Bulk RNA Sequencing: Principles, Applications, and Best Practices for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), a foundational genomic technique for profiling the average gene expression of cell populations.

Bulk RNA Sequencing: Principles, Applications, and Best Practices for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), a foundational genomic technique for profiling the average gene expression of cell populations. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers core principles from library preparation to sequencing. The scope extends to diverse methodological applications in disease research and drug discovery, offers guidance on troubleshooting and optimizing analysis pipelines, and delivers a comparative evaluation of statistical methods for differential expression analysis. By synthesizing current best practices, this guide aims to empower the effective application of bulk RNA-seq in both basic and translational research.

Demystifying Bulk RNA-seq: From Core Principles to Transcriptome Exploration

What is Bulk RNA-seq? Defining the Averaged Transcriptome Profile

Bulk RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq) is a foundational next-generation sequencing (NGS) method that enables comprehensive analysis of the transcriptome by measuring the average expression levels of thousands of genes across a population of cells. This technical guide explores the core principles, methodologies, and applications of bulk RNA-seq, framing it within the context of transcriptomics research for scientists and drug development professionals. We provide an in-depth examination of experimental design considerations, detailed workflows from sample preparation to data analysis, and a comparative analysis with single-cell approaches, supplemented with structured data tables and workflow visualizations to support experimental planning and implementation.

Bulk RNA sequencing is a powerful transcriptomic technique that provides a population-averaged gene expression profile from a sample containing a mixture of cells [1] [2]. Unlike single-cell approaches that resolve individual cellular profiles, bulk RNA-seq measures the collective transcriptome of hundreds to millions of input cells, yielding an expression readout that represents the average across all cells present in the sample [1] [3]. This method is particularly valuable for obtaining a global perspective of gene expression differences between sample conditions, such as diseased versus healthy tissues, or treated versus control groups [1] [2].

The fundamental principle of bulk RNA-seq involves converting RNA populations from biological samples into a library of cDNA fragments with adapters attached to one or both ends. Each molecule is then sequenced in a high-throughput manner to obtain short sequences from one end (single-end sequencing) or both ends (paired-end sequencing) [4]. The resulting sequences are aligned to a reference genome or transcriptome, and the abundance of each transcript is quantified based on the number of reads assigned to it. This process provides a digital measure of gene expression levels across the entire transcriptome, enabling researchers to identify differentially expressed genes between experimental conditions and explore biological pathways and networks that change under various biological contexts [2].

Core Principles and Applications

Key Characteristics

Bulk RNA-seq delivers a comprehensive transcriptome snapshot by capturing the averaged gene expression from all cells in a sample [1] [3]. This approach provides several key characteristics that make it valuable for specific research applications. First, it offers a population-level perspective that is well-suited for comparing transcriptomic profiles between different conditions, such as disease states, developmental stages, or treatment responses [2]. Second, it delivers higher sequencing depth per sample compared to single-cell approaches at similar costs, enabling better detection of lowly expressed transcripts [2]. Third, the technique benefits from established, robust protocols and more straightforward computational analyses compared to single-cell methods [2].

The averaged expression profile obtained through bulk RNA-seq can be particularly advantageous when the research question focuses on the collective behavior of cell populations rather than cellular heterogeneity. For instance, when studying tissue-level responses to pharmaceuticals or identifying biomarkers from tissue biopsies, the population average may be more biologically relevant than individual cell variations [2] [3]. Additionally, the ability to process multiple samples efficiently through multiplexing makes bulk RNA-seq ideal for large cohort studies and time-series experiments where many samples need to be compared [1] [3].

Primary Research Applications

Differential Gene Expression Analysis: By comparing bulk gene expression profiles between different experimental conditions, researchers can identify genes that are upregulated or downregulated in response to diseases, treatments, developmental stages, or environmental factors [2] [3]. This represents the most widespread application of bulk RNA-seq and forms the foundation for many discovery-based transcriptomic studies.

Biomarker Discovery: Bulk RNA-seq facilitates the identification of RNA-based biomarkers and molecular signatures for diagnosis, prognosis, or stratification of diseases [2]. The population-level expression profiles can reveal consistent patterns that correlate with clinical outcomes or treatment responses.

Pathway and Network Analysis: Investigating how sets of genes change collectively under various biological conditions allows researchers to identify activated or suppressed biological pathways and networks [2]. This systems-level analysis provides insights into the molecular mechanisms driving biological processes and disease pathologies.

Transcriptome Characterization: Bulk data can be used to annotate isoforms, identify non-coding RNAs, detect alternative splicing events, and characterize novel transcripts [2] [4]. This application is particularly valuable for annotating genomes of poorly characterized organisms or tissues.

Large Cohort Studies and Biobank Projects: The cost-effectiveness and established protocols of bulk RNA-seq make it suitable for large-scale transcriptomic profiling in population genetics and biobanking initiatives [2].

Experimental Design Considerations

Replication Strategy

Biological replicates are absolutely essential for bulk RNA-seq experiments designed to detect differential expression [5]. Biological replicates involve different biological samples of the same condition and are necessary to measure the biological variation between samples. In contrast, technical replicates, which use the same biological sample to repeat technical steps, are generally considered unnecessary with modern RNA-seq technologies because technical variation is much lower than biological variation [5].

The number of biological replicates significantly impacts the statistical power to detect differentially expressed genes. As shown in the table below, increasing the number of replicates tends to return more differentially expressed genes than increasing sequencing depth [5]. Generally, more replicates are preferred over greater sequencing depth for bulk RNA-seq experiments, with the caveat that higher depth is required for detection of lowly expressed genes or for isoform-level differential expression [5].

Table 1: Recommended Sequencing Depth and Replicates for Different Bulk RNA-seq Applications

| Application Type | Minimum Recommended Replicates | Recommended Sequencing Depth | Read Length Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| General gene-level differential expression | >3 | 15-30 million SE reads per sample | >= 50 bp |

| Detection of lowly-expressed genes | >3 | 30-60 million reads per sample | >= 50 bp |

| Isoform-level differential expression (known isoforms) | >3 | At least 30 million reads per sample | Paired-end, >= 50 bp |

| Novel isoform identification | >3 | >60 million reads per sample | Paired-end, longer reads better |

| Other RNA analyses (small RNA-seq, etc.) | As many as possible | Varies by analysis | Dependent on analysis |

Avoiding Confounding and Batch Effects

Proper experimental design must address potential confounding factors and batch effects that can compromise data interpretation. A confounded experiment occurs when separate effects of two different sources of variation cannot be distinguished [5]. For example, if all control samples are from female mice and all treatment samples are from male mice, the treatment effect would be confounded by sex effects.

Batch effects represent a significant issue for RNA-seq analyses and can arise from various sources [5]:

- RNA isolations performed on different days

- Library preparations performed on different days

- Different personnel performing RNA isolation or library preparation

- Different reagent batches used for different samples

- Sample processing in different locations

To minimize batch effects, researchers should [5] [6]:

- Design experiments to avoid batches when possible

- If batches are unavoidable, split replicates of different sample groups across batches

- Include batch information in experimental metadata to regress out variation during analysis

- Process samples in randomized order across experimental conditions

- Use the same reagents and protocols for all samples when possible

Methodological Workflow

Sample Preparation and Library Construction

The bulk RNA-seq workflow begins with RNA extraction from biological samples, which can include pooled cell populations, tissue sections, or biopsies [1] [7]. The quality of input RNA is critical for successful sequencing, typically assessed using the RNA Integrity Number (RIN), with a value over six considered sufficient for sequencing [7]. For low-input protocols, quality controls may be limited due to low RNA yield [1].

Following extraction, several preparation steps are performed:

- RNA Enrichment: Depending on the research focus, total RNA can be sequenced, or specific RNA types can be enriched through poly(A) selection for mRNA or ribosomal RNA depletion for non-coding RNA analysis [7].

- Reverse Transcription: RNA is converted to complementary DNA (cDNA) using reverse transcription, with some protocols incorporating barcoded primers to uniquely label each sample for multiplexing [1] [4].

- Second-Strand Synthesis: A second DNA strand is synthesized to create double-stranded cDNA [1].

