Optimizing RNA-seq Library Preparation: A Comprehensive Guide to Reducing Bias and Enhancing Data Fidelity

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and drug development professionals on minimizing bias in RNA-seq library preparation.

Optimizing RNA-seq Library Preparation: A Comprehensive Guide to Reducing Bias and Enhancing Data Fidelity

Abstract

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and drug development professionals on minimizing bias in RNA-seq library preparation. Covering the entire workflow from sample handling to data validation, it details the foundational sources of technical bias, strategic methodological choices for different sample types, practical troubleshooting and optimization protocols, and rigorous frameworks for experimental validation. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging technologies, this resource empowers scientists to produce more reliable and reproducible transcriptome data, thereby strengthening downstream analyses and biological conclusions.

Understanding the Sources of Bias in RNA-seq Workflows

FAQs: Understanding and Mitigating Bias in RNA-seq

Q1: What are the most common sources of technical bias in RNA-seq data? Technical biases can arise at multiple points in the RNA-seq workflow. A frequent and impactful source is sample-specific gene length bias, where sets of particularly short or long genes repeatedly show changes in expression level that are not biologically real but technical artifacts. This bias can lead to the false identification of specific biological functions, such as ribosome-related functions (often encoded by short genes) or extracellular matrix functions (often encoded by long genes), as being significantly altered in an experiment [1]. Other common sources include RNA degradation and contamination during extraction, inadequate experimental design leading to batch effects, and bioinformatic missteps in data normalization and analysis [2] [3] [4].

Q2: How can I tell if my RNA-seq data is affected by gene length bias? You can identify this bias by analyzing the relationship between gene length and apparent differential expression. If you observe a pattern where gene sets of consistently short or long length appear to be differentially expressed when comparing replicate samples from the same biological condition, this strongly indicates a technical length bias. Tools like conditional quantile normalization (cqn) can be applied to correct this sample-specific length effect [1].

Q3: My downstream applications (e.g., PCR) are failing after RNA extraction. What could be wrong? This is often a symptom of low purity RNA. Contaminants carried over from the extraction process can inhibit enzymatic reactions. Common causes and solutions include:

- Protein contamination (low A260/280): Ensure complete sample digestion and consider using a Proteinase K step [2].

- Residual salts or guanidine (low A260/230): Ensure wash steps are performed thoroughly. After the final wash, centrifuge the column for an additional 2 minutes and take care not to contact the flow-through when handling the column [2].

- Polysaccharide or fat contamination: Decrease the starting sample volume and increase the number of 75% ethanol rinses [5].

Q4: How does library preparation choice influence bias in my RNA-seq experiment? The choice between full-length and 3' mRNA-seq methods involves a trade-off between breadth of information and throughput/sensitivity. Full-length methods are essential for discovering novel transcripts, alternative splicing, and isoform-level changes, but they are more susceptible to biases from RNA degradation and can be less efficient for high-throughput screens [3] [6]. In contrast, 3' mRNA-seq methods (like DRUG-seq or BRB-seq) are highly multiplexed, more robust for degraded samples (e.g., RIN < 8), and require fewer reads per sample, making them excellent for large-scale drug screens. However, they provide no information on splicing or transcript variants [3].

Q5: How can I design my RNA-seq experiment to minimize bias from the start? A robust experimental design is your primary defense against bias. Key considerations include:

- Biological Replicates: A minimum of three biological replicates per condition is generally advised, with four to eight being ideal for capturing true biological variability [3].

- Controls: Include appropriate untreated or vehicle controls. Use synthetic spike-in RNAs (e.g., SIRVs, ERCC) to monitor technical performance and enable consistent quantification across samples [3].

- Batch Effects: Plan your plate layout and processing schedule to minimize confounding technical variation with biological conditions. A well-designed layout also facilitates computational correction of any remaining batch effects [3].

- Pilot Testing: Run a small-scale pilot experiment to optimize protocols and validate conditions before committing to a large, costly study [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

RNA Extraction & Purification

| Problem | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Yield | Incomplete homogenization or lysis [5]. | Increase homogenization time; centrifuge to pellet debris after lysis and use only the supernatant [2]. |

| Too much starting material [2]. | Reduce input amount to match kit specifications; this prevents column overloading and ensures sufficient buffer action. | |

| RNA is degraded [2]. | Flash-freeze samples or use DNA/RNA protection reagent; ensure a RNase-free work environment. | |

| RNA Degradation | RNase contamination [5]. | Use RNase-free tips, tubes, and reagents; wear gloves; use a dedicated clean area. |

| Improper sample storage or repeated freeze-thaw cycles [2]. | Store samples at -80°C in single-use aliquots. | |

| DNA Contamination | Genomic DNA not effectively removed [2]. | Perform an on-column or in-tube DNase I digestion step during extraction. |

| Low Purity (Inhibitors) | Residual protein or salts [2]. | Ensure complete protein digestion and thorough wash steps; re-spin the column after final wash. |

Library Prep & Bioinformatics

| Problem | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Length Bias | Technical bias in data generation and flawed statistical analysis [1]. | Apply bias-correction algorithms like conditional quantile normalization (cqn) to decouple gene length from differential expression signals. |

| Poor Sequencing Library | Input RNA is degraded or impure [5]. | Always check RNA quality (e.g., RIN) before library prep; re-extract if necessary. |

| Inefficient cDNA synthesis or adapter ligation, especially for short RNAs [7]. | Use advanced methods like Ordered Two-Template Relay (OTTR), which minimizes bias and improves end-precision for capturing short or fragmented RNAs. | |

| False Positive DEGs | Inadequate normalization or failure to account for batch effects [4]. | Use robust normalization methods (e.g., TMM for bulk RNA-seq); include batch as a covariate in your statistical model. |

| Small sample sizes leading to underpowered statistics [4]. | Use differential analysis methods robust for small samples (e.g., dearseq); increase biological replicates. |

Key Experimental Protocols for Bias Reduction

Protocol: Correcting for Gene Length Bias

Objective: To remove technical bias coupled to gene length that can lead to false positive results in Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) [1].

- Data Input: Start with a gene expression matrix (raw counts or normalized values) and a corresponding file of gene lengths.

- Bias Assessment: Generate a scatter plot of gene expression change (e.g., log2 fold change) versus gene length. A non-random pattern (e.g., a lowess line that is not flat) indicates length bias.

- Apply Correction: Use the conditional quantile normalization (cqn) package in R. The function models the effect of gene length and GC content on expression and removes this technical effect.

- Validation: Re-run the differential expression and GSEA analysis on the cqn-corrected data. A successful correction will show that previously enriched gene sets tied to short or long genes are no longer significant, preserving only the biologically genuine signals [1].

Protocol: A Robust RNA-seq Data Analysis Pipeline

Objective: To outline a standardized bioinformatics workflow that ensures reliable identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from raw sequencing data [4].

- Quality Control (QC): Use FastQC to assess the quality of raw sequencing reads and identify potential issues.

- Trimming & Filtering: Use Trimmomatic to remove low-quality bases and adapter sequences.

- Quantification: Use an alignment-free tool like Salmon to estimate transcript abundance. This step is fast and accurate.

- Normalization: Apply the Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) method (from the

edgeRpackage) to correct for compositional differences between samples. - Batch Effect Correction: Examine for and correct any batch effects using methods like ComBat if necessary.

- Differential Expression Analysis: Choose a robust statistical method suited to your experimental design. Benchmarking suggests

dearseqfor complex designs or small samples, andvoom-limma,edgeR, orDESeq2for standard bulk RNA-seq [4].

The workflow for this pipeline is summarized in the following diagram:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Monarch DNA/RNA Protection Reagent | Maintains RNA integrity in samples during storage, preventing degradation before extraction [2]. |

| On-column DNase I | Digests and removes genomic DNA contamination during RNA purification, ensuring pure RNA for downstream applications [2]. |

| SIRV/ERCC Spike-in RNA Controls | Synthetic RNA mixes added to samples before library prep. They act as internal standards for normalization, sensitivity assessment, and technical performance monitoring [3]. |

| Proteinase K | An enzyme used to digest proteins and nucleases during cell lysis, improving RNA yield and purity by breaking down cellular structures and inactivating RNases [2]. |

| Ordered Two-Template Relay (OTTR) | A reverse transcription method that provides improved precision and minimized bias for sequencing short or fragmented RNAs (e.g., miRNA, tRNA fragments) [7]. |

| CapTrap | A technology used in long-read RNA-seq to enrich for full-length, capped mRNA molecules, enabling more accurate transcriptome annotation [6]. |

Optimizing mRNA Design: A Data-Driven Approach

While not a direct source of bias in a standard RNA-seq pipeline, the principles of data-driven optimization are crucial for related fields like mRNA therapeutic development. The RiboDecode framework demonstrates a paradigm shift from rule-based to learning-based sequence design.

