Bulk RNA-Seq for Whole Transcriptome Profiling: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of bulk RNA sequencing for whole transcriptome analysis, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Bulk RNA-Seq for Whole Transcriptome Profiling: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of bulk RNA sequencing for whole transcriptome analysis, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, including how bulk RNA-seq measures average gene expression across cell populations and its key advantages in cost-effectiveness and established analytical pipelines. The guide explores cutting-edge methodologies and clinical applications, from differential expression analysis with DESeq2 to biomarker discovery and therapy guidance. It addresses critical troubleshooting aspects, including normalization challenges posed by transcriptome size variation and solutions for low-quality input. Finally, it examines validation strategies and comparative analyses with emerging technologies like single-cell and spatial transcriptomics, positioning bulk RNA-seq within the modern multi-omics landscape.

Understanding Bulk RNA-Seq: Core Principles and Transcriptome Biology

What is Bulk RNA Sequencing? Defining Population-Averaged Gene Expression

Bulk RNA Sequencing (bulk RNA-seq) is a foundational next-generation sequencing (NGS) method for transcriptome profiling of pooled cell populations, tissue sections, or biopsies [1]. This technique provides a population-averaged readout, measuring the average expression level of individual genes across hundreds to millions of input cells [1] [2]. By capturing the global gene expression profile of a sample, bulk RNA-seq enables researchers to identify expression differences between experimental conditions, such as diseased versus healthy tissues, or treated versus control samples [2] [3]. Unlike later-developed single-cell methods, bulk RNA-seq generates a composite expression profile representing the entire cell population within a sample, making it invaluable for comparative transcriptomics and biomarker discovery [2].

The significance of bulk RNA-seq lies in its ability to provide a comprehensive quantitative overview of the transcriptome during specific developmental stages or physiological conditions [4]. This approach has revolutionized transcriptomics by offering a far more precise measurement of transcript levels and their isoforms compared to previous hybridization-based methods like microarrays [4]. Understanding the transcriptome is essential for interpreting the functional elements of the genome and revealing the molecular constituents of cells and tissues, which has profound implications for understanding development and disease [4].

Key Methodologies and Protocols

Standard Bulk RNA-seq Workflow

The bulk RNA-seq workflow comprises multiple critical steps, from sample preparation to sequencing, each requiring specific protocols and quality controls to ensure reliable data.

Sample Preparation and Library Construction

The process begins with RNA extraction from the biological sample, which could be total RNA or RNA enriched for specific types through poly(A) selection or ribosomal RNA depletion [1] [5]. For mRNA sequencing, Oligo(dT) is often used to enrich mRNA or deplete ribosomal RNA [2]. Assessing RNA quality is crucial before proceeding, commonly evaluated using the RNA Integrity Number (RIN), with a value over six generally considered acceptable for sequencing [5].

Following quality control, the protocol involves:

- Fragmentation of RNA into smaller pieces (200-500 bp) via enzymatic, chemical, or physical means to be compatible with sequencing platforms [4] [5]

- Reverse transcription of RNA into double-stranded cDNA [1] [5]

- Adapter ligation with platform-specific sequences to enable sequencing [4] [5]

- Sample multiplexing using unique barcodes to pool multiple samples together for efficient library preparation [1]

For projects requiring higher sensitivity with limited starting material, methods like CEL-seq2 incorporate unique barcodes to label each sample before pooling, followed by linear amplification via in vitro transcription (IVT) to generate amplified RNA [1].

Sequencing and Data Generation

The prepared libraries are sequenced using high-throughput platforms, with Illumina systems being the most common [2]. Both single-end and paired-end (PE) sequencing approaches are used, with PE recommended for differential expression analysis as it preserves strand information and provides more accurate alignment, especially for isoform studies [6] [5]. The resulting sequences, called "reads," typically range from 30-400 bp depending on the technology used [4].

Computational Analysis Pipeline

Following sequencing, computational analysis transforms raw data into biological insights through multiple processing stages.

Quality Control and Read Alignment

The initial computational steps include:

- Quality checking of sequence data using tools like FastQC to assess completeness, depth, and read quality [7]

- Adapter trimming and quality filtering with tools like Trimmomatic [7]

- Read alignment to a reference genome using splice-aware aligners such as STAR, or alignment to transcriptomes using tools like Bowtie2 [7] [6]

- Pseudoalignment approaches using tools like Salmon or kallisto that provide faster quantification without base-level alignment [6]

For gene-level quantification, alignment files are processed using tools like HTSeq-count to generate count matrices where rows represent genes and columns represent samples [7]. The nf-core/rnaseq workflow provides an automated, reproducible pipeline that integrates these steps, combining STAR alignment with Salmon quantification for optimal results [6].

Differential Expression Analysis

The count matrix serves as input for statistical analysis to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Two widely used tools for this purpose are DESeq2 and limma [7] [6]. DESeq2 employs a negative binomial distribution to model count data and uses the Wald test to identify significant expression changes between conditions [7]. The analysis includes:

- Data normalization to account for differences in sequencing depth between samples [7]

- Statistical testing with multiple testing correction, typically using the Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) to control for false positives [7]

- Effect size estimation using empirical Bayes shrinkage to prevent technical artifacts from inflating fold-change values [7]

Research Applications and Method Selection

Primary Applications of Bulk RNA-seq

Bulk RNA-seq serves multiple research purposes across various biological disciplines, with key applications including:

Differential Gene Expression Analysis: Comparing gene expression profiles between different experimental conditions to identify upregulated or downregulated genes [2] [3]. This application is fundamental for discovering RNA-based biomarkers and molecular signatures for disease diagnosis, prognosis, and stratification [3].

Tissue or Population-level Transcriptomics: Obtaining global expression profiles from whole tissues, organs, or bulk-sorted cell populations [3]. This approach is particularly valuable for large cohort studies, biobank projects, and establishing baseline transcriptomic profiles for new or understudied organisms [3].

Transcriptome Characterization: Identifying and annotating isoforms, non-coding RNAs, alternative splicing events, and gene fusions [4] [3]. Bulk RNA-seq can reveal precise transcription boundaries to single-base resolution and detect sequence variations in transcribed regions [4].

Pathway and Network Analysis: Investigating how sets of genes change collectively under various biological conditions to understand regulatory mechanisms and interactions within biological systems [2].

Table 1: Key Applications of Bulk RNA Sequencing

| Application Area | Specific Use Cases | Typical Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Expression | Disease vs. healthy tissue; Treated vs. control conditions; Time-course experiments | Lists of significantly upregulated/downregulated genes with statistical measures |

| Transcriptome Annotation | Novel transcript discovery; Alternative splicing analysis; Non-coding RNA characterization | Catalog of transcript species; Splicing patterns; Transcription start/end sites |

| Biomarker Discovery | Diagnostic and prognostic marker identification; Patient stratification signatures | Gene expression signatures with predictive value for specific conditions |

| Pathway Analysis | Biological mechanism elucidation; Drug response studies; Systems biology | Enriched pathways; Gene regulatory networks; Co-expression modules |

Comparative Analysis: Bulk RNA-seq vs. Single-Cell RNA-seq

The choice between bulk and single-cell RNA-seq depends on research objectives, budget, and sample characteristics, as each approach offers distinct advantages and limitations.

Table 2: Bulk RNA-seq vs. Single-Cell RNA-seq Comparison

| Aspect | Bulk RNA Sequencing | Single-Cell RNA Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population-averaged gene expression | Individual cell gene expression |

| Sample Input | RNA extracted from cell populations | Viable single-cell suspensions |

| Cost | Relatively low | Higher |

| Data Complexity | Simplified analysis | Complex data requiring specialized analysis |

| Ideal Applications | Differential expression between conditions; Large cohort studies | Cellular heterogeneity; Rare cell populations; Developmental trajectories |

| Limitations | Masks cellular heterogeneity; Cannot identify novel cell types | Higher technical noise; More complex sample preparation |

Bulk RNA-seq provides a cost-effective approach for whole transcriptome analysis with lower sequencing depth requirements and more straightforward data analysis [3]. However, its primary limitation is the inability to resolve cellular heterogeneity, as it averages expression across all cells in a sample [2] [3]. This means bulk RNA-seq cannot identify rare cell types or distinguish whether expression signals originate from all cells or a specific subset [3].

