Benchmarking RNA Structure Prediction: A Comprehensive Review of Algorithms, Challenges, and Clinical Applications

The accurate prediction of RNA structure is a cornerstone for understanding gene regulation and developing RNA-based therapeutics.

Benchmarking RNA Structure Prediction: A Comprehensive Review of Algorithms, Challenges, and Clinical Applications

Abstract

The accurate prediction of RNA structure is a cornerstone for understanding gene regulation and developing RNA-based therapeutics. This article provides a comprehensive benchmark and analysis of the rapidly evolving landscape of computational methods for RNA structure prediction, from classical thermodynamics-based approaches to modern deep learning and large language models. We explore the foundational principles, methodological advances, and significant challenges such as the 'generalization crisis' and data scarcity. A special focus is placed on rigorous, homology-aware validation frameworks and curated benchmark datasets. By synthesizing performance comparisons and future directions, this review serves as an essential guide for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the tools that bridge RNA sequence to function.

The RNA Folding Problem: From Biological Roots to Computational Challenges

The Critical Link Between RNA Structure and Biological Function

Ribonucleic acids (RNAs) are versatile macromolecules involved in a vast array of cellular processes, including protein synthesis, RNA splicing, and transcription regulation [1]. The biological function of an RNA molecule is fundamentally determined by its three-dimensional (3D) structure [2]. This folding dictates the RNA's biological activity and its interactions with other molecules, such as proteins, small molecules, and other RNAs [2]. Understanding RNA structure is therefore paramount for deciphering RNA biology and has profound implications for therapeutic development, including RNA-targeting drugs and mRNA-based vaccines [3] [4]. However, the conformational flexibility of RNA molecules has made the experimental determination of their 3D structures challenging. As of December 2023, RNA-only structures constitute less than 1.0% of the ~214,000 entries in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [3]. This vast gap between known RNA sequences and solved 3D structures has driven the development of computational methods for predicting RNA 3D structures from sequence data, creating a critical need for systematic benchmarking to guide researchers and clinicians in selecting the most appropriate tools [1] [2].

Computational methods for RNA 3D structure prediction generally fall into three categories: ab initio methods, which simulate the physics of the system; template-based methods, which leverage known structural motifs; and deep learning (DL) methods, which use neural networks to predict structures from sequence or evolutionary data [1] [2]. A systematic benchmark of state-of-the-art methods reveals distinct performance trends, crucial for informed tool selection.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics of RNA 3D Structure Prediction Methods on RNA-Puzzles Datase

| Method | Type | Average RMSD (Ã…) | Average TM-Score | Key Input Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RhoFold+ [3] | Deep Learning | 4.02 | 0.57 | RNA sequence, MSA, RNA-FM embeddings |

| FARFAR2 (top 1%) [3] | Fragment Assembly | 6.32 | ~0.44 | RNA sequence, knowledge-based potential |

| DeepFoldRNA [2] | Deep Learning | Best overall | - | MSA, Secondary Structure |

| DRFold [2] | Deep Learning | Second best | - | Predicted secondary structure |

| RoseTTAFoldNA [3] | Deep Learning | Variable | - | MSA, Secondary Structure constraints |

Performance data compiled from independent benchmarking studies [3] [2]. RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) measures the average distance between atoms in predicted and experimental structures; lower is better. TM-Score measures global structural similarity; a score >0.5 indicates generally correct topology.

The benchmarking data indicates that deep learning methods generally outperform traditional fragment-assembly-based approaches [2]. Among DL methods, DeepFoldRNA achieves the best prediction results overall, closely followed by DRFold as the second-best method [2]. The performance of RhoFold+ is particularly noteworthy; a retrospective evaluation on RNA-Puzzles targets demonstrated its superiority over existing methods, including human expert groups, achieving an average RMSD of 4.02 Ã…, which was 2.30 Ã… better than the second-best model (FARFAR2) [3].

However, the benchmark also highlights a significant challenge: on "orphan RNAs" with no close evolutionary relatives in databases, the performance of DL-based methods is only marginally better than that of traditional non-ML methods, and generally, all methods perform poorly on such targets [2]. This underscores a critical limitation related to the quality and depth of Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSA), which are crucial for many DL methods [2].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of RNA 3D Structure Prediction Methods

| Method | Strengths | Limitations | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Learning (e.g., DeepFoldRNA, RhoFold+) | High accuracy on targets with good MSA coverage; End-to-end prediction [2] [3] | Performance drops on orphan RNAs; Computationally intensive MSA search [2] | Predicting structures for RNAs with evolutionary relatives |

| Fragment Assembly (e.g., FARFAR2) | Does not rely on evolutionary data; Physical realism | Lower average accuracy; Computationally intensive sampling [3] [2] | Orphan RNAs, preliminary screening |

| Ab Initio & Coarse-Grained (e.g., SimRNA, OxRNA) | Provides folding thermodynamics; Explores conformational landscape [1] | Often low resolution; Challenging to achieve atomic accuracy [1] | Studying folding pathways, large complexes |

Experimental Protocols in Algorithm Benchmarking

To ensure fair and informative comparisons, benchmarking studies follow rigorous experimental protocols. Understanding these methodologies is essential for interpreting results and applying them to real-world research problems.

Dataset Curation and Preparation

Benchmarks rely on high-quality, non-redundant datasets of experimentally determined RNA structures. A common approach involves curating all available RNA 3D structures from the PDB and processing them to create representative sets. For example, one benchmark used the BGSU representative sets of RNA structures, focusing on single-chain RNAs and reducing redundancy by clustering sequences with Cd-hit at an 80% sequence similarity threshold, resulting in 782 unique sequence clusters from 5,583 RNA chains [3]. This careful curation minimizes bias and prevents overfitting during evaluation.

Feature Extraction and Input Generation

The performance of prediction methods is heavily influenced by the quality of their inputs. Standard protocols involve:

- Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) Generation: Searching input sequences against large sequence databases (e.g., Rfam) to find homologous sequences and build MSAs, which provide evolutionarily informed constraints [3] [2].

- Secondary Structure Prediction: Using tools like Superfold or RNAstructure to predict base-pairing interactions, which serve as important constraints for 3D structure modeling [5] [2].

- Language Model Embeddings: Methods like RhoFold+ utilize large RNA language models (e.g., RNA-FM) pretrained on millions of RNA sequences to extract evolutionarily and structurally informed embeddings directly from the sequence [3].

Evaluation Metrics and Validation

To quantitatively assess prediction accuracy, benchmarks employ several standardized metrics:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures the average distance between corresponding atoms in predicted and experimental structures after optimal superposition. Lower values indicate better accuracy [3].

- Template Modeling (TM) Score: A superposition-free metric that assesses global structural similarity. A score >0.5 indicates generally correct topology, with higher scores being better [3].

- Local Distance Difference Test (lDDT): A superposition-free score that evaluates local distance differences for all atoms in a model, providing a more robust measure of local accuracy [3].

