RNA Bioscience: From Foundational Principles to Therapeutic Revolution

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of RNA bioscience, tracing its journey from fundamental molecular principles to its current status as a transformative therapeutic platform.

RNA Bioscience: From Foundational Principles to Therapeutic Revolution

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of RNA bioscience, tracing its journey from fundamental molecular principles to its current status as a transformative therapeutic platform. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it delves into the structural and functional core of RNA molecules, including mRNA, tRNA, rRNA, and various non-coding RNAs. It systematically examines the key methodologies powering the next generation of RNA therapeutics, such as antisense oligonucleotides, RNA interference, and mRNA-based platforms, while also addressing critical challenges in delivery, stability, and immunogenicity. The content further validates these approaches through analysis of approved therapies and clinical trials, and concludes with a forward-looking perspective on the limitless future of RNA in treating previously undruggable targets and personalizing medicine.

The RNA Blueprint: Structure, Function, and Central Dogma

Ribonucleotides serve as the fundamental monomeric building blocks of RNA, playing an indispensable role in the storage and transmission of genetic information, as well as in catalytic and regulatory functions within the cell. In biochemistry, a ribonucleotide is defined as a nucleotide containing ribose as its pentose component, distinguishing it from deoxyribonucleotides which form the backbone of DNA. These molecules are considered molecular precursors to nucleic acids and perform diverse cellular functions beyond information storage, including energy transfer, enzyme cofactor components, and cellular signaling. The unique chemical properties of the RNA backbone, characterized by its ribose sugar and phosphate groups, confer upon RNA a structural versatility and functional diversity that is central to modern RNA bioscience research. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the chemical architecture of ribonucleotides and the RNA backbone, highlighting critical differences from DNA that underlie RNA's distinct biological roles and stability characteristics, with implications for therapeutic development.

Structural Composition of Ribonucleotides

Core Components

The structure of a ribonucleotide consists of three primary molecular components: a phosphate group, a ribose sugar, and a nitrogenous base [1] [2] [3]. These components assemble in a specific configuration that defines the molecule's chemical properties and biological functions.

Nitrogenous Base: The nucleobase component can be adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), or uracil (U) [1] [4]. Adenine and guanine are purines (comprising a nine-member double-ring structure), while cytosine and uracil are pyrimidines (six-member single-ring structures) [3]. This differs from DNA, which contains thymine instead of uracil [4].

Pentose Sugar: Ribonucleotides contain ribose, a five-carbon sugar (aldopentose) with the formula (CHâ‚‚O)â‚… [3]. The critical structural feature distinguishing ribose from deoxyribose is the presence of a hydroxyl group (-OH) at the 2' carbon position [1] [4].

Phosphate Group: A phosphoric acid (H₃PO₄) moiety attaches to the 5' carbon of the ribose sugar [5]. This phosphate group is crucial for forming phosphodiester bonds that link nucleotides into polynucleotide chains.

Table 1: Core Components of a Ribonucleotide

| Component | Chemical Description | Role in Nucleotide Structure |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrogenous Base | Purines (adenine, guanine) or pyrimidines (cytosine, uracil) | Determines base pairing specificity and hydrogen bonding patterns |

| Ribose Sugar | Pentose sugar with hydroxyl group at 2' carbon | Forms the central core; 2' OH increases reactivity but decreases stability |

| Phosphate Group | Phosphoric acid (H₃PO₄) | Enables polymerization via phosphodiester bonds; confers negative charge |

When the nitrogenous base attaches to the ribose sugar without the phosphate group, the resulting molecule is termed a nucleoside [1]. The addition of one or more phosphate groups creates the complete nucleotide, which can exist as a monophosphate (NMP), diphosphate (NDP), or triphosphate (NTP) [2]. The phosphorylation state significantly impacts the nucleotide's reactivity and biological function, with triphosphates serving as substrates for polymerase enzymes and as energy carriers (e.g., ATP) [2].

Ribonucleotide Monomers

The four major ribonucleotide monomers that serve as building blocks for RNA are defined by their specific nitrogenous bases [1]:

- Adenylate (AMP): Adenine-containing ribonucleotide

- Guanylate (GMP): Guanine-containing ribonucleotide

- Uridylate (UMP): Uracil-containing ribonucleotide

- Cytidylate (CMP): Cytosine-containing ribonucleotide

These monomeric units link together via phosphodiester bonds to form RNA polymers, with the sequence of bases determining the RNA's informational content and structural potential.

The RNA Backbone: Structure and Conformational Diversity

Chemical Connectivity and Backbone Atoms

The RNA backbone consists of an alternating pattern of phosphate groups and ribose sugars connected via phosphodiester bonds [1]. These bonds form between the 3' hydroxyl group of one ribonucleotide and the 5' phosphate group of the adjacent ribonucleotide, creating a directional backbone from 5' to 3' [2]. The RNA polymerase enzyme catalyzes this linkage, with the 3'-hydroxyl group acting as a nucleophile to attack the 5'-triphosphate of the incoming ribonucleotide, releasing pyrophosphate as a byproduct [1].

The complete RNA backbone comprises 13 atoms per nucleotide: a phosphate group (P, OP1, OP2, O5'), the ribose sugar (C1'-C5', O2', O3', O4'), and a nitrogen atom (N) at the stem of the base [6]. This represents a significantly more complex atomic arrangement compared to protein backbones, which contain only 4 atoms per residue [6]. At neutral pH, the phosphate groups carry a negative charge, making RNA a highly charged polyanion that requires metal ions (such as Mg²âº) for structural stabilization [1] [4].

Backbone Conformational Flexibility

The RNA backbone exhibits considerable conformational flexibility, enabled by rotation around several bonds in the phosphodiester linkage. Research from the RNA Ontology Consortium has identified 46 discrete conformers that represent favorable, clustered regions in the seven-dimensional dihedral angle space that defines backbone conformation [7]. These conformers are described using a modular nomenclature system where a two-character name (number + letter) specifies the dihedral angle combinations:

- The first character (number) represents the combination of δ, ε, and ζ dihedral angles for the first half of the "suite" conformer (sugar-to-sugar unit)

- The second character (letter) represents the α, β, γ, and δ dihedral angles in the second half of the suite conformer [7]

This classification system reveals that RNA backbone conformations are not random but populate specific, identifiable regions that correspond to structural roles and motifs. For example, the 1a conformer is characteristic of A-form helices, while 5z, 4s, and #a conformers form the distinctive S-shape in S-motifs [7]. The ability to adopt these diverse conformations enables RNA to fold into complex tertiary structures that facilitate its diverse functional roles.

Table 2: Key RNA Backbone Conformers and Their Structural Roles

| Conformer Name | Ribose Puckers | Structural Role/Features |

|---|---|---|

| 1a | C3'-endo / C3'-endo | Standard A-form RNA helix conformation |

| 5z | C3'-endo / C2'-endo | Component of S-motifs |

| 4s | C2'-endo / C2'-endo | Component of S-motifs |

| #a | C2'-endo / C3'-endo | Component of S-motifs |

Key Structural Differences Between RNA and DNA

Sugar Composition and Its Implications

The most fundamental difference between RNA and DNA lies in their sugar components: RNA contains ribose, while DNA contains deoxyribose [1] [5]. This seemingly minor chemical distinction has profound implications for the properties and functions of these nucleic acids.

Deoxyribose differs from ribose by the replacement of the 2' hydroxyl group with a hydrogen atom [1]. This structural modification dramatically influences the molecules' relative stability, reactivity, and structural preferences:

Chemical Stability: The 2' hydroxyl group in RNA makes it more susceptible to hydrolysis, particularly under alkaline conditions, where the hydroxyl group can deprotonate and attack the adjacent phosphodiester bond, cleaving the backbone [4]. DNA lacks this reactive group, making it more chemically stable for long-term information storage.

Structural Conformations: The presence of the 2' hydroxyl group favors the A-form geometry in RNA helices, resulting in a wider, shallower minor groove and a narrower, deeper major groove compared to the B-form geometry typically adopted by DNA [4].

Backbone Flexibility: Despite DNA's greater overall chemical stability, the 2' hydroxyl group in RNA enables additional hydrogen bonding opportunities that can stabilize specific tertiary structures and participate in catalytic mechanisms [8].

Base Composition and Structural Organization

A second key difference lies in the nitrogenous base composition. While both nucleic acids contain adenine, guanine, and cytosine, RNA contains uracil instead of thymine [1] [4]. Uracil is functionally equivalent to thymine in base-pairing with adenine but lacks the methyl group present in thymine.

The structural organization of RNA and DNA also differs significantly:

Strandedness: DNA typically exists as a double-stranded molecule forming the classic double helix, while RNA is often single-stranded [4]. However, RNA molecules frequently contain self-complementary regions that allow them to fold back on themselves, forming complex secondary and tertiary structures.

