Bulk RNA Sequencing: A Comprehensive Guide from Principles to Clinical Applications

This article provides a complete overview of bulk RNA sequencing, covering its foundational principles, step-by-step methodological workflow, and diverse applications in biomedical research and drug development.

Bulk RNA Sequencing: A Comprehensive Guide from Principles to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a complete overview of bulk RNA sequencing, covering its foundational principles, step-by-step methodological workflow, and diverse applications in biomedical research and drug development. It details the experimental process from sample preparation to bioinformatics analysis, addresses key troubleshooting and optimization strategies for robust results, and offers a comparative analysis with emerging single-cell technologies. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current best practices and future directions, empowering readers to effectively design, implement, and interpret bulk RNA-seq studies for advancing personalized medicine and clinical diagnostics.

The Essential Guide to Bulk RNA-Seq Principles and Technology

The journey of transcriptomics has been marked by a series of revolutionary technological advances, with RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) representing one of the most significant breakthroughs in functional genomics. This evolution from Sanger sequencing to next-generation sequencing (NGS) has fundamentally transformed how researchers investigate gene expression, discover novel transcripts, and understand cellular mechanisms. For researchers focused on bulk RNA sequencing—which measures the average gene expression across populations of thousands to millions of cells—this technological progression has enabled increasingly sophisticated investigations into development, disease mechanisms, and drug responses. This technical guide examines the key transitions in RNA sequencing technologies, their impact on bulk RNA-seq methodologies, and the practical considerations for contemporary research applications.

Historical Context: From Sanger to Sequencing Revolution

The foundation of DNA sequencing was established in the 1970s with Frederick Sanger's development of the chain-termination method, also known as dideoxy sequencing [1]. This approach, which became known as Sanger sequencing, relied on fluorescently-labeled dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs) that terminate DNA strand elongation at specific nucleotide positions, followed by capillary gel electrophoresis to separate the fragments by size and determine the sequence [1] [2].

Sanger sequencing provided the foundation for transcriptomics through expressed sequence tag (EST) libraries and sequencing of cDNA clones [3]. However, these approaches were relatively low throughput, expensive, and generally not quantitative [3]. Tag-based methods like serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) and massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS) were developed to overcome some limitations but still faced challenges with mapping short tags and distinguishing isoforms [3].

The critical limitation of Sanger sequencing was its fundamental throughput constraint—it could only sequence a single DNA fragment at a time [4]. This bottleneck made comprehensive transcriptome analysis prohibitively expensive and time-consuming, setting the stage for a paradigm shift with the arrival of NGS technologies.

The Next-Generation Sequencing Revolution

Next-generation sequencing technologies transformed transcriptomics by introducing massively parallel sequencing, enabling millions of DNA fragments to be sequenced simultaneously in a single run [4]. This fundamental shift in scale provided several decisive advantages over Sanger sequencing for RNA analysis, particularly for bulk RNA-seq applications.

Table 1: Key Technical Comparisons Between Sanger Sequencing and Next-Generation Sequencing

| Aspect | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Low (one fragment at a time) [4] | High (millions of fragments simultaneously) [4] |

| Detection Limit | ~15-20% [4] [1] | As low as 1% for low-frequency variants [4] [2] |

| Discovery Power | Limited for novel variants [4] | High discovery power for novel transcripts/isoforms [4] [5] |

| Dynamic Range | Limited | >8,000-fold [3] |

| Read Length | 500-700 bp [1] | 30-400 bp (technology-dependent) [3] |

| Cost Effectiveness | Good for 1-20 targets [4] | Better for larger numbers of targets/samples [4] |

The advantages of NGS for transcriptome analysis are profound. RNA-seq provides a "far more precise measurement of levels of transcripts and their isoforms than other methods" with a dynamic range spanning over 8,000-fold [3]. Unlike hybridization-based approaches like microarrays, RNA-seq is not limited to detecting transcripts that correspond to existing genomic sequence, has minimal background signal, and requires less RNA sample [3]. These characteristics make it particularly valuable for discovering novel transcripts, alternative splice sites, and gene fusions [5].

Bulk RNA-Sequencing: Methodology and Workflow

Bulk RNA-seq is a widely used technique that measures gene expression in samples consisting of large pools of cells, such as tissues, whole organs, or sorted cell populations [6] [7] [8]. This approach provides a population-level average gene expression profile, making it valuable for differential expression analysis between conditions (e.g., diseased vs. healthy, treated vs. control) and for obtaining global expression profiles from whole tissues or organs [8].

Experimental Workflow

The standard bulk RNA-seq workflow involves multiple critical steps:

Sample Preparation and RNA Extraction: Biological samples are processed to extract total RNA. Due to ribosomal RNA (rRNA) typically constituting 80-95% of the total RNA population, it is usually removed to focus sequencing on transcripts of interest [5]. This is achieved through either poly(A) selection to enrich for messenger RNA (mRNA) or ribosomal depletion [5] [7].

Library Preparation: The RNA is converted to complementary DNA (cDNA) through reverse transcription, since current NGS platforms sequence DNA rather than RNA directly. The cDNA is then fragmented into appropriate sizes (typically 200-500 bp) for sequencing, and adapters are ligated to the fragments [3] [9]. These adapters facilitate the sequencing reaction and often include barcodes to allow multiplexing of multiple samples.

Sequencing: The prepared libraries are loaded onto NGS platforms where massive parallel sequencing occurs, generating millions of short reads [3]. The specific read length (30-400 bp) and number of reads per sample depend on the sequencing technology and experimental design [3].

Data Analysis: The generated sequences (raw reads) undergo a computational pipeline including quality control, alignment to a reference genome/transcriptome, and quantification of gene expression levels [10] [9].

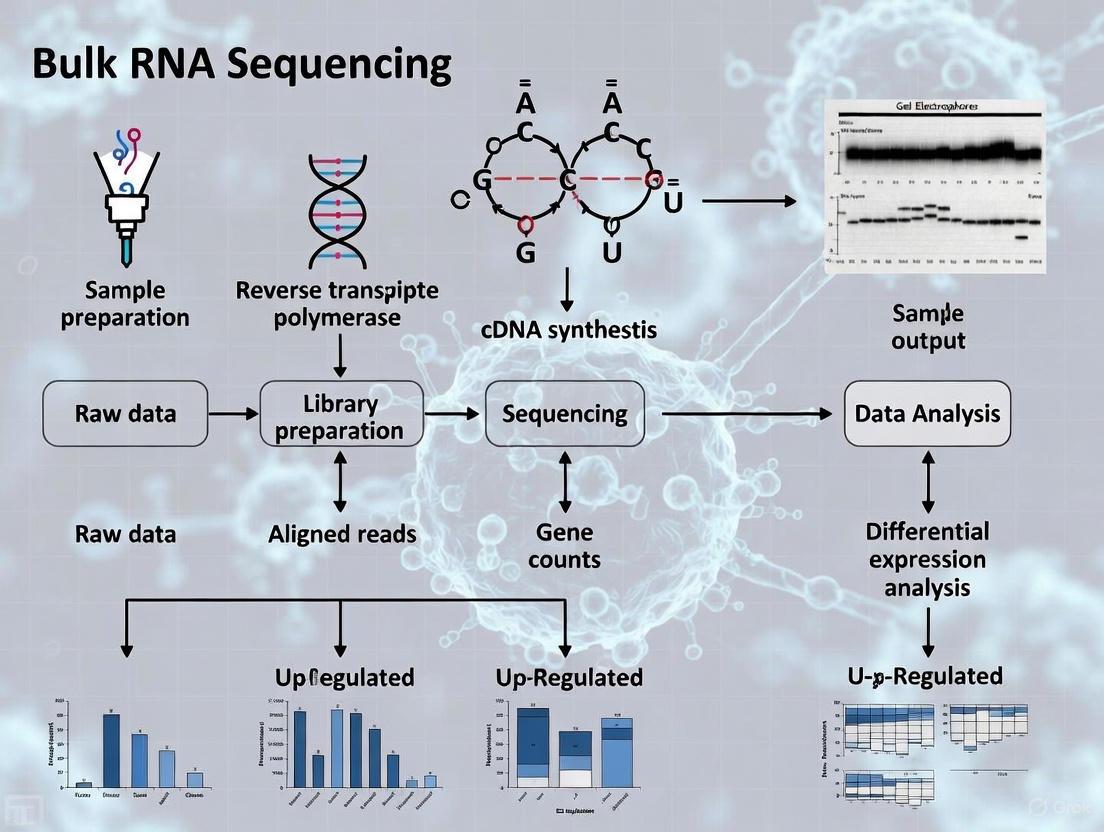

Diagram 1: Bulk RNA-seq experimental workflow

Quantification and Bioinformatics Analysis

A critical challenge in RNA-seq is converting raw sequencing data into accurate gene expression measurements. This involves addressing two levels of uncertainty: "identifying the most likely transcript of origin of each RNA-seq read" and "converting read assignments to a count matrix" that models the uncertainty inherent in many read assignments [6].

