Benchmarking RNA-seq Analysis Workflows: A Comprehensive Guide for Reliable Transcriptomics

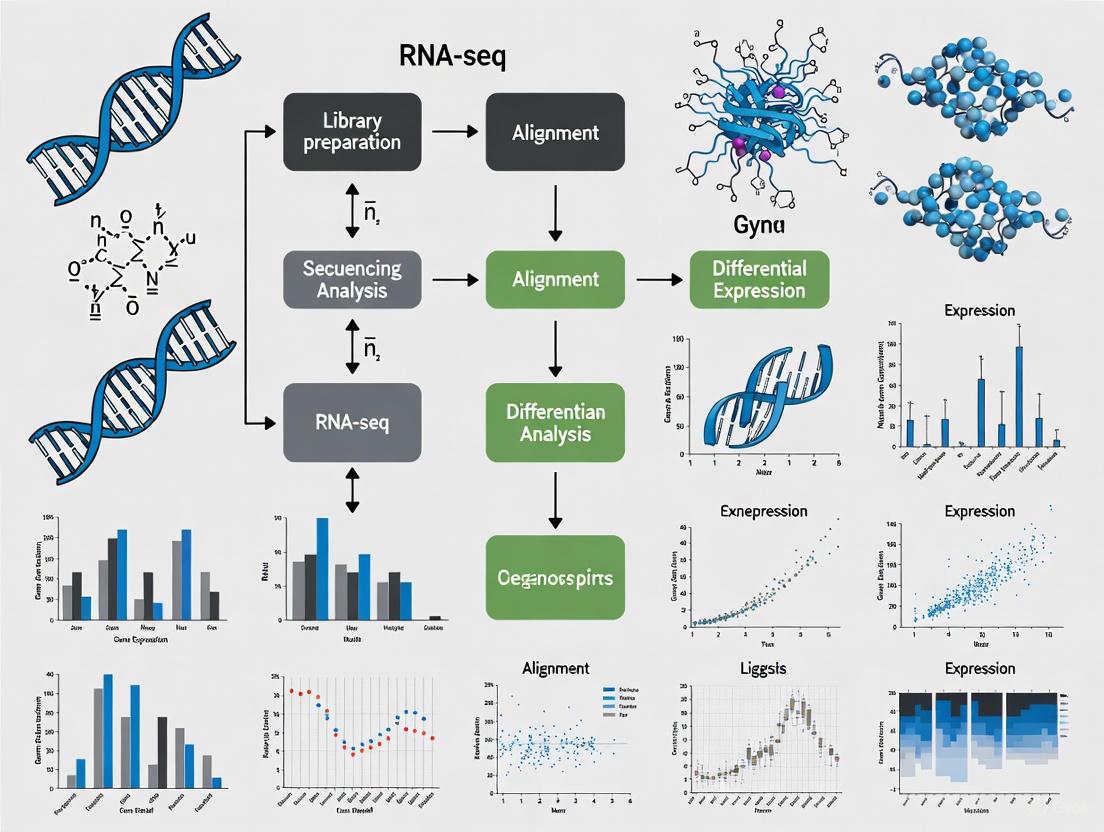

RNA sequencing is a foundational tool in modern biology and drug development, yet the lack of a single standard analysis pipeline presents a significant challenge.

Benchmarking RNA-seq Analysis Workflows: A Comprehensive Guide for Reliable Transcriptomics

Abstract

RNA sequencing is a foundational tool in modern biology and drug development, yet the lack of a single standard analysis pipeline presents a significant challenge. This article synthesizes findings from large-scale benchmarking studies to provide a clear roadmap for researchers. We explore the impact of experimental design and quality control, compare the performance of popular tools for alignment, quantification, and differential expression, offer strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing workflows for specific organisms, and outline best practices for validating results to ensure robust, reproducible biological insights.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles and Experimental Design for Robust RNA-seq

In the realm of transcriptomics, the power of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) to answer complex biological questions is entirely dependent on the initial experimental setup. A meticulously planned experiment is the foundation for ensuring that conclusions are biologically sound and statistically robust [1]. For researchers engaged in benchmarking RNA-seq analysis workflows, understanding the interplay between library preparation, replication, and sequencing depth is paramount. These initial choices determine the quality and type of data generated, thereby influencing the performance and outcome of downstream analytical pipelines. This guide provides a comparative assessment of key experimental design decisions, framing them within the context of generating reliable data for workflow benchmarking and drug development research.

Library Preparation Methods: A Comparative Guide

The choice of library preparation method dictates the nature of the information that can be extracted from an RNA-seq experiment. The main strategies can be broadly categorized into whole transcriptome (WTS) and 3' mRNA sequencing (3' mRNA-Seq), each with distinct advantages and trade-offs [1].

Whole Transcriptome vs. 3' mRNA-Seq

Whole Transcriptome Sequencing (WTS) provides a global view of the transcriptome. In this method, cDNA synthesis is initiated with random primers, distributing sequencing reads across the entire length of transcripts. This requires effective removal of abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA) prior to library preparation, either through poly(A) selection or rRNA depletion [1].

In contrast, 3' mRNA-Seq (e.g., QuantSeq) streamlines the process by using an initial oligo(dT) priming step that inherently selects for polyadenylated RNAs. This results in sequencing reads localized to the 3' end of transcripts, which is sufficient for gene expression quantification [1].

The decision between these methods should be guided by the research aims, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Choosing Between Whole Transcriptome and 3' mRNA-Seq Methods

| Feature | Whole Transcriptome Sequencing (WTS) | 3' mRNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Global transcriptome view; alternative splicing, novel isoforms, fusion genes [1] | Accurate, cost-effective gene expression quantification [1] |

| RNA Types Interrogated | Coding and non-coding RNAs [1] | Polyadenylated mRNAs [1] |

| Workflow Complexity | More complex; requires rRNA depletion or poly(A) selection [1] | Streamlined; fewer steps [1] |

| Data Analysis | More complex; requires alignment, normalization, and transcript concentration estimation [1] | Simplified; direct read counting without coverage normalization [1] |

| Required Sequencing Depth | Higher (e.g., 30-60 million reads) [2] | Lower (e.g., 5-25 million reads) [1] [2] |

| Ideal for Challenging Samples | Samples where the poly(A) tail is absent or degraded (e.g., prokaryotic RNA) [1] | Degraded RNA and FFPE samples due to robustness [1] |

Comparison of Specific Library Prep Kits

Beyond the broad category choice, the performance of specific commercial kits can vary. A 2022 study compared three commercially available kits for short-read sequencing: the traditional method (TruSeq), and two full-length double-stranded cDNA methods (SMARTer and TeloPrime) [3] [4].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Specific RNA-seq Library Prep Kits

| Metric | TruSeq (Traditional) | SMARTer (Full-length) | TeloPrime (Full-length) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Detected Expressed Genes | High | Similar to TruSeq | Fewer (approx. half of TruSeq) [3] |

| Correlation of Expression with TruSeq | Benchmark | Strong (R = 0.88-0.91) [3] | Relatively Low (R = 0.66-0.76) [3] |

| Performance with Long Transcripts | Accurate representation | Underestimates expression [3] | Underestimates expression [3] |

| Coverage Uniformity | Good | Most uniform across gene body [3] | Poor; biased towards 5' end (TSS) [3] |

| Genomic DNA Amplification | Low | Higher, suggesting nonspecific amplification [3] | Low |

| Number of Detected Splicing Events | Highest (~2x SMARTer, ~3x TeloPrime) [3] | Intermediate | Lowest [3] |

The study concluded that for short-read sequencing, the traditional TruSeq method held relative advantages for comprehensive transcriptome analysis, including quantification and splicing analysis [3] [4]. However, TeloPrime offered superior coverage at the transcription start site (TSS), which can be valuable for specific research questions [3].

Workflow Diagram: Library Preparation Selection

The following diagram summarizes the decision-making process for selecting an appropriate RNA-seq library preparation method based on research goals.

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for RNA-seq library prep.

The Interplay of Replicates and Sequencing Depth

Once a library preparation method is chosen, determining the appropriate number of biological replicates and the depth of sequencing is critical for statistical power.

The Critical Role of Biological Replicates

Biological replicates—where different biological samples are used for the same condition—are essential for measuring the natural biological variation within a population [5]. This variation is typically much larger than technical variation, making biological replicates far more important than technical replicates for RNA-seq experiments [5].

