Cross-Platform RNA-Seq Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Transcriptomic Profiling in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive framework for cross-platform RNA-seq comparison, addressing critical challenges and solutions for researchers and drug development professionals.

Cross-Platform RNA-Seq Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Transcriptomic Profiling in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for cross-platform RNA-seq comparison, addressing critical challenges and solutions for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of platform-specific biases and technological evolution from microarrays to advanced spatial transcriptomics. The guide systematically evaluates methodological approaches for data integration, including normalization techniques and machine learning applications for combining microarray and RNA-seq datasets. It further delves into troubleshooting and optimization strategies to mitigate biases from sample preparation through data analysis. Finally, the article presents rigorous validation protocols and comparative performance benchmarks across major commercial platforms, including 10X Xenium, Vizgen MERSCOPE, and Nanostring CosMx. This resource aims to empower scientists with practical knowledge for designing robust transcriptomic studies and successfully implementing cross-platform analysis workflows in both research and clinical contexts.

Understanding RNA-Seq Technology Landscape: From Microarrays to Spatial Transcriptomics

The evolution of transcriptomic technologies has fundamentally reshaped our approach to biological research and drug development. Over the past decades, gene expression analysis has transitioned from hybridization-based microarrays to sequencing-based RNA technologies, enabling unprecedented insights into cellular mechanisms. This shift represents more than merely a change in technical platforms—it embodies a fundamental transformation in how researchers detect, quantify, and interpret the transcriptome. The emergence of next-generation sequencing has expanded the detectable universe of RNA molecules, while continued refinements in microarray technology have maintained its relevance for targeted applications. This guide provides an objective comparison of these platforms, synthesizing experimental data to inform technology selection for research and development programs. Understanding the relative performance characteristics, limitations, and optimal applications of each platform is crucial for researchers navigating the complex landscape of modern transcriptomics.

Technology Fundamentals: Microarray and RNA-Seq

Core Principles and Methodologies

Microarray and RNA-Seq technologies operate on fundamentally different principles for detecting and quantifying gene expression. Microarray technology relies on hybridization between labeled complementary DNA (cDNA) and predefined DNA probes immobilized on a solid surface [1]. The fluorescence intensity at each probe location indicates the abundance of specific RNA transcripts, limiting detection to known, pre-annotated sequences [2]. In contrast, RNA-Seq technology utilizes high-throughput sequencing to directly determine the nucleotide sequence of cDNA molecules converted from RNA [1]. This sequencing-based approach provides a comprehensive, unbiased view of the transcriptome without requiring prior knowledge of the genetic sequence [3].

The distinction in their fundamental operating principles translates to significant differences in experimental workflows and data generation. Microarrays employ a closed-system approach constrained by the predefined probes on the array, while RNA-Seq operates as an open system capable of detecting any RNA molecule present in the sample [1]. This fundamental difference in detection philosophy underlies the varied applications and performance characteristics of each technology.

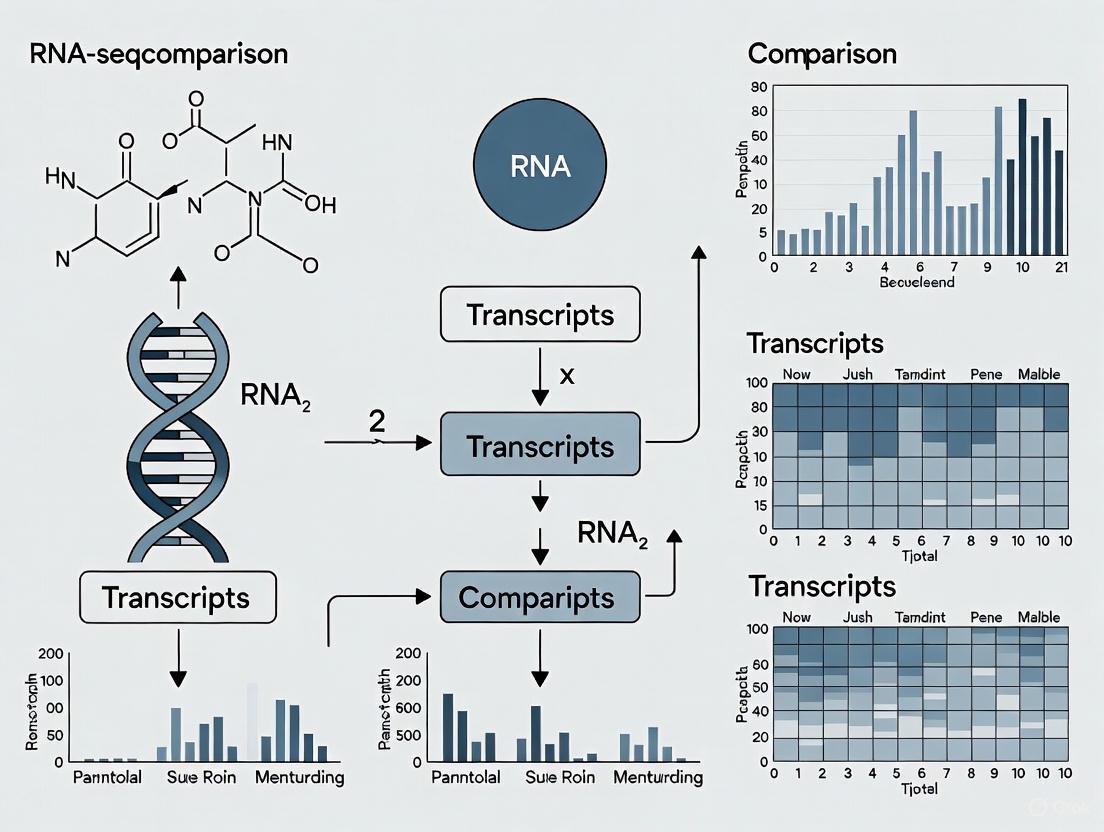

Comparative Workflow Diagrams

The following workflow diagrams illustrate the key procedural differences between microarray and RNA-Seq technologies from sample preparation through data analysis.

Figure 1: Comparative workflows for microarray and RNA-Seq technologies. Microarray relies on hybridization and fluorescence detection, while RNA-Seq utilizes direct sequencing and digital counting.

Experimental Comparisons: Performance and Applications

Case Study: Toxicogenomic Assessment of Hepatotoxicants

A comprehensive 2019 study directly compared microarray and RNA-Seq platforms using liver samples from rats treated with five known hepatotoxicants: α-naphthylisothiocyanate (ANIT), carbon tetrachloride (CCl₄), methylenedianiline (MDA), acetaminophen (APAP), and diclofenac (DCLF) [4]. The experimental protocol maintained strict methodological consistency to enable direct platform comparison.

Experimental Protocol:

- Animal Model: Male Sprague Dawley rats (n=3/group) treated for 5 days with hepatotoxicants at established toxicity doses [4]

- RNA Preparation: Total RNA isolated from flash-frozen liver samples using Qiazol extraction with on-column DNase I treatment; RNA Integrity Number (RIN) ≥9 for all samples [4]

- Microarray Analysis: Samples processed using Affymetrix platform with established normalization and background correction [4]

- RNA-Seq Analysis: 75ng total RNA used for library preparation with TruSeq Stranded mRNA Kit; sequencing on Illumina NextSeq500 platform generating 75bp single-end reads; average 25-26 million reads per sample [4]

- Bioinformatic Processing: RNA-Seq reads aligned using OmicSoft Array Studio with OSA4 alignment algorithm to rat reference genome [4]

Key Findings: Both platforms successfully identified a larger number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in livers of rats treated with ANIT, MDA, and CCl₄ compared to APAP and DCLF, consistent with histopathological severity [4]. The study found approximately 78% of DEGs identified with microarrays overlapped with RNA-Seq data, with strong correlation (Spearman's correlation 0.7-0.83) [4]. However, RNA-Seq demonstrated a wider dynamic range and identified more differentially expressed protein-coding genes [4]. Consistent with known mechanisms of toxicity for these hepatotoxicants, both platforms detected dysregulation of key liver-relevant pathways including Nrf2 signaling, cholesterol biosynthesis, eiF2 signaling, hepatic cholestasis, glutathione metabolism, and LPS/IL-1 mediated RXR inhibition [4].

Case Study: Cannabinoid Concentration Response Modeling

A 2025 study provided an updated comparison using two cannabinoids—cannabichromene (CBC) and cannabinol (CBN)—as case studies to evaluate both platforms for concentration response transcriptomic studies [5]. This research specifically assessed performance in quantitative toxicogenomic applications increasingly used in regulatory risk assessment.