Two primary computational approaches have emerged for this quantification:

Alignment-Based Methods: Tools like STAR or HISAT2 perform formal alignment of sequencing reads to either a genome or transcriptome, producing detailed alignment maps that record exact coordinates of sequence matches [6] [9]. The aligned reads are then assigned to genes using tools like featureCounts [9].

Pseudoalignment Methods: Tools such as Salmon and kallisto use lightweight algorithms that perform probabilistic mapping of reads to transcripts without exact base-level alignment, significantly improving speed [6]. These tools simultaneously address both levels of uncertainty—read origin and count conversion—and are particularly valuable for large-scale studies.

For bulk RNA-seq analysis, the end result is typically a count matrix where rows represent genes and columns represent samples, with each cell containing the estimated number of reads originating from that gene in that sample [6]. This matrix serves as the input for downstream differential expression analysis using statistical methods in tools like limma or DESeq2 [6] [10].

Diagram 2: Bulk RNA-seq data analysis pipeline

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Strand-Specific Libraries

An important methodological consideration is the construction of strand-specific libraries, which preserve information about the transcriptional orientation of reads [3]. This is particularly valuable for transcriptome annotation, especially in genomic regions with overlapping transcription from opposite strands [3]. While early methods for creating strand-specific libraries were laborious and inefficient, technical advances have made this approach more accessible.

Experimental Design and Batch Effects

Proper experimental design is crucial for generating meaningful RNA-seq data. A well-designed experiment minimizes batch effects—technical variations that can occur during sample processing, RNA isolation, library preparation, or sequencing runs [10]. Strategies to mitigate batch effects include processing controls and experimental conditions together, performing RNA isolation on the same day, and sequencing compared groups in the same run [10].

Targeted RNA Sequencing

While whole transcriptome approaches are common, targeted RNA sequencing provides a cost-effective alternative that focuses on specific transcripts of interest [5]. This approach uses hybridization capture or amplicon-based methods to enrich for genes of interest, bypassing the need for rRNA depletion and enabling more streamlined data analysis [5]. Targeted approaches are particularly valuable for analyzing limited or degraded RNA samples, such as those from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue [5].

Applications of Bulk RNA-Seq in Research and Drug Development

Bulk RNA-seq has become an indispensable tool in biological research and pharmaceutical development with several key applications:

Differential Gene Expression Analysis: By comparing bulk gene expression profiles between different experimental conditions, researchers can identify genes that are upregulated or downregulated in disease states, following drug treatments, or across developmental stages [8].

Biomarker Discovery: RNA-seq facilitates the discovery of RNA-based biomarkers and molecular signatures for diagnosis, prognosis, or patient stratification in various diseases [8].

Pathway and Network Analysis: Investigating how sets of genes (pathways and networks) change collectively under various biological conditions provides systems-level insights into drug mechanisms and disease processes [8].

Novel Transcript Discovery: Bulk RNA-seq data can be used to annotate isoforms, non-coding RNAs, alternative splicing events, and gene fusions that may represent novel therapeutic targets [8].

Table 2: Common RNA Sequencing Methods and Their Research Applications

| RNA Sequencing Method | Description and Benefits | Common Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Total RNA/Whole Transcriptome | Examines coding and noncoding RNA simultaneously; suitable for novel discovery [5] | Comprehensive transcriptome annotation, novel gene discovery |

| mRNA Sequencing | Poly(A) selection to sequence all messenger RNA; identifies novel and known content [5] | Differential gene expression analysis, isoform characterization |

| Targeted RNA Sequencing | Sequences specific transcripts of interest to focus efforts and lower costs [5] | Biomarker validation, clinical assay development, large cohort studies |

| smRNA Sequencing | Isolation of small RNA to focus on noncoding RNA like microRNA [5] | miRNA profiling, regulatory network analysis |

Successful bulk RNA-seq experiments require careful selection of reagents and resources throughout the workflow:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Bulk RNA-Seq

| Item | Function | Examples/Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Remove abundant ribosomal RNA to focus sequencing on transcripts of interest [5] | Probe-based methods using biotinylated DNA or LNA probes; enzymatic approaches using RNase H [5] |

| Poly(A) Selection Kits | Enrich for messenger RNA through binding to polyadenylated tails [10] | Magnetic bead-based purification systems [10] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Convert RNA to sequencing-ready cDNA libraries with appropriate adapters [10] | Kits compatible with stranded protocols; those supporting low input amounts [10] |

| Strandedness Reagents | Preserve information about the transcriptional orientation of reads [3] | Chemical modification methods; direct RNA ligation approaches [3] |

| Quality Control Instruments | Assess RNA integrity and library quality before sequencing [10] | Instruments measuring RNA Integrity Number (RIN); capillary electrophoresis for library size distribution [10] |

| Reference Transcriptomes | Provide standardized gene annotations for read alignment and quantification | Ensembl, GENCODE, or species-specific databases |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Process raw sequencing data into interpretable results [6] [9] | Nextflow workflows like nf-core/rnaseq; command-line tools like STAR, Salmon; R packages like DESeq2, limma [6] [9] |

The evolution from Sanger sequencing to next-generation sequencing has fundamentally transformed transcriptomic research, with bulk RNA-seq emerging as a powerful, accessible technology for comprehensive gene expression analysis. While the core principles of RNA sequencing remain consistent—converting RNA to cDNA and determining its sequence—the massively parallel nature of NGS has enabled unprecedented scale, sensitivity, and discovery power. For research and drug development professionals, understanding both the technical foundations and practical considerations of bulk RNA-seq is essential for designing robust experiments, interpreting complex datasets, and advancing our understanding of biological systems and disease mechanisms. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve toward even higher throughput and longer read lengths, bulk RNA-seq will maintain its critical role in bridging population-level gene expression patterns with functional insights into cellular processes.

Bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) is a powerful next-generation sequencing (NGS) technique designed to measure the presence and abundance of ribonucleic acid molecules within a biological sample. This method provides a comprehensive transcriptome-wide profile by analyzing pooled RNA extracted from tissues or large collections of cells, offering an average gene expression snapshot across thousands to millions of cells [11] [12]. The fundamental power of bulk RNA-Seq lies in its ability to capture a broad dynamic range of expression, enabling the sensitive and accurate measurement of gene expression from both known and novel genomic features without the need for predesigned probes [12]. This technique has revolutionized transcriptomics by allowing researchers to investigate transcriptional activity, identify differentially expressed genes between conditions, and discover new RNA variants, thereby providing critical insights into gene regulation, disease mechanisms, and cellular responses to various stimuli [6] [11].

Unlike single-cell RNA-Seq which profiles individual cells, bulk RNA-Seq analyzes the collective RNA from a population, making it an indispensable tool for understanding overall transcriptomic changes in tissues, blood samples, or sorted cell populations. Its applications span from basic biological discovery to clinical drug development, where it is utilized for target identification, drug effect assessment, biomarker discovery, and mode-of-action studies [13]. The technology is particularly valuable in drug discovery workflows, where it helps researchers understand expression patterns in response to treatment, dose-response to compounds, and drug combination effects [13]. By providing both qualitative and quantitative data across the entire transcriptome, bulk RNA-Seq has become a cornerstone of modern genomic research, enabling scientists to detect transcript isoforms, gene fusions, single nucleotide variants, and other features that were previously challenging to identify [12].

