From Bulk to Spatial Context: Validating and Integrating Transcriptomics Data for Advanced Biomedical Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to validate and integrate bulk RNA-seq data with cutting-edge spatial transcriptomics (ST) technologies.

From Bulk to Spatial Context: Validating and Integrating Transcriptomics Data for Advanced Biomedical Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to validate and integrate bulk RNA-seq data with cutting-edge spatial transcriptomics (ST) technologies. We explore the foundational principles that distinguish ST from bulk sequencing, highlighting its unique ability to preserve spatial context and reveal cellular heterogeneity within intact tissues. The review details methodological approaches for cross-platform validation, including deconvolution algorithms and benchmarking strategies for popular commercial platforms like 10X Visium, Xenium, CosMx, and MERFISH. We address critical troubleshooting and optimization considerations for experimental design, sample preparation, and data analysis. Finally, we present a rigorous comparative analysis of ST performance against bulk and single-cell RNA-seq, establishing best practices for validation to ensure biological fidelity and translational relevance in cancer research, immunology, and developmental biology.

Beyond Bulk Sequencing: Unlocking Tissue Architecture with Spatial Transcriptomics

- The Core Limitation: Bulk RNA-seq provides only an average gene expression profile from a mixed cell population, obscuring cellular heterogeneity and spatial context crucial for understanding tissue function and disease mechanisms [1] [2] [3].

- The Spatial Solution: Spatial transcriptomics technologies overcome this by mapping gene expression within intact tissue architecture, preserving location information that is fundamental to biological function [4].

- Validation Context: This comparison examines how spatial transcriptomics validates and extends findings from bulk RNA-seq, providing critical spatial validation for transcriptional profiles discovered through bulk analysis.

Bulk RNA sequencing has served as a foundational tool in transcriptomics, providing cost-effective, global gene expression profiles that have advanced our understanding of cancer biology, developmental processes, and disease mechanisms [1] [5]. This technology measures the average expression levels of thousands of genes across a population of cells, enabling discoveries of differentially expressed genes, gene fusions, splicing variants, and mutations [1]. However, this "averaging" effect represents a fundamental constraint that masks the intricate cellular heterogeneity within tissues and eliminates the spatial relationships that govern cellular function [2].

The transition from bulk to spatial analysis represents a paradigm shift in transcriptomics. As Professor Muzz Haniffa explains, "The majority of cells in the body have the same genome... These organs are not a bag of random cells, they are very spatially organised and this organisation is vital for their function" [4]. This spatial organization is particularly critical in complex tissues like tumors, where the tumor microenvironment contains diverse cell populations including various immune cells, stromal cells, and tumor cells themselves, all constantly evolving and communicating through spatial relationships that drive progression, metastasis, and therapy resistance [1].

Technical Comparison: Bulk RNA-seq vs. Spatial Transcriptomics

Fundamental Methodological Differences

Table 1: Core Methodological Differences Between Bulk and Spatial Transcriptomics

| Feature | Bulk RNA-seq | Spatial Transcriptomics |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | None (tissue homogenate) | Single-cell to multi-cellular spots (varies by platform) |

| Input Material | Mixed cell population | Tissue sections preserving architecture |

| Gene Detection | Unbiased whole transcriptome | Targeted panels or whole transcriptome (platform-dependent) |

| Data Output | Gene expression matrix | Gene expression matrix with spatial coordinates |

| Tissue Context | Lost during processing | Preserved with histological imaging |

| Key Applications | Differential expression, fusion detection, biomarker discovery | Spatial cell typing, cell-cell interactions, spatial gene expression patterns |

The "Where's Wally" Analogy for Transcriptomics Technologies

A helpful analogy compares these technologies to the "Where's Wally" (or "Where's Waldo") puzzle books [4]:

- Bulk RNA-seq is like shredding all pages and mixing them together—you can detect all colors present but cannot determine which characters they came from or where they were located.

- Single-cell RNA-seq is like viewing the character reference page—you can identify all characters and their features but don't know their positions in each scene.

- Spatial transcriptomics is like opening the complete book—you can find each character in their precise location within the detailed scenes.

Figure 1: Conceptual analogy comparing transcriptomics technologies using the "Where's Wally" puzzle book framework [4].

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

Detection Sensitivity and Resolution Comparisons

Table 2: Performance Metrics Across Transcriptomics Platforms

| Platform Type | Effective Resolution | Transcripts/Cell Range | Unique Genes/Cell | Tissue Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk RNA-seq | N/A (population average) | N/A (bulk measurement) | Whole transcriptome (~20,000 genes) | Fresh, frozen, or fixed |

| 10X Visium | 55-100 μm spots (multi-cellular) | Varies by tissue type | ~5,000 genes/spot | FFPE, fresh frozen |

| Stereo-seq | 10-20 μm (near single-cell) | Platform-dependent | Platform-dependent | Fresh frozen |

| Imaging-based (Xenium, MERFISH, CosMx) | Single-cell/subcellular | 10-100+ transcripts/cell | Hundreds to thousands (panel-dependent) | FFPE, fresh frozen |

| Slide-seqV2 | 10 μm (single-cell) | Platform-dependent | Platform-dependent | Fresh frozen |

Data compiled from systematic comparisons of sequencing-based [6] and imaging-based [7] spatial transcriptomics platforms.

Platform-Specific Detection Capabilities

Table 3: Imaging-Based Spatial Platform Performance in Tumor Samples

| Platform | Panel Size | Transcripts/Cell | Unique Genes/Cell | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CosMx | 1,000-plex | Highest among platforms | Highest among platforms | Comprehensive panel | Limited field of view |

| MERFISH | 500-plex | Moderate to high | Moderate to high | Whole-tissue coverage | Lower detection in older tissues |

| Xenium (Unimodal) | 339-plex | Lower than CosMx | Lower than CosMx | Whole-tissue coverage | Lower transcripts/cell |

| Xenium (Multimodal) | 339-plex | Lowest among platforms | Lowest among platforms | Morphology integration | Significant signal reduction |

Performance data derived from systematic comparison using FFPE tumor samples [7].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Bulk RNA-seq Workflow

The ENCODE consortium has established standardized bulk RNA-seq processing pipelines that include [8]:

- Library Preparation: mRNA enrichment (poly-A selection) or rRNA depletion, followed by cDNA synthesis and adaptor ligation.

- Sequencing: Typically Illumina platforms, with minimum 50bp read length, 20-30 million aligned reads per replicate.

- Quality Control: Adapter trimming, quality filtering, and spike-in controls (ERCC RNA spike-ins).

- Alignment and Quantification: STAR or TopHat alignment to reference genome, followed by RSEM quantification for gene-level counts.

- Normalization: TPM (transcripts per million) or FPKM (fragments per kilobase per million) normalization for cross-sample comparison.

