Decoding RNA Extraction Loss: A Complete Guide from Mechanisms to Solutions for Reliable Transcriptomics

Obtaining high-quality, high-yield RNA is foundational for all downstream transcriptomic analyses, yet the process is fraught with potential for significant and often silent RNA loss.

Decoding RNA Extraction Loss: A Complete Guide from Mechanisms to Solutions for Reliable Transcriptomics

Abstract

Obtaining high-quality, high-yield RNA is foundational for all downstream transcriptomic analyses, yet the process is fraught with potential for significant and often silent RNA loss. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, detailing the primary sources of RNA degradation and loss during extraction and purification. We begin by exploring the foundational chemistry of RNA instability and the pervasive threat of ribonucleases (RNases). We then review methodological adaptations for diverse and challenging sample types, from plant tissues to clinical specimens. A dedicated troubleshooting section offers actionable, step-by-step protocols to optimize yield and integrity. Finally, we cover critical validation techniques and comparative analyses of commercial kits to ensure data reliability. Mastering these principles is essential for ensuring the accuracy of gene expression studies, RNA sequencing, and diagnostic assays.

The Fragile Molecule: Understanding the Fundamental Causes of RNA Instability and Loss

1. Introduction: A Major Source of RNA Loss in Research Within the context of RNA extraction and purification, sample degradation represents a primary source of RNA loss and compromised data integrity. Beyond enzymatic ribonuclease activity, the inherent chemical instability of the RNA molecule itself presents a fundamental challenge. This whitepaper details the mechanisms of RNA hydrolysis, with a specific focus on the catalytic role of divalent cations (e.g., Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺). Understanding and mitigating these non-enzymatic degradation pathways is critical for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to maximize RNA yield and quality in applications from qRT-PCR to mRNA vaccine production.

2. Mechanisms of RNA Hydrolysis RNA is susceptible to spontaneous, non-enzymatic hydrolysis of its phosphodiester backbone. Two primary mechanisms dominate:

- Base-Catalyzed Hydrolysis: The 2'-OH group of the ribose sugar acts as an internal nucleophile. Deprotonation of the 2'-OH, facilitated by elevated pH or specific catalysts, leads to a nucleophilic attack on the adjacent phosphorus atom. This forms a 2',3'-cyclic phosphate intermediate, which subsequently hydrolyzes to yield a mixture of 2'- and 3'-nucleoside monophosphates.

- Acid-Catalyzed Hydrolysis: Under acidic conditions (pH < 5), the phosphate group becomes protonated, making the phosphorus atom more electrophilic and susceptible to attack by water. This pathway typically results in random cleavage without the cyclic phosphate intermediate.

The base-catalyzed pathway is significantly more relevant under typical physiological and experimental pH conditions (pH 6-8).

3. Catalytic Role of Divalent Cations Divalent cations, particularly Mg²⁺, play a paradoxical role in RNA biochemistry. While essential for RNA folding and function, they are potent catalysts of RNA cleavage. The catalysis occurs via several interrelated mechanisms:

- Direct Coordination and Activation: The cation directly coordinates with the 2'-oxygen, lowering the pKa of the 2'-OH and facilitating its deprotonation to a more nucleophilic alkoxide.

- Stabilization of Transition States: The positively charged cation stabilizes the developing negative charge on the pentacoordinate phosphorane transition state and the later cyclic phosphate intermediate.

- Indirect Acid Catalysis: The hydrated metal ion (e.g., [Mg(H₂O)₆]²⁺) can act as a Brønsted acid, donating a proton to the 5'-oxyanion leaving group.

Table 1: Catalytic Effect of Divalent Cations on RNA Hydrolysis Rates

| Divalent Cation | Relative Rate Enhancement (vs. no cation) | Optimal Catalytic pH Range | Primary Proposed Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pb²⁺ | > 10,000x | 6.0 - 7.5 | Direct coordination & transition state stabilization. |

| Mg²⁺ | ~ 100x | 7.0 - 8.5 | Direct 2'-O activation & indirect acid catalysis. |

| Ca²⁺ | ~ 50x | 7.0 - 8.5 | Weaker direct coordination, primarily electrostatic. |

| Mn²⁺ | ~ 80x | 6.5 - 8.0 | Similar to Mg²⁺, with higher affinity for phosphate. |

| Zn²⁺ | ~ 500x | 6.0 - 7.5 | Strong direct coordination and hydroxyl activation. |

| No added cation (control) | 1x (baseline) | >9.0 for significant rate | Uncatalyzed base hydrolysis. |

4. Experimental Protocols for Studying Cation-Catalyzed Hydrolysis Protocol 4.1: Kinetic Analysis of Site-Specific RNA Cleavage

- Substrate: A short, well-defined RNA oligonucleotide (e.g., 30-50 nt) with a single, known cleavage-susceptible linkage, often radioisotope or fluorophore labeled at one terminus.

- Buffer Conditions: Use buffers that do not strongly chelate metals (e.g., EPPS, HEPES). Avoid citrate, phosphate, or EDTA.

- Procedure:

- Prepare reaction mixtures with a fixed concentration of RNA (e.g., 1 µM) in buffer at desired pH (e.g., 7.5).

- Add varying concentrations of the divalent cation of interest (e.g., 0.1 mM to 10 mM MgCl₂).

- Incubate at a constant, controlled temperature (e.g., 37°C or 90°C for accelerated studies).

- At timed intervals, withdraw aliquots and quench the reaction by adding excess EDTA (a chelator) and rapid freezing.

- Analyze products via denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and quantify intact vs. cleaved RNA using phosphorimaging or fluorescence.

- Data Analysis: Plot fraction of intact RNA vs. time. Determine observed rate constant (k_obs) for each cation concentration from exponential fits.

Protocol 4.2: Assessing Hydrolysis in Complex Biological Extracts

- Objective: To measure the contribution of cation-catalyzed hydrolysis during lysis before RNase inactivation.

- Procedure:

- Spike a known amount of intact, synthetic control RNA into two identical cell lysates immediately after lysis with a chaotropic agent (e.g., guanidinium thiocyanate).

- To Tube A, add a high concentration of EDTA (e.g., 20 mM final).

- Tube B receives no EDTA or an equimolar control salt (e.g., NaCl).

- Hold both tubes at room temperature for a simulated "processing delay" (e.g., 5-10 minutes).

- Proceed with standard RNA purification (e.g., silica-column binding).

- Elute and analyze the recovered control RNA by capillary electrophoresis (e.g., Bioanalyzer) to compare degradation profiles.

- Interpretation: Greater degradation in Tube B implicates divalent cation activity as a significant source of RNA loss during initial sample processing.

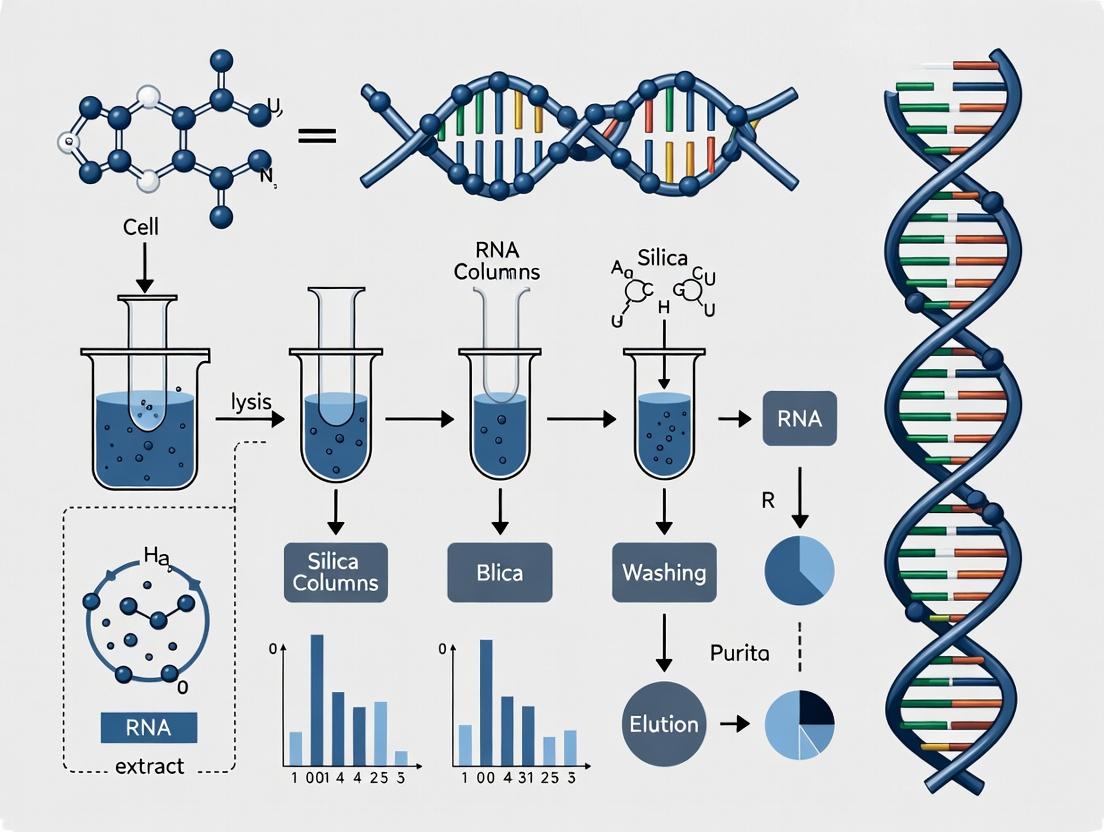

5. Visualization of Mechanisms and Workflows

6. The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Metal Chelators (EDTA, EGTA) | Critical for quenching hydrolysis reactions and chelating divalent cations in storage buffers to suppress background degradation. |

| Metal-Free Buffers (HEPES, EPPS) | Buffers with low affinity for divalent cations allow study of specific cation effects without unintended sequestration. |

| Chaotropic Salts (Guanidinium salts) | Used in lysis buffers to denature RNases; also help dissociate cations from RNA, reducing catalytic hydrolysis. |

| Acidic Phenol (pH ~4.5) | Used during extraction; the low pH minimizes base-catalyzed hydrolysis while partitioning RNA to the aqueous phase. |

| RNA-Stable Tubes (LoBind) | Reduce surface adsorption of RNA and minimize leaching of metal ions from tube plastics that could catalyze hydrolysis. |

| RNase-Free Water (Chelex-Treated) | Treated with Chelex resin to remove trace contaminating divalent cations, providing a clean baseline for reactions. |

| RNA Storage Buffers (with EDTA, pH 7) | Optimized for long-term storage at -80°C, combining pH neutrality, cation chelation, and RNase inhibition. |

| Synthetic RNA Controls | Defined-sequence RNAs used as internal probes to quantify hydrolysis rates in complex lysates or buffer systems. |

7. Mitigation Strategies for RNA Extraction & Purification To minimize RNA loss from cation-catalyzed hydrolysis:

- Rapid Processing: Minimize the time between cell lysis and the addition of chaotropic agents/chelators.

