A-to-I RNA Editing: From Molecular Mechanism to Therapeutic Application in Biomedicine

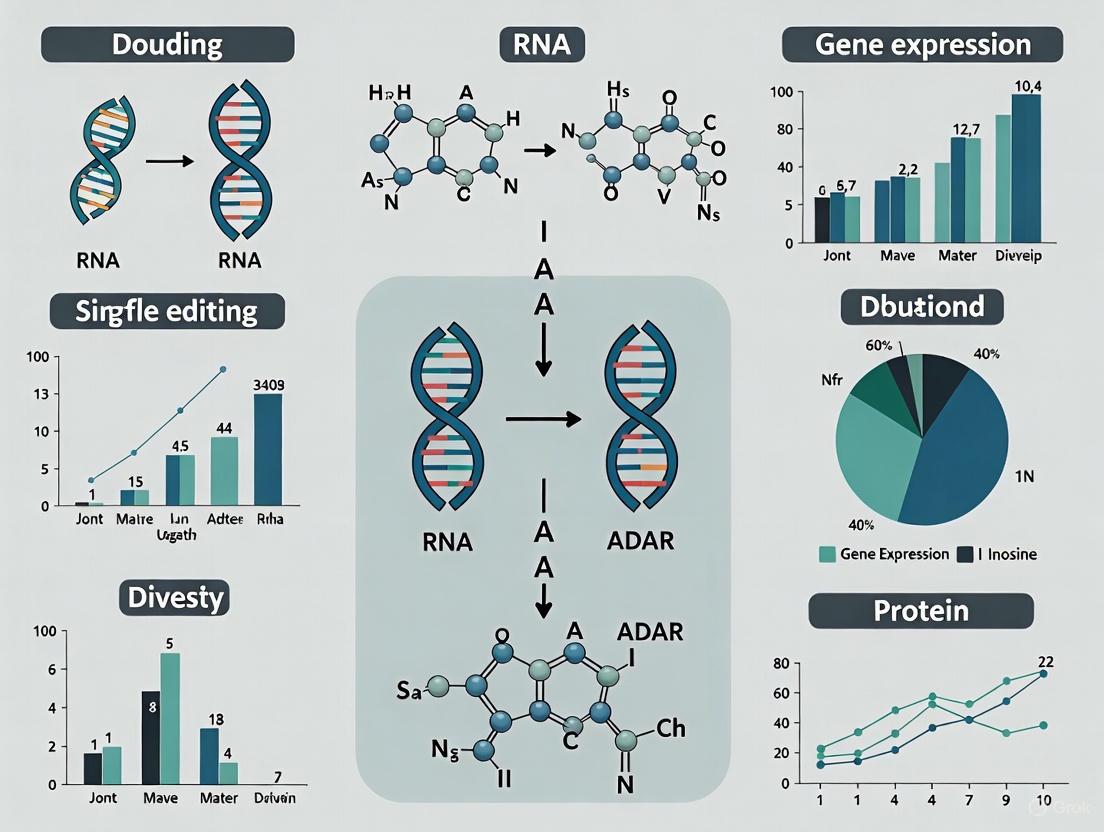

Adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) RNA editing, catalyzed by ADAR enzymes, represents the most prevalent post-transcriptional modification in humans, dynamically expanding transcriptome and proteome diversity.

A-to-I RNA Editing: From Molecular Mechanism to Therapeutic Application in Biomedicine

Abstract

Adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) RNA editing, catalyzed by ADAR enzymes, represents the most prevalent post-transcriptional modification in humans, dynamically expanding transcriptome and proteome diversity. This comprehensive review explores the fundamental mechanisms of ADAR-mediated editing, from enzyme structure and catalytic function to its critical roles in innate immunity, neural function, and cancer pathogenesis. We examine cutting-edge computational and biochemical methodologies for editing detection, alongside emerging therapeutic platforms leveraging programmable RNA editing for disease mutation correction. The article further addresses key challenges in editing specificity, efficiency, and delivery optimization, while validating biological significance through evolutionary conservation and clinical correlation studies. For researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis provides essential insights into RNA editing's transformative potential for precision medicine and therapeutic development.

The ADAR Enzyme Family and Fundamental Mechanisms of A-to-I RNA Editing

Adenosine deaminases acting on RNA (ADARs) are a conserved family of enzymes that catalyze the hydrolytic deamination of adenosine to inosine (A-to-I) in double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) substrates [1] [2]. This post-transcriptional modification, recognized as guanosine by cellular machinery, represents a fundamental mechanism for expanding transcriptome and proteome diversity [1] [3]. The ADAR-mediated RNA editing pathway plays critical roles in neurological function, innate immune regulation, and hematopoietic development [4] [5] [6]. Understanding the intricate relationship between ADAR protein architecture, including their catalytic domains and RNA-binding motifs, and their biological functions provides essential insights for both basic science and therapeutic development. This technical guide comprehensively details the structural composition, functional domains, and experimental methodologies central to ADAR research, framed within the broader context of A-to-I RNA editing mechanisms and significance.

ADAR Gene Family and Evolutionary History

The ADAR gene family is evolutionarily conserved across metazoa but absent in plants, fungi, and yeast [1] [2]. Mammals possess three ADAR genes: ADAR1 (expressed in most tissues), ADAR2 (primarily neuronal), and ADAR3 (brain-specific and catalytically inactive) [1] [2] [3]. The evolutionary model suggests ADARs originated from adenosine deaminases acting on tRNA (ADATs) through gene duplication and acquisition of double-stranded RNA binding domains (dsRBDs), enabling recognition of dsRNA substrates [2]. Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans possess one and two ADAR genes respectively, providing valuable model systems for functional studies [1] [5].

Table 1: ADAR Family Members Across Species

| Species | ADAR Genes | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Human | ADAR1, ADAR2, ADAR3 | Three genes; ADAR1/2 active, ADAR3 inactive; tissue-specific expression [1] [2] |

| Mouse | ADAR1, ADAR2, ADAR3 | Similar organization to human; essential for development [4] |

| Drosophila | dADAR | Single ADAR2-like gene; nervous system expression [1] [2] |

| C. elegans | adr-1, adr-2 | Two genes; expressed in all developmental stages [5] [2] |

| Zebrafish | Four ADAR genes | Model for developmental studies [2] |

Domain Architecture and Structural Features

Common Domain Organization

All functional ADAR enzymes share a conserved modular architecture consisting of:

- N-terminal double-stranded RNA binding domains (dsRBDs): Variable number (1-3 in mammals) that mediate substrate recognition and binding [1] [2]. These domains adopt a conserved α-β-β-β-α configuration [3].

- C-terminal catalytic deaminase domain: Highly conserved region containing the enzymatic active site [1] [2].

Table 2: Domain Composition of Human ADAR Proteins

| ADAR Protein | dsRBDs | Z-DNA Binding Domains | Other Domains | Catalytic Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADAR1 p150 | 3 | Zα and Zβ (functional) | Nuclear export signal [7] | Active [4] [3] |

| ADAR1 p110 | 3 | None (truncated) | - | Active [4] [2] |

| ADAR2 | 2 | None | Arginine-rich ssRNA binding domain [3] | Active [1] [2] |

| ADAR3 | 2 | None | Arginine-rich ssRNA binding domain [1] | Inactive [1] [2] |

Catalytic Deaminase Domain

The deaminase domain contains the conserved active site that executes the hydrolytic deamination reaction [2] [8]. Key structural features include:

- Zinc ion coordination: Histidine (H394) and two cysteine residues (C451 and C516) coordinate a zinc ion that activates a water molecule for nucleophilic attack [2] [3].

- Catalytic residue: Glutamic acid (E396) forms hydrogen bonds with the activated water molecule [2].

- Inositol hexakisphosphate (IP6) binding: A buried IP6 molecule stabilizes multiple arginine and lysine residues and is required for catalytic activity [2].

- Base-flipping mechanism: Structural studies of ADAR2 reveal that the enzyme flips the target adenosine out of the RNA duplex into the active site pocket for deamination [7].

Double-Stranded RNA Binding Domains (dsRBDs)

The dsRBDs determine substrate specificity and binding affinity through recognition of dsRNA structure rather than specific sequences [1] [8]. Recent structural studies of ADAR2 reveal an asymmetric homodimer where dsRBDs engage with the RNA substrate in the 3'-direction of the target transcript [7]. Footprinting assays indicate that approximately 15 nucleotides 3'-adjacent and 26 nucleotides 5'-adjacent to the editing site are required for efficient binding, defining minimum antisense oligonucleotide lengths for therapeutic design [7].

Z-DNA Binding Domains

Unique to ADAR1, the Zα domain (and Zβ, which lacks binding capability) recognizes left-handed Z-DNA conformations in a sequence-independent manner [1] [2]. This domain was first identified in ADAR1 and restricts nucleic acids from adopting alternative conformations, potentially influencing gene expression [2]. The Zα domain is present only in the interferon-inducible p150 isoform of ADAR1, contributing to its distinct functional properties [1] [4].