Structural Diversity: Single-stranded RNA can fold into a wide variety of structural motifs, including hairpin loops, bulges, internal loops, and junctions [4]. This structural complexity enables RNA to perform diverse functions beyond information transfer, including catalysis and molecular recognition.

Table 3: Comprehensive Structural Comparison of RNA and DNA

| Structural Feature | RNA | DNA |

|---|---|---|

| Sugar Component | Ribose (with 2'-OH) | Deoxyribose (with 2'-H) |

| Pyrimidine Bases | Cytosine, Uracil | Cytosine, Thymine |

| Typical Strandedness | Single-stranded (with secondary structure) | Double-stranded |

| Predominant Helix Form | A-form | B-form |

| Chemical Stability | Lower (susceptible to alkaline hydrolysis) | Higher (resistant to hydrolysis) |

| Structural Diversity | High (various motifs: loops, bulges, etc.) | Limited (primarily double helix) |

| Major Groove | Narrow and deep | Wide and deep |

| Minor Groove | Wide and shallow | Narrow and shallow |

Functional Implications of Structural Differences

Stability and Biological Roles

The structural differences between RNA and DNA directly correlate with their distinct biological functions. DNA's chemical stability, conferred by the absence of the 2' hydroxyl group and the protection of its double-stranded structure, makes it ideal for long-term genetic information storage [9]. The faithful transmission of genetic information across generations requires this molecular stability.

In contrast, RNA's relative instability and structural flexibility suit it for dynamic cellular functions [9]. Messenger RNA (mRNA) serves as a transient information carrier between DNA and the protein synthesis machinery. The controlled turnover of mRNA allows cells to rapidly adjust gene expression in response to changing conditions. Furthermore, RNA's structural versatility enables specific RNAs to perform catalytic (ribozymes) and regulatory functions that DNA cannot.

Backbone-Mediated Stabilization of RNA Structures

Despite its overall lower chemical stability, the RNA backbone contributes specific stabilizing interactions that enable the formation of complex tertiary structures. A notable example is the GpU dinucleotide platform, where an intra-backbone hydrogen bond between the O2' of guanosine and a non-bridging oxygen (O2P) of the connecting phosphate significantly stabilizes this common structural motif [8]. This backbone-mediated stabilization contributes to the prevalence of GpU platforms in RNA structures and explains their evolutionary conservation at functionally important sites like 5'-splice sites [8].

The backbone 2' hydroxyl groups also participate in additional hydrogen-bonding interactions that stabilize tertiary structures and facilitate specific molecular recognition events. These interactions illustrate how RNA transforms a potential liability (the reactive 2' OH) into a functional feature that expands its structural and catalytic capabilities.

Experimental Approaches and Research Methodologies

Analyzing RNA Backbone Conformations

The structural analysis of RNA backbones presents unique challenges due to their conformational complexity and the difficulty in obtaining high-resolution structural data. Several methodological approaches have been developed to address these challenges:

Dihedral Angle Analysis: Researchers analyze the seven backbone torsion angles (α, β, γ, δ, ε, ζ, and χ) to characterize RNA conformations. The RNA Ontology Consortium has established standardized methods for measuring and classifying these angles, identifying 46 discrete conformers through multidimensional cluster analysis of quality-filtered structural data [7].

Suite-based Classification: Rather than analyzing traditional nucleotide units (phosphate-to-phosphate), researchers often use the sugar-to-sugar "suite" unit, which provides stronger correlations between angle parameters and more reliable identification of conformational features [7].

Software Tools: Specialized computational tools facilitate RNA structural analysis. The Suitename program assigns suite conformer names and calculates a "suiteness" score that quantifies how well a given structure matches ideal conformer geometries [7]. The 3DNA software package enables identification and characterization of base pairs and higher-order structural motifs using stringent geometric parameters [8].

Identifying and Characterizing Structural Motifs

Experimental protocols for identifying and characterizing RNA structural motifs typically involve:

Structure Determination: Using X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy to solve RNA structures at high resolution (typically ≤2.5 Å for X-ray) [8].

Geometric Analysis: Applying geometric criteria to identify specific structural features:

- Nearly planar base arrangements (stagger ≤1.5 Å)

- Small angles between base normal vectors (≤30°)

- Appropriate distances between potential hydrogen-bonding atoms (≤3.3 Å) [8]

Statistical Analysis: Assessing the prevalence and conservation of motifs across different RNA structures and organisms to identify functionally important elements [8].

Dynamics Studies: Investigating conformational flexibility through methods like molecular dynamics simulations, which reveal how backbone dynamics contribute to RNA function.

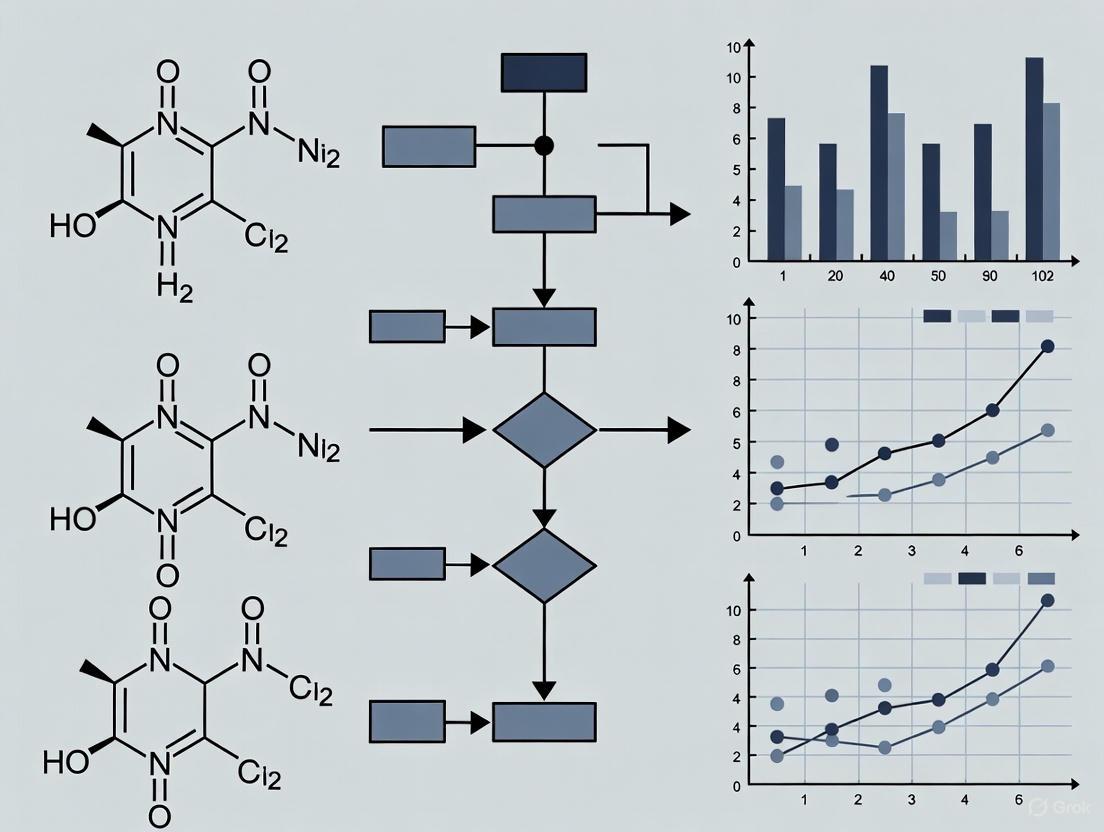

Diagram 1: RNA Structural Analysis Workflow

Research Reagents and Tools for RNA Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for RNA Structure-Function Studies

| Research Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ribonucleotide Triphosphates (NTPs) | Substrates for in vitro RNA synthesis by RNA polymerases | Quality crucial for transcription efficiency; often require HPLC purification |

| Ribonucleotide Reductase (RNR) | Enzyme that converts ribonucleotides to deoxyribonucleotides for DNA synthesis | Allosterically regulated by dATP/ATP ratios; key control point in nucleotide metabolism [1] |

| RNA Polymerases (T7, SP6, etc.) | Enzymatic synthesis of RNA for structural and functional studies | Promoter specificity; fidelity considerations for accurate synthesis |

| Suitename Software | Assigns backbone conformer names and suiteness scores from atomic coordinates | Enables standardized classification and comparison of RNA structures [7] |

| 3DNA Software Package | Identifies and characterizes base pairs and higher-order structural motifs | Uses geometric parameters for objective structural classification [8] |

| Crystallization Reagents | Facilitate formation of RNA crystals for X-ray structure determination | RNA crystallization remains challenging; often require screening numerous conditions |

| Stabilizing Ions (Mg²⺠etc.) | Compensate for negative charge and stabilize tertiary structure | Concentration-dependent effects on folding and stability |

The chemical architecture of ribonucleotides and the RNA backbone represents a sophisticated system that balances structural versatility with functional specificity. The presence of the 2' hydroxyl group on ribose distinguishes RNA from DNA at the most fundamental level, contributing to RNA's enhanced reactivity, conformational diversity, and functional range while limiting its chemical stability. The detailed understanding of RNA backbone conformations—cataloged in 46 discrete conformers with specific structural roles—provides a foundation for connecting sequence to structure to function in RNA molecules. As research advances, particularly in areas of RNA therapeutics and synthetic biology, these fundamental principles of RNA chemical architecture continue to inform the design of RNA-based tools and treatments, highlighting the enduring importance of structural biochemistry in driving biomedical innovation.

