Cell Surface RNA: From Foundational Biology to Therapeutic Innovation

This article synthesizes the rapidly advancing field of cell surface RNA localization, a paradigm-shifting concept where nuclear-encoded RNAs are stably displayed on the extracellular face of the plasma membrane.

Cell Surface RNA: From Foundational Biology to Therapeutic Innovation

Abstract

This article synthesizes the rapidly advancing field of cell surface RNA localization, a paradigm-shifting concept where nuclear-encoded RNAs are stably displayed on the extracellular face of the plasma membrane. We explore the foundational principles of membrane-associated extracellular RNAs (maxRNAs), detailing their mechanistic basis and biological roles in cell-cell and cell-environment interactions. The review provides a critical analysis of cutting-edge methodologies for maxRNA profiling and validation, including Surface-seq, RNA proximity labeling, and surface-specific FISH. We further address key technical challenges and comparative analyses, concluding with an examination of the immense translational potential of cell surface RNAs as biomarkers and therapeutic targets for drug development professionals.

Redefining the Cell Surface: The Discovery and Significance of Membrane-Associated Extracellular RNAs (maxRNAs)

The classical paradigm of RNA compartmentalization holds that nuclear-encoded RNAs (ngRNAs) are largely restricted to the intracellular space, with any extracellular presence typically attributed to vesicle encapsulation or cell death. Recent research challenges this view by identifying a stable population of membrane-associated extracellular RNAs (maxRNAs) on the cell surface of intact cells. This technical guide explores the discovery, validation, and functional significance of maxRNAs, introducing specialized methodologies for their study and discussing their implications for cell-cell communication and therapeutic development. The emergence of maxRNA biology necessitates a fundamental reconsideration of RNA localization and function in eukaryotic cells.

The maxRNA Paradigm: Redefining Cellular RNA Geography

Historical Context and Conventional RNA Localization Dogma

Traditional cell biology has established a clear compartmentalization of biomolecules: proteins, glycans, and lipids perform essential functions at the cell surface, while nucleic acids, particularly nuclear-encoded RNAs, remain intracellular constituents. According to classical models, any ngRNAs found outside the cell membrane were attributed to pathological states such as cell death and membrane damage, or to specific export mechanisms via extracellular vesicles [1]. This understanding is being fundamentally reconsidered with the discovery of maxRNAs—nuclear-encoded RNAs stably attached to the cell surface and exposed to the extracellular space under physiological conditions [1] [2].

The conceptual foundation for surface-localized RNAs initially emerged from bacterial studies, where non-coding RNAs were found to form ribonucleoprotein complexes with transmembrane proteins and incorporate into the cell membrane [1]. In human cells, preliminary evidence suggested that some ngRNAs could bind membrane lipids under physiological ionic conditions, and atomic force microscopy revealed that RNAs can coat artificial phospholipid membranes [1]. These early findings hinted at a potentially conserved biological phenomenon that contradicted established eukaryotic RNA localization paradigms.

Defining Characteristics of maxRNAs

MaxRNAs are formally defined as membrane-associated extracellular RNAs that meet three specific criteria [1]:

- Nuclear encoded: Transcribed from the nuclear genome unlike mitochondrial RNAs

- Stably membrane-associated: Firmly attached to the plasma membrane rather than weakly adsorbed

- Extracellularly exposed: Positioned on the outer cell surface, accessible to extracellular probes

This definition specifically excludes RNAs encapsulated within cellular or extracellular vesicles, and cell-free RNAs not stably attached to cell membranes [1]. The stable association with the plasma membrane distinguishes maxRNAs from artifacts of cell damage or dying cells, where RNA release occurs passively through compromised membrane integrity.

Methodological Innovations for maxRNA Research

The investigation of maxRNAs requires specialized techniques that can distinguish surface-exposed RNAs from intracellular RNAs while maintaining membrane integrity. Standard RNA detection methods typically involve membrane permeabilization, rendering them unsuitable for maxRNA studies.

Surface-seq: High-Throughput maxRNA Identification

Surface-seq represents a groundbreaking approach for the comprehensive identification and sequencing of maxRNAs. This nanotechnology-based method leverages membrane-coated nanoparticles (MCNPs) that preserve the native orientation of plasma membrane components [1].

Table: Surface-seq Technical Variations

| Variation | Methodology | RNA Population Captured | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variation A | RNA extraction from assembled MCNPs followed by library construction | All membrane-associated RNAs (both sides) | Comprehensive maxRNA profiling |

| Variation B | Direct ligation of 3' RNA adaptor to outside-facing RNAs on MCNPs | Outside-facing membrane RNAs only | Specific identification of extracellularly exposed maxRNAs |

The Surface-seq workflow involves [1]:

- Membrane purification: Isolation of plasma membranes from target cells

- MCNP assembly: Tight assembly of membranes around polymeric cores, maintaining inside-outside orientation

- RNA processing: Variation-specific RNA isolation and library construction

- High-throughput sequencing: Comprehensive RNA sequencing and bioinformatic analysis

Application of Surface-seq to EL4 cells identified 200-400 long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) across replicate libraries, with 82 lncRNAs consistently detected across all experiments, including Malat1, Neat1, and Snhg20 [1]. The reads were not uniformly distributed across transcripts but enriched at specific regions, suggesting potential functional domains or binding sites.

Surface-FISH: Validation of Surface Localization

Surface-FISH (RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization) provides orthogonal validation of maxRNA identification through direct visualization. This technique adapts conventional RNA-FISH by eliminating the membrane permeabilization step, thereby restricting signal exclusively to surface-exposed RNAs [1].

Protocol: Surface-FISH for maxRNA Validation [1]

- Probe design: Five quantum-dot-labeled oligonucleotide probes (40 nt each) targeting specific regions of candidate maxRNAs

- Hybridization: Incubation of live, intact cells with probe sets without permeabilization

- Control experiments: Parallel hybridization with mutant probes (6 central base pairs mutated) to establish specificity

- Signal detection: Imaging and quantification of surface foci using fluorescence microscopy

- Viability confirmation: Co-staining with transmission-through-dye (TTD) markers to verify membrane integrity

Application of Surface-FISH to EL4 cells confirmed the surface presence of Malat1 and Neat1 transcripts, with nearly all cells exhibiting 1-10 surface foci when probed with wild-type but not mutant probes (p < 0.0001) [1]. The combination with TTD microscopy demonstrated that these signals originated from cells with intact membranes, ruling out leakage from damaged cells.

In Situ Surface FISH (isFISH) with Imaging Flow Cytometry

For primary cell analysis, particularly with heterogeneous populations like peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), researchers have developed isFISH coupled with imaging flow cytometry (IFC). This approach enables [1]:

- High-throughput quantification of maxRNA-positive cells

- Cell-type specificity determination through simultaneous surface marker detection

- Single-cell resolution of maxRNA expression patterns

In practice, isFISH employs a randomized library of fluorescence-labeled 20-mer oligonucleotides to probe for putative maxRNAs on PBMCs, followed by six-channel IFC analysis detecting brightfield, viability, nuclear staining, maxRNA signal, and cell surface markers (CD14, CD3ε, CD19) [1]. Appropriate controls include randomized 6-mer libraries, species-specific RNA probes, and fluorophore-only conditions.

Quantitative Profiling of maxRNAs: Composition and Specificity

Rigorous characterization of maxRNA populations reveals distinctive compositional features and cell-type-specific expression patterns that underscore their potential functional significance.

maxRNA Composition in Model Systems

Application of Surface-seq to EL4 cells demonstrated that maxRNAs are not random samples of the cellular transcriptome but represent specific RNA populations with distinctive features [1]:

Table: maxRNA Profiling in EL4 Cells

| RNA Category | Detection in Surface-seq | Representative Transcripts | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long non-coding RNAs | 200-400 lncRNAs across replicates | Malat1, Neat1, Snhg20 | 82 lncRNAs shared across all libraries |

| Outside-facing maxRNAs | 17 lncRNAs enriched in Variation B | Malat1 | Significantly enriched on extracellular surface (FDR < 0.05) |

| Spatial distribution | Non-uniform read distribution | Enriched at center of Malat1 | Suggests specific domains may mediate surface association |

The non-uniform distribution of Surface-seq reads across transcripts like Malat1, with particular enrichment around the center of the transcript, suggests that specific structural domains or sequence motifs may facilitate membrane association or surface presentation [1].

