RNA Degradation in Bulk RNA-seq: A Comprehensive Troubleshooting Guide from Basics to Advanced Correction

This article provides a complete framework for understanding, troubleshooting, and correcting RNA degradation in bulk RNA-seq experiments.

RNA Degradation in Bulk RNA-seq: A Comprehensive Troubleshooting Guide from Basics to Advanced Correction

Abstract

This article provides a complete framework for understanding, troubleshooting, and correcting RNA degradation in bulk RNA-seq experiments. It covers foundational concepts of RNA decay mechanisms and their impact on data quality, methodological guidance for sample preparation and technology selection, advanced computational and experimental correction strategies, and validation frameworks for ensuring reliable biological conclusions. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current best practices to empower robust transcriptomic studies even with challenging sample types, thereby unlocking the potential of valuable clinical and archival specimens.

Understanding RNA Degradation: Mechanisms, Metrics, and Impact on Transcriptome Data

A predictive understanding of RNA cellular function requires a transition from a static to an ensemble view, where populations of conformational states are defined by their free energy landscapes [1]. A critical finding over the past decade is that the cellular environment actively redistributes these RNA ensembles, changing the abundances of functionally relevant conformers relative to in vitro contexts [1]. This fundamental difference underlies the stark contrast between RNA decay pathways operating inside living cells versus those occurring in extracted samples. For researchers relying on bulk RNA-seq data, recognizing this distinction is not merely academic; it is essential for accurate experimental design and interpretation, as the very integrity of your RNA sample is governed by different biochemical principles from the moment of cell lysis.

FAQ: Cellular versus Ex Vivo RNA Decay

What are the primary mechanisms of RNA decay in a cellular environment?

In mammalian cells, RNA decay pathways are highly specialized and not redundant. Key cytoplasmic pathways include [2]:

- 5'-3' Decay (XRN1-mediated): This is the primary pathway for bulk mRNA turnover. It is initiated by the removal of the 5' cap, followed by exoribonucleolytic degradation by XRN1 [2].

- 3'-5' Decay (SKIV2L/Exosome-mediated): This pathway is universally recruited by ribosomes and primarily functions in translation surveillance. It tackles aberrant translation events and can modulate mRNA abundance. The SKIV2L helicase is a core component of the Ski complex that channels RNAs to the exosome for degradation [2].

- Crosstalk with Translation: There is extensive coupling between RNA decay and translation. For example, RNA cleavage at stalled ribosomes generates fragments that are cleared by these pathways. The SKIV2L complex is specifically and pervasively recruited to ribosome-occupied regions [2].

How does RNA decay in a test tube (ex vivo) differ from decay inside a cell?

Ex vivo decay is an unregulated, predominantly enzymatic process that occurs after the complex homeostasis of the cell has been disrupted.

- Loss of Compartmentalization: Upon cell lysis, RNAs are released from ribonucleoprotein complexes and subcellular compartments that offer protection, making them immediately vulnerable to RNases.

- Absence of Active Surveillance: The highly specific, translation-coupled surveillance pathways (like SKIV2L's function) cease to operate. Decay is no longer linked to the RNA's functional status.

- Environmental Shock: The extracted RNA is exposed to a new chemical environment (e.g., pH, salt concentrations) that can destabilize RNA structures and activate or introduce RNases, leading to rapid, nonspecific fragmentation [1] [3].

Why is sample quality so critical for RNA-seq, and what are the key metrics?

The quality of the initial RNA samples is the single-most important factor for a successful RNA-seq experiment [4]. Differential degradation of RNA between samples can be mistaken for biologically relevant differential expression [4].

- RNA Integrity Number (RIN): An objective score (1-10) generated by systems like the Agilent TapeStation, with 10 representing the highest quality. For RNA-seq, RIN scores of 7-10 are recommended, with a narrow range (1-1.5) within a sample set [4].

- Purity Ratios: Determined by spectrophotometry (e.g., NanoDrop). The 260/280 ratio should be ~2.0 for pure RNA, and the 260/230 ratio should be 2.0-2.2. Significant deviations indicate contamination by protein or organics [4].

Which RNA-seq library preparation method should I use for degraded or low-input samples?

The standard poly(A) enrichment method is highly inefficient for degraded RNA, as it requires an intact poly(A) tail. The following table summarizes the performance of alternative methods based on comparative studies [3] [5]:

Table 1: Comparison of RNA-seq Methods for Non-Ideal Samples

| Method Type | Representative Kits | Key Principle | Best Use Case | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ribosomal RNA Depletion | TruSeq Ribo-Zero, SMART-Seq with rRNA depletion | Removes abundant rRNA using capture probes; does not rely on 3' poly(A) tail. | Degraded RNA samples; profiling both coding and non-coding RNAs. | Shows clear performance advantages for degraded RNA, generating more accurate and reproducible results even at very low inputs (1-2 ng) [5]. With depletion, performance improves due to increased useful reads [3]. |

| Exome Capture | TruSeq RNA Access | Uses probes to target and enrich known exons. | Highly degraded RNA (e.g., FFPE samples). | Performs best on highly degraded samples, generating reliable data down to 5 ng input [5]. Generates a high percentage of exonic reads. |

| Random Primer-Based | SMART-Seq, xGen Broad-range, RamDA-Seq | Uses random primers for cDNA synthesis instead of oligo-dT; can include template-switching. | Low-input RNA and degraded RNA. | SMART-Seq has relative advantages for very low-input (e.g., 10 pg) and degraded RNA. Performance for RamDA-Seq decreases under these conditions [3]. |

What are the best practices for tissue and cell isolation to preserve RNA integrity?

- Immediate Stabilization: Total RNA purification should immediately follow tissue/cell isolation to prevent alterations in the transcript profile. If immediate isolation is not possible, use stabilization reagents like RNALater [4].

- Protocol Consistency: Once an isolation and storage protocol is established, use it for all samples in a project. Variance in techniques can create artifacts later misidentified as biological changes [4].

- RNA Isolation Method: The use of Trizol alone is often not recommended, as it can leave contaminating proteins and organics. Many core facilities recommend a combination of Trizol (for yield) followed by a column-based cleanup like RNeasy (for purity) [4].

Troubleshooting Guide: Sample Quality and RNA Degradation

Problem: Low RIN scores in my samples.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Delay between tissue collection and homogenization/stabilization.

- Solution: Minimize this delay as much as possible. Immediately place small tissue pieces in RNALater or directly homogenize in lysis buffer.

- Cause: Inefficient inactivation of RNases during extraction.

- Solution: Ensure lysis buffers are fresh and used in the correct volume-to-tissue ratio. Use a column-based purification method or a Trizol-column hybrid protocol for purer RNA [4].

- Cause: Repeated freeze-thaw cycles of either tissue or isolated RNA.

- Solution: Aliquot RNA into single-use portions to avoid repeated freezing and thawing.

Problem: My RNA is degraded, but I still need to proceed with RNA-seq.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Using a standard poly(A) enrichment protocol on degraded RNA.

- Cause: Low RNA input amounts leading to failed libraries.