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a fundamental biopolymer that transcends its classical role as a passive messenger in the flow of genetic information. It functions as a versatile molecule involved in catalysis, gene regulation, and cellular maintenance. Unlike the relatively stable double helix of DNA, RNA molecules fold into complex three-dimensional architectures that are fundamental to their biological functions [10]. This folding process occurs through a defined hierarchy: primary structure (the nucleotide sequence), secondary structure (local base-pairing interactions), and tertiary structure (the overall three-dimensional arrangement). Understanding this structural progression is crucial for elucidating RNA function in normal physiology and disease, and for designing RNA-based therapeutics [11].

The folding of RNA is not a passive process that occurs after synthesis is complete. Rather, it is a co-transcriptional phenomenon, where the nascent RNA chain begins to form structures even as it emerges from the RNA polymerase exit channel [10]. This sequential folding can guide the RNA through specific pathways, preventing it from becoming trapped in non-functional conformations. The timescales involved underscore the efficiency of this process; RNA polymerases add nucleotides at a rate of 10-80 nucleotides per second, while small RNA hairpins can fold on the microsecond timescale, allowing structure formation to keep pace with synthesis [10]. This review provides an in-depth technical examination of the principles governing RNA folding, the experimental and computational tools for its investigation, and its implications for biomedical research.

The Fundamentals of RNA Folding

Primary Structure: The Information Layer

The primary structure of an RNA molecule is its linear sequence of nucleotides—adenosine (A), guanosine (G), cytidine (C), and uridine (U). This sequence is the blueprint that encodes all the information necessary to dictate the final folded structure. The canonical (G•C, A•U) and weaker (G•U) base pairs provide the fundamental rules for hydrogen bonding that drive the formation of secondary and tertiary structures [10] [12].

Secondary Structure: The Formation of Domains

Through intramolecular base pairing, RNA molecules fold into characteristic secondary structural elements. These include:

- Stem-loops (Hairpins): Formed when a region of the RNA pairs with another region nearby on the same strand, creating a double-stranded "stem" and an unpaired "loop."

- Internal Loops: Occur when unpaired nucleotides on both strands interrupt a double-stranded region.

- Bulges: Formed by unpaired nucleotides on only one strand of a double-stranded region.

- Junctions: Complex regions where multiple helical strands converge, such as in multi-branch loops [13].

These local structures provide specialized functions independent of the RNA's coding capacity, such as protein binding sites and the regulation of RNA processing, stability, and translation [10]. The repertoire of these folding motifs forms the building blocks for more complex architectures.

Tertiary Structure: The Functional Architecture

Tertiary structure refers to the three-dimensional atomic-level arrangement of the entire RNA molecule. It results from the packing of secondary structural elements against one another through long-range interactions. These interactions include:

- Non-canonical base pairing beyond the standard Watson-Crick pairs, utilizing other hydrogen-bonding edges of the bases (Hoogsteen and Sugar edges) [14].

- Pseudoknots, where a loop pairs with a complementary sequence outside its own stem.

- Coaxial stacking of helices.

- Ionic and other electrostatic interactions that stabilize the compact fold.

This final architecture creates unique surfaces and pockets that enable sophisticated functions, such as the catalytic activity of the ribosome and self-splicing introns [10] [15]. The function of an RNA is therefore intimately tied to its tertiary structure.

Quantitative Analysis of RNA Structure Prediction Methods

The accuracy of computational RNA structure prediction is quantitatively assessed using several key metrics. The following table summarizes the performance of contemporary algorithms as benchmarked in recent studies.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks of RNA Structure Prediction Algorithms

| Method | Type | Key Feature | Reported Accuracy (TestSetB F-value) | Typical RMSD for Tertiary Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MXfold2 [13] | Secondary Structure | Deep learning integrated with thermodynamic parameters | 0.601 | - |

| CONTRAfold [13] | Secondary Structure | Machine learning / SCFG | 0.573 | - |

| RNAfold [13] | Secondary Structure | Thermodynamic / Minimum Free Energy | ~0.55 | - |

| NuFold [15] | Tertiary Structure | End-to-end deep learning | - | < 6.0 Ã… (for 25/36 test targets) |

| SMCP [14] | Tertiary Structure | Stepwise Monte Carlo in Rosetta | - | Up to 0.14 Ã… (on small motifs) |

| FARFAR2 [15] | Tertiary Structure | Energy minimization with Rosetta | - | Varies, generally outperformed by deep learning |

Abbreviations: RMSD: Root Mean Square Deviation; SCFG: Stochastic Context-Free Grammar.

The root mean square deviation (RMSD), measured in Angstroms (Ã…), is a common metric for tertiary structure accuracy, quantifying the average distance between corresponding atoms in predicted and experimental structures. The Global Distance Test-Total Score (GDT-TS), ranging from 0 to 1, measures the overall structural similarity, with 1 indicating perfect agreement [15]. For secondary structure prediction, performance is evaluated using the F-value (the harmonic mean of precision and sensitivity) derived from confusion matrices of base-pair predictions [13].

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Predicting RNA Secondary Structure with MXfold2

MXfold2 is a robust algorithm that integrates deep learning with thermodynamic parameters to minimize overfitting [13].

- Input Preparation: Provide a single RNA sequence in FASTA format.

- Feature Calculation:

- The sequence is processed by a deep neural network (DNN) that computes four types of folding scores for each potential nucleotide pair.

- Simultaneously, Turner's nearest-neighbor free energy parameters for characteristic substructures (hairpins, internal loops, etc.) are calculated.

- Score Integration: The DNN-derived folding scores and thermodynamic free energy parameters are integrated into a unified scoring function.

- Structure Prediction: A Zuker-style dynamic programming algorithm is used to find the secondary structure that maximizes the sum of the scores for all decomposed nearest-neighbor loops.

- Output: The algorithm returns the predicted optimal secondary structure in dot-bracket notation and a graphical representation.

The training of the DNN employs a max-margin framework with thermodynamic regularization, a technique that prevents the model's folding scores from deviating significantly from experimentally derived free energies, thereby enhancing robustness on structurally dissimilar RNA families [13].

Protocol 2: De Novo Tertiary Structure Prediction with NuFold

NuFold is an end-to-end deep learning approach for predicting all-atom RNA tertiary structures [15].

- Input and Preprocessing:

- Sequence: Input the target RNA nucleotide sequence.

- Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA): Generate an MSA for the input sequence using tools like

rMSAto extract co-evolutionary information. - Secondary Structure: Obtain a predicted secondary structure using a tool like

IPknot.

- Network Processing:

- The sequence, MSA, and secondary structure are fed into the NuFold neural network, which is based on an adapted AlphaFold2 architecture.

- The network's Evoformer blocks process the MSA and residue-pair information to generate an embedding.

- 3D Structure Generation:

- The Structure Module constructs the 3D coordinates. It uses a flexible nucleobase center representation, defining a base frame with atoms O4', C1', C2', and the first nitrogen of the base (N1 or N9).

- All other atoms are partitioned into ten frames, which are iteratively bonded using predicted torsion angles, allowing precise modeling of different sugar conformations (e.g., C2'-endo vs. C3'-endo).

- Output and Recycling: The initial structure is passed through the network multiple times (recycling) for refinement. The final output is a full-atom 3D model in PDB format.

Diagram: NuFold End-to-End Prediction Workflow

Protocol 3: Structural Comparison and Motif Search with PRIMOS

PRIMOS is a methodology for comparing RNA structures and searching for folding motifs using a reduced mathematical representation of RNA conformation [12].

- Data Preparation: Obtain the 3D structures of the RNA molecules to be compared or searched in PDB format.

- Calculation of Pseudotorsions:

- For each nucleotide i in the structure, calculate the two pseudotorsion angles:

- η (eta): The angle for the virtual bonds C4′i-1–Pi–C4′i–Pi+1.

- θ (theta): The angle for the virtual bonds Pi–C4′i–Pi+1–C4′i+1.

- For each nucleotide i in the structure, calculate the two pseudotorsion angles:

- Generate RNA "Worm" Representation:

- Create a three-dimensional plot where the x-axis is the η value, the y-axis is the θ value, and the z-axis is the nucleotide sequence position. Connecting the points in sequence order creates an "RNA worm," which is a visual roadmap of the molecule's conformation.

