Leveraging Strand-Specific RNA-Seq for Precise Viral RNA Editing Detection

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying strand-specific RNA sequencing to detect and quantify viral RNA editing.

Leveraging Strand-Specific RNA-Seq for Precise Viral RNA Editing Detection

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying strand-specific RNA sequencing to detect and quantify viral RNA editing. It covers foundational principles, including the critical advantage of resolving ambiguous reads from overlapping viral and host transcripts. The content details robust methodological pipelines, such as the dUTP protocol, for accurate application in virology. It further addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges and explores advanced validation techniques and comparative analyses against non-stranded approaches. By synthesizing these core intents, this resource empowers scientists to implement this powerful methodology, enhancing the accuracy of discoveries in viral pathogenesis and host-pathogen interactions.

The Critical Role of Strand-Specificity in Resolving Viral and Host Transcriptomes

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has emerged as a cornerstone technology in modern biology and clinical science, enabling comprehensive analysis of gene expression, transcript architecture, and functional genomics [1]. Within this field, the distinction between strand-specific (directional) and non-stranded (conventional) library preparation methods represents a critical methodological choice with profound implications for data accuracy and biological interpretation. Strand-specific RNA-seq deliberately preserves information about which genomic strand the original RNA transcript originated from, while non-stranded protocols lose this directional information during cDNA library construction [2] [3]. This preservation of strand information is not merely a technical detail but a fundamental requirement for accurate transcriptome analysis, particularly in complex genomes where overlapping transcripts, antisense regulation, and complex transcriptional architectures are common [4] [5].

The significance of strand-specific protocols extends to specialized research applications, including viral RNA editing detection research where precise mapping of viral transcripts and their editing patterns is essential. For researchers investigating viral RNA editing, strand-specific approaches enable unambiguous identification of RNA editing sites and accurate quantification of viral transcript isoforms without confusion from antisense transcripts or overlapping genes [6]. As the field progresses toward more sophisticated transcriptomic analyses, understanding and implementing strand-specific methodologies becomes increasingly vital for generating biologically meaningful results that accurately reflect the complexity of transcriptional regulation in both host and viral genomes.

Fundamental Concepts: How Strand-Specific RNA-Seq Works

The Technical Basis of Strand Information Loss and Preservation

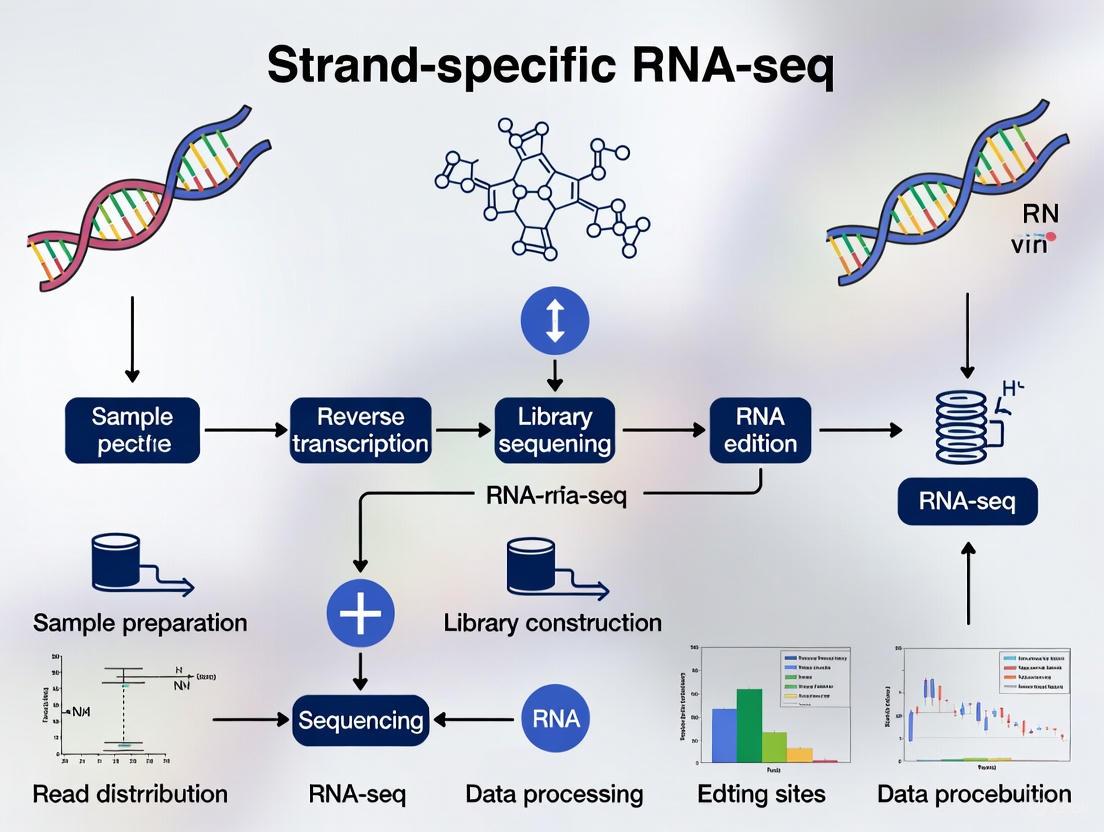

In conventional non-stranded RNA-seq protocols, the process of converting single-stranded RNA into double-stranded cDNA for sequencing results in the complete loss of information regarding the original transcriptional strand. This occurs because random primers are used for both first- and second-strand cDNA synthesis, and the resulting sequencing products from sense and antisense transcripts become indistinguishable [3]. As illustrated in Figure 1, when two antisense transcripts from the same genomic locus undergo non-stranded library preparation, the final sequencing products are identical, making it impossible to determine the directionality of the original transcript directly from the sequencing data.

Figure 1: Comparison of stranded and non-stranded library preparation protocols

Principal Strand-Specific Methodologies

Several technical approaches have been developed to preserve strand information during RNA-seq library preparation, with the dUTP second strand marking method emerging as one of the most widely adopted and effective protocols [4] [5]. This method incorporates deoxyuridine triphosphate (dUTP) instead of deoxythymidine triphosphate (dTTP) during second-strand cDNA synthesis, effectively "labeling" the second strand. Prior to PCR amplification, the uracil-containing second strand is selectively degraded using Uracil-DNA Glycosylase (UDG), ensuring that only the first strand (complementary to the original RNA transcript) is amplified [3] [5]. This elegant biochemical approach preserves the strand orientation of the original RNA molecule throughout the sequencing process.

Alternative strand-specific methods include ligation-based approaches that attach asymmetric adapters to the 5' and 3' ends of RNA fragments before cDNA synthesis, directly preserving orientation information [4]. Another class of methods employs chemical modification of the RNA template itself, such as bisulfite treatment, to distinguish between the original strands [4]. Comparative evaluations have consistently identified the dUTP method as superior in terms of simplicity, strand specificity, data quality, and compatibility with downstream applications like paired-end sequencing [4] [5]. The robustness of the dUTP method is further demonstrated by its adoption in numerous commercial strand-specific library preparation kits, making it accessible to researchers across diverse biological disciplines.

Quantitative Comparison: Performance Metrics of Stranded vs Non-Stranded Approaches

Experimental Performance Benchmarks

Rigorous comparative analyses have quantified the performance differences between stranded and non-stranded RNA-seq approaches across multiple metrics. These comparisons reveal substantial advantages for strand-specific protocols in accurately capturing the true complexity of transcriptomes. Table 1 summarizes key performance characteristics derived from experimental comparisons.

Table 1: Performance comparison between stranded and non-stranded RNA-seq protocols

| Performance Metric | Non-Stranded Protocol | Stranded Protocol | Impact on Data Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strand Specificity | 0% (inherently unstranded) | 97.4% [5] | Stranded enables correct strand assignment |

| Ambiguous Read Mapping | 6-30% of reads become ambiguous [2] | <3% ambiguous mapping | Drastic reduction in misassignment |

| Antisense Detection | Compromised or impossible | 1.5% of gene-mapping reads [7] | Enables comprehensive regulatory analysis |

| Ribosomal RNA Retention | ~7% with polyA selection [7] | Varies with depletion method | Method-dependent, not strandedness-dependent |

| Library Complexity | 88% unique paired-reads (control) [4] | 84% unique paired-reads (dUTP) [4] | Comparable performance |

| Differential Expression Accuracy | Higher false positives (>10%) and false negatives (>6%) [2] | Significant reduction in errors | More reliable differential expression calls |

Impact on Read Assignment and Transcript Quantification

The quantitative differences between stranded and non-stranded protocols have direct implications for transcript quantification and differential expression analysis. In non-stranded protocols, 28% of reads that were ambiguously mapped in unstranded workflows can be correctly reassigned to their proper transcriptional strand using strand-specific methods [2]. This dramatic improvement in mapping accuracy directly translates to more reliable gene expression estimates, particularly for genes with overlapping transcripts, antisense regulation, or complex genomic contexts.