Core Technical Principles

From Sample to Sequencing Library

The journey of bulk RNA-Seq begins with sample collection and preparation, where RNA is extracted from biological sources such as tissues, blood, or pooled cells. The quality and integrity of the input RNA are critical factors that significantly impact downstream results. For standard mRNA sequencing, the average library insert size should exceed 200 base pairs, with specific recommendations for read length (minimum 50 base pairs) and sequencing depth (typically 20-30 million aligned reads per replicate for robust statistical power) [11] [14].

Library preparation follows RNA extraction and involves several key steps to convert RNA into a sequence-ready format. The two primary approaches include:

- mRNA enrichment: Utilizing oligo dT beads to selectively capture polyadenylated transcripts from total RNA [12]

- rRNA depletion: Removing abundant ribosomal RNAs from total RNA samples to enable sequencing of both polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated RNAs [12]

The choice between these methods depends on research objectives. mRNA enrichment is suitable for studying protein-coding genes, while rRNA depletion provides a more comprehensive view of the transcriptome, including non-coding RNAs. For large-scale studies, particularly in drug discovery using cell lines, extraction-free RNA-Seq library preparation directly from lysates can save time and resources while handling larger sample numbers efficiently [13].

Strandedness is another crucial consideration in library preparation. Stranded RNA-Seq protocols preserve information about which DNA strand (sense or antisense) generated a transcript, enabling researchers to distinguish transcripts from overlapping genes, identify antisense sequences, and improve novel transcript annotation [12]. Experimental controls, including artificial spike-in RNAs such as SIRVs or ERCC mixes, are often incorporated to monitor technical performance, quantify RNA levels between samples, assess dynamic range, and serve as quality control metrics, especially in large-scale experiments [13] [11].

Sequencing and Alignment Fundamentals

Following library preparation, samples are sequenced using NGS platforms, generating millions of short DNA reads that correspond to fragments of the original RNA molecules. The resulting FASTQ files contain both the sequence data and associated quality scores, representing the raw data input for bioinformatic processing [6] [11].

The bioinformatic workflow addresses two primary levels of uncertainty in RNA-Seq analysis: determining the transcript of origin for each read, and converting these assignments into accurate count data [6]. Two principal computational approaches have emerged to address these challenges:

Alignment-based methods: Tools like STAR (Splice Aware Aligner) perform formal alignment of sequencing reads to either a reference genome or transcriptome, recording exact coordinates of sequence matches and mismatches [6] [11]. This approach generates SAM/BAM format files that detail alignment locations and scores, providing valuable data for extended quality checks but requiring significant computational resources.

Pseudoalignment methods: Tools such as Salmon and kallisto use lightweight algorithms that employ substring matching to probabilistically determine a read's origin without base-level alignment precision [6]. This approach is substantially faster than traditional alignment and simultaneously addresses both levels of uncertainty—read origin assignment and count estimation—while maintaining high accuracy.

A hybrid approach has gained popularity in best-practice workflows, combining the strengths of both methods. This involves using STAR for initial alignment to generate comprehensive quality control metrics, followed by Salmon operating in alignment-based mode to leverage its sophisticated statistical models for handling uncertainty in converting read origins to counts [6]. This combination provides both robust quality assessment and accurate quantification.

Table 1: Key Computational Tools for Bulk RNA-Seq Analysis

| Analysis Step | Tool Options | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read Trimming & QC | fastp, Trim Galore, Trimmomatic | Remove adapter sequences, low-quality bases | Fastp offers speed; Trim Galore integrates FastQC for quality reports [15] |

| Alignment | STAR, HISAT2, TopHat | Map reads to reference genome/transcriptome | STAR is splice-aware; preferred for junction mapping [6] [11] |

| Quantification | Salmon, kallisto, RSEM, HTSeq | Estimate transcript/gene abundance | Salmon uses probabilistic modeling; fast and accurate [6] |

| Differential Expression | DESeq2, limma | Identify statistically significant expression changes | Choice affects false discovery rates; consider data characteristics [6] [14] |

Standardized Processing Workflow

End-to-End Analysis Pipeline

A standardized bulk RNA-Seq processing workflow transforms raw sequencing data into biologically interpretable results through a series of interconnected steps. Modern best practices often utilize automated pipelines such as the nf-core RNA-seq workflow or the ENCODE Uniform Processing Pipeline, which ensure reproducibility and consistency across analyses [6] [11].

The workflow begins with quality control and read trimming, where adapter sequences and low-quality bases are removed using tools like fastp or Trim Galore. This critical first step improves subsequent mapping rates by eliminating technical artifacts that could interfere with alignment [15]. The quality of both raw and processed data should be assessed using metrics such as Q20/Q30 scores (representing base call accuracy of 99% and 99.9% respectively) and GC content distribution [15].

Following quality control, reads undergo alignment to a reference genome using splice-aware aligners like STAR, which account for intron-exon boundaries by employing specialized algorithms to detect splicing events. For organisms without high-quality reference genomes, alignment can be performed against transcriptome sequences instead. The output of this step is a BAM file containing genomic coordinates for each successfully mapped read [6] [11].

The next critical phase is quantification, where reads are assigned to genomic features (genes, transcripts, or exons) based on annotation files (GTF/GFF format). This process generates the fundamental data structure for downstream analysis: a count matrix with rows representing features and columns representing samples [6] [11]. Tools like RSEM (RNA-Seq by Expectation Maximization) employ statistical models to account for reads that map ambiguously to multiple genes or isoforms, while Salmon uses a lightweight-alignment approach to estimate transcript abundances [6].

The final analytical stage involves differential expression analysis using specialized statistical methods implemented in tools like limma or DESeq2. These approaches model count data using appropriate statistical distributions (typically negative binomial) to identify genes exhibiting significant expression differences between experimental conditions while controlling for multiple testing [6] [14]. The output is a list of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with associated statistical measures (p-values, false discovery rates, and fold changes), which serve as the basis for biological interpretation.

Quality Assurance and Normalization

Robust quality assurance is essential throughout the RNA-Seq pipeline to ensure reliable results. The ENCODE consortium has established comprehensive standards for bulk RNA-Seq experiments, including requirements for replicate concordance (Spearman correlation >0.9 between isogenic replicates), minimum read depths (30 million aligned reads per replicate), and metadata completeness [11].

Multiple quality metrics should be examined, including:

- Alignment rates: The percentage of reads that successfully map to the reference

- Genomic distribution: The proportion of reads mapping to exonic, intronic, and intergenic regions

- 3' bias: Potential preferential coverage at the 3' end of transcripts, particularly relevant for degraded samples

- Duplicate reads: Artifactual amplification of specific fragments

- RRNA contamination: Excessive mapping to ribosomal RNA genes

Following quantification, normalization is critical to remove technical variations and enable meaningful comparisons between samples. Different normalization strategies address distinct aspects of technical bias:

- Library size normalization: Accounts for differences in total sequencing depth between samples

- Gene length normalization: Corrects for the fact that longer genes naturally accumulate more reads (implemented in FPKM/RPKM/TPM)

- Compositional normalization: Addresses the fact that a small number of highly expressed genes can consume substantial sequencing depth

The most commonly used normalized units include:

- CPM: Counts Per Million - simple library size normalization

- FPKM: Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads - adjusts for both library size and gene length

- TPM: Transcripts Per Million - a more robust version of FPKM that accounts for the distribution of transcript lengths

Table 2: Standard Quantitative Outputs from Bulk RNA-Seq Analysis

| Output Metric | Calculation | Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Counts | Number of reads mapping to a feature | Primary input for differential expression analysis | Most statistically rigorous for DE testing [6] |

| CPM | Counts per million mapped reads | Basic cross-sample comparison | Does not account for gene length differences [16] |

| FPKM/RPKM | Fragments per kilobase per million | Gene expression normalization | Not comparable across samples [11] |

| TPM | Transcripts per million | Most reliable normalized unit | Comparable across samples [11] |

| Expected Counts | Probabilistic estimates accounting for multi-mapping | Input for differential expression | Generated by tools like Salmon, RSEM [6] |

Experimental Design Considerations

Replication and Statistical Power

Proper experimental design is paramount for generating biologically meaningful RNA-Seq data. A fundamental consideration is statistical power—the probability of detecting genuine differential expression when it truly exists. Underpowered experiments with insufficient replicates remain a prevalent issue in transcriptomics, with approximately 50% of human RNA-Seq studies using six or fewer replicates per condition, and 90% of non-human studies falling at or below this threshold [14].