In contrast, single-cell RNA-seq enables resolution of cellular heterogeneity and identification of novel cell types and states, but requires more complex sample preparation, deeper sequencing, and specialized computational analysis [2] [3]. For many research questions, particularly those focused on population-level differences rather than cellular heterogeneity, bulk RNA-seq remains the most practical and informative choice [3].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Successful bulk RNA-seq experiments require specific reagents, tools, and computational resources throughout the workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Bulk RNA-seq

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction & QC | TRIzol; PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit; Qubit; Agilent TapeStation | RNA isolation and quality assessment; Concentration determination |

| Library Preparation | Oligo(dT) beads; rRNA depletion kits; NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit | mRNA enrichment; cDNA synthesis; Adapter ligation |

| Sequencing | Illumina platforms; SOLiD; Roche 454 | High-throughput sequencing of cDNA libraries |

| Alignment & Quantification | STAR; HISAT2; Salmon; kallisto; HTSeq-count | Read alignment to reference; Gene-level quantification |

| Differential Expression | DESeq2; limma; edgeR | Statistical analysis of expression differences |

| Visualization & Interpretation | PCA; Heatmaps; Volcano plots; WGCNA; GSEA | Data exploration; Pattern identification; Biological interpretation |

Key considerations for reagent selection include:

- RNA quality assessment tools are essential, with RIN values >6 recommended for sequencing [5]

- Strand-specific library preparation protocols preserve transcript orientation information, valuable for transcriptome annotation [4]

- Multiplexing barcodes enable efficient processing of multiple samples in a single sequencing run [1]

- Reference genomes and annotation files (GTF/GFF) must match the target organism for accurate alignment and quantification [7] [6]

The integration of these tools within automated workflows, such as the nf-core/rnaseq pipeline, enhances reproducibility and efficiency in bulk RNA-seq analysis [6]. This workflow combines optimal tools at each step, from STAR alignment to Salmon quantification and DESeq2 differential expression analysis, providing researchers with a standardized approach to transcriptome profiling [6].

In bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), the pervasive presence of ribosomal RNA (rRNA)—constituting 80-90% of total RNA—poses a significant challenge to transcriptome analysis [8] [9]. To overcome this, two principal library preparation strategies have been developed: poly(A) enrichment and rRNA depletion. The choice between these methods represents a critical, irreversible decision that determines which RNA molecules enter the sequencing library, directly impacting data quality, experimental cost, and the biological conclusions that can be drawn [8]. Poly(A) enrichment selectively targets polyadenylated transcripts through oligo(dT) hybridization, making it ideal for profiling mature messenger RNAs (mRNAs) in eukaryotes. In contrast, rRNA depletion employs sequence-specific probes to remove abundant rRNAs from total RNA, preserving both polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated RNA species [8] [10]. This application note details the technological features of both methods, providing structured comparisons, detailed protocols, and decision frameworks to guide researchers in selecting the optimal approach for their specific experimental contexts within whole transcriptome profiling research.

Core Principles and Molecular Mechanisms

Poly(A) Enrichment: A Targeted Capture Approach

The poly(A) enrichment method operates on the principle of oligo(dT) hybridization to capture RNAs possessing a poly(A) tail. This process utilizes oligo(dT) primers or probes conjugated to magnetic beads, which selectively bind to the poly(A) tails of mature eukaryotic mRNAs and many long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) [8] [10]. During library preparation, total RNA is incubated with these beads, allowing the poly(A)+ RNAs to hybridize. Subsequent washing steps remove non-polyadenylated RNAs, including the majority of rRNAs, transfer RNAs (tRNAs), and small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs). The captured poly(A)+ RNA is then eluted and serves as the input for downstream library construction [10]. This mechanism effectively enriches for protein-coding transcripts while excluding non-polyadenylated species such as replication-dependent histone mRNAs and many non-coding RNAs [8]. A key consideration is that the efficiency of this capture depends heavily on an intact poly(A) tail, making the method susceptible to performance degradation with RNA samples that are partially degraded or fragmented, as is common with formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples [8] [11].

rRNA Depletion: A Subtraction-Based Strategy

rRNA depletion employs a subtraction-based methodology designed to remove abundant ribosomal RNAs from total RNA, thereby enriching for all other RNA species. This is typically achieved using sequence-specific DNA or LNA (Locked Nucleic Acid) probes that are complementary to the rRNA sequences of the target organism (e.g., 18S and 28S rRNAs in eukaryotes) [8] [9]. These probes hybridize to their target rRNAs, and the resulting probe-rRNA hybrids are subsequently removed from the solution. Removal can be accomplished through several mechanisms, including immobilization on magnetic beads (e.g., streptavidin-beads if the probes are biotinylated) or enzymatic degradation via RNase H, which specifically cleaves RNA in RNA-DNA hybrids [8]. The remaining supernatant, now depleted of rRNA, contains a diverse pool of both poly(A)+ and non-polyadenylated RNAs, including pre-mRNAs, many lncRNAs, histone mRNAs, and some viral RNAs [8] [10]. This method does not rely on the presence of a poly(A) tail, making it notably more resilient when working with fragmented RNA from FFPE or other compromised samples [8] [12].

Comparative Technical Performance and Data Characteristics

The choice between poly(A) enrichment and rRNA depletion profoundly impacts the composition and quality of the resulting sequencing data, influencing everything from read distribution to required sequencing depth and analytical complexity. Understanding these technical differences is paramount for experimental design and data interpretation.

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Poly(A) Enrichment vs. rRNA Depletion

| Performance Metric | Poly(A) Enrichment | rRNA Depletion | Experimental Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usable Exonic Reads | 70-71% [10] | 22-46% [10] | Poly(A) yields more mRNA data per sequencing dollar |

| Sequencing Depth Required | Lower (Baseline) | 50-220% higher [10] | Higher cost for equivalent exonic coverage with depletion |

| Transcript Types Captured | Mature, polyadenylated mRNA | Coding + non-coding RNA (lncRNA, pre-mRNA) [8] [10] | Depletion enables discovery of non-poly(A) transcripts |

| Read Distribution (Bias) | Pronounced 3' bias [8] [11] | More uniform 5'-to-3' coverage [11] | Depletion better for isoform/splice analysis |

| Genomic Feature Mapping | High exonic, low intronic [11] | Lower exonic, high intronic/intergenic [8] [11] | Intronic reads in depletion can indicate nascent transcription |

| Performance with FFPE/Degraded RNA | Poor; strong 3' bias, low yield [8] [12] | Robust; tolerates fragmentation [8] [12] | Depletion is the standard for clinical/archival samples |

| Residual rRNA Content | Very Low [11] | Low, but variable (probe-dependent) [8] [9] | Verify probe match for non-model organisms |

The data characteristics extend beyond simple metrics. Poly(A) selection, by focusing on mature mRNAs, removes most intronic and intergenic sequences, leading to a high fraction of reads mapping to annotated exons. This improves statistical power for gene-level differential expression analysis at a given sequencing depth [8]. In contrast, rRNA depletion retains a broader spectrum of RNA species, resulting in increased intronic and intergenic fractions. While this can initially appear as "noise," this "extra" signal is often biologically informative; for instance, intronic reads can track transcriptional changes, while exonic reads integrate post-transcriptional processing, allowing researchers to separate these regulatory mechanisms when modeled together [8]. Furthermore, a study comparing library protocols for FFPE samples found that rRNA depletion methods (e.g., Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep) can preserve a high percentage of reads mapping to intronic regions (~60%), underscoring their ability to capture pre-mRNA and nascent transcription [12].

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Poly(A) Enrichment and Library Construction

Principle: Utilize oligo(dT)-conjugated magnetic beads to isolate polyadenylated RNA from total RNA [8] [10].

- Starting Material: 10-1000 ng of high-quality total RNA (RIN ≥ 7 or DV200 ≥ 50% is recommended) [8].

- Key Reagents: Oligo(dT) magnetic beads, Binding Buffer, Wash Buffer, Nuclease-free Water.

Procedure: 1. RNA Denaturation: Heat the total RNA sample to 65°C for 2 minutes and immediately place on ice. This disrupts secondary structures. 2. Binding: Combine the denatured RNA with oligo(dT) beads in a high-salt binding buffer. Incubate at room temperature for 5-10 minutes with gentle agitation. The salt condition promotes hybridization between the poly(A) tail and the oligo(dT) matrices. 3. Capture and Wash: Place the tube on a magnetic stand to separate the beads from the supernatant. Carefully remove and discard the supernatant, which contains non-polyadenylated RNA (rRNA, tRNA, etc.). 4. Washing: Wash the bead-bound poly(A)+ RNA twice with a low-salt wash buffer without disturbing the pellet. This step removes weakly associated and non-specifically bound RNAs. 5. Elution: Elute the purified poly(A)+ RNA from the beads using nuclease-free water or Tris buffer by heating to 70-80°C for 2 minutes. 6. Library Construction: Proceed with standard stranded RNA-seq library prep protocols (fragmentation, reverse transcription, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification) using the eluted poly(A)+ RNA as input.

