Resolving the Multi-Mapper Dilemma: A Comprehensive Guide to Accurate RNA-Seq Analysis

This article provides a complete resource for researchers and bioinformaticians grappling with the challenge of multi-mapped reads in RNA-seq data.

Resolving the Multi-Mapper Dilemma: A Comprehensive Guide to Accurate RNA-Seq Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a complete resource for researchers and bioinformaticians grappling with the challenge of multi-mapped reads in RNA-seq data. It explores the genomic origins of sequence ambiguity, from duplicated genes and transposable elements to alternative splicing. The guide evaluates computational strategies for read assignment, including expectation-maximization algorithms, read weighting, and tools like mmquant and MMR. It offers practical solutions for troubleshooting high multi-mapper rates and validates methodologies through comparative analysis of differential expression results. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with actionable protocols, this article empowers professionals in drug development and biomedical research to enhance the accuracy and functional relevance of their transcriptomic studies.

The Genesis of Ambiguity: Understanding Why Reads Multi-Map

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main genomic mechanisms that create duplicated genes and why do they pose a challenge in RNA-seq analysis?

Duplicated genes are primarily created through three mechanisms: Whole Genome Duplication (WGD), recombination (including tandem duplications), and retrotransposition [1] [2]. In RNA-seq analysis, these duplicated sequences are a major source of "multi-mapped reads"—reads that align equally well to multiple locations in the genome [2]. This ambiguity complicates accurate gene and transcript quantification, as it is difficult to determine the true origin of the read, potentially leading to misinterpretation of gene expression levels [2].

Q2: How do I troubleshoot high levels of multi-mapped reads in my RNA-seq data?

High levels of multi-mapped reads often indicate a high proportion of duplicated sequences in your sample. Consider the following troubleshooting steps:

- Verify the Source: First, determine if the multi-mapping is expected. Certain RNA biotypes, such as ribosomal RNA (rRNA), small nuclear RNA (snRNA), small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA), and pseudogenes, naturally have high sequence similarity and are common sources of multi-mapped reads [2].

- Check RNA Integrity: For polyA-selected libraries, ensure your RNA has high biological integrity (e.g., RIN > 8 or RQN > 7). Degraded RNA can lead to a loss of unique sequence information from the 5' end of transcripts, increasing multi-mapping [3].

- Review Library Preparation Method: If studying non-polyadenylated RNAs (e.g., many non-coding RNAs) or working with bacterial transcripts, ensure you used ribosomal RNA depletion instead of poly-A selection. Using the wrong method can leave behind highly abundant, repetitive rRNAs [4] [3].

- Employ Computational Strategies: Use bioinformatic tools that can probabilistically resolve multi-mapped reads rather than discarding them. These tools use expectation-maximization algorithms to distribute reads among their potential origins based on the abundance of uniquely mapped reads [2].

Q3: What is the functional difference between paralogs, ohnologs, and processed pseudogenes?

These terms describe different types of duplicated genes with distinct origins and fates:

- Paralogs: A general term for genes related by a duplication event, as opposed to a speciation event [1].

- Ohnologs: A specific type of paralog created by Whole Genome Duplication (WGD) events [1].

- Processed Pseudogenes: These are genomic copies of mRNAs created by retrotransposition. They lack introns and regulatory sequences of their parent gene, and most acquire mutations that prevent them from being expressed, eventually becoming pseudogenes [2].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the primary duplication mechanisms.

Table 1: Characteristics of Genomic Duplication Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Description | Common Read Mapping Issue | Typical Fate of Duplicated Copies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Duplication (WGD) | Duplication of all chromosomes, often via polyploidization [1]. | Reads map to large, retained homologous regions across chromosomes [1]. | Widespread gene loss (fractionation) and chromosomal rearrangements (diploidization) occur; retained genes are often ohnologs [1]. |

| Recombination (Tandem Duplication) | Unequal crossing over between chromosomes or sister chromatids creates tandemly arrayed genes (TAGs) [1] [2]. | Reads cannot be distinguished between adjacent, nearly identical gene copies [2]. | Duplicates can be maintained, evolve new functions (neofunctionalization), or become pseudogenes [1] [2]. |

| Retrotransposition | mRNA is reverse-transcribed and inserted back into the genome, creating intron-less copies [2]. | High exon-level sequence identity between the functional gene and its processed pseudogene(s) [2]. | Most become unexpressed processed pseudogenes due to a lack of regulatory elements [2]. |

Q4: When should I use Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) in my RNA-seq experiment, and how do they help?

UMIs are short, random barcodes added to each original cDNA molecule during library preparation. We recommend using UMIs in two key scenarios:

- For deep sequencing projects (>50 million reads per sample) [4].

- For experiments with low-input RNA for library preparation [4].

UMIs help correct two types of bias introduced by PCR amplification:

- Amplification Bias: Some molecules are amplified more efficiently than others, distorting the true abundance in the final library.

- PCR Errors: mutations introduced during amplification can be mistaken for true biological variants.

By tagging each original molecule, all PCR copies derived from it will share the same UMI. During analysis, reads with the same UMI and mapping position can be collapsed into a single "unique" molecule, providing a more accurate count of the original transcript abundance and reducing noise [4].

Q5: My variant caller (e.g., Mutect2) is failing on my RNA-seq BAM files with an error "Cannot construct fragment from more than two reads." What is causing this and how can I fix it?

This error occurs when three or more reads in the BAM file share the same name [5]. In RNA-seq data, this is frequently caused by multi-mapping reads, where a single read sequence aligns to multiple genomic locations. The aligner may report these multiple alignments, leading to several reads with identical names, which violates the assumption that a fragment comes from one read-pair [5].

Solution: The most straightforward solution is to use the --independent-mates argument in Mutect2, which instructs the tool to ignore read-pairing during genotyping [5]. However, note that the GATK team recommends this as a temporary fix and advises turning this option off in future versions where the underlying issue is resolved. Alternatively, you can pre-process your BAM file to remove or handle multi-mapping reads before variant calling.

Troubleshooting Guide: Handling Multi-Mapped Reads

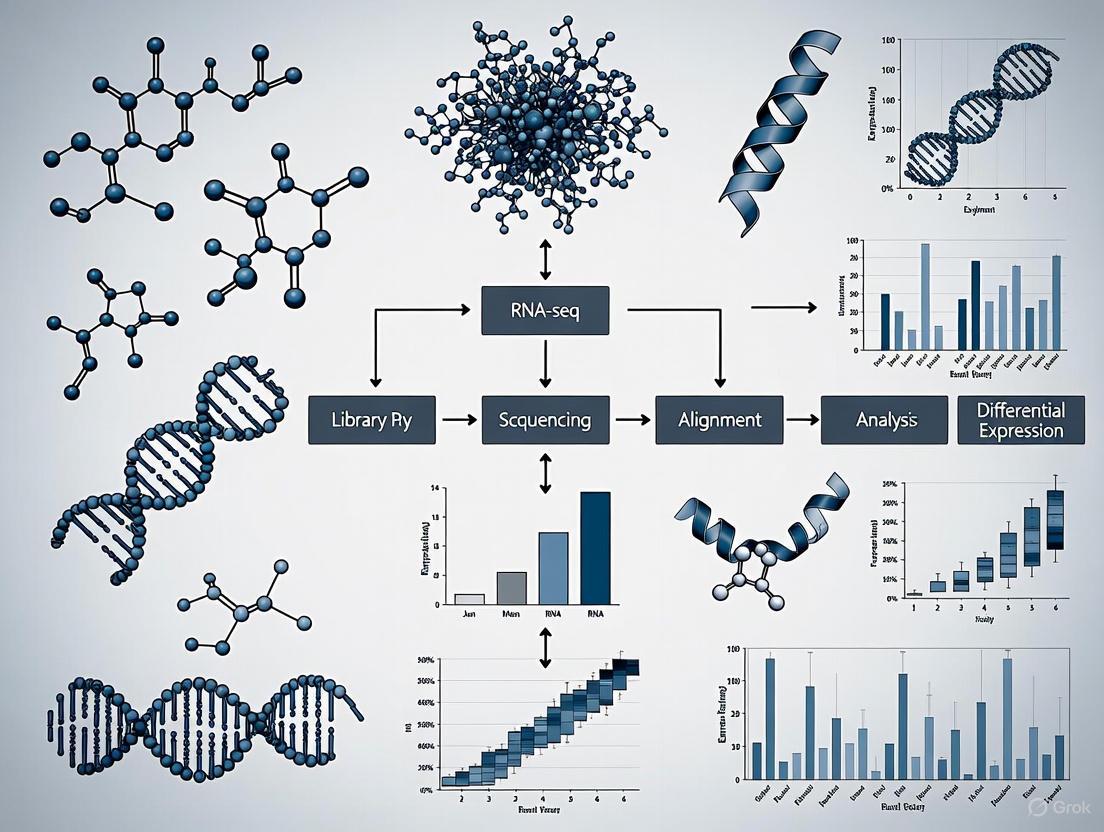

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates a recommended workflow for handling multi-mapped reads in RNA-seq analysis, from experimental design to computational resolution.