Experimental Protocol:

- Cell Model: Commercial iPSC-derived hepatocytes (iCell Hepatocytes 2.0) cultured following manufacturer protocol [5]

- Exposure Conditions: Cells exposed to varying concentrations of CBC and CBN for 24 hours in triplicate [5]

- Microarray Processing: Total RNA samples processed using GeneChip 3' IVT PLUS Reagent Kit and hybridized to GeneChip PrimeView Human Gene Expression Arrays [5]

- RNA-Seq Processing: Sequencing libraries prepared using Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep, Ligation kit with polyA selection [5]

- Data Analysis: Both datasets analyzed through concentration-response modeling and benchmark concentration (BMC) modeling [5]

Key Findings: The two platforms revealed similar overall gene expression patterns with regard to concentration for both CBC and CBN [5]. Despite RNA-seq detecting larger numbers of differentially expressed genes with wider dynamic ranges, the platforms displayed equivalent performance in identifying functions and pathways impacted by compound exposure through gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) [5]. Most significantly, transcriptomic point of departure (tPoD) values derived through BMC modeling were equivalent between platforms for both cannabinoids [5]. The authors concluded that considering relatively low cost, smaller data size, and better availability of software and public databases, microarray remains viable for traditional transcriptomic applications like mechanistic pathway identification and concentration response modeling [5].

Performance Metrics and Quantitative Comparison

Technical Specification Comparison

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of technical specifications between microarray and RNA-Seq technologies [3] [2] [1]

| Parameter | Microarray | RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Hybridization-based detection | Sequencing-based detection |

| Sequence Requirement | Requires prior sequence knowledge | No prior sequence knowledge needed |

| Dynamic Range | ~10³ | >10⁵ |

| Sensitivity | Moderate | High |

| Coverage | Known transcripts only | All transcripts, including novel ones |

| Novel Transcript Discovery | Not possible | Yes |

| Alternative Splicing Detection | Limited | Comprehensive |

| Single Nucleotide Variant Detection | Limited | Yes |

| Gene Fusion Detection | Limited | Yes |

| Sample Throughput | High | Moderate to High |

| Data Complexity | Lower | Higher |

Experimental Performance Metrics

Table 2: Experimental performance metrics from comparative studies [5] [4]

| Performance Metric | Microarray | RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| DEG Detection Rate | Lower | 20-30% higher |

| DEG Concordance | ~78% overlap | ~78% overlap |

| Pathway Identification | Core pathways detected | Core pathways plus additional insights |

| Non-Coding RNA Detection | Limited or none | Comprehensive |

| Transcriptomic Point of Departure | Equivalent to RNA-Seq | Equivalent to microarray |

| Correlation Between Platforms | Spearman's 0.7-0.83 | Spearman's 0.7-0.83 |

| Platform Reproducibility | High | High |

Technology Selection Guide

Application-Based Decision Framework

The choice between microarray and RNA-Seq depends heavily on research objectives, sample characteristics, and resource constraints. The following decision framework summarizes key considerations for technology selection:

Figure 2: Decision framework for selecting between microarray and RNA-Seq technologies based on research requirements and constraints.

Scenario-Based Recommendations

Table 3: Technology selection guide for specific research scenarios [5] [2] [4]

| Research Scenario | Recommended Technology | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Large cohorts, limited budget | Microarray | Lower per-sample cost, smaller data size, established analysis pipelines |

| Well-annotated genomes | Microarray | Sufficient for detecting known transcripts with cost efficiency |

| Non-model organisms | RNA-Seq | No requirement for predefined probes, enables de novo assembly |

| Novel transcript discovery | RNA-Seq | Unbiased detection of novel genes, splice variants, non-coding RNAs |

| Alternative splicing analysis | RNA-Seq | Comprehensive detection of isoform-level expression |

| Toxicogenomic pathway analysis | Both | Equivalent performance for core pathway identification |

| Biomarker discovery & validation | Microarray (initial), RNA-Seq (validation) | Cost-effective screening followed by comprehensive validation |

| Regulatory concentration-response | Both | Equivalent tPoD values, choice depends on budget and throughput needs |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Core Reagent Solutions for Transcriptomic Studies

Table 4: Essential research reagents and materials for transcriptomic studies [5] [4]

| Reagent/Material | Function | Technology Application |

|---|---|---|

| iCell Hepatocytes 2.0 | In vitro liver model system | Both platforms (toxicogenomic studies) |

| TruSeq Stranded mRNA Kit | Library preparation for RNA-Seq | RNA-Seq (Illumina platform) |

| GeneChip 3' IVT PLUS Reagent Kit | Sample labeling and amplification | Microarray (Affymetrix platform) |

| GeneChip PrimeView Human Arrays | Predefined probe sets for gene expression | Microarray (Affymetrix platform) |

| PolyT Magnetic Beads | mRNA enrichment via polyA selection | RNA-Seq (most protocols) |

| RNase Inhibitors | Prevent RNA degradation during processing | Both platforms |

| DNase I Treatment Reagents | Remove genomic DNA contamination | Both platforms |

| Fluorescent Dyes (Cy3/Cy5) | cDNA labeling for detection | Microarray |

| Qiazol Reagent | Total RNA extraction from tissues | Both platforms |

| RIN Assessment Kits | RNA quality control (Bioanalyzer) | Both platforms |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The transcriptomic technology landscape continues to evolve with several emerging trends shaping future applications. Multiomic integration represents a significant frontier, combining genetic, epigenetic, and transcriptomic data from the same sample to provide a comprehensive perspective on biology [6]. The year 2025 is expected to mark a revolution in genomics driven by the power of multiomics and artificial intelligence, bridging the gap between genotype and phenotype [6].

Spatial transcriptomics is another rapidly advancing field, with 2025 poised to be a breakthrough year for spatial biology [6]. New high-throughput sequencing-based technologies are enabling direct sequencing of cells in tissue, empowering researchers to explore complex cellular interactions and disease mechanisms with unparalleled biological precision [6]. The integration of AI into multiomic datasets on characterized clinical samples is creating a foundational bridge with routine pathology, dramatically accelerating biomarker discovery and refining diagnostic processes [6].

While RNA-Seq adoption continues to grow, microarray technology maintains relevance particularly for studies where cost-effectiveness, standardized analysis pipelines, and regulatory acceptance are paramount [5]. The decentralization of clinical sequencing applications is moving testing closer to internal expertise at institutions, making user-friendly workflows and analysis tools increasingly important [6]. Future platform development will likely focus on enhancing data analysis capabilities, reducing computational burdens, and creating more integrated multiomic solutions that respect biological nuance while providing comprehensive molecular profiling.

The evolution from microarray to RNA-Seq technologies has transformed transcriptomic analysis, with each platform offering distinct advantages for specific research contexts. Microarray technology provides a cost-effective, standardized approach suitable for large-scale studies focused on well-annotated genomes, demonstrating equivalent performance to RNA-Seq in identifying toxicologically relevant pathways and deriving transcriptomic points of departure [5]. RNA-Seq offers unbiased, comprehensive transcriptome characterization with superior sensitivity and dynamic range, enabling novel discovery and analysis of complex RNA biology [3] [1].

The choice between these technologies should be guided by specific research objectives, experimental constraints, and desired outcomes. For traditional toxicogenomic applications including mechanistic pathway analysis and concentration-response modeling, microarray remains a scientifically valid and resource-efficient choice [5]. For discovery-driven research requiring detection of novel transcripts, splice variants, or non-coding RNAs, RNA-Seq provides unparalleled capabilities [2]. As the field advances toward increasingly multiomic and spatially resolved analyses, both technologies will continue to contribute valuable insights into gene expression regulation and its implications for health and disease.

The quest to comprehensively measure gene expression has led to the development of two fundamentally distinct technological paradigms: hybridization-based and sequencing-based approaches. While both aim to quantify transcript abundance, their underlying principles, performance characteristics, and applications differ significantly. Hybridization-based methods, including microarrays and various spatial transcriptomics platforms, rely on the complementary binding of fluorescently labeled nucleic acids to predefined probes [7] [8]. In contrast, sequencing-based approaches such as RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) and massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS) involve direct counting of transcript molecules through high-throughput sequencing, providing digital measurements of gene expression [7] [9]. Understanding the key technological differences between these approaches is essential for researchers selecting appropriate methodologies for specific biological questions, particularly in the context of cross-platform comparison studies that reveal significant variations in performance, sensitivity, and reproducibility [10] [8].

