Navigating Bulk RNA-seq Data Normalization: Challenges, Solutions, and Best Practices for Reliable Transcriptomic Analysis

Bulk RNA-seq is a cornerstone of modern transcriptomics, yet its accuracy hinges on appropriate data normalization to overcome significant technical biases.

Navigating Bulk RNA-seq Data Normalization: Challenges, Solutions, and Best Practices for Reliable Transcriptomic Analysis

Abstract

Bulk RNA-seq is a cornerstone of modern transcriptomics, yet its accuracy hinges on appropriate data normalization to overcome significant technical biases. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, detailing the core challenges of normalization—from managing technical variability and selecting methods to integrating data across studies and validating results. We systematically explore foundational concepts, compare widely used methodologies like TPM, FPKM, TMM, and RLE, and offer troubleshooting strategies for complex scenarios, including covariate adjustment and batch effects. By synthesizing recent benchmarking studies and practical considerations, this review empowers scientists to make informed decisions that enhance the reliability of their downstream analyses and biological conclusions.

Why Normalization is Non-Negotiable: Unpacking the Core Challenges in Bulk RNA-seq

Bulk RNA-seq data is affected by multiple technical factors that, if uncorrected, can obscure the true biological signal. These include library size, gene length, and sample composition biases. The core goal of normalization is to adjust the raw count data to eliminate these non-biological sources of variation, enabling valid comparisons of gene expression levels between samples.

This guide addresses the most frequent challenges researchers face during this critical step of the analysis.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

1. What is the fundamental difference between within-sample and between-sample normalization methods?

Within-sample methods, like FPKM and TPM, normalize counts based on features of the individual sample, such as its total count and gene lengths. In contrast, between-sample methods, such as RLE (used by DESeq2) and TMM (used by edgeR), use information across all samples in the experiment to compute scaling factors, under the assumption that most genes are not differentially expressed [1]. Between-sample methods are generally recommended for differential expression analysis.

2. I have an outlier sample that looks very different from my other replicates. Should I remove it before normalization?

Proceed with caution. First, investigate the cause. Use quality control tools like FastQC, MultiQC, or RNA-SeQC to check for technical issues like adapter contamination, low sequencing quality, or high rRNA content [2]. If the outlier is due to a technical failure, removal may be justified. However, if it is a valid biological replicate, normalization methods like TMM and RLE, which are robust to a small number of DE genes, can often handle the situation without removing the sample [1].

3. Can I use quantile normalization, a method from microarrays, on my RNA-seq data?

This is generally not recommended. Using microarray-specific normalization methods like normalizeBetweenArrays() from limma with its "quantile" method on RNA-seq data is not standard practice and can lead to incorrect results [3]. RNA-seq data has different statistical properties, and it is crucial to follow well-tested RNA-seq-specific tutorials and use methods designed for count data, such as those in edgeR or DESeq2 [3].

4. How does normalization affect my downstream analysis beyond differential expression?

The choice of normalization method can significantly impact other types of analyses. For instance, when mapping RNA-seq data onto genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), using between-sample methods (RLE, TMM, GeTMM) resulted in metabolic models with lower variability and more accurate capture of disease-associated genes compared to within-sample methods (TPM, FPKM) [1].

5. My data has known covariates like age, gender, or batch. How should I handle them?

Covariates can be adjusted for during the normalization process. A benchmark study on Alzheimer's disease and lung cancer data demonstrated that applying covariate adjustment to normalized data (for factors like age, gender, and post-mortem interval) improved the accuracy of condition-specific metabolic models derived from the transcriptome [1]. This can often be integrated into the statistical model in tools like DESeq2 or limma.

Normalization Method Comparison

The table below summarizes the key characteristics and recommended use cases for common normalization methods.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Bulk RNA-seq Normalization Methods

| Normalization Method | Type | Key Principle | Commonly Used In | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPM (Transcripts Per Million) [1] | Within-sample | Normalizes for sequencing depth and gene length. | General expression reporting, e.g., ENCODE pipeline [4]. | Comparing expression levels of different genes within a single sample. |

| FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase Million) [1] | Within-sample | Similar to TPM but with a different order of operations. | General expression reporting. | (Largely superseded by TPM for within-sample comparisons). |

| TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) [1] | Between-sample | Assumes most genes are not DE; uses a weighted trim mean of log expression ratios. | edgeR package. |

Differential expression analysis, especially with balanced DE genes. |

| RLE (Relative Log Expression) [1] | Between-sample | Assumes most genes are not DE; median of ratios to a reference sample. | DESeq2 package. |

Differential expression analysis, robust to large numbers of DE genes. |

| GeTMM (Gene length corrected TMM) [1] | Combined | Combines gene-length correction of TPM with between-sample normalization of TMM. | - | Tasks requiring both within-and between-sample comparisons. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Normalization Analyses

Protocol 1: Performing Differential Expression Analysis with DESeq2 (RLE Normalization)

This protocol uses the RLE normalization method inherent to the DESeq2 package to identify differentially expressed genes.

- Load Required Libraries: Install and load the

DESeq2andtximport(if using transcript-level quantifiers like Salmon) packages in R. - Prepare Input Data: Create a data frame (

colData) with sample metadata (e.g., condition, batch). Prepare a table of raw counts or point to the output files from quantification tools like Salmon. - Create DESeq2 Dataset: Use the

DESeqDataSetFromMatrix()orDESeqDataSetFromTximport()function, specifying the count data, sample information, and the experimental design (e.g.,~ condition). - Run Differential Expression Analysis: Execute the core analysis steps—estimation of size factors (RLE normalization), dispersion, and fitting of the negative binomial model—with a single call to the

DESeq()function. - Extract Results: Use the

results()function to extract a table of log2 fold changes, p-values, and adjusted p-values for all genes.

Protocol 2: Generating Condition-Specific Metabolic Models from Normalized Data

This protocol, based on benchmarks from npj Systems Biology and Applications, outlines how to create metabolic models using normalized RNA-seq data and the iMAT algorithm [1].

- Normalize RNA-seq Data: Begin with raw count data. Normalize it using one of the five methods (e.g., RLE, TMM, TPM) as described in the comparison table above.

- Covariate Adjustment (Optional but Recommended): For datasets with covariates like age or gender, perform covariate adjustment on the normalized expression values to remove their influence.

- Map Data to a Metabolic Model: Use the Integrative Metabolic Analysis Tool (iMAT) algorithm. Input the normalized (and optionally adjusted) expression data and a generic human genome-scale metabolic model (GEM).

- Generate Personalized Models: Run iMAT for each sample in your dataset to reconstruct a condition-specific, personalized metabolic model.

- Analyze Model Content: Compare the resulting models (e.g., control vs. disease) to identify significantly affected metabolic reactions and pathways based on the chosen normalization method.