Experimental Protocol: RNA-seq for Samples with High Duplication Content

1. Sample Preparation and QC

- RNA Isolation: Use a protocol that retains small RNAs if they are of interest (e.g., a modified Trizol protocol) [3].

- Quality Control: Assess three elements of RNA sample quality [3]:

- Chemical Purity: Use a spectrophotometer (e.g., Nanodrop). Acceptable ratios are 260/230 > 1.5 and 260/280 > 1.8.

- Biological Integrity: Use a Fragment Analyzer, Bioanalyzer, or Tapestation. For polyA selection, an RQN > 7 (or RIN > 8) is recommended. For degraded samples (RQN < 7), use rRNA depletion.

- Total Yield: Use a fluorometric assay (e.g., Qubit) for accurate quantification, especially for low-concentration samples (<20 ng/μL).

2. Library Preparation

- rRNA Removal Method Selection:

- Poly-A Selection: Use for intact eukaryotic mRNA. It provides the cleanest data for protein-coding genes but will miss non-polyadenylated transcripts [4] [3].

- rRNA Depletion: Use for degraded samples, bacterial RNA, or when studying non-coding RNAs. It retains a broader range of transcripts but may be less efficient at rRNA removal [4] [3].

- Strandedness: Opt for stranded library preparation to retain information about the transcript origin, which can help resolve overlaps between genes and their paralogs on opposite strands [3].

- UMI Incorporation: Include Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) to correct for PCR duplication biases, which is particularly valuable in projects with expected high duplication or low input [4].

3. Sequencing and Analysis

- Sequencing Depth: As a general guideline, aim for [4] [3]:

- 20-30 million reads per sample for large eukaryotic genomes (e.g., human, mouse).

- 5-10 million reads per sample for small genomes (e.g., bacteria).

- >100 million reads per sample for de novo transcriptome assembly.

- Bioinformatic Processing:

- Alignment: Use a splice-aware aligner (e.g., STAR).

- Multi-map Resolution: Employ a quantification tool that uses an expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm (e.g., as implemented in Salmon, Cufflinks, or RSEM) to probabilistically distribute multi-mapped reads across their potential loci, rather than discarding them [2].

- UMI Deduplication: If UMIs were used, process reads with tools like

fastporumi-toolsto extract UMIs and collapse PCR duplicates before quantification [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Tool | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Kits (e.g., from NEB) use probes to bind and enzymatically degrade ribosomal RNA, crucial for sequencing non-polyA transcripts or samples from bacteria, plants, or degraded sources [3]. |

| Poly-dT Magnetic Beads | Used in polyA selection to enrich for eukaryotic messenger RNA by hybridizing to the polyA tail, effectively removing rRNA and other non-mRNA [3]. |

| ERCC Spike-In Mix | A set of 92 synthetic RNA transcripts of known concentration. Added to samples before library prep to monitor technical variation, assay sensitivity, and dynamic range of the RNA-seq experiment [4]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide barcodes added to each cDNA molecule to label it uniquely, allowing bioinformatic correction of PCR amplification bias and errors during data analysis [4]. |

| Probabilistic Quantification Tools | Software (e.g., Salmon, RSEM) that uses statistical models to resolve multi-mapped reads, thereby improving the accuracy of gene and transcript abundance estimates [2]. |

| Splice-Aware Aligner (STAR) | A common tool for aligning RNA-seq reads to a reference genome, capable of handling reads that span intron-exon junctions [5]. |

Impact of Transposable Elements and Repetitive Sequences on Read Mapping

FAQs: Addressing Common Challenges in RNA-seq Analysis

What are multi-mapped reads and why are they problematic?

Answer: Multi-mapped reads are sequencing reads that align equally well to multiple locations in a reference genome. They are problematic because they create ambiguity in determining the true origin of the read, leading to potential inaccuracies in gene and transposable element (TE) quantification [6]. This issue is particularly pronounced for repetitive sequences like TEs, which constitute roughly half of the human genome [7] [8]. When analysis pipelines discard these reads, crucial biological information can be lost [7].

Why are transposable elements (TEs) so difficult to map in RNA-seq data?

Answer: TEs pose several distinct challenges for read mapping:

- High Repetitivity: The human genome contains around five million individual TEs [7]. Many of these, especially evolutionarily "young" elements, have very similar or identical sequences, making it impossible to uniquely assign a short read to a single genomic locus [7] [9].

- Poor Annotation: TEs have complex and often fragmented annotations with conflicting nomenclature, which can lead to misleading results [7].

- Non-Reference Elements: Active TEs can create new insertions that are not present in the reference genome. Reads from these polymorphic loci will be misassigned, often to older, reference TEs [9].

What is the difference between multi-mapping and unique mapping strategies?

Answer: These are two common strategies for handling reads in repetitive regions:

- Multi-mapping: This approach gives an overview of the total abundance of an entire TE family or subfamily by counting reads that map to any member. It is useful for getting a general picture but loses precise positional information [7].

- Unique Mapping: This strategy only uses reads that map non-ambiguously to a single genomic location. It provides accurate positional information, which is crucial for understanding the role of specific TEs as enhancers or alternative promoters, but can be biased against younger, less polymorphic TEs [7].

How can I improve the accuracy of TE expression quantification?

Answer: Advanced computational pipelines have been developed to handle multi-mapping reads more intelligently than simple random assignment. These tools often use expectation-maximization (EM) algorithms to iteratively reassign multi-mapped reads to the most probable locus of origin based on all available mapping evidence [9] [10]. For the highest accuracy, consider integrating long-read sequencing data, as the longer read length dramatically increases the chance of spanning unique sequences, thereby resolving ambiguities [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low or Inconsistent Quantification of Young Transposable Elements

Problem: Your analysis is failing to properly quantify evolutionarily young TEs (e.g., human-specific L1HS elements).

Explanation: Young TEs have had less time to accumulate mutations (single nucleotide polymorphisms or indels). This high degree of sequence similarity between copies means that short reads derived from them are far more likely to be multi-mappers and discarded by simple analysis pipelines [9].

Solution:

- Use TE-specific tools: Replace standard gene quantification tools with those designed for TEs, such as Telescope, TEtools, or SalmonTE, which implement EM algorithms to resolve multi-mapped reads [9] [10].

- Incorporate long-read data: If possible, use a hybrid approach. Methods like LocusMasterTE integrate long-read RNA-seq data to guide the reassignment of multi-mapped reads in short-read data, significantly improving locus-specific quantification, especially for young TEs [10].

- Add non-reference insertions: Use long-read DNA sequencing (e.g., Nanopore) and tools like TLDR to identify polymorphic TE insertions not in the reference genome. Create a sample-specific "TE-complete" genome to which RNA-seq reads can be accurately mapped [9].

Experimental Protocol: Resolving Young TE Expression with LocusMasterTE

- Principle: This protocol uses fractional transcript counts from long-read sequencing to inform an expectation-maximization model, improving the reassignment of multi-mapped short reads [10].

- Inputs:

- Short-read RNA-seq data (BAM format).

- Long-read RNA-seq data from a matched cell or tissue type.

- A GTF annotation file containing coordinates of individual TE copies.

- Method:

- Alignment and Annotation: Align both short and long reads to the reference genome. Annotate all reads with their overlapping genomic features, including TEs.

- Categorize Reads: Separate short reads into uniquely mapped and multi-mapped categories.

- Initialization: Calculate initial transcript proportions (θ) and multi-map reassignment priors (π) from the short-read data.

- Long-read informed EM: Integrate Transcripts Per Million (TPM) values from the long-read data as a prior in the maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimation during the EM algorithm's M-step. This guides the reassignment of multi-mapped short reads towards loci supported by long-read evidence.

- Iterate: Repeat the E- and M-steps until model parameters converge.