RiboDecode integrates a translation prediction model (trained on large-scale Ribo-seq data), an mRNA stability (Minimum Free Energy - MFE) model, and a codon optimizer. It uses gradient ascent to explore a vast sequence space and generate mRNA codon sequences that maximize translation and/or stability for enhanced therapeutic efficacy [8]. This approach has shown substantial improvements in protein expression in vitro and much stronger immune responses or dose-efficiency in vivo compared to previous methods [8]. The following diagram illustrates this generative optimization process.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the single most critical factor for successful RNA preservation? The immediate stabilization of RNA at the point of sample collection is paramount. RNA molecules are naturally susceptible to rapid degradation by ribonucleases (RNases), and transcriptional processes can continue post-collection, altering the true transcriptional landscape. Effective preservation must immediately inhibit both degradative processes and ongoing transcription to maintain accurate gene expression profiles [9].

2. My RNA yields from plant tissues are consistently low. What could be the cause and solution? Low RNA yields from plant tissues are often due to high levels of interfering compounds like polysaccharides, polyphenols, and secondary metabolites. These compounds can bind to or co-precipitate with RNA. Incorporating a sorbitol pre-wash step can significantly improve outcomes. For grape berry skins, this step increased RNA yield from 3.3 ng/µL to 20.8 ng/µL when using a commercial kit and improved the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) from 1.2 to 7.2 [10]. Similarly, for challenging banana tissues (Musa spp.), a modified SDS-based RNA extraction buffer effectively recovered high-quality RNA (2.92 to 6.30 µg/100 mg fresh weight) with high RNA integrity (RNA IQ 7.8–9.9) [11].

3. How do I choose between snap-freezing and chemical preservatives like RNAlater? The choice involves balancing logistical constraints and required RNA quality. RNAlater has demonstrated superior performance in direct comparisons. For human dental pulp tissue, RNAlater storage provided an 11.5-fold higher RNA yield compared to snap-freezing in liquid nitrogen and achieved optimal RNA quality in 75% of cases versus only 33% for snap-frozen samples [9]. RNAlater is often more practical in clinical settings where immediate access to liquid nitrogen is limited.

4. My RNA-seq data shows high ribosomal RNA (rRNA) contamination. How can I improve mRNA enrichment? rRNA contamination is a common issue, as it can constitute over 80% of total RNA. For polyadenylated transcript enrichment, standard one-round of oligo(dT) purification may be insufficient, potentially leaving ~50% rRNA content. Optimization is key:

- Increase the beads-to-RNA ratio: Raising the ratio from 13.3:1 to 50:1 can reduce rRNA content to about 20% [12].

- Perform two rounds of enrichment: This can further reduce rRNA content to less than 10% [12].

- Verify the efficiency of enrichment methods (e.g., capillary electrophoresis) before proceeding to costly sequencing [12].

5. Are commercial RNA extraction kits reliable for all sample types? Commercial kits provide convenience but their performance varies significantly depending on the sample type. For standard cell lines, many kits perform well [13]. However, for recalcitrant tissues (e.g., grape berry skins, woody plants, FFPE samples), they often require protocol modifications or may be ineffective [10]. Systematic comparisons of seven FFPE RNA extraction kits showed notable differences in the quantity and quality of recovered RNA, with some kits consistently outperforming others [14]. Always validate kit performance for your specific sample.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor RNA Integrity and Low RIN/RQS Values

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Delayed or Inefficient Preservation.

- Solution: Minimize the time between sample dissection and preservation. For tissues high in RNases like dental pulp, complete preservation steps within 90 seconds [9]. Validate that your preservation method (snap-freezing or chemical) immediately halts RNase activity.

- Cause: Incomplete Homogenization or Lysis.

- Solution: For fibrous tissues (e.g., dental pulp, plant matter), ensure thorough homogenization. Use optimized, tissue-specific lysis buffers. The modified SDS-based buffer for banana tissues included LiCl precipitation to enhance yield and purity [11]. For microlepidopterans, protocol optimizations like extended, agitated incubation during protein digestion were crucial [15].

- Cause: Co-purification of Contaminants.

- Solution: Incorporate additional washing steps. The sorbitol pre-wash selectively removes polyphenols and polysaccharides from grape skins without precipitating RNA [10]. For DNA contamination, an additional DNase treatment can be incorporated, which has been shown to significantly reduce genomic DNA levels and intergenic read alignment in RNA-seq [16].

Problem: Low RNA Yield

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Suboptimal Preservation Method.

- Solution: Re-evaluate your preservation choice. If using snap-freezing, ensure tissue pieces are small enough for rapid freezing. Consider switching to a chemical preservative if yield is consistently low. See [9] for a quantitative comparison.

- Cause: Inefficient Elution or Precipitation.

- Solution: For column-based kits, ensure elution buffer is applied to the center of the membrane and incubate at room temperature as per optimized protocols [15]. For precipitation methods, ensure correct salt and alcohol concentrations and sufficient precipitation time.

Problem: Inconsistent RNA-seq Results (High Bias/Background)

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: rRNA Contamination.

- Solution: Optimize your mRNA enrichment as described in FAQ #4. Consider using rRNA depletion kits instead of poly(A) selection, especially if studying non-polyadenylated RNAs [12].

- Cause: gDNA Contamination.

- Solution: Implement a robust DNase digestion step. Studies have shown that an additional DNase treatment can be necessary to reduce intergenic read alignment in sensitive RNA-seq applications [16].

- Cause: Pervasive Sequencing Biases.

- Solution: Employ advanced bioinformatic tools for bias mitigation. The Gaussian Self-Benchmarking (GSB) framework leverages the natural GC-content distribution of transcripts to correct for multiple co-existing biases (GC bias, fragmentation bias, library prep bias) simultaneously, leading to more reliable data [13].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: RNA Preservation with RNAlater for Human Tissues

Methodology (as used for dental pulp tissue) [9]:

- Immediately after dissection, transfer tissue to a sterile Petri dish.

- Wash briefly (10-15 seconds) in sterile DMEM solution using RNase-free vessels.

- Transfer to a new Petri dish containing RNAlater solution.

- Rapidly section tissue into fine fragments (<3 mm) within 90 seconds to prevent degradation.

- Store samples in RNAlater at the recommended temperature.

Protocol 2: Sorbitol Pre-Wash for RNA Extraction from Polyphenol-Rich Tissues

Methodology (as used for grape berry skins) [10]:

- Grind frozen tissue to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen.

- Add 10 mL of pre-chilled Sorbitol Wash Buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 100 mM LiCl, 50 mM EDTA, 2% SDS, 1% PVP-40, 0.5% sorbitol) per gram of tissue.

- Vortex vigorously and incubate on ice for 15 minutes.

- Centrifuge at 13,000g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- Discard the supernatant, which contains the solubilized contaminants.

- Proceed with your standard RNA extraction protocol (e.g., commercial kit or phenol-chloroform) on the resulting pellet.

Protocol 3: Modified SDS-Based RNA Extraction for Challenging Plant Tissues

Methodology (as used for Musa spp.) [11]:

- Extraction Buffer: 2% SDS, 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM EDTA, 500 mM NaCl, 2% PVP.

- Procedure:

- Homogenize 100 mg tissue in 1 mL of pre-warmed (65°C) extraction buffer.

- Incubate at 65°C for 20 minutes with occasional mixing.

- Add 0.2 volumes of chloroform, mix, and centrifuge.

- Precipitate the RNA from the aqueous phase with an equal volume of 4M LiCl at -20°C for 30+ minutes.

- Centrifuge, wash the pellet with 70% ethanol, and resuspend in RNase-free water.

Comparative Performance of Preservation Methods

Table 1: Quantitative comparison of RNA preservation methods from human dental pulp tissue (n=36). Data adapted from [9].

| Preservation Method | Average Yield (ng/µL) | Average RIN | Samples with Optimal Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNAlater Storage | 4,425.92 ± 2,299.78 | 6.0 ± 2.07 | 75% |

| RNAiso Plus | Not explicitly stated (1.8x lower than RNAlater) | Not explicitly stated | Not explicitly stated |

| Snap Freezing | 384.25 ± 160.82 | 3.34 ± 2.87 | 33% |

Performance of Commercial Kits for FFPE RNA Extraction

Table 2: Summary of findings from a systematic comparison of seven commercial FFPE RNA extraction kits across three tissue types (Tonsil, Appendix, Lymph Node). Data adapted from [14].

| Kit Performance Group | Key Finding | Notable Example |

|---|---|---|

| Higher Quantity | One kit provided the maximum RNA recovery for 7 out of 9 samples. | ReliaPrep FFPE Total RNA Miniprep (Promega) |

| Better Quality | Three kits performed better in terms of RQS and DV200 values. | Roche Kit |

| Best Overall Ratio | One kit yielded the best combination of both quantity and quality. | ReliaPrep FFPE Total RNA Miniprep (Promega) |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential reagents and kits for RNA preservation and extraction, with specific examples from recent studies.