- Structural Comparison:

- To compare two structures (A and B) of the same length, calculate the difference Δ(η,θ) for each nucleotide i using the formula: Δ(η,θ)i = √( (ηiA - ηiB)² + (θiA - θiB)² )

- Nucleotides with Δ(η,θ) < 25° are generally considered structurally similar.

- Motif Search:

- Define a query motif by the η and θ values of its constituent nucleotides.

- Use PRIMOS to scan a database of RNA worm files, identifying regions where the Δ(η,θ) for the query sequence falls below a defined threshold (e.g., < 25° per nucleotide and a cumulative sum below a cutoff).

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for RNA Structural Biology

| Item / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Torsion Angles (η, θ) [12] | Mathematical Descriptor | Quantitative description of nucleotide conformation; enables structural comparison and motif search. | Creating an "RNA worm" for comparing ribosomal complexes. |

| PRIMOS Software [12] | Computational Tool | Analyzes RNA structures to identify motifs and overall structural changes from PDB files. | Pinpointing sites of conformational change in ribosomes. |

| Rosetta Software Suite [14] | Computational Framework | Provides energy functions (e.g., REF15) and sampling methods for ab initio macromolecular modeling. | Predicting tertiary structures using the SMCP algorithm. |

| Forna [16] | Web Tool | Visualizes and allows editing of RNA secondary structures directly in a web browser. | Quickly displaying and communicating secondary structure models. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) [11] | Delivery Reagent | Formulate and deliver RNA therapeutics (e.g., mRNA vaccines, siRNAs) into cells in vivo. | Delivery of mRNA vaccines for clinical applications. |

| Modified Nucleosides [11] | Biochemical Reagent | Enhance stability and reduce immunogenicity of synthetic RNA molecules. | Production of therapeutic mRNAs and circular RNAs. |

The principles of RNA folding are not merely academic; they form the foundation for the rapidly expanding field of RNA-based therapeutics. The stability, immunogenicity, and translational efficiency of therapeutic RNA molecules are directly influenced by their structure [11]. For instance, the incorporation of modified nucleosides and the design of optimized sequences in mRNA vaccines prevent excessive secondary structure that could hinder translation and reduce protein yield [11]. Furthermore, the functional mechanisms of several RNA therapeutic classes rely on structural recognition:

- Small Interfering RNAs (siRNAs): These duplex RNAs are loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), where the guide strand must adopt a specific conformation to identify and cleave complementary target mRNA [11].

- Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs): These single-stranded RNAs hybridize to their target mRNA based on sequence complementarity, and their effectiveness can be modulated by the secondary structure of both the ASO and its target [11].

- Circular RNAs (circRNAs): As stable, closed-loop molecules lacking free ends, circRNAs are emerging as promising platforms for durable protein expression. Their functional properties are dictated by their unique tertiary architecture [17] [11].

In conclusion, the journey from a one-dimensional RNA sequence to a functional three-dimensional structure is a complex yet fundamental process in biology. Mastering the principles of primary, secondary, and tertiary folding, and leveraging the powerful experimental and computational tools now available, is critical for advancing our basic understanding of RNA biology and for designing the next generation of RNA-based medicines. The convergence of molecular biology, deep learning, and structural bioinformatics is poised to accelerate the discovery of novel RNA motifs and the development of transformative therapeutics for a wide range of diseases.

Within the foundational framework of molecular biology, the flow of genetic information from DNA to functional proteins is mediated by a sophisticated interplay of RNA molecules. While deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) serves as the long-term repository of genetic information, ribonucleic acid (RNA) acts as the critical intermediary and executor of these instructions. Among the various classes of RNA, three types form the core machinery of protein synthesis: messenger RNA (mRNA), ribosomal RNA (rRNA), and transfer RNA (tRNA). These molecules represent a fundamental pillar in RNA bioscience research, as their coordinated functions translate the static genetic code into the dynamic protein structures that drive cellular life. Understanding their distinct structures, precise functions, and intricate interactions is paramount for advancing research in gene expression regulation, cellular biology, and the development of novel therapeutic strategies, including RNA-based vaccines and antibiotics.

Structural and Functional Profiles of the Major RNAs

Messenger RNA (mRNA): The Information Intermediary

Messenger RNA (mRNA) functions as a crucial information bridge, carrying the genetic code for a specific protein from the DNA in the nucleus to the cytoplasm, where protein synthesis occurs [18] [19]. Its name precisely describes its role as a "messenger" of genetic information.

Structure and Synthesis: mRNA is transcribed as a complementary copy of a gene's DNA sequence by the enzyme RNA polymerase [19]. In eukaryotes, the initial transcript (pre-mRNA) undergoes extensive processing, including the addition of a 5' cap structure and a 3' poly-Adenosine (polyA) tail, and the removal of non-coding introns [19]. The 5' cap protects the molecule and is essential for initiating translation, while the polyA tail enhances stability and facilitates export from the nucleus [19]. Mature mRNA is a single-stranded, linear molecule that can vary significantly in length, from a few hundred to several thousand nucleotides, reflecting the size of the protein it encodes [18] [20].

Function in Translation: The primary function of mRNA is to serve as a template for protein synthesis. It carries the genetic information in the form of three-nucleotide sequences called codons, each of which specifies a particular amino acid [18] [21]. The mRNA molecule is decoded by the ribosome, which reads these codons in a 5' to 3' direction, dictating the sequence in which amino acids are assembled into a polypeptide chain [18].

Ribosomal RNA (rRNA): The Catalytic Factory

Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) is the central structural and functional component of the ribosome, the cellular organelle that catalyzes protein assembly [22] [23] [24]. It is the most abundant type of RNA in the cell, constituting about 80% of the total cellular RNA [23] [24].

Structure and Assembly: Ribosomes are composed of two subunits, one large and one small, each containing distinct rRNA molecules and ribosomal proteins [22] [23]. In eukaryotes, the large (60S) subunit contains the 28S, 5.8S, and 5S rRNAs, while the small (40S) subunit contains the 18S rRNA [23]. In prokaryotes, the large (50S) subunit contains 23S and 5S rRNAs, and the small (30S) subunit contains 16S rRNA [24]. These rRNA molecules fold into complex, highly conserved three-dimensional structures that form the scaffold for ribosomal assembly and create the key functional sites [24].

Catalytic and Functional Roles: rRNA is a ribozyme, meaning it possesses catalytic activity. Specifically, the 23S rRNA in prokaryotes (and its eukaryotic equivalent, the 28S rRNA) forms the peptidyl transferase center, which catalyzes the formation of peptide bonds between amino acids, the fundamental chemical reaction of protein synthesis [18] [24]. Beyond this enzymatic role, rRNA ensures the proper alignment of the mRNA and tRNA within the ribosome, facilitates the binding of tRNA to the mRNA codon, and contributes to the overall speed and accuracy of translation [18] [22].

Transfer RNA (tRNA): The Molecular Adaptor

Transfer RNA (tRNA) serves as the physical link between the genetic code in mRNA and the amino acid sequence of a protein [18] [25]. It is often described as a molecular "adaptor" that decodes the mRNA message.

Structure and Specificity: tRNA is a relatively small RNA molecule, typically 70-90 nucleotides long [18] [20]. Its secondary structure folds into a characteristic cloverleaf pattern, which further folds into an L-shaped three-dimensional structure [25]. Key regions include:

- The acceptor stem, where a specific amino acid is attached.

- The anticodon loop, which contains a three-nucleotide sequence (the anticodon) that base-pairs with the complementary codon on the mRNA [20] [25]. Each tRNA is charged with its correct corresponding amino acid by a family of enzymes called aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, a critical step ensuring translational fidelity [25].

Function in Translation: During translation, tRNA molecules deliver amino acids to the ribosome. The anticodon of the charged tRNA recognizes and binds to the appropriate codon on the mRNA, ensuring that the correct amino acid is added to the growing polypeptide chain in the sequence specified by the genetic code [18] [21].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of mRNA, rRNA, and tRNA

| Feature | Messenger RNA (mRNA) | Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) | Transfer RNA (tRNA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Carries genetic code from DNA to ribosome as a template for protein synthesis [18] [19] | Catalyzes peptide bond formation and provides structural core of the ribosome [18] [24] | Brings correct amino acids to the ribosome as specified by mRNA codons [18] [25] |

| Typical Length | 300 - 12,000 nucleotides [20] | Varies by type (e.g., ~1800 nt for 18S; ~5000 nt for 28S) [24] | 70 - 90 nucleotides [18] [20] |

| Secondary Structure | Largely linear, with limited base pairing [18] | Extensive stem-loops, complex 3D folding [24] | "Cloverleaf" 2D structure folds into an "L-shaped" 3D structure [25] |

| Key Functional Elements | Codons (e.g., AUG start), 5' cap, 3' poly-A tail [19] [21] | Peptidyl transferase center, decoding center [24] | Anticodon, amino acid acceptor stem [20] [25] |

| Stability | Unstable, short-lived [18] [19] | Very stable [18] | Stable [18] |

| Relative Abundance | Low (~5% of cellular RNA) | High (~80% of cellular RNA) [23] [24] | Moderate (~15% of cellular RNA) |

The Collaborative Process of Protein Synthesis

Protein synthesis, or translation, is the staged process where mRNA, rRNA, and tRNA functionally converge at the ribosome to assemble a protein. The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and key molecular interactions involved.