- Final Quantification: Output a final, updated alignment file with resolved read counts for each individual TE locus.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the LocusMasterTE process:

Issue: High Multi-Mapping Rates in Standard RNA-seq Analysis

Problem: A large proportion of your RNA-seq reads are multi-mapping, leading to poor gene and TE quantification.

Explanation: This is a common issue when analyzing samples with high TE activity or when using a reference genome that does not adequately represent the repetitive content of your sample [11]. Standard aligners assign a mapping quality of zero to these reads, and they are often ignored.

Solution:

- Use longer sequencing reads: If starting a new experiment, consider using 150 bp paired-end reads instead of shorter ones. The longer the read, the higher the probability it will include a unique sequence that allows for unambiguous mapping [7].

- Choose an appropriate reference genome: Ensure you are using the most complete reference genome available (e.g., T2T-CHM13), as older references have gaps and collapsed repeats that exacerbate multi-mapping problems [11].

- Employ a multi-mapping aware pipeline: Adopt a pipeline like TE-Seq, which is specifically designed to handle these challenges. It combines strategies for dealing with multi-mapping reads, annotating genic context, and incorporating non-reference TEs [9].

Experimental Protocol: Comprehensive TE Analysis with the TE-Seq Pipeline

- Principle: The TE-Seq pipeline provides an end-to-end solution for RNA-seq data that examines both genes and TEs, addressing multi-mapping, non-reference elements, and genic context [9].

- Inputs: RNA-seq data (short-read or long-read), and optional long-read DNA-seq data.

- Method:

- Identify Non-Reference TEs (Optional but Recommended):

- Perform long-read DNA sequencing on your sample.

- Use the TLDR tool to call non-reference TE insertions.

- Apply quality filters to generate a high-confidence set of sample-specific TE insertions.

- Create a Custom Genome:

- Inject the quality-filtered non-reference TE insertions into a baseline reference genome (e.g., T2T) to create a personalized, "TE-complete" genome for your sample.

- RNA-seq Alignment and Quantification:

- Map your RNA-seq reads (both short and long) to the custom genome.

- Use a tool like Telescope (which uses an EM algorithm) to quantify TE expression at the locus-specific level, leveraging the improved mappability of the custom genome.

- Annotate Genic Context:

- Categorize each TE based on its spatial relationship to known genes (e.g., intergenic, intronic, exonic). This helps distinguish autonomous TE transcription from passive read-through from gene promoters.

- Identify Non-Reference TEs (Optional but Recommended):

The following workflow diagram illustrates the TE-Seq process:

Data Presentation: Comparison of Mapping and Analytical Strategies

The table below summarizes key quantitative data and characteristics of different approaches to handling repetitive sequences.

Table 1: Comparison of Strategies for Analyzing Repetitive Elements

| Strategy / Tool | Core Methodology | Advantages | Limitations / Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Unique Mapping | Discards all multi-mapped reads. | Simple; provides unambiguous positional information [7]. | Strongly biased against young TEs and other repetitive sequences; can miss up to 30% of transcriptional activity [7] [9]. |

| Multi-Mapping (Family-Level) | Pools reads mapping to any member of a TE family. | Provides an overview of total family activity; useful for shallow sequencing data (e.g., scRNA-seq) [7]. | Loses all locus-specific information [7]. |

| EM-Based Algorithms (e.g., Telescope, TEtools) | Uses an expectation-maximization algorithm to probabilistically assign multi-mapped reads to a most likely locus. | Enables locus-specific quantification; more accurate than random assignment [9] [10]. | Can fail for highly identical young TEs (~6% of cases) where information is insufficient [10]. |

| Long-Read Sequencing (e.g., ONT, PacBio) | Sequences fragments that are thousands of base pairs long. | Dramatically reduces multi-mapping; allows for direct sequencing of full-length TE transcripts [7] [10]. | Higher cost per base; lower throughput can miss lowly expressed TEs; requires specialized data analysis [7]. |

| Hybrid Methods (e.g., LocusMasterTE) | Integrates long-read data as a prior to guide EM reassignment of short-reads. | Maximizes accuracy by combining the depth of short-reads with the mappability of long-reads [10]. | Requires matched long-read data for optimal performance. |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for TE Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| T2T (Telomere-to-Telomere) Genome | Reference Genome | A more complete human reference genome that closes gaps and better represents repetitive regions, reducing mapping ambiguity [9] [11]. |

| Dfam | Curated Database | A community resource of transposable element families, sequence models, and genome annotations, used for accurate TE annotation [7]. |

| TLDR | Software Tool | Used with long-read DNA sequencing data to call non-reference, polymorphic TE insertions in a specific sample [9]. |

| BRB-seq | Library Prep Technology | An ultra-affordable, high-throughput 3' RNA-seq method that allows for massive multiplexing, useful for large-scale expression screening [12]. |

| Nexco TEnex Database | Curated Database | A highly accurate, curated database containing comprehensive TE annotations, genomic locations, and sequences, used in over 30 high-impact publications [7]. |

FAQ: What is the link between alternative splicing and multi-mapped reads in RNA-seq?

Alternative splicing (AS) is a post-transcriptional regulatory mechanism that allows a single gene to produce multiple distinct mRNA transcripts, or isoforms, by selectively combining exons and introns [13]. This process is a major contributor to transcriptomic and proteomic diversity. When these different isoforms from the same gene share identical exonic sequences, they create repeated sequences within the transcriptome. During RNA-seq analysis, short sequencing reads derived from these shared exons can align equally well to multiple genomic locations corresponding to all the isoforms that contain that exon. These are known as multi-mapped reads or multireads [2]. This ambiguity poses a significant challenge for accurately quantifying the expression of individual transcripts.

FAQ: How prevalent is alternative splicing?

Alternative splicing is widespread in eukaryotes, though its prevalence varies across taxonomic groups [13]. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from various studies:

Table 1: Prevalence of Alternative Splicing Across Species

| Species/Group | Proportion of Genes with AS | Key Findings and Context |

|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana (Plants) | ~61% of multiexonic genes [14] | Found under normal growth conditions using a normalized cDNA library and RNA-seq. |

| Human (Mammals) | Up to ~95% of multiexon protein-coding genes [15] | Contributes to ~37% of protein-coding genes producing more than one protein variant. |

| Mammals & Birds | Highest levels of AS [13] | Considerable interspecies divergence in splicing activity is observed. |

| Plants | Moderate levels of AS [13] | Exhibit high variability in genomic composition; often compensate for lower AS rates through gene duplication. |

| Unicellular Eukaryotes & Prokaryotes | Minimal splicing [13] | Suggests AS is an advanced regulatory feature associated with multicellularity. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Multi-Mapped Reads

FAQ: A large proportion of my RNA-seq reads are multi-mapped. What should I do?

A high percentage of multi-mapped reads is a common challenge. The following workflow diagram outlines a systematic approach to diagnose and address this issue.

Step 1: Check Data Quality. Begin by examining raw read quality and the presence of over-represented sequences, which could indicate contamination (e.g., from rRNA). As one support case highlighted, a sequence present in 6.8% of reads was linked to rRNA, contributing significantly to multi-mapping [16]. Tools like FastQC and SortMeRNA can be used for this analysis [16].

Step 2: Identify Contamination. If a specific type of contamination is suspected, such as rRNA, you can filter these reads before realignment. Alternatively, after mapping, you can exclude reads that align to regions annotated as rRNA genes during the read counting step [16].

Step 3: Verify Reference and Annotation. Ensure you are using a high-quality, recent genome assembly and a comprehensive gene annotation file (GTF/GFF). Providing a gene annotation file to aligners like STAR or HISAT2 can significantly improve the accuracy of spliced alignment.

Step 4: Select a Quantification Strategy. The choice of how to handle the remaining multi-mapped reads is critical. Several computational strategies exist [2]:

- Ignore them: Discard multi-mapped reads. This is simple but loses information.

- Distribute them proportionally: Use tools that employ an expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm to probabilistically allocate multi-mapped reads to their most likely locus of origin, based on the abundance of uniquely mapped reads.

- Quantify at the gene-group level: For genes with high sequence similarity (e.g., paralogs), it may be more accurate to report expression for the entire gene family rather than for individual members.

The challenge of multi-mapped reads stems from both genomic and transcriptomic sequence duplication. The diagram below categorizes the main sources.

