNA-Seq experiments for ASE analysis [10]. Key considerations include:

Sample Size and Statistical Power: The sample size significantly impacts the quality and reliability of ASE results. Statistical power refers to the ability to identify genuine differential allele expression in naturally variable datasets [10]. While ideal sample sizes ensure optimal statistical outcomes, practical factors including biological variation, study complexity, cost, and sample availability must be considered [10].

Replicate Strategy: The number of replicates is directly related to sample size and required to account for variability within and between experimental conditions [10]:

- Biological Replicates: Independent samples for the same experimental group/condition that account for natural variation between individuals, tissues, or cell populations. At least 3 biological replicates per condition are typically recommended, with 4-8 replicates covering most experimental requirements [10].

- Technical Replicates: The same biological sample measured multiple times to assess technical variation from sequencing runs, laboratory workflows, or environmental factors [10].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for ASE Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function in ASE Analysis | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Kit [8] | cDNA library preparation for RNA-Seq | Maintains strand information; crucial for accurate transcript assignment |

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit [8] | Genomic DNA isolation | Enables parallel genotyping and haplotype phasing |

| mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit [8] | Total RNA extraction | Preserves RNA integrity (RIN > 9.8 recommended) |

| SIRV Spike-in Controls [10] | Internal standards for normalization | Quantifies technical variability and enables cross-sample comparison |

| PacBio Long-Read Sequences [9] | De novo genome assembly | Enables haplotype-resolved genome phasing for ASE analysis |

| 10x Genomics Linked-Reads [9] | Local haplotype phasing | Identifies phased variants for allele-specific read assignment |

Cross-Species Design Strategies

Reciprocal cross designs provide powerful systems for distinguishing parent-of-origin effects from sequence-based cis-regulatory effects [8]. In the chicken ASE study, researchers utilized two highly inbred experimental lines (Leghorn and Fayoumi) to create F1 reciprocal crosses (Leghorn × Fayoumi and Fayoumi × Leghorn), enabling clear discrimination of parental allele origins [8].

For heterozygous systems such as citrus hybrids, locally phased genome assemblies enable the dissection of linkages between cis-regulatory sequences and allele-specific gene expression [9]. This approach allows researchers to pair genes with allele-specific expression with haplotype-specific chromatin states, including levels of chromatin accessibility, histone modifications, and DNA methylation [9].

Methodologies and Protocols

RNA-Seq Library Preparation and Sequencing

The wet lab workflow begins with RNA extraction, followed by library preparation and sequencing. Key methodological considerations include:

RNA Extraction and Quality Control:

- Use extraction methods appropriate for your sample type (cell lines, tissues, blood, FFPE) [10]

- Assess RNA quality using Bioanalyzer 2100 or similar systems; RNA Integrity Numbers (RINs) > 9.8 are recommended for optimal results [8]

- Consider extraction-free RNA-Seq library preparation directly from lysates for large-scale studies using cell lines to save time and resources [10]

Library Preparation Selection:

- 3'-Seq approaches (e.g., QuantSeq, LUTHOR) benefit large-scale drug screens based on cultured cells aiming to assess gene expression patterns or pathways [10]

- Whole transcriptome approaches with mRNA enrichment or ribosomal rRNA depletion are required when isoforms, fusions, non-coding RNAs, or variants are of interest [10]

- Stranded protocols are essential for accurate transcript assignment and ASE analysis [8]

Sequencing Depth and Configuration:

- ~20-30 million reads per sample is often sufficient for standard differential expression analysis [11]

- Paired-end sequencing is strongly recommended over single-end layouts as more robust expression estimates can be obtained at effectively the same cost per base [12]

- 75-150 cycle paired-end protocols provide optimal balance between read length, cost, and mapping accuracy [8]

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for ASE RNA-Seq Analysis

Computational Analysis of ASE

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control: The computational analysis begins with quality assessment of raw sequencing data using tools like FastQC or multiQC to identify technical errors including adapter contamination, unusual base composition, or duplicated reads [11]. Following quality assessment, read trimming removes low-quality sequences and adapter contaminants using tools such as Trimmomatic, Cutadapt, or fastp [11].

Read Alignment and Quantification: Cleaned reads are aligned to a reference genome using splice-aware aligners such as STAR or HISAT2 [11] [12]. For ASE analysis, alignment to a customized reference genome with parental SNPs masked reduces reference bias [8]. Alternatively, pseudo-alignment with Kallisto or Salmon provides faster quantification without full base-by-base alignment [11] [12].

Variant Calling and Genotype Assignment: Variant calling from RNA-Seq data follows best practices using tools like the Genome Analysis ToolKit [8]. The workflow includes:

- Sorting aligned reads by chromosomal coordinates

- Marking duplicate reads for exclusion

- Realignment around indels

- Base quality score recalibration

- Variant calling with HaplotypeCaller

- Filtering low-quality calls (QD < 2), variants with strong strand bias (FS > 30), and SNP clusters (3 SNPs in 35 bp window) [8]

ASE Detection and Statistical Analysis: ASE detection requires allelic read counting at heterozygous sites followed by statistical testing for deviation from expected 1:1 expression ratio. Additional filters including read depth (DP ≥ 10) and genotype quality (GQ ≥ 30) ensure high-confidence genotype calls [8]. Allelic read counts less than total depth × 1% should be considered sequencing errors and reassigned as 0 [8].

Figure 2: Analytical Framework for ASE Detection

Multi-Omics Integration for ASE Studies

Integrating ASE analysis with epigenomic data provides mechanistic insights into cis-regulatory mechanisms. The combination of ATAC-seq for chromatin accessibility, ChIP-seq for histone modifications, and whole-genome bisulfite sequencing for DNA methylation enables comprehensive characterization of the epigenetic landscape influencing allele-specific expression [9] [13].