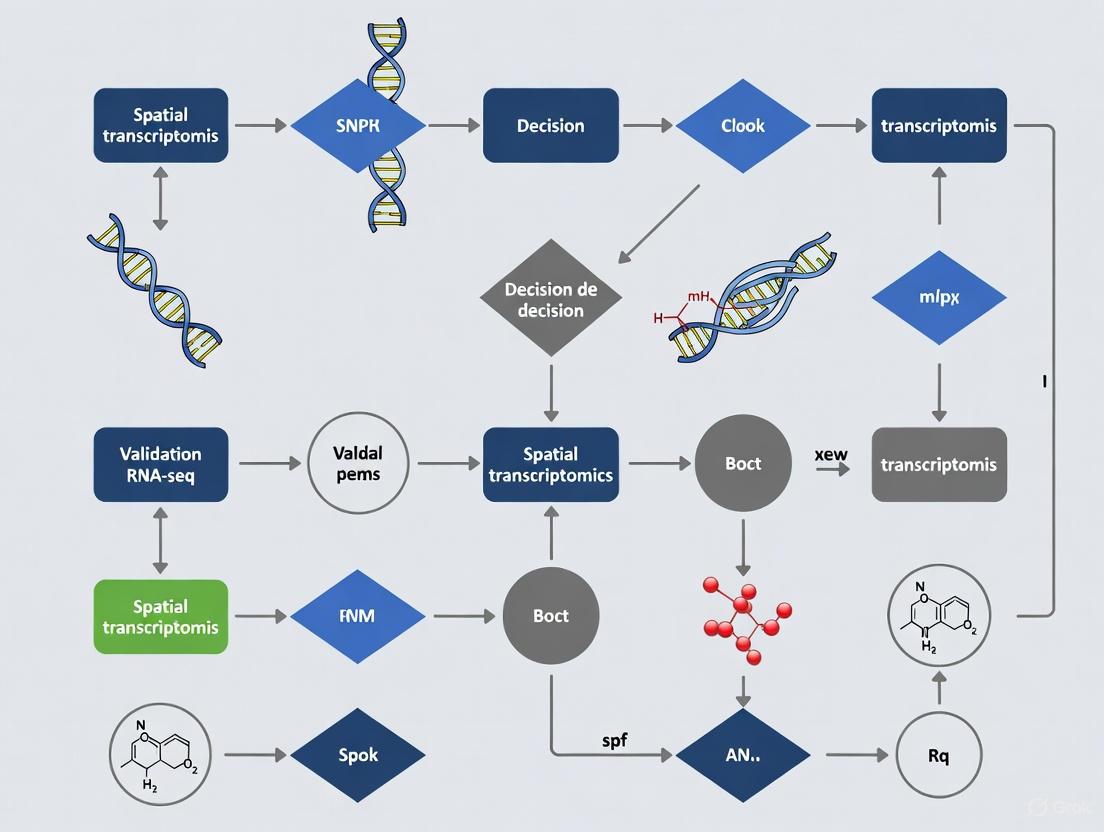

Figure 2: Standard bulk RNA-seq workflow demonstrating where spatial context is lost during tissue homogenization [5] [8].

Spatial Transcriptomics Experimental Workflows

Sequencing-Based Spatial Transcriptomics

Sequencing-based approaches (e.g., 10X Visium, Stereo-seq) utilize [6] [2]:

- Tissue Preparation: Fresh frozen or FFPE tissue sections (5-10 μm thickness) mounted on specialized slides.

- Permeabilization: Optimized treatment to release RNA while preserving tissue morphology.

- Spatial Barcoding: In situ reverse transcription using barcoded oligos with positional coordinates.

- Library Construction: cDNA synthesis, amplification, and sequencing library preparation.

- Sequencing and Alignment: High-throughput sequencing followed by alignment to reference genome.

- Spatial Reconstruction: Mapping sequence reads to spatial coordinates using barcode information.

Imaging-Based Spatial Transcriptomics

Imaging-based approaches (e.g., MERFISH, Xenium, CosMx) employ [2] [7]:

- Probe Design: Gene-specific probes with fluorescent barcodes for multiplexed detection.

- Tissue Hybridization: Probe binding to target RNA in fixed tissue sections.

- Multiplexed Imaging: Multiple rounds of hybridization, imaging, and probe stripping.

- Image Processing: Computational decoding of fluorescent signals to RNA identities.

- Cell Segmentation: Nuclear or membrane staining to define cellular boundaries.

- Spatial Mapping: Assignment of RNA molecules to specific cellular locations.

Figure 3: Spatial transcriptomics workflow demonstrating preservation of tissue architecture throughout the process [2] [4].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for Spatial Transcriptomics

| Category | Specific Products/Platforms | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing-Based Platforms | 10X Genomics Visium, Stereo-seq, Slide-seq | Whole transcriptome spatial mapping | Resolution vs. coverage trade-offs |

| Imaging-Based Platforms | Xenium (10X Genomics), MERFISH (Vizgen), CosMx (NanoString) | Targeted panel spatial imaging | Panel design critical for cell typing |

| Sample Preservation | FFPE, OCT-embedded frozen tissue | Tissue architecture preservation | FFPE compatible with most platforms |

| Cellular Segmentation | DAPI, nuclear stains, membrane markers | Cell boundary definition | Impacts single-cell resolution accuracy |

| Reference Datasets | Single-cell RNA-seq atlases | Cell type annotation | Essential for interpreting spatial data |

| Analysis Tools | Seurat, Squidpy, STUtility, Cell2location | Spatial data analysis | Specialized computational methods required |

Reagent information synthesized from multiple spatial transcriptomics studies [6] [2] [7].

Case Study: Tumor Microenvironment Characterization

Bulk RNA-seq Limitations in Cancer Research

In tumor analysis, bulk RNA-seq averages signals across malignant cells, immune cells, stromal cells, and vascular components, potentially obscuring critical rare cell populations. For example, scRNA-seq studies have revealed rare stem-like cells with treatment-resistance properties and minor cell populations expressing high levels of AXL that developed drug resistance after treatment with RAF or MEK inhibitors in melanoma—populations that would be undetectable by bulk RNA-seq [1].

Spatial Validation Reveals Tumor Organization

Spatial transcriptomics applied to head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) identified partial epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (p-EMT) programs associated with lymph node metastasis, with tumor cells expressing this program specifically located at the invasive front [1]. Similarly, in glioblastoma, colorectal cancer, and HNSCC, spatial technologies have dissected intra-tumor heterogeneity at single-cell resolution, revealing cellular neighborhoods and spatial organization that drive tumorigenesis and treatment resistance [1].

Discussion: Integrating Bulk and Spatial Approaches

While spatial transcriptomics provides unprecedented resolution of tissue organization, bulk RNA-seq remains valuable for hypothesis generation and cost-effective screening. The optimal research approach often involves:

- Discovery Phase: Bulk RNA-seq to identify differentially expressed genes and pathways.

- Validation Phase: Spatial transcriptomics to localize identified targets within tissue context.

- Integration: Computational methods like deconvolution (e.g., DiffFormer) to infer spatial patterns from bulk data [9].

The field continues to evolve rapidly, with emerging solutions addressing current spatial transcriptomics limitations including cost, throughput, and computational challenges. As technologies mature and become more accessible, spatial transcriptomics is poised to become central to translational research and clinical applications, particularly in cancer diagnostics and therapeutic development [2] [4].

Spatial transcriptomics (ST) has emerged as a revolutionary set of technologies that enable researchers to measure gene expression profiles within tissues while preserving their original spatial context. This capability overcomes a fundamental limitation of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), which requires tissue dissociation and thereby loses crucial spatial information about cellular organization and microenvironment interactions [10] [2]. This guide compares the performance of leading commercial ST platforms, with a specific focus on their validation against bulk RNA-seq and single-cell transcriptomics data.

Core Technological Principles

Spatial transcriptomics technologies can be broadly categorized into two main approaches based on their fundamental RNA detection strategies: imaging-based and sequencing-based methodologies [2].

Imaging-Based Spatial Transcriptomics

Imaging-based ST technologies utilize variations of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to detect and localize mRNA molecules directly within tissue sections. These methods typically involve hybridization probes that bind to target RNA sequences, followed by multiple rounds of staining with fluorescent reporters, imaging, and destaining to map transcript identities with single-molecule resolution [10].

Key imaging-based platforms include:

- Vizgen MERSCOPE: Utilizes direct probe hybridization with signal amplification achieved by tiling transcripts with multiple probes [10]

- 10X Genomics Xenium: Employs padlock probes with rolling circle amplification for signal enhancement [10] [2]

- NanoString CosMx: Uses a limited number of probes amplified through branch chain hybridization [10]

Sequencing-Based Spatial Transcriptomics

Sequencing-based approaches, such as 10X Genomics Visium, capture spatial gene expression by placing tissue sections on barcoded substrates where mRNA molecules are tagged with oligonucleotide addresses indicating their spatial location. The tagged mRNA is then isolated for next-generation sequencing, with computational mapping used to reconstruct transcript identities to specific locations [10] [11].

Overview of Spatial Transcriptomics Technologies

Platform Performance Comparison

A comprehensive 2025 benchmark study directly compared three commercial iST platforms—10X Xenium, Vizgen MERSCOPE, and Nanostring CosMx—using serial sections from tissue microarrays containing 17 tumor and 16 normal tissue types from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples [10].

Sensitivity and Specificity Metrics

The benchmarking revealed significant differences in platform performance across multiple technical parameters critical for research validation.