Table 2: Detailed Sources of Sequence Duplication

| Source | Mechanism | Affected Biotypes / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Paralogous Genes | Duplication of whole genes through unequal recombination or whole-genome duplication [2]. | Affects genes of any biotype, creating families of genes with high sequence similarity over their entire length. |

| Transposable Elements | "Copy and paste" mechanisms, particularly of retrotransposons, insert repetitive sequences throughout the genome [2]. | Mostly affects longer genes (e.g., protein-coding, lncRNA). These elements can be embedded within introns or exons. |

| Processed Pseudogenes | Cellular mRNAs are reverse-transcribed and reinserted into the genome, creating intron-less copies [2]. | These pseudogenes share high exon sequence identity with their parental protein-coding genes. |

| Alternative Splicing | A single gene produces multiple transcript isoforms that share common exons [2]. | Creates sequence duplication within the transcriptome, even if the genome sequence is unique. This is a pivotal source of multi-mapping for complex genes. |

Experimental Protocols & Reagents

Detailed Methodology: High-Throughput Sequencing of a Normalized cDNA Library for AS Discovery

This protocol is adapted from a key study that investigated transcriptome complexity in Arabidopsis thaliana [14].

Objective: To achieve a high-coverage transcriptome map and comprehensively identify alternative splicing events, including those from low-abundance transcripts.

Workflow:

Key Steps:

- RNA Isolation & Library Construction: Isolate total RNA from tissues of interest (e.g., seedlings and flowers). Construct a normalized cDNA library. Normalization is a critical step that reduces the abundance of highly expressed transcripts, thereby significantly improving the discovery power for rare transcripts [14].

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Subject the normalized library to paired-end sequencing (e.g., 75bp paired-end reads on the Illumina platform).

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Read Alignment: Map reads to the reference genome using a splice-aware aligner such as TopHat (which uses Bowtie) or STAR [14].

- Splice Junction (SJ) Detection: Use the aligner to identify canonical and non-canonical splice junctions. Apply stringent filters (e.g., minimum intron size of 60nt for plants) to reduce false positives [14].

- AS Quantification: Use tools like Whippet [15] to calculate metrics such as Percent Spliced-In (Ψ) and splicing entropy to quantify AS inclusion and complexity.

- Experimental Validation: Validate computational predictions using independent experimental methods such as high-resolution RT-PCR followed by Sanger sequencing of the amplified products [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for Investigating AS and Multi-Mapped Reads

| Item / Reagent | Function / Explanation | Example Tools / Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Normalized cDNA Library | Reduces the abundance of highly expressed transcripts, allowing for greater coverage and discovery of lowly expressed and alternatively spliced transcripts [14]. | Protocol in [14] |

| Splice-Aware Aligners | Software designed to map RNA-seq reads across splice junctions, which are not contiguous in the genome. | STAR [16], HISAT2 [16], TopHat [14] |

| Quantification Tools with EM | Tools that use statistical models to handle multi-mapped reads, probabilistically assigning them to likely transcripts. | Tools mentioned in [2] (e.g., RSEM) |

| Splicing Complexity Metrics | Metrics that go beyond simple exon inclusion/ exclusion to capture the diversity of transcripts produced by a single exon/gene. | Splicing Entropy (Shannon's entropy) [15], Alternative Splicing Ratio (ASR) [13] |

| High-Resolution RT-PCR | An independent, non-high-throughput method used to validate computationally predicted alternative splicing events. | Protocol in [14] |

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, a significant challenge is the accurate quantification of transcripts that originate from genomic regions with high sequence similarity. This guide addresses the specific issues related to multi-mapped reads—sequencing reads that align equally well to multiple locations in the genome—and their impact on the analysis of specific RNA biotypes, including ribosomal RNA (rRNA), pseudogenes, and various non-coding RNA families. Understanding and properly handling these reads is critical for avoiding biases in the functional interpretation of your data [17].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are multi-mapped reads and why do they cause problems? Multi-mapped reads arise because eukaryotic genomes contain large numbers of duplicated sequences. When short RNA-seq reads are generated from these regions, it becomes computationally difficult to unambiguously assign them to a single locus of origin. Standard analysis pipelines that ignore these reads can lead to a severe underestimation of expression for genes with highly similar paralogs or those embedded in repetitive elements [2] [17].

2. Which RNA biotypes are most affected by multi-mapping issues? RNA biotypes that are short, exist in large gene families, or are derived from repetitive elements are disproportionately affected. The table below summarizes the most vulnerable biotypes and the reasons for their susceptibility [2].

Table 1: RNA Biotypes Highly Affected by Multi-Mapped Reads

| RNA Biotype | Description | Reason for High Multi-Mapping |

|---|---|---|

| Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) | Structural RNAs that are key components of the ribosome. | Presence of hundreds to thousands of nearly identical genomic copies [2]. |

| Pseudogenes | Non-functional copies of protein-coding genes. | High sequence similarity to their parental protein-coding genes and other pseudogenes [2] [18]. |

| Small Nuclear RNA (snRNA) | Involved in pre-mRNA splicing. | Propagated through retrotransposition, leading to families of similar copies [2]. |

| Small Nucleolar RNA (snoRNA) | Guides modifications of rRNAs and other RNAs. | Often encoded in large, repetitive gene families spread throughout the genome [2]. |

| MicroRNA (miRNA) | Short RNAs that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally. | Many family members have high sequence similarity due to duplication and retrotransposition [2]. |

| Transposable Elements (TEs) | Mobile genetic elements. | Recent activity can create many highly similar genomic copies [17]. |

| Gene Families (e.g., Histones, Olfactory receptors, MHC genes) | Families of genes with related functions. | Individual members within a family can share very high sequence identity [2] [17]. |

3. What are the consequences of simply discarding multi-mapped reads? Discarding multi-mapped reads is the default in many standard pipelines, but this practice introduces systematic biases. It leads to the underrepresentation of recently active transposable elements and repetitive gene families in your data. For example, expression of genes in the Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) or histone families can be severely underestimated, skewing functional enrichment analyses and biological interpretations [17].

4. What strategies exist to handle multi-mapped reads? Several computational strategies have been developed to account for multi-mapped reads more effectively than simply discarding them. The choice of strategy can significantly impact your results [2] [19].

Table 2: Common Computational Strategies for Handling Multi-Mapped Reads

| Strategy | Method | Advantages / Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Ignore/Discard | Filter out all reads that do not map uniquely. | Simple; default for many pipelines. Severely biases against affected biotypes. |

| Proportional Assignment | Distribute reads among potential loci based on the abundance of unique reads for those loci. | More accurate for some biotypes. Assumes unique and multi-mapped reads have similar distributions, which may not be true [17]. |

| Equal Splitting | Split a multi-mapped read equally among all its possible loci of origin. | A simple acknowledging approach. May over- or under-estimate true expression. |

| Expectation-Maximization (EM) | Use statistical models to iteratively estimate the most probable transcript abundances and resolve read origins. | Can be highly accurate. Computationally intensive; results depend on model assumptions [2]. |

| Rescuing & Clustering | Group genes/transcripts with shared sequences or use flanking unique regions to rescue multi-mapped reads. | Can improve accuracy for complex gene families. Implementation can be complex [19]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Suspected Bias from Repetitive RNA Biotypes

Problem: Your differential expression analysis shows unexpected results, and you suspect that genes from repetitive families (e.g., histones, rRNA, MHC) are being inaccurately quantified due to multi-mapped reads.

Solution:

- Re-analyze with a multi-mapper-aware pipeline: Reprocess your raw sequencing data using a tool that implements one of the strategies in Table 2 (e.g., EM or proportional assignment). Many modern alignment and quantification tools have built-in options for handling multi-mappers.

- Compare results: Perform a differential expression analysis on the new counts and compare the list of significant genes with your original analysis. Pay special attention to the expression levels of the affected biotypes.

- Validate findings: Use an alternative method (e.g., qPCR) to confirm the expression levels of key genes from repetitive families that show differential expression in the new analysis.

Issue: High rRNA Contamination Despite Ribodepletion

Problem: Your RNA-seq data shows a high and unbalanced percentage of reads mapping to rRNA between sample groups, even after a ribodepletion protocol.

Solution:

- Remove rRNA reads computationally: Align your raw FASTQ reads to a reference database of rRNA sequences (e.g., using Bowtie2) and discard all reads that align. This prevents these reads from being misassigned to protein-coding genes during genome mapping [20].

- Proceed with standard analysis: Use the filtered reads for your downstream alignment and quantification. There is typically no need to include the initial rRNA percentage as a covariate in your model, as this variation can be considered part of the technical or biological variance [20].