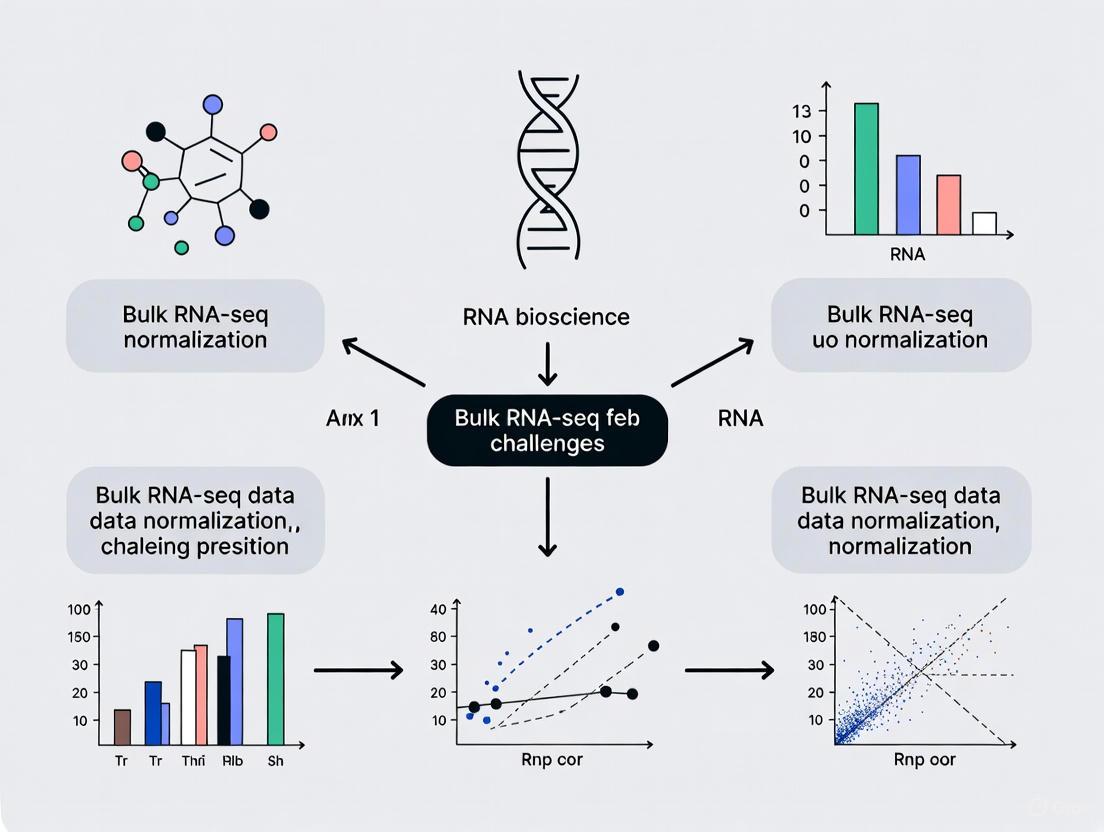

Workflow and Decision Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for approaching bulk RNA-seq data normalization, from data preparation to method selection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 2: Key Tools and Reagents for Bulk RNA-seq Analysis

| Item Name | Category | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| STAR [5] [4] | Alignment Software | A splice-aware aligner that accurately maps RNA-seq reads to a reference genome. |

| Salmon [5] | Quantification Software | A fast tool for transcript-level quantification that uses "pseudo-alignment," handling uncertainty in read assignment. |

| RSEM [5] [4] | Quantification Software | Estimates gene and isoform abundance levels from RNA-seq data, often used with STAR alignments. |

| DESeq2 [1] | R Package for DE Analysis | Performs differential expression analysis using its built-in RLE normalization and a negative binomial model. |

| edgeR [1] | R Package for DE Analysis | Performs differential expression analysis using its built-in TMM normalization and statistical methods. |

| ERCC Spike-In Controls [4] | Research Reagent | Exogenous RNA controls added to samples before library preparation to provide a standard for absolute transcript quantification and quality assessment. |

| FastQC [2] | Quality Control Tool | Provides an initial quality overview of raw sequence data, informing on potential issues like adapter contamination or low-quality bases. |

| MultiQC [2] | Quality Control Tool | Aggregates results from multiple tools (FastQC, STAR, etc.) across all samples into a single, interactive HTML report. |

| RSeQC [2] | Quality Control Tool | Analyzes various aspects of RNA-seq data, including read distribution, coverage uniformity, and strand specificity. |

| nf-core/rnaseq [5] | Workflow Manager | A portable, community-maintained Nextflow pipeline that automates the entire analysis from raw FASTQ files to counts and QC. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Mitigating RNA-Seq Biases

This guide addresses common technical issues related to sequencing depth, gene length, and compositional effects in bulk RNA-Seq experiments, providing practical solutions for researchers.

Q1: How do I determine the optimal sequencing depth for my bulk RNA-Seq experiment?

A: Sequencing depth requirements vary significantly based on your experimental goals and sample quality. The ENCODE standards recommend ≥30 million mapped reads as a baseline for typical poly(A)-selected RNA-Seq, but recent multi-center benchmarking shows real-world applications can require ~40–420 million total reads per library [6]. Use the following guidelines tailored to your specific research objectives [6]:

| Research Objective | Recommended Depth | Read Length | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Gene Expression | 25-40 million reads | 2×75 bp | Sufficient for high-quality RNA (RIN ≥8); stabilizes fold-change estimates [6] |

| Isoform Detection & Splicing | ≥100 million reads | 2×75 bp or 2×100 bp | Required to capture a comprehensive view of splice events [6] |

| Fusion Detection | 60-100 million reads | 2×75 bp (2×100 bp preferred) | Paired-end libraries essential for anchoring breakpoints [6] |

| Allele-Specific Expression | ≥100 million reads | Paired-end | Essential for accurate variant allele frequency estimation [6] |

For degraded RNA samples (e.g., FFPE), increase sequencing depth by 25-50% for DV200 of 30-50%, and use 75-100 million reads for DV200 <30% [6]. When working with limited input RNA (≤10 ng), incorporate UMIs to accurately collapse PCR duplicates during deep sequencing [6] [7].

Q2: How does gene length bias affect my analysis, and should I normalize for it?

A: Gene length significantly impacts count data. Longer genes generate more sequencing fragments, resulting in higher counts regardless of actual expression levels [8]. However, normalization strategies depend on your analytical goals:

- For differential expression analysis (comparing the same gene across samples): Do NOT normalize for gene length. Tools like DESeq2 and edgeR are designed to compare counts of the same gene across samples, where length is constant and normalization would reduce statistical power for longer genes [9].

- For within-sample comparisons (comparing different genes within the same sample): Normalize for gene length using measures like TPM (Transcripts Per Million). This enables meaningful comparison of expression levels between different genes within the same sample [9].

The decision flow below outlines this logic:

Q3: What is compositional bias, and how can I correct for it in my data?

A: Compositional bias is a fundamental artifact where sequencers measure relative, not absolute, abundances [10]. When a few highly abundant features change between conditions, the relative proportions of all other features appear to change artificially, even if their absolute abundances remain constant [10].

Detection: Suspect compositional bias when you observe strong inverse correlations in log-fold changes between highly and lowly expressed features [10].

Correction Strategies:

- Gold Standard: Use spike-in controls (e.g., ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix) added during library preparation. These provide an external reference for absolute quantification [7] [11].

- Computational Correction: Apply scaling normalization methods (e.g., TMM in edgeR, DESeq2's median of ratios) that assume most features are not differentially abundant [10] [12]. For sparse data (e.g., metagenomic 16S surveys), consider empirical Bayes approaches like Wrench [10].

Experimental Workflow: The following diagram illustrates where key biases are introduced during a standard bulk RNA-Seq workflow and where corrections can be applied.

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ERCC Spike-In Mix [7] [11] | External RNA controls with known concentrations to standardize quantification and assess technical variation. | Determining sensitivity, dynamic range, and accuracy; particularly valuable for identifying compositional bias. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) [6] [7] | Short random sequences that tag individual mRNA molecules prior to PCR amplification. | Correcting PCR amplification bias and accurately counting molecules in low-input or deep sequencing (>50 million reads) applications. |

| Ribosomal RNA Depletion Kits | Remove abundant ribosomal RNA to increase sequencing coverage of informative transcripts. | Essential for prokaryotic RNA-Seq, non-polyA transcripts (e.g., lncRNAs), and degraded samples (FFPE) where polyA selection is inefficient [6] [7]. |

| DV200 Metric | Measures the percentage of RNA fragments >200 nucleotides; alternative to RIN for degraded RNA. | RNA quality assessment for FFPE and other compromised samples; guides protocol selection and sequencing depth [6]. |

| Poly(A) Selection Beads | Enrich for polyadenylated mRNA molecules from total RNA. | Standard approach for eukaryotic mRNA sequencing when RNA quality is high (RIN ≥8, DV200 >70%) [6] [7]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the fundamental goal of RNA-seq normalization? The primary goal is to adjust raw transcriptomic data to account for technical factors that may mask actual biological effects and lead to incorrect conclusions. Normalization ensures that differences in read counts reflect true biological variation rather than technical artifacts like sequencing depth, transcript length, or batch effects [13] [14].

2. Can I use within-sample normalized data (like TPM) for direct between-sample comparisons? No, this is a common misunderstanding. Within-sample normalization methods like TPM and FPKM are suitable for comparing the relative expression of different genes within the same sample. However, for comparing the expression of the same gene between different samples, between-sample normalization methods (like TMM or RLE) are required, as they account for additional technical variation such as differences in sequencing depth and RNA composition [13] [15].

