Optimizing Bulk RNA-Seq Sequencing Depth: A Strategic Guide for Robust Gene Expression Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing sequencing depth in bulk RNA-Seq experiments.

Optimizing Bulk RNA-Seq Sequencing Depth: A Strategic Guide for Robust Gene Expression Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing sequencing depth in bulk RNA-Seq experiments. It covers foundational principles, establishing that 5-15 million mapped reads is a minimum for differential gene expression, while deeper sequencing (20-50+ million reads) is required for isoform or fusion detection. The guide details methodological choices based on research goals, addresses common troubleshooting scenarios like degraded RNA or low input, and emphasizes the critical importance of biological replicates for statistical power and replicability. By synthesizing recent evidence and best practices, this resource enables the design of cost-effective and statistically powerful RNA-Seq studies that yield reliable, publication-quality results.

Sequencing Depth Fundamentals: Laying the Groundwork for Quality RNA-Seq

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between sequencing depth and coverage in RNA-seq?

While often used interchangeably, sequencing depth and coverage are distinct metrics. Sequencing depth (or read depth) refers to the total number of reads obtained from a sequencing run, typically specified in millions of reads per sample [1]. In contrast, coverage describes the uniformity of sequencing across the transcriptome. It can refer to the percentage of transcripts that have been sequenced or the redundancy of sequencing at specific genomic positions [2] [3]. High depth means more reads, which increases confidence in detecting expression, especially for lowly expressed genes. High coverage ensures a more complete and uniform representation of the entire transcriptome.

Q2: What is a good sequencing depth for my bulk RNA-seq experiment?

The optimal sequencing depth depends on your experiment's specific goals and the organism's complexity. The table below summarizes general recommendations.

| Experiment Goal | Recommended Mapped Reads | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Gene Expression (DGE) | 5 - 25 million [1] [4] | A good snapshot of highly expressed genes; a bare minimum of 5 million reads for human [1]. |

| Standard Global Gene Expression | 20 - 60 million [1] [4] | A more global view; common for published human studies; allows for some alternative splicing analysis [1] [5]. |

| Isoform-Level Analysis & Novel Transcript Discovery | 100 - 200 million [4] | In-depth view of the transcriptome; required for assembling new transcripts [4] [5]. |

| Targeted RNA-Seq | ~3 million [4] | Fewer reads are required as the analysis focuses on a specific, targeted panel of genes. |

Q3: Should I prioritize more biological replicates or higher sequencing depth?

For most differential gene expression studies, prioritizing more biological replicates is more beneficial than increasing sequencing depth [1] [5]. Biological replicates (different biological samples under the same condition) are essential for accurately estimating biological variation, which is typically much larger than technical variation [5] [6]. Research has shown that increasing replicates from 2 to 6 provides a greater increase in statistical power and detected genes than increasing sequencing depth from 10 million to 30 million reads per sample [1]. A good starting point is at least 3 biological replicates per condition, with 4-8 being ideal for robust results [7].

Q4: What are common data quality issues related to depth and coverage, and how can I troubleshoot them?

Common issues and their solutions are detailed in the table below.

| Problem | Potential Causes | Troubleshooting Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Low Library Yield [8] | Poor input RNA quality, contaminants, inaccurate quantification, inefficient fragmentation/ligation. | Re-purify input RNA; use fluorometric quantification (e.g., Qubit) over UV absorbance; optimize fragmentation parameters; titrate adapter ratios [8]. |

| High Duplicate Reads [8] [9] | Over-amplification during PCR, low library complexity, or very high expression of a few genes. | Reduce the number of PCR cycles; ensure sufficient starting material; use specialized analysis software to differentiate technical duplicates from biological duplicates in RNA-seq [8] [9]. |

| High rRNA Reads [9] | Inefficient ribosomal RNA depletion during library preparation. | Optimize the ribodepletion protocol. For poly-A selection-based methods, ensure RNA integrity (high RIN) as degradation can impair poly-A capture [9]. |

| Low Mapping Rate [9] | Sample contamination, poor read quality, or using an incorrect reference genome. | Check for contamination (e.g., from other species); perform rigorous quality control (QC) on raw reads; verify the reference genome and annotation match your sample species and strain [9]. |

| 3'/5' Bias [3] | RNA degradation or biases in library preparation protocols, especially with degraded RNA (e.g., FFPE). | Use high-quality RNA with a high RIN score; for degraded samples, consider using library kits specifically designed to handle low-quality input RNA [3] [7]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: A Systematic Workflow

This workflow outlines a logical path for diagnosing and resolving common NGS library preparation issues that impact data quality.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function in RNA-seq Workflow |

|---|---|

| Biological Replicates [5] [7] | Independent biological samples (e.g., from different individuals, animals, or cell culture passages) used to measure natural biological variation, which is critical for robust statistical analysis in differential expression. |

| Spike-in Controls (e.g., SIRVs) [7] | Synthetic RNA molecules added in known quantities to the sample. They serve as an internal standard to measure technical performance, including dynamic range, sensitivity, and quantification accuracy across samples and batches. |

| Ribodepletion Reagents [9] | Used to deplete abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA) from the total RNA sample, maximizing the number of informative sequencing reads from mRNA and other RNA types of interest. |

| Stranded Library Prep Kits [4] | Library preparation kits that preserve the strand orientation of the original RNA transcript. This is essential for accurately determining which DNA strand produced the RNA, crucial for identifying overlapping genes and antisense transcription. |

| Poly-A Selection Beads [9] | Used to isolate messenger RNA (mRNA) by capturing the poly-adenylated tail. This enriches for mature mRNA and is a common method to remove rRNA. |

| Fluorometric Quantitation Kits (e.g., Qubit) [8] | Provide accurate quantification of nucleic acid concentration by specifically binding to DNA or RNA. They are more reliable than UV absorbance (NanoDrop) which can be skewed by contaminants. |

What is sequencing depth and why is it critical for bulk RNA-seq?

In bulk RNA sequencing, sequencing depth describes the total number of reads obtained from a sequencing run, typically specified on a per-sample basis as "millions of reads" [1]. A related term, coverage, usually refers to the redundancy with which the bases of a transcript are sequenced, which is influenced by both read length and transcript length [1].

Achieving the correct depth is a fundamental trade-off between information content and cost. A higher number of reads increases the statistical power to detect differential expression, especially for genes with low expression levels, but also increases sequencing costs [1]. The optimal depth balances the need for statistical power with financial constraints and the specific goals of your experiment [1].

What are the minimum and recommended sequencing depths?

The following table summarizes the general guidelines for sequencing depth in standard differential gene expression (DGE) analysis, particularly for human samples.

| Analysis Goal | Recommended Mapped Reads (Millions) | Key Considerations & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Standard DGE (Minimum) | 5 - 15 M [1] | Provides a good snapshot of highly expressed genes. A good bare minimum is 5 M mapped reads [1]. |

| Standard DGE (Optimal) | 20 - 50 M [1] | Provides a more global view of gene expression and increases power to detect differential expression for lowly expressed genes [1]. Many published human RNA-Seq experiments use this range [1]. |

| Robust Gene Quantification | 25 - 40 M [10] | A cited sweet spot for robust gene quantification with high-quality RNA, often using paired-end reads [10]. |

It is crucial to note that these are general guidelines. The ideal depth for your experiment depends heavily on its specific objectives.

