Bulk vs Single-Cell RNA Sequencing: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article provides a definitive comparison of bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing for researchers and drug development professionals.

Bulk vs Single-Cell RNA Sequencing: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a definitive comparison of bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles, key technical differences, and cost considerations of each method. A detailed examination of their respective applications—from differential expression analysis to dissecting tumor heterogeneity—guides appropriate experimental design. The content also addresses common challenges, including data analysis complexity and sample preparation, and explores how integrating both approaches can validate findings and power new discoveries in precision medicine.

Understanding the Core Principles: From Population Averages to Single-Cell Resolution

Bulk RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq) is a next-generation sequencing (NGS)-based method that measures the whole transcriptome across a population of thousands to millions of cells [1]. This approach provides a population-level perspective on gene expression, generating an average expression profile for all cells within a sample [1]. Unlike single-cell methods that resolve individual cellular contributions, bulk RNA-seq merges signals from all cell types present, making it analogous to viewing an entire forest rather than examining individual trees [1]. This technique has become a fundamental tool in transcriptomics, enabling researchers to quantify gene expression patterns, identify differentially expressed genes, and discover biomarkers across various biological conditions.

Key Technological Principles

The core principle of bulk RNA-seq involves analyzing RNA extracted from entire tissue samples or cell populations, which inherently combines transcripts from all cell types present [2]. During analysis, the resulting data represents the average gene expression across this heterogeneous mixture [1]. This contrasts with single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), which partitions individual cells before sequencing to resolve cell-to-cell variation [3]. The population averaging in bulk RNA-seq makes it particularly powerful for detecting overall expression trends but limits its ability to resolve cellular heterogeneity within samples [1].

Direct Comparison: Bulk vs. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

Table 1: Technical and practical comparison between bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing approaches

| Feature | Bulk RNA Sequencing | Single-Cell RNA Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population-level average [1] | Individual cell level [3] |

| Cost per Sample | Lower (~$300/sample) [3] | Higher (~$500-$2000/sample) [3] |

| Data Complexity | Lower, less computationally intensive [3] | Higher, requires specialized computational methods [3] |

| Cell Heterogeneity Detection | Limited, masks cellular subtypes [1] | High, identifies rare cell populations [3] |

| Sample Input Requirement | Higher (micrograms of RNA) [3] | Lower (single cells or picograms of RNA) [3] |

| Gene Detection Sensitivity | Higher genes detected per sample [3] | Lower genes detected per cell [3] |

| Splicing Analysis | More comprehensive for isoform detection [1] | Limited due to sparse data per cell [3] |

| Experimental Workflow | Simpler sample preparation [1] | Complex single-cell isolation required [1] |

Table 2: Performance characteristics and optimal use cases for each method

| Characteristic | Bulk RNA Sequencing | Single-Cell RNA Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Ideal Applications | Differential expression between conditions, biomarker discovery, large cohort studies [1] | Cellular heterogeneity mapping, rare cell identification, developmental trajectories [1] |

| Technical Challenges | Cannot resolve cellular origins of expression signals [1] | Dropout events, sparsity, higher technical noise [3] |

| Data Output | Gene counts representing population averages [4] | Gene counts per cell with cell barcodes [1] |

| Replicate Concordance | Spearman correlation >0.9 between isogenic replicates [5] | Higher variability between technical replicates |

| Recommended Sequencing Depth | 20-30 million aligned reads per sample [5] | 5-50 thousand reads per cell [5] |

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Bulk RNA-Seq Workflow and Protocols

The standard bulk RNA-seq experimental workflow follows a structured pathway from sample collection to data interpretation, with critical quality control checkpoints at each stage.

Standardized Processing Pipelines

Reproducible processing of bulk RNA-seq data typically follows established pipelines such as the ENCODE Bulk RNA-seq pipeline, which provides standardized methods for alignment and quantification [5]. This pipeline can process both paired-end and single-end sequencing data, with specific quality thresholds including minimum read lengths of 50 base pairs and requirements for replicate concordance (Spearman correlation >0.9 between isogenic replicates) [5].

The nf-core RNA-seq workflow represents another robust pipeline option that implements best practices for comprehensive analysis [6]. This workflow typically employs a hybrid approach using STAR for splice-aware alignment to the genome followed by Salmon for alignment-based quantification, balancing the need for quality control metrics with accurate expression estimation [6]. This combination leverages the strengths of both tools: STAR provides detailed alignment information for quality checks, while Salmon uses statistical models to handle uncertainty in read assignment and count estimation [6].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Key reagents, tools, and their functions in bulk RNA-seq experiments

| Category | Item | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Poly(A) selection beads or rRNA depletion kits | mRNA enrichment from total RNA [7] |

| ERCC Spike-in controls | External RNA controls for normalization [5] | |

| Library Preparation | Fragmentation enzymes | RNA or cDNA fragmentation to optimal size [7] |

| Reverse transcriptase | cDNA synthesis from RNA templates [1] | |

| Adapter ligation enzymes | Addition of sequencing adapters [7] | |

| Computational Tools | STAR aligner | Spliced alignment of reads to reference genome [2] |

| Salmon | Pseudoalignment and transcript quantification [6] | |

| DESeq2/edgeR | Differential expression analysis [4] [7] | |

| FastQC | Quality control of raw sequencing data [2] |

Data Analysis and Visualization Framework

Differential Expression Analysis

The statistical foundation of bulk RNA-seq analysis relies on identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between experimental conditions. The DESeq2 package implements a negative binomial generalized linear model to test for differential expression, while accounting for overdispersion in count data and library size differences [4]. The workflow involves several key steps:

- Count Matrix Preprocessing: Raw count data is filtered to remove genes with low expression across samples [4]

- Normalization: DESeq2 estimates size factors to account for differences in sequencing depth between samples [4]

- Dispersion Estimation: Gene-wise dispersion estimates are calculated to model variance-mean dependence [4]

- Statistical Testing: The Wald test is typically applied to compare expression between groups [4]

- Multiple Testing Correction: Benjamini-Hochberg procedure controls false discovery rate (FDR) across thousands of tests [4]

For effect size estimation, the apeglm package provides empirical Bayes shrinkage estimators for log2 fold-change values, preventing inflation of fold-changes for lowly expressed genes and providing more biologically meaningful estimates [4].

Quality Assessment and Visualization

Comprehensive quality assessment is critical for ensuring reliable bulk RNA-seq results. The following visualization approaches help researchers evaluate data quality and interpret results:

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is particularly valuable for visualizing global expression patterns and assessing sample relationships [4]. In PCA plots, samples grouping closely together indicate high reproducibility, while separation along principal components often corresponds to experimental conditions or batch effects [7]. Additional visualization methods include:

- Volcano plots: Display statistical significance versus magnitude of expression change [4]

- Heatmaps: Visualize expression patterns of DEGs across samples [4]

- Parallel coordinate plots: Show expression patterns of individual genes across samples, helping identify consistent patterns between replicates and divergent patterns between treatments [8]

Applications and Integration with Single-Cell Approaches

Complementary Applications in Research

Bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing serve complementary roles in modern transcriptomics research. Bulk RNA-seq excels in multiple applications:

- Differential gene expression analysis: Identifying genes upregulated or downregulated between conditions (e.g., disease vs. healthy, treated vs. control) [1]

- Biomarker discovery: Finding molecular signatures for diagnosis, prognosis, or patient stratification [1]

- Pathway analysis: Investigating how sets of genes change collectively under various biological conditions [1]

- Large cohort studies: Profiling transcriptomes in biobank-scale projects where cost considerations are paramount [1]

Integrated Study Designs

Forward-thinking research increasingly combines both approaches to leverage their complementary strengths [3]. Huang et al. (2024) demonstrated this powerful integration in their study of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), where they used both bulk and single-cell RNA-seq to identify developmental states driving resistance and sensitivity to the chemotherapeutic agent asparaginase [1]. In such integrated designs:

- Bulk RNA-seq provides the broad context of overall expression changes across samples

- Single-cell RNA-seq deconvolutes heterogeneous samples to identify specific cell populations driving bulk-level signals [1]

- Cross-validation between platforms increases confidence in findings

- Bulk data can support deconvolution studies using single-cell RNA-seq reference maps [1]

This synergistic approach enables researchers to both observe forest-level patterns and examine individual trees, providing a comprehensive understanding of complex biological systems.