Table 1: Platform Performance Comparison on FFPE Samples

| Performance Metric | 10X Xenium | Nanostring CosMx | Vizgen MERSCOPE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcript Counts per Gene | Consistently higher | Moderate | Lower |

| Concordance with scRNA-seq | High | High | Variable |

| Cell Sub-clustering Capability | Slightly more clusters | Slightly more clusters | Fewer clusters |

| False Discovery Rates | Varies | Varies | Varies |

| Cell Segmentation Error Frequency | Varies | Varies | Varies |

| FFPE Compatibility | High | High | High (with DV200 >60% recommendation) |

Experimental Design for Platform Validation

The benchmark study employed a rigorous experimental design to ensure fair comparison across platforms [10]:

Sample Preparation:

- Tissue microarrays (TMAs) containing 33 different tumor and normal tissue types

- Serial sections from the same FFPE blocks applied to each platform

- Samples not pre-screened based on RNA integrity to reflect typical biobanked FFPE tissues

Panel Design:

- Custom panels designed to maximize gene overlap across platforms (>65 shared genes)

- Xenium: Human breast, lung, and multi-tissue off-the-shelf panels

- MERSCOPE: Custom panels matching Xenium breast and lung panels

- CosMx: Standard 1K panel

Data Processing:

- Standard base-calling and segmentation pipelines from each manufacturer

- Data subsampled and aggregated to individual TMA cores

- Total dataset: >394 million transcripts and >5 million cells

Validation Against Bulk and Single-Cell RNA-seq

A critical application of spatial transcriptomics lies in its ability to validate findings from bulk RNA-seq research, providing spatial context to transcriptomic data.

Concordance with Orthogonal Transcriptomic Methods

The 2025 benchmark study specifically evaluated how well iST data correlates with scRNA-seq data collected by 10x Chromium Single Cell Gene Expression FLEX. The results demonstrated that Xenium and CosMx measure RNA transcripts in strong concordance with orthogonal single-cell transcriptomics, providing confidence in their ability to validate scRNA-seq findings while adding the crucial spatial dimension [10].

Advantages Over Bulk RNA-seq

While bulk RNA-seq provides valuable information on average gene expression across cell populations, it masks cellular heterogeneity and eliminates spatial context. Spatial transcriptomics overcomes these limitations by [2] [12]:

- Preserving spatial relationships between cells within native tissue architecture

- Identifying spatially restricted gene expression patterns and gradients

- Visualizing cell-cell interactions and microenvironmental influences

- Characterizing rare cell populations in their functional context

Spatial Transcriptomics in Validation Workflow

Analytical Frameworks and Tools

The analysis of spatial transcriptomics data requires specialized computational approaches that incorporate both gene expression and spatial information.

Data Processing Workflows

Seurat provides comprehensive analytical frameworks for both sequencing-based and imaging-based spatial transcriptomics data [13]. The standard workflow includes:

- Normalization using SCTransform with modified clipping parameters for smFISH data

- Dimensional reduction using PCA and UMAP

- Spatial clustering incorporating coordinate information

- Cell segmentation boundary analysis and molecule localization

SpatialDE uses Gaussian process regression to decompose variability into spatial and non-spatial components, identifying genes with spatially coherent expression patterns [11].

Multi-Slice Alignment and 3D Reconstruction

A significant challenge in spatial transcriptomics involves aligning and integrating multiple tissue slices to reconstruct three-dimensional tissue architecture. Recent computational advances have produced at least 24 different methodologies for this task, which can be categorized into [14]:

- Statistical mapping approaches (10 tools including PASTE, GPSA, PRECAST)

- Image processing and registration (4 tools including STalign, STUtility)

- Graph-based methods (10 tools including SpatiAlign, STAligner)

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Spatial Transcriptomics

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| FFPE Tissue Sections | Preserves tissue morphology and RNA stability | Standard sample format for clinical archives; enables retrospective studies |

| Tissue Microarrays (TMAs) | Multiplexed tissue analysis platform | Enables parallel processing of multiple tissue types on a single slide |

| Custom Gene Panels | Targeted RNA detection probes | Allows focused investigation of specific gene sets across platforms |

| Cell Segmentation Reagents | Define cellular boundaries (e.g., membrane stains) | Critical for accurate single-cell resolution and transcript assignment |

| 10X Chromium Single Cell Gene Expression FLEX | Orthogonal scRNA-seq validation | Provides reference data for evaluating iST platform accuracy |

Future Directions and Challenges

As spatial transcriptomics continues to evolve, several key areas represent both challenges and opportunities for advancement:

Technical Innovations:

- Scalable spatial genomics approaches that eliminate time-intensive imaging through computational array reconstruction [15]

- Whole-transcriptome coverage in imaging-based methods, as demonstrated by NanoString's SMI platform claiming coverage of up to 18,000 genes [2]

- Spatial multi-omics integrating transcriptomic, proteomic, and epigenetic data from the same tissue section

Analytical Advancements:

- Deep learning applications for gene expression prediction from histology images and data completion to address dropout events [16]

- Spatiotemporal trajectory inference methods like STORIES that leverage optimal transport to model cellular differentiation through time and space [17]

- Integrated 3D tissue reconstruction from multiple 2D slices to better represent native tissue architecture [14]

In conclusion, spatial transcriptomics provides powerful technologies for validating and extending bulk RNA-seq research by adding the crucial dimension of spatial context. The choice of platform involves important trade-offs between sensitivity, resolution, gene coverage, and sample requirements. As these technologies continue to mature and become more accessible, they promise to transform our understanding of tissue biology in both health and disease.

Spatial transcriptomics (ST) has emerged as a pivotal technology for studying gene expression within the architectural context of tissues, providing insights into cellular interactions, tumor microenvironments, and tissue function that are lost in bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing methods [18] [19]. The field has rapidly evolved into two principal technological categories: imaging-based and sequencing-based approaches [20] [18] [21]. Imaging-based technologies utilize fluorescence in situ hybridization with specialized probes to localize RNA molecules directly in tissue sections, while sequencing-based methods capture RNA onto spatially barcoded arrays for subsequent next-generation sequencing [18]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these platforms, focusing on their performance characteristics, experimental requirements, and applications within translational research, particularly for studies validating findings against bulk RNA-seq data.

Core Technological Principles

The fundamental difference between imaging-based and sequencing-based spatial transcriptomics lies in their methods for determining the spatial localization and abundance of mRNA molecules within tissue architectures [18] [21].

Imaging-Based Technologies

Imaging-based platforms employ variations of single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) to detect and localize targeted RNA transcripts through cyclic imaging [18] [21]. The following diagram illustrates the core workflows for the three major commercial imaging-based platforms:

Xenium (10x Genomics) employs a hybrid technology combining in situ sequencing and hybridization [18] [21]. It uses padlock probes that hybridize to target RNA transcripts, followed by ligation and rolling circle amplification to create multiple DNA copies for enhanced signal detection [18] [21]. Fluorescently labeled probes then bind to these amplified sequences through approximately 8 rounds of hybridization and imaging, generating optical signatures for gene identification [18].

MERSCOPE (Vizgen) utilizes a binary barcoding strategy where each gene is assigned a unique barcode of "0"s and "1"s [18] [21]. Through multiple rounds of hybridization with fluorescent readout probes, the presence ("1") or absence ("0") of fluorescence is recorded to construct the barcode for each transcript, enabling error detection and correction [18].

CosMx SMI (NanoString) uses a combination of multiplex probes and cyclic readouts [18] [21]. Five gene-specific probes bind to each target transcript, each containing a readout domain with 16 sub-domains [18]. Fluorescent secondary probes hybridize to these sub-domains over 16 cycles, with UV cleavage between rounds, creating a unique color and position signature for each gene [18].

Sequencing-Based Technologies

Sequencing-based platforms integrate spatially barcoded arrays with next-generation sequencing to localize and quantify transcripts [18] [21]. The core workflow involves:

Visium and Visium HD (10x Genomics) rely on slides coated with spatially barcoded RNA-binding probes containing unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) and poly(dT) sequences for mRNA capture [21]. While standard Visium has a spot size of 55μm, Visium HD reduces this to 2μm for enhanced resolution [21]. The technology uses a CytAssist instrument for FFPE samples to transfer probes from standard slides to the Visium surface [21].

Stereo-seq utilizes DNA nanoball (DNB) technology, where oligo probes are circularized and amplified via rolling circle amplification to create DNBs that are patterned on an array [21]. With a diameter of approximately 0.2μm and center-to-center distance of 0.5μm, Stereo-seq offers superior resolution compared to other sequencing-based methods [21].

GeoMx Digital Spatial Profiler employs a different approach using UV-photocleavable barcoded oligos that are hybridized to tissue sections [18]. Regions of interest are selected based on morphology, and barcodes from these regions are released through UV exposure and collected for sequencing [18].