- Fragmentation and Adapter Ligation: The cDNA is fragmented, and sequencing adapters are ligated to the fragments [4]. Some modern protocols, such as those from Lexogen, omit fragmentation and use random primers containing partial adapter sequences to streamline the process [4].

- Library Amplification: The library is amplified via PCR to add complete adapter sequences and indices [1] [4].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions in Bulk RNA-seq

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Barcoded Primers | Uniquely label each sample for multiplexing | Enable pooling of multiple samples; CEL-seq2-type barcodes are commonly used [1] |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Converts RNA to cDNA | Critical for faithful representation of transcriptome |

| rRNA Depletion Reagents | Remove ribosomal RNA | Increases sequencing coverage of non-ribosomal transcripts [7] |

| Poly(T) Oligos | Enrich for polyadenylated RNA | Targets mRNA; not suitable for non-polyadenylated RNAs [7] |

| Fragmentation Enzymes | Fragment RNA or cDNA | Physical, enzymatic, or chemical methods can be used [7] |

| Library Amplification Kit | Amplify library for sequencing | Can introduce bias if over-amplified |

Sequencing Approaches

Bulk RNA-seq can be performed using different sequencing strategies, each with distinct advantages:

Single-End vs. Paired-End Sequencing: Single-end sequencing reads fragments from one end only, while paired-end sequencing reads both ends of fragments [7]. Paired-end sequencing retains strand information and is more suitable for studies of isoforms and novel transcript discovery [5] [7].

Short-Read vs. Long-Read Sequencing: Short-read sequencing (50-500 bp) is most common and is typically sufficient for differential expression analysis [4]. Long-read technologies (up to 10 kb) enable sequencing of entire transcripts, improving identification of splicing events and eliminating amplification bias, but have higher error rates and lower sensitivity [7].

Read Length and Depth: Read lengths of ≥50 bp are generally recommended, with longer reads (75-150 bp) providing better mapping across splice junctions [5]. Sequencing depth depends on the application, with 15-60 million reads per sample being typical for most applications [5].

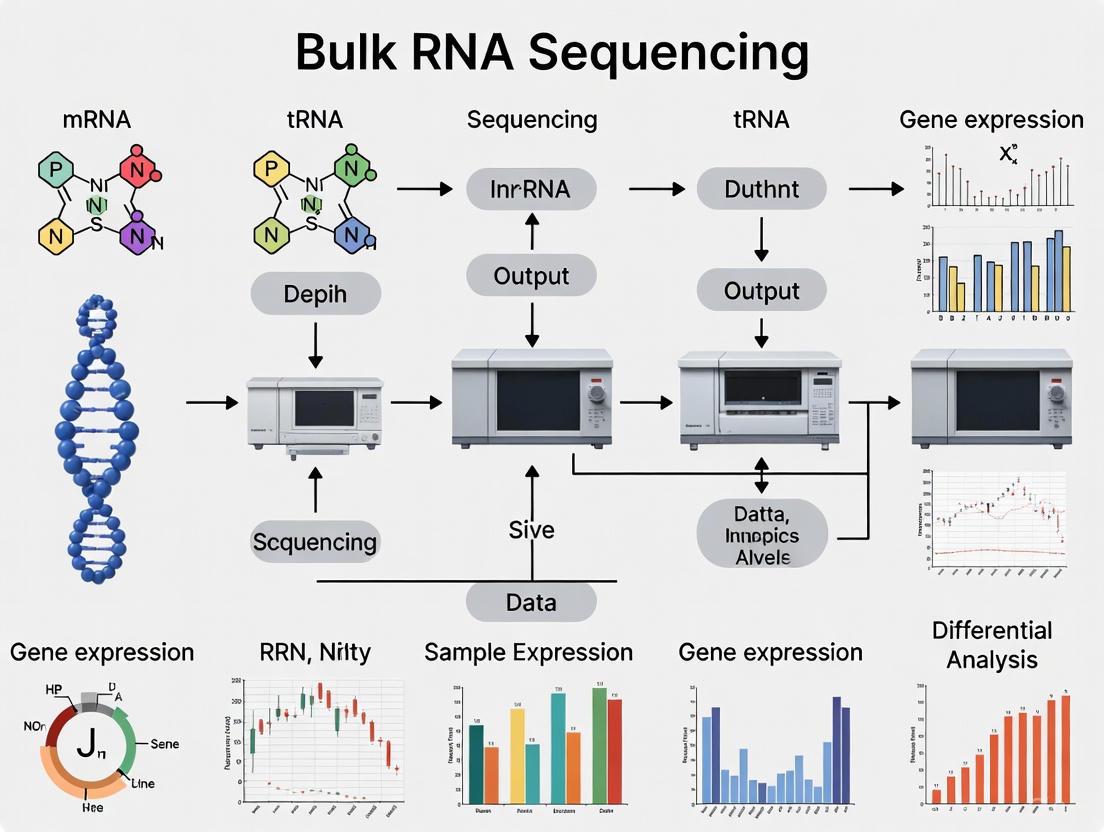

Figure 1: Bulk RNA-seq Computational Workflow. This diagram illustrates the key steps in bulk RNA-seq data analysis, from raw data processing to differential expression analysis.

Data Analysis Pipeline

Quality Control and Read Alignment

The initial phase of bulk RNA-seq data analysis focuses on quality control and read alignment. Raw sequencing data in FASTQ format undergoes quality assessment using tools like FastQC to evaluate read quality, adapter contamination, and overall sequence quality [8] [9]. Following quality control, reads are typically trimmed to remove adapters and low-quality bases using tools such as Trimmomatic [8].

The cleaned reads are then aligned to a reference genome or transcriptome using splice-aware aligners such as STAR or TopHat2 [8] [6]. The alignment step must account for spliced transcripts, as RNA-seq reads often span exon-exon junctions. The choice of reference genome and annotation file (GTF format) significantly impacts alignment rates and downstream analysis [8].

Following alignment, the number of reads mapping to each gene is quantified using tools like HTSeq-count or featureCounts [8] [6]. This generates a count matrix where each row represents a gene and each column represents a sample, with integer values indicating the number of reads assigned to each gene in each sample. This count matrix serves as the input for differential expression analysis.

Differential Expression Analysis

Differential expression analysis identifies genes that show statistically significant expression changes between experimental conditions. The most widely used tools for this analysis include DESeq2 and edgeR, both of which implement statistical methods based on the negative binomial distribution to account for the count nature of RNA-seq data and biological variability [8] [6].

The DESeq2 workflow typically includes [8]:

- Data Pre-filtering: Removing genes with very low counts across all samples

- Normalization: Accounting for differences in sequencing depth and RNA composition between samples

- Dispersion Estimation: Modeling the biological variability within conditions

- Statistical Testing: Using the Wald test or likelihood ratio test to identify differentially expressed genes

- Multiple Testing Correction: Applying false discovery rate (FDR) correction to account for testing thousands of genes simultaneously

The output includes metrics such as log2 fold changes, p-values, and adjusted p-values for each gene, enabling researchers to identify statistically significant expression changes.

Figure 2: Differential Expression Analysis Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps in identifying differentially expressed genes from raw count data.

Data Interpretation and Visualization

Following differential expression analysis, several visualization approaches facilitate biological interpretation:

Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Reduces the high-dimensionality of the expression data while preserving variation, allowing visualization of sample relationships and batch effects [8] [6]. Clear separation between experimental groups in PCA plots suggests strong transcriptomic differences.

Volcano Plots: Display statistical significance versus magnitude of expression change, enabling quick identification of the most biologically relevant differentially expressed genes [9].

Heatmaps: Visualize expression patterns of significant genes across samples, revealing co-regulated genes and sample clusters [9].

Pathway Analysis: Tools for over-representation analysis (ORA) and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) identify biological pathways, molecular functions, and regulatory networks enriched among differentially expressed genes [9].

Automated analysis pipelines such as Searchlight have been developed to streamline the exploration and visualization of bulk RNA-seq data, generating comprehensive statistical analyses and publication-quality figures [9].