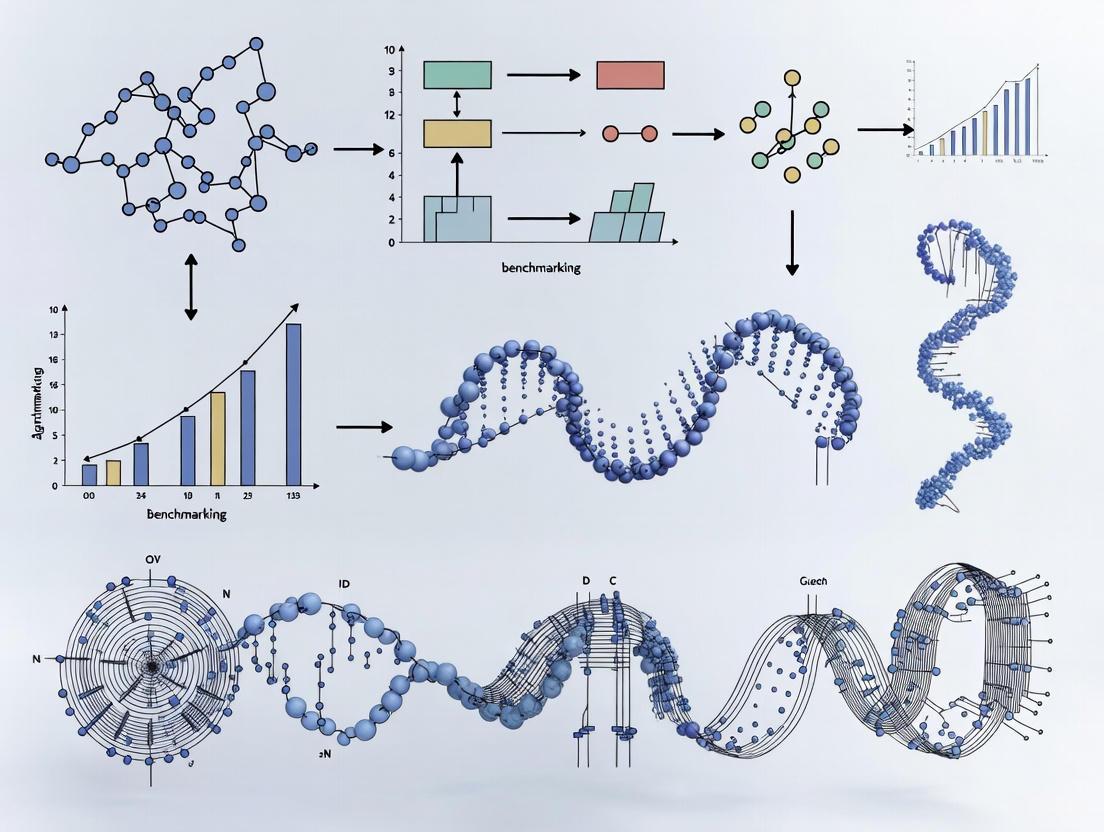

The following diagram illustrates the typical end-to-end workflow for benchmarking RNA structure prediction methods, from data preparation to performance evaluation:

Successful RNA structure prediction and validation requires a suite of computational tools and resources. The table below details key solutions used in the featured benchmarking experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for RNA Structure Analysis

| Resource / Tool | Type | Primary Function | Application in Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|---|

| RhoFold+ [3] | Deep Learning Model | End-to-end RNA 3D structure prediction | State-of-the-art method for single-chain RNA prediction |

| DeepFoldRNA [2] | Deep Learning Model | Predicts 3D structures using MSA and secondary structure | Top-performing method in independent benchmarks |

| RNA-FM [3] | Language Model | Generates evolutionarily informed RNA sequence embeddings | Provides feature representations for RhoFold+ |

| ViennaRNA [4] | Software Package | Predicts RNA secondary structure and folding dynamics | Provides secondary structure constraints |

| RSCanner [5] | R Package | Scans RNA transcripts for structured regions | Identifies stable regions for downstream structural analysis |

| Rfam [5] | Database | Collection of RNA families and alignments | Source for MSA construction and evolutionary data |

| BGSU Representative Sets [3] | Curated Dataset | Non-redundant collection of RNA structures | Training and testing data for method development |

The systematic benchmarking of RNA structure prediction algorithms reveals a rapidly evolving field where deep learning methods have established a clear performance advantage for RNAs with evolutionary relatives. Tools like DeepFoldRNA and RhoFold+ represent the current state-of-the-art, demonstrating remarkable accuracy on standardized tests like RNA-Puzzles [3] [2]. However, significant challenges remain, particularly for orphan RNAs and conformationally dynamic molecules.

The critical link between RNA structure and biological function continues to drive methodological innovations. Future progress will likely depend on several key factors: expanding the database of experimentally solved RNA structures to improve training data for DL methods, developing better approaches for predicting non-Watson-Crick base pairs, and creating algorithms that can more effectively handle RNA's inherent structural dynamics [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the current benchmarking data provides valuable guidance for tool selection while highlighting the importance of choosing methods aligned with specific research goals, whether studying well-conserved RNA families or exploring the vast landscape of RNAs with unknown structures.

The Widening Sequence-Structure Gap and the Need for Computational Tools

The field of RNA biology is experiencing a data deluge. Advances in high-throughput sequencing have generated an immense volume of RNA sequence data, with over 85% of the human genome transcribed but only 3% encoding proteins [3]. This has created a rapidly widening gap between the number of known RNA sequences and those with experimentally determined structures. RNA-only structures comprise less than 1.0% of the ~214,000 structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), and RNA-containing complexes account for only 2.1% [3]. This disparity, known as the sequence-structure gap, represents a critical bottleneck in understanding RNA function and developing RNA-targeted therapeutics.

The conformational flexibility of RNA molecules has made experimental determination of their three-dimensional structures particularly challenging. Traditional methods like X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, and cryogenic electron microscopy, while valuable, remain low-throughput techniques with specialized requirements [3]. This limitation has propelled computational methods from complementary approaches to essential tools for bridging the sequence-structure divide. The development of accurate computational predictors is particularly crucial for RNA-based therapeutic design, where structure determines function, interaction capabilities, and ultimately, drug efficacy [6] [3].

Computational methods for RNA structure prediction have evolved into several distinct categories, each with unique strengths, limitations, and underlying methodologies. The table below summarizes the primary approaches currently employed by researchers.

Table 1: Computational Approaches for RNA Structure Prediction

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Key Principles | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamics-Based | RNAfold, RNAstructure [7] | Minimizes free energy using empirical parameters [7] | Physically intuitive principles | Limited by inaccurate energy parameters [7] |

| Fragment Assembly | Rosetta FARFAR2 [6] | Assembles 3D structures from RNA fragments [6] | Atomic-detail modeling | Computationally intensive; performance depends on secondary structure input [6] |

| Motif Assembly | RNAComposer [6] | Builds 3D structures using known structural motifs [6] | Fast prediction speed | Dependent on secondary structure input [6] |

| Deep Learning (MSA-based) | AlphaFold 3, RhoFold+ [3] | Uses multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) and deep learning | High accuracy demonstrated in benchmarks [3] | MSA construction is time-consuming [3] |

| Deep Learning (Language Models) | ERNIE-RNA, RNA-FM, RiNALMo [7] [8] | Learns representations from sequences using transformer architectures | No MSA required; faster inference [8] | Struggles with low-homology scenarios [8] |

The Emergence of RNA Language Models

A recent paradigm shift in the field has been the development of RNA Language Models (RNA-LMs). Inspired by success in protein and DNA modeling, these models are based on the Transformer architecture, particularly Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) [8]. They learn semantically rich numerical representations (embeddings) for each RNA base by training on massive datasets of RNA sequences in a self-supervised manner, typically using a Masked Language Modeling (MLM) objective where random bases in the input sequence are masked and predicted [8]. The hypothesis is that these embeddings capture evolutionary, structural, and functional information that can enhance performance on downstream tasks like structure prediction, even with limited labeled data [8].

Table 2: Overview of Representative RNA Large Language Models

| RNA-LLM | Year | Embedding Dimension | Pretraining Sequences | Model Parameters | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNA-FM [8] | 2022 | 640 | 23.7 million | ~100 million | Pioneer general-purpose model trained on massive dataset |

| RNABERT [8] | 2022 | 120 | 76,237 | ~0.5 million | Incorporates Structural Alignment Learning (SAL) |

| ERNIE-RNA [7] [8] | 2024 | 768 | 20.4 million | ~86 million | Base-pairing informed attention bias |

| RiNALMo [8] | 2024 | 1280 | 36.0 million | ~650 million | Largest model; uses rotary positional embeddings |

| RNA-MSM [8] | 2024 | 768 | 3.1 million | ~96 million | Incorporates Multiple Sequence Alignment information |

Benchmarking Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

To objectively evaluate the performance of various computational tools, rigorous benchmarking against experimentally determined structures is essential. Standardized protocols and metrics allow for meaningful comparisons between methods.

Standard Evaluation Metrics and Datasets

The following metrics are commonly used to assess prediction accuracy:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures the average distance between corresponding atoms in predicted and experimental structures after optimal superposition. Lower values indicate better accuracy [6].

- Template Modeling (TM) Score: A metric for assessing the global similarity of two structures, with values ranging from 0 to 1 (higher is better) [3].

- Local Distance Difference Test (LDDT): A superposition-free score that evaluates local distance differences for all atoms in a model [3].

Commonly used benchmark datasets include:

- RNA-Puzzles: A community-wide blind trial for RNA structure prediction featuring various RNA targets [3].

- CASP15: The Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction competition, which includes RNA targets [3].