For single-cell multi-omic assays, a binarization and concatenation approach enables integrated analysis of scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data [13]. This method involves:

- Binarizing scRNA-seq data by converting expression values to 1 if raw read count > 0, otherwise 0

- Directly concatenating binarized scRNA-seq data with scATAC-seq data

- Applying term-frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) normalization

- Performing dimensionality reduction via singular value decomposition (Latent Semantic Indexing)

- Clustering cells based on integrated profiles [13]

Figure 3: Multi-Omic Data Integration Workflow

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

ASE analysis provides valuable applications throughout the drug discovery and development pipeline, from target identification to studying drug effects, mode-of-action, and monitoring disease progression and treatment responses [10].

Target Identification and Validation: ASE patterns can reveal genes under strong cis-regulatory control that may represent promising therapeutic targets. In agricultural species, ASE SNPs have been observed in response to Marek's disease virus in chickens, and selection using these ASE SNPs reduced disease incidence after one generation of selection [8].

Pharmacogenomics and Personalized Medicine: ASE of drug metabolizing enzymes or drug targets can contribute to interindividual variation in drug response. Identifying ASE patterns may help predict patient subgroups likely to respond to specific therapies or experience adverse effects.

Mode-of-Action Studies: Kinetic RNA sequencing with approaches such as SLAMseq can distinguish primary from secondary drug effects by globally monitoring RNA synthesis and decay rates [10]. This is particularly useful when assessing candidates during mode-of-action studies, though multiple time points and replicates per sample group are needed to generate relevant information [10].

Current Limitations and Future Directions

Despite advances in ASE analysis methodologies, current pipelines face notable limitations. Most pipelines fail to automate preprocessing, integrate multi-omic data, and support high-throughput single-cell sequencing [7]. Future advancements should prioritize the development of automated multi-omic workflows, implementing visualization options, and enhancing compatibility with single-cell technologies [7].

The integration of haplotype-resolved genetic and epigenetic landscapes enables researchers to dissect the interplay between genetic variants and molecular phenotypes, revealing cis-regulatory sequences with potential functional effects [9]. As demonstrated in citrus, trait-associated variants are enriched in regions of open chromatin, highlighting the potential for connecting regulatory variation to phenotypic outcomes [9].

By addressing current methodological gaps, next-generation ASE pipelines will offer deeper insights into the mechanisms of allele-specific expression regulation, advancing our understanding of its biological and clinical significance in both basic research and drug development applications [7].

Allele-specific expression (ASE) analysis is a powerful molecular technique that detects the preferential expression of one allele over the other in diploid organisms. While genes typically exhibit balanced expression of maternal and paternal alleles, exceptions to this rule provide critical insights into gene regulation with significant functional and clinical implications [7]. This imbalance can arise from various biological mechanisms including genomic imprinting, regulatory genetic variation such as expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs), allele-specific methylation, X-chromosome inactivation, and nonsense-mediated decay [14].

The advent of high-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has revolutionized the detection and quantification of ASE, enabling researchers to investigate cis-regulatory variation with unprecedented resolution [15]. This approach leverages heterozygous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within transcribed regions to distinguish expression between the two haplotypes, providing a direct window into regulatory mechanisms that often remain invisible to DNA-based genomic analyses alone [14] [15]. The strength of ASE analysis lies in its ability to detect functional regulatory variants with greater precision than broader expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) studies, supporting more informed clinical interpretations and therapeutic strategies [15].

Clinical Utility and Diagnostic Applications

Enhancing Diagnostic Yield in Rare Diseases

ASE analysis has demonstrated significant clinical utility by improving diagnostic yields in patients with rare genetic disorders. Recent research presented by Baylor Genetics at the American Society of Human Genetics 2025 Annual Meeting highlights how RNA sequencing for ASE assessment provides functional evidence that enables more accurate classification of variants identified through genome and exome sequencing [16].

In a comprehensive study of 3,594 consecutive clinical cases, researchers employed targeted RNA-seq to reclassify variants found via exome and genome sequencing. Remarkably, RNA-seq was able to reclassify half of eligible variants, providing crucial diagnostic clarity for patients and families navigating diagnostic odysseys [16]. The study revealed that over a third of RNA-seq eligible cases had noncoding variants detected by genome sequencing that would likely have been missed if only exome sequencing had been performed, underscoring the complementary value of incorporating transcriptomic analyses into standard diagnostic workflows.

Table 1: Diagnostic Utility of RNA-seq for Variant Reclassification

| Metric | Value | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Total cases reviewed | 3,594 | Demonstrates large-scale clinical application |

| Eligible cases for targeted RNA-seq | Varied by specific genes/diseases | Highlights case selection criteria |

| Variant reclassification rate | 50% of eligible variants | Substantial improvement in diagnostic interpretation |

| Cases with noncoding variants | >33% of RNA-seq eligible cases | Reveals limitation of exome-only sequencing |

A separate study conducted with the Undiagnosed Diseases Network further demonstrated the diagnostic power of transcriptome-wide RNA-sequencing (TxRNA-seq). Among 45 patients with previously undiagnosed clinical presentations across multiple specialties, TxRNA-seq supported a positive diagnostic result in 24% of cases (11 out of 45) by uncovering pathogenic mechanisms that DNA-based methods had failed to detect [16]. This research illustrates how ASE analysis through RNA-seq refines molecular interpretations in complex rare disease cases, delivering answers where conventional genomic approaches fall short.

Functional Characterization of Variants

Beyond simply increasing diagnostic rates, ASE analysis provides critical functional validation of variants of uncertain significance (VUS), transforming them into clinically actionable findings. By demonstrating that a particular allele exhibits skewed expression in relevant tissues, researchers and clinicians can obtain evidence supporting the pathogenicity or functional normality of genetic variants [15]. This is particularly valuable for noncoding variants, which constitute over 90% of genome-wide association study (GWAS) hits for common diseases but have historically been challenging to interpret [17].

The functional phenotyping of genomic variants through joint multiomic approaches represents a cutting-edge application of ASE analysis. Recently developed single-cell DNA–RNA sequencing (SDR-seq) technologies enable accurate determination of coding and noncoding variant zygosity alongside associated gene expression changes in thousands of single cells [17]. This innovative methodology provides a powerful platform to dissect regulatory mechanisms encoded by genetic variants, advancing our understanding of gene expression regulation and its implications for disease mechanisms such as cancer progression [17].