The relationship between replicate number and statistical power is complex, influenced by effect sizes (magnitude of expression differences), biological variability, and sequencing depth. Empirical evidence suggests that a minimum of six biological replicates per condition is necessary for robust detection of differentially expressed genes, increasing to twelve or more replicates when comprehensive DEG detection is required [14]. While financial and practical constraints often limit replication numbers, researchers should prioritize biological replicates over technical replicates, as the former capture natural variation between individuals, tissues, or cell populations, while the latter primarily assess technical variation from sequencing runs or laboratory workflows [13] [14].

Pilot studies are highly valuable for determining appropriate sample sizes for main experiments by providing preliminary data on variability. Consulting with bioinformaticians during the planning phase can help researchers optimize the trade-off between cohort size, sequencing depth, and budget constraints [13]. For studies involving precious or limited samples, such as patient biopsies, researchers should employ statistical methods specifically designed for small sample sizes and interpret results with appropriate caution regarding false discovery rates [14].

Batch Effects and Confounding Factors

Batch effects—systematic technical variations introduced by processing samples at different times, locations, or personnel—represent a significant challenge in RNA-Seq studies. These non-biological variations can confound results if not properly addressed in the experimental design [13]. Large-scale studies inevitably incur batch effects as samples cannot be processed simultaneously due to logistical constraints.

Several strategies can mitigate batch effects:

- Randomization: Distributing samples from different experimental conditions across processing batches

- Blocking: Intentionally grouping similar samples together in processing batches

- Balanced design: Ensuring each batch contains proportional representation of all experimental conditions

- Batch correction algorithms: Statistical methods that remove technical variations during data analysis

Plate layout should be carefully planned to facilitate later batch correction in silico if complete randomization is impossible [13]. Additionally, spike-in controls provide an internal standard for normalizing between batches and monitoring technical performance across large experiments [13] [11].

Other important design considerations include:

- Time points: For time-course experiments, multiple time points should be included to capture dynamic gene expression changes

- Controls: Appropriate negative and positive controls should be incorporated, particularly in drug treatment studies

- Sample quality: RNA integrity number (RIN) should be assessed, with minimum thresholds established prior to sequencing

- Blinding: Whenever possible, sample processing and data analysis should be performed blinded to experimental conditions to minimize bias

Applications in Research and Drug Discovery

Bulk RNA-Seq has become an indispensable tool across biological research and pharmaceutical development due to its comprehensive transcriptome-wide profiling capabilities. In basic research, applications include characterizing transcriptional landscapes, identifying novel genes and splice variants, studying gene regulation, and understanding developmental processes [15] [12].

In the drug discovery and development pipeline, RNA-Seq is applied at multiple stages [13]:

- Target identification: Discovering novel disease-associated genes and pathways

- Mechanism of action studies: Elucidating how drug candidates affect cellular processes

- Biomarker discovery: Identifying expression signatures predictive of drug response

- Toxicology studies: Understanding off-target effects and compound toxicity

- Clinical trial stratification: Defining patient subgroups based on molecular profiles

The integration of bulk RNA-Seq with emerging technologies is expanding its applications further. For example, combining bulk transcriptomics with single-cell RNA-Seq enables researchers to contextualize findings at cellular resolution, distinguishing whether expression changes occur uniformly across cell types or are specific to particular subpopulations [16] [17]. Computational deconvolution methods leverage single-cell RNA-Seq references to estimate cellular proportions from bulk data, extending the utility of existing bulk RNA-Seq datasets [16] [17].

As a genomic resource, bulk RNA-Seq continues to contribute to large-scale mapping projects such as the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project and the Human Protein Atlas, which provide reference expression patterns across normal human tissues [17]. These resources enable researchers to interpret disease-associated genes in the context of normal tissue expression, identify tissue-specific drug targets, and understand the molecular basis of tissue specificity.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Bulk RNA-Seq Experiments

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Examples & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality RNA from biological samples | Choose based on sample type (cells, tissues, blood, FFPE); assess recovery of RNA species of interest [13] |

| Library Prep Kits | Prepare RNA for sequencing | Stranded mRNA vs. total RNA kits; consider 3'-end methods (QuantSeq) for large screens [13] [12] |

| Spike-in Controls | Monitor technical performance & normalize | ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix; SIRVs; use at ~2% of final mapped reads [11] |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Remove abundant ribosomal RNA | Critical for total RNA sequencing; enables detection of non-polyadenylated transcripts [12] |

| Reference Genomes | Sequence alignment and quantification | ENSEMBL, UCSC; requires matching GTF/GFF annotation files [6] [11] |

| Quality Control Tools | Assess RNA and library quality | Bioanalyzer, Fragment Analyzer; FastQC for sequence data [15] |

This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of the core terminology and methodologies underlying bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). Framed within a broader thesis on how bulk RNA sequencing works as a research tool, this document details the key concepts of reads, transcriptomes, and expression quantification. It is structured to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the foundational knowledge required to design, interpret, and critically evaluate bulk RNA-seq experiments, thereby enabling robust biological discovery and translational application.

Core Terminology and Definitions

In bulk RNA-seq, the transcriptome refers to the complete set of RNA transcripts in a biological sample, representing the functional output of the genome at a given time [18]. The process involves sequencing millions of these RNA fragments, generating reads, which are the short digital sequences determined by the instrument [10]. The primary goal is expression quantification, which estimates the abundance of each gene or transcript from the collected reads [6].

Quantitative Metrics for Expression

The table below summarizes the standard metrics used for quantifying gene expression from bulk RNA-seq data.

Table 1: Standard Gene Expression Quantification Metrics

| Metric | Full Name | Calculation | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Raw Count | Number of reads uniquely assigned to a gene. | Primary input for statistical tests in differential expression analysis (e.g., with DESeq2) [19] [20]. |

| FPKM | Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads | Count of fragments (for paired-end) or reads (for single-end) per kilobase of transcript length per million mapped reads. | Normalizes for gene length and sequencing depth; allows for comparison across different genes within a sample. |

| TPM | Transcripts Per Million | Proportional count of transcripts per million transcripts in the sample. | Normalizes for gene length and sequencing depth; considered more robust than FPKM for cross-sample comparison [18]. |

| CPM | Counts Per Million | Raw counts scaled by the total number of reads per sample (in millions). | Simple normalization for sequencing depth; does not account for gene length differences. |

The Bulk RNA-Seq Workflow: From Sample to Data

The bulk RNA-seq process is a multi-step protocol that converts biological samples into interpretable gene expression data.

Experimental Protocol

A generalized, detailed methodology is as follows:

- Sample Preparation and RNA Isolation: Cells or tissues are homogenized, and total RNA is isolated using methods like column-based kits or TRIzol reagents, with care taken to prevent RNA degradation [18]. For specific cell types, such as human neutrophils, isolation via negative selection kits is recommended to minimize activation [21]. RNA quality is assessed using instruments like a Bioanalyzer (generating an RNA Integrity Number, RIN >7.0 is often required) or Nanodrop [10] [18].

- Library Preparation: This step prepares the RNA for sequencing. While protocols vary, a common workflow includes:

- mRNA Enrichment: Poly(A)+ RNA is selected using magnetic beads, or ribosomal RNA (rRNA) is depleted [10] [22].

- cDNA Synthesis: RNA is reverse-transcribed into more stable complementary DNA (cDNA). In some protocols, early barcoding is used, where sample-specific DNA tags are incorporated during this step, allowing for later pooling of samples [23].

- Fragmentation and Adapter Ligation: The cDNA is fragmented (unless using a fragmentation-free protocol), and sequencing adapters are ligated to the ends. These adapters are essential for binding to the sequencing flow cell and for sample identification [10] [18] [22].