- BGSU Representative Sets: Curated sets of RNA structures from the PDB with reduced redundancy [3].

Experimental Workflow for Comparative Evaluation

The diagram below illustrates a standardized workflow for benchmarking RNA structure prediction tools, from data preparation to performance assessment.

Figure 1: Standard workflow for benchmarking RNA structure prediction algorithms.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for RNA Structure Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [6] | Repository of experimentally determined 3D structures | Source of ground truth data for training and benchmarking |

| Sequence Databases | RNAcentral [7] [8] | Comprehensive database of non-coding RNA sequences | Source of sequences for pre-training language models |

| Secondary Structure Predictors | RNAfold, CONTRAfold [6] | Predict RNA secondary structure from sequence | Provide input for methods like RNAComposer and FARFAR2 |

| Analysis & Visualization | PyMOL [6] | Molecular visualization system | Structural comparison and RMSD calculation |

| Specialized Benchmarks | RNA-Puzzles [3] | Community-wide blind prediction challenges | Standardized assessment of method performance |

Comparative Performance Analysis of Computational Tools

Performance on Established Benchmarks

Independent benchmarking studies provide crucial insights into the relative strengths of various approaches. A comprehensive 2025 evaluation of RNA Language Models revealed that while these models show promise, their performance varies significantly, particularly in challenging low-homology scenarios [8]. The study, which used a unified experimental setup across four benchmarks of increasing complexity, found that two LLMs (not named in the abstract) clearly outperformed others, though all models faced significant challenges in cross-family predictions [8].

Retrospective evaluations on the RNA-Puzzles dataset demonstrate the superiority of newer deep learning methods. RhoFold+ achieved an average RMSD of 4.02 Ã…, significantly outperforming the second-best method (FARFAR2 at 6.32 Ã…) [3]. Similarly, on 17 of 24 RNA-Puzzles targets, RhoFold+ achieved RMSD values of <5 Ã…, with an average TM-score of 0.57, higher than other top performers (0.41-0.44) [3].

For tertiary structure prediction, studies comparing RNAComposer, Rosetta FARFAR2, and AlphaFold 3 on RNAs with known structures found that AlphaFold 3 generally produced more accurate structures directly from primary sequences, though with varying confidence levels [6]. In one case, RNAComposer achieved an RMSD of 2.558 Ã… for a Malachite Green Aptamer crystal structure, while AlphaFold 3 and FARFAR2 achieved 5.745 Ã… and 6.895 Ã…, respectively [6].

Performance Across RNA Types and Sizes

Tool performance varies considerably depending on RNA type and size. The table below summarizes quantitative results from comparative studies.

Table 4: Comparative Performance of RNA 3D Structure Prediction Tools

| RNA Target | Length (nt) | RNAComposer (RMSD) | FARFAR2 (RMSD) | AlphaFold 3 (RMSD) | RhoFold+ (RMSD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malachite Green Aptamer [6] | 38 | 2.558 Ã… | 6.895 Ã… | 5.745 Ã… | - |

| Human Glycyl-tRNA-CCC [6] | 76 | 5.899 Ã…* | 12.734 Ã…* | - | - |

| RNA-Puzzles Average [3] | Various | - | 6.32 Ã… | - | 4.02 Ã… |

| Varkud Satellite Ribozyme (PZ7) [3] | 186 | - | - | - | <5.0 Ã… |

Note: *With CONTRAfold secondary structure input; *Top 1% model*

Contextual Factors Influencing Tool Performance

Several contextual factors significantly impact tool performance:

Dependence on Secondary Structure Input: Traditional methods like RNAComposer and FARFAR2 show high sensitivity to the quality of secondary structure input. For human glycyl-tRNA, RNAComposer's RMSD improved from 16.077 Ã… to 5.899 Ã… when using CONTRAfold instead of RNAfold for secondary structure prediction [6].

Generalization Capabilities: Benchmarking studies indicate that methods like RhoFold+ show no significant correlation (R²=0.23 for TM-score) between performance and sequence similarity to training data, suggesting better generalization capabilities compared to template-based methods [3].

Impact of Training Data Composition: Studies with ERNIE-RNA demonstrated that model performance consistently improved with increasing training data size, while exclusion of specific RNA types (rRNA/tRNA or lncRNA) had minimal influence on perplexity, suggesting robust learning across RNA families [7].

Integrated Workflow and Future Directions

Recommended Integrated Approach for RNA Structure Analysis

Based on current benchmarking results, an integrated workflow leveraging the complementary strengths of different tools provides the most robust approach for RNA structure analysis. The following diagram illustrates a recommended pipeline.

Figure 2: Integrated workflow combining multiple computational approaches.

Emerging Trends and Research Directions

The field of RNA structure prediction is rapidly evolving with several promising directions:

Hybrid Methods: Combining the strengths of different approaches, such as using language model embeddings as input to physics-based or deep learning methods, shows promise for improving accuracy [9] [8].

Structure-Aware Language Models: Newer models like ERNIE-RNA, which incorporate base-pairing restrictions into the attention mechanism, demonstrate enhanced capability to capture structural features, achieving F1-scores up to 0.55 in zero-shot secondary structure prediction [7].

Addressing Generalization Gaps: Current research focuses on improving performance in low-homology scenarios, where even advanced LLMs face significant challenges [8].

Integration with Experimental Data: Methods that incorporate experimental constraints, such as chemical probing data, are emerging as powerful approaches for resolving structural ambiguities.

As the sequence-structure gap continues to widen, the development and rigorous benchmarking of computational tools remains essential for unlocking the functional secrets of RNA molecules. The integration of language model representations with physical constraints and experimental data represents the most promising path forward for accurate, generalizable RNA structure prediction.

{# The Historical Shift in Computational Methods}

::: {.callout-color} Summary of the Historical Shift in RNA Structure Prediction

| Era | Core Paradigm | Representative Methods | Key Strengths | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical | Thermodynamics & Alignment | RNAup, IntaRNA, RNAplex [10] | High positive predictive value (PPV), strong physical interpretability [10] | Limited by accuracy of energy parameters, struggles with remote homology [10] [7] |

| Modern | Deep Learning & Language Models | ERNIE-RNA, RhoFold+, DeepFoldRNA [7] [3] [2] | State-of-the-art accuracy, captures long-range dependencies, generalizes across families [7] [3] [2] | Dependent on quality and size of training data; performance can drop on "orphan" RNAs [2] |

:::

The field of RNA structure prediction has undergone a profound transformation, shifting from classical thermodynamics-based models to modern data-driven paradigms powered by deep learning. This evolution is centrally framed by rigorous benchmarking research that objectively quantifies the capabilities and limitations of each approach, providing critical insights for researchers and drug development professionals [10] [2].

Classical Foundations: Thermodynamics and Alignment

The classical paradigm for predicting RNA structure and interactions is rooted in biophysical principles and sequence alignment.

Core Principles and Methodologies

Classical algorithms primarily rely on calculating the Minimum Free Energy (MFE) of a given RNA sequence, operating on the principle that the native structure is the one with the lowest thermodynamic energy [10]. Alternatively, alignment-based methods use dynamic programming to identify stable interactions through local sequence complementarity [10]. Benchmarking studies often create a realistic testing environment by using entire target regions, such as full UTRs or coding sequences, rather than just short binding snippets [10].

A standard benchmarking protocol involves several key steps. First, researchers compile a dataset of manually curated and verified RNA-RNA interactions from diverse organisms, including eukaryotes, bacteria, and archaea [10]. To assess binding site prediction accuracy, performance is measured using:

- True Positive Rate (TPR/Sensitivity): The proportion of true binding nucleotides correctly identified.

- Positive Predictive Value (PPV/Precision): The proportion of predicted binding nucleotides that are correct [10].

The statistical significance of interaction scores is evaluated by comparing predictions for true targets against those for hundreds of dinucleotide-shuffled negative control sequences [10].

Performance and Limitations

Comprehensive benchmarks show that MFE tools which incorporate accessibility (e.g., RNAup, IntaRNA, RNAplex) achieve superior performance. They demonstrate high PPV across diverse datasets and can differentiate nearly half of all native interactions from non-functional backgrounds [10].

However, these methods face inherent constraints. Their accuracy is limited by the completeness and precision of their thermodynamic parameters [7]. Furthermore, purely alignment-based methods exhibit low PPV despite high TPR, and comparative techniques are ineffective for RNAs with few homologous sequences [10].