3. What happens if I skip normalization or use an inappropriate method? Errors in normalization can have a significant impact on downstream analysis. It can lead to a high rate of false positives or false negatives in differential expression analysis, mask true biological differences, or create the false appearance of differential expression where none exists [13] [14] [1].

4. Is there a single "best" normalization method for all experiments? There is no consensus on a single best-performing normalization method for all scenarios [11] [16]. The choice depends on the specific features of your dataset and the biological question. It is good practice to assess the performance of different normalization methods using data-driven metrics relevant to your downstream analysis [11] [1].

5. My data comes from multiple studies. What is the most important normalization step? When integrating data from multiple independent studies, normalization across datasets (batch-effect correction) is critical. Batch effects, often introduced by different sequencing times, methods, or facilities, can be the greatest source of variation and can mask true biological differences if not corrected [13] [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inconsistent Differential Expression Results After Normalization

Symptoms: Your list of differentially expressed (DE) genes changes drastically when you switch normalization methods, or you get counter-intuitive results (e.g., globally down-regulated genes when one condition is known to be highly active).

Diagnosis: This often indicates that the assumptions of your chosen normalization method are being violated. For example:

- Global-scaling methods (TMM, RLE) assume that most genes are not differentially expressed [14] [1]. If a large fraction of genes are truly DE in your experiment (e.g., a global shift in expression), these methods can produce misleading results [14].

- Composition bias may be present, where a few highly expressed genes in one condition consume a large share of the sequencing reads, making non-DE genes in that condition appear down-regulated [14].

Solutions:

- Assumption Check: Investigate the biology of your experiment. If a global shift in expression is expected, be cautious with methods that assume a stable transcriptome background.

- Method Comparison: Run your differential expression pipeline with multiple between-sample normalization methods (e.g., TMM, RLE). Compare the results and investigate genes that are consistently identified.

- Spike-in Controls: If available, use spike-in RNA controls to create an absolute standard for normalization, which can be more robust in these situations [11] [18].

Problem 2: High Variability in Model Outputs When Mapping to Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs)

Symptoms: When using normalized RNA-seq data to create condition-specific metabolic models (e.g., with iMAT or INIT algorithms), the number of active reactions varies widely between samples, leading to unstable predictions.

Diagnosis: This is frequently caused by using within-sample normalization methods (TPM, FPKM) for this purpose. These methods do not adequately control for technical variability between samples, which propagates into the metabolic models [1].

Solutions:

- Switch Normalization Method: Use between-sample normalization methods like RLE (from DESeq2), TMM (from edgeR), or GeTMM. Benchmarking studies show these methods produce metabolic models with lower variability and can more accurately capture disease-associated genes [1].

- Covariate Adjustment: Account for known covariates like age, gender, or post-mortem interval during the normalization process, as this can further improve the consistency and accuracy of the generated models [1].

Problem 3: Poor Integration of Multiple Datasets

Symptoms: When you combine data from different batches or studies, samples cluster strongly by batch or study origin instead of by biological condition in dimensionality reduction plots (e.g., PCA).

Diagnosis: Strong batch effects are confounding your analysis. Within-dataset normalization is not sufficient to remove these systematic technical differences [13] [17].

Solutions:

- Apply Batch-Effect Correction: Use specialized tools like ComBat (from the

svapackage) or Limma'sremoveBatchEffectfunction after performing within-dataset normalization [13]. - Experimental Design: For future experiments, use a blocking design and multiplex samples from all conditions across sequencing lanes and batches to minimize confounding [17].

Normalization Methodologies at a Glance

The following table summarizes the core methodologies for the three tiers of normalization.

Table 1: Summary of RNA-seq Normalization Tiers

| Normalization Tier | Primary Goal | Common Methods | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Within-Sample [13] | Enable comparison of expression between different genes within the same sample. Corrects for gene length and sequencing depth. | TPM, FPKM/RPKM | Not suitable for between-sample comparisons. TPM is generally preferred over FPKM as the sum of all TPMs is constant across samples [13] [15]. |

| Between-Sample [13] [14] | Enable comparison of expression for the same gene between different samples. Corrects for library size and RNA composition. | TMM [1], RLE (used in DESeq2) [1], GeTMM [1] | Often assume most genes are not differentially expressed. Performance can be poor if this assumption is violated [14]. |

| Across Datasets [13] | Remove batch effects when integrating data from different studies, sequencing runs, or facilities. | ComBat [13], Limma [13] | Requires knowledge of the batch variables. Should be applied after within-dataset normalization. |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Normalization Methods

Given that there is no single best method, a robust analysis pipeline should include an evaluation of different normalization approaches. Below is a general protocol for benchmarking normalization methods in a differential expression analysis context.

Protocol: Evaluating Normalization Method Performance

- Data Preparation: Begin with a raw count matrix from your bulk RNA-seq experiment.

- Apply Multiple Normalizations: Normalize the dataset using several between-sample methods. Common choices include:

- TMM: Implemented in the

edgeRpackage with thecalcNormFactorsfunction. - RLE: Used by default in the

DESeq2package (via theestimateSizeFactorsfunction). - GeTMM: A method that combines gene-length correction with TMM-like between-sample normalization [1].

- TMM: Implemented in the

- Downstream Analysis: Perform differential expression analysis on each normalized dataset using the corresponding statistical framework (e.g.,

edgeRfor TMM,DESeq2for RLE). - Performance Assessment: Evaluate the results using data-driven metrics. Common approaches include:

- Clustering and Visualization: Use PCA plots to see if normalization effectively separates samples by biological condition rather than technical artifacts.

- Evaluation Metrics: Assess the performance using metrics like the Silhouette Width (for cluster separation) and the K-nearest neighbor batch-effect test (to check for residual batch effects) [11].

- Biological Validation: Compare the lists of differentially expressed genes to known biological pathways or prior knowledge to assess biological relevance [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Tools for RNA-seq Normalization

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Normalization | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Spike-in RNA Controls (e.g., ERCCs) [11] | Exogenous RNA molecules added in known quantities to each sample. Provide an absolute standard to distinguish technical from biological variation and to normalize data, especially in complex scenarios. | Must be added during library preparation. Not feasible for all sequencing platforms [11]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) [11] | Random barcodes ligated to each mRNA molecule during reverse transcription. Allow for accurate counting of original mRNA molecules by correcting for PCR amplification biases. | Commonly used in droplet-based scRNA-seq protocols (e.g., 10X Genomics). Less common in bulk RNA-seq but powerful for molecular counting [11] [16]. |

| Library Quantification Kits (e.g., qPCR) [17] | Precisely measure the concentration of sequencing libraries before pooling. Helps minimize technical variation by ensuring libraries are diluted to the same concentration, reducing lane-to-lane and flow-cell effects. | Critical for a balanced multiplexed sequencing run [17]. |

Logical Workflow for Normalization

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for applying the three tiers of normalization in an RNA-seq analysis pipeline.

Diagram 1: RNA-seq Normalization Workflow

Relationship Between Normalization Types and Analysis Goals

Different downstream analyses have different requirements for which normalization tier is most critical. This diagram maps the primary focus for common analytical goals.

Diagram 2: Normalization Focus for Analysis Goals

By understanding these three distinct tiers of normalization—within-sample, between-sample, and across datasets—researchers can make informed decisions that are critical for generating accurate, reliable, and biologically meaningful results from their RNA-seq experiments.

In bulk RNA-seq analysis, normalization is not merely a preliminary step but a foundational computational process that corrects for technical variations to enable meaningful biological comparisons. The choice of normalization method directly and measurably influences every subsequent analysis, from differential expression to pathway mapping. This guide addresses common challenges and provides troubleshooting advice for researchers navigating the impact of normalization decisions within their thesis projects.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is normalization essential in bulk RNA-seq analysis? Normalization adjusts raw read counts to account for technical variability, such as differences in sequencing depth (total number of reads per sample) and RNA composition (the relative abundance of different RNA molecules in a sample) [15]. Without correct normalization, observed differences in gene expression can be technically driven rather than biological, leading to false conclusions in downstream analysis [14].