Optimization Note: For challenging samples or non-standard organisms, the beads-to-RNA ratio may require optimization. Recent research on yeast RNA showed that increasing the oligo(dT) beads-to-RNA ratio significantly reduced residual rRNA content, and a second round of enrichment could further improve purity, though at the cost of yield [9].

Protocol for rRNA Depletion and Library Construction

Principle: Use species-specific DNA probes complementary to rRNA to hybridize and remove rRNA from total RNA [8] [12].

- Starting Material: 10-1000 ng of total RNA. Integrity requirements are flexible (compatible with RIN < 7 and FFPE RNA) [8] [12].

- Key Reagents: rRNA-targeted DNA/LNA probes (e.g., Ribo-Zero/Ribo-Gone), Hybridization Buffer, RNase H (optional), Magnetic Beads for capture.

Procedure: 1. Hybridization: Mix total RNA with the biotinylated rRNA-depletion probes in a hybridization buffer. Incubate the mixture at a defined temperature (e.g., 68°C) for 10-30 minutes to allow the probes to bind specifically to their target rRNA sequences. 2. Removal of rRNA-Probe Hybrids: * Bead Capture Method: Add streptavidin-coated magnetic beads to the mixture. Incubate to allow the biotinylated probes (hybridized to rRNA) to bind to the beads. Use a magnetic stand to capture the beads, and transfer the supernatant—now depleted of rRNA—to a new tube [8] [11]. * Enzymatic Digestion Method: After hybridization, add RNase H to the mixture. This enzyme cleaves the RNA strand in RNA-DNA hybrids, specifically digesting the rRNA bound to the DNA probes. The reaction is then cleaned up to remove fragments and enzymes [8]. 3. Clean-up: Purify the rRNA-depleted RNA using a standard RNA clean-up protocol (e.g., ethanol precipitation or solid-phase reversible immobilization beads). 4. Library Construction: The resulting rRNA-depleted RNA (total transcriptome) is used as input for stranded RNA-seq library prep, which typically involves random priming for cDNA synthesis to ensure uniform coverage across transcripts.

Critical Consideration: The efficiency of depletion is highly dependent on the complementarity between the probes and the target rRNA sequences. For non-model organisms, it is crucial to verify probe match, as mismatches can lead to high residual rRNA and wasted sequencing reads [8].

Decision Framework and Application Guidelines

Selecting the appropriate RNA-seq library preparation method is a strategic decision that hinges on three primary filters: the organism, RNA integrity, and the biological question regarding target RNA species [8]. The following structured framework guides this selection process.

Table 2: Method Selection Guide Based on Experimental Context

| Experimental Context | Recommended Method | Rationale | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eukaryotic, High-Quality RNA (RIN ≥8), mRNA Focus | Poly(A) Selection [8] [10] | Maximizes exonic reads & power for differential expression | Coverage skews to 3' if integrity is suboptimal [8] |

| Degraded/FFPE RNA, Clinical Archives | rRNA Depletion [8] [10] [12] | Does not rely on intact poly(A) tails; more robust | Intronic fractions rise; confirm RNA quality (DV200) [12] |

| Prokaryotic Transcriptomics | rRNA Depletion [8] | Poly(A) capture is not appropriate for bacteria | Use species-matched rRNA probes |

| Non-Coding RNA Discovery | rRNA Depletion [8] [10] | Retains non-polyadenylated RNAs (lncRNAs, snoRNAs) | Residual rRNA increases if probes are off-target |

| Need for Nascent Transcription | rRNA Depletion [8] | Captures pre-mRNA and intronic sequences | Model intronic and exonic reads jointly |

| Cost-Sensitive, High-Throughput mRNA Quantification | Poly(A) Selection [10] [13] | Lower sequencing depth required; simpler analysis | 3' mRNA-Seq (e.g., QuantSeq) is a specialized option [13] |

The decision matrix can be further visualized through a simple workflow. It is critical to maintain methodological consistency; once a strategy is chosen for a study, it should be kept constant for all samples to ensure comparability of results [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Kits

Successful implementation of poly(A) enrichment or rRNA depletion requires specific reagent systems. The following table catalogs key solutions and their functions as derived from the literature and commercial platforms.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq Library Preparation

| Reagent / Kit Name | Function | Key Features / Applications | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads [10] [9] | Poly(A)+ RNA selection | Basis of most poly(A) enrichment protocols; available from multiple vendors (e.g., NEB, Invitrogen) | Beads-to-RNA ratio is a key optimization parameter [9] |

| Poly(A)Purist MAG Kit [9] | Poly(A)+ RNA selection | Commercial kit with optimized buffers for purification | |

| Ribo-Zero Plus [12] | rRNA depletion | Used in Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep; effective for FFPE RNA [12] | Shows very low residual rRNA (~0.1%) in studies [12] |

| RiboMinus Kit [9] | rRNA depletion | Uses LNA probes for efficient hybridization and removal | Probe specificity is critical for performance |

| SMARTer Stranded Total RNA-Seq Kit [12] | rRNA depletion & library prep | All-in-one kit; performs well with low RNA input (e.g., FFPE) [12] | Can have higher residual rRNA than other methods; requires deeper sequencing [12] |

| Duplex-Specific Nuclease (DSN) [11] | rRNA depletion | Normalizes transcripts by digesting abundant ds-cDNA (from rRNA) | Can show higher variability and intronic mapping [11] |

| QuantSeq 3' mRNA-Seq Kit [13] | 3'-focused mRNA sequencing | Ultra-high-throughput, cost-effective for gene counting | Ideal for large-scale screening; simpler analysis [13] |

Poly(A) enrichment and rRNA depletion are both powerful but distinct strategies for preparing RNA-seq libraries. Poly(A) enrichment remains the gold standard for efficient, cost-effective profiling of mature mRNA from high-quality eukaryotic samples, delivering a high fraction of usable exonic reads. In contrast, rRNA depletion offers unparalleled flexibility, enabling transcriptome-wide analysis that includes non-coding RNAs, pre-mRNAs, and transcripts from degraded clinical samples or prokaryotes. The decision is not one of superiority but of appropriateness. By carefully considering the organism, sample quality, and biological question—and by leveraging the decision frameworks and protocols outlined herein—researchers can confidently select the optimal method to ensure the success and biological relevance of their whole transcriptome profiling research.

The Biological Significance of Transcriptome Size Variation Across Cell Types

In the field of bulk RNA-seq research, a critical biological variable often overlooked in experimental design and data analysis is transcriptome size—the total number of RNA molecules within an individual cell. Different cell types inherently possess different transcriptome sizes, a feature rooted in their biological identity and function [14] [15]. For instance, a red blood cell, specialized for oxygen transport, predominantly expresses hemoglobin transcripts, whereas a pluripotent stem cell may express thousands of different genes to maintain its undifferentiated state [15]. This variation is not merely a biological curiosity; it presents a substantial challenge for the accurate interpretation of bulk RNA-seq data, which measures the averaged gene expression from a potentially heterogeneous mixture of cells [14].

Traditional bioinformatics practices, particularly normalization methods, frequently operate on the assumption that transcriptome size is constant across cell types. Commonly used techniques like Counts Per Million (CPM) or Counts Per 10 Thousand (CP10K) effectively eliminate technology-derived effects but simultaneously remove the genuine biological variation in transcriptome size [14]. This creates a systematic scaling effect that can distort biological interpretation, especially in experiments involving diverse cell populations, such as those found in complex tissues or the tumor microenvironment [14] [16]. This review details the biological significance of transcriptome size variation and introduces emerging methodologies and tools designed to account for this factor, thereby enhancing the accuracy of bulk RNA-seq analysis.

Biological Foundations and Quantitative Evidence

Transcriptome size variation is a consistent and measurable feature across different cell types. Evidence from comprehensive single-cell atlases, such as those of the mouse and human cortex, confirms that while cells of the same type typically exhibit similar transcriptome sizes, this size can vary significantly—often by multiple folds—across different cell types [14] [17]. For example, an analysis of mouse specimens showed that the average transcriptome size of L5 PT CTX cells was approximately 21.6k in one sample but increased to 31.9k in another, indicating that variation can exist for the same cell type across different specimens or conditions [14].