- Check sequencing depth: After rRNA removal, ensure that all samples still have sufficient sequencing depth for reliable quantification.

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In-silico Removal of Ribosomal RNA Reads

Purpose: To computationally remove reads derived from ribosomal RNA before genome alignment, preventing their misassignment and improving the accuracy of transcript quantification.

Methodology:

- Obtain rRNA Sequences: Download a comprehensive set of rRNA sequences for your organism from databases like SILVA or RDP.

- Build an rRNA Index: Use a read aligner like Bowtie2 to build a dedicated index from these rRNA sequences.

- Align and Filter: Align your raw sequencing reads (in FASTQ format) to the rRNA index. Discard all reads that successfully align.

- Retain Non-rRNA Reads: The reads that did not align to rRNA are your purified dataset. Use these reads for all subsequent alignment and quantification steps against the reference genome/transcriptome [20].

Protocol 2: A Recommended RNA-seq Analysis Workflow Accounting for Multi-Mappers

Purpose: To outline a robust RNA-seq data analysis workflow that incorporates best practices for handling multi-mapped reads from start to finish.

Methodology:

- Quality Control & Trimming: Assess raw read quality with FastQC and trim adapters/low-quality bases with tools like Cutadapt or Trimmomatic.

- rRNA Removal (Optional but Recommended): Perform in-silico rRNA removal as described in Protocol 1.

- Alignment to Genome: Align reads to the reference genome using a splice-aware aligner (e.g., STAR).

- Quantification with Multi-Mapper Handling: Generate transcript or gene-level counts using a tool that can model multi-mapped reads, such as:

- Salmon or kallisto (pseudoalignment-based tools that use EM algorithms to probabilistically assign reads).

- featureCounts (can be run with options to count multi-mapping reads proportionally).

- Avoid tools that discard multi-mappers by default unless you have confirmed they do not impact your genes of interest [2] [17].

- Differential Expression & Interpretation: Perform differential expression analysis with tools like DESeq2 or edgeR, using the count data generated in the previous step.

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 1: Robust RNA-seq analysis workflow. Key steps for handling problematic biotypes are highlighted in green.

Diagram 2: Common strategies for handling a single multi-mapped read.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq Analysis

| Item / Resource | Function | Example Tools / Databases |

|---|---|---|

| Splice-aware Aligner | Aligns RNA-seq reads to a reference genome, accounting for introns. | STAR, HISAT2 |

| Quantification Tool with Multi-Mapper Support | Estimates gene/transcript abundance using strategies that account for multi-mapped reads. | Salmon, kallisto, featureCounts (with appropriate parameters) |

| rRNA Sequence Database | Provides a reference set for computationally removing rRNA contaminants. | SILVA, RDP |

| Functional Annotation Database | Helps interpret the biological meaning of differential expression results. | Gene Ontology (GO), Reactome, DAVID |

| Integrated Analysis Platforms | User-friendly, cloud-based platforms that often bundle multiple analysis steps. | Illumina DRAGEN/BaseSpace, Galaxy, Partek Flow [21] [22] |

A significant challenge in RNA-Seq data analysis is the handling of sequencing reads that align equally well to multiple locations in the reference genome, known as multi-mapped (or multimapping) reads. These reads arise from the presence of duplicated genomic sequences and present substantial difficulties for accurate transcript quantification. In eukaryotic genomes, large numbers of duplicated sequences result from diverse mechanisms including recombination, whole genome duplication, and retro-transposition [2]. The proportion of multi-mapped reads is not trivial; depending on the organism, sample, and experimental protocol, typically 5-40% of total reads mapped may be multi-mapped [2]. This substantial subset of reads, if not handled properly, can introduce significant biases in downstream analysis and functional interpretation [17].

The challenge is further compounded by the fact that different RNA biotypes exhibit varying levels of sequence duplication. RNA biotypes such as rRNA, pseudogene, snRNA, snoRNA, and miRNA show the largest proportion of members with sequence similarity to other genes [2]. Long-noncoding RNAs and messenger RNAs generally share less sequence similarity to other genes than biotypes encoding shorter RNAs [2]. Understanding these patterns is crucial for accurate interpretation of RNA-Seq data, particularly for studies focusing on these specific RNA classes.

Quantifying the Problem: Typical Proportions of Multi-Mapped Reads

Expected Proportions Across Experimental Conditions

The proportion of multi-mapped reads varies substantially based on experimental parameters, with typical ranges observable under different conditions:

Table 1: Typical Proportions of Multi-Mapped Reads in RNA-Seq Experiments

| Experimental Condition | Typical Multi-Mapping Proportion | Primary Contributing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Standard human RNA-Seq (STAR) | 5-15% [23] | Duplicated gene families, pseudogenes |

| Ribodepleted, paired-end (STAR) | ~8% [23] | Effective rRNA reduction |

| Total RNA-Seq with rRNA contamination | 30-40% [24] | High rRNA content, multi-copy genes |

| Studies of repetitive elements | 20-30% (Bowtie2) [23] | Transposable elements, tandem repeats |

These proportions are influenced by multiple factors, with ribosomal RNA content being a major determinant. Incomplete rRNA depletion can dramatically increase multi-mapping rates, as rRNA genes are present in multiple copies throughout the genome [24]. One researcher reported that after investigating overrepresented sequences in their data, "most of them came from rRNA," indicating that incomplete depletion of rRNA was a significant contributor to their observed 30-40% multi-mapping rate [24].

The choice of alignment software also significantly affects reported multi-mapping rates. STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) and Bowtie2 may report different percentages for the same dataset, with Bowtie2 typically reporting higher multi-mapping rates [23]. This discrepancy arises from fundamental algorithmic differences: STAR is splice-aware, while Bowtie2 is not, leading to different mapping capabilities for spliced reads [23].

Impact on Gene Expression Analysis

The systematic exclusion of multi-mapped reads introduces substantial biases in functional assessment of NGS data. Genomic elements belonging to clusters of highly similar members are consistently underrepresented when multi-mapped reads are discarded [17]. This practice particularly affects:

- Recently active transposable elements such as AluYa5, L1HS, and SVAs in epigenetic studies [17]

- Repetitive gene families including major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and II genes [17]

- Ubiquitin B family genes, where up to 97% of reads may be multi-mapped [17]

This underrepresentation has profound implications for biological interpretation. Studies have shown that disregarding multimappers leads to the underrepresentation of recently active transposable elements and repetitive gene families in functional enrichment analyses [17]. Consequently, the reliability of genomic and transcriptomic studies is compromised when standard pipelines that filter out multi-mapped reads are employed.

Biological Origins of Multi-Mapped Reads

Multiple molecular mechanisms contribute to the sequence duplication that gives rise to multi-mapped reads:

Recombination and Whole Genome Duplication: Unequal crossing-over during recombination can lead to tandem gene duplication, while ectopic recombination between non-homologous loci can result in sequence duplication [2]. Whole genome duplication events, evidenced in diverse lineages including yeast, chordates, and plants, also contribute significantly to sequence redundancy [2].

Transposable Elements: Approximately half to two-thirds of the human genome consists of transposons, which propagate via "cut and paste" or "copy and paste" mechanisms [2]. Retrotransposition machinery can use cellular RNAs as substrates, reverse transcribing and inserting them into the genome, leading to new copies of existing genes [2].

Processed Pseudogenes: Genes resulting from the retrotransposition of messenger RNAs are referred to as processed pseudogenes, which lack the introns of their parental copy but share exonic sequence identity [2].

Noncoding RNA Propagation: Many noncoding RNA families including small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs), small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs), and miRNAs derive many of their members through retrotransposition, resulting in significant sequence redundancy [2].

Beyond genomic duplication, transcript-level phenomena also contribute to multi-mapping:

Alternative Splicing: The use of alternative exons and promoters increases transcript diversity, resulting in multiple transcripts from the same gene with overlapping sequences [2]. When RNA-seq reads are aligned to a transcriptome rather than a genome, these overlapping transcripts appear as duplicated sequences in the reference [2].

Gene Families with High Sequence Similarity: Certain gene families naturally exhibit strong sequence conservation among members, including globin genes, homeobox genes, and olfactory receptors [17]. These families present particular challenges for unique read assignment.