2. My PCA plot shows poor separation between experimental conditions. Could normalization be the cause? Yes. The choice of normalization method can significantly impact the outcome of exploratory analyses like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [19]. Different normalization techniques alter the correlation structure of the data, which in turn affects the principal components and the clustering of samples in the reduced-dimensional space. If the assumed data characteristics by the normalization method do not hold (e.g., the assumption that most genes are not differentially expressed), the resulting PCA may fail to reveal true biological separation [14] [19].

3. How does normalization affect differential expression analysis? Normalization has the most substantial impact on differential expression analysis, even more than the choice of subsequent test statistic [14]. Methods like DESeq2's RLE and edgeR's TMM make specific statistical assumptions about the data. If these assumptions are violated—for instance, if a global shift in expression occurs—the error propagates, inflating false positives or negatives [14]. One study found that normalization was the largest statistically significant source of variation in gene expression estimation accuracy [20].

4. I am mapping expression data to genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs). Does normalization matter? Absolutely. Benchmarking studies show that the normalization method directly affects the content and predictive accuracy of condition-specific GEMs generated by algorithms like iMAT and INIT [1]. Between-sample methods (RLE, TMM) produce models with lower variability in the number of active reactions and more accurately capture disease-associated genes compared to within-sample methods (TPM, FPKM) [1].

5. When should I use spike-in controls for normalization? Spike-in controls are synthetic RNA molecules added to your sample in known quantities. They can be valuable when the assumption that "most genes are not differentially expressed" is violated, such as in experiments with global transcriptional shifts [21]. However, their use requires caution. Technical variability can affect spike-in reads, and they must be affected by technical factors in the same way as endogenous genes to be reliable [21]. Methods like Remove Unwanted Variation (RUV) that use spike-ins as negative controls can help account for more complex nuisance technical effects [21].

Troubleshooting Common Normalization Problems

Problem 1: Inflated False Positive Rates in Differential Expression

Symptoms: An unexpectedly high number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs), many of which are lowly expressed and lack biological plausibility.

Diagnosis: This often results from a violation of the normalization method's core assumptions. For example, TMM and DESeq2 assume that the majority of genes are not differentially expressed [14] [15]. In experiments where this is not true (e.g., extreme treatments, global shifts), these methods can perform poorly.

Solutions:

- Use Spike-in Controls: If available, employ a control-based method like RUVg [21].

- Explore Alternative Methods: Consider a non-parametric method like quantile normalization, which makes different assumptions about the data distribution [13] [15].

- Filter Genes: Prior to normalization, filter out lowly expressed genes that contribute disproportionately to noise using a function like

filterByExprfrom edgeR [22].

Problem 2: Batch Effects Masking Biological Signal

Symptoms: Samples cluster by batch (e.g., sequencing date, library preparation kit) instead of by experimental condition in a PCA plot.

Diagnosis: Standard global scaling normalization methods (e.g., TMM, RLE) primarily correct for sequencing depth but may not account for more complex technical artifacts introduced by batch processing [21].

Solutions:

- Apply Batch Correction: After between-sample normalization, use a batch-effect correction tool like ComBat (from the

svapackage) or removeBatchEffect (from thelimmapackage) to account for known batches [13] [21]. - Use RUV Methods: The RUV family of methods can simultaneously estimate and adjust for unknown sources of unwanted variation using control genes or samples [21].

Problem 3: Inconsistent Results in Pathway and Metabolic Analysis

Symptoms: Pathway enrichment analysis or metabolic model predictions are unstable and vary drastically with different normalization inputs.

Diagnosis: Within-sample normalization methods like FPKM and TPM can introduce high variability in the scaled counts across samples, which propagates into functional analyses [1].

Solutions:

- Switch to Between-Sample Methods: For downstream tasks like building metabolic models with iMAT or INIT, use RLE, TMM, or GeTMM, which demonstrate higher consistency and accuracy [1].

- Validate Findings: Cross-validate key pathway results using a different between-sample normalization method to ensure robustness.

Comparative Analysis of Normalization Methods

Table 1: Characteristics and Best Practices for Common Normalization Methods

| Method | Class | Key Principle | Best For | Major Assumption | Downstream Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPM/FPKM [13] [15] | Within-Sample | Normalizes for gene length and sequencing depth. | Comparing gene expression within a single sample. | Total RNA output is comparable between samples. | Not recommended for DE; high variability in metabolic model reactions [1]. |

| TMM [13] [15] | Between-Sample | Uses a trimmed mean of log-expression ratios (M-values) against a reference sample. | Datasets with different RNA compositions or a few highly expressed genes. | The majority of genes are not differentially expressed. | Robust performance in DE and metabolic modeling [1]. |

| RLE (DESeq2) [1] [15] | Between-Sample | Calculates a size factor as the median of ratios of counts to a geometric mean. | Most standard experiments, especially with small sample sizes. | The majority of genes are not differentially expressed. | Robust performance in DE and metabolic modeling; low model variability [1]. |

| Quantile [13] [15] | Between-Sample | Forces the distribution of gene expression to be identical across all samples. | Complex experimental designs with many samples. | Observed distribution differences are technical, not biological. | Reduces technical variation for multivariate analysis. |

| RUV [21] | Between-Sample | Uses factor analysis on control genes/samples to estimate and remove unwanted variation. | Experiments with global shifts, known/unknown batch effects, or spike-in controls. | Technical effects impact control genes and regular genes similarly. | Improves DE accuracy and sample clustering in complex scenarios. |

Table 2: Impact of Normalization on Downstream Applications (Based on Benchmark Studies)

| Application | Key Performance Metric | Top-Performing Methods | Poorly Performing Methods | Evidence Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Expression | Accuracy/Precision of fold-change, FDR control | RLE (DESeq2), TMM (edgeR) | FPKM, TPM (for DE analysis) | [20] [15] |

| Metabolic Model (iMAT/INIT) | Accuracy in capturing disease genes, model stability | RLE, TMM, GeTMM | FPKM, TPM | [1] |

| Principal Component Analysis | Biological interpretability, cluster separation | Method-dependent; no single best | Varies by dataset | [19] |

Essential Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Evaluating Normalization Performance Using SeQC Benchmark Data

This protocol is adapted from large-scale consortium studies to quantitatively evaluate a normalization method's impact on gene expression estimation [20].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- SEQC Benchmark Dataset: Publicly available data (e.g., from Sequence Read Archive under project SRP010938) consisting of reference RNA samples with validated properties [20].

- qPCR Gold-Standard: A subset of genes with validated expression levels via qPCR.

- Software: R/Bioconductor with packages like

DESeq2,edgeR, andlimma.

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Download the SEQC benchmark dataset (Samples A and B).

- Pipeline Application: Process the raw reads through your chosen alignment and quantification pipeline.

- Normalization: Apply the normalization methods you wish to evaluate (e.g., TMM, RLE, FPKM).

- Metric Calculation:

- Accuracy: Calculate the deviation of RNA-seq-derived log ratios (e.g., A vs. B) from the corresponding qPCR-based log ratios. A smaller deviation indicates higher accuracy.

- Precision: Compute the coefficient of variation (CoV) of gene expression across technical replicate libraries. A smaller CoV indicates higher precision.

- Downstream Correlation: Correlate the accuracy and precision metrics with the performance of a downstream task, such as predicting clinical outcomes. Pipelines with better metrics typically yield better downstream results [20].

Protocol 2: Assessing Count-Depth Relationship in Your Dataset

A key assumption of global scaling methods is a consistent relationship between gene counts and sequencing depth. This protocol checks for violations.

Methodology:

- Plot Raw Data: Before normalization, create a scatter plot of log (non-zero counts +1) for each gene against the log sequencing depth for each sample.

- Check for Trends: Visually inspect if the relationship between expression and depth is consistent across all genes or if there are systematic patterns where lowly and highly expressed genes show different trends.

- Post-Normalization Check: Apply your chosen normalization method and plot the normalized data in the same way. A successful normalization should remove the dependence of expression counts on sequencing depth. If systematic trends persist, consider a method like SCnorm that groups genes with similar count-depth relationships for normalization [23].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the logical process for diagnosing and addressing common normalization-related issues in an RNA-seq analysis.