Figure 1: Domain Architecture and Cellular Localization of Human ADAR Isoforms

ADAR Isoforms: Structure and Functional Consequences

ADAR1 Isoforms: p150 and p110

ADAR1 expresses two functionally distinct isoforms generated through alternative promoter usage:

- ADAR1 p150 (150 kDa): Interferon-inducible isoform containing Zα and Zβ domains, three dsRBDs, and a nuclear export signal that enables shuttling between nucleus and cytoplasm [4] [2] [3].

- ADAR1 p110 (110 kDa): Constitutively expressed isoform lacking the Z-DNA binding domains, localizing exclusively to the nucleus [4] [2].

Genetic studies demonstrate that these isoforms serve genetically separable functions: p150 uniquely regulates the MDA5-MAVS innate immune pathway, while both isoforms contribute to development [4].

ADAR2 and Its Splicing Variants

ADAR2 contains two dsRBDs and a catalytic deaminase domain, with predominant expression in the nervous system [1] [9]. A minor splicing variant incorporates an arginine-rich domain similar to ADAR3, potentially modifying RNA binding properties [1]. ADAR2 is essential for editing key neuronal targets including the GluA2 subunit of AMPA receptors [9].

ADAR3: The Catalytically Inactive Member

ADAR3 is exclusively expressed in the brain and lacks catalytic activity [1] [2]. It contains two dsRBDs and a unique arginine-rich domain that binds single-stranded RNA [1]. ADAR3 may function as a competitive inhibitor of editing by sequestering RNA substrates from ADAR1 and ADAR2 without editing them [1].

Quantitative Analysis of Editing Specificity

Understanding ADAR substrate preferences is essential for predicting editing sites and designing therapeutic editors. Quantitative studies using Sanger sequencing and peak height analysis have refined neighbor preferences:

Table 3: Quantitative Analysis of ADAR Editing Preferences [8]

| Parameter | ADAR1 | ADAR2 | ADAR1 Catalytic Domain Only | ADAR2 Catalytic Domain Only |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Most Influential Neighbor | 5' nearest neighbor | 5' nearest neighbor | 5' nearest neighbor | 5' nearest neighbor |

| Preferred 5' Neighbors | U = A > C > G | U ≈ A > C = G | U = A > C > G | U ≈ A > C = G |

| 3' Neighbor Preference | Minimal | U = G > C = A | Minimal | Reduced preference for 3' G |

| Key Finding | Preferences dictated by catalytic domain | dsRBMs contribute to 3' G preference | Confirms catalytic domain dominance | Loss of 3' G preference without dsRBMs |

The development of predictive algorithms based on these preferences enables researchers to identify potential editing sites in dsRNA of any sequence, with web-based applications available for accessibility [8].

Experimental Methods and Research Tools

Quantifying Editing Efficiency

Advanced sequencing methodologies enable accurate quantification of editing efficiency:

Chromatogram Peak Height Analysis Protocol [8]:

- Principle: Current four-dye sequencing chemistry produces uniform peak heights, enabling quantitative analysis of editing percentages from chromatograms.

- Method: Mix PCR products representing unedited or edited sequences at known ratios. Sequence mixtures and measure T and C peak heights in strands opposing the edited strand (A/G mixed peaks show inconsistent heights).

- Quantification: Calculate percentage editing by comparing peak heights at each site. Measurements are most accurate between 10-50% editing range.

- Validation: This method demonstrates superior accuracy (approximately 8% average deviation at 60% true editing) compared to nuclease mapping (12% standard deviation) or primer extension (up to 25% inaccuracy).

Deep Sequencing Approaches:

- Application: Genome-wide identification of editing sites across multiple organisms [2].

- Findings: Revealed thousands of editing sites, predominantly in non-coding regions including Alu elements and LINEs [5] [2] [3].

Structural Studies

Crystallography: The crystal structure of the human ADAR2 deaminase domain revealed the catalytic mechanism, including zinc coordination and IP6 stabilization [2] [3].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR): Solution structures of rat ADAR2 dsRBMs in presence and absence of dsRNA provided insights into RNA recognition mechanisms [8].

Site-Directed RNA Editing (SDRE) Technologies

Recent advances leverage ADAR structural knowledge for therapeutic applications:

RESTORE 2.0 Oligonucleotides [7]:

- Design: 30-60 nucleotide single-stranded oligonucleotides with stereo-random phosphate/phosphorothioate backbones and commercially available modifications (2'-O-methyl, 2'-fluoro, DNA).

- Mechanism: Asymmetric designs with orphan cytidine shifted toward the 3'-end, matching the asymmetric footprint of ADAR binding.

- Applications: Correction of pathogenic point mutations in cell lines, primary hepatocytes, and in vivo mouse models via lipid nanoparticle delivery.

Endogenous ADAR Recruitment:

- Advantage: Utilizes naturally occurring ADAR enzymes, avoiding overexpression-associated off-target effects [7].

- Design Principle: Minimum antisense oligonucleotide length of approximately 42 nucleotides (15 nt 3'-adjacent and 26 nt 5'-adjacent to target site) based on ADAR2 dimer footprinting [7].

Figure 2: Workflow for Quantitative Analysis of ADAR Editing Efficiency

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for ADAR Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Characteristics | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant ADAR Proteins | In vitro editing assays; Structural studies | Full-length vs. catalytic domain truncations; Species-specific variants | Catalytic domain alone determines neighbor preferences; dsRBMs affect efficiency [8] |

| Model Organisms | In vivo functional studies | Mice (Adar knockout); D. melanogaster; C. elegans | Adar-/- mice embryonic lethal; rescued by Mavs or Ifih1 deletion [4] [5] |

| SDREC Oligonucleotides | Therapeutic RNA editing; Endogenous ADAR recruitment | 30-60 nt; 2'-OMe, 2'-F modifications; Stereo-random PO/PS backbone | Asymmetric designs with 5'-24-1-10 configuration show high efficiency [7] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Generation of ADAR knockout cell lines; Endogenous tagging | Enable study of ADAR function in isogenic backgrounds | ADAR-null HEK293T cells show enhanced MDA5 response [4] |

| Interferon-Inducible Systems | Study of ADAR1 p150 function | IFN-α treatment induces p150 expression | p150 uniquely regulates MDA5-MAVS pathway [4] |

| Deep Sequencing Platforms | Genome-wide editing site identification | RNA-seq; Targeted sequencing | Reveals tissue-specific and developmentally regulated editing [5] [2] |

The intricate relationship between ADAR enzyme structure and function underscores the importance of understanding domain architecture, catalytic mechanisms, and substrate recognition principles. The modular organization of ADARs—with combinations of catalytic domains, dsRBDs, and specialized domains like Z-DNA binders—enables diverse biological functions from neural development to immune regulation. Quantitative analyses of editing preferences and advanced structural studies continue to refine our understanding of substrate recognition and catalytic mechanisms. These fundamental insights directly inform emerging therapeutic applications, particularly site-directed RNA editing technologies that leverage endogenous ADAR enzymes for precise genetic correction. Future research elucidating the structural basis of ADAR dimerization, substrate specificity, and isoform-specific functions will further advance both basic science and clinical applications in the field of RNA editing.

Adenosine to inosine (A-to-I) RNA editing is a critical post-transcriptional modification process catalyzed by a family of enzymes known as adenosine deaminases acting on RNA (ADARs). This mechanism converts adenosine to inosine within double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) substrates, a process with far-reaching implications for transcriptome diversity, neural function, and immune response [10] [11]. Initially discovered as an enzymatic activity causing unwinding of double-stranded RNA in Xenopus laevis oocytes and embryos, A-to-I editing was later identified as being mediated by ADAR enzymes [10]. The translation machinery recognizes inosine as guanosine, meaning A-to-I editing can effectively recode genetic information, leading to the expression of protein isoforms not directly encoded in the genome [10] [11].

The biological significance of A-to-I RNA editing is substantial, particularly in the nervous system where it diversifies the information encoded in the genome and fine-tunes numerous biological pathways [11]. Editing can alter codons in mRNAs, create splice sites, affect RNA structure, and influence RNA stability and gene expression [11] [12]. While early research focused on limited editing sites discovered serendipitously in protein-coding regions, recent advancements in deep sequencing and bioinformatics have revealed that the most frequent targets of A-to-I editing are double-stranded RNAs formed from inverted Alu repetitive elements located within introns and untranslated regions [10].

The ADAR Enzyme Family

Structural Characteristics and Domain Organization

ADAR enzymes are conserved throughout the animal kingdom but absent in protozoa, yeast, and plants [10]. Vertebrates possess three ADAR genes: ADAR1, ADAR2, and ADAR3 [10] [12]. These enzymes share common functional domains while exhibiting unique structural features that contribute to their specialized functions.