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNAlater Stabilization Solution | Chemical preservation of RNA in tissues; inhibits RNases. | Optimal for human dental pulp and other clinical tissues. | [9] |

| RNAiso Plus / TRIzol | Monophasic lysis reagent for simultaneous dissociation of cells and inactivation of RNases. | Standard for cell lines (HEK293T); base for plant protocol modifications. | [11] [13] |

| Sorbitol Wash Buffer | Pre-wash to remove polysaccharides and polyphenols without precipitating RNA. | Critical for high-quality RNA from grape berry skins and other polyphenol-rich plants. | [10] |

| Oligo(dT)25 Magnetic Beads | Selection and enrichment of polyadenylated mRNA from total RNA. | Requires optimization of beads-to-RNA ratio for effective rRNA depletion in yeast. | [12] |

| Ribo-off rRNA Depletion Kit | Removal of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) from total RNA using probes. | Used for profiling non-rRNA molecules in human samples. | [13] |

| CTAB Buffer | Lysis buffer effective for disrupting cells with tough walls and removing polysaccharides. | Used in optimized protocols for plants and insects (microlepidopterans). | [11] [15] |

| Poly(A)Purist MAG Kit | Magnetic bead-based selection of polyadenylated RNA. | Compared for mRNA enrichment efficiency in yeast. | [12] |

| VAHTS Universal V8 RNA-seq Kit | Library preparation for next-generation sequencing. | Used for standardized RNA-seq library construction from various samples. | [13] |

Workflow Diagrams

Sample Preservation and RNA Extraction Workflow

Troubleshooting Common RNA Extraction Challenges

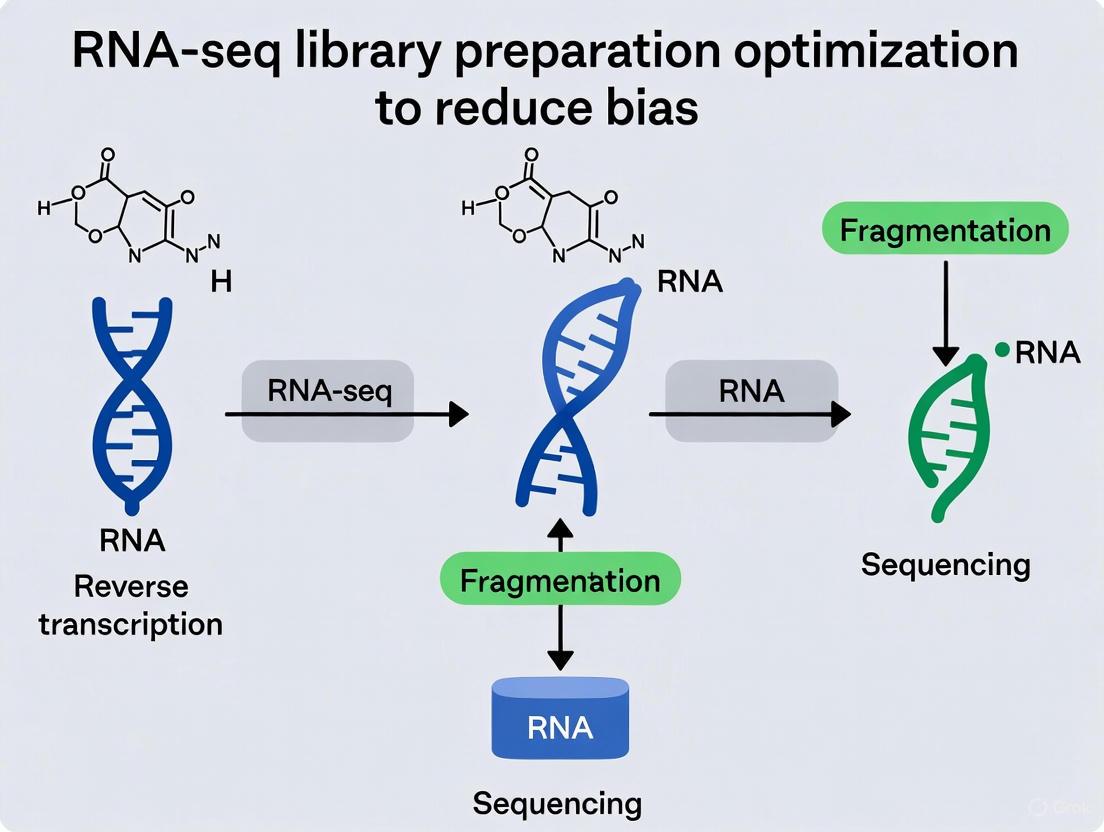

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), the journey from raw nucleic acids to a sequenced library is a potential minefield of technical bias. Library construction has been identified as a stage where almost every procedural step can introduce significant deviations, compromising data quality and leading to erroneous biological interpretations [17] [18]. A detailed understanding of these biases is crucial for developing robust experiments and accurate data analysis. This guide addresses common biases encountered during RNA-seq library preparation, providing targeted troubleshooting advice and solutions to help researchers mitigate these issues.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Library Yield

Low library yield can stall projects and result from issues at multiple preparation stages.

Root Causes and Corrective Actions

| Cause Category | Specific Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Input/Quality | Degraded RNA or sample contaminants (e.g., phenol, salts) inhibiting enzymes [19]. | Re-purify input sample; ensure 260/230 ratio >1.8 [19]. |

| Quantification errors from absorbance methods (e.g., NanoDrop) overestimating usable material [19]. | Use fluorometric quantification (e.g., Qubit) for accurate measurement [19]. | |

| Fragmentation & Ligation | Suboptimal adapter ligation due to poor ligase performance or incorrect adapter-to-insert molar ratio [19]. | Titrate adapter:insert ratio; ensure fresh ligase and optimal reaction conditions [19]. |

| Amplification/PCR | Enzyme inhibitors present in the reaction [19]. | Use master mixes to reduce pipetting errors and ensure reagent quality [19]. |

| Purification & Cleanup | Overly aggressive purification or size selection, leading to sample loss [19]. | Optimize bead-to-sample ratios and avoid over-drying beads during cleanup [19]. |

Problem: Amplification Bias

PCR amplification can stochastically introduce biases, leading to uneven representation of cDNA molecules and high duplicate rates [18].

Strategies for Mitigation

| Strategy | Methodological Details | Effect on Bias |

|---|---|---|

| Polymerase Selection | Use high-fidelity polymerases (e.g., Kapa HiFi) over others like Phusion for more uniform amplification [18]. | Red preferential amplification of sequences with neutral GC content [18]. |

| Cycle Optimization | Reduce the number of PCR amplification cycles to a minimum [18]. | Minimizes overamplification artifacts and reduces duplicate read rates [19]. |

| PCR Additives | For extreme AT/GC-rich sequences, use additives like TMAC or betaine [18]. | Helps mitigate sequence-dependent amplification bias [18]. |

| Amplification-Free Protocols | For samples with sufficient starting material, use PCR-free library construction methods [18]. | Eliminates PCR amplification bias entirely [18]. |

Problem: Primer and Fragmentation Bias

The initial steps of priming and fragmentation can create non-random representation of the transcriptome.

Sources and Improvements

| Bias Type | Description | Suggestions for Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| Random Hexamer Priming Bias | Inefficient or non-random annealing of hexamer primers during cDNA synthesis, leading to mispriming and uneven 5' coverage [18]. | Use a read count reweighing scheme in bioinformatics analysis to adjust for the bias [18]. For specialized applications, consider direct RNA sequencing without reverse transcription [18]. |

| RNA Fragmentation Bias | Non-random fragmentation using enzymes like RNase III can reduce library complexity [18]. | Use chemical treatment (e.g., zinc) for more random fragmentation [18]. Alternatively, fragment cDNA after reverse transcription using mechanical or enzymatic methods [18]. |

| Adapter Ligation Bias | T4 RNA ligases can have sequence preferences, affecting which fragments are successfully ligated and sequenced [18]. | Use adapters with random nucleotides at the ligation extremities to reduce sequence dependence [18]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How much RNA is typically required for a standard RNA-seq library? The quantity of RNA required depends on the sample type and protocol, but a general guideline is 100 nanograms to 1 microgram of total RNA for standard protocols on platforms like Illumina. For low-input or degraded samples, specialized kits are available that can work with significantly less material [20].

Q2: What is "library size" in the context of RNA-seq? Library size refers to the average length of the cDNA fragments in your sequencing library. It is a critical parameter checked by capillary electrophoresis (e.g., Bioanalyzer). For Illumina platforms, the optimal library size typically ranges from 200 to 500 base pairs, which includes the inserted cDNA fragment plus the attached adapters [20].

Q3: How can I reduce bias from my RNA extraction method? RNA extraction methods can introduce bias; for instance, TRIzol can lead to small RNA loss at low concentrations. To improve results:

- Use high concentrations of RNA samples if using TRIzol.

- Consider alternative protocols like the mirVana miRNA isolation kit, which has been reported to produce high-yield and high-quality RNA, especially for non-coding RNAs [18].