The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) represents a transformative milestone in molecular biology, enabling researchers to investigate gene expression profiles at unprecedented resolution. While traditional bulk RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq) provides a population-averaged view of gene expression across entire tissue samples, scRNA-seq unveils the cellular heterogeneity hidden within these populations [1] [9]. This technological evolution has fundamentally altered our understanding of biological systems, revealing complex cellular ecosystems that drive development, homeostasis, and disease pathogenesis.

The fundamental distinction between these approaches lies in their resolution. Bulk RNA-seq analyzes RNA from thousands to millions of cells simultaneously, yielding a composite expression profile that averages signals across all cell types present in the sample [1] [9]. In contrast, scRNA-seq partitions individual cells into separate reaction vessels, allowing for the precise measurement of gene expression in each cell independently [1]. This capability has proven particularly valuable for studying complex tissues like the brain, immune system, and tumors, where diverse cell types interact to create functional networks and disease states [10] [11].

Technical Foundations: Methodological Comparisons

Core Workflow Differences

The experimental workflows for bulk and single-cell RNA-seq diverge significantly at the initial sample preparation stage. In bulk RNA-seq, the entire tissue or cell population is processed collectively for RNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing [1]. This consolidated approach provides an averaged gene expression readout but obscures cell-to-cell variation.

In contrast, scRNA-seq requires the generation of viable single-cell suspensions through enzymatic or mechanical dissociation of tissues, followed by careful quality control to ensure cell viability and integrity [1] [10]. The partitioned cells are then individually barcoded during the reverse transcription step, enabling thousands of cells to be pooled for sequencing while maintaining the ability to trace transcripts back to their cell of origin [1]. For the 10x Genomics platform, this partitioning occurs within microfluidic chips on specialized instruments that isolate single cells into gel bead-in-emulsions (GEMs) where cell lysis and barcoding occur [1].

Comparative Workflow Visualization

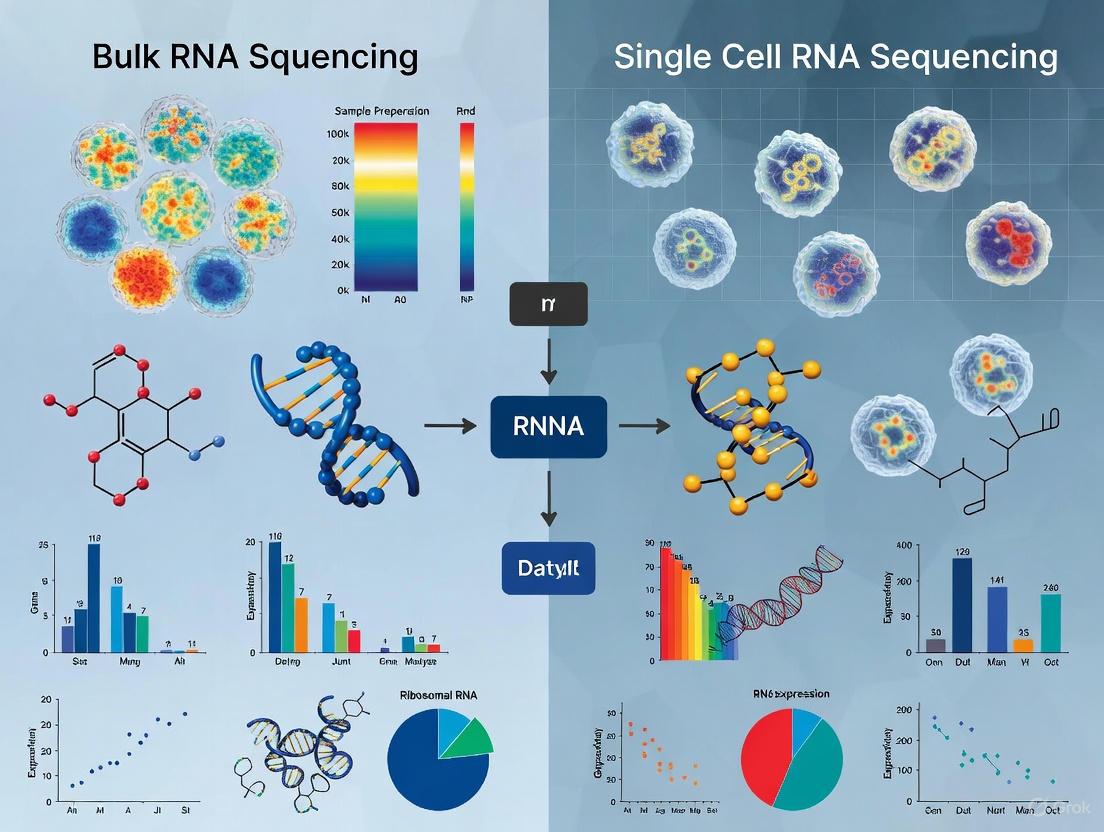

The following diagram illustrates the key procedural differences between bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing workflows:

Comprehensive Method Comparison

Table 1: Technical and practical comparison between bulk and single-cell RNA-seq

| Parameter | Bulk RNA-Seq | Single-Cell RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population-averaged expression [1] | Individual cell resolution [1] |

| Cell Heterogeneity | Masks cellular diversity [9] | Reveals cellular heterogeneity and rare cell types [1] [11] |

| Cost per Sample | Lower cost [1] [12] | Higher cost, though decreasing [1] |

| Sample Input | Entire tissue/cell population | Viable single-cell suspension [1] [10] |

| Technical Complexity | Straightforward workflow with established protocols [12] | Complex sample prep requiring specialized equipment [1] |

| Data Output | Single expression profile per sample | Thousands of expression profiles (one per cell) [1] |

| Ideal Applications | Differential expression between conditions, biomarker discovery [1] | Cell type identification, developmental trajectories, tumor heterogeneity [1] [11] |

| Limitations | Cannot resolve cell-type-specific signals in heterogeneous samples [1] | Sensitive to sample quality, higher computational demands [1] [10] |

Experimental Design and Performance Benchmarking

Method Selection for Specific Research Questions

Choosing between bulk and single-cell RNA-seq depends primarily on the research question and available resources. Bulk RNA-seq remains the preferred method for studies requiring cost-effective analysis of many samples, such as large cohort studies or time-series experiments where the primary goal is to identify overall expression differences between conditions [1] [12]. Its established protocols and analytical pipelines make it particularly suitable for projects with limited bioinformatics support.

scRNA-seq is indispensable when investigating cellular heterogeneity, identifying novel cell types or states, or reconstructing developmental trajectories [1] [11]. Recent technological advances have progressively reduced barriers to adoption through optimized assays like the 10x Genomics GEM-X Flex, which lowers per-cell costs and enables higher-throughput studies [1]. For clinical samples with limitations in immediate processing, single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) provides a valuable alternative that allows sample preservation without compromising data quality [10].

Experimental Data from Comparative Studies

Recent investigations have directly compared the performance and outputs of these complementary technologies. A 2024 study by Huang et al. exemplified their synergistic application in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), where bulk RNA-seq identified differential expression patterns in response to asparaginase treatment, while scRNA-seq pinpointed the specific developmental states driving chemoresistance [1].

A 2025 methodological comparison focused on neutrophil transcriptomics evaluated three scRNA-seq platforms—10x Genomics Flex, PARSE Biosciences Evercode, and HIVE—for clinical biomarker studies [13]. All methods successfully captured neutrophil transcriptomes despite technical challenges posed by their low mRNA content and high RNase levels. The 10x Genomics Flex platform demonstrated particular utility for clinical settings due to its simplified sample collection protocol and strong concordance with flow cytometry data [13].

Table 2: Performance metrics of scRNA-seq methods in clinical neutrophil profiling

| Method | Cell Capture Efficiency | Protocol Complexity | Data Quality | Clinical Suitability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Flex | High | Simplified workflow | Strong concordance with flow cytometry | High - optimized for clinical collection [13] |

| PARSE Evercode | High | Moderate | High-quality transcriptomes | Moderate [13] |

| HIVE | Moderate | Complex | Captured neutrophil transcripts | Lower due to complexity [13] |

Integrated Analysis Approaches

Computational methods have emerged to leverage the strengths of both approaches through deconvolution algorithms that infer cell-type-specific information from bulk RNA-seq data using scRNA-seq references. EPIC-unmix, a novel empirical Bayesian method published in 2025, demonstrates superior performance in accurately estimating cell-type-specific expression profiles from bulk data [14]. This integration strategy proves particularly valuable for large cohort studies where scRNA-seq profiling of all samples remains cost-prohibitive.