Domain Architecture: All ADAR family members contain a variable number of double-stranded RNA binding domains (dsRBDs) followed by a highly conserved C-terminal catalytic deaminase domain [10] [12]. The dsRBDs, typically comprising approximately 65 amino acids with an α-β-β-β-α configuration, facilitate direct contact with dsRNA substrates without strict sequence specificity [10]. The C-terminal deaminase domain forms the catalytic center where the adenosine deamination reaction occurs.

Isoform Diversity: ADAR1 exhibits unique characteristics among the family members. It contains two Z-DNA binding domains (Zα and Zβ) and is expressed as two primary isoforms: a constitutively expressed p110 isoform and an interferon-inducible p150 isoform [12]. The p150 isoform, which contains an extended N-terminal region with a nuclear export signal, can shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm, while the p110 isoform is predominantly nuclear [12]. ADAR2, which is most highly expressed in the brain but present in other tissues, contains two dsRBDs and a deaminase domain [10]. ADAR3 is restricted to the brain and contains an Arg-rich single-stranded RNA-binding domain (R domain) at its amino-terminal region, though it lacks demonstrated deaminase activity and may function as a regulatory protein [10] [12].

Table 1: ADAR Family Members and Their Characteristics

| ADAR Type | Expression Pattern | Key Structural Features | Catalytic Activity | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADAR1 | Ubiquitous | Two Z-DNA binding domains (Zα, Zβ), multiple dsRBDs | Active | Global editing of repetitive elements; immune regulation |

| ADAR2 | Brain-enriched | Two dsRBDs | Active | Site-specific editing of coding transcripts; neuroregulation |

| ADAR3 | Brain-restricted | R domain (ssRNA-binding) | Inactive | Potential negative regulator of editing |

Substrate Recognition and Editing Specificity

ADAR enzymes act on both inter- and intramolecular double-stranded RNAs exceeding 20 base pairs in length [10]. The enzymes demonstrate remarkable selectivity in their editing activity, influenced by RNA secondary structure rather than strict sequence requirements. While completely base-paired long dsRNAs (>100 bp) can have more than half of their adenosines edited, short or partially base-paired dsRNAs typically exhibit selective editing of only a few specific adenosines [10].

The editing site selectivity is dictated by the secondary structure of RNA substrates. A well-characterized example is the editing of the glutamate receptor GRIA2 precursor mRNA at the Q/R site, which requires an intramolecular dsRNA structure formed between exonic sequences surrounding the editing site and a downstream intronic complementary sequence termed the ECS (editing site complementary sequence) [10]. This structural requirement ensures editing occurs co-transcriptionally in the nucleus, either before or during splicing.

Although ADARs lack strict sequence specificity, they exhibit preference for certain sequence contexts. Studies have identified a preference for editing adenosines with 5' uridine and 3' guanosine neighbors [10]. Additionally, editing efficiency is influenced by base-pairing status at the editing site, with A-C mismatches being edited most efficiently among adenosine mismatches, while A-A or A-G mismatches are edited least efficiently [12].

Molecular Mechanism of Deamination

The Catalytic Center and Cofactors

The core catalytic mechanism of adenosine deamination involves hydrolytic deamination at the C6 position of adenosine [10] [11]. X-ray crystallographic studies of the human ADAR2 catalytic domain have revealed critical insights into the molecular architecture facilitating this transformation.

The catalytic center coordinates a zinc ion essential for the deamination reaction through residues His394, Glu396, Cys451, and C516 [10]. This zinc ion acts as a Lewis acid, polarizing the water molecule involved in the hydrolytic attack on the C6 position of adenosine. Structural studies have also identified the presence of inositol hexakisphosphate (InsP6) buried within the enzyme core, surrounded by numerous arginine and lysine residues and positioned adjacent to the catalytic center [10]. While the precise function of InsP6 remains under investigation, it is predicted to play a crucial role in the deamination reaction, potentially through structural stabilization or participation in transition state stabilization.

Table 2: Key Components of the ADAR Catalytic Center

| Component | Role in Deamination Mechanism | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Zinc Ion | Serves as Lewis acid; activates water molecule for hydrolytic attack | X-ray crystallography showing tetrahedral coordination [10] |

| Histidine 394 | Zinc coordination; transition state stabilization | Site-directed mutagenesis; structural analysis [10] |

| Glutamate 396 | Zinc coordination; proton shuttle | Structural and biochemical studies [10] |

| Cysteine 451/516 | Zinc coordination; structural integrity | Conservation across deaminase family; mutagenesis [10] |

| Inositol Hexakisphosphate (InsP6) | Proposed role in catalytic efficiency or structural stability | Co-crystallization; buried basic residues [10] |

Base Flipping Mechanism

The adenosine deamination reaction proceeds through a base flipping mechanism, where the target adenosine is rotated approximately 180° out of the double helix and positioned into the enzyme's catalytic pocket [10]. This extraordinary conformational change exposes the C6 atom of adenosine to nucleophilic attack by a water molecule activated by the zinc ion.

The base flipping process requires transient disruption of the dsRNA helix, with ADARs likely utilizing structural features within their dsRNA binding domains to facilitate nucleotide extrusion. While the precise mechanism of base recognition and flipping remains an active area of investigation, it represents a remarkable example of enzyme-induced nucleic acid structural rearrangement that enables exquisite substrate specificity without strict sequence requirements.

The deamination reaction proceeds through a tetrahedral intermediate, followed by elimination of ammonia to yield inosine. The resulting inosine maintains base-pairing capacity similar to guanosine, preferentially pairing with cytidine during translation [10]. This property underlies the functional consequences of A-to-I editing in coding regions, where it can alter the amino acid sequence of expressed proteins.

Diagram 1: Molecular Mechanism of Adenosine Deamination by ADAR Enzymes. This workflow illustrates the three key stages of A-to-I editing: (1) dsRNA substrate recognition and complex formation, (2) base flipping mechanism that positions the target adenosine into the catalytic pocket, and (3) hydrolytic deamination catalyzed by the zinc-containing active site.

Experimental Methodologies for Studying Adenosine Deamination

In Vitro Editing Assays

The investigation of adenosine deamination mechanisms relies on specialized experimental approaches designed to capture this dynamic process. Basic deamination assays utilize synthetic dsRNA substrates incubated with recombinant ADAR proteins or cellular extracts, followed by RNA extraction and analysis to detect editing events [11]. These assays typically employ completely base-paired dsRNAs to assess general deaminase activity, with detection methods ranging from traditional sequencing to more sophisticated mass spectrometry-based approaches.

Structural biology techniques have been instrumental in elucidating the base flipping mechanism and catalytic center architecture. X-ray crystallography of the human ADAR2 catalytic domain bound to RNA substrates has provided atomic-level resolution of the active site, revealing the coordination geometry of the catalytic zinc ion and the positioning of key residues [10]. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy offers complementary insights into the dynamics of base flipping and enzyme-RNA interactions in solution.

Kinetic analysis employs stopped-flow techniques and isotope tracing to determine the rates of individual steps in the deamination mechanism, including substrate binding, base flipping, chemical catalysis, and product release. These studies have revealed that base flipping is likely the rate-limiting step in the catalytic cycle, highlighting its critical role in regulating editing efficiency.

Detection and Quantification Methods

Advancements in detection methodologies have dramatically accelerated the study of A-to-I editing. Next-generation sequencing approaches, particularly RNA-seq, enable genome-wide identification of editing sites through comparison of cDNA sequences with genomic DNA [10]. Specialized computational pipelines have been developed to handle the unique challenges of A-to-I editing detection, including the distinction from single nucleotide polymorphisms and other RNA modifications.

Site-specific editing analysis employs techniques such as restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis, where editing creates or destroys restriction enzyme recognition sites, or Sanger sequencing with carefully designed primers. For quantitative assessment of editing efficiency at specific sites, mass spectrometry provides precise measurement of base composition, while high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) can separate and quantify nucleosides from hydrolyzed RNA samples.