- Chelator Inclusion: Include low concentrations of EDTA (0.1-1 mM) in initial lysis buffers where compatible with downstream purification chemistry.

- pH Control: Maintain slightly acidic conditions (pH 6-6.5) during initial lysis and phenol extraction to slow base-catalyzed pathways.

- Purified Water/Reagents: Use high-purity, metal-depleted water for all buffer preparations.

- Temperature: Process samples on ice whenever possible to reduce the kinetic rate of hydrolysis.

Conclusion The catalytic role of divalent cations in RNA hydrolysis is a significant, yet often overlooked, contributor to RNA degradation during experimental workflows. By integrating an understanding of these chemical pathways with strategic use of chelators, pH control, and optimized protocols, researchers can significantly reduce this non-enzymatic source of RNA loss, thereby improving the yield and reliability of RNA for downstream analytical and therapeutic applications.

In RNA research, from extraction to downstream applications like qRT-PCR, RNA sequencing, and therapeutic development, sample integrity is paramount. A primary contributor to RNA loss and degradation is the ubiquitous presence of Ribonucleases (RNases). This whitepates the major sources of these enzymes, their remarkable stability, and their mechanisms of action, framing this discussion within the critical context of minimizing RNA loss during extraction and purification. Understanding RNase biology is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for obtaining high-quality, reliable RNA data.

RNases are found in almost all living organisms and many environmental samples. Their pervasive nature makes them a constant threat to RNA work.

Table 1: Primary Sources of Ribonucleases

| Source | Common Examples | Key RNase Types Present | Typical Concentration/Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endogenous | Mammalian cells/tissues | RNase A, RNase T1/T2, RNase L, RNase H | Varies by cell type; e.g., Pancreas has [RNase A] ~0.1-1 mg/g tissue |

| Exogenous - Microbial | Bacteria (e.g., E. coli), Fungi, Yeast | RNase I, RNase R, Barnase, RNase T1 | High; E. coli lysate can degrade µg of RNA in minutes |

| Exogenous - Human | Skin, Hair, Saliva, Perspiration | RNase 1, RNase 4, RNase 5 (Angiogenin) | Skin surface: RNase 1 at ~0.1-10 ng/cm² |

| Reagents & Labware | Impure chemicals, Non-sterile water, Used lab equipment | Contaminating microbial or human RNases | Trace amounts sufficient for degradation |

| Environmental | Dust, Aerosols, Surfaces | Mixture of all above | Highly variable; a major contamination vector |

Stability of RNases

The resilience of many RNases to common inactivation methods is a core challenge.

Table 2: Stability of Representative RNases Under Various Conditions

| RNase Type | Heat Stability | Resistance to Denaturants | Autoclaving | pH Stability Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNase A (Bovine) | Retains activity after heating to 100°C | Resistant to 8M Urea; Requires DTT for full denaturation | Not fully inactivated | Active from pH 2-9 |

| RNase T1 (Fungal) | Stable at 60°C; denatures at ~70°C | Moderately resistant | Partially inactivated | Optimal pH 7.5 |

| RNase H (Human) | Denatures at ~60°C | Sensitive to SDS | Inactivated | Optimal pH 7-8 |

| RNase I (E. coli) | Denatures at ~70°C | Sensitive to chaotropic salts | Inactivated | Broad range |

Mechanisms of Ribonucleases

RNases employ distinct catalytic mechanisms and cleavage specificities.

Table 3: Classification and Mechanism of Key Ribonucleases

| Class/Type | Cleavage Specificity | Catalytic Mechanism | Endo- vs Exo-nuclease | Metal Ion Dependence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNase A Superfamily | 3' of Pyrimidine bases (C, U) | Acid-base catalysis (His12, His119, Lys41) | Endonuclease | None (2'-OH acts as nucleophile) |

| RNase T1/T2 Family | 3' of Guanine (T1) / General (T2) | Acid-base catalysis (His, Glu) | Endonuclease | None |

| RNase H | RNA strand in RNA-DNA hybrids | Two-metal-ion mechanism (Mg²⁺/Mn²⁺) | Endonuclease | Mg²⁺ dependent |

| RNase R / RNase II | Single-stranded RNA | Hydrolysis via metal-mediated nucleophile | 3'→5' Exonuclease | Mg²⁺ dependent |

| RNase L | 3' of UN dinucleotides (U/A, U/U) | Acid-base catalysis | Endonuclease | Activated by 2-5A oligomers |

Catalytic Mechanism of RNase A

RNase A is the canonical model for understanding RNase mechanism. It employs a transphosphorylation-hydrolysis two-step process.

Diagram Title: Two-Step Catalytic Mechanism of RNase A

Experimental Protocols for RNase Assessment and Mitigation

Protocol: Testing for RNase Contamination on Surfaces and Reagents

Objective: To detect the presence of RNase activity on labware, surfaces, or in solution reagents. Principle: A synthetic, labeled RNA substrate is exposed to the test sample. Degradation is visualized via gel electrophoresis or fluorometric assay.

Materials:

- Test Sample: E.g., swabbed surface eluate, water, or buffer aliquot.

- Control RNA: A defined, pure RNA transcript (e.g., 0.1-1 kb).

- Incubation Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA.

- Positive Control: Diluted commercial RNase A solution (e.g., 1 pg/µL).

- Negative Control: Nuclease-free water.

- Stop Solution: 5% SDS, 10 mM EDTA.

- Analytical Method: Denaturing Urea-PAGE (8%) or Agilent Bioanalyzer RNA chips.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: For surfaces, swab a 10x10 cm area with a nuclease-free wipe soaked in incubation buffer. Elute into 100 µL buffer.

- Reaction Setup: In nuclease-free tubes, combine:

- 10 µL test sample (or controls)

- 10 µL control RNA (200 ng)

- 5 µL 5X incubation buffer

- Add nuclease-free water to 25 µL final volume.

- Incubation: Incubate at 37°C for 15-30 minutes.

- Reaction Termination: Add 5 µL stop solution, mix, and heat at 70°C for 5 min.

- Analysis: Load entire sample on denaturing urea-PAGE or Bioanalyzer. Intact RNA appears as a discrete band/peak; degradation appears as smearing or lower molecular weight fragments.

Protocol: Evaluating Efficacy of RNase Inhibitors During RNA Extraction

Objective: To compare RNA yield and integrity with/without RNase inhibitors in a simulated extraction. Principle: A standardized tissue lysate spiked with exogenous RNase is processed with various inhibitor regimens. Yield (ng/µL) and Integrity (RIN) are measured.

Materials:

- Tissue Lysate: HeLa cell lysate (prepared in a guanidinium-based lysis buffer).

- RNase Spike: RNase A, 10 pg/µL.

- Test Inhibitors:

- Protein Inhibitors: Recombinant Human RNasin (40 U/µL), SUPERase•In (20 U/µL).

- Chemical Inhibitors: 1% (v/v) Diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water, 10 mM Vanadyl ribonucleoside complex (VRC).

- Physical Barrier: Phase separation (Acid-phenol:chloroform).

- Extraction Kit: Standard silica-column based kit (e.g., Qiagen RNeasy).

- Analysis: Spectrophotometry (A260/280), Bioanalyzer (RIN).

Procedure:

- Lysate Preparation: Aliquot 100 µL of HeLa cell lysate into 6 tubes.

- RNase Challenge: Add 1 µL of RNase A spike to tubes 2-6. Tube 1 is a no-RNase control.

- Inhibitor Addition: Treat tubes as follows for 5 min at 25°C:

- Tube 1 & 2: No inhibitor.

- Tube 3: + 0.5 µL RNasin.

- Tube 4: + 0.5 µL SUPERase•In.

- Tube 5: + 1 µL VRC.

- Tube 6: + 100 µL Acid-phenol:chloroform (mix, then take aqueous phase).

- RNA Extraction: Proceed with silica-column protocol per manufacturer for all tubes.

- Elution: Elute in 30 µL nuclease-free water.

- Quantification & QC: Measure RNA concentration and run on Bioanalyzer for RIN.