Comparative Analysis: Bulk vs. Single-Cell RNA-seq

Technical and Practical Differences

Bulk and single-cell RNA-seq represent complementary approaches with distinct technical considerations and applications. The table below summarizes key differences between these methodologies:

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Bulk RNA-seq vs. Single-Cell RNA-seq

| Parameter | Bulk RNA-seq | Single-Cell RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population average | Single-cell level |

| Sample Input | Pooled cell populations | Single-cell suspensions |

| Cost per Sample | Lower | Higher |

| Sequencing Depth | Higher per sample | Lower per cell |

| Technical Complexity | Lower | Higher |

| Data Complexity | Lower | Higher |

| Ability to Detect Heterogeneity | Limited | Excellent |

| Identification of Rare Cell Types | Masked | Possible |

| Required Cell Viability | Standard | High (>90%) |

| Primary Applications | Differential expression between conditions, biomarker discovery, pathway analysis | Cell type identification, cellular heterogeneity, developmental trajectories, rare cell detection |

Advantages and Limitations

Bulk RNA-seq offers several key advantages that maintain its relevance in the single-cell era. The lower per-sample cost makes it accessible for studies requiring large sample sizes, such as clinical cohorts or time-series experiments [2]. The established protocols and analysis pipelines reduce technical barriers, and the higher sequencing depth per sample improves detection of lowly expressed genes [2]. For many research questions focused on population-level responses rather than cellular heterogeneity, bulk RNA-seq provides the most appropriate and efficient approach [2].

However, bulk RNA-seq has significant limitations, primarily its inability to resolve cellular heterogeneity [2]. By providing an averaged expression profile, it masks differences between cell types or cell states within a sample. This averaging effect can obscure important biological phenomena, particularly in complex tissues with multiple cell types. If a few cells highly express a particular gene while most do not, the bulk measurement may show moderate expression, potentially missing biologically relevant patterns [2].

In practice, bulk and single-cell approaches often work synergistically. For example, bulk RNA-seq can identify overall expression differences between conditions, while single-cell RNA-seq can determine which specific cell types drive these differences [2] [7]. This integrated approach was demonstrated in a 2024 Cancer Cell study where researchers used both methods to identify developmental states driving resistance to chemotherapeutic agents in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia [2].

Bulk RNA-seq remains an essential tool in the transcriptomics arsenal, providing robust, cost-effective population-level gene expression profiling. While emerging single-cell technologies offer unprecedented resolution for exploring cellular heterogeneity, bulk RNA-seq continues to offer distinct advantages for many research scenarios, particularly those requiring large sample sizes, detection of lowly expressed genes, or population-level insights. The methodological maturity, established analytical frameworks, and cost-effectiveness of bulk RNA-seq ensure its continued relevance in basic research, biomarker discovery, and drug development. As transcriptomic technologies evolve, the integration of bulk and single-cell approaches will likely provide the most comprehensive understanding of biological systems, leveraging the respective strengths of each method to address diverse research questions across biological and biomedical disciplines.

Bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) is a powerful, high-throughput technique that enables researchers to measure gene expression across the entire transcriptome for a given sample. By capturing the average expression profile from a pool of cells, it provides critical insights into cellular states, responses to stimuli, and disease mechanisms. This foundational technology has become indispensable in biomedical research and drug development, supporting activities from biomarker discovery to understanding therapeutic mechanisms of action. The workflow, from biological sample to interpretable sequence data, involves a series of coordinated experimental and computational steps that transform raw RNA into quantitative biological insights [10] [11]. This guide details the key stages of the bulk RNA-seq pipeline, providing both experimental protocols and analytical frameworks essential for generating robust, reproducible data.

Experimental Workflow: From Sample to Library

The initial phase of any bulk RNA-seq study involves careful sample preparation and processing to ensure the integrity and quality of the resulting data.

Sample Collection and RNA Extraction

The process begins with the collection of biological material, which can range from tissues and whole organisms to cultured cells or blood samples. A critical first step is the immediate stabilization of RNA within these samples to prevent degradation, typically achieved through flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen or using commercial RNA stabilization reagents. Total RNA is then extracted using methods designed to maintain integrity, such as column-based kits or phenol-chloroform extraction. The quality of the extracted RNA is rigorously assessed prior to proceeding, with instruments like the Agilent Bioanalyzer providing RNA Integrity Number (RIN) scores; samples with RIN values greater than 8 are generally considered suitable for sequencing [12] [8].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Library preparation converts the purified RNA into a format compatible with sequencing platforms. For standard mRNA sequencing, this typically involves:

- rRNA Depletion or Poly-A Selection: To enrich for biologically informative messenger RNA (mRNA), ribosomal RNA (rRNA)—which constitutes over 80% of total RNA—is either removed using target probes (ribo-depletion) or mRNA is selectively captured using poly-dT beads that bind the poly-A tails [10].

- Fragmentation and cDNA Synthesis: The enriched RNA is fragmented into uniform pieces and reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA). The fragmentation step can occur either before or after cDNA synthesis.

- Adapter Ligation: Sequencing adapters, which contain sequences necessary for binding to the flow cell and incorporating sample indexes (barcodes), are ligated to the cDNA fragments. These barcodes enable the multiplexing of multiple samples in a single sequencing run [11].

The final prepared libraries are quantified and qualified before being loaded onto a next-generation sequencing platform, such as an Illumina HiSeq or NovaSeq system, to generate raw sequencing reads. The use of paired-end reads (e.g., 2x150 bp) is strongly recommended over single-end layouts, as it provides more robust alignment and expression estimates [13].

Computational Analysis Workflow

The transformation of raw sequencing data into biological insights requires a multi-step computational pipeline. The overarching workflow, from raw reads to functional interpretation, is summarized below.

Step 1: Quality Control and Read Trimming

The initial computational step involves assessing the quality of the raw sequencing data (FASTQ files) using tools like FastQC [12] [11]. This evaluation checks parameters such as per-base sequence quality, adapter contamination, and overall read composition. Based on this assessment, reads are often processed through trimming tools like Trimmomatic or Cutadapt to remove adapter sequences, low-quality nucleotides (typically with Phred scores < 20), and very short reads (e.g., < 50 bp) [12] [8]. This non-aggressive trimming improves the subsequent mapping rate without introducing unpredictable changes in gene expression [12].

Step 2: Read Alignment and Quantification

Trimmed reads are then aligned to a reference genome or transcriptome. This step is computationally intensive and requires a splice-aware aligner to account for intron-exon junctions. The STAR aligner is widely used for this purpose due to its accuracy and speed [13] [8] [11]. An alternative, faster approach is "pseudo-alignment" with tools like Salmon or kallisto, which probabilistically determine a read's transcript of origin without performing base-level alignment [13] [11].

Following alignment, the reads assigned to each gene or transcript are counted to create a count matrix, where rows represent features (genes/transcripts) and columns represent samples. This summarization step relies on an annotation file (e.g., in GTF or GFF format from sources like GENCODE or Ensembl) and can be performed by tools such as featureCounts or HTSeq-count [8] [11]. The final output is a gene-level count matrix that serves as the primary input for differential expression analysis.

Step 3: Differential Expression and Functional Analysis

Differential expression (DE) analysis identifies genes whose expression levels significantly differ between experimental conditions (e.g., treated vs. control). This step accounts for biological variation and the discrete nature of count data. Tools like DESeq2 and limma are standard for this analysis, as they model count data using a negative binomial distribution and internally correct for differences in library size [13] [8]. The output includes statistical measures such as log2 fold-change, p-values, and adjusted p-values (q-values) to control the false discovery rate (FDR) arising from multiple testing.