Fundamental Principles and Methodological Workflows

Core Principles of Hybridization-Based Technologies

Hybridization-based technologies operate on the principle of complementary base pairing between target nucleic acids and immobilized probes. In traditional DNA microarrays, thousands of predefined probes are attached to a solid surface, and fluorescently labeled cDNA from experimental samples hybridizes to these probes, with signal intensity corresponding to transcript abundance [7] [8]. This approach has evolved into sophisticated spatial transcriptomics methods that preserve spatial context within tissues. Techniques such as 10× Visium, Slide-seq, and HDST utilize barcoded spatial arrays to capture location-specific gene expression information, while in situ hybridization methods like MERFISH and seqFISH+ use iterative hybridization and imaging to localize transcripts within tissue architectures [11] [12]. A key characteristic of hybridization approaches is their dependence on pre-designed probe sets, which inherently limits detection to known transcripts included in the probe design while offering the advantage of targeted, efficient profiling without requiring extensive sequencing resources [11] [8].

Core Principles of Sequencing-Based Technologies

Sequencing-based technologies employ fundamentally different principles centered on direct, high-throughput sequencing of cDNA libraries. RNA-Seq converts RNA populations into cDNA libraries that are sequenced en masse, with transcript abundance quantified by counting the number of reads mapping to each gene or transcript [13] [9]. This approach includes various implementations such as bulk RNA-Seq, single-cell RNA-Seq (scRNA-seq), and spatial transcriptomics methods that incorporate sequencing-based readouts. Unlike hybridization-based methods, sequencing approaches provide digital, discrete measurements of expression through read counts, enable discovery of novel transcripts without prior knowledge of the transcriptome, and offer a broader dynamic range for quantification [7] [9]. Modern sequencing-based spatial transcriptomics methods, including Stereo-seq and DBiT-seq, combine spatial barcoding with high-throughput sequencing to simultaneously map gene expression patterns and tissue architecture at single-cell or subcellular resolution [11] [12].

Visual Comparison of Fundamental Workflows

The diagram below illustrates the core methodological differences between hybridization-based and sequencing-based approaches:

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Comprehensive Performance Metrics Across Platforms

Multiple large-scale benchmarking studies have systematically evaluated the performance characteristics of hybridization-based and sequencing-based technologies. The Quartet project, a multi-center consortium involving 45 laboratories, recently provided comprehensive insights into RNA-seq performance using reference materials with precisely defined "ground truths" [10]. Similarly, a systematic comparison of 11 sequencing-based spatial transcriptomics methods evaluated performance across multiple metrics including sensitivity, resolution, and molecular diffusion [12]. The table below summarizes key performance characteristics based on these and other comparative studies:

Table 1: Performance Comparison Between Hybridization and Sequencing-Based Approaches

| Performance Metric | Hybridization-Based Approaches | Sequencing-Based Approaches | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Lower sensitivity for low-abundance transcripts; detection limited by probe design | Higher sensitivity; capable of detecting low-abundance transcripts | Sequencing methods detected 10-30% more genes in comparative studies [7] [8] |

| Dynamic Range | Limited dynamic range (∼10³) due to signal saturation | Broad dynamic range (∼10⁵) enabled by digital counting | RNA-Seq demonstrates superior quantification across varying expression levels [10] [9] |

| Technical Reproducibility | High reproducibility among technical replicates (Pearson r = 0.95-0.99) | Moderate to high reproducibility (Pearson r = 0.85-0.98) | Microarrays show marginally higher technical reproducibility [8] |

| Cross-Platform Concordance | High concordance between microarray platforms (r = 0.89-0.95) | Moderate concordance between sequencing platforms (r = 0.76-0.92) | Greater inter-laboratory variation in sequencing-based methods [10] |

| Accuracy for Differential Expression | Moderate accuracy, particularly for subtle expression changes | Higher accuracy for detecting subtle differential expression | RNA-Seq outperforms in identifying subtle expression differences [10] |

Detection Capabilities and Expression Correlation

The fundamental differences in detection principles between hybridization-based and sequencing-based technologies lead to notable variations in gene expression measurements. A comprehensive comparison study between multiple DNA microarray platforms and MPSS (Massively Parallel Signature Sequencing) revealed moderate correlations between the two technologies (Pearson correlation coefficients ranging from 0.39-0.52), significantly lower than correlations observed within the same technology category [8]. Discrepancies were particularly pronounced for genes with low-abundance transcripts, where sequencing-based methods generally demonstrated superior detection capabilities [7] [8]. The diagram below illustrates the relationship between transcript abundance and detection efficiency across platforms:

Recent advancements in both methodologies have further highlighted their complementary strengths. For sequencing-based approaches, methods like HybriSeq combine the sensitivity of multiple probe hybridization with the scalability of split-pool barcoding and sequencing, achieving high sensitivity for RNA detection while maintaining specificity through ligation-based validation [14]. In spatial transcriptomics, systematic comparisons reveal that probe-based Visium and Slide-seq V2 demonstrate higher sensitivity in detecting marker genes in specific tissue regions compared to polyA-based capture methods [12].

Experimental Design and Methodological Considerations

Key Experimental Protocols in Cross-Platform Studies

Robust comparison of hybridization-based and sequencing-based technologies requires carefully designed experiments incorporating appropriate controls and reference materials. The Quartet project established a comprehensive framework for RNA-seq benchmarking using well-characterized reference RNA samples from immortalized B-lymphoblastoid cell lines, spiked with External RNA Control Consortium (ERCC) RNA controls [10]. This approach enables the assessment of technical performance using multiple types of "ground truth," including defined sample mixtures with known ratios and reference datasets validated by orthogonal technologies like TaqMan assays. Similarly, systematic comparisons of spatial transcriptomics methods have employed reference tissues with well-defined histological architectures, including mouse embryonic eyes, hippocampal regions, and olfactory bulbs, which provide known morphological patterns for validating spatial resolution and detection sensitivity [12].

For hybridization-based platforms, experimental protocols typically involve: (1) RNA extraction and quality assessment using metrics such as RNA Integrity Number (RIN); (2) reverse transcription and fluorescent labeling; (3) hybridization to arrayed probes under optimized stringency conditions; (4) washing to remove non-specific binding; and (5) signal detection and quantification [7] [8]. Sequencing-based protocols generally include: (1) RNA extraction and quality control; (2) library preparation with either poly(A) selection for mRNA enrichment or ribosomal RNA depletion for total RNA analysis; (3) adapter ligation and library amplification; (4) high-throughput sequencing; and (5) bioinformatic processing including read alignment, quantification, and normalization [13] [15]. Both approaches require careful consideration of batch effects, with recommendations to process experimental and control samples simultaneously and randomize processing order when handling large sample sets [13] [10].

Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

The experimental workflows for both hybridization-based and sequencing-based approaches depend on specialized reagents and platform-specific solutions. The following table details key research reagents and their functions in transcriptome profiling studies:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Transcriptome Analysis

| Reagent/Platform Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms | 10× Visium, Slide-seq, HDST, Stereo-seq, DBiT-seq | Enable spatially resolved gene expression profiling using either hybridization (Visium) or sequencing-based (Stereo-seq) principles [11] [12] |

| In Situ Hybridization Methods | MERFISH, seqFISH+, RNAscope, HybriSeq | Utilize multiple probes and iterative hybridization for highly sensitive spatial RNA detection [11] [14] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep, NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA | Facilitate conversion of RNA to sequencing libraries with options for strand specificity and RNA input flexibility [13] [9] |

| RNA Extraction and QC Tools | PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit, TapeStation System | Ensure high-quality RNA input with accurate integrity assessment (RIN >7.0 recommended) [13] |

| Reference Materials | Quartet Reference RNAs, MAQC Samples, ERCC Spike-In Controls | Enable platform benchmarking and quality control through well-characterized transcriptomes [10] |

| Normalization and QC Reagents | Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs), Spike-In RNAs | Account for technical variability and enable quantitative normalization across samples [14] [10] |

Applications and Complementary Utility in Biomedical Research

Context-Dependent Advantages and Limitations

Each technological approach offers distinct advantages that make it particularly suitable for specific research scenarios. Hybridization-based methods excel in large-scale screening studies where cost-effectiveness and technical reproducibility are primary considerations, and when targeting known transcripts without requiring novel transcript discovery [7] [8]. The inherent targeting of hybridization approaches also provides advantages in clinical diagnostics, where well-defined biomarker panels can be implemented with minimal bioinformatic infrastructure. For instance, in non-small cell lung cancer, targeted RNA-sequencing panels have demonstrated utility in detecting oncogenic fusions, with hybridization-capture-based RNA sequencing identifying rare and novel fusions missed by amplicon-based approaches [16].