A landmark study using 48 biological replicates per condition in yeast demonstrated the profound impact of replicate number on the detection of differentially expressed (DE) genes [6]. With only three replicates, most tools identified only 20–40% of the DE genes found using the full set of 42 clean replicates. This sensitivity rose to over 85% for genes with large expression changes (>4-fold), but to achieve >85% sensitivity for all DE genes regardless of fold change required more than 20 biological replicates [6]. The study concluded that for future experiments, at least six biological replicates should be used, rising to at least 12 when it is important to identify DE genes for all fold changes [6].

Sequencing Depth Guidelines

Sequencing depth, or the number of reads per sample, must be balanced against the number of replicates, as both factors influence cost and statistical power.

Table 3: Recommended Sequencing Depth for Different RNA-seq Applications

| Application | Recommended Read Depth (Million Reads per Sample) | Read Type Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Profiling (Snapshot) | 5 - 25 million [2] [7] | Short single-read (50-75 bp) [2] |

| Global Gene Expression & Some Splicing | 30 - 60 million [2] [7] [5] | Paired-end (e.g., 2x75 bp or 2x100 bp) [2] |

| In-depth View/Novel Transcript Assembly | 100 - 200 million [2] | Longer paired-end reads [2] |

| Isoform-level Differential Expression | At least 30 million (known isoforms); >60 million (novel isoforms) [5] | Paired-end; longer is better [5] |

| 3' mRNA-Seq (QuantSeq) | 1 - 5 million [1] | Sufficient for 3' end counting |

Replicates vs. Depth: A Strategic Balance

Crucially, for standard gene-level differential expression analysis, increasing the number of biological replicates provides a greater boost in statistical power than increasing sequencing depth per sample [5]. A methodology experiment demonstrated that, at a fixed depth of 10 million reads, increasing replicates from 2 to 6 resulted in a higher gain of detected genes and power than increasing reads from 10 million to 30 million with only 2 replicates [7] [5]. Therefore, the prevailing best practice is to prioritize spending on more biological replicates over achieving higher sequencing depth, provided a minimum depth threshold is met for the application [5].

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between these factors and their impact on experimental outcomes.

Diagram 2: How experimental factors influence outcomes.

Application-Driven Experimental Design

The optimal experimental design is ultimately dictated by the biological question. Furthermore, the choice between bulk and single-cell RNA-seq represents a fundamental strategic decision.

Bulk RNA-seq vs. Single-Cell RNA-seq

Bulk RNA-seq provides a population-averaged gene expression readout from a pool of cells. It is a well-established, cost-effective method ideal for differential gene expression analysis in large cohorts, tissue-level transcriptomics, and identifying novel transcripts or splicing events [8].

Single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) profiles the transcriptome of individual cells. This resolution is essential for unraveling cellular heterogeneity, identifying rare cell types, reconstructing developmental lineages, and understanding cell-specific responses to disease or treatment [8].

Table 4: Comparison of Bulk and Single-Cell RNA-seq Approaches

| Aspect | Bulk RNA-seq | Single-Cell RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population-average [8] | Single-cell [8] |

| Key Applications | Differential expression, biomarker discovery, pathway analysis [8] | Cell type/state identification, heterogeneity, lineage tracing [8] |

| Cost per Sample | Lower [8] | Higher [8] |

| Sample Preparation | RNA extraction from tissue/cell pellet [8] | Generation of viable single-cell suspension [8] |

| Data Complexity | Lower; more straightforward analysis [8] | Higher; requires specialized analysis [8] |

| Detection of Rare Cell Types | Masks rare cell types [8] | Reveals rare and low-abundance cell types [8] |

Practical Considerations and Best Practices

- Avoiding Confounding and Batch Effects: A confounded experiment occurs when the effect of the primary variable of interest (e.g., treatment) cannot be distinguished from another source of variation (e.g., sex). To avoid this, ensure subjects in each condition are balanced for sex, age, and litter [5]. Batch effects—systematic technical variations from processing samples on different days or by different people—can be a significant issue. The best practice is to avoid confounding by batch by splitting replicates of all sample groups across processing batches [5].

- Analysis Tool Selection: The choice of differential expression tool is also influenced by replicate number. With fewer than 12 replicates,

edgeRandDESeq2offer a superior combination of true positive and false positive performance. For higher replicate numbers, where minimizing false positives is more critical,DESeqmarginally outperforms other tools [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Essential Reagents and Kits for RNA-seq Experimental Workflows

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| TruSeq Stranded mRNA Kit | Traditional whole transcriptome library prep using poly(A) selection and random priming [3]. | Global transcriptome studies requiring isoform and splicing data [3]. |

| Lexogen QuantSeq Kit | 3' mRNA-Seq library prep for focused gene expression quantification [1]. | High-throughput, cost-effective DGE studies, especially with FFPE samples [1]. |

| SMARTer Stranded RNA-Seq Kit | Full-length double-stranded cDNA library prep using template-switching [3]. | Whole transcriptome analysis from low-input samples; requires caution for gDNA contamination [3]. |

| TeloPrime Full-Length cDNA Kit | Full-length double-stranded cDNA prep using cap-specific linker ligation [3]. | Studies focused on precise mapping of Transcription Start Sites (TSS) [3]. |

| rRNA Depletion Reagents | Removal of ribosomal RNA to enrich for other RNA species (e.g., non-coding RNAs). | Whole transcriptome sequencing of non-polyadenylated RNAs [1]. |

| DESeq2 / edgeR | Statistical software packages for differential expression analysis from read count data [6]. | Identifying significantly differentially expressed genes between conditions [6]. |

In the realm of transcriptomics, particularly for applications in drug discovery and clinical diagnostics, the reliability of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data is fundamentally dependent on the quality of the input RNA. High-quality RNA is a prerequisite for ensuring the accuracy, reproducibility, and biological validity of downstream analyses, from differential expression profiling to biomarker discovery. Recent large-scale consortium studies have systematically demonstrated that variations in RNA sample quality contribute significantly to inter-laboratory discrepancies in RNA-seq results, potentially confounding the detection of biologically and clinically relevant signals [9]. This guide objectively compares the performance of established and emerging RNA quality assessment methodologies, providing a structured framework for researchers to implement robust quality control protocols within their RNA-seq workflows.

The Critical Impact of RNA Quality on RNA-Seq Outcomes

The integrity and purity of RNA samples are not merely preliminary checkpoints but are deeply intertwined with the ultimate informational content of a sequencing experiment.

The Subtle Differential Expression Challenge

The transition of RNA-seq into clinical diagnostics often requires the detection of subtle differential expression—minor but biologically significant changes in gene expression between different disease subtypes or stages. A 2024 multi-center benchmarking study, which analyzed data from 45 laboratories using Quartet and MAQC reference materials, revealed that inferior RNA quality directly compromises the ability to detect these subtle differences. The study reported that inter-laboratory variation was markedly greater when analyzing samples with small intrinsic biological differences (Quartet samples) compared to those with large differences (MAQC samples) [9]. This underscores that quality assessments based solely on samples with large expression differences may not ensure performance in more challenging, clinically relevant scenarios.

RNA quality is a primary source of technical variation that can obscure biological signals. The same multi-center study identified that experimental factors, including mRNA enrichment methods and library construction strandedness, are major contributors to variation in gene expression measurements [9]. Degraded RNA or samples contaminated with genomic DNA or salts can lead to:

- Biased coverage: Incomplete transcript representation, particularly a loss of signal at the 5' or 3' ends of transcripts.

- Inaccurate quantification: Over- or under-estimation of transcript abundance.

- Reduced sequencing efficiency: A higher proportion of unusable reads, increasing sequencing costs.

Quantitative Metrics for RNA Quality Control

A multi-faceted approach to quality control, leveraging complementary metrics, is essential for a comprehensive assessment of RNA sample integrity. The table below summarizes the core parameters and their interpretation.

Table 1: Key Metrics for RNA Quality Assessment

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Ideal Value/Range | Indicates | Method/Tool |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity | Concentration | Varies by application | Sufficient RNA input for library prep | Spectrophotometry, Fluorometry [10] [11] |

| Purity | A260/A280 ratio | 1.8–2.2 [11] | Pure RNA (low protein contamination) | Spectrophotometry (e.g., NanoDrop) [10] [11] |

| A260/A230 ratio | >1.8 [11] | Pure RNA (low salt/organic contamination) | Spectrophotometry (e.g., NanoDrop) [10] [11] | |

| Integrity | RNA Integrity Number (RIN) | 1 (degraded) to 10 (intact) [12] | Overall RNA integrity | Automated Electrophoresis (e.g., Bioanalyzer) [12] |

| RNA Quality Number (RQN) | 1 (degraded) to 10 (intact) [12] | Overall RNA integrity | Automated Electrophoresis (e.g., Fragment Analyzer) [12] | |

| 28S:18S Ribosomal Ratio | ~2:1 (Mammalian) [10] | High-quality total RNA | Agarose Gel Electrophoresis [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Key QC Methods

Protocol 1: UV Spectrophotometry for RNA Purity and Quantity

- Instrument Calibration: Blank the spectrophotometer using the same buffer in which the RNA is dissolved (e.g., nuclease-free water or TE buffer) [11].