The Modern Paradigm: Deep Learning and Language Models

The advent of deep learning, particularly RNA language models (RLMs), represents a fundamental shift toward data-driven reasoning, moving away from reliance on pre-defined energy rules.

Architectural Innovations and Training

Modern RLMs are pre-trained on millions of non-annotated RNA sequences from databases like RNAcentral in a self-supervised manner, learning semantically rich representations of RNA bases [7] [11]. A key innovation is the move beyond single sequences to leverage evolutionary information through Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs), though this can be computationally expensive [3] [2].

These models integrate structural priors directly into their architecture. For instance, ERNIE-RNA modifies the transformer's self-attention mechanism with a base-pairing bias matrix, encouraging the model to attend to potentially pairing nucleotides based on canonical (AU, CG, GU) pairing rules [7]. For 3D structure prediction, models like RhoFold+ employ a complex, integrated workflow where RNA-FM embeddings and MSA features are processed by a transformer network (Rhoformer), and then a structure module with Invariant Point Attention (IPA) refines atomic coordinates [3].

Performance Benchmarks for Tertiary Structure

Independent, systematic benchmarking reveals that deep learning methods generally outperform traditional fragment-assembly approaches, with DeepFoldRNA consistently ranking as a top performer [2].

::: {.callout-color} Benchmarking Performance of Modern RNA 3D Structure Prediction Methods [2]

| Method | Core Input Features | Key Performance Insight |

|---|---|---|

| DeepFoldRNA | MSA, Secondary Structure | Best predicted models overall in independent benchmarks |

| RhoFold+ | RNA-FM embeddings, MSA | Superior performance on RNA-Puzzles, generalizes well to sequence-dissimilar targets [3] |

| DRfold | Predicted Secondary Structure | Second best in some benchmarks; faster as it is MSA-free but generally lower accuracy [2] |

| RoseTTAFold2NA | MSA, Secondary Structure | Deep learning-based method for RNA 3D structure prediction [2] |

| Fragment-Assembly (Non-ML) | Physics-based Principles | Outperformed by ML methods, especially on targets with available homologs [2] |

:::

These methods demonstrate a remarkable ability to generalize. For example, RhoFold+'s performance on RNA-Puzzles showed no significant correlation with sequence similarity between test and training data, indicating it learns fundamental structural principles rather than merely memorizing templates [3].

Critical Analysis: Performance Across Real-World Challenges

Benchmarking across diverse scenarios reveals the nuanced strengths and weaknesses of modern data-driven models.

The "Orphan RNA" and Low-Homology Challenge

A significant challenge for ML methods is predicting structures for "orphan RNAs" — those with no or few sequence homologs in databases [2]. In low-homology scenarios, the performance advantage of DL methods over traditional techniques narrows considerably, and all methods perform poorly [2] [11]. This underscores that the evolutionary information captured in MSAs remains a critical factor for accuracy, and its absence is a major limitation [2].

Secondary Structure and Non-Canonical Pairs

Most deep learning methods rely on or co-predict secondary structure as an intermediate step, and the quality of this prediction is a major determinant of final 3D model accuracy [2]. However, a common weakness is that most current methods are unable to accurately predict non-Watson-Crick base pairs, which are crucial for forming complex tertiary folds [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

::: {.callout-color} Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Benchmarking

| Item | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Verified Interaction Datasets | Curated gold-standard data for training and benchmarking algorithms [10] | Eukaryotic miRNAs, bacterial sRNA-mRNA pairs [10] |

| BGSU Representative RNA Sets | Non-redundant, clustered RNA structures for unbiased evaluation [3] [2] | Training and testing sets for 3D structure prediction methods [3] |

| Dinucleotide-Shuffled Sequences | Generate negative control sequences for statistical validation [10] | Significance testing of predicted interaction scores [10] |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) Tools | Provide evolutionary information crucial for many DL models [3] [2] | Input for methods like DeepFoldRNA and RhoFold+ |

| RNA-Puzzles and CASP Targets | Blind community-wide challenges for impartial assessment [3] [2] | Retrospective benchmarking against other methods and expert groups [3] |

| 6-Hydroxyflavanone | 6-Hydroxyflavanone|High-Purity Research Compound | 6-Hydroxyflavanone is a flavanone for neuroscience and oncology research. It shows efficacy in models of anxiety and chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Sinapine thiocyanate | Sinapine thiocyanate, CAS:7431-77-8, MF:C17H24N2O5S, MW:368.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

:::

Experimental Workflow and Logical Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow and logical progression for a comprehensive benchmarking study of RNA structure prediction methods, from dataset preparation to final performance evaluation.

The historical shift from thermodynamic models to data-driven paradigms, rigorously documented through benchmarking, has unequivocally advanced the field of RNA structure prediction. Modern deep learning and language model-based methods have set new standards for accuracy, particularly for RNAs with evolutionary relatives. However, benchmarking research also clearly delineates the frontier of current capabilities: the accurate prediction of orphan RNAs and complex features like non-Watson-Crick pairs remains a significant challenge. Future progress will likely hinge on developing models that are less dependent on deep MSAs and can more effectively learn the biophysical rules of RNA folding from sequence alone. For researchers and drug developers, this evidence-based comparison underscores the importance of selecting prediction tools that are best suited for their specific RNA target of interest, considering factors such as RNA type, available homology, and the criticality of predicting non-canonical interactions.

Accurate prediction of RNA structure is fundamental to understanding its diverse biological functions and for applications in drug design and synthetic biology. While computational methods have made significant strides, three persistent obstacles critically define the frontier of current research: the profound scarcity of high-quality experimental data, the intricate challenge of predicting pseudoknots, and the need to represent RNA dynamic conformational ensembles. Benchmarking studies are essential for objectively evaluating how well new computational approaches address these hurdles. This guide provides a comparative analysis of contemporary algorithms, detailing their performance on standardized tasks, the experimental protocols used for validation, and the key reagents that empower this research. By framing the discussion within the context of these three core challenges, we offer a structured framework for researchers to assess the capabilities and limitations of current prediction tools.

Obstacle 1: Data Scarcity and Its Impact on Model Training

The development of robust deep learning models for RNA structure prediction is severely constrained by the limited availability of experimentally determined structures. RNA structures comprise less than 1% of the Protein Data Bank (PDB), creating a fundamental bottleneck for training data-intensive models [3] [12]. This scarcity is particularly acute for long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and for 3D structure prediction, where the number of known structures is orders of magnitude smaller than for proteins [12] [13]. Consequently, models risk overfitting, and their generalizability to novel RNA classes or long sequences remains questionable.

To combat this, researchers leverage large-scale public data repositories and develop innovative training strategies. Key resources include the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), which house vast amounts of raw sequencing data, and the ENCODE project, which provides quality-controlled functional genomics data [13]. For constructing specialized benchmarks, datasets like the one comprising over 320,000 instances from the RNAsolo and Rfam databases are becoming community standards, enabling more rigorous training and evaluation of algorithms for RNA design and structure prediction [14].

Table 1: Key Public Data Sources for RNA Structure Research

| Database/Resource | Primary Content | Utility in Overcoming Data Scarcity |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Experimentally determined 3D structures of biomolecules. | Primary source of RNA 3D structures for training and testing; though RNA content is sparse [3]. |

| Rfam | Database of RNA families, with alignments and consensus secondary structures. | Provides a large collection of RNA sequences and their inferred secondary structures for model training [14]. |

| RNAsolo | A curated database derived from PDB, focusing on isolated RNA structures. | Offers a cleaned and annotated set of RNA 3D structures, reducing redundancy and improving data quality [14]. |

| Eterna100 | A manually curated set of 100 distinct secondary structure design challenges. | Serves as a benchmark for testing RNA inverse folding algorithms [14]. |

Obstacle 2: Predicting Pseudoknots and Long-Range Interactions

Pseudoknots are a key structural motif where a loop pairs with a complementary sequence outside its own stem, forming a bipartite helical structure. They are critically important for the function of many RNAs, including ribozymes and viral RNAs, but their prediction has been notoriously difficult [15] [12]. Thermodynamic-based prediction of pseudoknotted structures is an NP-hard problem, leading many traditional algorithms to avoid them entirely or use heuristic strategies that cannot guarantee optimal structure quality [15].