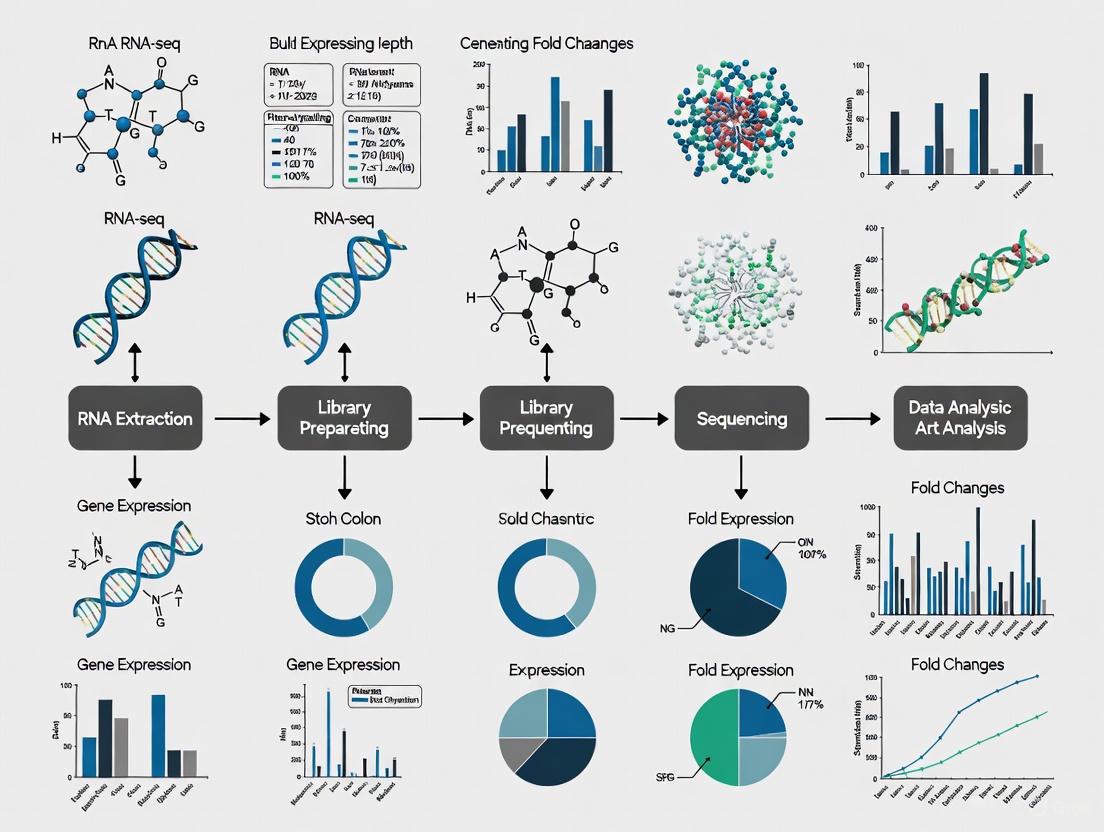

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for determining sequencing depth based on experimental goals.

How do research goals and sample quality influence depth requirements?

Your specific biological question is the primary driver for determining the necessary sequencing depth. Deeper sequencing is required to answer questions beyond standard gene-level differential expression [10].

| Research Goal | Recommended Depth & Configuration | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Isoform Detection & Alternative Splicing | ≥ 100 M paired-end reads [10] | Comprehensive isoform coverage requires sufficient reads to span and quantify low-abundance splice junctions across many transcripts [10]. |

| Fusion Gene Detection | 60 - 100 M paired-end reads [10] | Most fusion callers need paired-end libraries to anchor breakpoints. Higher depth ensures sufficient "split-read" support for reliable detection [10]. |

| Allele-Specific Expression (ASE) | ~100 M paired-end reads [10] | Essential to minimize sampling error and accurately estimate variant allele frequencies, especially with low tumor purity or compromised RNA [10]. |

Sample Quality is a Key Factor: The integrity of your RNA sample significantly impacts the effective complexity of your library. Degraded RNA inflates duplication rates and reduces the amount of useful data.

- High-Quality RNA (RIN ≥ 8, DV200 > 70%): Standard sequencing depths are sufficient [10].

- Degraded RNA (e.g., FFPE samples with DV200 30-50%): It is recommended to add 25-50% more reads to compensate for reduced complexity [10]. For severely degraded samples (DV200 < 30%), avoid poly(A) selection and use rRNA depletion or capture-based protocols with ≥ 75-100 million reads [10].

What is the trade-off between sequencing depth and biological replicates?

One of the most critical concepts in experimental design is the balance between sequencing depth and the number of biological replicates. A landmark study demonstrated that increasing the number of biological replicates provides greater statistical power for detecting differential expression than increasing the sequencing depth per sample [1].

For a fixed budget, investing in more replicates is often more beneficial. For instance, raising the number of biological replicates from 2 to 6 at a fixed depth of 10 million reads per sample resulted in a higher increase in gene detection and statistical power than increasing the reads per sample from 10 million to 30 million with only 2 replicates [1].

Sample Size Guidelines: A recent large-scale study in mice provides empirical evidence for replicate numbers. The study found that results from experiments with 4 or fewer replicates were highly misleading due to high false positive rates and poor discovery of true effects [11]. The guidelines suggest:

- Minimum: 6-7 mice per group to reduce the false positive rate below 50% and increase sensitivity above 50% for a 2-fold expression difference [11].

- Significantly Better: 8-12 replicates per group to more reliably recapitulate the results of a much larger experiment [11].

Diagram 2: The trade-off between sequencing depth and biological replicates for differential gene expression analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

The following table lists essential materials and reagents used in a typical bulk RNA-seq workflow, along with their primary functions.

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Poly(A) Selection | Enriches for messenger RNA (mRNA) by capturing the poly-A tail, filtering out ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and other non-coding RNAs. Ideal for high-quality RNA when focusing only on protein-coding genes [10] [12]. |

| rRNA Depletion | Removes ribosomal RNA sequences from total RNA, preserving both coding and non-coding polyA- transcripts. Recommended for degraded samples (e.g., FFPE) or when studying non-polyadenylated RNAs [10]. |

| Stranded Library Prep Kit | Preserves the strand orientation of the original RNA transcript during cDNA library preparation. This prevents ambiguity in determining which DNA strand was transcribed, crucial for accurate annotation and detecting antisense transcription [12]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences added to each molecule before PCR amplification. UMIs allow for accurate counting of original RNA molecules and correction for PCR duplication biases, which is particularly important when sequencing degraded samples or at very high depths [10]. |

| TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit | A common commercial solution for constructing sequencing-ready RNA-seq libraries, involving steps like cDNA synthesis, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification [13]. |

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

This protocol outlines the key steps for planning and executing a bulk RNA-seq experiment optimized for Differential Gene Expression (DGE) analysis.

Step 1: Define Goals and Design the Experiment

- Clearly state your primary biological question (e.g., DGE, isoform detection).

- Based on your goal, use Diagram 1 to determine the required sequencing depth.

- Crucially, decide on the number of biological replicates. Prioritize more replicates over extreme depth. Refer to established guidelines, aiming for a minimum of 6-8 replicates per condition for robust DGE [11].

- Plan for a stranded library preparation to preserve strand information [12].

Step 2: Assess Sample Quality and Choose Library Protocol

- Quantify RNA integrity using methods like Agilent Bioanalyzer to obtain RIN (RNA Integrity Number) or similar metrics like RQS and DV200 [10] [13].

- For high-quality RNA (RIN ≥ 8, DV200 > 70%): Proceed with standard poly(A) selection for mRNA enrichment [10].

- For partially degraded RNA (e.g., FFPE with DV200 30-50%): Use rRNA depletion instead of poly(A) selection and plan for a 25-50% increase in sequencing depth [10].

- If working with limited RNA input or highly degraded material, select a library prep kit that incorporates UMIs to control for PCR duplicates [10].

Step 3: Sequencing Configuration

- Read Type: Use paired-end sequencing (e.g., 2x75 bp or 2x100 bp). This provides better mapping accuracy and is essential for any analyses beyond basic DGE, such as splice junction detection [10] [12].

- Depth: Based on Steps 1 and 2, select your per-sample sequencing depth from the ranges in the tables above (e.g., 20-50 M for standard DGE).

- Multiplex your samples using unique barcodes to sequence multiple libraries together on one lane, thereby controlling for lane-specific technical effects [6].

Step 4: Data Analysis and Quality Control

- After sequencing, perform standard QC on the raw read data using tools like FastQC.

- Align reads to the reference genome using a splice-aware aligner (e.g., TopHat, STAR) [6] [13].

- Quantify reads associated with genes or transcripts using tools like Cufflinks or featureCounts [6] [13].

- For DGE analysis, use statistical methods designed for count data, such as those implemented in DESeq2, edgeR, or limma-voom [14].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Sequencing Depth

1. How does genome size influence the number of reads I need for my bulk RNA-seq experiment? The required sequencing depth is directly proportional to the complexity of the genome being studied. Larger genomes with more genes require deeper sequencing to adequately capture and quantify the expression of all transcripts, including those that are lowly abundant [15]. The table below provides general recommendations.

2. What is "transcriptome diversity" and why does it matter for depth? Transcriptome diversity refers to the variety and abundance of different RNA molecules (mRNAs, isoforms, etc.) in a sample. Techniques like RACE-Nano-Seq reveal that complex splicing, multiple transcription start/termination sites, and low-abundance transcripts contribute significantly to this diversity [16]. A sample with high transcriptome diversity, such as a human tissue sample with extensive alternative splicing, contains a wider array of unique RNA sequences. To confidently detect and quantify these diverse, often rare transcripts, a greater sequencing depth is essential to ensure sufficient reads are allocated to each unique molecule [16] [15].