Q4: What is an advanced method to minimize bias for short RNAs? The Ordered Two-Template Relay (OTTR) method is a recent (2025) innovation designed for precise end-to-end capture of short or degraded RNAs (e.g., miRNA, tRNA fragments). It minimizes bias inherent to traditional ligation and tailing methods by appending both sequencing adapters in a single reverse transcription step, thereby reducing information loss [7].

Experimental Protocols for Bias Reduction

Library Preparation Using Duplex-Specific Nuclease (DSN) for Normalization

This protocol enriches for low-abundance transcripts by normalizing the cDNA library, substantially decreasing the proportion of reads from highly-expressed RNAs [21].

Key Materials:

- Starting Material: 400 ng polyadenylated RNA from ~20 μg total RNA [21].

- Key Reagent: Crab Duplex-Specific Nuclease (DSN, Evrogen) [21].

- Primers: 19-20 bp primers for initial amplification; full-length Illumina paired-end primers for final amplification [21].

Detailed Methodology:

- Create High-Complexity Library: Generate a standard RNA-seq library through polyA selection, RNA fragmentation, random hexamer-primed reverse transcription, and second-strand synthesis [21].

- Initial Amplification: Amplify the library to generate 500-1200 ng DNA using the short primers [21].

- Denature and Re-anneal: Denature the amplified library and allow it to re-anneal at 68°C. Abundant sequences re-anneal more quickly and become double-stranded, while rare sequences remain single-stranded [21].

- DSN Treatment: Treat the sample with DSN, which preferentially digests the double-stranded (abundant) molecules [21].

- Repeat and Finalize: A second round of amplification and normalization is often performed. The final normalized library is then amplified with the full-length Illumina primers for sequencing [21].

Workflow for Standard RNA-Seq Library Preparation

The following diagram outlines the key steps in a standard RNA-seq library preparation workflow, highlighting stages where specific biases commonly originate.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Kit | Function in Library Preparation | Consideration for Bias Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Duplex-Specific Nuclease (DSN) [21] | Normalizes cDNA libraries by digesting double-stranded (abundant) re-annealed molecules, enriching for rare transcripts. | Crucial for reducing dynamic range and improving detection of low-abundance RNAs. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (e.g., Kapa HiFi) [18] | Amplifies the adapter-ligated library during PCR. | Provides more uniform amplification across sequences with different GC contents compared to other polymerases. |

| mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit [18] | Extracts total RNA, including small RNAs. | Reduces bias against small non-coding RNAs often encountered with TRIzol extraction. |

| R2 Reverse Transcriptase (in OTTR) [7] | Engineered reverse transcriptase for the OTTR method that enables precise end-to-end capture of RNA molecules. | Minimizes bias from ligation and tailing for short RNAs; improves 3' and 5' end precision. |

| Magnetic Beads (e.g., AMPure, Dynabeads) [21] [19] | Purify and size-select nucleic acids after various enzymatic steps. | Incorrect bead-to-sample ratios can cause size selection bias or sample loss; optimization is key [19]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Managing PCR Duplication in RNA-seq Libraries

Q: What causes high PCR duplication rates in my RNA-seq data, and how can I reduce them?

High PCR duplication rates occur when a small subset of original RNA molecules is over-amplified during library preparation. This skews representation and can mask true biological variation. Common causes and solutions are detailed below.

Cause: Limited Input Material or Low Library Complexity

- Solution: Ensure sufficient RNA input. For low-input or degraded samples (e.g., FFPE), use specialized protocols that require higher RNA input or employ kits designed for low-quality/quantity RNA to maximize the diversity of starting molecules [18].

Cause: Over-Amplification during Library PCR

Cause: Bias from Ligation Steps

- Solution: Consider advanced ligation methods. Standard adaptor ligation using T4 RNA ligases is a known source of bias, leading to over-representation of specific sequences. Using a protocol with randomized splint ligation can significantly reduce this bias and increase the sensitivity for detecting diverse small RNAs [23].

FAQ: Overcoming GC Bias in PCR Amplification

Q: Why are GC-rich templates difficult to amplify, and what strategies can improve success?

GC-rich templates (typically >60% GC content) are challenging due to their high thermostability and tendency to form secondary structures. The following table summarizes the primary challenges and general solution approaches.

| Challenge | Root Cause | Solution Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| High Thermal Stability | Three hydrogen bonds in G-C base pairs require more energy to denature [24] [25]. | Increase denaturation temperature; use specialized polymerases. |

| Formation of Secondary Structures | GC-rich regions readily form stable hairpins and stem-loops that block polymerase progression [24] [25]. | Use additives (e.g., DMSO, betaine); choose high-processivity enzymes. |

| Non-specific Primer Binding | Stable secondary structures in primers and templates promote mispriming [25]. | Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration; increase annealing temperature. |

Detailed solutions for GC bias:

Polymerase and Buffer Selection: Use polymerases specifically engineered for GC-rich templates. Kits often include specialized buffers and GC enhancers. For example:

- OneTaq DNA Polymerase with GC Buffer and Enhancer can amplify templates with up to 80% GC content [24].

- Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase with its GC Enhancer is ideal for long or difficult amplicons [24].

- AccuPrime GC-Rich DNA Polymerase, derived from Pyrococcus furiosus, retains activity at high temperatures, aiding in denaturation [25].

Optimize Reaction Additives: Additives help denature stable GC structures.

- DMSO: Typically used at 2-10%, but concentrations above 5% can reduce polymerase activity [26].

- Betaine (or TMAC): Used at 0.5-2 M concentrations to equalize the melting temperatures of GC-rich and AT-rich regions [18] [26].

- Glycerol: Can be added at 5-25% to stabilize enzymes and influence DNA melting [26].

Adjust Thermal Cycling Conditions:

- Denaturation: Increase the denaturation temperature (up to 95°C) or extend the denaturation time, especially for the first few cycles [24] [25]. Note that very high temperatures can degrade polymerase over time [25].

- Annealing: Use a temperature gradient to find the optimal annealing temperature. A higher annealing temperature improves specificity but may reduce yield [24] [27] [22].

- Ramp Rates: Employing slower temperature ramp rates ("slow-down PCR") can help polymerase navigate through complex secondary structures [25].

Magnesium Concentration: Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration. While 1.5-2 mM is standard, GC-rich PCR may require fine-tuning. Test a gradient from 1.0 mM to 4.0 mM in 0.5 mM increments to find the ideal concentration for specificity and yield [24] [27].

GC-Rich PCR Troubleshooting Flowchart

Experimental Protocols for Bias Reduction

Protocol: Reducing Ligation Bias with Randomized Splint Ligation

This protocol is adapted from a low-bias small RNA library preparation method [23].

- 3' Adapter Ligation: Ligate a pre-adenylated 3' adapter to the RNA fragments using randomized splint ligation. The splint contains random nucleotides that base-pair with the RNA fragment, reducing sequence-dependent ligation bias.

- Clean-up: Deplete excess adapter using a 5' deadenylase and lambda exonuclease.

- Cleavage: Cleave the degenerate portion of the adapter by treating with USER enzyme to excise deoxyuracil.

- 5' Adapter Ligation: Ligate the 5' adapter using the same randomized splint ligation method.

- Reverse Transcription: Synthesize cDNA using the remaining portion of the 3' adapter splint as a primer.

- PCR Enrichment: Amplify the library using primers complementary to the adapter sequences.

Protocol: Optimized PCR for GC-Rich Targets

This protocol synthesizes recommendations from multiple sources [24] [25] [26].

- Reaction Setup:

- Polymerase: 1-2 units of a GC-optimized polymerase (e.g., OneTaq or Q5).

- Buffer: Use the manufacturer's supplied GC buffer.

- GC Enhancer: If provided, add at the recommended concentration (e.g., 10-20% of the reaction volume).

- Additives: Supplement with DMSO (2-5% final) or betaine (0.5-1 M final).

- Mg²⁺: Start with the manufacturer's recommended concentration (often 1.5-2 mM MgCl₂).

- Template: 10-100 ng of high-quality genomic DNA.

- Thermal Cycling:

- Initial Denaturation: 98°C for 2 minutes.

- Amplification (35-40 cycles):

- Denaturation: 98°C for 20-30 seconds. For very difficult templates, use 95-98°C for 10-20 seconds.

- Annealing: Use a temperature 3-5°C below the primer Tm. For non-specific bands, increase temperature by 2°C increments.

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kb.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes.

