Bulk RNA-seq vs Single-Cell RNA-seq: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Applications, and Strategic Choice

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the choice between bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing.

Bulk RNA-seq vs Single-Cell RNA-seq: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Applications, and Strategic Choice

Abstract

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the choice between bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing. It covers the foundational principles of each method, detailing their respective workflows from sample preparation to data output. The content explores specific applications across biomedical research, from differential expression analysis to characterizing tumor heterogeneity and discovering novel cell types. It addresses key practical considerations, including cost, experimental complexity, and data analysis challenges, while also highlighting how these technologies are synergistically combined and validated. The goal is to empower scientists with the knowledge to select the optimal transcriptomic approach for their specific research questions and to understand the future trajectory of the field.

Core Concepts: Understanding the Fundamental Principles of Transcriptomics

What is Bulk RNA-seq? Defining the Population-Averaged Transcriptome

Bulk RNA sequencing (Bulk RNA-seq) is a foundational molecular biology technique designed to profile the average gene expression levels in a sample consisting of a pooled population of cells, entire tissue sections, or biopsies [1] [2]. This method provides a global overview of the transcriptome—the complete set of RNA transcripts in a biological sample—by measuring the collective expression of thousands of genes simultaneously [3]. The "bulk" designation distinguishes it from more recent technologies like single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), as it analyzes the RNA from thousands to millions of cells all at once, resulting in a population-averaged gene expression profile [4]. This approach has been a cornerstone in transcriptomic studies for nearly two decades, enabling researchers to conduct comparative analyses between different sample conditions, such as healthy versus diseased tissues, or treated versus untreated groups [2] [4]. By capturing the overall transcriptional output of a cell population, bulk RNA-seq serves as a powerful tool for identifying broad gene expression differences, discovering biomarkers, and understanding global regulatory mechanisms [3] [4].

Core Principles and Technical Workflow

The fundamental principle of bulk RNA-seq is the conversion of RNA molecules into complementary DNA (cDNA) libraries that are suitable for high-throughput sequencing on next-generation platforms [3]. A standard bulk RNA-seq workflow involves multiple critical steps, from sample preparation to computational analysis, each contributing to the quality and reliability of the final data.

Sample Preparation and Library Construction

The process begins with RNA extraction from the bulk sample, which could be a cell pellet, a piece of tissue, or a tissue biopsy [1] [5]. Given that ribosomal RNA (rRNA) constitutes over 80% of total RNA but is often not the focus of studies, it is typically removed to enrich for the RNA species of interest [3]. This is achieved through either ribo-depletion (removal of rRNA) or poly(A) selection (enrichment for messenger RNA by capturing its poly-A tail) [3] [5]. The choice between these methods depends on the research goals; poly(A) selection is suitable for studying mature mRNA, while rRNA depletion allows for the analysis of other RNA species, including non-coding RNAs and pre-mRNA [5].

The purified RNA is then converted into a sequenceable library. This involves fragmenting the RNA, reverse transcribing it into double-stranded cDNA, and ligating platform-specific adapters [4] [5]. A critical step in multiplexed studies is the addition of unique molecular barcodes (or indices) to each sample during library preparation. This allows multiple samples to be pooled and sequenced together while maintaining the ability to computationally distinguish them after sequencing [1]. The quality and concentration of the resulting cDNA library are assessed using systems like the Agilent TapeStation before sequencing [1].

Sequencing and Data Analysis

The pooled libraries are sequenced using high-throughput platforms, most commonly from Illumina, generating millions of short reads [4]. The data analysis workflow can be broadly divided into upstream and downstream processes:

Upstream Analysis: This involves quality control of the raw sequencing reads (e.g., using FastP), alignment to a reference genome or transcriptome using splice-aware aligners like STAR, and quantification of gene expression levels [6] [7]. Tools such as Salmon or kallisto use pseudo-alignment to quickly estimate transcript abundances, while others like RSEM employ expectation-maximization algorithms to quantify gene and isoform levels from aligned reads [6] [8]. The final output is a count matrix, where rows represent genes and columns represent samples, containing expression values such as Counts, TPM (Transcripts Per Million), or FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of Transcript per Million) [6] [8].

Downstream Analysis: Once the expression matrix is obtained, researchers can perform various data mining operations. These include differential expression analysis to identify genes with significant expression changes between conditions (using tools like DESeq2, EdgeR, or limma) [6] [7], clustering and visualization (e.g., PCA, heatmaps) to explore sample relationships, and enrichment analysis (e.g., GSEA, ORA) to uncover biological pathways or functions associated with the differentially expressed genes [4] [7].

Table 1: Key Steps in a Standard Bulk RNA-seq Workflow

| Stage | Key Steps | Common Tools/Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Prep | RNA Extraction, rRNA depletion/polyA selection, cDNA synthesis, Adapter Ligation | Oligo(dT) beads, Ribosomal depletion kits |

| Sequencing | High-throughput sequencing on a platform | Illumina, Paired-end/Single-end sequencing |

| Upstream Analysis | Quality Control, Read Alignment, Quantification | FastQC, STAR, Salmon, RSEM |

| Downstream Analysis | Differential Expression, Pathway Analysis, Visualization | DESeq2, limma, GSEA, ggplot2 |

The following diagram illustrates the core steps of a standard bulk RNA-seq workflow, from sample to data, including the optional multiplexing step:

Key Applications in Research

Bulk RNA-seq has broad and well-established utilities across biological research and clinical applications. Its ability to provide a quantitative, genome-wide snapshot of gene expression makes it indispensable for:

Differential Gene Expression Studies: This is the most common application, where bulk RNA-seq is used to compare gene expression profiles between different conditions, such as diseased versus healthy tissues, treated versus untreated samples, or different time points in a developmental process [6] [9]. This helps pinpoint genes with significant expression changes that may be drivers of a biological process or disease state [4].

Biomarker Discovery: By analyzing gene expression patterns across large cohorts of samples, researchers can identify specific genes or gene signatures (biomarkers) that are associated with a particular disease, prognosis, or response to treatment [2] [3]. For example, numerous RNA-seq-based signatures have been developed and validated across major tumor types for cancer classification and prognosis prediction [2].

Detection of Gene Fusions and Alternative Splicing: Beyond gene expression levels, bulk RNA-seq can detect various forms of genomic alterations, including gene fusions—which are well-documented as major cancer drivers—as well as alternative splicing events and novel transcripts [2] [4]. Targeted RNA-seq panels, such as FoundationOne Heme, are used in clinical oncology for therapy selection by detecting these alterations [2].

Pathway and Network Analysis: The global expression data from bulk RNA-seq allows for gene set enrichment analysis and the construction of gene regulatory or co-expression networks (e.g., using WGCNA). This helps in understanding the biological pathways and processes that are perturbed in a given condition [4] [7].

Bulk RNA-seq vs. Single-Cell RNA-seq: A Detailed Comparison

The emergence of single-cell RNA sequencing has revolutionized transcriptomics, but bulk RNA-seq remains a widely used and vital technology. The choice between them depends heavily on the research question, as they offer complementary strengths and limitations.

Table 2: Comparing Bulk RNA-seq and Single-Cell RNA-seq

| Aspect | Bulk RNA Sequencing | Single-Cell RNA Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population-averaged gene expression [2] [4] | Individual cell resolution [2] [9] |

| Primary Goal | Compare average expression between sample groups [4] | Investigate cellular heterogeneity and identify cell types/states [4] [9] |

| Cost | Relatively low (~1/10th of scRNA-seq) [9] | Higher [9] |

| Data Complexity | Lower, simpler to analyze [9] | High, requires specialized computational methods [9] |

| Cell Heterogeneity | Masks heterogeneity; cannot detect rare cell types [2] [4] | Excellent for uncovering heterogeneity and rare cell populations [2] [9] |

| Gene Detection Sensitivity | Higher per sample, detects more genes [9] | Lower per cell, sparsity due to technical dropout [9] |

| Ideal For | Homogeneous samples, large-scale studies, biomarker discovery, differential expression [4] [9] | Complex tissues, tumor heterogeneity, immune profiling, developmental biology [2] [9] |