- Sample Measurement: Apply 1-2 µL of the RNA sample to the measurement pedestal. The instrument will measure absorbance at 230nm, 260nm, 280nm, and 320nm [10].

- Data Analysis:

- Troubleshooting: A low A260/A280 ratio suggests protein contamination, often requiring re-purification. A low A260/A230 ratio indicates contamination by salts, carbohydrates, or guanidine [10] [11].

Protocol 2: Fluorometric RNA Quantification

- Standard Curve Preparation: Prepare a dilution series of an RNA standard of known concentration [10].

- Dye Incubation: Combine the fluorescent dye (e.g., from the QuantiFluor RNA System) with standards and unknown samples in a tube or plate and incubate as directed [10].

- Measurement: Place the tubes in a handheld fluorometer (e.g., Quantus) or read the plate in a microplate reader (e.g., GloMax Discover) [10].

- Concentration Calculation: Generate a standard curve by plotting fluorescence against the standard concentrations. Use the linear regression equation to determine the concentration of the unknown samples [10].

- Advantage: This method is significantly more sensitive than spectrophotometry, detecting RNA concentrations as low as 100 pg/µL, and is more specific for RNA if combined with a DNase treatment step [10].

Protocol 3: Integrity Analysis with Automated Electrophoresis

- Chip/Lab Card Preparation: Prime the specific chip (e.g., for Bioanalyzer) or lab card (e.g., for Fragment Analyzer) with the provided gel-dye mix [12].

- Sample Loading: Pipette a RNA marker into appropriate wells, followed by your RNA samples. The system typically requires only 1 µL of sample at concentrations as low as 50 pg/µL for the most sensitive systems [12].

- Run and Analyze: Start the electrophoresis run. The associated software will automatically separate the RNA, detect the ribosomal bands, and calculate an integrity score (RIN, RQN, or RINe) [12].

- Interpretation: A high score (e.g., RIN > 8) indicates intact RNA, characterized by sharp ribosomal peaks and a flat baseline. A low score indicates degradation, seen as a smear of low-molecular-weight RNA and a diminished ribosomal ratio [12].

A Structured Workflow for RNA Quality Control

Integrating the various assessment methods into a coherent workflow maximizes efficiency and ensures only high-quality samples proceed to costly RNA-seq library preparation. The following diagram illustrates a recommended decision pathway.

Diagram 1: RNA Quality Control Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Systems

The following table catalogs key solutions and instruments that form the backbone of a reliable RNA QC pipeline.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for RNA Quality Control

| Item Name | Function/Benchmarking Purpose | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Spike-In Controls (ERCC) | Act as built-in truth for assessing technical performance, dynamic range, and quantification accuracy in RNA-seq [9] [13]. | Synthetic RNAs at known concentrations; enable measurement of assay sensitivity and reproducibility across sites [9]. |

| Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer | Provides automated electrophoresis for RNA integrity and quantification. | Generates an RNA Integrity Number (RIN); requires RNA 6000 Nano or Pico kits [12]. |

| Agilent Fragment Analyzer | Capillary electrophoresis for consistent assessment of total RNA quality, quantity, and size. | Provides an RNA Quality Number (RQN); offers high resolution for complex samples [12]. |

| Agilent TapeStation Systems | Efficient and simple DNA and RNA sample QC for higher-throughput labs. | Provides RINe (RIN equivalent) scores; uses pre-packaged ScreenTape assays [12]. |

| Fluorometric Kits (e.g., QuantiFluor) | Highly sensitive and specific quantification of RNA concentration, especially for low-abundance samples. | Detects as little as 100pg/µL RNA; more accurate than absorbance for low-concentration samples [10]. |

| Spectrophotometers (e.g., NanoDrop) | Rapid assessment of RNA concentration and purity from minimal sample volume. | Requires only 0.5–2µL of sample; provides A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios in seconds [10]. |

Informing Robust RNA-Seq Benchmarking

The rigorous application of the QC methods described above is a foundational element of any benchmarking study for RNA-seq workflows.

Pre-sequencing Sample Qualification

Benchmarking studies must document the quality metrics of all input RNA samples. The SEQC/MAQC consortium studies set a precedent by using well-characterized reference RNA samples, which allowed for an objective assessment of RNA-seq performance across platforms and laboratories [13]. Including RNA integrity scores (e.g., RIN) and purity ratios in published methods allows for the retrospective analysis of how input RNA quality influences consensus results and inter-site variability [9] [13].

Post-sequencing Quality Metrics

Computational tools like RNA-SeQC provide critical post-sequencing metrics that reflect the initial RNA sample quality [14]. These include:

- Alignment and rRNA content: High rRNA reads can indicate ineffective rRNA depletion during library prep, sometimes linked to RNA degradation.

- Coverage uniformity: 3'/5' bias in transcript coverage is a hallmark of degraded RNA.

- Correlation with reference profiles: Low correlation between replicates or with a gold-standard reference (e.g., TaqMan data) can often be traced back to disparities in initial RNA integrity between samples [9] [14].

Systematic quality control, from the initial RNA isolation to the final computational output, is the non-negotiable foundation for generating reliable and reproducible RNA-seq data. By adopting the multi-parameter assessment and structured workflow outlined in this guide, researchers and drug development professionals can make informed decisions on sample inclusion, optimize their experimental processes, and ultimately enhance the biological insights derived from their transcriptomic studies.

In RNA-sequencing research, a well-defined biological question serves as the foundational blueprint for the entire analytical process. The choice of workflow—from experimental design through computational analysis—directly determines the accuracy, reliability, and biological relevance of the findings. Recent large-scale benchmarking studies reveal that technical variations introduced at different stages of RNA-seq analysis can significantly impact results, particularly for subtle biological differences. This guide examines how specific research objectives should dictate workflow selection by synthesizing evidence from multi-platform benchmarking studies, providing researchers with a structured framework for aligning their analytical strategies with their scientific goals.

How Your Biological Question Dictates the Workflow

The fundamental questions driving RNA-seq experiments generally fall into distinct categories, each requiring specialized tools and approaches for optimal results. The table below outlines how different research aims correspond to specific workflow recommendations based on comprehensive benchmarking evidence.

Table 1: Aligning Biological Questions with Optimal RNA-seq Workflows

| Biological Question | Recommended Workflow Emphasis | Key Supporting Evidence | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subtle differential expression (e.g., disease subtypes) | mRNA enrichment, stranded protocols, stringent filtering | Quartet project: Inter-lab variation greatest for subtle differences [15] | SNR 19.8 for Quartet vs. 33.0 for MAQC samples; mRNA enrichment and strandedness are primary variation sources [15] |

| Transcript-level analysis (isoforms, splicing) | Long-read protocols (Nanopore/PacBio), transcript-level quantifiers | SG-NEx project: Long-reads better identify major isoforms and complex transcriptional events [16] | Long-read protocols resolve alternative isoforms that short-reads miss; Direct RNA-seq also provides modification data [16] |

| Species-specific analysis (non-model organisms) | Parameter optimization, tailored filtering thresholds | Fungal study: 288 pipelines tested; performance varies by species [17] | Default parameters often suboptimal; tailored workflows provide more accurate biological insights [17] |

| Routine differential expression (well-characterized models) | Alignment-free quantifiers (Salmon, Kallisto) with DESeq2/edgeR | Multi-protocol benchmarks: Salmon/Kallisto offer speed advantages with maintained accuracy [18] [19] | High correlation with qPCR (∼85% genes consistent); specific gene sets (small, few exons, low expression) require validation [19] |

The relationship between research goals and workflow components can be visualized as a decision pathway that ensures alignment between biological questions and analytical methods:

Experimental Protocols from Key Benchmarking Studies

The Quartet Project: Benchmarking Subtle Differential Expression

Study Design and Methodology

The Quartet project established a comprehensive framework for evaluating RNA-seq performance in detecting subtle expression differences, which are characteristic of clinically relevant sample groups such as different disease subtypes or stages. The experimental design incorporated multiple reference samples and ground truth datasets [15]:

- Reference Materials: Four Quartet RNA samples from B-lymphoblastoid cell lines with small biological differences, MAQC RNA samples with large biological differences, and defined mixture samples (3:1 and 1:3 ratios)

- Spike-in Controls: ERCC RNA controls with known concentrations spiked into specific samples

- Multi-laboratory Design: 45 independent laboratories employing distinct RNA-seq workflows

- Data Generation: 1080 RNA-seq libraries yielding over 120 billion reads (15.63 Tb)

- Analysis Pipeline Evaluation: 26 experimental processes and 140 bioinformatics pipelines assessed

Performance Metrics

The study employed multiple metrics to characterize RNA-seq performance: signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) based on principal component analysis, accuracy of absolute and relative gene expression measurements, and accuracy of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) based on reference datasets [15].

