Optimizing Convolutional Neural Networks for RNA Binding Prediction: From Architectures to Clinical Applications

Accurate prediction of RNA-binding protein (RBP) sites is crucial for understanding post-transcriptional gene regulation and developing therapeutic strategies.

Optimizing Convolutional Neural Networks for RNA Binding Prediction: From Architectures to Clinical Applications

Abstract

Accurate prediction of RNA-binding protein (RBP) sites is crucial for understanding post-transcriptional gene regulation and developing therapeutic strategies. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for this complex task. We explore the foundational principles of RBP binding and the limitations of experimental methods, then delve into advanced CNN architectures including hybrid CNN-RNN models and graph convolutional networks. The article systematically addresses key optimization strategies, from novel techniques like fuzzy logic-enhanced optimizers to advanced encoding schemes for sequence and structure data. Finally, we present rigorous validation frameworks and performance comparisons across diverse RBP datasets, offering practical insights for implementing these cutting-edge computational approaches in biomedical research.

The Foundation of RNA-Protein Interactions: Biological Significance and Computational Challenges

The Crucial Role of RNA-Binding Proteins in Post-Transcriptional Regulation

Post-transcriptional regulation represents a critical control layer in gene expression, occurring after RNA synthesis but before protein translation. This process allows cells to rapidly adapt protein levels to changing environmental conditions and fine-tune gene expression with spatial and temporal precision [1]. RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) serve as master regulators of this process, determining the fate and function of virtually all RNA molecules within the cell [2] [3].

RBPs achieve this remarkable control through several sophisticated mechanisms. They directly influence RNA stability by protecting transcripts from degradation or marking them for decay, often by modulating access to ribonucleases [3]. They regulate translation efficiency by controlling ribosome access to the ribosome binding site (RBS) [3]. Additionally, RBPs guide subcellular localization of transcripts and influence alternative splicing patterns, enabling a single gene to produce multiple protein variants [2] [1]. The importance of these regulatory mechanisms is highlighted by the surprisingly weak correlation observed between RNA abundance and protein levels in cells, underscoring that transcript quantity alone is a poor predictor of functional protein output [3].

Dysregulation of RBP function has profound pathological consequences. Mutations or altered expression of RBPs are implicated in neurodegenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia, various cancers, and inflammatory disorders [4] [1] [5]. For example, ELAV-like proteins, a well-studied RBP family, stabilize mRNAs encoding critical proteins involved in neuronal function, cell proliferation, and inflammation, and their dysregulation contributes to disease pathogenesis [1].

Technical FAQs: Experimental Challenges in RBP Research

Q1: What are the primary experimental methods for identifying RBP binding sites, and what are their limitations?

Experimental methods for RBP binding site identification have evolved significantly, but each comes with distinct challenges:

- CLIP-seq (Cross-Linking and Immunoprecipitation followed by Sequencing) and its variants (HITS-CLIP, PAR-CLIP, iCLIP) are considered gold-standard methods. These techniques use UV crosslinking to covalently link RBPs to their bound RNA molecules in living cells, followed by immunoprecipitation and high-throughput sequencing [6] [5]. The main limitations include being labor-intensive, time-consuming, costly, and sensitive to experimental variance such as antibody specificity and crosslinking efficiency [4] [6].

- RNA-Bind-n-Seq is an in vitro technique that determines the binding preferences of RBPs [6].

- Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays (EMSAs) are used to study specific RNA-protein interactions but are low-throughput [4] [6].

- High-throughput imaging approaches provide spatial information but require specialized instrumentation [6].

A significant challenge across all these methods is the accurate determination of binding sites at nucleotide resolution, as signal noise and technical artifacts can obscure true binding events [5].

Q2: Our CLIP-seq data shows high background noise. What optimization strategies can improve signal-to-noise ratio?

High background noise in CLIP-seq experiments can stem from several sources. The PARalyzer algorithm can help by using kernel density estimation to discriminate crosslinked sites from non-specific background by analyzing thymidine-to-cytidine conversion patterns specific to PAR-CLIP protocols [6]. Optimizing crosslinking conditions (UV intensity and duration) and rigorous washing steps during immunoprecipitation can reduce non-specific RNA retention. Using control samples (e.g., without crosslinking or without immunoprecipitation) is essential for distinguishing specific binding from background. Ensuring high-quality antibodies with proven specificity for your target RBP is also critical [6].

Q3: How can we validate the functional consequences of an RBP binding to a specific mRNA?

Validation requires a multi-faceted approach:

- Measure mRNA stability using transcription inhibition assays (e.g., actinomycin D) followed by qRT-PCR to track decay rates of the target mRNA when the RBP is present versus absent [1] [3].

- Assess translation efficiency through polysome profiling, which separates mRNAs based on the number of bound ribosomes, followed by qRT-PCR or RNA-seq of fractionated samples [1].

- Manipulate RBP levels via knockdown, knockout, or overexpression and measure changes in target protein levels using Western blot or immunofluorescence, which directly reflects the functional outcome of post-transcriptional regulation [1].

Computational FAQs: Predicting RBP Interactions with Deep Learning

Q1: Why are Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) particularly suited for predicting RBP binding sites?

CNNs excel at identifying local, position-invariant patterns—precisely the characteristic of short, conserved sequence motifs that often define RBP binding sites [7] [8]. When applied to RNA sequences, CNN filters (kernels) act as motif detectors that scan across sequences and learn to recognize these informative patterns directly from the data, eliminating the need for manual feature engineering [4] [6] [8]. Furthermore, CNN architectures efficiently handle the high dimensionality of biological sequences and can be designed to integrate diverse input features, including RNA secondary structure information [5].

Q2: What are the key hyperparameters to optimize when training a CNN for RBP binding prediction, and what optimization methods are most effective?

The performance of CNN models is highly dependent on proper hyperparameter tuning. Key parameters include the number and size of convolutional filters, learning rate, batch size, dropout rate for regularization, and the network's depth [6].

Table 1: Comparison of Hyperparameter Optimization Methods for CNN Models

| Optimization Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Reported Performance (AUC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grid Search [6] | Exhaustive search over a predefined parameter grid | Guaranteed to find best combination within grid | Computationally expensive; infeasible for high-dimensional spaces | ~92.68-94.42% on ELAVL1 datasets |

| Random Search [6] | Random sampling from parameter distributions | More efficient than grid search; better for independent parameters | May miss important regions; less efficient with dependent parameters | Similar to Grid Search (high 80% mean AUC) |

| Bayesian Optimization [6] | Builds probabilistic model to guide search toward promising parameters | Most sample-efficient; well-suited for expensive evaluations | Complex implementation; performance depends on surrogate model | ~85.30% mean AUC on 24 datasets |

| FuzzyAdam [4] | Dynamically adjusts learning rate using fuzzy logic based on gradient trends | Stable convergence; reduced oscillation and false negatives | Novel method, less widely tested | Up to 98.39% accuracy on binding site classification |

Q3: How can we incorporate RNA secondary structure information into CNN models to improve prediction accuracy?

RNA secondary structure provides critical context for RBP binding, as many proteins recognize specific structural motifs rather than just linear sequences [5]. Integration strategies include:

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Represent RNA secondary structure as a graph where nodes are nucleotides and edges represent sequential bonds or base pairs (stem loops). Models like RMDNet use GNNs with DiffPool to learn from these structural graphs and fuse the features with sequence-based CNN outputs [5].

- Multi-branch Architectures: Hybrid models like RMDNet use separate network branches (CNN, CNN-Transformer, ResNet) to capture features at different sequence scales, which are then fused with structural representations [5].

- Dedicated Structural Channels: Methods like DeepRKE use additional CNN modules specifically designed to process RNA secondary structure features alongside sequence inputs [5].