Diagram Title: Workflow for Testing RNase Inhibitor Efficacy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for RNase Management

| Item Name | Category | Function & Mechanism | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant RNasin Ribonuclease Inhibitor | Protein Inhibitor | Binds non-covalently to RNase A, B, C in a 1:1 ratio, blocking active site. | Inhibits pancreatic-type RNases; sensitive to oxidation; requires DTT. |

| SUPERase•In RNase Inhibitor | Protein Inhibitor | Broad-spectrum, recombinant inhibitor. Targets RNase A, B, C, 1, T1, I. | More robust than RNasin; active in wider range of buffers. |

| Diethyl Pyrocarbonate (DEPC) | Chemical Inactivator | Carboxyethylates histidine residues in RNases, irreversibly denaturing them. | Used to treat water and solutions; must be inactivated by autoclaving. |

| Vanadyl Ribonucleoside Complex (VRC) | Transition-State Analog | Mimics RNA cleavage transition state, competitively inhibiting many RNases. | Can inhibit some enzymatic reactions (e.g., in vitro translation). |

| Guanidine Hydrochloride / Thiocyanate | Chaotropic Agent | Denatures proteins (including RNases) at high concentrations (>4 M). | Core component of many lysis buffers (e.g., TRIzol). |

| Acid-Phenol:Chloroform | Physical Barrier/Inhibitor | During extraction, denatures and partitions proteins (RNases) into organic phase or interphase. | Effective first line of defense during homogenization. |

| Nuclease-Free Water (DEPC-treated or ultrafiltered) | Reagent | Provides an RNase-free aqueous medium for all solutions and dilutions. | Critical for all downstream steps after initial lysis. |

| RNaseZap / RNase Away | Surface Decontaminant | Chemical mixture (often strong bases and detergents) that denatures RNases on surfaces. | Wipe down benches, pipettes, tube racks before work. |

| RNase Alert Lab Test Kit | Detection Kit | Fluorescence-based assay using an RNA substrate with a quenched fluorophore. Cleavage = signal. | Quick check for RNase contamination in solutions. |

| Agencourt RNAClean XP / AMPure XP Beads | Purification | Solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) beads that bind RNA, allowing wash-away of contaminants. | Effective for removing RNases after enzymatic reactions (e.g., in vitro transcription). |

Within the landscape of RNA extraction and purification research, minimizing RNA loss is a paramount concern. While enzymatic degradation is a well-characterized source of loss, physical shearing represents a significant, yet often underappreciated, mechanistic source of RNA fragmentation, particularly for long transcripts and in mechanically vigorous protocols. This technical guide details the principles, quantitative impact, and methodologies for studying this phenomenon, framing it within the broader thesis of preserving RNA integrity from sample to assay.

The Physics of RNA Shearing

High molecular weight RNA is susceptible to hydrodynamic shear forces. During homogenization (e.g., rotor-stator, bead beating, high-pressure homogenization), fluid flow generates velocity gradients. RNA strands spanning different flow velocities experience tensile stress, leading to chain scission when the force exceeds the covalent bond strength of the phosphodiester backbone. The probability of scission increases with RNA length, applied shear stress, and exposure time.

Quantitative Impact of Homogenization Methods

Recent studies comparing homogenization techniques have quantified RNA integrity loss, primarily measured via the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) or the percentage of intact ribosomal RNA peaks. The following table synthesizes key findings:

Table 1: Impact of Homogenization Method on RNA Integrity

| Homogenization Method | Typical Shear Stress | Relative RNA Integrity (RIN) | Optimal for Tissue Type | Key Risk for Large RNA (>5 kb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual Dounce | Low | High (8.5-10) | Soft tissues (liver, spleen) | Minimal shearing; low throughput. |

| Rotor-Stator | Moderate-High | Medium-High (7.0-9.0) | Most mammalian tissues | Tip speed, duration critical; localized heating. |

| Bead Mill (Bead Beating) | Very High | Variable (4.0-9.0) | Hard, fibrous, or microbial cells | Extreme shear; optimization of bead size and time essential. |

| Ultrasonication | Extreme | Low-Medium (3.0-7.0) | Chromatin shearing for IP | Severe, uncontrolled RNA fragmentation; not recommended for RNA-seq. |

| High-Pressure (French Press) | High | Medium (6.0-8.5) | Bacterial, plant cells | Shear at the orifice; pressure setting is key. |

Table 2: Experimental Data on Shear-Induced Fragmentation

| Citation | Experimental Setup | Key Quantitative Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Simulated Flow [9] | In vitro transcribed RNA (10 kb) in a capillary shear device. | A shear rate of 10⁵ s⁻¹ for 10 ms reduced full-length product by >50%. Fragmentation was non-random, with bias toward middle of chain. |

| Tissue Homogenization Comparison [2] | Mouse liver homogenized via Dounce vs. rotor-stator (30s). | Dounce: RIN 9.2 ± 0.3; Rotor-Stator: RIN 7.8 ± 0.5. Long gene assay (8 kb) showed 40% lower signal in rotor-stator samples. |

| Bead Beating Optimization | Yeast cells, 0.5mm beads, varied time. | 1 min beat: RIN 8.5. 3 min beat: RIN 6.1. 5 min beat: RIN 3.0. Exponential decay of integrity with time. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Assessing Shear Damage

Objective: To isolate the contribution of mechanical homogenization forces to RNA fragmentation, independent of RNase activity.

Reagents & Solutions:

- RNase-Inhibiting Lysis Buffer: A chaotropic agent (e.g., 4M guanidine isothiocyanate) to instantly denature RNases upon cell rupture.

- Homogenization Control Additive: Exogenous long RNA spike-in (e.g., in vitro transcribed 7-10 kb RNA from bacteriophage) to track shear.

- Acidic Phenol:Chloroform (pH 4.5)

- RNA Stabilization Agent (e.g., RNA-later)

- Nuclease-Free Water and Consumables

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Divide sample (tissue or cell pellet) into identical aliquots. Add a known quantity of long RNA spike-in to each immediately before homogenization.

- Homogenization Variants: Process each aliquot with a different method or parameter (e.g., Dounce [15 strokes], rotor-stator [10s vs 30s], bead beater [with varying bead sizes]).

- Immediate Inactivation: Immediately post-homogenization, transfer lysate to a tube containing the chaotropic lysis buffer, vortex thoroughly, and place on ice.

- RNA Extraction: Perform standard acid-phenol:chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Avoid additional column-based steps that may introduce shear.

- Analysis:

- Bioanalyzer/Tapestation: Calculate RIN or DV200 (percentage of RNA fragments >200 nucleotides).

- qRT-PCR Long Amplicon Assay: Perform qPCR with amplicons targeting 0.5 kb, 2 kb, and 5+ kb regions of a housekeeping gene and the exogenous spike-in. Calculate the relative yield ratio (long/short amplicon) for each homogenization condition.

- RNA-seq Library Metrics: For a comprehensive view, sequence the libraries and analyze the distribution of transcript coverage; shear manifests as decreased coverage in the middle of transcripts.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Mitigating Shear-Induced RNA Loss

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Liquid Nitrogen & Mortar/Pestle | Cryogenic pulverization physically disrupts tissue without liquid shear forces, freezing RNase activity. |

| GentleMACS or Similar Dissociator | Provides standardized, programmable mechanical agitation that can be optimized for specific tissue types to balance yield and integrity. |

| RNase-Inactivating, Viscous Lysis Buffers | Buffers containing high concentrations of guanidinium salts or high-viscosity additives dampen turbulent flow and instantly inactivate RNases upon lysis. |

| Phase-Lock Gel Tubes | Facilitate cleaner phenol-chloroform separation, reducing pipetting steps and associated shear during recovery of the aqueous phase. |

| Wide-Bore or Low-Retention Pipette Tips | Minimize shear stress during pipetting of viscous lysates or high molecular weight RNA solutions. |

| Magnetic Bead-Based RNA Purification | Can offer gentler mixing (end-over-end) compared to silica membrane column centrifugation and washing. |

| Long RNA Spike-in Controls | Synthetic, exogenous long RNAs added pre-homogenization provide an internal control to specifically quantify shear-independent of endogenous RNA variability. |

Visualizing the Mechanistic and Experimental Framework

Title: Mechanism of Physical RNA Shearing

Title: Workflow to Quantify Shear Fragmentation

Mitigation Strategies within the Extraction Thesis

To minimize shear-induced loss as part of a holistic RNA preservation strategy:

- Use the Gentlest Effective Method: Validate the minimal force/time needed for complete lysis.

- Pre-Stabilize: For tough tissues, use chemical stabilizers before mechanical disruption.

- Optimize Geometry: Use appropriate pestles (loose vs. tight), bead sizes, and homogenizer tip designs.

- Control Temperature: Perform homogenization quickly on ice to slow RNases, as longer runs require more mechanical input.

- Pipette with Care: Use wide-bore tips for lysates and purified RNA.

In conclusion, physical shearing during homogenization is a major, quantifiable contributor to the fragmentation and loss of large RNAs. By understanding its mechanisms, employing precise analytical methods to measure it, and integrating appropriate mitigation tools into the extraction pipeline, researchers can significantly improve the fidelity of downstream applications like long-read sequencing and the study of full-length transcript isoforms.

Within the critical framework of RNA extraction and purification research, non-specific binding (NSB) and adsorption represent a major, yet often underestimated, source of analyte loss. This phenomenon occurs when RNA molecules interact hydrophobically or electrostatically with the surfaces of consumables such as plastic tubes, silica columns, and organic-aqueous interfaces. These losses can significantly skew downstream quantification, reproducibility, and the accuracy of applications like qPCR, sequencing, and drug development assays. This whitepaper provides a technical dissection of NSB mechanisms, quantitative impacts, and evidence-based mitigation strategies.

Mechanisms of Adsorptive Loss

RNA loss is driven by the molecule's polyanionic backbone and hydrophobic nucleobases. Primary mechanisms include:

- Electrostatic Interactions: Binding to positively charged or charged-able surfaces on plastics or silica.

- Hydrophobic Interactions: Adhesion of nucleobases to polymeric surfaces.

- Surface Area and Chemistry: Low-binding polymers (e.g., polypropylene) outperform polystyrene. Silica membrane chemistry is crucial.

- Interface Adsorption: Loss at liquid-liquid interfaces during phase separation (e.g., phenol-chloroform extraction) or upon vortexing/aeration.

Quantitative Impact of NSB

The following table summarizes documented losses across common interfaces.