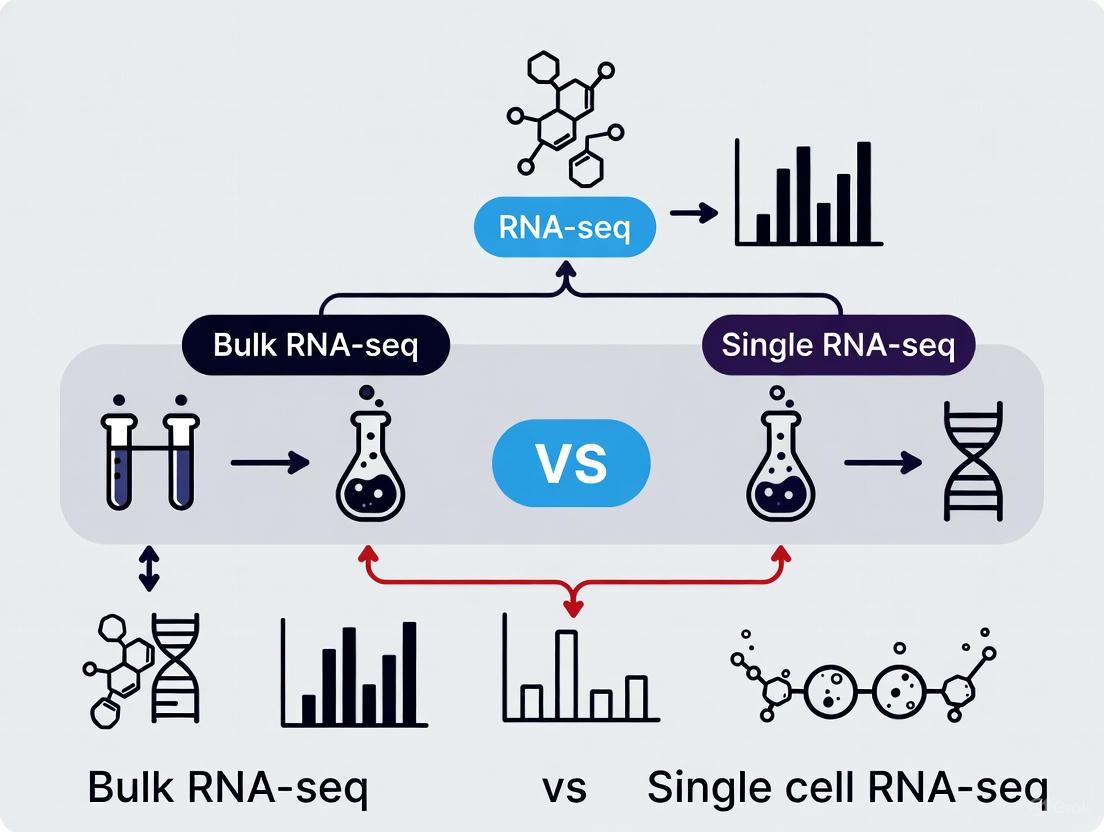

The core difference is visualized in the following diagram, which contrasts the averaging nature of bulk RNA-seq with the high-resolution view of scRNA-seq:

Standards, Protocols, and the Scientist's Toolkit

Robust and reproducible bulk RNA-seq experiments rely on adherence to established standards and the use of high-quality reagents.

Experimental and Data Standards

Consortiums like ENCODE have developed rigorous standards for bulk RNA-seq experiments to ensure data quality and reproducibility [8]. Key guidelines include:

- Replication: Experiments should have two or more biological replicates. Replicate concordance is typically measured by Spearman correlation of gene-level quantifications, which should be >0.9 between isogenic replicates [8].

- Sequencing Depth: A common standard is 20-30 million aligned reads per replicate for mRNA-seq libraries, although this can vary based on the experiment's goals [8].

- RNA Quality: RNA Integrity Number (RIN) is a critical metric. A RIN value over 6 is generally considered sufficient for sequencing, though higher is preferable [5].

- Spike-in Controls: Exogenous RNA spike-in controls (e.g., ERCC Spike-ins) are often added to samples during library preparation to provide a standard baseline for quantitative normalization and quality assessment [8].

Successful execution of a bulk RNA-seq project requires a suite of trusted reagents, tools, and software.

Table 3: Essential Toolkit for Bulk RNA-seq Experiments

| Category | Item | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | rRNA Depletion Kits / poly-dT Oligos | Enriches for RNA species of interest by removing rRNA or selecting for mRNA [3] [5] |

| Unique Barcoded Adapters | Allows sample multiplexing in a single sequencing run [1] | |

| ERCC Spike-in Controls | Exogenous RNA controls for normalization and QC [8] | |

| Software & Pipelines | STAR | Spliced aligner for mapping reads to a reference genome [6] [8] |

| Salmon / kallisto | Tools for fast, accurate transcript quantification [6] | |

| DESeq2 / limma / EdgeR | Statistical packages for differential expression analysis [6] [7] | |

| Searchlight / nf-core RNA-seq | Automated pipelines for downstream visualization and analysis [7] |

Bulk RNA-seq remains a powerful and indispensable workhorse in the genomic toolbox. Its strength lies in providing a cost-effective, robust, and comprehensive overview of the average transcriptional state of a cell population, making it ideal for differential expression studies, biomarker discovery, and large-scale cohort analyses. While it cannot resolve the cellular heterogeneity captured by single-cell technologies, its well-established protocols, lower cost, and simpler data analysis ensure its continued relevance. The future of transcriptomics lies in integrated approaches, where the broad, quantitative profiling of bulk RNA-seq is combined with the high-resolution insights from scRNA-seq and spatial transcriptomics to build a more complete and multi-scale understanding of complex biological systems [4].

What is Single-Cell RNA-seq? Unveiling Cellular Heterogeneity

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) represents a transformative technological advancement in genomics that enables researchers to examine the gene expression profile of individual cells. Unlike traditional bulk RNA sequencing, which measures the average gene expression across thousands to millions of cells in a sample, scRNA-seq reveals the cellular heterogeneity and unique transcriptional states of each cell within a complex biological system [9] [10]. Since its conceptual breakthrough in 2009, scRNA-seq has evolved from a specialized technique to an accessible tool that fuels discovery across biomedical research and clinical applications [11] [10]. By uncovering the full diversity of cell types, states, and functions within tissues and organs, scRNA-seq provides an unprecedented window into the fundamental units of biology, revolutionizing our understanding of development, disease, and treatment responses [11] [12].

The Fundamental Difference: Bulk RNA-seq vs. Single-Cell RNA-seq

The core distinction between bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing lies in resolution and the resulting biological insights each method can provide.

Bulk RNA-seq processes RNA from a population of cells together, generating a composite gene expression profile that represents the average across all cells in the sample [9] [13]. This approach effectively masks differences between individual cells and obscures rare cell populations.

Single-cell RNA-seq isolates individual cells before RNA capture and sequencing, allowing each cell's transcriptome to be profiled independently [9]. This reveals the cellular composition of tissues, identifies novel cell types, and uncovers continuous transitional states that are invisible in bulk measurements [13] [10].

The following diagram illustrates this fundamental difference in resolution and the type of biological information each method reveals:

The following table provides a detailed quantitative comparison of these two approaches:

Table 1: Key Technical and Practical Differences Between Bulk and Single-Cell RNA-seq

| Feature | Bulk RNA Sequencing | Single-Cell RNA Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population average [9] | Individual cell level [9] |

| Cost per Sample | Lower (~$300/sample) [9] | Higher ($500-$2000/sample) [9] |

| Data Complexity | Lower, simpler analysis [9] [14] | Higher, requires specialized computational methods [9] [14] |

| Cell Heterogeneity Detection | Limited, masks diversity [9] [13] | High, reveals cellular diversity [9] [13] |

| Rare Cell Type Detection | Limited or impossible [9] | Possible, can identify rare populations [9] |

| Gene Detection Sensitivity | Higher per sample [9] | Lower per cell, but captures more cell-specific genes [9] |

| Sample Input Requirement | Higher amount of starting material [9] | Lower, can work with minimal cells [9] |

| Ideal Application | Homogeneous samples, differential expression [9] [14] | Complex tissues, rare cell identification, heterogeneity studies [9] [14] |

Technical Framework: How Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Works

The scRNA-seq workflow involves several critical steps to transition from tissue to sequencing data, each with specific technical considerations for preserving cell integrity and transcriptome fidelity.