ASE Analysis Methodologies

Experimental Design and Workflow

A robust ASE analysis requires careful experimental planning and execution across multiple technical stages. The foundational step involves RNA sequencing of appropriate biological samples, with special attention to minimizing batch effects that can introduce artifactual findings [18]. Source material can include cells cultured in vitro, whole-tissue homogenates, or sorted cells, with the choice depending on the research question and biological context [18].

Following RNA extraction and library preparation, the analytical workflow proceeds through several critical stages:

- Read Quality Control: Assessing RNA-seq read quality using tools like FastQC and CollectRnaSeqMetrics to ensure data integrity [14] [18].

- Read Alignment: Mapping reads to a reference genome using SNP-tolerant aligners such as GSNAP or STAR with WASP filtering to reduce reference allele bias [14].

- ASE Read Counting: Quantifying allele-specific reads at heterozygous SNP positions using tools like GATK ASEReadCounter [14].

- Statistical Analysis: Identifying significant allelic imbalances while accounting for biological and technical variability [15].

- Functional Interpretation: Integrating ASE findings with complementary genomic datasets to derive biological insights [7].

Figure 1: Comprehensive ASE Analysis Workflow. The process begins with sample collection and proceeds through quality control, library preparation, sequencing, and computational analysis phases. Critical steps include SNP-tolerant alignment to minimize reference bias and specialized counting methods to quantify allelic expression.

The ASET Pipeline for ASE Analysis

The ASE Toolkit (ASET) represents a modern, end-to-end solution for SNP-level ASE quantification that addresses many challenges in reproducible ASE analysis [14]. Built using the Nextflow workflow manager, ASET streamlines the entire analytical process from raw short-read RNA-seq data to visualization and parent-of-origin testing [14].

Key features of ASET include:

- Modular Design: Implementation using Nextflow DSL2 syntax enables clean organization, simplified maintenance, and seamless integration of sub-workflows [14].

- Multiple Alignment Options: Incorporation of four commonly used alignment approaches tailored for ASE analysis (STAR+WASP, STAR+NMASK, GSNAP, and ASElux) [14].

- Strand-Specific Analysis: Generation of ASE count data in a strand-specific manner, enhancing accuracy for genes with antisense transcription [14].

- Contamination Estimation: Calculation of cross-contamination metrics, particularly valuable for clinical samples where maternal contamination is a concern [14].

- Parent-of-Origin Testing: Inclusion of specialized algorithms for detecting imprinting effects when phased SNP data is available [14].

Table 2: Key Capabilities of the ASET Pipeline

| Feature | Implementation | Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Workflow Management | Nextflow DSL2 | Enhanced reproducibility, scalability, and portability |

| Container Support | Docker/Singularity | Consistent execution across environments |

| Alignment Methods | Four specialized options | Flexibility for different experimental designs |

| Strand Specificity | Separate forward/reverse strand analysis | Improved accuracy for complex transcriptional units |

| Data Visualization | Integrated R library (ASEplot) | Streamlined exploratory data analysis |

| Parent-of-Origin Testing | Julia script for statistical analysis | Detection of imprinting effects |

ASET requires two primary input files: a sample sheet containing paths to read files and SNP VCFs, and a parameter configuration file for adjusting tool-specific settings and reference file paths [14]. The pipeline can operate in two modes: from_fastq for analysis starting with raw sequencing reads, and from_bam for analysis beginning with pre-aligned BAM files, providing flexibility for different starting points in the analytical process [14].

Research Applications and Biological Insights

Tissue-Specific Regulation in Stress Response

ASE analysis has revealed striking tissue-specific patterns of allelic imbalance in studies of stress response pathways. Recent research investigating six key limbic, diencephalon, and endocrine tissues in pigs identified over 1,000 genes per tissue exhibiting significant allele-specific expression, with 37 genes consistently showing ASE across all tissues [15]. This comprehensive analysis demonstrated how tissue context influences regulatory variation, with different biological pathways showing ASE in brain versus endocrine tissues.

The study employed Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) at the tissue group level, revealing that limbic and diencephalon modules were enriched for neural signaling pathways such as neuroactive ligand-receptor interactions and synaptic functions [15]. In contrast, endocrine modules showed enrichment for hormone biosynthesis and secretion pathways, including thyroid and growth hormone pathways [15]. These findings highlight how ASE analysis can uncover fundamental regulatory architectures underlying specialized tissue functions.

Among the 37 genes showing consistent ASE across tissues, ten displayed significant differences in allelic ratios between tissues, and seven were identified as known eQTLs in pig brain tissue within the FarmGTEx database [15]. These included genes with potential relevance to neurological function and disease, such as PINK1 (associated with Parkinson's disease) and SLA-DRB1 (swine leukocyte antigen class II) [15]. This intersection of ASE findings with established regulatory databases strengthens the biological interpretation of results and facilitates prioritization of candidates for functional validation.

Single-Cell ASE Analysis

The emerging field of single-cell ASE analysis represents a frontier in understanding cellular heterogeneity in gene regulation. Traditional bulk RNA-seq approaches measure average ASE across cell populations, potentially masking cell-to-cell variability in allelic expression [17]. Recent technological advances now enable ASE assessment at single-cell resolution, revealing how allelic imbalance may vary between individual cells of the same type [17].

The SDR-seq (single-cell DNA–RNA sequencing) method represents a significant innovation in this space, enabling simultaneous profiling of up to 480 genomic DNA loci and genes in thousands of single cells [17]. This approach allows for accurate determination of coding and noncoding variant zygosity alongside associated gene expression changes in the same cell, providing unprecedented resolution for linking genotype to phenotype [17]. In proof-of-concept experiments, SDR-seq demonstrated robust detection of both DNA variants and RNA expression with minimal cross-contamination between cells, achieving over 95% sample-specific barcode accuracy [17].