The ability to accurately detect and quantify antisense transcription represents another significant advantage of strand-specific protocols. In comparative studies, stranded libraries identified approximately 20% more genes expressing antisense signal despite having lower read depth and higher ribosomal RNA retention compared to non-stranded approaches [7]. This enhanced sensitivity to antisense transcription is particularly valuable for viral RNA editing research, where comprehensive profiling of all viral transcripts is essential for understanding editing mechanisms and their functional consequences.

Practical Implementation: Strand-Specific Protocol for Viral RNA Editing Research

Detailed dUTP Protocol for Strand-Specific Library Construction

The following protocol outlines the key steps for implementing the dUTP-based strand-specific RNA-seq method, with particular considerations for viral RNA editing detection research:

RNA Isolation and Quality Control: Extract total RNA from infected cells or clinical samples using appropriate isolation methods. Assess RNA quality using capillary electrophoresis (e.g., Bioanalyzer RNA Integrity Number). Minimum requirement: RIN > 8.0 for optimal library construction.

Ribosomal RNA Depletion: Treat 100-1000 ng of total RNA with ribosomal depletion reagents (e.g., RiboZero Gold) rather than polyA selection to capture both polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated viral transcripts. Note: RiboZero demonstrates superior ribosomal depletion (<2.5% rRNA retention) compared to alternative methods (~65% retention) [5].

RNA Fragmentation: Fragment purified RNA to 200-300 nucleotides using metal-induced hydrolysis (e.g., magnesium buffer at 94°C for 5-15 minutes). Optimal fragmentation prevents bias in transcript coverage.

First-Strand cDNA Synthesis: Synthesize first-strand cDNA using random hexamers and reverse transcriptase with addition of Actinomycin D to prevent spurious DNA-dependent synthesis. Include purification steps to remove reagents before proceeding.

Second-Strand Synthesis with dUTP Incorporation: Perform second-strand synthesis using DNA Polymerase I with dUTP substituted for dTTP in the nucleotide mix. This creates the strand-specific marking essential for downstream directional information.

End Repair, A-Tailing, and Adapter Ligation: Process double-stranded cDNA using standard library preparation techniques, ensuring compatible adapters for your sequencing platform.

Uracil Digestion and Strand Selection: Treat with Uracil-DNA Glycosylase (UDG) to selectively degrade the dUTP-marked second strand, preserving only the original strand-complementary cDNA.

Library Amplification and Quality Control: Amplify the strand-selected library with 10-15 PCR cycles using proofreading polymerases. Validate library quality by capillary electrophoresis and quantify using fluorometric methods.

Special Considerations for Viral RNA Editing Studies

For research specifically focused on viral RNA editing detection, several modifications to the standard strand-specific protocol enhance sensitivity and accuracy:

Selective Enrichment for Viral Transcripts: Implement sequence-specific capture probes to enrich for viral RNAs, which often represent a small fraction of the total transcriptome in infected cells.

Controls for Editing Validation: Include synthetic RNA standards with known editing patterns to quantify detection sensitivity and specificity.

Duplicate Management: Monitor PCR duplication rates carefully, as these can be elevated in low-input protocols (approximately 20% in some kits) [7]. Utilize unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to distinguish biological variants from technical artifacts.

Computational Pipeline Selection: Employ specialized bioinformatics tools like CADRES (Calibrated Differential RNA Editing Scanner) that combine sophisticated DNA/RNA variant calling with statistical analysis of editing depth to distinguish genuine RNA editing events from sequencing artifacts and DNA mutations [6].

Essential Reagents and Research Solutions

Table 2: Essential research reagents for strand-specific RNA-seq

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Protocol | Considerations for Viral RNA Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library Prep Kits | Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA, Takara Bio SMARTer Stranded Total RNA-Seq | Provides complete reagent systems | Select based on input requirements: TruSeq (100ng-1μg), SMARTer (1ng-10ng) [7] |

| Ribosomal Depletion Kits | RiboZero Gold, RiboMinus | Removes ribosomal RNA without polyA bias | RiboZero more effective (2.24% rRNA vs 65.7%) [5]; essential for non-polyadenylated viral RNAs |

| Strand-Specific Enzymes | Uracil-DNA Glycosylase (UDG) | Digests dUTP-marked second strand | Critical for strand selection; quality affects specificity |

| Reverse Transcriptase | SuperScript IV, Maxima H- | Synthesizes first-strand cDNA | High processivity improves coverage of structured viral RNA regions |

| RNA QC Instruments | Agilent Bioanalyzer, Fragment Analyzer | Assesses RNA integrity | Essential for input quality control; RIN >8.0 recommended |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers | UMIs (various vendors) | Tags individual molecules pre-amplification | Critical for distinguishing true biological variants from artifacts in viral populations |

Computational Analysis Considerations for Strand-Specific Data

Specialized Bioinformatics Approaches

The analysis of strand-specific RNA-seq data requires appropriate computational tools and parameters to fully leverage the preserved directional information. Modern aligners like STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) demonstrate superior performance for stranded data, mapping >94% of quality-trimmed reads with significantly faster processing times compared to alternatives like TopHat2 [5]. When using such tools, researchers must specify the correct library type parameter (e.g., "--outSAMstrandField intronMotif" for STAR) to ensure proper interpretation of strand information.

For viral RNA editing detection, specialized variant calling approaches are essential to distinguish genuine RNA editing events from DNA mutations and technical artifacts. Pipelines like CADRES implement sophisticated statistical frameworks that combine DNA and RNA sequencing data to identify differential RNA editing sites with high specificity [6]. These tools utilize a two-phase approach: first comparing genomic DNA and cDNA sequences to filter DNA variants, then applying statistical tests (e.g., Generalized Linear Mixed Models) to identify sites showing significant differences in editing levels across experimental conditions.

Data Quality Assessment Metrics

Quality control for strand-specific libraries should include verification of strand specificity through metrics that quantify the percentage of reads aligning to the expected transcriptional strand. High-quality dUTP libraries typically achieve >97% strand specificity [5]. Additional QC measures should include:

- Library complexity assessment to identify potential amplification biases

- Gene body coverage uniformity evaluation

- Ribosomal RNA contamination quantification (<5% ideal)

- Transcript assembly completeness using benchmarking tools

Strand-specific RNA-seq represents a fundamental methodological advancement over non-stranded approaches, providing critical transcriptional strand information that dramatically improves the accuracy of transcript quantification, annotation, and discovery. For viral RNA editing research, these protocols enable unambiguous identification of viral transcripts, precise mapping of editing sites, and comprehensive profiling of antisense transcription that may play important regulatory roles in the viral life cycle.

The implementation of robust strand-specific methods, particularly the dUTP-based protocol, combined with appropriate computational approaches like CADRES for editing detection, provides a powerful framework for investigating the complex landscape of viral RNA modifications. As the field continues to evolve, strand-specific RNA-seq will remain an essential tool for unraveling the mechanistic basis of RNA editing in viral pathogenesis and developing novel therapeutic strategies targeting these processes.

In virology, accurately interpreting the complex life cycles and regulatory mechanisms of viruses depends on obtaining complete and unambiguous transcriptomic data. A fundamental technical aspect, strand-specific RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), is non-negotiable for distinguishing the true nature of viral transcription, especially when investigating overlapping genes and pervasive antisense transcription. Non-stranded, or unstranded, RNA-seq protocols discard the information about which genomic strand an RNA molecule originated from, leading to significant ambiguities in data interpretation [8] [2].

This ambiguity is particularly problematic for RNA viruses, where the distinction between genomic and antigenomic strands is critical, and for DNA viruses with overlapping gene architectures. Preserving strand information is essential for accurately identifying authentic RNA editing events, such as Adenosine-to-Inosine (A-to-I) editing, which appears as A-to-G changes in sequencing reads and requires strand-specific data to distinguish from other mutations like single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or replication errors [8]. This application note details the methodologies and experimental protocols that leverage strand-specific RNA-seq to drive precise viral discovery.

Quantitative Impact of Strand-Specific Protocols

The choice between stranded and unstranded library preparation has a direct and measurable impact on data quality and biological interpretation. The table below summarizes key quantitative comparisons.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Strand-Specific RNA-Seq in Transcriptomic Analysis

| Metric | Unstranded Protocol | Strand-Specific Protocol | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ambiguous Read Mapping | 6–30% of reads become ambiguous [2] | Ambiguity reduced by ~50% or more [2] | Drastically improved accuracy of transcript assignment and quantification. |

| False Positives in Differential Expression | Can inflate false positives by >10% [2] | Significantly reduced false positive rates [2] | More reliable identification of truly regulated genes and transcripts. |

| False Negatives in Differential Expression | Can inflate false negatives by >6% [2] | Significantly reduced false negative rates [2] | Enhanced sensitivity to detect subtle but biologically relevant expression changes. |

| Detection of Antisense Transcription | Often hidden or misinterpreted as sense signal [9] [2] | Enables clear identification and quantification [9] [2] | Unlocks the study of a crucial layer of viral and host gene regulation. |

| Identification of RNA Editing (e.g., A-to-I) | Compromised; cannot distinguish from SNP/ replication errors [8] | Enabled; A-to-G variation is specific to one strand [8] | Allows for validation of true RNA editing events in host-virus interactions. |

Core Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Strand-Specific Library Preparation: The dUTP Second Strand Marking Method

The dUTP/Uracil DNA Glycosylase (UDG) method is a widely adopted and robust protocol for creating strand-specific RNA-seq libraries [10] [2].

Workflow Overview:

- RNA Fragmentation and First-Strand cDNA Synthesis: Isolated total or mRNA is fragmented and reverse-transcribed using random primers. This produces the first-strand cDNA, which is complementary to the original RNA template.

- Second-Strand Synthesis with dUTP Incorporation: The RNA template is degraded, and the second DNA strand is synthesized. The reaction mixture substitutes dTTP with dUTP. This results in a double-stranded cDNA molecule where the second strand contains uracil.

- Adapter Ligation and UDG Digestion: Double-stranded adapters are ligated to the cDNA ends. The library is then treated with Uracil DNA Glycosylase (UDG), which specifically digests the uracil-containing second strand.

- PCR Amplification: Only the original first strand remains as a template for PCR amplification, ensuring that every sequenced read retains the strand-of-origin information.

Diagram Title: Strand-Specific RNA-seq Library Prep (dUTP Method)

Validating RNA Editing in Viral Transcriptomes

Distinguishing true RNA editing from SNPs or sequencing errors is a major challenge. Strand-specific sequencing is a foundational step in a multi-tiered validation workflow [8] [11].

Recommended Validation Workflow:

In Silico Analysis:

- Prerequisite: Begin with strand-specific RNA-seq data to ensure A-to-G variations are genuine and not an artifact of symmetrical T-to-C variations from non-stranded data [8].

- Linkage Analysis: Analyze the linkage between variations in RNA-seq reads. True RNA editing events may show partial linkage due to the properties of the editing enzyme (ADAR), whereas SNPs are strongly linked, and sequencing errors are random [8].

- Hyperediting Pipeline: Use specialized bioinformatic pipelines (e.g., "hyperediting" tools) to detect clusters of editing events within single reads, which are strong indicators of authentic ADAR activity [8].

Orthogonal Experimental Validation:

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): Use MS to detect peptides with amino acid changes corresponding to the RNA-level edit (e.g., a lysine to arginine change for an A-to-I edit in a coding region). This provides direct protein-level validation [8].

- Use of ADAR-Deficient Cells: Repeat infection experiments in host cells where ADAR enzymes have been knocked out or knocked down. A significant reduction in A-to-G variations in the viral transcriptome provides functional evidence that the changes were ADAR-mediated editing events [8].

Diagram Title: RNA Editing Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of strand-specific virology studies requires a suite of trusted reagents and computational tools.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Strand-Specific Viral Transcriptomics

| Item/Category | Function/Description | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Stranded RNA Library Prep Kits | Commercial kits implementing dUTP or ligation-based methods for strand preservation. | Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep, NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit. Foundation for all downstream analysis. |

| Ribodepletion Reagents | Kits to remove ribosomal RNA (rRNA), crucial for viruses lacking poly-A tails or for studying non-coding RNAs. | Ribo-Zero Plus (Illumina), NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit. Analysis of total viral RNA content. |

| ADAR-Deficient Cell Lines | Genetically engineered host cells (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9 KO) lacking RNA editing enzymes. | Functional validation of A-to-I editing events in viral RNAs [8]. |

| Reverse Genetics Systems | Platforms for generating recombinant viruses from cDNA. | To study the functional impact of specific RNA editing sites or disrupted antisense transcripts by introducing mutations into viral genomes. |

| Computational Tools: Hyperediting Pipelines | Specialized software to detect clusters of RNA editing events within single reads. | Validation of authentic ADAR activity in viral sequence data [8]. |

| Computational Tools: Graph-based Visualizers | Tools like Graphia Professional for visualizing complex RNA-seq assembly graphs and splice variants. | Resolving complex viral transcript architectures and overlapping units [12]. |

| Rosiglitazone potassium | Rosiglitazone potassium, CAS:316371-84-3, MF:C18H18KN3O3S, MW:395.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Folipastatin | Folipastatin|SOAT/PLA2 Inhibitor|For Research | Folipastatin, a depsidone fromAspergillus unguis, is a SOAT and phospholipase A2 inhibitor with antibiotic activity. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Visualizing Complex Viral Transcription Architectures

Overlapping genes are a common feature in viral genomes, used to maximize the coding capacity of a compact genome. Resolving these structures requires precise strand-of-origin data.

Diagram Title: Resolving Overlapping Viral Genes with Strand-Specific Data

Concluding Recommendations

For the virology research community, adopting strand-specific RNA-seq is a critical best practice. It is no longer a specialized option but a fundamental requirement for studies aiming to:

- Accurately quantify gene expression from viral and host genomes.

- Discover and characterize overlapping genes and antisense transcripts, which are widespread in viruses [13].

- Validate authentic RNA editing events and distinguish them from replication errors [8].

- Build robust and reproducible models of viral transcription and host-virus interactions.

The slight increase in protocol complexity and cost is vastly outweighed by the dramatic gain in data clarity, accuracy, and biological insight. For any investigative study of viral transcriptomics, strand information is non-negotiable.

In standard RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), the process of creating cDNA libraries loses a critical piece of information: which original genomic strand transcribed the RNA. This occurs because synthesis of randomly primed double-stranded cDNA, followed by adapter addition for next-generation sequencing, does not preserve the strand of origin [4] [14]. Strand-specific RNA-seq protocols solve this fundamental problem by deliberately preserving the orientation information of the original RNA transcript throughout the library preparation and sequencing process [2].

For researchers investigating viral RNA editing, this capability is not merely a technical refinement but a necessity for accurate biological interpretation. Preserving strand orientation allows scientists to correctly assign reads to sense or antisense transcripts, resolve overlapping genes, and accurately quantify gene expression—all essential for understanding viral pathogenesis and host-response mechanisms [2] [14]. Without strand information, distinguishing viral RNA editing events from transcriptional artifacts or antisense interference becomes significantly challenging, potentially leading to incorrect biological conclusions [2] [11].

Core Methodological Principles

Strand-specific RNA-seq methods employ distinct biochemical strategies to mark the original transcript strand, with two primary classes emerging as the most prevalent and reliable.

The dUTP Second-Strand Marking Method

The dUTP method has been extensively validated and identified as a leading protocol due to its robust performance and simplicity [4] [14]. This approach incorporates deoxyuridine triphosphate (dUTP) during second-strand cDNA synthesis, followed by enzymatic degradation of the uracil-containing strand before PCR amplification [14] [15]. The step-by-step mechanism operates as follows:

- First-Strand cDNA Synthesis: Reverse transcriptase generates the first cDNA strand complementary to the original RNA template using random hexamers or oligo(dT) primers.

- Second-Strand Synthesis with dUTP: DNA polymerase I synthesizes the second strand using deoxyadenosine, deoxyguanosine, deoxycytidine, and deoxyuridine triphosphates (dATP, dGTP, dCTP, dUTP) instead of thymidine triphosphate (dTTP) [15].

- Uracil-Containing Strand Degradation: Prior to PCR amplification, the enzyme Uracil-N-Glycosylase (UNG) recognizes and selectively degrades the second strand containing uracil bases [15].

- Library Amplification: Only the first strand (complementary to the original RNA) serves as a template for PCR amplification, ensuring all sequenced fragments maintain the correct orientation relative to the transcript of origin.

Table 1: Key Steps and Rationale of the dUTP Strand-Specific Method

| Step | Key Components | Biochemical Function | Strand Preservation Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-Strand Synthesis | Reverse transcriptase, dNTPs | Creates cDNA complement to RNA | Establishes complementary copy of original transcript |

| Second-Strand Synthesis | DNA polymerase I, dATP/dGTP/dCTP/dUTP | Replaces dTTP with dUTP in new strand | Labels newly synthesized strand for subsequent removal |

| Strand Degradation | Uracil-N-Glycosylase (UNG) | Enzymatically cleaves uracil-containing DNA | Eliminates second strand; only original complement remains |

| Library Amplification | DNA polymerase, PCR primers | Amplifies remaining first strand | Ensures all sequenced fragments maintain correct orientation |

The Directional Ligation Method

An alternative strategy relies on asymmetric adapter ligation to preserve strand information. This class of methods attaches distinct adapters to the 5' and 3' ends of cDNA fragments in a known orientation relative to the original RNA transcript [4]. Commercial implementations like the Swift and Swift Rapid kits employ "Adaptase" technology to directly ligate truncated adapters to single-stranded cDNA, eliminating the need for second-strand synthesis altogether [16]. The sequential logic of this approach includes:

- First-Strand Synthesis: Generation of cDNA from RNA templates.

- Asymmetric Adapter Ligation: Specific, non-interchangeable adapters are ligated to the 5' and 3' ends of the cDNA, maintaining the transcriptional orientation.

- Library Amplification: PCR amplification using primers complementary to the distinct adapters preserves the strand-of-origin information throughout sequencing.

Quantitative Impact on Data Accuracy

The choice between stranded and non-stranded protocols substantially influences downstream analytical outcomes, with stranded protocols providing demonstrably superior accuracy.

Resolution of Ambiguous Mappings

In complex transcriptomes where genes overlap on opposite strands, non-stranded RNA-seq cannot determine the transcriptional origin of reads, leading to ambiguous mappings. Research demonstrates that in the human genome, approximately 19% (about 11,000 genes) overlap with other genes transcribed from the opposite strand [14]. Empirical RNA-seq data reveals that stranded protocols reduce ambiguous read assignments by approximately 3.1% compared to non-stranded approaches [14]. This reduction directly corresponds to the resolution of gene overlap from opposite strands, enabling more precise quantification.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Stranded vs. Non-Stranded RNA-seq

| Metric | Non-Stranded RNA-seq | Stranded RNA-seq | Experimental Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ambiguous Reads | ~6.1% | ~2.94% | Whole blood mRNA-seq analysis [14] |

| Opposite Strand Overlap | Cannot be resolved | Fully resolved | Theoretical & empirical analysis [14] |

| Gene Expression Accuracy | Compromised for ~28% of ambiguous reads | Significantly improved | Human fibroblast benchmark [2] |

| Antisense Transcription Detection | Limited or impossible | Enabled | Evaluation of regulatory RNAs [2] [14] |

Enhanced Detection Capabilities

Strand-specific protocols unlock critical biological insights by enabling accurate detection of antisense transcription, which plays important regulatory roles in both cellular and viral systems [2] [14]. Studies have demonstrated that without strand information, antisense long non-coding RNAs can be misinterpreted as increased sense transcription or remain entirely undetected [2]. In viral research, this capability is particularly valuable for identifying antisense transcripts that may regulate viral persistence, latency, or reactivation.

Application in Viral RNA Editing Research

For viral RNA editing detection, strand-specific protocols provide essential experimental safeguards against misinterpretation.

The CADRES pipeline, designed for precise identification of RNA editing sites, emphasizes that comparing DNA and RNA sequences while assessing differential editing levels across conditions is crucial for distinguishing true RNA editing events from DNA mutations or sequencing artifacts [6]. Strand-specific sequencing enhances this discrimination by correctly identifying the transcribed strand, reducing false positives in editing detection.

Guidelines for RNA editing studies specifically recommend careful consideration of strand specificity in experimental design to avoid misinterpreting sequencing artifacts as genuine editing events [11]. This is particularly relevant for detecting C-to-U editing mediated by APOBEC enzymes, which can play significant roles in host-viral interactions [6].

Experimental Protocol: dUTP Method for Strand-Specific RNA-seq

Sample Preparation and RNA Isolation

- Starting Material: Extract total RNA using appropriate isolation methods (e.g., Trizol for tissues, column-based methods for cells). For viral studies, include appropriate biosafety precautions.

- RNA Quality Assessment: Determine RNA Integrity Number (RIN) using Agilent Bioanalyzer or similar platform. Use only high-quality RNA (RIN > 8.0) for library construction.

- PolyA+ RNA Selection: Isolate polyadenylated RNA using oligo(dT) magnetic beads according to manufacturer protocols. This enriches for mRNA while depleting ribosomal RNA [15].

Strand-Specific Library Construction

First-Strand cDNA Synthesis:

- Combine 0.5-1μg polyA+ RNA with random hexamer and oligo(dT) primers in reverse transcription buffer containing dNTPs and DTT [15].

- Add actinomycin D to inhibit spurious DNA-dependent synthesis [4].

- Incorporate SuperScript III reverse transcriptase and perform first-strand synthesis with temperature cycling (25°C for 10 min, 42°C for 45 min, 50°C for 25 min) [15].

Second-Strand Synthesis with dUTP Incorporation:

- Purify first-strand cDNA using gel filtration spin columns to remove dNTPs.

- Perform second-strand synthesis using E. coli DNA polymerase I and RNase H in buffer containing dATP, dGTP, dCTP, and dUTP (replacing dTTP) [15].

- Incubate at 16°C for 2 hours, then purify double-stranded cDNA using QIAquick columns.

Library Preparation and Uracil Strand Degradation:

- Fragment dsDNA by sonication or enzymatic methods to ~200-300bp.

- Repair DNA ends and add 'A' bases to 3' ends following standard Illumina library protocols.

- Critical Step: Before PCR amplification, treat with Uracil-N-Glycosylase (UNG) at 37°C for 15 minutes to degrade the dUTP-marked second strand [15].

- Perform PCR amplification with Illumina indexing primers to create the final sequencing library.

Quality Control and Sequencing

- Library QC: Assess library quality and concentration using Bioanalyzer and qPCR methods.

- Sequencing: Utilize Illumina platforms with recommended read lengths (2×100bp or 2×150bp) and appropriate sequencing depth (typically 20-40 million reads per sample for viral transcriptomes).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Strand-Specific RNA-seq Library Construction

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Reverse Transcriptase | SuperScript III, SuperScript IV | Synthesizes first-strand cDNA from RNA templates with high fidelity and processivity |

| Nucleotide Mixes | dATP, dGTP, dCTP, dUTP | dUTP substitutes for dTTP in second-strand synthesis to enable strand marking |

| Strand-Degrading Enzymes | Uracil-N-Glycosylase (UNG) | Recognizes and cleaves uracil-containing DNA strands for selective removal |

| Second-Strand Synthesis Enzymes | DNA Polymerase I, RNase H | Synthesizes the second cDNA strand while degrading the RNA template |

| Library Preparation Kits | Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA, SMARTer Stranded Total RNA | Commercial kits that incorporate dUTP or ligation-based strand marking |

| RNA Selection Beads | Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads | Enriches polyadenylated mRNA from total RNA inputs |

| Library Amplification | Illumina Indexing Primers, PCR Master Mix | Amplifies final strand-specific libraries with unique sample indexes |

| N-phenylacetyl-L-Homoserine lactone | N-phenylacetyl-L-Homoserine lactone, MF:C12H13NO3, MW:219.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 8,11-Eicosadiynoic acid | 8,11-Eicosadiynoic acid, CAS:82073-91-4, MF:C20H32O2, MW:304.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete dUTP-based strand-specific RNA-seq workflow:

Strand-specific RNA-seq protocols, particularly the dUTP method, provide an essential foundation for accurate transcriptome characterization by preserving the strand origin of sequenced fragments. For viral RNA editing research, this capability is indispensable for correctly identifying editing events, resolving complex transcriptional overlaps, and detecting regulatory antisense transcripts. The methodological rigor afforded by strand-specific approaches significantly enhances data interpretation reliability, enabling more confident conclusions about viral pathogenesis and host-response mechanisms. As transcriptomic analyses continue to advance, adopting strand-specific protocols as a standard practice ensures maximal biological insight from RNA-seq experiments.

Strand-specific RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) is a powerful advancement in transcriptome analysis that preserves the original orientation of RNA transcripts. Among various methods, the dUTP second-strand marking technique has emerged as a leading protocol, particularly for applications requiring high accuracy in transcript annotation and detection of antisense transcription. This is especially critical in viral RNA editing research, where distinguishing the true strand origin of RNA molecules is essential for accurately identifying host-driven RNA editing events, such as adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) deamination, and for resolving complex viral transcriptomes. The dUTP method, recognized for its robust performance and compatibility with standard Illumina sequencing platforms, provides the strand specificity necessary to overcome the fundamental limitations of non-stranded approaches [17] [4] [14].

Principles of the dUTP Strand-Specific RNA-Seq

The core principle of the dUTP method lies in the biochemical labeling and subsequent selective degradation of the second cDNA strand, thereby preserving only the first strand that is complementary to the original RNA template for sequencing. This process ensures that the resulting sequence reads can be unambiguously mapped to their strand of origin.

In a standard non-stranded RNA-Seq protocol, double-stranded cDNA is synthesized from RNA templates, and both strands are sequenced without retaining information about which strand was originally transcribed. This leads to a significant challenge: when a genomic locus has genes on both strands, it becomes impossible to determine from which strand a particular read originated [14] [3]. The dUTP method solves this by incorporating deoxyuridine triphosphate (dUTP) instead of deoxythymidine triphosphate (dTTP) during the synthesis of the second cDNA strand. This incorporation "marks" the second strand. Prior to the final PCR amplification, the enzyme Uracil-DNA-Glycosylase (UDG) is used to specifically degrade the uracil-containing second strand. Consequently, only the first strand is amplified and sequenced, preserving the strand information of the original mRNA throughout the entire process [17] [18].

Comparative Performance of Strand-Specific Protocols

A comprehensive comparative analysis of seven strand-specific RNA-Seq protocols identified the dUTP method as one of the top-performing approaches. The evaluation used the well-annotated S. cerevisiae transcriptome as a benchmark and assessed methods based on critical quality metrics [4].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Leading Strand-Specific RNA-Seq Methods

| Performance Metric | dUTP Method | Illumina RNA Ligation Method | Standard Non-Stranded Method (Control) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strand Specificity | High (Exact values provided in [4]) | High | Not Applicable |

| Library Complexity (Paired-end) | 84% unique paired-reads | Not detailed for paired-end | 88% unique paired-reads |

| Evenness of Coverage | High agreement with known annotations | High agreement with known annotations | Baseline |

| Quantitative Accuracy | Accurate for expression profiling | Accurate for expression profiling | Baseline |

| Ease of Use | Relatively simple protocol | Requires specialized RNA adaptors | Simplest protocol |

This analysis concluded that the dUTP method and the Illumina RNA ligation method were the leading protocols. The dUTP method was particularly favored because it benefits from the availability of paired-end sequencing, which provides more accurate library complexity measurements and better resolution of transcript isoforms [4].

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

The following section details a modified dUTP protocol compatible with the Illumina TruSeq kit, enabling robust strand-specific library construction within two days [17] [18].

RNA Isolation and mRNA Enrichment

Begin with high-quality total RNA (0.1–4 μg). Isate the polyadenylated (polyA) mRNA fraction using oligo(dT) magnetic beads. This enrichment step is typical for standard RNA-Seq and focuses the sequencing on protein-coding transcripts [17] [19].

RNA Fragmentation and First-Strand Synthesis

Chemically fragment the purified mRNA to the desired size distribution (e.g., 200-300 bp). Use random hexamer primers and reverse transcriptase to synthesize the first-strand cDNA. This first strand is complementary to the original RNA template [17].

Second-Strand Synthesis with dUTP Incorporation

Synthesize the second strand of cDNA using a reaction mix where dTTP is replaced with dUTP. This creates a double-stranded cDNA product where the second strand is biochemically marked with uracil, while the first strand contains thymine [17] [18].

End-Repair, A-Tailing, and Adapter Ligation

Process the double-stranded cDNA fragments following a standard Illumina library preparation workflow:

- End-Repair: Convert the fragmented cDNA ends to blunt ends.

- A-Tailing: Add a single 'A' nucleotide to the 3' ends to facilitate ligation to the 'T'-overhang of Illumina adapters.

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate indexed sequencing adapters to the cDNA fragments [17].

Strand Selection via UDG Digestion and Size Selection

This is the critical, strand-defining step. Incubate the adapter-ligated library with Uracil-DNA-Glycosylase (UDG). This enzyme selectively degrades the second cDNA strand that contains uracil. The result is a library consisting only of the first-strand cDNA molecules [17] [18]. Finally, perform size selection (e.g., using gel electrophoresis or SPRI beads) to isolate cDNA fragments of the desired length for sequencing [17] [4].

Library Amplification and Quantification

Perform a limited-cycle PCR to amplify the remaining strand-specific library. Purify the final library and quantify it using methods such as qPCR or bioanalyzer before sequencing on an Illumina platform [17].

Diagram 1: dUTP Strand-Specific RNA-Seq Workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for dUTP Strand-Specific RNA-Seq Library Construction

| Reagent / Kit | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads | Enriches for polyadenylated mRNA from total RNA. |

| Reverse Transcriptase & Random Hexamers | Synthesizes the first-strand cDNA from fragmented mRNA. |

| dNTP/dUTP Mix (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dUTP) | Incorporates dUTP instead of dTTP during second-strand synthesis to mark the strand. |

| Uracil-DNA-Glycosylase (UDG) | The key enzyme for strand selection; degrades the dUTP-marked second cDNA strand. |

| Illumina TruSeq or Compatible Kit | Provides reagents for end-repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification. |

| Size Selection Beads (e.g., SPRI beads) or Gel Matrix | Purifies and selects cDNA fragments of the desired size range for sequencing. |

| Methyl 12-methyltridecanoate | Methyl 12-methyltridecanoate, CAS:5129-58-8, MF:C15H30O2, MW:242.40 g/mol |

| Phenindamine | Phenindamine, CAS:82-88-2, MF:C19H19N, MW:261.4 g/mol |

Application in Viral RNA Editing Detection Research

The dUTP method's high strand specificity is not just a technical improvement; it is a critical requirement for accurately detecting and validating RNA editing in viruses like SARS-CoV-2.

In non-stranded RNA-Seq, an A-to-I editing event (recorded as A-to-G in the RNA) can manifest as both A-to-G variations in the sense strand and T-to-C variations in the antisense strand. This "symmetry problem" makes it impossible to distinguish true A-to-I editing from replication errors or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that are incorporated into the viral genome, as both can produce T-to-C variations [8]. Strand-specific RNA-Seq directly resolves this ambiguity. Because the protocol preserves the original RNA orientation, a true A-to-I editing event will appear exclusively as an A-to-G variation in reads originating from the sense strand. This eliminates the confounding T-to-C signal from the antisense strand, thereby significantly improving the signal-to-noise ratio in the search for authentic RNA editing sites [8].

Diagram 2: Strand-Specific RNA-Seq Resolves Ambiguity in Viral RNA Editing.

Furthermore, stranded data is essential for advanced in silico validation approaches, such as linkage analysis, which examines the co-occurrence of multiple editing events on the same RNA molecule. This analysis depends on knowing the precise strand orientation of reads to correctly establish linkage between variations [8].

Quantitative Impact on Data Accuracy

The practical advantages of stranded RNA-Seq, as enabled by the dUTP method, translate into direct, measurable improvements in data quality and interpretation.

Table 3: Impact of Stranded vs. Non-Stranded RNA-Seq on Read Assignment

| Data Attribute | Stranded RNA-Seq (dUTP) | Non-Stranded RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Percentage of Ambiguous Reads | ~2.94% (arising only from same-strand overlaps) | ~6.1% (arising from same-strand and opposite-strand overlaps) |

| Confidence in Antisense RNA Quantification | High. Enables accurate identification and quantification. | Low. Difficult to distinguish from sense transcription. |

| Accuracy for Overlapping Opposite Strand Genes | High. Correctly assigns reads to the transcribed strand. | Low. Reads are ambiguously assigned to both gene models. |

Research has demonstrated that a significant portion (approximately 19% or 11,000 genes in the Gencode annotation) of the genome consists of genes that overlap on opposite strands [14]. In non-stranded RNA-Seq, reads falling within these overlapping regions cannot be assigned confidently, leading to a higher rate of "ambiguous" reads (~6.1%) compared to stranded RNA-Seq (~2.94%). This ~3.1% drop in ambiguity directly corresponds to the resolution of overlaps from opposite strands, leading to more accurate quantification of gene expression for thousands of genes [14]. This precision is fundamental in viral research, where overlapping genes are common, and accurately determining their individual expression levels is critical for understanding viral replication and pathogenesis.

Implementing Robust Strand-Specific RNA-Seq Workflows for Viral RNA Editing

This application note provides a detailed, practical protocol for implementing a strand-specific RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) pipeline optimized for the detection and analysis of viral RNAs. Within the broader context of viral RNA editing research, maintaining strand-of-origin information is crucial for accurately distinguishing viral genomic RNA from complementary transcripts and antisense RNA species that play key regulatory roles in viral replication. The workflow encompasses every stage from initial sample preparation through computational viral read mapping, with special emphasis on experimental design considerations that enhance sensitivity for viral detection in complex biological samples. This comprehensive guide serves researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to implement robust, strand-aware sequencing approaches for virology and antiviral therapeutic development.

RNA sequencing has revolutionized transcriptome analysis, providing unprecedented resolution for studying gene expression and RNA biology. Strand-specific RNA-Seq represents a critical advancement over conventional protocols by preserving the directional origin of each transcript [20] [14]. This capability is particularly valuable in viral research, where many viruses produce overlapping and antisense transcripts that regulate infection cycles [20]. Without strand information, it is impossible to distinguish whether a read originated from the positive-sense viral genome or from a complementary negative-sense transcript, potentially leading to misinterpretation of viral gene expression and regulatory mechanisms.

The dUTP second-strand marking method has emerged as a leading protocol for stranded library preparation due to its superior performance in strand specificity and data quality [17] [14]. This technique incorporates deoxyuridine triphosphates during second-strand cDNA synthesis, enabling enzymatic degradation of this strand before amplification and ensuring that only the original RNA orientation is sequenced. For viral detection studies, this approach provides the critical advantage of unequivocally identifying the transcriptional strand origin of viral reads, which is essential for understanding viral replication dynamics and host-pathogen interactions.

Strand-Specific Library Preparation Protocol

RNA Extraction and Quality Control

The initial RNA quality fundamentally impacts downstream sequencing success and viral detection sensitivity. For studies focusing on viral transcripts, consider that some viral RNAs may be non-polyadenylated or contain unusual structural features.

- Input Material: The protocol typically requires 25 ng - 1 µg of total RNA as starting material [21]. When working with viral samples, the input amount may need optimization based on expected viral RNA abundance.

- RNA Integrity: Assess RNA quality using the RNA Integrity Number (RIN), with values >7.0 generally recommended for high-quality sequencing [21]. However, for samples with expected high degradation (such as clinical specimens), ribosomal RNA depletion may be preferable to polyA selection.

- Quality Metrics: Evaluate 260/280 and 260/230 ratios to ensure minimal protein or chemical contamination. Visual inspection of electropherograms from Bioanalyzer or TapeStation systems should show distinct ribosomal peaks.

For viral detection in biologics, efficient nucleic acid extraction is critical, particularly for breaking down viral envelopes and capsids to release viral RNA [22] [23]. The extraction method should be validated for the specific virus targets of interest, as recovery efficiency varies significantly among viruses with different physicochemical properties.

rRNA Depletion and PolyA Selection Considerations

The choice between ribosomal RNA depletion and polyA enrichment significantly impacts viral detection capability:

Table 1: Comparison of RNA Selection Methods for Viral Detection

| Method | Advantages for Viral Studies | Limitations | Recommended Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| PolyA Selection | Simplifies library complexity; reduces sequencing costs; enriches for eukaryotic mRNA | May miss non-polyadenylated viral RNAs; requires intact RNA | Studies focused on host response to infection; viruses with polyA tails |

| rRNA Depletion | Retains non-polyadenylated transcripts; works with degraded RNA | Higher background; requires more sequencing depth | Discovery-oriented viral detection; surveillance of unknown viruses |

| Total RNA | Maximizes detection of all RNA species | High ribosomal content; requires extensive depletion | Comprehensive virome studies; detection of diverse viral families |

Ribosomal RNA constitutes approximately 80% of cellular RNA [21], and its removal is essential for efficient viral transcript detection. Probe-based depletion methods (e.g., RNase H-mediated degradation) show greater reproducibility compared to bead-based subtraction approaches [21]. Note that some depletion methods may inadvertently remove viral RNAs with similarity to host rRNA sequences.

Strand-Specific cDNA Library Construction

The core strand-specific protocol follows these key steps [17]:

- RNA Fragmentation: Fragment purified mRNA to 200-300 nucleotides using divalent cations under elevated temperature.

- First-Strand cDNA Synthesis: Use random hexamers and reverse transcriptase to synthesize cDNA from fragmented RNA.

- Second-Strand Synthesis with dUTP Incorporation: Incorporate dUTP instead of dTTP during second-strand synthesis, creating a strand-specific mark.

- End Repair and A-Tailing: Polish fragment ends and add single adenosine overhangs for adapter ligation.

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate platform-specific sequencing adapters to both ends of cDNA fragments.

- dUTP Strand Degradation: Treat with Uracil-DNA-Glycosylase (UDG) to selectively degrade the second strand containing uracils.

- Library Amplification: Perform limited-cycle PCR to enrich for adapter-ligated fragments.

The dUTP marking method effectively preserves strand information, with one study demonstrating a 3.1% reduction in ambiguous mappings compared to non-stranded approaches [14]. This is particularly valuable for identifying antisense viral transcripts that may regulate gene expression.

Sequencing Considerations for Viral Detection

Read Length and Depth Optimization

Sequencing parameters must balance cost with sufficient sensitivity for viral detection, particularly for low-abundance viral transcripts:

Table 2: RNA-Seq Sequencing Recommendations for Viral Detection

| Application | Recommended Read Length | Recommended Depth | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viral Gene Expression Profiling | 50-75 bp single-end | 30-60 million reads | Sufficient for quantification of moderate to high abundance viral transcripts |

| Viral Transcriptome Assembly | 75-100 bp paired-end | 100-200 million reads | Longer reads facilitate assembly of novel viral transcripts and isoforms |

| Low Abundance Viral Detection | 75-100 bp paired-end | 60-100 million reads | Increased depth enhances detection sensitivity for rare viral transcripts |

| Multiplexed Screening | 50-75 bp single-end | 5-25 million reads per sample | Cost-effective for large sample numbers when targeting high-titer viruses |

For reference, a multi-laboratory study demonstrated that 10^4 genome copies/mL of spiked viruses could be reliably detected using short-read sequencing technologies [23]. Some optimized workflows achieved detection limits as low as 10^2 genome copies/mL for certain viruses, highlighting the importance of protocol optimization.

Experimental Design and Replication

Appropriate experimental design is crucial for meaningful viral detection studies:

- Biological Replicates: A minimum of three replicates per condition is standard, though more may be needed for samples with high biological variability [24].

- Controls: Include positive controls (samples with known viral content) and negative controls (virus-free samples) to establish detection limits and specificity.

- Spike-in Controls: Consider using exogenous RNA spike-ins at known concentrations to monitor technical performance and quantitative accuracy.

The high titer of production viruses in some biological samples can create background challenges; one study successfully detected spiked adventitious viruses in backgrounds of 1-5 × 10^9 genome copies/mL of adenovirus 5 [23].

Bioinformatics Pipeline for Viral Read Mapping

Preprocessing and Quality Control

Raw sequencing data requires thorough quality assessment and cleaning before alignment:

- Quality Control: Use FastQC or multiQC to evaluate base quality scores, sequence duplication rates, adapter contamination, and overall read quality [24].

- Adapter Trimming: Remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases using tools such as Trimmomatic, Cutadapt, or fastp [24].

- Quality Filtering: Discard reads with excessive ambiguous bases or overall poor quality.

Post-trimming quality assessment ensures data meets minimum standards for downstream analysis. Over-trimming should be avoided as it reduces data quantity and can impact mapping sensitivity for divergent viruses.

Read Alignment Strategies

Two principal alignment approaches are available for viral detection:

Host Subtraction Approach: First align reads to the host reference genome (e.g., human GRCh38) using splice-aware aligners like STAR or HISAT2 [24]. Unmapped reads are then extracted and aligned to viral reference databases. This approach efficiently reduces host background but may miss viral reads with similarity to host sequences.

Direct Composite Alignment: Create a combined reference containing both host and viral genomes, then align all reads simultaneously. This approach prevents loss of viral reads that might have weak similarity to host sequences but requires more computational resources.

For strand-specific data, ensure that alignment software is configured to recognize library strandedness, typically using the "fr-firststrand" parameter in common aligners.

Viral Read Identification and Quantification

After alignment, specialized approaches are needed for viral detection:

- Reference-Based Mapping: Align to comprehensive viral databases (RVDB, RefSeq Viruses) using tools like BWA, Bowtie2, or STAR [23].

- Abundance Estimation: Use featureCounts or HTSeq-count to quantify reads mapping to viral features [24]. For strand-specific libraries, ensure counting is performed with appropriate strandness parameters.

- Threshold Determination: Establish minimum read thresholds for viral detection based on negative controls and statistical significance. The multi-laboratory study used both targeted and non-targeted bioinformatic analyses, with targeted analysis showing greater sensitivity for expected viruses [23].

Advanced approaches include de novo assembly of unmapped reads followed by BLAST comparison to viral databases, which can detect novel or highly divergent viruses not present in reference databases.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Strand-Specific Viral RNA-Seq

| Reagent/Category | Function | Examples/Options |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality RNA from various matrices | Column-based methods; magnetic bead systems |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Removal of abundant ribosomal RNA | Probe-based subtraction; RNase H-mediated degradation |

| Stranded Library Prep Kits | Construction of strand-specific cDNA libraries | dUTP-based methods; ligation-based methods |

| Sequence Adapters | Platform-specific sequences for cluster generation | Illumina TruSeq; IDT for Illumina |

| Quality Control Assays | Assessment of RNA and library quality | Bioanalyzer; TapeStation; qPCR quantification |

| Alignment Software | Mapping reads to reference sequences | STAR; HISAT2; BWA; Bowtie2 |

| Viral Reference Databases | Reference sequences for viral identification | RVDB; RefSeq Viruses; NCBI Viral Genome Database |

The implementation of a robust strand-specific RNA-Seq pipeline for viral detection requires careful consideration at each step, from sample preparation through bioinformatic analysis. The dUTP second-strand marking method provides high-quality strand-specific libraries that enable unambiguous identification of viral transcript orientation, which is crucial for understanding viral gene expression and regulation. By following the detailed protocols and considerations outlined in this application note, researchers can establish a sensitive and specific workflow for viral detection and characterization that supports both basic virology research and applied drug development efforts. As sequencing technologies continue to advance, the integration of strand-specific information will remain essential for unraveling the complex interactions between viruses and their hosts.

Library Construction Showdown: dUTP vs. RNA Ligation Methods for Viral Samples

Strand-specific RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) is a powerful tool that preserves the original orientation of transcripts, enabling precise mapping of viral RNA molecules to their genomic strand of origin. This capability is critical for detecting RNA editing events, characterizing antisense transcription, and accurately quantifying gene expression in overlapping genomic regions—common features in viral genomes. Among the various strategies for constructing strand-specific libraries, the dUTP second-strand marking and RNA ligation methods have emerged as leading protocols. This application note provides a detailed, evidence-based comparison of these two methods, focusing on their application in viral RNA editing detection research. We summarize quantitative performance data, provide detailed experimental protocols, and outline key reagent solutions to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the optimal library construction method for their virology studies.

Performance Comparison: dUTP vs. RNA Ligation Methods

Comprehensive comparative analyses have evaluated multiple strand-specific RNA-seq protocols across critical performance metrics. The table below synthesizes key findings from these studies to facilitate direct comparison between dUTP and RNA ligation methods.

Table 1: Performance comparison between dUTP and RNA ligation methods for strand-specific RNA-seq

| Performance Metric | dUTP Method | RNA Ligation Method | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strand Specificity | >90% [16] | >97% [25] | Universal Human Reference RNA (UHRR); human embryonic stem cells |

| Library Complexity (Unique Paired Reads) | 84% [4] | Not reported for paired-end | S. cerevisiae polyA+ RNA |

| Compatibility with Paired-End Sequencing | Yes (benefits significantly) [4] [14] | Limited (primarily single-end) [4] | Protocol design evaluation |

| Coverage Uniformity | Even coverage across gene body [16] | 5' bias observed [25] | Human transcriptome coverage |

| Sensitivity to Long Transcripts | Accurate quantification [26] | Underestimates long transcripts [26] | Comparison of TruSeq, SMARTer, and TeloPrime |

| Detection of Antisense/Overlapping Genes | Accurate [14] | Accurate [4] | Evaluation with overlapping genomic loci |

Experimental Protocols for Viral RNA Studies

dUTP Second-Strand Marking Protocol

The dUTP method incorporates uracil during second-strand synthesis, enabling selective degradation of this strand before amplification to preserve strand information.

Table 2: Key research reagents for the dUTP method

| Reagent | Function | Example Product |

|---|---|---|

| Oligo(dT) or Gene-Specific Primers | Reverse transcription priming | Thermo Scientific SuperScript Reverse Transcriptase |

| dUTP Nucleotides | Second-strand labeling | Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA Kit |

| Uracil-DNA Glycosylase (UDG) | Degradation of second strand | New England Biolabs UDG |

| DNA Polymerase (dUTP-Compatible) | cDNA amplification | Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase |

Detailed Workflow:

RNA Fragmentation and Priming: Fragment viral RNA and prime with oligo(dT) or sequence-specific primers targeting viral genomic or antigenomic strands.

First-Strand cDNA Synthesis: Synthesize first-strand cDNA using reverse transcriptase with dNTPs (including dTTP, not dUTP at this stage).

Second-Strand Synthesis: Incorporate dUTP instead of dTTP during second-strand synthesis, creating a uracil-labeled complementary strand.

End Repair and A-Tailing: Repair ends of double-stranded cDNA and add adenine nucleotide overhangs for adapter ligation.

Adapter Ligation: Ligate platform-specific sequencing adapters to cDNA fragments.

UDG Treatment: Treat with Uracil-DNA Glycosylase (UDG) to selectively degrade the dUTP-labeled second strand, preserving only the original first strand.

Library Amplification: Amplify the strand-specific library using PCR with indexed primers for multiplexing.

RNA Ligation Protocol

The RNA ligation method preserves strand information by directly ligating adapters to RNA fragments before cDNA synthesis, maintaining the original transcript orientation throughout library construction.

Table 3: Key research reagents for the RNA ligation method

| Reagent | Function | Example Product |

|---|---|---|

| Fragmentation Buffer | Controlled RNA fragmentation | Illumina Fragmentation Reagent |

| T4 RNA Ligase | Adapter ligation to RNA | New England Biolabs T4 RNA Ligase |

| 3' Di-deoxycytosine Adapters | Prevents self-ligation | IDT Swift RNA Kit |

| RNase Inhibitor | Prevents RNA degradation | Thermo Scientific RNaseOUT |

Detailed Workflow:

RNA Fragmentation: Fragment viral RNA using heat or enzymatic methods to optimal size for sequencing.

Adapter Ligation (RNA Level): Directly ligate specific adapters to the 3' end of fragmented RNA using T4 RNA ligase. Some protocols also ligate 5' adapters at this stage.

Reverse Transcription: Synthesize first-strand cDNA using reverse transcriptase with primers complementary to the 3' adapter.

cDNA Purification: Remove excess adapters and reagents to prevent interference with downstream steps.

Second-Strand Synthesis: Synthesize second-strand cDNA using DNA polymerase.

Library Amplification: Amplify the full library using PCR with indexed primers to add complete adapter sequences and indexes for multiplexing.

Method Selection Guide for Viral RNA Editing Research

Choosing between dUTP and RNA ligation methods requires careful consideration of research goals, viral genome characteristics, and practical laboratory constraints.

Table 4: Method selection guide based on research applications

| Research Application | Recommended Method | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Detection of C>U or A>I RNA Editing Sites | dUTP [6] | Paired-end sequencing enhances accuracy for identifying differential RNA variants |

| Antisense Transcription Profiling | dUTP [14] [3] | Superior strand specificity resolves overlapping transcripts from opposite strands |

| Viral Genome Annotation | RNA Ligation [4] [3] | High strand specificity supports accurate transcript boundary mapping |

| Expression Quantification of Overlapping Genes | dUTP [14] | Resolves ambiguity in gene assignment for dense viral genomes |

| Studies with Limited RNA Input | RNA Ligation (LM-Seq) [25] | Effective with as little as 10 ng total RNA |

| High-Throughput Screening | dUTP (Swift/IDT kits) [16] | Compatible with automation and multiplexing |

Both dUTP and RNA ligation methods provide high-quality strand-specific RNA-seq data suitable for viral RNA editing detection research, yet they offer distinct advantages. The dUTP method excels in applications requiring paired-end sequencing, provides higher library complexity, and enables more accurate quantification of overlapping transcripts—critical for characterizing complex viral transcriptomes [4] [14]. The RNA ligation method demonstrates exceptional strand specificity and can be more suitable for low-input samples [25].

For viral RNA editing studies specifically, the dUTP method's compatibility with paired-end sequencing provides significant advantages for detecting and validating RNA editing sites, as paired-end reads offer more comprehensive coverage of viral transcripts. Furthermore, the dUTP protocol's robustness across varying input amounts makes it suitable for diverse sample types, including clinical viral isolates with limited material [16].

When investigating cytidine deaminase activity (e.g., APOBEC-mediated C>U editing) in viral genomes, strand-specific information is essential to distinguish true RNA editing events from DNA-level mutations or sequencing artifacts [6] [27]. Both methods facilitate this discrimination, though the dUTP approach provides greater flexibility in sequencing strategies.

Researchers should select their library construction method based on priority applications: the dUTP method for maximum data quality and analytical flexibility, and RNA ligation for specific applications requiring direct RNA manipulation or when working with extremely limited viral RNA samples. As viral RNA editing research advances, both methods will continue to play crucial roles in unraveling the complex interactions between viral pathogens and host editing mechanisms.

RNA editing, particularly Adenosine-to-Inosine (A-to-I) conversion, represents a critical post-transcriptional process that increases transcriptome diversity. In virology, distinguishing these true RNA editing events from underlying genetic variants in the host or virus is essential for understanding host-virus interactions and viral evolution [28] [11]. This application note details a robust bioinformatics workflow that integrates DNA-Seq and RNA-Seq data to accurately identify bona fide RNA editing sites, with specific considerations for strand-specific RNA-seq protocols used in viral RNA editing detection research.

The core challenge stems from the fact that both single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in the genome and RNA editing events appear as mismatches when RNA-seq reads are aligned to a reference genome [29]. Without DNA-seq data from the same sample, one cannot confidently segregate these two types of sequence variations. This is particularly pertinent in viral research, where accurate identification of RNA edits can illuminate mechanisms of viral persistence, latency, and immune evasion.

Background and Key Concepts

RNA Editing and its Detection via Sequencing

A-to-I RNA editing, catalyzed by ADAR (Adenosine Deaminases Acting on RNA) enzymes, is the most prevalent RNA editing type in animals [28]. As inosine (I) is base-called as guanosine (G) during reverse transcription and sequencing, A-to-I editing is detected as A-to-G mismatches in aligned RNA-seq data [28] [30]. A less frequent but equally important type is Cytidine-to-Uridine (C-to-U) editing, mediated by APOBEC enzymes, which appears as C-to-T changes [31].

The Critical Role of Strand-Specific RNA-Seq

In the context of viral transcriptomics, strand-specific RNA-seq protocols are invaluable. They preserve the information about which genomic strand the RNA originated from, allowing researchers to unambiguously determine the direction of transcription [2]. This is crucial for:

- Accurately assigning edits to viral genes, especially in complex viral transcription units.

- Resolving overlapping transcripts from antisense or complementary viral strands.

- Eliminating a significant source of false positives caused by misassignment of reads from the opposite strand [32] [2]. Non-stranded protocols can misattribute antisense transcription to sense strands, inflating apparent mismatch counts and confounding downstream analysis.

Computational Strategies and Tool Selection

Two primary computational strategies exist for identifying RNA editing events, with the integrated DNA+RNA approach being the gold standard for minimizing false positives.

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Strategies for RNA Editing Detection

| Strategy | Description | Advantages | Limitations | Key Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrated DNA+RNA Analysis | Directly compares matched DNA-Seq and RNA-Seq from the same sample to filter genomic variants. | Highest accuracy; effectively removes false positives from private SNPs and somatic mutations. | Requires additional DNA sequencing; computationally intensive. | CADRES [31], JACUSA2 [33], GATK Best Practices [31] |

| RNA-Seq Only Analysis | Relies on RNA-Seq data alone, using filters (e.g., known SNPs, splice regions) and features (e.g., editing type) to predict sites. | Cost-effective; usable when DNA-Seq is unavailable. | Higher false positive rate; cannot filter novel or sample-specific genetic variants. | REDItools [34], SPRINT [33], L-GIREMI (for long-read data) [30] |

The "integrated" strategy, as implemented in the CADRES pipeline, operates in two phases: the RNA–DNA Difference (RDD) phase to remove genomic variants, and the RNA-RNA Difference (RRD) phase to identify sites with statistically significant differences in editing levels across conditions [31]. This is crucial for identifying condition-specific editing events, such as those induced during viral infection.

Benchmarking of Detection Tools

A benchmark study evaluating several RNA editing detection tools using ADAR1-knockout HEK293T cell data provides critical performance insights [33]. The study measured runtime, CPU usage, and maximum memory (RAM), offering practical guidance for tool selection based on available computational resources. Tools like JACUSA2 and SPRINT demonstrated robust performance, balancing accuracy and computational efficiency [33].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

This protocol outlines the steps for identifying RNA editing sites using matched DNA-Seq and strand-specific RNA-Seq data.

Sample Preparation and Sequencing

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Co-extract high-quality genomic DNA and total RNA from the same biological sample (e.g., virus-infected cells). Ensure RNA integrity (RIN > 8) for reliable transcriptome analysis.

- Library Preparation:

- For DNA-Seq, prepare a standard whole-genome or whole-exome sequencing library.

- For RNA-Seq, prepare a strand-specific library (e.g., using dUTP-based methods) [2]. This preserves strand information, which is critical for accurate editing detection and resolving overlapping viral transcripts.

Data Preprocessing and Alignment

- Quality Control: Use FastQC to assess raw read quality from both DNA and RNA sequencing.

- Trimming and Adapter Removal: Employ tools like Trimmomatic or Cutadapt to remove low-quality bases and adapter sequences.

- Read Alignment:

- DNA-Seq Reads: Align to the host and viral reference genome using a splice-unaware aligner like BWA-MEM [35] [33].

- RNA-Seq Reads: Align to the reference using a splice-aware aligner (e.g., STAR or HISAT2) [33]. For tools requiring it, aligners like BWA can be used with a reference that includes exon-exon junction sequences [33].

- Post-Alignment Processing: Sort and index BAM files. Mark PCR duplicates using tools like Picard. For RNA-Seq, it is crucial to specify the correct strandedness during downstream analysis if your tool requires it.

Variant Calling and RNA Editing Identification with CADRES

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of the CADRES pipeline for precise differential RNA editing site detection.

Workflow Title: CADRES Pipeline for Differential RNA Editing Detection

The CADRES pipeline ensures precise identification of Differential Variants on RNA (DVRs) through a two-phase process [31]:

RNA–DNA Difference (RDD) Phase:

- Perform joint variant calling on the DNA and RNA BAM files using GATK4 MuTect2 to create an initial set of variants [31].

- This step is critical for generating a sample-specific "denoised" dataset by removing variants present in the genome.

Recalibration and Final Calling:

- Use the variants identified in the RDD phase, augmented with known RNA editing sites from databases like REDIportal [34], as known sites for Base Quality Score Recalibration (BQSR).

- Perform a final, comprehensive mutation calling on the recalibrated RNA-Seq BAM file, applying stringent filters to remove artefacts and isolate bona fide RNA editing sites [31].

RNA–RNA Difference (RRD) Phase:

- To identify condition-specific editing (e.g., infected vs. mock-treated), utilize the Generalised Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) within statistical frameworks like rMATS.

- This model analyzes the depth of reference and alternative alleles across replicates of different conditions [31].

- Sites that show statistically significant alterations in editing levels are classified as high-confidence DVRs.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Item/Software | Specific Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Strand-Specific RNA Library Prep Kit (e.g., dUTP-based) | Preserves transcriptional strand orientation during cDNA library construction [2]. |

| High-Fidelity Reverse Transcriptase | Minimizes introduction of errors during cDNA synthesis from viral and host RNA [29]. | |

| DNA & RNA Extraction Kits | Co-isolation of genomic DNA and total RNA from the same sample ensures variant comparability. | |

| Computational Tools & Databases | CADRES Pipeline | Integrates DNA-Seq and RNA-Seq for precise DVR detection; uses GATK and GLMM [31]. |

| REDIportal | Curated database of known RNA editing sites; used for annotation and filtering [34]. | |

| JACUSA2 | A comprehensive software for RNA editing detection that can compare DNA and RNA samples, handling replicate data [33]. | |

| dbSNP Database | Public repository of human genetic variants; filters common polymorphisms [32]. | |

| STAR Aligner | Splice-aware aligner for accurate mapping of RNA-seq reads across exon junctions [33]. | |

| 3'-Sialyllactose | 3'-Sialyllactose, CAS:35890-38-1, MF:C23H39NO19, MW:633.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Analysis of Results and Validation

Key Metrics and Filtering Criteria

After running an editing detection pipeline, the results must be rigorously filtered. The following table summarizes common filters and quality metrics used to achieve a high-confidence set of RNA editing sites.

Table 3: Key Filters and Metrics for High-Confidence RNA Editing Sites

| Filtering Step | Rationale and Implementation | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Remove Known SNPs | Exclude sites overlapping with dbSNP and sample-specific DNA variants [35] [32]. | Eliminates most common genetic variants. |