3. My organism has a small genome but high transcriptome complexity. How do I prioritize depth? In such cases, transcriptome diversity often becomes the primary driver for sequencing depth. While a small genome reduces the baseline number of reads needed, high complexity—such as that caused by pervasive alternative splicing—demands greater depth to resolve and quantify the full repertoire of transcript isoforms [16] [17]. It is crucial to base your depth on the specific biological question; investigating alternative splicing requires significantly more depth than a simple differential gene expression analysis between two conditions.

4. Can normalization methods compensate for insufficient sequencing depth? No, normalization methods cannot create information that was not captured during sequencing. While advanced normalization algorithms like ReDeconv can correct for technical biases such as variations in transcriptome size across cell types, they cannot reliably detect transcripts that are absent from the data due to shallow sequencing [18]. Adequate depth is a prerequisite for accurate normalization and downstream analysis.

Recommended Sequencing Depth Guidelines

Table 1: General guidelines for bulk RNA-seq sequencing depth, based on genome size and research goals. These are starting points; specific questions may require adjustments.

| Organism Category | Genome Size (Approximate) | Recommended Reads per Sample | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small Genomes (e.g., Bacteria) | ~1-5 Mb | 5-10 million | Focused gene content, lower inherent diversity [15]. |

| Medium Genomes (e.g., Fungi, Nematodes) | ~10-150 Mb | 15-20 million | Varies with pathogenic traits and transcriptome complexity [17]. |

| Large Genomes (e.g., Human, Mouse, Plants) | ~3 Gb | 20-30 million | Essential for capturing diverse splicing and low-abundance genes [15]. |

| De Novo Transcriptome Assembly | Any | 100 million per sample | Extreme depth required to reconstruct transcripts without a reference genome [15]. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent or Biased Differential Expression Results

Symptoms: Your DE analysis yields a high number of false positives, fails to validate with orthogonal methods, or shows high variance between biological replicates.

Root Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Improper Normalization. Standard Counts Per Million (CPM) or Counts Per 10 Thousand (CP10K) normalization assumes constant transcriptome size across samples. This is often false; different cell types have intrinsically different total mRNA content, which skews expression comparisons [18].

- Solution: Implement a normalization method that accounts for transcriptome size variation. The ReDeconv algorithm's CLTS (Count based on Linearized Transcriptome Size) method is specifically designed for this purpose and can correct for these scaling effects [18].

- Cause 2: Gene Length Effect. Bulk RNA-seq read counts are influenced by gene length, while UMI-based single-cell data are not. Using mismatched normalization (e.g., TPM for bulk and CP10K for scRNA-seq reference) creates a technical artifact that biases deconvolution and cross-platform comparisons [18].

- Solution: Apply TPM or FPKM normalization selectively to bulk RNA-seq data to mitigate gene length effects when performing integrative analyses [18].

- Cause 3: Low Sequencing Depth. Insufficient reads lead to poor quantification of lowly expressed genes, reducing the statistical power of your DE analysis.

Problem: Poor Read Alignment or Mapping Rates

Symptoms: Your alignment software (e.g., STAR, HISAT2) reports a low percentage of uniquely mapped reads, failing the run, or producing error messages.

Root Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Incompatible Reference Files. The chromosome identifiers in your annotation file (GTF) do not match those in your reference genome FASTA file (e.g., "1" vs. "chr1") [21].

- Solution: Ensure all reference files (genome and annotation) are sourced from the same database (e.g., both from UCSC or both from Ensembl). Download a matched set of files and regenerate your genome index [21].

- Cause 2: Truncated or Poor-Quality FASTQ Files. The sequencing run may have failed, or files may have been corrupted during transfer [21].

- Cause 3: Incorrectly Formatted GTF File. The annotation file may contain headers or lack essential feature lines (e.g., "exon" lines) that the aligner requires [21].

- Solution: Remove header lines from the GTF file or use a tool like gffread to convert a GFF file into a proper GTF format. Verify the file contains valid "exon" lines in the third column [21].

Workflow Diagram: Sequencing Depth Decision Guide

Experimental Protocols for Robust Results

Detailed Protocol: Bulk RNA-seq Analysis from FASTQ to Counts

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for processing bulk RNA-seq data, emphasizing steps critical for managing data from organisms with varying genome sizes and transcriptome diversity [19] [20].

1. Software Installation (Using Conda) Begin by installing the necessary bioinformatics tools in a Linux environment using the Conda package manager.

2. Quality Control (QC) with FastQC Run FastQC on your raw FASTQ files to assess base quality, adapter content, and sequence length distribution.

- Interpretation: Check the "Per base sequence quality" and "Adapter Content" plots. This initial QC will inform the trimming parameters in the next step [20].

3. Trimming and Filtering with Trimmomatic Remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases to improve mapping rates.

- Key Parameters:

LEADING:3andTRAILING:3remove low-quality bases from the start and end of reads.MINLEN:36discards reads that become too short after trimming [20].

4. Read Alignment with HISAT2 (or STAR) Align the trimmed reads to a reference genome. HISAT2 is a memory-efficient aligner, while STAR is highly accurate for splice-aware alignment. * First, build a genome index (once per reference):

* Then, perform alignment: * Critical Note: The choice of aligner can impact results, especially for non-human data. Studies have shown that performance varies by species, so it is beneficial to select tools based on your data [17].5. Post-Alignment Processing with Samtools Convert the SAM file to a sorted BAM file, which is required for gene counting.

6. Gene Counting with featureCounts Generate the count matrix by counting reads that overlap genomic features (e.g., exons of genes).

- Key Parameters:

-t exonspecifies the feature type to count, and-g gene_idspecifies the attribute to group features into meta-features (i.e., genes) [19] [20]. The resultingsample.counts.txtfile is used for differential expression analysis with tools like DESeq2 or limma.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key reagents and materials used in bulk RNA-seq library preparation and their functions.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Total RNA | The starting material for library prep. | Assess quality (RIN > 8) and quantity using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit), not just absorbance [8]. |

| rRNA Depletion Kit | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA) to enrich for mRNA and other RNAs. | Essential for prokaryotes, FFPE samples, or when studying non-polyadenylated RNAs like many lncRNAs [15]. |

| Poly(A) Selection Beads | Enriches for polyadenylated mRNA by binding to poly-A tails. | Standard for eukaryotic mRNA studies. May miss non-polyA transcripts and can introduce 3' bias [15]. |

| ERCC Spike-In Mix | A set of synthetic RNA controls of known concentration added to the sample. | Used to monitor technical variation, assay sensitivity, and to normalize for sample-specific biases [15]. |

| UMI Adapters | Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) are short random sequences that tag individual mRNA molecules before PCR. | Corrects for PCR amplification bias and duplicates, improving quantification accuracy, especially in low-input protocols [15]. |

| DNase/RNase-free Water | A solvent and diluent free of contaminating nucleases. | Critical for preventing degradation of RNA and cDNA throughout the protocol [16]. |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Trade-offs

Q1: What is the single most important factor for statistical power in a budget-conscious bulk RNA-seq experiment?

The number of biological replicates (samples) has the greatest influence on statistical power, more so than sequencing depth. Increasing biological replicates directly improves the ability to detect true differential expression by providing better estimates of biological variability. For a fixed budget, prioritizing more replicates over deeper sequencing is generally the most cost-effective strategy for power [22] [1].

Q2: How do I balance the number of replicates with sequencing depth when my budget is fixed?

This requires a trade-off analysis. A key study found that based on a sequencing depth of 10 million reads per sample, increasing the number of biological replicates from 2 to 6 resulted in a higher gain in statistical power and gene detection than increasing the sequencing depth from 10 million to 30 million reads per sample [1]. The table below summarizes general guidelines for this balance.

Table: Balancing Budget, Replicates, and Sequencing Depth

| Budget Priority | Recommended Replicates (per condition) | Recommended Sequencing Depth | Primary Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost-Saving | 5-7 (minimum) [11] | 20-25 million mapped reads [10] | Minimizes false positives for strong effects [11] |

| Standard Power | 8-12 [11] | 25-40 million paired-end reads [10] | Robust sensitivity for most DEG studies; good false positive control [11] |

| High Power / Complex Analysis | >12 | 40-100+ million reads [10] | Enables detection of low-fold-change DEGs, isoform usage, and splicing events [10] |

Q3: Can pooling RNA samples from multiple individuals be a cost-effective strategy?

Yes, RNA sample pooling can be a powerful cost-optimization strategy, especially when biological variability is high or individual sample input is limited. By mixing RNA from multiple biological samples (e.g., 2-5) into a single sequencing library, you reduce the number of libraries needed. Studies show that with an optimally defined pool size and sequencing depth, this strategy can maintain statistical power while substantially reducing total experiment costs [23].