- Solution: Use a method specifically designed for low-input RNA, such as SMART-Seq, which employs template-switching to generate full-length cDNA from low amounts of degraded RNA [3].

Problem: My RNA is pure but my sequencing results seem biased.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Batch effects from processing samples in different batches, with different reagents, or by different personnel.

- Solution: Employ batch correction algorithms in your data analysis. For example, the ComBat-Seq tool is designed to correct for batch effects in bulk RNA-seq count data. Ensure your experimental design includes replication and, if possible, balances conditions of interest across batches [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for RNA Integrity Management

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Key Application in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|

| RNALater | RNA Stabilization Solution | Preserves RNA integrity in tissues and cells immediately after collection when immediate RNA extraction is not feasible [4]. |

| RNeasy Kits (Qiagen) | Column-Based RNA Purification | Produces very pure preparations of total RNA, free of protein and organic contamination, which is essential for downstream sequencing [4]. |

| Trizol Reagent | Monophasic Lysis Solvent | Effective for simultaneous dissociation of biological material and isolation of RNA from complex tissues; often used in combination with a subsequent column cleanup [4]. |

| Ribo-Zero Kits | Ribosomal RNA Depletion | Removes ribosomal RNA from total RNA samples, enabling RNA-seq on degraded samples where poly(A) enrichment would fail [5]. |

| SMART-Seq Kits | cDNA Synthesis & Library Prep | Utilizes random priming and template-switching to generate sequencing libraries from low-input and degraded RNA samples [3]. |

| RNA Access Kits | Exome-Capture Library Prep | Uses targeted probes to enrich for coding exons, making it the preferred method for highly degraded samples like those from FFPE tissue [5]. |

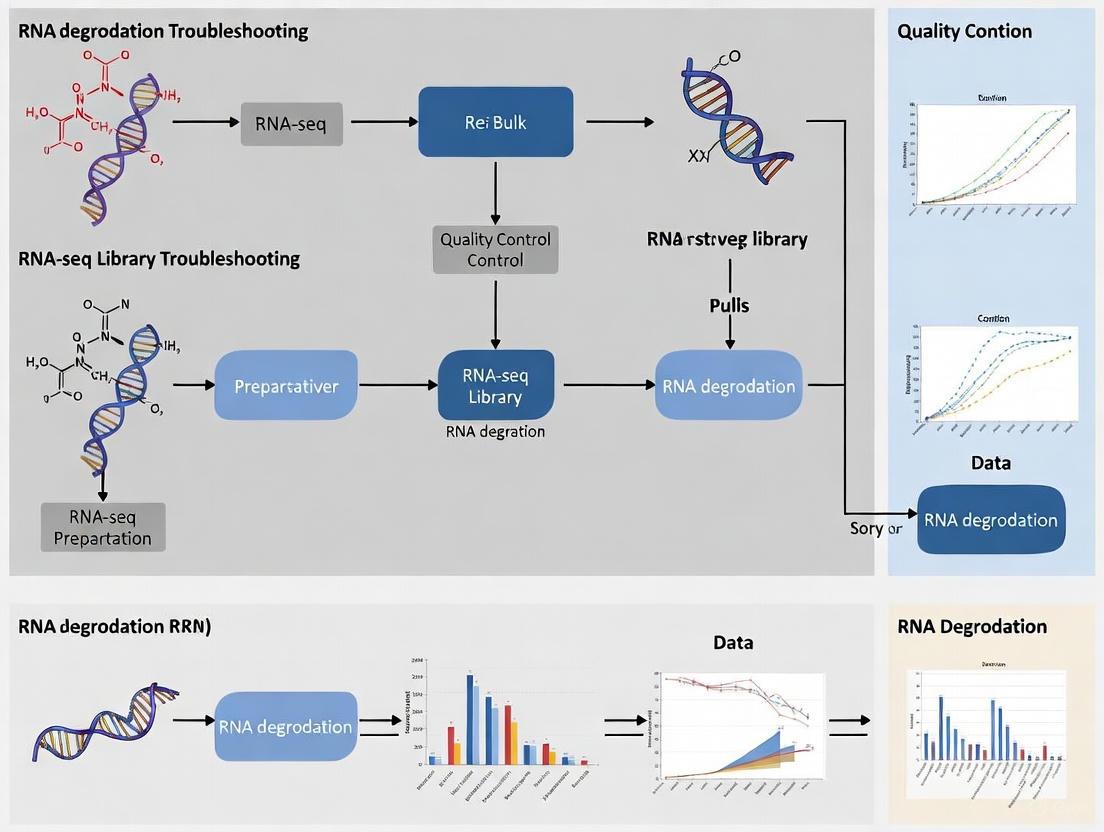

Visual Guide: RNA Decay Pathways and Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the specialized and non-redundant nature of mammalian cytoplasmic RNA decay pathways, highlighting their extensive crosstalk with translation.

Diagram 1: Specialized Mammalian RNA Decay Pathways. The 5'-3' pathway (XRN1) handles bulk turnover, while the 3'-5' pathway (SKIV2L/exosome) is specialized for translation surveillance. AVEN and FOCAD are factors that interact with the Ski complex to counteract ribosome stalling [2].

The workflow below outlines a logical decision process for designing RNA-seq experiments when sample quality is a concern.

Diagram 2: RNA-seq Protocol Selection for Suboptimal Samples. A decision workflow to guide the choice of library preparation method based on RNA integrity (RIN) and quantity [3] [5].

This guide provides a comprehensive resource for troubleshooting RNA quality issues in bulk RNA-seq experiments. High-quality, intact RNA is a critical starting point for generating reliable and reproducible gene expression data. The following sections address common questions and problems, offering detailed methodologies and solutions to ensure the success of your research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) and how is it interpreted?

The RNA Integrity Number (RIN) is a numerical value assigned to an RNA sample that indicates its degree of integrity. It is calculated using an algorithm developed by Agilent Technologies that analyzes the entire electrophoretic trace of an RNA sample run on a microfluidics-based platform, such as the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer [7] [8] [9].

The RIN scale ranges from 1 to 10 [7] [8]:

- RIN 10-9: Pristine, totally intact RNA.

- RIN 8-7: High to moderate quality, suitable for most downstream applications.

- RIN 6-5: Partially degraded, may be suitable for some assays but not for others.

- RIN <5: Highly degraded, generally unsuitable for most sensitive applications like RNA-seq.

FAQ 2: My RNA has a low RIN. Is it still usable for my experiment?

It depends on your downstream application. Different molecular techniques have different tolerance levels for RNA degradation. The table below summarizes general RIN guidelines for common applications [7]:

| Application | Recommended RIN | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq) | 8 - 10 | Ensures full-length transcript representation for accurate mapping and isoform analysis. |

| Microarray | 7 - 10 | Requires high integrity for specific probe hybridization. |

| qPCR | >7 | Optimal for amplifying specific targets, though shorter amplicons may tolerate lower RIN. |

| RT-qPCR | 5 - 6 | Can be more tolerant if the target amplicon is short. |

| Gene Arrays | 6 - 8 | May tolerate moderate degradation depending on the platform. |

It is crucial to note that RIN primarily reflects the integrity of ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which is the most abundant RNA species. It is not always a direct measure of messenger RNA (mRNA) integrity, which is often the target of interest [10]. For critical samples with low RIN, validating the integrity of your target mRNA (e.g., using the differential amplicon approach) is recommended [8].