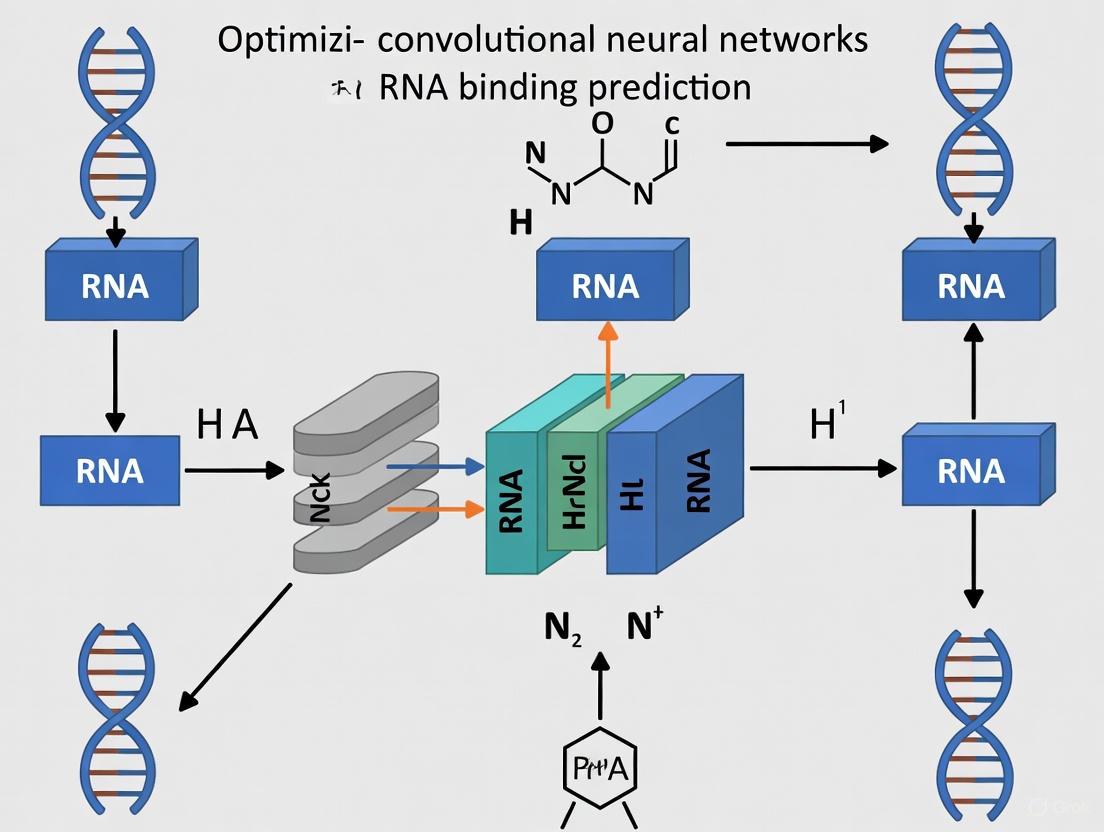

The following diagram illustrates a typical workflow for predicting RBP binding sites using a hybrid deep learning approach that integrates both sequence and structural information:

Troubleshooting Computational Models

Problem: The CNN model achieves high training accuracy but performs poorly on validation data.

Solutions:

- Implement Robust Regularization: Increase dropout rates, add L2 weight regularization, or use early stopping to prevent the model from memorizing the training data instead of learning generalizable patterns [6].

- Address Data Imbalance: Binding sites typically represent a small fraction of any RNA sequence, creating class imbalance. Use oversampling of minority classes, undersampling of majority classes, or weighted loss functions that penalize misclassification of the positive class more heavily [6].

- Expand and Diversify Training Data: If the training set is too small or lacks diversity, the model cannot learn generalizable features. Incorporate data from multiple CLIP-seq experiments or public databases like RBP-24 and RBP-31 [5].

- Simplify Model Architecture: Reduce model complexity by decreasing the number of layers or filters. An overly complex model is more likely to overfit to noise in the training data [6].

Problem: Predictions lack biological interpretability—the model works but we don't understand why.

Solutions:

- Motif Extraction from CNN Filters: Visualize the sequence patterns that maximally activate first-layer convolutional filters. These often correspond to known RBP binding motifs, as demonstrated in studies extracting motifs from CNN kernels that matched experimentally validated patterns [5].

- Attention Mechanisms: Incorporate attention layers into the model architecture. These layers learn to "pay attention" to the most informative regions of the input sequence, providing visualizable importance scores for each nucleotide position [6].

- In Silico Mutagenesis: Systematically mutate nucleotides in the input sequence and observe changes in prediction scores. Positions where mutations cause significant score drops likely represent critical binding residues [8].

Performance Evaluation and Benchmarking

Rigorous evaluation is essential when developing and comparing RBP binding prediction models. Standard performance metrics provide different insights into model capabilities.

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics for RBP Binding Site Prediction Models

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation in RBP Binding Context |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | (TP + TN) / (TP + TN + FP + FN) | Overall correctness across binding and non-binding sites [4] |

| Precision | TP / (TP + FP) | When the model predicts a binding site, how often is it correct? [4] |

| Recall (Sensitivity) | TP / (TP + FN) | What proportion of actual binding sites does the model detect? [4] |

| F1-Score | 2 × (Precision × Recall) / (Precision + Recall) | Harmonic mean of precision and recall [4] |

| AUC (Area Under ROC Curve) | Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve | Overall measure of classification performance across all thresholds [6] |

Recent advanced models have demonstrated strong performance on benchmark datasets. The FuzzyAdam optimizer achieved impressive results with 98.39% accuracy, 98.39% F1-score, 98.42% precision, and 98.39% recall on a balanced dataset of RNA binding sequences [4]. The RMDNet framework, which integrates multiple network branches with structural information, outperformed previous state-of-the-art models including GraphProt, DeepRKE, and DeepDW across multiple metrics on the RBP-24 benchmark [5]. Optimized CNN models applied to specific RBPs like ELAVL1 have reached AUC values exceeding 94% [6].

Table 3: Key Reagents and Resources for RBP Binding Research

| Resource | Type | Function and Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLIP-seq Kits | Experimental | Protocol-optimized kits for crosslinking, immunoprecipitation, and library prep | Commercial kits can improve reproducibility [6] |

| RBP-Specific Antibodies | Experimental | Essential for immunoprecipitation in CLIP-seq protocols | Validate specificity for target RBP [6] |

| Benchmark Datasets | Computational | Curated datasets for training and evaluating prediction models | RBP-24, RBP-31, RBPsuite2.0 [6] [5] |

| RNA Secondary Structure Prediction | Computational | Tools to predict RNA folding for structural feature input | RNAfold [5] |

| Pre-trained Models | Computational | Models for transfer learning to overcome small dataset limitations | Available in repositories; useful for novel RBPs [9] |

| Optimization Frameworks | Computational | Libraries for hyperparameter tuning and model optimization | Bayesian optimization, FuzzyAdam [4] [6] |

The field of RBP research continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping its future. Multi-modal deep learning approaches that integrate sequence, structure, and additional genomic contexts (e.g., epigenetic marks, conservation scores) show promise for capturing the full complexity of RBP-RNA interactions [5]. The development of explainable AI methods will be crucial for moving beyond "black box" predictions to biologically interpretable models that generate testable hypotheses about regulatory mechanisms [6] [8]. Furthermore, transfer learning approaches, where models pre-trained on large-scale genomic data are fine-tuned for specific RBPs or cell conditions, will help address the challenge of limited training data for many RBPs [9].

In conclusion, RNA-binding proteins represent fundamental regulators of gene expression with profound implications for both basic biology and human disease. The integration of sophisticated experimental methods with advanced computational approaches, particularly optimized deep learning models, is dramatically accelerating our ability to map and understand these crucial interactions. As these technologies continue to mature and converge, they promise to unlock new therapeutic strategies for the numerous diseases driven by post-transcriptional dysregulation.

This guide addresses the significant experimental limitations of Cross-Linking and Immunoprecipitation sequencing (CLIP-seq) methods, focusing on their high cost and time-intensive nature. For researchers aiming to optimize convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for RNA-binding prediction, understanding these wet-lab constraints is crucial for designing efficient, cost-effective computational workflows that can augment or guide experimental efforts.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary factors contributing to the high cost of a CLIP-seq project?