Application of SDR-seq to primary B cell lymphoma samples revealed that cells with higher mutational burden exhibited elevated B cell receptor signaling and tumorigenic gene expression [17]. This illustrates the power of single-cell multiomic approaches for dissecting heterogeneity in complex biological systems and disease states, potentially uncovering molecular mechanisms that drive pathological processes in subsets of cells.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful ASE analysis requires careful selection of laboratory reagents and computational tools. The following table summarizes key solutions utilized in the methodologies discussed throughout this application note.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions for ASE Analysis

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) | Total RNA purification | High-quality RNA extraction from tissue samples [15] |

| Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep | RNA library preparation | Construction of sequencing-ready libraries [15] |

| NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Kit | mRNA enrichment | Selection of polyadenylated transcripts prior to cDNA synthesis [18] |

| NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit | cDNA library preparation | Generation of Illumina-compatible sequencing libraries [18] |

| Trimmomatic | Read quality control and adapter trimming | Preprocessing of raw sequencing reads [14] |

| STAR aligner with WASP mode | SNP-tolerant read alignment | Reduction of reference allele mapping bias [14] |

| GATK ASEReadCounter | Allele-specific read counting | Quantification of expression from each allele [14] |

| ASEplot (R library) | Data visualization | Generation of publication-quality ASE figures [14] |

| Cell fixation reagents (PFA/glyoxal) | Cell preservation for single-cell assays | Maintenance of nucleic acid integrity in SDR-seq [17] |

Allele-specific expression analysis has evolved from a specialized research technique to an essential component of comprehensive genomic studies, providing functional insights that complement DNA-based approaches. The clinical utility of ASE is demonstrated by its ability to increase diagnostic yields in rare diseases and functionally characterize variants of uncertain significance [16]. Methodological advances, including end-to-end pipelines like ASET and innovative single-cell multiomic approaches such as SDR-seq, are addressing previous limitations and expanding the scope of biological questions accessible through ASE analysis [14] [17].

Despite these advances, challenges remain in the field. Current pipelines often lack complete automation, integrated multi-omic data integration, and comprehensive support for single-cell sequencing technologies [7]. Future developments addressing these limitations will further enhance the accessibility and power of ASE analysis. As these methodologies continue to mature and integrate with other functional genomic approaches, ASE analysis will play an increasingly central role in unraveling the complexity of gene regulation and its implications for human health and disease.

Allele-specific expression (ASE) analysis is a powerful transcriptional approach that detects the relative abundance of alleles at heterozygous loci, serving as a direct proxy for cis-regulatory variation that shapes individual transcriptomes and proteomes [4]. In diploid organisms, genes typically exhibit balanced expression of maternal and paternal alleles; however, ASE occurs when one allele is preferentially or exclusively expressed due to various biological mechanisms [7]. This imbalance provides crucial functional evidence for how genetic variants influence transcription and ultimately contribute to phenotypic diversity and disease susceptibility.

The biological significance of ASE stems from its ability to uncover regulatory processes often invisible to conventional genomic analyses. ASE can arise from multiple mechanisms including genomic imprinting, regulatory genetic variation and expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs), allele-specific methylation or chromatin remodeling, X-chromosome inactivation, and nonsense-mediated decay [14]. High-throughput RNA-Seq technology has become the primary method for measuring ASE genome-wide, enabling researchers to quantify allelic imbalances with unprecedented precision and scale [14] [19].

When framed within broader ASE RNA-seq research, this application note highlights how ASE analysis provides an additional layer of functional interpretation beyond DNA-level variation. By focusing on stress response and disease pathogenesis, we demonstrate how ASE reveals active regulatory mechanisms in relevant biological contexts, bridging the gap between genetic predisposition and functional pathological outcomes.

Key Applications of ASE Analysis

Uncovering cis-Regulatory Mechanisms in Complex Diseases

ASE analysis has proven particularly valuable for dissecting the cis-regulatory architecture of complex genetic diseases where conventional approaches like genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and differential gene expression analyses show limited explanatory power. In dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), for instance, ASE analysis revealed an overrepresentation of known DCM-associated genes among significantly imbalanced transcripts, with 74% of established DCM genes showing significant allelic imbalance compared to 38% of other genes [4]. This striking enrichment demonstrates how ASE pinpoints genes with direct functional roles in disease pathogenesis.

The power of ASE lies in its ability to detect regulatory effects regardless of total gene expression levels or direct variant-phenotype correlations, making it especially useful for identifying low-frequency regulatory variants with potentially large effect sizes [4]. Furthermore, ASE analysis on a cohort of 87 well-phenotyped DCM patients revealed candidate genes that had not been associated with DCM through conventional GWAS or differential expression studies, highlighting its unique discovery potential [4]. The detection of allelic imbalance can be performed on a per-sample basis, which allows for the discovery of variants with low minor allele frequencies that would typically be filtered out in population-based association studies [4].

ASE in Stress Response Pathways

ASE analysis provides unique insights into how organisms respond to environmental and cellular stressors at the regulatory level. While the search results do not contain specific studies of ASE in human stress response, network biology approaches applied to bacterial stress responses have revealed common central mediators across multiple pathogens [20]. Although these bacterial studies focus on total gene expression rather than ASE, they demonstrate the principle that stress responses activate conserved molecular pathways—many of which likely exhibit allele-specific regulation in diploid organisms.

In human contexts, ASE likely contributes to stress response heterogeneity through allele-specific effects on key signaling pathways. The integrated stress response (ISR), for example, represents a promising area for future ASE investigations, particularly given its activation in various disease states [21]. Single-cell RNA-sequencing of PBMCs from patients with STING-associated vasculopathy with onset in infancy (SAVI) revealed disease-associated monocytes with elevated integrated stress response, suggesting that ASE analysis might uncover allele-specific contributions to this dysregulated stress pathway [21].