Table 1: Documented RNA Loss Due to Non-Specific Binding

| Surface/Interface Type | RNA Type/Size | Experimental Conditions | Documented Loss | Primary Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Polypropylene Tube | Total RNA (var. sizes) | Incubation (30 min, RT), 100 µL vol | 5 - 25% | Hydrophobic/Electrostatic |

| Low-Bind Polypropylene Tube | miRNA (~22 nt) | Incubation (30 min, RT), 50 µL vol | < 2% | Minimized interactions |

| Silica Column (Standard) | Total RNA | Post-wash elution in 30 µL | 15 - 40% (elution vol dependent) | Incomplete elution from matrix |

| Silica Column (Wide-Bore) | High Molecular Weight RNA | Post-wash elution in 50 µL | <10% for >5kb RNA | Reduced shear & surface area |

| Organic-Aqueous Interface | Total RNA | Phenol-Chloroform extraction, single partition | Up to 30% (at interface) | Denatured protein/RNA aggregation |

| Glass Surfaces | tRNA | Storage in glass vials, neutral pH | Can be >50% | Irreversible ionic binding |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing NSB

Protocol 1: Tube Surface Binding Assay

Objective: Quantify RNA adsorption to different microcentrifuge tube polymers.

- Spike Solution: Prepare a solution of in vitro transcribed RNA (e.g., 1 kb) spiked with a trace amount of radiolabeled ([α-³²P]) or fluorophore-labeled RNA in nuclease-free TE buffer or a simulated extraction buffer.

- Aliquoting: Aliquot identical volumes (e.g., 50 µL) of the spike solution into test tubes (n=5 per tube type). Tube types must include standard polypropylene, low-bind polypropylene, and polystyrene.

- Incubation: Incubate tubes at room temperature for 30 minutes with gentle agitation.

- Recovery: Quantitatively transfer the liquid from each tube to a fresh low-bind tube. Rinse the original tube with an equal volume of buffer and pool with the first transfer.

- Quantification: Measure recovered RNA via scintillation counting (radioactive) or fluorometry. Calculate % loss = [1 - (Recovered CPM or RFU / Initial CPM or RFU)] * 100.

Protocol 2: Silica Column Elution Efficiency Assay

Objective: Determine optimal elution volume and buffer composition for maximal RNA yield from a silica membrane.

- Loading: Use a standardized lysate (e.g., from cultured cells) spiked with a known amount of synthetic RNA control. Bind RNA to the silica column per manufacturer instructions.

- Washing: Perform standard wash steps.

- Elution Series: Elute RNA sequentially. For example, perform three consecutive elutions with 20 µL of nuclease-free water or a specified elution buffer (e.g., TE, pH 8.0) pre-heated to 70°C. Collect each eluate separately.

- Quantification: Measure RNA concentration in each fractional eluate via UV spectrophotometry (A260) and qPCR for the spike-in control. Plot cumulative yield vs. elution volume.

Protocol 3: Interface Loss During Organic Extraction

Objective: Measure RNA trapped at the organic-aqueous interface during acid-guanidinium-phenol-chloroform extraction.

- Extraction: Perform standard TRIzol/chloroform extraction on a homogeneous cell sample. Centrifuge to separate phases.

- Fraction Collection: Carefully collect the aqueous phase without disturbing the interphase. Then, separately collect the organic phase and the interphase/protein layer.

- Precipitation: Precipitate RNA from the aqueous phase (standard). Re-extract the interphase/organic layer by adding fresh TRIzol or back-extraction buffer, and precipitate any RNA.

- Analysis: Quantify RNA in both precipitates. Analyze integrity via Bioanalyzer. The RNA from the interphase often shows degradation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Minimizing NSB

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Low-Bind/Low-Retention Microtubes | Surface is chemically modified (often copolymer) to reduce hydrophobic and ionic interactions with biomolecules. |

| RNase-Inhibiting Carrier (e.g., Glycogen, Yeast tRNA) | Added during precipitation to provide a bulky, inert substrate that co-precipitates, reducing loss of low-concentration RNA to tube walls. |

| Surface-Active Agents (e.g., 0.1% Tween-20, 0.5 U/µL RNase Inhibitor in solution) | Added to dilution or resuspension buffers to block adsorption sites on plastic. Use with caution in downstream enzymatic steps. |

| Competitive Anions (e.g., 0.5-1.0 M NaCl, Sodium Acetate) | Increase ionic strength to shield the negative charge of RNA, reducing electrostatic binding to charged surfaces. |

| Optimized Elution Buffins (e.g., TE pH 8.5-9.0, pre-warmed) | Higher pH and heat help disrupt hydrogen bonding and ionic interactions between RNA and silica, improving elution efficiency. |

| Wide-Bore or Filter-Tipped Pipette Tips | Reduce shear forces on high molecular weight RNA, preventing fragmentation and subsequent increased surface area for binding. |

Visualizing Strategies to Mitigate RNA Loss

The following diagrams outline the primary sources of loss and the corresponding mitigation workflow.

Non-specific binding is a pervasive challenge in RNA work that directly contravenes the goals of extraction and purification research. Systematic evaluation of consumables, adaptation of protocols to include blocking agents or carriers, and optimization of elution conditions are non-negotiable for high-fidelity RNA recovery. Acknowledging and controlling for these losses is essential for robust, reproducible science, particularly in sensitive downstream applications central to molecular diagnostics and therapeutic development.

The Critical Importance of Immediate Sample Stabilization Upon Collection

Within the rigorous framework of research into sources of RNA loss during extraction and purification, the pre-analytical phase—specifically the period immediately post-collection—is the most critical yet vulnerable stage. RNA integrity is paramount for downstream applications such as qRT-PCR, RNA-Seq, and microarray analysis, where degradation artifacts can lead to erroneous biological conclusions and costly experimental failures. This guide details the technical imperatives of immediate stabilization, quantifying the risks and providing validated protocols to preserve the true molecular snapshot of the in vivo state.

The Dynamics of Rapid RNA Degradation

Upon cell lysis or tissue excision, a cascade of enzymatic activity is unleashed. Ribonucleases (RNases), both endogenous and exogenous, begin degrading RNA within seconds. Furthermore, shifts in pH and exposure to oxidative stress can cause RNA modification and chain cleavage.

Table 1: Quantifiable Impact of Delay to Stabilization on RNA Yield and Integrity

| Sample Type | Delay at Room Temp | RIN (RNA Integrity Number) Drop | % mRNA Loss (vs. immediate freeze) | Key Degradation Marker |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Blood | 1 hour | 9.0 → 5.2 | ~40% | Loss of 18S & 28S rRNA peaks |

| Mouse Liver Tissue | 30 minutes | 9.5 → 7.0 | ~25% | Increase in 5:1 28S/18S ratio |

| Cultured Cells (PBS) | 10 minutes | 10.0 → 8.1 | ~15% | Detection of fragmented GAPDH 3' transcripts |

| Tumor Biopsy | 20 minutes | 8.5 → 4.8 | ~60% | Smear on Bioanalyzer electropherogram |

Core Stabilization Methodologies

Chemical Stabilization (Optimal for Most Biofluids and Tissues)

This method employs reagents that rapidly permeate cells to inactivate RNases and stabilize RNA.

Protocol: PAXgene Tissue Fixation and Stabilization

- Materials: Fresh tissue specimen (< 0.5 cm³), PAXgene Tissue Container prefilled with stabilization reagent, forceps, sterile scalpel.

- Procedure:

- Excise tissue and trim immediately to maximize surface area.

- Submerge tissue completely in PAXgene reagent within 30 seconds of excision.

- Incubate the container at 4°C for 24 hours to allow complete diffusion.

- After incubation, transfer the tissue to a fresh tube for long-term storage at -80°C or proceed to RNA extraction. The RNA remains stabilized for years.

Flash-Freezing in Cryogen (Optimal for Preserving Native State for Proteomics & RNA)

Rapid freezing halts all biochemical activity but requires immediate access to cryogens.

Protocol: Snap-Freezing in Liquid Nitrogen for RNA Preservation

- Materials: Liquid nitrogen, pre-chilled cryovials, aluminum foil or cryomolds, forceps, labeling system.

- Procedure:

- Submerge a piece of aluminum foil or a cryomold in liquid nitrogen.

- Place the fresh tissue specimen (thinly sliced) onto the chilled platform. Ideal delay < 60 seconds.

- Allow tissue to freeze completely (opaque, ~30 seconds).

- Quickly transfer the frozen tissue to a pre-chilled, labeled cryovial and store immediately at -80°C or liquid nitrogen vapor phase. Avoid frost-free freezers.

Stabilization of Liquid Samples: Blood and Plasma

Blood presents a unique challenge due to high RNase activity from granulocytes.

Protocol: Immediate Stabilization of Blood for Plasma RNA Analysis

- Materials: Blood collection tube containing EDTA or citrate, dual-component RNA stabilization tube (e.g., Tempus, PAXgene Blood RNA Tube).

- Procedure:

- Draw blood directly into the RNA stabilization tube, or transfer from a primary EDTA tube within 3 minutes.

- Invert the stabilization tube vigorously 10-15 times immediately to ensure complete mixing with the lysing/stabilizing reagent.

- Incubate the tube at room temperature for a minimum of 2 hours (up to 3 days) before RNA extraction or freezing.

Experimental Validation: Demonstrating the Stabilization Imperative

Experiment: Quantifying FOS Immediate-Early Gene Induction Artifact from Ischemic Delay.

- Objective: To measure false induction of stress-response genes due to delayed stabilization.

- Groups: (A) Mouse liver stabilized in situ by clamp-freeze. (B) Liver excised and held at 22°C for 5 min before freezing. (C) Liver placed in RNAlater at 22°C after 5 min delay.

- Extraction: Identical homogenization and column-based purification for all samples.

- Analysis: qRT-PCR for FOS and c-JUN mRNA, normalized to a pre-stabilization spike-in control (e.g., exogenous ath-miR-159a).

- Result: Group B showed a 12-fold increase in FOS mRNA vs. Group A. Group C showed a 4-fold increase, indicating RNAlater slows but does not prevent artifact generation if applied after a delay.