Q4: What is a sufficient sequencing depth for a standard differential gene expression (DGE) study in human samples?

For a standard DGE analysis in human samples with high-quality RNA, 20-40 million mapped reads per sample is typically sufficient [1] [10]. A good bare minimum is 5 million mapped reads, but this will primarily capture highly expressed genes. Depths of 20-50 million reads provide a more global view of gene expression [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inadequate Power in Pilot Study

Symptoms:

- High false discovery rate (FDR) in differential expression analysis.

- Inability to detect genes known to be differentially expressed.

- Inflated effect sizes for reported significant genes (winner's curse) [11].

Diagnostic Steps:

- Conduct a retrospective power analysis: Use tools like

scPower(for single-cell) or bulk RNA-seq power calculators mentioned in reviews [22] to determine the power achieved in your pilot data. - Check replicate number: Compare your current sample size (N) to empirical guidelines. Results from experiments with N=4 or less are highly misleading, and an N of 6-7 is required to consistently decrease the false positive rate below 50% for 2-fold expression differences [11].

- Evaluate effect size distribution: Examine if the fold changes of your detected DEGs are unrealistically high, which can indicate underpowering [11].

Solutions:

- Prioritize increasing replicates: For a follow-up study, re-allocate budget from depth to replicates. The most significant power gain comes from moving from low N (e.g., 3-4) to N=8-12 [11].

- Consider sample pooling: If increasing the number of individual libraries is prohibitive, implement an RNA sample pooling strategy with an optimal pool size to effectively increase the biological N without a linear cost increase [23].

Problem: Suboptimal Data Quality Wasting Sequencing Budget

Symptoms:

- Low library yield or complex electropherograms with adapter dimer peaks [8].

- High duplication rates in sequencing data.

- Low mapping rates or uneven coverage.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Verify RNA Quality: Check RNA Integrity Number (RIN) or RQS and DV200 metrics. Degraded RNA (DV200 < 50%) requires specific protocols and deeper sequencing [10].

- Inspect Library Prep QC: Analyze BioAnalyzer or TapeStation traces for a sharp peak of adapter dimers (~70-90 bp) or a wide, multi-peaked fragment distribution, indicating ligation or purification failures [8].

- Cross-validate quantification: Compare fluorometric (Qubit) and qPCR results to UV absorbance (NanoDrop), which can overestimate usable material [8].

Solutions:

- For degraded/low-input RNA: Switch from poly(A) enrichment to rRNA depletion or capture-based protocols. Increase sequencing depth by 25-50% to compensate for reduced complexity and incorporate UMIs to correctly identify PCR duplicates [10].

- For library prep failures: Titrate adapter-to-insert molar ratios to reduce adapter dimers. Optimize bead-based cleanup ratios and avoid over-drying beads to prevent sample loss [8]. Use master mixes to reduce pipetting errors.

Experimental Design Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points for designing a cost-effective bulk RNA-seq experiment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents and Kits for Bulk RNA-Seq

| Item | Function | Consideration for Cost/Power Balance |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kit | Isolates high-quality total RNA from samples. | Critical for obtaining high RIN scores. Poor quality input wastes all subsequent costs. |

| Poly(A) Selection Beads | Enriches for messenger RNA (mRNA) by targeting poly-A tails. | Standard for high-quality RNA; lower cost than depletion but unsuitable for degraded RNA [10]. |

| rRNA Depletion Kit | Removes ribosomal RNA (rRNA) to enrich for other RNA species. | Essential for degraded samples (e.g., FFPE) or bacterial RNA; typically more expensive than poly(A) selection [10]. |

| Library Preparation Kit | Converts RNA into a sequence-ready DNA library. | A major cost driver. Consider kits with lower input requirements and built-in UMIs to improve data quality from scarce samples [10]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random barcodes that label individual mRNA molecules. | Adds cost but is highly recommended for low-input or degraded samples. UMIs allow accurate deduplication, making deeper sequencing more effective [10]. |

| Size Selection Beads | Purifies and selects cDNA fragments of a desired size range. | Optimizing bead ratios is crucial to maximize library yield and avoid losing fragments, preventing the need for costly repetition [8]. |

Tailoring Depth to Your Research Objective: From DGE to Isoform Discovery

Sequencing depth, or the number of reads per sample, is a critical parameter in bulk RNA-Seq experimental design. For standard gene-level differential expression analysis, recent community benchmarks and manufacturer guidelines have converged on 25–40 million paired-end reads as a cost-effective sweet spot for human samples with high-quality RNA [10]. This depth stabilizes fold-change estimates across expression quantiles without wasting resources on already-well-sampled transcripts [10]. This guide provides troubleshooting and FAQs to help researchers optimize their sequencing depth for robust DGE analysis.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Sequencing Depth

Q1: Why is 25-40 million reads considered a sweet spot for standard DGE? This range provides an optimal balance between cost and data quality for identifying differentially expressed genes. It ensures sufficient coverage to robustly quantify the majority of expressed genes, including those at medium to low abundance, while minimizing the expenditure on sequencing resources. Deeper sequencing yields diminishing returns for standard gene-level DGE when RNA quality is high (RIN ≥ 8, DV200 > 70%) [10].

Q2: When should I consider sequencing deeper than 40 million reads? You should consider higher sequencing depths for more complex biological questions. The table below summarizes recommendations for various applications beyond standard gene-level DGE.

Table 1: Recommended Sequencing Depth for Different Research Goals

| Research Goal | Recommended Depth (Mapped Reads) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Gene-Level DGE | 25 - 40 million [10] [24] | Sufficient for robust gene quantification with high-quality RNA. |

| Isoform Detection & Splicing | ≥ 100 million [10] | Requires longer reads (e.g., 2x100 bp) for comprehensive isoform coverage. |

| Fusion Gene Detection | 60 - 100 million [10] | Paired-end reads are essential to anchor breakpoints. |

| Allele-Specific Expression (ASE) | ≥ 100 million [10] | Essential to accurately estimate variant allele frequencies. |

Q3: How does RNA quality influence my required sequencing depth? RNA Integrity Number (RIN) or RQS and DV200 are critical metrics. Degraded RNA inflates duplication rates and reduces library complexity, requiring deeper sequencing to compensate for the loss of informative reads [10].

Table 2: Adjusting Protocol and Depth Based on RNA Integrity

| DV200 Metric | Recommended Protocol | Recommended Read Depth Adjustment |

|---|---|---|

| > 50% | Poly(A) or rRNA depletion; 2x75-2x100 bp reads | Standard depth (25-40 million) [10] |

| 30 - 50% | Prefer rRNA depletion or capture-based methods | Add 25 - 50% more reads [10] |

| < 30% | Avoid poly(A) selection; use capture or rRNA depletion | ≥ 75 - 100 million reads [10] |

Q4: Should I use single-end or paired-end sequencing for DGE? For DGE analysis, paired-end sequencing is strongly recommended over single-end. While single-end reads are less expensive, paired-end reads provide more robust alignment, especially across splice junctions, and effectively double the likelihood of detecting these junctions, leading to more accurate gene quantification [25] [24]. Most established bioinformatics pipelines for fusion detection or isoform analysis also depend on paired-end libraries [10].

Q5: How do I calculate the total number of samples I can multiplex on a single flow cell? This is a practical calculation. First, determine the total data output of your sequencing instrument and flow cell type (e.g., NextSeq 500 High-Output kit yields ~50-60 Giga bases [26]). Then, use the following formula: Number of Samples = Total Data Output (Gb) / (Reads per Sample × Read Length (bp) × 2 [for paired-end]) For example, targeting 30 million (0.03 billion) 2x75 bp reads per sample on a 55 Gb flow cell: 55 / (0.03 × 150) ≈ 12 samples. Always make conservative estimates to account for output variation [24].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

Problem: Low Mapping Rate After Sequencing A mapping rate below 70% is a strong indication of poor quality or other issues [27].

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Incorrect Reference Genome: Ensure you are using the correct genome build and annotation file for your species.

- Sample Contamination: Check for DNA, adapter, or other contaminant contamination. Re-purify input samples if necessary [8].

- Poor Sequence Quality: Review the FastQC report for low-quality bases and perform appropriate trimming [28].

- Failure to Trim Adapters/UMIs: Residual adapter or UMI sequences can prevent reads from mapping. Ensure these are properly trimmed or extracted before alignment. Failing to remove UMIs can significantly reduce alignment rates [26].