The overall cost extends far beyond simple sequencing fees. The major cost components are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Primary Cost Components of a CLIP-seq Project

| Cost Category | Specific Elements | Impact on Budget |

|---|---|---|

| Sample & Experimental Design | Clinically relevant sample collection, informed consent procedures, Institutional Review Board (IRB) oversight, secure data archiving [10]. | Significant for patient-derived samples; lower for standard cell lines. |

| Library Preparation & Sequencing | Specialized reagents, high-quality/validated antibodies, labor for complex, multi-step protocol, sequencing consumables [10] [11]. | A major and direct cost driver. |

| Data Management & Analysis | High-performance computing storage and transfer, bioinformatics expertise for specialized computational analysis [10] [12]. | Often a "hidden" cost that can rival or exceed sequencing costs. |

2. Why is CLIP-seq considered a time-intensive method?

The CLIP-seq workflow consists of multiple, complex hands-on steps that cannot be easily expedited. The procedure requires specialized expertise and careful handling at each stage, from crosslinking through to library preparation, with the entire process taking several days to over a week to complete before sequencing even begins [11]. The subsequent data analysis is also a major bottleneck, requiring specialized bioinformatics tools and expertise to process and interpret the data, which differs significantly from more standardized RNA-seq analysis [12].

3. Our lab lacks a high-quality antibody for our RNA-binding protein (RBP) of interest. What are our options?

The lack of immunoprecipitation-grade antibodies is a common challenge. The standard alternative is to ectopically express an epitope-tagged RBP (e.g., FLAG, V5). However, a more robust solution is to use CRISPR/Cas9-based genomic editing to generate an endogenous epitope-tagged RBP. This ensures the protein is expressed at physiological levels from its native promoter, avoiding artifacts associated with overexpression and leading to more biologically relevant results [13].

4. How can computational models help mitigate the cost and time limitations of CLIP-seq?

Computational models, particularly deep learning, offer a powerful complementary approach.

- Cost Reduction: Once trained, models can predict RBP binding sites in silico at a fraction of the cost of a new experiment [6] [14].

- Guidance for Experiments: Models can prioritize high-value RBP targets for experimental validation, making wet-lab research more efficient [6].

- Hyperparameter Optimization: For CNN models, employing optimization methods like Bayesian optimizers, grid search, and random search is critical to maximize prediction accuracy (e.g., achieving AUC scores over 94% on specific RBP datasets), thereby increasing the reliability of computational predictions [6] [14].

5. What are the key limitations in the CLIP-seq workflow that can lead to experimental failure or biased results?

Several technical points in the protocol are critical for success:

- Low UV Crosslinking Efficiency: UV crosslinking has low efficiency compared to other methods, which can lead to the loss of relevant interactions and partial data [11].

- Antibody Specificity: Non-specific antibodies can immunoprecipitate incorrect RNA-protein complexes, compromising the entire experiment [13] [15].

- RNA Fragmentation Bias: The RNase digestion step can introduce biases, as the fragmentation pattern may not be uniform across all transcripts [11].

- Difficulty with Low-Abundance Interactions: The method is generally less effective at detecting transient or low-abundance RNA-protein interactions [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Prohibitive Costs for Large-Scale RBP Screening

Problem: It is financially unfeasible to perform CLIP-seq for dozens of RBPs across multiple conditions.

Solutions:

- Leverage Public Data: Begin research by mining existing CLIP-seq data from public repositories to inform hypotheses and guide targeted experiments.

- Employ Computational Pre-screening: Use established CNN models to predict the most promising RBP-RNA interactions and prioritize these for experimental validation [6] [14].

- Optimize Sequencing Depth: For follow-up validation experiments, consider lower sequencing depths to confirm binding at specific sites rather than performing discovery-level sequencing.

Issue: Extensive Time Commitment from Experiment to Analysis

Problem: The journey from cell culture to analyzed data takes too long, slowing down research progress.

Solutions:

- Adopt Streamlined CLIP Variants: Consider modern protocols like eCLIP or irCLIP, which are designed to improve library preparation efficiency and success rates [16] [15].

- Utilize Automated Computational Pipelines: Implement integrated bioinformatics suites like

CLIPSeqTools[12], which provide pre-configured pipelines to run a standardized set of analyses from raw sequencing data with minimal user input, significantly accelerating the data analysis phase. - Establish a Standardized Wet-Lab Protocol: Reduce optimization time and variability by adopting a single, well-documented CLIP-seq protocol for all lab members.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials for a CLIP-seq experiment and their critical functions.

Table 2: Key Reagents for CLIP-seq Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Antibody | Specific immunoprecipitation of the target RBP [13]. | The most critical reagent. Must be validated for immunoprecipitation. |

| UV Light Source (254 nm or 365 nm) | In vivo crosslinking of RNA and proteins that are in direct contact [11] [15]. | UV-C (254 nm) for standard CLIP; UV-A (365 nm) for PAR-CLIP. |

| RNase Enzyme | Fragments RNA into manageable pieces post-crosslinking [11]. | Requires titration for optimal fragmentation. |

| Proteinase K | Digests the protein component of the complex, releasing the cross-linked RNA fragment [11] [15]. | Leaves a short peptide on the RNA, which can cause reverse transcriptase to truncate. |

| Adaptors and Primers | Enables reverse transcription and PCR amplification for library preparation [11]. | May include barcodes (for multiplexing) and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs for PCR duplicate removal). |

| Magnetic Beads | Facilitates the capture and washing of antibody-RBP-RNA complexes [11]. | Protein A/G beads are commonly used. |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

CLIP-seq Wet-Lab and Analysis Workflow

The following diagram outlines the core steps in a standard CLIP-seq protocol, highlighting stages that are particularly costly or time-consuming.

Integrated Experimental-Computational Research Strategy

This diagram illustrates a synergistic workflow that combines targeted CLIP-seq experiments with computational modeling to overcome the limitations of either approach alone.

FAQs: Troubleshooting Your RBP Binding Site Prediction Experiments

Q1: My CNN model for predicting RBP binding sites is underperforming. What are the first hyperparameters I should optimize? Hyperparameter optimization is critical for maximizing model performance. You should systematically tune the following using established optimization methods [6]:

- Learning Rate: Fundamental for model convergence.

- Batch Size: Affects the stability and speed of learning.

- Activation Function: Choosing the right function (e.g., ReLU, sigmoid) can impact learning capability.

- Number of Hidden Layers/Neurons: Determines the model's capacity to learn complex features.

Empirical results demonstrate that using optimizers like Bayesian Optimizer, Grid Search, and Random Search can significantly improve performance, with models achieving AUCs of up to 94.42% on specific datasets like ELAVL1C [6]. Begin with a Bayesian Optimizer, as it efficiently narrows down the optimal hyperparameter set with fewer trials.

Q2: How can I incorporate both sequence and RNA secondary structure into a single model effectively? Integrating sequence and structure requires a thoughtful encoding strategy. Best practices include [17] [18]:

- Unified Input Representation: Use one-hot encoding to represent both the primary sequence (A, C, G, U) and the predicted secondary structure (e.g., paired, unpaired) as separate but aligned input channels.

- Dedicated Feature Learning Branches: Employ parallel neural network branches (e.g., Convolutional Neural Networks, or CNNs) to learn abstract features from the sequence and structure inputs independently.

- Feature Integration: Combine the learned features from both branches and feed them into a final classifier. More advanced models use a Bidirectional LSTM (BLSTM) layer after the CNNs to capture long-range dependencies between the discovered sequence and structure motifs [17] [18].

Q3: I only have RNA sequence data, not the secondary structure. Can I still predict binding sites accurately? Yes, but with a potential loss of predictive power and biological insight. While sequence-only models like DeepBind exist, studies consistently show that models integrating secondary structure information, such as iDeepS and DeepRKE, generally achieve higher accuracy [17] [19] [18]. If you lack structure data, you can use tools like RNAShapes to computationally predict the secondary structure from your sequence data as a preprocessing step [18].

Q4: What is the advantage of using a deep learning approach over traditional motif-finding tools like MEME? Traditional tools like MEME often rely on hand-designed features and may struggle with the interdependencies between sequence and structure [19]. Deep learning methods offer two key advantages [17] [19]:

- Automatic Feature Extraction: CNNs automatically learn relevant sequence and structure motifs directly from the data without prior domain knowledge.

- Higher Predictive Accuracy: Models like iDeepS have been shown to outperform other methods, achieving a mean AUC of 0.86 across 31 CLIP-seq experiments and improving AUC by up to 12% on specific proteins compared to structure-profile-based methods [19].