In hepatocellular carcinoma research, scientists successfully combined scRNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq to identify liquid-liquid phase separation-related prognostic biomarkers [15]. The scRNA-seq data first identified malignant hepatocytes with high LLPS scores, revealing their strong interactions with other cells through EGFR-ERGF and MIF-CD44 signaling pathways. These findings were then validated through bulk RNA-seq analysis of larger cohorts, enabling development of a robust prognostic model [15].

Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

The successful implementation of scRNA-seq experiments requires specialized reagents and platforms designed to maintain cell viability, ensure efficient barcoding, and minimize technical variation.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and platforms for single-cell RNA sequencing

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chromium X Series (10x Genomics) | Microfluidic instrument for single-cell partitioning | Automates cell encapsulation into GEMs; critical for reproducible barcoding [1] |

| Gel Beads | Delivery of barcoded oligonucleotides | Contain cell-specific barcodes released upon dissolution in GEMs [1] |

| Viability Stains (e.g., DAPI, propidium iodide) | Assessment of cell viability prior to sequencing | Crucial for quality control as low viability drastically impacts data quality [1] |

| Enzymatic Dissociation Kits | Tissue dissociation into single-cell suspensions | Must be optimized for specific tissues to minimize stress responses [10] |

| Single Cell 3' Reagent Kits | Library preparation for 3' transcript counting | Cost-effective for cell typing and differential expression [1] |

| Single Cell 5' Reagent Kits | Library preparation for 5' transcript counting | Preserves V(D)J information for immune profiling [1] |

| cDNA Amplification Kits | Amplification of barcoded cDNA | Critical step due to minimal starting RNA in single cells [10] |

| Demonstrated Protocols (10x Genomics) | Optimized tissue-specific protocols | Provide validated methods for >40 tissue types [1] |

Analytical Frameworks and Computational Approaches

Bioinformatics Workflow for scRNA-seq Data

The analysis of scRNA-seq data presents distinct computational challenges compared to bulk RNA-seq, requiring specialized tools for quality control, normalization, and interpretation. The following diagram outlines a standard analytical workflow for single-cell data:

Machine Learning in scRNA-seq Analysis

Machine learning algorithms have become indispensable for extracting biological insights from high-dimensional scRNA-seq data. A 2025 bibliometric analysis identified random forests and deep learning models as particularly prominent in scRNA-seq research [16]. These methods enable key analytical tasks including:

- Clustering analysis utilizing hierarchical, graph-based, and model-based approaches to identify distinct cell types and states [16]

- Dimensionality reduction through Principal Component Analysis (PCA), t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE), and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) for visualization and downstream analysis [10] [16]

- Trajectory inference using algorithms like TIGON to reconstruct developmental pathways and cellular differentiation dynamics [16]

- Cell type annotation through combined deep learning and statistical approaches that significantly improve classification accuracy [16]

The integration of artificial intelligence with scRNA-seq data represents a growing frontier, with demonstrated applications in tumor microenvironment characterization, immunotherapy response prediction, and identification of novel cellular biomarkers [10] [16].

Clinical Applications and Translational Potential

The implementation of scRNA-seq in clinical investigations has yielded transformative insights into disease mechanisms across diverse medical specialties. In oncology, scRNA-seq has enabled the precise characterization of tumor heterogeneity, identification of therapy-resistant clones, and mapping of cancer stem cell populations [10] [11]. Beyond cancer, scRNA-seq applications have illuminated pathological mechanisms in respiratory diseases, metabolic disorders, cardiovascular conditions, autoimmune diseases, and neurodegenerative disorders [10].

A key translational application lies in biomarker discovery and drug development. The technology enables identification of novel therapeutic targets by resolving cell-type-specific responses to existing treatments and revealing previously unappreciated disease drivers [10]. For instance, in the hepatocellular carcinoma study mentioned previously, the integration of scRNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq facilitated the development of a prognostic model based on liquid-liquid phase separation-related genes, with potential implications for patient stratification and targeted therapy [15].

The emergence of spatial transcriptomics technologies further enhances the clinical utility of scRNA-seq by preserving spatial context, which is often critical for understanding tissue microarchitecture and cell-cell communication networks in pathological states [17]. As these technologies continue to mature and decrease in cost, their implementation in clinical trial design and personalized medicine approaches is expected to expand significantly.

Single-cell RNA sequencing has fundamentally expanded our analytical capabilities in transcriptomics, providing a powerful lens through which to examine cellular heterogeneity and dynamic biological processes. While bulk RNA-seq remains a valuable tool for population-level analyses, particularly in large cohort studies, scRNA-seq offers unparalleled resolution for deconstructing complex tissues and identifying rare cell populations. The most insightful approaches frequently integrate both methodologies, leveraging their complementary strengths to advance both basic biological understanding and clinical applications in the era of precision medicine.

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate RNA sequencing method is crucial for experimental success and data quality. Bulk RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq) and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) represent two fundamentally different approaches to transcriptome analysis, each with distinct technological profiles. Bulk RNA-seq measures the average gene expression across a population of heterogeneous cells, while scRNA-seq analyzes gene expression profiles of individual cells, enabling the resolution of cellular heterogeneity. Understanding their key differences in workflow, resolution, and input requirements is essential for designing robust studies and accurately interpreting results within biomedical research and therapeutic development.

At a Glance: Core Technological Differences

Table 1: High-level comparison of bulk versus single-cell RNA sequencing.

| Feature | Bulk RNA-Seq | Single-Cell RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population-average gene expression [1] [18] | Gene expression at individual cell level [1] [19] |

| Primary Input | Tissue piece or cell pellet (population of cells) [1] | Viable single-cell suspension [1] |

| Key Workflow Divergence | RNA extracted directly from lysed tissue/cells [1] | Cells partitioned into individual reactions before RNA capture [1] [20] |

| Typical Cost | Lower cost per sample [1] [21] | Higher cost per sample [1] [21] |

| Data Complexity | Lower; simpler analysis [1] | Higher; requires specialized computational tools [1] [22] |

| Ideal Application | Differential gene expression between conditions; biomarker discovery [1] [20] | Cellular heterogeneity; rare cell population discovery; developmental trajectories [1] [18] |

Workflow and Input Requirements: A Detailed Comparison

The experimental workflows for bulk and single-cell RNA-seq diverge significantly from the very first step, primarily due to their fundamental difference in resolution.

Bulk RNA-Seq Workflow

The bulk RNA-seq workflow is relatively straightforward. It begins with a piece of tissue or a pellet of cells, from which total RNA is directly extracted upon lysis. This RNA, representing the averaged transcriptome of thousands to millions of cells, is then converted to cDNA and processed into a sequencing library [1]. This workflow does not require special steps to maintain cell integrity during initial processing, as the immediate goal is nucleic acid extraction.

Single-Cell RNA-Seq Workflow

In contrast, the scRNA-seq workflow is more complex and technically demanding. The critical first step is the preparation of a viable single-cell suspension from the starting tissue through enzymatic or mechanical dissociation. This requires careful optimization to ensure high cell viability and to prevent the formation of cell clumps or debris, which can clog microfluidic chips [1] [22]. A crucial and distinct stage that follows is instrument-enabled cell partitioning.

Platforms like the 10x Genomics Chromium system isolate individual cells into tiny oil-encapsulated droplets called GEMs (Gel Beads-in-emulsion). Within each GEM, a unique cell-specific barcode labels all RNA molecules from that single cell, allowing bioinformatic tracing back to each cell of origin after sequencing [1] [20]. This barcoding step is what enables the high-resolution, multi-cell data output.

Experimental Resolution and Data Output

The difference in workflow directly dictates the fundamental difference in resolution and data output between the two methods.

Bulk RNA-Seq: The Population Average - Bulk RNA-seq provides a readout of the gene expression profile for the entire sample, with many different cells pooled together. The resulting data represents the average expression levels for individual genes across all cells in the sample. This can mask the cellular origins of gene expression signals, particularly in heterogeneous tissues, and obscure rare but biologically critical cell populations [1] [20].