Sequencing-based technologies offer superior capabilities for discovery-oriented research, including identification of novel transcripts, alternative splicing variants, fusion genes, and allele-specific expression [15] [9]. The untargeted nature of RNA-Seq makes it particularly valuable for studying organisms without well-annotated genomes, as it does not depend on predefined probe sets [9]. In spatial transcriptomics, sequencing-based methods like Stereo-seq provide higher resolution and greater coverage, enabling comprehensive atlas-building efforts, while hybridization-based approaches offer more accessible solutions for focused studies of specific gene panels [11] [12].

Integration and Complementary Use

Rather than considering hybridization-based and sequencing-based approaches as mutually exclusive alternatives, emerging evidence supports their complementary integration in comprehensive transcriptomics research [7] [8]. Hybridization methods can provide rapid, cost-effective validation of findings from discovery-phase RNA-Seq experiments, while sequencing approaches can resolve ambiguities in microarray results and identify novel features beyond the scope of predefined probe sets. This complementary relationship is particularly evident in spatial transcriptomics, where methods like 10× Visium (utilizing both hybridization- and sequencing-based principles) and DBiT-seq (combining microfluidics with sequencing) are bridging the historical divide between these technological paradigms [11] [12].

The future of transcriptome profiling lies not in the supremacy of one approach over the other, but in the strategic selection and integration of appropriate methodologies based on specific research questions, sample types, and resource constraints. As benchmarking efforts continue to refine our understanding of the strengths and limitations of each technology, researchers are increasingly positioned to make informed decisions that maximize scientific insights while optimizing resource utilization in both basic research and clinical applications.

Imaging vs. Sequencing Spatial Transcriptomics

Spatial transcriptomics has emerged as a revolutionary set of technologies that preserve the spatial location of RNA molecules within tissue architecture, bridging a critical gap between single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and traditional histopathology [17] [18]. While scRNA-seq has provided unprecedented insights into cellular heterogeneity, it fundamentally loses the spatial context essential for understanding cellular communication, tissue organization, and microenvironmental influences in development and disease [17] [18]. The field has rapidly evolved into two dominant technological paradigms: imaging-based and sequencing-based approaches, each with distinct methodologies, capabilities, and trade-offs [19] [18]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these platforms, grounded in experimental data and benchmarking studies, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the appropriate technology for their specific research objectives within the broader context of cross-platform transcriptomics research.

Sequencing-Based Spatial Transcriptomics

Sequencing-based methods (sST) capture RNA from tissue sections using spatially barcoded arrays or beads. Each capture location on the array contains a unique molecular barcode that records spatial information. Following cDNA synthesis, high-throughput next-generation sequencing (NGS) is performed, and computational reconstruction generates a spatial map of gene expression [19] [20].

Key Platforms: Visium HD (10x Genomics) and Stereo-seq (STOmics) are representative platforms. These technologies provide unbiased, transcriptome-wide coverage, capturing all polyadenylated RNA transcripts without prior knowledge of gene targets, making them particularly powerful for discovery-driven research [19] [20].

Imaging-Based Spatial Transcriptomics

Imaging-based approaches (iST) detect RNA molecules directly in fixed tissue sections using fluorescently labeled probes that hybridize to specific target genes. Through multiple cycles of hybridization, imaging, and probe stripping (or in situ sequencing), these methods localize individual mRNA molecules at high resolution. The resulting fluorescent signals are captured by high-resolution microscopes and computationally decoded to generate spatial expression maps [19] [20] [18].

Key Platforms: Xenium (10x Genomics), MERFISH (Vizgen), and CosMx (Nanostring) are leading commercial platforms. These methods are typically targeted, requiring a predefined panel of genes, but offer superior spatial resolution for precise localization studies [19] [20] [21].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Sequencing-Based vs. Imaging-Based Spatial Transcriptomics

| Feature | Sequencing-Based (sST) | Imaging-Based (iST) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Spatial barcoding + NGS | Multiplexed FISH + cyclic imaging |

| Spatial Resolution | Multi-cell to single-cell (e.g., Visium HD: 2μm) [20] | Single-cell to subcellular [19] |

| Gene Throughput | Whole transcriptome (unbiased) [19] | Targeted panels (hundreds to thousands of genes) [19] |

| Key Commercial Platforms | Visium HD, Stereo-seq [19] [20] | Xenium, CosMx, MERFISH [19] [20] [21] |

Performance Benchmarking: A Data-Driven Comparison

Recent systematic benchmarking studies, which utilize serial sections from the same tissue blocks and establish ground truth with complementary omics data, provide robust performance comparisons across critical metrics.

Sensitivity and Transcript Capture Efficiency

Sensitivity refers to a platform's efficiency in detecting RNA molecules present in the tissue. A comprehensive benchmark profiling colon, hepatocellular, and ovarian cancer samples revealed notable differences.

- Gene Expression Correlation with scRNA-seq: Stereo-seq v1.3, Visium HD FFPE, and Xenium 5K showed high correlations with matched scRNA-seq profiles, indicating their consistent ability to capture biological variation. CosMx 6K, while detecting a high total number of transcripts, showed substantial deviation from scRNA-seq reference data [20].

- Marker Gene Detection: For canonical marker genes like EPCAM, all platforms showed well-defined spatial patterns consistent with histology. However, within shared tissue regions, Xenium 5K demonstrated superior sensitivity for multiple marker genes compared to other platforms [20].

Specificity and Accuracy

Specificity measures the technology's ability to avoid false-positive signals, often assessed using negative control probes.

- Background Signals: Imaging-based methods can suffer from false positives due to factors like off-target probe hybridization and optical crowding, where overlapping fluorescence signals in dense transcript regions reduce accuracy [19] [22]. The relationship between sensitivity and specificity is technology-dependent, and adjusting detection parameters to gain true positives often increases false positives [22].

- Spatial Accuracy: In sequencing-based methods, spatial accuracy can be limited when transcripts from multiple cells are captured in a single spot, creating a mixed signal [19].

Resolution and Diffusion Control

This measures the ability to localize transcripts to their precise original position with minimal diffusion.

- Spot Size vs. Molecular Localization: Sequencing-based resolution is dictated by the spot size of the barcoded array (e.g., 0.5 μm for Stereo-seq, 2 μm for Visium HD) [20]. Imaging-based platforms like Xenium and CosMx achieve single-molecule resolution, allowing for precise subcellular localization [20] [18].

- Impact of Sample Prep: Library preparation for sequencing-based methods involves steps that can cause transcript diffusion, potentially blurring spatial resolution [18]. Imaging-based methods, which fix RNA in place, generally offer better diffusion control.

Table 2: Performance Metrics from Benchmarking Studies

| Performance Metric | Sequencing-Based (sST) | Imaging-Based (iST) | Key Evidence from Benchmarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | High, transcriptome-wide [19] | High for targeted genes [19] | Xenium showed superior sensitivity for marker genes; Stereo-seq/Visium HD correlated well with scRNA-seq [20]. |

| Specificity | Accurate transcript identification [19] | Affected by optical crowding, probe design [19] [22] | False positive rates can be >10% for some iST methods claiming super-resolution [22]. |

| Spatial Resolution | Single-cell (2μm for Visium HD) [20] | Subcellular / single-molecule [19] [20] | iST enables precise transcript localization; sST resolution is set by array spot size [19] [20]. |

| Transcript Diffusion | More susceptible during library prep [18] | Better controlled, fixed in situ [18] | - |

| Cell Segmentation | Relies on paired image & algorithms | Relies on nuclear stain & algorithms; 2D segmentation causes errors [22] | Transcript spillover to neighboring cells is a major source of noise in iST data [22]. |

Experimental Design and Protocol Considerations

Sample Preparation and Tissue Requirements

Tissue quality and preparation are critical determinants of success in spatial transcriptomics.

- Preservation Method: The choice between fresh-frozen (FF) and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue is pivotal. FF tissue generally yields higher RNA integrity, ideal for whole-transcriptome sST. FFPE samples, ubiquitous in clinical archives, are compatible with both sST (e.g., Visium HD FFPE) and iST, though RNA is more fragmented [20] [23].