Diagram 1: The logical workflow of the translation process, showing the key roles of mRNA, rRNA, and tRNA.

The process of translation is divided into three main stages: initiation, elongation, and termination [21].

Initiation: The small ribosomal subunit, guided by initiation factors, binds to the 5' end of the mRNA and scans until it locates the start codon (AUG). The initiator tRNA, charged with methionine, base-pairs with the start codon. Finally, the large ribosomal subunit assembles to form the complete, functional ribosome [21].

Elongation: This cyclic process adds amino acids to the growing polypeptide chain. It involves three key steps that occur within the ribosome's functional sites, which are primarily composed of rRNA [24]:

- Codon Recognition: An incoming aminoacyl-tRNA, with an anticodon complementary to the mRNA codon in the A site, is delivered.

- Peptide Bond Formation: The rRNA catalyzes the transfer of the polypeptide chain from the tRNA in the P site to the amino acid attached to the tRNA in the A site, forming a new peptide bond.

- Translocation: The ribosome moves precisely three nucleotides along the mRNA, shifting the tRNAs from the A and P sites to the P and E sites, respectively. The deacylated tRNA in the E site is then ejected.

Termination: Elongation continues until a stop codon (UAA, UAG, or UGA) enters the A site. Since no tRNA molecules recognize these codons, a release factor protein binds instead. This triggers the hydrolysis of the completed polypeptide from the final tRNA, leading to the release of the protein and the dissociation of the ribosome into its subunits [21].

Advanced Research Frontiers: RNA Modifications

Contemporary research in RNA bioscience has moved beyond the foundational roles of these molecules to focus on post-transcriptional modifications that add a layer of regulatory complexity. One of the most abundant and significant modifications is pseudouridylation [26].

Pseudouridine (Ψ) is an isomer of the nucleoside uridine and is found across all major RNA types: mRNA, rRNA, and tRNA. A recent 2025 study in plants utilized bisulfite-induced deletion sequencing to generate comprehensive, quantitative maps of pseudouridine at single-base resolution [26]. The research revealed a multilayered system of translation control governed by Ψ modifications:

- rRNA Pseudouridylation: Modifications in ribosomal RNA were found to exert global control over the efficiency of the translation process, though the effects were highly dependent on the specific site of modification within the rRNA structure [26].

- tRNA Pseudouridylation: The presence of Ψ in the T-arm loop of tRNA molecules showed a strong positive correlation with the translation efficiency of their corresponding codons, suggesting a role in fine-tuning decoding accuracy and speed [26].

- mRNA Pseudouridylation: While an inverse correlation was observed between Ψ levels and mRNA stability, there was a positive correlation with translation efficiency, indicating a complex role in regulating the fate and functionality of messenger RNA [26].

This research underscores the dynamic nature of the "epitranscriptome" and highlights how RNA modifications serve as critical regulatory switches, opening new avenues for therapeutic intervention by targeting these modification pathways.

Experimental Protocol: Profiling Pseudouridine Modifications

The following table details key reagents and methodologies used in state-of-the-art research to study RNA modifications, as exemplified by the aforementioned study.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Pseudouridine Profiling

| Research Reagent / Method | Core Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Bisulfite-Induced Deletion Sequencing [26] | A robust profiling method that induces characteristic deletions at Ψ sites during reverse transcription, allowing for transcriptome-wide mapping of pseudouridine at single-base resolution. |

| Polysome Profiling [26] | An analytical technique used to separate ribosomes based on the number of associated mRNAs. It is used to correlate modification status with translation efficiency by analyzing the association of mRNAs with heavy polysomes. |

| RNA Polymerase III [25] | The enzyme complex responsible for transcribing tRNA genes. Studying its interaction with DNA and transcription factors is key to understanding the primary biogenesis of tRNA. |

| Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases [25] | A family of enzymes, one for each amino acid, that catalyze the attachment of the correct amino acid to its corresponding tRNA. These are essential reagents for in vitro translation systems and fidelity studies. |

| Pseudouridine Synthases [26] | The family of enzymes that catalyze the isomerization of uridine to pseudouridine. Inhibitors or activators of these enzymes are used to probe the functional consequences of Ψ modification. |

Implications for Research and Therapeutic Development

The intricate functions of mRNA, rRNA, and tRNA represent foundational principles in RNA bioscience with direct therapeutic relevance. Dysregulation or mutations in these molecules and their associated machinery are linked to a range of diseases, including ribosomopathies (diseases arising from defects in ribosome assembly and function) and cancer [23]. The profound understanding of mRNA biology, for instance, has directly enabled the rapid development of mRNA vaccines, which leverage the cell's own translation machinery to produce therapeutic antigens [19].

Future research will continue to delve deeper into the regulatory mechanisms governing these molecules, including the roles of epitranscriptomic modifications like pseudouridylation [26]. Furthermore, the structural differences between prokaryotic and eukaryotic ribosomes, particularly in their rRNA components, continue to provide a valuable platform for designing novel antibiotics that selectively target bacterial protein synthesis without affecting human hosts [22] [24]. The continued study of these three major RNA players is therefore not only fundamental to basic science but also critical for pioneering the next generation of molecular medicines.

The classical central dogma of molecular biology positioned RNA primarily as a messenger between DNA and proteins. However, contemporary research has revealed that RNA serves far more extensive functions, with catalytic and regulatory roles that are fundamental to cellular processes. The discovery of ribozymes (RNA enzymes) in the early 1980s demonstrated that RNA can act as both genetic material and a biological catalyst, challenging the previous paradigm that enzymatic activity was the exclusive domain of proteins [27]. This finding contributed significantly to the "RNA world" hypothesis, which proposes that RNA may have been the primary molecule of life in prebiotic self-replicating systems [27].

Parallel to the understanding of catalytic RNA, the vast landscape of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) has emerged. These functional RNA molecules are not translated into proteins but play crucial roles in regulating gene expression at transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and epigenetic levels [28]. While only approximately 2% of the human genome encodes proteins, most of the genome is transcribed into ncRNAs, indicating their significant biological importance [29]. This whitepaper examines the foundational principles of catalytic and regulatory RNAs, exploring their mechanisms, biological functions, research methodologies, and therapeutic applications within the broader context of RNA bioscience.

Ribozymes: Catalytic RNA Molecules

Historical Context and Discovery

The discovery of ribozymes was a groundbreaking achievement that earned Thomas R. Cech and Sidney Altman the 1989 Nobel Prize in Chemistry [27]. Cech's research on the excision of introns in a ribosomal RNA gene in Tetrahymena thermophila revealed that the intron could splice itself out without any protein enzymes. Concurrently, Altman's work on RNase-P demonstrated that the RNA component alone could process precursor tRNA into active tRNA without its protein subunit [27]. These findings established that RNA could function as a biological catalyst, leading to the introduction of the term "ribozyme" by Kelly Kruger et al. in 1982 [27].

Major Classes and Biological Functions

Table 1: Major Natural Ribozyme Classes and Their Functions

| Ribozyme Class | Size Range | Primary Biological Role | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hammerhead | ~50 nucleotides | RNA self-cleavage in viral and satellite genomes | Small, self-cleaving ribozyme; minimal metal ion requirement [30] |

| Hairpin | ~50 nucleotides | RNA processing in plant satellite RNAs | Metal-independent cleavage mechanism [30] |

| HDV (Hepatitis Delta Virus) | ~85 nucleotides | Viral genome replication | Uses perturbed nucleobases for acid/base catalysis [30] |

| VS (Varkud Satellite) | ~150 nucleotides | RNA splicing in fungal mitochondria | Complex structural organization [30] |

| Group I Intron | 200-1000+ nucleotides | Self-splicing of pre-rRNA in Tetrahymena | Uses external guanosine cofactor; large ribozyme [27] |

| Group II Intron | 600-1000+ nucleotides | Self-splicing in organellar and bacterial genes | Uses internal adenosine for splicing; related to spliceosome [30] |

| RNase P | ~400 nucleotides | tRNA 5'-end maturation | Processes precursor tRNAs; ubiquitous in all domains of life [27] |

| Ribosome | >2000 nucleotides | Protein synthesis | Peptide bond formation occurs on the ribosomal RNA [27] |

Ribozymes participate in diverse cellular processes, including RNA splicing, viral replication, transfer RNA biosynthesis, and protein synthesis [27]. Within the ribosome, ribozymes function as part of the large subunit ribosomal RNA to form peptide bonds between amino acids during protein synthesis, making them essential to all cellular life [27].