Recent deep learning approaches have made significant progress. KnotFold exemplifies a modern solution by integrating an attention-based neural network with a minimum-cost flow algorithm. The self-attention mechanism captures long-distance interactions and non-nested base pairs essential for pseudoknot identification, while the network flow algorithm efficiently finds the optimal combination of base pairs without restricting pseudoknot types [15]. Benchmarking on a set of 1,009 pseudoknotted RNAs (PKTest) demonstrated that KnotFold achieves higher accuracy than previous state-of-the-art methods [15].

Table 2: Comparative Performance on Pseudoknot Prediction

| Method | Core Approach | Reported Performance on PKTest (F1-score) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| KnotFold | Attention-based NN + Minimum-cost flow algorithm | > State-of-the-art (Exact value not specified in context) | Considers all possible base pair combinations; avoids hand-crafted energy functions [15]. |

| SPOT-RNA | Deep learning for base pairing probabilities. | (Baseline for comparison) | An earlier deep learning approach that demonstrated the potential of ML for base pair prediction [15] [14]. |

| E2Efold | Differentiable end-to-end deep learning model. | (Baseline for comparison) | Designed to learn constraints directly from data rather than relying on traditional rules [15]. |

| UFold | Deep learning on 2D representation of RNA sequence. | (Baseline for comparison) | Uses a fully convolutional network on images of RNA sequences to predict structures [15]. |

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking Pseudoknot Prediction

The standard protocol for evaluating pseudoknot prediction involves several key steps to ensure a fair and meaningful comparison:

- Benchmark Dataset Curation: A standardized dataset of RNA sequences with known pseudoknotted structures is essential. The PKTest set, comprising 1,009 pseudoknotted RNAs, is a representative example used for this purpose [15]. It is crucial that the test sequences are non-homologous with any data used in the training of the models to prevent overfitting.

- Metrics for Evaluation: The standard metrics used are:

- Comparative Execution: All algorithms are run on the same benchmark dataset using their default parameters or recommended settings. The resulting predicted structures are then compared against the experimentally determined reference structures.

- Statistical Analysis: The performance metrics are calculated for each method, and statistical tests should be conducted to determine if the differences in performance are significant [16].

Diagram 1: Pseudoknot Benchmarking Workflow

Obstacle 3: Capturing Dynamic Structural Ensembles

RNA is not a static molecule; it exists as a dynamic ensemble of conformations that are critical for its function [17] [18]. Traditional experimental methods and computational predictions often provide only a single "snapshot" of the structure, averaging signals from multiple conformations and failing to capture the inherent flexibility and heterogeneity of RNA [12]. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations can model these dynamics but are computationally prohibitive for exploring large conformational spaces [17].

Generative AI models are now emerging to address this challenge directly. DynaRNA is a diffusion-based model that generates diverse RNA conformational ensembles. It employs a Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (DDPM) with an Equivariant Graph Neural Network (EGNN) to directly model RNA 3D coordinates, enabling rapid exploration of the conformational landscape orders of magnitude faster than MD simulations [17]. In benchmarks, it has demonstrated the ability to capture rare excited states, such as in the HIV-1 TAR RNA, and accurately reproduce de novo folding of tetraloops [17]. While AlphaFold3 can also predict nucleic acid structures, it is predominantly confined to predicting single, stable conformations rather than generating a full ensemble [17].

Table 3: Comparative Performance on Dynamic Ensemble Prediction

| Method | Core Approach | Reported Performance | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| DynaRNA | Diffusion model with E(3)-equivariant GNN. | Captures rare excited state of HIV-1 TAR; Recapitulates tetraloop folding. | Generates a diverse conformational ensemble; Fast sampling compared to MD [17]. |

| AlphaFold3 | Diffusion-based architecture for biomolecules. | High accuracy on single-state predictions (e.g., RNA-Puzzles). | Extends accurate structure prediction to nucleic acids and complexes [17] [3]. |

| Molecular Dynamics | Physics-based simulation of atomic movements. | Reference for "ground truth" dynamics. | Models time-resolved dynamics with high theoretical fidelity, but is computationally expensive [17]. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating Structural Ensembles

Validating predicted conformational ensembles requires comparing their statistical properties against experimental or simulation-derived references.

- Generation: DynaRNA uses a partial noising scheme (e.g., 800 steps out of a full 1024) on an input RNA structure, followed by a reverse denoising process to generate a diverse set of conformations [17].

- Validation against Reference Data: The generated ensemble is compared to a reference, such as an ensemble from long-timescale MD simulations using the D. E. SHAW force field [17].

- Key Comparison Metrics:

- Jensen-Shannon (JS) Divergence: Measures the similarity between the probability distributions of structural features (e.g., distances, angles) in the generated and reference ensembles. A lower value indicates better agreement [17].

- Radius of Gyration (Rg): A measure of the overall compactness of the molecule. The distribution of Rg in the ensemble should match the reference.

- Local Geometry Fidelity: Bond lengths and angles (e.g., C5'–C4' bond length) in the generated ensemble are compared against high-resolution RNA structures in the PDB, with Mean Absolute Error (MAE) as a key metric [17].

Advancing the field of RNA structure prediction relies on a suite of computational and data resources. Below is a table of key "research reagents" essential for benchmarking and development.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for RNA Structure Benchmarking

| Resource / Tool | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| BGSU Representative Sets | Curated Dataset | Provides non-redundant, high-quality RNA 3D structures from the PDB, essential for training and testing without data leakage [3]. |

| RhoFold+ | Prediction Algorithm | An RNA language model-based method that sets a high benchmark for accurate 3D structure prediction of single-chain RNAs on tests like RNA-Puzzles [3]. |

| KnotFold | Prediction Algorithm | A tool specifically designed to benchmark against, due to its advanced handling of pseudoknots using a minimum-cost flow algorithm [15]. |

| DynaRNA | Prediction Algorithm | A generative model used to benchmark the ability to predict dynamic conformational ensembles, not just single structures [17]. |

| FARFAR2 | Prediction Algorithm | A widely used de novo RNA 3D structure prediction method (from the Rosetta suite) that serves as a traditional baseline in performance comparisons [3]. |

| RnaBench | Benchmark Library | A library providing standardized benchmarks, datasets, and evaluation protocols for RNA structure prediction and design tasks [14]. |

Diagram 2: From Obstacles to AI Solutions

A Taxonomy of Modern RNA Structure Prediction Algorithms

RNA structure prediction is a fundamental problem in computational biology, where function is largely determined by molecular structure. Classical computational approaches, developed over decades, provide the foundation for understanding RNA biology without sole reliance on expensive experimental methods. These methods primarily fall into three categories: energy-based methods that predict structures by minimizing free energy; co-evolutionary methods that leverage comparative sequence analysis; and grammar-based methods that use formal syntactic rules to model structural motifs. This guide objectively compares the performance and methodologies of these classical approaches, framing them within contemporary benchmarking studies to highlight their enduring relevance and specific applications in modern RNA research pipelines.

The three classical approaches employ distinct principles and algorithms to solve the RNA secondary structure prediction problem. The table below summarizes their core characteristics, advantages, and limitations.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Classical RNA Secondary Structure Prediction Methods

| Method Category | Fundamental Principle | Typical Algorithms | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy-Based | Finds the structure with the Minimum Free Energy (MFE) using thermodynamic parameters [19] | RNAfold (ViennaRNA), RNAstructure [20] | • Strong physicochemical basis• Does not require multiple sequences• Fast prediction for single sequences | • Accuracy limited by energy parameter quality [19]• Struggles with pseudoknots and non-canonical pairs [20] |

| Co-evolutionary | Identifies covarying mutations in evolutionarily related sequences to infer base pairs [20] | Comparative sequence analysis, Pfold [21] | • Highly accurate for conserved RNA families [20]• Can predict complex structures | • Requires a set of homologous sequences• Performance drops for novel or isolated sequences [20] |

| Grammar-Based | Uses formal syntactic rules (e.g., SCFGs) to generate probable secondary structures [22] [21] | Stochastic Context-Free Grammars (SCFGs) [21] | • Strong statistical foundation• Unifies structure and evolution modeling (e.g., Pfold) [21] | • Grammar design can be arbitrary [21]• Model training requires curated data |

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

Benchmarking on large, diverse datasets is crucial for obtaining reliable performance measures of RNA structure prediction algorithms. Studies have shown that average accuracy on small, specific RNA classes can be misleading, with confidence intervals for F-measure having an 8% range on a set of 89 Group I introns, compared to a more reliable 2% range on datasets with over 2000 RNAs [19].