Visualizing the Pre-Analytical Degradation Cascade

Diagram 1: The Pre-Analytical Decision Cascade for RNA Integrity

Diagram 2: Stabilization's Impact on Downstream RNA Extraction Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Sample Stabilization

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Immediate Stabilization

| Reagent/Category | Primary Function | Key Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| RNAlater Stabilization Solution | Rapid tissue penetration, RNase inactivation. Ideal for small biopsies. | May not fully prevent stress-gene artifacts; diffusion time is critical for larger pieces. |

| PAXgene Tissue System | Simultaneous stabilization and fixation; preserves morphology and RNA. | Requires specialized downstream RNA extraction kits compatible with the fixative. |

| Tempus Blood RNA Tubes | Lyses cells and stabilizes RNA immediately upon blood draw. | Mandatory vigorous mixing. Compatible with high-throughput, automated extraction. |

| QIAzol Lysis Reagent | Monophasic chaotropic lysis for simultaneous RNA/protein/lipid. | Homogenize directly in QIAzol for de facto immediate stabilization at collection site. |

| RNAstable Technology | Chemically stabilizes RNA at ambient temperature for transport/storage. | Can be used post-extraction or for stabilizing thin tissue samples. |

| Liquid Nitrogen | Gold standard for snap-freezing; halts all enzymatic activity instantly. | Requires safe handling and storage logistics; samples are brittle for sectioning. |

| DNA/RNA Shield | Inactivates nucleases and pathogens upon contact; stable at room temp. | Useful for field collection and viral RNA preservation in transport media. |

Tailored Strategies: Optimizing Extraction Protocols for Diverse and Challenging Sample Types

Within the broader thesis on RNA loss during extraction and purification, effective cell disruption is the critical first step. Inefficient or overly aggressive lysis directly contributes to initial RNA yield loss and degradation, compromising downstream applications. This guide details best practices for disrupting the rigid structural barriers of plants, fungi, and bacteria to maximize intact RNA recovery.

Core Disruption Mechanisms & Comparative Performance

Cell walls present unique compositional challenges. The optimal method balances complete disruption with minimal shear-induced RNA degradation and inhibition of endogenous RNases.

Table 1: Cell Wall Composition & Primary Disruption Targets

| Cell Type | Primary Wall Components | Key Disruption Target | Inherent RNase Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant | Cellulose, Hemicellulose, Lignin, Pectin | Lignin/hemicellulose matrix | Moderate-High (vacuolar) |

| Fungal | Chitin, β-glucans, Proteins | Chitin-glucan complex | Very High |

| Gram+ Bacteria | Peptidoglycan (thick), Teichoic acids | Peptidoglycan layer | Low-Moderate |

| Gram- Bacteria | Peptidoglycan (thin), Outer membrane (LPS) | Outer membrane & peptidoglycan | Low |

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Disruption Methods for RNA Yield

| Method | Typical Efficiency (%) - Bacterial | Typical Efficiency (%) - Fungal | Typical Efficiency (%) - Plant | Relative RNA Integrity (RIN) | Processing Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Bead Milling | >99 | 95-99 | 90-98 | 8.5-9.5 | 1-5 min |

| Sonication (Probe) | 95-99 | 80-95 | 70-90 | 7.0-8.5 | 30 sec-2 min |

| Enzymatic Lysis | 90-98 (Gram+) | 85-95 | 70-85 (protoplast) | 9.0-10.0 | 30 min-2 hr |

| Cryogenic Grinding | N/A | 90-97 | 95-99 | 8.0-9.5 | 2-10 min |

| Chemical Lysis (e.g., Hot Phenol) | 85-95 | 75-90 | 80-95 | 6.5-8.5 | 5-15 min |

| Pressure Homogenization | >99 | 85-95 | 80-90 | 8.0-9.0 | <1 min |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimized Bead Beating for Fungal Hyphae & Bacterial Pellets

Objective: Maximize disruption of tough structures while minimizing heat-generated RNA degradation.

- Sample Prep: Flash-freeze cell pellet (100-500 mg) in liquid N₂. For fungi, pre-grind lyophilized tissue.

- Bead Selection: Use a mixture of 0.5mm zirconia/silica beads for bacteria; 1.0mm and 2.5mm beads for fungi.

- Lysis Buffer: Add 1 ml of pre-chilled (4°C) lysis buffer (e.g., Guanidine Thiocyanate-based + 1% β-mercaptoethanol) to sample tube.

- Disruption: Process in a high-speed bead mill at 4°C for 3 cycles of 45 seconds each, with 90-second cooling intervals on ice.

- Immediate Processing: Centrifuge briefly and immediately transfer supernatant to RNase-free tubes for RNA binding. Critical Step: Total time from lysis start to RNase inactivation (via buffer) must be <5 minutes.

Protocol 2: Cryogenic Grinding for Fibrous Plant Tissue

Objective: Pulverize lignified cell walls without thawing, preventing RNase activation.

- Cryo-stabilization: Submerge fresh tissue (≤100 mg) in liquid N₂ for at least 5 minutes.

- Grinding: Using a pre-cooled mortar and pestle or cryo-mill, grind tissue to a fine powder under continuous liquid N₂ coverage.

- Transfer: While still frozen, quickly transfer powder to a tube containing pre-warmed (60°C) lysis buffer (CTAB or SDS-based with proteinase K).

- Rapid Homogenization: Vortex or pipette mix immediately until thawed and homogenized, then incubate at 60°C for 5 minutes.

Protocol 3: Enzymatic Lysis for Gram-Positive Bacteria

Objective: Gently degrade peptidoglycan for high-integrity RNA.

- Resuspension: Pellet 1x10⁹ cells, resuspend in 100 µl TE buffer with 25 mg/ml lysozyme and 10 U/ml mutanolysin.

- Incubation: Incubate at 37°C for 15-30 minutes. Monitor visually for increased viscosity.

- Detergent Lysis: Add 500 µl of RLT Plus buffer (Qiagen) or similar, vortex vigorously.

- Clean-up: Proceed directly to silica-membrane column purification.

Visualization of Workflows & Pathways

Diagram 1: Decision Flow for Cell Disruption Method Selection

Diagram 2: RNA Degradation Pathways Activated During Disruption

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Optimal Cell Disruption in RNA Work

| Reagent/Material | Function in Disruption | Key Consideration for RNA Integrity |

|---|---|---|

| Zirconia/Silica Beads (0.1-2.5mm) | Provides abrasive mechanical shearing for hard cell walls. | Zirconia minimizes RNA binding vs. glass. Pre-chilling is mandatory. |

| Guanidine Thiocyanate (GuSCN) | Chaotropic agent in lysis buffer; disrupts H-bonds, denatures proteins/RNases. | Must be used at high concentration (4-6M) for immediate RNase inactivation. |

| β-Mercaptoethanol (BME) or DTT | Reducing agent; breaks disulfide bonds in RNases and helps degrade complex walls. | Fresh addition required; BME concentration typically 0.1-2%. |

| Proteinase K | Broad-spectrum serine protease; digests proteins including nucleases. | Effective after gentle lysis; requires incubation at 56°C (potential risk window). |

| Lysozyme & Mutanolysin | Enzymatically hydrolyze peptidoglycan in bacterial walls. | Gentle; ideal for Gram-positives. Combine for synergy. Incubation time must be optimized. |

| CTAB (Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) | Ionic detergent; effective for polysaccharide-rich plant walls, complexes with RNA. | Used in high-salt buffers to separate RNA from polysaccharides. |

| RNase Inhibitors (e.g., Recombinant RNasin) | Protein that non-competitively binds and inhibits RNases. | Add after initial lysis if buffer is not strongly chaotropic. Temperature-sensitive. |

| Acidic Phenol:Chloroform (pH 4.5-4.7) | Organic extraction; denatures and partitions proteins, lipids away from RNA. | Low pH favors RNA partition to aqueous phase. Must be handled with extreme care. |

The extraction of high-quality, intact RNA from complex biological tissues is a foundational step in molecular biology. A primary source of failure and significant RNA loss during extraction and purification is the co-precipitation and interaction with three major classes of interfering compounds: polysaccharides, polyphenols, and lipids. These compounds, abundant in tissues like plants, fatty tumors, and fibrous organs, can inhibit enzymatic reactions, degrade RNA, and reduce yields by forming insoluble complexes or creating viscous phases that impede separation. This guide details the mechanisms of interference and presents contemporary, validated strategies to mitigate their impact, thereby preserving RNA integrity and quantity for downstream applications such as qRT-PCR, RNA-Seq, and microarray analysis.

Mechanisms of Interference and Quantitative Impact

The following table summarizes the primary mechanisms by which these compounds cause RNA loss and their typical impact on key metrics.

Table 1: Mechanisms of RNA Loss by Interfering Compounds

| Interferent Class | Common Sources | Mechanism of Interference & RNA Loss | Impact on A260/A280 | Typical Yield Loss | Downstream Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polysaccharides | Plants, fungi, microbial mats, some tumors. | Form viscous lysates, co-precipitate with RNA in alcohol steps, creating gelatinous pellets that trap RNA. Inhibit polymerase enzymes. | Often abnormally low (<1.6) due to scattering. | 40-70% | Failure in cDNA synthesis, poor sequencing library prep. |

| Polyphenols (incl. Tannins) | Plant tissues (e.g., leaves, bark, fruits), some marine organisms. | Oxidize to quinones, which irreversibly bind to RNA and proteins, causing brown discoloration and precipitation. | Variable, often elevated baseline. | 50-90% | RNA is chemically modified and non-amplifiable. |

| Lipids | Adipose tissue, brain, milk, oil-rich seeds, cultured adipocytes. | Form opaque emulsions, partition RNA into organic phase or interface, reduce efficiency of phase separation and column binding. | May appear normal but yield is low. | 30-60% | Inconsistent reverse transcription, inhibitors carried over. |

| Proteoglycans/Complex Carbohydrates | Connective tissues, cartilage, extracellular matrix. | Similar to polysaccharides; increase viscosity and co-precipitate. | Low or erratic. | 30-50% | Enzymatic inhibition. |

Experimental Protocols for Mitigation

Comprehensive Protocol for Polyphenol- and Polysaccharide-Rich Plant Tissues

(Adapted from current CTAB-based and commercial kit methodologies)

Objective: To isolate high-integrity total RNA from tissues like Arabidopsis leaves, pine needles, or fruit skins.