- Sectioning: For all platforms, tissue sections must be thin and uniform (typically 5-10 μm) to ensure optimal imaging and molecular capture [21] [23]. Consecutive serial sections are used for cross-platform benchmarking and validation with complementary assays like CODEX [20].

Key Experimental Steps and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows for sequencing-based and imaging-based spatial transcriptomics, highlighting their fundamental differences.

Sequencing and Imaging Protocols

- Sequencing Depth for sST: While manufacturer guidelines often suggest 25,000–50,000 reads per spot, empirical data from over 1,000 samples indicates that FFPE experiments on Visium often require 100,000–120,000 reads per spot to achieve sufficient transcript recovery and sensitivity [23].

- Imaging Cycles for iST: The number of genes profiled in iST is determined by the panel size and the encoding system, which dictates the number of hybridization and imaging cycles required. Larger panels increase experimental time and complexity, and can exacerbate optical crowding, potentially reducing per-gene sensitivity [23] [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful spatial transcriptomics experiments rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions used in the featured benchmarking experiments and general workflows.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Spatial Transcriptomics

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Spatially Barcoded Slides | Oligo-dT coated slides with positional barcodes for RNA capture. | Core consumable for sequencing-based platforms (e.g., Visium, Stereo-seq) [19]. |

| Gene-Specific Probe Panels | Fluorescently labeled DNA probes targeting mRNA sequences. | Core consumable for imaging-based platforms (e.g., Xenium, CosMx); panel design is critical [19] [21]. |

| CODEX Multiplexed Antibody Panels | DNA-barcoded antibodies for highly multiplexed protein imaging. | Used in benchmarking studies on adjacent sections to establish protein-based ground truth for cell typing [20]. |

| DNase I / Permeabilization Enzyme | Enzymes that control tissue permeabilization for RNA release or probe access. | Critical for optimizing signal intensity; concentration and time must be titrated [23]. |

| NGS Library Prep Kits | Kits for converting captured RNA into sequencing-ready cDNA libraries. | Used in sST workflows; standardization enables scalability [19] [24]. |

| DAPI Stain | Fluorescent stain that binds to DNA in the cell nucleus. | Essential for cell segmentation and nuclear localization in both sST and iST workflows [20] [22]. |

Analysis and Data Integration Strategies

Data Output and Computational Workflows

The data types and subsequent analysis pipelines differ significantly between the two approaches.

- Sequencing-Based Output: Produces digital gene expression matrices (counts per gene per spatial barcode) that are structurally similar to scRNA-seq data. This allows integration with established, trusted bioinformatics pipelines for clustering, differential expression, and spatially variable gene identification [19].

- Imaging-Based Output: Generates massive image files (terabytes per sample) that require extensive computational processing for spot calling, cell segmentation, and transcript decoding. This demands high-performance computing resources and specialized software [19]. A major challenge is accurate cell segmentation, as errors in defining cell boundaries lead to transcript misassignment and are a severe source of noise [22].

Cross-Platform Normalization and Integration

Combining data from different transcriptomics platforms is crucial for leveraging historical data sets. A study evaluating normalization methods for combining microarray and RNA-seq data found that quantile normalization (QN) and Training Distribution Matching (TDM) allowed for effective supervised and unsupervised machine learning on mixed-platform data sets [25]. This underscores the feasibility of integrative analyses to enhance statistical power and discovery.

Integration with Histology via Deep Learning

A promising frontier is the prediction of spatial gene expression patterns directly from routine H&E-stained histology slides using deep learning. Tools like MISO (Multiscale Integration of Spatial Omics) are trained on matched H&E-spTx data to predict expression for thousands of genes at near-single-cell resolution [26]. This approach could potentially augment or guide targeted spatial profiling.

The choice between imaging-based and sequencing-based spatial transcriptomics is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with research goals, sample characteristics, and analytical priorities. The following decision diagram synthesizes the key selection criteria.

Sequencing-based platforms are the tool of choice for discovery-driven research, where the objective is an unbiased profile of the entire transcriptome to identify novel genes, pathways, and cell types without prior assumptions [19]. They also offer greater scalability and cost-effectiveness for studies with large sample sizes [19].

Imaging-based platforms excel in hypothesis-driven research or validation, where the goal is to precisely localize a predefined set of genes at high resolution to map cellular neighborhoods, study subcellular RNA localization, or validate discoveries from sST or scRNA-seq [19] [20].

For the most comprehensive biological insights, these technologies are complementary. A powerful and increasingly common strategy is to use sST for initial discovery and iST for high-resolution validation and spatial context refinement [19] [23]. Furthermore, integrating spatial data with scRNA-seq references is critical for deconvoluting spot-based data in sST and for informing panel design in iST, ultimately leading to a more complete and resolved view of tissue biology.

High-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become a cornerstone of modern transcriptomics, enabling unprecedented discovery of gene expression biomarkers for disease diagnosis, stratification, and treatment response prediction [27]. However, the successful translation of discovered RNA signatures into robust clinical diagnostic tools is often hampered by a critical, yet frequently overlooked, challenge: platform-specific bias and variation. When a transcriptomic signature identified using a discovery platform like RNA-seq is transferred to an implementation platform, such as a targeted nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT), a decline in diagnostic performance is commonly observed [27]. This article objectively compares the performance of major RNA-seq platforms and alternative technologies, framing the discussion within the broader thesis of cross-platform comparison research. We summarize experimental data on performance metrics and provide detailed methodologies to aid researchers and drug development professionals in selecting and validating appropriate transcriptomic technologies.

Performance Comparison of RNA-Seq Technologies

The landscape of RNA-seq technologies is diverse, encompassing short-read sequencing, long-read sequencing, and single-cell approaches. Each platform has distinct strengths and weaknesses that can introduce specific biases, influencing downstream analysis and interpretation.

Table 1: Comparison of Major RNA-Seq Platforms and Key Performance Metrics

| Platform / Technology | Key Characteristics | Read Length | Throughput | Gene/Transcript Sensitivity | Key Biases and Variations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Read RNA-seq (Illumina) | High-throughput, PCR-amplified cDNA sequencing [28] | Short (e.g., 150 bp) [24] | High [28] | Robust for gene-level expression [28] | PCR amplification biases; limited ability to resolve complex isoforms [28] |

| Nanopore Direct RNA-seq | Sequences native RNA without reverse transcription or amplification [28] | Long (full-length transcripts) [28] | Moderate [28] | Identifies major isoforms more robustly [28] | Higher input RNA requirement; different throughput and coverage profiles [28] |

| Nanopore Direct cDNA-seq | Amplification-free cDNA sequencing [28] | Long [28] | Moderate [28] | Similar to Direct RNA-seq [28] | Avoids PCR biases but retains reverse transcription biases [28] |

| Nanopore PCR-cDNA-seq | PCR-amplified cDNA sequencing [28] | Long [28] | Highest for Nanopore [28] | High with sufficient input [28] | PCR amplification biases [28] |

| PacBio Iso-Seq | Long-read, high-accuracy isoform sequencing [28] | Long [28] | Lower than short-read [28] | Excellent for full-length isoform resolution [28] | Higher cost per gigabase; lower throughput [28] |

| 10x Chromium (scRNA-seq) | Droplet-based single-cell 3’ sequencing [29] | Short (3’ biased) | High (number of cells) | Lower per-cell sensitivity [29] | Cell type representation biases (e.g., lower sensitivity for granulocytes) [29]; ambient RNA contamination [29] |

| BD Rhapsody (scRNA-seq) | Plate-based single-cell 3’ sequencing [29] | Short (3’ biased) | High (number of cells) | Similar gene sensitivity to 10x [29] | Cell type representation biases (e.g., lower proportion of endothelial/myofibroblast cells) [29]; different ambient noise profile [29] |

A systematic benchmark from the Singapore Nanopore Expression (SG-NEx) project, which profiled seven human cell lines with five different RNA-seq protocols, provides a direct, data-driven comparison. The study reported that long-read RNA sequencing more robustly identifies major isoforms compared to short-read sequencing [28]. Furthermore, different protocols on the same Nanopore platform showed variations in read length, coverage, and throughput, which can impact transcript expression quantification [28]. In single-cell RNA-seq, a performance comparison of 10x Chromium and BD Rhapsody in complex tissues revealed that while they have similar gene sensitivity, they exhibit distinct cell type detection biases and different sources of ambient RNA contamination [29].