Single-Cell RNA-Seq: The Cellular Census - scRNA-seq provides a whole transcriptome gene expression profile for each individual cell in a sample. This allows researchers to identify and characterize distinct cell types and cell states, quantify their proportions, and reveal gene expression differences between similar cell subpopulations. It is uniquely powerful for uncovering rare cell types or transient states that play key roles in development, disease, or treatment resistance [1] [20] [19].

Table 2: Key differences in data output and analytical capabilities.

| Analytical Aspect | Bulk RNA-Seq | Single-Cell RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Heterogeneity Analysis | Masks cellular heterogeneity [1] | Reveals cellular heterogeneity and rare cell types [1] [20] |

| Primary Output | Average gene expression for the sample [1] | Gene expression matrix per cell [1] |

| Key Strengths | Differential expression between conditions; biomarker discovery; splicing analysis [1] [18] | Cell type identification; developmental trajectory inference; cell-state transitions [1] [18] |

| Data Sparsity | Dense data matrix | Sparse data matrix with "dropout" events [22] |

Case Studies in Integrated Experimental Design

Modern research often leverages both technologies in a complementary manner. The following case studies illustrate how their distinct resolutions and workflows are applied in practice.

Case Study 1: Investigating Tumor Microenvironment in Retinoblastoma

Objective: To explore tumor microenvironment (TME) heterogeneity and identify key genes associated with invasion in Retinoblastoma (RB) [23].

Experimental Protocols and Data Integration:

- scRNA-seq Analysis: Publicly available scRNA-seq data from 10 RB patient tumor tissues was analyzed. The analysis involved:

- Clustering and Annotation: Using the Seurat R package to cluster cells and identify distinct subpopulations.

- Sub-clustering: Focusing on cone precursor (CP) cells to reveal finer malignant subpopulations.

- CNV Inference: Using the InferCNV package to distinguish malignant from normal cells based on copy number variations.

- Cell-Cell Communication: Applying CellPhoneDB to analyze rewired ligand-receptor interactions between invasive and non-invasive tumors [23].

- Bulk RNA-seq Analysis: Independent bulk RNA-seq data was used to:

- Identify Molecular Subtypes: Unsupervised consensus clustering revealed two molecular subtypes with distinct TME characteristics.

- Validate Key Gene: Analysis identified DOK7 as a key gene associated with invasion [23].

- Functional Validation: In vitro experiments with Y79 cell lines, including DOK7 knockdown via siRNA and functional assays (qPCR, CCK-8, Transwell), confirmed its role in promoting tumor progression [23].

Conclusion: The single-cell data resolved the cellular heterogeneity of the TME and pinpointed specific malignant subpopulations and communication networks, while the bulk data provided a broader view for subtype classification and biomarker identification, subsequently validated functionally.

Case Study 2: Uncovering Macrophage Heterogeneity in Rheumatoid Arthritis

Objective: To elucidate the heterogeneity of macrophages and their role in the progression of Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) [24].

Experimental Protocols and Data Integration:

- Integrated Sequencing Analysis: Researchers integrated public scRNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq datasets from RA and control synovial tissues.

- scRNA-seq Workflow:

- Data Integration and Clustering: The Seurat workflow and Harmony algorithm were used to batch-correct and cluster 26,923 cells.

- Myeloid Sub-clustering: Myeloid cells were extracted and re-clustered, revealing a Stat1+ macrophage subset elevated in RA.

- Pathway Enrichment: Stat1+ macrophages were found to be enriched in inflammatory pathways [24].

- Bulk Data Correlation and Validation: Bulk RNA-seq analysis and an Adjuvant-Induced Arthritis (AIA) rat model confirmed the upregulated expression of STAT1 in RA.

- Functional Investigation: In vitro experiments showed that STAT1 activation upregulated LC3 and ACSL4 while downregulating p62 and GPX4, suggesting STAT1 modulates autophagy and ferroptosis pathways—effects reversed by fludarabine treatment [24].

Conclusion: The study used scRNA-seq to discover a novel, pathogenic macrophage subset within the complex RA synovium, which was then contextualized and validated using bulk data and animal models, revealing a potential new therapeutic target.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of RNA sequencing experiments, particularly scRNA-seq, relies on specific reagents and platforms.

Table 3: Key research reagents and solutions for RNA sequencing workflows.

| Item | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Viable Single-Cell Suspension | Starting material where individual, live cells are dissociated from tissue. | Critical for scRNA-seq; requires optimization of dissociation protocol [1] [22]. |

| Partitioning Instrument & Chips | Microfluidic devices (e.g., 10X Chromium Controller) to isolate single cells into droplets. | Essential for high-throughput scRNA-seq platforms [1] [20]. |

| Barcoded Gel Beads | Beads containing cell barcodes and UMIs to label all RNA from a single cell. | Used in droplet-based scRNA-seq (e.g., 10X Genomics) for multiplexing [20]. |

| Cell Lysis Buffer | Reagent to break open cells and release RNA while preserving RNA integrity. | Used in both bulk and scRNA-seq; in scRNA-seq, lysis occurs after partitioning [1]. |

| mRNA Capture Oligos (dT) | Oligonucleotides with poly(dT) stretches to selectively bind polyadenylated mRNA. | Used in both protocols to enrich for mRNA and deplete rRNA [22]. |

| Library Preparation Kit | Reagents for cDNA synthesis, amplification, and addition of sequencing adapters. | Required for both bulk and scRNA-seq to make NGS-compatible libraries [1]. |

Bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing are not mutually exclusive technologies but rather complementary tools in the modern researcher's arsenal. Bulk RNA-seq remains a powerful, cost-effective method for analyzing gene expression across large sample sizes and identifying broad transcriptional changes. In contrast, single-cell RNA-seq provides an unparalleled view into cellular heterogeneity, enabling the discovery of novel cell types, states, and dynamic processes. The choice between them—or the decision to integrate both—is fundamentally guided by the research question, driven by the critical trade-offs between resolution, cost, workflow complexity, and analytical depth.

In transcriptomics research, choosing between bulk RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq) and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) represents a critical decision point that directly impacts experimental outcomes, data complexity, and resource allocation. Bulk RNA-seq analyzes RNA from a population of cells, providing an averaged gene expression profile for the entire sample. In contrast, scRNA-seq isolates individual cells before sequencing, enabling the investigation of gene expression variations within heterogeneous populations [3]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these technologies' cost structures, throughput capabilities, and experimental requirements to help researchers and drug development professionals make informed decisions aligned with their scientific goals and budgetary constraints.

Direct Cost and Throughput Comparison

The financial and practical implications of choosing between bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing are substantial, with each method offering distinct advantages for different experimental scales.

Table 1: Direct Cost and Throughput Comparison

| Feature | Bulk RNA Sequencing | Single-Cell RNA Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Cost per Sample | ~$300 [3] | $500-$2,000 [3] |

| Relative Cost | Lower (~1/10th of scRNA-seq) [3] | Higher (Up to 10x bulk cost) [3] [1] |

| Cell Throughput | Population-level (thousands to millions of cells) [9] | Individual cell level (hundreds to tens of thousands of cells) [3] [25] |

| Sequencing Depth | Varies by experiment [25] | 30,000-150,000 reads/cell [25] |

| Reagent Cost Factor | Baseline | 10-20x higher than bulk [25] |

| Sequencing Cost Factor | Baseline | 10-20x higher than bulk [25] |

| Ideal Use Case | Large cohort studies, homogeneous samples [3] [1] | Heterogeneous tissues, rare cell detection [3] [1] |

The cost differential stems from several technical factors. Single-cell RNA sequencing requires specialized reagents for cell partitioning and barcoding, with reagent costs typically running 10-20 times higher than bulk RNA sequencing experiments [25]. Furthermore, scRNA-seq requires substantially greater sequencing depth to achieve statistically significant data from individual cells, further increasing overall expenses [25]. However, despite higher per-sample costs, scRNA-seq provides unparalleled resolution for detecting cellular heterogeneity that bulk methods cannot achieve [1].

Experimental Design and Methodologies

The experimental workflows for bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing diverge significantly from the initial sample preparation stage, each presenting distinct technical considerations and challenges.