Subsequent functional enrichment analysis (e.g., Gene Ontology, KEGG pathways) is then performed on the list of differentially expressed genes to identify biological processes, molecular functions, and pathways that are perturbed under the conditions studied, thereby translating gene lists into actionable biological insights [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

A successful bulk RNA-seq experiment relies on a suite of specialized reagents, materials, and computational resources. The table below catalogues the key components required throughout the workflow.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Bulk RNA-seq

| Item | Function/Description | Example Kits/Tools |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization Reagent | Preserves RNA integrity immediately after sample collection to prevent degradation. | RNAlater, TRIzol |

| Total RNA Extraction Kit | Isolates high-quality total RNA from cells or tissues; includes lysis buffers and purification columns. | RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (QIAGEN) [12] |

| rRNA Depletion Kit | Selectively removes abundant ribosomal RNA to enrich for coding and non-coding RNA. | Ribo-Zero Plus, NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit |

| Poly-A Selection Beads | Enriches for messenger RNA (mRNA) by binding to poly-adenylated tails. | Poly(A) Purist MagBead Kit (Thermo Fisher) |

| Strand-Specific RNA Library Prep Kit | Converts RNA into a sequencing-ready library; includes fragmentation, cDNA synthesis, and adapter ligation steps. | TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Kit (Illumina) [12] |

| Sequence Alignment Software | Maps sequencing reads to a reference genome, accounting for splice junctions. | STAR [13] [8], HISAT2 |

| Quantification Tool | Assigns aligned reads to genomic features (genes/transcripts) to generate a count matrix. | featureCounts [11], HTSeq-count [8], Salmon [13] |

| Differential Expression Package | Performs statistical testing to identify genes with significant expression changes between conditions. | DESeq2 [8], limma [13] |

Performance Comparison of Bioinformatics Tools

The choice of algorithms at each computational stage can significantly impact the final results. A systematic comparison of 192 alternative pipelines highlighted substantial variation in performance, underscoring the importance of tool selection [12]. The following table synthesizes key findings and common tool options.

Table 2: Selected Bioinformatics Tools and Performance Considerations for Bulk RNA-seq Analysis

| Analysis Step | Common Tools | Performance & Selection Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Trimming | Trimmomatic, Cutadapt, BBDuk | Aggressive trimming can alter gene expression; non-aggressive use is recommended (Phred >20, length >50bp) [12]. |

| Alignment | STAR, HISAT2, Bowtie2 | STAR is a widely used, accurate splice-aware aligner. Pseudo-aligners like Salmon offer a faster alternative for quantification [13] [11]. |

| Quantification | featureCounts, HTSeq-count, Salmon, kallisto | Alignment-based (featureCounts) and pseudo-alignment (Salmon) methods are both established. The nf-core/rnaseq workflow uses a hybrid STAR-Salmon approach [13]. |

| Differential Expression | DESeq2, limma, edgeR | DESeq2 is a common choice for its robust statistical modeling of count data. Performance varies, and validation with qRT-PCR is advised [12] [8]. |

The bulk RNA-seq workflow represents a sophisticated integration of molecular biology and computational analysis. From meticulous sample preparation to rigorous statistical testing, each step is critical for generating accurate and biologically meaningful data. Adherence to standardized protocols, such as those provided by the GeneLab consortium [10], and the use of validated, reproducible computational pipelines, such as the nf-core/RNAseq workflow [13], are paramount for success. As this technology continues to be a cornerstone of functional genomics, a deep understanding of its principles and practices empowers researchers and drug development professionals to reliably uncover the transcriptional dynamics underlying health, disease, and therapeutic intervention.

In the field of transcriptomics, bulk RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq) has emerged as a foundational method for measuring the expression levels of thousands of genes simultaneously in a sample containing a mixture of cells, providing an averaged expression profile across a population [2] [3]. The accuracy of alignment and quantification methods for processing this data significantly impacts downstream analyses, including differential expression analysis, functional annotation, and pathway analysis [14]. The process of converting raw sequencing data into meaningful gene expression measurements involves navigating two primary levels of uncertainty: identifying the most likely transcript of origin for each RNA-seq read, and converting these read assignments into a count matrix that reliably represents abundance [13]. Two distinct computational approaches have been developed to address these challenges: traditional sequence alignment and modern pseudoalignment. This technical guide examines these methodologies through the lens of two representative tools: STAR (alignment-based) and Salmon/Kallisto (pseudoalignment-based), providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for selecting and implementing these approaches in bulk RNA-seq studies.

Core Principles: Alignment vs. Pseudoalignment

Traditional Sequence Alignment

Traditional sequence alignment involves mapping sequencing reads to a reference genome or transcriptome using a splice-aware aligner that accommodates gaps due to introns [14] [13]. STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) employs this approach, performing exact base-by-base alignment to identify precise genomic coordinates for each read, including exon-intron boundaries [14] [15]. This method generates comprehensive alignment files (SAM/BAM format) that record exact coordinates of sequence matches, mismatches, and structural variations [13]. The alignment process is computationally intensive but provides valuable data for quality control and the identification of novel splice junctions, fusion genes, and genetic variants [14] [16]. The final output of this approach is typically a table of read counts for each gene in the sample [14].

Pseudoalignment Approach

Pseudoalignment represents a paradigm shift in RNA-seq quantification, focusing on determining transcript compatibility rather than exact base-level alignment [13]. Tools like Salmon and Kallisto use this lightweight approach to rapidly determine the abundance of transcripts by assessing which transcripts a read is compatible with, without performing computationally expensive base-by-base alignment [15] [13]. These methods leverage algorithmic innovations using k-mer matching and probabilistic models to estimate transcript abundances while accounting for uncertainty in read assignments [13]. The pseudoalignment approach is substantially faster and more memory-efficient than traditional alignment, making it particularly suitable for large-scale studies with thousands of samples [14] [13]. Kallisto, for instance, uses a pseudoalignment algorithm to determine transcript abundance and generates both transcripts per million (TPM) and estimated counts as final outputs [14].

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Alignment and Pseudoalignment Approaches

| Feature | Alignment (STAR) | Pseudoalignment (Salmon/Kallisto) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Algorithm | Base-by-base alignment to genome | k-mer matching to transcriptome |

| Computational Demand | High memory and processing requirements | Lightweight and memory-efficient |

| Primary Output | Read counts per gene; BAM alignment files | Transcript abundance estimates (TPM, counts) |

| Handling of Uncertainty | Often discards or arbitrarily assigns multimapping reads | Probabilistic modeling of read assignment uncertainty |

| Speed | Slower due to alignment complexity | Significantly faster (orders of magnitude) |

| Additional Applications | Enables novel splice junction discovery, fusion detection | Primarily focused on expression quantification |

Technical Implementation and Workflows

STAR Alignment Workflow

The STAR workflow begins with preprocessing steps including quality control using tools like FastQC and read trimming with tools like Trimmomatic or Cutadapt to remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases [15]. The core alignment process involves mapping reads to a reference genome using STAR's splice-aware algorithm, which employs a sequential maximum mappable seed search followed by seed clustering and stitching [15]. This process identifies splice junctions and generates comprehensive alignment maps in BAM format [13]. Post-alignment quality control is performed using tools like SAMtools, Qualimap, or Picard to remove poorly aligned reads and address PCR duplicates [15]. The final quantification step involves counting reads that map to genomic features using tools like featureCounts or HTSeq-count, producing a raw count matrix for differential expression analysis [15].

Salmon Pseudoalignment Workflow

Salmon can operate in two modes: pure pseudoalignment directly from FASTQ files, or alignment-based mode using BAM files from STAR as input [13]. The pure pseudoalignment mode uses selective alignment against a transcriptome index, bypassing traditional alignment entirely [13]. Salmon incorporates sophisticated bias correction models that account for sequence-specific, GC-content, and positional biases during quantification [13]. The tool employs an expectation-maximization algorithm to resolve read assignment ambiguity, particularly for reads that map to multiple transcripts or genes with alternative splicing [13]. Unlike alignment-based approaches, Salmon directly outputs transcript-level abundance estimates in TPM format, which can be aggregated to gene-level counts for differential expression analysis [13].

Hybrid Approach: STAR with Salmon Quantification

A recommended hybrid approach leverages the strengths of both methods by using STAR for initial alignment and quality control, followed by Salmon for quantification [13]. In this workflow, STAR performs splice-aware alignment to the genome, generating BAM files suitable for comprehensive quality assessment [13]. These alignments are then projected onto the transcriptome and provided to Salmon, which performs its advanced quantification using alignment information while modeling uncertainty in read assignments [13]. This approach facilitates the generation of comprehensive QC metrics while leveraging Salmon's statistical power for accurate quantification, providing the benefits of both methodologies [13]. The nf-core RNA-seq workflow implements this hybrid approach automatically, generating both alignment-based QC metrics and Salmon quantification results [13].