SG-NEx Project: Comprehensive Long-Read RNA-seq Benchmarking

Experimental Framework

The Singapore Nanopore Expression (SG-NEx) project generated a comprehensive resource for benchmarking transcript-level analysis across multiple sequencing platforms [16]:

- Cell Lines: Seven human cell lines (HCT116, HepG2, A549, MCF7, K562, HEYA8, H9) with multiple replicates

- Sequencing Protocols: Direct RNA, amplification-free direct cDNA, PCR-amplified cDNA (Nanopore), PacBio IsoSeq, and Illumina short-read sequencing

- Spike-in Controls: Sequin, ERCC, and SIRV spike-ins with known concentrations

- Extended Profiling: Transcriptome-wide m⁶A methylation profiling (m⁶ACE-seq)

- Data Scale: 139 libraries with average depth of 100.7 million long reads for core cell lines

Analytical Approach

The project implemented a community-curated nf-core pipeline for standardized data processing, enabling robust comparison of protocol performance for transcript identification, quantification, and modification detection [16].

Fungal RNA-seq Optimization Study

Methodology for Species-Specific Workflows

This research systematically evaluated 288 analysis pipelines to determine optimal approaches for non-human data, specifically focusing on plant pathogenic fungi [17]:

- Dataset Selection: RNA-seq data from major plant-pathogenic fungi across evolutionary spectrum

- Tool Comparison: Multiple tools evaluated at each processing stage - filtering/trimming, alignment, quantification, and differential expression

- Performance Validation: Additional validation using animal (mouse) and plant (poplar) datasets

- Evaluation Metrics: Performance assessed based on simulated data and biological plausibility of results

Comparative Performance Data Across Methodologies

Accuracy Metrics for Differential Expression Detection

The table below summarizes quantitative performance data from key benchmarking studies, providing researchers with comparative metrics for workflow selection.

Table 2: Performance Metrics Across RNA-seq Workflows and Applications

| Application Scenario | Workflow Components | Performance Metrics | Reference Standard |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subtle DE Detection | Stranded mRNA-seq with optimized filtering | SNR: 19.8 (Quartet) vs. 33.0 (MAQC) [15] | Quartet reference datasets |

| Transcript Quantification | Long-read direct RNA/cDNA protocols | Superior major isoform identification vs. short-reads [16] | PacBio IsoSeq, spike-in controls |

| Cross-Species Analysis | Parameter-optimized alignment/quantification | Significant improvement over default parameters [17] | Simulated data and biological validation |

| Gene-Level DE | Salmon/Kallisto + DESeq2 | ~85% concordance with qPCR fold-changes [19] | RT-qPCR expression data |

Benchmarking studies have identified key sources of technical variation that researchers must consider when designing their analysis workflows:

- Experimental Factors: mRNA enrichment protocols and library strandedness significantly impact inter-laboratory consistency, particularly for subtle differential expression [15]

- Bioinformatics Choices: Each step in the analytical pipeline - including read alignment, quantification methods, and normalization approaches - contributes to variation in results [15]

- Platform-Specific Biases: Long-read protocols demonstrate advantages for isoform resolution but have different throughput and coverage characteristics compared to short-read platforms [16]

- Species-Specific Considerations: Default parameters optimized for human data may perform suboptimally for other organisms, necessitating tailored approaches [17]

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Reference Materials for RNA-seq Workflows

| Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Quartet Reference Materials | Multi-omics reference materials for quality control | Detecting subtle differential expression; inter-laboratory standardization [15] |

| ERCC Spike-in Controls | Synthetic RNA controls with known concentrations | Assessing technical performance and quantification accuracy [15] |

| SIRV Spike-in Mixes | Complex spike-in controls with isoform variants | Evaluating transcript-level quantification performance [16] |

| MAQC Reference Samples | RNA samples with large biological differences | Benchmarking workflow performance for large expression differences [15] |

| Cell Line Panels | Well-characterized human cell lines (e.g., SG-NEx) | Protocol comparison and method development [16] |

The integration of evidence from major RNA-seq benchmarking studies demonstrates that effective workflow design requires precise alignment between biological questions and analytical methods. Researchers investigating subtle expression differences should prioritize stranded mRNA enrichment protocols and stringent filtering, while those focused on isoform diversity benefit from long-read sequencing technologies. For non-model organisms, parameter optimization emerges as a critical success factor. By leveraging the standardized protocols and reference materials described in this guide, researchers can design RNA-seq workflows that minimize technical variation and maximize biological relevance, ensuring that their analytical approach effectively addresses their fundamental scientific questions.

From Raw Reads to Results: A Tool-by-Tool Comparison of Analysis Pipelines

Quality control and adapter trimming represent the foundational first steps in any RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis workflow, directly influencing the reliability of all downstream results including gene expression quantification and differential expression analysis [20] [17]. Inadequate preprocessing can introduce technical artifacts that obscure true biological signals, particularly when detecting subtle differential expression with clinical relevance [15]. While numerous tools have been developed for these tasks, FastQC, Trimmomatic, and fastp have emerged as among the most widely utilized solutions, each employing distinct algorithmic approaches and offering different trade-offs between performance, functionality, and ease of use [20] [21].

This guide provides an objective comparison of these three tools within the context of benchmarking RNA-seq analysis workflows, synthesizing evidence from recent controlled studies to evaluate their performance characteristics, strengths, and limitations. We present quantitative data on processing speed, quality improvement, adapter removal efficiency, and computational resource utilization to inform tool selection by researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working with diverse experimental systems and resource environments.

FastQC: Quality Assessment Specialist

FastQC serves as a dedicated quality control tool that provides comprehensive visualization and assessment of raw sequencing data prior to any preprocessing operations [22]. It generates a modular report examining multiple quality metrics including per-base sequence quality, adapter contamination, overrepresented sequences, and GC content distribution. While FastQC excels at diagnostic assessment, it contains no built-in filtering or trimming capabilities, necessitating pairing with a dedicated processing tool like Trimmomatic or fastp for complete preprocessing workflows [22] [17].

Trimmomatic: Sequence-Matching Based Processing

Trimmomatic employs a traditional sequence-matching algorithm with global alignment and no gaps for adapter identification and removal [21] [23]. This approach uses predefined adapter libraries and performs thorough scanning of read sequences against these references. For quality trimming, Trimmomatic implements a sliding-window approach that examines read segments and trms based on average quality thresholds. A notable characteristic is Trimmomatic's complex parameter setup, which while offering flexibility, presents a steeper learning curve for novice users [17].

fastp: Overlapping Algorithm for Ultra-Fast Processing

As a more recently developed tool, fastp utilizes a sequence overlapping algorithm with mismatches for adapter detection and removal [21] [23]. A key innovation in fastp is its ability to automatically detect adapter sequences without prior specification, significantly simplifying user interaction [20]. The software is highly optimized for computational efficiency, employing techniques such as a one-gap-matching algorithm that reduces computational complexity from O(n²) to O(n) for certain operations [20]. Unlike Trimmomatic and FastQC which are often used together, fastp integrates both quality control assessment and preprocessing functions within a single tool, generating HTML reports that compare data before and after processing [20] [17].