FAQ 3: What are the limitations of the RIN metric?

While RIN is a widely used and valuable tool, it has several limitations:

- rRNA-Based: It assesses rRNA integrity, not mRNA integrity, and the two can degrade differently [10].

- Sample Type Specificity: The standard RIN algorithm was designed for mammalian RNA. It can be unreliable for plant samples or samples containing mixtures of eukaryotic and prokaryotic RNA (e.g., in host-pathogen studies) because it cannot differentiate between their different ribosomal RNA species [8].

- Not a Predictor of Success: A specific RIN value does not automatically guarantee the success of a downstream experiment. The required quality must be validated for each application and sample type [7] [10].

FAQ 4: What are the alternatives to RIN for assessing RNA quality?

Several other methods exist to evaluate RNA quality:

- Traditional Agarose Gel Electrophoresis: Intact total RNA from a eukaryotic source will show two sharp bands for the 28S and 18S rRNAs, with the 28S band approximately twice as intense as the 18S band. Degraded RNA appears as a smear [11] [12].

- UV Spectrophotometry: Measures absorbance at 230nm, 260nm, and 280nm to determine sample concentration and purity (e.g., A260/A280 ratio of ~1.8-2.0 for pure RNA). It does not directly assess integrity [12].

- Fluorescent Dye-Based Quantification: Very sensitive for determining RNA concentration but provides no information about integrity or purity [12].

- RNA Quality Indicator (RQI): A similar metric to RIN provided by Bio-Rad's Experion system, also on a 1-10 scale [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Consistently Low RIN Scores

A low RIN score indicates RNA degradation. This is one of the most common problems in RNA work, as RNases are ubiquitous in the environment.

- Cause 1: RNase Contamination.

- Cause 2: Improper Sample Handling or Storage.

- Solution:

- Tissues: Flash-freeze tissues immediately after collection in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C. Alternatively, use commercial RNA stabilization reagents that inactivate RNases at non-freezing temperatures [13].

- RNA Eluate: After purification, store RNA at -80°C. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles; instead, aliquot the RNA for single-use [7].

- Solution:

- Cause 3: Suboptimal RNA Extraction.

Problem: Low RNA Yield

- Cause 1: Insufficient Homogenization or Lysis.

- Solution: Increase homogenization time. For tough tissues, ensure the lysis buffer is in sufficient volume and fully covers the sample. Centrifuge the lysate to pellet debris before loading the column [13].

- Cause 2: Column Binding Issues.

- Solution: Do not overload the purification column. Ensure the correct amount of starting material and ethanol (if required) is used for optimal binding conditions [13].

- Cause 3: Incomplete Elution.

- Solution: After adding nuclease-free water to the column membrane, incubate at room temperature for 5-10 minutes before centrifuging. A second elution step can increase yield but will dilute the sample [13].

Problem: DNA or Protein Contamination in RNA Prep

- Cause 1: Genomic DNA Contamination.

- Solution: Perform a DNase I digestion, either on-column during purification or in-tube after elution [13].

- Cause 2: Protein Contamination.

- Cause 3: Guanidine Salt Contamination.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Equipment

The following table lists key materials and instruments used for RNA quality assessment and troubleshooting.

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer | Microfluidics-based instrument for electrophoretic separation and analysis of RNA, providing RIN calculation [11] [9]. |

| RNA 6000 Nano/Pico LabChip Kit | Disposable chips used with the Bioanalyzer for RNA analysis [11] [9]. |

| DNase I, RNase-free | Enzyme used to digest and remove contaminating genomic DNA from RNA preparations [13]. |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | Reagents that permeate tissues/cells and inactivate RNases, preserving RNA integrity at non-freezing temperatures during sample collection and storage [13]. |

| SYBR Gold / SYBR Green II | Highly sensitive fluorescent nucleic acid gels stains, less hazardous than ethidium bromide, allowing visualization of small amounts of RNA [11] [12]. |

| Spike-in RNA Controls | Synthetic RNA sequences added to samples before library prep to monitor technical performance and normalization in RNA-seq experiments [14]. |

Experimental Workflows and Visualization

Workflow 1: Comprehensive RNA Quality Assessment

This diagram illustrates the standard workflow for isolating and rigorously assessing RNA quality, incorporating multiple checkpoints to diagnose common issues.

Workflow 2: Interpreting Electropherogram and RIN

This diagram shows the key features of an electrophoretic trace (electropherogram) that the RIN algorithm analyzes, and how these features change with degradation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary signs that my RNA-seq data is affected by degradation-induced 3' bias?

The most common signs include a significant drop in read coverage from the 3' end to the 5' end of genes when visualized in gene body coverage plots [15]. This is often accompanied by reduced alignment efficiency and an increase in intergenic reads [16]. In severe cases, you may observe a lower percentage of uniquely mapped reads and a loss of information about splice variants due to incomplete coverage of the full transcript length [17] [16].

Q2: Can I still use RNA samples with low RIN values for RNA-seq?

Yes, but with caution. While Illumina recommends RIN values of at least 8 for their standard mRNA workflows [16], studies have shown that data from degraded samples (with RINs as low as 3.8) can be utilized if appropriate statistical corrections are applied [18]. The key is to ensure that RNA quality is not confounded with your experimental groups. If all samples are degraded to a similar extent, or if you explicitly control for RIN in your statistical model, you may recover biologically meaningful signals [18] [19].

Q3: How does RNA degradation lead to misleading differential expression results?

Degradation can introduce two main problems. First, if degradation affects your experimental groups differently, it can create false positives - genes that appear differentially expressed due to quality imbalances rather than biology [19]. One study of 40 clinical datasets found that 35% had significant quality imbalances, which inflated the number of differentially expressed genes [19]. Second, different transcript types degrade at different rates; for example, longer transcripts and those with higher GC content may degrade faster, creating artificial expression patterns [16].

Q4: What computational methods can correct for degradation biases?

While standard normalization methods often fail to fully account for degradation effects [18], specialized approaches show promise. Explicitly controlling for RIN using linear models can correct for most effects when RIN isn't associated with the variable of interest [18] [20]. For library-specific biases in multiplexed studies, methods like NBGLM-LBC (Negative Binomial Generalized Linear Model - Library Bias Correction) have been developed to correct gene-specific bias patterns [21]. Tools like seqQscorer use machine learning to automatically detect quality issues that might require such corrections [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Severe 3' Bias in Gene Body Coverage

Description You observe uneven coverage across transcripts, with sharp decreases toward the 5' end, despite acceptable RIN scores (>8).

Root Causes

- Degraded RNA input: Even with good RIN, partial degradation preferentially affects 5' ends [18] [16].

- Oligo-dT priming bias: Standard mRNA-seq protocols using oligo-dT enrichment naturally enrich for 3' fragments, which is exacerbated with any degradation [17] [15].