Figure 1: Biological Sources and Computational Handling of Multi-Mapped Reads

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing High Multi-Mapping Rates

Diagnostic Procedures

When encountering unexpectedly high proportions of multi-mapped reads (>30%), researchers should systematically investigate potential causes:

Assess rRNA Contamination

Evaluate Adapter Content

Verify Reference Genome and Annotations

Inspect Read Quality and Length

Mitigation Strategies

Experimental Design Solutions

- Optimize rRNA depletion protocols during library preparation

- Consider poly(A) selection for mRNA enrichment

- Increase read length where possible to reduce mapping ambiguity

Computational Adjustments

Computational Strategies for Multi-Mapped Read Handling

Available Computational Approaches

Several computational strategies have been developed to handle multi-mapped reads, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Table 2: Computational Strategies for Handling Multi-Mapped Reads

| Strategy | Representative Tools | Methodology | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discard multi-mappers | Default in HTSeq-count, featureCounts [28] | Simply ignores multi-mapped reads | Simple implementation, avoids false positives | Biased against repetitive elements, loss of information [17] |

| Uniform distribution | Basic implementations | Divides multi-mapped reads equally among potential loci | Uses all sequencing data | Can inflate counts for non-expressed paralogs |

| Proportional weighting | Some featureCounts options [28] | Distributes reads based on unique mapping evidence | Uses evidence from unique mappers | Assumes similar coverage distribution |

| Expectation-Maximization (EM) | RSEM, Cufflinks [2] | Iteratively estimates transcript abundances | Statistical rigor, comprehensive model | Computationally intensive, makes distribution assumptions |

| Gene merging | mmquant [28] | Creates merged genes for unresolved ambiguities | Handles true duplicates appropriately | Creates new "genes" not in original annotation |

| Multi-mapper aware quantification | mmquant, specific pipelines [28] | Resolves ambiguities using overlapping bases and intron information | Unbiased handling of duplicates [28] | Requires sorted BAM files, additional computation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Essential Tools for Multi-Mapper Aware RNA-Seq Analysis

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features for Multi-Mapping |

|---|---|---|---|

| STAR [27] | Aligner | Spliced alignment of RNA-seq reads | Reports multi-mapping counts, configurable maximum loci |

| mmquant [28] | Quantification | Gene-level counting | Creates merged genes for ambiguous reads |

| featureCounts [28] | Quantification | Read assignment to features | Options for handling multi-mapping reads (-M -O) |

| HTSeq-count [28] | Quantification | Read counting with Python | Multiple overlap resolution modes |

| FastQC [24] | Quality Control | Sequencing data quality assessment | Identifies overrepresented sequences |

| CutAdapt [24] | Preprocessing | Adapter trimming | Removes adapter contamination that affects mapping |

| SortMeRNA [24] | Preprocessing | rRNA removal | Identifies ribosomal RNA sequences |

| SAMtools [26] | Utilities | BAM file manipulation | Filters reads by mapping quality flags |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is considered a "typical" percentage of multi-mapped reads in human RNA-Seq? A: For standard human RNA-Seq data aligned with STAR, typical multi-mapping rates range from 5-15% [23]. However, this varies significantly with experimental conditions. Ribodepleted samples may show ~8% multi-mappers, while total RNA samples with inefficient rRNA depletion can exhibit 30-40% multi-mapping rates [24] [23].

Q: Why do different aligners (STAR vs. Bowtie2) report different multi-mapping percentages? A: STAR is splice-aware, meaning it can properly handle reads spanning exon-exon junctions, while Bowtie2 is not designed for spliced alignment [23]. This fundamental difference leads Bowtie2 to report higher multi-mapping rates (20-30%) for the same dataset where STAR might report 5-15% [23]. The choice of aligner should be guided by the specific analytical needs.

Q: How can I determine if high multi-mapping is due to rRNA contamination? A: First, run FastQC to identify overrepresented sequences [24]. Then, extract these sequences and BLAST them against an rRNA database [24]. For higher throughput analysis, extract multi-mapped reads from your BAM file, convert to FASTQ format, and BLAST them against an rRNA database or use specialized tools like SortMeRNA [24].

Q: Should I include multi-mapped reads in differential expression analysis? A: The standard practice has been to discard multi-mapped reads, but this introduces biases against repetitive genomic elements [17]. More sophisticated approaches using expectation-maximization algorithms or gene merging strategies (e.g., mmquant) can provide more accurate quantification [28] [29]. The choice depends on your biological question - if repetitive elements or duplicated gene families are of interest, multi-mapper-aware approaches are essential.

Q: What are the implications of discarding multi-mapped reads for functional interpretation? A: Disregarding multimappers leads to systematic underrepresentation of recently active transposable elements (e.g., AluYa5, L1HS) and repetitive gene families (e.g., MHC classes I and II) in functional assessments [17]. This bias can significantly impact the biological conclusions drawn from enrichment analyses, potentially missing important biological phenomena occurring in repetitive genomic regions.

Q: Are there specific RNA biotypes more affected by multi-mapping issues? A: Yes, RNA biotypes with high sequence similarity include rRNA, pseudogenes, snRNA, snoRNA, and miRNA [2]. These biotypes show the largest proportion of members with sequence similarity to other genes, making them particularly susceptible to multi-mapping and quantification challenges when standard discard approaches are used.

From Theory to Practice: Computational Strategies for Multi-Mapper Resolution

In RNA-seq data analysis, a significant challenge arises from multi-mapped reads—sequence reads that align equally well to multiple locations in a reference genome. This is common in eukaryotic genomes due to duplicated sequences, gene families, and repetitive elements [30]. How these reads are handled can profoundly impact the accuracy of gene and transcript quantification. This guide outlines the three primary computational strategies—Ignoring, Distributing, and Resolving—providing a foundational framework for researchers to navigate their experimental choices.

The table below summarizes the core concepts, typical use cases, and key trade-offs of each primary approach.

| Approach | Core Principle | Typical Use Cases | Key Advantages & Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ignoring | Discards multi-mapped reads from the analysis [30]. | - Analyses requiring high stringency- Genomes with low duplication levels | Advantage: Simple to implement; avoids mis-assignment.Disadvantage: Can lead to a significant loss of data and underestimate expression of duplicated genes. |

| Distributing | Probabilistically assigns multi-mapped reads to their possible loci of origin [30]. | - Standard gene/transcript quantification- Studies of gene families or duplicated regions | Advantage: Utilizes all sequencing data; provides more accurate abundance estimates for multi-mapped regions.Disadvantage: Relies on accurate initial estimation; can be computationally intensive. |

| Resolving | Uses additional information (e.g., sequence-specific biases, paired-end reads, splice patterns) to uniquely place ambiguous reads [30]. | - Precise isoform-level quantification- Complex genomes with high duplication | Advantage: Can improve quantification accuracy by leveraging more data.Disadvantage: Highly complex; success depends on the quality and nature of the additional information. |

Computational Workflow for Handling Multi-Mapped Reads

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental and computational workflow for processing RNA-seq data, integrating the three primary approaches to multi-mapped reads.

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Approach 1: Ignoring Multi-Mapped Reads

Experimental Protocol: This is often the default in simpler quantification pipelines. After alignment with tools like STAR or HISAT2, the resulting BAM file is filtered using tools like SAMtools to exclude reads with mapping quality (MAPQ) scores below a specific threshold (e.g., MAPQ < 10). The remaining "uniquely mapped" reads are then used for quantification with tools like featureCounts or HTSeq-count.

Approach 2: Distributing Multi-Mapped Reads

Experimental Protocol: This approach is typically implemented within advanced quantification tools that use an expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm [30]. The protocol involves aligning reads with a sensitive aligner and then directly inputting the entire BAM file (including multi-mapped reads) into quantification tools like Salmon or RSEM. These tools run an iterative process where they:

- E-step: Estimate transcript abundances based on current read assignments.

- M-step: Re-assign multi-mapped reads to transcripts probabilistically, weighted by the current abundance estimates.

- Iterate: Repeat steps 1 and 2 until the abundance estimates converge.