Advancing Molecular Diagnostics

ASE analysis has significant implications for clinical diagnostics, particularly for rare genetic disorders. RNA sequencing has become key to complementing exome and genome sequencing for variant interpretation, with studies demonstrating a 7-36% increase in diagnostic yield when transcriptomic analysis is incorporated [22]. ASE can provide functional evidence for the pathogenicity of non-coding and regulatory variants that are often classified as variants of uncertain significance (VUS) [22].

In neurodevelopmental disorders, a minimally invasive RNA-seq protocol using short-term cultured peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) successfully detected aberrant splicing and allele-specific expression, allowing reclassification of seven variants [22]. This approach is particularly valuable for neurodevelopmental disorders, as up to 80% of genes in intellectual disability and epilepsy panels are expressed in PBMCs [22]. The ability to detect allele-specific expression and splicing defects makes ASE analysis a powerful tool for resolving inconclusive genetic testing results.

Table 1: Key Applications of ASE Analysis in Disease Research

| Application Area | Key Findings | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Complex Cardiac Disease | 74% of established DCM genes showed significant ASE versus 38% of other genes [4] | ASE identifies genes with direct functional roles in disease pathogenesis |

| Molecular Diagnostics | 7-36% increase in diagnostic yield when incorporating RNA-seq [22] | ASE provides functional evidence for variant pathogenicity |

| Neurodevelopmental Disorders | ~80% of ID/epilepsy panel genes expressed in PBMCs [22] | Enables minimally invasive diagnostic ASE analysis |

| Disease Subtyping | Differential ASE patterns between clinical phenogroups [4] | Reveals regulatory contributions to disease heterogeneity |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

End-to-End ASE Analysis Pipeline (ASET Framework)

The ASE Toolkit (ASET) provides a comprehensive, modular pipeline for SNP-level ASE quantification from RNA-Seq data [14]. Built using Nextflow for enhanced reproducibility and scalability, ASET integrates multiple computational steps into a cohesive workflow that includes read alignment, read counting, data visualization, and statistical testing [14]. The pipeline accepts raw short-read RNA-Seq data and produces annotated ASE data tables with contamination estimates.

ASET's alignment phase incorporates four distinct approaches tailored for ASE analysis: (1) STAR + WASP alignment with WASP filtering to reduce reference allele bias; (2) STAR + NMASK using an N-masked genome at SNP sites; (3) GSNAP in SNP-tolerant mode; and (4) ASElux for ultra-fast alignment and counting [14]. Each method offers different trade-offs between accuracy, computational requirements, and need for phased haplotype data. Following alignment, the pipeline performs strand-specific read counting using GATK ASEReadCounter, annotation with gene and exon information, and estimation of cross-contamination levels [14].

The entire workflow is containerized through Docker or Singularity, ensuring portable execution across different computational environments while maintaining version-controlled software dependencies [14]. This end-to-end automation addresses a critical gap in ASE analysis, as most existing pipelines lack comprehensive integration of preprocessing, analysis, and visualization steps [7].

Specific Protocol: ASE Analysis in Dilated Cardiomyopathy

For researchers investigating complex phenotypes like dilated cardiomyopathy, the following protocol provides a robust framework for individual and population-level ASE analysis:

Step 1: RNA Sequencing Data Preprocessing Begin with quality control of raw RNA-Seq reads using FastQC and multiQC to identify adapter contamination, unusual base composition, or duplicate reads [11]. Perform read trimming with Trimmomatic or Cutadapt to remove low-quality ends and adapter sequences [11]. Align cleaned reads to a reference transcriptome using splice-aware aligners like STAR or HISAT2, followed by post-alignment QC with SAMtools or Qualimap to remove poorly aligned or multimapping reads [11].

Step 2: ASE Quantification and Statistical Analysis Generate allele-specific counts at heterozygous SNPs using GATK ASEReadCounter with appropriate quality filters (base quality ≥20, mapping quality ≥10) [14] [4]. Represent ASE as the absolute deviation from a heterozygous biallelic frequency of 0.5, following standard guidelines [4]. Establish an ASE score threshold (empirically determined as 0.966 in one study) to distinguish true heterozygous loci from homozygous loci with RNA sequencing artifacts [4].

Step 3: Individual and Population-Level Analysis For each sample, identify statistically significantly imbalanced SNPs using a false discovery rate (FDR) cutoff of q < 0.05 [4]. At the population level, analyze "shared imbalance" patterns where genes show significant imbalance for at least one locus across multiple subjects [4]. Perform differential ASE analysis between clinical subgroups using non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney U for two groups, Kruskal-Wallis for multiple groups) to identify regulatory differences between phenogroups [4].

Step 4: Functional Interpretation and Visualization Conduct gene ontology enrichment analysis on genes showing significant ASE using tools like topGO [4]. Generate protein-protein interaction networks from significantly imbalanced genes using STRING and Cytoscape to identify functional modules [4] [20]. Create visualizations including Manhattan plots of ASE p-values, boxplots of differential ASE between phenogroups, and networks of functionally related genes with median ASE scores [4].

Diagram 1: Comprehensive ASE analysis workflow for complex disease research, illustrating the sequence from raw data processing to biological interpretation.

Specialized Protocol: Clinical ASE Analysis for Rare Disorders

For diagnostic laboratories implementing ASE analysis, particularly for rare neurodevelopmental disorders, the following protocol enables detection of allelic imbalance and splicing defects:

Sample Preparation and NMD Inhibition Isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) using standard Ficoll gradient separation [22]. Culture cells for short-term expansion (2-3 days) with and without cycloheximide (CHX) treatment (100μg/mL for 4-6 hours) to inhibit nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) [22]. Validate NMD inhibition effectiveness by quantifying SRSF2 NMD-sensitive transcript levels, expecting an increase from ~4.5% to ~8.5% exon 3 spanning reads in CHX-treated samples [22].

Library Preparation and Sequencing Extract total RNA using PAXgene Blood RNA Kit, assessing RNA integrity number (RIN) ≥7 via Agilent Bioanalyzer [23] [22]. Prepare libraries using Illumina's TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Kit with Ribo-Zero Gold for ribosomal RNA depletion [23]. Sequence on Illumina platforms to a minimum depth of 30 million paired-end reads per sample [11].