Problem: High Duplication Rates A high duplication rate suggests low library complexity, meaning many reads are PCR duplicates rather than originating from unique RNA molecules.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Over-amplification during PCR: Use the minimal number of PCR cycles necessary during library prep. Overcycling introduces duplicates and biases [8].

- Insufficient Starting RNA: Low input amounts (≤ 10 ng) lead to low complexity libraries. If input is limited, incorporate Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) to bioinformatically collapse true PCR duplicates [10].

- RNA Degradation: Degraded RNA reduces library complexity. Sequence deeper to offset this, and use rRNA depletion instead of poly(A) selection for degraded samples (e.g., FFPE) [10].

Problem: High rRNA Content in Data This indicates inefficient removal of ribosomal RNA during library preparation, which wastes sequencing capacity on non-informative reads.

- Solution: Optimize your rRNA depletion protocol. For total RNA-seq, ensure depletion kits are used correctly and are appropriate for your species. For mRNA-seq, ensure the poly(A) enrichment step is efficient [27].

Problem: Batch Effects in Large Studies Systematic, non-biological variations can arise from samples being processed on different days, by different operators, or sequenced on different lanes [27] [7].

- Solution: A robust experimental design is key. Randomize samples across processing batches whenever possible. Include technical controls and, if available, spike-in RNAs (e.g., SIRVs) to monitor technical performance [7]. Batch effects can often be detected using PCA plots and corrected for in silico during statistical analysis [27].

Experimental Protocol: A Recommended DGE Workflow

The following diagram outlines a standard workflow for a DGE study, from library preparation to differential expression analysis, highlighting key decision points.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Define Hypothesis and Objectives: Always start with a clear biological question. This will guide all subsequent decisions, from model system to sequencing depth [7].

- Sample Preparation and RNA QC: Extract high-quality RNA. Assess concentration and integrity using methods like Bioanalyzer to generate RIN or RQS and DV200 values. A RIN of ≥7 is often required for mRNA-seq library construction [24].

- Library Preparation: For standard DGE, use poly(A) enrichment for mRNA sequencing. For degraded samples or to include non-coding RNA, use rRNA depletion [24]. If input is limited (≤ 10 ng), consider using UMIs to correct for PCR duplication bias [10].

- Sequencing Design:

- Depth: Select 25-40 million mapped paired-end reads per sample for standard DGE with high-quality RNA [10].

- Length: Use paired-end 75 bp or 100 bp reads [10] [25].

- Replicates: Include a minimum of 3 biological replicates per condition to ensure statistical power, with 4-8 being ideal where possible [28] [7].

- Primary Data Analysis:

- Demultiplexing: Convert BCL files to FASTQ and assign reads to samples based on their index (barcode) sequences [26].

- Quality Control: Use FastQC or MultiQC to assess raw read quality [27] [28].

- Trimming: Remove adapter sequences, poly(A) tails, and low-quality bases using tools like Trimmomatic or Cutadapt [28] [26]. If UMIs were used, extract them and add to the read header before alignment [26].

- Secondary Data Analysis:

- Tertiary Data Analysis (DGE): Perform differential expression analysis in R using established packages like DESeq2, edgeR, or limma-voom [25] [29]. Always perform quality checks like PCA to identify potential batch effects or outliers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for Bulk RNA-Seq Experiments

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Total RNA | Starting material. Must be DNA-free and of high integrity (RIN > 7-8) for optimal results [24]. |

| Poly(A) Selection Beads | Used in library prep to enrich for polyadenylated mRNA, filtering out rRNA and other non-coding RNA. |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Alternative to poly(A) selection; removes ribosomal RNA, preserving both coding and non-coding RNA. Ideal for degraded samples (e.g., FFPE) [10] [24]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences added to each molecule before amplification. Allow bioinformatic collapse of PCR duplicates, critical for low-input or single-cell studies [10] [26]. |

| Spike-in RNA Controls | Synthetic RNAs of known concentration added to samples. Serve as an internal standard for normalization and quality assessment across samples and runs [7]. |

| Stranded Library Prep Kit | Produces libraries that retain information about the original strand of the transcript, which is valuable for accurate annotation [30]. |

| FastQC / MultiQC | Software tools for initial quality control of raw sequencing data, identifying issues like adapter contamination or low-quality bases [27] [28]. |

| STAR Aligner | A widely used, splice-aware aligner for mapping RNA-seq reads to a reference genome [25] [28]. |

| Salmon | A tool for transcript quantification that uses "pseudo-alignment," offering high speed and accuracy [25]. |

| DESeq2 / edgeR | R/Bioconductor packages for statistical analysis of differential gene expression from count data [29] [28]. |

In bulk RNA-Seq, standard sequencing depths of 20-40 million reads are sufficient for basic gene-level differential expression. However, sophisticated biological questions require a deeper, more powerful approach. This guide details the experimental and bioinformatic considerations for deploying high-depth sequencing (100 million reads and beyond) to tackle the challenges of isoform detection, fusion gene diagnosis, and allele-specific expression.

FAQ: Sequencing Depth and Experimental Goals

Q1: What are the recommended sequencing depths for advanced RNA-Seq applications? The required sequencing depth is dictated by your specific biological question. The table below summarizes the recommended parameters for different advanced applications.

Table 1: Recommended Sequencing Specifications for Advanced Applications

| Application | Recommended Depth | Read Length | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isoform Detection & Alternative Splicing | ≥ 100 million paired-end reads [10] | 2x75 bp or 2x100 bp [10] | Conventional differential expression depths capture only a fraction of splice events [10]. |

| Fusion Gene Detection | 60 - 100 million paired-end reads [10] | 2x75 bp (baseline), 2x100 bp (improved resolution) [10] | Higher depth ensures sufficient "split-read" support to anchor breakpoints [10]. |

| Allele-Specific Expression (ASE) | ~100 million paired-end reads [10] | Standard paired-end (e.g., 2x75 bp) | Higher depth is essential to accurately estimate variant allele frequencies and minimize sampling error, especially with low tumor purity [10]. |

| Differential Expression (for comparison) | 25 - 40 million paired-end reads [10] | 2x75 bp [10] | Cost-effective sweet spot for robust gene quantification [10]. |

Q2: How does sample quality influence the decision to sequence deeply? RNA integrity is a critical factor. Degraded RNA has reduced complexity, meaning you will sequence more PCR duplicates. Deeper sequencing is a primary strategy to offset this.

Table 2: Guidance for Degraded or Low-Input Samples

| Condition | Recommended Protocol | Sequencing Depth Adjustment | Additional Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Quality RNA (RIN ≥8, DV200 >70%) | Poly(A) selection or rRNA depletion [10] | Standard depth (see Table 1) | - |

| Moderately Degraded RNA (DV200 30-50%) | Prefer rRNA depletion or capture-based protocols [10] | Increase depth by 25-50% [10] | - |

| Highly Degraded/FFPE RNA (DV200 <30%) | Use rRNA depletion or capture-based protocols; avoid poly(A) selection [10] | Sequence deeply with 75-100 million reads [10] | Incorporate UMIs to accurately collapse PCR duplicates [10]. |

| Limited Input (≤10 ng RNA) | Use specialized ultra-low input kits [31] | Sequence deeply (>80 million reads) [10] | UMIs are strongly recommended to correct for amplification bias and duplicates [10] [15]. |

Q3: My fusion gene is lowly expressed. How can I improve detection sensitivity? For low-abundance fusion transcripts, standard RNA-Seq may lack sensitivity due to dilution from non-targeted transcripts. Targeted RNA-Seq is a powerful solution. This method uses biotinylated probes to enrich for hundreds of genes related to cancer before sequencing, dramatically increasing the coverage for your genes of interest. One study showed this method can achieve a 59-fold enrichment for target genes, enabling reliable detection of fusion transcripts even at low abundances [32]. This approach increased the overall diagnostic rate for fusion genes from 63% to 76% compared to conventional methods [32].

Troubleshooting Guide: High-Depth Sequencing

Problem: High Duplication Rates and Low Complexity

- Potential Cause: The library has low molecular complexity, often due to degraded RNA (e.g., from FFPE samples), very low input material, or excessive PCR amplification during library prep.

- Solutions:

- Use Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): Incorporate UMIs during cDNA synthesis. After sequencing, bioinformatic tools can identify and collapse reads that originated from the same original RNA molecule, correcting for PCR bias and providing a more accurate molecular count [10] [15].

- Increase Input RNA: Whenever possible, use the maximum recommended input RNA to increase library complexity.

- Re-assess RNA Quality: Check RNA Integrity Number (RIN) or DV200 value. If quality is poor, consider repeating the extraction or budgeting for a significant increase in sequencing depth.