Performance Comparison Across Platforms

Technical Specifications

Table 1: Technical Specifications of Major Commercial Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms

| Platform | Technology Type | Spatial Resolution | Gene Coverage | Tissue Compatibility | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xenium | Imaging-based | Single-cell/Subcellular | Targeted panels (300-500 genes) | FFPE, Fresh Frozen | Moderate |

| MERSCOPE | Imaging-based | Single-cell/Subcellular | Targeted panels (500-1000 genes) | FFPE, Fresh Frozen | Moderate |

| CosMx SMI | Imaging-based | Single-cell/Subcellular | Targeted panels (1000-6000 genes) | FFPE, Fresh Frozen | Moderate |

| Visium | Sequencing-based | Multi-cell (55μm spots) | Whole transcriptome | FFPE, Fresh Frozen | High |

| Visium HD | Sequencing-based | Single-cell (2μm spots) | Whole transcriptome | FFPE, Fresh Frozen | High |

| Stereo-seq | Sequencing-based | Single-cell/Subcellular (0.5μm) | Whole transcriptome | Fresh Frozen (FFPE emerging) | High |

| GeoMx DSP | Sequencing-based | Region of interest (ROI) | Whole transcriptome or targeted | FFPE, Fresh Frozen | High |

Experimental Performance Metrics

Recent benchmarking studies have provided quantitative comparisons of platform performance using controlled experiments with matched tissues. Key findings from studies using Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tissues are summarized below:

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Imaging-Based Platforms from Benchmarking Studies Using FFPE Tissues

| Performance Metric | Xenium | CosMx | MERSCOPE | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcript counts per cell | High | Highest | Variable | CosMx detected highest transcript counts; MERFISH showed lower counts in older tissues [22] [7] |

| Sensitivity | High | High | Moderate | Xenium and CosMx showed higher sensitivity in comparative studies [23] |

| Concordance with scRNA-seq | High | High | Not reported | Xenium and CosMx demonstrated strong correlation with single-cell transcriptomics [23] |

| Cell segmentation accuracy | High with multimodal | Moderate | Variable | Xenium's multimodal segmentation improved accuracy [22] [23] |

| Specificity (background signal) | High | Variable | Not assessable | CosMx showed target genes expressing at negative control levels; MERFISH lacked negative controls for comparison [22] [7] |

| Tissue age compatibility | Consistent performance | Performance declined with older tissues | Performance declined with older tissues | MERFISH and CosMx showed reduced performance in older archival tissues [22] |

For sequencing-based platforms, a comprehensive benchmarking study (cadasSTre) comparing 11 methods revealed significant variations in performance [6]:

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Sequencing-Based Platforms from Benchmarking Studies

| Performance Metric | Visium (Probe-based) | Visium (polyA-based) | Slide-seq V2 | Stereo-seq |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity in hippocampus | High | Moderate | High | Variable with sequencing depth |

| Sensitivity in mouse eye | High | Low | High | Variable with sequencing depth |

| Molecular diffusion | Variable | Variable | Lower | Lower |

| Marker gene detection | Consistent | Inconsistent in some tissues | Consistent | Consistent |

| Sequencing saturation | Not reached at 300M reads | Not reached at 300M reads | Not reached | Not reached at 4B reads |

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Benchmarking Experimental Protocols

Recent comparative studies have established rigorous methodologies for evaluating spatial transcriptomics platforms. The following experimental approaches provide frameworks for objective platform assessment:

Controlled TMA Studies for Imaging-Based Platforms: Studies comparing Xenium, MERSCOPE, and CosMx utilized tissue microarrays (TMAs) containing multiple tumor and normal tissue types, including lung adenocarcinoma and pleural mesothelioma samples [22] [23] [7]. Serial 5μm sections from FFPE blocks were distributed to each platform, ensuring matched sample comparison [22] [7]. Validation methods included bulk RNA sequencing, multiplex immunofluorescence, GeoMx Digital Spatial Profiler analysis, and H&E staining of adjacent sections [22] [7]. Performance metrics included transcripts per cell, unique genes per cell, cell segmentation accuracy, signal-to-background ratio using negative control probes, and concordance with orthogonal methods [22] [23].

cadasSTre Framework for Sequencing-Based Platforms: The cadasSTre study established a standardized benchmarking pipeline for 11 sequencing-based methods using reference tissues with well-defined histological architectures (mouse embryonic eyes, hippocampal regions, and olfactory bulbs) [6]. The methodology involved: (1) standardized tissue processing and sectioning; (2) data generation across platforms; (3) downsampling to normalize sequencing depth; (4) evaluation of sensitivity, spatial resolution, and molecular diffusion; and (5) assessment of downstream applications including clustering, region annotation, and cell-cell communication analysis [6].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Spatial Transcriptomics Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Platform Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Spatially Barcoded Slides | Capture location-specific transcript information | Platform-specific (Visium, Stereo-seq arrays) |

| Gene Panel Probes | Hybridize to target transcripts for detection | Imaging platforms (Xenium, MERSCOPE, CosMx) |

| Fluorophore-Labeled Readout Probes | Visualize hybridized probes through fluorescence | Imaging platforms (cycle-specific) |

| CytAssist Instrument | Transfer probes from standard slides to Visium slide | Visium FFPE workflow |

| Library Preparation Kits | Prepare sequencing libraries from captured RNA | Sequencing-based platforms |

| Nucleic Acid Amplification Reagents | Amplify signals for detection | All platforms (method varies) |

| Tissue Permeabilization Reagents | Enable probe access to intracellular RNA | All platforms (optimization critical) |

| UV Cleavage Reagents | Remove fluorescent signals between imaging cycles | CosMx platform |

| Negative Control Probes | Assess background signal and specificity | Quality control (varies by platform) |

| Morphology Markers | Facilitate cell segmentation and annotation | All platforms (especially with H&E) |

Platform Selection Guide

Application-Based Selection Criteria

Choosing between imaging-based and sequencing-based spatial transcriptomics technologies depends on research goals, sample characteristics, and resource constraints [20] [21].

Choose Imaging-Based Platforms When:

- Studying known targets with defined gene panels [20]

- Single-cell or subcellular resolution is required [20] [18]

- High sensitivity for targeted genes is prioritized [23]

- Sample availability is not limiting (lower throughput) [20]

- Budget allows for custom probe development [20]

Choose Sequencing-Based Platforms When:

- Discovery-based research requiring whole transcriptome coverage [20]

- Studying novel targets or pathways without predefined genes [20]

- Higher throughput analysis of multiple samples is needed [20]

- Integration with existing single-cell RNA-seq datasets is planned [20]

- Budget constraints favor standardized workflows [20]

Validation with Bulk RNA-seq

For researchers working within a bulk RNA-seq validation framework, specific considerations apply:

Sequencing-based platforms facilitate more direct comparison with bulk RNA-seq data due to shared whole-transcriptome coverage and similar data structures [20]. The unbiased nature of both methods enables correlation analysis of expression patterns across matched samples [6].

Imaging-based platforms provide orthogonal validation of bulk RNA-seq findings through spatial localization of key identified targets [20]. Once differentially expressed genes are identified through bulk RNA-seq, imaging platforms can confirm their spatial distribution and cell-type specificity within tissues [20].

Integrated approaches combining both methodologies offer the most comprehensive validation framework, using sequencing-based ST for discovery and imaging-based ST for targeted validation of spatial patterns [20].

The taxonomy of spatial transcriptomics technologies presents researchers with complementary tools for exploring gene expression in structural context. Imaging-based platforms offer high resolution and sensitivity for targeted studies, while sequencing-based approaches provide unbiased transcriptome-wide coverage for discovery research. Recent benchmarking studies have quantified performance differences, revealing variations in sensitivity, specificity, and tissue compatibility that should inform platform selection. Within validation frameworks building on bulk RNA-seq findings, the choice between these technologies should align with research objectives, with sequencing-based methods extending discovery and imaging-based methods providing spatial confirmation of key targets. As the field evolves, integration of both approaches will likely provide the most comprehensive understanding of spatial gene regulation in health and disease.

Why Validate? Establishing Confidence in Spatial Data Through Bulk RNA-seq Correlation

Spatial transcriptomics (ST) has revolutionized biological research by enabling researchers to study gene expression within the intact architectural context of tissues. However, the rapid emergence of diverse ST platforms, each with distinct technological principles and performance characteristics, has created a critical need for rigorous validation against established genomic methods [6] [23]. Bulk RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq) serves as a fundamental benchmark in this validation process, providing a trusted reference point against which newer spatial technologies can be evaluated [24]. Establishing strong correlation between ST data and bulk RNA-seq measurements gives researchers confidence that their spatial findings accurately reflect biological reality rather than technical artifacts [25].