The biological implications of this diversity are profound. A study profiling 91 cells from five mouse tissues found that pyramidal neurons exhibited significantly greater transcriptome complexity, with an average of 14,964 genes expressed per cell, compared to an average of 7,939 genes in brown adipocytes, cardiomyocytes, and serotonergic neurons [17]. This broad transcriptional repertoire in neurons is thought to underpin their high degree of phenotypic plasticity, a stark contrast to the more specialized and narrower functional repertoire of heart and fat cells [17]. Furthermore, transcriptome diversity, quantified using Shannon entropy, has been identified as a major systematic source of variation in RNA-seq data, strongly correlating with the expression of most genes and often representing the primary component identified by factor analysis tools [18].

Table 1: Documented Transcriptome Size and Complexity Across Mammalian Cell Types

| Cell Type | Tissue/Origin | Key Metric | Approximate Value | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyramidal Neurons | Mouse Cortex/Hippocampus | Number of Expressed Genes [17] | ~15,000 genes/cell | Underpins phenotypic plasticity and complex function. |

| Non-Neuronal Cells (Cardiomyocytes, Brown Adipocytes) | Mouse Heart/Fat | Number of Expressed Genes [17] | ~8,000 genes/cell | Reflects a narrower, more specialized functional role. |

| L5 PT CTX Neurons | Mouse Cortex (Sample I) | Total Transcriptome Size [14] | ~21,600 molecules/cell | Indicates biological variation within a specific cell type across specimens. |

| L5 PT CTX Neurons | Mouse Cortex (Sample II) | Total Transcriptome Size [14] | ~31,900 molecules/cell | Indicates biological variation within a specific cell type across specimens. |

Impact on Bulk RNA-Seq Analysis and Deconvolution

In bulk RNA-seq, the signal is an aggregate from potentially millions of cells. When these cells have intrinsically different transcriptome sizes, standard normalization distorts the true biological picture. The scaling effect introduced by CP10K normalization enlarges the relative expression profile of cell types with smaller transcriptomes and shrinks those with larger ones [14]. This is particularly problematic for cellular deconvolution, the computational process of inferring cell type proportions from bulk RNA-seq data using single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) data as a reference.

When a CP10K-normalized scRNA-seq reference is used for deconvolution, the scaling effect leads to significant inaccuracies. Cell types with smaller true transcriptome sizes, which are often rare cell populations like certain immune cells in a tumor microenvironment, have their proportions systematically underestimated because their expression profiles were artificially inflated during normalization [14] [15]. Furthermore, two other critical issues compound this problem: the gene length effect, where bulk RNA-seq counts are influenced by gene length (an effect absent from UMI-based scRNA-seq), and the expression variance, where the natural variation in gene expression within a cell type is not properly modeled [14]. Failure to address these three issues results in biased deconvolution outcomes that can mislead downstream biological interpretations.

Protocols and Methodologies

Experimental Protocol: Bulk RNA-Seq Library Preparation with BOLT-seq

For large-scale transcriptome profiling where cost and throughput are primary concerns, the BOLT-seq (Bulk transcriptOme profiling of cell Lysate in a single poT) protocol offers a highly scalable and cost-effective solution (estimated at <$1.40 per sample) [19].

1. Principle: BOLT-seq is a 3'-end mRNA-seq method that constructs sequencing libraries directly from crude cell lysates without requiring RNA purification, significantly reducing hands-on time and steps. It uses in-house purified enzymes to further lower costs [19].

2. Reagents and Equipment:

- Cells: Up to 1,000 cells per sample in a 96-well microtiter plate.

- Lysis Buffer: Contains 0.3% IGEPAL CA-630.

- Enzymes: In-house purified M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase and Tn5 Transposase.

- Primers: Anchored oligo(dT)30-P7 RT primer.

- Reaction Buffers: RT-Mix-B, TD-Mix, PCR-Mix.

- Thermal Cycler

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Cell Lysis. Seed cells in a 96-well plate. Wash with DPBS and lyse with 60 µL of lysis buffer. Incubate for 30 minutes with shaking at 800 RPM.

- Step 2: RNA Denaturation. Transfer 6 µL of cell lysate to a PCR tube. Add 1 µL of RT-Mix-A (containing the anchored oligo(dT) RT primer and dNTPs). Incubate at 65°C for 5 minutes, then immediately place on ice for 3 minutes.

- Step 3: Reverse Transcription. Add 7 µL of RT-Mix-B (containing reaction buffer, DTT, PEG8000, RNase inhibitor, and M-MuLV RT). Incubate at 50°C for 60 minutes. Inactivate the reaction at 80°C for 10 minutes. No purification is needed.

- Step 4: Tagmentation. Add 5 µL of TD-Mix (containing reaction buffer, PEG8000, tetraethylene glycol, and Tn5 transposase) to the RNA/DNA hybrid duplexes. Incubate at 55°C for 30 minutes. Stop the reaction by adding 5 µL of 0.2% SDS. No purification is needed.

- Step 5: Gap-Filling and PCR Amplification. Add 25 µL of PCR-Mix (containing HiFi Fidelity Buffer, dNTPs, HiFi HotStart DNA Polymerase, and indexed primers). Perform the following program in a thermal cycler:

- 50°C for 10 minutes (Gap-filling)

- 95°C for 3 minutes (Initial denaturation)

- 18 cycles of: 95°C for 30s, 60°C for 30s, 72°C for 30s

- 72°C for 3 minutes (Final extension)

- The final libraries can be purified and sequenced on a platform such as Illumina's NovaSeq 6000 [19].

BOLT-seq Workflow: A simplified protocol for cost-effective, high-throughput 3' mRNA-seq.

Computational Protocol: Accurate Deconvolution with ReDeconv

The ReDeconv computational framework is specifically designed to address the pitfalls of transcriptome size variation in deconvolution analysis [14] [15].

1. Principle: ReDeconv introduces a novel normalization method for scRNA-seq reference data that preserves true transcriptome size differences, corrects for gene length effects in bulk data, and incorporates gene expression variance into its model [14].

2. Software and Inputs:

- Tool: ReDeconv (Available at https://redeconv.stjude.org).

- Input 1: Raw count matrix from scRNA-seq data (reference).

- Input 2: Bulk RNA-seq data (mixture).

- Environment: Computational environment with R/Python as required.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: scRNA-seq Reference Normalization. Normalize the raw scRNA-seq count data using the CLTS (Count based on Linearized Transcriptome Size) method instead of CP10K. This step preserves the inherent biological variation in transcriptome size across different cell types in the reference.

- Step 2: Bulk Data Normalization. Apply TPM (Transcripts Per Million) or RPKM/FPKM normalization to the bulk RNA-seq data. This step specifically mitigates the gene length effect that is present in bulk protocols but not in UMI-based scRNA-seq.

- Step 3: Signature Gene Selection. For each cell type in the reference, identify and use a set of signature genes that exhibit stable expression with low variance. This leverages the single-cell resolution of the reference to improve the robustness of the deconvolution model.

- Step 4: Deconvolution Modeling. Execute the ReDeconv algorithm, which integrates the normalized reference and bulk data, along with the variance-stabilized signature genes, to estimate cell type proportions in the bulk sample. The model is designed to be particularly sensitive to rare cell types [14] [15].

ReDeconv Analysis Workflow: A computational pipeline correcting for transcriptome size, gene length, and expression variance.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Transcriptome Size-Aware Analysis

| Item Name | Type | Function/Application | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| BOLT-seq Reagents [19] | Wet-lab Protocol | Cost-effective 3'-end mRNA-seq library prep from cell lysates. | Eliminates RNA purification; single-tube reaction; very low cost per sample. |

| In-house Tn5 Transposase [19] | Laboratory Reagent | Enzyme for tagmentation step in BOLT-seq. | Custom purified, significantly reduces library preparation costs. |

| ReDeconv [14] [15] | Computational Tool/Algorithm | Improved scRNA-seq normalization and bulk RNA-seq deconvolution. | Incorporates transcriptome size, gene length effect, and expression variance. |

| CLTS Normalization [14] | Computational Method | Normalization for scRNA-seq data within ReDeconv. | Preserves biological variation in transcriptome size across cell types. |

| Stranded mRNA Prep Kits (e.g., Illumina) [20] | Commercial Kit | Standard whole-transcriptome or mRNA-seq library preparation. | Determines transcript strand of origin; high sensitivity and dynamic range. |

| Salmon [6] | Computational Tool | Alignment-free quantification of transcript abundance from RNA-seq data. | Handles read assignment uncertainty rapidly; integrates well with workflows like nf-core/rnaseq. |

Transcriptome size variation is a fundamental biological feature with profound implications for the accuracy of bulk RNA-seq analysis. Ignoring this factor, especially in studies of heterogeneous tissues, introduces a systematic bias that compromises the identification of differentially expressed genes and the estimation of cellular abundances. The integration of next-generation experimental protocols like BOLT-seq with sophisticated computational frameworks like ReDeconv, which explicitly models biological parameters such as transcriptome size, represents a critical advancement. By adopting these tools and methodologies, researchers can unlock more precise and biologically meaningful insights from their transcriptomic data, thereby enhancing discoveries in fields ranging from developmental biology to cancer research.