Troubleshooting Workflow for RNA-seq Normalization

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Software Tools

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Use Case in Normalization Context |

|---|---|---|

| ERCC Spike-in Controls [21] | A set of 92 synthetic RNA transcripts at known concentrations. | Serves as negative controls for methods like RUV to estimate unwanted variation. |

| SEQC Benchmark Dataset [20] | A well-characterized RNA-seq dataset with qPCR validation. | A gold standard for benchmarking normalization accuracy and precision. |

| DESeq2 (R package) [15] | A package for differential expression analysis. | Implements the RLE normalization method for between-sample comparison. |

| edgeR (R package) [15] | A package for differential expression analysis. | Implements the TMM normalization method. |

| sva (R package) [13] [21] | A package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation. | Contains ComBat and surrogate variable analysis (sva) for post-normalization adjustment. |

| MultiQC [22] | A tool to aggregate results from multiple QC tools. | Assesses overall sample quality and identifies outliers before normalization. |

A Practical Guide to Bulk RNA-seq Normalization Methods: From TPM to TMM

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are TPM and FPKM, and how do they differ?

A1: TPM (Transcripts Per Million) and FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million fragments mapped) are both within-sample normalization methods designed to make gene expression counts comparable within a single sample by accounting for two key technical biases: sequencing depth (the total number of sequenced fragments) and gene length (the length of the transcript) [24] [25] [26].

The core difference lies in the order of operations during calculation [25]:

- FPKM first normalizes for sequencing depth (to get "Fragments Per Million") and then normalizes for gene length.

- TPM first normalizes for gene length (to get "Transcripts Per Kiloby") and then normalizes for sequencing depth.

This subtle difference has a profound consequence: the sum of all TPM values in a sample is always constant (1 million), allowing you to directly compare the proportion of transcripts a gene constitutes across different samples. With FPKM, the sum of normalized values can vary from sample to sample, making such proportional comparisons difficult [25].

Q2: When is it appropriate to use TPM or FPKM?

A2: The consensus from multiple comparative studies is that TPM and FPKM are primarily suited for within-sample comparisons [26]. The table below outlines their appropriate and inappropriate use cases.

Table: Appropriate Use Cases for TPM and FPKM

| Application | Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Comparing expression of different genes within the same sample | Appropriate [26] | Controls for gene length and sequencing depth, allowing you to ask "Which gene is more highly expressed in this specific sample?" |

| Comparing expression of the same gene across different samples | Not Recommended [27] [26] | Values are relative and can be skewed by the composition of the total RNA population in each sample, leading to inaccurate comparisons. |

Q3: What are the common pitfalls of misusing TPM/FPKM for cross-sample comparison?

A3: Using TPM or FPKM for cross-sample comparison is a common misconception, as these values are relative abundances and not absolute measurements [27]. The primary pitfall is that the expression value for a gene depends on the expression levels of all other genes in that sample.

For example, if a very few genes are extremely highly expressed in one sample, they "use up" a large portion of the "per million" count. This artificially deflates the TPM/FPKM values of all other genes in that sample, making it appear as if they are less expressed compared to another sample with a more balanced transcript repertoire [27]. This is particularly problematic when comparing data from different sample preparation protocols, such as poly(A)+ selection versus rRNA depletion, which capture vastly different RNA populations [27].

Q4: If not TPM/FPKM, what should I use to compare gene expression across samples?

A4: For cross-sample comparisons and differential expression analysis, between-sample normalization methods applied to raw count data are strongly recommended [24] [1]. These methods are specifically designed to deal with library composition differences between samples. The most widely used and recommended methods include:

- Normalized Counts from tools like DESeq2 (which uses the RLE, or Relative Log Expression method) [24] [1] [28].

- Normalized Counts from tools like edgeR (which uses the TMM, or Trimmed Mean of M-values, method) [24] [1].

These methods have been shown to provide superior reproducibility, lower variation between biological replicates, and more accurate results in downstream analyses like differential expression and metabolic model building compared to TPM and FPKM [24] [1] [28].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

Problem: High variability between replicate samples after normalization with TPM.

Solution:

- Diagnosis: This is a known issue. A 2021 study on patient-derived xenograft models demonstrated that TPM and FPKM have higher median coefficients of variation (CV) and lower intraclass correlation (ICC) across replicates compared to normalized counts from DESeq2 or edgeR [24] [28].

- Action: Re-analyze your raw count data using a between-sample normalization method like those provided by DESeq2 (RLE) or edgeR (TMM). The same study found that hierarchical clustering of replicate samples was most accurate using these normalized counts [24].

Problem: Inconsistent results when integrating my TPM data with a public dataset.

Solution:

- Diagnosis: Differences in sample preparation protocols (e.g., poly(A)+ selection vs. rRNA depletion) drastically alter the RNA repertoire. TPM values from these different protocols are not directly comparable because the "per million" scaling factor is applied to different underlying populations [27].

- Action: If possible, obtain the raw sequencing data (FASTQ files) for both datasets and re-process them through the same bioinformatics pipeline (alignment and quantification) to generate normalized counts. If this is not feasible, be extremely cautious in your interpretation and acknowledge the technical bias as a major limitation.

Experimental Protocols & Data Analysis

Benchmarking Protocol: Comparing Normalization Methods

The following methodology is adapted from a 2021 study comparing quantification measures [24] [28].

1. Sample Preparation and Data Acquisition:

- Samples: Use replicate samples from the same biological source (e.g., 61 human tumor xenografts from 20 distinct models) [24].

- RNA-seq: Perform standard RNA-seq library preparation and sequencing. Download raw data (FASTQ files) and associated quantification files.

2. Data Processing and Quantification:

- Process all samples uniformly. The cited study mapped reads to a reference transcriptome using Bowtie2, generated BAM files, and performed gene-level quantification with RSEM to obtain TPM, FPKM, and expected counts [24].

- For cross-sample methods, generate normalized counts using DESeq2 (RLE) and edgeR (TMM) from the expected counts matrix [1].

3. Performance Evaluation Metrics:

- Coefficient of Variation (CV): Calculate the median CV for the same gene across all replicate samples. A lower CV indicates higher reproducibility [24].

- Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC): Calculate ICC across replicate samples from the same model. A higher ICC indicates better agreement between replicates [24].

- Cluster Analysis: Perform hierarchical clustering on the different normalized datasets. The method that most accurately groups replicate samples from the same model together is superior [24].

Table: Typical Results from a Benchmarking Study (based on [24])

| Quantification Measure | Median Coefficient of Variation (CV) | Intraclass Correlation (ICC) | Cluster Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normalized Counts (e.g., DESeq2) | Lowest | Highest | Most Accurate |

| TPM | Intermediate | Intermediate | Less Accurate |

| FPKM | Highest | Lowest | Least Accurate |

Workflow Diagram: From Raw Data to Normalized Quantities

The diagram below illustrates the key steps in calculating FPKM and TPM, highlighting the difference in the order of operations.

Table: Essential Computational Tools for RNA-seq Quantification

| Tool / Resource | Function | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| RSEM (RNA-Seq by Expectation-Maximization) | A software package for estimating gene and isoform abundances from RNA-Seq data. | Expected counts, TPM, FPKM [24] |

| Salmon / Kallisto | Ultra-fast, alignment-free tools for transcript-level quantification. Ideal for large datasets. | Estimated counts, TPM [27] |

| DESeq2 | A widely used R/Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis. | Normalized counts (using RLE normalization) [24] [1] |

| edgeR | Another widely used R/Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis. | Normalized counts (using TMM normalization) [24] [1] |

| NCI PDMR (Patient-Derived Model Repository) | A public resource providing annotated RNA-seq data from patient-derived models, useful for benchmarking. | FASTQ files, TPM, FPKM, and count data [24] |

Decision Pathway: Selecting a Normalization Method

Use the following decision diagram to guide your choice of normalization method based on your experimental goal.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing High Variability in Model Size or Differential Expression Results

Problem: When creating condition-specific metabolic models or performing differential expression analysis, the number of active reactions or identified genes shows high variability between samples.