The validation imperative stems from the significant methodological diversity among ST platforms. Sequencing-based spatial transcriptomics (sST) approaches, such as 10x Genomics Visium and Stereo-seq, employ spatial barcoding to capture location-specific transcriptome data [6]. In contrast, imaging-based spatial transcriptomics (iST) platforms, including Xenium, MERSCOPE, and CosMx, utilize in situ hybridization with fluorescent probes to localize transcripts within tissues [23]. Each methodology presents unique trade-offs in resolution, sensitivity, and specificity that must be quantitatively assessed through comparison with gold-standard bulk measurements [25]. This guide provides an objective comparison of leading ST platforms through the lens of bulk RNA-seq correlation, empowering researchers to make informed decisions when designing spatially resolved transcriptomic studies.

Platform Performance Comparison: Quantitative Metrics Against Bulk RNA-seq

Systematic benchmarking studies have evaluated ST platform performance using unified experimental designs and multiple cancer types, enabling direct comparison of their correlation with bulk RNA-seq references.

Sequencing-Based Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms

Sequencing-based approaches provide unbiased whole-transcriptome coverage but vary significantly in spatial resolution and capture efficiency [6] [25].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Sequencing-Based Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms

| Platform | Spatial Resolution | Key Correlation Metrics with Bulk RNA-seq | Sensitivity (Marker Genes) | Specificity | Reference Tissue Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stereo-seq v1.3 | 0.5 μm sequencing spots | High gene-wise correlation with scRNA-seq [25] | Moderate | High | Colon adenocarcinoma, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Ovarian cancer [25] |

| Visium HD FFPE | 2 μm | High gene-wise correlation with scRNA-seq [25] | Outperformed Stereo-seq in cancer cell markers [25] | High | Colon adenocarcinoma, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Ovarian cancer [25] |

| 10X Visium (Probe-Based) | 55 μm | Highest summed total counts in mouse eye tissue; high sensitivity for regional markers [6] | High in hippocampus and eye regions | High | Mouse brain, E12.5 mouse embryo [6] |

| Slide-seq V2 | 10 μm | Demonstrated higher sensitivity than other platforms in mouse eye [6] | High sensitivity in controlled downsampling | Moderate | Mouse hippocampus and eye [6] |

Imaging-Based Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms

Imaging-based platforms offer single-cell or subcellular resolution through targeted gene panels, with performance varying by signal amplification strategy and probe design [23] [25].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Imaging-Based Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms

| Platform | Spatial Resolution | Key Correlation Metrics with Bulk RNA-seq | Sensitivity | Specificity | Reference Tissue Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10X Xenium 5K | Subcellular | High gene-wise correlation with scRNA-seq; superior sensitivity for multiple marker genes [25] | Highest among iST platforms | High | 33 tumor and normal tissue types from TMAs [23] [25] |

| Nanostring CosMx 6K | Subcellular | Substantial deviation from scRNA-seq reference in gene-wise transcript counts [25] | Lower than Xenium despite higher total transcripts | High | 33 tumor and normal tissue types from TMAs [23] [25] |

| Vizgen MERSCOPE | Subcellular | Quantitative reproduction of bulk RNA-seq and scRNA-seq results with improved dropout rates [24] | High, with low dropout rates | High | Mouse liver and kidney [24] |

| MERFISH | Single-molecule | Strong concordance with bulk RNA-seq; independently resolves cell types without computational integration [24] | High, with low dropout rates | High | Mouse liver and kidney [24] |

Experimental Protocols for Spatial Technology Validation

Standardized Benchmarking Workflow

Systematic platform evaluation requires standardized workflows that control for tissue heterogeneity and processing variables. Leading benchmarking studies employ these key methodological approaches:

- Multi-platform TMA Profiling: Utilize tissue microarrays (TMAs) containing multiple tumor and normal tissue types (e.g., 17 tumor types, 16 normal types) processed as serial sections to enable direct cross-platform comparison [23].

- Reference Dataset Generation: Establish ground truth through complementary multi-omics profiling including CODEX for protein expression, scRNA-seq on matched samples, and manual annotation of nuclear boundaries [25].

- Region-Restricted Analysis: Manually delineate anatomical regions with well-defined morphology (e.g., mouse hippocampus, E12.5 mouse eyes) to ensure comparisons originate from identical tissue locations [6].

- Sequencing Depth Normalization: Perform downsampling to normalize different methods to the same total number of sequencing reads, eliminating variability from differential sequencing depth [6].

Correlation Assessment Methodology

The specific protocols for establishing bulk RNA-seq correlation include:

- Bulk Tissue Expression Correlation: Calculate total transcript counts per gene across entire tissue sections and assess correlation with matched bulk RNA-seq profiles using Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients [25].

- Regional Marker Gene Validation: Select known anatomical marker genes (e.g., Prdm8, Prox1 in CA3 hippocampus; Vit, Crybb3 in mouse lens) and quantify their expression within specific tissue regions across platforms [6].

- Cell-Type Specific Signature Validation: Deconvolve bulk expression signatures into cell-type specific profiles and verify these against spatially resolved cell-type identification [26] [27].

- Spatial Domain Identification Concordance: Compare spatially defined tissue domains (e.g., tumor vs. non-tumor regions) identified through ST with those inferred from bulk RNA-seq using computational approaches [28].

Spatial Transcriptomics Validation Workflow

Platform Selection Guide: Matching Technology to Research Objectives

The optimal choice of spatial transcriptomics platform depends on specific research goals, sample characteristics, and analytical requirements.

Platform Recommendations by Research Application

- Tumor Microenvironment Studies: Xenium 5K demonstrates superior sensitivity for cancer cell markers (e.g., EPCAM) and high correlation with scRNA-seq, enabling precise characterization of tumor heterogeneity [25].

- Developmental Biology: Stereo-seq v1.3 provides high-resolution, whole-transcriptome coverage ideal for capturing rare cell states and subtle expression gradients in developing tissues [6].

- Neuroscience Research: MERFISH offers exceptional spatial resolution and low dropout rates, successfully resolving complex cell-type patterning in brain regions like the hippocampus [6] [24].

- Large Cohort Reanalysis: Computational approaches like STGAT and Bulk2Space can estimate spatial expression from existing bulk RNA-seq and whole slide images, extending spatial insights to legacy datasets [28] [26].

Integration Strategies for Enhanced Validation

Combining multiple spatial platforms provides orthogonal validation and compensates for individual technology limitations:

- Targeted + Untargeted Integration: Combine MERFISH (targeted) with Visium (untargeted) to simultaneously achieve high-resolution focusing on key genes while maintaining whole-transcriptome context [24].

- Sequencing + Imaging Correlation: Integrate Stereo-seq data with Xenium measurements to verify transcript localization patterns across technological paradigms [25].

- Computational Cross-Platform Harmonization: Utilize tools like Bulk2Space to generate spatially resolved single-cell expression profiles from bulk RNA-seq, enabling validation through independent methodological approaches [26].

Platform Selection Decision Framework

Successful spatial transcriptomics validation requires careful selection of reagents, reference materials, and computational tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Spatial Transcriptomics Validation

| Category | Specific Resource | Function in Validation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Tissues | Mouse Brain (Hippocampus) | Provides well-defined anatomical regions with known expression patterns for platform calibration [6] | Consistent thickness and distinct regional markers (CA1, CA2, CA3) |

| Reference Tissues | E12.5 Mouse Embryo | Offers developing structures with precise spatial expression gradients [6] | Lens surrounded by neuronal retina cells with known markers |

| Quality Control Assays | DV200 Measurement | Assesses RNA integrity in FFPE samples, particularly important for iST platforms [23] | MERSCOPE recommends >60% threshold; challenging with TMAs |

| Quality Control Assays | H&E Staining | Enables histological assessment and region of interest selection [23] | Standard pathology reference for tissue morphology |

| Computational Tools | Bulk2Space | Spatial deconvolution algorithm generating single-cell expression from bulk RNA-seq [26] | Uses β-VAE deep learning model; enables spatial analysis of existing bulk data |

| Computational Tools | STGAT | Predicts spot-level gene expression from bulk RNA-seq and whole slide images [28] | Graph Attention Network architecture; trained on spatial transcriptomics data |

| Analysis Pipelines | scPipe | Enables preprocessing and downsampling of sST data to normalize sequencing depth [6] | Facilitates fair cross-platform comparison by controlling for read depth |

Establishing correlation with bulk RNA-seq remains a foundational requirement for building confidence in spatial transcriptomics data. The expanding landscape of ST technologies offers researchers unprecedented opportunities to explore tissue biology with spatial context, but these advances must be grounded in rigorous validation against established genomic standards. Platform selection should be guided by specific research questions, with high-sensitivity targeted approaches like Xenium 5K ideal for focused investigations of specific cell populations, and whole-transcriptome methods like Stereo-seq v1.3 better suited for discovery-phase research. As the field evolves toward increasingly higher resolution and throughput, maintaining strong connections to bulk RNA-seq benchmarks will ensure that spatial findings accurately reflect biological truth rather than technical variation. By implementing the standardized validation protocols and comparative frameworks outlined in this guide, researchers can maximize the reliability and impact of their spatial transcriptomics studies.