Cell-Type Specificity in Primary Human Cells

Analysis of primary human PBMCs reveals that maxRNA expression exhibits marked cell-type specificity, supporting their potential functional specialization rather than stochastic surface adsorption [1]:

- Overall frequency: 4.8% of total PBMCs exhibited isFISH signals, representing a 27-fold enrichment over control groups (p < 0.005)

- Monocyte enrichment: >10% of CD14+ monocytes were maxRNA-positive

- Lymphocyte presence: Approximately 3% of CD3ε+ T cells showed maxRNA signals

- Statistical significance: Cell-type differences were statistically significant (p < 0.005, t-test)

This cell-type-specific expression pattern follows the "guilt-by-association" principle, suggesting that maxRNAs likely contribute to specialized functions of the presenting cells [1]. The particular enrichment in monocytes implies potential roles in innate immunity or vascular interactions.

Functional Significance: maxRNAs in Cellular Adhesion

Beyond their mere presence on the cell surface, emerging evidence indicates that maxRNAs participate in specific cellular functions, particularly in mediating cell-cell interactions.

Functional Assessment via Antisense Oligonucleotides

To probe maxRNA function, researchers have employed extracellular application of antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) targeting candidate maxRNAs. This approach tests whether specific disruption of surface RNA presentation affects cellular behavior while avoiding intracellular RNA interference mechanisms [1].

Experimental Protocol: Functional maxRNA Interference [1]

- Candidate prioritization: Selection of 11 candidate maxRNAs from monocyte Surface-seq data

- ASO design: Antisense oligos targeting FNDC3B and CTSS transcripts

- Extracellular application: Incubation of ASOs with intact monocytes without transfection agents

- Functional assay: Measurement of monocyte adhesion to vascular endothelial cells under static or flow conditions

- Quantification: Enumeration of adherent monocytes under various treatment conditions

This experimental paradigm demonstrated that extracellular application of ASOs targeting FNDC3B and CTSS maxRNAs significantly inhibited monocyte adhesion to vascular endothelial cells [1]. The functional effect of surface RNA disruption suggests that these maxRNAs play active roles in mediating cellular interactions rather than serving as passive surface decorations.

Implications for Cell-Cell and Cell-Environment Interactions

The inhibition of monocyte adhesion following maxRNA targeting suggests several mechanistic possibilities for maxRNA function [1]:

- Direct interaction with complementary RNAs on opposing cells

- Modulation of surface protein activity or presentation

- Stabilization of adhesion complexes through RNA-protein interactions

- Receptor-like signaling upon ligand binding

These findings collectively position maxRNAs as functional components of the cell surface, potentially expanding the molecular vocabulary for cell-cell and cell-environment interactions beyond the established protein-, glycan-, and lipid-centric mechanisms [1].

Conducting maxRNA research requires specialized reagents and computational resources designed specifically for surface RNA analysis and RNA biology more broadly.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for maxRNA Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Membrane-Coated Nanoparticles (MCNPs) | Plasma membrane purification and orientation preservation | Polymeric cores for stable membrane assembly; maintains inside-outside orientation |

| Quantum-Dot-Labeled Oligonucleotides | Surface-FISH probe design | 40-nt probes with quantum dot fluorophores; mutant controls for specificity |

| Randomized Oligo Libraries | isFISH probing of heterogeneous maxRNA populations | 20-mer fluorescence-labeled oligonucleotides; 6-mer controls for background assessment |

| Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs) | Functional perturbation of specific maxRNAs | Designed for extracellular application without transfection |

| RNA-KG Knowledge Graph | Contextualizing maxRNA findings within broader RNA biology | Integrates data from 60+ public databases; 673,825 nodes and 12,692,212 edges [3] |

| miRNATissueAtlas 2025 | Reference for conventional RNA localization patterns | 61,593 samples across 74 organs and 373 tissues; includes H. sapiens and M. musculus [4] |

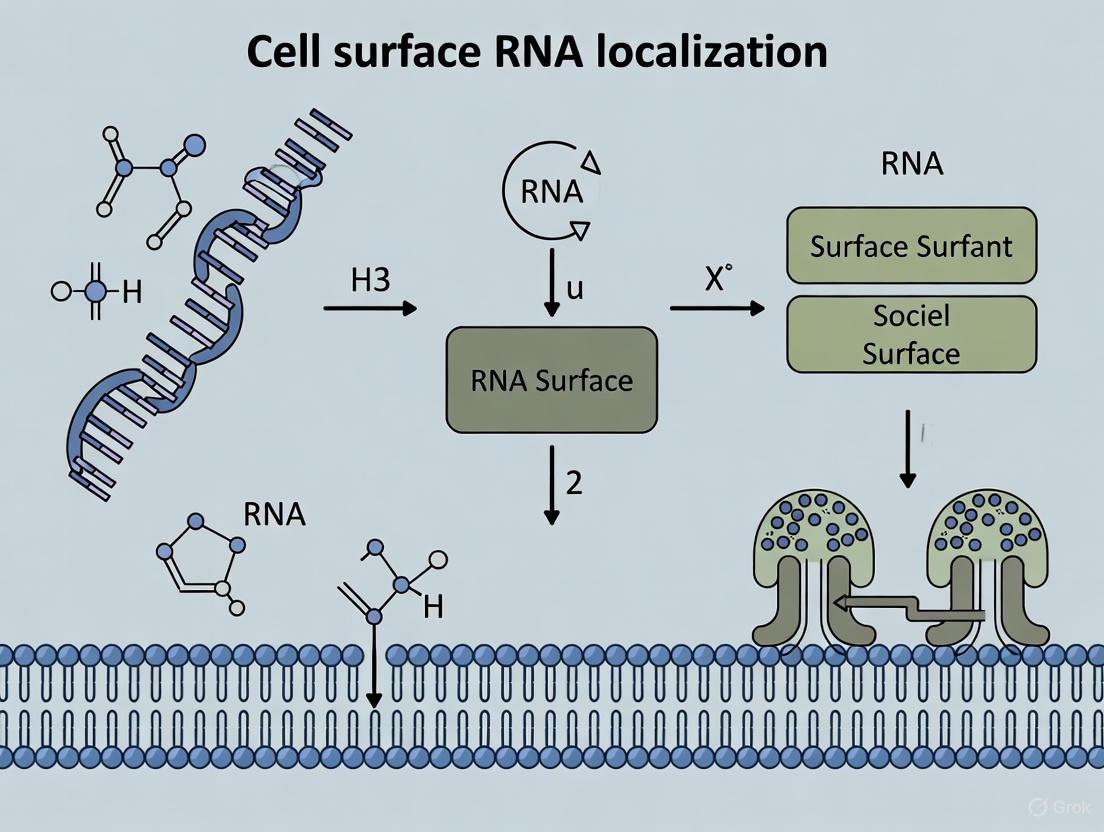

Visualizing maxRNA Research: Experimental Workflows and Conceptual Framework

The following diagrams illustrate key methodological approaches and conceptual models in maxRNA research, providing visual references for experimental design and data interpretation.

Surface-seq Methodology: maxRNA Identification

Surface-FISH Workflow: maxRNA Validation

Functional Analysis: maxRNA Perturbation

Future Directions and Therapeutic Implications

The emerging field of maxRNA biology presents numerous unanswered questions and promising research directions that intersect with drug development and therapeutic innovation.

Unresolved Questions in maxRNA Biology

Key outstanding questions include [1] [5]:

- Mechanisms of surface localization: How are specific RNAs selectively trafficked to and retained at the cell surface?

- Structural determinants: What RNA sequences, modifications, or structural features enable stable membrane association?

- Homeostatic regulation: How are maxRNA levels regulated in response to cellular states or environmental cues?

- Evolutionary conservation: To what extent are maxRNA mechanisms and functions conserved across eukaryotic species?

Therapeutic Potential and Diagnostic Applications

The functional demonstration that extracellular ASOs targeting maxRNAs can modulate cellular adhesion suggests several therapeutic avenues [1]:

- Inflammatory disease modulation: Targeting monocyte-endothelial adhesion in atherosclerosis or autoimmune conditions

- Cancer intervention: Disrupting circulating tumor cell adhesion and metastatic niche formation

- Diagnostic biomarkers: Utilizing cell surface RNA profiles for disease detection or immune monitoring

- Drug delivery: Leveraging maxRNA localization mechanisms for targeted therapeutic delivery

The established success of RNA-based therapeutics, including mRNA vaccines and RNA-targeting drugs, provides a robust foundation for developing maxRNA-focused therapeutic strategies [3]. The RNA-KG knowledge graph, integrating information from over 60 databases, offers a powerful resource for contextualizing maxRNA findings within the broader landscape of RNA biology and therapeutic development [3].