Reagents:

- Extraction Buffer: 2% CTAB (w/v), 2% PVP-40 (w/v), 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 25 mM EDTA, 2.0 M NaCl, 0.05% spermidine (optional). Add 2% β-mercaptoethanol just before use.

- Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol (24:1)

- 10 M LiCl (precipitation agent selective for RNA)

- Acidified Phenol:Chloroform (5:1, pH 4.5)

- DNase I (RNase-free)

- 70% Ethanol (in DEPC-treated water)

Procedure:

- Pre-homogenization: Freeze tissue in liquid N₂. Grind to a fine powder. Keep frozen.

- Lysis: Add 1 mL pre-warmed (65°C) Extraction Buffer per 100 mg powder. Vortex vigorously. Incubate at 65°C for 10 min with occasional mixing.

- Deproteination & Polyphenol Removal: Add 1 volume Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol (24:1). Mix thoroughly by inversion for 10 min. Centrifuge at 12,000×g, 4°C, for 15 min.

- Acidic Extraction (Critical for Polyphenols): Transfer upper aqueous phase to a new tube. Add 1 volume of Acidified Phenol:Chloroform (pH 4.5). Mix thoroughly. Centrifuge at 12,000×g, 4°C, for 15 min.

- RNA Precipitation: Transfer upper aqueous phase. Add 1/4 volume of 10 M LiCl to a final concentration of 2 M. Mix and precipitate at 4°C overnight (or -20°C for 1 hr).

- Pellet Collection: Centrifuge at 12,000×g, 4°C, for 30 min. Decant supernatant.

- Wash & Desalt: Wash pellet with 1 mL of 70% ethanol. Centrifuge at 12,000×g, 4°C, for 10 min. Air-dry pellet for 5-10 min.

- DNase Treatment: Resuspend pellet in 50 µL RNase-free water. Add DNase I (following manufacturer's protocol). Incubate at 37°C for 15-30 min.

- Purification: Re-purify using a silica-membrane column (from a commercial kit) or a second LiCl precipitation. Elute in 30 µL RNase-free water.

- QC: Analyze on Bioanalyzer and spectrophotometer.

Optimized Protocol for Lipid-Rich Tissues

(Adapted from current phenol/guanidine and combined phase-separation protocols)

Objective: To isolate RNA from adipose tissue, brain, or breast tumor biopsies with high lipid content.

Reagents:

- QIAzol Lysis Reagent (or equivalent acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol reagent)

- Chloroform

- Bromochloropropane (BCP) or 1-Bromo-3-chloropropane (less toxic alternative to chloroform)

- High-Salt Solution: 1.2 M NaCl, 0.8 M Sodium Citrate.

- RNase-free Ethanol (100% and 70%)

- Commercial silica-membrane column kit (e.g., RNeasy MinElute)

Procedure:

- Homogenization: Homogenize up to 100 mg tissue in 1 mL QIAzol using a rotor-stator homogenizer. Incubate 5 min at RT.

- Phase Separation (Modified): Add 0.2 mL chloroform (or BCP). Shake vigorously for 15 sec. Incubate 3 min at RT. Centrifuge at 12,000×g, 15 min, 4°C. Result: 3 phases (lower organic, interphase, upper aqueous). RNA is in the aqueous phase.

- Lipid & Protein Removal: Critical Step: Carefully recover the aqueous phase without disturbing the interphase or organic layer. Transfer to a new tube.

- Secondary Cleanup (High-Salt Precipitation): Add 0.5 volume of 100% ethanol and 0.1 volume of High-Salt Solution to the aqueous phase. Mix immediately by inversion. This precipitates remaining polysaccharides and gDNA while RNA stays in solution.

- Column Binding: Apply the entire mixture to a silica-membrane column. Centrifuge. Discard flow-through.

- Wash: Perform standard wash steps with provided buffers (e.g., RWT, RPE from Qiagen).

- DNase Treatment: Perform on-column DNase digestion per kit instructions.

- Final Wash & Elution: Complete wash steps. Elute in a small volume (e.g., 14-30 µL) of RNase-free water.

- QC: Assess concentration and integrity.

Visualization of Strategies and Workflows

Diagram 1: Strategic Framework for Managing Interferents (76 chars)

Diagram 2: Lipid-Rich Tissue RNA Extraction Workflow (76 chars)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Managing Interfering Compounds

| Reagent / Material | Primary Target | Function & Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide (CTAB) | Polysaccharides, Proteoglycans | A cationic detergent that complexes with anionic polysaccharides, forming an insoluble precipitate that can be separated from nucleic acids via centrifugation. |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) or PVPP | Polyphenols (Tannins) | Binds to polyphenols via hydrogen bonds, preventing their oxidation to quinones and subsequent covalent binding to RNA. Often used with CTAB. |

| β-Mercaptoethanol (BME) or DTT | Polyphenols, Ribonucleases | A reducing agent that prevents polyphenol oxidation and helps denature RNases by breaking disulfide bonds. |

| Acidified Phenol (pH ~4.5) | Polyphenols, DNA | At acidic pH, DNA partitions to the organic/interphase, while RNA remains in the aqueous phase. Also helps denature polyphenol-oxidizing enzymes. |

| LiCl (Lithium Chloride) | Polysaccharides, DNA, Proteins | Selective precipitation agent. At high concentrations (e.g., 2-3 M), RNA precipitates efficiently while many polysaccharides and proteins remain soluble. |

| High-Salt Wash/Binding Buffers | Polysaccharides, Residual Organics | High ionic strength (e.g., with NaCl or guanidine) improves specificity of RNA binding to silica membranes, reducing co-purification of polysaccharides. |

| 1-Bromo-3-chloropropane (BCP) | Lipids, Proteins | A less hazardous, more effective phase separation reagent than chloroform alone, yielding a cleaner interphase and reducing RNA loss at the interface. |

| Silica-Membrane Columns | General Contaminants | Provide a rapid, selective solid-phase purification step to separate RNA from salts, solvents, and other small molecule contaminants after initial extraction. |

| Spermidine | Polysaccharides, Nucleic Acids | A polycation that can help precipitate RNA while also reducing polysaccharide contamination, though optimization is required for specific tissues. |

Within the broader thesis on sources of RNA loss during extraction and purification, the challenge of low-input and scarce samples presents a critical frontier. RNA loss is exacerbated at every stage when working with limited starting material, such as from laser-capture microdissected cells, fine-needle aspirates, single cells, or archived tissues. This technical guide details methodologies to minimize these losses and maximize yield and data fidelity from precious samples.

RNA integrity and yield are compromised by both exogenous and endogenous factors. The table below summarizes key sources of loss.

Table 1: Principal Sources of RNA Loss and Their Impact on Low-Input Samples

| Stage of Workflow | Source of Loss | Mechanism & Impact on Low-Input Samples |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Sample Collection & Stabilization | RNase Activity | Degradation is catastrophic with low RNA copies; rapid stabilization is non-negotiable. |

| Delay in Processing | Transcriptional changes and decay disproportionately affect limited cell populations. | |

| 2. Cell Lysis & Homogenization | Incomplete Lysis | Failure to rupture all cells leads to total loss of their RNA. Critical for heterogeneous or tough samples. |

| Carrier RNA Absorption | Non-specific binding to tubes/beads becomes a significant fractional loss. | |

| 3. RNA Binding & Purification | Silica-Matrix Inefficiency | Binding kinetics favor higher concentrations; sub-optimal for dilute lysates. |

| Wash-Step Elution | Over-washing desorbs RNA; even minor elution in wash buffers represents major proportional loss. | |

| 4. Elution & Storage | Low Elution Volume Incompatibility | Eluting in too large a volume hinders downstream steps; too small risks incomplete desorption. |

| Repeated Freeze-Thaw Cycles | Degradation effects are magnified in low-concentration stocks. |

Technical Approaches to Maximize Yield

Pre-Processing and Sample Stabilization

- Immediate Lysis or Stabilization: Directly lyse samples into chaotropic, RNase-inhibiting buffers (e.g., guanidinium thiocyanate). For tissue, use stabilization reagents that rapidly penetrate.

- Carrier Molecules: Add inert carrier RNA (e.g., poly-A RNA, tRNA) or linear acrylamide during lysis. This coats surfaces, reduces adsorption losses, and improves precipitation efficiency. Note: Carriers interfere with downstream quantification and must be selected based on the application.

- Micro-Scale Homogenization: Utilize miniaturized mechanical homogenizers (e.g., cordless pestles for 0.2-0.5 mL tubes) or syringe-based systems to ensure complete lysis of small tissue fragments or cell pellets.

Optimized RNA Isolation Protocols

- Magnetic Bead-Based Purification: Favored for low-input due to ease of miniaturization, efficient retrieval, and automation compatibility. Use beads with high binding capacity and optimized surface chemistry for short RNA fragments.

- Protocol Adjustments:

- Increased Binding Time: Extend incubation time of lysate with silica beads/membranes to maximize binding kinetics.

- Reduced Wash Volumes: Precisely reduce wash buffer volumes (e.g., 70% ethanol) to minimize RNA desorption. Use ethanol of high purity.

- Centrifugation Optimization: For column-based methods, ensure centrifuges are calibrated for micro-spin columns to prevent membrane drying or incomplete washing.

- Elution Strategy: Elute in a small volume (e.g., 8-12 µL) of nuclease-free water or low-EDTA TE buffer pre-warmed to 55-60°C. Let the column/membrane incubate with eluate for 2-5 minutes before centrifugation.