Bridging the Gap: Methodologies for Cross-Platform Data Integration and Analysis

Leveraging Bulk RNA-seq as a Reference for ST Gene Expression Patterns

Spatial transcriptomics (ST) has revolutionized our understanding of tissue architecture by providing gene expression data within its spatial context. However, the analysis and validation of ST data often require robust reference datasets. Bulk RNA-seq, with its extensive availability from decades of research, presents a valuable resource for supporting ST analysis when appropriately leveraged. This guide compares computational methods that utilize bulk RNA-seq as a reference for uncovering spatial gene expression patterns, evaluating their performance, experimental requirements, and suitability for different research scenarios.

Method Comparison at a Glance

The table below summarizes three prominent computational methods that integrate bulk RNA-seq with spatial transcriptomics data.

Table 1: Comparison of Methods Leveraging Bulk RNA-seq for Spatial Transcriptomics

| Method | Core Approach | Reference Requirements | Key Outputs | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPIC-unmix [29] | Two-step empirical Bayesian deconvolution | sc/snRNA-seq reference data | Cell type-specific (CTS) expression profiles | Up to 187% higher median PCC (Pearson Correlation Coefficient) vs. alternatives; 57.1% lower MSE (Mean Squared Error) [29] |

| Bulk2Space [26] [30] | Deep learning (β-VAE) for spatial deconvolution | scRNA-seq and spatial transcriptomics data | Spatially-resolved single-cell expression profiles | Robust performance across multiple tissues; successful mouse brain structure reconstruction [26] |

| STGAT [28] | Graph Attention Network (GAT) | Spatial transcriptomics and Whole Slide Images (WSI) | Spot-level gene expression; tumor/non-tumor classification | Outperforms existing methods in gene expression prediction; improves cancer sub-type prediction [28] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

EPIC-unmix Methodology

EPIC-unmix employs a two-step empirical Bayesian framework to infer cell type-specific expression from bulk RNA-seq data [29].

Step 1: Prior Estimation

- Input: Single-cell/single-nuclei RNA-seq reference data

- Process: Utilizes the same Bayesian framework as bMIND to build prior distributions of CTS expression

- Output: Preliminary CTS expression profiles for target samples

Step 2: Data-Adaptive Refinement

- Input: Preliminary CTS profiles from Step 1 and bulk RNA-seq data

- Process: Adds a second layer of Bayesian inference to adjust for differences between reference and target datasets

- Output: Refined CTS expression profiles with improved accuracy

Gene Selection Strategy: EPIC-unmix incorporates a robust gene selection strategy to enhance deconvolution accuracy. The method combines:

- External brain snRNA-seq data

- Cell type-specific marker genes from literature

- Marker genes inferred from internal reference datasets (e.g., ROSMAP snRNA-seq)

- Bulk RNA-seq data validation

This strategy identifies 1,003 (microglia), 1,916 (excitatory neurons), 764 (astrocytes), and 548 (oligodendrocytes) genes for optimal deconvolution performance [29].

Bulk2Space Workflow

Bulk2Space uses a deep learning approach for spatial deconvolution in two distinct phases [26] [30]:

Phase 1: Deconvolution

- A beta variational autoencoder (β-VAE) is trained on single-cell reference data to characterize the clustering space of cell types

- The bulk expression vector is represented as the product of the average gene expression matrix of cell types and their abundance vector

- The solved proportion of each cell type serves as a control parameter to generate corresponding single cells within the characterized clustering space

Phase 2: Spatial Mapping Bulk2Space supports two spatial mapping strategies based on available reference data:

For spatial barcoding-based references (e.g., 10X Visium):

- Spots are treated as mixtures of several cells

- Cell-type composition for each spot is calculated

- Generated single cells are mapped to spots based on expression profile similarity while maintaining calculated cell type proportions

For image-based targeted references (e.g., MERFISH, STARmap):

- Pairwise similarity is calculated using shared genes between datasets

- Each generated single cell is mapped to optimal coordinates in the spatial reference

- This approach provides unbiased transcriptomes with improved gene coverage

STGAT Framework

STGAT employs a multi-modular approach to predict spot-level gene expression [28]:

Module 1: Spot Embedding Generator (SEG)

- Uses Convolutional Neural Networks to process spot images from Whole Slide Images

- Generates embeddings that capture visual features of each spot

- Trained initially on spatial transcriptomics data

Module 2: Gene Expression Predictor (GEP)

- Combines spot embeddings from SEG with bulk RNA-seq data processed through fully connected layers

- Estimates gene expression profiles for each spot

- Transfers learning from spatial transcriptomics to bulk RNA-seq data

Module 3: Spot Label Predictor (SLP)

- Classifies spots as tumor or non-tumor tissue

- Enables focused analysis on regions of interest

The fundamental hypothesis of STGAT is that gene expression from tumor-only spots provides stronger molecular signals for disease phenotype correlation compared to bulk RNA-seq data, which includes noise from irrelevant cell types [28].

Performance Evaluation Metrics

Quantitative Assessment

Table 2: Performance Metrics Across Validation Studies

| Method | Accuracy Metrics | Robustness Evaluation | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| EPIC-unmix [29] | 45.2% higher mean PCC and 56.9% higher median PCC for selected genes vs. unselected genes; Superior performance across mouse brain and human blood tissues | Maintains accuracy with external references (PsychENCODE); Less performance loss vs. bMIND with reference mismatch | Efficient Bayesian framework suitable for large datasets |

| Bulk2Space [26] | Higher Pearson/Spearman correlation and lower RMSE vs. GAN and CGAN in 30 paired simulations across 10 tissues | Successful application to human blood, brain, kidney, liver, lung and mouse tissues | β-VAE provides balanced performance and efficiency |

| STGAT [28] | Superior gene expression prediction accuracy; Improved cancer sub-type and tumor stage classification | Enhanced survival and disease-free analysis in TCGA breast cancer data | GAT efficiently handles spatial dependencies |

Visualization of Method Workflows

Method Workflow Comparison

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| sc/snRNA-seq Reference Data | Provides cell-type specific expression signatures for deconvolution | Essential for EPIC-unmix; Used as reference in Bulk2Space [29] |

| Spatial Transcriptomics References | Offers spatial patterning information for mapping | Required for Bulk2Space spatial mapping; Used in STGAT training [26] [28] |

| Cell Type Marker Genes | Enables accurate cell type identification and deconvolution | Critical for EPIC-unmix gene selection strategy; Used in validation [29] |

| Whole Slide Images (WSI) | Provides histological context and visual features | Essential for STGAT spot image analysis and classification [28] |

| Bulk RNA-seq Datasets | Primary input for deconvolution and analysis | Required by all methods; Source data for spatial pattern inference [29] [26] [28] |

The integration of bulk RNA-seq as a reference for spatial transcriptomics analysis represents a powerful approach for leveraging existing genomic resources. EPIC-unmix excels in cell type-specific expression inference, particularly for neuronal cell types. Bulk2Space offers comprehensive spatial deconvolution capabilities, generating complete single-cell spatial profiles. STGAT provides superior spot-level expression estimation with specialized functionality for cancer research. Method selection should be guided by specific research goals, available reference data, and target applications, with each approach offering distinct advantages for spatial transcriptomics validation.

Spatial transcriptomics (ST) technologies have revolutionized biological research by enabling the measurement of gene expression profiles within the context of intact tissue architecture, preserving the spatial relationships between cells that are lost in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) workflows [23] [31]. This capability is particularly valuable for studying tissue organization, cellular communication networks, and the spatial context of disease mechanisms. However, a fundamental limitation persists with many popular ST platforms, especially sequencing-based methods like 10x Genomics Visium: their spatial resolution operates at a "multi-cell" level, where each capture spot contains transcripts from multiple potentially heterogeneous cells [31] [32]. This technological constraint creates a critical analytical challenge—to accurately interpret the complex biological signals embedded within these spatial spots, researchers must computationally disentangle, or deconvolve, the mixture of cell types contributing to the measured gene expression in each location [31] [32].