Bulk RNA Sequencing Workflow

Bulk RNA sequencing begins with RNA extraction directly from a tissue sample or cell culture, capturing the transcriptome from the entire cell population simultaneously [3] [1].

Key Steps in Bulk RNA-seq Protocol:

- Total RNA Extraction: RNA is isolated from the entire tissue or cell population sample [1].

- Library Preparation: Extracted RNA is converted to complementary DNA (cDNA), followed by adapter ligation and amplification to create a sequencing-ready library [1].

- Sequencing: Libraries are sequenced using next-generation sequencing platforms [3].

- Data Analysis: Population-averaged gene expression profiles are generated and analyzed for differential expression [3] [2].

Bulk sequencing provides a composite gene expression profile representing the average of all cells in the sample. This approach works exceptionally well for homogeneous cell populations or when studying overall tissue responses [3].

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Workflow

Single-cell RNA sequencing introduces additional complexity to isolate and barcode individual cells before sequencing, enabling cell-specific transcriptome analysis [3] [20].

Key Steps in scRNA-seq Protocol:

- Single-Cell Suspension: Tissues are dissociated into viable single-cell suspensions through enzymatic or mechanical digestion [1].

- Cell Partitioning: Individual cells are isolated into micro-reaction vessels (e.g., GEMs - Gel Beads-in-emulsion) using microfluidic systems [1] [20].

- Cell Barcoding: Each cell's RNA is labeled with cell-specific barcodes during reverse transcription, allowing bioinformatic tracing back to individual cells after sequencing [1] [20] [25].

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Barcoded products are pooled for library preparation and sequenced [1].

- Data Analysis: Specialized computational methods process the data to account for increased noise and sparsity, enabling cell-type identification and heterogeneity analysis [3] [2].

Application-Based Selection Guide

The choice between bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing should be primarily driven by the research question, sample characteristics, and analytical requirements.

Table 2: Application-Based Technology Selection

| Research Goal | Recommended Technology | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Gene Expression | Bulk RNA-seq [1] | Cost-effective for comparing expression between conditions (e.g., disease vs. healthy) |

| Biomarker Discovery | Bulk RNA-seq [3] [1] | Efficient for identifying population-level expression signatures |

| Gene Fusion Detection | Bulk RNA-seq [20] | More comprehensive for identifying novel transcripts and splicing variants |

| Cellular Heterogeneity | Single-Cell RNA-seq [3] [1] | Uniquely identifies distinct cell types and states within complex tissues |

| Rare Cell Population Detection | Single-Cell RNA-seq [3] | Detects cell types occurring at frequencies as low as 1 in 10,000 cells |

| Developmental Trajectories | Single-Cell RNA-seq [1] | Reconstructs cellular differentiation pathways and lineage relationships |

| Tumor Microenvironment | Single-Cell RNA-seq [23] [26] | Dissects complex interactions between cancer, immune, and stromal cells |

| Immune Cell Profiling | Single-Cell RNA-seq [3] [1] | Discovers new immune cell subsets and their functional states |

The decision framework extends beyond applications to sample characteristics. Bulk RNA sequencing is particularly suitable for homogeneous samples or when studying collective biological responses [3]. Its cost structure makes it ideal for large-scale studies requiring numerous samples, such as clinical cohort analyses or biobank projects [1]. In contrast, single-cell RNA sequencing is indispensable for heterogeneous tissues like tumors, where understanding cellular diversity is crucial [3] [26]. The technology has been instrumental in identifying previously unknown cell types and transient states that were indistinguishable in bulk sequencing data [3].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful RNA sequencing experiments require careful selection of reagents and materials tailored to each technology's specific requirements.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function | Technology |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Suspension Solutions | Dissociate tissues into viable single cells while preserving RNA integrity [1] | scRNA-seq |

| Cell Barcoding Beads | Gel beads with cell-specific barcodes for labeling individual cell transcriptomes [1] [20] | scRNA-seq |

| Microfluidic Chips | Partition individual cells into nanoliter-scale reactions for processing [1] [20] | scRNA-seq |

| mRNA Capture Oligos | Oligo-dT conjugated primers for mRNA enrichment during reverse transcription [20] | Both |

| UMI Reagents | Unique Molecular Identifiers to label and quantify unique mRNA transcripts [20] | Both |

| Library Prep Kits | Prepare sequencing libraries with appropriate adapters for platform compatibility [1] | Both |

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality total RNA from tissues or cell populations [1] | Bulk RNA-seq |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Remove ribosomal RNA to enrich for coding and non-coding transcripts of interest [20] | Both |

The single-cell RNA sequencing workflow places particular emphasis on cell viability and sample quality. The initial generation of a high-quality single-cell suspension is critical, as clumps or excessive debris can compromise microfluidic partitioning and barcoding efficiency [1]. For bulk RNA sequencing, the focus shifts to RNA quality and quantity, with sufficient input material being essential for robust library preparation [3]. Recent technological advancements have led to the development of targeted scRNA-seq approaches that focus sequencing resources on predefined gene sets, providing superior sensitivity for specific pathways while reducing costs compared to whole transcriptome methods [27].

Data Analysis and Computational Considerations

The computational requirements and analytical approaches differ substantially between bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing data, impacting both infrastructure needs and expertise requirements.

Bulk RNA sequencing data analysis follows a relatively standardized pipeline including quality control, read alignment, expression quantification, and differential expression analysis [2]. The data complexity is lower because it represents an average gene expression across the entire cell population [3]. Tools like FastQC for quality control, STAR for read alignment, and featureCounts for expression quantification are commonly employed [2]. Differential expression analysis can be performed with established statistical methods, making bulk RNA-seq more accessible to labs with limited bioinformatics support [2].

Single-cell RNA sequencing generates substantially more complex data structures requiring specialized computational methods [3] [2]. The analysis pipeline must account for technical artifacts like batch effects, data sparsity from dropout events where expressed genes fail to be detected, and the high dimensionality of measuring thousands of genes across thousands of individual cells [3] [2]. Analysis typically involves specialized tools for cell clustering (e.g., Seurat), trajectory inference (e.g., Monocle), and cell-cell communication prediction (e.g., CellPhoneDB) [23] [26]. These analyses require substantial computational resources and bioinformatics expertise, representing a significant consideration when choosing scRNA-seq [3].

Bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing technologies offer complementary strengths for transcriptomic research. Bulk RNA-seq provides a cost-effective solution for population-level studies, differential expression analysis, and large cohort projects where cellular heterogeneity is not the primary focus. Single-cell RNA-seq, despite its higher per-sample cost, delivers unparalleled resolution for dissecting cellular heterogeneity, identifying rare cell populations, and mapping developmental trajectories. The optimal choice depends on aligning technological capabilities with specific research questions, sample characteristics, and available resources. As both technologies continue to evolve, we are seeing promising trends toward cost reduction in scRNA-seq and the development of integrated approaches that combine both methods to provide comprehensive biological insights [3] [1].

Choosing Your Tool: Methodological Insights and Application-Specific Use Cases

In the evolving landscape of transcriptomics, researchers must strategically select the appropriate sequencing method to address their specific biological questions. While single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has emerged as a powerful tool for resolving cellular heterogeneity, bulk RNA sequencing remains an indispensable workhorse for numerous applications in biomedical research. This method, which analyzes the average gene expression from a population of cells, provides a robust, cost-effective, and statistically powerful approach for answering fundamental questions about transcriptional states across biological conditions [1] [18]. This guide objectively examines the ideal applications for bulk RNA-seq, focusing on its core strengths in differential expression analysis, biomarker discovery, and isoform analysis, while providing a clear comparison with single-cell approaches to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Bulk RNA-Seq Workflow and Key Reagents

A standard bulk RNA-seq experiment involves a defined sequence of steps, each requiring specific reagent solutions and tools. The table below outlines the essential components of a typical workflow.