- PCR Amplification: The final library is amplified by PCR to introduce indices and generate sufficient material for sequencing [22].

- Sequencing: The pooled libraries are loaded onto a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina), which generates millions of short reads (typically 50-300 base pairs) per sample [18]. The output is raw data in the form of FASTQ files, which contain the nucleotide sequences and associated quality scores for each read [18] [6].

Computational Analysis Protocol

Once FASTQ files are generated, a bioinformatics pipeline is employed:

- Quality Control (QC): Raw reads in FASTQ files are assessed for quality, adapter contamination, and correct nucleotide distribution using tools like FastQC. Trimming tools like Trimmomatic or Cutadapt are used to remove low-quality bases and adapters [19] [18].

- Read Mapping/Alignment: The cleaned reads are aligned to a reference genome or transcriptome using splice-aware aligners like STAR or HISAT2. This step identifies the genomic origin of each RNA fragment [10] [11] [18].

- Expression Quantification: Reads that are uniquely mapped to genes are counted using tools like HTSeq-count or featureCounts, generating a count matrix where rows are genes and columns are samples [10] [19] [18]. Alternatively, alignment-free tools like Salmon use pseudoalignment to rapidly quantify transcript abundance [6] [20].

- Differential Expression Analysis: The count matrix is analyzed with statistical tools like DESeq2 or edgeR to identify genes that are significantly differentially expressed between experimental conditions (e.g., treated vs. control) [10] [19] [18]. These tools internally normalize counts to account for differences in library size and apply statistical models (e.g., negative binomial distribution) to test for significance [19].

Diagram 1: Bulk RNA-seq workflow from sample to analysis.

Visualizing Expression Quantification Concepts

The process of going from sequenced reads to a quantified transcriptome involves several conceptual steps that account for technical biases and biological variation.

Diagram 2: Core steps in expression quantification and normalization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of a bulk RNA-seq experiment relies on a suite of specialized reagents, tools, and software.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Bulk RNA-seq

| Category | Item | Function and Description |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Poly(A) Selection or Ribo-depletion Kits | Enriches for messenger RNA (mRNA) by targeting poly(A) tails or removing abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA) [10] [22]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase Enzyme | Synthesizes complementary DNA (cDNA) from the RNA template, a critical first step in library preparation [10] [23]. | |

| Library Preparation Kit (e.g., NEBNext, TruSeq) | Provides optimized enzymes and buffers for the end-repair, adapter ligation, and amplification steps to create sequencing-ready libraries [10] [23]. | |

| DNase I | Digests and removes contaminating genomic DNA from the RNA sample to ensure only RNA is sequenced [21] [23]. | |

| ERCC Spike-in Controls | Synthetic RNA molecules added at known concentrations to the sample, used as an external standard for evaluating technical sensitivity and accuracy of quantification [11]. | |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Quality Control Tools (FastQC, Trimmomatic) | Assess read quality and perform trimming to remove low-quality bases and adapter sequences [19] [18]. |

| Aligner (STAR, HISAT2) | Precisely maps sequencing reads to a reference genome, accounting for spliced transcripts [10] [11] [18]. | |

| Quantification Tool (HTSeq-count, featureCounts, Salmon) | Counts the number of reads mapped to each gene or transcript, generating the raw count matrix [10] [19] [6]. | |

| Differential Expression Tool (DESeq2, edgeR, limma) | Performs statistical analysis on the count matrix to identify significantly differentially expressed genes between conditions [10] [19] [6]. |

Bulk RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-Seq) is a powerful technique for measuring the average gene expression levels in a sample comprising a pooled population of cells or an entire tissue section [24] [25]. Its utility spans comparative transcriptomics, biomarker discovery, and understanding physiological and pathological mechanisms [26] [25]. The fundamental value of a bulk RNA-Seq experiment is not determined by the sequencing technology itself, but by the robustness of its experimental design. A carefully crafted design, with clearly defined objectives and meticulously planned sample groups, is the cornerstone for generating meaningful, reproducible, and biologically interpretable data. This is especially critical in applied fields like drug discovery, where RNA-Seq is used at various stages, from target identification to studying drug effects and treatment responses [13]. This guide outlines the core principles of defining objectives and sample groups within the broader context of how bulk RNA sequencing works, providing a framework for researchers to build successful experiments.

Defining the Research Objective and Hypothesis

The initial and most crucial step in any bulk RNA-Seq experiment is to establish a clear research objective and a testable hypothesis. This foundational work guides every subsequent decision, from the choice of model system to the depth of sequencing and the statistical methods for analysis [13].

Formulating the Core Question

A well-defined objective should specify the biological system, the conditions being compared, and the expected outcome. The hypothesis provides a specific, testable statement about gene expression changes under these conditions. A clear aim is essential to guide the experimental design, from the chosen model system and experimental conditions to the library preparation method and sequencing setup [13].

- Example Objective: To identify differentially expressed genes in liver tissue between a wild-type mouse model and a mouse model with a specific gene knockout.

- Example Hypothesis: The knockout of Gene X will lead to the significant upregulation of genes involved in the inflammatory response and downregulation of genes in the fatty acid metabolism pathway.

Aligning Objectives with Bulk RNA-Seq Capabilities

Bulk RNA-Seq is ideally suited for hypotheses concerning the average transcriptional profile of a cell population or tissue. Researchers should consider if their project requires a global, unbiased readout or if a targeted approach is more suitable [13]. Key questions to consider include:

- Is the biological question focused on the overall state of the tissue, or is it concerned with cellular heterogeneity?

- What type of RNA data is needed? Is the focus on quantitative gene expression, or are qualitative aspects like isoform usage, splice variants, or novel transcripts also of interest? [13]

- Does the experimental design offer the flexibility for future data mining? [13]

For investigations where cellular heterogeneity is a key factor, bulk RNA-Seq may be complemented or replaced by single-cell approaches. However, bulk RNA-Seq remains highly valuable, especially when studying homogenous cell populations, when sample suspension for single-cell analysis is difficult, or when the budget necessitates a larger number of replicates and conditions [23].

Fundamentals of Sample Group Design

Once the objective is defined, the next step is to design the sample groups that will robustly test the hypothesis. This involves defining conditions, controls, and determining the sample size with adequate replication.

Conditions and Controls

A typical bulk RNA-Seq experiment compares two or more conditions. The key is to design these groups to minimize confounding factors—where the effects of two different sources of variation cannot be distinguished [27].

- Treatment vs. Control: The most common design compares a treatment group (e.g., drug-treated cells) to an untreated control group. It is critical that the control group is appropriate and that animals or samples in each condition are matched for sex, age, litter, and batch wherever possible [27] [13].

- Avoiding Confounding: An experiment is confounded if you cannot separate the effects of your variable of interest from another, unaccounted-for variable. For example, if all control mice are female and all treatment mice are male, the effect of the treatment is confounded by sex [27]. To avoid this, ensure subjects are equally split between conditions for all known variables like sex, age, and batch [27].

- Experimental Controls: In addition to biological controls, artificial spike-in RNA controls can be valuable tools. These are added in known quantities to each sample and serve as an internal standard to measure the performance of the assay, including its dynamic range, sensitivity, and reproducibility [13].

The Critical Role of Replication

Replication is non-negotiable for a statistically sound bulk RNA-Seq experiment. It is essential for accounting for natural variation and ensuring findings are reliable and generalizable [27] [13].

Table 1: Types of Replicates in Bulk RNA-Seq

| Replicate Type | Definition | Purpose | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Replicate | Independent biological samples for the same condition (e.g., different individuals, animals, or cell cultures) [13]. | To measure biological variability and ensure findings are reliable and generalizable [13]. | Liver tissue from three different mice in each experimental group (treatment vs. control) [13]. |

| Technical Replicate | The same biological sample measured multiple times through the experimental workflow [13]. | To assess and minimize technical variation from sequencing runs, lab workflows, or the environment [13]. | Taking the same RNA sample and preparing three separate sequencing libraries from it [13]. |

For differential expression analysis, biological replicates are absolutely essential [27]. While technical replicates were more common with older technologies like microarrays, the technical variation in modern RNA-Seq is much lower than biological variation, making technical replicates largely unnecessary [27]. The primary focus should be on maximizing the number of independent biological replicates.