Problem: Too Many False Positive Fusion Calls

- Potential Cause: Bioinformatic pipelines for fusion detection can generate numerous false positives.

- Solutions:

- Use Multiple Callers and Require Concordance: Implement a pipeline that runs at least two established fusion-finding algorithms (e.g., STARfusion and FusionCatcher) and only consider fusions called by both [32].

- Filter Against Normal Samples: Sequence matched normal tissue from the same patient, if available, to filter out sequencing or mapping artifacts and germline rearrangements.

- Prioritize Fusions with Spanning Reads: Fusions supported by multiple "split-reads" that span the exact breakpoint junction are more reliable than those supported by indirect evidence.

Problem: Inaccurate Allele-Specific Expression Measurement

- Potential Cause: At standard sequencing depths, sampling error can lead to inaccurate estimation of allele frequencies, especially for lowly expressed genes.

- Solutions:

- Sequence Deeper: The primary solution is to increase depth to ≥100 million reads to ensure sufficient counts for each allele [10].

- Ensure High SNP Quality: Use high-quality SNP calls from DNA sequencing (if available) and filter RNA-Seq data for high mapping quality around SNP positions.

Experimental Protocol: A Workflow for High-Depth Applications

The following diagram outlines a general workflow for planning and executing a successful high-depth RNA-Seq experiment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for High-Depth RNA-Seq

| Reagent/Method | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA, allowing sequencing of non-polyadenylated and degraded transcripts. | Essential for bacterial RNA, FFPE samples, and studying non-coding RNAs [10] [31]. |

| Targeted Capture Panels | Biotinylated probes enrich for specific gene sets (e.g., cancer-related genes) prior to sequencing. | Dramatically increases sensitivity for low-abundance targets like fusion genes; requires prior knowledge of targets of interest [32]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random barcodes added to each original RNA molecule during library prep. | Critical for accurate quantification in deep sequencing (>80M reads) and low-input/FFPE workflows; enables bioinformatic removal of PCR duplicates [10] [15]. |

| ERCC Spike-In Controls | Synthetic RNA molecules added to the sample in known concentrations. | Allows for monitoring of technical sensitivity, accuracy, and dynamic range of the entire experiment [32] [31]. |

| Stranded Library Prep Kits | Preserves the information about which DNA strand the transcript originated from. | Crucial for accurate isoform annotation and detecting antisense transcription, reducing misassignment of reads to overlapping genes [33]. |

Critical Bioinformatics Considerations

High-depth sequencing demands a robust bioinformatics pipeline. Below is a visualization of the core steps and potential pitfalls.

- Quality Control and Trimming: Always begin with tools like FastQC to assess read quality. Trimming of adapters and low-quality bases is essential.

- Splice-Aware Alignment: Use aligners like STAR or HISAT2 that can handle reads spanning exon-intron junctions.

- Expression Quantification: Tools like FeatureCounts assign reads to genomic features, while Salmon performs alignment-free quantification, which can be faster.

- UMI Processing: If UMIs were used, tools like

fastporUMI-toolsare needed to extract UMIs and deduplicate reads before alignment or quantification [15]. - Fusion Detection: Employ specialized tools like STARfusion and FusionCatcher. As one study demonstrated, requiring calls from both algorithms significantly reduces false positives [32].

- Compatible References: A common error is using a reference genome (FASTA) from one source (e.g., NCBI) and an annotation file (GTF) from another (e.g., Ensembl). The chromosome names must match perfectly for the quantification to work [34]. Always use FASTA and GTF files from the same database and version.

In bulk RNA-Seq, a one-size-fits-all approach often leads to wasted resources and unreliable data. The integrity of your starting RNA is the most critical factor determining the success of your experiment. High-quality RNA (with an RNA Integrity Number, RIN ≥ 8) and degraded RNA from sources like Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tissues present vastly different challenges. This guide provides a structured framework to adjust your sequencing depth and library preparation protocol based on RNA quality, ensuring that your data is robust and fit for its purpose, whether for differential expression, isoform detection, or fusion discovery.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How do I accurately assess the quality of my RNA sample, especially if it's degraded?

Answer: For high-quality RNA from fresh or frozen tissues, the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) is a standard metric. A RIN ≥ 8 is generally considered suitable for most protocols [35]. However, for degraded samples like FFPE RNA, the RIN can be a poor predictor of sequencing success [36] [37]. In these cases, fragmentation-based metrics are more reliable:

- DV200: The percentage of RNA fragments larger than 200 nucleotides. This was an early standard for FFPE samples [36].

- DV100: The percentage of RNA fragments larger than 100 nucleotides. For highly degraded sample sets (where most DV200 values are < 40%), DV100 is a more useful and discriminating metric than DV200 [38].

Research indicates that a DV100 > 80% provides the best indication of gene diversity and read counts upon sequencing for FFPE samples [36]. It is advisable to avoid processing samples with DV100 < 40%, as they are highly unlikely to generate useful data [38].

FAQ 2: My FFPE RNA is degraded (Low RIN, Low DV200). How should I change my library preparation protocol?

Answer: The standard poly(A) selection method, which targets the poly-A tail of mRNA, is not suitable for degraded RNA as these tails are often lost [38] [35]. You must switch to a ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion protocol using random primers for cDNA synthesis.

- Why rRNA depletion? This method does not depend on an intact poly-A tail or the 5' end of transcripts. It enriches for the transcriptome by removing abundant rRNA, allowing for the sequencing of fragmented mRNAs [38] [35] [39].

- Consider Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): When working with degraded or low-input RNA, PCR duplicates can inflate, reducing usable data. Incorporating UMIs into your library prep allows bioinformatic tools to identify and collapse these duplicates, restoring quantitative accuracy [10].

FAQ 3: How much should I increase sequencing depth for degraded RNA samples?

Answer: Degraded RNA has lower "complexity," meaning there are fewer unique starting molecules. To achieve sufficient coverage for reliable quantification, you must sequence these libraries more deeply. The following table summarizes the recommended adjustments based on DV200 values.

Table 1: Adjusting Sequencing Strategy and Depth Based on RNA Quality

| RNA Quality Metric | Recommended Library Prep | Recommended Sequencing Depth Adjustment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Quality (RIN ≥ 8; DV200 > 70%) | Poly(A) selection or rRNA depletion [10] [38] | Standard depth (e.g., 25-40 million paired-end reads for gene-level differential expression) [10] | Short reads and moderate depth are cost-effective. |

| Moderately Degraded (DV200 30-50%) | Prefer rRNA depletion; avoid poly(A) selection [10] [38] | Increase standard depth by 25-50% [10] | Random priming in rRNA depletion protocols helps capture fragmented transcripts. |

| Highly Degraded (DV200 < 30%) | rRNA depletion or capture-based methods; do not use poly(A) selection [10] | Sequence deeply with ≥ 75-100 million reads [10] | Use UMIs to account for high duplication rates. Expect lower mapping efficiencies. |

FAQ 4: My sequencing depth is adequate, but the gene counts from my FFPE samples are still low and biased. What is the likely cause?

Answer: This is a common issue and is often due to the combined effects of RNA degradation and the library preparation method. Standard poly(A) selection protocols will systematically under-represent the 5' ends of transcripts in degraded samples, as the 3' end is more likely to be captured. Even with rRNA depletion, the fragment length distribution is skewed towards shorter lengths. The solution is to use the correct protocol from the start (rRNA depletion) and to increase sequencing depth to compensate for the reduced effective complexity, as outlined in Table 1 [10] [38]. Furthermore, using stranded libraries is crucial for degraded samples to correctly assign reads to their transcript of origin, which reduces ambiguity [35].

FAQ 5: How do my research goals influence sequencing depth when working with high-quality RNA?

Answer: The required sequencing depth is not independent of your biological question. Higher depth and longer read lengths are needed to resolve complex transcriptomic features. The table below provides a clear guideline based on common research aims.