The discovery and characterization of maxRNAs fundamentally challenges classical views of RNA compartmentalization, revealing an expanded role for RNA in cell-surface biology and intercellular communication. Through specialized methodologies like Surface-seq and Surface-FISH, researchers can now systematically identify, validate, and functionally characterize these membrane-associated extracellular RNAs. The cell-type-specific expression and functional involvement in cellular adhesion processes position maxRNAs as potential therapeutic targets and diagnostic tools. As this emerging field progresses, maxRNA biology promises to reshape our understanding of cell surface composition and RNA functionality in health and disease.

The cell surface serves as the primary interface for interactions between a cell and its external environment, playing crucial roles in signal transduction, intercellular communication, and immune surveillance [6]. Traditionally, this landscape was considered to be composed predominantly of proteins, glycans, and lipids. However, a paradigm-shifting body of evidence now demonstrates that nuclear-encoded RNAs (ngRNAs) are also stably present on the extracellular surface of intact cells [1] [7]. This discovery challenges the long-held belief that ngRNAs are confined to the intracellular compartment and suggests a vastly expanded role for RNA in cellular communication. The validation of these membrane-associated extracellular RNAs (maxRNAs) and glycosylated RNAs (glycoRNAs) represents a fundamental advance in cell biology, with significant implications for understanding immune regulation, cancer biology, and therapeutic development [6] [8]. This technical guide synthesizes the key evidence, methodologies, and mechanistic insights validating the presence of nuclear-encoded RNA on the cell surface, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for this emerging field.

Foundational Evidence and Key Validating Experiments

The initial discovery of cell surface RNAs required overcoming significant technical challenges, primarily the difficulty in distinguishing RNAs stably attached to the external membrane from intracellular RNA or RNA contained within extracellular vesicles. Through rigorous experimental approaches, multiple independent research groups have now confirmed the existence and functional significance of cell surface RNAs.

Surface-seq: Systematic Identification of maxRNAs

A groundbreaking advancement came from bioengineers at UC San Diego, who developed Surface-seq, a specialized nanotechnology for the specific detection of membrane-associated extracellular RNAs (maxRNAs) [1] [7]. This technique is based on a membrane-coating nanotechnology that preserves the native inside-outside orientation of the plasma membrane. The multi-step methodology is detailed below:

Table 1: Core Steps of the Surface-seq Protocol

| Step | Process Description | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Membrane Extraction | Plasma membrane is purified from intact cells. | Preservation of native membrane topology with extracellular face outward. |

| 2. Nanoparticle Assembly | Extracted membrane is assembled around polymeric cores to form membrane-coated nanoparticles (MCNPs). | Rigorous removal of intracellular contents while retaining membrane-associated molecules. |

| 3. RNA Capture & Sequencing | RNAs on the MCNP exterior are captured and sequenced. | Selective identification of outside-facing, membrane-associated RNAs. |

Application of Surface-seq to EL4 cells consistently identified specific long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) on the cell surface, including MALAT1 and NEAT1 [1]. Validation experiments confirmed these RNAs were not artifacts of membrane damage, as they remained detectable on cells with intact membranes verified by transmission-through-dye (TTD) microscopic analysis [1].

Independent Validation via Alternative Methodologies

Further confirmation emerged from independent research using different methodological approaches. One study utilized synthetic DNA G-quadruplex (G4) structures as probes to investigate cell surface RNA, finding that a significant amount of RNA, primarily fragments 20–100 nucleotides in length including microRNAs, is associated with the cell surface across various cell lines [9]. Another pivotal study reported that small non-coding RNAs can be modified by N-glycans, forming what are now termed glycoRNAs, which are present on the cell surface [6] [9]. These glycoRNAs were shown to be synthesized via the endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi pathway, a process dependent on the oligosaccharyltransferase (OST) complex, and have been identified as potential ligands for Siglec family immunoregulatory receptors [6].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Detection and Validation

To equip researchers with practical tools for investigating cell surface RNA, this section details the primary protocols used in key studies. Mastery of these techniques is essential for generating validated data in this field.

Surface-FISH for Direct Visualization

Surface RNA Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (Surface-FISH) was developed to visually confirm the presence of specific maxRNAs on the exterior of live cells without permeabilizing the membrane [1]. The protocol involves:

- Probe Design: A set of five quantum-dot-labeled oligonucleotide probes (each 40 nt) are designed to target specific regions of the candidate RNA (e.g., MALAT1).

- Hybridization: Live, intact cells are incubated with the probe set. A critical control uses probes with six centrally-located mutated bases (mut-Malat1) to confirm signal specificity.

- Image Acquisition & Analysis: Cells are imaged using fluorescence microscopy. Valid maxRNA signals appear as distinct foci on the cell surface. Researchers typically examine 20-30 single cells per probe-set, with signal counts compared to mutation-control probes using statistical tests like the Wilcoxon rank test [1].

Functional Probing with Antisense Oligonucleotides

Functional roles of maxRNAs can be investigated by applying antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) to the extracellular environment of live cells [1]. This technique leverages the accessibility of surface RNAs for potential therapeutic targeting.

- Procedure: Fluorescence-labeled ASOs are hybridized to maxRNAs on the surface of primary human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs).

- Detection & Sorting: The binding is analyzed via imaging flow cytometry (IFC), which can be combined with single-cell RNA sequencing to identify the specific maxRNA transcripts and the cell types presenting them.

- Functional Assay: The physiological role is tested by applying ASOs against specific maxRNAs (e.g., FNDC3B and CTSS) and assessing changes in cellular behavior, such as monocyte adhesion to vascular endothelial cells [1].

Analytical Framework and Data Interpretation

Accurate interpretation of cell surface RNA data requires a rigorous analytical framework to distinguish true surface localization from potential artifacts.

Critical Validation Controls

The following controls are essential for any study of cell surface RNA:

- Membrane Integrity Controls: Use dyes like transmission-through-dye (TTD) to confirm the plasma membrane is intact and impermeable to small molecules during experiments [1].

- Probe Specificity Controls: Include control probes with scrambled or mutated sequences to account for non-specific hybridization or background signal [1].

- Enzymatic Controls: Treat cells with extracellular RNase to remove surface-exposed RNA, confirming the localization of the signal. Conversely, use proteases to assess if RNA attachment is protein-mediated, as this can increase RNA accessibility in some cases [9].

Quantitative Profiling and Comparative Analysis

The table below synthesizes key characteristics of the major classes of cell surface RNAs identified to date, providing a comparative overview for researchers.

Table 2: Comparative Profile of Validated Cell Surface RNA Types

| Feature | maxRNA | glycoRNA |

|---|---|---|

| Primary RNA Types | Long non-coding RNAs (e.g., MALAT1, NEAT1) [1] | Small non-coding RNAs (snRNAs, snoRNAs, miRNAs) [6] |

| Key Modification | Not specified | N-glycans rich in sialic acid and fucose [6] |

| Anchoring Mechanism | Not fully elucidated; potential lipid or protein mediation [1] | Association with glycosylation machinery; acp3U nucleotide as a potential anchor [6] |

| Validated Functions | Modulation of monocyte adhesion [1] | Immune recognition via Siglec receptors and P-selectin [6] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Research in this field relies on a specialized set of reagents and tools. The following table catalogues essential solutions for designing experiments on cell surface RNA.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cell Surface RNA Studies

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Membrane-coated Nanoparticles (MCNPs) | Isolate and preserve the native orientation of the cell membrane for Surface-seq. | Polymeric cores coated with purified plasma membrane [1] [7]. |

| Quantum-dot-labeled FISH Probes | Visualize specific RNA molecules on the cell surface without permeabilization. | 40-nt oligonucleotide probes targeting MALAT1 or NEAT1 [1]. |

| Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs) | Functionally block or target surface RNAs for therapeutic investigation. | ASOs against FNDC3B and CTSS to inhibit monocyte adhesion [1]. |

| Metabolic Labeling Agents | Tag newly synthesized RNA to track its trafficking to the cell surface. | 5-ethynyl uridine (EU) for in vivo labeling [10]. |

| Glycan-Binding Proteins | Probe for the presence and function of glycosylated RNAs (glycoRNAs). | Siglec-Fc chimeric proteins, P-selectin [6]. |

| Specific Enzymes | Characterize the molecular environment of the surface RNA. | RNase A (removes surface RNA), Proteases (cleaves surface proteins) [9]. |

Visualizing Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for the Surface-seq technology, a foundational method for profiling maxRNAs.