The following table summarizes the quantitative performance of these classical methods based on historical benchmarking efforts.

Table 2: Benchmarking Performance of Classical RNA Structure Prediction Methods

| Method Category | Representative Algorithm & Parameters | Reported F-Measure (Sensitivity, PPV) | Benchmark Dataset & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy-Based | MFE with BL* parameters [19] | 0.686 | Large dataset (S-Full, 3245 sequences). BL* parameters slightly outperformed CG* and Turner99 [19]. |

| Energy-Based | MFE with Turner99 parameters [19] | ~0.66 (inferred) | Performance is significantly lower than with optimized BL* parameters [19]. |

| Grammar-Based | Pseudo-MEA (Hamada et al.) with BL* parameters [19] | 0.711 | Outperformed both standard MEA-based and MFE methods on large datasets [19]. |

| Grammar-Based | SCFG (Manually Designed) [21] | ~0.64 (varies by grammar) | Performance highly dependent on specific grammar design [21]. |

Key Experimental Protocols in Benchmarking

The performance data presented in the previous section is derived from standardized experimental protocols designed to ensure fair and statistically robust comparisons.

- Dataset Curation: Benchmarking relies on large, non-redundant datasets of RNA sequences with known, experimentally validated reference structures. The S-Full dataset, comprising 3,245 sequences, is an example of a comprehensive benchmark set [19]. Sequences are often clustered to remove redundancy (e.g., at 80% sequence identity) to prevent bias [3].

- Accuracy Metrics: The primary metrics for evaluation are:

- Sensitivity (SN): The proportion of correctly predicted base pairs relative to all base pairs in the reference structure.

- Positive Predictive Value (PPV): The proportion of correctly predicted base pairs relative to all predicted base pairs.

- F-Measure: The harmonic mean of Sensitivity and PPV, providing a single balanced metric (F = 2 * SN * PPV / (SN + PPV)) [19].

- Statistical Validation: To ensure reliability, statistical methods like the bootstrap percentile method are used to establish confidence intervals for reported accuracies, confirming that performance differences on a given dataset are representative of broader trends [19].

- Cross-Family Validation: To test generalizability, family-wise cross-validation is employed, where models are trained on sequences from certain RNA families and tested on entirely different families. This is crucial for assessing performance on "out-of-distribution" RNAs [20].

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for benchmarking RNA secondary structure prediction algorithms, highlighting key steps from data curation to final statistical validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The development and benchmarking of classical RNA structure prediction methods rely on a set of key computational "reagents" – datasets, software, and parameters.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Classical RNA Structure Prediction Research

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Example / Source | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Datasets | Data | Provide known structures for training and benchmarking algorithms. | ArchiveII (3966 RNAs) [20], bpRNA-TSO (1305 RNAs) [20], S-Full (3245 RNAs) [19] | ||

| Thermodynamic Parameters | Parameters | Provide free energy values for motifs (helices, loops) for energy-based methods. | Turner99 parameters [19], BL/CG parameters [19] | ||

| Non-Redundant PDB Sets | Data | Provide high-quality, experimentally solved 3D structures for validation and method development. | BGSU representative RNA sets [3] | ||

| Homologous Sequence Databases | Data | Provide multiple sequence alignments for co-evolutionary and some grammar-based methods. | Rfam database [20] [1] | ||

| Grammar Production Rules | Model | Define the syntactic rules for generating secondary structures in grammar-based approaches. | Rules in Double Emission Normal Form (e.g., T → . | (U) | UV) [21] |

| Parsing Algorithms | Software | Execute the grammars to find the most likely structure for a given sequence. | CYK (Cocke-Younger-Kasami) algorithm, Earley parser [22] [21] | ||

| Soyasaponin II | Soyasaponin II | Explore Soyasaponin II, a Group B soyasaponin with key research applications in metabolic and cellular studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals | ||

| Squalamine | Squalamine, CAS:148717-90-2, MF:C34H65N3O5S, MW:628.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Energy-based, co-evolutionary, and grammar-based methods form the classical foundation of RNA secondary structure prediction. Benchmarking reveals that no single approach is universally superior; each has distinct strengths and operational domains. Energy-based methods offer speed and physical interpretability, co-evolutionary methods provide high accuracy for conserved families, and grammar-based methods offer a powerful statistical framework. The integration of their core principles—thermodynamic stability, evolutionary information, and syntactic modeling of structure—continues to inspire and underpin modern deep-learning approaches, cementing their role as essential components in the computational biologist's toolkit.

The field of RNA structure prediction is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the adoption of advanced deep learning architectures. For decades, computational methods relied primarily on thermodynamic models and evolutionary analysis, which eventually plateaued in accuracy due to fundamental limitations in handling complex structural motifs and non-nested base pairs [23]. The emergence of deep learning has catalyzed a shift from these traditional paradigms to data-driven approaches that learn the complex sequence-to-structure mapping directly from experimental and synthetic data [23]. This revolution centers on two dominant architectural philosophies: fully end-to-end models that directly predict atomic coordinates or contact maps, and hybrid architectures that strategically integrate deep learning with biophysical principles or evolutionary information.

This comparison guide examines the current landscape of deep learning methods for RNA structure prediction within the critical context of benchmarking and generalization. Despite significant performance gains, the field faces a "generalization crisis" where powerful models often fail on unseen RNA families, prompting a community-wide shift to stricter, homology-aware benchmarking protocols [23]. Furthermore, unlike protein structure prediction which benefits from abundant structural data, RNA prediction methods must overcome the challenge of data scarcity, with RNA-only structures comprising less than 1.0% of the Protein Data Bank [3]. We objectively compare the performance, architectural trade-offs, and experimental validation of leading end-to-end and hybrid approaches to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a clear framework for method selection and evaluation.

Architectural Paradigms: End-to-End vs. Hybrid Approaches

Deep learning methods for RNA structure prediction can be broadly categorized by their architectural philosophy and integration of prior knowledge. The distinction between these paradigms has significant implications for performance, data requirements, and generalizability.

Fully End-to-End Deep Learning Architectures

End-to-end models represent the purest form of data-driven approaches, employing single, unified neural networks that directly map input sequences to structural outputs. These architectures typically leverage very deep neural networks, often based on transformer or convolutional architectures, and minimize the incorporation of explicit biological knowledge in favor of learning patterns directly from data [23].

RhoFold+ exemplifies this approach for RNA 3D structure prediction. It functions as a fully automated, differentiable pipeline that begins with RNA sequence inputs and directly produces all-atom 3D models [3]. Its architecture integrates a large RNA language model (RNA-FM) pretrained on approximately 23.7 million RNA sequences to extract evolutionarily informed embeddings [3]. These embeddings are processed through a specialized transformer network (Rhoformer) and refined through multiple cycles before a geometry-aware structure module generates final atomic coordinates using an invariant point attention mechanism [3]. This comprehensive end-to-end approach demonstrates the capability of deep learning systems to manage the entire structure prediction pipeline without relying on external sampling or scoring modules.

Hybrid Deep Learning Architectures

Hybrid architectures strategically combine deep learning with established principles from biophysics, evolutionary biology, or thermodynamics. These approaches recognize that pure data-driven methods face challenges due to RNA's structural data scarcity, and seek to compensate by incorporating valuable inductive biases and physical constraints [20] [23].

BPfold represents this paradigm for RNA secondary structure prediction. It integrates thermodynamic energy calculations directly into its deep learning framework [20]. Specifically, BPfold employs a base pair motif library that enumerates the complete space of locally adjacent three-neighbor base pairs and records their thermodynamic energy through de novo modeling of tertiary structures [20]. The model's neural network incorporates a custom-designed "base pair attention block" that combines transformer and convolution layers to integrate information between the RNA sequence and the base pair motif energy [20]. This hybrid design allows BPfold to leverage the pattern recognition capabilities of deep learning while being grounded in the physical reality of RNA thermodynamics.