Table 2: Sequencing Depth and Length Guidance by Research Objective (for High-Quality RNA)

| Research Objective | Recommended Depth (Mapped Reads) | Recommended Read Length | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene-level Differential Expression | ≥ 30 million [10] | 2x 75 bp (paired-end) [10] | Stabilizes fold-change estimates for most genes without wasting resources. |

| Isoform Detection & Alternative Splicing | ≥ 100 million (paired-end) [10] | 2x 75 bp or 2x 100 bp [10] | Higher depth and longer reads are required to span splice junctions and resolve isoform-specific sequences. |

| Fusion Gene Detection | 60 - 100 million [10] | 2x 75 bp (baseline), 2x 100 bp (improved resolution) [10] | Sufficient depth ensures adequate "split-read" support to anchor fusion breakpoints. |

| Allele-Specific Expression (ASE) | ~100 million (paired-end) [10] | Paired-end (length not specified) | Essential depth to accurately estimate variant allele frequencies and minimize sampling error. |

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-Seq Workflows

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Agilent Bioanalyzer RNA Nano Kit | Assesses RNA integrity and concentration, generating RIN and DV values [38] [36]. | The cornerstone of RNA QC. Essential for determining the appropriate protocol for any sample. |

| Poly(A) Selection Kits | Enriches for mRNA by capturing the poly-A tail. | Use only with high-integrity RNA (RIN ≥ 8, DV200 > 70%) [10] [35]. |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Removes ribosomal RNA to enrich for the coding transcriptome. | The preferred method for degraded RNA (FFPE) and bacterial samples [10] [38] [39]. |

| Stranded Library Prep Kits | Preserves the information about which DNA strand the RNA was transcribed from. | Critical for identifying antisense transcripts, accurately quantifying overlapping genes, and analyzing isoform expression [35] [39]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences added to each molecule before amplification. | Allows bioinformatic correction of PCR duplicates, crucial for low-input and degraded RNA studies [10]. |

| FFPE-Specific RNA Extraction Kits | Optimized for de-crosslinking and extracting nucleic acids from FFPE tissue sections. | Designed to handle the chemical modifications and fragmentation in FFPE material, improving yield and quality [38]. |

Experimental Workflow: From Sample QC to Protocol Selection

The following diagram visualizes the decision-making process for planning an RNA-Seq experiment based on sample quality and research goals.

Diagram Title: RNA-Seq Experimental Design Workflow

The guiding principle for modern RNA-Seq is clear: match your sequencing strategy to your biological question and sample quality, not to generic norms [10]. By rigorously assessing RNA integrity using the appropriate metrics (RIN, DV200, DV100), selecting the correct library preparation protocol (poly(A) vs. rRNA depletion), and tailoring sequencing depth to both RNA quality and research aims, you can ensure that your data is of the highest possible quality and interpretative value. Always validate new workflows with a pilot study before scaling up to maximize the return on your sequencing investment.

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the primary advantages of a stranded, paired-end RNA-seq approach?

This design provides multiple, synergistic benefits that maximize data utility from your sequencing depth [40] [39]. Strandedness allows you to accurately determine the originating DNA strand of a transcript. This is crucial for identifying antisense transcripts, resolving expression levels of overlapping genes transcribed from opposite strands, and producing more accurate gene expression quantifications [41] [42] [43]. Paired-end sequencing facilitates more accurate read alignment, enables the detection of genomic rearrangements (like gene fusions), and provides critical information for identifying novel splice variants and transcript isoforms [40] [44].

My sequencing data shows a high percentage of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) reads. What could be the cause?

High rRNA contamination can stem from several issues during library preparation. The table below outlines common root causes and solutions based on the strandedness of the observed rRNA reads [45].

| Observed Read Strandedness | Likely Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Read 1 maps to antisense strand; Read 2 maps to sense strand (matches endogenous rRNA) | Suboptimal binding of rRNA removal probes to target rRNA [45] | Mix reagents completely; use correct RNA input amount; verify correct incubation temperature; ensure probe species compatibility [45] |

| Read 1 and Read 2 map to both strands (mixed strandedness) | Inefficient capture of rRNA-probe complexes by magnetic beads, leading to probes in the final library [45] | Follow bead handling best practices: equilibrate to room temp, mix thoroughly before use, use validated magnetic stand, avoid frozen beads [45] |

| Mixed strandedness, plus reads in intronic/intergenic regions | DNA contamination in the RNA input [45] | Perform DNase treatment on the input RNA sample prior to library preparation [45] |

For a standard gene expression profiling study, is paired-end sequencing always necessary?

Not always. For a straightforward snapshot of highly expressed genes, short single-reads (e.g., 50-75 bp) can be a cost-effective choice that still enables accurate gene counting [4] [43]. However, if your goals extend to alternative splicing analysis, novel transcript discovery, or detecting gene fusions, the investment in paired-end sequencing (e.g., 2x75 bp or 2x100 bp) is justified, as the additional structural information is indispensable [4] [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Achieving Optimal RNA Input Quality

The success of any advanced library prep design hinges on starting with high-quality genetic material.

- Assess RNA Integrity: Always check RNA quality using an instrument like the Agilent Bioanalyzer. The RNA sample should have an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) higher than 7. For eukaryotic samples, intact total RNA will show sharp 28S and 18S rRNA bands on a gel, with a 2:1 intensity ratio [41].

- Ensure DNA-Free RNA: RNA should be completely free of genomic DNA contamination. DNase digestion of the purified RNA with an RNase-free DNase is strongly recommended [41] [45].

- Accurate Quantification: Accurately quantify the RNA sample prior to library construction using a method sensitive to RNA, such as a Bioanalyzer. Note that spectrophotometry (e.g., NanoDrop) can overestimate concentration due to contaminants [41].

Guide: Selecting Read Depth and Length for Your Project Goals

The following table summarizes recommendations to help you allocate your sequencing budget effectively, ensuring sufficient depth and appropriate read length for your specific aims [4] [43].

| Experimental Goal | Recommended Read Depth (Million Reads/Sample) | Recommended Read Type & Length |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Profiling (snapshot of highly expressed genes) | 5 - 25 million [4] | Short single-reads (50-75 bp) [4] |

| Global Expression & Splicing Analysis | 30 - 60 million [4] | Paired-end (e.g., 2x75 bp or 2x100 bp) [4] [39] |

| Novel Transcript Assembly/Deep Splicing | 100 - 200 million [4] | Longer paired-end (e.g., 2x100 bp or longer) [4] |

| Targeted RNA Expression (e.g., Fusion Panels) | ~3 million (panel-specific) [4] | Varies by panel; often single-read [4] |

| miRNA / Small RNA Analysis | 1 - 5 million [4] | Single-read (usually 50 bp) [4] |

Experimental Protocol: Core Workflow for Stranded, Paired-End mRNA Sequencing

The following protocol outlines the key steps for preparing a stranded, paired-end mRNA-seq library, such as with the Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep kit.

- mRNA Enrichment: Isolate messenger RNA (mRNA) from total RNA using oligo-dT magnetic beads to capture polyadenylated transcripts. This depletes the abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA) [43] [39].

- RNA Fragmentation and Priming: Fragment the purified mRNA into uniform pieces (typically 200-300 nt) and prime with random hexamers [41] [42].

- First-Strand cDNA Synthesis: Synthesize complementary DNA (cDNA) using a reverse transcriptase to create first-strand cDNA [41] [42].

- Second-Strand Synthesis with Strand Marking: Synthesize the second cDNA strand. In stranded kits, this involves incorporating dUTP in place of dTTP, thereby labeling the second strand. Other methods use ligation to preserve strand information [42] [39].

- dA-Tailing and Adapter Ligation: Prepare the double-stranded cDNA for adapter ligation by adding an 'A' base to the 3' ends. Then, ligate indexed sequencing adapters [41].

- dUTP Strand Degradation (if applicable): Enzymatically degrade the dUTP-labeled second strand. This ensures that only the first strand, representing the original RNA sequence, is amplified and sequenced, preserving strand-of-origin information [42].

- Library Amplification: Perform a limited-cycle PCR to enrich for library fragments that have adapters ligated on both ends and to add full sequencing motifs and index sequences [42].

- Library QC and Sequencing: Quantify the final library and check its size distribution using a method like the Agilent Bioanalyzer. Pool libraries at equimolar concentrations for paired-end sequencing on an Illumina platform [41].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Stranded, Paired-End Prep |

|---|---|

| Oligo-dT Magnetic Beads | Enriches for polyadenylated mRNA from total RNA, providing the specific transcript pool for sequencing [43] [39]. |

| Ribo-Zero / Ribo-Zero Plus | Depletes ribosomal RNA (rRNA) from total RNA for "Total RNA" protocols, preserving both coding and non-coding RNA [45]. |

| dUTP Nucleotides | The key reagent in dUTP-based stranded kits; incorporated during second-strand synthesis to label and enable subsequent degradation of this strand, preserving strand information [42] [39]. |

| Stranded mRNA Prep Kit | (e.g., Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep). An integrated kit containing optimized reagents for the entire workflow from mRNA to sequencing-ready libraries [40]. |

| RNase-free DNase I | Digests and removes contaminating genomic DNA from RNA samples prior to library construction, preventing background from non-transcribed regions [41] [45]. |

| SPRI Beads | (Solid Phase Reversible Immobilization). Used for precise size selection and clean-up steps throughout the protocol, such as purifying cDNA after synthesis and adapter ligation [42]. |

Solving Common Pitfalls: A Troubleshooter's Guide to Depth and Replicate Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Experimental Design

What is the core dilemma between replicates and sequencing depth?