Performance Comparison of Key Computational Methods

The following table summarizes the performance and characteristics of several prominent RBP binding site prediction tools, providing a benchmark for your experiments.

| Method | Input Features | Core Methodology | Reported Performance (AUC) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iDeepS [17] [19] | Sequence, Secondary Structure | CNNs + BLSTM | 0.86 (mean on 31 datasets) | Automatically extracts both sequence and structure motifs. |

| DeepPN [20] | Sequence | CNN + Graph Convolutional Network (ChebNet) | High performance on 24 datasets (specific values not listed in summary) | Uses a parallel network to capture different feature views. |

| DeepRKE [18] | Sequence, Secondary Structure | k-mer Embedding + CNNs + BiLSTM | Outperforms 5 state-of-the-art methods on two benchmark datasets | Uses distributed representations (embeddings) for k-mers. |

| Optimized CNN [6] | Sequence | CNN (with Hyperparameter Optimization) | 94.42% (on ELAVL1C), 85.30% (mean on 24 datasets) | Demonstrates the impact of systematic hyperparameter tuning. |

| GraphProt [19] | Sequence, Secondary Structure | Graph Kernel + SVM | 0.82 (mean on 31 datasets) | Models RNA as a graph structure. |

| DeepBind [19] | Sequence | CNN | 0.85 (mean on 31 datasets) | A pioneering deep learning model for binding site prediction. |

Experimental Protocols for Cited Methods

Protocol 1: Implementing the iDeepS Workflow iDeepS is a robust method for predicting RBP binding sites and discovering motifs [17] [19].

- Input Encoding:

- Convert RNA sequences into a one-hot encoded matrix (A=[1,0,0,0], C=[0,1,0,0], G=[0,0,1,0], U=[0,0,0,1]).

- Predict the RNA secondary structure from the sequence using a tool like RNAfold. Encode the structural states (e.g., paired or unpaired) similarly using one-hot encoding.

- Concatenate the sequence and structure matrices to form a unified input.

- Model Architecture:

- Feature Learning: Apply convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with multiple filters to the input. These filters scan the sequence and structure to learn local motifs.

- Dependency Modeling: Feed the CNN outputs into a Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BLSTM) network. This layer captures long-range dependencies and interactions between the learned sequence and structure motifs.

- Classification: The final representations are passed through a fully connected layer with a sigmoid activation function to predict the probability of a binding site.

- Motif Extraction: The weights of the trained CNN filters can be converted into Position Weight Matrices (PWMs) to visualize the inferred sequence and structure motifs.

Protocol 2: Hyperparameter Optimization with Bayesian Methods A study highlights the effectiveness of Bayesian Optimizer for tuning CNN models on CLIP-Seq data [6].

- Define Search Space: Establish the range of values for key hyperparameters:

- Learning Rate: Log-uniform distribution between (1e-5) and (1e-2).

- Batch Size: Categorical values from [32, 64, 128, 256].

- Number of CNN Filters: Integer values from 32 to 512.

- Dropout Rate: Uniform distribution between 0.1 and 0.7.

- Select Optimization Algorithm: Choose a Bayesian Optimization library (e.g., scikit-optimize, BayesianOptimization).

- Run Optimization Loop: For a fixed number of iterations (e.g., 50), the algorithm will:

- Select a new set of hyperparameters based on a probabilistic model.

- Train a CNN model with these parameters.

- Evaluate the model on a validation set (e.g., using AUC).

- Update the probabilistic model with the result to inform the next selection.

- Final Evaluation: Train your final model using the best-found hyperparameters and evaluate it on a held-out test set.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Resource | Function in RBP Research |

|---|---|

| CLIP-seq Dataset (e.g., RBP-24, RBP-31) | Provides experimentally verified in vivo binding sites for training and benchmarking predictive models [6] [19] [18]. |

| Secondary Structure Prediction Tool (e.g., RNAfold, RNAShapes) | Computes the secondary structure profile from RNA sequence, which is a critical input feature for structure-aware models [18]. |

| One-Hot Encoding | A fundamental preprocessing step that converts categorical sequence and structure data into a numerical matrix suitable for deep learning models [17] [19]. |

| k-mer Embeddings | An alternative to one-hot encoding that represents short sequence fragments as dense vectors, capturing latent semantic relationships between k-mers and often improving model performance [18]. |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | The core component of many models, used to automatically scan the input RNA data and detect local, informative sequence and structure patterns (motifs) [17] [6]. |

| Bidirectional LSTM (BLSTM) | A type of recurrent neural network added after CNNs to model the long-range context and dependencies between the motifs identified by the convolutions [17] [18]. |

Workflow Diagram: Integrating Sequence & Structure in a CNN-BLSTM Model

The diagram below illustrates the architecture of a hybrid CNN-BLSTM model for RBP binding site prediction.

Optimization Diagram: Hyperparameter Tuning for CNN Models

This diagram outlines the iterative process of hyperparameter optimization to enhance model accuracy.

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common challenges you may encounter when applying Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to biological sequence analysis, particularly in RNA-binding prediction.

| Problem Category | Specific Issue | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Performance | Loss value not improving [21] | Incorrect loss function; Learning rate too high/low; Variables not training. | Use appropriate loss (e.g., cross-entropy); Adjust learning rate; Implement learning rate decay; Check trainable variables. |

| Vanishing/Exploding Gradients [21] [22] | Poor weight initialization; Unsuitable activation functions. | Use better weight initialization (e.g., He/Xavier); Change ReLU to Leaky ReLU or MaxOut; Avoid sigmoid/tanh for deep networks. | |

| Data Handling | Overfitting [21] [22] | Network memorizing training data; Insufficient data. | Implement data augmentation; Add Dropout/L1/L2 regularization; Use Batch Normalization; Apply early stopping; Try a smaller network. |

| Input preprocessing errors [23] | Train/Eval data normalized differently; Incorrect data pipelines. | Ensure consistent preprocessing; Start with simple, in-memory datasets before building complex pipelines. | |

| Implementation & Debugging | Model fails to run [23] | Tensor shape mismatches; Out-of-Memory (OOM) errors. | Use a debugger to step through model creation; Check tensor shapes and data types; Reduce batch size or model dimensions. |

| Cannot overfit a single batch [23] | Implementation bugs; Incorrect loss function gradient. | Systematically debug:- Error goes up: Check for flipped sign in loss/gradient.- Error explodes: Check for numerical issues or high learning rate.- Error oscillates: Lower learning rate, inspect data.- Error plateaus: Increase learning rate, remove regularization, inspect loss/data pipeline. | |

| Variable Training | Variables not updating [21] | Variable not set as trainable; Vanishing gradients; Dead ReLUs. | Ensure variables are in GraphKeys.TRAINABLE_VARIABLES; Revisit weight initialization; Decrease weight decay. |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies from Key Research

This section provides detailed protocols from seminal studies that successfully applied deep learning to RNA-protein binding prediction, serving as templates for your experimental design.

Protocol 1: The iDeep Framework for RNA-Protein Binding Motifs

Objective: Predict RNA-protein binding sites and discover binding motifs by integrating multiple sources of CLIP-seq data [24].

Methodology Details:

- Architecture: A hybrid model combining Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Deep Belief Networks (DBN) [24].

- Core Innovation: Cross-domain knowledge integration. The framework transforms original observed data from different domains (e.g., sequence, structure) into a high-level abstraction feature space. This allows the model to learn shared representations across domains, overcoming the low efficiency of direct data integration [24].

- Input Data: Large-scale CLIP-seq datasets.

- Validation: Performance was evaluated on 31 CLIP-seq datasets. The model achieved an 8% improvement in average AUC by integrating multiple data sources compared to the best single-source predictor, and outperformed other state-of-the-art predictors by 6% [24].

- Outcome: The framework not only predicts binding sites but also uses its CNN component to automatically capture interpretable binding motifs that align with experimentally verified results [24].

Protocol 2: The DeepRKE Model for Binding Site Prediction

Objective: Infer binding sites of RNA-binding proteins using distributed representations of RNA primary sequence and secondary structure [25].

Methodology Details:

- Architecture: A deep neural network combining CNNs and Bidirectional LSTMs (BiLSTM) [25].

- Input Representation:

- Sequence & Structure: RNA primary sequence and secondary structure (predicted by RNAShapes).

- Distributed Representations: Uses the Word2vec (skip-gram) algorithm to learn distributed representations of 3-mers for both sequence and structure, moving beyond traditional one-hot encoding. This captures contextual relationships between k-mers [25].

- Workflow:

- Two separate CNNs process the distributed representations of sequence and structure to extract features.

- The outputs are combined and fed into a third CNN.