- Library preparation issues: Over-amplification or suboptimal fragmentation can worsen 3' bias [17].

Solutions

- Wet-lab: Use rRNA depletion instead of poly-A selection to avoid 3' enrichment [17]. For degraded samples, use random priming instead of oligo-dT during reverse transcription [17]. Increase RNA input amount to compensate for degradation [17].

- Computational: For mild bias, count reads only in the 3' regions consistently covered across all samples [15]. For severe cases with RIN confounding, use linear models that include RIN as a covariate [18].

Problem: Reduced Library Complexity

Description Your sequencing data shows high duplication rates, low molecular diversity, and poor detection of low-abundance transcripts.

Root Causes

- Low-quality/quantity input RNA: Degraded samples have fewer intact molecules, reducing diversity [18].

- Over-amplification: Too many PCR cycles during library prep amplify limited starting material, creating duplicates [17] [22].

- Inefficient fragmentation: Under-fragmentation or over-fragmentation reduces molecule diversity [17].

Solutions

- Wet-lab: Use unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to distinguish biological duplicates from technical duplicates [21]. Optimize PCR cycles - use just enough for library amplification without overcycling [17] [22]. For single-cell or low-input RNA-seq, consider multiple displacement amplification (MDA) as an alternative to PCR [17].

- Computational: Utilize UMI-aware preprocessing tools to collapse duplicates [21]. For bulk RNA-seq without UMIs, apply duplication-aware analysis methods.

Problem: Transcript Loss and Incomplete Annotation

Description Certain transcripts are missing or underrepresented, particularly those with low abundance, long length, or specific sequence features.

Root Causes

- Differential degradation rates: Transcripts degrade at different rates based on length, GC content, and biological function [18] [16].

- RNA extraction method bias: Some purification methods preferentially recover certain RNA types [17].

- Sequence-specific bias: During library prep, certain sequences may amplify less efficiently [17] [23].

Solutions

- Wet-lab: Use high-quality RNA extraction methods optimized for your RNA type (e.g., mirVana kit for small RNAs) [17]. Add PCR enhancers like TMAC or betaine for AT/GC-rich transcripts [17]. Use non-crosslinking fixatives instead of formalin for sample preservation [17].

- Computational: Apply sequence-specific bias correction tools that learn bias parameters during quantification [23]. Use spike-in controls to normalize for differential recovery [21].

Table 1: Effects of RNA Degradation on Sequencing Metrics Based on RIN Values

| RIN Value | Sequencing Metric | Impact | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9.3 (0 hours decay) | Uniquely mapped reads | Highest mapping rate | Romero et al. 2014 [18] |

| 7.9 (12 hours decay) | Intergenic reads | Increasing trend | Illumina Knowledge Base [16] |

| 3.8 (84 hours decay) | Library complexity | Significant loss | Romero et al. 2014 [18] |

| <8 (General) | 3' bias | Pronounced | Illumina Knowledge Base [16] |

| Variable | Detection of splice variants | Compromised | Illumina Knowledge Base [16] |

| Low RIN | RPKM values | Positively correlated with RIN | Illumina Knowledge Base [16] |

Table 2: Comparison of RNA Extraction Methods and Their Biases

| Method | Best For | Limitations | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRIzol (phenol:chloroform) | Long mRNAs | Small RNA loss at low concentrations | Use high RNA concentrations or avoid for small RNAs [17] |

| Column-based (Qiagen) | High-quality RNA | May not purify all RNA types equally | Combine with specific kits for specialized applications [17] |

| mirVana miRNA isolation | Small RNAs and high-quality total RNA | - | Recommended as best overall for yield and quality [17] |

| FFPE-compatible methods | Archived tissues | Cross-linked nucleic acids, modified bases | Use non-cross-linking fixatives when possible [17] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Assessing Degradation Effects Using Controlled RNA Decay

This protocol is adapted from the experimental design used by Romero et al. (2014) to systematically quantify degradation effects [18].

Materials

- Fresh PBMCs or cell line of interest

- RNA stabilization reagent (e.g., RNALater) and standard RNA extraction kits

- Equipment: BioAnalyzer or TapeStation for RIN assessment, sequencing platform

Methodology

- Sample processing: Divide fresh PBMC samples into multiple aliquots (8 time points recommended).

- Controlled decay: Leave aliquots at room temperature for varying durations (0, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, 72, 84 hours) before RNA extraction.

- RNA extraction: Extract RNA using a consistent method across all time points.

- Quality assessment: Measure RIN values for all samples, expecting a range from ~9.3 (0 hours) to ~3.8 (84 hours).

- Library preparation: Prepare sequencing libraries using standard poly-A enrichment protocol.

- Spike-in controls: Add non-human control RNA to each sample to monitor degradation effects.

- Sequencing: Sequence all libraries to equal depth (e.g., ~12 million reads per library).

- Data analysis: Map reads, calculate RPKM values, and perform principal component analysis to visualize RIN-associated variation.

Expected Outcomes This experiment will demonstrate how RNA quality affects sequencing metrics, showing the progression of 3' bias, changes in library complexity, and the proportion of reads mapping to spike-in controls versus endogenous transcripts.

Protocol: Computational Correction for RIN Effects

This protocol implements the linear model approach described by Romero et al. (2014) to correct for degradation effects [18].

Input Data

- Gene expression matrix (counts or RPKM values)

- RIN values for all samples

- Experimental design matrix (group assignments)

Implementation Steps

- Quality assessment: Check that RIN values are not completely confounded with experimental groups.

- Model formulation: For each gene, fit a linear model: Expression ~ Group + RIN

- Parameter estimation: Estimate the effect of RIN on each gene's expression.

- Bias correction: Adjust expression values by removing the RIN-associated variation.

- Validation: Confirm that principal components no longer cluster by RIN rather than biological groups.

Applications This method is particularly valuable when working with valuable field samples or clinical specimens where RNA quality varies but cannot be recollected.

Visualization Diagrams

Diagram 1: RNA Degradation Introduces Multiple Biases That Lead to Misleading Differential Expression Results

Diagram 2: RNA-seq Workflow Showing Critical Points for Degradation Control

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Managing RNA Degradation Biases

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization Reagents (e.g., RNALater) | Preserves RNA integrity immediately after sample collection | Critical for field studies and clinical sampling where immediate freezing isn't possible [18] |

| High-Quality RNA Extraction Kits (e.g., mirVana) | Isolates intact RNA with minimal bias | Superior for recovering both large and small RNA species compared to TRIzol alone [17] |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Enriches for mRNA without 3' bias | Alternative to poly-A selection that avoids 3' bias with degraded samples [17] |

| UMI Adapters | Labels individual molecules before amplification | Distinguishes biological duplicates from technical PCR duplicates [21] |

| Spike-in Control RNAs | Exogenous RNA standards for normalization | Quantifies technical variation and recovery efficiency across samples [18] [21] |

| Bias-Reducing Polymerases (e.g., Kapa HiFi) | Reduces sequence-specific amplification bias | Prefer over standard polymerases for challenging templates [17] |

| PCR Additives (TMAC, betaine) | Improves amplification of difficult templates | Particularly useful for AT-rich or GC-rich transcript regions [17] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the critical pre-sequencing quality checks for my RNA samples? Each submitted RNA sample should undergo analysis to determine RNA integrity. A RIN (RNA Integrity Number) score is generated for each sample, ranging from 0 to 10. A RIN score of 7 or higher indicates that the RNA sample is of sufficient quality to proceed with library construction [24]. This check is vital for ensuring that RNA degradation has not compromised your sample.