Explanation: This is a common issue when using within-sample normalization methods like TPM or FPKM for between-sample comparative analyses. These methods do not adequately account for differences in RNA composition between samples. A few highly expressed genes in one sample can consume a large portion of the sequencing depth, distorting the expression proportions of all other genes [29] [30].

Solution: Switch to a between-sample normalization method.

- Recommended Action: Re-normalize your RNA-seq data using TMM, RLE, or GeTMM.

- Expected Outcome: These methods produce models and results with considerably lower variability in the number of active reactions across samples [29]. They are designed to be robust against RNA composition effects, which is particularly important for tissues with different transcriptional architectures [30].

- Verification: After re-normalization, check the distribution of your model sizes (e.g., number of active reactions) or the number of significant hits. The inter-sample variability should be substantially reduced.

Guide 2: Choosing a Normalization Method for Both Inter- and Intra-Sample Analysis

Problem: Your analysis requires comparing expression between samples (e.g., disease vs. control) AND comparing the expression levels of different genes within the same sample (e.g., for gene signature validation).

Explanation: Standard between-sample methods like TMM and RLE do not correct for gene length. Therefore, a longer gene will have more reads than a shorter gene even if their true expression levels are identical, making them unsuitable for within-sample gene comparisons [31]. Conversely, TPM corrects for gene length but is sensitive to highly expressed outliers for between-sample comparisons [29] [32].

Solution: Use the GeTMM (Gene length corrected Trimmed Mean of M-values) method.

- Recommended Action: Implement the GeTMM normalization procedure.

- Rationale: GeTMM combines the robust between-sample correction of TMM with gene length normalization. This allows the same normalized dataset to be used reliably for both inter-sample and intra-sample analyses [31].

- Expected Outcome: You will obtain a dataset that performs equivalently to TMM and RLE in differential expression analysis while also enabling valid within-sample gene-level comparisons, much like TPM [29] [31].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core assumption behind TMM and RLE normalization methods?

Both TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) and RLE (Relative Log Expression) operate on the fundamental assumption that the majority of genes in an experiment are not differentially expressed [29] [30] [33]. They use this assumption to robustly estimate scaling factors that correct for technical variations, such as differences in library size and RNA composition, between samples.

FAQ 2: How does RNA composition bias affect normalization, and how do TMM/RLE correct for it?

RNA composition bias occurs when one sample has a small subset of genes that are extremely highly expressed. These genes consume a large fraction of the sequencing reads, thereby proportionally reducing the read counts for all other genes in that sample. If not corrected, this can make most other genes appear under-expressed in that sample [30].

- TMM corrects for this by calculating a weighted trimmed mean of the log expression ratios (M-values) between the sample and a reference, excluding highly expressed genes and genes with high variance [30].

- RLE uses the median of the ratios of each gene's count to its geometric mean across all samples as the scaling factor, which is also robust to outliers [29] [31].

FAQ 3: My dataset has known covariates like age, gender, or batch effects. Should I adjust for these before or after normalization?

Evidence suggests that covariate adjustment applied to normalized data can improve the accuracy of downstream analysis. A benchmark study on Alzheimer's and lung cancer data showed an increase in the accuracy of capturing disease-associated genes when covariate adjustment was applied to data normalized with RLE, TMM, or GeTMM [29]. The typical workflow is to first normalize the raw count data using a method like TMM or RLE, and then adjust the normalized values for known technical or biological covariates using an appropriate linear model.

FAQ 4: Why might my results be difficult to replicate, even when using proper normalization?

While correct normalization is crucial, the number of biological replicates is a critical factor for replicability. Studies have shown that results from RNA-seq experiments with small cohort sizes (e.g., fewer than 5-6 replicates) can be difficult to replicate due to high biological heterogeneity and low statistical power [34] [35]. It is recommended to use at least 6-12 biological replicates per condition for robust and replicable detection of differentially expressed genes [34] [35].

Data Presentation: Method Comparison

Table 1: Key Characteristics and Applications of TMM, RLE, and GeTMM Normalization Methods

| Feature | TMM | RLE | GeTMM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Name | Trimmed Mean of M-values | Relative Log Expression | Gene length corrected TMM |

| Primary Package | edgeR [30] |

DESeq2 [29] |

Custom implementation [31] |

| Corrects Gene Length? | No | No | Yes |

| Robust to RNA Composition? | Yes [30] | Yes [29] | Yes [31] |

| Ideal Use Case | Differential expression between samples [29] | Differential expression between samples [29] | Both inter- and intra-sample analysis [31] |

| Reported Performance | Lower variability in model results; high accuracy (~0.80) for disease genes [29] | Similar to TMM in performance for DE analysis [29] [36] | Equivalent to TMM/RLE for DE; lower false positives; enables intra-sample use [29] [31] |

Table 2: Quantitative Benchmarking of Normalization Methods on Disease Datasets (using iMAT models) This table summarizes results from a benchmark study that generated personalized metabolic models for Alzheimer's Disease (AD) and Lung Adenocarcinoma (LUAD) [29].

| Metric | TPM / FPKM | TMM | RLE | GeTMM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variability in # of Active Reactions | High | Low | Low | Low |

| Number of Significantly Affected Reactions | Highest | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Accuracy for AD-Associated Genes | Lower | ~0.80 | ~0.80 | ~0.80 |

| Accuracy for LUAD-Associated Genes | Lower | ~0.67 | ~0.67 | ~0.67 |

| Impact of Covariate Adjustment | Increase in accuracy | Increase in accuracy | Increase in accuracy | Increase in accuracy |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing GeTMM Normalization

GeTMM reconciles within-sample and between-sample normalization by adding gene length correction to the TMM method [31]. Below is a detailed methodology.

1. Input Data Requirements

- A raw count matrix (genes x samples).

- A vector of gene lengths (e.g., the total exon length in base pairs for each gene).

2. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Step 1: Calculate Reads Per Kilobase (RPK). For each gene ( g ) in sample ( j ), compute RPK: ( \text{RPK}{gj} = \frac{\text{raw count}{gj}}{\text{gene length in kb}} ).

- Step 2: Apply TMM Normalization to the RPK matrix. Use the standard TMM algorithm from the

edgeRpackage on the RPK values to calculate a scaling factor for each sample [30] [31].- The TMM method selects a reference sample and then for each test sample, it computes ( M )-values (log fold changes) and ( A )-values (average log expression).

- It trims the extremes (default is 30% of ( M )-values and 5% of ( A )-values) and calculates a weighted average of the remaining ( M )-values to get the log scaling factor.

- Step 3: Generate normalized GeTMM values. Multiply the RPK values by the TMM scaling factors to obtain the final GeTMM values [31].

3. Key Considerations

- Software: While not a standard function in

edgeR, the process can be implemented by calculating RPK and then using thecalcNormFactorsfunction inedgeRon the RPK matrix. - Validation: The performance of GeTMM has been validated on real data (e.g., 263 colon cancer samples), showing it allows for both inter- and intra-sample analysis with the same dataset [31].

Mandatory Visualization

GeTMM Normalization Workflow

Normalization Method Selection Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Relevance to Normalization |

|---|---|---|

edgeR (R Package) |

A comprehensive package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. | Provides the implementation for the TMM normalization method [30]. |

DESeq2 (R Package) |

A popular package for analyzing RNA-seq data and determining differential expression. | Provides the implementation for the RLE normalization method [29]. |

| Gene Length Annotations | A data file (e.g., from GENCODE or Ensembl) containing the length of each gene's transcript. | Essential for GeTMM and TPM. Used to correct for transcript length bias [31]. |

| High-Quality RNA Samples | Total RNA with high integrity (RIN > 8) to minimize technical bias from degradation. | All normalization methods assume data is free from major technical artifacts. Poor RNA quality can skew results. |

| Adequate Biological Replicates | Multiple independent biological samples per condition (recommended n ≥ 6) [34]. | Critical for statistical power. No normalization method can compensate for a complete lack of replication. |

FAQ: Bulk RNA-Seq Data Normalization

What is the primary goal of normalization in bulk RNA-seq analysis?