- A BiLSTM layer captures long-range dependencies in the data.

- Final predictions are made via fully connected layers with a sigmoid activation [25].

- Validation: Evaluated on RBP-24 and RBP-31 benchmark datasets. DeepRKE achieved a state-of-the-art average AUC of 0.934 on the RBP-24 dataset, outperforming methods like DeepBind and iDeepS [25].

Protocol 3: The NucleicNet Framework for Structural Prediction

Objective: Predict the binding preference of RNA constituents (e.g., bases, backbone) on a protein surface using 3D structural information, without relying on experimental assay data [26].

Methodology Details:

- Architecture: A deep residual network (a type of CNN) trained for a multi-class classification task [26].

- Input Data: Local physicochemical characteristics of a protein structure surface, encoded as high-dimensional feature vectors using the FEATURE program [26].

- Task Formulation: A seven-class classification problem to predict whether a location on the protein surface binds to Phosphate (P), Ribose (R), Adenine (A), Guanine (G), Cytosine (C), Uracil (U), or is a non-site (X) [26].

- Output and Utility:

- Visualization: Surface plots showing top predicted RNA constituents.

- Logo Diagrams: Generates position weight matrices (PWMs) for known binding pockets.

- Scoring Interface: Scores the binding potential of query RNA sequences.

- Validation: NucleicNet accurately recovered interaction modes for challenging RBPs (e.g., Argonaute 2) discovered by structural biology experiments. It also achieved consistency with in vitro (RNAcompete) and in vivo (siRNA Knockdown) assay data without being trained on them [26].

Workflow and Model Architecture Diagrams

CNN-Based Sequence Analysis Workflow

DeepRKE Model Architecture

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational "reagents" and resources essential for building deep learning predictors for RNA-binding protein research.

| Tool / Resource Category | Specific Example(s) | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Databases [27] | Protein Data Bank (PDB), CLIP-seq databases (e.g., from ENCODE) | Source of 3D structural data (e.g., for NucleicNet [26]) and RNA-protein interaction data for training and benchmarking. | Ensure data consistency and correct labeling when creating benchmark datasets from multiple sources [27]. |

| Sequence Encoders [27] [25] | One-hot encoding, k-mer frequency, Word2vec for distributed representations, Language Models (LMs) | Transforms raw sequences into numerical vectors. Distributed representations (e.g., in DeepRKE [25]) capture contextual k-mer relationships, often boosting performance. | Choice of encoder is critical. Distributed representations can capture semantics but may require more data. LMs need large data and hyperparameter tuning [27]. |

| Deep Learning Frameworks [21] [23] | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Keras | Infrastructure for building, training, and evaluating CNN architectures (e.g., ResNet, custom CNNs). | Using off-the-shelf components (e.g., Keras) can reduce bugs. For custom ops, gradient checks are crucial [21] [23]. |

| Model Architectures [28] [29] [25] | Standard CNN, Hybrid CNN-BiLSTM (DeepRKE [25]), Hybrid CNN-DBN (iDeep [24]), Deep Residual Networks (NucleicNet [26]) | The core predictive engine. CNNs extract local patterns; RNNs/LSTMs handle sequential dependencies; DBNs and ResNets enable learning of complex, hierarchical features. | Start with a simple architecture (e.g., basic CNN) to establish a baseline before moving to more complex hybrids [23]. |

| Troubleshooting Tools [21] [23] | TensorBoard, Debuggers (e.g., ipdb, tfdb), Gradient Checking | Visualize training, debug tensor shape mismatches, and verify custom operation implementations to identify and fix model issues. | Logging metrics like loss, accuracy, and learning rate is a fundamental best practice [21]. |

Advanced CNN Architectures for RNA Binding Prediction: Implementation and Design

In the field of computational biology, particularly in RNA binding prediction research, accurately modeling biological sequences requires capturing both local patterns and long-range dependencies. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) excel at identifying local, position-invariant motifs—such as specific nucleotide patterns in RNA sequences—through their filter application and pooling operations [30]. Conversely, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), especially their Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) variants, are specifically designed to handle sequential data and model long-range contextual relationships across a sequence [31] [32]. Hybrid CNN-RNN architectures integrate these complementary strengths, creating powerful models that first extract local features from biological sequences using convolutional layers, then process these features sequentially to understand their contextual relationships [33]. This integration is particularly valuable for predicting RNA-protein binding sites, where both localized binding motifs and their spatial arrangement within the longer nucleotide sequence determine binding specificity [34] [35].

Key Architectures and Implementation

Common Architectural Patterns

Researchers can implement three primary architectures when combining CNNs with RNNs. The choice of architecture depends on the specific nature of the problem and data characteristics [33].

CNN → LSTM (Sequential Feature Extraction): This architecture uses CNN layers as primary feature extractors from input sequences, which are then fed into LSTM layers to model temporal dependencies. The CNN acts as a local feature detector, while the LSTM interprets these features in sequence. This approach is particularly effective when local patterns are informative but their contextual arrangement is critical for prediction [33].

LSTM → CNN (Contextual Feature Enhancement): This model reverses the order, with LSTM layers processing the raw sequence first to capture contextual information, followed by CNN layers that perform feature extraction on these context-enriched representations. This architecture benefits tasks where global sequence context informs local feature detection [33].

Parallel CNN-LSTM (Feature Fusion): In this architecture, CNN and LSTM branches process the input sequence simultaneously but independently. Their outputs are concatenated and passed to a final fully connected layer for prediction. This approach allows the model to learn both spatial and temporal features separately before combining them, often resulting in more robust representations [33].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Performance comparison of different architectures on DNA/RNA binding prediction tasks

| Architecture Type | Key Strengths | Model Interpretability | Training Time | Data Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN-Only (e.g., DeepBind) | Excellent at identifying local motifs | High (learned filters visualize motifs) | Faster | Moderate |

| RNN-Only (e.g., KEGRU) | Captures long-range dependencies effectively | Lower (harder to visualize features) | Moderate | Lower |

| Hybrid CNN-RNN (e.g., DanQ, deepRAM) | Superior accuracy; captures both motifs and context | Moderate (CNN features remain interpretable) | Slower | Higher (with sufficient data) |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Model Architecture Selection

Problem: How do I choose between CNN→LSTM, LSTM→CNN, or parallel architectures for my RNA binding prediction task?

Solution: The optimal architecture depends on your specific data characteristics and research question:

- Use CNN→LSTM when your primary challenge involves identifying local binding motifs (e.g., RNA recognition elements) whose significance depends on their positional context within longer sequences [35]. This architecture has demonstrated strong performance in transcription factor binding site prediction [32].

- Implement LSTM→CNN when you need to understand the broader sequence context before detecting localized features. This approach is less common but can be beneficial for sequences where global structure informs local pattern significance.

- Employ parallel architectures when you have sufficient computational resources and want to leverage both approaches without presupposing their relationship. This can capture complementary features that might be missed in sequential architectures [33].

Experimental Protocol: When comparing architectures, maintain consistent hyperparameter tuning strategies and evaluation metrics. The deepRAM toolkit provides an automated framework for fair comparison of different architectures on biological sequence data [34] [35].

Handling Vanishing Gradients in Deep Hybrid Models

Problem: During training, my hybrid model fails to learn long-range dependencies, with gradients diminishing severely in the LSTM components.

Solution: Vanishing gradients particularly affect models trying to capture long-range dependencies in biological sequences. Several strategies can mitigate this issue:

- Use LSTM or GRU cells instead of vanilla RNNs, as they are specifically designed with gating mechanisms to preserve gradient flow through longer sequences [31].

- Implement gradient clipping to prevent exploding gradients while maintaining healthier gradient flow.

- Apply batch normalization between layers to stabilize activation distributions and improve gradient flow.

- Consider residual connections between layers, allowing gradients to bypass nonlinear transformations.

Experimental Protocol: Monitor gradient norms during training to diagnose vanishing/exploding gradient issues. Tools like TensorBoard can visualize gradient flow through different model components. Start with smaller sequence lengths and gradually increase while observing model performance [30].

Sequence Representation and Encoding

Problem: What encoding strategy should I use for RNA/DNA sequences in hybrid models to maximize performance?

Solution: The representation of biological sequences significantly impacts model performance:

- One-hot encoding represents each nucleotide as a 4-dimensional binary vector (A=[1,0,0,0], C=[0,1,0,0], etc.). This simple approach preserves exact nucleotide identity but doesn't capture sequence semantics [35].