Bulk RNA-seq remains a cornerstone technique for whole transcriptome profiling, providing a population-average view of gene expression. This averaging effect is a fundamental characteristic that presents both a key advantage and a significant inherent limitation. While it offers a robust, cost-efficient overview of the transcriptional state of a tissue or cell population, it simultaneously masks the underlying cellular heterogeneity. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this duality is critical for designing experiments, interpreting data, and selecting the appropriate tool for their biological questions. This application note details the implications of the population averaging effect and provides methodologies to overcome its limitations.

The Principle of Population Averaging

In bulk RNA sequencing, the starting material consists of RNA extracted from a population of thousands to millions of cells. The resulting sequencing library represents a pooled transcriptome, where the expression level for each gene is measured as an average across all cells in the sample [5] [3]. This provides a composite profile, effectively homogenizing the contributions of individual cells.

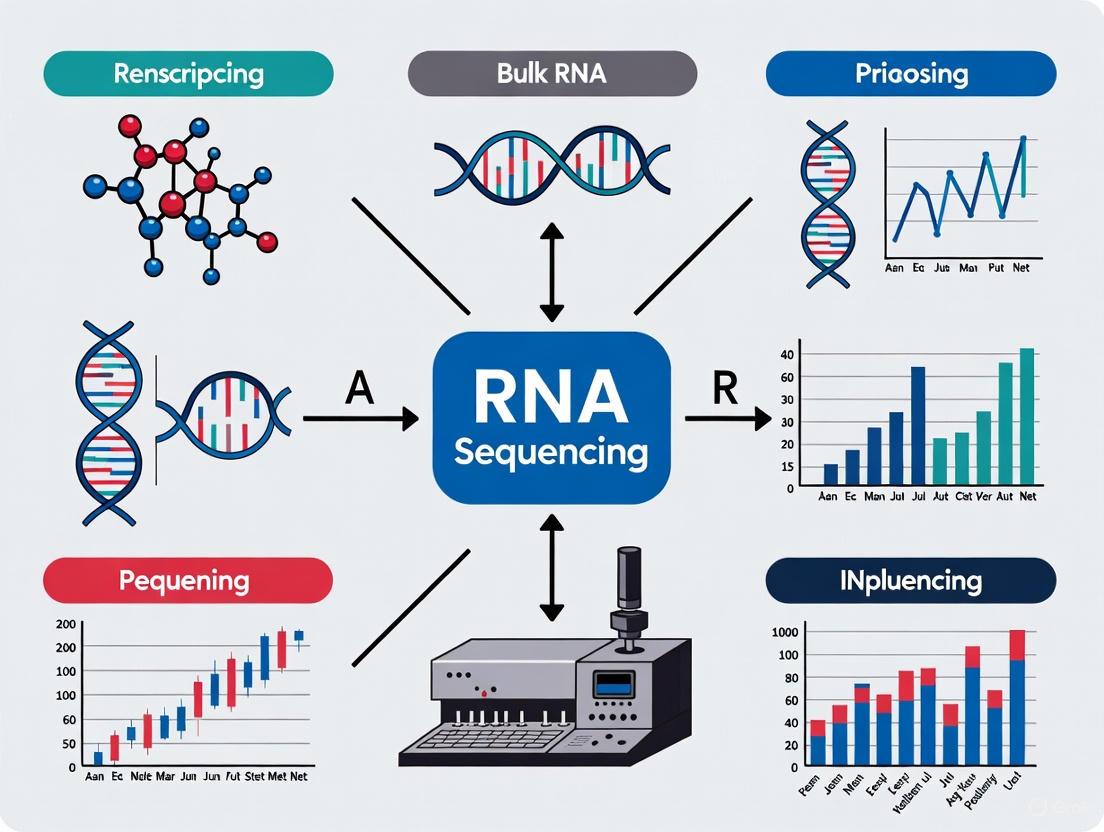

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflow of bulk RNA-seq and where the population averaging occurs.

Advantages: The Power of an Average

The population-level view conferred by bulk RNA-seq offers several distinct advantages for whole transcriptome research, as outlined in the table below.

Table 1: Key Advantages of the Population Averaging Effect in Bulk RNA-seq

| Advantage | Description | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Holistic Profiling | Provides a global, averaged expression profile from whole tissues or organs, representing the collective biological state [3]. | Establishing baseline transcriptomic profiles for tissues; large cohort studies and biobanks [3]. |

| Cost-Efficiency & Simplicity | Lower per-sample cost and simpler sample preparation compared to single-cell methods [3]. | Pilot studies; powering experiments with high numbers of biological replicates. |

| High Sensitivity for Abundant Transcripts | Effective detection and quantification of medium to highly expressed genes due to the large amount of input RNA. | Differential gene expression analysis between conditions (e.g., disease vs. healthy) [3]. |

| Comprehensive Transcriptome Characterization | Can be used to annotate isoforms, non-coding RNAs, alternative splicing events, and gene fusions from a deep sequence of the transcriptome [3] [21]. | Discovery of novel transcripts and biomarker signatures [21]. |

Inherent Limitations: The Consequences of Averaging

The primary limitation of population averaging is its inability to resolve cellular heterogeneity. This can lead to several specific challenges and potential misinterpretations of data.

Table 2: Key Limitations Arising from the Population Averaging Effect

| Limitation | Consequence | Practical Example |

|---|---|---|

| Masking of Cell-Type-Specific Expression | Gene expression changes unique to a rare or minority cell population are diluted and may go undetected [5] [3]. | A transcript upregulated in a rare stem cell population (e.g., <5% of cells) may not appear significant in a bulk profile. |

| Obfuscation of Cellular Heterogeneity | Cannot distinguish between a uniform change in gene expression across all cells versus a dramatic change in a specific subpopulation [21]. | An apparent two-fold increase in a bulk sample could mean a small change in all cells, or a 100-fold change in just 2% of cells. |

| Inability to Identify Novel Cell Types/States | The averaged profile cannot reveal the existence of previously uncharacterized or transient cell states within a sample [3]. | Novel immune cell activation states or rare tumor-initiating cells remain hidden. |

| Confounding by Variable Cell Type Composition | Observed differential expression between samples may be driven by differences in the proportions of constituent cell types rather than true regulatory changes within a specific lineage [22] [23]. | A disease-associated gene signature may simply reflect increased immune cell infiltration rather than altered gene expression in parenchymal cells. |

The following diagram conceptualizes how a bulk RNA-seq experiment interprets a signal from a complex, heterogeneous tissue.

Experimental Protocols to Overcome Limitations

Protocol: Computational Deconvolution of Bulk RNA-seq Data

Computational deconvolution leverages single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) reference datasets to estimate the cellular composition and cell-type-specific gene expression from bulk RNA-seq data [22] [23]. This protocol outlines the key steps.

Key Reagent Solutions for Deconvolution Analysis

Table 3: Essential Tools for Computational Deconvolution

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality scRNA-seq Reference | Provides the cell-type-specific gene expression signatures required for deconvolution. | Public datasets from consortia like the Human Cell Atlas [22]. Must encompass expected cell types in the bulk tissue [23]. |

| Deconvolution Algorithm | A computational method that performs the regression of bulk data onto the reference signature matrix. | Methods include SCDC [22], MuSiC [22], and Bisque [22]. SCDC is unique in its ability to integrate multiple references. |

| Bulk RNA-seq Dataset | The target dataset to be deconvoluted, comprising RNA-seq data from complex tissue samples. | Requires standard bulk RNA-seq processing: quality control, adapter trimming, and gene quantification. |

| Computational Environment | Software and hardware for running analysis, typically using R or Python. | R packages like SCDC [22] or Seurat [23] facilitate the analysis. |

Methodology:

- Acquire and Curate a scRNA-seq Reference Dataset: Obtain a publicly available or in-house scRNA-seq dataset of the same or biologically similar tissue. Critically, this reference must contain all the major cell populations expected to be present in the bulk tissue [23]. Perform standard scRNA-seq quality control and annotation to assign cell type labels to each cluster.

- Construct a Signature Matrix: From the curated scRNA-seq data, generate a cell-type-specific gene expression signature matrix. This matrix contains the average expression levels of a set of informative genes (often marker genes) across each defined cell type [22] [23].