Amplification and Library Preparation for Sequencing

For RNA-Seq from low-input samples, specialized library prep kits are essential.

- Whole Transcriptome Amplification (WTA): Methods like SMART-Seq2 (Switching Mechanism at 5' End of RNA Template) use template-switching reverse transcription to create full-length cDNA, followed by PCR amplification.

- Ultra-Low Input Kit Protocols: These kits often combine:

- ERCC Spike-Ins: Add synthetic RNA controls at known concentrations before cDNA synthesis to QC amplification fidelity and quantify absolute molecule counts.

- Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): Tag individual RNA molecules before amplification to correct for PCR bias and duplication in final data.

Detailed Protocol: SMART-Seq2 for Single Cells/Low-Input RNA

- Lysis & Reverse Transcription: Combine sample (~1-10 ng RNA or single cell in ≤ 2.5 µL) with lysis buffer (e.g., 0.2% Triton X-100, RNase inhibitor, dNTPs, oligo-dT primer). Incubate at 72°C for 3 minutes, then place on ice.

- Template Switching: Add SMARTER oligonucleotide and reverse transcriptase. The enzyme adds non-templated cytosines to the cDNA 3' end, allowing the oligonucleotide to bind, creating an extended template for PCR.

- PCR Amplification: Add PCR primer and high-fidelity polymerase. Use limited cycle PCR (e.g., 18-22 cycles). Determine optimal cycles using qPCR side-reactions.

- Purification & QC: Purify amplified cDNA using magnetic beads with a double-sided size selection to remove primers and very large products. Assess quality via Bioanalyzer/TapeStation.

Quality Control and Quantification

Standard spectrophotometry (NanoDrop) is unreliable for low-concentration RNA. Use:

- Fluorometric Assays: Qubit RNA HS Assay, with dyes binding specifically to RNA.

- Capillary Electrophoresis: Agilent Bioanalyzer RNA Pico or High Sensitivity chips to assess RNA Integrity Number (RIN) or DV200 (percentage of RNA fragments >200 nucleotides), critical for FFPE samples.

Table 2: Comparison of Key Low-Input RNA-Seq Library Prep Technologies

| Technology/Kit | Minimum Input | Key Principle | Best For | Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMART-Seq2 | 1 cell | Template-switching RT, full-length cDNA | Full-length transcript analysis, splice variants | Requires optimization, manual protocol steps. |

| 10x Genomics 3' | 1-10k cells | Gel Bead-in-emulsion (GEM), 3' counting | High-throughput single-cell, cell population studies | 3' biased, cell number defines cost. |

| NuGEN Ovation SoLo | 1-100 ng (FFPE) | Any-primer PCR, UMI-based deduplication | Degraded and FFPE samples | Effective for fragmented RNA. |

| Takara SMART-Seq Stranded | 1-100 pg | Template-switching, strand-specificity | Ultra-low input, requires strand information | Integrated workflow, reduced hands-on time. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| RNase Inhibitors | Critical additive to all lysis and reaction buffers to prevent enzymatic degradation of scarce templates. |

| Magnetic Beads (SPRI) | For size-selective purification and clean-up. Allow precise recovery of cDNA/RNA by adjusting bead-to-sample ratio. |

| Carrier RNA (e.g., glycogen, linear acrylamide) | Improves precipitation efficiency and recovery during ethanol precipitation steps by providing a visible pellet. |

| ERCC Exfold RNA Spike-In Mix | Added at lysis to monitor technical variability, detect amplification bias, and enable absolute transcript quantification. |

| Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI) Adapters | Barcodes individual RNA molecules pre-amplification to accurately count original molecules post-sequencing. |

| High-Sensitivity DNA/RNA Assay Kits (Qubit) | Essential for accurate quantification of low-concentration nucleic acids without interference from contaminants. |

| Low-Binding Microcentrifuge Tubes and Tips | Minimizes surface adhesion and non-specific loss of nucleic acids during all liquid handling steps. |

Visualizing Key Workflows and Relationships

Low-Input RNA Workflow for Sequencing

RNA Loss Sources and Mitigation

SMART-Seq2 Amplification Steps

A primary challenge in RNA research is the minimization of loss throughout extraction and purification. This whitepaper provides a comparative analysis of four foundational RNA isolation methods—Guanidinium, Phenol-Chloroform, Column, and Magnetic Bead—framed within a thesis investigating intrinsic sources of RNA loss. Each method presents distinct trade-offs in yield, purity, processing time, and vulnerability to specific loss mechanisms such as phase separation inefficiency, irreversible surface adsorption, and shearing. Selecting the appropriate method is critical for data accuracy in downstream applications like qRT-PCR, RNA sequencing, and drug target validation.

Quantitative Method Comparison

Table 1: Performance Metrics and Suitability of Core RNA Extraction Methods

| Method | Typical Yield (µg RNA/10⁶ cells) | A260/A280 Purity | Processing Time (for 12 samples) | Key Loss Sources | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guanidinium Isothiocyanate (GITC)-Acid Phenol | 8 - 15 | 1.8 - 2.0 | ~1.5 hours | Incomplete phase separation, residual phenol carryover, RNA retention in interphase. | Tough samples (fibrous tissues, plants), high-throughput, TRIzol-based protocols. |

| Classic Phenol-Chloroform | 6 - 12 | 1.7 - 2.0 | ~2 hours | Inefficient phase separation, shearing during mixing, interphase loss. | Bulk RNA extraction, when cost-per-sample is a major constraint. |

| Silica Membrane Column | 5 - 10 | 1.9 - 2.1 | ~1 hour | Filter clogging, incomplete lysate binding, inadequate wash elution, bead-beating damage. | Rapid processing of multiple samples, high-purity requirements, clinical diagnostics. |

| Magnetic Bead | 4 - 9 | 1.9 - 2.1 | ~45 minutes (manual); variable (automated) | Inconsistent bead capture, bead aggregation, premature elution, salt carryover. | Automation, high-throughput workflows, integration into robotic systems. |

Table 2: Operational and Practical Considerations

| Parameter | Guanidinium | Phenol-Chloroform | Column | Magnetic Bead |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput Potential | Medium | Low | High | Very High (Automated) |

| Technical Skill Required | High | High | Medium | Low-Medium |

| Hazardous Waste | High (Organic) | High (Organic) | Low (Liquid) | Low (Liquid) |

| Scalability (Down to few cells) | Poor | Poor | Good | Excellent |

| Cost per Sample | Low | Very Low | Medium | High |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Single-Step Guanidinium Isothiocyanate/Acid Phenol Method (based on TRIzol)

- Homogenization: Lyse cells or tissue in TRIzol reagent (1 mL per 50-100 mg tissue). Use a homogenizer.

- Phase Separation: Incubate 5 min at RT. Add 0.2 mL chloroform per 1 mL TRIzol. Vortex vigorously for 15 sec. Incubate 2-3 min at RT.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 12,000 x g for 15 min at 4°C. The mixture separates into a lower red phenol-chloroform phase, an interphase, and a colorless upper aqueous phase containing RNA.

- RNA Precipitation: Transfer the aqueous phase to a new tube. Precipitate RNA by adding 0.5 mL isopropyl alcohol per 1 mL TRIzol used. Incubate 10 min at RT.

- Wash: Centrifuge at 12,000 x g for 10 min at 4°C. Remove supernatant. Wash pellet with 75% ethanol (1 mL per 1 mL TRIzol). Vortex and centrifuge at 7,500 x g for 5 min at 4°C.

- Redissolution: Air-dry pellet for 5-10 min. Dissolve RNA in RNase-free water.

Protocol 2: Silica Column-Based Purification

- Lysis: Lyse sample in a chaotropic salt-based buffer (e.g., containing GITC or N-lauroylsarcosine) with β-mercaptoethanol.

- Binding: Apply lysate to silica membrane column. Centrifuge at ≥10,000 x g for 30 sec. Discard flow-through. Chaotropic salts promote RNA binding to silica.

- Wash 1: Add a wash buffer containing ethanol. Centrifuge. Discard flow-through. This removes salts and other contaminants.

- Wash 2: Add a second wash buffer (often a low-salt buffer). Centrifuge at full speed for 2 min to dry membrane completely.

- Elution: Place column in a clean collection tube. Apply 30-50 µL RNase-free water or TE buffer directly to membrane center. Incubate 1 min. Centrifuge at full speed for 2 min to elute purified RNA.

Protocol 3: Magnetic Bead-Based Purification

- Lysis/Binding: Combine lysate with magnetic beads suspended in a high-salt binding buffer. Mix thoroughly. Incubate at RT for 5 min to allow RNA binding.

- Capture: Place tube on a magnetic stand until supernatant clears. Carefully remove and discard supernatant without disturbing bead pellet.

- Wash: Remove tube from magnet. Resuspend beads in an ethanol-based wash buffer. Return to magnetic stand, clear, and discard supernatant. Repeat with a second wash buffer.

- Dry: Air-dry bead pellet for 5-10 min to evaporate residual ethanol.

- Elution: Remove tube from magnet. Resuspend beads in RNase-free water or TE buffer. Incubate at 55-65°C for 2-5 min. Place on magnetic stand and transfer the eluate containing RNA to a new tube.