My RNA yield is very low. Can I still proceed with RNA-seq? Yes, ultra-low input RNA-Seq methods have been developed to selectively amplify full-length transcripts with minimal bias. These are designed for samples yielding lower amounts of degraded RNA or containing only a few cells. However, these samples are prone to transcriptional bias and poor read mapping to exons, and typically require additional amplification steps and higher sequencing depths to boost data output [25].

What is the difference between mRNA-Seq and Total RNA-Seq? The key difference lies in the RNA species captured:

- mRNA-Seq uses poly(A) selection to enrich for messenger RNA (mRNA) transcripts, which have polyadenylated tails. This method captures primarily protein-coding RNA [25].

- Total RNA-Seq uses rRNA depletion to remove ribosomal RNA (rRNA). This allows for the comprehensive analysis of both protein-coding mRNA and long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), many of which lack a poly(A) tail [25] [24].

How is RNA degradation identified in the raw sequencing data? After sequencing, quality control (QC) checks are performed on the raw data using tools like FastQC. Diagnostic plots are created for each sample to determine its quality. Aberrant samples resulting from degraded mRNA can be detected during this step. The results from multiple samples can be aggregated using tools like MultiQC for a convenient overview [26].

My sample has a low RIN score. How will this affect my data analysis? RNA degradation leads to a bias in the sequencing read coverage across transcripts. In a high-quality sample, reads will be uniformly distributed across genes. In a degraded sample, there will be a significant 3' bias, where a higher proportion of reads originate from the 3' end of transcripts. This bias can complicate transcript quantification and identification, and you may need to consider specific bioinformatic tools designed for 3'-biased data.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low RNA Quality or Yield

Symptoms:

- Low RIN score (<7) from Bioanalyzer or TapeStation analysis.

- Low RNA concentration, insufficient for standard library preparation protocols.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Improper tissue collection or storage. | Flash-freeze tissue samples immediately after collection in liquid nitrogen. Ensure samples are stored at -80°C. |

| Partial RNA degradation during extraction. | Use fresh, RNase-free reagents and consumables. Perform RNA extraction in a clean, dedicated workspace. |

| Starting material is limited (e.g., laser-capture microdissected cells, fine needle aspirates). | Switch to an ultra-low input RNA-Seq protocol. These methods use selective amplification to work with total RNA inputs of less than 500 ng or from fewer than 10,000 cells [25]. |

Validation: After repeating the extraction, re-check the RNA concentration and integrity using a Bioanalyzer, TapeStation, or similar instrument.

Problem: High Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) Contamination in Sequencing Data

Symptoms: An abnormally high percentage of sequencing reads align to ribosomal RNA genes, reducing the informative reads from your transcripts of interest.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Inefficient rRNA depletion during library prep. | For samples where non-polyadenylated RNAs (like many lncRNAs) are of interest, ensure the rRNA depletion protocol is optimized. |

| Using poly(A) selection on partially degraded RNA. | Degraded RNA may have lost poly(A) tails. If RNA quality is suboptimal, rRNA depletion (Total RNA-Seq) is a more robust selection method than poly(A) selection [25]. |

| Incorrect library selection for experimental goals. | If your goal is to study both coding and non-coding RNA, proactively choose Total RNA-Seq over mRNA-Seq for your project design [25] [24]. |

Validation: Check the alignment reports from your sequencing data. The percentage of reads mapping to rRNA should be low (e.g., <5% for a good poly(A) selection).

Problem: 3' Bias in Read Coverage

Symptoms: Read coverage is not uniform across the length of the transcripts. Visualization tools (e.g., IGV) show a strong enrichment of reads at the 3' ends of genes.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| RNA degradation. | This is the most common cause. Improve RNA handling practices to prevent degradation, as outlined in the first troubleshooting guide. |

| Protocol-specific bias in ultra-low input or single-cell methods. | Be aware that some amplification steps in specialized protocols can introduce this bias. It is important to use the recommended data analysis pipelines that can account for this. |

Validation: Use tools like Picard's CollectRnaSeqMetrics or Qualimap to generate metrics on the 5' to 3' coverage bias for your samples.

Table 1: RNA-Seq Assay Selection Guide

| Assay Type | Target RNA | RNA Selection Method | Recommended for Degraded RNA? | Relative Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA-Seq | mRNA | Poly(A) Selection | No | $ [25] |

| Total RNA-Seq | mRNA + lncRNA | rRNA Depletion | Yes | $$ [25] |

| Ultra-Low Input RNA-Seq | mRNA | Poly(A) Selection | Yes (for low yield) | $$$ [25] |

| Small RNA-Seq | miRNA, siRNA, piRNA | Size Fractionation | N/A | $$ [25] |

Table 2: Key Quality Thresholds for RNA-Seq Experiments

| Metric | Minimum Threshold | Ideal Target | Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Integrity (RIN) | 7 [24] | >8.5 | Bioanalyzer / TapeStation |

| Sequencing Depth (Bulk RNA-Seq) | 20-30 million reads [24] | 50-100 million reads (for isoform detection) | Sequencing summary stats |

| Alignment Rate | >70% | >85% | STAR, HISAT2, etc. [27] |

| rRNA Alignment | <10% | <2% | Alignment summary stats |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing RNA Integrity Pre-Sequencing

Objective: To determine the integrity and quality of total RNA samples before proceeding with library construction.

Materials:

- Bioanalyzer or TapeStation instrument

- RNA Nano or RNA ScreenTape kit

- RNase-free tubes and tips

Methodology:

- Dilute a small aliquot of the extracted RNA (e.g., 1 µL) as required by the kit instructions.

- Load the sample onto the Bioanalyzer chip or TapeStation.

- Run the analysis software to generate an electrophoretogram and the RIN score.

- Interpretation: Intact RNA will show sharp peaks for the 18S and 28S ribosomal subunits. A RIN score of 7 or higher is considered acceptable for most standard RNA-seq applications [24].

Protocol 2: Standard mRNA-Seq Library Preparation

Objective: To convert purified total RNA into a sequencing library enriched for protein-coding transcripts.

Materials:

- Total RNA with RIN > 7

- Poly(A) selection beads (e.g., oligo(dT)-conjugated beads)

- Reverse transcription enzymes and primers

- Second-strand synthesis reagents (including dUTP for strand-specific protocols)

- Sequencing adapters and PCR amplification mix

Methodology:

- Poly(A) Selection: Incubate total RNA with oligo(dT) beads. mRNA binds to the beads, which are washed to remove other RNAs.

- Fragmentation: Elute and chemically fragment the purified mRNA.