Approach 3: Resolving Multi-Mapped Reads

Experimental Protocol: Resolving reads requires leveraging additional contextual information. A common protocol utilizes paired-end reads and splice-aware alignment. When one read in a pair is uniquely mapped and the other is multi-mapped, the unique read's position can be used to resolve its partner's location. Tools like STAR or Subread incorporate this logic during alignment. The experimental design is critical: using paired-end sequencing with sufficient read length is a prerequisite for this method to be effective.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational tools and resources essential for implementing the approaches described above.

| Tool/Resource Name | Primary Function | Brief Description of Role |

|---|---|---|

| STAR | Spliced Transcriptome Alignment | A popular aligner that identifies multi-mapped reads and can use paired-end information to help resolve them [30]. |

| Salmon | Transcript Quantification | Uses a selective alignment strategy and an EM algorithm to probabilistically distribute reads (including multi-mapped ones) across transcripts [30]. |

| RSEM | Transcript Quantification | A widely used tool that employs an EM algorithm for the probabilistic assignment of multi-mapped reads during quantification [30]. |

| featureCounts | Read Quantification | A common tool for counting reads that can be set to either ignore or probabilistically count multi-mapping reads. |

| SAMtools | SAM/BAM File Processing | A suite of utilities for manipulating alignments, including filtering reads by mapping quality to effectively "ignore" multi-mapped reads. |

| Expectation-Maximization (EM) Algorithm | Computational Method | The core statistical engine used by many quantifiers to iteratively resolve read assignment ambiguities [30]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Which approach should I use for my RNA-seq experiment? The choice depends on your biological question and genome complexity. For a first-pass analysis or in genomes with low duplication, Ignoring provides simplicity. For most standard analyses, especially in complex genomes, Distributing (using tools like Salmon or RSEM) is recommended as it uses all your data. If you have high-quality paired-end reads and are studying specific gene families, Resolving can offer improved accuracy.

Q2: What are the key considerations for designing my RNA-seq experiment to handle multi-mapped reads effectively? A well-designed experiment is crucial [31]. Key considerations include:

- Library Type: Use paired-end sequencing whenever possible, as the additional information is critical for resolving multi-mapped reads.

- Read Length: Longer reads are more likely to span unique sequences, reducing ambiguity.

- Sequencing Depth: Higher depth provides more data for probabilistic models to converge on accurate estimates.

Q3: My genome has a high number of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs). How does this affect my choice? LncRNAs, along with other non-coding biotypes, often have lower sequence similarity to other genes compared to protein-coding mRNAs [30]. This means the Distributing approach is generally well-suited, as the risk of mis-assignment between lncRNAs and other genes may be lower. However, you should always validate findings with independent methods.

Q4: Can I use a combination of these approaches? Yes, hybrid strategies are possible. For example, you might use a stringent Resolving step for reads that can be uniquely placed with high confidence, and then use a Distributing approach for the remaining ambiguous reads. Some advanced computational tools implement such multi-stage strategies.

Expectation-Maximization Algorithms in Pseudo-Alignment Tools

Conceptual Foundations

What is the core function of the Expectation-Maximization algorithm in handling multi-mapped reads?

The Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm addresses a fundamental challenge in RNA-seq analysis: the multiple mapping problem, where reads map to several transcripts due to sequence similarity among genes or isoforms [32]. The EM algorithm iteratively estimates transcript abundances by probabilistically assigning multi-mapped reads.

The process begins with an initial estimate of transcript abundances (ρ). In the Expectation (E-step), the algorithm calculates the probability that each read originates from each transcript it aligns to, given the current abundance estimates [33] [32]. In the Maximization (M-step), these probabilities are used as weights to update the abundance estimates [33] [32]. This two-step process repeats until the abundance estimates converge, effectively resolving the ambiguity of multi-mapped reads through statistical inference [30] [6] [32].

How does pseudoalignment differ from traditional alignment, and why is it faster?

Pseudoalignment significantly accelerates RNA-seq analysis by determining transcript compatibility without performing base-by-base alignment [34] [35].

Traditional alignment tools perform computationally intensive base-to-base alignment of each read to a reference genome or transcriptome to determine the exact mapping coordinates [35]. In contrast, pseudoalignment only determines which transcripts a read is compatible with, without specifying exact base-level coordinates [34] [35]. This is achieved using a transcriptome de Bruijn graph (T-DBG) where k-mers from reads are hashed to identify compatible transcripts through set intersections [34].

The speed advantage comes from several factors: pseudoalignment avoids the costly alignment step, uses efficient k-mer hashing with a pre-built index, and skips redundant k-mers that share the same compatibility class [34] [35]. For example, kallisto can quantify 78.6 million RNA-seq reads in approximately 14 minutes on a standard desktop computer, compared to hours required by traditional alignment-based methods [35].

Troubleshooting Guides

Why does my EM algorithm implementation show unstable convergence or increasing likelihood?

EM algorithm instability typically manifests as the log-likelihood decreasing initially but then increasing or fluctuating erratically. Based on implementation experiences, this issue stems from several potential causes:

- Numerical stability problems: The most common cause is issues with floating-point precision when dealing with extremely small probabilities [36]. This occurs when combining numbers of very different scales or when probabilities approach zero.

- Incorrect likelihood or gradient calculations: Errors in implementing the mathematical formulae for likelihood calculations or their derivatives can cause divergent behavior [36].

- Improper initialization: Poor initial parameter values may lead the algorithm toward poor local optima or unstable regions of the parameter space.

A specific implementation issue was observed where variance parameters shrank to zero prematurely. In one case, modifying the exponent in the probability calculation from -0.5 to -0.3 resolved the problem, though this represents a deviation from the theoretical formulation [37].

How can I resolve "variance shrinkage to zero" in my Gaussian Mixture Model implementation?

Variance shrinkage to zero is a known issue in EM implementations for Gaussian Mixture Models, where component variances collapse during iteration, causing the algorithm to converge incorrectly around the mean [37]. Solutions include:

- Implementation verification: Carefully check the covariance matrix update calculations in the M-step, particularly the normalization by probability sums [37].

- Add variance constraints: Implement minimum variance thresholds to prevent collapse.

- Review probability calculations: Verify the correctness of the probability density function implementation, especially the exponent term and normalization factors [37].

- Initialization diversity: Ensure initial parameters provide sufficient diversity across components.

Performance and Validation

How do pseudoalignment tools with EM algorithms compare to traditional aligners in performance?

Comparative studies demonstrate that pseudoalignment tools provide highly consistent results with traditional alignment methods while offering significant speed advantages. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from empirical evaluations:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of RNA-seq Alignment and Quantification Tools

| Tool | Methodology | Mapping Rate | Speed | Correlation with Traditional Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kallisto | Pseudoalignment | 92.4-98.1% [38] | ~14 min for 78.6M reads [35] | 0.997 (vs. salmon) [38] |

| salmon | Quasi-mapping | 92.4-98.1% [38] | Comparable to kallisto [38] | 0.997 (vs. kallisto) [38] |

| HISAT2 | Splice-aware alignment | 95.9-99.5% [38] | Slower than pseudoaligners [38] | 0.977-0.978 [38] |

| STAR | Splice-aware alignment | 95.9-99.5% [38] | Slower than pseudoaligners [38] | 0.977-0.978 [38] |

| RSEM | EM-based quantification | 95.9-99.5% [38] | Alignment-dependent [38] [39] | High correlation with other methods [38] |

In differential gene expression analysis, pseudoalignment tools show 92-98% overlap in identified differentially expressed genes compared to traditional aligners, demonstrating their reliability for downstream analysis [38].

What are the limitations of pseudoalignment tools, and when should I consider traditional alignment?

Despite their advantages, pseudoalignment tools have specific limitations:

- Accuracy with lowly-expressed transcripts: Studies indicate that accurate quantification of lowly-expressed genes remains challenging with pseudoalignment tools [35].

- Small RNA quantification: The short length of small RNAs makes them less suitable for k-mer-based approaches [35] [6].

- Variant detection: Pseudoalignment tools are designed for quantification, not for identifying sequence variants or novel isoforms.

- Sequence polymorphism effects: Mapping rates decrease slightly with increased sequence polymorphisms compared to the reference [38].

Consider traditional alignment when working with small RNAs, detecting sequence variants, discovering novel transcripts, or analyzing highly polymorphic samples where k-mer exact matching may fail.

Experimental Protocols

What is the standard workflow for transcript quantification using kallisto?

The kallisto workflow implements the EM algorithm for transcript quantification through pseudoalignment. Below is the standard protocol:

Table 2: Standard kallisto Workflow for Transcript Quantification

| Step | Command/Action | Parameters | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Index Building | kallisto index -i index_name transcriptome.fa |

k-mer length: 31 (default) [34] | kallisto index file |

| 2. Quantification | kallisto quant -i index -o output read1.fastq read2.fastq |

--bias (sequence bias correction), -b (bootstrap samples) [34] |

abundance estimates |

| 3. Bootstrap | kallisto quant -i index -o output -b 100 read1.fastq read2.fastq |

-b 100 (100 bootstrap samples) [35] |

uncertainty estimates |

The typical execution time for quantifying 92 million reads is approximately one hour on standard hardware, including bias correction and bootstrapping [34].