Table 3: Experimental Methods for Studying A-to-I RNA Editing

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Key Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Activity Assays | Recombinant protein assays; Cell extract studies; Isotope tracing | Deaminase kinetics; Cofactor requirements; Inhibitor screening | Requires dsRNA substrates; Zinc dependence; pH sensitivity |

| Structural Biology | X-ray crystallography; Cryo-EM; NMR spectroscopy | Active site architecture; Base flipping visualization; Domain organization | Challenging for full-length proteins; May require truncated constructs |

| Editing Detection | RNA-seq; RFLP analysis; Sanger sequencing; HPLC/MS | Genome-wide discovery; Site-specific validation; Quantitative assessment | Bioinformatics challenges; Distinguishing editing from SNPs |

| Functional Analysis | Knockout models; Knockdown approaches; Reporter assays | Biological consequences; Substrate specificity; Regulatory mechanisms | Compensation between ADARs; Tissue-specific effects |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Adenosine Deamination

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Systems | E. coli; Sf9 insect cells; HEK293T cells | Recombinant ADAR production; Requires optimization for full-length proteins |

| Activity Assay Components | Synthetic dsRNAs; Radiolabeled ATP; Zinc chloride; InsP6 | In vitro activity measurements; Cofactor dependence studies |

| Detection Tools | Sequence-specific primers; Anti-inosine antibodies; Restriction enzymes | Editing quantification; Site-specific validation; Histological detection |

| Cell Culture Models | ADAR knockout cell lines; Neuronal cultures; Primary astrocytes | Physiological editing studies; Cell-type specific functions |

| Animal Models | ADAR1 null (embryonic lethal); ADAR2 knockout (seizure phenotype) | Whole-organism physiology; Developmental functions; Disease modeling |

Biological Implications and Research Applications

The molecular mechanism of adenosine deamination has profound biological consequences across multiple physiological systems. In the nervous system, site-specific editing of neurotransmitter receptors, including ionotropic glutamate receptors (GRIA2, GRIK1-2) and the serotonin receptor 5-HT2C, fine-tunes neuronal excitability, synaptic transmission, and neuropharmacological responses [10]. Recoding editing events can alter ion permeability, gating properties, and G-protein coupling efficiency of these critical signaling molecules.

In innate immunity, ADAR1-mediated editing of endogenous dsRNAs prevents their recognition by cytoplasmic dsRNA sensors such as MDA5, thereby suppressing inappropriate interferon activation and autoimmune responses [10] [12]. This editing function particularly targets Alu repetitive elements that form extensive dsRNA structures, marking them as "self" to avoid triggering antiviral defense pathways. The interferon-inducible expression of ADAR1 p150 further connects RNA editing to antiviral responses, with complex relationships between editing and viral replication depending on virus type and infection context.

The base flipping and hydrolytic deamination mechanism also presents opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Research is exploring engineered ADAR proteins for RNA repair strategies to correct disease-causing mutations at the transcript level [12]. Additionally, small molecule modulators of ADAR activity are being investigated for conditions where editing is dysregulated, including certain cancers, autoimmune disorders, and neurological diseases. Understanding the precise molecular mechanism of adenosine deamination provides the foundation for developing these novel therapeutic approaches.

Adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) RNA editing is a fundamental post-transcriptional modification catalyzed by adenosine deaminases acting on RNA (ADARs) in metazoans [13]. This process critically depends on the presence of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) substrates and exhibits distinct sequence preferences at the editing site and its immediate neighborhood. Understanding these structural and sequential parameters is essential for elucidating the mechanism and biological significance of A-to-I editing, which plays crucial roles in neural function, immune regulation, and cancer pathogenesis [14] [15]. This technical guide comprehensively details the dsRNA requirements and nucleotide bias governing A-to-I editing efficiency, providing researchers with the foundational knowledge necessary for experimental design and therapeutic development.

Structural Basis of ADAR-dsRNA Interaction

ADAR Domain Architecture and RNA Recognition

ADAR enzymes possess a conserved domain structure that facilitates interaction with dsRNA substrates. All functional ADARs (ADAR1 and ADAR2) contain multiple double-stranded RNA binding domains (dsRBDs) at their N-terminus and a catalytic deaminase domain at their C-terminus [13] [14]. The number and arrangement of these domains differ between family members:

- ADAR1 incorporates three dsRBDs and exists as two primary isoforms: a constitutively expressed nuclear p110 isoform and an interferon-inducible p150 isoform that shuttles between nucleus and cytoplasm [13] [15].

- ADAR2 contains two dsRBDs and is predominantly nuclear, with particularly high expression and editing activity in neural tissues [13] [14].

- ADAR3 possesses two dsRBDs and a unique single-stranded RNA-binding R-domain but demonstrates no catalytic activity, instead functioning as a competitive inhibitor of editing in specific neurological contexts [13].

The dsRBDs recognize the A-form helix of dsRNA through extensive contacts with the phosphate and ribose backbone rather than specific nucleotide sequences, explaining the structural preference for dsRNA over particular primary sequences [13]. This interaction spans approximately 16 base pairs of dsRNA, with the N-terminal α-helix packing into one minor groove, the loop between β-sheets interacting with the major groove, and the C-terminal α-helix packing into the subsequent minor groove [13].

Table 1: ADAR Family Protein Domain Architecture

| ADAR Family Member | Number of dsRBDs | Catalytic Activity | Unique Domains/Features | Primary Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADAR1 p110 | 3 | Active | Single Z-DNA binding domain | Nucleus |

| ADAR1 p150 | 3 | Active | Two Z-DNA binding domains, NES | Nucleus/Cytoplasm |

| ADAR2 | 2 | Active | - | Nucleus |

| ADAR3 | 2 | Inactive | R-domain (ssRNA binding) | Brain-specific |

dsRNA Structure and Length Requirements

ADAR enzymes require double-stranded RNA structures for catalytic activity, with editing efficiency strongly correlating with dsRNA length and stability [13] [16] [14]. Key structural requirements include:

- Minimum Length: Effective editing requires dsRNA segments longer than 20 base pairs, with optimal activity observed on structures exceeding 100 bp [15].

- Duplex Characteristics: ADARs target RNA duplexes in the A-form conformation, which presents a specific geometry accessible to the catalytic deaminase domain [13].

- Structural Imperfections: While perfectly base-paired long dsRNAs (>100 bp) can be edited, selectively modified adenosines typically occur in shorter, partially paired dsRNAs with structural imperfections such as bulges, loops, and mismatches [15] [14].

The abundance of endogenous dsRNA structures, particularly those formed by inverted repetitive elements like Alu sequences in primates, explains the widespread editing observed in transcriptomes [16]. In fact, the degree of hyper-editing across metazoan species correlates strongly with genomic repeat content and dsRNA formation potential [16].

Beyond the requirement for dsRNA structure, ADAR enzymes exhibit distinct sequence preferences surrounding editing sites that significantly influence editing efficiency.

Neighborhood Nucleotide Bias

Extensive analysis of editing sites has revealed a consistent nucleotide bias immediately adjacent to edited adenosines. The most efficient editing occurs when the edited adenosine is preceded by a pyrimidine (preferentially uracil or cytosine) and followed by a guanosine, creating a 5'-UAG-3' or similar context [14]. This neighborhood bias reflects structural constraints within the ADAR catalytic pocket that favor certain nucleotide arrangements.

Table 2: Neighborhood Nucleotide Influence on A-to-I Editing Efficiency

| Position Relative to Edited A | Preferred Nucleotide | Effect on Editing Efficiency | Structural/Rational Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| -1 (5' neighbor) | Uracil > Cytosine | Strong enhancement | Optimal base stacking and catalytic pocket accommodation |

| +1 (3' neighbor) | Guanosine | Strong enhancement | Stabilizes transition state through unknown mechanism |

| Editing site pairing | A-C mismatch | Highest efficiency | Creates structural distortion facilitating base flipping |

| Editing site pairing | A-U pairing | Moderate efficiency | Standard pairing with moderate editing rates |

| Editing site pairing | A-G or A-A mismatch | Lowest efficiency | Suboptimal geometry for deamination reaction |

Base Pairing Status at Editing Site

The base pairing status of the target adenosine significantly influences editing efficiency. Unlike many nucleic acid-modifying enzymes that require perfectly paired substrates, ADARs actually display enhanced activity at mismatched sites:

- A-C mismatches represent the most favorable configuration for efficient deamination [14].

- Standard A-U pairs can be edited but typically with reduced efficiency compared to mismatched positions.

- A-G or A-A mismatches represent the least favorable configurations with minimal editing activity [14].

This preference for structural imperfections suggests a nucleotide flipping mechanism where the target adenosine is extrahelically positioned into the catalytic pocket [13]. Mismatched bases require less energy for this flipping process, thereby enhancing editing rates.

RNA Editing Detection and Quantification

Accurate profiling of RNA editing sites requires specialized computational approaches to distinguish true editing events from sequencing errors, mapping artifacts, and single nucleotide polymorphisms:

- Hyper-edited Read Detection: Standard alignment tools often fail to map reads with extensive editing clusters. Specialized algorithms identify these unmapped reads and realign them after pre-masking potential editing sites, enabling discovery of densely edited regions [16] [17].

- Variant Calling Pipelines: Tools like REDItools and JACUSA systematically identify editing sites from RNA-seq data while applying filters to remove technical artifacts [17].

- Quantification Metrics: Editing levels are typically quantified as the percentage of edited reads at a specific genomic position. The Alu Editing Index (AEI) provides a global measure of editing activity by aggregating signals from numerous Alu elements [17].