- cDNA Synthesis: Perform reverse transcription to create first-strand cDNA. For strand-specific libraries, synthesize the second strand using dUTP instead of dTTP [25].

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate platform-specific sequencing adapters to the cDNA fragments.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the library to increase concentration for sequencing. In strand-specific protocols, the uracil-containing second strand is digested to preserve strand orientation [25].

Workflow Visualizations

RNA-Seq Quality Control Workflow

RNA-Seq Analysis Pipeline

Assay Selection for Challenging Samples

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Oligo(dT) Beads/Columns | Selects for polyadenylated mRNA molecules by hybridization, enriching for protein-coding transcripts during library preparation [25]. |

| rRNA Depletion Probes | Single-stranded DNA oligos complementary to ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequences are used to capture and remove rRNA, allowing comprehensive analysis of coding and non-coding RNA [25]. |

| Bioanalyzer/TapeStation | An instrument that performs microfluidic electrophoresis to assess RNA integrity and generate a RIN score, a critical pre-sequencing quality check [24]. |

| dUTP Nucleotides | Used in second-strand cDNA synthesis during strand-specific library preparation. Subsequent digestion of the uracil-containing strand preserves information about the original transcript's orientation [25]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide barcodes added to each molecule during library prep for ultra-low input and single-cell protocols. They help account for and correct PCR amplification bias [25]. |

Robust RNA-seq Workflows: Strategic Design from Sample Collection to Sequencing

This technical support guide provides best practices for sample collection and preservation, which are critical first steps in ensuring the success of your bulk RNA-seq experiments. Proper techniques are fundamental to a broader thesis on RNA degradation troubleshooting, as the integrity of your final sequencing data is profoundly influenced by decisions made at this initial stage. The following FAQs, troubleshooting guides, and structured summaries are designed to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals navigate the complexities of RNA stabilization.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is immediate RNA stabilization so crucial after sample collection? RNA degradation begins the moment a sample is harvested due to the release of endogenous RNases [28]. These enzymes are ubiquitous in biological samples and are highly stable, making rapid stabilization the single most important factor in preserving an accurate snapshot of the in vivo transcriptome. Immediate stabilization prevents these RNases from degrading your target RNAs, which can distort gene expression profiles and lead to inaccurate results in downstream RNA-seq analysis [28] [29].

2. What are the primary methods for stabilizing RNA in tissues and cells? The three most effective and common methods are [30]:

- Flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen: This instantly halts all enzymatic activity. It is critical that tissue pieces are small enough (e.g., <0.5 cm) to freeze almost instantaneously upon immersion [30].

- Immersion in stabilization solutions (e.g., RNAlater): These solutions rapidly permeate tissues, inactivating RNases without the need for immediate freezing. This is ideal for field work or when liquid nitrogen is not readily available [30] [29].

- Homogenization in chaotropic lysis buffers (e.g., TRIzol): These buffers contain strong denaturants like guanidinium isothiocyanate that simultaneously disrupt cells and inactivate RNases [28] [30].

3. How do I choose between flash-freezing and RNAlater? The choice depends on your experimental logistics and sample type [30] [29]:

- Flash-freezing is highly effective but requires consistent access to liquid nitrogen and sufficient freezer capacity (-80°C), which can be challenging for large, multi-center studies.

- RNAlater is a non-toxic, aqueous solution that allows samples to be stored at room temperature for short periods or at 4°C for about a week before long-term freezing, offering greater flexibility during sample collection [29]. However, tissue pieces must be thin enough for the solution to permeate quickly.

4. What are the best practices for storing purified RNA? For short-term storage (up to a few weeks), purified RNA can be stored at -20°C. For long-term preservation, store RNA at -70°C to -80°C [28] [30]. To prevent degradation from repeated freeze-thaw cycles, always divide your RNA into single-use aliquots in RNase-free water or a specialized RNA storage buffer [28] [30].

5. My RNA is degraded. Can I still use it for RNA-seq? Yes, in many cases. While high-quality RNA (RIN > 8) is ideal for standard mRNA-seq, several library preparation technologies are designed for degraded samples. For example, 3'-end sequencing methods (e.g., QuantSeq, BRB-seq) are robust to degradation because they only sequence the 3' end of transcripts. The MERCURIUS BRB-seq technology has been shown to provide high-quality transcriptome data for samples with RIN values as low as 2.2 [29]. For total RNA-seq of degraded samples, a higher sequencing depth (25-60 million paired-end reads) may be recommended [31].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common RNA Preservation and Collection Problems

The table below outlines frequent issues, their causes, and proven solutions.

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low RNA Yield | Incomplete tissue homogenization or disruption [32]. | - Use a more aggressive lysing matrix (e.g., bead beating).- For tissues, grind under liquid nitrogen before homogenization [28]. |

| Sample was improperly stored prior to processing [32]. | - Stabilize samples immediately upon collection via flash-freezing or immersion in RNAlater/TRIzol [30].- Store at -80°C until use. | |

| RNA Degradation | RNase contamination during handling [28] [32]. | - Designate an RNase-free workspace and decontaminate surfaces with RNase-inactivating reagents [28].- Wear gloves and change them frequently. |

| Slow stabilization after sample harvest, allowing endogenous RNases to act [28]. | - Optimize and accelerate the time between sample collection and stabilization/homogenization. | |

| DNA Contamination | Genomic DNA was not effectively removed during extraction [30] [32]. | - Perform an on-column DNase digestion during the RNA purification protocol. This is more efficient than post-purification treatment [30]. |

| Clogged Spin Columns | Tissue was not fully homogenized, leaving debris [32]. | - Centrifuge the lysate after homogenization to pellet debris before loading the supernatant onto the column [32]. |

| Too much starting material was used [32]. | - Reduce the amount of starting material to fall within the kit's recommended capacity [32]. |

Key Methodologies and Data Presentation

Comparison of Primary RNA Preservation Methods

The following table summarizes the core methodologies for stabilizing RNA immediately after sample collection.

| Preservation Method | Key Feature | Mechanism of Action | Ideal Sample Types | Storage Before Processing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flash-Freezing | Instantly halts all biological activity [30]. | Rapid temperature drop solidifies the sample, inactivating enzymes [30]. | Most tissues, cell pellets [30]. | Long-term at -80°C [30]. |

| Stabilization Solutions (e.g., RNAlater) | Permits storage at non-cryogenic temperatures [29]. | Rapidly permeates tissue, precipitating RNases out of solution [29]. | Tissues (must be small), cell pellets [30] [29]. | ~1 day at RT, ~1 week at 4°C, long-term at -80°C [29]. |

| Chaotropic Lysis Buffers (e.g., TRIzol) | Integrates stabilization with initial lysis [30]. | Denatures proteins and RNases upon contact [28] [30]. | All types, including difficult, nuclease-rich tissues [30]. | Lysates can be stored at -80°C for weeks [30]. |

RNA Quality Assessment Metrics

After extraction, it is vital to assess RNA quality using the following metrics.