Sample Size and Statistical Power

The number of biological replicates per group (sample size) directly impacts the statistical power of the experiment—the ability to detect genuine differential expression. While large sample sizes are ideal, they are often constrained by cost and sample availability [13].

- General Guidelines: For general gene-level differential expression, at least 3 biological replicates per condition are typically recommended [27] [13]. However, between 4-8 replicates per group are ideal for covering most experimental requirements and for increasing reliability when variability is high [13].

- Replicates vs. Sequencing Depth: Increasing the number of biological replicates generally provides more statistical power than increasing the sequencing depth per sample. The following diagram illustrates this relationship, showing that more replicates tend to return more differentially expressed genes than deeper sequencing [27].

Figure 1: The relative importance of biological replicates versus sequencing depth for identifying differentially expressed genes. Adapted from Liu, Y., et al., Bioinformatics (2014) [27].

- Consulting Specialists: It is always beneficial to consult a bioinformatician or data expert to discuss the study and sample size limitations concerning statistical power [13]. Pilot studies are an excellent way to assess preliminary data on variability and help determine the appropriate sample size for the main experiment [13].

Advanced Considerations: Batch Effects and Confounding

Even with well-defined groups and replicates, hidden technical artifacts can undermine an experiment. The most significant of these are batch effects.

Understanding and Managing Batch Effects

Batch effects are systematic, non-biological variations introduced by how samples are processed [13]. They can arise from differences in RNA isolation date, library preparation date, personnel, reagent lots, or equipment [27]. The effect of batches on gene expression can often be larger than the experimental effect of interest [27].

- Identifying Batches: If the answer to any of the following questions is 'No', you have batches [27]:

- Were all RNA isolations performed on the same day?

- Were all library preparations performed on the same day?

- Did the same person perform the RNA isolation/library prep for all samples?

- Did you use the same reagents for all samples?

Best Practices for Batch Management

- Avoid Confounding by Batch: The most critical rule is to never confound your experiment by batch. Do NOT process all samples from one condition in one batch and all samples from another condition in a separate batch [27].

- Balance Across Batches: Split replicates of the different sample groups across batches [27]. For example, if you have three treatment groups (A, B, C) and can only process six samples per day, you should process at least one sample from each group in every batch.

- Record Metadata: Always include comprehensive batch information in your experimental metadata. During the statistical analysis, this information can be used to regress out the variation due to batch, provided the design is not confounded [27].

Technical Specifications and the Scientist's Toolkit

With the biological design in place, attention must turn to the technical specifications that will support the research objectives.

Sequencing Depth and Read Length

The optimal sequencing depth and read length depend on the specific aims of the study. The following table summarizes general guidelines.

Table 2: Technical Specifications for Different Bulk RNA-Seq Applications

| Application | Recommended Sequencing Depth | Recommended Read Length | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Gene-level DE | 15-30 million single-end reads per sample [27]. | >= 50 bp [27]. | 15 million reads may be sufficient with >3 replicates; ENCODE suggests 30M [27]. |

| DE of Lowly Expressed Genes | 30-60 million reads per sample [27]. | >= 50 bp [27]. | Start with 30 million reads if you have a good number of replicates [27]. |

| Isoform-level DE (Known isoforms) | At least 30 million reads per sample; paired-end reads required [27]. | >= 50 bp; longer is better [27]. | Choose biological replicates over deeper sequencing [27]. |

| Isoform-level DE (Novel isoforms) | > 60 million reads per sample [27]. | Longer reads are beneficial (e.g., from PacBio or Oxford Nanopore) [26]. | Provides improved coverage for identifying new splicing events [26]. |

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

A successful bulk RNA-Seq experiment relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key items and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bulk RNA-Seq

| Item | Function | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kit | Isolates total RNA from cells or tissue. | Must be suitable for sample type (e.g., cell lines, blood, FFPE). Some kits retain small RNAs [13]. |

| DNase I | Digests genomic DNA contaminants during RNA purification. | Prevents amplification of genomic DNA, which is a particular concern for protocols capturing intronic reads [23]. |

| Poly(dT) Oligos / Beads | Enriches for polyadenylated mRNA from total RNA by binding the poly-A tail. | Used when the focus is on mature, protein-coding mRNA [26] [12]. |

| Ribo-depletion Reagents | Selectively depletes ribosomal RNA (rRNA) from total RNA. | Used for total RNA-seq, allowing quantification of non-polyadenylated RNAs and pre-mRNA [26] [7]. |

| Spike-in RNA Controls | Artificial RNA sequences added in known quantities to each sample. | Serves as an internal standard for normalization, quality control, and assessing technical performance [13]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesizes complementary DNA (cDNA) from the RNA template. | MMLV-derived enzymes are common; they can also prime DNA, highlighting the need for effective DNase treatment [23]. |

| Library Prep Kit | Prepares the cDNA for sequencing by adding platform-specific adapters. | Kits like Illumina TruSeq are standard. Early barcoding protocols (e.g., Prime-seq) can drastically reduce costs [23]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide tags added to each molecule during cDNA synthesis. | Allows bioinformatic identification and removal of PCR duplicates, improving quantification accuracy [23]. |

The overall workflow, from sample to data, integrates these components into a coherent pipeline, as shown below.

Figure 2: A generalized bulk RNA-Seq workflow, highlighting the critical RNA quality control checkpoint [26].

Bulk RNA-Seq Workflow: From Sample to Biological Insight

In bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq), the quality of the final data is profoundly determined at the very first steps: sample preparation and RNA extraction. This technical guide details the critical protocols and considerations for securing high-quality RNA, framing them within the broader context of how bulk RNA-Seq transforms biological starting material into actionable gene expression data. Bulk RNA-Seq measures the average expression level of individual genes across hundreds to millions of input cells, providing a global overview of the transcriptome from pooled cell populations, tissue sections, or biopsies [24] [12]. The integrity of this data hinges on the initial handling of source material, as minute introductions of contaminants, RNA degradation, or unintended biases during sample preparation can irrevocably compromise downstream analyses, leading to inaccurate biological interpretations. Adherence to rigorous, standardized protocols from the start is therefore not merely a preliminary step but a core determinant of the entire project's success.

Critical Pre-Extraction Considerations

The journey to quality RNA begins long before the extraction kit is opened. Several pre-analytical factors must be carefully controlled to preserve the native transcriptome.

Source Material and Handling

Source material can range from cultured cells and tissue biopsies to blood samples. A key consideration is that bulk RNA-Seq analyzes RNA pooled from a population of cells, providing a population-average expression profile [24]. Immediately upon collection, cellular RNA must be stabilized to prevent rapid degradation by ubiquitous RNases. For tissues, flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen is a standard method. Alternatively, immersion in commercial RNA stabilization reagents is highly effective, especially for longer storage or shipping [28]. Storage of stabilized samples should be at -80°C for long-term preservation [28]. It is critical to minimize the time between sample collection and stabilization, as delays can induce stress-related changes in gene expression that confound experimental results.

Experimental Design to Mitigate Batch Effects

A well-designed experiment accounts for and minimizes batch effects—technical sources of variation that are unrelated to the biological question. These effects can arise from multiple users, different days of RNA isolation, or separate sequencing runs. To mitigate this, researchers should process control and experimental samples simultaneously whenever possible, from RNA isolation through library preparation and sequencing [10]. Table 1 outlines common sources of batch effect and strategies to minimize them.

Table 1: Common Sources of Batch Effect and Mitigation Strategies

| Source Category | Specific Examples | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Multiple users; time of day; animal cage effects | Standardize protocols; harvest at same time of day; use littermate controls. |

| RNA Isolation & Library Prep | Different isolation days; technician variation; freeze-thaw cycles | Isolate RNA for all samples on the same day; minimize users. |

| Sequencing | Different sequencing lanes or runs | Sequence samples from all experimental groups on the same flow cell. |

RNA Extraction Methodologies

Selecting the appropriate RNA extraction method is crucial and depends on the sample type, required RNA species, and downstream applications.