Mechanisms of Catalysis

Ribozymes accelerate phosphodiester bond cleavage through various chemical strategies. The general reaction involves an SN2-type in-line attack where the 2'-hydroxyl group acts as a nucleophile attacking the adjacent scissile phosphate, resulting in a 2',3'-cyclic phosphate and a 5'-hydroxyl terminus [30]. Ribozymes employ multiple mechanisms to catalyze this reaction:

- Metal-Ion-Dependent Catalysis: Many ribozymes utilize divalent metal ions (typically Mg²âº) as cofactors. These metal ions can function as: (a) Lewis acids to stabilize the developing negative charge on the transition state, (b) general base catalysts to deprotonate the 2'-OH nucleophile, or (c) general acid catalysts to protonate the 5'-oxygen leaving group [30].

- Metal-Ion-Independent Catalysis: Some ribozymes, such as hairpin ribozymes, can catalyze RNA cleavage without metal ions, suggesting alternative catalytic strategies, potentially involving nucleobases with perturbed pKa values that participate directly in acid-base catalysis [30].

- Transition State Stabilization: Like protein enzymes, ribozymes accelerate reactions by stabilizing the higher-energy pentacoordinate transition state through precise positioning of catalytic groups and electrostatic interactions [27].

The hepatitis delta virus (HDV) ribozyme exemplifies novel catalytic mechanisms, as its architecture allows perturbation of the pKa of specific cytosine and adenine ring nitrogens, enabling them to participate directly in acid/base catalysis [30].

Figure 1: Group I Intron Self-Splicing Mechanism. This diagram illustrates the two-step transesterification reaction catalyzed by group I intron ribozymes, which requires an external guanosine cofactor.

The Regulatory Landscape of Non-Coding RNAs

Biogenesis and Functional Classification

Non-coding RNAs are broadly categorized based on size and function. The major classes include:

- MicroRNAs (miRNAs): Short (~22 nucleotide) RNAs that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally by binding to complementary sequences in target mRNAs, leading to translational repression or mRNA degradation [28]. Biogenesis involves transcription by RNA Polymerase II, nuclear processing by the Drosha-DGCR8 complex to form pre-miRNAs, export to the cytoplasm via Exportin-5, final processing by Dicer, and loading into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) [28].

- Long Non-Coding RNAs (lncRNAs): RNAs longer than 200 nucleotides with diverse regulatory roles in chromatin remodeling, epigenetic modifications, transcriptional regulation, and nuclear organization [28].

- Circular RNAs (circRNAs): Covalently closed loop structures generated through back-splicing, often functioning as miRNA sponges or protein decoys [28].

- Other ncRNAs: This category includes transfer RNAs (tRNAs), ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs), small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs), Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), and enhancer RNAs (eRNAs) [31].

Figure 2: miRNA Biogenesis and Function. This pathway outlines the canonical microRNA biogenesis pathway from transcription to mature miRNA-mediated gene regulation.

Mechanisms of Gene Regulation

Non-coding RNAs employ sophisticated mechanisms to control gene expression:

- Transcriptional Regulation: lncRNAs such as Xist mediate X-chromosome inactivation by recruiting chromatin-modifying complexes that establish transcriptionally silent heterochromatin [31]. Other ncRNAs interact with transcription factors or influence RNA polymerase II activity [31].

- Post-Transcriptional Regulation: miRNAs guide the RISC complex to target mRNAs through sequence complementarity, primarily to the 3'-untranslated regions (3'UTRs), resulting in mRNA degradation or translational inhibition [28].

- Epigenetic Regulation: Various ncRNAs participate in establishing and maintaining epigenetic marks, including DNA methylation and histone modifications, thereby creating stable gene expression states that can be inherited transgenerationally [29].

- RNA Processing Regulation: snoRNAs guide chemical modifications of rRNA, tRNA, and snRNAs, while snRNAs are essential components of the spliceosome that catalyzes pre-mRNA splicing [31].

Table 2: Regulatory ncRNAs and Their Functions in Gene Expression

| ncRNA Class | Size | Primary Function | Mechanistic Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| MicroRNA (miRNA) | ~22 nt | Post-transcriptional gene silencing | Binds target mRNAs via RISC; induces degradation/repression [28] |

| Long Non-Coding RNA (lncRNA) | >200 nt | Transcriptional & epigenetic regulation | Recruits chromatin modifiers; scaffolds protein complexes [28] |

| Circular RNA (circRNA) | Variable | miRNA sponging; protein decoys | Sequesters miRNAs or proteins via multiple binding sites [28] |

| Small Interfering RNA (siRNA) | 20-25 nt | Post-transcriptional gene silencing | Perfect complementarity to mRNAs; induces cleavage [31] |

| Piwi-interacting RNA (piRNA) | 26-31 nt | Transposon silencing in germlines | Forms piRC complexes; transcriptional silencing [31] |

| Small Nuclear RNA (snRNA) | ~150 nt | Pre-mRNA splicing | Catalytic core of the spliceosome [31] |

| Small Nucleolar RNA (snoRNA) | 60-300 nt | rRNA modification | Guides 2'-O-methylation and pseudouridylation [31] |

| Riboswitches | ~100-200 nt | Metabolic regulation & transcription | Alters conformation in response to ligands [29] |

Experimental Approaches in RNA Research

Key Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for RNA Functional Studies

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Drosha-DGCR8 Complex | Microprocessor complex for pri-miRNA to pre-miRNA processing | In vitro miRNA biogenesis assays [28] |

| Dicer Enzyme | RNase III endonuclease that processes pre-miRNA to miRNA duplex | miRNA maturation studies; RNAi applications [28] |

| Argonaute 2 (Ago2) | RISC catalytic component; mediates target mRNA cleavage | RISC immunoprecipitation; functional studies [28] |

| Modified Nucleotides | (e.g., 2'-F, 2'-O-Me, LNA); enhance stability and binding affinity | Therapeutic RNA development; FISH probes [28] |

| Exportin 5 (XPO5) | Nuclear export receptor for pre-miRNAs | Studying miRNA nuclear-cytoplasmic trafficking [28] |

| RNA-Friendly Nanoparticles | Lipid-based or polymeric delivery systems for RNA therapeutics | In vivo delivery of miRNA mimics/antagomirs [28] |

| RNase P | Endoribonuclease that generates mature 5'-ends of tRNAs | tRNA processing studies; in vitro transcription [27] |

| NMD Inhibitors | (e.g., NMDI-1) Block nonsense-mediated decay pathway | Studying NMD substrates and truncated protein production [32] |

Protocol: Analyzing Ribozyme Cleavage Activity

Objective: To measure the in vitro cleavage activity of a hammerhead ribozyme.

Ribozyme and Substrate Preparation:

- Template Design: Design DNA templates encoding the ribozyme and its target RNA substrate using known secondary structures.

- In Vitro Transcription: Transcribe RNA using T7 RNA polymerase, [α-³²P] CTP (radiolabeling), and NTPs. Purify transcripts via denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE).

- Folding: Denature RNA at 95°C for 2 minutes and snap-cool on ice. Add MgCl₂ to 10 mM and incubate at 37°C for 15 minutes to promote proper folding.

Cleavage Reaction:

- Prepare reaction mixture: 50 nM radiolabeled substrate, 100 nM ribozyme, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10-50 mM MgClâ‚‚.

- Incubate at 37°C. Remove aliquots at specific time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60 minutes).

- Stop reactions with 2x formamide loading buffer containing 50 mM EDTA.

Product Analysis:

- Resolve cleavage products by denaturing 8M urea PAGE (15-20% gel).

- Visualize and quantify bands using phosphorimager analysis.

- Calculate kinetic parameters (kobs, Km, k_cat) from time-course data.

Metal Ion Dependence Assessment:

- Repeat cleavage assays with varying Mg²⺠concentrations (0-100 mM) or other divalent cations (Ca²âº, Mn²âº).

- Test metal-free conditions with high concentrations of monovalent ions (e.g., 1M NaCl) and polyamines to assess metal independence [30].

Protocol: Functional Analysis of miRNA-Target Interactions

Objective: To validate miRNA binding and repression of a putative target mRNA.

Bioinformatic Prediction:

- Use algorithms (TargetScan, miRanda) to identify putative miRNA binding sites in target mRNA 3'UTR.

- Assess conservation across species to prioritize functional sites.

Luciferase Reporter Assay:

- Vector Construction: Clone wild-type and mutant 3'UTR sequences downstream of a luciferase reporter gene (e.g., psiCHECK-2).

- Cell Transfection: Co-transfect HEK293T cells with (a) luciferase reporter construct and (b) miRNA mimic or inhibitor using lipid-based transfection reagent.

- Measurement: Harvest cells 48 hours post-transfection. Measure Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities using dual-luciferase assay system. Normalize Renilla (reporter) luciferase to Firefly (control) activity.