Experimental Benchmarking: Methodologies and Protocols

Standardized Evaluation Frameworks

Recent comparative studies have employed rigorous experimental designs to evaluate preprocessing tools using diverse RNA-seq datasets. Typical benchmarking protocols involve processing standardized datasets with multiple tools using controlled parameters, then comparing output quality using predefined metrics [21] [17] [23]. One comprehensive study evaluated six trimming programs using poliovirus, SARS-CoV-2, and norovirus paired-read datasets sequenced on both Illumina iSeq and MiSeq platforms [21] [23]. The experimental workflow maintained consistent parameter thresholds for adapter identification and quality trimming across all tools to ensure fair comparisons, with performance assessed based on residual adapter content, read quality metrics, and impact on downstream assembly and variant calling [21].

Another large-scale RNA-seq benchmarking study, part of the Quartet project, analyzed performance across 45 laboratories using reference samples with spike-in controls to assess accuracy in detecting subtle differential expression patterns relevant to clinical diagnostics [15]. This real-world multi-center design provided insights into how preprocessing tools perform across varied experimental conditions and research environments.

Key Performance Metrics

Researchers typically employ multiple quantitative measures to evaluate preprocessing tool performance:

- Adapter Removal Efficiency: Percentage of adapter sequences successfully identified and removed from datasets [21] [23]

- Quality Improvement: Increase in Q20 and Q30 ratios (bases with quality scores ≥20 or ≥30) after processing [20] [17]

- Read Retention: Proportion of reads maintained after filtering and trimming procedures [21]

- Computational Efficiency: Processing speed and memory utilization, particularly important for large datasets [20]

- Downstream Impact: Effect on subsequent analysis steps including de novo assembly metrics and variant calling accuracy [21] [23]

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the typical experimental workflow for comparing preprocessing tools in RNA-seq benchmarking studies:

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparative performance metrics for FastQC, Trimmomatic, and fastp based on recent benchmarking studies

| Performance Metric | FastQC | Trimmomatic | fastp |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adapter Removal Efficiency | Not Applicable | Effectively removed adapters from all datasets [21] [23] | Retained detectable adapters (0.038-13.06%) across viral datasets [21] [23] |

| Quality Base Improvement (Q≥30) | Assessment Only | 93.15-96.7% quality bases in output [21] [23] | 93.15-96.7% quality bases in output; significantly enhanced Q20/Q30 ratios [21] [17] |

| Processing Speed | Fast quality reporting | Slower compared to fastp; no speed advantage [17] | Ultra-fast; highly optimized algorithms [20] [17] |

| Memory Efficiency | Moderate resource use | Standard resource consumption | Cloud-friendly; minimal resource requirements [20] |

| Ease of Use | Simple operation with visual reports | Complex parameter setup [17] | Simple defaults; automatic adapter detection [20] |

| Downstream Assembly Impact | Not Applicable | Improved N50 and maximum contig length [21] | Improved N50 and maximum contig length [21] |

Relationship Between Tool Features and Performance

The following diagram illustrates how different algorithmic approaches employed by each tool influence their performance characteristics:

Experimental Protocols and Reagent Solutions

Standardized Benchmarking Methodology

To ensure reproducible comparisons between preprocessing tools, researchers typically follow a standardized protocol:

Dataset Selection: Curate diverse RNA-seq datasets representing different organisms, sequencing platforms, and library preparation methods. Studies often include both synthetic spike-in controls (e.g., ERCC RNA controls) and biological samples to assess accuracy across different ground truth scenarios [15].

Parameter Standardization: Establish consistent parameter thresholds for adapter identification, quality trimming, and allowed mismatches across all tools being compared. For example, one study specified minimum read length of 50 bases and quality threshold of Q20 for all trimmers [21].

Quality Assessment: Apply multiple quality metrics to both raw and processed data, including FastQC reports, sequence quality scores, adapter contamination levels, and GC content distribution [21] [22].

Downstream Analysis Evaluation: Process trimmed reads through standardized alignment, assembly, and quantification pipelines to assess the impact of preprocessing choices on biologically relevant outcomes [21] [17].

Statistical Comparison: Employ appropriate statistical tests (e.g., Wilcoxon signed-rank test with Bonferroni correction) to determine significant differences in performance metrics between tools [21].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key experimental reagents and computational tools for RNA-seq preprocessing benchmarks

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application in Preprocessing Benchmarks |

|---|---|---|

| ERCC RNA Spike-In Controls | External RNA controls with defined concentrations | Provide ground truth for evaluating quantification accuracy after preprocessing [15] |

| Quartet Reference Materials | RNA reference materials from B-lymphoblastoid cell lines | Enable assessment of subtle differential expression detection following preprocessing [15] |

| Illumina Sequencing Platforms | Next-generation sequencing (iSeq, MiSeq, HiSeq) | Generate raw FASTQ data for preprocessing comparisons across platforms [21] |

| FastQC | Quality control assessment | Diagnostic evaluation of raw and processed read quality [22] |

| MultiQC | Aggregate multiple QC reports | Combine metrics from multiple samples and tools for comparative analysis [21] |

| SPAdes | De novo assembly | Evaluate impact of preprocessing on assembly metrics (N50, max contig length) [21] |

| SeqKit | FASTA/Q file manipulation | Calculate read statistics before and after preprocessing [21] |

Discussion and Practical Recommendations

Context-Dependent Tool Selection

The comparative analysis reveals that tool selection depends significantly on specific research contexts and constraints. For maximum adapter removal efficiency, particularly in viral sequencing studies, Trimmomatic's sequence-matching approach demonstrated superior performance in completely eliminating adapter sequences [21] [23]. However, for large-scale studies where processing speed and computational efficiency are paramount, fastp's optimized algorithms provide significant advantages with only minimal residual adapter retention [20] [17].

In studies focusing on detecting subtle differential expression with clinical relevance, comprehensive quality control using FastQC combined with rigorous trimming remains essential, as inter-laboratory variations in preprocessing can significantly impact downstream results [15]. The integrated reporting of fastp, which provides side-by-side comparison of pre- and post-processing quality metrics, offers particular benefits for cloud-based workflows and researchers seeking simplified operational pipelines [20].

Emerging Best Practices

Recent large-scale benchmarking studies suggest several evolving best practices for RNA-seq preprocessing:

Multi-Tool Quality Assessment: Employ both FastQC and integrated QC tools like fastp or MultiQC to obtain complementary perspectives on data quality [22] [17].

Parameter Optimization: Rather than relying on default parameters, optimize trimming stringency based on initial quality metrics and downstream analysis requirements [17].

Preservation of Read Length: Balance quality trimming with preservation of sufficient read length for downstream alignment and quantification, as excessively aggressive trimming can impair splice junction detection [21].

Pipeline Consistency: Maintain consistent preprocessing approaches across all samples within a study to minimize batch effects and technical variability [15].

As RNA-seq applications continue expanding into clinical diagnostics, rigorous benchmarking of preprocessing tools against relevant reference materials will remain essential for ensuring accurate and reproducible results, particularly when detecting subtle expression differences with potential diagnostic implications [15].

In the realm of transcriptomics, RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) has fundamentally transformed how researchers connect genomic information with phenotypic and physiological data, enabling unprecedented discovery in areas ranging from basic biology to drug development [24]. The alignment of sequenced reads to a reference genome is a foundational step in most RNA-Seq analysis pipelines, and its accuracy profoundly impacts all subsequent biological interpretations [25]. The choice of alignment tool can influence the detection of differentially expressed genes, the identification of novel splice variants, and the overall reliability of study conclusions.

While numerous alignment tools exist, STAR, HISAT2, and BWA represent three widely used mappers with distinct algorithmic approaches and design philosophies. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these tools within the broader context of benchmarking RNA-seq analysis workflows. We focus on their performance in handling the unique challenge of spliced alignment, where reads originating from mature messenger RNA (mRNA) must be mapped across intron-exon boundaries—a task that requires specialized, "splice-aware" algorithms [26] [27]. Our evaluation synthesizes findings from multiple independent studies to offer researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals evidence-based recommendations for their specific analytical needs.

Algorithmic Foundations and Design Philosophies

The performance differences between aligners stem from their underlying algorithms and data structures, which represent distinct solutions to the problem of efficiently mapping billions of short sequences.

STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) employs an uncompressed suffix array for indexing the reference genome. This design allows it to perform a fast, seed-based search for splice junctions. A key feature of STAR is its ability to detect splice junctions directly from the data by identifying reads that align contiguously to a single exon or discontinuously to two different exons [28] [25]. This makes it highly sensitive for discovering novel splicing events.

HISAT2 (Hierarchical Indexing for Spliced Alignment of Transcripts 2) utilizes a hierarchical graph Ferragina-Manzini (GFM) index. This complex indexing strategy partitions the genome into overlapping regions, creating a global index for the entire genome and numerous small local indexes. This architecture enables HISAT2 to efficiently manage the large memory footprint typically associated with aligning to a reference as complex as the human genome, while remaining fully splice-aware [24] [26].