Another hybrid strategy incorporates evolutionary information through multiple sequence alignments (MSAs). Methods like DeepFoldRNA and trRosettaRNA utilize transformer networks to convert constructed MSAs and predicted secondary structures into various geometrical constraints, which are then used to predict RNA 3D structures through energy minimization [3]. Even some end-to-end models like RhoFold+ incorporate hybrid elements by optionally using MSAs alongside their primary sequence-based approach [3].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Architectural Paradigms

| Architectural Feature | End-to-End Models | Hybrid Models |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Learn sequence-structure mapping directly from data | Integrate deep learning with biophysical/evolutionary principles |

| Data Requirements | Large datasets of sequences and structures | Can work with smaller datasets due to incorporated priors |

| Typical Architecture | Unified deep neural networks (transformers, CNNs) | Combination of neural networks with energy minimization, MSAs, or physical constraints |

| Interpretability | Lower; "black box" characteristics | Higher; incorporates understandable biological principles |

| Generalization | Can struggle with unseen RNA families without sufficient data | Often better generalization through physical constraints |

| Representative Examples | RhoFold+ (3D structure) [3] | BPfold (secondary structure) [20], DeepFoldRNA (3D structure) [3] |

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Comparison

Rigorous benchmarking is essential for evaluating the performance of RNA structure prediction algorithms. Standardized assessments on established datasets like RNA-Puzzles and CASP15 provide objective comparisons between methods, while cross-family validation tests generalization capabilities to unseen RNA families [3] [23].

Experimental Protocols and Evaluation Metrics

Comprehensive benchmarking requires carefully designed experimental protocols that assess both accuracy and generalizability. Standard practice involves retrospective comparisons on community-wide challenges like RNA-Puzzles, where predictions are compared against experimentally determined structures [3]. For these evaluations, models must be trained using non-overlapping data with respect to the test targets to prevent overfitting and ensure fair comparison [3].

Key metrics for evaluation include:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures the average distance between corresponding atoms in predicted and experimental structures after optimal superposition, with lower values indicating better accuracy [3].

- Template Modeling (TM) Score: A superposition-free metric that assesses global structural similarity, with scores ranging from 0-1 (higher values indicate better agreement) [3].

- Local Distance Difference Test (LDDT): A superposition-free score that evaluates local distance differences for all atoms in a model [3].

- F1 Score for Secondary Structure: For secondary structure prediction, the harmonic mean of precision and recall for base pair identification [20] [23].

To address the "generalization crisis" in the field, contemporary benchmarking increasingly employs cross-family and cross-type assessments, where models are tested on RNA families not represented in the training data [23]. This provides a more realistic measure of performance on truly novel RNAs. Additionally, time-censored benchmarks that exclude recently solved structures from training data help evaluate real-world applicability [3].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative comparisons reveal the relative strengths of different architectural approaches. On the challenging RNA-Puzzles benchmark for 3D structure prediction, the end-to-end model RhoFold+ achieved an average RMSD of 4.02 Ã…, significantly outperforming the second-best method (FARFAR2: 6.32 Ã…) [3]. RhoFold+ also attained an average TM score of 0.57, higher than other top performers (0.41-0.44) [3]. These results demonstrate the substantial accuracy improvements possible with modern deep learning architectures.

For secondary structure prediction, the hybrid approach BPfold has demonstrated superior generalizability in cross-family validation. In experiments on sequence-wise and family-wise datasets including ArchiveII (3966 RNAs) and Rfam12.3-14.10 (10,791 RNAs), BPfold maintained high accuracy across diverse RNA families compared to other learning-based and non-learning methods [20]. This suggests that incorporating thermodynamic priors helps maintain performance on out-of-distribution RNAs.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of RNA Structure Prediction Methods

| Method | Architecture Type | Prediction Target | Key Performance Metrics | Generalization Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RhoFold+ [3] | End-to-end | 3D structure | Avg. RMSD: 4.02 Å on RNA-Puzzles; Avg. TM-score: 0.57 | No significant correlation between performance and training-test similarity (R²=0.23 for TM-score) |

| BPfold [20] | Hybrid | Secondary structure | Superior accuracy on cross-family benchmarks; maintains performance on out-of-distribution RNAs | Excellent generalizability to unseen RNA families due to thermodynamic integration |

| RNA-LLMs [11] | Hybrid (with evolutionary info) | Secondary structure | Performance varies significantly; two LLMs clearly outperform others in benchmark | Significant challenges in low-homology scenarios |

| FARFAR2 [3] | Non-deep learning | 3D structure | Avg. RMSD: 6.32 Ã… on RNA-Puzzles (second best) | Traditional sampling approach, less data-dependent |

Critical Analysis of Benchmarking Results

While quantitative metrics provide essential performance measures, several nuanced factors influence their interpretation:

Training Data Dependencies: The relationship between training data and performance differs significantly between architectures. For RhoFold+, analysis revealed no significant correlation between model performance (measured by TM-score and LDDT) and sequence similarity between test and training data (R² values of 0.23 and 0.11 respectively) [3]. This suggests better generalization capabilities compared to methods more dependent on homology.

Complexity-Performance Trade-offs: Hybrid models like BPfold demonstrate that incorporating physical priors can enhance generalization, particularly valuable given the scarcity of RNA structural data [20]. This approach mitigates the data insufficiency problem that plagues purely data-driven methods.

Computation Time Considerations: While comprehensive runtime comparisons are not always available, MSA-based methods typically require extensive database searches that significantly increase computation time [3]. Single-sequence methods offer faster prediction but often at the cost of reduced accuracy, though next-generation methods aim to improve both speed and accuracy [3].

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Implementing and evaluating deep learning methods for RNA structure prediction requires specific computational resources and benchmark datasets. The following tools and resources represent essential components of the modern RNA bioinformatics toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource/Tool | Type | Function/Application | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| RhoFold+ [3] | End-to-end prediction tool | Predicts 3D structures of single-chain RNAs from sequences | Method described in literature; availability of code varies |

| BPfold [20] | Hybrid prediction tool | Predicts RNA secondary structures using base pair motif energy | Method described in literature |

| RNA-FM [3] | Pre-trained language model | Provides evolutionarily informed embeddings for RNA sequences | Used within RhoFold+ pipeline |

| BGSU Representative Sets [3] | Curated dataset | Non-redundant RNA structure datasets for training and benchmarking | Publicly available from BGSU |

| RNA-Puzzles [3] | Benchmark dataset | Standardized targets for evaluating 3D structure prediction methods | Publicly available at rnapuzzles.org |

| ArchiveII [20] | Benchmark dataset | Contains 3966 RNAs for secondary structure evaluation | Publicly available |

| Rfam [23] | Database | RNA family annotations and alignments for evolutionary analysis | Publicly available |

Architectural Workflows and Methodologies

Understanding the operational flow of different architectural approaches provides insight into their relative strengths and implementation complexities. The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows for representative end-to-end and hybrid methods.

End-to-End Architecture: RhoFold+ Workflow

RhoFold+ End-to-End Prediction Pipeline

This workflow illustrates the fully automated, differentiable nature of RhoFold+. The process begins with RNA sequence input, which undergoes parallel processing through a pretrained language model (RNA-FM) and optional multiple sequence alignment analysis [3]. These features are integrated and refined through the specialized Rhoformer transformer network across multiple cycles [3]. Finally, a geometry-aware structure module with invariant point attention generates the complete all-atom 3D structure without requiring external sampling or scoring [3].

Hybrid Architecture: BPfold Workflow

BPfold Hybrid Prediction Workflow

BPfold's hybrid approach combines deep learning with thermodynamic principles. The system begins by processing the input RNA sequence through two parallel paths: generating base pair motif energy maps from a precomputed library of three-neighbor base pair motifs, and extracting sequence features [20]. These information streams are integrated through a custom-designed base pair attention block that applies an attention mechanism to both the RNA sequence features and the thermodynamic energy prior [20]. The combined features are processed through an architecture combining transformer and convolution layers before producing the final secondary structure prediction [20].

The deep learning revolution has fundamentally transformed RNA structure prediction, with both end-to-end and hybrid architectures demonstrating significant advantages over previous methodologies. Fully end-to-end models like RhoFold+ have achieved remarkable accuracy in 3D structure prediction, outperforming traditional methods and even human expert groups in standardized benchmarks [3]. Meanwhile, hybrid approaches like BPfold have shown superior generalizability to unseen RNA families by integrating physical priors with data-driven learning [20].