| Metric | Description | Acceptable Range | Measurement Tool |

|---|---|---|---|

| RIN (RNA Integrity Number) | An algorithm-based assignment (1-10) of RNA quality, heavily based on ribosomal RNA peaks [33]. | ≥7 is often the minimum for standard mRNA-seq; 3'-end seq can tolerate lower values [33] [31]. | Bioanalyzer or TapeStation [30]. |

| DV200 | The percentage of RNA fragments larger than 200 nucleotides [33]. | >70% is generally good, but application-dependent [33]. | Bioanalyzer or TapeStation. |

| A260/A280 Ratio | Indicates protein contamination [30]. | 1.8 - 2.0 is acceptable for pure RNA [30]. | UV Spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop) [30]. |

| A260/A230 Ratio | Indicates contamination by salts or organics [32]. | >2.0 is desirable [32]. | UV Spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop) [30]. |

| medTIN (Median Transcript Integrity Number) | A computed metric from RNA-seq data that measures RNA integrity at the transcript level; more sensitive for degraded samples than RIN [33]. | Higher scores indicate better integrity; strong correlation with RIN [33]. | Calculated from RNA-seq alignment files [33]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in RNA Stabilization |

|---|---|

| Liquid Nitrogen | Used for instant flash-freezing of tissues and cell pellets to preserve RNA integrity [30]. |

| RNAlater Stabilization Solution | A non-toxic aqueous solution that permeates tissues to stabilize and protect RNA without immediate freezing [30] [29]. |

| TRIzol Reagent | A mono-phasic solution of phenol and guanidine isothiocyanate for the simultaneous disruption of cells and inactivation of RNases during sample homogenization; ideal for difficult samples [30]. |

| RNaseZap or RNase Erase | Surface decontamination solutions used to spray or wipe down benches, pipettes, and equipment to create an RNase-free environment [30] [32]. |

| PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes | Specialized blood collection tubes containing reagents for immediate stabilization of intracellular RNA in whole blood [28] [29]. |

| PureLink DNase Set | For on-column digestion of genomic DNA during RNA purification, effectively removing DNA contamination that could interfere with downstream applications [30]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

RNA Preservation Decision Workflow

This diagram outlines the logical decision process for choosing the most appropriate RNA preservation method based on sample type and experimental conditions.

Factors Influencing RNA Degradation

This diagram visualizes the key factors that contribute to RNA degradation, highlighting the relationship between different sources of RNases and environmental conditions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the fundamental difference between poly-A selection and ribo-depletion?

Poly-A selection is a positive enrichment method that uses oligo(dT)-coated magnetic beads to actively capture and isolate messenger RNA (mRNA) by binding to their polyadenylated tails. This method is ideal for focusing on mature, protein-coding RNAs [34] [35].

In contrast, ribo-depletion (or rRNA depletion) is a negative selection method that uses probes to hybridize to and remove ribosomal RNA (rRNA) from the total RNA pool. This leaves behind a broader range of RNA species, including both coding and non-coding RNAs [36] [37].

When should I choose poly-A selection for my experiment?

Choose poly-A selection when your research meets the following criteria [34] [36]:

- Goal: Your primary interest is in mature, protein-coding mRNA for applications like gene expression profiling or differential expression analysis.

- Sample Type: You are working with eukaryotic samples.

- RNA Quality: Your RNA is of high integrity, typically with an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) ≥ 7 or a DV200 value of ≥ 50%.

When is rRNA depletion the better option?

Opt for rRNA depletion in these scenarios [34] [36] [37]:

- Goal: You need to study non-polyadenylated RNAs, such as long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), pre-mRNAs, histone mRNAs, or bacterial transcripts.

- Sample Type: You are working with prokaryotic samples, or eukaryotic samples that are degraded or derived from Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tissues.

- RNA Quality: Your RNA is partially degraded (RIN < 7), as this method does not rely on an intact 3' poly-A tail.

What is 3' bias and how is it related to my RNA-seq method?

3' bias refers to the uneven coverage along a transcript where a disproportionately high number of sequencing reads map to the 3' end of the transcript compared to the 5' end [38]. This is a common artifact in RNA-seq data.

This bias is strongly associated with poly-A selection when the input RNA is degraded [36]. In degraded samples, the RNA fragments have lost their 5' ends, but the 3' fragments containing the poly-A tail are still efficiently captured by the oligo(dT) beads. rRNA depletion is less prone to this effect and typically provides more uniform coverage along the entire transcript length [36].

Can I combine poly-A selection and ribo-depletion?

For standard eukaryotic mRNA sequencing, combining these methods is generally unnecessary and not cost-effective [39]. Poly-A selection alone is highly effective at removing rRNA, typically resulting in a final rRNA content of less than 1% in the sequencing library [39]. Performing both procedures would add significant cost with minimal improvement in library purity for most mRNA-focused studies.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High 3' Bias in Poly-A Selected Libraries

Potential Cause: The most common cause is using degraded or low-quality RNA as starting material. When RNA is fragmented, the oligo(dT) beads can only capture fragments that still possess a poly-A tail, leading to an over-representation of the 3' ends of transcripts [36].

Solutions:

- Assess RNA Quality Rigorously: Before library preparation, always check RNA integrity using an instrument like the Agilent Bioanalyzer. For poly-A selection, aim for a RIN value of 7 or higher [34].

- Switch to Ribo-depletion: If your samples are inherently degraded (e.g., FFPE samples), the most effective solution is to use rRNA depletion instead of poly-A selection, as it does not rely on an intact 3' tail [36].

- Use Specialized Kits: For heavily degraded clinical samples, consider using specialized full-length transcriptome protocols designed for low-quality RNA, which often involve adding a poly-A tail to all RNA fragments before library construction [40].

Problem: High Residual rRNA in Ribo-depleted Libraries

Potential Cause: Inefficient removal of rRNA during the depletion step. This can be due to several factors, including the presence of inhibitors in the RNA sample, suboptimal hybridization conditions, or probe mismatch (especially in non-model organisms) [37].

Solutions:

- Ensure RNA Purity: Contaminants like salts, detergents, or alcohols can inhibit the hybridization of depletion probes to rRNA. Purify your total RNA samples using solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) beads, like AMPure XP, before starting the ribo-depletion protocol. This can reduce rRNA content from over 80% to below 5% [37].

- Verify Probe Specificity: Ensure that the ribo-depletion kit you are using is designed for your specific organism. For non-model organisms, custom probe design may be necessary [37].

- Remove Genomic DNA: Residual genomic DNA can be a source of contamination. Use a DNase I treatment step, but ensure the enzyme is completely inactivated afterward to prevent it from degrading the DNA probes used in the ribo-depletion step [37].