BWA (Burrows-Wheeler Aligner), specifically its

memalgorithm, is primarily designed for DNA sequence alignment. It uses the Burrows-Wheeler Transform (BWT) and the FM-index, which are highly memory-efficient [24] [28]. However, BWA is not inherently splice-aware. When used for RNA-Seq, it can be run in a mode that employs a reference file combining the genome with known exon-exon junctions, but it lacks the intrinsic capability of STAR or HISAT2 to de novo discover novel splice sites [29].

The table below summarizes the core algorithmic characteristics of each aligner.

Table 1: Fundamental Algorithmic Profiles of STAR, HISAT2, and BWA

| Aligner | Primary Design For | Core Indexing Algorithm | Splice-Aware? | Key Alignment Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAR | RNA-Seq | Uncompressed Suffix Array | Yes (De novo) | Seed extension for junction discovery |

| HISAT2 | RNA-Seq / DNA-Seq | Hierarchical Graph FM-index | Yes (De novo) | Graph-based alignment with local indexes |

| BWA (mem) | DNA-Seq | Burrows-Wheeler Transform (BWT) / FM-index | No (Requires junction library) | Maximal exact match (MEM) seeding |

Performance Benchmarking: A Data-Driven Comparison

Independent benchmarking studies have evaluated these aligners on critical metrics such as mapping rate, gene coverage, and computational resource consumption. The following data synthesizes results from experiments on real and simulated datasets.

Mapping Rates and Gene Coverage

Mapping rate—the percentage of input reads successfully placed on the reference—is a primary indicator of an aligner's sensitivity. In a study using data from Arabidopsis thaliana accessions, all tools demonstrated high proficiency, though with notable differences.

Table 2: Comparative Mapping Rates and Gene Detection

| Aligner | Mapping Rate (Col-0) | Mapping Rate (N14) | Genes Identified (Post-Filtering) |

|---|---|---|---|

| STAR | 99.5% | 98.1% | 24,515 |

| HISAT2 | ~98.5%* | ~97.5%* | 24,840 |

| BWA | 95.9% | 92.4% | 24,197 |

Note: HISAT2 values are estimated from graphical data in [24]. The study reported that all mappers except BWA, kallisto, and salmon (which used a transcriptomic reference) identified 33,602 genes before filtering. BWA's lower count is attributed to its use of a transcriptomic reference that excluded non-coding RNAs.

A separate study on grapevine powdery mildew fungus reinforced these findings, noting that BWA achieved an excellent alignment rate and coverage, though for longer transcripts (>500 bp), HISAT2 and STAR showed superior performance [28]. The high mapping rates of STAR and HISAT2 highlight their robustness in handling the spliced nature of RNA-Seq reads.

Computational Resource Requirements

Resource efficiency is a critical practical consideration, especially for large-scale studies or when working with limited computational infrastructure.

Table 3: Computational Resource and Speed Comparison

| Aligner | Typical Memory Usage (Human Genome) | Relative Speed | Indexing Speed |

|---|---|---|---|

| STAR | High (~30 GB RAM) | Fast | Slow |

| HISAT2 | Low (~5 GB RAM) | Very Fast | Fast |

| BWA | Low | Fast for DNA-Seq | Fast |

STAR's high memory consumption is a direct trade-off for its speed and sensitivity, making it less suitable for systems with limited RAM. HISAT2 was found to be approximately three-fold faster than the next fastest aligner in a runtime comparison, establishing it as a leader in speed and memory efficiency [26] [28]. BWA is also memory-efficient but its applicability to RNA-Seq is more limited.

Impact on Differential Gene Expression Analysis

The ultimate test of an aligner is its influence on downstream biological conclusions. Research has shown that while different aligners generate highly correlated raw count distributions, the choice of mapper can subtly influence the list of differentially expressed genes (DGE) identified.

In one study, the overlap of DGE results between aligner pairs was generally high (>92%). The most consistent results were observed between the pseudo-aligners kallisto and salmon, while comparisons involving STAR and HISAT2 with other mappers showed slightly lower overlaps (92-94%) [24]. This suggests that while all tools are broadly concordant, the specific algorithmic approach can lead to divergent calls for a subset of genes. It is critical to note that using a consistent downstream analysis tool (e.g., DESeq2) is vital, as switching the DGE software introduced greater variability than changing the aligner itself [24].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Aligners

To ensure the reproducibility and validity of alignment benchmarks, researchers should adhere to a standardized workflow. The following methodology is synthesized from several evaluated studies [24] [29].

Diagram 1: RNA-Seq Alignment Benchmarking Workflow

Key Steps in the Workflow:

- Data Preparation and Quality Control (QC): Begin with high-quality RNA-Seq datasets. The RNA Integrity Number (RIN) should ideally be greater than 7. Use tools like

TrimmomaticorFastQCto remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases [30] [31]. - Reference Genome Indexing: Each aligner requires building a specific index from the reference genome and annotation (GTF file).

- STAR: Use

STAR --runMode genomeGenerate. - HISAT2: Use

hisat2-buildalong with known splice site and exon information for optimal performance. - BWA: Use

bwa indexon the reference genome. For RNA-Seq, a reference that includes known exon-exon junctions (e.g., using JAGuaR) is necessary [29].

- STAR: Use

- Parallel Alignment: Map the trimmed FASTQ files from the same sample(s) against the reference using each aligner with its default or recommended parameters for RNA-Seq. This allows for a direct comparison.

- Post-processing: Sort the resulting BAM files and mark duplicates using tools like

SAMtoolsandPicard[29]. - Quantification and Downstream Analysis: Generate raw gene counts using a consistent tool like

featureCountsorHTSeq-count. Perform Differential Gene Expression (DGE) analysis with a standardized software likeDESeq2[24]. - Performance Evaluation: Compare the aligners based on key metrics:

- Mapping Rate: Percentage of uniquely mapped reads.

- Gene Coverage: Number of genes detected and coverage across transcript lengths.

- Runtime and Memory Usage.

- Junction Detection: Accuracy in identifying known and novel splice junctions.

- Concordance in DGE: Overlap of significantly differentially expressed gene lists.

A successful benchmarking study relies on a suite of reliable software and data resources. The table below details key components.

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Computational Tools for Alignment Benchmarking

| Category | Item / Software | Specification / Version | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment Tools | STAR | v2.6.0a or newer | Spliced alignment of RNA-Seq reads [29] |

| HISAT2 | v2.2.1 or newer | Memory-efficient spliced alignment [29] | |

| BWA | v0.7.17 or newer | DNA-Seq alignment, baseline for RNA-Seq [29] | |

| Analysis Suites | SAMtools | v1.16 or newer | Processing, sorting, and indexing BAM files [29] |

| Picard Tools | v2.27.4 or newer | Marking PCR duplicates in BAM files [29] | |

| DESeq2 | Latest Bioconductor | Statistical analysis of differential expression [24] | |

| Reference Data | GENCODE | Release 43 (GRCh38) | High-quality reference genome & annotation [29] |

| UCSC Genome Browser | GRCh37/hg19 | Source for reference genomes and annotations [29] |

The evidence from multiple benchmarking studies indicates that there is no single "best" aligner for all scenarios. The optimal choice depends on the specific research objectives, the biological system, and the available computational resources.

- For comprehensive splice-aware mapping where resources allow: STAR is the preferred choice. Its high sensitivity, excellent mapping rates, and superior ability to detect novel splice junctions make it ideal for discovery-focused projects run on servers with sufficient RAM (~30 GB for human) [24] [26].

- For efficient and robust standard analysis: HISAT2 offers an outstanding balance of performance and efficiency. Its high speed and low memory footprint, coupled with mapping rates and DGE results highly consistent with STAR, make it an excellent default choice for most RNA-Seq studies, including those on workstations with limited resources [26] [28].

- For specific applications or as a DNA-Seq baseline: BWA remains a powerful and efficient tool, but its lack of inherent splice-awareness limits its utility for standard RNA-Seq analysis. It may be used in specialized pipelines that rely strictly on known transcriptomes or as a component in workflows like RNA editing detection where a non-splice-aware aligner is specified [29].

In conclusion, researchers should base their selection on a clear understanding of these trade-offs. For the most reliable biological insights, particularly in drug development where reproducibility is paramount, it is often wise to validate key findings across multiple alignment pipelines [31].