The detection of glycoRNAs relies on different biochemical principles, primarily targeting the unique glycan modifications on the RNA, as shown in the workflow below.

The validation of nuclear-encoded RNA on the cell surface represents a fundamental expansion of our understanding of the molecular geography of the cell. Techniques like Surface-seq, Surface-FISH, and glycoRNA profiling have provided robust, multi-faceted evidence for this phenomenon. These surface RNAs are not random debris but functional molecules implicated in critical processes like immune cell adhesion and intercellular signaling [1] [11]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this new class of surface biomolecules opens a promising frontier. The external accessibility of maxRNAs and glycoRNAs makes them attractive targets for novel therapeutic strategies, including the use of ASOs, which are easier to develop than antibodies [7]. Future research will undoubtedly focus on elucidating the precise biogenesis and transport mechanisms of these RNAs, exploring their full functional repertoire in health and disease, and ultimately harnessing their potential for precision medicine and next-generation diagnostics.

The traditional paradigm of RNA as a solely intracellular molecule has been fundamentally challenged. Recent research has revealed a rich landscape of diverse RNA species, including long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs), and mRNA fragments, on the extracellular surface of mammalian cells. This whitepaper synthesizes current understanding of cell surface RNA localization, biological functions, and experimental methodologies for their study. We highlight the metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (Malat1) as a paradigm-shifting example of a nuclear lncRNA with regulated cytoplasmic and surface presence in neuronal cells. The discovery of surface RNAs opens new avenues for understanding cell signaling, immune recognition, and developing RNA-based diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Technical advances in profiling and visualizing surface RNAs while maintaining membrane integrity are catalyzing this emerging field, with profound implications for cancer research, neuroscience, and immunology.

RNA localization has long been recognized as a fundamental mechanism for post-transcriptional gene regulation, enabling spatiotemporal control of the proteome at subcellular levels. The presence of specific mRNA populations in neuronal axons facilitates rapid adaptive responses to extracellular cues distant from the cell body [12]. Similarly, mitochondrial microRNAs (MitomiRs) regulate energy production and oxidative stress responses within organelles [13]. However, the recent discovery of RNAs positioned on the external surface of plasma membranes represents a revolutionary expansion of RNA functional territories.

This whitepaper examines the diverse RNA species detected on cell surfaces, focusing on the unexpected externalization of various RNA classes. We explore the mechanistic insights from studies of Malat1, a well-characterized nuclear lncRNA now known to traffic to cytoplasmic compartments and potentially to cell surfaces in specific contexts. We further detail the experimental toolkit enabling this emerging field, highlighting methodologies that preserve membrane integrity for authentic surface RNA profiling. The framework presented herein aims to equip researchers with the conceptual and technical foundation to advance our understanding of surface RNA biology and its therapeutic applications.

The Malat1 Paradigm: From Nuclear LncRNA to Regulated Localization

Malat1 represents a compelling case study of an RNA defying traditional classification. Historically defined as a nuclear lncRNA enriched in nuclear speckles and influencing splicing and chromatin organization, Malat1 is now understood to undergo regulated subcellular redistribution under specific physiological conditions.

Cytoplasmic Trafficking in Neurons

Recent research has demonstrated that during neuronal differentiation, a portion of Malat1 transcripts is exported to the cytoplasm, contrary to its predominantly nuclear localization in other cell types [14]. In developing cortical neurons, Malat1 redistributes from the nucleus to cytoplasmic puncta within both axons and dendrites. These puncta increase in number during neuronal maturation and colocalize with Staufen1 protein, a component of neuronal RNA granules formed by locally translated mRNAs [14]. Single-molecule RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) confirms Malat1's presence in neuronal processes, with a higher density observed in axons than dendrites and a decreasing gradient along the processes with increasing distance from the soma [14].

Functional Implications of Localized Malat1

The cytoplasmic localization of Malat1 enables non-canonical functions beyond its nuclear roles. Ribosome profiling in mouse cortical neurons identified ribosome footprints within Malat1's 5' region containing short open reading frames (micro-ORFs) [14]. The upstream-most reading frame (M1) produces a micropeptide whose expression is enhanced by synaptic stimulation with KCl, indicating activity-dependent translation [14]. This finding reclassifies Malat1 as a cytoplasmic coding RNA in the brain, modulating and being modulated by synaptic function. Depletion experiments using antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) revealed that Malat1 affects the expression of pre- and postsynaptic proteins, influencing neuronal maturation and activity [14].

Table: Key Findings on Malat1 Localization and Function

| Aspect | Traditional Understanding | New Paradigm |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Localization | Enriched in nuclear speckles across most cell types [15] | Portions exported to cytoplasm in differentiating neurons [14] |

| Subcellular Distribution | Exclusively nuclear | Localized in puncta within axons and dendrites; associates with Staufen1 [14] |

| Coding Potential | Classified as non-coding RNA | Contains micro-ORFs; produces a micropeptide regulated by synaptic activity [14] |

| Functional Role | Regulates splicing, chromatin organization, transcription [15] | Affects synaptic protein expression; modulates neuronal maturation and activity [14] |

Landscape of Surface RNA Species

Beyond Malat1, a diverse repertoire of RNA species localizes to the extracellular surface of plasma membranes across various cell types. Advanced profiling techniques have revealed an unexpected abundance of noncoding RNAs on the surface of blood cells.

Documented Surface RNA Classes

Application of the AMOUR (A Method for Outer-membrane Unbiased RNA) profiling technology has identified a rich landscape of surface RNAs on human and murine blood cells. This includes Y-family RNAs, the spliceosomal snRNA U5, mitochondrial rRNA MTRNR2, mitochondrial tRNA MT-TA, VTRNA1-1, and the long noncoding RNA XIST [16]. Three-dimensional, nanometer-scale imaging has corroborated the surface localization of RNY5, MTRNR2, and XIST on live human umbilical cord blood mononuclear cells (hUCB-MNCs) [16].

Significance of Surface RNA Composition

The protein partners associated with these surface RNAs provide clues to their potential biological roles. Notably, most RNA-binding proteins associated with the identified surface RNAs have been reported as autoantigens in autoimmune diseases [16]. This association suggests potential involvement in immune recognition and pathological processes, meriting further investigation into their contributions to autoimmunity. The surface RNA landscape appears to be cell-type-specific, suggesting specialized functions across different cellular contexts.

Table: Experimentally Confirmed Surface RNA Species

| RNA Category | Specific Examples | Localization Confirmation Method | Cell Types Demonstrated |

|---|---|---|---|

| LncRNAs | XIST | Intact-Surface-FISH, super-resolution microscopy | hUCB-MNCs [16] |

| Y-RNAs | RNY5 | Intact-Surface-FISH, 3D nanoscale imaging | hUCB-MNCs [16] |

| Mitochondrial RNAs | MTRNR2 (rRNA), MT-TA (tRNA) | Intact-Surface-FISH, flow cytometry | HeLa cells, hUCB-MNCs [16] |

| Spliceosomal RNAs | U5 snRNA | Intact-Surface-FISH | HeLa cells, hUCB-MNCs [16] |

| Vault RNAs | VTRNA1-1 | Intact-Surface-FISH | HeLa cells, hUCB-MNCs [16] |

Experimental Toolkit for Surface RNA Research

Studying surface RNAs presents unique technical challenges, primarily preserving membrane integrity while achieving specific detection. Recent methodological advances now provide a rigorous framework for this emerging field.

Profiling Technologies: AMOUR

The AMOUR (A Method for Outer-membrane Unbiased RNA) technology enables accurate, membrane-preserving profiling of surface RNAs. This T7-based linear amplification method allows comprehensive identification of the outer-membrane RNA repertoire without compromising plasma membrane integrity [16]. As a proof of principle, AMOUR profiling of nucleolar and mitochondrial RNAs closely matched established databases, validating its accuracy [16].

Visualization Technologies: Intact-Surface-FISH

Intact-Surface-FISH (Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization) labels target surface RNAs on live primary cells using fluorescent DNA probes while maintaining cell viability [16]. When coupled with super-resolution microscopy and flow cytometry, this method enables robust visualization and quantification of representative surface RNAs on live cells, providing orthogonal validation of profiling data [16].

Advanced Imaging Tools: PHOTON

For intracellular RNA localization, tools like PHOTON (Photoselection of Transcriptome over Nanoscale) can identify RNA molecules at their native locations within cells [17]. PHOTON uses light-activated DNA-based molecular cages that open when exposed to a narrow laser beam (200-300 nanometers), allowing specific labeling of RNAs in illuminated regions such as particular organelles [17]. This approach has been used to demonstrate that RNAs in stress granules carry significantly more m6A modifications than those outside them, suggesting this modification plays a role in RNA translocation to these structures [17].