Diagram 1: RNA-seq Quantification Workflow Comparison

Performance Comparison and Experimental Considerations

Computational Resource Requirements

STAR demands substantial computational resources, particularly during the indexing phase where it requires approximately 30GB of RAM for the human genome [17]. During alignment, STAR can utilize significant memory and processing power, often necessitating high-performance computing clusters or cloud-based solutions for large datasets [17] [13]. Recent optimizations in cloud-based implementations have demonstrated that workflow optimizations can reduce total alignment time by up to 23% through techniques like early stopping and appropriate instance selection [17]. In contrast, Salmon and Kallisto are designed for efficiency, with significantly lower memory footprints and faster processing times, enabling analysis on standard desktop computers even for large datasets [14] [13]. This efficiency makes pseudoalignment tools particularly suitable for large-scale studies with hundreds or thousands of samples [14].

Accuracy and Quantitative Performance

Systematic comparisons of RNA-seq procedures have demonstrated that both alignment and pseudoalignment methods can provide accurate gene expression measurements when properly implemented [12]. Studies comparing 192 alternative methodological pipelines found that quantification accuracy depends on the specific combination of tools and their application to particular experimental contexts [12]. For standard differential gene expression analysis, both approaches show high agreement with qRT-PCR validation data when appropriate normalization methods are applied [12]. However, important differences emerge in specific scenarios: STAR's alignment-based approach may provide more reliable detection of novel splice junctions and genetic variants, while Salmon's bias correction models can improve accuracy in contexts with strong sequence-specific biases [13] [16].

Table 2: Performance Comparison Under Different Experimental Conditions

| Experimental Factor | Impact on STAR (Alignment) | Impact on Salmon/Kallisto (Pseudoalignment) |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | Computationally challenging for large studies (100+ samples) | Well-suited for large-scale studies with many samples |

| Transcriptome Completeness | Better for incomplete transcriptomes or novel isoform discovery | Requires well-annotated transcriptome for optimal performance |

| Read Length | More suitable for longer read lengths | Performs well with short read lengths |

| Library Complexity | Preferred for highly complex libraries | Suitable for standard complexity libraries |

| Sequencing Depth | Better suited for high sequencing depth | Less sensitive to sequencing depth variations |

| Computational Resources | Requires high memory and processing power | Runs efficiently on standard desktop computers |

Experimental Design and Protocol Implementation

Recommended Best-Practice Protocol

For most bulk RNA-seq studies, a hybrid approach using STAR for alignment and quality control, coupled with Salmon for quantification, represents current best practice [13]. The nf-core RNA-seq workflow provides a standardized implementation of this approach, automating the process from raw FASTQ files to final count matrices [13]. The protocol begins with sample preparation using validated library preparation methods such as TruSeq Stranded Total RNA, ensuring library quality and appropriate strand specificity [4] [12]. For data analysis, the workflow requires a sample sheet in nf-core format, a reference genome FASTA file, and annotation in GTF/GFF format [13]. Critical parameters include specifying correct strandedness (preferably using "auto" detection), using paired-end reads for more robust expression estimates, and setting appropriate sequencing depth (typically 20-30 million reads per sample for standard differential expression analysis) [15] [13].

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Bulk RNA-seq Experiments

| Item | Function/Application | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation Kit | Extraction of high-quality RNA from samples | Include DNase treatment to remove genomic DNA contamination [4] |

| Stranded RNA Library Prep Kit | Preparation of sequencing libraries | TruSeq or similar; enables strand-specific information [12] |

| Quality Control Instruments | Assessment of RNA and library quality | Bioanalyzer for RNA Integrity Number (RIN) assessment [12] |

| Reference Genome FASTA | Alignment reference | Species-specific genome sequence from ENSEMBL or UCSC [13] |

| Annotation File (GTF/GFF) | Genomic feature coordinates | Matching version for reference genome [13] |

| Spike-in Control RNAs | Normalization and quality assessment | ERCC or SIRV controls for quantification accuracy [16] [12] |

| High-Performance Computing | Data processing and analysis | HPC cluster or cloud computing for alignment steps [17] [13] |

Applications in Drug Development and Biomedical Research

In pharmaceutical and clinical research contexts, the choice between alignment and pseudoalignment approaches depends on the specific application requirements [14]. For differential gene expression analysis in drug response studies, pseudoalignment tools like Salmon and Kallisto offer sufficient accuracy with dramatically reduced computational requirements, enabling rapid analysis of large clinical cohorts [14] [3]. For biomarker discovery, bulk RNA-seq can identify expression signatures linked to specific diseases or treatments, with alignment-based approaches providing additional validation through inspection of splice junctions and novel transcripts [14] [3]. In characterizing complex tissues, such as tumor microenvironments, the hybrid approach enables both comprehensive quality assessment and accurate quantification, supporting the identification of cell-type-specific expression patterns through deconvolution methods [2] [3].

The integration of bulk RNA-seq data into drug development pipelines has proven valuable for identifying mechanisms of drug action, discovering predictive biomarkers, and understanding resistance mechanisms [14] [2]. For example, in a study of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), researchers leveraged both bulk and single-cell RNA-seq to identify developmental states driving resistance and sensitivity to the chemotherapeutic agent asparaginase [2]. Such applications highlight the continued relevance of bulk RNA-seq in biomedical research, particularly when combined with appropriate quantification methods that ensure data quality and analytical accuracy.

The choice between alignment-based tools like STAR and pseudoalignment tools like Salmon represents a fundamental decision in bulk RNA-seq experimental design, with significant implications for computational requirements, analytical capabilities, and downstream applications. Alignment approaches provide comprehensive data for quality assessment and enable discovery of novel transcriptional events, while pseudoalignment methods offer exceptional efficiency for large-scale quantification studies. The hybrid approach, leveraging STAR for alignment and quality control followed by Salmon for quantification, represents a robust best-practice framework that balances these considerations. As RNA-seq technologies continue to evolve, including the emergence of long-read sequencing platforms [16], the principles underlying these quantification methods will remain essential for extracting biologically meaningful insights from transcriptomic data in both basic research and drug development contexts.

In bulk RNA sequencing, the transformation of raw sequencing data into a gene count matrix represents a critical computational step that bridges experimental wet-lab procedures and statistical inference for biological discovery. This quantifiable table, where rows correspond to genes and columns to samples, serves as the fundamental input for downstream analyses, including the identification of differentially expressed genes. This technical guide explores the biological significance, generation methodologies, quality assessment protocols, and analytical applications of count matrices, with particular emphasis on their growing utility in pharmaceutical research and development for uncovering disease mechanisms, identifying therapeutic targets, and evaluating drug efficacy and toxicity.

Bulk RNA-seq involves generating estimates of gene expression for samples consisting of large pools of cells, for example, a section of tissue, an aliquot of blood, or a collection of cells of particular interest [13]. The analytical process converts raw sequencing data into a structured gene count matrix that quantifies expression levels across all detected genes for each sample in the study. This matrix serves as the primary data source for statistical testing to identify genes or molecular pathways that are differentially expressed between biological conditions [18]. The reliability of subsequent biological conclusions depends critically on the accuracy and quality of this quantification step, making it essential for researchers to understand its principles, generation methods, and quality assessment protocols.

In pharmaceutical contexts, transcriptome profiling through RNA-seq has become invaluable for understanding disease mechanisms, identifying biomarkers, and evaluating therapeutic interventions [19]. The count matrix enables researchers to detect differentially expressed transcripts that may reveal new molecular mechanisms of disease—an important prerequisite for developing new drug targets [19]. This technical guide examines the core components of expression quantification, providing researchers with the foundational knowledge necessary to implement robust analytical pipelines and interpret their results within the framework of drug discovery and development.

The Count Matrix: Structure and Biological Significance

Fundamental Architecture

A count matrix is structured as a two-dimensional table where rows typically represent genes or transcripts, and columns represent individual samples or experimental conditions. Each cell in the matrix contains an integer value representing the abundance of a specific gene in a particular sample. These values are derived from the number of sequencing reads that align to each gene feature, with sophisticated statistical approaches employed to account for biases such as gene length, sequencing depth, and transcript complexity [13].