- K-mer embedding uses algorithms like word2vec to represent overlapping k-mers as continuous vectors in a semantic space. This approach captures contextual relationships between sequence fragments and has demonstrated superior performance in tasks like TF binding site prediction [35] [32].

Experimental Protocol: For k-mer embedding, first split sequences into overlapping k-mers using a sliding window (typical k=3-6). Train embedding vectors using word2vec or similar algorithms on your entire sequence dataset before model training. Comparative studies have shown that k-mer embedding with word2vec consistently outperforms one-hot encoding, particularly for RNN-based models [32].

Managing Computational Complexity

Problem: Training hybrid models is computationally expensive, requiring excessive time and memory resources.

Solution: Hybrid CNN-RNN models indeed demand significant computational resources, but several strategies can improve efficiency:

- Implement progressive training, starting with smaller sequence subsets before scaling to full datasets.

- Use hierarchical sampling approaches that focus computational resources on informative sequence regions.

- Apply model pruning and quantization techniques to reduce model size after initial training.

- Utilize distributed training across multiple GPUs to parallelize the computational load.

Experimental Protocol: Profile your model to identify computational bottlenecks. CNN components typically benefit from GPU parallelization, while LSTM components may require memory optimization for long sequences. The deepRAM framework provides optimized implementations specifically for biological sequence analysis [35].

Preventing Overfitting in Data-Scarce Scenarios

Problem: My hybrid model overfits the training data, especially with limited labeled examples of RNA-binding sites.

Solution: Overfitting is a common challenge in biological applications where experimental data may be limited:

- Implement strong regularization techniques including dropout (applied to both CNN and LSTM layers), L2 weight regularization, and early stopping.

- Use data augmentation by generating synthetic sequences through legitimate transformations while preserving biological meaning.

- Apply transfer learning by pre-training on larger related datasets (e.g., general DNA binding data) before fine-tuning on specific RNA-binding tasks.

- Employ multi-task learning to leverage related prediction tasks and improve model generalization.

Experimental Protocol: Systematically evaluate regularization strategies using validation performance. Studies have shown that deeper, more complex architectures provide clear advantages only with sufficient training data, so match model complexity to your dataset size [34] [35].

Experimental Workflow and Visualization

Standardized Experimental Pipeline

Table 2: Essential research reagents and computational tools for hybrid model development

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Datasets | ENCODE ChIP-seq, CLIP-seq experiments | Provide standardized training and testing data for model development and comparison [35] |

| Software Tools | deepRAM, KEGRU, PharmaNet | Offer implemented architectures for biological sequence analysis [34] [35] [32] |

| Sequence Representation | word2vec, k-mer tokenization | Convert biological sequences into numerical representations suitable for deep learning [35] [32] |

| Evaluation Metrics | AUC (Area Under ROC Curve), APS (Average Precision Score) | Quantify model performance for binding site prediction [32] |

Diagram 1: Hybrid CNN-RNN workflow for RNA binding prediction. This architecture first extracts local features using convolutional layers, then models sequence context with recurrent layers.

Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

The application of hybrid CNN-RNN models extends beyond basic binding prediction to transformative applications in pharmaceutical research. In de novo drug design, researchers have successfully used RNNs (particularly LSTMs) to generate novel molecular structures represented as SMILES strings, which can then be optimized for multiple pharmacological properties simultaneously [31]. The PharmaNet framework demonstrates how hybrid architectures can achieve state-of-the-art performance in active molecule prediction, significantly accelerating virtual screening processes [36]. These approaches are particularly valuable for addressing urgent medical needs, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic, where rapid identification of therapeutic candidates is critical [36].

For RNA-targeted drug development, hybrid models facilitate the prediction of complex RNA structural features that influence binding, including G-quadruplex formation and tertiary structure elements [37]. By integrating multiple data modalities—including sequence, structural probing data, and evolutionary information—these models can identify functionally important RNA regions that represent promising therapeutic targets. The multi-objective optimization capabilities of these approaches enable simultaneous optimization of drug candidates for binding affinity, specificity, and pharmacological properties [31] [38].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How much training data is typically required for effective hybrid CNN-RNN models in biological applications?

The data requirements depend on model complexity and task difficulty. For transcription factor binding site prediction, studies have shown that hybrid architectures consistently outperform simpler models when thousands of labeled examples are available [35]. With smaller datasets (fewer than 1000 examples), simpler CNN architectures may be preferable. For novel tasks, consider transfer learning approaches using models pre-trained on larger biological datasets.

Q2: What are the specific advantages of bidirectional RNN components in hybrid architectures?

Bidirectional RNNs (e.g., BiGRU, BiLSTM) process sequences in both forward and reverse directions, allowing the model to capture contextual information from both upstream and downstream sequence elements [32]. This is particularly valuable in biological sequences where regulatory context may depend on both 5' and 3' flanking regions. Studies like KEGRU have demonstrated that bidirectional processing significantly improves transcription factor binding site prediction compared to unidirectional approaches [32].

Q3: How can I interpret and visualize what my hybrid model has learned about RNA binding specificity?

While RNN components are often described as "black boxes," the CNN filters in hybrid architectures typically learn to recognize meaningful sequence motifs that can be visualized similarly to position weight matrices [34] [35]. The deepRAM toolkit includes functionality for motif extraction from trained models, allowing comparison with known binding motifs from databases like JASPAR or CIS-BP [35]. Additionally, attribution methods like integrated gradients can help identify sequence positions most influential to predictions.

Q4: What are the key differences between LSTM and GRU units in biological sequence applications?

Both LSTM and GRU units address the vanishing gradient problem through gating mechanisms, but with different implementations. LSTMs have three gates (input, output, forget) and maintain separate cell and hidden states, while GRUs have two gates (reset, update) and a unified state. GRUs are computationally more efficient and may perform better with smaller datasets, while LSTMs might capture more complex dependencies with sufficient training data [32]. For most biological sequence tasks, the performance difference is often minimal, with GRUs offering a good balance of efficiency and effectiveness.

Q5: How do I balance model complexity with generalization performance for my specific RNA binding prediction task?

Start with a simpler baseline model (e.g., CNN-only) and gradually increase complexity while monitoring validation performance. Use cross-validation with multiple random seeds to account for training instability. Implement strong regularization (dropout, weight decay) and early stopping. If using hybrid architectures, consider beginning with a shallow RNN component (1-2 layers) before exploring deeper architectures. The deepRAM framework provides an automated model selection procedure that can help identify the appropriate architecture complexity for your specific dataset [35].

Why Combine CNN and GCN for RNA Binding Prediction?

The prediction of RNA-protein binding sites is a critical task in bioinformatics, essential for understanding post-transcriptional gene regulation and its implications in diseases ranging from neurodegenerative disorders to various cancers [4] [5]. While Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) excel at capturing local sequence motifs in RNA sequences, Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) effectively model the complex topological features inherent in RNA secondary structures [4] [20]. Parallel architectures that combine these networks leverage their complementary strengths: CNNs extract fine-grained local patterns from sequence data, while GCNs capture global structural context from graph representations of RNA folding [20] [5]. This hybrid approach has demonstrated superior performance in identifying RNA-binding protein (RBP) interactions compared to single-modality models [20] [5].

Fundamental Architecture of a Parallel CNN-GCN Network

In a typical parallel configuration, the network processes RNA sequences through two distinct but simultaneous pathways. The CNN branch utilizes convolutional layers to scan nucleotide sequences for conserved binding motifs and local patterns [5]. Simultaneously, the GCN branch operates on graph-structured data where nodes represent nucleotides and edges represent either sequential connections or base-pairing relationships derived from RNA secondary structure predictions [5]. The features learned by both branches are subsequently fused—either through concatenation, weighted summation, or more sophisticated attention mechanisms—before final classification layers determine binding probability [20] [5]. This parallel design preserves the specialized representational capabilities of each network type while enabling comprehensive feature learning from both sequential and structural data modalities.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Model Design and Implementation

Q1: What are the primary advantages of a parallel CNN-GCN architecture over a serial approach for RNA binding prediction?