Surface RNA Analysis Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table outlines essential reagents and tools for investigating surface and localized RNAs, based on current methodologies.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Surface RNA Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Category | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| AMOUR Technology | Profiling Method | T7-based linear amplification for membrane-preserving surface RNA profiling [16] |

| Intact-Surface-FISH Probes | Detection Reagent | Fluorescent DNA probes for labeling target surface RNAs on live cells [16] |

| PHOTON Molecular Cages | Spatial Mapping | DNA-based cages for light-activated RNA labeling in subcellular compartments [17] |

| Staufen1 Antibodies | Validation Tool | Confirm association with RNA granules in neuronal processes [14] |

| Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs) | Functional Tool | Deplete specific RNAs like Malat1 to study functional consequences [14] |

Biological Significance and Therapeutic Implications

The discovery of diverse RNA species on cell surfaces opens new dimensions for understanding cell-cell communication, immune recognition, and disease mechanisms.

Functional Roles of Surface RNAs

Surface RNAs likely serve as ligands for receptor-mediated signaling, facilitate cell adhesion, or participate in extracellular structural functions. Their association with autoantigens suggests roles in immune recognition, potentially acting as targets or regulators in autoimmune conditions [16]. In specialized cells like neurons, surface RNAs may contribute to synaptic recognition, axon guidance, and neural circuit formation.

Therapeutic Opportunities

Surface RNAs represent promising targets for diagnostic and therapeutic development. Their extracellular accessibility circumvents the challenge of intracellular delivery that has hampered many RNA-based therapeutics. Potential applications include:

- Biomarkers: Surface RNA signatures may serve as disease-specific biomarkers for cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and autoimmune diseases.

- Vaccine Development: Immunogenic surface RNAs could be harnessed for cancer vaccine development.

- Targeted Therapies: Surface RNAs could be targeted with antibody-RNA conjugates or used as homing devices for cell-specific drug delivery.

The emerging understanding of diverse RNA species on cell surfaces, exemplified by the regulated localization of lncRNAs like Malat1, fundamentally expands the functional landscape of RNA biology. These discoveries challenge traditional compartmentalization views and reveal novel mechanisms of cellular communication and regulation. The developing toolkit for surface RNA research—including AMOUR, Intact-Surface-FISH, and PHOTON—provides powerful approaches to decipher the composition, regulation, and functions of surface RNAs across cell types and physiological states. As this field advances, surface RNAs offer promising avenues for therapeutic intervention in cancer, neurological disorders, and autoimmune diseases, potentially leveraging their extracellular accessibility for targeted approaches. Future research will likely uncover additional RNA species on cell surfaces, their trafficking mechanisms, and their specific roles in health and disease.

The conventional understanding of RNA as a solely intracellular molecule has been fundamentally challenged by the recent discovery of a diverse repertoire of RNAs residing on the cell surface. This paradigm shift reveals an unexplored dimension of cellular biology where RNA molecules, particularly glycosylated RNAs (glycoRNAs), localize to the outer cellular membrane and participate directly in critical immune processes [18] [19]. These cell surface RNAs are now recognized as active contributors to immune cell adhesion, signal transduction, and cellular recognition, thereby expanding their functional roles beyond protein coding and gene regulation.

This emerging field sits at the intersection of RNA biology and immunology, revealing how nucleic acids function in extracellular contexts. The presence of specific RNA molecules on the cell surface, often stabilized by interactions with RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and modified by complex N-glycans, establishes a novel mechanism for cell-to-cell communication and immune surveillance [18] [20]. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to provide an in-depth technical guide on the functional implications of cell surface RNAs, with particular emphasis on their mechanisms and roles in the immune system. We will explore the quantitative characterization of these molecules, detail experimental approaches for their study, and discuss their profound implications for therapeutic development.

Cell Surface RNA Profiles and Quantitative Characterization

Initial profiling of cell surface-associated RNA has revealed a complex population of molecules distinct from intracellular transcriptomes. These RNAs are not randomly distributed but represent a specific subset of cellular RNA that becomes associated with the extracellular matrix or outer leaflet of the plasma membrane.

Composition and Physical Properties of Surface RNA

Using synthetic DNA G4 probes to capture cell surface-associated nucleic acids, researchers have quantified basic characteristics of this RNA population across different cell lines [20]. The table below summarizes key physical properties and compositional data:

Table 1: Quantitative Profile of Cell Surface Bound RNA

| Characteristic | Measurement | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Length Distribution | 20-100 nucleotides | Predominantly short fragments |

| RNA Types Present | microRNAs, other cellular RNA fragments | Includes specific microRNA populations |

| Quantity Variation | Varies significantly between cell lines | Cell-type specific expression patterns |

| Response to Protease | Increases over time post-treatment | Suggests protein-mediated anchoring |

| Response to RNase A | Increases over time post-treatment | Reveals dynamic turnover |

| Functional Impact of Removal | Inhibits cell growth, promotes migration | RNase A treatment in culture medium |

The data indicate that surface RNA consists primarily of internal cellular RNA fragments, with a notable presence of microRNAs, which are well-known regulatory molecules in intracellular contexts [20]. The variation in surface RNA quantity across different cell lines suggests cell-type specific regulation of RNA surface presentation, potentially correlated with distinct immunological functions.

Methodological Framework for Surface RNA Analysis

The investigation of cell surface RNAs requires specialized methodologies that distinguish them from the abundant intracellular RNA population. The following experimental workflow provides a reliable approach for profiling and validating surface-bound RNA:

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for Cell Surface RNA Profiling

| Step | Method | Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Selective Labeling | DNA G4 probes or cell-impermeant labels | Tags surface-exposed RNA | Must use non-penetrating reagents |

| 2. Controlled Digestion | Limited extracellular RNase A treatment | Validates surface exposure | Concentration and timing critical |

| 3. RNA Isolation | Modified TRIzol protocols with click chemistry | Recovers biotinylated RNA | For Halo-seq: uses CuACC "click" chemistry [21] |

| 4. Enrichment & Analysis | Streptavidin pulldown + RNA-seq | Identifies surface RNA repertoire | Compare to total cellular transcriptome |

A critical consideration in these experiments is the use of controlled enzymatic treatments to validate surface localization. Treatment with proteases or RNase A can actually increase detectable surface RNA over time, suggesting a dynamic equilibrium between RNA association and dissociation from the cell surface [20]. This may indicate the existence of active regulatory mechanisms controlling RNA presence on the cell surface.

Mechanisms of RNA Localization to the Cell Surface

The presence of RNA on the cell surface defies traditional models of RNA containment within the cell. Understanding the mechanisms that facilitate RNA externalization and stabilization on the plasma membrane is fundamental to appreciating their functional roles.

Trafficking and Anchoring Mechanisms

RNA molecules achieve specific subcellular localization through coordinated processes involving active transport, passive diffusion, and selective anchoring. While traditionally studied in intracellular contexts, these mechanisms appear to operate for surface-localized RNAs as well:

Active Transport: RNA is frequently transported as a component of ribonucleoprotein (RNP) granules along cytoskeletal elements. This process is mediated by motor proteins such as kinesins (on microtubules) and myosins (on actin filaments) [22]. The kinesin-1 motor protein has been specifically implicated in transporting RNAs containing pyrimidine-rich motifs in their 5' UTRs [21].

Anchoring and Stabilization: Once transported near the cell surface, RNAs can be anchored through interactions with RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) that associate with membrane components. Proteins such as nucleolin have been identified as capable of binding RNA on the cell surface [20]. The cytoskeleton plays a dual role in both transport and anchoring, with actin filaments particularly important for refining and stabilizing RNA at specific locations [22].

Glycosylation and Membrane Association: A seminal discovery in this field is the identification of glycoRNAs - small non-coding RNAs covalently modified by complex N-glycans [18]. This glycosylation may facilitate association with membrane components or existing glycoproteins, effectively anchoring RNAs to the cell surface.

The diagram below illustrates the primary mechanisms for RNA localization to the cell surface:

Conservation Across Cell Types

Remarkably, the mechanisms regulating RNA localization demonstrate significant conservation across different cell types with vastly different morphologies. Research has shown that RNA regulatory elements and RNA-binding proteins that regulate localization in one cell type can perform similar functions in other cell types [21]. For instance, pyrimidine-rich motifs in the 5' UTRs of ribosomal protein mRNAs are sufficient to drive RNA localization to both the basal pole of epithelial cells and the neurites of neuronal cells [21]. This cross-cell type functionality suggests the existence of a fundamental "RNA localization code" that transcends specific cellular morphologies.