Single-Cell Isolation and Capture

The initial phase involves creating a viable single-cell suspension from tissue through enzymatic or mechanical dissociation [13]. This step is particularly challenging as the dissociation process can induce artificial transcriptional stress responses, potentially altering the native gene expression profile [11]. Techniques to minimize this include performing dissociations at lower temperatures (4°C) or utilizing single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) as an alternative, especially for tissues difficult to dissociate, such as brain tissue [11]. Common isolation methods include:

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): Allows selection of specific cell types based on surface markers [11] [10]

- Microfluidic Systems: Enable high-throughput cell capture with minimal hands-on time [11] [15]

- Droplet-Based Partitioning: Currently the most widely used approach, encapsulating individual cells in nanoliter-scale reaction vessels [15] [13]

Library Preparation and Barcoding

After isolation, individual cells are processed to capture and barcode their RNA content. In droplet-based systems like 10x Genomics' platform, single cells are combined with barcoded gel beads and partitioning oil to form GEMs (Gel Beads-in-emulsion) [15] [13]. Within each GEM:

- Cells are lysed to release RNA

- Polyadenylated mRNA molecules hybridize to the poly(T) primers on the gel beads

- Each primer contains a cell barcode (unique to each cell), a unique molecular identifier (UMI), and sequencing adapters [15] [10]

The use of UMIs is critical for accurate transcript quantification as they label individual mRNA molecules, enabling correction for amplification biases during computational analysis [11].

Reverse Transcription, Amplification, and Sequencing

After barcoding, reverse transcription occurs within the partitions to create cDNA libraries where all transcripts from a single cell share the same barcode [15]. The barcoded cDNA is then:

- Amplified via PCR to create sufficient material for sequencing

- Pooled for traditional bulk next-generation sequencing (NGS) [13]

Despite the initial single-cell partitioning, the actual sequencing step is performed as a pooled library, with the cellular origin of each transcript later decoded based on its barcode [15] [10].

The following diagram illustrates this complex workflow from sample preparation to sequencing:

Essential Research Tools: The Single-Cell RNA-seq Toolkit

Successful scRNA-seq experiments require specialized reagents and platforms designed to handle the unique challenges of working with minute quantities of starting material while maintaining cell integrity and transcriptome representation.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Cell RNA-seq

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Barcoding Beads | Gel beads containing barcoded oligonucleotides for labeling cellular origin [15] | Critical for sample multiplexing and cell identity preservation |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Random nucleotide sequences that uniquely tag individual mRNA molecules [11] | Enables accurate transcript quantification by correcting PCR amplification bias |

| Reverse Transcription Mix | Converts mRNA to cDNA with template-switching capability [11] [10] | SMARTer chemistry improves full-length transcript capture |

| Partitioning Oil & Microfluidics | Creates stable water-in-oil emulsions for single-cell isolation [15] [13] | GEM-X technology increases throughput while reducing multiplet rates |

| Library Preparation Kits | Prepares barcoded cDNA for next-generation sequencing [15] [10] | Compatibility with various sequencing platforms (Illumina, PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) |

| Cell Viability Stains | Assesses cell integrity and membrane integrity before processing [13] | Critical for ensuring high-quality input material and reducing ambient RNA |

| Enzymatic Dissociation Kits | Tissue-specific protocols for generating single-cell suspensions [13] | Must balance yield with preservation of native transcriptional states |

Commercial scRNA-seq platforms such as 10x Genomics' Chromium system, Parse Biosciences' Evercode combinatorial barcoding, and Fluidigm's C1 platform provide integrated solutions that combine many of these reagent systems into standardized workflows [15] [16]. The choice between platforms depends on specific research needs, including cell throughput, sequencing depth, cost constraints, and sample type (fresh, frozen, or fixed) [15] [13].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

The pharmaceutical industry has embraced scRNA-seq as a powerful tool to address key challenges in drug discovery and development, particularly in understanding disease mechanisms, identifying therapeutic targets, and predicting clinical responses.

Target Identification and Validation

scRNA-seq enables cell-type-specific target discovery by identifying genes expressed specifically in disease-relevant cell populations [12] [16]. For example, in a comprehensive analysis across 30 diseases and 13 tissues, researchers found that drug targets with cell-type-specific expression in disease-relevant tissues were more likely to progress successfully from Phase I to Phase II clinical trials [16]. This predictive power helps prioritize targets with higher potential for success early in the development process.

When combined with CRISPR-based functional genomics, scRNA-seq can simultaneously measure the transcriptomic effects of thousands of genetic perturbations in individual cells [12] [16]. This approach maps regulatory networks and pathway dependencies, providing mechanistic insights into how potential targets contribute to disease pathology [16].

Biomarker Discovery and Patient Stratification

The technology has proven particularly valuable in oncology, where it reveals intratumoral heterogeneity and identifies resistance mechanisms to therapy [9] [12]. For instance, scRNA-seq studies of melanoma patients receiving checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy identified distinct T cell states associated with treatment response or resistance [12]. These findings enable development of predictive biomarkers for patient selection and treatment monitoring.

Similar approaches have identified rare cell populations driving disease progression in multiple myeloma and non-small cell lung cancer, revealing potential biomarkers for disease monitoring and novel therapeutic targets [9] [12].

Toxicity Assessment and Mechanism of Action Studies

By profiling drug responses across diverse cell types within complex tissues, scRNA-seq provides comprehensive safety assessments early in drug development [17] [16]. This approach can identify cell-type-specific toxicities that might be missed in traditional bulk analyses, potentially reducing late-stage attrition due to safety concerns [16].

Furthermore, scRNA-seq elucidates drug mechanisms of action by capturing how different cell populations within a tissue respond to treatment, informing both efficacy and safety profiles [12]. This detailed understanding supports more rational drug design and optimization.

Single-cell RNA sequencing has fundamentally transformed our ability to study biology and disease at its most basic resolution—the individual cell. By revealing the cellular heterogeneity that underlies tissue function, developmental processes, and disease mechanisms, scRNA-seq provides insights that were previously inaccessible with bulk sequencing approaches. As technologies continue to evolve with decreasing costs, increased throughput, and enhanced multimodal capabilities (combining transcriptomics with epigenomics, proteomics, and spatial information), scRNA-seq is poised to become an increasingly central tool in both basic research and translational applications [9] [11] [12]. For drug discovery professionals and researchers, mastering this technology and its applications offers the potential to accelerate the development of more targeted, effective, and personalized therapeutic interventions.

In the study of gene expression, two powerful technologies offer fundamentally different vantage points. Bulk RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq) provides a population-level overview, akin to observing a forest from a distance, while single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) reveals the individual trees, capturing the unique characteristics of each cell [13]. This distinction is critical for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals navigating the complexities of biological systems and disease mechanisms. The choice between these methods—or the decision to integrate them—carries significant implications for experimental design, cost, analytical capabilities, and ultimately, the biological insights that can be gained [13] [18]. This technical guide explores the core differences, applications, and methodologies of these two approaches, providing a structured framework for their application in modern research.

Core Concepts and Definitions

Bulk RNA Sequencing: The Population Perspective

Bulk RNA-seq is a next-generation sequencing (NGS)-based method designed to measure the whole transcriptome across a population of thousands to millions of cells [13]. It operates as a whole population approach, processing a biological sample where many different cells are pooled together. The resulting data represents an average readout of gene expression levels for individual genes across all cells within the sample [13]. The foundational workflow involves digesting the biological sample to extract RNA, which is then converted into cDNA before library preparation and sequencing [13]. Its key strength lies in providing a holistic, cost-effective view of the average gene expression profile of an entire tissue sample or cell population [19].

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing: The Cellular Perspective

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) represents a paradigm shift, enabling the measurement of whole transcriptome gene expression profiles for each individual cell within a sample [13]. This cellular-resolution approach fundamentally changes how scientists observe biological systems, transforming a homogenous average into a detailed landscape of cellular heterogeneity. The scRNA-seq workflow necessitates several specialized steps, beginning with the generation of viable single cell suspensions from whole samples through enzymatic or mechanical dissociation [13] [20]. A critical differentiator from bulk methods is the instrument-enabled cell partitioning, where single cells are isolated into individual micro-reaction vessels—such as the Gel Beads-in-emulsion (GEMs) used in 10x Genomics' Chromium system—ensuring that analytes from each cell can be traced back to their origin through cell-specific barcodes [13] [20].