Table 1: Polymerase Systems for GC-Rich and High-Fidelity PCR

| Polymerase System | Key Feature | Ideal GC Content Range | Fidelity (Relative to Taq) | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OneTaq DNA Polymerase (NEB) | Standard & GC Buffers available | Up to 80% (with GC Enhancer) [24] | 2x [24] | Routine and GC-rich PCR [24] |

| Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB) | High Fidelity & GC Enhancer | Up to 80% (with GC Enhancer) [24] | >280x [24] | Long, difficult, and GC-rich amplicons [24] |

| AccuPrime GC-Rich DNA Polymerase (ThermoFisher) | High processivity at high T | High (specific range not stated) | Not specified | GC-rich templates [25] |

| Kapa HiFi DNA Polymerase | Reduced amplification bias | Effective for neutral GC% [28] | High (specific value not stated) | Library amplification for NGS [28] |

Table 2: Optimization of PCR Additives for GC-Rich Templates

| Additive | Recommended Concentration | Mechanism of Action | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO | 2-10% [26] | Disrupts base pairing, reduces secondary structure formation [24] | >5% can inhibit polymerase; may increase error rate [26] |

| Betaine | 0.5 - 2.0 M [26] | Equalizes template melting temps, inhibits secondary structure formation [24] [18] | Can be a component of commercial "GC Enhancer" solutions [24] |

| Glycerol | 5-25% [26] | Stabilizes enzymes, can lower DNA melting temperature [24] | High concentrations may alter enzyme kinetics |

| 7-deaza-dGTP | Partial substitution for dGTP | dGTP analog that weakens base pairing, reducing template stability [24] [25] | Does not stain well with ethidium bromide [24] |

| GC-RICH Resolution Solution (Roche) | 0.5 - 2.5 M (titrate) | Proprietary solution containing detergents and DMSO [26] | Part of a specialized system for GC-rich templates |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Bias-Reduced PCR

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Managing PCR Bias

| Item | Function in Bias Reduction |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity, GC-Rich Polymerases (e.g., Q5, OneTaq GC) | Engineered for high processivity and affinity to navigate through complex secondary structures in GC-rich templates, providing robust amplification [24] [27]. |

| GC Enhancer / Betaine | Homogenizes the melting behavior of DNA, preventing the stalling of polymerase at stable secondary structures and promoting uniform amplification of regions with varying GC content [24] [18]. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerases | Remain inactive until a high-temperature activation step, preventing non-specific priming and primer-dimer formation at lower temperatures, thereby improving specificity and yield [27] [22]. |

| Randomized Splint Adapters | Used in ligation-based library prep to minimize sequence-dependent ligation bias, ensuring a more uniform representation of all RNA fragments in the final library [23]. |

Randomized Splint Ligation Workflow

Sequencing Platform and Contextual Biases

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the main sources of bias in RNA-seq library preparation? Biases can be introduced at virtually every step of the RNA-seq workflow. The primary sources include:

- Sample Preservation: Using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples can cause RNA fragmentation, cross-linking, and chemical modifications, leading to poor sequencing libraries [18].

- RNA Extraction: Certain extraction methods, like TRIzol, can lead to the loss of small RNAs, especially at low concentrations [18].

- mRNA Enrichment: Poly(A) selection can cause 3'-end capture bias, under-representing the 5' ends of transcripts [18].

- Fragmentation: Enzymatic fragmentation (e.g., using RNase III) is not completely random and can reduce library complexity [18].

- Priming Bias: Random hexamers used in reverse transcription can bind with varying efficiencies across transcripts, creating an uneven representation [18].

- Adapter Ligation: T4 RNA ligases have sequence-dependent preferences, leading to the over-representation of certain fragments [28].

- PCR Amplification: This step stochastically introduces biases, as different molecules are amplified with unequal probabilities. This can lead to under-representation of both AT-rich and GC-rich regions [18] [29].

How does my choice of sequencing platform influence bias? The sequencing platform itself can be a source of bias, often referred to as "platform bias" [18]. Furthermore, the instrument type dictates the required library preparation protocol, which has a major impact. Key specifications like read length and throughput should be matched to your application to minimize interpretive biases [30]. For instance, short-read platforms may struggle with complex genomic regions, while long-read platforms can span repetitive sequences but often have higher per-base error rates [30] [31].

What is the best RNA-seq method for degraded RNA samples, such as those from FFPE tissue? For degraded or low-quality total RNA (e.g., RIN 2-3 from FFPE samples), random-primed library preparation protocols are recommended over oligo(dT)-primed methods [18] [32]. Kits like the SMARTer Stranded or SMARTer Universal Low Input RNA Kit are designed for this purpose, as they do not rely on intact poly-A tails [32]. Prior ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion is typically required when using random priming [32].

How can I reduce bias during library amplification?

- Minimize PCR Cycles: Reduce the number of amplification cycles as much as possible to prevent the preferential amplification of certain fragments [18].

- Use High-Fidelity Polymerases: Polymerases like KAPA HiFi are engineered to reduce amplification biases compared to others like Phusion [28].

- Employ UMIs: Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) are short random sequences added to each molecule before amplification. They allow for bioinformatic correction of PCR bias and errors by identifying reads that originated from the same original molecule [33].

- Consider PCR-Free Protocols: For sufficient starting material, amplification-free protocols entirely avoid PCR-induced bias [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Library Yield

Low library yield can halt progress and waste resources. The following table outlines common causes and their solutions.

| Cause | Mechanism of Yield Loss | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Input Quality / Contaminants | Enzyme inhibition from residual salts, phenol, or EDTA [19]. | Re-purify input sample; ensure high purity (e.g., 260/230 > 1.8); use fresh wash buffers [19]. |

| Inaccurate Quantification | Under-estimating input leads to suboptimal enzyme stoichiometry [19]. | Use fluorometric methods (Qubit) over UV absorbance (NanoDrop); calibrate pipettes [19]. |

| Suboptimal Adapter Ligation | Poor ligase performance or incorrect adapter-to-insert molar ratio [19]. | Titrate adapter:insert ratios; ensure fresh ligase and buffer; optimize incubation time and temperature [19]. |

| Overly Aggressive Purification | Desired library fragments are accidentally removed during clean-up steps [19]. | Optimize bead-based clean-up ratios; avoid over-drying beads to prevent inefficient resuspension [19]. |

Problem 2: Over-representation of Specific Sequences

This bias results in an inaccurate representation of transcript abundance in your data.

Symptoms:

- A few specific sequences have significantly higher read counts than expected.

- Skewed gene expression measurements.

Root Causes and Protocols for Bias Reduction:

Adapter Ligation Bias:

- Cause: T4 RNA ligases have strong sequence and structure preferences. Fragments that co-fold with the adaptor sequence are ligated more efficiently, leading to their over-representation [28].

- Solution - Use Random-Base Adapters: Instead of standard adapters, use adapters with random nucleotides at the extremities to be ligated. This randomizes the ligation junction and can significantly reduce sequence-dependent bias [18].

- Solution - Alternative Ligation Protocol: The CircLig protocol, which uses a single adaptor and circularization, has been shown to reduce over-representation compared to standard duplex adaptor protocols [28].

PCR Amplification Bias:

- Cause: GC-rich or AT-rich regions can amplify less efficiently, leading to their under-representation [18] [29].

- Solution - Polymerase and Additives: Use bias-reducing polymerases like KAPA HiFi. For extremely AT/GC-rich sequences, PCR additives like TMAC or betaine can help, as can lowering extension temperatures [18].

- Solution - Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): Incorporate UMIs during library preparation. During data analysis, UMIs allow you to deduplicate reads, correcting for both PCR bias and errors by counting only unique original molecules [33] [34].

Problem 3: High Ribosomal RNA Read Contamination

A high percentage of reads aligning to rRNA indicates inefficient removal of ribosomal RNA.

Symptoms:

- More than 10-20% of sequencing reads map to ribosomal RNA.

- Lower coverage of your RNA species of interest (e.g., mRNA, lncRNA).

Root Causes and Solutions:

- Incorrect Enrichment Method:

- Inefficient rRNA Depletion Protocol:

- Cause: The depletion kit or protocol is not optimized for your specific sample type or input amount.

- Solution: Follow kit recommendations for input RNA quantity and quality. For example, the RiboGone - Mammalian kit is recommended for 10–100 ng samples of mammalian total RNA [32].

The diagram below maps the standard RNA-seq library preparation workflow and highlights key points where biases are most likely to be introduced.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and their roles in reducing specific biases during RNA-seq library preparation.