Core Principles and Quantity Requirements

The fundamental goal of RNA extraction is to isolate total RNA that is pure, intact, and free of contaminants like genomic DNA, proteins, and salts. For standard bulk RNA-Seq library preparation, the recommended starting amount is typically between 100 ng to 1 µg of purified total RNA, with many core facilities recommending at least 500 ng [28]. Input requirements can be lower for more specialized, low-input protocols. The extracted RNA must be stored in an RNase-free environment, and its quality must be rigorously assessed before proceeding.

Comparison of Extraction Techniques

Several methods are available for RNA extraction, each with advantages and limitations. The choice of kit and method should be guided by the sample type and research needs. Table 2 provides a comparative overview of different RNA extraction technologies.

Table 2: Comparison of RNA Extraction Methods and Kits

| Best For | Product Name | Starting Material | RNA Types Isolated | Isolation Method/Format | Prep Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple, reliable, rapid method | PureLink RNA Mini Kit | Bacteria, blood, cells, liquid samples | Large RNA (mRNA, rRNA) | Silica spin column | 20 min |

| Micro RNA and total RNA | mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit | Cells, tissue | Small & large RNA (microRNA, tRNA, mRNA, rRNA) | Organic extraction + spin column | 30 min |

| High-throughput applications | MagMAX for Microarrays Total RNA Isolation Kit | Blood, cells, tissue | Small & large RNA (microRNA, tRNA, mRNA, rRNA) | Plate-based + magnetic beads | <1 hr |

| mRNA sequencing | Dynabeads mRNA DIRECT Kit | Cell lysate | mRNA only | Magnetic bead capture | 15 min |

| FFPE tissue | MagMAX FFPE DNA/RNA Ultra Kit | FFPE curls | total RNA, microRNA, gDNA | Magnetic beads | 48 min (for 96 preps) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful RNA extraction and library preparation rely on a suite of specialized reagents. The following table details key solutions used in the featured protocols.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-Seq Sample Preparation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization Reagents (e.g., TRIzol) | Protects RNA from degradation immediately after sample collection by inactivating RNases. |

| DNase I | Enzyme that degrades residual genomic DNA during extraction to prevent DNA contamination in RNA-seq libraries. |

| Silica Spin Columns / Magnetic Beads | Solid-phase matrices that bind RNA specifically under certain buffer conditions, allowing for purification from contaminants. |

| Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads | Used to selectively isolate polyadenylated mRNA from total RNA by binding to the poly-A tail. |

| ERCC RNA Spike-In Mixes | Synthetic RNA controls added to samples before library prep to monitor technical performance and quantify expression. |

| RiboMinus Probes | Used to selectively deplete ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which can constitute >80% of total RNA, to enrich for transcriptomic reads. |

| Unique Dual Index Adapters | DNA barcodes ligated to cDNA during library prep, allowing multiple samples to be pooled ("multiplexed") and sequenced together. |

Quality Control and Integrity Assessment

After extraction, RNA quality must be quantitatively assessed before proceeding to library construction. Two primary metrics are used:

- Concentration and Purity: Quantification using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) is preferred for accuracy. Spectrophotometric measurements (A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios) assess purity, with ideal ratios being ~2.0 for both, indicating minimal contamination from proteins or solvents [24].

- RNA Integrity: This is critical for sequencing success. The RNA Integrity Number (RIN) or equivalent metric is determined using systems like the Agilent TapeStation or Bioanalyzer. For bulk RNA-Seq, an RIN value >7.0 is generally considered the minimum threshold for high-quality data, with higher values (e.g., >8.0) being preferable [10]. Degraded RNA leads to 3' bias in sequencing libraries and reduces the power to detect full-length transcripts.

From RNA to Sequencing Library: Core Workflows

Once high-quality RNA is obtained, it is converted into a sequenceable library. The following diagram illustrates the two primary workflows for this process.

RNA Enrichment Strategies

As shown in the workflow, a key decision is the RNA enrichment strategy, which directly impacts the transcriptional features captured:

- Poly(A) Selection: This method uses oligo(dT) beads or magnetic particles to selectively isolate messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules that possess a poly-adenylated tail [12] [10]. This is the most common approach for standard gene expression profiling but will miss non-polyadenylated RNAs (e.g., some non-coding RNAs).

- rRNA Depletion: As an alternative, this method uses probes to remove abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which can constitute over 80% of total RNA [28]. This retains both polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated transcripts, providing a broader view of the transcriptome, and is particularly useful for studying non-model organisms or bacterial RNA.

Library Construction and Barcoding

Following enrichment, the RNA is converted to cDNA via reverse transcription. Adapters, which include sample-specific indices (barcodes), are then ligated to the fragments [28]. These barcodes enable the pooling of dozens of samples into a single sequencing run, as the sequencer reads can later be bioinformatically sorted back to their sample of origin. Early barcoding methods, where samples are given unique identifiers during the cDNA synthesis step, have been developed to significantly improve cost-efficiency by allowing early pooling of samples [23]. The final library is amplified by PCR to generate sufficient material for sequencing.

Sample preparation and RNA extraction form the foundational pillar of any robust bulk RNA-Seq study. The meticulous attention to detail during sample stabilization, the strategic selection of an extraction methodology suited to the biological question, and the rigorous application of quality control metrics are non-negotiable prerequisites. By ensuring the integrity of the RNA from the very start, researchers lay the groundwork for generating high-fidelity gene expression data, thereby maximizing the potential for meaningful biological discovery and the advancement of therapeutic development.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has instigated a transformative shift in molecular biology, enabling researchers to explore gene expression profiles and regulatory mechanisms within cells with unparalleled precision [29]. At the core of every bulk RNA-seq experiment lies the critical process of library preparation—a procedure that transcribes RNA molecules into a collection of DNA fragments appropriately structured for high-throughput sequencing platforms [29]. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles, methodologies, and practical considerations for converting RNA into sequence-ready libraries, framed within the broader context of bulk RNA sequencing workflow. Library preparation serves the multifaceted purpose of preserving biological information contained within RNA molecules while simultaneously incorporating essential adaptors and barcodes required for sequencing [29]. The quality of this initial step profoundly influences all subsequent data generation and interpretation, making its optimization essential for robust transcriptomic analysis.

Core Principles of Library Construction

The conversion of RNA to a sequence-ready library follows a defined series of molecular steps. The process initiates with RNA isolation from biological specimens, followed by fragmentation into smaller segments conducive to sequencing [29]. These RNA fragments undergo reverse transcription into complementary DNA (cDNA) using reverse transcriptase enzymes [29] [10]. The resulting cDNA fragments are processed through end repair to create blunt ends, facilitating the ligation of adaptors containing necessary sequencing motifs [30] [29]. Finally, the constructed library undergoes enrichment and size selection to isolate fragments within the desired size range, followed by rigorous quality control assessments prior to sequencing [29].

A critical innovation in modern library preparation is early barcoding, where sample-specific DNA tags are integrated during cDNA generation [23]. This approach allows pooling of samples from multiple experimental conditions early in the workflow, significantly reducing processing time and reagent costs while maintaining sample identity throughout the sequencing process.

Key Methodological Variations

Library preparation strategies diverge based on RNA transcript targets and enrichment methods:

Poly(A) Enrichment: This approach selectively captures messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules containing poly-A tails, focusing on the protein-coding transcriptome [30] [10]. The Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep kit exemplifies this method, providing cost-effective, scalable RNA sequencing of the coding transcriptome with precise strand orientation [30].

Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) Depletion: For comprehensive transcriptome analysis including non-coding RNAs, this method removes abundant ribosomal RNA through enzymatic or probe-based depletion [30]. The Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep employs integrated enzymatic depletion to remove both rRNA and globin mRNA in a single, rapid step [30].

Targeted Enrichment: Focusing on specific genes or transcripts of interest, this approach uses hybridization-based capture to enrich particular regions prior to sequencing [30]. The Illumina RNA Prep with Enrichment enables deep insights into focused gene sets without requiring mechanical shearing [30].