Bioinformatic Analysis and Variant Interpretation Process RNA-seq data through a standardized ASE pipeline (e.g., ASET or custom implementation) [14] [22]. Utilize FRASER for detecting aberrant splicing and OUTRIDER for expression outlier analysis [22]. For candidate variants, verify allele-specific expression patterns and compare to in silico predictions. Integrate ASE findings with exome or genome sequencing data for comprehensive variant classification according to ACMG/AMP guidelines [22].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for ASE Studies

| Reagent/Cell Type | Specific Application | Function and Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| PBMCs (Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells) | Accessible tissue for clinical ASE studies [22] [21] | Express ~80% of intellectual disability/epilepsy panel genes; minimally invasive source |

| Cycloheximide (CHX) | NMD inhibition [22] | Blocks nonsense-mediated decay to detect transcripts with premature termination codons |

| PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes | RNA stabilization [23] | Preserves RNA integrity during blood sample storage and transport |

| TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Kit | Library preparation [23] | Maintains strand information crucial for accurate ASE quantification |

| SRSF2 NMD-sensitive transcript | Internal control for NMD inhibition [22] | Endogenous indicator of NMD inhibition effectiveness |

Technical Considerations and Analytical Framework

Pipeline Selection and Benchmarking

Choosing an appropriate analysis pipeline is crucial for robust ASE detection. Current benchmarks evaluate pipelines based on multiple criteria including input requirements, haplotype phasing support, statistical approaches, and visualization capabilities [7]. While numerous ASE analysis tools exist, most exhibit significant limitations including lack of end-to-end automation, restricted multi-omics integration, and insufficient support for single-cell sequencing technologies [7].

The ASET pipeline addresses several of these gaps by providing a comprehensive workflow that integrates SNP-tolerant alignment, strand-specific read counting, contamination estimation, and parent-of-origin testing [14]. When comparing alignment methods, studies indicate that STAR+WASP alignment combined with ASEReadCounter counting effectively reduces reference allele bias, making it suitable for diverse applications [14]. For large-scale studies, ASElux offers speed advantages but sacrifices some analytical flexibility [14].

Diagram 2: ASE pipeline components and compatibility, showing the relationships between alignment methods, counting tools, and downstream analysis options.

Quality Control and Contamination Assessment

Rigorous quality control is essential for reliable ASE quantification. Key QC metrics include sequencing depth (minimum 20-30 million reads per sample for standard differential expression analysis), RNA integrity (RIN ≥7), and alignment rates [11]. For ASE-specific applications, effective coverage at heterozygous SNP sites is particularly important, as low coverage reduces power to detect modest allelic imbalances [14].

ASET incorporates contamination estimation by calculating the average non-alternative-allele frequency at homozygous SNP sites and non-reference-allele frequency at reference sites [14]. This is especially crucial for tissue samples where maternal contamination might confound results, such as in placental studies [14]. For clinical applications, establishing ASE score thresholds through receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) analysis against known heterozygous and homozygous loci helps distinguish true allelic imbalance from technical artifacts [4].

Statistical Framework and Multiple Testing

Appropriate statistical handling is paramount for ASE analysis due to the high dimensionality of transcriptomic data. The standard approach involves testing for significant deviation from the expected 0.5 reference allele fraction at each heterozygous site using binomial or beta-binomial tests [4]. Multiple testing correction using false discovery rate (FDR) control (e.g., Benjamini-Hochberg procedure) is then applied across all tested SNPs [4].

For population-level analyses, combining evidence across individuals increases power to detect consistent ASE patterns. The "shared imbalance" approach identifies genes that show significant ASE in multiple samples, highlighting regulatory hotspots with potential biological importance [4]. Differential ASE analysis between clinical subgroups employs non-parametric tests that are robust to violations of normality assumptions common in expression data [4].

RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) has revolutionized transcriptome analysis, enabling an unprecedented detailed inspection of mRNA levels within cells [24]. For researchers focused on allele-specific expression (ASE), RNA-Seq offers a particularly powerful advantage: the ability to comprehensively detect and quantify expressed genetic variants directly from transcriptomic data. This capability moves beyond simple gene expression profiling, allowing scientists to investigate cis-regulatory variation and its functional consequences in development, disease, and trait manifestation [15]. In the context of a broader thesis on ASE, understanding this advantage is fundamental. Unlike DNA-based genotyping methods that identify variants regardless of their transcriptional activity, RNA-Seq provides a functional filter, revealing which variants are actively transcribed and potentially contribute to phenotypic outcomes. This application note details the protocols and methodologies that make RNA-Seq an indispensable tool for uncovering the dynamics of allele-specific expression, with a particular emphasis on its application in detecting expressed variants in complex biological systems, including cancer [25].

The utility of RNA-Seq for variant detection and ASE analysis is demonstrated by its performance in recent studies. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings that highlight its capabilities and analytical power.

Table 1: Summary of Allele-Specific Expression (ASE) Findings in a Multi-Tissue Study [15]

| Analysis Category | Finding | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| ASE per Tissue | >1,000 genes per tissue showed ASE. | Demonstrates widespread cis-regulatory variation across different tissue types. |

| Consistent ASE Genes | 37 genes consistently showed ASE across all tissues. | Indicates a core set of genes under consistent cis-regulatory control. |

| Genes with Differential Allelic Ratios | 10 of the 37 consistent ASE genes. | Suggests potential tissue-specific modulation of allelic expression for a subset of genes. |

| eQTL Validation | 7 genes (PINK1, TTLL1, SLA-DRB1, HEBP1, ANKRD10, LCMT1, SDF2) were validated as eQTLs. | Confirms the functional relevance of ASE findings and links them to known regulatory genetic variants. |

Table 2: Performance of VarRNA in Classifying Variants from Tumor RNA-Seq Data [25]

| Performance Metric | Outcome | Implication for ASE and Variant Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Variant Detection vs. Exome Sequencing | Identified ~50% of variants found by exome sequencing. | RNA-Seq provides substantial overlap with DNA-level variant calls while also capturing unique transcriptional information. |

| Unique Variant Detection | Detected unique RNA variants absent in paired DNA exome data. | Highlights RNA-Seq's ability to uncover RNA editing events and other transcript-specific phenomena. |

| Allele-Specific Expression | Revealed variant allele frequencies (VAFs) distinct from DNA data, particularly in oncogenes. | Directly demonstrates ASE, where the expression of one allele is disproportionately higher, which can be crucial in cancer pathogenesis. |

Experimental Protocols for Variant and ASE Analysis from RNA-Seq

A robust analysis pipeline is crucial for the reliable detection of variants and ASE from RNA-Seq data. The following sections outline a standardized workflow, from initial quality control to advanced variant classification.