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Bias-Reducing Application |

|---|---|---|

| RiboGone - Mammalian Kit | Depletes ribosomal RNA from mammalian total RNA samples [32]. | Eliminates the need for poly-A selection, avoiding 3'-end bias. Essential for studying non-polyadenylated RNA (e.g., lncRNA) or degraded samples [32] [33]. |

| SMARTer Stranded RNA-Seq Kit | A random-primed library prep kit that maintains strand-of-origin information [32]. | Ideal for degraded RNA (FFPE) and non-polyadenylated RNA, as it does not rely on an intact 3' poly-A tail [32]. |

| KAPA HiFi DNA Polymerase | A high-fidelity PCR enzyme engineered for robust amplification of GC-rich templates [28]. | Reduces PCR amplification bias, particularly the under-representation of GC-rich and AT-rich regions [18] [28]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random barcodes added to each RNA molecule before any amplification steps [33]. | Allows bioinformatic correction of PCR bias and errors by accurately counting pre-amplification molecules, mitigating over-amplification effects [33] [34]. |

| Random-Base Adapters | Adaptors with degenerate nucleotides at the ligation junctions [18]. | Reduces sequence-specific bias during adapter ligation by randomizing the interaction with T4 RNA ligase [18]. |

| CircLigase ssDNA Ligase | An enzyme used to circularize single-stranded DNA in alternative library prep protocols [28]. | Used in the "CircLig protocol," which has been shown to reduce over-representation of specific sequences compared to standard duplex adaptor protocols [28]. |

Strategic Protocol Selection for Optimal Library Construction

A foundational step in a successful RNA-seq experiment is the selective analysis of messenger RNA (mRNA) against a background where it can constitute as little as 1-5% of total RNA, with ribosomal RNA (rRNA) making up the overwhelming majority (80-98%) [35]. The two primary strategies to overcome this are poly(A) enrichment and rRNA depletion. The choice between them is critical, as it directly influences data quality, coverage, and the accuracy of biological interpretation. Within the broader goal of optimizing RNA-seq library preparation to reduce bias, the integrity of your starting RNA sample is the most decisive factor in selecting the appropriate method. This guide provides troubleshooting and FAQs to help you make an informed choice.

FAQ: Choosing Your Method

What is the core difference between mRNA enrichment and rRNA depletion?

- mRNA Enrichment (Poly(A) Selection): This method uses magnetic beads coated with oligo(dT) sequences to "fish out" RNA molecules that have a poly(A) tail, which is a hallmark of mature eukaryotic mRNAs. It is a targeted enrichment of desired transcripts [35].

- rRNA Depletion (Ribo-Depletion): This method uses species-specific probes (DNA or LNA oligonucleotides) that are complementary to rRNA sequences. These probes hybridize to the rRNA, which is then removed from the sample through magnetic separation or enzymatic digestion. This is a targeted depletion of unwanted transcripts [36] [18].

How does RNA integrity directly affect my choice of method?

The performance of poly(A) enrichment is highly dependent on RNA quality, whereas rRNA depletion is more robust to degradation [35].

- High-Quality RNA (RIN > 8): You can reliably use either method. Poly(A) enrichment is often the default for standard eukaryotic mRNA sequencing due to its cost-efficiency and focus on protein-coding genes [35].

- Degraded or Low-Quality RNA (RIN < 7): You should use rRNA depletion. In degraded samples, RNA fragments may lack the poly(A) tail necessary for capture. Poly(A) enrichment of such samples will lead to a strong 3' bias and significant loss of coverage across the transcript body [35]. rRNA depletion probes target multiple sites along the rRNA molecules, making them effective even on fragmented RNA [37].

Does my organism of study influence the decision?

Absolutely. This is a primary consideration.

- Eukaryotic Samples: You have the flexibility to use either poly(A) enrichment or rRNA depletion.

- Prokaryotic Samples: You must use rRNA depletion. Bacterial mRNAs lack a stable poly(A) tail, making poly(A) enrichment ineffective [35] [37].

What are the specific biases associated with each method?

Understanding inherent biases is key to unbiased data interpretation.

Poly(A) Enrichment Bias:

- 3' Bias: In degraded or low-input samples, the method preferentially captures the 3' ends of transcripts, skewing expression data [35] [18].

- Transcriptome Coverage Bias: It systematically excludes non-polyadenylated RNAs of interest, such as histone genes, many long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and some circular RNAs [35].

rRNA Depletion Bias:

- Probe Design Bias: Depletion efficiency hinges on probe design. Incomplete probe coverage of all rRNA variants can lead to residual rRNA reads (often 5-50%) [36] [38].

- Species Specificity: Probes are often species-specific. Using a kit designed for one organism on a distant relative can result in poor depletion efficiency [35].

- * enzymatic Depletion Bias*: Methods using duplex-specific nucleases (DSN) or RNase H can suffer from off-target activity, digesting non-rRNA transcripts with partial complementarity to the probes [38].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Scenarios and Solutions

| Scenario | Symptom | Root Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degraded FFPE or Tissue Sample | Low mapping to mRNA, high 3' bias in coverage plots. | Poly(A) tails are lost or inaccessible due to fragmentation. | Switch to an rRNA depletion protocol. Use high-input RNA amounts to compensate for degradation [18] [39]. |

| High Residual rRNA in Prokaryotic Seq | >50% of reads map to rRNA after "depletion". | Inefficient probe hybridization due to species mismatch or suboptimal protocol. | Use a species-specific depletion kit (e.g., riboPOOLs) or design custom biotinylated probes [38]. Optimize hybridization conditions. |

| Low RNA Input (Bacterial) | Failed library preparation or extremely low complexity. | Standard commercial kits require >100ng total RNA. | Use a specialized low-input method like EMBR-seq, which uses blocking primers and linear amplification for inputs as low as 20pg [37]. |

| Low Gene Detection in Eukaryotic Seq | Fewer genes detected than expected, missing non-coding RNAs. | Poly(A) selection excludes non-polyadenylated transcripts. | If your target includes lncRNAs or other non-poly(A) RNA, switch to rRNA depletion [35] [39]. |

| One Round of Enrichment is Insufficient | rRNA still constitutes ~50% of the sample after one round of poly(A) selection or ribo-depletion. | Standard protocols may not be fully efficient for all sample types. | For poly(A) enrichment, perform two consecutive rounds of selection or optimize the beads-to-RNA ratio to significantly improve purity [36]. |

Decision Workflow

The following diagram outlines the logical decision process for choosing between mRNA enrichment and rRNA depletion.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table summarizes key commercial solutions and their optimal use cases.

| Reagent / Kit | Method | Primary Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oligo(dT)25 Magnetic Beads [36] | Poly(A) Enrichment | Enrichment of eukaryotic mRNA from high-quality RNA. | Cost-effective; requires user-prepared buffers. Efficiency improves with optimized bead:RNA ratios [36]. |

| RiboMinus Kit [36] | rRNA Depletion | Depletion of rRNA from eukaryotic or prokaryotic RNA. | Targets 18S/25S (eukaryotes) or 16S/23S (prokaryotes). May not cover 5S rRNA, leading to residual contamination [38] [36]. |

| riboPOOLs [38] | rRNA Depletion | High-efficiency, species-specific rRNA depletion. | More effective than pan-prokaryotic kits for specific organisms. An adequate replacement for the discontinued RiboZero [38]. |

| NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Kit [40] | Poly(A) Enrichment | Standard mRNA sequencing from intact eukaryotic RNA. | Used in published RNA-seq workflows with high-quality input (RIN > 7.0) [40]. |

| EMBR-seq (Protocol) [37] | rRNA Depletion | Sequencing from ultra-low input and degraded bacterial RNA. | Uses blocking primers and in vitro transcription; cost-effective for non-model bacteria [37]. |

| Watchmaker RNA Kit with Polaris Depletion [39] | rRNA Depletion | Sensitive RNA-seq from challenging samples (FFPE, blood). | Includes reagents for rRNA and globin depletion, ideal for clinically derived samples [39]. |

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing Poly(A) Enrichment for Yeast RNA

Background: A single round of poly(A) enrichment may be insufficient, leaving rRNA content as high as 50% [36]. This protocol describes an optimized two-round enrichment to reduce rRNA to below 10%.

Materials:

- Oligo(dT)25 Magnetic Beads (e.g., from New England Biolabs)

- Total RNA from Saccharomyces cerevisiae

- Binding Buffer (e.g., 20 mM Tris-HCl, 1.0 M LiCl, 2 mM EDTA)

- Wash Buffer (e.g., 10 mM Tris-HCl, 0.15 M LiCl, 1 mM EDTA)

- Nuclease-free water

Method:

- Denaturation: Dilute 10 µg of total yeast RNA in 50 µL of nuclease-free water. Heat at 65°C for 5 minutes to disrupt secondary structures, then immediately place on ice.

- First Binding: Add 50 µL of well-resuspended Oligo(dT)25 Magnetic Beads and 100 µL of 2X Binding Buffer to the RNA. Use a beads-to-RNA ratio of 1:1 (w/w). Mix thoroughly and incubate at room temperature for 15 minutes with gentle rotation.

- Washing: Place the tube on a magnetic stand. After the solution clears, discard the supernatant. Wash the beads twice with 200 µL of Wash Buffer.

- Elution: Elute the poly(A) RNA from the beads by adding 20 µL of nuclease-free water and heating at 80°C for 2 minutes. Immediately transfer to the magnetic stand and carefully collect the supernatant containing the enriched mRNA.

- Second Binding (Repeat): To the eluate from the first round, add a fresh 50 µL aliquot of Oligo(dT)25 Magnetic Beads and 100 µL of 2X Binding Buffer. Repeat the binding, washing, and elution steps.

- Quality Control: Assess the yield and purity of the final enriched RNA using capillary electrophoresis (e.g., TapeStation). The 18S and 25S rRNA peaks should be drastically reduced, with rRNA content typically falling below 10% of the total RNA [36].