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials for Bulk RNA-Seq

| Workflow Stage | Essential Reagents & Tools | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Library Preparation | Poly-dT Oligos, rRNA Depletion Kits, Reverse Transcriptase, Fragmentation Enzymes | mRNA enrichment, cDNA synthesis, and library construction [2] [20] |

| Sequencing | Illumina Flow Cell, Sequencing By Synthesis (SBS) Reagents | High-throughput parallel sequencing of cDNA libraries [28] |

| Read Alignment | STAR, HISAT2, BWA | Maps sequenced reads to a reference genome/transcriptome [29] [2] |

| Quantification | featureCounts, HTSeq, Salmon, Kallisto | Assigns reads to genes/transcripts and generates count data [29] [2] |

| Differential Expression | DESeq2, edgeR, limma | Identifies statistically significant gene expression changes between conditions [29] |

The logical flow from sample to data, incorporating these key stages, can be visualized as follows:

Core Applications and Experimental Protocols

Differential Gene Expression Analysis

Differential expression (DE) analysis is a cornerstone application of bulk RNA-seq, used to identify genes with statistically significant expression changes between conditions (e.g., diseased vs. healthy, treated vs. control) [1] [18].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Experimental Design and Power Analysis: A critical first step is to determine the appropriate number of biological replicates. At least six replicates per condition are recommended for robust detection of differentially expressed genes, though financial constraints often lead to smaller cohort sizes, which can impact replicability [30].

- RNA Extraction and Library Preparation: Total RNA is extracted from the tissue or cell population of interest. Libraries are typically prepared via poly-A enrichment of mRNA or ribosomal RNA depletion, followed by cDNA synthesis and adapter ligation [1] [2].

- Sequencing and Primary Analysis: Libraries are sequenced on a platform like Illumina to an appropriate depth (often 20-40 million reads per sample). The raw sequencing data (FASTQ) undergoes quality control (using tools like FastQC) and trimming (with tools like Trimmomatic) to remove low-quality bases and adapters [29] [2].

- Alignment and Quantification: Processed reads are aligned to a reference genome using a splice-aware aligner like STAR or HISAT2 [29] [2]. The aligned reads are then assigned to genomic features (genes) using quantification tools like featureCounts or HTSeq to generate a count matrix [2].

- Statistical Analysis: The count matrix is imported into statistical software packages like DESeq2 or edgeR. These tools normalize the data to account for differences in library size and RNA composition, and then apply statistical models (e.g., negative binomial distribution) to test for differential expression [29].

Performance Data: The following table summarizes key performance characteristics of bulk RNA-seq for differential expression, informed by large-scale replicability studies [30].

Table 2: Performance of Bulk RNA-Seq in Differential Expression Analysis

| Metric | Performance in Bulk RNA-Seq | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Power | High with sufficient replicates (>6); low with common underpowered designs (n=3) [30] | Number of biological replicates, effect size (fold change), sequencing depth [30] |

| Replicability | Highly variable; improves dramatically with cohort size [30] | Cohort size and population heterogeneity; low replicability does not always imply low precision [30] |

| Recommended Replicates | 6-12 per condition for robust detection [30] | Budget, desired sensitivity, and expected effect sizes [30] |

| Advantage vs. scRNA-seq | More cost-effective for large cohort studies, provides population-level summary with straightforward analysis [1] | Lower per-sample cost and simpler data analysis pipeline [1] [31] |

Biomarker Discovery

Bulk RNA-seq is widely used to discover RNA-based biomarkers for disease diagnosis, prognosis, or patient stratification [1]. It provides a holistic view of the molecular signature of a tissue.

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Cohort Selection: Define and recruit a well-characterized cohort, typically including cases (e.g., cancer patients) and controls (e.g., healthy tissue). Large sample sizes are crucial for robust biomarker identification.

- Sample Processing and Sequencing: Process all samples uniformly to minimize batch effects. RNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing are performed as described in the DE protocol.

- Data Processing and Differential Expression: Perform standard alignment, quantification, and DE analysis to identify a longlist of candidate genes associated with the condition of interest.

- Feature Selection and Model Building: Use machine learning algorithms (e.g., LASSO regression, random forests) on the training cohort to refine the longlist into a concise gene signature that predicts the clinical outcome [32]. This signature is the candidate biomarker.

- Independent Validation: The performance of the biomarker signature must be validated in one or more independent, unseen patient cohorts to assess its generalizability and clinical utility [32].

Case Study Example: In a study on Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSC), researchers first used scRNA-seq to identify B cell marker genes. They then leveraged bulk RNA-seq data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) to develop and validate a prognostic model based on these markers, demonstrating the power of bulk data for building and testing biomarkers across large cohorts [32].

Transcriptome Annotation and Isoform Analysis

Beyond gene-level expression, bulk RNA-seq is powerful for characterizing the transcriptome's full complexity, including novel transcripts, isoform usage, and alternative splicing [1] [18].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: For isoform analysis, rRNA-depleted libraries and paired-end sequencing are preferred over mRNA-enriched libraries. This approach captures non-coding RNAs and provides reads long enough to span splice junctions [20].

- Transcriptome Reconstruction: Processed reads are assembled into transcripts using reference-guided assemblers like StringTie or Cufflinks [2]. Alternatively, reference-independent assemblers like Trinity can be used to discover novel transcripts [2].

- Isoform Quantification and Analysis: Tools like Cufflinks, StringTie, or Salmon can estimate the relative abundance of different isoforms [29] [2]. Differential isoform usage and splicing are then analyzed with tools like

Cuffdiff2orrMATS. - Fusion Gene Detection: Specialized computational algorithms (e.g.,

DEEPEST) are used to scan the aligned data for chimeric reads that indicate gene fusion events, which are important drivers in cancer [20].

Performance Data:

Table 3: Performance of Bulk RNA-Seq in Transcriptome Characterization

| Application | Bulk RNA-Seq Utility | Tools & Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| Novel Transcript Discovery | High utility for annotating isoforms and non-coding RNAs [1] | StringTie, Cufflinks, Trinity [2] |

| Alternative Splicing Analysis | Effectively studies splicing events and their regulation [18] | Cufflinks, rMATS, DEXSeq |

| Fusion Gene Identification | High discovery potential; requires careful false-positive control [20] | DEEPEST, STAR-Fusion [20] |

| Advantage vs. scRNA-seq | Higher sequencing depth per sample often allows for more confident isoform identification [28] | Deeper sequencing and more mature analytical pipelines for splicing analysis [28] |

The pathway to discovering various transcriptomic features involves a specialized analysis workflow, as shown below.

Bulk RNA-seq and scRNA-seq are not competing technologies but are complementary tools that answer different biological questions [31]. The choice between them should be guided by the research goal.

- Choose Bulk RNA-Seq when the objective is to understand the average global gene expression of a tissue or population, to conduct differential expression analysis on large cohorts for biomarker discovery, to perform splicing or isoform analysis with high depth, or when working within budget constraints that preclude single-cell analysis [1] [18] [31].

- Choose Single-Cell RNA-Seq when the research aims to dissect cellular heterogeneity, discover rare cell types or states, or reconstruct developmental trajectories [1] [20].

For a comprehensive research strategy, these methods can be powerfully integrated. One can use bulk RNA-seq to identify global expression changes in a large cohort and then employ scRNA-seq to pinpoint the specific cell types driving those changes, leveraging the strengths of both approaches for a complete understanding of complex biological systems [31] [32].

The fundamental difference between bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing lies in their resolution. Bulk RNA-seq provides a population-averaged gene expression profile, analogous to viewing a forest from a distance, while single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) reveals the transcriptome of individual cells, akin to examining every single tree [1] [19]. This resolution revolution has transformed our ability to dissect cellular heterogeneity, identify rare cell populations, and reconstruct developmental trajectories—biological features that are completely obscured in bulk analysis [33] [20].

The technological advancement of scRNA-seq has enabled researchers to move beyond the limitations of bulk sequencing, where true cell-to-cell variability is masked by averaging effects [33] [19]. In any tissue or organ, the cell population is inherently heterogeneous, and this variability has profound biological implications that can only be deciphered using scRNA-seq [33]. This capability is particularly crucial for understanding complex biological processes such as development, disease progression, and treatment response, where distinct cellular subpopulations often play decisive roles [1] [34].

Fundamental Technical Comparisons: Bulk vs. Single-Cell RNA-Seq

Experimental Workflows and Key Differences

The experimental workflows for bulk and single-cell RNA-seq differ significantly in their initial stages but converge during library preparation and sequencing phases. The most critical distinction lies in sample preparation: bulk RNA-seq begins with lysing the entire tissue or cell population to extract RNA, while scRNA-seq requires the creation of viable single-cell suspensions before any RNA processing can occur [1] [20].