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Bulk RNA-seq and Single-Cell RNA-seq

| Feature | Bulk RNA-seq | Single-Cell RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population-level average [13] | Individual cell level [13] |

| Primary Output | Averaged gene expression across all cells [13] | Cell-to-cell variation and heterogeneity [13] |

| Key Advantage | Cost-effective for large studies; established analysis pipelines [19] | Reveals rare cell types, novel cell states, and cellular dynamics [13] |

| Sample Input | Pooled cells from tissue or population [13] | Viable single-cell suspension [13] |

| Typical Cost | Lower cost per sample [13] [19] | Higher cost per sample, but decreasing [13] |

| Data Complexity | Lower; more straightforward analysis [13] | High-dimensional; requires specialized bioinformatics [13] [21] |

| Ideal Use Case | Differential expression between conditions; biomarker discovery [13] | Characterizing heterogeneous populations; developmental trajectories [13] |

Technical and Experimental Comparisons

Divergent Experimental Workflows

The experimental protocols for bulk and single-cell RNA-seq diverge significantly from the initial sample preparation stage, each presenting unique technical considerations and challenges.

Bulk RNA-seq Protocol follows a relatively straightforward path [13]:

- Sample Digestion: Biological sample is digested to extract total RNA or enriched mRNA.

- cDNA Conversion: RNA is converted into cDNA.

- Library Preparation: Processing steps prepare a sequencing-ready gene expression library.

- Sequencing & Analysis: Sequencing is performed followed by data analysis to review gene expression levels across the tissue sample.

Single-Cell RNA-seq Protocol requires more specialized steps to preserve single-cell resolution [13] [20]:

- Sample Dissociation: Generation of viable single-cell suspensions via enzymatic or mechanical dissociation.

- Quality Control: Cell counting and viability assessment to ensure sample quality.

- Cell Partitioning: Single cells are isolated into individual micro-reaction vessels using microfluidic systems.

- Cell Lysis & Barcoding: Cells are lysed within partitions, and RNA is captured and barcoded with cell-specific barcodes.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Barcoded products are used to create sequencing libraries for whole transcriptome measurement.

Analytical Approaches and Computational Considerations

The data analysis pipelines for bulk and single-cell RNA-seq differ substantially in complexity and methodology, reflecting their fundamentally different data structures and research questions.

Bulk RNA-seq Analysis typically involves established, relatively straightforward pipelines [19]:

- Differential gene expression analysis using tools like DESeq2 or edgeR

- Pathway and enrichment analysis (GO, KEGG)

- Biomarker identification and validation

Single-Cell RNA-seq Analysis requires specialized computational approaches to handle high-dimensional data [21] [20] [22]:

- Quality Control & Preprocessing: Filtering cells based on detected genes, mitochondrial content, and other QC metrics

- Dimensionality Reduction: Principal component analysis (PCA), t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE), and uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP)

- Clustering & Cell Type Identification: Graph-based clustering algorithms and marker gene detection for cell type annotation

- Trajectory Inference: Reconstruction of developmental pathways using tools like Monocle

- Cell-Cell Communication Analysis: Inference of ligand-receptor interactions using tools like CellPhoneDB

Machine learning has become increasingly integral to scRNA-seq analysis, with applications in clustering, dimensionality reduction, trajectory inference, and cell type annotation [22]. Advanced computational frameworks like SEURAT and Galaxy Europe Single Cell Lab provide essential bioinformatic tools for analyzing these complex datasets [20].

Applications and Synergistic Integration

Distinct and Complementary Applications

Each technology excels in addressing specific biological questions, with their applications reflecting their fundamental resolutions.

Key Applications of Bulk RNA-seq [13] [19]:

- Differential Gene Expression Analysis: Comparing gene expression profiles between different experimental conditions (disease vs. healthy, treated vs. control)

- Biomarker Discovery: Identifying molecular signatures for diagnosis, prognosis, or disease stratification

- Pathway Analysis: Investigating how sets of genes change collectively under various biological conditions

- Tissue-Level Transcriptomics: Obtaining global expression profiles from whole tissues, organs, or bulk-sorted cell populations

- Large Cohort Studies: Profiling large sample sets in biobank projects or population-level studies

Key Applications of Single-Cell RNA-seq [13] [20]:

- Characterizing Heterogeneous Populations: Identifying novel cell types, cell states, and rare cell populations

- Developmental Lineage Reconstruction: Tracing cellular differentiation pathways and developmental hierarchies

- Tumor Microenvironment Analysis: Deconvoluting complex tissue ecosystems and cell-cell interactions

- Cell-Type Specific Responses: Understanding how individual cells respond to stimuli, disease, or treatment

- Identifying Rare Driver Populations: Discovering rare cell types or transient states that play key roles in disease biology

Table 2: Application-Based Selection Guide

| Research Goal | Recommended Approach | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Expressionbetween conditions | Bulk RNA-seq [13] | Cost-effective for large sample numbers; statistical power for population-level differences |

| Novel Cell Type Discovery | Single-Cell RNA-seq [13] | Unbiased identification of previously unrecognized subpopulations |

| Rare Cell Population Detection(e.g., circulating tumor cells) | Single-Cell RNA-seq [18] | Sensitivity to identify ultra-rare populations that bulk methods would miss |

| Large Cohort Studies(e.g., clinical trials) | Bulk RNA-seq [13] [19] | Practical for processing hundreds to thousands of samples cost-effectively |

| Developmental Trajectories(e.g., embryogenesis) | Single-Cell RNA-seq [13] [18] | Reconstruction of differentiation pathways and lineage relationships |

| Pathway Analysisacross tissues | Bulk RNA-seq [13] | Comprehensive snapshot of average pathway activity across entire tissue |

| Cell-Cell Communicationin tissues | Single-Cell RNA-seq [23] [24] | Identification of ligand-receptor interactions between specific cell types |

| Therapeutic Target Identification | Integrated Approach [18] [24] | Bulk identifies candidate pathways; single-cell pinpoints specific cellular targets |

Synergistic Integration in Research

Rather than competing technologies, bulk and single-cell RNA-seq increasingly function as complementary tools that provide deeper insights when integrated [18] [24]. This synergy enables researchers to navigate efficiently between population-level trends and cellular-resolution mechanisms.

Successful Integration Framework [18]:

- Hypothesis Generation: Use bulk data to identify pathways of interest across entire tissues or conditions

- Cellular Resolution: Apply single-cell sequencing to pinpoint which specific cells drive the observed changes

- Validation & Scaling: Confirm single-cell discoveries across larger patient cohorts or timepoints with bulk sequencing

- Multi-omics Integration: Combine genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic layers for a systems-level view

A compelling example of this synergy comes from Huang et al. (2024), who leveraged both bulk and single-cell RNA-seq in healthy human B cells and leukemia clinical samples to identify developmental states driving resistance and sensitivity to asparaginase chemotherapy in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) [13]. Similarly, research on rheumatoid arthritis integrated scRNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq to elucidate macrophage heterogeneity, identifying STAT1 as a key regulator in disease pathogenesis through combined analytical approaches [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Solutions

Successful implementation of RNA sequencing technologies requires familiarity with key platforms, reagents, and computational resources that constitute the modern transcriptomics toolkit.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell Platforms | 10x Genomics Chromium System [13]Fluidigm C1 SystemPlate-based FACS [20] | Instrument-enabled cell partitioning and barcoding for high-throughput scRNA-seq |

| Library Prep Kits | 10x Genomics GEM-X Flex [13]10x Genomics Universal Multiplex Assays [13] | Preparation of sequencing-ready libraries with cell barcoding and UMIs |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Seurat [21] [23] [24]Monocle [23]CellPhoneDB [23] [24] | Analysis pipelines for scRNA-seq data including clustering, trajectory inference, and cell-cell communication |

| Quality Control Tools | Cell Ranger [21]DoubletFinder [24]InferCNV [23] | QC metrics, doublet detection, and copy number variation analysis for single-cell data |

| Data Integration Tools | Harmony Algorithm [24]CIBERSORT [23] | Batch effect correction and cell type deconvolution in single-cell and bulk data |

| Visualization Software | Loupe Browser (10x Genomics) [20]UCSC Cell Browser | Interactive visualization and exploration of single-cell datasets |

Signaling Pathway Case Study: STAT1 in Rheumatoid Arthritis

Recent research on rheumatoid arthritis (RA) provides an illustrative example of how integrated bulk and single-cell approaches can elucidate key signaling pathways in disease pathogenesis. This case study exemplifies the powerful synergy between these technologies.