Experimental Protocols for Cross-Platform Benchmarking

Rigorous experimental design is paramount for accurately identifying and quantifying the sources of technical variation between platforms. The following are detailed methodologies from key studies.

Protocol for Comprehensive Long-Read RNA-seq Benchmarking (SG-NEx Project)

The SG-NEx project established a robust workflow for comparing multiple RNA-seq protocols on the same biological samples [28].

- Sample Preparation: Seven human cell lines (e.g., HCT116, HepG2, A549, MCF7, K562, HEYA8, H9) are cultured under standardized conditions.

- Multi-Protocol Sequencing: For each cell line, generate at least three high-quality biological replicates for each of the following protocols:

- Short-read Illumina cDNA sequencing (paired-end, 150 bp).

- Nanopore Direct RNA sequencing.

- Nanopore amplification-free Direct cDNA sequencing.

- Nanopore PCR-amplified cDNA sequencing.

- PacBio IsoSeq (for a subset).

- Spike-in Controls: Include spike-in RNAs with known concentrations (e.g., Sequin, ERCC, SIRVs) in a subset of sequencing runs to evaluate quantification accuracy [28].

- Data Analysis: Process data through a centralized, community-curated nf-core pipeline. Compare protocols based on metrics such as read length, throughput, coverage, and accuracy in quantifying spike-in controls and identifying known transcript isoforms [28].

Protocol for scRNA-Seq Platform Comparison

This protocol is designed to evaluate platform performance in complex tissues [29].

- Sample Preparation: Use fresh tumour samples that present high cellular diversity. To assess performance under challenging conditions, include artificially damaged samples from the same tumours.

- Parallel Sequencing: Process the same sample batch using the platforms under comparison (e.g., 10x Chromium and BD Rhapsody).

- Performance Metrics: For each platform, calculate:

- Gene Sensitivity: The number of genes detected per cell.

- Mitochondrial Content: The percentage of reads mapping to the mitochondrial genome.

- Ambient RNA Contamination: Estimate using empty droplets or background signal.

- Cell Type Representation: Analyze the proportion of major cell types (e.g., endothelial, myofibroblast, granulocytes) identified by each platform after clustering.

- Reproducibility: Assess the correlation of gene expression profiles between technical or biological replicates.

Visualization of Experimental Workflows and Logical Relationships

The following diagrams, created using Graphviz, illustrate the core experimental designs and analytical concepts discussed.

Diagram 1: Conceptual Framework for Cross-Platform Transfer Challenges. This diagram illustrates the traditional decoupled approach to signature discovery and implementation, highlighting the source of the performance gap and a proposed integrative solution.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Multi-Platform Benchmarking. This diagram outlines the parallel sequencing and centralized analysis approach used in comprehensive benchmarking studies like the SG-NEx project.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Computational Solutions

Successful cross-platform research requires both wet-lab reagents and dry-lab computational tools.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Item | Function and Description |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Spike-in RNA Controls (ERCC, Sequin, SIRV) | Synthetic RNA sequences spiked into samples at known concentrations to evaluate the accuracy, sensitivity, and dynamic range of transcript quantification for a given platform [28]. |

| Long SIRV Spike-in RNAs | Specifically designed to assess the performance of long-read RNA-seq protocols in identifying and quantifying complex transcript isoforms [28]. | |

| Cell Lines with Known Transcriptomes | Well-characterized human cell lines (e.g., HCT116, K562) provide a standardized and reproducible biological material for platform comparisons [28]. | |

| Computational Tools & Methods | nf-core RNA-seq Pipeline | A community-curated, portable pipeline for processing RNA-seq data, ensuring reproducible and standardized analysis across different studies and platforms [28]. |

| Cross-Platform Normalization Methods (QN, TDM, NPN) | Computational techniques to minimize platform-specific bias, enabling the combined analysis of data from different technologies (e.g., microarray and RNA-seq) for machine learning applications [25] [30]. | |

| Alignment & Quantification Tools (Gsnap, Stampy, TopHat) | Software used to map sequencing reads to a reference genome or transcriptome. The choice of aligner can influence gene expression level estimates and is a source of variation [24]. | |

| Differential Expression Tools (DESeq, edgeR, Cuffdiff, NOISeq) | Statistical methods applied to read count data to identify differentially expressed genes. Different methods use distinct models and can yield varying results [24]. |

Platform-specific bias and variation are fundamental challenges in transcriptomics, arising from intrinsic differences in technology biochemistry, sensitivity, and data structure. Evidence from systematic benchmarks shows that performance in isoform detection, cell type representation, and quantitative accuracy varies significantly across short-read, long-read, and single-cell platforms. Addressing these challenges requires rigorous experimental designs incorporating spike-in controls and replicated multi-protocol sequencing, coupled with robust computational normalization methods like quantile normalization or Training Distribution Matching. For the field to advance, particularly in clinical translation, a paradigm shift towards embedding implementation constraints during the discovery phase is essential. This integrative approach will mitigate performance gaps and accelerate the development of reliable, cross-platform transcriptomic biomarkers and diagnostic tools.

Dynamic Range and Detection Capabilities Across Platforms

In the field of transcriptomics, the choice of sequencing platform significantly influences the scope, resolution, and biological validity of research findings. "Dynamic range and detection capabilities" refer to a technology's ability to accurately quantify both highly abundant and rare transcripts and to detect diverse RNA species, from common messenger RNAs to novel and non-coding RNAs. The evaluation of these capabilities forms a core component of cross-platform RNA-seq comparison research, providing critical empirical data to guide experimental design in academic and pharmaceutical settings. This guide synthesizes recent, direct comparative studies to objectively evaluate the performance of modern RNA sequencing platforms against traditional and emerging alternatives, providing researchers with the evidence needed to select optimal technologies for their specific applications.

Platform Comparison: Performance Metrics and Experimental Data

Microarray vs. RNA-seq

Overall Performance: A 2024 comparative study of cannabinoid effects on iPSC-derived hepatocytes demonstrated that while RNA-seq identified larger numbers of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with wider dynamic ranges due to its precise counting-based methodology, both microarray and RNA-seq revealed similar overall gene expression patterns and yielded equivalent results in gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and transcriptomic point of departure (tPoD) values through benchmark concentration (BMC) modeling [5].

Technical and Practical Considerations: RNA-seq detects various non-coding RNA transcripts (miRNA, lncRNA, pseudogenes) and splice variants typically missed by microarrays due to the latter's hybridization-based, predefined transcript approach [5]. Despite RNA-seq's advantages in dynamic range and novel transcript detection, microarrays remain viable for traditional applications like mechanistic pathway identification and concentration response modeling, offering benefits of lower cost, smaller data size, and better-supported analytical software and public databases [5].

Table 1: Key Performance Indicators - Microarray vs. RNA-seq

| Performance Metric | Microarray | RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Range | Limited | Wide |

| Novel Transcript Detection | No | Yes (including non-coding RNAs, splice variants) |

| DEG Detection | Fewer DEGs | Larger numbers of DEGs |

| Pathway Identification (GSEA) | Equivalent performance | Equivalent performance |

| Cost Considerations | Lower cost | Higher cost |

| Data Size | Smaller | Larger |

| Analytical Software Maturity | Well-established | Rapidly evolving |

Bulk RNA-seq vs. Single-Cell RNA-seq

Resolution and Applications: Bulk RNA-seq provides a population-average gene expression profile ideal for differential expression analysis between conditions (e.g., disease vs. healthy), tissue-level transcriptomics, and novel transcript characterization [31]. In contrast, single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) resolves cellular heterogeneity by profiling individual cells, enabling identification of rare cell types, cell states, developmental trajectories, and cell type-specific responses to disease or treatment [31].

Performance in Complex Tissues: A 2024 comparative study of high-throughput scRNA-seq platforms (10× Chromium and BD Rhapsody) in complex tumor tissues revealed platform-specific detection biases [29]. BD Rhapsody exhibited higher mitochondrial content, while 10× Chromium showed lower gene sensitivity in granulocytes. The platforms also differed in ambient RNA contamination sources, with plate-based and droplet-based technologies exhibiting distinct noise profiles [29].