- Apply a Deconvolution Algorithm: Input the bulk RNA-seq data and the signature matrix into a deconvolution tool. For example, the SCDC method uses an ENSEMBLE framework to integrate results from multiple scRNA-seq references, implicitly addressing batch effects and improving accuracy [22].

- Output and Validation: The algorithm outputs the estimated proportion of each cell type in every bulk sample. These results should be validated against known biological expectations or orthogonal methods like flow cytometry, if available [22].

The workflow for this deconvolution approach is detailed below.

Protocol: Interrogating Cell-Type-Specific Gene Signatures

This protocol, adapted from Cid et al., leverages existing scRNA-seq data to deconvolve patterns of cell-type-specific expression from lists of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) obtained from bulk RNA-seq [23].

Methodology:

- Generate Bulk RNA-seq DEG List: Perform a standard differential expression analysis on your bulk RNA-seq data from heterogeneous tissue to identify a list of significant DEGs between conditions.

- Map DEGs to a scRNA-seq Dataset: Extract the expression values for the identified DEGs from a curated scRNA-seq reference dataset.

- Analyze Expression Patterns: Use linear dimensionality reduction (e.g., PCA) and hierarchical clustering on the scRNA-seq data, but subset to only the DEGs from the bulk experiment. This reveals which of the bulk-derived DEGs are co-expressed in specific cell types within the reference data [23].

- Infer Biological Meaning: Identify clusters of genes that are specific to certain cell types. This can reveal whether the bulk differential expression signal is driven by changes in gene regulation within a cell type, changes in cell type abundance, or a combination of both [23].

The population averaging effect of bulk RNA-seq is an intrinsic property that defines its utility. It is a powerful tool for obtaining a quantitative, global overview of gene expression in a tissue, making it ideal for differential expression analysis in well-defined systems and large-scale cohort studies. However, in complex, heterogeneous tissues, this averaging becomes a critical limitation that can obscure biologically significant events occurring in specific cell subpopulations. By understanding these constraints and employing complementary strategies like computational deconvolution and the integration of single-cell reference data, researchers can extract deeper, more accurate insights from their bulk RNA-seq experiments, ultimately advancing discovery in basic research and drug development.

Sequencing Depth and Read Length Requirements for Different Study Goals

In bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq), careful selection of sequencing depth (total number of reads per sample) and read length is fundamental to generating statistically powerful and biologically meaningful data. These parameters are not one-size-fits-all; they are dictated by the specific goals of the study, the organism's transcriptome complexity, and practical considerations of cost and time [24] [25]. Optimal experimental design ensures that the chosen depth and length provide sufficient sensitivity to detect the biological signals of interest without incurring unnecessary expenditure [26] [27]. This guide outlines evidence-based recommendations for these parameters across common research scenarios in whole transcriptome profiling, providing a framework for researchers to design robust and cost-effective RNA-Seq experiments.

Sequencing Depth Recommendations by Study Goal

Sequencing depth directly influences the sensitivity of an RNA-Seq experiment, determining the ability to detect and quantify both highly expressed and low-abundance transcripts [24] [26]. The following table summarizes the recommended sequencing depths for various research aims.

Table 1: Recommended Sequencing Depth for Different Bulk RNA-Seq Goals

| Study Goal | Recommended Sequencing Depth (Million Mapped Reads) | Key Rationale and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Targeted RNA Expression / Focused Gene Panels | 3 - 5 million [24] | Fewer reads are required as the analysis is restricted to a pre-defined set of genes. |

| Differential Gene Expression (DGE) - Snapshot | 5 - 25 million [24] | Sufficient for a reliable snapshot of highly and moderately expressed genes [26]. |

| Standard DGE - Global View | 20 - 60 million [24] [25] | A common range for most studies; provides a more comprehensive view of expression and some capability for alternative splicing analysis [24] [28]. |

| In-depth Transcriptome Analysis | 100 - 200 million [24] | Necessary for detecting lowly expressed genes, novel transcript assembly, and detailed isoform characterization [24]. |

| Diagnostic RNA-Seq (e.g., Mendelian disorders) | 50 - 150 million [29] | Enhances diagnostic yield; deeper sequencing (e.g., >150M) can further improve detection of low-abundance pathogenic transcripts [29]. |

| Small RNA Analysis (e.g., miRNA-Seq) | 1 - 5 million [24] | Due to the small size and limited complexity of the small RNA transcriptome, fewer reads are needed. |

The Critical Role of Biological Replicates

It is crucial to recognize that sequencing depth is not the only determinant of statistical power. For differential expression analysis, the number of biological replicates (independent biological samples per condition) is often more critical than simply sequencing deeper [25] [26]. A well-powered experiment must strike a balance between depth and replication.

- Minimum Replicates: At least 3 biological replicates per condition are considered the minimum standard for statistical rigor, though 4 or more is optimal [25] [28]. Experiments with only 2 replicates have a greatly reduced ability to estimate biological variability and control false discovery rates [25].

- Power vs. Depth: Studies have shown that increasing the number of biological replicates from 2 to 6 provides a greater boost to statistical power and gene detection than increasing sequencing depth from 10 million to 30 million reads per sample [26]. The exact number can vary with the model system—for instance, studies on inbred model organisms may require fewer replicates than those on outbred human populations [28].

Read Length and Sequencing Configuration

The choice of read length and whether to use single-end or paired-end sequencing is primarily driven by the application and the desired information beyond simple gene counting.

Table 2: Recommended Read Length and Configuration by Application

| Application | Recommended Read Length & Configuration | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Profiling / Quantification | 50 - 75 bp, single-end (SE) [24] | Short reads are sufficient for unique mapping and counting transcripts. This is a cost-effective approach for pure quantification. |

| Transcriptome Analysis / Novel Isoform Discovery | 75 - 100 bp, paired-end (PE) [24] | Paired-end reads provide sequences from both ends of a cDNA fragment, offering more complete coverage of transcripts. This greatly improves the accuracy of splice junction detection, isoform discrimination, and novel variant identification [24] [28]. |

| Small RNA Analysis | 50 bp, single-end [24] | A single 50 bp read is typically long enough to cover most small RNAs (e.g., miRNAs) and the adjacent adapter sequence for accurate identification. |

A Protocol for Bulk RNA-Seq Experimental Design and Analysis

This section provides a practical workflow for planning and executing a bulk RNA-Seq study, from initial design to data interpretation.

Experimental Design and Wet Lab Workflow

Diagram 1: A workflow for designing and conducting a bulk RNA-seq experiment.

Step 1: Define Clear Aims Start with a precise hypothesis and objectives. Determine if the primary goal is differential expression, isoform discovery, or novel transcript assembly, as this will directly guide all subsequent choices [27] [28].

Step 2: Establish Biological Replicates and Controls

- Biological Replicates: Plan for a minimum of 3 biological replicates per condition to enable robust statistical inference [25] [28].

- Controls: Include appropriate untreated or mock-treated control groups. Consider using spike-in RNA controls (e.g., ERCC or SIRVs) to monitor technical performance, sensitivity, and quantification accuracy across samples [30] [27].

Step 3: Select Sequencing Strategy Refer to Table 1 and Table 2 to determine the optimal sequencing depth and read length configuration for your specific study goals [24].

Step 4: Library Preparation Convert the extracted RNA into a sequencing-ready library. Key decisions include:

- RNA Selection: Use poly(A) enrichment for capturing coding mRNA (requires high-quality RNA) or ribosomal RNA depletion for including both coding and non-coding RNA (more suitable for degraded samples, like FFPE) [27] [28].

- Library Type: For large-scale studies like drug screens where cost and throughput are critical, 3'-end mRNA-seq methods (e.g., QuantSeq, BOLT-seq) offer a cost-effective alternative to whole transcriptome kits [19] [27]. These methods sequence only the 3' terminus of transcripts, allowing for higher multiplexing.

Step 5: Consider a Pilot Study When working with a new model system or a large, complex experiment, a pilot study with a representative subset of samples is highly recommended to validate the entire workflow—from wet-lab procedures to data analysis—before committing significant resources [27].

Computational Analysis Workflow

The following diagram and protocol describe a standard bioinformatics pipeline for processing bulk RNA-Seq data, starting from raw sequencing files.

Diagram 2: A standard bioinformatics pipeline for bulk RNA-seq data.

Step 1: Quality Control (QC) of Raw Reads

- Tool: FastQC [25] [31].

- Protocol: Assess raw sequencing data in FASTQ format for per-base sequence quality, adapter contamination, unusual GC content, and over-represented sequences. This QC report (e.g., Figure 2B in [25]) identifies potential technical issues before proceeding.

Step 2: Read Trimming and Filtering

- Tool: Trimmomatic or Cutadapt [25] [31].