The ENCODE Consortium's Bulk RNA-seq pipeline produces gene quantification files in a standardized tab-separated value (TSV) format that includes multiple expression measures beyond raw counts [20]. These comprehensive outputs include:

- Column 1: gene_id

- Column 2: transcript_id(s)

- Column 3: length

- Column 4: effective_length

- Column 5: expected_count

- Column 6: TPM (transcripts per million)

- Column 7: FPKM (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million)

- Column 8: posteriormeancount

- Column 9: posteriorstandarddeviationofcount

- Column 10: pme_TPM

- Column 11: pme_FPKM

- Column 12: TPMcilower_bound

- Column 13: TPMciupper_bound

- Column 14: FPKMcilower_bound

- Column 15: FPKMciupper_bound [20]

Quantitative Measures in Gene Expression

Different metrics in the quantification output provide complementary information about gene expression levels:

Table 1: Key Expression Metrics in RNA-seq Quantification

| Metric | Calculation | Application | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Counts | Direct read assignments to genes | Differential expression analysis | Simple interpretation; required input for statistical tools like DESeq2, edgeR | Not comparable between genes without normalization |

| TPM | Reads per kilobase of transcript per million reads mapped | Sample-to-sample gene expression comparison | Corrects for gene length and sequencing depth; sum to 1 million per sample | Sensitive to expression structure of the sample |

| FPKM | Fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped | Single-sample gene expression assessment | Similar to TPM but calculated differently | Not comparable between samples due to compositional differences |

The raw count data serves as the fundamental input for most differential expression analysis tools, as these integer values preserve the statistical properties required by negative binomial models implemented in packages such as DESeq2 and edgeR [6]. The normalization of these raw counts is an essential prerequisite for meaningful sample comparisons, as it accounts for technical variations in sequencing depth and compositional biases [18].

Generation of Expression Quantification: Methodological Approaches

Computational Workflow for Quantification

The process of converting raw sequencing reads (in FASTQ format) into a count matrix involves multiple computational steps with several methodological options at each stage. The workflow encompasses quality assessment, read alignment or pseudoalignment, and gene-level quantification, with variations depending on the reference genome availability and analysis objectives.

Addressing Uncertainty in Read Assignment

The process of converting RNA-seq reads into a count matrix must account for two significant levels of uncertainty. The first involves identifying the most likely transcript of origin for each read, which is complicated by shared genomic segments among alternatively spliced transcripts within a gene. The second concerns the conversion of read assignments to count values in a way that properly models the uncertainty inherent in many read assignments [13].

Two primary approaches have been developed to address these challenges:

Alignment-Based Approaches: These involve formal alignment of sequencing reads to either a genome or a set of transcripts derived from genome annotation. Splice-aware aligners like STAR are used for genome alignment, while tools like Bowtie2 can map reads directly to transcript sequences. The resulting SAM/BAM files record exact coordinates of sequence matches, mismatches, and structural variations [13].

Pseudoalignment Approaches: Motivated by scalability concerns with traditional alignment, pseudoalignment uses substring matching to probabilistically determine locus of origin without base-level precision. Tools such as Salmon and Kallisto employ this approach, simultaneously addressing both levels of uncertainty while offering significantly faster processing times [13].

A recommended hybrid approach utilizes STAR to align reads to the genome, facilitating comprehensive quality control metrics, followed by Salmon in alignment-based mode to perform expression quantification leveraging its statistical models for handling uncertainty [13]. This strategy balances the need for rigorous quality assessment with robust quantification.

Standardized Processing Pipelines

Reproducible analysis pipelines have been developed to standardize the processing of bulk RNA-seq data. The ENCODE Consortium's Bulk RNA-seq pipeline represents one such standardized approach, which can process both paired-end and single-end libraries, with support for strand-specific and non-strand-specific protocols [20]. This pipeline employs STAR for read alignment and RSEM (RNA-Seq by Expectation Maximization) for quantification, generating both gene and transcript-level expression estimates [20].

Similarly, the nf-core RNA-seq workflow from the Nextflow nf-core project provides a comprehensive, portable analysis pipeline that automates the multiple steps of data preparation [13]. The "STAR-salmon" option within this workflow performs spliced alignment to the genome with STAR, projects those alignments onto the transcriptome, and performs alignment-based quantification with Salmon, producing both gene and isoform-level count matrices [13].

Table 2: Comparison of RNA-seq Analysis Pipelines

| Pipeline | Alignment Tool | Quantification Tool | Outputs | Quality Controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENCODE Bulk RNA-seq | STAR | RSEM | Gene/transcript quantifications, normalized signals | Mapping statistics, Spearman correlation between replicates |

| nf-core/rnaseq | STAR | Salmon | Gene/transcript count matrices, multiple QC metrics | Comprehensive MultiQC reports, alignment statistics |

| Prime-seq | Custom alignment | UMI-based counting | 3' tagged libraries with intronic reads | DNase treatment verification, UMI duplication metrics |

Quality Assessment and Validation

Quality Control Checkpoints

Rigorous quality control is essential at multiple stages of RNA-seq data processing to ensure the reliability of the resulting count matrix. Key checkpoints include:

Raw Read Quality: Assessment of sequence quality, GC content, adapter contamination, and overrepresented k-mers using tools like FastQC, Falco, or NGSQC. Sequences may require trimming of low-quality bases or adapter sequences using tools like Trimmomatic or Cutadapt [18] [21].

Alignment Metrics: Evaluation of the percentage of mapped reads, which typically ranges between 70-90% for human RNA-seq data, with significant deviations suggesting potential issues with sequencing accuracy or sample contamination. Additional alignment metrics include uniformity of read coverage across exons, strand specificity, and GC content of mapped reads, assessable with tools like Picard, RSeQC, or Qualimap [21].

Quantification Assessment: Following count generation, evaluation of GC content and gene length biases helps determine appropriate normalization methods. For well-annotated transcriptomes, researchers should analyze the biotype composition of the sample, which indicates RNA purification quality, with minimal ribosomal RNA contamination expected in successful mRNA enrichment [21].

Experimental Standards and Replicate Concordance

The ENCODE Consortium has established rigorous standards for bulk RNA-seq experiments to ensure data quality and reproducibility. These standards include:

Minimum Sequencing Depth: 20-30 million aligned reads per sample, with higher depths required for detecting low-abundance transcripts [20].

Experimental Replicates: At least two biological replicates, with isogenic replicates demonstrating a Spearman correlation of >0.9 and anisogenic replicates (from different donors) showing >0.8 correlation in gene-level quantification [20].

Library Preparation: Recommendations for poly(A) selection or ribosomal RNA depletion depending on RNA quality, with strand-specific protocols preferred for detecting antisense transcription and overlapping transcripts [21].

Additional quality considerations include the use of spike-in controls, such as the ERCC (External RNA Control Consortium) synthetic RNA mixtures, which create a standard baseline for quantifying RNA expression and assessing technical variation [20]. The integration of these controls at approximately 2% of final mapped reads enables normalization across samples and batches.

Analytical Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

From Count Matrix to Biological Insight

The gene count matrix serves as the foundation for numerous analytical approaches in pharmaceutical research:

Differential Expression Analysis: Statistical identification of genes showing significant expression changes between treatment conditions, disease states, or genetic backgrounds. Linear modeling frameworks like limma or negative binomial-based methods in DESeq2 and edgeR are commonly employed for this purpose [13] [6].

Pathway and Enrichment Analysis: Determination of biological pathways, molecular functions, and cellular compartments significantly overrepresented among differentially expressed genes using gene ontology (GO) and pathway databases like KEGG [18].

Biomarker Discovery: Identification of gene expression signatures correlating with disease progression, treatment response, or patient stratification. RNA-seq has proven particularly valuable in cancer research for discovering biomarkers, including gene fusions, non-coding RNAs, and expression profiles predictive of therapeutic efficacy [19].