Endogenous Target Validation:

- Transfert cells with miRNA mimic or inhibitor.

- Isolate total RNA and protein 48-72 hours post-transfection.

- Analyze target mRNA levels by quantitative RT-PCR.

- Analyze target protein levels by western blotting.

Direct Interaction Confirmation:

- Perform Argonaute Cross-Linking Immunoprecipitation (CLIP) to confirm physical association between miRNA-RISC complex and target mRNA [28].

Therapeutic Applications and Clinical Translation

The unique properties of catalytic and regulatory RNAs present significant therapeutic opportunities. Ribozymes can be engineered to cleave specific RNA sequences, offering potential for targeting viral genomes or oncogenic transcripts [27]. For instance, ribozymes have been designed to cleave HIV RNA, potentially preventing viral infection [27].

In the ncRNA domain, miRNA-based therapeutics are advancing rapidly. Strategies include:

- miRNA Mimics: Synthetic double-stranded RNAs that replace downregulated tumor suppressor miRNAs in cancer [28].

- Antagomirs (anti-miRNAs): Chemically modified oligonucleotides that sequester and inhibit oncogenic miRNAs [28].

- CircRNA-Based Therapies: Engineered circular RNAs that function as efficient miRNA sponges or protein decoys due to their inherent stability [28].

Key challenges in RNA therapeutic development include improving in vivo stability, ensuring specific delivery to target tissues, and minimizing off-target effects and immune responses. Innovative approaches to address these challenges include chemical modifications (2'-O-methyl, 2'-fluoro, locked nucleic acids) and advanced delivery systems (lipid nanoparticles, exosomes, targeted conjugates) [28].

The therapeutic potential of RNA extends beyond conventional targets. For example, personalized mRNA vaccines are being developed to train immune systems to attack individual tumor cells, showing promise in pancreatic cancer trials [32]. Additionally, small molecules that target specific RNA structures are emerging as a new class of therapeutics, with compounds designed to degrade cancer-promoting mRNAs like MYC [32].

The fields of catalytic and regulatory RNA research continue to evolve rapidly, driven by technological advances in RNA sequencing, structural biology, and bioinformatics. Future research directions include elucidating the intricate networks of RNA-RNA and RNA-protein interactions that govern cellular homeostasis, understanding the role of RNA structures in signaling pathways, and developing more sophisticated RNA-based therapeutics with enhanced precision and efficacy.

The exploration of ribozymes continues to provide insights into fundamental catalytic mechanisms and the origins of life, while the expanding world of ncRNAs reveals increasingly complex regulatory networks that control development, physiology, and disease. As our understanding of these RNA molecules deepens, they will undoubtedly yield new biomarkers for diagnosis, novel therapeutic targets, and innovative treatment modalities that leverage the unique properties of RNA for clinical application. The integration of RNA biology with precision medicine approaches promises to revolutionize both our understanding of fundamental biological processes and our ability to intervene therapeutically in human disease.

Within the foundational principles of RNA bioscience, two interconnected concepts fundamentally challenge the traditional view of the central dogma of molecular biology: the existence of RNA viruses and the RNA World Hypothesis. RNA viruses, including major human pathogens such as HIV, influenza, Ebola, and SARS-CoV-2, utilize RNA as their hereditary material, bypassing DNA entirely in their replication cycle [18] [33] [34]. This biological reality demonstrates that RNA is fully capable of storing and transmitting genetic information. The RNA World Hypothesis, a seminal concept in origins-of-life research, takes this a step further by proposing that early life forms were based primarily on RNA, which served as both the catalytic molecule and the repository of genetic information before the evolutionary emergence of DNA and proteins [35] [36]. This hypothesis posits that around 4 billion years ago, RNA was the primary living substance because of its dual capabilities [35]. Together, these concepts establish RNA not merely as a messenger but as a foundational biomolecule with an ancient and persistent role in heredity, providing a critical framework for understanding viral pathogenesis and guiding the development of novel antiviral therapeutics.

RNA as Hereditary Information in Viral Genomes

Structural and Functional Characteristics of RNA Genomes

In RNA viruses, the genome consists entirely of RNA, which carries all the necessary genetic instructions for viral replication and propagation. Structurally, these RNA genomes can be single-stranded (ssRNA) or double-stranded (dsRNA), configurations that significantly influence their replication strategies and detection by host immune systems [18]. For example, rhinoviruses (causing the common cold), influenza viruses, and the Ebola virus are single-stranded RNA viruses, while rotaviruses (which cause severe gastroenteritis) are examples of double-stranded RNA viruses [18]. The presence of double-stranded RNA in eukaryotic cells is uncommon and thus serves as a key indicator of viral infection, triggering host immune responses [18].

The molecular architecture of RNA provides both advantages and constraints as a genetic material. Compared to DNA, RNA is a relatively unstable molecule. Its core ribose sugar has a hydroxyl group that makes it more prone to hydrolysis and chemical degradation [18] [35]. This inherent instability contributes to higher mutation rates during replication, as RNA-dependent RNA polymerases generally lack the proofreading capabilities of DNA polymerases. While this might seem like a disadvantage, this high mutation rate is a key evolutionary strategy for RNA viruses, allowing for rapid adaptation, immune evasion, and the emergence of drug resistance [33]. However, for long-term genetic stability in cellular life, DNA's superior chemical stability made it more suitable as the primary repository of genetic information, leading to a biological division of labor: DNA for stable storage, RNA for temporary messaging and regulation, and proteins as efficient catalysts [35].

Major Classes of RNA Viruses and Their Genomes

RNA viruses represent a significant portion of known human pathogens, impacting global health through diseases such as AIDS, viral hepatitis, COVID-19, and influenza [33]. The table below summarizes the genomic characteristics and pathogenic profiles of major RNA virus families.

Table 1: Characteristics of Major RNA Virus Families and Their Genomes

| Virus Family/Example | Genome Type | Genome Size (approx.) | Associated Diseases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retroviridae (HIV) | ssRNA, positive-sense | ~9.8 kb | AIDS, resulting in immunodeficiency [34] [36] |

| Orthomyxoviridae (Influenza Virus) | ssRNA, segmented | ~13.5 kb (total) | Seasonal and pandemic influenza [18] [33] |

| Filoviridae (Ebola Virus) | ssRNA, negative-sense | ~19 kb | Ebola virus disease, severe hemorrhagic fever [18] |

| Coronaviridae (SARS-CoV-2) | ssRNA, positive-sense | ~30 kb | COVID-19 respiratory disease [34] |

| Reoviridae (Rotavirus) | dsRNA, segmented | ~18.5 kb (total) | Severe gastroenteritis in children [18] |

Replication Cycles and Key Viral RNA Structures

The replication cycle of an RNA virus is fundamentally shaped by its genome type. Positive-sense ssRNA genomes can be directly translated by host ribosomes upon entry into the cell, functioning much like cellular mRNA. In contrast, negative-sense ssRNA genomes must first be transcribed into a complementary positive-sense strand by a viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase before translation can occur. Retroviruses, such as HIV, employ a unique strategy where their RNA genome is reverse-transcribed into DNA by the enzyme reverse transcriptase, which then integrates into the host genome [36].

These viral RNA genomes are not mere linear sequences; they fold into specific, complex secondary and tertiary structures that are critical for their function. These structured elements can regulate nearly every step of the viral life cycle, including replication, translation, and packaging. For instance, the HIV-1 RNA genome contains highly conserved structural regions that are now major targets for experimental small-molecule therapeutics [34]. Other structured RNA elements, such as riboswitches predominantly found in bacteria, can bind small metabolites to regulate gene expression and are also being explored as novel antibiotic targets [34].

The RNA World Hypothesis: An Evolutionary Foundation

Core Principles and Historical Context

The RNA World Hypothesis is a foundational concept in evolutionary biology that proposes a stage in the early evolution of life where RNA both stored genetic information and catalyzed biochemical reactions, preceding the era of DNA and proteins [35]. In this hypothetical world, RNA would have been the primary living substance, and the earliest life forms would have relied on RNA alone for their genetic material and basic metabolic functions [35]. The hypothesis was first conceptualized in the 1960s by several prominent scientists, including Francis Crick, Carl Woese, and Leslie Orgel [35]. The term "RNA World" itself was later coined by Harvard molecular biologist Walter Gilbert in a 1986 article, which helped formalize and popularize the concept [35].

The hypothesis addresses a central paradox in the origin of life: which came first, the genetic information (DNA) or the metabolic catalysts (proteins)? Since each seems to require the other, a simpler system must have existed. RNA provides a solution because it can perform both roles, potentially breaking this circular dependency. This implies that all essential processes in living organisms initially evolved around RNA, and modern cells subsequently arose from these RNA-based predecessors [35].

Key Evidence Supporting the Hypothesis

Several lines of evidence lend significant credibility to the RNA World Hypothesis, painting a compelling picture of RNA's primordial role.