Experimental Findings [24]:

- scRNA-seq Analysis: Revealed expanded population of Stat1+ macrophages in RA synovial tissue with inflammatory pathway enrichment

- Bulk RNA-seq Validation: Confirmed STAT1 upregulation across multiple RA patient cohorts (GSE12021, GSE55235, GSE55457, GSE77298, GSE89408)

- Functional Experiments: Demonstrated that STAT1 activation upregulates LC3 and ACSL4 while downregulating p62 and GPX4, suggesting modulation of autophagy and ferroptosis pathways

- Therapeutic Intervention: Fludarabine treatment reversed these changes, positioning STAT1 as a potential therapeutic target

This pathway analysis exemplifies how scRNA-seq identified a specific cellular subpopulation (Stat1+ macrophages) driving RA pathology, while bulk RNA-seq provided statistical validation across cohorts, together revealing a mechanistically coherent pathway with therapeutic implications.

The evolution of transcriptomics continues to advance toward higher resolution and integration. While bulk RNA-seq remains invaluable for population-level studies and large-scale screening, single-cell RNA-seq has fundamentally transformed our understanding of cellular heterogeneity and complexity [20] [25]. The future lies not in choosing between these approaches, but in strategically integrating them to leverage their complementary strengths [18].

Emerging technologies, particularly spatial transcriptomics, are now bridging the gap between single-cell resolution and tissue context, adding another dimension to the transcriptomics toolkit [25]. Meanwhile, advances in machine learning and artificial intelligence are addressing computational challenges in scRNA-seq data analysis, enabling more sophisticated integration of multi-omics datasets and accelerating the translation of single-cell discoveries into clinical applications [22].

For researchers and drug development professionals, this evolving landscape offers unprecedented opportunities to understand biological systems and disease mechanisms. By strategically employing both the "forest" perspective of bulk RNA-seq and the "tree" perspective of single-cell RNA-seq—and increasingly, the "geographic map" of spatial transcriptomics—we can continue to unravel the complexity of biological systems and advance the development of targeted therapeutics and precision medicine.

In the field of genomics, two principal methodologies have emerged for profiling gene expression: bulk RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq) and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). While both techniques utilize next-generation sequencing to capture a snapshot of the transcriptome, they differ fundamentally in their resolution and application. Bulk RNA-seq provides a population-level average of gene expression by sequencing RNA extracted from thousands to millions of cells simultaneously [13] [26]. In contrast, scRNA-seq enables researchers to measure gene expression at the resolution of individual cells, revealing the cellular heterogeneity masked in bulk measurements [13] [27]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive, step-by-step comparison of the experimental workflows for both approaches, detailing procedures from sample preparation through sequencing to empower researchers in selecting and implementing the appropriate method for their biological questions.

Bulk RNA-Seq Experimental Workflow

Sample Preparation and RNA Extraction

The bulk RNA-seq workflow begins with the collection of tissue or cell samples. Unlike single-cell methods, bulk protocols start with a population of cells that are processed together. RNA is extracted from the entire sample using methods that preserve RNA integrity, with careful consideration given to RNA quality and quantity [13]. For standard mRNA sequencing, extraction typically yields total RNA, which may undergo subsequent enrichment steps. The required sample input is substantially higher than for single-cell methods, as sufficient RNA must be obtained to represent the entire cell population [28].

Library Preparation: Whole Transcriptome vs. 3' mRNA-Seq

A critical distinction in bulk RNA-seq library preparation lies in the choice between whole transcriptome and 3' mRNA-seq approaches [28]:

Whole Transcriptome Sequencing: This approach utilizes random primers during cDNA synthesis, resulting in sequencing reads distributed across the entire length of transcripts. It requires either enrichment for polyadenylated RNA (poly(A) selection) or depletion of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) to prevent unnecessary sequencing of highly abundant ribosomal RNA. Whole transcriptome sequencing provides comprehensive information including alternative splicing, novel isoforms, fusion genes, and non-coding RNAs, but requires longer workflow times and deeper sequencing [28].

3' mRNA-Seq: This method focuses sequencing on the 3' end of transcripts through an initial oligo(dT) priming step, effectively performing in-preparation poly(A) selection. By generating one fragment per transcript, 3' mRNA-seq simplifies both library preparation and downstream data analysis. It is ideal for accurate gene expression quantification, particularly for large-scale studies or when working with challenging sample types like FFPE or degraded RNA [28].

Following RNA extraction and optional enrichment, the general workflow proceeds through cDNA synthesis, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification to create sequencing-ready libraries [13].

Sequencing and Data Analysis

Bulk RNA-seq libraries are typically sequenced to a depth sufficient for the research question, with differential gene expression studies often requiring 20-50 million reads per sample [28]. Following sequencing, data analysis involves quality control, read alignment to a reference genome, and gene expression quantification. Differential expression analysis between conditions then identifies genes that are statistically significantly upregulated or downregulated [13].

Table 1: Key Applications and Technical Requirements for Bulk RNA-seq

| Parameter | Whole Transcriptome Approach | 3' mRNA-Seq Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Alternative splicing, isoform discovery, fusion genes, non-coding RNAs [28] | Gene expression quantification, large-scale studies [28] |

| Library Prep Complexity | Higher (requires rRNA depletion or polyA selection) [28] | Lower (streamlined with oligo(dT) priming) [28] |

| Sequencing Depth | Higher (reads distributed across transcripts) [28] | Lower (1-5 million reads/sample often sufficient) [28] |

| Ideal Sample Types | High-quality RNA, discovery projects [28] | Degraded RNA, FFPE, high-throughput screens [28] |

| Data Analysis Complexity | Higher (splice-aware alignment, isoform resolution) [28] | Lower (read counting for expression) [28] |

Single-Cell RNA-Seq Experimental Workflow

Generation of Single-Cell Suspensions

The most critical and technically challenging step in scRNA-seq is the creation of high-quality single-cell suspensions [13]. This process varies significantly based on the starting material (e.g., fresh tissue, frozen tissue, or blood) and requires optimization to maximize cell viability while preserving transcriptional states. Tissue dissociation typically involves enzymatic or mechanical methods, or a combination of both [13]. Strict quality control is essential at this stage, with cell counting and viability assessment performed to ensure samples contain an appropriate concentration of viable cells and are free of clumps and debris [13]. Poor cell viability can lead to elevated ambient RNA, which compromises data quality.

Single-Cell Partitioning and Barcoding

Unlike bulk RNA-seq, scRNA-seq requires physical separation of individual cells before library preparation. The 10x Genomics Chromium system, a widely used platform, achieves this through microfluidic partitioning, where single cells are isolated into nanoliter-scale reaction vessels called Gel Beads-in-emulsion (GEMs) [13]. Within each GEM, gel beads dissolve to release oligonucleotides containing unique cellular barcodes that label all transcripts from an individual cell. Cell lysis occurs within the partition, allowing released RNA to be captured and barcoded [13]. This critical step ensures that all sequencing reads can be traced back to their cell of origin during data analysis. Alternative methods for single-cell isolation include plate-based approaches with FACS sorting [29].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Following barcoding, the products from all GEMs are pooled, and cDNA is synthesized and amplified. Sequencing libraries are then constructed to be compatible with next-generation sequencing platforms [13]. scRNA-seq experiments typically require significantly deeper sequencing than bulk experiments, as each cell must be sequenced adequately to detect a sufficient number of genes. Current high-throughput scRNA-seq methods can profile thousands to tens of thousands of cells in a single experiment, generating enormous datasets that require specialized computational tools for analysis [13] [26].

Special Considerations: Whole Transcriptome vs. Targeted scRNA-seq

A key methodological choice in single-cell research is between whole transcriptome and targeted gene expression profiling [29]:

Whole Transcriptome scRNA-seq: This unbiased approach aims to capture the entire transcriptome of each cell, making it ideal for discovery-oriented applications such as novel cell type identification, constructing cellular atlases, and uncovering novel disease pathways. However, it spreads sequencing reads thinly across all ~20,000 genes, making it susceptible to "gene dropout" where low-abundance transcripts fail to be detected [29].

Targeted scRNA-seq: This approach focuses sequencing resources on a predefined panel of tens to hundreds of genes. By concentrating reads on genes of interest, it achieves superior sensitivity and quantitative accuracy for those targets, minimizes gene dropout, and is more cost-effective for large-scale studies. The major limitation is its inability to detect genes outside the predefined panel [29].