Normalization is a critical step that removes non-biological technical variations to make gene counts comparable within and between samples. This process accounts for technical biases like sequencing depth (variation in the total number of reads generated per sample), library composition (differences in RNA population composition between samples), and gene length, allowing for meaningful biological comparisons [37] [11].

How does the choice of normalization method impact my downstream analysis?

The normalization method you select has a profound effect on all subsequent analyses. Benchmark studies demonstrate that method choice affects the ability to accurately capture biologically significant results. For instance, when mapping transcriptome data to genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), between-sample methods like RLE and TMM produced models with lower variability and more accurately identified disease-associated genes compared to within-sample methods like TPM and FPKM [1]. An inappropriate choice can increase false positive predictions or cause true biological signals to be missed.

When should I use within-sample versus between-sample normalization methods?

- Within-sample methods (e.g., TPM, FPKM) normalize counts based on features of individual samples. They are useful for comparing expression levels across different genes within the same sample because they account for gene length. However, they can introduce variability when comparing the same gene across different samples [1].

- Between-sample methods (e.g., TMM, RLE) normalize by considering the distribution of counts across all samples. They are generally preferred for identifying differentially expressed genes between conditions as they more effectively account for library size differences and composition biases [1] [37].

What are the key statistical assumptions made by different normalization methods?

Most normalization methods rely on core statistical assumptions about the data:

- TMM and RLE assume that the majority of genes are not differentially expressed across the samples being compared. They operate by estimating size factors to adjust library sizes [1].

- Methods relying on the negative binomial distribution (used in DESeq2 and edgeR) assume that RNA-seq count data exhibits overdispersion (variance greater than the mean), which is commonly observed in sequencing data [37].

- Global scaling methods like CPM assume that the total library size is the primary source of technical variation.

Comparative Analysis of Bulk RNA-Seq Normalization Methods

Table 1: Key characteristics, assumptions, and Bioconductor implementations of major bulk RNA-seq normalization methods.

| Method | Full Name | Core Mathematical Principle | Key Assumptions | Primary Use Case | Bioconductor Package |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMM | Trimmed Mean of M-values | Scales library sizes based on a weighted trimmed mean of log expression ratios (M-values) after excluding extreme genes [1]. | Most genes are not differentially expressed; the expression values of the remaining genes are similarly high across samples [1]. | Between-sample comparisons; differential expression analysis [1]. | edgeR |

| RLE (Median of Ratios) | Relative Log Expression | Calculates a size factor for each sample as the median of the ratios of its counts to the geometric mean across all samples [1] [37]. | Most genes are not differentially expressed [1]. | Between-sample comparisons; differential expression analysis (default in DESeq2) [1] [37]. | DESeq2 |

| TPM | Transcripts Per Million | Normalizes for both sequencing depth and gene length by first dividing counts by gene length (in kb) and then by the sum of these length-normalized counts per sample (in millions) [1]. | Appropriate for comparing relative expression of different genes within a single sample [1]. | Within-sample gene comparison; often used for visualizations and export. | Calculated from raw counts, often by packages like tximport/tximeta [38]. |

| FPKM | Fragments Per Kilobase Million | Similar to TPM but the order of operations differs—normalizes for sequencing depth first, then gene length. This makes it non-comparable across samples for a given gene [1]. | Appropriate for within-sample comparisons. Largely superseded by TPM for cross-sample comparability [1]. | Within-sample gene comparison (legacy use). | Calculated from raw counts. |

| GeTMM | Gene-length corrected TMM | Combines the gene-length correction of TPM/FPKM with the between-sample normalization of TMM, performing both steps simultaneously [1]. | Reconciles the need for both within-sample and between-sample comparisons [1]. | Studies requiring both cross-gene and cross-sample comparability. | - |

| DegNorm | Degradation Normalization | Uses core degradation groups to model and remove mRNA degradation bias, which is a common issue in clinical samples with varying RNA quality [39]. | mRNA degradation affects genes in a systematic way that can be estimated and corrected. | Data with suspected mRNA degradation bias (e.g., clinical samples with varying RNA integrity). | DegNorm |

Essential Experimental Protocols for Normalization

Protocol 1: Standard Differential Expression Analysis Workflow with DESeq2

This protocol outlines the standard workflow for normalization and differential expression analysis using the DESeq2 package, which employs the RLE (median of ratios) method [37] [38].

- Data Preparation: Load a gene-count matrix into R, where rows represent genes and columns represent samples. The count matrix should be generated from tools like

Salmon(viatximport/tximeta) orfeatureCounts[38]. - Create DESeqDataSet: Construct a DESeqDataSet object from the count matrix and a sample information (colData) data frame that describes the experimental conditions.

- Normalization and Modeling: Execute the core DESeq2 analysis with a single command:

dds <- DESeq(dds). This function performs the following steps internally [37]:- Estimation of size factors (RLE normalization) to control for sequencing depth.

- Estimation of dispersion for each gene.

- Fitting of a generalized linear model and execution of the Wald test or likelihood ratio test for differential expression.

- Extract Results: Use the

results()function to extract a table of differential expression results, including log2 fold changes, p-values, and adjusted p-values.

Protocol 2: Benchmarking Normalization Methods for Metabolic Modeling

This protocol is derived from a published benchmark study that evaluated normalization methods for building condition-specific metabolic models [1].

- Data Input: Obtain raw RNA-seq count data for the cohorts of interest (e.g., disease vs. control).

- Normalization and Covariate Adjustment: Apply the five normalization methods (RLE, TMM, GeTMM, TPM, FPKM) to the raw count data. Generate a second set of normalized data where covariates like age, gender, and post-mortem interval are statistically adjusted for.

- Model Reconstruction: Map each normalized dataset onto a generic human genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) using algorithms like iMAT or INIT to generate personalized, condition-specific metabolic models.

- Performance Evaluation: Compare the resulting models based on:

- Variability in the number of active reactions across samples.

- The number of significantly affected reactions and pathways.

- Accuracy in capturing known disease-associated genes, validated against external datasets like metabolome data.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Normalization method selection workflow.

Table 2: Key software tools and packages essential for bulk RNA-seq normalization and analysis.

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Normalization & Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | Bioconductor Package | Performs differential expression analysis using its built-in RLE (median of ratios) normalization. It models count data using a negative binomial distribution [37] [38]. |

| edgeR | Bioconductor Package | Performs differential expression analysis using the TMM normalization method. Also uses a negative binomial model to account for overdispersion in count data [1] [37]. |

| tximport / tximeta | Bioconductor Package | Facilitates the import of transcript-level abundance estimates from quantification tools (e.g., Salmon, kallisto) into R, and can be used to generate gene-level count matrices for input to DESeq2 or edgeR [38]. |

| Salmon | Quantification Tool | A fast and accurate alignment-free tool for quantifying transcript abundances. It can be run in alignment-based mode or pseudoalignment mode and provides output that can be summarized to the gene level [5] [38]. |

| STAR | Read Aligner | A splice-aware aligner used to map RNA-seq reads to a reference genome. Alignment files (BAM) can be used as input for quantification tools like Salmon or counted directly using featureCounts [5] [40]. |

| DegNorm | Bioconductor Package | A specialized package designed to correct for mRNA degradation bias in RNA-seq data, which is not addressed by standard normalization methods [39]. |

| FastQC | Quality Control Tool | Generates quality control metrics for raw sequencing reads, which is a critical first step before normalization and analysis to identify potential technical issues [40]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are spike-ins and why are they crucial for RNA-seq normalization?

Spike-ins are synthetic RNA molecules of known sequence and quantity that are added to an RNA sample before library preparation [41]. They serve as an external standard to control for technical variation. Unlike relying on the assumption that most endogenous genes are not differentially expressed, spike-ins provide a fixed baseline, allowing for a more direct measurement and removal of cell-specific or sample-specific technical biases, such as differences in capture efficiency and library generation [42]. This is particularly vital in experiments where global transcriptional changes are expected, as this violates the core assumption of many non-spike-in normalization methods [43].

My lab is new to using spike-ins. What are the primary options available?