Table 2: Technical Comparison - Bulk vs. Single-Cell RNA-seq

| Characteristic | Bulk RNA-seq | Single-Cell RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population average | Single cell |

| Heterogeneity Analysis | Masks cellular heterogeneity | Reveals cellular heterogeneity |

| Rare Cell Detection | Limited | Excellent |

| Cost per Sample | Lower | Higher |

| Sample Preparation | Simpler | Complex (requires single-cell suspensions) |

| Data Complexity | Lower | Higher (requires specialized analysis) |

| Gene Sensitivity | Varies by protocol | Platform-dependent (e.g., lower in granulocytes for 10× Chromium) |

Short-Read vs. Long-Read RNA Sequencing

Transcript-Level Analysis: The 2024 Singapore Nanopore Expression (SG-NEx) project systematically benchmarked Nanopore long-read RNA sequencing against short-read Illumina sequencing and PacBio IsoSeq [28]. Long-read technologies more robustly identify major isoforms, alternative promoters, exon skipping, intron retention, and 3'-end sites, providing resolution of highly similar alternative transcripts from the same gene that remain challenging for short-read platforms [28].

Protocol Variations: Nanopore offers three long-read protocols with distinct advantages: PCR-amplified cDNA sequencing (highest throughput, lowest input requirements), amplification-free direct cDNA (avoiding PCR biases), and direct RNA sequencing (detects RNA modifications, no reverse transcription) [28]. While short-read RNA-seq generates robust gene-level estimates, systematic biases limit precise transcript-level quantification, particularly for complex transcriptional events involving multiple exons [28].

Imaging-Based Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms

Platform Performance: A 2025 benchmark of three commercial imaging-based spatial transcriptomics (iST) platforms—10X Xenium, Vizgen MERSCOPE, and Nanostring CosMx—on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues revealed distinct performance characteristics [32]. Xenium consistently generated higher transcript counts per gene without sacrificing specificity, while both Xenium and CosMx demonstrated RNA transcript measurements concordant with orthogonal single-cell transcriptomics [32].

Cell Type Identification: All three iST platforms enabled spatially resolved cell typing with varying sub-clustering capabilities. Xenium and CosMx identified slightly more cell clusters than MERSCOPE, though with different false discovery rates and cell segmentation error frequencies [32]. The platforms employ different signal amplification strategies: Xenium uses padlock probes with rolling circle amplification; CosMx uses branch chain hybridization; and MERSCOPE directly tiles transcripts with multiple probes [32].

Whole Transcriptome vs. 3' mRNA-Seq

Method Selection Guide: Whole transcriptome sequencing (WTS) provides a global view of all RNA types (coding and non-coding), information about alternative splicing, novel isoforms, and fusion genes, making it ideal for discovery-focused research [33]. In contrast, 3' mRNA-seq excels at accurate, cost-effective gene expression quantification, with a streamlined workflow and simpler data analysis, better suited for high-throughput screening projects [33].

Comparative Performance: Analysis of murine liver samples under different iron diets revealed that while WTS detects more differentially expressed genes, 3' mRNA-seq reliably captures the majority of key differentially expressed genes and provides highly similar biological conclusions at the level of enriched gene sets and differentially regulated pathways [33]. 3' mRNA-seq also demonstrates particular utility for degraded RNA samples like FFPE tissues [33].

Experimental Protocols for Platform Comparison

Microarray and RNA-seq Comparison Methodology

Cell Culture and Exposure: The comparative study of microarray and RNA-seq used iPSC-derived hepatocytes (iCell Hepatocytes 2.0) cultured following manufacturer protocols [5]. Cells were exposed to varying concentrations of cannabinoids (CBC and CBN) in triplicate for 24 hours, with vehicle control groups treated with 0.5% DMSO only [5].

RNA Extraction and Quality Control: Cells were lysed in RLT buffer with β-mercaptoethanol, with total RNA purified using EZ1 Advanced XL automated instrumentation with DNase digestion [5]. RNA concentration and purity were measured via NanoDrop spectrophotometry, and RNA integrity was assessed using Agilent Bioanalyzer to obtain RNA integrity numbers (RIN) [5].

Microarray Processing: Total RNA samples were processed using the GeneChip 3' IVT PLUS Reagent Kit and hybridized onto GeneChip PrimeView Human Gene Expression Arrays [5]. Arrays were stained and washed on the GeneChip Fluidics Station 450, scanned with the GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G, and data were preprocessed using Affymetrix GeneChip Command Console and Transcriptome Analysis Console software with robust multi-chip average (RMA) algorithm [5].

RNA-seq Library Preparation and Sequencing: Sequencing libraries were prepared from 100ng of total RNA per sample using the Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep, Ligation kit [5]. Polyadenylated mRNAs were purified using oligo(dT) magnetic beads, followed by cDNA synthesis and sequencing library construction according to manufacturer protocols [5].

Spatial Transcriptomics Benchmarking Protocol

Sample Preparation: The iST platform comparison utilized tissue microarrays (TMAs) containing 17 tumor and 16 normal tissue types from FFPE samples [32]. Serial sections were processed following each manufacturer's instructions without pre-screening based on RNA integrity to reflect typical workflows for standard biobanked FFPE tissues [32].

Panel Design: For cross-platform comparison, researchers utilized the CosMx 1K panel, Xenium human breast, lung, and multi-tissue panels, and designed custom MERSCOPE panels to match the Xenium breast and lung panels, filtering genes that could trigger high expression flags [32]. This resulted in six panels with each overlapping others on >65 genes [32].

Data Processing and Analysis: Each dataset was processed according to standard base-calling and segmentation pipelines provided by each manufacturer [32]. The resulting count matrices and detected transcripts were subsampled and aggregated to individual TMA cores, generating data encompassing over 394 million transcripts and 5 million cells across all datasets [32].

Long-Read RNA-seq Benchmarking Framework

SG-NEx Project Design: The core dataset consists of seven human cell lines (HCT116, HepG2, A549, MCF7, K562, HEYA8, H9) sequenced with at least three replicates using multiple protocols: Nanopore direct RNA, direct cDNA, PCR cDNA, Illumina short-read, and PacBio IsoSeq [28].

Spike-In Controls and Modification Detection: Sequencing runs included Sequin, ERCC, and SIRV spike-in RNAs with known concentrations to enable quantification accuracy assessment [28]. The dataset also incorporated transcriptome-wide N6-methyladenosine (m6A) profiling to evaluate RNA modification detection capability from direct RNA-seq data [28].

Visualization of Platform Relationships and Workflows

RNA Sequencing Analysis Workflow

Transcriptomics Platform Relationships

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Transcriptomics Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| iPSC-derived Hepatocytes | Physiologically relevant in vitro model for toxicogenomics | Chemical exposure studies, toxicogenomics [5] |

| Spike-in RNA Controls (Sequin, ERCC, SIRV) | Quantification standards for normalization and accuracy assessment | Platform benchmarking, quantification validation [28] |

| Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads | mRNA enrichment by polyA tail selection | RNA-seq library preparation, 3' mRNA-seq [5] |

| RQN Assay (RNA Quality Number) | RNA integrity assessment for sample QC | FFPE sample qualification, RNA degradation assessment [32] |

| Cell Barcoding Oligos | Single-cell identification in multiplexed samples | scRNA-seq, cell partitioning in 10X Chromium [31] |

| Ribosomal Depletion Kits | Removal of abundant ribosomal RNAs | Whole transcriptome sequencing, non-coding RNA analysis [33] |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Solvent for molecular biology reactions | Sample dilution, reagent preparation [5] |

| DNase Digestion Kits | Genomic DNA removal from RNA preparations | RNA purification, reducing background signal [5] |

The dynamic range and detection capabilities of transcriptomics platforms vary significantly across technologies, with clear trade-offs between resolution, throughput, cost, and analytical complexity. Microarrays remain viable for traditional applications despite limited dynamic range, while RNA-seq offers superior detection of novel transcripts and non-coding RNAs. For single-cell resolution, scRNA-seq reveals cellular heterogeneity but introduces platform-specific detection biases and analytical complexity. Emerging technologies like long-read sequencing provide unprecedented isoform-level resolution, and spatial transcriptomics platforms bridge molecular profiling with morphological context. Researchers must align platform selection with experimental goals, considering that while technological advances continue to improve detection capabilities, practical constraints including cost, sample availability, and analytical resources remain decisive factors in experimental design.