Drug Repurposing: Analysis of expression profiles induced by existing drugs to identify potential new therapeutic applications. Transcriptome profiling enables screening for therapeutic targets across different conditions, potentially revealing untapped treatment opportunities [19].

Pharmacogenomics and Therapeutic Applications

In precision medicine, RNA-seq data enhances the interpretation of genetic variants by confirming their expression at the transcript level. While DNA sequencing identifies potential mutations, RNA-seq verifies whether these variants are actually expressed, helping prioritize clinically actionable targets [22]. This approach is particularly valuable for:

Target Validation: Distinguishing expressed mutations with potential functional consequences from silent DNA variants [22].

Fusion Gene Detection: Identifying expressed gene fusions that drive malignancy and represent promising targets for personalized therapies [19].

Resistance Mechanisms: Uncovering genes associated with drug resistance by comparing expression profiles between resistant and sensitive cell lines or patient samples [19].

Targeted RNA-seq panels have been developed specifically for clinical applications, such as the Afirma Xpression Atlas (XA) panel, which targets 593 genes covering 905 variants for clinical decision-making in thyroid malignancy management [22]. These targeted approaches provide deeper coverage of clinically relevant genes, improving detection accuracy for rare alleles and low-abundance mutant clones.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Bulk RNA-seq

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(A) Selection Kits | mRNA enrichment from total RNA | Preferred for samples with high RNA integrity; requires minimal degradation |

| Ribosomal Depletion Kits | Removal of abundant rRNA | Essential for bacterial RNA or degraded samples; alternative to poly(A) selection |

| ERCC Spike-in Controls | External RNA controls for normalization | Added at ~2% of final mapped reads; enables technical variance assessment |

| Strand-Specific Library Prep Kits | Preservation of transcript strand information | Critical for antisense transcript detection; dUTP method most common |

| DNase I Treatment Reagents | Genomic DNA removal | Essential for accurate quantification; prevents intronic read contamination |

| UMI Adapters | Unique Molecular Identifiers | PCR duplicate identification; especially valuable for low-input protocols |

| Prime-seq Reagents | Early barcoding bulk RNA-seq | Cost-efficient alternative to commercial kits; 50-fold cheaper library costs |

Experimental Protocols: Best Practices for Reliable Quantification

Sample Preparation and Library Construction

A successful RNA-seq experiment begins with appropriate sample handling and library preparation:

RNA Extraction and Quality Control: Isolate high-quality RNA using methods appropriate for the starting material (cells, tissues, or biofluids). Assess RNA integrity using methods such as RIN (RNA Integrity Number), with values >7.0 generally recommended for poly(A) selection protocols [6].

Library Type Selection: Choose between poly(A) selection and ribosomal depletion based on RNA quality and research objectives. Poly(A) selection is preferable for high-quality mRNA focusing on protein-coding genes, while ribosomal depletion preserves non-polyadenylated transcripts and is more tolerant of degraded samples [21].

Strand-Specific Protocol Implementation: Employ strand-preserving methods (e.g., dUTP-based protocols) to maintain information about the transcribed strand, which is particularly valuable for identifying antisense transcripts, accurately quantifying overlapping genes, and refining transcript annotation [21].

Spike-in Control Incorporation: Add external RNA controls, such as ERCC spike-ins, during library preparation to monitor technical variance and enable normalization across samples and batches [20].

Computational Analysis Protocol

The nf-core RNA-seq workflow provides a standardized analysis pipeline for converting raw sequencing data into a count matrix:

Input Preparation: Prepare a sample sheet in nf-core format with columns for sample ID, paths to FASTQ files (R1 and R2 for paired-end reads), and strandedness information. The pipeline recommends using "auto" for strandedness to leverage Salmon's auto-detection capability [13].

Reference Genome Preparation: Obtain genome FASTA and annotation GTF files for the target species. For optimal results, use the same genome assembly version that was used during experimental design and read alignment.

Pipeline Execution: Run the nf-core/rnaseq workflow with the "STAR-salmon" option, which performs spliced alignment with STAR, projects alignments to the transcriptome, and performs quantification with Salmon [13].

Output Processing: The workflow generates both transcript and gene-level count matrices, along with comprehensive quality control reports. The gene-level count matrix can be directly imported into R or other statistical environments for differential expression analysis [13].

Quality Assurance Protocol

Implement a multi-tier quality assessment protocol to ensure data reliability:

Pre-alignment Quality Control: Process raw FASTQ files with FastQC or Falco to assess per-base sequence quality, GC content, adapter contamination, and overrepresented sequences. Aggregate results across samples using MultiQC for comparative assessment [18].

Post-alignment Metrics: Evaluate alignment quality using metrics including the percentage of uniquely mapped reads, reads mapping to exonic regions, ribosomal RNA content, and coverage uniformity along transcript bodies [21].

Count Matrix QC: Assess the resulting count matrix for library size distribution, gene detection rates, and sample-to-sample correlations. Identify potential outliers using principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical clustering before proceeding with differential expression analysis [6].

Visualization of the RNA-seq Quantification Workflow

The complete process from raw sequencing data to biological insight involves multiple interconnected steps, with the count matrix serving as the central analytical artifact that enables both qualitative and quantitative assessments of transcriptome composition.

The generation and interpretation of count matrices represent a cornerstone of bulk RNA-seq data analysis, transforming raw sequencing information into quantifiable biological measurements. As transcriptomic approaches continue to evolve, best practices in expression quantification remain essential for ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of research findings, particularly in pharmaceutical applications where conclusions may influence therapeutic development decisions. The ongoing development of more efficient protocols, such as prime-seq with its early barcoding approach and substantial cost savings, promises to enhance the accessibility of robust transcriptomic profiling while maintaining analytical rigor [23]. By adhering to standardized methodologies, implementing comprehensive quality control measures, and selecting appropriate analytical frameworks, researchers can leverage count matrices to uncover meaningful biological insights with confidence, advancing both basic science and translational applications in drug discovery and development.

In the field of transcriptomics, researchers are perpetually confronted with a fundamental trade-off: the choice between the cost-effective, population-averaged view provided by bulk RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq) and the high-resolution, cell-specific insights from single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), which comes at a higher cost. This technical guide examines the core principles, advantages, and inherent limitations of these two predominant approaches, with a specific focus on their implications for research and drug development. The decision between these methods is not merely a matter of budget but a strategic consideration that directly influences the biological questions one can answer. This document, framed within a broader thesis on bulk RNA sequencing principles and applications, provides a detailed comparison structured to inform the experimental designs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Core Methodological Principles and Workflows

The fundamental difference between bulk and single-cell RNA-seq lies in the initial processing of the biological sample, which dictates the resolution of the resulting data.

Bulk RNA-Seq Workflow

Bulk RNA-seq is a next-generation sequencing (NGS) method to measure the whole transcriptome across a population of thousands to millions of cells [2]. The process begins with a biological sample (e.g., a piece of tissue or cell culture) that is digested to extract RNA, which can be total RNA or enriched for mRNA [2]. This RNA is then converted into cDNA, and processed into a sequencing-ready library, ultimately providing a readout of the average gene expression levels for all cells in the sample [2]. The data represents a composite, averaged transcriptome profile, effectively obscuring cellular heterogeneity.

Single-Cell RNA-Seq Workflow

In contrast, scRNA-seq profiles the whole transcriptome of individual cells [2]. The workflow requires the generation of a viable single-cell suspension from the sample, a critical step that involves enzymatic or mechanical dissociation and rigorous quality control [2] [24]. A key differentiator is the instrument-enabled cell partitioning, where single cells are isolated into individual micro-reaction vessels, such as Gel Beads-in-emulsion (GEMs) on a 10X Genomics Chromium system [2] [24]. Within these vessels, each cell is lysed, and its RNA is captured and barcoded with a cell-specific barcode and a unique molecular identifier (UMI) [2] [24]. This ensures all transcripts from a single cell can be traced back to their origin after sequencing, enabling the reconstruction of individual cell transcriptomes.

The following diagram illustrates the key procedural differences between these two foundational workflows:

Quantitative Comparison: Performance, Cost, and Output

The choice between bulk and single-cell RNA-seq involves balancing multiple technical and financial factors. The table below summarizes the key quantitative and qualitative differences that define their respective advantages and limitations.