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, the step of transcript quantification is critical for converting raw sequencing reads into gene or transcript abundance estimates. This process fundamentally shapes all downstream biological interpretations, from differential expression to biomarker discovery [30]. The core challenge in quantification lies in accurately assigning millions of short, non-unique sequencing reads to their correct transcriptional origins within a complex and often repetitive genome [32].

The field has largely diverged into two methodological approaches: traditional alignment-based methods and modern alignment-free methods. Alignment-based quantification, exemplified by tools like featureCounts, relies on first mapping reads to a reference genome using splice-aware aligners before counting reads overlapping genomic features [18]. In contrast, alignment-free tools such as Salmon and Kallisto employ sophisticated algorithms—including quasi-mapping and k-mer counting—to directly infer transcript abundances without generating full alignments, offering dramatic speed improvements [18] [32].

This guide objectively compares these competing strategies within the context of benchmarking RNA-seq workflows, synthesizing evidence from large-scale multi-center studies to inform researchers and drug development professionals about optimal tool selection based on their specific experimental requirements.

Core Computational Principles

Alignment-based quantification with featureCounts operates through a sequential, two-step process. First, a splice-aware aligner like STAR or HISAT2 maps sequencing reads to the reference genome, considering exon-exon junctions and producing SAM/BAM alignment files [18] [33]. Subsequently, featureCounts processes these alignments by counting reads that overlap annotated genomic features in a provided GTF/GFF file, assigning multi-mapping reads based on user-defined rules [18]. This method provides a tangible record of alignments for visual validation but requires substantial computational storage for intermediate BAM files [18].

Alignment-free quantification with Salmon and Kallisto bypasses explicit alignment through mathematical innovations. Kallisto implements pseudoalignment using a de Bruijn graph representation of the transcriptome to rapidly identify compatible transcripts for each read without determining base-pair coordinates [32] [34]. Salmon employs a similar quasi-mapping approach but incorporates additional sequence- and GC-content bias correction models [18] [32]. Both tools probabilistically assign reads to transcripts, efficiently handling multi-mapped reads through expectation-maximization algorithms to estimate transcript abundances in Transcripts Per Million (TPM) [32] [35].

Visual Workflow Comparison

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental procedural differences between these quantification strategies:

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

Comprehensive Performance Metrics Across Studies

Large-scale benchmarking studies reveal how these quantification strategies perform across critical dimensions including accuracy, computational efficiency, and robustness to different experimental conditions.

Table 1: Comprehensive Performance Comparison of Quantification Tools

| Performance Metric | featureCounts (Alignment-based) | Salmon (Alignment-free) | Kallisto (Alignment-free) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy for protein-coding genes | High correlation with qPCR validation [33] | High correlation with ground truth, but slightly lower for low-abundance genes [32] [15] | Similar to Salmon, excellent for highly-expressed transcripts [32] |

| Accuracy for small RNAs | Maintains better accuracy for small non-coding RNAs [32] | Systematically poorer performance for small RNAs (tRNAs, snoRNAs) [32] | Similar limitations with small and low-abundance RNAs [32] |

| Computational speed | Slowest (requires alignment first) [18] | 10-20x faster than alignment-based [18] | Fastest, minimal pre-processing required [18] [35] |

| Memory usage | High (especially when paired with STAR aligner) [18] | Moderate [18] | Low memory footprint [18] |

| Handling of repetitive regions | Struggles with multi-mapping in repetitive genomes [35] | Superior in highly repetitive genomes (e.g., trypanosomes) [35] | Excellent performance in repetitive genomes [35] |

| Reproducibility across labs | Higher inter-lab variation depending on aligner [15] | More consistent across laboratories [15] | High cross-laboratory consistency [15] |

Experimental Protocols from Key Benchmarking Studies

The performance data in Table 1 derives from rigorously designed benchmarking experiments. Understanding their methodologies is crucial for contextualizing the results.

MAQC/Quartet Multi-Center Study Protocol [15]:

- Reference Materials: Used well-characterized RNA reference samples from the MAQC consortium (human reference RNA vs. brain RNA) and Quartet project (samples from a Chinese family quartet)

- Spike-in Controls: Incorporated ERCC synthetic RNA spike-ins at known concentrations for absolute quantification assessment

- Experimental Design: 45 independent laboratories processed identical sample sets using their preferred RNA-seq workflows, generating 1080 libraries totaling ~120 billion reads

- Analysis Pipeline: Compared 140 bioinformatics pipelines combining different alignment, quantification, and normalization methods

- Validation: Used TaqMan qRT-PCR measurements as ground truth for 973 genes

Total RNA Benchmarking Protocol [32]:

- Specialized Library Preparation: Employed TGIRT-seq (thermostable group II intron reverse transcriptase) to comprehensively recover structured small non-coding RNAs alongside long RNAs

- Sample Set: Four MAQC samples with triplicate sequencing, including mixtures with known ratios

- Pipeline Comparison: Systematically compared four pipelines: Kallisto, Salmon, HISAT2+featureCounts, and a customized iterative mapping pipeline

- Accuracy Assessment: Evaluated detection sensitivity, expression level correlation, and fold-change estimation accuracy against known sample mixtures and spike-in controls

Repetitive Genome Assessment Protocol [35]:

- Biological System: Focused on Trypanosoma cruzi, a parasitic protozoan with highly repetitive genome characterized by large multigene families

- Simulation Approach: Created benchmark datasets with known expression values to measure quantification accuracy under controlled conditions

- Pipeline Evaluation: Compared five RNA-seq pipelines including Bowtie2+featureCounts, STAR+featureCounts, STAR+Salmon, Salmon, and Kallisto

- Annotation Enhancement: Tested whether including untranslated regions (UTRs) in gene annotations improved ambiguous read assignment

Decision Framework and Research Applications

Strategic Tool Selection Guidelines

Choosing between alignment-based and alignment-free quantification strategies requires careful consideration of the research objectives, experimental system, and computational resources.

Table 2: Decision Framework for Selecting Quantification Methods

| Research Scenario | Recommended Approach | Rationale | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard differential expression (mRNA) | Alignment-free (Salmon/Kallisto) | Superior speed with comparable accuracy for protein-coding genes | [18] [35] [36] |

| Small non-coding RNA analysis | Alignment-based (featureCounts) | Better accuracy for small, structured RNAs | [32] |

| Clinical diagnostics with subtle differential expression | Alignment-based with optimized pipeline | Higher sensitivity for detecting small expression changes | [15] |

| Large-scale screening studies | Alignment-free (Salmon/Kallisto) | Dramatically faster processing enables higher throughput | [18] [35] |

| Organisms with repetitive genomes | Alignment-free (Salmon/Kallisto) | More accurate quantification for multi-gene families | [35] |

| Computationally constrained environments | Alignment-free (Kallisto) | Lowest memory requirements and fastest processing | [18] |

| Studies requiring alignment visualization | Alignment-based (featureCounts) | Generates BAM files for IGV visualization and manual inspection | [18] |

Impact on Downstream Analyses

Quantification method selection significantly influences downstream biological interpretations, particularly in clinically relevant applications:

Molecular Subtyping in Cancer:

- In bladder cancer subtyping, the LundTax classifier demonstrated robustness to quantification methods, while consensusMIBC and TCGA classifiers showed high variability depending on preprocessing choices [36]

- Log transformation of expression values (standard for count-based methods like featureCounts) proved crucial for centroid-based classifiers, while distribution-free algorithms like LundTax performed consistently across quantification strategies [36]

Detection of Subtle Differential Expression:

- In multi-center studies, inter-laboratory variation was significantly higher when detecting subtle differential expression (as in clinical subtypes) compared to large expression differences [15]

- Alignment-based methods showed advantages for identifying small expression changes between similar biological conditions when optimized normalization and filtering strategies were applied [15]

Successful implementation of RNA-seq quantification workflows requires both computational tools and high-quality biological resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for RNA-seq Quantification Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | MAQC RNA samples (UHRR, Brain), Quartet Project reference materials | Enable cross-laboratory standardization and pipeline benchmarking [32] [15] |

| Spike-in Controls | ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix | Provide known concentration transcripts for absolute quantification and accuracy assessment [32] [15] |

| Quality Assessment Tools | FastQC, MultiQC, RIN evaluation | Assess RNA integrity and sequencing library quality before quantification [17] [30] |

| Reference Annotations | GENCODE, RefSeq, Ensembl | Provide transcript model definitions essential for accurate read assignment [35] [36] |

| Stranded Library Prep Kits | Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep | Preserve transcript orientation information crucial for resolving overlapping genes [30] |

| Ribosomal Depletion Kits | Illumina Ribozero, Twist Ribopool | Reduce ribosomal RNA content to enhance coverage of informative transcripts [30] |

The choice between alignment-based and alignment-free quantification strategies represents a fundamental decision in RNA-seq workflow design with significant implications for data quality and biological interpretation. Alignment-free tools like Salmon and Kallisto provide exceptional computational efficiency and perform excellently for standard differential expression analysis of protein-coding genes, making them ideal for high-throughput studies and computationally constrained environments. Conversely, alignment-based approaches with featureCounts maintain advantages for specialized applications including small RNA quantification, detection of subtle expression changes, and when alignment visualization is required for validation.