For scRNA-seq, the 10x Genomics Chromium system exemplifies a widely adopted approach. Its core technology involves partitioning single cells into Gel Beads-in-emulsion (GEMs) within a microfluidic chip. Each GEM contains a single cell, reverse transcription reagents, and a gel bead conjugated with oligonucleotides featuring cell-specific barcodes and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) [1] [20]. These barcodes enable the tracing of all transcripts back to their cell of origin, while UMIs facilitate accurate quantification by distinguishing biological duplicates from technical amplification artifacts [20].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing approaches:

Technical Specifications and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of technical specifications between bulk and single-cell RNA-seq

| Parameter | Bulk RNA-Seq | Single-Cell RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population average | Single-cell level |

| Cells Analyzed | Thousands to millions pooled | Hundreds to millions individually barcoded |

| Detection Sensitivity | Higher for abundant transcripts | Variable; lower for lowly expressed genes due to dropout effects |

| Ability to Detect Heterogeneity | No, masks cellular diversity | Yes, reveals cellular heterogeneity |

| Rare Cell Type Detection | Limited to none | Excellent (can identify populations <1% of total) |

| Required Input Material | Total RNA from tissue/cell population | Viable single-cell suspension |

| Key Technical Challenges | Deconvolution of mixed signals, sampling bias | Sample dissociation, cell viability, technical noise, data sparsity |

| Cost Per Sample | Lower | Higher, but decreasing with new technologies |

| Data Complexity | Moderate, established analysis pipelines | High, requires specialized computational methods |

| Primary Applications | Differential expression between conditions, biomarker discovery, pathway analysis | Cell type identification, developmental trajectories, tumor heterogeneity, immune cell profiling |

| Spatial Context | Lost during RNA extraction | Lost during tissue dissociation (addressed by spatial transcriptomics) |

The data presented in Table 1 highlights fundamental trade-offs between these technologies. While bulk RNA-seq offers greater sensitivity for transcript detection and lower per-sample costs, scRNA-seq provides unparalleled resolution for cellular heterogeneity analysis [1] [33]. The choice between these approaches depends heavily on research objectives, with scRNA-seq being essential for questions involving cellular diversity, rare cell populations, and dynamic biological processes [20].

Resolving Cellular Heterogeneity: The Core Advantage of scRNA-Seq

Defining Cellular Heterogeneity in Health and Disease

Cellular heterogeneity is an inherent property of all biological systems, where genetically identical cells exhibit phenotypic and functional variations that facilitate adaptability to dynamic environmental conditions [33]. scRNA-seq enables researchers to characterize this heterogeneity in unprecedented detail, moving beyond traditional cell-type classifications based on limited marker genes to comprehensive transcriptomic profiling [35].

In oncology, scRNA-seq has revealed remarkable heterogeneity within tumors that was previously obscured by bulk sequencing. For example, in glioblastoma, colorectal cancer, and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, scRNA-seq has identified distinct cellular subpopulations with different functional states, drug resistance properties, and metastatic potential [20]. Similarly, in rheumatoid arthritis, integrated analysis of scRNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq data has revealed heterogeneous macrophage subpopulations, with STAT1+ macrophages specifically enriched in inflammatory pathways and contributing to disease pathogenesis [24].

Analytical Approaches for Heterogeneity Analysis

The analysis of scRNA-seq data involves several specialized computational approaches that enable researchers to extract biological insights from complex single-cell datasets:

- Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering: Techniques such as PCA, UMAP, and t-SNE transform high-dimensional gene expression data into two or three dimensions for visualization, while clustering algorithms identify distinct cell groups based on transcriptomic similarity [24].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Identification of genes that are significantly enriched in specific cell clusters compared to others, enabling the definition of marker genes for cell types and states [35].

- Gene Regulatory Network Inference: Reconstruction of regulatory relationships between genes to understand the transcriptional programs governing cellular identity [35].

- Trajectory Analysis and Pseudotime Ordering: Computational methods that order cells along a continuum of biological processes, such as differentiation or activation, to reconstruct dynamic transitions [24].

Identifying Rare Cell Types and States

Technical Requirements for Rare Cell Detection

The detection of rare cell types presents particular technical challenges that require specific experimental designs. Successful identification of rare populations depends on several factors:

- Cell Throughput: Capturing sufficient numbers of cells to ensure rare populations are represented in the dataset. Modern high-throughput platforms like the 10x Genomics Chromium and Parse Biosciences' Evercode combinatorial barcoding can profile thousands to millions of cells in a single experiment [1] [36].

- Sequencing Depth: Adequate sequencing coverage to detect low-abundance transcripts that may characterize rare populations.

- Minimized Technical Bias: Protocols that maintain representative sampling across all cell types without introducing amplification biases.

The importance of sufficient cell throughput is demonstrated by a recent large-scale perturbation study that analyzed 10 million cells across 1,092 samples. When the researchers downsampled their data, they found that cytokine effects were barely detectable in small subsets (e.g., 78 CD16+ monocytes), but became statistically robust when analyzing larger cell numbers (2,500 cells) [36].

Biological Applications of Rare Cell Discovery

The ability to identify rare cell populations has led to significant biological insights across multiple fields:

- Cancer Research: scRNA-seq has identified rare stem-like cells with treatment-resistance properties in melanoma and breast cancer. In melanoma, a minor cell population expressing high levels of AXL was found to develop resistance after treatment with RAF or MEK inhibitors [20]. Similarly, drug-tolerant-specific RNA variants were identified in breast cancer cell lines that were absent in control cell lines [20].

- Immunology: Rare immune cell subsets with specialized functions have been characterized, such as a small subset of CD8+ T cells associated with favorable response to adaptive cell transfer immunotherapy in melanoma patients [20].

- Developmental Biology: Identification of rare progenitor and intermediate cell states during embryonic development and tissue formation [33] [19].

Reconstructing Developmental Lineages and Trajectories

Pseudotime Analysis and Trajectory Inference

A powerful application of scRNA-seq is the reconstruction of developmental lineages and cellular differentiation trajectories through computational methods that order cells along pseudotime—an abstract measure of developmental progression [35] [24]. Unlike bulk time-course experiments that require sacrificing animals or tissue samples at multiple timepoints, pseudotime analysis leverages the asynchrony of cellular processes within a population to reconstruct continuous biological transitions from a single snapshot [35].

The Monocle package and similar tools perform this analysis by identifying genes that vary across pseudotime, then grouping these genes into modules with similar expression patterns, and finally linking these patterns to biological processes through enrichment analysis [24]. For example, in a study of myeloid cells, pseudotime analysis revealed dynamic changes in gene expression along differentiation trajectories, with distinct gene modules associated with different activation states [24].

Applications in Development and Disease

Lineage reconstruction using scRNA-seq has provided fundamental insights into developmental biology and disease mechanisms:

- Cardiac Development: scRNA-seq of mouse cardiac progenitor cells from E7.5 to E9.5 identified eight distinct cardiac subpopulations and revealed transcriptional and epigenetic regulations during cardiac progenitor cell fate decisions [33].

- Hematopoiesis: Boolean network models applied to scRNA-seq data have successfully predicted curated models of blood cell development, identifying key regulators that drive cellular state transitions [35].

- Tumor Evolution: scRNA-seq enables reconstruction of phylogenetic relationships between tumor subclones, revealing patterns of cancer evolution and metastasis [34] [20].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for trajectory inference from scRNA-seq data:

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

Enhancing Target Identification and Validation

The pharmaceutical industry has increasingly adopted scRNA-seq to improve the efficiency and success rate of drug development [34] [37]. A key application is in target identification and validation, where scRNA-seq provides precise cell-type-specific expression data that helps prioritize targets with better clinical trial success potential [36].

A retrospective analysis conducted by the Wellcome Institute in Cambridge demonstrated that drug targets with cell-type-specific expression in disease-relevant tissues were more likely to progress successfully from Phase I to Phase II clinical trials [36]. This predictive power can streamline the drug development pipeline by focusing resources on the most promising targets, potentially reducing the high attrition rates that plague pharmaceutical R&D [34].