Note: This two-round protocol is more time-consuming and results in lower final yields but provides a much purer mRNA population for sequencing, reducing costs and improving data quality per sequencing read.

FAQ: Fragmentation Method Selection

Q1: How do I choose between mechanical and enzymatic fragmentation for my RNA-seq library?

The choice depends on your research priorities, including sample input, required uniformity, throughput, and budget.

| Factor | Mechanical Fragmentation | Enzymatic Fragmentation |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Bias | Minimal sequence bias; closest to ideal molecular randomness [41] | Potential for sequence-specific bias (e.g., motif preference, GC skew) [42] [41] |

| Sample Input | Higher potential for sample loss due to extra handling [42] | Recommended for low-input samples (<100 ng); minimal handling loss [42] [43] |

| Throughput & Automation | Limited parallel processing; less automation-friendly [42] | High-throughput and easily automated; suitable for many samples [42] [43] |

| Equipment Cost | Requires specialized, costly instrumentation (e.g., sonicator) [42] [41] | Lower equipment cost; relies mainly on reagents [42] [43] |

| Uniformity & Coverage | Gold standard for even genome coverage; crucial for variant calling [41] | Modern kits approach mechanical randomness, but may have GC skew [41] |

| Protocol Speed | Slower due to separate shearing and cleanup steps [41] | Faster; can be combined with end-repair and A-tailing in one tube [42] [43] |

For RNA-seq, the fragmentation method is a key determinant of data quality, as more stochastic breakage leads to more even and reliable downstream analysis [41]. If your primary goal is quantitative accuracy with minimal bias, mechanical shearing is superior. For high-throughput studies where speed and cost are paramount, enzymatic methods are more pragmatic [42] [41].

Q2: What are the common signs of fragmentation failure, and how can I troubleshoot them?

Poor fragmentation can manifest in several ways during library QC and sequencing.

| Problem | Observed Failure Signals | Recommended Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Over-/Under-Fragmentation | Unexpected fragment size distribution; skewed insert sizes [19] [43] | Optimize enzyme concentration/digestion time or sonication energy/duration [42] [19]. Pre-check fragmentation profile [19]. |

| High Adapter-Dimer Peaks | Sharp peak at ~70-90 bp on bioanalyzer electropherogram [19] | Titrate adapter-to-insert molar ratio [19]. Use purification beads with the correct sample-to-bead ratio to remove small fragments [19]. |

| Low Library Yield | Low final concentration; broad or faint peaks during QC [19] | Re-purify input sample to remove enzyme inhibitors. Ensure high purity (260/230 > 1.8) [19]. Optimize ligation conditions [19]. |

| Uneven Coverage/GC Bias | Dropouts in high or low GC regions; uneven read depth [41] | If using enzymatic methods, test PCR-free protocols or use spike-in standards to correct bias [41]. Switch to mechanical shearing for maximal uniformity [41]. |

A general diagnostic flow is to: 1) Check the electropherogram for abnormal peaks or distributions, 2) Cross-validate quantification methods (e.g., Qubit vs. BioAnalyzer), and 3) Trace the problem backwards through the library prep steps to identify the root cause [19].

Q3: How does fragmentation bias impact my RNA-seq results?

Fragmentation bias can severely compromise the integrity and interpretability of your RNA-seq data. Non-random fragmentation generates libraries that are not truly representative of the starting sample, leading to:

- Reduced Library Complexity: This inflates PCR duplicate rates, as fewer unique starting molecules are available for amplification. Downstream software may collapse reads that are in fact derived from different original RNA molecules, leading to a loss of biological information [41].

- Uneven Sequence Coverage: Biased fragmentation creates regions that are over- or under-represented in the sequencing data. This can artificially flatten or inflate expression counts for specific transcripts or genomic regions, making accurate differential expression analysis difficult [41] [13].

- Misleading Variant Calls: Inconsistent coverage can create false positive or false negative variant calls. Dips in coverage can be mistaken for deletions, while highly covered regions may mask the true allele frequency of a single-nucleotide variant (SNV) [41].

- Compromised De Novo Assembly: For transcriptome assembly, non-random breakpoints create "fragile sites" where read clouds terminate abruptly, resulting in shorter contigs and a less complete assembly [41].

Mitigating these biases is therefore critical for obtaining reliable biological conclusions [13].

Experimental Protocols for Key Comparisons

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Fragmentation Bias Using Spike-In Controls

This protocol assesses the sequence-specific bias introduced by different fragmentation methods, which is vital for optimizing RNA-seq library preparation [13].

1. Reagents and Materials

- Purified RNA sample (e.g., from HEK293T cells or human tissue)

- Synthetic spike-in RNA controls (e.g., ERCC ExFold RNA Spike-In Mix)

- Mechanical shearing instrument (e.g., Covaris sonicator)

- Enzymatic fragmentation kit (e.g., using endonuclease or tagmentation chemistry)

- Library preparation kit (e.g., VAHTS Universal V8 RNA-seq Library Prep Kit)

- Magnetic beads for cleanup (e.g., AMPure XP)

- Bioanalyzer or TapeStation for QC

2. Methodology

- Step 1: Sample and Spike-In Setup. Split the total RNA sample into two equal aliquots. To each aliquot, add a known quantity of the ERCC spike-in mix, which contains synthetic RNA transcripts of defined lengths and sequences [33] [13].

- Step 2: Parallel Fragmentation. Fragment one aliquot using the optimized mechanical shearing protocol (e.g., focused-ultrasonication). Fragment the second aliquot using the enzymatic protocol (e.g., with a dsDNA fragmentase or tagmentation enzyme) [41] [13].

- Step 3: Library Preparation and Sequencing. Prepare sequencing libraries from both fragmented samples using the same downstream steps (end-repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification) to ensure comparisons are based solely on the fragmentation method [43] [13]. Pool and sequence the libraries on the same flow cell to avoid batch effects.

- Step 4: Data Analysis for Bias Assessment.

- Alignment and Quantification: Map reads to a combined reference genome (e.g., human GRCh38) and the spike-in sequences. Calculate reads per kilobase per million (RPKM) or TPM for each spike-in transcript [13].

- Bias Calculation: For the spike-ins, plot the observed read counts (or RPKM) against the expected molar concentration. The deviation from the expected linear relationship indicates the degree of bias. Calculate correlation coefficients (R²) to quantitatively compare the performance of mechanical vs. enzymatic methods [13].

- GC-Bias Analysis: Analyze the coverage uniformity across transcripts with different GC contents. Mechanical shearing should demonstrate flatter coverage across the GC spectrum compared to enzymatic methods, which may show under-representation of extreme GC-rich or AT-rich regions [41].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Protocol Performance with Low-Quality RNA Samples

This protocol tests the robustness of different fragmentation and library prep methods on degraded RNA, such as that from FFPE tissues, a common challenge in clinical research [3] [33].

1. Reagents and Materials

- High-quality RNA (RIN > 9) and artificially degraded or FFPE-derived RNA (RIN < 5)

- rRNA depletion kit (e.g., Ribo-off rRNA Depletion Kit)

- Both mechanical and enzymatic library prep kits

- Bioanalyzer for RNA and library QC

2. Methodology

- Step 1: Sample Preparation. Obtain or create degraded RNA samples. This can be done by incubating high-quality RNA at elevated temperature for a controlled period. Use the Bioanalyzer to confirm a reduced RNA Integrity Number (RIN) [33].

- Step 2: rRNA Depletion. Treat both high-quality and degraded RNA samples with an rRNA depletion kit. This step is crucial for FFPE/degraded samples as ribosomal RNA fragments can still dominate the sample and poly-A selection fails on fragmented mRNA [33] [13].

- Step 3: Library Preparation with Different Methods. For both RNA quality groups, prepare libraries using:

- Method A: Mechanical shearing (acoustic) followed by a standard stranded RNA-seq protocol.

- Method B: An enzymatic fragmentation protocol (e.g., one utilizing a proprietary nuclease cocktail).

- Method C: A tagmentation-based library prep kit.

- Step 4: QC and Sequencing Analysis.

- Library QC: Assess the final libraries for yield, size distribution, and adapter-dimer content. Enzymatic/tagmentation methods often show better yields from low-input, degraded samples [3].

- Sequencing Metrics: After sequencing, compare the mapping rates, the percentage of reads aligning to exonic regions, the 3' bias (indicative of RNA degradation), and the number of genes detected. Robust methods for low-quality RNA will maintain higher gene detection rates and lower 3' bias [3].