Functional Roles in Immune Recognition and Adhesion

Surface-localized RNAs, particularly glycoRNAs, have emerged as significant contributors to immune system function. Their position on the cell surface enables direct participation in immune recognition and cell-cell adhesion processes.

Roles in Immune Homeostasis and Surveillance

Cell surface glycoRNAs contribute significantly to immune homeostasis and the orchestration of immune cell behavior [18]. Preliminary research indicates several specific functions:

Immune Cell Adhesion: Surface RNAs facilitate immune cell adhesion and infiltration, potentially through direct or indirect interactions with adhesion molecules on opposing cells [18].

Pathogen Recognition: Some surface RNAs function in pathogen recognition, serving as pattern recognition receptors or co-receptors that enhance immune detection efficiency [23].

Immune Activation: The presence of specific surface RNA profiles can influence immune activation states, potentially through modulation of receptor signaling thresholds [18].

The diagram below illustrates how surface RNAs participate in immune recognition and adhesion:

Immunoglobulin Superfamily Parallels

The functional role of cell surface RNAs shows intriguing parallels with the Immunoglobulin Superfamily (IgSF) of proteins, which are well-established players in immune recognition and adhesion. IgSF proteins contain immunoglobulin-like domains and mediate diverse biological processes including immune recognition, cell adhesion, activation, and signal transduction [24] [23]. Like IgSF proteins, surface RNAs appear to participate in:

- Pathogen Recognition: Similar to IgSF members in invertebrates that recognize pathogens and initiate clearance responses [23].

- Cell-Cell Interaction Mediation: Facilitating specific interactions between immune cells and their targets.

- Signal Modulation: Influencing intracellular signaling pathways following ligand-receptor interactions.

These functional parallels suggest that surface RNAs may represent a nucleic acid-based system for immune recognition that complements or modifies the protein-based IgSF system.

Signaling Transduction Pathways and Mechanisms

Surface RNAs influence intracellular signaling cascades through their interactions with cell surface receptors, particularly those involved in immune signaling. This modulation affects key pathways that determine immune cell fate and function.

Key Signaling Pathways Modulated by Surface RNAs

Research indicates that surface RNAs can influence multiple signaling pathways critical for immune function. The table below summarizes the primary signaling pathways affected and their immunological significance:

Table 3: Immune Signaling Pathways Influenced by Surface RNA Interactions

| Signaling Pathway | Immune Function | Impact of Surface RNA |

|---|---|---|

| NF-κB | Inflammatory responses, cell survival | Potential regulation of immune activation thresholds |

| JAK-STAT1/2 | Antiviral defense, interferon response | May modulate interferon sensitivity |

| JAK-STAT3 | Anti-inflammatory responses, cell differentiation | Possible influence on differentiation fate |

| TGF-β | Immunosuppression, Treg differentiation | Elevated in autoimmune contexts (e.g., RA) [25] |

| PI3K | T cell differentiation, metabolic regulation | May affect metabolic reprogramming |

| MAPK | Cell proliferation, differentiation | Potential influence on immune cell expansion |

Quantitative characterization of these pathway activities using technologies like STAP-STP (Simultaneous Transcriptome-based Activity Profiling of Signal Transduction Pathways) has revealed that different immune cell types display characteristic signaling pathway activity profiles that reflect both their cell type and activation state [25]. Surface RNAs likely contribute to defining these activity profiles.

Intracellular Signal Transduction Mechanisms

The presence of RNAs on the cell surface influences intracellular signaling through several interconnected mechanisms:

Receptor Interaction: Surface RNAs may interact directly or indirectly with cell surface receptors, modulating their activation state and subsequent signaling cascades [18] [19].

Signal Amplification: Like traditional signal transduction pathways, surface RNA-mediated signaling likely involves amplification mechanisms where a limited number of surface interactions generate substantial intracellular responses [26] [27].

Crosstalk with Traditional Pathways: Surface RNA signaling likely intersects with established signaling paradigms, including second messenger systems (cAMP, Ca2+, IP3), protein phosphorylation cascades, and transcriptional regulation [26].

The diagram below illustrates how surface RNA interactions influence intracellular signaling pathways:

Research Reagent Solutions and Methodological Toolkit

The investigation of cell surface RNAs requires specialized reagents and methodologies. The following toolkit summarizes essential materials for studying surface RNA biology:

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Surface RNA Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| DNA G4 Probes | Synthetic DNA probes for surface RNA capture | Identification and quantification of surface-bound RNA [20] |

| Halo-seq | RNA proximity labeling technique | Mapping subcellular RNA localization [21] |

| Click Chemistry (CuACC) | Covalent tagging of alkyne-modified RNAs | Purification of spatially restricted RNAs [21] |

| Cell-Impermeant RNases | Selective degradation of surface RNAs | Validation of surface localization [20] |

| Single-Molecule RNA FISH | High-resolution RNA visualization | Subcellular localization confirmation [21] |

| csRBP Antibodies | Detect cell surface RNA-binding proteins | Identification of RNA anchoring mechanisms [19] |

| Metabolic Labeling | Track RNA trafficking pathways | Elucidate externalization mechanisms [18] |

These reagents enable researchers to overcome the significant technical challenge of distinguishing surface-localized RNA from the abundant intracellular RNA pool. Methods like Halo-seq are particularly valuable as they allow transcriptome-wide assessment of RNA spatial distributions across cellular compartments [21].

Implications for Disease and Therapeutic Development

The emerging understanding of surface RNA biology has profound implications for human disease mechanisms and therapeutic development, particularly in immunology and oncology.

Pathological Implications

Dysregulation of surface RNA expression or function contributes to disease pathogenesis through several mechanisms:

Autoimmunity: Aberrant presentation of surface RNAs or csRBPs may drive autoimmune responses by creating novel antigenic epitopes or altering self-recognition patterns [19]. In rheumatoid arthritis, for example, increased TGFβ signaling pathway activity has been observed in immune cells [25].

Cancer Immunobiology: Tumor cells may manipulate surface RNA profiles to evade immune surveillance. Changes in surface RNA composition could influence immune cell adhesion, infiltration, and activation in the tumor microenvironment [18].

Infectious Disease: Pathogens may exploit or modify host surface RNA profiles to facilitate infection and evade immune detection.

Therapeutic Opportunities

Surface RNAs represent a novel class of therapeutic targets and diagnostic markers with significant clinical potential:

Diagnostic Biomarkers: The specific profile of surface RNAs on immune cells or tumor cells may serve as biomarkers for disease classification, progression monitoring, or treatment response prediction.

Immunomodulatory Therapies: Targeted manipulation of surface RNA interactions could enable precise tuning of immune responses for autoimmune diseases, cancer immunotherapy, or vaccine adjuvants.

Drug Development: Understanding how surface RNAs influence signaling pathway activity (NF-κB, JAK-STAT, etc.) provides new avenues for therapeutic intervention in immune-related disorders [25].

The discovery of functionally active RNAs on the cell surface represents a fundamental expansion of RNA biology into the extracellular space. These surface RNAs, particularly glycoRNAs, play critical roles in immune cell adhesion, signal transduction, and cellular recognition—functions traditionally ascribed to membrane proteins. Their influence on key signaling pathways, including NF-κB, JAK-STAT, and TGF-β, positions them as significant regulators of immune homeostasis.

As research methodologies advance, particularly in spatial transcriptomics and single-cell analysis, our understanding of surface RNA biology will continue to deepen. This emerging field not only enhances our fundamental knowledge of cell biology but also opens new avenues for therapeutic intervention in immunology, oncology, and infectious disease. The continued elucidation of surface RNA mechanisms and functions will undoubtedly yield novel insights into cell-cell communication and immune regulation in the coming years.

A Technical Toolkit: Profiling and Targeting Cell Surface RNA with Advanced Omics and Imaging

Surface-seq represents a groundbreaking methodological framework for the selective sequencing of nuclear-encoded RNAs that are stably associated with the extracellular surface of cell membranes. This technical guide details the experimental workflows, validation methodologies, and functional implications of Surface-seq technology, which enables the systematic identification of membrane-associated extracellular RNAs (maxRNAs). Contrary to conventional understanding that nuclear-encoded RNAs predominantly reside intracellularly, Surface-seq demonstrates that specific RNA fragments are naturally displayed on the outer cell surface and contribute to cellular interactions. This whitepaper provides researchers with comprehensive protocols for implementing Surface-seq, validating maxRNA localization, and assessing functional significance, thereby expanding our understanding of RNA's role in cell-surface biology and creating new avenues for therapeutic development.