- Dual Functionality of RNA: The most fundamental evidence is RNA's inherent ability to serve as both a genetic blueprint and a catalyst. Unlike DNA, which is primarily a passive information repository, RNA can both store information in its nucleotide sequence and fold into complex three-dimensional shapes that catalyze chemical reactions [35] [36].

- The Discovery of Ribozymes: The discovery of ribozymes—RNA molecules with enzymatic activity—by Sidney Altman, Thomas Cech, and colleagues provided the first concrete proof that RNA could indeed catalyze biochemical reactions, a function previously thought to be exclusive to proteins. This groundbreaking work earned them the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1989 [35]. The most universally conserved and critical ribozyme is the ribosome, the cellular machine that synthesizes proteins. Although the ribosome contains protein components, the catalytic activity that forges peptide bonds between amino acids is performed by its ribosomal RNA (rRNA) core [18] [35]. This indicates that protein synthesis itself is fundamentally catalyzed by RNA, strongly supporting the idea that RNA-based catalysis predated the evolution of complex proteins.

- RNA's Central Role in Essential Cellular Processes: Beyond the ribosome, RNA is central to other fundamental processes. Transfer RNA (tRNA) is essential for decoding mRNA into protein sequences, and many modern cofactors, such as ATP and acetyl-CoA, are ribonucleotide derivatives, potentially representing molecular "fossils" of an earlier RNA world [35].

- In vitro Evolution Experiments: Laboratory experiments have demonstrated that random RNA sequences can evolve to perform novel functions, such as RNA ligation, showing that RNA has the intrinsic capacity to develop a wide range of catalytic activities from a prebiotic pool of molecules [35].

Challenges and Limitations of the Hypothesis

Despite its broad acceptance, the RNA World Hypothesis faces several significant challenges that remain active areas of scientific inquiry.

- Prebiotic Synthesis: A major challenge is explaining how the relatively complex building blocks of RNA (nucleotides) could have formed and polymerized spontaneously under the conditions of early Earth. The prebiotic synthesis of ribose sugar and the subsequent formation of nucleotides is chemically difficult [35].

- Chemical Instability: RNA is chemically less stable than DNA, particularly due to the susceptibility of its ribose sugar to hydrolysis. This instability would have made it a fragile molecule in a prebiotic environment, potentially limiting its longevity [35].

- Limited Catalytic Range: While ribozymes exist, they are generally not as efficient or structurally diverse as protein enzymes. It is challenging to envision an RNA-based organism orchestrating the vast array of metabolic reactions found in modern cells using ribozymes alone [35]. Some critics, like biochemist Harold S. Bernhardt, have argued that these issues make the RNA World an overly simplistic model for the origin of life [35].

Methodologies in Modern RNA Bioscience Research

Quantitative Analysis of RNA: RNA-seq Technology

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has emerged as the premier, powerful, and robust technique for quantitatively analyzing transcriptomes at a genome-wide level [37] [38]. It enables researchers to not only measure gene expression levels with high resolution but also to discover novel transcripts, identify splice variants, and characterize non-coding RNAs. Compared to older technologies like microarrays, RNA-seq offers a broader dynamic range, lower technical variability, and does not require pre-defined probes, allowing for the discovery of unexpected transcriptional events [37]. The high degree of agreement between RNA-seq data and gold-standard techniques like qRT-PCR validates its accuracy for both absolute and relative gene expression measurement [37].

The typical RNA-seq workflow involves multiple, sequential computational steps, and the choice of algorithms at each stage can significantly impact the final results. A complex study evaluating 192 different analysis pipelines highlighted the importance of these choices but also confirmed the technology's robustness when properly applied [37].

Table 2: Key Steps and Common Tools in an RNA-seq Analysis Pipeline

| Analysis Step | Purpose | Example Algorithms/Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Trimming | Removes adapter sequences and low-quality bases to improve downstream mapping. | Trimmomatic, Cutadapt, BBDuk [37] |

| Alignment | Maps the sequenced reads to a reference genome or transcriptome. | Bowtie2, TopHat [37] [38] |

| Quantification (Counting) | Counts the number of reads assigned to each gene or transcript. | FeatureCounts, HTSeq [37] |

| Normalization | Adjusts raw counts to remove technical biases (e.g., sequencing depth, gene length). | FPKM, TPM [37] |

| Differential Expression | Identifies genes that are statistically significantly changed between conditions. | Cufflinks, DESeq2, EdgeR [37] [38] |

Experimental Workflow for RNA-seq Analysis

The following diagram visualizes the standard end-to-end workflow for an RNA-seq experiment, from raw data to biological insight, incorporating the key steps and tools outlined above.

Research Reagent Solutions for RNA Studies

Cutting-edge research in RNA biology and the development of RNA-targeted therapies rely on a specific toolkit of reagents and methodologies. The following table details essential materials and their functions, particularly in the context of studying RNA viruses and exploring the RNA World Hypothesis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Advanced RNA Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Context |

|---|---|---|

| TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Kit | Preparation of sequencing libraries from RNA samples; preserves strand orientation. | Used for constructing RNA-seq libraries for transcriptome analysis, crucial for profiling viral gene expression [37]. |

| RNeasy Plus Mini Kit | Rapid purification of high-quality, genomic DNA-free total RNA from cells and tissues. | Essential for obtaining pure RNA input for downstream applications like RNA-seq and qRT-PCR [37]. |

| SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System | Reverse transcription of RNA into stable complementary DNA (cDNA). | Critical for qRT-PCR validation and for studying RNA viruses via reverse transcription [37]. |

| TaqMan qRT-PCR Assays | Highly specific and sensitive quantification of gene expression using fluorescent probes. | Considered a gold standard for validating RNA-seq results and measuring viral load [37]. |

| Custom Small-Molecule Libraries | Collections of drug-like compounds for high-throughput screening against RNA targets. | Used to identify lead compounds that bind to functional RNA structures (e.g., in HIV-1, riboswitches) [34]. |

| In vitro-Transcribed RNA | Production of defined RNA molecules for structural, biochemical, or functional studies. | Fundamental for studying ribozyme mechanics, viral RNA replication, and RNA structure-function relationships [35]. |

Therapeutic and Diagnostic Applications

Targeting RNA with Small-Molecule Drugs

The expanding understanding of RNA biology has cemented RNA as a viable and promising target for therapeutic intervention in a wide range of diseases, from viral infections to cancer and neurological disorders [34]. The primary strategy involves developing drug-like small molecules that can bind directly to specific, structured RNA elements and modulate their function. This approach offers potential advantages over traditional protein-targeting drugs and oligonucleotide-based therapies, including more favorable pharmacological properties and the ability to allosterically regulate RNA activity [34].

Significant successes have been achieved, particularly in targeting viral RNAs and bacterial riboswitches. For instance, the HIV-1 RNA genome contains several highly conserved structural elements that have been successfully targeted with small molecules to inhibit viral replication [34]. Similarly, bacterial riboswitches, which are structured RNA elements in the untranslated regions (UTRs) of mRNAs that bind metabolites to regulate gene expression, represent attractive targets for novel classes of antibiotics [34]. The following diagram illustrates the general mechanism of action for small molecules targeting functional RNA structures.

Clinical Efficacy and Approved Therapies

The field of RNA-targeted therapeutics has progressed from a theoretical concept to clinical reality. A landmark achievement was the 2020 FDA approval of risdiplam (Evrysdi) for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) [34]. Risdiplam is a small molecule that functions as a splicing modulator, specifically targeting the survival motor neuron 2 (SMN2) pre-mRNA. By binding to this RNA, it promotes the inclusion of exon 7, leading to the production of a functional SMN protein and addressing the root cause of the disease [34].

Beyond small molecules, the broader category of RNA therapeutics has seen rapid growth. As of 2025, the global pipeline includes more than 3,200 active clinical trials for gene, cell, and RNA therapies, with several new RNA-based approvals each quarter [39]. Recent approvals include mRNA vaccines for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) prophylaxis and novel siRNA-based treatments [39]. This explosive growth underscores the translational potential of foundational RNA bioscience research.

The roles of RNA as hereditary information in viruses and as the proposed central molecule of the RNA World are not merely historical or pathological footnotes; they are foundational pillars of modern RNA bioscience. These principles illuminate the functional versatility of RNA—from storing genetic information and catalyzing reactions to fine-tuning gene expression—and provide a profound evolutionary context for its central role in biology. The continued development of sophisticated research methodologies, such as RNA-seq and structure-based small molecule design, is enabling researchers to deconstruct the complexities of viral pathogenesis and probe the ancient origins of life. Furthermore, this deep mechanistic understanding is being directly translated into a new class of therapeutics that target RNA, as evidenced by the clinical success of drugs like risdiplam and the expanding pipeline of RNA-targeting candidates. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these core principles is no longer optional but essential for driving the next wave of innovation in biotechnology and medicine.