- Protocol: Remove adapter sequences, leading and trailing low-quality bases (e.g., below quality score 20), and short reads. This cleaning step is crucial for accurate alignment in subsequent steps [25].

Step 3: Alignment to Reference Genome

- Tool: STAR or HISAT2 for splice-aware alignment to a reference genome [25] [31].

- Protocol: Map the cleaned reads to the reference genome/transcriptome of the organism. The output is typically in SAM/BAM format, indicating the genomic location of each read.

Step 4: Post-Alignment QC and Quantification

- Tool: SAMtools for file handling; featureCounts or HTSeq-count for generating count matrices [25] [31].

- Protocol: Perform post-alignment QC with tools like Qualimap to check for correct strandness, mapping rates, and genomic distribution of reads. Then, count the number of reads mapped to each gene to generate a raw count matrix, where the number of reads per gene serves as a proxy for its expression level [25].

Alternative Step 3/4: Pseudoalignment for Quantification

- Tool: Kallisto or Salmon [25].

- Protocol: These tools bypass traditional alignment by rapidly assigning reads to transcripts using a reference transcriptome. They are faster and require less memory, making them well-suited for large datasets. They also incorporate statistical models to improve quantification accuracy [25].

Step 5: Differential Expression and Downstream Analysis

- Tool: DESeq2 or edgeR in R/Bioconductor [25] [31].

- Protocol: Import the count matrix into R. Normalize counts to account for differences in library size and RNA composition. Perform statistical testing to identify genes that are differentially expressed between conditions. Generate visualizations such as volcano plots, MA plots, and heatmaps to interpret the results [25] [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bulk RNA-Seq

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Poly(A) Selection Beads | Enriches for messenger RNA (mRNA) by binding to the poly-A tail, thereby depleting ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and other non-polyadenylated RNAs. Ideal for studying coding transcriptomes from high-quality RNA [28]. |

| Ribosomal Depletion Kits | Probes are used to selectively remove ribosomal RNA (rRNA), preserving both coding and non-coding RNA. Essential for total RNA sequencing or when working with degraded samples (e.g., FFPE) where poly-A tails may be lost [27] [3]. |

| Spike-in RNA Controls (e.g., ERCC, SIRV) | Synthetic RNA molecules added to the sample in known quantities. They serve as an internal standard for assessing technical variability, quantification accuracy, sensitivity, and dynamic range of the assay [30] [27]. |

| Stranded Library Prep Kits | Preserves the strand orientation of the original RNA transcript during cDNA synthesis. This information is critical for accurately determining which DNA strand encoded the transcript, especially important for identifying antisense transcripts and resolving overlapping genes [24] [30]. |

| In-house Purified Tn5 Transposase | An enzyme used in streamlined library prep protocols (e.g., BOLT-seq, BRB-seq) to simultaneously fragment and tag cDNA with sequencing adapters ("tagmentation"). Purifying it in-house can drastically reduce costs for large-scale studies [19]. |

From Sample to Insight: Bulk RNA-Seq Workflows and Clinical Applications

Bulk RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq) remains a cornerstone technique in transcriptomics, enabling the comprehensive analysis of gene expression patterns in pooled cell populations or tissue samples [32]. This methodology provides an averaged snapshot of gene activity across thousands to millions of cells, making it particularly valuable for identifying transcriptional differences between biological conditions, such as healthy versus diseased states or treated versus untreated samples [32]. Within drug development pipelines, bulk RNA-seq facilitates biomarker discovery, mechanism of action studies, and toxicogenomic assessments by providing quantitative data on transcript abundance across the entire genome [33]. The technique's cost-effectiveness and established bioinformatics pipelines make it accessible for large-scale studies where single-cell resolution is unnecessary [32]. This application note details a standardized, end-to-end workflow from RNA extraction through sequencing, providing researchers and drug development professionals with robust protocols optimized for reliable whole transcriptome profiling.

The bulk RNA-seq workflow comprises sequential stages that transform biological samples into interpretable gene expression data. Each stage requires rigorous quality control to ensure data integrity and reproducibility [34]. The process begins with sample collection and RNA extraction, where cellular RNA is isolated while preserving quality and purity [32]. This is followed by RNA quality control to verify RNA integrity and quantify available material [32]. The library preparation stage then converts purified RNA into sequencing-compatible libraries through fragmentation, cDNA synthesis, and adapter ligation [35] [36]. Finally, sequencing generates millions of short reads that represent fragments of the transcriptome [32]. A comprehensive quality control framework spanning preanalytical, analytical, and postanalytical processes is essential for generating reliable data, particularly for clinical applications and biomarker discovery [33]. The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow and its key decision points:

Sample Collection and RNA Extraction

Sample Collection and Lysis

The initial step in bulk RNA sequencing involves collecting biological material and disrupting cellular structures to release RNA. Sample collection must be performed under conditions that preserve RNA integrity, typically through immediate flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen or preservation in specialized RNA stabilization reagents like those in PAXgene Blood RNA tubes for clinical samples [33]. For tissue samples, mechanical homogenization using bead beating or rotor-stator homogenizers is often required. For cell cultures, chemical lysis with detergents may be sufficient. The lysis buffer typically contains chaotropic salts (e.g., guanidinium thiocyanate) and RNase inhibitors to prevent RNA degradation during processing [32]. Singleron's AccuraCode platform offers an alternative approach that uses direct cell barcoding from lysed cells, eliminating the need for traditional RNA extraction and potentially reducing hands-on time [32].

Total RNA Isolation

Following cell lysis, total RNA is isolated using either phenol-chloroform-based separation (e.g., TRIzol reagent) or silica membrane-based purification columns [32]. The phenol-chloroform method separates RNA from DNA and proteins through phase separation, while column-based methods bind RNA to a silica membrane for washing and elution. Column-based methods are generally preferred for their convenience and consistency, especially when processing multiple samples. The objective is to obtain high-quality, intact total RNA encompassing messenger RNA (mRNA), ribosomal RNA (rRNA), transfer RNA (tRNA), and various non-coding RNAs while minimizing contaminants like genomic DNA and proteins that could interfere with downstream reactions [32]. For samples with low cell counts, specialized kits such as the PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit may be necessary to obtain sufficient RNA yield [36].

RNA Quality Control and mRNA Selection

RNA Quality Assessment

Before proceeding to library preparation, rigorous quality assessment of isolated RNA is essential. RNA concentration and purity are typically measured using spectrophotometric methods (NanoDrop) or more accurate fluorometric assays (Qubit) [32]. The A260/A280 ratio should be approximately 2.0 for pure RNA, while significant deviations may indicate contamination. More critically, RNA integrity is evaluated using capillary electrophoresis systems such as the Agilent Bioanalyzer or TapeStation, which provide an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) [32]. A RIN value greater than 7 typically reflects high-quality, intact RNA suitable for high-throughput sequencing [32]. Poor RNA quality can lead to biased or unreliable sequencing results, making this a critical quality control checkpoint. For blood-derived RNA and other challenging sample types, additional steps such as secondary DNase treatment may be necessary to reduce genomic DNA contamination, which significantly lowers intergenic read alignment and improves data quality [33].

mRNA Enrichment Strategies

Once RNA quality is verified, the next critical step involves enriching for transcripts of interest. Two primary strategies are employed, each with distinct advantages for different sample types and research goals:

Poly(A) Selection: This method uses oligo(dT) primers or beads that bind specifically to the polyadenylated tails found at the 3' ends of mature mRNAs [32]. It effectively enriches for protein-coding transcripts while removing most non-coding RNAs, including rRNA and tRNA. Poly(A) selection is best suited for high-quality RNA samples with intact poly(A) tails and is commonly used when the primary interest is gene expression profiling of coding transcripts [32].

rRNA Depletion: This approach removes abundant ribosomal RNA species (typically comprising 80-98% of total RNA) through hybridization-based capture or enzymatic digestion [37] [32]. Ribodepletion is advantageous for analyzing degraded RNA samples (e.g., from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues), as well as for detecting non-polyadenylated transcripts such as certain long non-coding RNAs, histone mRNAs, and circular RNAs [32].

The choice between these methods depends on RNA quality, sample type, and research objectives. For standard gene expression profiling of high-quality samples, poly(A) selection is typically preferred, while ribodepletion offers broader transcriptome coverage for diverse RNA species.