Biochemical and Genetic Approaches

- In vitro Editing Assays: Synthetic dsRNA substrates with systematically varied sequences and structures allow precise determination of sequence preferences and kinetic parameters [14].

- Genetic Mapping: Natural genetic variation in Diversity Outbred mouse populations has been exploited to identify sequence polymorphisms that influence editing ratios, revealing that most variable A-to-I editing sites are determined by local nucleotide polymorphisms in proximity to the editing site [18].

- RBP Binding Studies: Enhanced CLIP (eCLIP) sequencing has quantified how RNA editing events influence binding of approximately 150 RNA-binding proteins, demonstrating that editing can either enhance or disrupt protein-RNA interactions depending on context [19].

Diagram 1: Sequence and Structural Determinants of A-to-I Editing Efficiency

Functional Consequences and Research Applications

The sequence and structural preferences of ADAR enzymes have profound biological implications:

- Transcriptome Diversification: The preference for specific sequence contexts and dsRNA structures determines which adenosines are edited, leading to tissue-specific and developmentally regulated recoding events [14] [15].

- Immune Regulation: ADAR1 editing of endogenous dsRNA structures prevents recognition by cytoplasmic dsRNA sensors (e.g., MDA5), thereby suppressing innate immune activation and autoimmune responses [16] [15].

- Cancer Pathogenesis: Dysregulated editing contributes to tumor progression through multiple mechanisms, including recoding of oncogenes like AZIN1 and COPA, with the specific editing events governed by these sequence and structural parameters [20] [15].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying A-to-I RNA Editing

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| ADAR Expression Constructs | pcDNA3.1-ADAR1/2, Lentiviral ADAR shRNA | Gain/loss-of-function studies to determine ADAR-specific editing effects |

| Editing Reporter Systems | Synthetic dsRNA substrates with preferred editing contexts | In vitro determination of editing kinetics and sequence preferences |

| Detection & Quantification Tools | REDItools, JACUSA, Hyper-editing detection algorithms | Computational identification and quantification of editing sites from RNA-seq data |

| Cell Line Models | A549, H1299 (NSCLC), HepG2, K562 | Context-specific editing studies in relevant cellular backgrounds |

| Validated Antibodies | Anti-ADAR1, Anti-ADAR2, Anti-inosine | Protein expression analysis and selective detection of edited RNAs |

| Chemical Inhibitors | 8-azaadenosine derivatives | Pharmacological manipulation of editing activity for functional studies |

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Characterizing Editing Preferences

The sequence and structural preferences governing A-to-I RNA editing—specifically the requirement for dsRNA substrates and the distinct neighborhood nucleotide bias—represent fundamental determinants of editing efficiency and specificity. These parameters directly influence ADAR binding, catalytic efficiency, and ultimately, the functional outcomes of editing events in both physiological and pathological contexts. Continuing research into these preferences using the experimental approaches detailed herein will further elucidate the complex regulatory networks controlled by RNA editing and potentially unlock novel therapeutic strategies for cancer, autoimmune disorders, and neurological diseases.

Adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) RNA editing, catalyzed by the ADAR enzyme family, represents a crucial post-transcriptional mechanism that dynamically expands the transcriptome and proteome. This whitepaper delineates the core biological functions of A-to-I editing, focusing on its dual roles in innate immune regulation and transcript diversification. We examine how ADAR-mediated deamination maintains cellular homeostasis by distinguishing self from non-self RNA, thereby preventing aberrant autoimmune activation, while simultaneously generating molecular diversity through recoding and splicing modulation. The content is framed within contemporary research paradigms that position A-to-I editing as a critical interface between genetic programming and environmental adaptation, with significant implications for therapeutic development across autoimmune disorders, neurological conditions, and cancer.

A-to-I RNA editing is catalyzed by adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR) enzymes, which hydrolytically deaminate adenosine to inosine in double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) substrates. Inosine is interpreted as guanosine by cellular machinery during translation and RNA processing, effectively enabling recoding of genetic information at the transcript level [21]. The human ADAR family comprises three members: ADAR1 (encoded by ADAR), ADAR2 (encoded by ADARB1), and ADAR3 (encoded by ADARB2). ADAR1 exists as two major isoforms: a constitutively expressed p110 protein (nuclear) and an interferon-inducible p150 protein that shuttles between nucleus and cytoplasm. ADAR2 is predominantly expressed in the brain, while ADAR3 lacks catalytic activity and may function as a competitive inhibitor [21] [15].

Structurally, ADAR enzymes contain multiple functional domains: (1) two or three double-stranded RNA binding domains (dsRBDs) that recognize nonspecific double-stranded regions longer than 15 bp; (2) a C-terminal catalytic deaminase domain; and (3) in the case of ADAR1 p150, a Zα domain that binds left-handed Z-DNA and Z-RNA with high affinity. All ADAR1 isoforms also include a Zβ domain, which recent evidence suggests binds G-quadruplex structures [22]. These structural features enable ADARs to recognize diverse RNA substrates and nucleic acid conformations, connecting genetic programming by flipons (sequences adopting alternative conformations) with information encoding by codons [22].

Innate Immune Regulation via dsRNA Sensing Pathways

Mechanism of Self/Non-Self Discrimination

The primary innate immune function of ADAR1 involves marking endogenous dsRNA as "self" to prevent inappropriate activation of cytosolic dsRNA sensors. In the absence of ADAR editing, endogenous dsRNA is recognized by pattern recognition receptors including melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5, encoded by IFIH1) and protein kinase R (PKR, encoded by EIF2AK2) [21]. MDA5 binding to unedited dsRNA triggers recruitment of mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS), initiating type I interferon (IFN) responses. Similarly, PKR activation phosphorylates eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α), inhibiting protein synthesis and inducing integrated stress response pathways [21].

ADAR1 suppresses these responses through two complementary mechanisms: (1) editing-dependent substrate modification where A-to-I conversions disrupt dsRNA secondary structures, rendering them unrecognizable by MDA5 and PKR; and (2) editing-independent competitive binding where ADAR1 directly interacts with dsRNA substrates and signaling components [21]. The dsRBD3 domain of ADAR1 specifically inhibits PKR activation through competitive binding and direct protein interaction [21]. The critical importance of this immunoregulatory function is evidenced by the embryonic lethality of Adar knockout mice, which die from widespread apoptosis and hematopoiesis defects due to interferonopathy, a phenotype rescued by concurrent deletion of Mda5 or Mavs [23] [22].

Pathophysiological Consequences and Therapeutic Targeting

Dysregulated ADAR1 activity underlies multiple human pathologies. Loss-of-function mutations in ADAR cause Aicardi-Goutières syndrome type 6 (AGS6), a severe autoimmune and neurological disorder characterized by persistent type I interferon response [21]. Recent research has identified the specific human ADAR p.N173S mutation as a loss-of-function variant that correlates with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) incidence [23]. Intestinal epithelial-specific Adar knockout in mice (AdariΔgut) triggers spontaneous ileitis and colitis, with transcriptome profiling showing upregulation of inflammatory response, TNFα, IL-6, and IFNα/β/γ pathways [23].

Mechanistic studies reveal that ADAR deficiency leads to accumulation of endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) and unedited dsRNAs, which activate MDA5-mediated sensing and subsequent Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signaling [23]. This ADAR-dsRNA/ERVs-MDA5-JAK/STAT axis represents a promising therapeutic target, with demonstrated efficacy of JAK1/2 inhibitor Ruxolitinib in attenuating IBD in preclinical models [23].

Table 1: Experimental Models of ADAR1-Related Immune Dysregulation

| Model System | Genetic Manipulation | Phenotype | Key Molecular Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse intestinal organoids | Intestinal epithelial-specific Adar knockout | Disrupted intestinal homeostasis, impaired growth | dsRNA/ERV accumulation; MDA5 activation; JAK-STAT signaling [23] |

| AdariΔgut mice | Tamoxifen-inducible gut epithelial-specific Adar knockout | Spontaneous ileitis and colitis, lethality within 6 days | Increased IFNγ, epithelial damage, decreased E-cadherin and Muc2 [23] |

| Human IBD patients | Reduced ADAR expression in intestinal crypts | Chronic bowel inflammation | Tissue-specific decrease in epithelial ADAR; increased non-epithelial ADAR [23] |

| ADAR p195A/p150- mice | Zα domain mutation | Lethal interferonopathy | PKR-dependent disease phenotype [21] |

Innate Immune Signaling Pathway Visualization

Diagram 1: ADAR1 Regulation of Innate Immune Signaling. ADAR1 editing prevents unedited endogenous dsRNA from activating MDA5 and PKR pathways, thereby suppressing interferon responses and integrated stress response to maintain cellular homeostasis.