For researchers and drug development professionals, method selection involves important trade-offs. End-to-end architectures offer maximum convenience and often state-of-the-art performance on within-distribution predictions, while hybrid approaches provide better interpretability and generalization, which is particularly valuable for novel RNA targets with limited homologs [20] [23]. As the field addresses ongoing challenges including accurate prediction of pseudoknots, modeling of dynamic structural ensembles, and incorporation of chemical modifications, both architectural paradigms will continue to evolve [23].

The establishment of stricter benchmarking protocols and homology-aware evaluation represents crucial progress in the field [23]. Future advancements will likely incorporate increasingly sophisticated physical constraints while leveraging larger and more diverse training datasets. As these methods mature, they will enhance our fundamental understanding of RNA biology and accelerate the development of RNA-targeted therapeutics for human disease.

The Rise of RNA-Specific Large Language Models (LLMs)

The rapid expansion of unannotated RNA sequence data has created an unprecedented opportunity to apply artificial intelligence to decipher the language of RNA biology. Inspired by the revolutionary success of large language models (LLMs) in natural language processing and protein research, computational biologists have recently developed a new class of RNA-specific large language models (RNA-LLMs) [24]. These models leverage self-supervised learning on millions of RNA sequences to learn semantically rich numerical representations that capture intricate patterns linking sequence to structure and function [25]. Unlike traditional computational methods that rely on thermodynamic parameters or multiple sequence alignments, RNA-LLMs can potentially uncover complex, long-range dependencies within RNA sequences through the transformer architecture's self-attention mechanism [7]. This technological advancement represents a paradigm shift in computational RNA biology, offering new avenues for understanding RNA structure-function relationships and accelerating therapeutic development.

The significance of RNA-LLMs extends beyond academic curiosity into practical applications in drug discovery and development. With RNA becoming an increasingly attractive therapeutic target, accurately predicting RNA secondary and tertiary structures is crucial for understanding function and designing targeted interventions [26]. However, existing RNA language models vary considerably in their architectural designs, training datasets, and performance characteristics, creating a need for systematic benchmarking to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting appropriate models for specific applications. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of leading RNA-LLMs, focusing on their performance in structure prediction tasks within the broader context of benchmarking methodologies for RNA structure prediction algorithms.

Comparative Analysis of Leading RNA Language Models

Recent RNA-LLMs share a common foundation in the transformer architecture but employ distinct strategies to capture RNA-specific properties. Most models utilize a BERT-style framework pre-trained using masked language modeling (MLM), where the model learns to predict randomly masked nucleotides in sequences [25]. However, key architectural differences and training variations distinguish these models in their approach to capturing structural information.

ERNIE-RNA introduces a fundamental innovation through base-pairing-informed attention bias, incorporating canonical base-pairing rules (AU, CG, and GU pairs) directly into the self-attention mechanism [7]. This structural enhancement allows the model to learn RNA structural patterns through self-supervised learning without relying on potentially inaccurate predicted structures. The model comprises 12 transformer blocks with 12 attention heads each, resulting in approximately 86 million parameters trained on 20.4 million filtered RNA sequences from RNAcentral [7].

In contrast, RiNALMo prioritizes scale and modern architectural techniques, establishing itself as the largest RNA language model to date with 650 million parameters [26]. It incorporates rotary positional embedding (RoPE), SwiGLU activation functions, and FlashAttention-2 for computational efficiency. Pre-trained on 36 million non-coding RNA sequences from multiple databases, RiNALMo demonstrates exceptional capability in clustering RNA families in its embedding space, suggesting strong capture of structural and functional similarities [26].

Other notable models include RNA-FM, a pioneering model with 100 million parameters trained on 23.7 million non-coding RNAs, and RNA-MSM, which uniquely incorporates evolutionary information through multiple sequence alignment, though this requires computationally expensive homology searches [25]. RNABERT incorporates Structure Alignment Learning during pre-training based on Rfam seed alignments, while RNAErnie employs motif-aware pre-training with motif-level random masking [25].

Performance Comparison on Structure Prediction Tasks

Comprehensive benchmarking reveals significant performance variations among RNA-LLMs for secondary structure prediction. A unified evaluation framework assessing multiple models with the same downstream prediction architecture and datasets shows that models excelling in structure prediction often underperform in functional classification, and vice versa [27].

In rigorous testing across benchmarks of increasing generalization difficulty, two models—ERNIE-RNA and RiNALMo—consistently outperform others [25] [11]. Both models demonstrate remarkable capability in zero-shot secondary structure prediction, with ERNIE-RNA's attention maps achieving an F1-score of up to 0.55 without fine-tuning [7]. When fine-tuned, these models achieve state-of-the-art performance on various downstream tasks, including RNA structure and function predictions [7] [26].

Notably, RiNALMo shows exceptional generalization capability on secondary structure prediction for RNA families not encountered during training, overcoming a critical limitation of many deep learning methods that struggle with unseen families [26]. This generalization ability is visually evident in UMAP projections of model embeddings, where RiNALMo and ERNIE-RNA show clear separation of different RNA families compared to the overlapping clusters of other models like RNABERT [25].

Table 1: Architectural Specifications of Major RNA Language Models

| Model | Parameters | Training Sequences | Embedding Dimension | Key Architectural Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERNIE-RNA | 86 million | 20.4 million | 768 | Base-pairing informed attention bias |

| RiNALMo | 650 million | 36 million | 1280 | Rotary embedding, SwiGLU, FlashAttention-2 |

| RNA-FM | ~100 million | 23.7 million | 640 | Standard BERT architecture |

| RNA-MSM | ~96 million | 3.1 million | 768 | MSA-inspired transformer |

| RNABERT | 509,896 | 76,237 | 120 | Structure alignment learning |

| RNAErnie | ~105 million | ~23 million | 768 | Motif-aware masking |

Table 2: Performance Comparison on Secondary Structure Prediction

| Model | Intra-Family Accuracy | Inter-Family Generalization | Zero-Shot Capability |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERNIE-RNA | State-of-the-art | Strong | F1-score up to 0.55 |

| RiNALMo | State-of-the-art | Exceptional | Demonstrated |

| RNA-FM | High | Moderate | Limited |

| RNA-MSM | High with MSA | Limited without MSA | Not reported |

| RNABERT | Moderate | Limited | Limited |

Benchmarking Frameworks and Experimental Protocols

Standardized Evaluation Methodologies

The emergence of RNA-LLMs has necessitated robust benchmarking frameworks to enable fair model comparisons. Traditional evaluations often suffered from inconsistent experimental setups, making direct model comparisons challenging. Recent initiatives have established standardized benchmarking frameworks that address these limitations through consistent architectural modules and carefully curated datasets [28].

The RNAscope benchmark represents a comprehensive evaluation framework comprising 1,253 experiments spanning diverse subtasks of varying complexity, including structure prediction, interaction classification, and function characterization [28]. This systematic approach enables researchers to assess model generalization across RNA families, target contexts, and environmental features. Similarly, other benchmarking efforts have established curated datasets with increasing generalization difficulty, from intra-family to cross-family predictions, allowing for nuanced assessment of model capabilities [25] [11].

These benchmarks adhere to rigorous practices for bias-free evaluations, including homology-aware dataset partitioning to prevent data leakage and ensure proper assessment of generalization capabilities [25]. The datasets typically include multiple RNA families such as 5S RNA, tRNA, tmRNA, RNaseP, and SRP, enabling assessment of performance across diverse structural classes.

Experimental Workflow for Model Assessment

A standardized experimental workflow has emerged for benchmarking RNA-LLMs, particularly for secondary structure prediction tasks. The process typically begins with embedding generation, where each nucleotide in RNA sequences is converted to a numerical vector using the pre-trained RNA-LLMs [25]. These embeddings then feed into a consistent downstream prediction architecture—typically a deep neural network with convolutional or recurrent layers—that is identical across all compared models [25] [11]. This approach ensures that performance differences are attributable to the quality of the embeddings rather than variations in the prediction architecture.

The evaluation employs multiple datasets with varying difficulty levels, from benchmark datasets like ArchiveII to more challenging low-homology scenarios [11]. Performance is measured using standard metrics including F1-score, precision, recall, and Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) for structure prediction, while function-related tasks may use accuracy and area under the curve (AUC) metrics [28].

Diagram 1: RNA-LLM Benchmarking Workflow - This diagram illustrates the standardized experimental workflow for evaluating RNA language models on structure prediction tasks.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools