Mastering RNA-seq: A Practical Guide to Optimizing Sequencing Depth and Coverage for Robust Results

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for managing sequencing depth and coverage in RNA-seq experiments.

Mastering RNA-seq: A Practical Guide to Optimizing Sequencing Depth and Coverage for Robust Results

Abstract

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for managing sequencing depth and coverage in RNA-seq experiments. It covers foundational principles, from distinguishing between depth and coverage to calculating requirements. It then delves into methodological best practices for experimental design and data analysis, followed by strategies for troubleshooting common issues like uneven coverage and batch effects. Finally, it addresses the validation of results, comparing analysis tools and discussing when orthogonal verification is necessary. The goal is to empower researchers to design cost-effective and powerful RNA-seq studies that yield accurate, reliable, and biologically meaningful data.

Sequencing Depth vs. Coverage: Demystifying the Core Concepts of RNA-seq

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between sequencing depth and coverage? Sequencing depth (or read depth) refers to the number of times a specific nucleotide is read during sequencing. It is often expressed as an average, e.g., 30x depth, and indicates the confidence in base calling [1] [2]. Coverage (or coverage breadth) refers to the percentage of the target genome or transcriptome that has been sequenced at least once [1] [2]. Depth is about how many times you sequence a base, while coverage is about how much of the total area you sequence.

How do I calculate the average depth of sequencing for a genome? The average depth of coverage can be theoretically calculated using the formula: (L × N) / G, where L is the read length, N is the number of reads, and G is the haploid genome length [3].

My experiment has low sequencing depth. How will this affect my results? Low sequencing depth reduces the statistical power of your experiment. It can lead to an inability to detect rare variants, accurately quantify lowly expressed genes, or identify differential expression with confidence [4] [3]. This increases the likelihood of both false positives and false negatives.

I have achieved high sequencing depth, but my coverage breadth is low. What could be the cause? High depth but low breadth indicates that the sequenced reads are not evenly distributed across the target region. Common causes include:

Should I prioritize higher sequencing depth or more biological replicates for my RNA-seq experiment? For differential gene expression analysis, increasing the number of biological replicates often provides a greater boost in statistical power than increasing sequencing depth beyond a certain point [4] [5]. A study found that increasing replicates from 2 to 6 at 10 million reads led to a higher increase in gene detection and power than increasing reads from 10 million to 30 million with only 2 replicates [4].

What is a good minimum sequencing depth for a standard bulk RNA-Seq differential gene expression experiment? For a standard differential gene expression analysis in humans, 5 million mapped reads is often considered a bare minimum to get a snapshot of highly expressed genes [4]. Many published experiments use 20-50 million reads per sample to achieve a more global view of gene expression and enable some analysis of features like alternative splicing [4] [6]. The exact requirement depends on the organism's complexity and project aims [6].

How does read length (e.g., single-end vs. paired-end) impact my experiment? Single-end reads are often sufficient for simple gene expression profiling and are less expensive [6]. Paired-end reads provide more information and are beneficial for applications like novel transcriptome assembly, identifying novel splice variants, and detecting insertions or deletions, as they sequence both ends of a fragment [7] [6] [5].

Sequencing Depth Recommendations for RNA-Seq Experiments

The optimal sequencing depth varies significantly with the goals of your study. The following table summarizes recommended depths for different RNA-seq applications.

| Experiment Goal | Recommended Read Depth (Mapped Reads per Sample) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Profiling (Snapshot) | 5 - 25 million [4] [6] | Sufficient for highly expressed genes; allows for high multiplexing [4]. |

| Standard Differential Expression | 20 - 50 million [4] | A common range for a global view of gene expression in published studies. |

| Alternative Splicing Analysis / Global Transcriptome View | 30 - 60 million [6] | Provides enough information to investigate different transcript isoforms. |

| Novel Transcript Discovery/Assembly | 100 - 200 million [6] | Very deep sequencing is needed for de novo assembly and to detect rare transcripts. |

| Targeted RNA Sequencing | ~3 million [6] | Fewer reads are required as the analysis is focused on a specific panel of genes. |

| miRNA or Small RNA Analysis | 1 - 5 million [6] | Requirements vary by tissue type; the short length of the targets means fewer reads are needed. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Illumina TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit | A widely used kit for constructing sequencing libraries from RNA samples [8]. |

| DNA 1000 Kit (Agilent Bioanalyzer) | Used to assess the quality and size distribution of the prepared sequencing libraries before sequencing [8]. |

| PhiX Control | A standard control (often added at 1%) used to improve base calling on Illumina sequencing runs, especially for low-complexity libraries [7]. |

| Unique Barcodes/Indexes | Short DNA sequences added to each sample's library during preparation, allowing multiple libraries to be pooled and sequenced together (multiplexed) and later bioinformatically separated [7]. |

| RNase-free DNase | Used to treat RNA samples to remove genomic DNA contamination, which is a critical step in ensuring pure RNA sequencing data [7]. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent results between technical replicates or unexpected library complexity.

- Potential Cause: Bias introduced during the PCR amplification step of library preparation [5].

- Solution: Optimize the number of PCR cycles to minimize over-amplification. Use PCR enzymes and protocols designed to reduce bias. Monitor library quality with an Agilent Bioanalyzer or similar instrument [8].

Problem: Low overall alignment rate of sequenced reads to the reference.

- Potential Causes:

- Sample Quality: Degraded RNA or DNA contamination can lead to poor-quality libraries [7].

- Contamination: Presence of ribosomal RNA or other non-target nucleic acids.

- Incorrect Reference: Using an incorrect or poor-quality reference genome/transcriptome.

- Solution: Always check RNA quality (e.g., RIN score) before library prep. Use rRNA depletion kits if needed. Ensure you are using the correct and well-annotated reference for your organism [7].

- Potential Causes:

Problem: Failure to detect known differentially expressed genes or genetic variants.

- Potential Cause: Insufficient statistical power due to low sequencing depth or too few biological replicates [4] [8] [3].

- Solution: Re-evaluate your experimental design. For differential expression, a study found that a minimum of 20 million reads was sufficient to elicit key toxicity pathways in a model with three biological replicates [8]. When possible, increase the number of biological replicates.

Experimental Protocol: Determining Minimum Sequencing Depth

This methodology outlines a wet-lab and computational approach to empirically determine the minimum sequencing depth required for your specific RNA-seq study, based on subsampling existing data [8].

1. Principle: Existing high-depth sequencing data from a pilot or previous experiment is computationally subsampled to lower depths. Key outcomes (e.g., number of detected genes, differential expression results) are re-calculated at each depth to find the point of saturation, beyond more depth yields diminishing returns.

2. Materials:

- High-depth RNA-seq data set (BAM file format) from a representative sample [8].

- Bioinformatics tools for subsampling (e.g., Picard DownsampleSam) and read counting [8].

- Differential expression analysis software (e.g., DESeq2, edgeR).

3. Procedure:

1. Subsampling: Use a tool like the Picard DownsampleSam module to create subsets of your original BAM file at a series of lower depths (e.g., 10M, 20M, 40M, 60M reads) [8].

2. Gene Quantification: For each subsampled BAM file, generate a raw read count for each gene using a tool like featureCounts or HTSeq.

3. Differential Expression Analysis: Perform a standard differential expression analysis between your experimental conditions at each sequencing depth level.

4. Saturation Analysis: Plot the number of detected genes or the number of significantly differentially expressed genes against the sequencing depth. The "elbow" of the curve, where the gains level off, indicates a sufficient minimum depth.

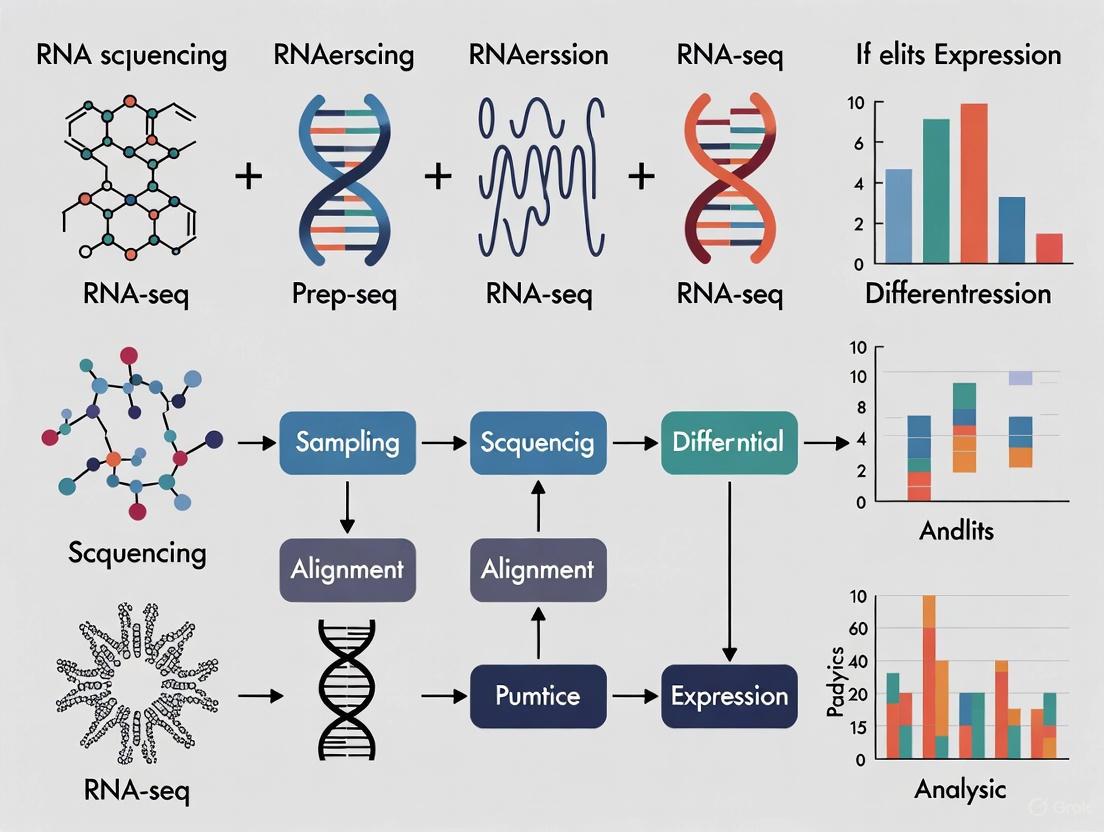

The logical workflow for this protocol and the relationship between key metrics and experimental goals can be visualized in the following diagrams:

Defining the Core Concepts

What are Sequencing Depth and Coverage?

In RNA-Seq experiments, sequencing depth (or read depth) and coverage are two fundamental yet distinct metrics that are crucial for data quality.

- Sequencing Depth refers to the average number of times a specific nucleotide in the genome is read during the sequencing process. It is expressed as an average multiple, such as 30x or 100x. A higher depth means more data points for each base, which increases confidence in base calling and helps mitigate sequencing errors and technical noise [1].

- Coverage describes the percentage of the target genome or transcriptome that has been sequenced at least once. It is typically expressed as a percentage (e.g., 95% coverage). High coverage ensures that the entire region of interest is represented in the data, leaving no gaps [1].

| Metric | Definition | What It Measures | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Depth | The average number of times a base is sequenced [1]. | The redundancy of sequencing for a given location. | Higher depth increases confidence in variant calls, especially for low-abundance variants or heterogeneous samples [1]. |

| Coverage | The proportion of the target region sequenced at least once [1]. | The completeness of the sequenced data. | High coverage ensures no regions are missed, preventing gaps in the data that could lead to missed discoveries [1]. |

The relationship between them is synergistic: increasing sequencing depth generally also improves coverage, as more reads have a higher likelihood of covering more regions. However, due to biases in library preparation or sequencing, certain regions may still be underrepresented or missed entirely [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Scenarios and Solutions

FAQ 1: "I am not detecting known low-frequency variants in my cancer RNA-Seq data. What should I optimize?"

- Likely Cause: Insufficient sequencing depth. The transcripts containing the variants may be expressed at low levels, and a shallow sequence depth fails to generate enough reads to distinguish a true variant from background noise [9].

- Solution: Increase your total sequencing depth. For somatic variant calling in cancer RNA-Seq, studies have shown that between 30 million and 40 million 100 bp paired-end reads are often needed to recover 90-95% of single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in recurrently mutated genes [9]. Sensitivity drops significantly (to around 80%) with only 20 million fragments [9].

FAQ 2: "My transcriptome assembly has many gaps, missing known exons and genes. What is the issue?"

- Likely Cause: Inadequate transcriptome coverage. The sequencing depth may be too low to capture the full diversity of transcripts, particularly those that are lowly expressed or transient [10] [11].

- Solution: Increase the total number of sequenced reads to improve coverage. Research indicates that for a complex transcriptome, a depth of about 10 million 75 bp reads can detect approximately 80% of annotated genes, while over 30 million reads may be required to detect nearly all annotated genes [10]. Note that increasing depth beyond a certain point (e.g., 2-8 Gbp) yields diminishing returns for recovering annotated exonic regions and instead recovers a large number of unannotated, single-exon transcripts [11].

FAQ 3: "I am getting high genotyping error rates for SNPs in my population study. How can I improve accuracy?"

- Likely Cause: Insufficient read depth at the variant site. Low coverage means the genotype call is based on very few observations, which is highly susceptible to random sequencing errors [12].

- Solution: Ensure a high minimum depth at each locus. For SNP genotyping using restriction-enzyme-based methods, error rates are highly sensitive to coverage. One study found that while a coverage of ≥5x yielded a median genotyping error rate of 0.03, increasing the minimum coverage to ≥30x reduced the median error rate to ≤0.01 in reference-aligned datasets [12].

FAQ 4: "For single-cell RNA-Seq, should I sequence more cells shallowly or fewer cells deeply?"

- Likely Cause: A suboptimal balance between the number of cells (n_cells) and the sequencing depth per cell (n_reads) for a fixed budget [13].

- Solution: For estimating population-level gene properties (like gene expression distributions), the optimal strategy is often to maximize the number of cells while ensuring an average sequencing depth of around one read per cell per gene. This approach provides a better overview of biological heterogeneity. Sequencing much deeper (e.g., 10x more reads per cell) without increasing cell number can be less efficient, potentially leading to a twofold higher estimation error for the same total budget [13].

The following diagram illustrates the core trade-off and relationship between these key parameters in an RNA-Seq experiment.

Experimental Protocols: Determining Optimal Depth

Methodology 1: A Downsampling Approach to Determine Sufficient Depth for Variant Calling

This protocol, adapted from a study on acute myeloid leukemia, uses computational downsampling to determine the minimal depth needed for sensitive variant detection [9].

- Deep Sequencing: Begin by sequencing a subset of pilot RNA samples (e.g., 3-5 samples) to a very high depth (e.g., >100 million paired-end reads).

- Variant Calling: Call variants on this deep dataset using your chosen pipeline (e.g., a combination of VarDict, MuTect, or VarScan) to establish a "truth set" of high-confidence variants [9].

- Computational Downsampling: Use a script (e.g., in Perl or Python) to randomly sample subsets of reads from the original deep dataset to simulate lower sequencing depths (e.g., 80M, 50M, 40M, 30M, and 20M fragments) [10] [9].

- Variant Recall: Re-call variants at each downsampled depth.

- Sensitivity Calculation: Calculate the sensitivity (percentage of variants from the "truth set" recovered) at each depth.

- Determine Optimal Depth: Identify the depth where sensitivity plateaus at an acceptable level (e.g., >90%). The study found that sensitivity dropped markedly below 30M fragments [9].

Methodology 2: Random Sampling to Determine Depth for Transcriptome Coverage

This method, used in a chicken transcriptome study, assesses how sequencing depth affects gene detection [10].

- Generate High-Depth Data: Sequence a cDNA library to a high depth (e.g., 30 million 75 bp reads).

- Random Sampling: Use a custom program to randomly draw without replacement a fixed number of reads (e.g., 10M, 15M, 20M) from the full dataset. Repeat this process multiple times (e.g., 4 replicates) to ensure statistical robustness [10].

- Gene Detection Analysis: Map each sub-sampled dataset to the reference genome and count the number of annotated genes detected.

- Plot and Analyze: Plot the number of detected genes against sequencing depth. The point where the curve begins to plateau indicates a sufficient depth for transcriptome coverage. The study showed that 10M reads detected ~80% of genes, with minimal gains beyond 20M-30M reads for many applications [10].

The table below summarizes key recommendations from various studies.

| Application | Recommended Sequencing Depth | Key Findings and Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Variant Calling (Cancer RNA-Seq) | 30M - 40M fragments (100bp PE) [9] | Recovers 90-95% of initial SNVs. Sensitivity drops significantly below 30M fragments [9]. |

| Whole Transcriptome Profiling | 10M - 30M reads (75bp) [10] | 10M reads detects ~80% of annotated genes; 30M reads detects >90% of genes. Serves as a replacement for microarrays [10]. |

| De Novo Transcriptome Assembly | 2 - 8 Gbp total [11] | The amount of exomic sequence assembled typically plateaus in this range. Deeper sequencing mainly recovers unannotated single-exon transcripts [11]. |

| Single-Cell RNA-Seq (Gene Property Estimation) | ~1 UMI/read per cell per gene [13] | For a fixed budget, maximizing cells with shallow depth per cell is optimal for estimating gene expression distributions [13]. |

| SNP Genotyping (ddRAD) | ≥30x coverage [12] | Median genotyping error rates decline to ≤0.01 at coverage ≥30x, compared to ≥0.03 at ≥5x coverage [12]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function in RNA-Seq Workflow |

|---|---|

| Oligo(dT) Beads | To enrich for polyadenylated mRNA from total RNA by hybridization, reducing ribosomal RNA background [10]. |

| RNA Sequencing Sample Preparation Kit (e.g., Illumina) | Provides the necessary reagents for cDNA library construction, including fragmentation, end-repair, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification [10]. |

| DNase I | Digests and removes genomic DNA contamination from RNA samples post-isolation, ensuring a pure RNA template [10]. |

| SPIA Amplification Kit (e.g., NuGEN) | Uses single primer isothermal amplification for linear amplification of cDNA, which can be critical for low-input samples [5]. |

| Universal Human Reference RNA (UHRR) | A standardized reference RNA sample used as a control to compare the performance of different sequencing technologies or library prep protocols [11]. |

| CD34+ Cells | Can be used to create a "Panel of Normals" (PON) for variant filtering in cancer studies, helping to identify and remove common technical artifacts and germline variants [9]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Inadequate Sequencing Depth

Problem: My RNA-seq experiment failed to detect differentially expressed genes, especially those expressed at low levels.

Diagnosis and Solution:

- Symptoms: Inability to detect known low-abundance transcripts; high variability in gene expression measurements between replicates.

- Root Cause: Insufficient sequencing depth, leading to undersampling of the transcriptome.

- Recommended Actions:

- Recalculate Required Depth: For mammalian transcriptomes, aim for 20-40 million reads per sample for mRNA libraries, or 40-80 million reads for total transcriptome libraries that include non-coding RNAs [14].

- Increase Biological Replicates: When budget-constrained, prioritize more biological replicates over deeper sequencing, as this provides greater statistical power for detecting differential expression [14].

- Optimize Library Complexity: Ensure high RNA quality (RIN >7) and use appropriate depletion methods to maximize informative reads rather than ribosomal RNA [15].

Guide 2: Managing Excessive Sequencing Costs

Problem: My sequencing costs are exceeding budget without proportional scientific benefit.

Diagnosis and Solution:

- Symptoms: Diminishing returns where additional sequencing depth yields minimal new biological insights; budget depletion limiting sample size.

- Root Cause: Oversequencing individual samples beyond what is necessary for the research question.

- Recommended Actions:

- Right-Size Your Depth: For many applications, including eQTL studies, sequencing more samples at lower coverage (e.g., ~6 million reads/sample) provides better statistical power than fewer samples at high coverage [16].

- Choose Appropriate Sequencing Mode: Use single-end sequencing instead of paired-end when your primary goal is differential expression analysis rather than alternative splicing detection [14].

- Implement rRNA Depletion: Reduce wasteful sequencing of ribosomal RNA (comprising ~80% of cellular RNA) through ribosomal depletion methods to enhance cost-effectiveness [15].

Frequently Asked Questions

Experimental Design FAQs

How do I determine the optimal sequencing depth for my RNA-seq experiment? The ideal depth depends on your transcriptome size and research goals. Use the following table as a guideline:

Table 1: Recommended RNA-seq Sequencing Depth Guidelines

| Application | Recommended Depth | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Mammalian mRNA-seq | 20-40 million reads/sample | Sufficient for most differential expression studies [14] |

| Total transcriptome (including non-coding RNAs) | 40-80 million reads/sample | Required for adequate coverage of diverse RNA species [14] |

| eQTL discovery studies | ~6 million reads/sample | More samples at lower depth increases power [16] |

| Bacterial transcriptomes | 5-10 million reads/sample | Smaller genomes require less depth [17] |

| De novo transcriptome assembly | 100 million reads/sample | Comprehensive coverage needed for reconstruction [17] |

Should I use single-end or paired-end sequencing for my experiment? Choose based on your research priorities and budget:

- Single-end: Recommended for most gene expression studies; much cheaper with minimal information loss for differential expression analysis once reads exceed 50 bp [14].

- Paired-end: Essential for alternative splicing analysis, novel transcript detection, or when working with poor-quality reference genomes [14].

How many biological replicates do I need? The optimal number depends on your experimental system:

- In vitro studies with homogeneous cell lines: Fewer replicates may suffice (e.g., 3-4).

- Primary cells from human subjects: More replicates are essential due to greater biological variability.

- General rule: Prioritize more replicates over deeper sequencing, as this significantly boosts statistical power for detecting differentially expressed genes [14].

Technical Optimization FAQs

When should I use rRNA depletion versus poly-A selection? The choice depends on your RNA quality and research focus:

Table 2: RNA Selection Method Comparison

| Method | Best For | RNA Quality Requirements | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly-A selection | mRNA enrichment in eukaryotes | High-quality RNA (RIN ≥8) with intact polyA tails [18] | Unsuitable for degraded samples or non-polyadenylated RNAs |

| rRNA depletion | Degraded samples (FFPE), non-coding RNA, bacterial RNA | Compatible with low-quality RNA (RIN 2-3) [17] [18] | Additional cost and processing step; potential off-target effects [15] |

| Globin depletion (blood samples) | Improving detection of low-expression transcripts in blood | Standard blood RNA quality | Removes globin transcripts, which may be biologically relevant in some studies [15] [17] |

What are the key considerations for working with challenging sample types?

- FFPE samples: Use rRNA depletion or targeted RNA exome approaches due to expected RNA degradation [17]. The SMARTer Universal Low Input RNA Kit is specifically validated for degraded RNA (RIN 2-3) [18].

- Blood samples: Implement both rRNA and globin depletion to significantly improve detection of low-expression transcripts [17].

- Ultra-low input samples: Utilize specialized kits like SMARTer Ultra Low or SMART-Seq v4 designed for 10 pg-10 ng total RNA or 1-1,000 cells [18].

When should I consider using UMIs (Unique Molecular Identifiers)? Incorporate UMIs in these scenarios:

- Deep sequencing (>50 million reads/sample) to correct PCR amplification biases [17].

- Low-input library preparation where amplification bias is a significant concern [17].

- Absolute transcript quantification requirements, as UMIs enable accurate molecular counting [17].

Experimental Workflow: Balancing Comprehensiveness and Cost

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points in designing a cost-efficient RNA-seq experiment:

Diagram 1: RNA-seq experimental design workflow for cost efficiency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq Experiments

| Reagent/Kit | Primary Function | Optimal Use Cases | Input Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMART-Seq v4 Ultra Low Input Kit | Full-length cDNA synthesis from ultra-low input | 1-1,000 cells or 10 pg-10 ng total RNA; requires high-quality RNA (RIN ≥8) [18] | Oligo(dT) priming |

| SMARTer Stranded RNA-Seq Kit | Strand-specific library prep | 100 pg-100 ng of full-length or degraded RNA; maintains strand information >99% [18] | Requires rRNA depletion or poly-A enrichment |

| SMARTer Universal Low Input RNA Kit | Library prep from degraded samples | 200 pg-10 ng degraded RNA (RIN 2-3); compatible with FFPE samples [18] | Random priming; requires rRNA depletion |

| RiboGone - Mammalian Kit | Ribosomal RNA depletion | 10-100 ng samples of mammalian total RNA; improves cost-efficiency [18] | Works with various RNA qualities |

| ERCC Spike-in Mix | RNA quantification standardization | 92 synthetic transcripts for sensitivity assessment; not recommended for low-concentration samples [17] | Added before library prep |

FAQs on Estimating Sequencing Depth and Coverage

1. What is the difference between sequencing depth and coverage? While often used interchangeably, sequencing depth and coverage are distinct metrics. Sequencing depth (or read depth) refers to the average number of times a specific nucleotide base is read during sequencing. It is expressed as a multiple (e.g., 30x) and is crucial for the accuracy of base calling and variant detection [19] [1]. Coverage refers to the proportion of the target genome or transcriptome that has been sequenced at least once. It is typically expressed as a percentage (e.g., 95% coverage) and indicates the comprehensiveness of the sequencing data [19] [1].

2. What is the recommended sequencing depth for a standard RNA-Seq experiment? For standard RNA-Seq differential gene expression analysis, a sequencing depth of 10 to 50 million reads per sample is often sufficient [19] [20]. This typically translates to a coverage of approximately 10x to 30x [19]. The exact requirement depends on the goals of your study; detecting rare or lowly-expressed transcripts generally requires greater depth [20] [21].

3. How do I calculate the required sequencing depth for my experiment? You can estimate the required sequencing depth using a variation of the Lander/Waterman equation for coverage [21]: C = (L * N) / G Where:

- C = Coverage

- L = Read length

- N = Number of reads

- G = Haploid genome or transcriptome length

To solve for the number of reads (N) needed to achieve a desired coverage (C), you can rearrange the formula: N = (C * G) / L [21].

4. My data has uneven coverage. What are the common causes and solutions? Uneven coverage is a common issue in RNA-Seq and can be caused by:

- Technical biases from library preparation, such as PCR amplification bias [19].

- Biological factors, including regions with high GC content or repetitive sequences that are difficult to sequence [19] [1].

- Transcript length bias, where longer transcripts naturally accumulate more reads in whole transcriptome protocols [22]. Solutions include optimizing library preparation protocols, using unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to account for PCR duplicates, and ensuring you use appropriate normalization methods (like TMM or median-of-ratios) in your downstream analysis to correct for these biases [19] [20].

5. How does the choice between Whole Transcriptome Sequencing and 3' mRNA-Seq affect my depth and coverage needs? The choice of RNA-Seq methodology significantly impacts your experimental design:

| Methodology | Recommended Depth | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Transcriptome (WTS) | Higher depth required; often 20-50 million reads or more [20]. | Reads are distributed across the entire transcript. Essential for detecting splice variants, fusion genes, and novel isoforms [22]. |

| 3' mRNA-Seq | Lower depth sufficient; often 1-5 million reads [22]. | Reads are localized to the 3' end of transcripts. Ideal for high-throughput, cost-effective gene expression quantification, especially for large sample numbers [22]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues with Depth and Coverage

Problem: Inability to detect differentially expressed genes, especially low-abundance transcripts.

- Potential Cause: Insufficient sequencing depth.

- Solution: Increase the sequencing depth per sample. For projects focused on rare transcripts or low-fold-change differences, consider sequencing up to 50-100 million reads or more. Use power analysis tools on pilot data to determine the optimal depth [20].

Problem: Large portions of the transcriptome are missing from the data.

- Potential Cause: Inadequate coverage, often due to poor RNA quality, inefficient library preparation, or an insufficient number of total sequenced reads.

- Solution: Check RNA integrity (e.g., RIN score) before library prep. Optimize or troubleshoot the cDNA synthesis and library construction steps. Ensure you are generating a sufficient volume of raw sequencing data to cover your target transcriptome [19] [1].

Problem: High variability in read counts between biological replicates.

- Potential Cause: An insufficient number of biological replicates, which reduces the statistical power to detect true differences.

- Solution: Increase the number of biological replicates. While three is often a minimum, more replicates are required when biological variability is high. More replicates generally provide greater statistical power than simply increasing sequencing depth alone [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Poly(A) Selection Beads | Isolates messenger RNA (mRNA) from total RNA by binding to the poly(A) tail, enriching for coding transcripts and reducing ribosomal RNA (rRNA) contamination. |

| Ribosomal Depletion Probes | Selectively removes abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequences from total RNA, allowing for the sequencing of both coding and non-coding RNA species. |

| Reverse Transcriptase Enzyme | Synthesizes complementary DNA (cDNA) from the RNA template, creating a stable copy for downstream library construction and amplification. |

| Oligo(dT) Primers | Primers that bind to the poly(A) tail of mRNA to initiate cDNA synthesis; a key component of 3' mRNA-Seq protocols [22]. |

| Random Hexamer Primers | Primers that bind randomly to RNA fragments, used in whole transcriptome protocols to generate coverage across the entire length of the transcript [22]. |

| Fragmentation Enzymes/Buffers | Physically or enzymatically shears cDNA or RNA into appropriately sized fragments for optimal sequencing on NGS platforms. |

Workflow for Determining Sequencing Needs

The following diagram outlines the key decision points for planning your RNA-seq experiment to ensure adequate depth and coverage.

This guide is based on the latest best practices in the field [19] [20] [22]. For further details on specific protocols and statistical methods, please refer to the cited literature.

From Theory to Bench: Designing and Executing Your RNA-seq Experiment

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between sequencing depth and coverage? These terms are often used interchangeably but have distinct meanings [1].

- Sequencing Depth (or Read Depth): Refers to the number of times a specific nucleotide is read during sequencing. It is expressed as an average (e.g., 100x depth) and is crucial for confident variant calling [1].

- Coverage: Describes the percentage of the entire genome or target region that has been sequenced at least once. It ensures the completeness of the data (e.g., 95% coverage) [1].

How does experimental goal influence sequencing depth? Your study's objective is the primary driver for determining the appropriate sequencing depth [1].

- Gene Expression Profiling of highly expressed genes requires less depth.

- Detection of Rare Transcripts or Splicing Variants requires greater depth for sufficient sensitivity.

- Single-Cell RNA-Seq involves a trade-off between sequencing many cells shallowly or fewer cells more deeply [13].

My differential gene expression analysis lacks power. Could sequencing depth be the issue? Yes, insufficient sequencing depth is a common cause. For standard bulk RNA-Seq DGE analysis, a minimum of 20–30 million reads per sample is often sufficient [20]. However, the required depth increases if your study focuses on lowly expressed genes. Using too few replicates also reduces power; three replicates per condition is a typical minimum, but more are needed when biological variability is high [20].

Sequencing Depth Recommendations by Application

Table 1: Recommended sequencing depth and key considerations for various RNA-Seq applications.

| Application | Recommended Depth (per sample) | Key Considerations & Goals |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Profiling | 5 - 25 million reads [6] | Quick snapshot of highly expressed genes; allows for high multiplexing. |

| Standard DGE Analysis | 30 - 60 million reads [6] | Global view of expression; some information on alternative splicing. |

| In-depth Transcriptome | 100 - 200 million reads [6] | Novel transcript assembly, comprehensive splicing analysis. |

| Targeted RNA Panels | ~3 million reads [6] | Targeted approaches (e.g., TruSight RNA Pan Cancer) require fewer reads. |

| miRNA / Small RNA Seq | 1 - 5 million reads [6] | Varies significantly by tissue type. |

| Single-Cell RNA-Seq | Varies by cell number | Balance between number of cells and depth. A mathematical framework suggests an optimal allocation may be shallow sequencing (e.g., ~1 read per cell per gene) of many cells [13]. |

Single-Cell RNA-Seq Experimental Design

For single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq), the experimental design question revolves around how to allocate a fixed sequencing budget: should you sequence a few cells deeply or many cells shallowly? [13]

A mathematical framework suggests that for estimating many important gene properties, the optimal allocation is to sequence at a depth of around one read per cell per gene. Interestingly, this often means maximizing the number of cells sequenced while ensuring that at least ~1 UMI per cell is observed on average for biologically critical genes [13]. One analysis demonstrated that sequencing 10 times more cells at 10 times shallower depth could reduce the estimation error by twofold [13].

The following workflow outlines the key steps and considerations for designing your sequencing experiment:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential reagents, tools, and software for RNA-Seq experiments and data analysis.

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Kit | Isolates mRNA from total RNA for library preparation [23]. |

| NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina | Prepares sequencing libraries from cDNA [23]. |

| Cell Ranger | Standardized pipeline for processing raw data from 10x Genomics scRNA-seq platforms [24]. |

| Trimmomatic / Cutadapt | Tools for read trimming to remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases [20]. |

| STAR / HISAT2 | Aligns (maps) sequencing reads to a reference genome [20]. |

| Kallisto / Salmon | Performs pseudo-alignment for fast transcript abundance estimation [20]. |

| featureCounts / HTSeq | Counts the number of reads mapped to each gene [20]. |

| DESeq2 / edgeR | Software packages for differential gene expression analysis [20]. |

| Seurat | A comprehensive R package for the analysis of single-cell RNA-seq data [24]. |

| FastQC / MultiQC | Performs initial quality control on raw sequenced data and generates reports [20]. |

FAQs on Biological Replicates in RNA-Seq

Why are biological replicates more important than sequencing depth for most genes?

Multiple independent studies have concluded that for the majority of genes, increasing the number of biological replicates has a larger impact on the statistical power of differential expression analysis than increasing sequencing depth [25] [26] [27]. Biological replicates capture the natural random variation that occurs between different biological subjects (e.g., different mice, different batches of cells), allowing you to determine if an observed effect is consistent and generalizable [28]. While deeper sequencing helps detect lowly expressed genes, beyond a certain point (often ~20-30 million reads per sample), it yields diminishing returns. Power, however, continues to increase significantly with more replicates [20] [26].

What is the fundamental difference between a biological and a technical replicate?

Understanding this distinction is critical for proper experimental design.

- Biological Replicates are measurements taken from biologically distinct samples. They capture the biological variation in a population. Examples include:

- Technical Replicates are repeated measurements of the same biological sample. They assess the variability of your assay or measurement technique. Examples include:

Technical replicates tell you about the precision of your lab work, while biological replicates tell you whether your findings are reproducible across a population [30] [29] [28].

How many biological replicates are needed for a robust RNA-seq experiment?

There is no universal number, as it depends on the desired power, effect size, and biological variability of your system. However, evidence-based guidelines provide a strong starting point.

- Absolute Minimum: 3 biological replicates per condition. However, with only three, most statistical tools will detect only 20-40% of all differentially expressed (DE) genes identified with high replicate numbers (e.g., 42). Power is sufficient primarily for genes with very large fold changes (>4-fold) [32].

- Recommended Minimum: 6 biological replicates per condition. This offers a much better balance for identifying DE genes across a range of fold changes [32].

- For Robust Detection: 12 or more biological replicates. To detect >85% of all DE genes, including those with more subtle fold changes, more than 20 replicates may be necessary [32]. For specific contexts like toxicology dose-response studies, at least 4 replicates are recommended [27].

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from the literature:

| Recommendation / Finding | Minimum Replicates | Context / Key Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Guideline | 4 | Tomato research; ensures detection of ~1000 DE genes with 20M reads/sample. | [25] |

| Practical Minimum | 6 | Superior true/false positive performance with tools like DESeq2 and edgeR. | [32] |

| For All Fold Changes | 12 | Needed to detect >85% of SDE genes, regardless of effect size. | [32] |

| Power vs. Depth | >20 | Replicate number has a larger impact on power than sequencing depth. | [25] [26] |

| Toxicology Context | 4 | Reliable benchmark dose (BMD) pathways in dose-response studies. | [27] |

Which statistical tools are best for differential expression analysis with low replicate numbers?

For experiments with fewer than 12 replicates, DESeq2 and edgeR provide a superior combination of true positive detection and false positive control [32]. These tools use the negative binomial distribution to model RNA-Seq count data, which accurately accounts for the biological variation measured by your replicates [26] [32].

How can I formally estimate the number of replicates needed for my specific experiment?

You should use a power analysis tool before conducting your experiment. These tools use parameters from previous, similar datasets to estimate the sample size required to achieve your desired statistical power.

- RnaSeqSampleSize is a Bioconductor R package and web tool that uses real data distributions (e.g., from TCGA) to provide realistic sample size estimates, taking into account the varying expression levels and dispersions across thousands of genes [33].

- Performing a pilot experiment and analyzing the resulting data is another highly effective way to estimate parameters for a full-scale study [25].

Experimental Protocol: Power and Sample Size Estimation Using RnaSeqSampleSize

Objective: To determine the optimal number of biological replicates required for a robust RNA-seq experiment by performing a power analysis based on a reference dataset.

Materials:

- Computer with R installed.

- RnaSeqSampleSize package from Bioconductor.

- Reference RNA-seq dataset (e.g., from a public repository like TCGA or a pilot experiment).

Methodology:

- Install and Load Package: Install the

RnaSeqSampleSizepackage from Bioconductor and load it into your R session [33]. - Define Analysis Parameters: Set the key statistical parameters for your planned experiment:

- False Discovery Rate (FDR): Typically set to 0.05.

- Desired Statistical Power: Typically set to 0.8 or 0.9.

- Fold Change: The minimum effect size (e.g., 2-fold) you are interested in detecting.

- Gene Signature (Optional): If your interest is in a specific pathway, provide a list of relevant genes or a KEGG pathway ID [33].

- Input Reference Data: Provide a reference dataset that closely resembles your expected experimental system. This allows the tool to use realistic distributions of gene expression and dispersion for its calculations [33].

- Perform Power Calculation: Execute the package's functions to estimate either:

- The power achievable with a given sample size, or

- The sample size required to achieve a given power.

- Visualize and Interpret: Use the package's built-in plotting functions to visualize power curves, which show the relationship between sample size and statistical power for your parameters [33].

This workflow for determining the optimal number of replicates can be summarized in the following decision pathway:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Context in Replicate Design |

|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | A statistical software package for differential analysis of RNA-seq count data. | Recommended tool for DE analysis, especially with lower replicate numbers (n<12) [32]. |

| edgeR | A statistical software package for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. | Recommended tool for DE analysis, especially with lower replicate numbers (n<12) [32]. |

| RnaSeqSampleSize | An R/Bioconductor package for sample size and power estimation. | Uses real data distributions to calculate necessary biological replicates before a full-scale experiment [33]. |

| TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) | A public repository containing a vast array of RNA-seq datasets. | Serves as an ideal source of reference data for power analysis in human cancer studies [33]. |

| Biological Samples (e.g., Cell Cultures, Model Organisms) | The fundamental units of study from which RNA is extracted. | Must be processed as independent, biologically distinct entities to qualify as true biological replicates [29] [28]. |

Sequencing depth and coverage are foundational concepts in designing a robust RNA-seq experiment. Within the context of this thesis, managing these parameters is critical for generating biologically meaningful results. Sequencing depth (or read depth) refers to the number of times a specific nucleotide is read during sequencing, directly influencing confidence in base calling and variant detection [1]. Coverage describes the percentage of the target genome or transcriptome that has been sequenced at least once, ensuring comprehensive representation [1]. For RNA-seq, the required read depth varies significantly based on experimental goals, ranging from 5 million reads per sample for a quick snapshot of highly expressed genes to 100-200 million reads for novel transcript assembly and in-depth analysis [6]. Balancing sufficient depth and coverage against available resources is a central challenge in experimental design, impacting everything from initial read quality to the final list of differentially expressed genes.

The Standard RNA-seq Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete pathway for RNA-seq data analysis, from raw sequencing data to biological interpretation, highlighting key quality control checkpoints.

Workflow Stages and Key Considerations

- Raw FASTQ to Quality Control: Process begins with raw sequencing data, assessing initial quality metrics like per-base sequence quality and adapter content [34] [35].

- Trimming and Post-Trimming QC: Remove low-quality bases and adapter sequences, then verify improvements [35].

- Alignment and Quantification: Map reads to a reference genome or transcriptome, then count reads associated with genes [34] [35].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Normalize count data to account for confounding factors and identify statistically significant expression changes [36] [37].

- Visualization and Interpretation: Explore results and derive biological meaning.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key Software Tools and Resources for RNA-seq Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Tool(s) | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Control | FastQC [34] [38] [35], MultiQC [34], fastp [34] [39], Trimmomatic [35], Trim_Galore [39] | Assesses raw and trimmed read quality; trims adapters and low-quality bases. | FastQC provides visual reports; MultiQC aggregates multiple reports; fastp is fast and integrated; Trimmomatic is highly cited but complex. |

| Alignment | STAR [34] [35], TopHat2 [38] | Aligns RNA-seq reads to a reference genome. | STAR is splice-aware and widely used; requires genome indexing. |

| Quantification | FeatureCounts [35], HTSeq [38], Salmon [34] | Generates count data for each gene by counting reads overlapping genomic features. | Can be performed on aligned BAM files (FeatureCounts) or via pseudoalignment (Salmon). |

| Differential Expression | DESeq2 [34] [36] [38], edgeR [36] | Identifies statistically significant differentially expressed genes. | Both use negative binomial models; DESeq2 is known for stringent normalization. |

| Normalization Methods | DESeq2's Median of Ratios [37], edgeR's TMM [36] [37] | Scales raw counts to make samples comparable. | Essential for correcting for library size and RNA composition. TMM assumes most genes are not DE. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common RNA-seq Pipeline Issues

How Do I Determine the Appropriate Sequencing Depth for My RNA-seq Experiment?

The required sequencing depth depends heavily on your experimental objectives and organism complexity [6]. The ENCODE project provides excellent guidelines, but you should also consult primary literature specific to your field and organism [6].

Table 2: Recommended Sequencing Depth for Different RNA-seq Goals

| Experimental Goal | Recommended Reads Per Sample | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Quick Snapshot / Targeted Expression | 5 - 25 million [6] | Sufficient for profiling highly expressed genes. Allows for high multiplexing of samples. |

| Standard Gene Expression Profiling | 30 - 60 million [6] | Encompasses most published mRNA-seq experiments. Provides a global view of expression. |

| Alternative Splicing Analysis | 30 - 60 million [6] | Paired-end reads are recommended to capture splice junctions. |

| Novel Transcript Discovery/Assembly | 100 - 200 million [6] | Deeper sequencing helps assemble complete transcripts and identify rare isoforms. |

| Small RNA Analysis (e.g., miRNA) | 1 - 5 million [6] | Due to their short length and lower complexity, fewer reads are required. |

My Alignment Rate is Low. What Are the Potential Causes and Solutions?

A low uniquely mapped read rate (generally below 60-70% [35]) indicates problems.

- Cause 1: Poor Read Quality or Adapter Contamination. Solution: Re-inspect the FastQC report, particularly the "Per base sequence quality" and "Adapter content" modules [35]. Re-trim your reads using fastp or Trimmomatic with appropriate adapter sequences [34] [35].

- Cause 2: Reference Genome Mismatch. Solution: Ensure the reference genome and annotation file are compatible (e.g., same naming conventions like "chr1" vs "1") and from the same source/version [34]. Use the most up-to-date files available.

- Cause 3: High Levels of RNA Degradation. Solution: Check the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) of your samples prior to sequencing. Degraded samples will have a biased representation of transcripts and map poorly. Ensure all reagents and equipment are RNase-free to prevent degradation during extraction [40].

How Can I Account for Unwanted Variation in My Dataset During Differential Expression Analysis?

Sample-level quality control is essential to identify major sources of variation before performing differential expression testing [37].

- Technique 1: Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Plot the samples using the first few principal components. Ideally, replicates should cluster together, and the condition of interest should be the primary source of variation. If other factors (e.g., batch, sex, library preparation date) are driving the variation, they can be included in the DESeq2 design formula to regress out their effect [37].

- Technique 2: Hierarchical Clustering. This heatmap displays correlation between all sample pairs. Samples generally show high correlations (>0.80). Samples with low correlation to their group may be outliers and warrant further investigation [37].

I Suspect RNA Degradation During Extraction. How Can I Confirm and Prevent This?

RNA degradation is a common issue that compromises data quality.

- Causes: RNase contamination, improper sample storage, repeated freezing and thawing, or long storage times [40].

- Confirmation: Check the FastQC report. A sharp drop in sequence quality or per-base sequence content at the 5' end can indicate degradation. Bioanalyzer traces (e.g., low RIN) from the original sample are a definitive check.

- Prevention:

What is the Difference Between Normalization Methods, and Which One Should I Use?

Normalization is critical for accurate gene expression comparisons. Different methods account for different "uninteresting" factors.

Table 3: Common RNA-seq Normalization Methods

| Method | Accounted Factors | Recommended Use | Not Recommended For |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPM (Counts Per Million) | Sequencing depth | Gene count comparisons between replicates of the same sample group. | Within-sample comparisons or DE analysis [37]. |

| TPM (Transcripts Per Million) | Sequencing depth, Gene length | Gene count comparisons within a sample or between samples of the same group [37]. | DE analysis [37]. |

| RPKM/FPKM | Sequencing depth, Gene length | Gene count comparisons between genes within a sample [37]. | Between-sample comparisons or DE analysis (values are not comparable between samples) [37]. |

| DESeq2's Median of Ratios | Sequencing depth, RNA composition | Gene count comparisons between samples and for DE analysis [37]. | Within-sample comparisons [37]. |

| edgeR's TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) | Sequencing depth, RNA composition | Gene count comparisons between samples and for DE analysis [37]. | Within-sample comparisons [37]. |

For differential expression analysis with tools like DESeq2 or edgeR, you should use the built-in normalization method (Median of Ratios or TMM, respectively). These methods are robust to library size and RNA composition biases, which is essential for accurate between-sample comparisons [36] [37].

A fundamental research problem in many RNA-seq studies is the identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between distinct sample groups. The choice of computational tools for this task is critical, as it can markedly affect the outcome of the data analysis [41]. Numerous statistical methods have been developed, each with unique statistical approaches and assumptions. Understanding the differences between popular tools like edgeR, DESeq2, and limma-voom will help you select the most appropriate method for your experimental context, ensuring robust and reliable biological conclusions [42].

Understanding the Core Statistical Approaches

Differential expression analysis tools primarily use parametric or non-parametric approaches to model RNA-seq count data and test for significant changes.

- Parametric Methods: These assume that the count data follows a specific probability distribution. Tools like DESeq2 and edgeR use a negative binomial (NB) distribution to model counts, as this distribution effectively accounts for biological variability and overdispersion (where the variance between replicated measurements is higher than the mean) [41] [43]. They then employ empirical Bayes techniques to "shrink" or moderate the estimates of gene-wise dispersion towards a common trend, improving stability for experiments with small numbers of replicates [41] [43].

- Transformation-Based Methods: The limma-voom pipeline uses a hybrid approach. It applies a voom transformation to convert normalized count data into continuous log2-counts per million (log-CPM) values. Subsequently, it uses precision weights to account for the mean-variance relationship in the data, enabling the application of powerful linear modeling and empirical Bayes methods originally developed for microarray data [41] [42].

- Non-Parametric Methods: Tools like NOISeq and SAMseq make fewer assumptions about the underlying data distribution. They are often based on resampling techniques or model the null distribution of noise directly from the data, which can be advantageous when parametric assumptions are violated [41] [43].

Comparative Performance of Differential Expression Methods

Independent evaluations have benchmarked the performance of various methods across different experimental conditions. Key performance metrics include the ability to control the False Discovery Rate (FDR)—the expected proportion of false positives among all detections—and statistical power, the probability of correctly detecting a truly differentially expressed gene [41] [43].

Performance Based on Sample Size

The table below summarizes findings from a 2022 evaluation of eight popular methods, highlighting how performance varies with sample size when data follows a negative binomial distribution [43].

| Sample Size (per group) | Recommended Method(s) | Key Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | EBSeq | Better FDR control, power, and stability compared to other methods with very small sample sizes [43]. |

| 6 or 12 | DESeq2 | Performs slightly better than other methods in terms of FDR control and power as sample size increases [43]. |

| Very Small (e.g., 2) | edgeR | Designed to be efficient with small sample sizes; exact tests can work with as few as 2 replicates [42] [43]. |

| Large (e.g., >20) | Wilcoxon rank-sum test | In population-level studies with large samples, parametric methods (DESeq2, edgeR) may fail to control FDR; non-parametric Wilcoxon test is more robust to outliers and provides better FDR control [44]. |

General Comparisons Between Widely-Used Tools

The following table provides a direct comparison of the three most widely-used tools—DESeq2, edgeR, and limma-voom—based on their core characteristics [42] [45].

| Aspect | DESeq2 | edgeR | limma-voom |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Statistical Approach | Negative binomial GLM with empirical Bayes shrinkage [42]. | Negative binomial model with empirical Bayes moderation [42]. | Linear modeling with empirical Bayes moderation on voom-transformed counts [42]. |

| Default Normalization | Median-of-ratios method (corrects for library composition) [20]. | TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values; corrects for library composition) [41] [20]. | TMM normalization, followed by voom transformation [42]. |

| Ideal Sample Size | ≥3 replicates, performs well with more [42] [43]. | ≥2 replicates, efficient with small samples [42] [43]. | ≥3 replicates per condition [42]. |

| Best Use Cases | Moderate to large sample sizes, high biological variability, subtle expression changes [42]. | Very small sample sizes, large datasets, technical replicates [42]. | Small sample sizes, multi-factor experiments, time-series data, integration with other omics [42]. |

| Computational Efficiency | Can be computationally intensive for large datasets [42]. | Highly efficient, fast processing [42]. | Very efficient, scales well with large-scale datasets [42]. |

| Key Limitations | Can be conservative in fold change estimates; FDR control can be exaggerated in large population studies [42] [44]. | Requires careful parameter tuning; common dispersion may miss gene-specific patterns [42]. | Requires careful QC of the voom transformation; may not handle extreme overdispersion well [42]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: My RNA-seq experiment has only 2 replicates per condition. Is differential analysis even possible, and which tool should I use?

While technically possible, analysis with only two replicates greatly reduces the ability to estimate biological variability and control false discovery rates [20]. If you must proceed, edgeR is specifically developed for experiments with very small numbers of replicates and is generally considered the safest choice in this scenario [42] [43]. Its empirical Bayes procedure moderates the degree of overdispersion by borrowing information between genes, which is crucial when per-group sample sizes are minimal [41]. However, you should interpret the results with caution and consider any findings as preliminary until validated.

Q2: I am analyzing data from a population-level study with over 100 samples per group. My colleague warned me that DESeq2/edgeR might have high false discovery rates. Is this true?

Yes, this is a significant and recently highlighted concern. When analyzing human population RNA-seq samples with large sample sizes (dozens to thousands), parametric methods like DESeq2 and edgeR have been shown to have exaggerated false positives, with actual FDRs sometimes exceeding 20% when the target FDR is 5% [44]. This is often due to violations of the negative binomial model assumptions, potentially caused by outliers in the data. In such cases, a non-parametric method like the Wilcoxon rank-sum test is recommended, as it is more robust to outliers and provides better FDR control for large-sample studies [44].

Q3: I keep getting an error that a condition or group is "not found" when I try to run DESeq2 or make contrasts in limma. What is wrong?

This error typically indicates a problem with your sample metadata (colData) or the design formula. The software cannot find the factor level you specified in the model. To troubleshoot:

- Check Factor Levels: Ensure that the condition names in your sample metadata table exactly match those used in your design formula. A common mistake is a typo or incorrect case (e.g., "Control" vs. "control").

- Set the Reference Level: By default, R uses the alphabetically first factor level as the reference (base) group. It is good practice to explicitly set the reference level to your control condition. For example, in R: This ensures "Untreated" is the baseline for comparison [46].

- Verify Data Match: Confirm that the order of samples in your count matrix columns exactly matches the order of rows in your sample metadata. DESeq2 and other packages will not alert you if they are mismatched, leading to incorrect analyses [46] [47].

Q4: How does sequencing depth impact my differential expression analysis, and what is a sufficient depth?

Sequencing depth directly impacts the sensitivity of your analysis. Deeper sequencing captures more reads per gene, increasing your ability to detect lowly expressed transcripts [20]. A depth of 20–30 million reads per sample is often sufficient for standard differential gene expression analysis in many organisms [20] [10]. However, the sufficient depth depends on the complexity of the transcriptome and your specific goals. One study found that while 10 million 75-bp reads detected about 80% of annotated genes in chicken, 30 million reads were required to detect over 90% of genes [10]. If your goal is to detect rare transcripts or splice variants, you may need greater depth. Tools like Scotty can help model power and estimate depth requirements during experimental design [20].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational tools and their roles in a standard RNA-seq differential expression workflow.

| Tool / Resource | Function in Workflow | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| FastQC / MultiQC | Quality Control | Assesses raw sequence data for technical errors, adapter contamination, and overall quality [20]. |

| Trimmomatic / Cutadapt | Read Trimming | Removes adapter sequences and low-quality bases from reads to improve mapping accuracy [20]. |

| STAR / HISAT2 | Read Alignment | Maps (aligns) cleaned sequencing reads to a reference genome [20]. |

| featureCounts / HTSeq | Read Quantification | Counts the number of reads mapped to each gene, generating a raw count matrix [20]. |

| DESeq2 / edgeR / limma | Differential Expression | Statistical analysis of the count matrix to identify genes expressed at different levels between conditions [42] [45]. |

| Salmon / Kallisto | Pseudo-alignment & Quantification | An alternative, faster workflow that estimates transcript abundances without full base-by-base alignment [20] [46]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard DESeq2 Workflow

The following is a detailed protocol for performing differential expression analysis using the DESeq2 package in R, from data input to generating a results table [46] [42].

Step 1: Load Packages and Data

- Install and load the required R packages (

DESeq2,tidyverse). - Load the raw count matrix and the sample information table (metadata). The count matrix should have genes as rows and samples as columns. The metadata must contain the experimental conditions for each sample.

Step 2: Verify and Prepare Data

- Crucially, ensure that the order of samples in the count matrix columns matches the order of rows in the metadata. Use

all(colnames(count_matrix) == metadata$SampleName)to check [46]. - Define the experimental design using a formula, e.g.,

design <- ~ condition. Set the reference level of your factor to the control group usingfactor()andrelevel()[46].

Step 3: Create DESeqDataSet and Filter Genes

- Create a

DESeqDataSetobject from the count matrix, metadata, and design formula. - Filter out genes with very low counts across all samples, as they are uninformative. A common filter is to keep genes with at least a few counts (e.g., >5) in a minimum number of samples [46].

Step 4: Run the Core DESeq2 Analysis

- The main analysis can be performed in a single step using the

DESeq()function. This wrapper executes three steps internally [46]:- Estimation of size factors (for normalization).

- Estimation of dispersion for each gene.

- Fitting of a negative binomial generalized linear model (GLM) and performing Wald tests.

- Alternatively, you can run these steps individually for more control over parameters.

Step 5: Extract and Interpret Results

- Use the

results()function to extract a table of results, including log2 fold changes, p-values, and adjusted p-values (FDR). You can specify significance thresholds (e.g.,alpha=0.05) and fold change thresholds here [46]. - The results table can be sorted by adjusted p-value and exported for further analysis and visualization.

Visual Workflow and Decision Guide

The following diagram illustrates a standard RNA-seq data analysis workflow, from raw data to differential expression results.

Diagram 1: Standard RNA-seq Differential Expression Analysis Workflow.

The decision of which differential expression tool to use depends heavily on your experimental design. The following logic can guide your selection.

Diagram 2: A Decision Guide for Selecting a Differential Expression Method.

Solving Common Pitfalls: Strategies for Optimizing Depth and Coverage

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the main sources of technical noise in RNA-seq? Technical noise in RNA-seq arises from multiple sources in the experimental pipeline. It is commonly categorized into three areas:

- Molecular noise: Stemming from upfront processes like cell lysis, reverse transcription, and cDNA amplification. This includes pipetting errors, technician variability, and amplification bias.

- Machine noise: Introduced by the sequencing process itself, such as cluster generation on the flow cell and lane-to-lane variability.

- Analysis noise: Generated during bioinformatic processing through steps like quality trimming, alignment parameters, and data normalization [48].

How does technical noise differ from biological noise? Biological noise refers to the natural, cell-to-cell variability in gene expression within an isogenic population, predominantly attributed to stochastic fluctuations in transcription [49]. Technical noise is non-biological variability injected by the experimental and computational process. One study estimated that in a well-optimized RNA-seq pipeline, process noise (a component of technical noise) can introduce approximately 24-30% variability in the data. In contrast, biological noise is often 5 to 10 times greater than this process noise [48].

Why is it crucial to account for technical noise in single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq)? scRNA-seq is particularly prone to technical biases like dropout events (where a transcript is expressed but not detected) and amplification bias due to the minute starting amount of RNA [50] [51]. These technical effects vary from cell to cell and, if not properly corrected, can confound downstream analyses like differential expression, leading to false positives or negatives [51].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low RNA Input and Yield

This issue is common when working with rare cell populations or limited clinical samples and leads to low sequencing coverage and high technical noise [50].

- Potential Causes and Solutions

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Incomplete homogenization or lysis | Optimize homogenization conditions to ensure complete cell disruption and RNA release [40]. |

| RNA degradation | Ensure all tubes, tips, and solutions are RNase-free. Store samples at -65°C to -85°C and avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles [52] [40]. |

| Low RNA precipitation efficiency | For small tissue or cell quantities, reduce the volume of lysis reagent (e.g., TRIzol) proportionally to prevent excessive dilution. Use glycogen as a carrier to aid precipitation [40]. |

| General low extraction rate | Increase sample lysis time to over 5 minutes at room temperature. Adjust sample input to ensure it is not excessive for the reagent volume [40]. |

- Experimental Protocol: Improving RNA Quality from Suboptimal Samples

- Quality Control: Assess RNA integrity using an Agilent Bioanalyzer. A high-quality sample should have an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 6 [52].

- Library Prep Selection: For degraded samples (e.g., FFPE tissues), use specialized single-cell combinatorial indexing (SCI) or random priming protocols that perform better with fragmented RNA [50].

- Pre-amplification: Incorporate a pre-amplification step during cDNA synthesis to increase the amount of material before library construction [50].

Issue: Amplification Bias

Amplification bias causes skewed representation of transcripts, overestimating highly expressed genes and underestimating low-abundance ones [50].

- Potential Causes and Solutions

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Stochastic variation in PCR amplification | Use Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs). UMIs are short random sequences that tag individual mRNA molecules before amplification, allowing bioinformatic correction for duplicate reads [50] [51]. |

| Non-linear amplification | Use spike-in controls. These are synthetic RNA molecules added at known concentrations to the sample, providing an internal standard to model and correct for amplification efficiency and technical variation [51]. |

| Library preparation protocol | Standardize library preparation protocols and optimize the number of amplification cycles to minimize bias [50]. |

- Experimental Protocol: Using Spike-in Controls

- Selection: Choose a spike-in kit (e.g., ERCC spike-ins) that covers a wide range of concentrations [51].

- Addition: Add a fixed volume of spike-in solution to the cell lysis buffer at the very beginning of the workflow [51].

- Analysis: Use statistical frameworks (e.g., TASC) that leverage the known concentrations of spike-ins to model and subtract cell-specific technical noise, including amplification bias and dropout rates [51].

Issue: Dropout Events

Dropouts are false negatives where a transcript expressed in a cell fails to be captured or amplified, which is especially problematic for detecting lowly expressed genes and rare cell populations [50].

- Potential Causes and Solutions

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Low capture efficiency of reverse transcription | Use specialized protocols like SMART-seq, which have higher sensitivity and are better at detecting low-abundance transcripts [50]. |

| Stochastic sampling of lowly expressed transcripts | Increase sequencing depth. Deeper sequencing provides a higher chance of capturing rare transcripts [53]. For diagnostic-level detection, ultra-deep sequencing (up to 1 billion reads) may be necessary to saturate gene detection [53]. |

| Inefficient primer binding | Computational imputation methods can be applied. These methods use statistical models and machine learning to predict the expression levels of missing genes based on patterns in the data from other cells and genes [50]. |

- Experimental Protocol: A Scalable Approach to Mitigate Dropouts

- Design: Plan sequencing depth based on study goals. While 30-60 million reads per sample is standard, aim for 100-200 million reads for an in-depth view of the transcriptome [6].

- Validation: For key findings, especially involving low-expression genes, validate results using an orthogonal method like single-molecule RNA FISH (smFISH), which is considered a gold standard for mRNA quantification due to its high sensitivity [49].

- Normalization: Apply scRNA-seq-specific normalization algorithms (e.g., SCTransform, scran, BASiCS) that are designed to account for varying sequencing depths and dropout events across cells [49] [50].

Managing Sequencing Depth and Coverage to Control Noise

The following diagram illustrates the strategic relationship between sequencing depth, technical noise, and the solutions discussed in this guide.

Strategic Flow for Noise Management

Key Recommendations:

- Define Study Objectives: The required depth depends on the goal. Gene expression profiling may need 5-25 million reads per sample, while novel transcript assembly or detecting rare variants may require 100-200 million reads or more [6] [53].

- Understand the Difference:

- Sequencing Depth (Read Depth): The average number of times a specific nucleotide is read. Higher depth increases confidence in base calling and is crucial for detecting rare variants [1].

- Coverage: The percentage of the target genome or transcriptome that has been sequenced at least once. High coverage ensures no genomic regions are missed [1].

- Balance Depth and Cost: Ultra-deep sequencing (e.g., 1 billion reads) can approach saturation for gene detection but may not be cost-effective for all studies. A balance must be struck based on the specific research question [53].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Managing Technical Noise |

|---|---|

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random barcodes that label individual mRNA molecules before amplification, allowing for accurate digital counting and correction for amplification bias and PCR duplicates [50] [51]. |

| Spike-in Controls (e.g., ERCC) | Synthetic RNA controls added at known concentrations. They enable precise modeling of technical variation, including amplification efficiency and dropout rates, for per-cell normalization [51]. |

| Stranded Library Prep Kits | Library preparation protocols that preserve the strand information of transcripts. This is critical for accurate transcriptome assembly, distinguishing overlapping genes on opposite strands, and reducing misidentification errors [52]. |

| Ribosomal RNA Depletion Kits | Kits that remove abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which can constitute over 95% of total RNA. This greatly increases the sequencing coverage of mRNA and non-coding RNA of interest [52]. |

| Poly-A Selection Kits | Kits that enrich for messenger RNA (mRNA) by targeting the poly-A tail. This simplifies the transcriptome by focusing on protein-coding genes, but may miss non-polyadenylated RNAs [52]. |

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), achieving uniform coverage is fundamental for accurate transcript quantification and detection. However, two persistent technical challenges routinely compromise data integrity: the under-representation of GC-rich regions (sequences with high guanine and cytosine content) and 3' bias (the preferential sequencing of the 3' end of transcripts) [54] [55]. These biases are not merely nuisances; they directly impact the reliability of your measurements for differential expression analysis and novel transcript detection. Effectively managing them is a critical component of optimizing sequencing depth and coverage, ensuring that your data is both comprehensive and representative of the true biological state [19] [11]. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting strategies to overcome these challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why are GC-rich regions problematic in sequencing? GC-rich sequences (typically defined as ≥60% GC content) are challenging due to their biochemical properties. The three hydrogen bonds in G-C base pairs confer higher thermal stability than the two bonds in A-T pairs, making these regions resistant to denaturation during PCR cycling [56] [57]. This stability promotes the formation of stable secondary structures, such as hairpin loops, which can block the progression of the polymerase enzyme during cDNA synthesis or amplification, leading to dropouts or low coverage in these areas [56] [54].

Q2: What are the primary causes of 3' bias in RNA-seq libraries? 3' bias, also known as positional bias, often arises from the library preparation method [55]. When RNA is degraded or fragmented, it often breaks from the 5' end, leading to a surplus of 3' fragments [54]. Furthermore, protocols that use oligo-dT primers for reverse transcription are inherently designed to capture the 3' end of polyadenylated transcripts. Even with random hexamer priming, inefficiencies can lead to an under-representation of the 5' ends [54] [58].

Q3: How do GC bias and 3' bias affect the interpretation of my sequencing data? These biases distort the true representation of transcript abundance. GC bias can lead to the false absence of variants or under-expression of genes located in GC-rich regions, which is particularly critical in studies of gene promoters, often found in GC-rich areas [57]. 3' bias prevents a full-length view of transcripts, complicating isoform-level analysis and can lead to inaccurate gene-level counts if the bias is not consistent across all samples [54] [55]. Both biases can introduce systematic errors that confound differential expression analysis.

Q4: Can increasing sequencing depth compensate for these biases? While increasing depth can help recover signals from underrepresented transcripts, it is an inefficient and costly solution to a technical problem [19] [11]. Deeper sequencing will proportionally amplify both the true signal and the bias. A more effective strategy is to first optimize the wet-lab protocol to minimize bias during library construction and then use computational tools to correct for any residual bias, ensuring a more accurate and cost-effective outcome [19] [59].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide for GC-Rich Regions

GC-rich regions are a common hurdle in sequencing. The following workflow outlines a systematic approach to diagnose and resolve issues related to amplifying and sequencing these difficult areas.

Diagram 1: A systematic troubleshooting workflow for GC-rich region amplification.