Core RNA-Seq Data Processing Workflow

The initial steps of RNA-Seq analysis are critical for generating high-quality, aligned data suitable for variant calling [24] [26].

Quality Control and Trimming

- Software Tools:

fastp[27] orTrim Galore(which integratesCutadaptandFastQC) [15] [27] are recommended for their efficiency and comprehensive reporting. - Procedure: Use these tools to remove adapter sequences and trim low-quality bases from the raw sequencing reads (FASTQ files). Generate and inspect quality control reports to ensure data integrity before proceeding.

fastphas been shown to significantly enhance processed data quality [27].

- Software Tools:

Alignment to a Reference Genome

- Software Tools:

HISAT2[24] orSTAR[25] are state-of-the-art splice-aware aligners. - Procedure: Map the high-quality trimmed reads to the appropriate reference genome (e.g., GRCh38 for human). For RNA-Seq, it is essential to use aligners that can handle reads spanning splice junctions. The output is a Sequence Alignment Map (SAM) or Binary Alignment Map (BAM) file.

- Software Tools:

Post-Alignment Processing

Variant Calling and Filtering from RNA-Seq Data

This stage focuses on identifying genetic variants from the processed RNA-Seq data.

- Variant Calling: Use

GATK HaplotypeCaller[25] on the processed BAM files. Key parameters for RNA-Seq include enabling--dont-use-soft-clipped-basesto reduce false positives and setting--max-reads-per-alignment-startto 0 to disable down-sampling [25]. - Variant Filtering: The initial variant call set requires stringent filtering. Tools like

SNPiR[25] orRVBoost[25] can be employed to remove false positives arising from mapping errors near splice sites or repetitive regions.

Advanced Classification and ASE Analysis

For specialized applications like cancer, further classification is needed.

- Somatic vs. Germline Classification:

VarRNAis a novel method that uses two machine learning models (XGBoost) to classify variants called from tumor RNA-Seq data as artifact, germline, or somatic without a matched normal comparator [25].- Model 1: Distinguishes true variants from sequencing or alignment artifacts.

- Model 2: Classifies true variants as either germline or somatic.

- Allele-Specific Expression (ASE) Analysis: To quantify the imbalance in expression between two alleles, tools like

ASEP[15] can be used.ASEPutilizes a generalized linear mixed-effects model that accounts for correlations of SNPs within the same gene, enabling robust ASE detection across multiple individuals [15]. This analysis directly tests for differences in the expression levels of the two alleles of a heterozygous gene.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational workflow for variant detection and ASE analysis from RNA-Seq data, incorporating the key protocols described above.

Successful variant and ASE analysis relies on a combination of bioinformatics tools, reference databases, and computational resources.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-Seq Based Variant and ASE Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| STAR/HISAT2 | Aligner Software | Precisely maps RNA-Seq reads to a reference genome, correctly handling spliced transcripts. |

| GATK | Variant Caller Software | A toolkit for variant discovery; its HaplotypeCaller is adapted for calling SNPs and indels from RNA-Seq data. |

| VarRNA | Classification Software | Machine learning-based tool that classifies RNA-Seq variants as germline, somatic, or artifact without a matched normal. |

| ASEP | Statistical Software | Detects allele-specific expression across a population using a generalized linear mixed-effects model. |

| Reference Genome (e.g., GRCh38) | Reference Data | The standard genomic sequence against which reads are aligned and variants are called. |

| dbSNP Database | Reference Data | A public repository of known genetic variants used for base recalibration and variant filtering. |

| FarmGTEx/PigGTEx | Reference Database | Provides an atlas of regulatory variants for domestic species, enabling the validation of ASE findings in a farm animal context [15]. |

ASE Analysis Pipelines: From Raw Data to Biological Insights

Allele-specific expression (ASE) analysis is a powerful approach in functional genomics that measures the differential expression between the two alleles of a gene in a diploid individual. This phenomenon provides crucial insights into cis-regulatory genetic variation, where factors such as genomic imprinting, allele-specific methylation, regulatory genetic variants (eQTLs), and X-chromosome inactivation cause one allele to be expressed at a different level than the other [14] [5]. Unlike standard expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) analyses, ASE offers a unique advantage by being less susceptible to confounding from environmental and technical conditions, as both alleles within the same individual share the same cellular trans-environment [5]. The advent of high-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has enabled genome-wide quantification of ASE, but this process involves multiple complex computational steps, creating significant challenges for reproducibility, scalability, and accessibility for molecular and biomedical scientists [14] [28].

Traditionally, ASE analysis requires the integration of several specialized tools for read alignment, read counting, statistical testing, and visualization. Early approaches often aligned reads to a standard reference genome, which introduced systematic alignment biases toward the reference allele [6]. To address this, sophisticated methods were developed, including SNP-tolerant aligners, personalized diploid genomes, and alignment filtering techniques [14]. However, combining these methods into a coherent, reproducible workflow remained challenging. Most existing pipelines lack end-to-end functionality, often omitting critical components such as dedicated visualization tools or statistical frameworks for specific biological questions like parent-of-origin effects (PofO) [14] [7]. Furthermore, the emergence of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) technologies has introduced new dimensions of cellular heterogeneity and analytical complexity, for which support in conventional ASE pipelines is often limited [5] [7].