A parallel architecture allows both feature extractors to operate independently on the raw input data, preserving modality-specific information that might be lost in serial processing. The CNN stream specializes in detecting local sequence motifs using its translation-invariant filters, while the GCN stream captures long-range interactions and topological dependencies within the RNA secondary structure [39]. Research demonstrates that this parallel configuration more effectively captures both local and global features, leading to improved accuracy in binding site identification compared to serial arrangements [39]. The parallel design also offers implementation flexibility, as both branches can be developed and optimized separately before integration.

Q2: How do I determine the optimal fusion strategy for combining features from CNN and GCN branches?

Feature fusion strategy significantly impacts model performance. Common approaches include:

- Concatenation: Simple channel-wise concatenation of feature vectors from both branches

- Weighted Summation: Applying learned weights to each branch's output before summation

- Attention Mechanisms: Using attention layers to dynamically determine the importance of features from each branch

- Optimization-Driven Fusion: Employing advanced algorithms like Improved Dung Beetle Optimization (IDBO) to adaptively assign fusion weights during inference [5]

Empirical evidence suggests that optimization-driven fusion strategies, such as those used in RMDNet, can enhance robustness and performance by dynamically balancing contributions from different feature types [5]. We recommend implementing multiple fusion strategies and evaluating them through ablation studies to determine the optimal approach for your specific dataset.

Q3: What are the common causes of overfitting in hybrid models, and how can I mitigate them?

Overfitting in hybrid CNN-GCN models typically arises from:

- Limited training data relative to model complexity

- Improper balance between CNN and GCN branches

- Insufficient regularization techniques

Effective mitigation strategies include:

- Implementing Early Stopping: Monitor validation loss and halt training when performance plateaus [20]

- Applying Spatial Dropout: Incorporate dropout layers within both CNN and GCN branches

- Using L2 Regularization: Apply weight decay in convolutional and graph convolutional layers

- Data Augmentation: Artificially expand training data through sequence transformations

- Simplifying Architecture: Reduce model complexity if limited training data is available

The DeepPN framework successfully employed early stopping to prevent overfitting during model training on 24 RBP datasets [20].

Training and Optimization Challenges

Q4: Why does my model exhibit unstable convergence and oscillating loss during training?

Oscillating loss patterns often stem from inappropriate learning rates or gradient instability. We recommend implementing FuzzyAdam, a novel optimizer that integrates fuzzy logic into the adaptive learning framework of standard Adam [4]. Unlike conventional Adam, FuzzyAdam dynamically adjusts learning rates based on fuzzy inference over gradient trends, substantially improving convergence stability [4]. Experimental results demonstrate that FuzzyAdam achieves more stable convergence and reduced false negatives compared to standard optimizers [4]. Additional stabilization techniques include:

- Gradient Clipping: Limit extreme gradient values during backpropagation

- Learning Rate Scheduling: Implement adaptive learning rate reduction based on validation performance

- Batch Normalization: Stabilize activations throughout both network branches

Q5: How can I handle extreme class imbalance in RBP binding site datasets?

Class imbalance is a common challenge in biological datasets. Effective approaches include:

- Strategic Negative Sampling: Generate negative samples from regions without any identified binding peaks within the same transcript [40]

- Loss Function Modification: Implement weighted cross-entropy or focal loss to emphasize minority class learning

- Data Resampling: Apply oversampling of minority classes or undersampling of majority classes

- Ensemble Methods: Combine multiple balanced sub-models to address imbalance

RBPsuite 2.0 successfully employed strategic negative sampling by shuffling positive regions using pybedtools to generate balanced negative examples [40].

Q6: What preprocessing steps are essential for RNA sequence data before input to a parallel CNN-GCN model?

Proper data preprocessing is crucial for model performance:

- Sequence Encoding: Convert RNA sequences to one-hot encoded matrices (A=[1,0,0,0], C=[0,1,0,0], G=[0,0,1,0], U=[0,0,0,1]) [5]

- Length Normalization: Implement sliding window strategies with padding (using 'N' nucleotides) to handle variable-length sequences [5]

- Secondary Structure Prediction: Use RNAfold or similar tools to generate dot-bracket notations of RNA secondary structures [5]

- Graph Construction: Convert secondary structures to graph format where nodes represent nucleotides and edges indicate sequential adjacency or base pairing [5]

- Data Partitioning: Randomly divide datasets into training and test sets, ensuring representative distribution of classes [20]

The RMDNet framework employed a multi-window ensemble strategy, training models on nine different window sizes from 101 to 501 nucleotides to enhance robustness [5].

Performance Comparison Tables

Quantitative Performance of CNN-GCN Architectures on Benchmark Datasets

Table 1: Performance comparison of parallel CNN-GCN models on RNA-protein binding site prediction tasks

| Model Name | Architecture | Dataset | Accuracy | F1-Score | Precision | Recall | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FuzzyAdam-CNN-GCN [4] | CNN-GCN with Fuzzy Logic Optimizer | 997 RNA sequences | 98.39% | 98.39% | 98.42% | 98.39% | - |

| DeepPN [20] | CNN-ChebNet Parallel Network | RBP-24 (24 datasets) | - | - | - | - | Superior on most datasets |

| RMDNet [5] | Multi-branch CNN+Transformer+ResNet with GNN | RBP-24 | Outperformed GraphProt, DeepRKE, DeepDW | - | - | - | - |

| RBPsuite 2.0 [40] | iDeepS (CNN+LSTM) | 351 RBPs across 7 species | - | - | - | - | High accuracy on circular RNAs |

Computational Requirements and Efficiency Metrics

Table 2: Computational performance of GCN accelerators and optimization frameworks

| System/Accelerator | Platform | Precision | Speedup vs CPU | Speedup vs GPU | Energy Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QEGCN [41] | FPGA | 8-bit quantized | 1009× | 216× | 2358× better than GPU |

| FuzzyAdam [4] | Software Optimization | FP32 | - | - | More stable convergence |

| RMDNet with IDBO [5] | Software Framework | FP32 | - | - | Enhanced robustness |

Experimental Protocols

Standard Implementation Protocol for Parallel CNN-GCN Architecture

Objective: Implement a parallel CNN-GCN network for predicting RNA-protein binding sites using sequence and structural information.

Materials and Reagents:

- RNA sequences in FASTA format

- CLIP-seq or eCLIP data for binding site annotations

- Computational resources (GPU recommended for training)

- RNA secondary structure prediction tool (e.g., RNAfold)

Methodology:

Data Preprocessing:

- Encode RNA sequences using one-hot encoding (A:[1,0,0,0], C:[0,1,0,0], G:[0,0,1,0], U:[0,0,0,1]) [5]

- For sequences containing ambiguous bases, use [0.25,0.25,0.25,0.25] for 'N' nucleotides [5]

- Process variable-length sequences using a sliding window approach with multiple sizes (101-501 nt) [5]

- Pad shorter sequences with 'N' nucleotides to maintain consistent input dimensions

Graph Construction:

- Predict secondary structures using RNAfold to generate dot-bracket notation [5]

- Construct graphs where nodes represent nucleotides and edges represent either:

- Sequential connections between adjacent nucleotides

- Base-pairing interactions from secondary structure

- Represent node features using one-hot encoding or learned embeddings

Model Architecture:

- CNN Branch: Implement a 2-layer CNN with ReLU activation and max pooling to extract local sequence features [20]

- GCN Branch: Implement a 2-layer ChebNet or Graph Convolutional Network to process structural graphs [20]

- Fusion Layer: Concatenate features from both branches followed by fully connected layers

- Output Layer: Use sigmoid activation for binary classification (binding vs non-binding)

Training Configuration:

Validation and Interpretation:

Troubleshooting Tips:

- For unstable training: Reduce learning rate, implement gradient clipping, or switch to FuzzyAdam optimizer [4]

- For overfitting: Increase dropout rate, add L2 regularization, or expand training data through augmentation

- For poor performance: Experiment with different fusion strategies or incorporate additional feature types

Benchmarking and Validation Protocol

Objective: Evaluate model performance against established benchmarks and biological validations.