Table 2: Comparison of Single-Cell RNA-seq Methodologies

| Parameter | Whole Transcriptome scRNA-seq | Targeted scRNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Discovery research, novel cell type identification, atlas building [29] | Targeted hypothesis testing, biomarker validation, large cohorts [29] |

| Sensitivity for Low-Abundance Transcripts | Lower (spreads reads across all genes) [29] | Higher (concentrates reads on gene panel) [29] |

| Cost Per Cell | Higher [29] | Lower [29] |

| Scalability for Large Cohorts | Lower cost and computational burden [29] | Higher (enables hundreds/thousands of samples) [29] |

| Computational Complexity | Higher (high-dimensional data) [29] | Lower (focused data analysis) [29] |

Comparative Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the key procedural differences between bulk and single-cell RNA-seq workflows from sample to sequence:

Experimental Design Considerations

Sample Size and Replication

Appropriate experimental design is crucial for generating meaningful transcriptomic data. For bulk RNA-seq, recent large-scale empirical studies in mouse models suggest that sample sizes of 6-7 represent a minimum, with 8-12 replicates per condition providing significantly more reliable results [30]. Studies with only 3-4 replicates show high false positive rates and fail to detect many truly differentially expressed genes [30]. For scRNA-seq, the concept of replication operates at two levels: the number of biological replicates (individuals) and the number of cells sequenced per sample. While there are no universal standards for scRNA-seq sample sizes, larger numbers of individuals provide greater biological generality, while sequencing more cells enables better characterization of rare cell populations [31].

Method Selection Guide

The choice between bulk and single-cell RNA-seq depends primarily on the research question:

Choose Bulk RNA-seq when:

- The research goal is to identify average expression changes across entire tissues or cell populations [13]

- Studying homogeneous cell populations where cellular heterogeneity is not a primary concern [26]

- Resource constraints exist (lower cost per sample) [13] [27]

- Analyzing large clinical cohorts or time-series studies [27]

Choose scRNA-seq when:

- Characterizing cellular heterogeneity, identifying rare cell types, or discovering novel cell states [13] [26]

- Investigating complex tissues with diverse cell types (e.g., tumors, brain, developing tissues) [13]

- Tracing developmental trajectories or lineage relationships [13]

- Understanding cell-specific responses to perturbations or disease [13]

Complementary Approaches

Bulk and single-cell RNA-seq are not mutually exclusive; they can be powerfully combined in the same research program [13] [23]. For example, bulk RNA-seq can identify global expression changes between conditions, while follow-up scRNA-seq can determine which specific cell types drive these changes [13]. Similarly, discoveries from exploratory scRNA-seq studies (e.g., novel cell types or biomarkers) can be validated across large patient cohorts using targeted scRNA-seq or bulk RNA-seq [29]. A 2024 study on B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia exemplified this integrated approach, using both technologies to identify distinct cellular states driving chemotherapy resistance [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for RNA-seq Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Function | Bulk RNA-seq | Single-Cell RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | Preserve RNA integrity post-collection [32] | Essential | Critical (due to longer processing) |

| Cell Dissociation Kits | Tissue dissociation into single cells [13] | Not required | Essential (enzyme/mechanical) |

| Viability Stains | Assess cell viability pre-processing [13] | Optional | Critical (e.g., trypan blue) |

| Poly(dT) Magnetic Beads | mRNA enrichment via polyA tail [28] | Required for 3' mRNA-seq | Incorporated in barcoded beads |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Remove abundant ribosomal RNA [28] | Required for whole transcriptome | Not typically used |

| Barcoded Gel Beads | Label transcripts with cell barcodes [13] | Not required | Essential (e.g., 10x Genomics) |

| Partitioning Chips/Instrument | Isolate single cells in emulsions [13] | Not required | Essential (e.g., Chromium X) |

| Library Preparation Kits | Prepare sequencing-ready libraries [28] | Multiple options available | Platform-specific kits |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers | Correct for PCR amplification bias [13] | Optional | Essential for quantification |

Bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing offer complementary approaches for studying gene expression, each with distinct workflow requirements and applications. Bulk RNA-seq provides a cost-effective method for identifying population-level expression changes, with choices between whole transcriptome and 3' mRNA-seq approaches impacting the biological information obtained. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals cellular heterogeneity through more complex workflows requiring single-cell suspension, barcoding, and partitioning, with options for whole transcriptome or targeted profiling. The decision between these technologies should be guided by the specific research question, resources, and desired resolution. As both technologies continue to evolve, their integrated application promises to further unravel the complexity of biological systems.

In the field of transcriptomics, bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) represent complementary paradigms for quantifying gene expression. Bulk RNA-seq provides a population-average readout, measuring the composite gene expression profile from a mixture of cells [13] [9]. In contrast, single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) resolves expression to the level of individual cells, capturing the cell-to-cell variation that is averaged out in bulk approaches [33] [2]. This technical guide explores the interpretive frameworks for these key outputs, enabling researchers to select the appropriate tool for their biological questions, particularly in drug discovery and development.

Fundamental Technical Differences and Output Interpretations

The core difference between these methodologies lies not just in protocol, but in the fundamental nature of the data they generate and the biological conclusions they support.

Bulk RNA-seq: The Population Average

- The "Forest" View: Bulk RNA-seq treats a tissue or cell population as a single entity [13]. The final output is an average expression level for each gene across all cells in the sample.

- Interpretation of Outputs: Results represent the global transcriptional state of the sample. A highly expressed gene in bulk data could mean it is moderately expressed in all cells or very highly expressed in a rare subpopulation. This ambiguity is its primary limitation [9] [2].

- Ideal Use Cases: Identifying large, consistent expression changes between conditions (e.g., diseased vs. healthy tissue), transcriptome annotation, and detecting alternative splicing or gene fusions [13] [34].

Single-Cell RNA-seq: The Cellular Resolution

- The "Individual Tree" View: scRNA-seq profiles the transcriptome of each cell individually [13]. The key output is a cell-by-gene expression matrix, where each value represents the expression level of a specific gene in a specific cell.

- Interpretation of Outputs: This matrix enables the dissection of cellular heterogeneity. Researchers can identify distinct cell types and states, trace developmental lineages, and discover rare cell populations that would be statistically or biologically masked in bulk data [33] [9].

- Ideal Use Cases: Characterizing complex tissues (e.g., tumor microenvironments, immune cells), identifying novel cell types, studying developmental trajectories, and understanding drug resistance mechanisms [35] [2].

Table 1: Core Methodological and Output Comparison of Bulk vs. Single-Cell RNA-seq

| Feature | Bulk RNA-seq | Single-Cell RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population average [13] [9] | Individual cell level [13] [9] |

| Key Output | Average gene expression profile for the sample [13] | Cell-by-gene expression matrix [13] |

| Heterogeneity Insight | Masks cellular heterogeneity [9] [2] | Reveals cellular heterogeneity, rare cell types, and continuous states [9] [2] |

| Cost per Sample | Lower [9] | Significantly higher [9] |

| Data Complexity | Lower, more established analytical pipelines [9] | Higher, requires specialized tools for sparse data [35] [9] |

| Gene Detection Sensitivity | Higher per sample, detects more lowly expressed genes [9] | Lower per cell due to dropout events, but deeper per cell type [9] |

| Sample Input | Higher RNA input requirements [9] | Can work with very low input, down to single cells [9] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

The journey from biological sample to interpretable data involves distinct experimental protocols for bulk and single-cell RNA-seq.

Bulk RNA-seq Workflow

The bulk RNA-seq protocol is a well-established and relatively straightforward process:

- Sample Lysis and RNA Extraction: The entire tissue or cell population is lysed, and total RNA is extracted [13].

- RNA Selection: Either mRNA is enriched using poly-A selection, or ribosomal RNA is depleted to access other RNA species [13].

- Library Preparation: The RNA is reverse-transcribed into cDNA, adapters are ligated, and the library is amplified to create a sequencing-ready pool representing the entire sample's transcriptome [13] [2].

- Sequencing and Analysis: The library is sequenced on an NGS platform, and reads are aligned to a reference genome to quantify gene expression levels for the sample as a whole [13].

Single-Cell RNA-seq Workflow

The scRNA-seq workflow introduces critical steps to preserve single-cell resolution:

- Single-Cell Suspension: The tissue is dissociated into a viable suspension of single cells, requiring careful enzymatic or mechanical processing [13] [2].