The ASET Pipeline: An Integrated Solution

The ASE Toolkit (ASET) is a modern, end-to-end pipeline designed to streamline SNP-level ASE data generation, visualization, and interpretation from short-read RNA-seq data. Developed to address the fragmentation in existing tools, ASET integrates a modular workflow built with Nextflow, an R library (ASEplot) for data visualization, and a Julia script for parent-of-origin (PofO) testing [14] [28]. This integrated design provides a complete and easy-to-use solution that transforms raw sequencing data into annotated ASE counts and publication-ready figures, thereby facilitating discovery for researchers who may not possess extensive bioinformatics expertise.

ASET distinguishes itself from other available pipelines through several key capabilities. First, it incorporates four distinct alignment approaches specifically tailored for ASE analysis, allowing users to select the most appropriate method for their data. Second, it generates strand-specific ASE count data, which provides finer resolution for interpreting regulatory mechanisms. Third, it includes built-in modules for contamination estimation, a critical quality control step, particularly in clinical or heterogeneous tissue samples. Finally, and uniquely among comparable pipelines, ASET directly integrates data visualization and specific statistical testing for parent-of-origin effects, which are essential for studies of genomic imprinting [14]. A direct comparison of ASET against other pipelines highlights its comprehensive feature set (see Table 1).

Table 1: Comparison of ASE Analysis Pipelines and Their Capabilities

| Feature | ASET | gtex-pipeline | snakePipes | Allele-specific RNA-seq workflow | RNAseq-VAX | as_analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workflow System | Nextflow | Cromwell | Snakemake | Nextflow | Nextflow | Snakemake |

| ASE-specific Aligners | GSNAP, STAR+WASP, STAR with N-masked ref, ASElux | STAR or HISAT2 with N-masked ref | STAR with N-masked ref | Not Available | Not Available | STAR+WASP |

| Strand-specific Analysis | Supported | Not Available | Supported | Not Available | Not Available | Not Available |

| Read Counting Level | SNP-level | SNP & Haplotype-level | Gene-level | Gene-level | SNP-level | SNP-level |

| Contamination Estimate | Supported | Not Available | Not Available | Not Available | Not Available | Not Available |

| Visualization Plots | Tailored for ASE | Not Available | Tailored for QC and differential expression | Not Available | Not Available | Not Available |

| Parent-of-Origin Testing | Supported | Not Available | Not Available | Not Available | Not Available | Not Available |

Adapted from [28]

Pipeline Architecture and Workflow

ASET leverages the Nextflow workflow manager, known for its scalability, reproducibility, and portability across different computing environments, from local machines to high-performance clusters and cloud platforms [14]. Its use of containerization technologies like Docker and Singularity ensures that all software dependencies are locked, guaranteeing consistent results across runs [14] [28]. The pipeline accepts two primary input files: a sample sheet containing paths to the read files and SNP VCFs, and a parameter configuration file.

The pipeline can be executed in two modes, providing flexibility depending on the starting point of the analysis:

from_fastq: This mode begins with raw FASTQ files and performs comprehensive read quality control, adapter trimming, and SNP-aware alignment.from_bam: This mode accepts pre-aligned BAM files, skipping the initial alignment steps and proceeding directly to alignment filtering and deduplication [14].

A key strength of ASET is its modular design, which integrates multiple specialized tools into a cohesive workflow. The following diagram illustrates the major stages of the ASET pipeline from raw data to final output.

Detailed Experimental Protocol with ASET

Input Data Preparation and Quality Control

The initial step in any robust ASE analysis is the preparation of high-quality input data. For ASET, this requires a sample sheet in CSV format detailing the paths to the sequencing read files (FASTQ) for each sample and a VCF file containing the known single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for each individual [14]. The accuracy of ASE quantification is highly dependent on the quality of the sequencing data and the effective coverage at the assayed heterozygous SNPs [14] [28].

The first automated analytical step is comprehensive read quality control. ASET employs FastQC to provide a preliminary assessment of read quality, nucleotide distribution, and adapter contamination. This is followed by Trimmomatic, which performs adapter trimming and removes low-quality bases from the read ends, thereby increasing the mapping rate and reducing alignment errors [14] [29]. Finally, CollectRnaSeqMetrics from the GATK toolkit generates additional RNA-specific QC metrics. All these metrics are aggregated into a single, interactive MultiQC report, allowing the researcher to quickly assess data quality across all samples and identify any potential outliers before proceeding to alignment [14].

SNP-aware Read Alignment and Filtering

A critical challenge in ASE analysis is alignment bias, where reads carrying the non-reference allele are mismapped or discarded, leading to inaccurate allelic ratios [14] [30]. ASET directly addresses this by providing four distinct alignment sub-workflows, selected via the mapper parameter in the configuration file [14]:

- STAR + WASP: Alignment is performed using the STAR aligner with its integrated

--waspOutputModeto enable WASP filtering. This method identifies reads that change their mapping location after in-silico allele swapping and flags them to reduce reference bias [14] [28]. - STAR + NMASK: The reference genome is first "N-masked" at all known SNP positions, forcing the aligner to be unbiased at these sites during the mapping process.

- GSNAP: This SNP-tolerant aligner uses a database of known SNPs to consider alternative alleles as matches during alignment, rather than penalizing them as mismatches [14].

- ASElux: An ultra-fast aligner and counter that builds a reduced, SNP-aware index of only the genic regions containing SNPs, to which reads are aligned and counted directly [14].

Following alignment, the resulting BAM files are processed through several post-alignment steps. Reads are filtered based on mapping quality flags, and potential PCR duplicates are marked and removed using GATK MarkDuplicates to prevent over-representation of identical DNA fragments. A unique feature of ASET is its ability to split the deduplicated reads into separate alignment files based on strand, which requires the user to specify the library's strandedness [14].

Allele-Specific Read Counting and Downstream Analysis