Transcriptome Diversification Through Recoding and Editing

Recoding Editing in Protein-Coding Regions

A-to-I editing in coding sequences can result in non-synonymous amino acid substitutions, effectively expanding the proteomic repertoire beyond genomic constraints. While most editing occurs in non-coding regions, several well-characterized recoding events have significant functional consequences. The quantitative landscape of recoding editing reveals tissue-specific patterns and conservation across species [22].

Recent studies identify approximately 2,261 human genes with nonsynonymous RNA editing (NSE) events, with frequent lysine to arginine substitutions that may prevent ubiquitination and alter protein turnover [22]. However, the prevalence and functional impact of NSE remains controversial, with estimates varying considerably across studies due to methodological differences and tissue-specific variability [22].

Table 2: Functionally Characterized Recoding Editing Events

| Gene | Editing Site | Amino Acid Change | Functional Consequence | Disease Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AZIN1 | Ser367Gly | Serine → Glycine | Increased affinity for antizyme; stabilizes oncoproteins ODC and cyclin D1 | Hepatocellular carcinoma, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, NSCLC, colorectal cancer [20] [15] |

| CYP1A1 | Ile462Val | Isoleucine → Valine | Enhances PI3K/Akt signaling; increases HO-1 interaction and nuclear translocation | Non-small cell lung cancer progression [20] |

| COPA | Ile164Val | Isoleucine → Valine | Promotes ER stress and metastasis (CRC); inhibits PI3K/AKT via CAV1 in HCC | Metastatic colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma [15] |

| GRIA2 | Gln607Arg | Glutamine → Arginine | Alters calcium permeability of glutamate receptor | Neurological function [22] |

| CACNA1D (CaV1.3) | Multiple sites in IQ domain | Ile→Met, Gln→Arg, Tyr→Cys | Decreases current density; shifts voltage dependence; modulates neuronal Ca2+ signaling | Neuroprotection against calcium toxicity [24] |

Non-Coding Editing and RNA Stability Regulation

Beyond recoding, A-to-I editing in non-coding regions, particularly 3'UTRs, significantly influences gene expression through multiple mechanisms. Research across human populations has revealed that editing stabilizes RNA secondary structures and reduces accessibility of AGO2-miRNA complexes to target sites, thereby modulating mRNA abundance [25]. This structure-mediated mechanism represents a widespread regulatory pathway that may explain the functional significance of many non-coding editing events.

Population-scale transcriptome analyses demonstrate that editing sites in 3'UTRs are highly conserved across individuals despite variations in ADAR expression levels, suggesting robust functional constraints [25]. Genes involved in immune response pathways are particularly enriched for 3'UTR editing sites, highlighting the connection between RNA editing and immunoregulation [25].

Splicing Modulation Through Structural and Sequence Alterations

Direct and Indirect Splicing Regulation

ADAR-mediated editing influences alternative splicing through multiple mechanisms: (1) by creating or destroying splice sites through nucleotide substitutions; (2) by altering RNA secondary structures that affect splice site accessibility; and (3) through coordinated regulation with splicing factors [24]. Bioinformatics analyses indicate that approximately 5% of alternatively spliced human exons are Alu-derived, with over 80% of these splicing events causing frameshifts or premature termination codons [22].

Recent research has uncovered an unexpected synergy between RNA editing and alternative splicing in the nervous system. In CaV1.3 calcium channels, generation of the short splice variant (CaV1.343S) results in a threefold increase in RNA editing at the IQ domain compared to the long variant [24]. The edited short variant exhibits markedly decreased current density and a depolarizing shift in voltage activation, effectively converging the functional properties of short and long variants. This interplay represents a neuroprotective mechanism that prevents calcium overload in susceptible neurons [24].

Structural Constraints on Editing and Splicing

The presence of specific protein targeting signals can constrain both RNA editing and alternative splicing. Genome-wide analyses in Drosophila melanogaster and humans demonstrate that genes encoding signal peptides—short N-terminal sequences directing protein localization—show significant suppression of both alternative splicing events in N-terminal regions and RNA recoding editing in signal peptide domains [26]. This finding challenges the conventional paradigm that conserved genomic regions are compensated by extensive post-transcriptional diversification, instead revealing that functionally critical domains like signal peptides impose evolutionary constraints on transcriptome plasticity.

Splicing-Editing Interplay Visualization

Diagram 2: Synergy Between Alternative Splicing and RNA Editing in CaV1.3. The short splice variant (CaV1.3₄₃S) undergoes enhanced A-to-I editing, which modifies its biophysical properties to decrease calcium influx and provide neuroprotection.

Experimental Approaches and Research Tools

Key Methodologies for A-to-I Editing Analysis

Cutting-edge research in A-to-I editing employs multidisciplinary approaches to elucidate functional mechanisms:

- Editome profiling: RNA sequencing combined with specialized bioinformatics pipelines (e.g., REDItools, RADAR database) to identify editing sites and quantify editing levels [23] [26].

- Functional validation: Reconstitution experiments in ADAR-knockdown cells (e.g., shRNA-mediated knockdown in HCT116) with wild-type versus mutant ADAR expression vectors to assess editing activity on specific targets like GLI1 [23].

- Genetically engineered models: Tissue-specific and inducible knockout mice (e.g., Villin-CreERT2;Adarfl/fl for intestinal epithelium) to study physiological consequences of ADAR loss [23].

- Organoid systems: Intestinal organoids from Adar-deficient mice to investigate cell-autonomous effects on stem cell function and differentiation [23].

- Pathway analysis: Transcriptome sequencing with Hallmark pathway analysis and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) to identify dysregulated pathways in editing-deficient models [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for A-to-I Editing Research

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| ADAR knockout mice | In vivo modeling of editing deficiency | Intestinal epithelial-specific knockout reveals spontaneous inflammation [23] |

| shADAR knockdown cells | Cellular models of reduced editing | HCT116 cells with shRNA-mediated ADAR knockdown for reconstitution assays [23] |

| Ruxolitinib (JAK1/2 inhibitor) | Therapeutic targeting of editing-related pathways | Attenuates IBD in Adar-deficient mice [23] |

| Site-directed mutagenesis plasmids | Expression of edited protein variants | pcDNA3.1-CYP1A1-WT vs. edited for functional studies [20] |

| RNA sequencing + bioinformatics | Genome-wide editing site identification | Population-level analysis of editomes [25] |

| Organoid culture systems | 3D models of tissue-specific editing functions | Intestinal organoids to study epithelial-specific ADAR roles [23] |

A-to-I RNA editing represents a critical layer of post-transcriptional regulation that intersects with fundamental cellular processes from immune homeostasis to transcript diversification. The mechanistic insights detailed in this whitepaper highlight the dual functionality of ADAR enzymes in both preserving self-tolerance through suppression of dsRNA sensing pathways and expanding proteomic diversity through targeted recoding and splicing modulation.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the context-specific regulation of editing activity, particularly in response to environmental stimuli and cellular stress. The development of more precise programmable RNA editing technologies holds promise for therapeutic applications across autoimmune, neurological, and oncological indications. Furthermore, understanding how editing coordinates with other epigenetic mechanisms will provide a more integrated view of post-transcriptional regulatory networks in health and disease.

As research progresses, targeting the ADAR-dsRNA-immune axis represents a promising therapeutic strategy for inflammatory conditions, while manipulation of specific recoding events may offer novel approaches for cancer and neurological disorders. The continued investigation of A-to-I RNA editing will undoubtedly yield both fundamental biological insights and translational applications across medicine.

Adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) RNA editing, catalyzed by the ADAR enzyme family, represents a critical post-transcriptional mechanism that greatly expands transcriptomic diversity. The functional outcomes of this editing are profoundly influenced by the spatial organization of the editing machinery within the cell and its temporal expression across tissues. This technical guide examines the sophisticated regulatory mechanisms governing the nucleocytoplasmic distribution of ADAR enzymes and their edited targets, and explores the tissue-specific expression patterns that determine editing efficacy. Within the broader thesis of A-to-I RNA editing mechanisms and significance, understanding these spatial and temporal dimensions is paramount for elucidating how RNA editing contributes to normal cellular physiology and disease pathogenesis, particularly in cancer and neurological disorders. For researchers and drug development professionals, this knowledge provides the foundation for developing targeted therapeutic interventions that can modulate the RNA editing landscape in a cell-type and subcellular compartment-specific manner.

Core Mechanisms of Nucleocytoplasmic Shuttling

The subcellular localization of ADAR enzymes is a dynamically regulated process that determines access to substrate RNAs and functional outcomes of editing activity. The human ADAR1 enzyme exists in distinct isoforms with characteristic localization behaviors governed by specific molecular motifs.