- Cell Partitioning and Barcoding: Individual cells are isolated into nanoliter-scale reactions, typically droplets (GEMs in the 10x Genomics platform) or microwells. This is a critical step where each cell's RNA is tagged with a unique cell barcode that distinguishes its origin from all other cells. Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) are also added to correct for PCR amplification bias [13] [2].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: As in bulk RNA-seq, barcoded cDNA is amplified and prepared for sequencing. The resulting library contains transcriptome data from thousands of cells, multiplexed together [13].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: A specialized computational pipeline (e.g., Cell Ranger) first uses the cell barcodes to demultiplex the data, grouping all reads by their cell of origin to reconstruct the single-cell expression matrix. Subsequent analysis involves quality control, clustering, and cell type annotation [13] [35].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

The choice between bulk and single-cell approaches has profound implications for the efficiency and success of drug development pipelines.

Table 2: Application-Specific Advantages in Drug Discovery

| Drug Discovery Stage | Bulk RNA-seq Application | Single-Cell RNA-seq Application |

|---|---|---|

| Target Identification | Differential expression analysis between diseased and healthy bulk tissues to find consistently altered pathways [13] [35]. | Identification of novel cell types or cell states that drive disease within a complex tissue. Discovery of cell-type-specific disease genes [35] [16]. |

| Target Validation | Functional studies in cell lines or animal models using bulk readouts of pathway activity [35]. | High-plex CRISPR screens coupled with scRNA-seq (Perturb-seq) to map gene regulatory networks and understand the function of target genes at single-cell resolution [35]. |

| Biomarker Discovery | Identification of mRNA expression signatures from bulk tissue that correlate with disease status or progression [13] [2]. | Definition of more accurate, cell-type-specific biomarkers. Precise patient stratification based on the abundance or state of specific cell subpopulations (e.g., T-cell states) [35] [16]. |

| Mechanism of Action | Profiling overall transcriptomic changes in response to drug treatment in cell populations [35]. | Uncovering heterogeneous responses to therapy, identifying rare, drug-resistant subpopulations, and understanding how different cells in a tumor microenvironment respond [35] [2]. |

| Toxicity & Safety | Assessing gross transcriptional changes in organs indicative of toxicity [16]. | Pinpointing the specific cell types that are most susceptible to drug-induced toxicity [16]. |

Case Study: Integrating Bulk and Single-Cell Data for Predictive Power

A powerful emerging trend is the integration of bulk and single-cell data to leverage their respective strengths. For instance, a 2024 retrospective analysis of known drug target genes found that cell type-specific expression of a target in disease-relevant tissues, a discovery enabled by scRNA-seq, was a robust predictor of the target's success in progressing from Phase I to Phase II clinical trials [16]. This demonstrates how single-cell resolution can deconvolute the bulk expression signals to provide more precise and predictive insights.

Furthermore, computational frameworks like scDEAL (single-cell Drug rEsponse AnaLysis) use deep transfer learning to predict single-cell drug responses by integrating knowledge from large-scale bulk RNA-seq databases of cancer cell lines (e.g., GDSC, CCLE). This approach harmonizes bulk and single-cell data, transferring trustworthy gene-drug relations from the bulk level to predict response and resistance mechanisms at the single-cell level [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Platforms

Successful implementation of RNA-seq technologies relies on a suite of specialized reagents and instruments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Platforms

| Item / Platform | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | An integrated microfluidic system (e.g., Chromium X) for partitioning thousands of single cells into Gel Beads-in-emulsion (GEMs) for 3' or 5' gene expression library prep [13] [2]. |

| Parse Biosciences Evercode | A combinatorial barcoding method that performs scRNA-seq without specialized instruments, enabling very high-throughput experiments (e.g., millions of cells across thousands of samples) [16]. |

| Gel Beads & Barcoded Oligos | Microbeads coated with millions of oligonucleotides containing cell barcodes, UMIs, and poly-dT primers. Critical for labeling all mRNA from a single cell with the same barcode during reverse transcription within a GEM [13] [2]. |

| Enzymatic Mixes (RT, PCR) | Specialized reverse transcriptase and DNA polymerase mixes optimized for the unique challenges of single-cell workflows, including working with very low starting RNA quantities [13]. |

| Cell Suspension Kits | Optimized kits containing enzymes and buffers for the gentle dissociation of specific tissues (e.g., tumors, brain) into high-viability single-cell suspensions, a critical first step for scRNA-seq [13]. |

| Mission Bio Tapestri | A platform designed for targeted single-cell DNA and multi-omics sequencing. The cited SDR-seq method was adapted from this technology to simultaneously profile genomic DNA loci and RNA in thousands of single cells [37]. |

Bulk and single-cell RNA-seq are not mutually exclusive technologies but are complementary tools in the modern biologist's arsenal. Bulk RNA-seq remains a powerful, cost-effective method for answering questions about population-level, averaged gene expression. Single-cell RNA-seq is indispensable for dissecting cellular heterogeneity, discovering rare cell types, and understanding complex biological systems at their fundamental resolution. The future of transcriptomics, especially in precision medicine and drug discovery, lies in strategically combining these approaches and leveraging computational integration to gain a comprehensive picture of health and disease that is both broad and deep.

Strategic Applications: Choosing the Right Tool for Your Research Goal

In the evolving landscape of genomics, bulk RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq) remains a foundational technology for studying gene expression across a population of cells. This method provides a population-level perspective by measuring the average gene expression profile from a tissue sample or cell population, making it an indispensable tool for numerous research and clinical applications [2] [9]. Despite the emergence of higher-resolution single-cell technologies, bulk RNA-seq continues to offer distinct advantages where a holistic view of transcriptional activity is required. Its utility is marked by cost-effectiveness, established analytical simplicity, and proven robustness in identifying global expression patterns across experimental conditions [13] [9]. This technical guide delineates the core use cases where bulk RNA-seq provides irreplaceable population-level insights, positioning it within the broader context of transcriptomics research.

Core Applications and Use Cases of Bulk RNA-seq

Bulk RNA-seq is the preferred methodology when the research question targets the collective behavior of a cell population rather than its constituent cellular diversity. Its applications are widespread across basic research, clinical diagnostics, and drug development.

Differential Gene Expression Analysis

This is one of the most prevalent applications of bulk RNA-seq. It involves comparing gene expression profiles between different experimental conditions—such as diseased versus healthy tissues, treated versus control samples, or across various time points in a time-course experiment [13] [38]. By providing an average readout, bulk RNA-seq is highly effective at identifying subtle, consistent changes in gene expression that might be obscured by technical noise in single-cell data [26]. This capability is fundamental for:

- Discovering RNA-based biomarkers and molecular signatures for diagnosis, prognosis, or patient stratification [13].

- Investigating collective changes in gene pathways and networks under various biological conditions [13].

Transcriptome Profiling of Tissues and Large Cohorts

Bulk RNA-seq is ideally suited for projects that require a global expression profile from whole tissues, organs, or large sets of samples [13]. Its cost-effectiveness and analytical straightforwardness make it feasible for:

- Large cohort studies or biobank projects where the primary goal is to link transcriptomic profiles to clinical or phenotypic data [13].

- Establishing baseline transcriptomic profiles for new or understudied organisms or tissues [13].

- Supporting deconvolution studies, where its data can be used alongside single-cell RNA-seq reference maps to infer cell type proportions in complex tissues [13].

Detection and Characterization of Novel Transcripts

Owing to its typically higher sequencing depth per sample and more comprehensive coverage of transcripts, bulk RNA-seq is a powerful tool for transcriptome annotation and discovery [2] [13]. Key applications include:

- Identifying and characterizing isoforms, alternative splicing events, gene fusions, long non-coding RNAs, and point mutations [2] [13].

- Detecting various forms of genomic alterations, including gene fusions, substitutions, and indels, sometimes revealing alterations not detected by DNA-based approaches [2]. FoundationOne Heme is a prominent example of a clinical test that leverages this multi-faceted capability for therapy selection in oncology [2].

Disease Research and Biomarker Discovery

In disease research, particularly oncology, bulk RNA-seq has broad utilities. It has been instrumental in cancer classification, the discovery of diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers, and optimizing therapeutic strategies [2] [9] [38]. For instance, comprehensive analyses of thousands of cancer samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) have utilized bulk RNA-seq to detect novel and clinically relevant gene fusions driving cancer pathogenesis [9].