Validation Methodology:

Cross-Dataset Validation:

Ablation Studies:

- Evaluate contribution of individual components by removing CNN or GCN branches

- Assess impact of different fusion strategies on final performance

- Test various optimization algorithms (Adam, RMSProp, FuzzyAdam)

Biological Validation:

- Extract candidate binding motifs from first-layer CNN kernels [5]

- Compare identified motifs with experimentally validated RBP motifs from databases

- Perform case studies on specific disease-relevant RBPs (e.g., YTHDF1 in liver cancer) [5]

- Validate predictions with RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) experiments where feasible [40]

Architectural Diagrams and Workflows

Parallel CNN-GCN Architecture for RNA Binding Site Prediction

Data Preprocessing and Model Training Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential computational tools and resources for parallel CNN-GCN research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in RNA Binding Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBPsuite 2.0 [40] | Web Server | RBP binding site prediction | Benchmarking model performance against established tools |

| POSTAR3 [40] | Database | RBP binding sites from CLIP-seq experiments | Training data source and validation benchmark |

| RNAfold [5] | Software Tool | RNA secondary structure prediction | Generating structural graphs for GCN input |

| PyTorch Geometric [20] | Deep Learning Library | Graph neural network implementation | Building GCN branches of parallel architectures |

| DGL [41] | Deep Learning Library | Graph neural network framework | Alternative GCN implementation platform |

| QEGCN [41] | FPGA Accelerator | Hardware acceleration for GCNs | Deploying optimized models for high-throughput prediction |

| FuzzyAdam [4] | Optimization Algorithm | Enhanced training optimizer | Stabilizing convergence in hybrid model training |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My multi-modal CNN for RBP binding site prediction is not converging. The validation loss is unstable. What could be the issue? Instability during training often stems from improper learning rate settings or gradient issues. Use the Adam optimizer, which adapts the learning rate for each parameter, helping to stabilize training. Ensure you have implemented gradient clipping to handle exploding gradients, a common problem in deep networks. Also, verify that your input data (sequence and structure representations) are properly normalized [42].

Q2: The model performs well on training data but poorly on validation data for my lncRNA identification task. How can I address this overfitting? Overfitting indicates your model is memorizing the training data rather than learning generalizable patterns. Implement the following techniques:

- Dropout: Randomly disable neurons during training to force the network to learn redundant representations [42].

- L1/L2 Regularization: Add penalty terms to the loss function based on weight sizes to constrain model complexity [42].

- Data Augmentation: Artificially expand your training data using techniques appropriate for biological sequences [42].

- Early Stopping: Monitor validation performance and halt training when it plateaus [42].

Q3: How can I effectively integrate RNA secondary structure information with sequence data in a single model? The most effective approach is to use separate convolutional pathways for each modality before combining them. Implement a architecture that:

- Uses one convolution branch for one-hot encoded sequence information

- Uses a separate branch for structure probability matrices (which represent multiple possible secondary structures)

- Combines the outputs from both branches in later layers to detect complex combined motifs [43] This approach has demonstrated significant performance improvements, particularly for RBPs like ALKBH5 [43].

Q4: What are the advantages of using multi-sized convolution filters in RBP binding prediction? Traditional methods use fixed filter sizes, but RBP binding sites vary from 25-75 base pairs. Multi-sized filters capture motifs of different lengths simultaneously, which led to a 17% average relative error reduction in benchmark tests. They help detect short, medium, and long sequence-structure motifs that are crucial for accurate binding site identification [43].

Q5: How important is weight initialization for training deep multi-modal networks? Proper weight initialization greatly impacts how quickly and effectively your network trains. Poor initialization can lead to vanishing or exploding gradients, making learning difficult. Use initialization strategies specific to your activation functions, and consider using batch normalization layers to stabilize training by normalizing layer inputs across each mini-batch [42].

Performance Comparison of Multi-Modal Methods

The table below summarizes quantitative performance of different methods on RBP-24 dataset, measured by Area Under Curve (AUC) of Receiver-Operating Characteristics:

| Method | Average AUC | RBPs Outperformed | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| mmCNN (Proposed) | 0.920 | N/A | Multi-modal features, multi-sized filters, structure probability matrix [43] |

| GraphProt | 0.888 | 20 out of 24 | Sequence + hypergraph structure representation, SVM [43] |

| Deepnet-rbp (DBN+) | 0.902 | 15 out of 24 | Sequence + structure + tertiary structure, deep belief network [43] |

| iDeepE | Not reported | Not reported | Sequence information only [43] |

Table 1: Benchmarking results on RBP-24 dataset showing performance advantages of multi-modal approaches.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Multi-Modal CNN for RBP Binding Site Prediction

This protocol outlines the procedure for building and training the mmCNN architecture described in [43] for predicting RNA-binding protein binding sites.

Materials:

- CLIP-seq datasets (e.g., RBP-24 dataset from GraphProt)

- RNA sequence data in FASTA format

- Computational tools for RNA secondary structure prediction (e.g., RNAshapes)

Method:

- Data Preparation:

- Extract positive and negative sequences from CLIP-seq data

- Convert RNA sequences to one-hot encoded representation (4 channels for A,C,G,U)

- Calculate structure probability matrices using tools like RNAshapes to represent multiple possible secondary structures

Network Architecture:

- Implement two separate convolution branches:

- Sequence branch: one-hot encoded RNA sequences

- Structure branch: structure probability matrices

- Use multi-sized convolution filters (e.g., 3x3, 5x5, 7x7) in each branch to capture motifs of different lengths

- Apply ReLU activation after each convolutional layer

- Add max pooling layers to reduce spatial dimensions

- Stack outputs from both branches and feed into additional convolution layers for combined feature extraction

- Use fully connected layers with dropout regularization before final classification

- Implement two separate convolution branches:

Training:

- Use binary cross-entropy loss function

- Optimize with Adam optimizer with learning rate 0.001

- Implement 10-fold cross-validation for performance evaluation

- Apply early stopping based on validation performance

Protocol 2: Feature Extraction for lncRNA Identification Using LncFinder

This protocol describes the comprehensive feature extraction process for long non-coding RNA identification using the LncFinder platform [44].

Materials:

- Transcript sequences in FASTA format

- LncFinder software (available as R package or web server)

Method:

- Sequence Intrinsic Composition Features:

- Calculate k-mer frequencies (typically k=1 to 5)

- Compute ORF-related features including length and coverage

- Determine Fickett TESTCODE score for coding potential

Secondary Structure Features:

- Predict secondary structures using RNA folding algorithms

- Extract multi-scale structural features including stem-loop proportions

- Calculate minimum free energy of structures

Physicochemical Property Features:

- Compute electron-ion interaction pseudopotential (EIIP) values

- Calculate nucleosome positioning preferences

- Determine stacking energy features

Model Building and Evaluation:

- Integrate all feature types into a unified representation

- Train machine learning classifiers (SVM, Random Forest, or Deep Neural Networks)

- Evaluate performance using cross-validation on species-specific data

- Compare against existing tools like CPAT, CNCI, and PLEK

Workflow Visualization

Multi-Modal CNN for RBP Binding Prediction

Diagram 1: Multi-modal CNN workflow for RBP binding prediction integrating sequence and structure information.

Comprehensive lncRNA Identification Workflow

Diagram 2: Comprehensive lncRNA identification workflow integrating multiple feature types.

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Computational Tools for RNA Bioinformatics

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| GraphProt | RBP binding site prediction | Benchmark comparison, hypergraph representation of RNA structure [43] |

| LncFinder | lncRNA identification platform | Integrated feature extraction, species-specific model building [44] |

| RNAshapes | RNA secondary structure prediction | Generate structure probability matrices for mmCNN training [43] |

| CPAT | Coding potential assessment | Comparative tool for lncRNA identification, uses logistic regression [44] |

| Deepnet-rbp | RBP binding prediction with DBN | Tertiary structure integration, performance benchmarking [43] |

| DIRECT | RNA contact prediction | Incorporates structural patterns using Restricted Boltzmann Machine [45] |

| QCNN | Quantum convolutional networks | Alternative architecture for complex data analysis [46] |

Table 2: Essential computational tools and resources for RNA bioinformatics research.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the fundamental difference between one-hot encoding and k-mer embedding?

One-hot encoding represents each category (e.g., a nucleotide or a k-mer) as a sparse, high-dimensional binary vector where only one element is "1" and the rest are "0". This method treats all categories as independent and equidistant, with no inherent notion of similarity between them [47]. In contrast, k-mer embedding maps categories into dense, lower-dimensional vectors of real numbers. These vectors are learned through training so that k-mers with similar contexts or functions have similar vector representations, thereby capturing semantic relationships and biological similarities [25] [47].

2. When should I choose one-hot encoding over k-mer embeddings for my model?