The two most common sets of spike-in RNAs are the External RNA Controls Consortium (ERCC) set and the Spike-in RNA Variants (SIRV) set [42] [44]. The ERCC spike-ins are derived from synthetic DNA sequences or sequences from bacterial genomes and are designed to have minimal homology with eukaryotic transcripts [41]. The SIRV set is designed to comprehensively cover transcription and splicing events, allowing for quality control and validation on the transcript level [44]. Your choice may depend on your experimental needs, such as whether you require isoform-level resolution.

I've heard spike-in addition can be inconsistent. Does this invalidate the method?

This is a common concern, but experimental evidence suggests it is not a major practical issue. A 2017 study specifically designed mixture experiments to quantify the variance in the amount of spike-in RNA added to each well in a plate-based protocol. The research demonstrated that variance in spike-in addition is a quantitatively negligible contributor to the total technical variance and has only minor effects on downstream analyses like detection of highly variable genes [42]. The study concluded that spike-in normalization is reliable enough for routine use in single-cell RNA-seq, and this reliability extends to bulk RNA-seq applications.

What are some common hidden quality issues that can skew my analysis?

Beyond obvious problems like low read quality, "quality imbalances" between sample groups are a significant but often overlooked threat. A recent analysis of 40 clinically relevant RNA-seq datasets found that 35% exhibited significant quality imbalances [45]. These imbalances can inflate the number of differentially expressed genes, leading to false positives or negatives, because the analysis can become driven by data quality rather than true biological differences. It is crucial to proactively check for these imbalances using quality control tools, similar to how batch effects are managed [45].

When is spike-in normalization absolutely necessary?

Spike-in normalization is highly recommended in the following scenarios:

- Bulk RNA-seq experiments where the experimental condition is expected to cause large-scale changes in total RNA content or the overall transcriptome profile [43]. For example, in a study of sorghum under chilling stress, the use of spike-ins prevented misinterpretation of time-of-day-specific gene expression patterns [43].

- Single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) analyses, where technical cell-to-cell variation is profound and the assumption of a stable non-DE gene set is often untenable due to extreme biological heterogeneity [42] [11].

- Any situation where you need to control for variability in sample input, RNA degradation, or capture efficiency across your experiment.

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Even after normalization, my results don't match biological expectations.

Potential Cause: Hidden quality imbalances between your sample groups may be biasing the analysis.

Solution:

- Systematic QC Assessment: Use a comprehensive quality control pipeline like

RNA-QC-chainorFastQCto generate a wide array of metrics, including sequencing quality scores, adapter contamination, ribosomal RNA residue, and alignment statistics [46] [22]. - Check for Group-wise Imbalances: Aggregate QC metrics from all samples and use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or hierarchical clustering on these metrics to identify if samples cluster more by quality than by biological group. Tools like

MultiQCare excellent for consolidating this data [22]. - Employ Specialized Tools: Use machine learning-based tools like

seqQscorerthat are specifically designed to statistically characterize NGS quality features and automatically detect quality imbalances that might not be obvious from individual metrics [45]. - Account for Imbalances: If imbalances are detected, you must account for them in your differential expression model, similar to how you would correct for a batch effect.

Problem: My spike-in coverage is too low or inconsistent across samples.

Potential Cause: Improper handling or dilution of the spike-in reagent, or adding an inappropriate amount relative to the endogenous RNA.

Solution:

- Pre-mix Spike-in Reagents: To minimize well-to-well variability, create a large, master mix of your spike-in solution that can be added equally to all samples [42].

- Accurate Quantification: Precisely quantify your endogenous RNA sample to determine the appropriate amount of spike-in RNA to add. The goal is to have sufficient spike-in reads for a robust signal without wasting sequencing depth.

- Validate Spike-in Performance: Monitor the log-ratio of different spike-in sets if multiple are used, or check the correlation of spike-in counts against their known input concentrations to ensure they are behaving as expected [42] [41].

Problem: I am not sure which normalization method to use for my bulk RNA-seq data.

Potential Cause: The choice of normalization method depends on the data characteristics and the experimental question. Using a method that makes incorrect assumptions will lead to biased results.

Solution: Refer to the following table to select an appropriate method based on your experimental conditions. Note that spike-in normalization is often the most reliable when its core assumptions are met, as it does not rely on assumptions about the endogenous biology [42] [43].

| Normalization Method | Principle | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spike-in (e.g., ERCC, SIRV) | Scales counts based on coverage of known, externally added RNA transcripts [42] [41]. | Experiments with global transcriptional changes; when technical variation in RNA capture is a major concern [43]. | Requires precise addition; spike-ins must be processed in parallel with endogenous RNA [42]. |

| TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) | Assumes most genes are not differentially expressed. Calculates scaling factors after removing extreme fold-changes and expression levels [13]. | Standard bulk RNA-seq where the majority of genes are not expected to change between conditions [13]. | Can be biased if a large fraction of genes are differentially expressed [13]. |

| TPM (Transcripts Per Million) | Normalizes for both sequencing depth and gene length, making expression comparable within a sample [13]. | Comparing the relative abundance of different transcripts within a single sample. | Not sufficient for between-sample comparisons on its own; requires an additional between-sample method [13]. |

| Quantile | Makes the distribution of gene expression values the same across all samples [13]. | Making sample distributions comparable, often as a pre-processing step for cross-dataset analysis. | Assumes the overall expression distribution should be identical, which may not be biologically true. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| ERCC Spike-in Mix | A set of synthetic RNAs used as external controls for normalization, allowing for precise quantification and removal of technical variation [41]. | Added to sorghum RNA samples to accurately identify chilling stress-responsive genes that were misinterpreted by standard normalization [43]. |

| SIRV Spike-in Mix | A set of spike-in RNAs designed to mimic complex splicing events, used for quality control and validation of RNA-seq pipelines on the transcript level [44]. | Used in mixture experiments to quantify the variance in spike-in addition and validate the reliability of spike-in normalization [42]. |

| UMIs (Unique Molecular Identifiers) | Short random nucleotide sequences that tag individual mRNA molecules before PCR amplification, allowing for the accurate counting of original transcripts and correction of PCR duplicates [11]. | Integrated into full-length scRNA-seq protocols like Smart-Seq3 to improve transcript quantification accuracy [11]. |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Kits designed to remove ribosomal RNA from the total RNA sample, thereby enriching for mRNA and increasing the informative sequencing depth [22]. | Used in library preparation to remove >95% of rRNA, preventing it from dominating the sequencing library [22]. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating Spike-in Normalization with a Mixture Experiment

This protocol is adapted from a study that quantified the variance and reliability of spike-in normalization [42].

Objective: To empirically estimate the well-to-well variance in spike-in RNA addition and its impact on normalization accuracy.

Key Materials:

- Two distinct spike-in sets (e.g., ERCC and SIRV)

- 96-well microtiter plate

- Single-cell suspension (e.g., mouse 416B cells)

- Reagents for a plate-based scRNA-seq protocol (e.g., Smart-seq2)

Methodology:

- Separate Addition Experiment:

- Lysate a single cell into each well of a 96-well plate.

- Add an equal volume of the ERCC spike-in set separately to each well.

- Add an equal volume of the SIRV spike-in set separately to each well. The order of addition can be reversed for a subset of wells to test for effects.

- Process all wells to generate cDNA libraries and sequence.

Premixed Addition Experiment (Control):

- On the same plate, include wells where the two spike-in sets are first pooled at a 1:1 ratio to create a "premixed" spike-in solution.

- Add the same volume of this premixed solution to the cell lysate in these control wells.

- Process and sequence alongside the separate-addition wells.

Computational Analysis:

- For each library (well), map reads and compute the total count for each spike-in set.

- Calculate the log2-ratio of the totals (ERCC/SIRV) for each well.

- Calculate the variance of this log-ratio across all wells from the premixed-addition experiment. This establishes the baseline technical variance.

- Calculate the variance of the log-ratio across all wells from the separate-addition experiment.

- Estimate the variance of volume addition as the difference between the variance from the separate-addition and the premixed-addition experiments. A small value indicates that volume addition is not a major source of noise.

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Spike-in Normalization Workflow

Decision Guide for Normalization Methods

Advanced Troubleshooting: Overcoming Common Pitfalls and Optimizing Your Normalization Strategy