Workflow Diagrams

Fragmentation Method Decision Workflow

RNA-seq Bias Mitigation Strategy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

| Reagent / Material | Function in Fragmentation & Library Prep |

|---|---|

| ERCC Spike-In RNA Controls | A set of synthetic RNA transcripts of known concentration used to diagnose technical bias, assess the dynamic range, and normalize samples in RNA-seq experiments [33] [13]. |

| Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) Depletion Kit | Selectively removes abundant ribosomal RNA from the total RNA population, thereby enriching for coding and non-coding RNA of interest and significantly improving sequencing depth for these transcripts. Essential for degraded samples and bacterial RNA [33] [13]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences added to each cDNA molecule during library prep. UMIs allow for bioinformatic correction of PCR amplification bias and errors, enabling accurate quantification of the original mRNA molecules [33]. |

| Magnetic Beads (AMPure XP style) | Used for post-fragmentation and post-ligation cleanup to remove enzymes, salts, short fragments, and adapter dimers. The bead-to-sample ratio is critical for effective size selection and yield [19] [43]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Used during the library amplification (PCR) step. It has a lower error rate than standard Taq polymerase, minimizing the introduction of mutations during amplification, which is crucial for variant detection [43]. |

FAQs on Random Hexamer Bias

What is random hexamer bias and why does it occur in RNA-seq? Random hexamer bias occurs during the reverse transcription step of RNA-seq library preparation. When random hexamer primers (6-base oligonucleotides) are used to initiate cDNA synthesis, they do not bind to the RNA template with equal probability at all locations. This uneven binding efficiency is influenced by the primer's sequence complementarity to the RNA template, the RNA's secondary structure, and the local GC content. Consequently, some regions of the transcriptome are over-represented while others are under-represented in the final sequencing library, distorting true biological expression measurements [44] [45].

How does random hexamer bias specifically affect my gene expression data? This bias introduces significant inaccuracies in transcript quantification. Regions with optimal complementarity to the hexamers will be over-sampled, leading to inflated read counts for corresponding transcripts. Conversely, regions with poor complementarity or those obscured by secondary structures will be under-sampled. This results in:

- Inaccurate measurement of transcript abundance

- Incomplete coverage across transcripts

- Compromised detection of isoforms and allele-specific expression

- Reduced ability to detect novel transcripts or splicing variants [44] [45]

Are some RNA species more affected by this bias than others? Yes, the impact varies significantly across RNA biotypes. Standard poly(A)+ selection methods, often coupled with hexamer priming, actively deplete non-polyadenylated RNAs from your library. This means non-coding RNAs, immature heterogeneous nuclear RNA, and histone mRNAs (which lack polyA tails) are systematically under-represented. Furthermore, degraded RNA samples (common in FFPE or clinically challenging samples) are particularly susceptible because hexamers can only prime from remaining 3' fragments, creating severe 3' bias in coverage [46] [45].

What are the most effective strategies to mitigate random hexamer bias? The most effective approaches involve either sophisticated computational correction or modified experimental priming techniques:

- Computational Correction: The Gaussian Self-Benchmarking (GSB) framework is a novel method that models the expected, unbiased distribution of k-mers based on their GC content. It then corrects the observed sequencing data to fit this theoretical distribution, effectively mitigating multiple co-existing biases, including those introduced by random hexamers [44].

- Experimental Solutions: Using selective random hexamers is a powerful wet-lab approach. This involves computationally designing a primer set from which hexamers complementary to highly abundant, unwanted sequences (like ribosomal RNA) have been removed. This reduces off-target priming and improves coverage uniformity across the transcriptome of interest [45].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Incomplete Transcript Coverage

Symptoms:

- uneven read coverage across transcript bodies, typically with a strong 3' bias.

- failure to detect known isoforms or alternative splicing events.

- low agreement between technical replicates in coverage patterns.

Solutions:

Implement Selective Random Hexamer Priming

- Principle: Redesign the random hexamer pool by excluding primers that bind to highly abundant sequences you are not interested in (e.g., rRNA). This increases the effective priming on your target transcriptome.

- Protocol:

- Identify and computationally subtract all hexamers that are a perfect match to abundant contaminating RNAs (e.g., from rRNA sequence databases).

- Synthesize a custom pool of the remaining "selective" hexamers.

- Use this custom pool in your reverse transcription reaction instead of standard random hexamers. Studies have shown this can reduce rRNA-derived reads from over 10% to more acceptable levels, though it is less efficient than probe-based depletion [45].

Switch to a Strand-Switching Protocol

- Principle: Many modern RNA-seq kits (e.g., Smart-Seq2) use a template-switching oligonucleotide (TSO) and reverse transcriptase with terminal transferase activity. This method is less reliant on uniform random hexamer binding across the entire RNA template for full-length cDNA generation.

- Protocol:

- Reverse transcribe with a defined primer (e.g., oligo-dT or a custom gene-specific primer) instead of random hexamers.

- The reverse transcriptase adds a few non-templated nucleotides to the 3' end of the cDNA.

- A template-switching oligo (TSO) with complementary bases anneals to this overhang, allowing the reverse transcriptase to "switch" templates and continue replicating the TSO sequence.

- This creates a known universal sequence on the end of all cDNAs, enabling efficient amplification with primers targeting the universal sequence, thereby bypassing the need for random priming along the entire fragment [47].

Problem: GC Content Bias

Symptoms:

- a strong correlation between read coverage and the local GC content of transcripts.

- under-representation of transcripts or genomic regions with extremely high or low GC content.

- distorted gene expression measurements, particularly for GC-rich or GC-poor genes.

Solutions:

Apply the Gaussian Self-Benchmarking (GSB) Framework

- Principle: This method corrects for bias by leveraging the natural observation that the GC content of k-mers in a transcriptome follows a Gaussian distribution. It uses this theoretical distribution as a benchmark to correct empirical data.

- Protocol:

- Categorize k-mers: From your sequencing data, categorize all k-mers based on their GC content.

- Aggregate counts: Calculate the total count of k-mers within each GC-content category.

- Model fitting: Fit a Gaussian distribution to the aggregated counts using pre-determined parameters (mean and standard deviation) that reflect the expected, unbiased distribution.

- Correct counts: Adjust the observed counts in each GC category to match the fitted Gaussian model. The corrected counts for each GC category are then averaged over all corresponding k-mers, systematically reducing bias at targeted positions [44].

Optimize Reaction Conditions

- Principle: The efficiency of random hexamer binding is influenced by buffer conditions. Using higher salt concentrations during the priming and reverse transcription steps can promote more stringent binding, reducing off-target priming and mitigating some sequence-specific biases.

- Protocol:

- Perform the reverse transcription reaction in a buffer containing an elevated concentration of salt (e.g., 75-100 mM KCl or NaCl).

- Combine this with a custom selective random hexamer library for a synergistic effect on reducing bias [45].

Table 1: Comparison of Priming Methods for Bias Mitigation

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selective Random Hexamers [45] | Removes rRNA-complementary hexamers from the primer pool. | Reduces rRNA contamination; improves coverage of target transcripts. | Less effective than probe-based depletion; requires custom synthesis. | Standard RNA-seq where rRNA depletion is not used. |

| Gaussian Self-Benchmarking (GSB) [44] | Computational correction based on theoretical GC distribution. | Corrects multiple biases simultaneously; does not require protocol changes. | Relies on accurate parameter estimation; a post-sequencing solution. | Researchers with bioinformatics support seeking to improve existing data. |

| Strand-Switching (e.g., Smart-Seq2) [47] | Uses template-switching to generate full-length cDNA. | Excellent for full-length transcript coverage; reduces 3' bias. | Typically lower throughput; higher cost per sample. | Studying isoform diversity, allele-specific expression, or with low-input samples. |

Experimental Workflows

Workflow 1: Gaussian Self-Benchmarking for Bias Correction

Workflow 2: Comparing Standard vs. Selective Hexamer Priming

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Key Reagents and Kits for Mitigating Priming Bias

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Role in Bias Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Custom Selective Hexamers [45] | A synthesized pool of random hexamer primers with sequences complementary to abundant rRNAs removed. | Reduces off-target priming and increases the efficiency of sequencing the target transcriptome. |

| Strand-Switching Kits(e.g., Smart-Seq2) [47] | Kits that utilize template-switching oligonucleotides (TSOs) for cDNA synthesis. | Generates more full-length transcripts, overcoming 3' bias and improving coverage across the entire transcript. |

| RNase H-based Depletion Kits(e.g., Ribo-off) [44] [45] | Kits that use RNAse H to enzymatically degrade rRNA after hybridization with DNA probes. | Actively removes rRNA, reducing the burden of non-informative reads and indirectly improving the effective sequencing depth of mRNA. |

| Gaussian Self-BenchmarkingSoftware/Algorithm [44] | A computational framework for post-sequencing data correction. | Simultaneously corrects for GC bias and other sequence-dependent biases introduced during library prep, including hexamer priming bias. |

Adapter Ligation and the Rise of Tagmentation Technology

In the pursuit of reducing bias in RNA-seq research, library preparation methodology stands as a critical determinant of data quality. The choice between traditional adapter ligation and increasingly popular tagmentation technologies involves balancing multiple factors: input requirements, workflow efficiency, coverage uniformity, and potential introduction of technical artifacts. This technical support center provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with practical guidance for selecting, optimizing, and troubleshooting these fundamental approaches.