ADAR Isoforms and Their Localization Signals

Table 1: ADAR Isoforms and Localization Determinants

| ADAR Isoform | Molecular Weight | Induction | Primary Localization | Key Localization Signals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADAR1 (long) | 150 kDa | Interferon-inducible | Nucleus and Cytoplasm | NLS (dsRBD3), NES (N-terminal) |

| ADAR1 (short) | 110 kDa | Constitutive | Predominantly Nuclear | NLS (dsRBD3) |

| ADAR2 | - | Constitutive | Nuclear | Nuclear Localization Signal |

| ADAR3 | - | Brain-specific | Nuclear | Lacks deaminase activity |

The 150-kDa ADAR1 isoform exhibits bidirectional shuttling capability mediated by a Crm1-dependent nuclear export signal (NES) in its amino-terminal region and an atypical nuclear localization signal (NLS) that overlaps almost entirely with its third double-stranded RNA-binding domain (dsRBD3) [27]. This configuration allows for regulated movement across the nuclear envelope in response to cellular signals. In contrast, the constitutively expressed 110-kDa ADAR1 isoform is predominantly nuclear but can display cytoplasmic localization under specific conditions such as transcriptional inhibition, indicating it also possesses shuttling capability [27].

Regulatory Mechanisms of Localization

The localization of ADAR1 is not merely determined by the presence of localization signals but is subject to sophisticated regulation through multiple mechanisms:

- RNA-binding dependent regulation: The first dsRBD of ADAR1 (dsRBD1) interferes with the NLS function of dsRBD3. Active RNA binding by either dsRBD1 or the NLS-bearing dsRBD3 is required for cytoplasmic accumulation, suggesting RNA-mediated cross-talk between dsRBDs that can mask the NLS [27].

- Transcription-dependent accumulation: Nuclear accumulation of endogenous ADAR1 is transcription-dependent, with the balance between nuclear import and export being controlled in an RNA-dependent manner [27].

- C-terminal regulatory region: A third region located in the C-terminus of ADAR1 also interferes with nuclear accumulation, adding another layer of regulatory control [27].

The dynamic shuttling of ADAR enzymes has profound implications for substrate access. While some editing events must occur co-transcriptionally in the nucleus before intron removal, the presence of ADAR1 in both compartments enables editing of a broader range of substrates, including those with cytoplasmic functions [27] [15].

Tissue and Developmental Stage-Specific Distribution

The expression of ADAR enzymes and the resulting A-to-I editing landscape exhibit marked variation across tissues and developmental stages, reflecting specialized functional requirements.

Tissue-Specific Expression Patterns

Table 2: ADAR Expression and Editing Across Tissues

| Tissue/Organ | ADAR Expression | Key Editing Events | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brain | High ADAR2, ADAR3 | Glutamate receptors, Serotonin receptor | Neuronal excitability, Neurotransmission |

| Lung | ADAR1 expression | CYP1A1_I462V, miR-411-5p | Lung cancer progression, TKI resistance |

| Liver | ADAR1, ADAR2 | AZIN1 (S367G), COPA | Hepatocellular carcinoma progression |

| Prostate | ADAR1 | AZIN1 (S367G) | Tumor aggressiveness, Nuclear translocation |

| Embryonic Tissues | High editing | Multiple targets | Normal development |

The brain represents a hotspot for RNA editing, with both ADAR2 and ADAR3 showing enriched expression. ADAR2 mediates critical editing events in neurotransmitter receptors, including glutamate-gated ion channels and the serotonin 2C receptor, fine-tuning neuronal excitability and synaptic signaling [28] [15]. ADAR3, while catalytically inactive, is almost exclusively expressed in the brain and may serve a regulatory role by competing with other ADARs for substrate binding [15].

In peripheral tissues, ADAR1 is the predominant enzyme and its upregulation is frequently associated with cancer progression. In lung cancer, increased ADAR1-mediated editing of CYP1A1 and miR-411-5p contributes to tumor aggressiveness and therapy resistance [20] [15]. Similarly, in prostate cancer, ADAR1-catalyzed editing of AZIN1 leads to nuclear translocation of the edited protein and worse clinical outcomes [29].

Developmentally Regulated Editing

A-to-I editing is dynamically regulated throughout development, with specific editing events occurring in a stage-specific manner. Research in C. elegans has demonstrated that nearly half of all editing events occur in a developmentally regulated fashion, with distinct patterns observed between embryonic and L4 larval stages [30]. In human brain development, editing levels undergo significant changes during the late-fetal to adult transition, potentially contributing to neural maturation and functional specialization [31].

This developmental regulation may be achieved through several mechanisms:

- Expression level changes: Modulation of ADAR expression during development

- Subcellular redistribution: Alterations in the nucleocytoplasmic partitioning of ADAR enzymes

- Co-factor availability: Developmentally regulated expression of co-factors that enhance or suppress editing at specific sites

- Substrate accessibility: Changes in RNA secondary structure or chromatin accessibility that affect editing efficiency

The functional significance of developmentally regulated editing is particularly evident in the nervous system, where precise editing of ion channels and receptors is crucial for proper neuronal function. Dysregulation of these editing events has been linked to neuropathological conditions [30] [15].

Experimental Methods for Studying Localization and Expression

Investigating the spatial and temporal dynamics of A-to-I RNA editing requires a multifaceted experimental approach combining molecular biology, imaging, and sequencing techniques.

Subcellular Localization Assays

Live-Cell Imaging with Fluorescent Protein Fusions: Researchers have developed pyruvate kinase (PK) fusion constructs to systematically dissect the localization signals within ADAR1 [27]. The experimental workflow involves:

- Cloning regions of ADAR1 upstream of pyruvate kinase cDNA in pcDNA3 derivatives

- Fusing the PK reporter protein to tandem myc-epitopes or GFP at its C-terminus

- Transfecting HeLa or mouse 3T3 cells grown on coverslips using Tfx-20 transfection reagent

- Fixing, permeabilizing, and staining cells using monoclonal antibody 9E10 for myc-tagged proteins

- Visualizing and imaging with fluorescence microscopy or confocal laser scanning microscopy

Nuclear Export Inhibition Studies: Treatment with leptomycin B (LMB), an inhibitor of Crm1-dependent nuclear export, demonstrates the shuttling capability of ADAR1. Increased nuclear accumulation of overexpressed ADAR1 after LMB treatment confirms active nuclear export [27].

Cell Fractionation with Editing Validation: Separation of nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions followed by RNA extraction and editing analysis determines the subcellular distribution of editing activity. The CYP1A1_I462V editing event has been validated using this approach [20].

Tissue-Specific Expression Analysis

Digital Droplet PCR (ddPCR): This highly sensitive method enables precise quantification of editing levels in clinical samples. The protocol for detecting AZIN1 editing includes [29]:

- Designing specific primers (Forward: GAGCCTCTGTTTACAAGCAG; Reverse: CATGGAAAGAATCTGCTCCC) and probes for wild-type (5'-/5HEX/GCTCAGGAAGAAGACAGCTTTCCAC/3IABkFQ/-3') and edited AZIN1 (5'-/56-FAM/GCTCAGGAAGAAGACAGCCTTCCA/3IABkFQ/-3')

- Preparing PCR mixture with ddPCR Super Mix

- Generating and analyzing droplets to quantify editing frequency

RNA Sequencing and Bioinformatics: High-throughput sequencing coupled with specialized computational pipelines identifies editing sites across tissues and developmental stages. Key methodological considerations include [30] [31]:

- Comparing RNA-seq data from multiple independent sources to distinguish true editing sites from SNPs

- Eliminating changes detected in ADAR mutant strains

- Applying restrictive alignment parameters for nonrepetitive regions (≤2 alignment sites)

- Implementing stage-specific analysis to identify developmentally regulated editing

- Utilizing resources like REDIportal and DARNED databases for cross-tissue editing comparisons

Immunohistochemistry and Confocal Microscopy: Spatial localization of edited proteins in clinical samples provides clinical correlation. For AZIN1, nuclear translocation of the edited form correlates with tumor aggressiveness in prostate cancer [29]. The protocol involves:

- Fixing cells with 4% formaldehyde

- Analyzing with LSM 880 META confocal laser scanning microscope

- Using 63x and 40x A-Plan oil immersion objectives

- Imaging in multitrack mode with ZEN software

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying A-to-I Editing Localization and Expression

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| PK-myc/PK-GFP Fusion Vectors | Dissection of localization signals | Identifying NLS/NES in ADAR1 domains [27] |

| ADAR Knockout Cell Lines | Control for editing-specific effects | HEK293T ADAR1 KO cells [29] |

| Leptomycin B (LMB) | Nuclear export inhibition | Demonstrating Crm1-dependent export of ADAR1 [27] |

| ddPCR Probes & Primers | Sensitive editing quantification | AZIN1 editing detection in clinical samples [29] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Genome editing for functional studies | Generating uneditable AZIN1 constructs [29] |

| RNA-seq Libraries | Genome-wide editing discovery | Identifying developmental stage-specific editing [30] |

| Confocal Microscopy | Subcellular protein localization | Visualizing nuclear translocation of edAZIN1 [29] |

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: ADAR1 Nucleocytoplasmic Shuttling Mechanism. The dynamic equilibrium between nuclear and cytoplasmic pools of ADAR1 is regulated by competing localization signals and cellular conditions. The NLS (dsRBD3) promotes nuclear import, while the NES mediates Crm1-dependent export. RNA binding status and transcription activity modulate this balance [27].