Table 1: Key Use Cases and Supporting Methodologies for Bulk RNA-seq

| Use Case | Experimental Objective | Typical Analytical Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Expression | Identify genes with significant expression changes between conditions (e.g., disease vs. healthy). | DESeq2, EdgeR [38] [39] |

| Biomarker Discovery | Find gene expression signatures correlated with diagnosis, prognosis, or treatment response. | Differential expression analysis, clustering, machine learning [2] [38] |

| Transcriptome Characterization | Annotate isoforms, detect gene fusions, and discover novel transcripts. | Cufflinks, StringTie, fusion detection algorithms (e.g., DEEPEST) [2] [40] |

| Large Cohort Profiling | Establish global expression profiles across large sample sets (e.g., population studies). | Principal Component Analysis (PCA), clustering, WGCNA [13] [4] [39] |

The Bulk RNA-seq Workflow: From Sample to Insight

A standardized workflow is crucial for generating reliable and interpretable bulk RNA-seq data. The process extends from careful experimental design through computational analysis.

Experimental Design and Sample Preparation

The process begins with careful planning. Researchers must define objectives clearly and select appropriate sample groups, ensuring the inclusion of proper controls and biological replicates to account for natural variation [38] [39]. Key steps include:

- RNA Extraction: RNA is isolated from the tissue or cell population using methods like column-based kits or TRIzol reagents. Preventing RNA degradation and contamination is critical at this stage [38].

- Quality Control: The quality of the extracted RNA is assessed using tools like a Bioanalyzer or Nanodrop. A high RNA Integrity Number (RIN) is a key indicator of sample suitability for sequencing [38] [39].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

This phase converts RNA into a format compatible with sequencing platforms.

- Reverse Transcription: RNA is converted into more stable complementary DNA (cDNA) [38].

- Fragmentation and Adapter Ligation: cDNA is fragmented into smaller pieces, and short DNA sequences (adapters) are ligated to the ends. These adapters facilitate binding to the sequencing platform and sample identification [2] [38].

- Amplification and Sequencing: The library is amplified via PCR and loaded onto a high-throughput sequencer like an Illumina system, which generates millions of short reads [38].

Bioinformatics Analysis

The raw sequencing data (FASTQ files) undergoes a multi-step computational process:

- Quality Control: Tools like FastQC evaluate read quality, followed by trimming of low-quality bases and adapters using software like Trimmomatic [40] [38].

- Read Alignment: Cleaned reads are mapped to a reference genome or transcriptome using spliced aligners such as STAR or HISAT2 [40] [38].

- Expression Quantification: Tools like featureCounts or HTSeq count the reads aligned to each gene, generating a raw count expression matrix [40] [38].

- Normalization: Raw counts are normalized using methods like TPM or DESeq2's median-of-ratios to account for differences in sequencing depth and library composition [38] [39].

- Differential Expression & Analysis: Statistical models in tools like DESeq2 or EdgeR identify significantly differentially expressed genes between conditions [38] [39]. Subsequent functional enrichment analysis (using tools like DAVID or GSEA) interprets the biological meaning of the results [38].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and key decision points in a bulk RNA-seq experiment.

Bulk RNA-seq vs. Single-Cell RNA-seq: A Strategic Comparison

The choice between bulk and single-cell RNA-seq is not a matter of one being superior to the other, but rather which technology is best suited to address the specific biological question at hand.

Key Differentiating Factors

- Resolution and Heterogeneity: Bulk RNA-seq provides an average expression profile, masking cellular heterogeneity. In contrast, scRNA-seq reveals distinct cell types, rare cell populations, and continuous cell states within a sample [2] [13] [9].

- Cost and Throughput: Bulk RNA-seq is significantly more affordable, typically costing about one-tenth of scRNA-seq per sample, making it practical for large-scale studies [9]. The per-sample cost of bulk is lower, and its data analysis is less computationally intensive [13] [9].

- Gene Detection Sensitivity: While scRNA-seq can struggle to detect low-abundance transcripts due to "dropout" events, bulk RNA-seq, with its pooling of RNA from many cells, often has higher sensitivity for detecting subtle expression changes of such genes [9] [26].

Choosing the Right Tool for the Question

The decision flowchart in Section 3 provides high-level guidance. The table below offers a direct comparison to aid in strategic selection.

Table 2: Strategic Comparison of Bulk RNA-seq and Single-Cell RNA-seq

| Feature | Bulk RNA-seq | Single-Cell RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population average [13] [9] | Individual cell [13] [9] |

| Ideal for | Homogeneous samples, differential expression, large cohorts [13] [9] | Heterogeneous tissues, rare cell discovery, developmental trajectories [13] [9] |

| Cost per Sample | Low (~1/10th of scRNA-seq) [9] | High [9] |

| Data Complexity | Lower, more straightforward analysis [9] | High, requires specialized computational methods [9] |

| Cell Heterogeneity | Masks heterogeneity [13] [9] | Reveals heterogeneity [13] [9] |

| Rare Cell Detection | Limited, signals are diluted [9] | Possible, can identify rare populations [9] |

Successful execution of a bulk RNA-seq experiment relies on a suite of trusted reagents, kits, and software tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Bulk RNA-seq

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation Kits | Column-based kits (e.g., PicoPure), TRIzol reagent [38] [39] | Extract high-quality, intact total RNA from tissue or cell samples. |

| RNA QC Instruments | Bioanalyzer (Agilent), TapeStation, Nanodrop [38] [39] | Assess RNA concentration, purity, and integrity (RIN) prior to library prep. |

| Library Prep Kits | NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit, NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Kit [39] | Convert RNA to sequencing-ready cDNA libraries; enrich for mRNA or deplete rRNA. |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NextSeq, NovaSeq [38] | Perform high-throughput sequencing to generate raw read data (FASTQ files). |

| Alignment Software | STAR, HISAT2, TopHat2 [40] [38] | Map sequenced reads to a reference genome or transcriptome. |

| Quantification Tools | featureCounts, HTSeq [40] [38] | Count the number of reads mapped to each gene to create an expression matrix. |

| DE Analysis Packages | DESeq2, EdgeR [38] [39] | Perform statistical analysis to identify differentially expressed genes. |

Bulk RNA-seq remains a powerful, cost-effective, and robust technology for generating population-level transcriptomic insights. Its strengths in differential expression analysis, large-scale profiling, and comprehensive transcript detection ensure its continued relevance in the genomics toolbox. As the field progresses, bulk RNA-seq is not being replaced but is rather being complemented by single-cell and spatial technologies. The most powerful studies often involve an integrated approach, using bulk RNA-seq to identify large-scale expression patterns and scRNA-seq to dissect the cellular sources of those patterns [4] [24]. By understanding its key use cases and methodological principles, researchers can strategically leverage bulk RNA-seq to advance our understanding of biology and disease.

The fundamental unit of biology is the cell, and understanding the behavior of individual cells within a complex tissue is crucial for unraveling the mechanisms of development, disease, and homeostasis. For years, bulk RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq) served as the primary tool for transcriptome analysis, providing a population-averaged view of gene expression [13] [2]. While invaluable for identifying overall expression trends, this approach inherently masks cellular heterogeneity, as it measures the average expression profile across thousands to millions of disparate cells [41]. The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized this paradigm by enabling researchers to measure gene expression in individual cells, thereby revealing the cellular diversity, identifying rare cell types, and uncovering novel cell states that drive biological processes [42] [43]. This technical guide will delineate the specific scenarios where scRNA-seq is not merely an option but a necessity, particularly when investigating heterogeneous samples. Framed within the broader comparison of bulk versus single-cell methodologies, this whitepaper provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a rigorous framework for selecting the appropriate tool to address their core biological questions.

Bulk vs. Single-Cell RNA-seq: A Technical Comparison

To make an informed choice between these two technologies, one must first understand their fundamental differences in output and capability. Bulk RNA-seq processes RNA from an entire tissue sample or cell population, resulting in a single, composite gene expression profile representing the average of all constituent cells [13] [34]. In contrast, scRNA-seq isolates individual cells, creates barcoded libraries for each, and sequences them in parallel, generating thousands of distinct transcriptome profiles from a single sample [2] [43].

Table 1: Core Technical Differences Between Bulk and Single-Cell RNA-seq

| Feature | Bulk RNA-seq | Single-Cell RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population-average | Single-cell |

| Ability to Detect Heterogeneity | No, masks differences | Yes, resolves cellular diversity |

| Identification of Rare Cell Types | Limited, can be obscured | Excellent (down to <1% abundance) |

| Primary Applications | Differential expression between conditions, transcriptome annotation, splicing analysis [13] [34] | Cell type identification, developmental trajectories, tumor microenvironment mapping, rare cell discovery [13] [2] [34] |

| Typical Cost per Sample | Lower | Higher |

| Data Complexity | Lower, established analysis pipelines | High, requires specialized bioinformatics expertise [43] |