The cell surface serves as the crucial interface between a cell's interior and its external environment, traditionally characterized by its complement of proteins, glycans, and lipids that facilitate signal sensing, extracellular matrix anchoring, and intercellular communication. The contribution of RNA to cell surface functions has remained largely unexplored until recently due to the predominant assumption that nuclear-encoded RNAs are confined within intact cellular membranes [1]. Emerging evidence now challenges this paradigm, suggesting that specific RNAs stably associate with the extracellular layer of the plasma membrane under physiological conditions.

Surface-seq technology was developed to systematically investigate these membrane-associated extracellular RNAs (maxRNAs), defined as nuclear-encoded RNAs stably attached to the cell surface and exposed to the extracellular space [28] [1]. This differs fundamentally from vesicle-encapsulated or cell-free RNAs that are not directly membrane-anchored. The discovery of maxRNAs suggests an expanded role for RNA in cell-cell and cell-environment interactions, potentially opening new avenues for biomarker discovery and therapeutic intervention [7]. Compared to protein targets, maxRNAs offer distinct advantages for therapeutic development because they can be targeted by specific antisense oligonucleotides, which are generally easier to develop and optimize than antibody-based therapeutics [7].

Surface-seq Core Methodology

Technology Foundation and Principles

Surface-seq leverages a nanotechnology approach originally developed for creating membrane-coated nanoparticles [1] [7]. The core innovation lies in extracting the plasma membrane from cells and assembling it around polymeric cores to form membrane-coated nanoparticles (MCNPs) that maintain the natural inside-outside orientation of the membrane, with surface molecules facing outward [1]. This process rigorously removes intracellular contents while preserving RNAs that are stably associated with the extracellular layer of the cell membrane [7]. The MCNP platform thereby enables selective access to maxRNAs that would otherwise be contaminated by abundant intracellular RNAs in whole-cell analyses.

Experimental Workflows and Variations

The Surface-seq methodology comprises two primary technical variations that enable differential RNA analysis:

Variation A - Total Membrane-Associated RNA Profiling: After MCNP assembly and washing, total RNA is extracted using phenol-chloroform and constructed into a sequencing library without distinguishing membrane orientation [1]. This approach captures all membrane-associated RNAs regardless of their spatial orientation relative to the membrane.

Variation B - Outside-Facing RNA Enrichment: Following MCNP assembly, RNAs exposed on the outer surface are directly ligated to a 3′ RNA adaptor while still membrane-bound [1]. The RNA is subsequently purified and ligated with a 5′ adaptor. This selective ligation strategy specifically enriches for outside-facing membrane-associated RNAs in the final sequencing library.

Table 1: Surface-seq Technical Variations and Their Applications

| Variation | RNA Population Targeted | Key Processing Step | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variation A | Total membrane-associated RNA | Phenol-chloroform extraction post-MCNP assembly | Comprehensive identification of all membrane-associated RNAs |

| Variation B | Outside-facing RNA only | Direct 3′ adaptor ligation to membrane-bound RNA | Selective enrichment of extracellularly exposed maxRNAs |

The workflow for both variations includes subsequent library preparation, sequencing, and bioinformatic analysis to identify candidate maxRNAs. The sequencing reads typically display non-uniform distribution across transcript regions, with enrichment at specific segments rather than the entire transcript length [1].

Validation and Functional Assessment Methods

Surface-FISH for maxRNA Visualization

Surface-FISH (RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization on the cell surface) was developed to validate the extracellular localization of Surface-seq-identified maxRNAs [1]. This technique adapts single-molecule RNA-FISH by omitting the cell membrane permeabilization step, thereby restricting probe access to extracellularly exposed RNAs [1]. The protocol employs quantum-dot-labeled oligonucleotide probes (40 nt each) targeting specific regions of candidate maxRNAs, with controlled probe sets containing centrally located mutations serving as specificity controls [1].

Key Experimental Steps:

- Probe Design: Five quantum-dot-labeled oligonucleotide probes (40 nt each) designed against target transcript regions identified by Surface-seq

- Control Probes: Mutated versions with six central base substitutions to establish background signal levels

- Hybridization: Live cells incubated with probes without membrane permeabilization

- Signal Detection: Imaging flow cytometry or microscopy to detect surface-bound probes

- Membrane Integrity Validation: Combined with transmission-through-dye (TTD) microscopic analysis to confirm intact membranes [1]

In validation studies, nearly all EL4 cells treated with Malat1 and Neat1 probes exhibited Surface-FISH signals (1-10 foci per cell), while most cells treated with control probes showed no signal (median = 0), with statistical significance of p < 0.0001 by Wilcoxon rank tests [1]. The TTD analysis confirmed that these signals occurred on cells with intact membranes, excluding the possibility of RNA leakage from damaged cells [1].

Functional Interrogation via Antisense Oligonucleotides

The functional role of maxRNAs can be assessed using antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) applied extracellularly to hybridize with exposed transcript regions [28] [1]. This approach was used to investigate maxRNA function in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), where monocytes were identified as the primary maxRNA-positive population [1].

Experimental Protocol:

- Cell Preparation: Freshly isolated human PBMCs from multiple donors (e.g., 120,000 cells per subject, split into aliquots)

- ASO Treatment: Extracellular application of ASOs targeting specific maxRNAs (e.g., FNDC3B and CTSS transcripts)

- Functional Assay: Assessment of cellular interactions such as monocyte adhesion to vascular endothelial cells

- Control Conditions: Include randomized oligonucleotide libraries, species-specific irrelevant RNAs, and fluorophore-only controls

Functional studies demonstrated that extracellular application of ASOs targeting FNDC3B and CTSS transcripts significantly inhibited monocyte adhesion to vascular endothelial cells, providing evidence for the functional relevance of these maxRNAs in cellular interaction processes [28] [1].

Table 2: Quantitative Surface-seq Validation Data from Key Studies

| Experimental Measure | Value/Result | Experimental Context | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface-FISH positive cells | Nearly 100% with target probes vs. median 0 with controls | EL4 cells probing Malat1 and Neat1 | p < 0.0001 (Wilcoxon rank test) |

| maxRNA+ PBMCs | 4.8% of total PBMCs | Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells | 27-fold > control groups (p < 0.005) |

| Cell-type specificity | >10% of CD14+ monocytes, ~3% of CD3ε+ T cells | PBMC subpopulations | p < 0.005 (t-test) |

| Functional effect | Inhibition of monocyte adhesion | ASO targeting of FNDC3B and CTSS | Significant inhibition reported |

Research Reagent Solutions for Surface-seq

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Surface-seq Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Membrane Coating Materials | Polymeric cores for MCNP assembly | Maintain membrane orientation and remove intracellular contents |

| RNA Adaptors | 3′ and 5′ RNA adaptors with distinct barcodes | Selective ligation to outside-facing RNAs (Variation B) |

| Surface-FISH Probes | Quantum-dot-labeled 40nt oligonucleotides; mutated control probes | Visualization and validation of surface RNA localization |

| Antisense Oligonucleotides | ASOs targeting FNDC3B, CTSS, and other maxRNAs | Functional perturbation of maxRNA-mediated processes |

| Cell Markers | CD14, CD3ε, CD19 antibodies with fluorescence tags | Cell type identification and sorting in heterogeneous populations |

| Viability Assays | Transmission-through-dye (TTD) reagents | Confirmation of membrane integrity during Surface-FISH |

| Sequencing Library Prep | Reverse transcription reagents, PCR amplification kits | Library construction from membrane-associated RNA |

Integration with Complementary Technologies

Surface-seq data can be integrated with complementary multi-omics approaches to provide a comprehensive understanding of cell surface biology. Several relevant technologies include:

CITE-seq (Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes by Sequencing): Simultaneously measures gene expression and cell surface protein abundance using DNA-barcoded antibodies [29] [30]. While CITE-seq focuses on surface proteins, it can complement Surface-seq by providing parallel data on the protein composition of the same cell surfaces.

SPIDER (Surface Protein Imputation using Deep Ensembles): A computational approach that predicts surface protein abundance from single-cell transcriptomes using context-agnostic zero-shot deep ensemble models [31]. SPIDER can predict abundance for over 2,500 cell surface proteins and demonstrates how computational methods can extend experimental data.

TARGET-seq+: A recently optimized protocol that combines RNA sequencing, cell surface protein analysis, and genotyping in single cells with improved sensitivity [32]. This method addresses the challenge of studying somatic mutations in pre-malignant and cancerous tissues while capturing surface protein expression.