The process of deconvolution serves as a bridge between single-cell reference data and spatial transcriptomics observations, transforming spots of mixed transcripts into quantitative estimates of cellular composition [33]. This transformation is pivotal for accurate biological interpretation, enabling researchers to map cellular niches, identify spatially restricted cell states, and understand tissue microenvironments at a cellular resolution that the raw spatial data itself cannot provide [31]. Within the context of validation for bulk RNA-seq research, deconvolution methods offer a powerful orthogonal approach, allowing researchers to ground truth cell type proportions inferred from bulk sequencing in actual spatial contexts, thereby moving beyond mere quantification to spatial localization of cell populations.

Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms: A Technical Foundation

The performance of deconvolution algorithms is intrinsically linked to the technological platforms generating the spatial data. Currently, spatial transcriptomics technologies fall into two broad categories: imaging-based and sequencing-based approaches, each with distinct trade-offs between spatial resolution, gene throughput, and sensitivity [23] [31].

Imaging-based platforms such as 10X Xenium, Vizgen MERSCOPE, and Nanostring CosMx use variations of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to detect mRNA molecules with subcellular spatial resolution. These methods typically rely on pre-defined gene panels, making them targeted approaches rather than whole-transcriptome methods [23]. A recent systematic benchmarking study across 33 different FFPE tissue types revealed important performance characteristics: Xenium consistently generated higher transcript counts per gene without sacrificing specificity, while both Xenium and CosMx demonstrated strong concordance with orthogonal single-cell transcriptomics data [23]. All three commercial platforms could perform spatially resolved cell typing, though with varying capabilities in sub-clustering and cell segmentation accuracy [23].

In contrast, sequencing-based platforms like 10x Genomics Visium, Slide-seq, and Stereo-seq utilize spatially barcoded oligonucleotides to capture comprehensive transcriptome-wide information but at lower spatial resolution, resulting in spots that typically contain multiple cells [31] [34]. The recent SpatialBenchVisium dataset, generated from mouse spleen tissue, has provided valuable insights into how sample handling protocols affect data quality. Probe-based capture methods, particularly those processed with CytAssist, demonstrated higher UMI counts and improved mapping confidence compared to poly-A-based methods [34]. This has direct implications for deconvolution accuracy, as higher data quality in the spatial input enables more reliable estimation of cell-type proportions.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Commercial Imaging Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms

| Platform | Chemistry Principle | Sensitivity (Transcript Counts) | Concordance with scRNA-seq | Segmentation Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10X Xenium | Padlock probes + rolling circle amplification | High | Strong | Good, improved with membrane staining |

| Nanostring CosMx | Branch chain hybridization | High | Strong | Varies |

| Vizgen MERSCOPE | Direct hybridization with probe tiling | Moderate | Not specified | Varies with segmentation errors |

Computational Deconvolution: Methodological Approaches

The computational challenge of deconvolution involves estimating the cellular composition of each spatial spot based on a reference profile of expected cell types. This field has seen rapid methodological innovation, with algorithms employing diverse mathematical frameworks and computational strategies [31]. These methods can be broadly classified into several categories based on their underlying principles.

Probabilistic models form a major category of deconvolution approaches, using statistical frameworks to model the process of transcript counting and capture. Methods like Cell2location, RCTD, DestVI, and Stereoscope employ Bayesian or negative binomial models to estimate cell-type abundances while accounting for technical noise and overdispersion in spatial data [31] [32]. These approaches often incorporate spatial smoothing or hierarchical structures to improve accuracy by leveraging the natural dependency between neighboring spots.

Non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) techniques represent another important class of deconvolution algorithms. Methods like SPOTlight and jMF2D factorize the spatial expression matrix into two non-negative components: a signature matrix representing cell-type-specific expression and an abundance matrix encoding cell-type proportions per spot [33] [31]. The jMF2D algorithm exemplifies recent advances in this category, jointly learning cell-type similarity networks and spatial spot networks to enhance deconvolution accuracy while dramatically reducing computational time—by approximately 90% compared to state-of-the-art baselines [33].

Deep learning approaches constitute an emerging frontier in deconvolution methodology. These methods use neural networks to learn complex, non-linear relationships between spot expression patterns and cellular compositions [35] [36]. While often requiring larger training datasets, deep learning models can capture subtle patterns that may be missed by linear methods and demonstrate strong generalization across diverse tissues and experimental conditions [35].

A significant recent advancement in the field is the development of single-cell resolution deconvolution, exemplified by the Redeconve algorithm [32]. Unlike previous methods limited to tens of coarse cell types, Redeconve can resolve thousands of nuanced cell states within spatial spots by introducing a regularization term that assumes similar single cells have similar abundance patterns in ST spots [32]. This innovation enables the interpretation of spatial transcriptomics data at unprecedented resolution, revealing cancer-clone-specific immune infiltration and other fine-grained biological phenomena that were previously inaccessible [32].

Table 2: Classification of Spatial Transcriptomics Deconvolution Algorithms

| Method Category | Representative Algorithms | Key Characteristics | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probabilistic Models | Cell2location, RCTD, DestVI, Stereoscope | Account for technical noise, spatial dependencies | Visium, Slide-seq data with reference |

| NMF-Based Methods | SPOTlight, jMF2D, NMFreg | Linear factorization, interpretable components | Integration of scRNA-seq and ST data |

| Deep Learning Approaches | Custom neural networks | Non-linear relationships, pattern recognition | Large-scale datasets with complex patterns |

| Graph-Based Methods | DSTG, STAligner | Incorporate spatial neighborhood information | Multi-slice analysis, spatial domain identification |

| Single-Cell Resolution | Redeconve | Resolves thousands of cell states | Fine-grained cellular heterogeneity |

Experimental Design and Protocol Considerations

Implementing robust deconvolution analyses requires careful experimental design and appropriate protocol selection. For sequencing-based spatial technologies, sample preparation method significantly impacts data quality and downstream deconvolution performance. The SpatialBenchVisium study demonstrated that probe-based capture methods, particularly those using CytAssist for tissue placement, yield higher UMI counts and reduced spot-swapping effects compared to poly-A-based methods [34]. This technical improvement directly enhances deconvolution accuracy by providing higher-quality input data.

A critical consideration in deconvolution workflow design is the integration of matched single-cell RNA sequencing data as reference. The quality and representativeness of this reference significantly impacts deconvolution performance [35] [32]. When suitable matched reference is available, methods like Redeconve can achieve >0.8 cosine accuracy for most spatial spots, while even with partially matched references, performance remains superior to alternative approaches [32]. For situations where matched single-cell data is unavailable, reference-free methods like STdeconvolve and Berglund offer alternative approaches by discovering latent cell-type profiles directly from spatial data [31].

Multi-slice integration represents another advanced application where deconvolution plays a crucial role. Recent benchmarking of 12 multi-slice integration methods across 19 diverse datasets revealed that performance is highly dependent on application context, dataset size, and technology [37]. Methods like GraphST-PASTE excelled at removing batch effects, while MENDER, STAIG, and SpaDo better preserved biological variance [37]. This highlights the importance of selecting integration methods aligned with specific analytical goals.

The following diagram illustrates a complete experimental workflow for spatial transcriptomics deconvolution, from sample preparation through biological interpretation:

Successful implementation of spatial deconvolution requires both wet-lab reagents and computational resources. The following table details key solutions essential for conducting robust deconvolution analyses:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Spatial Deconvolution Studies

| Category | Specific Product/Resource | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Platform Kits | 10x Visium Spatial Gene Expression | Whole transcriptome spatial capture on slides |

| Xenium, CosMx, MERSCOPE panels | Targeted gene panel measurement with subcellular resolution | |

| Sample Preparation | Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) reagents | Clinical sample preservation for spatial analysis |

| Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) compounds | Fresh frozen tissue preservation | |

| CytAssist instrument | Automated tissue placement for improved data quality | |

| Reference Generation | 10x Chromium Single Cell Gene Expression FLEX | Matched scRNA-seq reference data generation |

| Single-cell isolation reagents | Tissue dissociation for reference scRNA-seq | |

| Computational Tools | Redeconve, Cell2location, jMF2D | Deconvolution algorithms for cell-type abundance |

| Galaxy SPOC platform | Accessible, reproducible analysis workflows | |

| Seurat, Scanpy, Giotto | Spatial data analysis and visualization environments | |

| Validation Reagents | Immunofluorescence antibodies | Protein-level validation of cell-type identities |

| RNAscope probes | Orthogonal RNA validation of spatial patterns |

Comparative Performance Analysis Across Platforms and Methods

Rigorous benchmarking studies provide critical insights into the relative performance of different deconvolution approaches. A comprehensive evaluation of deconvolution algorithms revealed that method performance varies significantly across accuracy, resolution, speed, and applicability to different technological platforms [31] [32].