Evidence from large-scale benchmarking studies indicates that optimal tool selection depends critically on the specific research context—including the RNA biotypes of interest, the genetic complexity of the study organism, and the required analytical sensitivity. As RNA-seq continues evolving toward clinical applications, standardization of quantification methods and implementation of appropriate quality controls will be essential for generating reproducible, biologically meaningful results. Researchers should carefully match their quantification strategy to their experimental questions while maintaining awareness of the methodological limitations inherent in each approach.

Differential expression (DE) analysis represents a fundamental computational process in modern genomics research, enabling researchers to identify genes that show statistically significant changes in expression levels between different biological conditions. With the widespread adoption of high-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) technologies, the development of robust statistical methods for DE analysis has become increasingly important for advancing biological discovery and therapeutic development. The field has largely standardized around three principal tools that have demonstrated consistent performance across diverse experimental settings: DESeq2, edgeR, and limma-voom. Each implements distinct statistical approaches for handling count-based sequencing data, leading to nuanced differences in performance characteristics that can significantly impact analytical outcomes in practical research scenarios.

The broader thesis of benchmarking RNA-seq workflows extends beyond simple performance comparisons to encompass the evaluation of methodological robustness, computational efficiency, and biological relevance of findings. As noted in recent comprehensive assessments of bioinformatics algorithms, proper benchmarking requires "a systematic and comprehensive framework to provide quantitative, multi-scale, and multi-indicator evaluation" [37]. This review contributes to this ongoing methodological discourse by synthesizing current evidence regarding the relative strengths and limitations of these established DE analysis tools, with particular emphasis on their applicability to drug development and clinical research settings where analytical decisions can profoundly impact downstream conclusions.

Core Methodological Approaches

The three dominant packages for differential expression analysis—DESeq2, edgeR, and limma-voom—employ distinct statistical frameworks tailored to address the specific characteristics of RNA-seq count data, particularly overdispersion and variable sequencing depth.

DESeq2 utilizes a negative binomial distribution framework with gene-specific dispersion estimation. The algorithm begins with read count normalization using a median-of-ratio method, followed by three key steps: estimation of size factors to account for library size differences, gene-wise dispersion estimation using a combination of maximum likelihood and empirical Bayes shrinkage, and finally hypothesis testing using the Wald test or likelihood ratio test for more complex designs. DESeq2's dispersion shrinkage approach particularly benefits analyses with limited replication by borrowing information across genes to stabilize variance estimates, making it especially suitable for studies with few biological replicates [38] [39].

edgeR similarly employs a negative binomial model but implements a different empirical Bayes approach for dispersion estimation. The tool offers multiple testing frameworks, including the exact test for simple designs and generalized linear models (GLMs) for more complex experimental designs. A distinctive feature of edgeR is its use of quantile-adjusted conditional maximum likelihood for estimating dispersions, which enables robust performance even with minimal replication. The tool's "tagwise" dispersion method provides a balance between gene-specific and common dispersion approaches, allowing for flexible modeling of variability across the dynamic range of expression levels [38].

limma-voom takes a different methodological approach by transforming RNA-seq data to make it amenable to linear modeling. The "voom" component (variance modeling at the observational level) converts counts to log2-counts per million (logCPM) and estimates mean-variance relationships to compute observation-level weights for subsequent linear modeling. These weights are then incorporated into limma's established empirical Bayes moderated t-test framework, which borrows information across genes to stabilize variance estimates. This hybrid approach combines the precision of count-based modeling with the computational efficiency and flexibility of linear models, particularly advantageous for large datasets and complex experimental designs [38] [40].

Comparative Theoretical Framework

Table 1: Statistical Foundations of DESeq2, edgeR, and limma-voom

| Feature | DESeq2 | edgeR | limma-voom |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Distribution | Negative binomial | Negative binomial | Linear model after transformation |

| Dispersion Estimation | Gene-specific with empirical Bayes shrinkage | Empirical Bayes tagwise or trended | Mean-variance relationship modeling |

| Normalization | Median-of-ratios | Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) | Counts transformed to logCPM with TMM normalization |

| Hypothesis Testing | Wald test or LRT | Exact test or GLM LRT | Empirical Bayes moderated t-test |

| Data Input | Raw counts | Raw counts | Raw counts or transformed data |

| Handling of Low Counts | Automatic filtering | Maintains low counts with robust normalization | Down-weights in linear modeling |

The theoretical distinctions between these methods manifest in practical performance differences. DESeq2's conservative dispersion estimation tends to provide better control of false positives in low-replication scenarios, while edgeR's approach can offer enhanced sensitivity for detecting differentially expressed genes with modest fold changes. Limma-voom's transformation-based approach provides computational advantages for large sample sizes while maintaining competitive performance in terms of false discovery rate control [38] [39].

Performance Benchmarking and Comparative Analysis

Experimental Design and Dataset Characteristics

Comprehensive benchmarking of differential expression tools requires diverse datasets with varying experimental designs, sample sizes, and sequencing characteristics. Well-controlled comparative studies typically utilize both simulated data with known ground truth and real experimental datasets with validation through orthogonal methods. Key dataset characteristics that influence method performance include:

- Sample size and replication level: Ranging from minimal replication (n=2-3 per group) to large cohort studies (n>50 per group)

- Sequencing depth: From shallow (5-10 million reads) to deep sequencing (50+ million reads)

- Effect sizes: Mix of large and small fold changes to assess sensitivity and specificity

- Spike-in controls: Especially useful for evaluating false discovery rates

- Population diversity: Homogeneous versus heterogeneous sample populations

Recent benchmarking efforts have emphasized the importance of multi-dimensional evaluation criteria, including not only statistical accuracy but also computational efficiency, stability, and usability across diverse data types [37]. These principles inform the synthesis of performance data presented in this section.

Quantitative Performance Comparisons

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking Across Multiple Experimental Scenarios

| Performance Metric | DESeq2 | edgeR | limma-voom | Notes on Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (Recall) | Moderate | High | Moderate-High | edgeR shows advantage with low-count genes; limma-voom excels with large sample sizes |

| Specificity (Precision) | High | Moderate | High | DESeq2 demonstrates conservative behavior with better FDR control in small samples |

| False Discovery Rate Control | Excellent | Good | Excellent | All methods maintain nominal FDR with sufficient replication |

| Computational Speed | Moderate | Moderate-Fast | Fast | limma-voom shows significant speed advantages with large sample sizes (>20 per group) |

| Memory Usage | Higher | Moderate | Lower | DESeq2 requires more memory for complex experimental designs |

| Small Sample Performance (n<5) | Good | Good | Moderate | Both DESeq2 and edgeR designed for minimal replication; limma-voom requires modification |

| Large Sample Performance (n>20) | Good | Good | Excellent | limma-voom's linear model framework scales efficiently |

| Handling of Complex Designs | Good | Excellent | Excellent | edgeR and limma-voom particularly strong with multi-factor experiments |

Empirical evidence from multiple independent comparisons indicates that the relative performance of these tools is highly dependent on specific experimental conditions. In scenarios with limited biological replication (n=3-5 per group), DESeq2 and edgeR typically demonstrate superior performance in terms of specificity and sensitivity, respectively. As sample sizes increase (n>10 per group), limma-voom becomes increasingly competitive while offering substantial computational advantages [38].

A notable finding across multiple benchmarking studies is the complementary nature of these tools rather than clear superiority of any single method. Research comparing microbial community analyses found that "I generally try a few models that seem reasonable for the data at hand and then prioritize the overlap in the differential feature set," highlighting the value of consensus approaches [40]. This observation aligns with the broader trend in bioinformatics benchmarking, where context-dependent performance necessitates tool selection based on specific data characteristics and research objectives.