Functional Genomics and Mechanism of Action Studies

scRNA-seq has become an invaluable tool for functional genomics, particularly when combined with CRISPR screening approaches. This combination enables large-scale mapping of how regulatory elements and transcription start sites impact gene expression in individual cells [36]. For example, one study profiled approximately 250,000 primary CD4+ T cells, enabling systematic mapping of regulatory element-to-gene interactions and functional interrogation of non-coding regulatory elements at single-cell resolution [36].

In drug screening, scRNA-seq provides detailed cell-type-specific gene expression profiles that go beyond traditional readouts like cell viability. This enables comprehensive insights into cellular responses, pathway dynamics, and potential therapeutic targets, helping researchers identify subtle changes in gene expression and cellular heterogeneity that underlie drug efficacy and resistance mechanisms [36].

Table 2: Applications of scRNA-seq in the drug development pipeline

| Development Stage | Application of scRNA-Seq | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Target Identification | Cell-type-specific expression analysis in disease-relevant tissues | Identifies targets with higher clinical success probability |

| Target Validation | CRISPR perturbation screening with scRNA-seq readout | Maps regulatory networks and gene functions |

| Preclinical Testing | Characterization of disease models (organoids, animal models) | Ensures model relevance and identifies appropriate biomarkers |

| Biomarker Discovery | Identification of cell-type-specific markers and signatures | Enables patient stratification and treatment response prediction |

| Clinical Trials | Analysis of patient samples pre- and post-treatment | Reveals mechanisms of response/resistance and pharmacodynamics |

| Toxicology Studies | Assessment of cell-type-specific toxicities | Identifies potential adverse effects in relevant cell types |

Experimental Design and Methodological Considerations

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful scRNA-seq experiments require careful selection of reagents and platforms tailored to specific research questions. The following table outlines essential components and their functions:

Table 3: Essential research reagents and platforms for scRNA-seq experiments

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Partitioning System | Isolates individual cells into reaction vessels | 10x Genomics Chromium, Parse Biosciences Evercode |

| Barcoded Gel Beads | Deliver cell barcodes and UMIs to individual cells | 10x Barcoded Gel Beads, Parse Evercode Barcodes |

| Reverse Transcription Mixes | Convert RNA to cDNA with incorporation of barcodes | Custom enzyme mixes with template switching capability |

| Cell Lysis Reagents | Release RNA while maintaining barcode integrity | Detergent-based lysis buffers |

| cDNA Amplification Kits | Amplify limited starting material for library construction | PCR-based amplification with minimal bias |

| Library Preparation Kits | Prepare sequencing libraries from amplified cDNA | Illumina-compatible library prep reagents |

| Viability Stains | Assess cell integrity before processing | Propidium iodide, DAPI, fluorescent viability dyes |

| Cell Surface Antibodies | Enable protein detection alongside transcriptome | CITE-seq antibodies, TotalSeq reagents |

| Nuclease Inhibitors | Prevent RNA degradation during processing | RNase inhibitors, proteinase K |

| Quality Control Assays | Assess RNA and library quality before sequencing | Bioanalyzer, TapeStation, qPCR assays |

Single-Cell RNA-Seq Protocol

A standardized protocol for droplet-based scRNA-seq, such as the 10x Genomics Chromium system, involves these critical steps:

Sample Preparation and Single-Cell Suspension:

- Tissue dissociation using enzymatic (collagenase, trypsin) or mechanical methods appropriate for the tissue type [1]

- Filtration through 30-40μm filters to remove cell clumps and debris

- Cell counting and viability assessment using hemocytometer or automated cell counters

- Adjustment to optimal concentration (700-1,200 cells/μL) for targeted cell recovery [1]

Single-Cell Partitioning and Barcoding:

- Loading cells, barcoded gel beads, and partitioning oil into microfluidic chip

- Generation of Gel Beads-in-emulsion (GEMs) where ideally each GEM contains a single cell, a single gel bead, and reverse transcription reagents [1] [20]

- Dissolution of gel beads releasing oligonucleotides containing:

- Poly(dT) primers for mRNA capture

- Cell-specific barcode (same for all oligonucleotides on a single bead)

- Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) for each oligonucleotide molecule

- PCR adaptor sequences [20]

Reverse Transcription and cDNA Amplification:

- Cell lysis within GEMs releasing RNA

- Reverse transcription to produce barcoded cDNA

- Breaking emulsions and pooling barcoded cDNA

- cDNA purification and amplification via PCR

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Fragmentation of amplified cDNA

- Size selection and clean-up

- Addition of sample indices and sequencing adaptors

- Quality control and quantification of final libraries

- Sequencing on appropriate Illumina platforms (NovaSeq, NextSeq) [20]

Future Perspectives and Integrative Approaches

The field of single-cell genomics continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping future applications. Spatial transcriptomics technologies represent a natural extension of scRNA-seq, preserving the spatial context of RNA transcripts within tissues that is lost during tissue dissociation for conventional scRNA-seq [19] [38]. This spatial information is crucial for understanding cellular interactions within tissue microenvironments, particularly in cancer, immunology, and developmental biology.

Multi-omics approaches that combine scRNA-seq with measurements of genomic variation, chromatin accessibility, DNA methylation, and protein expression from the same single cells provide complementary layers of information that enable more comprehensive characterization of cellular states [37]. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with scRNA-seq data is also accelerating drug discovery, enabling pattern recognition in large datasets to predict drug responses and identify novel therapeutic targets [33] [37].

As these technologies continue to mature and decrease in cost, scRNA-seq is poised to become a standard tool in biomedical research and clinical applications, ultimately enabling more precise diagnostics and targeted therapies tailored to individual patients and specific cellular subpopulations [34] [36].

The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has transformed our understanding of complex biological systems, particularly in oncology where cellular heterogeneity plays a crucial role in disease progression and treatment response. Unlike bulk RNA sequencing, which averages gene expression across thousands to millions of cells, scRNA-seq enables researchers to profile gene expression at the resolution of individual cells [3] [20]. This technological advancement has proven invaluable for dissecting the complex cellular ecosystems of tumors, revealing rare cell populations, and uncovering mechanisms of drug resistance that were previously obscured in bulk analyses [39] [40].

This case study explores how scRNA-seq is applied to investigate the tumor microenvironment and drug resistance mechanisms, focusing on specific research applications in glioblastoma and breast cancer. We will examine experimental protocols, key findings, and the distinct advantages that scRNA-seq offers over bulk RNA sequencing approaches in precision oncology research.

Bulk vs. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing: A Technical Comparison

Fundamental Technological Differences

Bulk RNA sequencing and single-cell RNA sequencing differ fundamentally in their resolution and applications. Bulk RNA-seq analyzes the average gene expression from a population of cells, making it suitable for identifying overall expression differences between conditions but masking cellular heterogeneity [3] [18]. In contrast, scRNA-seq isolates individual cells before sequencing, allowing researchers to investigate gene expression variations within heterogeneous populations and identify rare cell types that would be undetectable in bulk analyses [3] [20].

The experimental workflows also differ significantly. Bulk RNA-seq typically involves RNA extraction from tissue or cell populations, followed by library preparation and sequencing. scRNA-seq requires specialized single-cell isolation techniques, such as droplet-based microfluidics (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium system) or combinatorial barcoding approaches, which incorporate cell-specific barcodes and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to track individual cells and transcripts [20] [41].

Comparative Performance and Applications

Table 1: Key Differences Between Bulk RNA-seq and Single-Cell RNA-seq

| Feature | Bulk RNA Sequencing | Single-Cell RNA Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Average of cell population [3] | Individual cell level [3] |

| Cost per Sample | Lower (~$300 per sample) [3] | Higher (~$500-$2000 per sample) [3] |

| Data Complexity | Lower | Higher [3] |

| Cell Heterogeneity Detection | Limited | High [3] [20] |

| Rare Cell Type Detection | Limited | Possible [3] |

| Gene Detection Sensitivity | Higher | Lower [3] |

| Ideal Applications | Differential expression analysis, transcriptome annotation, alternative splicing analysis [3] [18] | Cellular heterogeneity studies, rare cell identification, developmental biology, tumor microenvironment characterization [3] [18] |

Figure 1: Comparison of bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing applications and outputs

Case Study 1: Drug Resistance in Recurrent Glioblastoma

Experimental Design and Methodology