In terms of resolution and accuracy, Redeconve demonstrated superior performance in estimating cellular composition at single-cell resolution across diverse spatial platforms including 10x Visium, Slide-seq v2, and other sequencing-based technologies [32]. When evaluated against ground truth data from nucleus counting, Redeconve showed high conformity without requiring prior knowledge of cell counts, performing comparably to methods like cell2location and Tangram that incorporate cell density information [32]. The algorithm also achieved higher reconstruction accuracy of gene expression per spot across multiple similarity measures including cosine similarity, Pearson's correlation, and Root Mean Square Error [32].

Regarding computational efficiency, significant differences exist between methods. jMF2D demonstrates remarkable speed advantages, saving approximately 90% of running time compared to state-of-the-art baselines while maintaining high accuracy [33]. Redeconve also shows superior computational speed compared to current deconvolution algorithms, with the additional benefit of supporting parallel computation due to its spot-by-spot processing approach [32].

The following diagram illustrates the core mathematical concept behind deconvolution, where observed spot expression is decomposed into cell-type signatures and proportions:

For technology-specific performance, benchmarking reveals that platform choice significantly impacts achievable outcomes. In imaging-based spatial technologies, Xenium consistently generates higher transcript counts per gene without sacrificing specificity, while both Xenium and CosMx maintain strong concordance with orthogonal single-cell transcriptomics data [23]. All three major commercial platforms (Xenium, CosMx, MERSCOPE) can perform spatially resolved cell typing, with Xenium and CosMx finding slightly more clusters than MERSCOPE, though with different false discovery rates and cell segmentation error frequencies [23].

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Spatial deconvolution methods have enabled sophisticated biological applications that reveal novel insights into tissue organization and disease mechanisms. In a study of vestibular schwannoma, researchers integrated scRNA-seq data with spatial transcriptomics to identify a VEGFA-enriched Schwann cell subtype that was centrally localized within tumor tissue [38]. Through spatial deconvolution using RCTD, they systematically mapped major cell populations within spatially resolved domains and identified strong co-localization relationships between fibroblasts and Schwann cells, indicating marked cellular dependency between these cell types [38].

The field continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping future development. Multi-modal integration approaches that combine spatial transcriptomics with other data types such as epigenomics, proteomics, and histology images represent an important frontier [37]. Deep learning methods are gaining traction for their ability to model complex non-linear relationships in spatial data, though challenges of interpretability and data requirements remain [35] [36]. As spatial technologies advance toward higher resolution, development of scalable algorithms that can efficiently process increasingly large datasets will be crucial [33] [37].

For researchers planning spatial studies with deconvolution analyses, key recommendations emerge from benchmarking studies: (1) select platforms that balance resolution with transcriptome coverage based on specific biological questions; (2) invest in generating high-quality matched scRNA-seq references when possible; (3) choose deconvolution methods aligned with analytical goals, considering trade-offs between resolution, speed, and accuracy; and (4) incorporate orthogonal validation through imaging or other spatial assays to confirm computational predictions [23] [32] [38].

As spatial technologies continue to mature and computational methods become more sophisticated, deconvolution will play an increasingly central role in extracting biological insights from complex tissue environments, ultimately advancing our understanding of development, disease, and tissue organization at cellular resolution.

Spatial transcriptomics technologies have revolutionized biological research by preserving the spatial context of gene expression, but a key limitation of many popular platforms is their low spatial resolution. Each measurement "spot" often captures the transcriptomes of multiple cells, blending different cell types and obscuring true cellular spatial patterns. Deconvolution algorithms address this by computationally disentangling these mixed signals to estimate the proportion of each cell type within every spot. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of four prominent deconvolution methods—Cell2location, RCTD, Tangram, and SpatialDWLS—focusing on their performance, underlying methodologies, and applicability in validation workflows for bulk RNA-seq research [39].

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of these four algorithms.

| Method | Core Computational Technique | Underlying Data Model | Key Input Requirements | Primary Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell2location [40] [41] [39] | Bayesian probabilistic model | Negative binomial regression [40] | scRNA-seq reference, spatial data | Cell-type abundances per spot |

| RCTD [40] [41] [39] | Probabilistic model with maximum likelihood estimation | Poisson distribution [40] | scRNA-seq reference, spatial data | Cell-type proportions per spot |

| Tangram [42] [41] [43] | Deep learning (non-convex optimization) | Not distribution-based; uses cosine similarity [43] | scRNA-seq reference, spatial data | Probabilistic mapping of single cells to spots |

| SpatialDWLS [40] [41] [39] | Non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) & least squares regression | NMF and weighted least squares [39] | scRNA-seq reference, spatial data | Cell-type proportions per spot |

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking Data

Independent benchmarking studies are crucial for evaluating the real-world performance of computational methods. A comprehensive 2023 study in Nature Communications assessed 18 deconvolution methods on 50 simulated and real-world datasets, providing robust performance data for these tools [41].

The table below summarizes the quantitative performance of the four methods across different data types, based on metrics like Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE) and Jensen-Shannon Divergence (JSD) for simulated data (where ground truth is known) and Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) for real data (comparing deconvolution results with marker gene expression) [41].

| Method | Performance on Simulated Data (seqFISH+) [41] | Performance on Simulated Data (MERFISH) [41] | Performance on Real-world Data (10X Visium, Slide-seqV2) [41] | Notable Strengths & Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell2location | Moderate Accuracy | High Accuracy | High Accuracy [41] | Strength: Handles large tissue views well. [41] Weakness: Computationally intensive. |

| RCTD | Information Missing | High Accuracy | Moderate Accuracy [41] | Strength: Robust performance across modalities. [40] Weakness: May struggle with very rare cell types. |

| Tangram | Low to Moderate Accuracy | High Accuracy | High Accuracy [41] | Strength: Can project all single-cell genes into space. [42] Weakness: Performance can drop with low spot numbers. [41] |

| SpatialDWLS | High Accuracy | High Accuracy | Low Accuracy [41] | Strength: Excellent on simulated data with few spots. [41] Weakness: Inconsistent performance on real-world data. [41] |

The benchmarking study concluded that CARD, Cell2location, and Tangram were among the top-performing methods for conducting the cellular deconvolution task [41]. It was also noted that Cell2location and RCTD show robust performance not only on transcriptomic data but also when applied to spatial chromatin accessibility data, achieving accuracy comparable to RNA-based deconvolution [40].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Understanding the core computational workflows of each algorithm is essential for selecting the appropriate method and interpreting its results.

Core Computational Workflows

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental steps shared by reference-based deconvolution methods.

Each method then processes the preprocessed data through its unique model, as detailed below.

Cell2location is a Bayesian model that uses negative binomial regression to model the observed spatial data. It takes as input a single-cell reference to learn cell-type-specific "signatures" and then infers the absolute abundance of each cell type in each spatial location [40] [41]. Its key output is a posterior distribution of cell-type abundances.

RCTD (Robust Cell Type Decomposition) is a probabilistic model that assumes spot counts follow a Poisson distribution. It uses maximum likelihood estimation to determine the cell-type composition of each spot and can operate in a "full" mode that accounts for multiple cell types per spot or the presence of unseen cell types [40] [41].

Tangram is a deep learning method that aligns single-cell profiles to spatial data by optimizing a mapping function. Its core principle is to arrange the single-cell data in space so that the gene expression of the mapped cells maximally matches the spatial data, measured by cosine similarity. It outputs a probabilistic matrix linking every single cell to every spatial voxel [42] [43].

SpatialDWLS employs a two-step process. It first uses non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) to cluster the spatial data and identify marker genes. Then, it applies a dampened weighted least squares (DWLS) algorithm to deconvolve the spots, which is particularly designed to handle the sparsity of gene expression data [40] [39].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successfully performing spatial deconvolution requires a pipeline of data processing and analysis tools. The table below lists key "research reagents" in the form of software and data resources.

| Item Name | Function / Application in Deconvolution |

|---|---|