How can I visualize the uncertainty in abundance estimates using bootstrapping?

Bootstrapping provides confidence intervals for abundance estimates by resampling reads and recalculating abundances [35]. The workflow can be visualized as follows:

Bootstrapping Uncertainty Estimation Workflow

Kallisto efficiently implements bootstrapping by rerunning only the fast EM algorithm on resampled data, not the time-consuming pseudoalignment step [35]. This generates empirical confidence intervals for transcript abundance estimates, which is particularly valuable for low-abundance transcripts where estimation uncertainty is higher.

Technical Specifications

What are the key computational structures in pseudoalignment?

The efficiency of pseudoalignment stems from specialized data structures:

- Transcriptome de Bruijn Graph (T-DBG): Built from all k-mers in the transcriptome, where nodes represent k-mers and edges represent overlapping sequences [34].

- K-compatibility classes: Each k-mer is associated with the set of transcripts containing it [34].

- Equivalence classes: Sets of reads that are compatible with the same set of transcripts, reducing computational redundancy [34] [32].

The relationship between these structures can be visualized as:

Pseudoalignment Computational Structures

What are the essential research reagents and computational solutions for EM-based RNA-seq analysis?

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for EM-based RNA-seq Analysis

| Resource Type | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudoalignment Tools | kallisto [34] [35], salmon [38] | Fast transcript quantification | Large-scale RNA-seq studies requiring rapid processing |

| Traditional Aligners | HISAT2 [38], STAR [38], BWA [38] | Comprehensive read alignment | Studies requiring variant calling or novel isoform detection |

| EM Quantification | RSEM [38] [39] | Expectation-Maximization based quantification | Precise abundance estimation from alignment files |

| Differential Expression | DESeq2 [38], CLC Genomics Workbench [38] | Statistical analysis of expression differences | Identifying significantly regulated genes between conditions |

| Reference Databases | Ensembl, RefSeq [39] | Reference transcriptomes | Providing annotation for alignment and quantification |

The optimal tool selection depends on research goals: pseudoalignment tools for rapid quantification of known transcripts, traditional aligners for discovery-based applications, and EM-based methods for resolving multi-mapped reads.

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, a significant challenge arises from multi-mapped reads—sequence reads that align equally well to multiple locations in a reference genome. This occurs primarily in eukaryotic genomes containing large numbers of duplicated sequences resulting from mechanisms such as recombination, whole genome duplication, and retro-transposition [30] [6]. These multi-mapped reads complicate accurate gene and transcript quantification, as they can ambiguously originate from different genomic loci, sometimes involving genes embedded within other genes [30].

The handling of these multi-mapped reads is crucial for deriving biologically meaningful results from RNA-seq experiments, particularly in differential expression analysis. This technical support article explores two computational strategies—the Most-Voting strategy and Bayesian inference methods—for resolving multi-mapped reads, providing troubleshooting guidance and methodological frameworks for researchers addressing this challenge.

Most-Voting Strategy

Core Concept and Implementation

The Most-Voting strategy, implemented in tools like mmquant, addresses multi-mapped reads by identifying reads that map to multiple positions and detecting that the corresponding genes are duplicated [28]. The approach involves creating a new "merged gene" entity, with ambiguous reads counted based on both the original input genes and these newly created merged genes [28].

When a read maps to gene A and gene B, mmquant creates a merged gene designated as "gene A–B" [28]. This merged gene is then treated as a standard entity in downstream analyses, allowing the tool to utilize all information from ambiguous reads without introducing bias through uniform distribution or complete dismissal of multi-mapped reads [28].

Quantitative Comparison of Quantification Tools

The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of different quantification approaches when handling multi-mapped reads:

Table 1: Comparison of RNA-seq Quantification Tools Handling Multi-Mapped Reads

| Tool | Handling of Multi-Mapped Reads | Differentially Expressed Genes Identified | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| mmquant | Creates "merged genes" for ambiguous reads | 763 genes + 254 merged genes (in bipolar disorder study) [28] | Uses all multi-mapping information without assumption or inference [28] |

| htseq-count | Discards ambiguous reads in "union" mode | 734 genes (in bipolar disorder study) [28] | Recommended "union" mode considers reads ambiguous if overlapping two genes [28] |

| featureCounts | Discards multi-matching reads by default (can use with options) | 835 genes (in bipolar disorder study) [28] | Requires reads to be fully included in gene; options available but discouraged [28] |

Workflow Diagram: Most-Voting Strategy

Bayesian Inference Strategies

Hierarchical Bayesian Modeling

Bayesian approaches offer a powerful alternative for handling multi-mapped reads through hierarchical modeling that borrows information across positions, genes, and replicates [40]. These methods implement coherent, fast, and robust inference by modeling position-level read counts to infer differential expression at the gene level [40].

A key advantage of Bayesian hierarchical models is their ability to automatically discount outliers at the level of positions within genes, providing more accurate summaries of gene expression without predetermined assumptions about non-differential expression ratios [40]. These models can naturally account for technical artifacts and biases without requiring extensive pre-processing or normalization steps that often introduce their own biases [40].

Model Formulation

Bayesian models for RNA-seq data typically employ distributions that account for over-dispersion, a common characteristic of count-based sequencing data. The hierarchical gamma-negative binomial (hGNB) model, for instance, uses the following formulation [41]:

- Gene counts modeled as: ( n{vj} \sim \text{NB}(r{j},p_{vj}) )

- Cell-level dispersion parameters: ( r{j} \sim \text{Gamma}(e{0},1/h) )

- Regression model on probability parameter: ( \psi{vj} = \text{logit}(p{vj}) = \boldsymbol{\beta}{v}^{T}\boldsymbol{x}{j} + \boldsymbol{\delta}{j}^{T}\boldsymbol{z}{v} + \boldsymbol{\phi}{v}^{T}\boldsymbol{\theta}{j} )

This framework naturally accounts for various technical and biological effects without requiring explicit zero-inflation modeling, which can place unnecessary emphasis on zero counts and complicate discovery of latent data structures [41].

Workflow Diagram: Bayesian Inference Approach

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Most-Voting with mmquant

Application: Gene quantification while handling multi-mapped reads via merged genes.

- Read Mapping: Map RNA-seq reads using a compatible aligner (e.g., STAR).

- Sort BAM File: Ensure the BAM file containing mapped reads is sorted.

- Run mmquant:

The

-l 1parameter specifies that a read matches a gene if they overlap by at least 1 base pair [28]. - Downstream Analysis: Use the output count file (containing both original and merged genes) with differential expression tools like DESeq2.

Protocol 2: Bayesian Differential Expression Analysis

Application: Model-based inference for differential expression focusing on gene-level conclusions.

- Data Preparation: Collect position-specific read counts for genes under biological conditions of interest [40].

- Model Specification: Implement a hierarchical Bayesian model that:

- Model Inference: Use Gibbs sampling or other Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods to obtain posterior distributions [41].

- Interpretation: Report posterior probabilities of differential expression at the gene level, which can be used to control false discovery rates [40].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Handling Multi-Mapped Reads

| Tool/Resource | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| mmquant | Gene quantification with multi-mapped read handling | Implements Most-Voting via merged genes; resolves ambiguities with specific rules [28] |

| htseq-count | Standard gene quantification | Discards multi-mapped reads; three counting modes available [28] |

| featureCounts | Efficient read counting | Can count multi-mapping reads with options but practice is discouraged [28] |

| Bayesian Hierarchical Models | Probabilistic inference for differential expression | Uses position-level counts; robust to outliers; reports posterior probabilities [40] |

| R Statistical Environment | Platform for implementing Bayesian methods | Public domain R packages available for Bayesian RNA-seq analysis [40] |

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the main sources of multi-mapped reads in RNA-seq data? Multi-mapped reads primarily originate from duplicated sequences in eukaryotic genomes, resulting from recombination, whole genome duplication, and retro-transposition events [30] [6]. Different gene biotypes are affected dissimilarly, with long-noncoding RNAs and messenger RNAs generally sharing less sequence similarity than genes encoding shorter RNAs [30].

How does the Most-Voting strategy differ from simply discarding multi-mapped reads? Unlike approaches that discard multi-mapped reads (losing information), the Most-Voting strategy preserves this information by creating merged gene entities. This allows utilization of all sequencing data without introducing bias through uniform distribution across mapping locations [28].