Library Construction

RNA Fragmentation and cDNA Synthesis

Library construction begins with RNA fragmentation, which breaks the RNA into smaller, manageable fragments typically around 200 base pairs in length [32]. This step facilitates efficient cDNA synthesis and ensures even coverage across transcripts during sequencing. Fragmentation can be achieved through enzymatic digestion using RNases or chemical methods employing divalent cations at elevated temperatures [32]. The method and extent of fragmentation must be carefully controlled, as over-fragmentation can result in loss of information, while under-fragmentation may hinder library construction. Following fragmentation, RNA fragments are reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using reverse transcriptase with random hexamer primers or oligo(dT) primers, depending on the RNA selection strategy [32]. Random primers are commonly used to ensure that the entire length of RNA fragments is captured, regardless of their polyadenylation status. High-fidelity reverse transcription is essential for preserving transcript diversity and preventing bias in downstream quantification.

Library Preparation and QC

Once cDNA is synthesized, sequencing libraries are prepared through several standardized steps. The process typically includes:

- End repair and A-tailing: The ends of cDNA fragments are blunted and adenylated to allow efficient adapter ligation [32].

- Adapter ligation: Short, double-stranded DNA adapters containing sequencing platform-specific sequences and sample-specific barcodes (indexes) are ligated to both ends of each cDNA fragment [32]. These adapters enable binding to the sequencing flow cell and facilitate sample multiplexing.

- PCR amplification: The adapter-ligated cDNA is amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to increase the amount of material available for sequencing [32].

Specific protocols, such as those using the KAPA RNA HyperPrep Kit with RiboErase, are widely used for library construction [36]. This particular workflow processes samples with an input of 300ng RNA and utilizes specific indexes (e.g., IDT for Illumina - TruSeq DNA UD Indexes) for sample multiplexing [36]. The final cDNA libraries undergo quality checking and quantification before sequencing, typically using methods such as qPCR, fluorometry, or capillary electrophoresis to ensure appropriate concentration and size distribution.

Sequencing and Data Analysis

Sequencing Platforms and Parameters

The prepared libraries are sequenced using high-throughput platforms such as Illumina's NovaSeq, NextSeq, or NovaSeq X Plus systems [36] [32]. These platforms generate millions to billions of short reads (typically 50-300 base pairs in length) that represent fragments of the transcriptome. For the NovaSeq X Plus with a 10B flow cell, sequencing can be performed in 100, 200, or 300 cycle configurations, with each cycle kit including additional cycles for index reads [36]. Each lane of a 10B flow cell yields approximately 1250 million reads, enabling extensive multiplexing of samples [36]. The selection of read length and sequencing depth depends on the experimental goals, with longer reads and greater depth required for applications like isoform discovery and detection of low-abundance transcripts. For standard differential expression analysis, 20-30 million reads per sample is often sufficient, while more complex applications may require 50-100 million reads per sample.

Bioinformatics Analysis Workflow

Following sequencing, the resulting data undergoes a comprehensive bioinformatics processing pipeline. While specific tools and parameters may vary, a standard bulk RNA-seq analysis workflow includes:

- Quality Control and Trimming: Raw sequencing data (FASTQ files) are evaluated using tools like FastQC to assess base quality, adapter contamination, GC content, and other quality metrics [38] [34]. Trimming tools such as fastp or Trim_Galore are then used to remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases [38].

- Read Alignment: Processed reads are aligned to a reference genome or transcriptome using splice-aware aligners such as STAR [6] [39]. The alignment process must account for intron-spanning reads, with typical mapping rates above 70% indicating good quality data [34].

- Quantification: The number of reads mapped to each gene is counted using tools like featureCounts [39]. For the nf-core RNA-seq workflow, alignment with STAR followed by Salmon quantification is recommended to handle uncertainty in read assignment while generating gene-level counts [6].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Statistical methods implemented in tools such as DESeq2 or limma are used to identify genes that show significant expression differences between experimental conditions [6] [39]. These tools model count data using appropriate statistical distributions and account for biological variability.

The nf-core RNA-seq workflow provides a standardized, reproducible pipeline that incorporates many of these steps, offering an integrated solution for end-to-end analysis [6].

Quality Control Metrics and Troubleshooting

Essential QC Metrics

Comprehensive quality control is critical throughout the RNA-seq workflow to ensure data reliability. Key metrics should be monitored at each stage, with established thresholds for acceptability:

Table 1: Essential RNA-Seq Quality Control Metrics and Target Values

| QC Metric | Target Value | Importance |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Integrity Number (RIN) | >7 [32] | Indicates intact, high-quality RNA input |

| Residual rRNA Reads | 4-10% [37] | Measures efficiency of rRNA removal |

| Mapping Rate | >70% [34] | Percentage of reads successfully aligned to reference |

| Duplicate Reads | Variable by expression level [37] | Differentiate PCR duplicates from highly expressed genes |

| Exon Mapping Rate | Higher for polyA-selected libraries [37] | Indicates library preparation efficiency |

| Genes Detected | Sample-dependent [37] | Measures library complexity and sequencing depth |

Systematic quality control frameworks implemented across preanalytical, analytical, and postanalytical processes have been shown to significantly enhance the confidence and reliability of RNA-seq results, particularly for clinical applications and biomarker discovery [33]. Tools such as FastQC, MultiQC, RSeQC, and Picard provide comprehensive quality assessment across multiple samples and sequencing runs [34].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Several common issues may arise during bulk RNA-seq experiments, each with specific diagnostic indicators and remedial approaches:

- Low Mapping Rates (<70%): This may result from incorrect reference genome selection, sample contamination, or poor sequence quality. Verification of the reference genome compatibility with the sample species and re-assessment of raw data quality are recommended first steps [34].

- High rRNA Content (>10%): Indicates inadequate rRNA depletion during library preparation. For future preparations, ensure proper optimization of ribodepletion protocols or consider implementing an additional DNase treatment step to reduce genomic DNA contamination that can contribute to intergenic reads [33].

- High Duplication Rates: Often associated with low input material or excessive PCR amplification during library preparation. If possible, increase RNA input amounts and optimize PCR cycle numbers to maintain library complexity [37] [34].

- 3' or 5' Bias: Uneven coverage across transcripts may indicate RNA degradation or bias introduced during library preparation. Check RNA integrity prior to library prep and consider using library preparation kits with built-in bias correction methods [34].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of bulk RNA-seq workflows relies on specific reagents and kits optimized for each step of the process. The following table details essential materials and their functions:

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Kits for Bulk RNA-Seq Workflows

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TRIzol Reagent [32] | Total RNA isolation through phase separation | Effective for diverse sample types; compatible with many downstream applications |

| KAPA RNA HyperPrep Kit with RiboErase [36] | Library construction with rRNA depletion | Processes 300ng input RNA; compatible with Illumina platforms |

| RNase-Free DNase Set [36] | Genomic DNA removal | Critical for reducing genomic DNA contamination; especially important for blood-derived RNA |

| IDT for Illumina TruSeq DNA UD Indexes [36] | Sample multiplexing with unique barcodes | Enables pooling of up to 96 samples; essential for cost-effective sequencing |

| Agilent Bioanalyzer RNA Kits [32] | RNA integrity assessment | Provides RIN values for objective RNA quality assessment |

| PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit [36] | RNA extraction from low-cell-count samples | Specialized protocol for limited input material |

Workflow Integration and Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated bioinformatics workflow for processing bulk RNA-seq data after sequencing, highlighting the key steps and alternative approaches:

This application note provides a comprehensive framework for implementing bulk RNA-seq workflows from RNA extraction through sequencing and data analysis. The standardized protocols and quality control metrics detailed here provide researchers and drug development professionals with a robust foundation for generating reliable, reproducible transcriptomic data. By adhering to these best practices—including rigorous RNA quality assessment, appropriate mRNA selection strategies, optimized library construction, and comprehensive bioinformatics analysis—researchers can maximize the value of their bulk RNA-seq experiments. The implementation of end-to-end quality control frameworks, as demonstrated in recent studies [33], further enhances the reliability of results and facilitates the translation of transcriptomic findings into clinically actionable insights. As bulk RNA-seq continues to evolve as a cornerstone technology in transcriptomics and drug development, these standardized workflows and quality assurance practices will remain essential for generating biologically meaningful data that advances our understanding of gene expression in health and disease.

Differential Gene Expression Analysis with DESeq2 and Alternative Tools

Differential Gene Expression (DGE) analysis is a foundational technique in modern transcriptomics that enables researchers to identify genes whose expression levels change significantly between different biological conditions, such as disease versus healthy states, treated versus control samples, or different developmental stages. In the context of bulk RNA-seq for whole transcriptome profiling, this approach provides a population-level perspective on gene expression changes, capturing averaged expression profiles across all cells in a sample. Bulk RNA-seq remains a powerful and cost-effective method for identifying overall expression trends, discovering biomarkers, and understanding pathway-level changes in response to experimental conditions [3] [40].