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Editing Localization Studies. Comprehensive approach integrating sample processing, molecular analysis, imaging, and computational methods to investigate the spatial and temporal regulation of A-to-I RNA editing [20] [27] [29].

The intricate regulation of cellular localization and tissue-specific expression patterns of A-to-I RNA editing components represents a crucial layer of biological control with significant implications for both basic research and therapeutic development. The dynamic shuttling of ADAR enzymes between nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments enables spatially regulated editing of diverse RNA substrates, while the heterogeneous expression across tissues and developmental stages underscores the specialized functions of RNA editing in different biological contexts. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these patterns is essential for designing targeted interventions that can modulate specific editing events in precise cellular locations and tissue types. As the field advances, particularly with the ongoing clinical development of RNA editing therapeutics, the principles outlined in this technical guide will provide a foundation for developing more precise and effective RNA-targeting therapies.

Detection Technologies and Therapeutic Applications of Programmable RNA Editing

Adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) RNA editing is a fundamental post-transcriptional modification process catalyzed by adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR) enzymes, which convert adenosines (A) to inosines (I) within double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) regions. As inosine is interpreted as guanosine (G) by cellular machinery and sequencing technologies, this process is detectable as A-to-G mismatches when comparing RNA sequences to their original DNA templates [30] [32]. The comprehensive set of A-to-I editing sites within a biological system constitutes its "editome," which exhibits cell-specific patterns and developmental regulation [30] [33]. This editing mechanism represents a critical layer of epigenetic regulation that expands transcriptomic diversity, influencing various biological processes including alternative splicing, microRNA targeting, and innate immune response modulation [30] [34] [32].

The biological significance of A-to-I RNA editing spans both physiological and pathological contexts. Editing within coding regions can alter amino acid sequences of proteins, with notable examples including glutamate receptors and serotonin receptors in neurological contexts [30] [32]. In non-coding regions, particularly in 3' untranslated regions (3'UTRs) and introns, editing can influence transcript stability, localization, and interaction with regulatory RNAs [30] [33]. Dysregulated RNA editing has been implicated in various human diseases, including neurological disorders, cancer, autoimmune diseases, and metabolic conditions, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target and biomarker source [35] [32]. Recent evidence also demonstrates RNA editing's role in specialized biological processes such as hematopoietic stem cell differentiation and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) pathogenesis, establishing it as a widespread mechanism with diverse functional implications [35] [33].

Computational Detection of A-to-I Editing from RNA-seq Data

Fundamental Principles and Challenges

Computational detection of A-to-I editing sites primarily relies on identifying A-to-G discrepancies between RNA-seq reads and reference genomic sequences. However, this seemingly straightforward approach faces significant challenges that complicate accurate editome mapping. The primary sources of false positives include: (1) sequencing errors inherent to next-generation sequencing platforms; (2) erroneous alignment of RNA-seq reads, particularly in repetitive regions; (3) genomic polymorphisms (SNPs) that manifest as apparent RNA-DNA differences; (4) somatic mutations in cancer and other tissues; and (5) spontaneous chemical RNA changes that mimic editing events [36]. The specificity of editing detection is typically validated by examining the ratio of A-to-G mismatches to other mismatch types, with genuine editing screens showing strong predominance of A-to-G changes [37] [36].

A particularly challenging aspect of editome mapping involves hyper-editing, where extensive A-to-I conversions within dsRNA regions create reads with dense A-to-G mismatch clusters. Conventional alignment algorithms typically discard these reads due to their excessive mismatch counts, rendering majority of editing sites undetectable by standard approaches [37]. One study revealed that careful alignment of previously unmapped reads uncovered 327,096 novel editing sites in human data—more than double the originally detected sites—establishing that hyper-editing accounts for the majority of editing events [37]. This limitation necessitates specialized computational approaches to comprehensively capture the full spectrum of RNA editing activity.

Core Methodological Approaches

Table 1: Computational Approaches for A-to-I RNA Editing Detection

| Method Type | Key Principle | Representative Tools | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Site Detection | Identifies individual A-to-G mismatches through strict alignment | REDItools, GIREMI | High resolution for specific sites; Works with standard RNA-seq | Misses hyper-edited regions; Requires extensive filtering |

| Hyper-editing Detection | Specialized alignment for reads with clustered A-to-G changes | Porath et al. method, RepProfile | Captures extensively edited regions; Reveals majority of editome | Computationally intensive; Complex implementation |

| Region-Based Analysis | Analyzes editing signals across genomic windows rather than single sites | LoDEI, AEI | Robust to widespread editing; Better statistical power | Lower positional resolution |

| Integrated Detection & Quantification | Simultaneously aligns reads and predicts editing patterns | RepProfile | Handles ambiguous alignments; Better for repetitive elements | Method-specific assumptions |

Single-Site Editing Detection

Single-site detection methods form the foundation of computational editome mapping, focusing on identifying individual A-to-G mismatches through rigorous alignment and filtering pipelines. A representative workflow, as applied in PCOS research, involves: (1) Quality control and adapter trimming using tools like FASTP; (2) Alignment to reference genome with splice-aware aligners such as STAR; (3) Variant calling using tools like VarScan with minimum base quality (≥25), sequencing depth (≥10), and alternative allele frequency (≥1%) thresholds; (4) Comprehensive filtering to remove variants in homopolymer runs, simple repeats, splice junctions, and known dbSNP entries; and (5) Annotation using resources like Ensembl VEP and editing databases (REDIportal) [35]. The remaining high-confidence A-to-I editing events are typically defined as those with editing levels ≥1% in multiple samples [35].

These approaches benefit from extensive filtering strategies to enhance specificity. For example, in a study investigating PCOS, researchers implemented a multi-step filtering process that eliminated variants not annotated in REDIportal unless they were located in homopolymer runs ≥5 nucleotides, within 6 nucleotides of splice junctions, or present in dbSNP [35]. This stringent approach identified 17,395 high-confidence editing sites in granulosa cells, with 56.5% located in introns and 24.5% in 3'UTRs, predominantly within Alu repetitive elements (65.5%) [35]. Functional impact prediction revealed that 50.9% of missense variants were potentially deleterious, highlighting the functional significance of accurately detected editing sites [35].

Hyper-editing Detection Algorithms

Hyper-editing detection represents a specialized approach to overcome the limitations of conventional alignment algorithms when dealing with extensively edited reads. The fundamental challenge stems from the fact that reads with dense A-to-G clusters fail to align under standard parameters, necessitating specialized computational strategies. A pioneering method for hyper-editing detection involves a four-step process: (1) Collection of unmapped reads from initial alignment; (2) In silico transformation of all A-to-G in both unmapped reads and reference genome; (3) Realignment of transformed sequences; and (4) Recovery of original sequences and identification of dense A-to-G mismatch clusters [37]. This approach dramatically increases editing site discovery, with one application uncovering 390,881 hyper-edited reads containing 455,014 unique editing sites in human data, representing a 71.9% increase over previously known sites [37].

Advanced algorithms like RepProfile further address hyper-editing detection through probabilistic modeling that simultaneously aligns reads and predicts editing patterns. This method employs an expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm that iteratively refines alignment probabilities, editing site identification, and expression level estimation [38]. Unlike methods that discard ambiguously aligned reads, RepProfile leverages the variation introduced by editing itself to distinguish between identical repetitive elements, enabling detection of editing in long, perfect dsRNA structures—the optimal ADAR substrates. Validation through Sanger sequencing confirmed the accuracy of this approach, with editing predictions concentrated in genes involved in synaptic cell-cell communication, including those associated with neurodegeneration [38].

Experimental Design and Protocols for Editome Mapping

RNA Sequencing Considerations

The foundation of successful editome mapping begins with appropriate experimental design and RNA sequencing strategies. Strand-specific RNA sequencing is particularly valuable as it preserves transcriptional directionality, allowing more accurate identification of genuine A-to-G changes versus T-to-C changes on the opposite strand [33]. For editing detection in heterogeneous samples, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) approaches have been adapted, though they present unique challenges due to lower sequencing coverage per cell. A computational pipeline to address this limitation involves: (1) Integration of aligned reads from each cell of the same type to create pseudo-bulk RNA-seq data; (2) Improved PCR duplicate removal using unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) at the cellular level; (3) Strand-specific analysis of editing sites; and (4) Leveraging editing-specific features such as enrichment in Alu elements and A-to-G changes [33]. This approach has successfully identified dynamic editing patterns during human hematopoiesis, with 17,841 editing sites detected in hematopoietic stem cells [33].