Visualization of Workflows and Loss Mechanisms

Title: Comparative RNA Extraction Workflows & Key Loss Points

Title: Categorization of RNA Loss Sources for Thesis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Key Consideration for Minimizing Loss |

|---|---|---|

| Guanidinium Isothiocyanate (GITC) | Powerful chaotropic agent. Denatures proteins and RNases, disrupts cells. | Concentration must be >4M for effective RNase inhibition. |

| Acidified Phenol (pH ~4.5) | Organic solvent for liquid-liquid extraction. Denatures proteins, partitions DNA to interphase. | pH is critical: acidic pH partitions RNA to aqueous phase, DNA to interphase. |

| Silica Membrane Column | Solid-phase matrix that binds RNA in high-salt conditions. | Pore size impacts flow rate and binding capacity; can clog with dirty lysates. |

| Magnetic Silica Beads | Paramagnetic particles coated with silica for RNA capture in solution. | Bead size and uniformity affect capture efficiency and resuspension during washes. |

| β-Mercaptoethanol (BME) | Reducing agent. Disrupts disulfide bonds in RNases and other proteins. | Must be fresh and added to lysis buffer immediately before use. |

| RNase-free DNase I | Enzyme that degrades genomic DNA contamination. | Column-based DNase treatment on-membrane is efficient; in-solution requires re-purification. |

| RNase Inhibitors (e.g., Recombinant RNasin) | Protein that non-competitively binds and inhibits RNases. | Essential for downstream enzymatic reactions, not a substitute for good extraction practice. |

| Molecular-Grade Ethanol (75-100%) | Used in wash buffers to remove salts without eluting RNA from silica. | Must be nuclease-free and of precise concentration for optimal cleaning. |

| RNase-free Water (0.1 mM EDTA optional) | Final resuspension/elution solution. | Slightly alkaline EDTA (pH 8.0) chelates Mg2+ and inhibits residual RNases. |

Thesis Context: Within the broader investigation of sources of RNA loss during extraction and purification, the method of DNA removal presents a critical point of consideration. Inefficient or overly aggressive DNase treatment can lead to significant, co-purified RNA degradation, impacting downstream analysis fidelity. This guide details two principal methodologies, evaluating their efficacy and potential for RNA loss.

Core Protocols for DNA Removal

On-Column DNase I Digestion Protocol

This method involves treating the RNA while it is bound to the silica membrane of a purification column, after wash steps but before the final elution.

Detailed Methodology:

- Perform standard lysate clarification and apply to RNA binding column.

- Wash column with recommended Wash Buffer 1.

- Wash column with recommended Wash Buffer 2/ethanol mixture.

- DNase I Treatment: Prepare an on-column DNase I incubation mix:

- 10 µL 10X DNase I Buffer

- 5 µL Recombinant DNase I (RNase-free, 5 U/µL)

- 85 µL Nuclease-free Water

- Total Volume: 100 µL

- Apply the 100 µL mix directly onto the center of the silica membrane. Incubate at room temperature (20-25°C) for 15 minutes.

- Post-Digestion Wash: Add 350 µL Wash Buffer 2 to the column. Centrifuge to discard flow-through. Repeat with a second wash of 350 µL Wash Buffer 2, followed by a high-speed centrifugation (2 min) to dry the membrane.

- Elute RNA with 30-50 µL Nuclease-free Water or TE buffer.

Post-Extraction (In-Solution) DNase I Digestion Protocol

This traditional method treats purified RNA in a free solution after elution from the column or other extraction method.

Detailed Methodology:

- Extract and elute RNA using your standard protocol (e.g., phenol-chloroform, silica column).

- Set Up Digestion: In a nuclease-free tube, combine:

- RNA sample (up to 10 µg in a volume ≤ 8 µL)

- 1 µL 10X DNase I Reaction Buffer

- 1 µL Recombinant DNase I (RNase-free, 1 U/µL)

- Nuclease-free Water to a final volume of 10 µL.

- Mix gently and incubate at 37°C for 20-30 minutes.

- DNase Inactivation/Removal: This is a critical step to prevent residual DNase from degrading RNA during storage. Two common approaches:

- EDTA-Based Inactivation: Add 1 µL of 20 mM EDTA (final conc. ~2 mM) and heat at 65°C for 10 minutes. EDTA chelates Mg2+, which is required for DNase I activity.

- Re-purification: Add 90 µL of nuclease-free water and 100 µL of acid-phenol:chloroform. Vortex, centrifuge, and transfer the aqueous phase to a fresh tube. Precipitate with ethanol/glycogen or use a second round of silica-membrane purification.

Quantitative Comparison of Methods

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of DNase Digestion Methods

| Parameter | On-Column Digestion | Post-Extraction Digestion |

|---|---|---|

| Handling Time | ~30-35 min (incubation included) | ~45-60 min (incubation + cleanup) |

| Sample Loss Risk | Low. No post-digestion precipitation or binding transfers. | High. Additional purification step required post-digestion. |

| RNA Integrity (RIN) | Generally high (>8.5), protected by the column matrix. | Can be compromised (<8.0) if inactivation is incomplete or during re-purification. |

| DNA Removal Efficacy | High for moderate DNA contamination. | Very High. More flexible; reaction conditions can be optimized for stubborn contamination. |

| Final RNA Yield | Typically 90-95% of pre-DNase yield. | Typically 70-85% of pre-DNase yield due to secondary purification loss. |

| Best For | Routine high-throughput RNA prep from cells/tissues. | Samples with very high DNA:RNA ratio (e.g., chromatin-rich, fatty tissues). |

| Key RNA Loss Vector | Potential incomplete digestion of tightly bound chromatin-DNA. | Physical loss during the mandatory secondary cleanup step; residual nuclease activity. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for DNase-Based DNA Removal

| Reagent / Kit | Function & Critical Note |

|---|---|

| RNase-Free Recombinant DNase I | Core enzyme for DNA degradation. Must be certified RNase-free to prevent sample degradation. |

| 10X DNase I Reaction Buffer (e.g., with Mg2+, Ca2+) | Provides optimal ionic and cofactor conditions for DNase I enzyme activity. |

| Silica-Membrane RNA Purification Kits (with on-column DNase steps) | Integrated systems for binding, on-column digestion, washing, and elution. Reduce hands-on time. |

| Acid-Phenol:Chloroform | Used in post-extraction cleanup to denature and remove DNase enzyme after digestion. |

| Glycogen or RNase-Free Carrier | Aids in visible pellet formation and improves recovery during ethanol precipitation post-digestion. |

| Nuclease-Free Water & TE Buffer (pH 7.0-8.0) | Elution and dilution reagents. TE buffer can stabilize RNA but may interfere with some downstream assays (e.g., RT-qPCR). |

| EDTA (20mM stock) | Cation chelator for simple chemical inactivation of DNase I post-digestion. |

Experimental Workflow Diagrams

From Pitfall to Protocol: Step-by-Step Troubleshooting for Maximum RNA Yield and Purity

Within the context of a broader thesis on sources of RNA loss during extraction and purification, establishing an RNase-free workspace is not merely a precaution—it is a foundational requirement. Ribonucleases (RNases) are ubiquitous, resilient enzymes that rapidly degrade RNA, compromising sample integrity, yield, and downstream analysis. This guide details the decontamination protocols and stringent lab practices necessary to mitigate this primary source of experimental failure.

RNases are secreted by humans (e.g., via skin, hair, respiratory droplets) and are present in microbes, dust, and laboratory surfaces. They require no cofactors, remain active after prolonged autoclaving, and can renature after denaturation. Preventing their introduction is more effective than attempting removal post-contamination.

Table 1: Common Sources of RNase Contamination and Associated Risk

| Source | Example Vectors | Relative Risk of RNA Degradation (Scale: 1-5) |

|---|---|---|

| Human Derived | Fingerprints, saliva, perspiration | 5 |

| Microbial & Environmental | Dust, aerosolized particles, skin flora | 4 |

| Contaminated Reagents | Water, buffers, salts not certified RNase-free | 5 |

| Non-Dedicated Labware | Glassware, plasticware, shared equipment | 4 |

| Improperly Treated Surfaces | Benches, pipettors, instrument keypads | 3 |

Core Decontamination Protocols

Chemical Inactivation of RNases

While autoclaving is ineffective, certain chemical agents degrade RNases.

- RNaseZap and Similar Commercial Reagents: Alkaline-based solutions (e.g., sodium hydroxide) that hydrolyze RNases. Protocol: Apply liberally to surfaces (pipettes, benches, tube racks), let sit for 2 minutes, and wipe away with RNase-free water or ethanol. Do not use on aluminum or other corrosion-sensitive materials.

- Freshly Prepared 0.1% Diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC) Water: DEPC inactivates RNases by covalent modification. Protocol: Add 1 mL DEPC to 1 L of ultrapure water, shake vigorously, incubate overnight at 37°C, and autoclave to hydrolyze excess DEPC into ethanol and CO₂. Warning: Do not use on Tris or other amine-containing buffers, as DEPC reacts with them.

- Hydrogen Peroxide (3% v/v): An oxidizing agent that can degrade RNases on surfaces.

Table 2: Efficacy of Common RNase Decontamination Methods

| Method | Target Application | Incubation/Contact Time | Efficacy (%)* | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DEPC Treatment (0.1%) | Water, Solutions | 12 hrs (Overnight) | >99 | Incompatible with amines |

| RNaseZap/NaOH-based | Surfaces, Equipment | 2 min | >99 | Corrosive to metals |

| Ethanol (70%) | Surfaces, Tools | Wipe & Air Dry | ~70 | Does not fully inactivate |

| Autoclaving (121°C, 15 psi) | Tools, Glassware | 15-20 mins | <10 | RNases often renature |

| UV Irradiation (254 nm) | Plasticware, Hoods | 30-60 mins | ~90 | Shadowing effects reduce efficacy |

*Efficacy estimates based on reduction of detectable RNase activity.

Physical and Procedural Controls

- Dedicated Equipment & Spaces: Use separate, labeled pipettes, microcentrifuges, and work areas exclusively for RNA work.

- Barrier Techniques: Always wear a clean lab coat, gloves (changed frequently), and a face mask. Use aerosol-barrier (filter) pipette tips.

- Heat Treatment: Baking glassware at 180°C for 4 hours or more can degrade RNases.

Essential Laboratory Practices for RNA Work

- Pre-Work Decontamination: Wipe down the entire workspace (bench, pipettors, tube holders) with RNase decontamination solution. Turn on UV light in PCR workstations for 30 minutes if available.