Table 1: Key comparative features of Bulk RNA-seq and Single-Cell RNA-seq

| Feature | Bulk RNA-Seq | Single-Cell RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Average of cell population [2] [25] [26] | Individual cell level [2] [25] [26] |

| Cost per Sample | Lower (~1/10th of scRNA-seq) [25] | Higher [2] [25] |

| Cell Heterogeneity Detection | Limited; masks cellular differences [2] [27] [25] | High; reveals distinct subpopulations and rare cells [2] [28] [25] |

| Gene Detection Sensitivity | Higher per sample; detects more genes per sample [25] | Lower per cell; suffers from transcript "dropout" [25] |

| Rare Cell Type Detection | Not possible; signal is diluted [25] | Possible; can identify rare cells within a population [28] [25] [24] |

| Data Complexity | Lower; simpler, established analysis pipelines [2] [25] | Higher; requires specialized computational methods [2] [25] [26] |

| Sample Input Requirement | Higher amount of total RNA [25] | Lower; can work with as little as a single cell [25] |

| Typical Applications | Differential gene expression, biomarker discovery, gene fusion detection [2] [25] | Cell typing, developmental trajectories, tumor heterogeneity, immune profiling [2] [29] [25] |

A significant differentiator is cost. Bulk RNA-seq remains the more economical option, with reported costs around \$300 per sample, while scRNA-seq can range from \$500 to \$2000 per sample [25]. However, the landscape is evolving. Recent advancements like the BOLT-seq protocol aim to drastically reduce the cost of library construction to under \$1.40 per sample (excluding sequencing) by using crude cell lysates and omitting RNA purification steps [30]. Despite this, the total cost of scRNA-seq, including deeper sequencing requirements, generally remains higher than bulk [2].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section outlines two representative experimental protocols, highlighting the key methodological differences.

Protocol for Standard Bulk RNA-Seq Library Preparation

The following steps are adapted from standard protocols using kits such as NEBNext Ultra II [30].

- RNA Extraction & Quality Control: Total RNA is purified from the tissue or cell population using a commercial kit (e.g., RNeasy mini kit). RNA quality is assessed using systems like Agilent TapeStation, with an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 7 generally considered acceptable [30] [31].

- Library Preparation: Typically, 200 ng of purified total RNA is used as input. The protocol involves:

- Reverse Transcription: Conversion of mRNA to cDNA using primers, often oligo(dT) to select for polyadenylated RNA.

- Second-Strand Synthesis: Creation of double-stranded cDNA.

- Tagmentation: Fragmentation of the cDNA and ligation of sequencing adapters, a step utilized in many modern kits.

- PCR Amplification: Limited-cycle PCR to enrich for the final library.

- Sequencing: Libraries are quantified, pooled, and sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq or similar platform.

Protocol for High-Throughput scRNA-Seq (e.g., 10X Genomics)

This protocol is based on the widely used 10X Genomics Chromium platform [2] [24].

- Single-Cell Suspension Preparation:

- Fresh tissue is dissociated using enzymatic (e.g., collagenase) or mechanical methods.

- Cells are filtered and resuspended. Viability and concentration are critical and are assessed using a cell counter (e.g., Countess II). Targets are typically >80% viability and a concentration optimized for the instrument.

- Partitioning and Barcoding on Chromium Controller:

- The cell suspension is loaded onto a Chromium microfluidic chip along with gel beads and reverse transcription (RT) mix.

- The instrument partitions thousands of cells into nanoliter-scale GEMs (Gel Bead-In-Emulsions). Each GEM contains a single cell, a single gel bead, and the RT mix.

- The gel bead dissolves, releasing oligos with a cell barcode (unique to each bead), a UMI (unique to each transcript molecule), and an oligo-dT primer.

- Cells are lysed within the GEMs, and mRNA is captured and reverse-transcribed, barcoding all cDNA from a single cell with the same barcode.

- Library Construction:

- GEMs are broken, and barcoded cDNA is pooled and purified.

- The cDNA is amplified by PCR.

- Enzymatic fragmentation and sample index PCR are performed to add P5 and P7 adapters for Illumina sequencing.

- Sequencing and Data Pre-processing:

- Libraries are sequenced. The data is processed using the Cell Ranger pipeline, which performs demultiplexing, alignment, barcode counting, and UMI counting to generate a cell-by-gene matrix for downstream analysis [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key reagents and materials used in bulk and single-cell RNA-seq workflows

| Item | Function | Example Products/Assays |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization Reagent | Preserves RNA integrity immediately after sample collection, especially critical for blood. | PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes [31] |

| RNA Extraction Kit | Purifies total RNA from cells or tissues; a prerequisite for bulk RNA-seq and RNA quality check for scRNA-seq. | RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) [30] |

| RNA Quality Assessment System | Evaluates RNA integrity (RIN) to ensure sample quality is sufficient for library prep. | Agilent 4150 TapeStation, Bioanalyzer [30] [31] |

| Bulk RNA-Seq Library Prep Kit | Converts purified RNA into a sequencing-ready library. | NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit [30] |

| Single-Cell Partitioning Instrument & Chip | Automates the isolation of single cells into nanoliter-scale reactions for barcoding. | Chromium X Series Instrument & Chips (10X Genomics) [2] |

| Single-Cell 3' Gene Expression Assay | Contains all necessary reagents for GEM formation, barcoding, and library construction on a specific platform. | Chromium Single Cell 3' Gene Expression Kit (10X Genomics) [2] |

| In-House Purified Tn5 Transposase | An enzyme used in cost-effective protocols (e.g., BOLT-seq, BRB-seq) for tagmentation, reducing reliance on commercial kits. | Purified Tn5 transposase [30] |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

The strategic choice between bulk and single-cell RNA-seq significantly impacts various stages of the drug discovery pipeline, from target identification to clinical trials.

Target Identification and Validation

- Bulk RNA-seq is highly effective for differential gene expression analysis, comparing diseased versus healthy tissues to identify genes that are consistently upregulated or downregulated, thus revealing potential therapeutic targets [2] [19]. It is also useful for discovering novel transcripts and gene fusions, which can be directly targeted with drugs [2] [24] [19].

- scRNA-seq excels in cell-type-specific target discovery. By revealing which specific cell types within a complex tissue express a disease-linked gene, it improves target credentialing. For instance, a 2024 retrospective analysis showed that drug targets with cell-type-specific expression in disease-relevant tissues were more likely to succeed in early clinical trials [28]. When combined with CRISPR screening (Perturb-seq), scRNA-seq can map the functional impact of gene perturbations across many cell types simultaneously, validating targets and understanding their mechanisms [29] [28].

Biomarker Discovery and Patient Stratification

- Bulk RNA-seq has been historically used to develop RNA-based biomarker signatures for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and patient stratification [2] [24] [19]. However, its averaged profile can lack precision in heterogeneous diseases.

- scRNA-seq defines more accurate biomarkers by accounting for cellular complexity. It can identify rare cell populations, such as a specific subset of CD8+ T cells associated with a positive response to immunotherapy, enabling finer patient stratification and predictive biomarkers [29] [28] [24]. This high-resolution view allows for the development of more precise diagnostic and prognostic models.

Understanding Drug Mechanisms and Toxicity

- Bulk RNA-seq can profile genome-wide changes in gene expression in response to drug treatment, helping to elucidate mechanisms of action (MOA) and identify potential toxicity signatures by comparing treated and untreated samples [19].

- scRNA-seq provides a superior view of heterogeneous drug responses. It can identify rare subpopulations of drug-tolerant or resistant cells that would be masked in a bulk average [29] [24]. Furthermore, it can dissect how a drug remodels the tumor microenvironment, revealing effects on immune and stromal cells that contribute to efficacy or toxicity [29] [24].

The complementary nature of these technologies is powerfully illustrated by a 2024 study on B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), where researchers leveraged both bulk and single-cell RNA-seq to identify developmental states driving resistance and sensitivity to the chemotherapeutic agent asparaginase [2]. This hybrid approach is increasingly common in rigorous, discovery-driven research.