The integration of Surface-seq with these technologies creates a powerful framework for comprehensive cell surface analysis, enabling researchers to correlate maxRNA presence with surface protein expression, genetic variations, and spatial context in complex biological systems.

Future Directions and Applications

The discovery of maxRNAs through Surface-seq technology opens multiple avenues for future research and therapeutic development. Key areas for further investigation include:

Mechanistic Studies: Understanding how maxRNAs are transported to the cell surface and anchored there represents a crucial next step [7]. This includes elucidating the biogenesis pathways and molecular machinery responsible for maxRNA localization.

Diversity Assessment: Investigating the diversity of cell types, genes, environmental cues, and biogenesis pathways associated with maxRNA expression will reveal the full scope of this phenomenon [7].

Therapeutic Development: Since maxRNAs are accessible on the cell surface without requiring intracellular delivery, they present attractive targets for antisense oligonucleotide therapeutics [7]. The demonstrated functional impact of maxRNA targeting on monocyte adhesion suggests potential applications in modulating cellular interactions in disease contexts.

Biomarker Discovery: The cell-type specificity of maxRNA presentation, with monocytes showing particularly high maxRNA levels, suggests potential for diagnostic and prognostic biomarker development [1].

Surface-seq technology substantially expands our ability to interpret the human genome by revealing that a portion of the genome may regulate cellular presentation and interactions through maxRNA production [7]. This expanded understanding of RNA biology at the cell surface creates new opportunities for basic research and translational applications across biomedical fields.

The subcellular localization of RNA is intimately tied to its function, serving as a key determinant of cellular homeostasis [33]. Asymmetrically distributed RNAs underlie critical biological processes including organismal development, local protein translation, and the three-dimensional organization of chromatin [33]. Where an RNA molecule is located within the cell ultimately determines whether it will be stored, processed, translated, or degraded [33]. This spatial regulation is particularly crucial for cell surface RNA localization, where localized translation enables rapid response to extracellular signals and environmental changes without requiring protein trafficking from distant cellular regions.

Despite its fundamental importance, comprehensively characterizing the spatial transcriptome has presented significant challenges. While classical approaches like biochemical fractionation followed by RNA sequencing ("fractionation-seq") have been applied transcriptome-wide, they cannot be applied to organelles that are impossible to purify, such as the nuclear lamina and outer mitochondrial membrane [33]. Even for purifiable organelles, contamination issues persist [33]. Direct visualization by microscopy, while powerful, faces limitations including the need for designed probe sets, potential relocalization during fixation, spatial resolution limits, and limited information content compared to sequencing [33].

To address these challenges, proximity labeling techniques have emerged as transformative tools that enable mapping of thousands of endogenous RNAs simultaneously in living cells [33] [34]. These approaches allow researchers to capture full sequence details of any RNA type, enabling comparisons across variants and isoforms with high spatial specificity [33]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of two leading proximity labeling methods—APEX-seq and Halo-seq—framed within the context of advancing research into cell surface RNA localization and its therapeutic applications.

Technical Fundamentals of Proximity Labeling

Proximity labeling techniques share a common principle: using genetically engineered enzymes targeted to specific subcellular locations to label nearby biomolecules [34] [35]. The core innovation involves spatially restricted catalytic reactions that tag endogenous molecules within a limited radius of the enzyme's active site, followed by affinity purification and sequencing of the labeled species [33] [34] [35].

These techniques address a critical methodological gap in spatial biology. Traditional biochemical fractionation cannot access many cellular compartments, while microscopy-based approaches struggle with throughput and resolution [33]. Proximity labeling uniquely enables comprehensive, nanometer-resolution mapping of RNA localization in living cells across virtually any subcellular niche [33] [34].

The labeling radius differs significantly between enzymes. APEX2 generates phenoxyl radicals with an extremely short half-life (<1 ms), theoretically restricting labeling to a 20 nm radius [35]. In contrast, HRP has a broader labeling range of 200-300 nm [35], while the reactive oxygen species generated in Halo-seq diffuse approximately 100 nm from their source [34]. This differential labeling radius represents a key consideration when selecting the appropriate technique for specific biological questions.

Table 1: Comparison of Proximity Labeling Enzyme Properties

| Enzyme | Labeling Radius | Activation Method | Reactive Species Half-life | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APEX2 | ~20 nm | H₂O₂ addition | <1 ms [35] | RNA, protein, DNA profiling [33] [35] |

| HRP | 200-300 nm | H₂O₂ addition | Not specified | Historically used for proximity labeling |

| HaloTag (with DBF ligand) | ~100 nm | Green light exposure | Not specified | RNA and protein profiling [34] |

APEX-seq: Methodological Framework

Core Principles and Mechanism

APEX-seq utilizes the engineered peroxidase APEX2 to directly biotinylate RNA molecules in close proximity to the enzyme [33]. The method builds on previous work using APEX2 for spatial proteomics, leveraging its ability to catalyze the one-electron oxidation of biotin-phenol (BP) in the presence of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) [33]. The resulting biotin-phenoxyl radical is short-lived and covalently conjugates to electron-rich regions of RNA molecules, primarily targeting guanine-rich sequences [33].

The APEX2 enzyme can be targeted to specific subcellular locales through genetic fusion to proteins or peptides with known localization [33]. In practice, researchers generate cell lines stably expressing APEX2 fused to localization signals—for example, targeting the outer mitochondrial membrane, endoplasmic reticulum membrane, nuclear lamina, or nucleolus [33]. Correct targeting must be verified by immunofluorescence staining against organelle markers before proceeding with labeling experiments [33].

Experimental Workflow and Protocol

The APEX-seq protocol involves several critical steps that must be optimized for high spatial specificity and minimal background:

Cell Line Development: Generate stable cell lines expressing APEX2 fused to a protein that localizes to the subcellular compartment of interest. Verify correct localization via immunofluorescence [33].

Biotin Labeling: Incubate cells with membrane-permeable biotin-phenol (BP) for optimal loading (typically 30 minutes), followed by addition of H₂O₂ to initiate the labeling reaction for a precisely timed 1-minute window [33]. The short reaction time is critical as the biotin-phenoxyl radical has a half-life of <1 ms, ensuring nanometer spatial resolution [35].

Reaction Termination and RNA Extraction: Immediately after the 1-minute labeling, quench the reaction by removing H₂O₂ and adding radical scavengers. Extract total RNA using standard methods such as TRIzol, maintaining RNA integrity [33].

Streptavidin Enrichment: Incubate the extracted RNA with streptavidin-coated beads under denaturing conditions to dissociate non-covalent complexes. Include optimized denaturing washes to ensure only biotinylated RNA species are enriched [33].

Library Preparation and Sequencing: Proceed with standard RNA-seq library preparation from the enriched RNA fraction, followed by high-throughput sequencing [33].

Table 2: Key Reagents for APEX-seq

| Reagent | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| APEX2 Fusion Construct | Targets labeling to specific subcellular locations | Must verify localization via immunofluorescence [33] |

| Biotin-phenol (BP) | Substrate for peroxidase reaction | Membrane-permeable; requires optimization of concentration [33] |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Activates peroxidase activity | Critical to optimize concentration and labeling time (typically 1 min) [33] |

| Streptavidin Beads | Affinity purification of biotinylated RNA | Require denaturing wash conditions to remove non-specifically bound RNA [33] |

Applications and Validation

APEX-seq has been successfully applied to map transcriptomes at nine distinct subcellular locations, generating a nanometer-resolution spatial map of the human transcriptome [33] [36]. Key biological insights from these applications include:

- Radial organization of the nuclear transcriptome, with gating at the inner surface of the nuclear pore for cytoplasmic export of processed transcripts [33]

- Identification of two distinct pathways for mRNA localization to mitochondria, each associated with specific transcript sets for building complementary macromolecular machines within the organelle [33]

- Direct detection of functional mRNA delivery to the endoplasmic reticulum, the major site of translation for secretory proteins, highlighting the method's utility for studying therapeutic mRNA delivery [37]

Validation experiments demonstrate APEX-seq's remarkable specificity. When targeted to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane (ERM), APEX-seq showed high enrichment of secretory mRNAs (ERM-proximal "true positives") but not negative-control cytosolic mRNAs encoding non-secretory proteins [33]. This nanometer-scale resolution enables distinction between ER-proximal RNAs and cytosolic RNAs only nanometers from the ERM [33].

Halo-seq: A Complementary Approach

Principle and Mechanism