Cross-Platform Integration Methods: Normalization, Machine Learning and Data Harmonization

Normalization Techniques for Combining Microarray and RNA-Seq Data

In the evolving landscape of transcriptomics, researchers increasingly face the challenge of integrating data from different technological platforms. Microarray technology, once the cornerstone of gene expression profiling for over a decade, generates continuous fluorescence intensity data through hybridization-based detection [34]. In contrast, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) provides a digital readout of transcript abundance through next-generation sequencing of cDNA molecules [34]. Despite the shifting landscape where RNA-seq now comprises 85% of all submissions to the Gene Expression Omnibus as of 2023, vast quantities of legacy microarray data remain scientifically valuable [34]. This creates a pressing need for robust normalization techniques that enable meaningful integration of datasets generated across these platforms.

Combining microarray and RNA-seq data presents significant methodological challenges due to fundamental differences in their technological principles and output characteristics. Microarrays measure fluorescence intensity through hybridization to predefined probes, suffering from limited dynamic range and high background noise [5]. RNA-seq, based on counting reads aligned to reference sequences, offers wider dynamic range and detection of novel transcripts but introduces biases related to gene length, GC content, and sequencing depth [5] [35]. The selection of appropriate normalization strategies is critical for overcoming these technical disparities to extract biologically meaningful insights from integrated datasets. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of normalization methods and their performance in cross-platform transcriptomic studies, empowering researchers to make informed decisions for their integrative analyses.

Fundamental Technological Differences Between Platforms

Platform-Specific Biases and Technical Variability

The successful integration of microarray and RNA-seq data requires a thorough understanding of their inherent technical characteristics and biases. Microarray technology employs a hybridization-based approach to profile transcriptome-wide gene expression by measuring fluorescence intensity of predefined transcripts [5]. This method suffers from limitations including restricted dynamic range, high background noise, and nonspecific binding [5]. Additionally, microarray data are influenced by probe-specific effects, cross-hybridization, and saturation signals for highly expressed genes. The technology detects only known, predefined transcripts, making it incapable of identifying novel genes or splice variants.

RNA-seq technology operates on fundamentally different principles, based on counting reads that can be reliably aligned to a reference sequence [5]. While RNA-seq provides virtually unlimited dynamic range and can identify various transcript types including splice variants and non-coding RNAs, it introduces its own set of technical biases. These include gene length bias, where longer transcripts generate more fragments; GC content bias, which affects amplification efficiency; and sequencing depth variability across samples [35]. Research has demonstrated that transcripts shorter than 600 bp tend to have underestimated expression levels, while longer transcripts are increasingly overestimated in proportion to their length [35]. Additionally, the higher the GC content (>50%), the more transcripts are underestimated in RNA-seq data [35].

Impact on Gene Expression Measurements

Comparative studies reveal both consistencies and discrepancies in gene expression measurements between platforms. One investigation using identical samples found a high correlation in gene expression profiles between microarray and RNA-seq, with a median Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.76 [34]. However, the same study noted that RNA-seq identified 2,395 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), while microarray identified only 427 DEGs, with just 223 DEGs shared between the two platforms [34]. This discrepancy highlights the importance of normalization strategies that can accommodate the different statistical distributions and detection sensitivities of each platform.

The data structure itself differs substantially between technologies. Microarray data typically consists of continuous, normally distributed intensity values, whereas RNA-seq data are characterized by discrete count distributions that often follow negative binomial distributions [34]. These fundamental differences in data structure necessitate distinct normalization approaches before cross-platform integration can be successfully attempted.

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Microarray and RNA-Seq Technologies

| Characteristic | Microarray | RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Hybridization-based | Sequencing-based |

| Output Type | Continuous intensity values | Discrete read counts |

| Dynamic Range | Limited | Virtually unlimited |

| Background Noise | High | Low |

| Transcript Coverage | Predefined probes only | Can detect novel transcripts |

| Key Technical Biases | Probe specificity, cross-hybridization, saturation | Gene length, GC content, sequencing depth |

Normalization Methods for RNA-Seq Data

Between-Sample and Within-Sample Normalization Approaches

RNA-seq normalization methods are broadly categorized into between-sample and within-sample approaches, each with distinct characteristics and applications. Between-sample normalization methods, including Relative Log Expression (RLE) and Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM), operate under the assumption that most genes are not differentially expressed across samples [36]. RLE, provided by the DESeq2 package, calculates a correction factor as the median of the ratios of all genes in a sample [36]. TMM, implemented in the edgeR package, is based on the sum of rescaled gene counts and uses a correction factor applied to the library size [36]. These methods are particularly effective for correcting for differences in sequencing depth between samples.

Within-sample normalization methods include FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million fragments mapped) and TPM (Transcripts Per Million) [36]. These approaches normalize first by gene length and then by sequencing depth, allowing for comparison of expression levels within the same sample. However, they are less effective for between-sample comparisons when used alone. A newer method, GeTMM (Gene length corrected Trimmed Mean of M-values), has been developed to reconcile within-sample and between-sample normalization approaches by combining gene-length correction with the TMM normalization procedure [36].

Performance Characteristics in Differential Expression Analysis

The choice of normalization method significantly impacts downstream analysis results, particularly in differential expression detection. A comprehensive benchmark study comparing five normalization methods (TPM, FPKM, TMM, GeTMM, and RLE) demonstrated that between-sample normalization methods (RLE, TMM, GeTMM) enabled production of condition-specific metabolic models with considerably low variability compared to within-sample methods (FPKM, TPM) [36]. Specifically, RLE, TMM, and GeTMM showed similar performance in capturing disease-associated genes, with average accuracy of approximately 0.80 for Alzheimer's disease and 0.67 for lung adenocarcinoma [36].

Another evaluation of nine normalization methods for differential expression analysis revealed that method performance varies depending on dataset characteristics [37]. For datasets with high variation and low expression counts, per-gene normalization methods like Med-pgQ2 and UQ-pgQ2 achieved higher specificity (>85%) while maintaining detection power >92% and controlling false discovery rates [37]. In contrast, for datasets with less variation and more replicates, all methods performed similarly, suggesting that the optimal normalization approach depends on specific data characteristics.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of RNA-Seq Normalization Methods

| Normalization Method | Type | Key Features | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| RLE (DESeq2) | Between-sample | Uses median of ratios; robust to outliers | Standard differential expression analysis |

| TMM (edgeR) | Between-sample | Trims extreme log ratios; library size adjustment | Experiments with composition bias |

| GeTMM | Hybrid | Combines gene-length correction with TMM | Both within and between-sample comparisons |

| TPM | Within-sample | Normalizes for gene length and sequencing depth | Single-sample expression profiling |

| FPKM | Within-sample | Similar to TPM, different order of operations | Alternative to TPM for single samples |

| Med-pgQ2/UQ-pgQ2 | Per-gene | Per-gene normalization after global scaling | Data skewed toward lowly expressed counts |

Experimental Protocols for Cross-Platform Normalization

Sample Preparation and Data Generation

Robust cross-platform normalization begins with meticulous experimental design and sample preparation. In a comparative study of microarray and RNA-seq using cannabinoids as case studies, researchers used identical samples for both platforms to minimize biological variability [5]. Commercial iPSC-derived hepatocytes (iCell Hepatocytes 2.0) were cultured following manufacturer's protocol and exposed to varying concentrations of cannabinoids in triplicate [5]. For RNA extraction, cells were lysed in RLT buffer supplemented with β-mercaptoethanol, followed by purification using automated RNA purification instruments with an on-column DNase digestion step to remove genomic DNA [5]. RNA quality was assessed using UV spectrophotometry and Bioanalyzer measurements of RNA Integrity Number (RIN).

For microarray analysis, total RNA samples were processed using the GeneChip 3' IVT PLUS Reagent Kit and hybridized onto GeneChip PrimeView Human Gene Expression Arrays [5]. The process involved generating single-stranded cDNA, converting to double-stranded cDNA, synthesizing biotin-labeled cRNA through in vitro transcription, and fragmenting before hybridization. Microarray chips were stained, washed, and scanned to produce image files that were preprocessed to generate cell intensity files [5]. For RNA-seq, sequencing libraries were prepared using the Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep kit, which includes purification of polyA mRNA from total RNA [5].

Data Processing and Normalization Workflows

Microarray data processing typically involves background correction, quantile normalization, and summarization using algorithms like Robust Multi-Array Averaging (RMA) [34]. The normalized expression data for each probe set are then log2-transformed for downstream analysis. For RNA-seq data, quality control checks are performed with tools like FASTQC, followed by trimming of low-quality reads and adaptor sequences [34]. Reads are aligned to reference transcriptomes, and count data are generated for each gene. At this stage, normalization is critical to address technical variations.