Table 1: Comparison of RNA Library Preparation Methods

| Method | Primary Target | Key Applications | Input Requirements | Hands-on Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA Sequencing | Poly-A-containing transcripts | Gene expression quantification, isoform identification | 25-1000 ng standard quality RNA [30] | < 3 hours [30] |

| Total RNA Sequencing | Whole transcriptome (coding and noncoding) | Novel feature detection, comprehensive transcriptome analysis | 1-1000 ng standard quality RNA; 10 ng for FFPE [30] | < 3 hours [30] |

| Targeted RNA Sequencing | Specific genes/transcripts of interest | Gene fusion detection, variant identification | 10 ng standard quality RNA [30] | < 2 hours [30] |

| Prime-seq | 3' tagged transcriptome | Cost-effective gene expression profiling | Not specified | Not specified |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

RNA Isolation and Quality Control

The library preparation process begins with RNA extraction, a step requiring meticulous attention to prevent degradation:

- Sample Collection: Employ aseptic techniques for procuring tissue or cell samples, promptly transferring them into RNase-free vessels to prevent RNA degradation [29].

- Homogenization: Utilize appropriate mechanical methods (tissue homogenization or bead milling) to disrupt cellular structures and facilitate RNA liberation [29].

- RNA Extraction: Execute RNA extraction using commercial isolation kits, adhering strictly to manufacturer guidelines. Include robust DNase treatment to eliminate genomic DNA contamination [29].

- Quality Assessment: Quantify RNA concentration and purity using spectrophotometry (NanoDrop) or fluorometry (Qubit). Evaluate RNA integrity through capillary electrophoresis (Bioanalyzer) or agarose gel electrophoresis [29] [10]. High-quality RNA typically demonstrates an RNA integrity number (RIN) >7.0 for reliable library construction [10].

Library Construction Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for converting quality-controlled RNA into sequence-ready libraries:

Diagram 1: RNA Library Preparation Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the key steps in converting isolated RNA into sequence-ready libraries, from fragmentation to final quality control.

RNA Fragmentation: Prepare fragmentation buffer according to manufacturer specifications, tailoring conditions to achieve desired fragment sizes (typically 200-500bp) [29]. Introduce isolated RNA into fragmentation buffer, incubating under specified temperature and time parameters. Terminate the reaction using stop solution or thermal inactivation [29].

cDNA Synthesis: Assemble a master mix containing reverse transcriptase enzyme, random primers, dNTPs, and RNase inhibitor. Incubate fragmented RNA within the master mix at appropriate temperatures to facilitate cDNA synthesis [29]. Purify synthesized cDNA using purification kits or magnetic beads to remove residual primers, enzymes, and salts [29].

End Repair and Adaptor Ligation: Execute end repair by treating purified cDNA with end repair enzymes and buffers to create blunt-ended fragments [29]. Prepare a ligation mix containing adaptors with unique barcodes or indices. Ligate adaptors to repaired cDNA termini under specified conditions, then purify ligated products to eliminate unligated adaptors [30] [29].

Size Selection and Amplification: Employ gel electrophoresis, bead-based purification, or automated liquid handling systems to isolate DNA fragments within the desired size range (typically 200-500bp for Illumina platforms) [29]. Amplify size-selected library fragments via PCR using primers complementary to adaptor sequences, optimizing conditions to minimize amplification bias and ensure uniform coverage [29].

Quality Control and Quantification

Rigorous quality assessment ensures library integrity before sequencing:

- Library Quantification: Employ qPCR with adaptor-specific primers or fluorometric quantification to accurately measure amplified library concentration [30] [29].

- Size Distribution Analysis: Evaluate library size distribution and integrity through capillary electrophoresis (Bioanalyzer) or agarose gel electrophoresis [29].

- Quality Metrics: Verify that libraries meet platform-specific specifications for concentration, size distribution, and adapter content. The ENCODE consortium recommends specific standards for bulk RNA-seq, including Spearman correlation >0.9 between isogenic replicates [11].

Technological Innovations in Library Prep

Tagmentation-Based Methods

A significant advancement in library preparation technology is bead-linked transposome tagmentation [30]. This innovative approach simultaneously fragments DNA and adds sequencing adapters using an engineered transposase enzyme complex, dramatically reducing hands-on time and processing steps. Tagmentation-based methods like those employed in the Illumina RNA Prep with Enrichment kit enable completion of the entire RNA or DNA workflow in a single shift, with approximately two hours of hands-on time [30].

Early Barcoding Strategies

Prime-seq exemplifies the efficient adaptation of single-cell RNA-seq principles to bulk sequencing, incorporating early barcoding to significantly reduce costs [23]. This method utilizes poly(A) priming, template switching, and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to generate 3' tagged RNA-seq libraries [23]. Research demonstrates that Prime-seq performs equivalently to standard methods like TruSeq but is fourfold more cost-efficient due to almost 50-fold cheaper library costs [23].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Library Prep Methods

| Method | Cost Efficiency | Hands-on Time | Complexity | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional TruSeq | Standard | 6.5-7 hours [30] | Moderate | Comprehensive coverage, established protocol |

| Tagmentation-Based | High | < 2 hours [30] | Low | Rapid protocol, minimal hands-on time |

| Prime-seq | Very High (4× TruSeq) [23] | Not specified | Moderate | Extreme cost efficiency, early barcoding |

| Stranded Total RNA | Moderate | < 3 hours [30] | Moderate | Whole transcriptome coverage, rRNA depletion |

Unique Molecular Identifiers

Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) represent another critical innovation, providing error correction and enhancing accuracy by reducing false-positive variant calls while increasing variant detection sensitivity [30]. These random DNA tags incorporated during library preparation enable precise identification of PCR duplicates, essential for accurate transcript quantification, particularly in low-input scenarios [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful library construction requires specific reagents and materials, each serving distinct functions in the workflow:

Table 3: Essential Reagents for RNA-seq Library Preparation

| Reagent/Category | Function | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation Kits | Purify RNA from biological samples | PicoPure RNA isolation kit [10], commercial kits with DNase treatment [29] |

| Poly(A) Selection Beads | Enrich for messenger RNA | NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA magnetic isolation kits [10], oligo-dT beads |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Remove ribosomal RNA | Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep with enzymatic depletion [30] |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesizes cDNA from RNA templates | MMLV-derived enzymes, template-switching variants [23] |

| Fragmentation Reagents | Break RNA into appropriately sized fragments | Enzymatic cleavage, chemical fragmentation, or sonication [29] |

| Library Prep Kits | Comprehensive reagents for end prep and adapter ligation | NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit [10], Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep [30] |

| Unique Dual Indexes | Enable sample multiplexing | Up to 384 UDIs for higher throughput sequencing [30] |

| Size Selection Beads | Isolate fragments within optimal size range | SPRI beads, AMPure XP beads [29] |

| Quality Control Instruments | Assess RNA and library quality | Bioanalyzer, TapeStation, Qubit fluorometer [29] [10] |

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Addressing Common Challenges

Several factors require careful consideration during library preparation optimization:

RNA Input Amount: Inadequate RNA input may cause biased library construction and reduced sequencing depth, while excess input can yield inefficient adaptor ligation and elevated background noise [29]. While 0.1-1 μg of total RNA is generally recommended, specialized kits can handle much lower inputs [29].

Fragmentation Method: The choice between sonication, enzymatic cleavage, or chemical fragmentation influences size distribution and cDNA fragment integrity [29]. Optimization should align with experimental requirements and sequencing platform specifications.

Adaptor Design: Adaptor architecture affects library complexity, sequencing coverage, and read quality [29]. Custom adaptor sequences with distinctive barcodes facilitate sample multiplexing and precise sample identification during data analysis.

Managing Technical Artifacts

Technical artifacts pose significant challenges in library preparation:

Genomic DNA Contamination: Despite DNase treatment during RNA isolation, residual genomic DNA can contribute to intronic reads [23]. Prime-seq validation experiments demonstrate that DNase I treatment effectively minimizes this contamination, confirming that most intronic reads derive from pre-mRNA rather than genomic DNA [23].

Batch Effects: Variations during experiment execution, RNA isolation, library preparation, or sequencing runs can introduce confounding batch effects [10]. Mitigation strategies include processing controls and experimental conditions simultaneously, minimizing users, and harvesting samples at consistent times [10].