The dilemma involves balancing finite research resources between increasing the number of biological replicates (independent biological samples per condition) and increasing the sequencing depth (number of reads per sample). Empirical evidence demonstrates that for standard differential expression analysis, investing in more biological replicates often provides greater scientific returns than pursuing extreme sequencing depth, as it significantly improves the detection of genuine biological signals and the replicability of findings [46] [10].

Why are more biological replicates so critical?

Biological replicates account for the natural variation that exists between individuals, tissues, or cell populations. Using an insufficient number of replicates means the experiment cannot reliably distinguish true biological differences from random natural variation. This directly leads to two problems:

- Low Replicability: Results from an underpowered experiment are unlikely to be consistent in a follow-up study. One analysis of 18,000 subsampled RNA-seq experiments found that results from studies with small cohort sizes (e.g., fewer than 5 replicates) are unlikely to replicate well [46] [47].

- High False Discovery Rates: Without enough replicates, statistical models lack the power to accurately identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs), increasing the likelihood of both false positives and false negatives [46] [48].

When should I consider increasing sequencing depth?

While replicates are paramount for statistical power, there are specific research goals where increased depth is necessary. The following table outlines recommendations based on common analytical objectives [10]:

| Analytical Goal | Recommended Sequencing Depth | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Gene-level Differential Expression | 25-40 million paired-end reads | This depth is a cost-effective "sweet spot" that stabilizes gene-level fold-change estimates across most expression quantiles [10]. |

| Isoform Detection & Alternative Splicing | ≥ 100 million paired-end reads | Comprehensive isoform coverage requires deeper sequencing to capture low-abundance splice junctions and events [10]. |

| Fusion Gene Detection | 60-100 million paired-end reads | Adequate depth ensures sufficient "split-read" support to reliably anchor and identify fusion breakpoints [10]. |

| Allele-Specific Expression (ASE) | ~100 million paired-end reads | High depth is essential to accurately estimate variant allele frequencies and minimize sampling error, especially in heterogeneous samples like tumors [10]. |

What is the minimum number of replicates I should use?

While the ideal number depends on the expected effect size and biological variability of your system, several studies provide clear guidance against using very few replicates:

- Absolute Minimum: Most experts caution against using fewer than 3 biological replicates per condition [7].

- Recommended Range: For robust and reliable results in differential expression analysis, at least 4 to 8 biological replicates per sample group are recommended [7]. Some studies suggest that to identify the majority of DEGs, at least 6 to 12 replicates are necessary [46] [47].

Empirical data from large-scale studies provides quantitative evidence for prioritizing replicates. The following table summarizes findings from a study that performed 18,000 subsampled RNA-seq experiments across 18 different datasets to test the replicability of results with small cohort sizes [46] [47].

| Cohort Size (Replicates per Condition) | Key Finding on Replicability & Precision |

|---|---|

| Fewer than 5 | Results are unlikely to replicate well. High heterogeneity in precision is observed, meaning some datasets may have many false positives [46] [47]. |

| More than 5 | 10 out of 18 studied data sets achieved high median precision despite low overall recall. This indicates that while these studies miss many true positives (low recall), the genes they do identify as significant are likely to be correct (high precision) [46] [47]. |

| N/A (Methodology) | A simple bootstrapping procedure (resampling the available data) can be used to estimate the expected replicability and precision for a given dataset, helping researchers gauge the reliability of their results even with limited samples [46] [47]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Resampling Method to Estimate Replicability

For researchers concerned about their own study's power, the following workflow, derived from empirical studies, provides a way to estimate expected replicability using a bootstrapping approach [46] [47].

Title: Resampling Workflow to Estimate Replicability

Principle: This method involves using a large, existing RNA-seq dataset as a "ground truth" to simulate what would happen if the study were run multiple times with a small sample size [46] [47].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Dataset Selection: Identify a large RNA-seq dataset (e.g., from TCGA or GEO) that is relevant to your biological context and has a sufficient number of replicates (e.g., >50 per condition) to serve as a robust reference [46] [47].

- Subsampling: Programmatically randomly select a small cohort of size N (e.g., 3, 5, or 7 replicates) from the full dataset for both the control and perturbed conditions. This represents one simulated "underpowered experiment." [46] [47]

- Differential Expression Analysis: Run your standard differential expression analysis pipeline (e.g., using DESeq2 or limma) on this subsampled cohort to identify a list of statistically significant DEGs [46] [48].

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2 and 3 a large number of times (e.g., 100 iterations) to generate many simulated experimental results [46] [47].

- Calculate Overlap Metrics: Analyze the lists of DEGs from all the simulated experiments. Calculate metrics like:

- Pairwise Overlap/Jaccard Index: The average overlap of DEGs between any two simulated experiments.

- Precision and Recall: If a "ground truth" set of DEGs is available from the full dataset, calculate how many of the DEGs found in the small cohorts are true positives (precision) and how many true DEGs are recovered (recall) [46] [47].

- Interpretation: A low pairwise overlap indicates that results from a cohort of size N are not easily replicable. Low precision suggests a high false positive rate, while low recall indicates most true DEGs are being missed [46].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table lists key reagents and materials critical for conducting a well-controlled bulk RNA-seq experiment in a drug discovery or research setting [7] [15].

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Biological Replicates | Independent biological samples (e.g., from different animals, patients, or cell culture passages). Critical for capturing biological variation and ensuring statistical power and generalizability [7]. |

| ERCC Spike-In Controls | Synthetic RNA molecules of known concentration added to each sample. Used to standardize RNA quantification, assess technical performance (sensitivity, dynamic range), and control for technical variation between runs [15]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences added to each molecule during library prep. UMIs allow for accurate counting of original RNA molecules by correcting for PCR amplification bias and errors, which is crucial for low-input samples or deep sequencing [10] [15]. |

| rRNA Depletion or Poly-A Selection Kits | Kits to remove abundant ribosomal RNA (which can constitute >80% of total RNA) or to enrich for polyadenylated mRNA. The choice depends on the organism and RNA species of interest (e.g., rRNA depletion is needed for non-polyadenylated RNAs, lncRNAs, or bacterial transcripts) [15]. |

| Strand-Specific Library Prep Kits | Kits that preserve the strand orientation of the original RNA transcript during cDNA synthesis. This prevents ambiguity in determining which DNA strand corresponds to the original RNA, crucial for accurate annotation of overlapping genes and anti-sense transcription [25] [15]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What causes high duplication rates in RNA-seq, and why is it a bigger problem for degraded or low-input samples?

High duplication rates occur when many sequencing reads are exact copies originating from the same original DNA fragment, primarily due to PCR over-amplification during library preparation [49]. This is a more significant problem for degraded or low-input samples for two key reasons:

- Limited Starting Material: With low-input samples, you begin with fewer unique RNA molecules. To generate a sufficient library for sequencing, more PCR cycles are required. This excessive amplification artificially inflates the number of reads from each unique starting molecule [49].

- Fragmented RNA: In degraded samples (like FFPE-derived RNA), the RNA is already fragmented into small pieces. This results in a lower diversity of possible fragments, increasing the likelihood that independent molecules will be sequenced from identical genomic locations. Furthermore, short fragments may be lost during library cleanup, further reducing complexity and increasing duplication rates [50] [38].

What are UMIs, and how do they help reduce false duplication?

Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) are short, random oligonucleotide barcodes used to tag each original molecule in a sample library before any PCR amplification steps [51] [52].

- Problem Without UMIs: Traditional bioinformatics identifies duplicates based solely on identical genomic coordinates. This cannot distinguish between true PCR duplicates (multiple reads from one original molecule) and reads from two independent but identical molecules, leading to the false removal of unique biological data [49].

- Solution With UMIs: By providing a unique "barcode" for each starting molecule, UMIs enable precise tracking. During data analysis, reads that share both the same genomic alignment and the same UMI are identified as technical replicates (PCR duplicates) from a single molecule. Reads that share genomic coordinates but have different UMIs are correctly identified as unique biological molecules [51] [52]. This process, called deduplication, provides a true count of the original molecules, drastically improving quantification accuracy.

My RNA is from FFPE tissue. Should I use poly-A selection or rRNA depletion for library prep?