Comparison Tables

Table 1: Core Method Comparison: Poly-A Selection vs. Ribo-Depletion

| Feature | Poly-A Selection | Ribo-Depletion |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Positive selection via oligo(dT) binding | Negative selection via rRNA probe hybridization |

| Primary Target | Mature, polyadenylated mRNA | Both polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated RNA |

| Ideal RNA Integrity | High (RIN ≥ 7) | Tolerant of degraded/FFPE RNA |

| Coverage Bias | Prone to 3' bias with degraded RNA | More uniform coverage |

| Organism Compatibility | Eukaryotes only | Eukaryotes and prokaryotes |

| Typical Residual rRNA | < 1% [39] | 5-10% [37] |

| Sequencing Depth Needed | Lower (cost-efficient for mRNA) | Higher (to cover diverse RNA types) |

Table 2: Recommended Sequencing Depth for Different Experimental Goals

| Experimental Goal | Recommended Read Type | Recommended Depth (per sample) |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Profiling | 50 bp single-end or 75-100 bp paired-end | 20-30 million reads [34] |

| Alternative Splicing or Fusion Detection | 100 bp paired-end | ≥ 50 million reads [34] |

| Comprehensive Transcriptome Annotation | 100 bp paired-end | ≥ 100 million reads [34] |

Workflow Diagrams

Poly-A Selection Workflow

Ribo-Depletion Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for RNA-seq Library Preparation

| Reagent | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads | Captures polyadenylated RNA via base-pairing. | Core component of poly-A selection kits. Bead-to-RNA ratio is critical for yield [34]. |

| rRNA Depletion Probes | Sequence-specific DNA probes that hybridize to ribosomal RNA for removal. | Must be matched to the target organism (e.g., Human/Mouse/Rat, Bacterial panels) [37]. |

| High-Salt Binding Buffer | Stabilizes adenine-thymine (A-T) base-pairing during poly-A capture. | Essential for efficient and specific hybridization in poly-A selection [35]. |

| DNase I | Enzyme that degrades genomic DNA contaminants in RNA samples. | Critical for ribo-depletion; must be fully inactivated to protect single-stranded DNA probes [37]. |

| SPRI Beads (e.g., AMPure XP) | Solid-phase reversible immobilization beads for nucleic acid purification and size selection. | Used to clean up RNA samples and final libraries, removing impurities and short fragments [34] [37]. |

| Unique Dual Indexes (UDIs) | Barcode sequences ligated to samples for multiplexing. | Allows pooling of multiple libraries; dual indexing minimizes barcode misassignment [34]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What has a bigger impact on statistical power: increasing my sample size or increasing my sequencing depth?

Increasing your sample size generally has a more potent effect on statistical power than increasing sequencing depth, especially once a baseline depth is achieved. One comprehensive power analysis demonstrated that increasing the sample size is more effective for boosting power, particularly when sequencing depth reaches approximately 20 million reads per sample [41]. While deeper sequencing can help detect lowly-expressed transcripts, the statistical power gained from additional biological replicates to estimate biological variation far outweighs the benefits of excessive sequencing depth for most genes under this threshold [41] [42].

FAQ 2: How does RNA degradation impact my power calculations and sample size requirements?

RNA degradation is not uniform; different transcripts degrade at different rates, which can introduce substantial bias into your gene expression measurements [43]. This means that:

- Degradation inflates variability: It increases the technical variation in your data, which can reduce your effective statistical power.

- Standard normalization is insufficient: Common global normalization methods cannot fully correct for gene-specific degradation effects [44].

- Sample quality affects sample size: Samples with lower RNA Integrity Number (RIN) may require a larger sample size to achieve the same power as a study using only high-RIN samples. It is crucial to control for RNA quality, for example by including RIN as a covariate in your linear model, to recover the true biological signal [43].

FAQ 3: Are there specific tools to help me estimate sample size for my RNA-seq experiment?

Yes, several R/Bioconductor packages have been developed specifically for RNA-seq power and sample size estimation. These tools move beyond simplistic models to use real data distributions, which is critical for accurate planning.

- RnaSeqSampleSize: This tool uses distributions of gene average read counts and dispersions from real RNA-seq data (e.g., from public repositories like TCGA) to provide a realistic sample size estimate. It allows for power estimation for specific genes or pathways of interest [42].

- PROPER: This is a simulation-based method that offers a flexible framework for power exploration, allowing you to model complex experimental designs [45].

- RNASeqPower: This package provides a power analysis method based on the score test for single-gene differential expression analysis [42].

Power Analysis Data and Parameters

Key Parameters Influencing Statistical Power

The table below summarizes the major factors you must consider when designing a powered RNA-seq experiment.

| Parameter | Impact on Power | Practical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | Has the most significant impact; power increases with more biological replicates [41]. | Prioritize budget for more replicates over extreme sequencing depth. |

| Sequencing Depth | Important for detecting low-abundance transcripts; yields diminishing returns after ~20 million reads [41]. | Balance depth needs with the cost of additional samples. |

| Effect Size (Fold Change) | Larger fold changes are easier to detect and require fewer replicates [42]. | Base expected effect sizes on pilot data or previous literature. |

| Gene Expression Level | Lowly-expressed genes (e.g., many lincRNAs) require more power to detect differential expression [41]. | Stratify power analysis for different gene classes if they are the focus. |

| Biological Variation | High variability between samples (e.g., in human population studies) drastically reduces power [41]. | Use paired designs or stricter matching to control variability. |

| False Discovery Rate (FDR) | A stricter FDR (e.g., 0.01 vs. 0.05) requires more samples to maintain the same power [42]. | Choose an FDR threshold appropriate for your study's goals. |

| RNA Quality (RIN) | Low RIN scores increase noise and reduce effective power [43]. | Set a RIN threshold for sample inclusion and account for it in the model. |

Power and Sample Size Recommendations from Empirical Data

The following table summarizes findings from a large-scale simulation study based on six public RNA-seq datasets, providing a realistic view of sample needs [41].

| Experimental Factor | Impact on Required Sample Size | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Depth | Diminishing returns | Increasing depth beyond 20 million reads provided less power gain than adding more replicates. |

| Gene Type | Varies by expression level | Power for lincRNAs was consistently lower than for protein-coding mRNAs due to their lower expression. |

| Experimental Design | Major impact | Paired-sample designs (e.g., pre- vs. post-treatment) significantly enhanced statistical power by controlling for inter-individual variation. |

| Data Distribution | Critical for accuracy | Sample size estimation using real data-based distributions (e.g., with RnaSeqSampleSize) is more accurate than using a single conservative value for all genes [42]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Performing a Power Analysis Using Real Data Distributions

This protocol outlines the steps for using the RnaSeqSampleSize package or similar tools for robust sample size estimation [42].

- Identify a Suitable Reference Dataset: Find a publicly available RNA-seq dataset that closely resembles your planned experiment in terms of organism, tissue, and biological context (e.g., from TCGA or GEO).

- Define Your Parameters of Interest:

- Desired Power: Typically set at 0.8 or 80%.

- False Discovery Rate (FDR): Typically set at 0.05.

- Minimum Fold Change: The smallest effect size you wish to detect (e.g., 1.5x or 2x).

- Input Parameters into the Tool: Load the reference dataset and specify your parameters.

RnaSeqSampleSizewill use the empirical distributions of read counts and dispersion from the reference. - Run the Analysis and Interpret Output: The tool will calculate the necessary sample size per group. It can also generate power curves to visualize the relationship between sample size and power for your specific parameters.

- Consider Gene Subsets (Optional): If your study focuses on a specific pathway or class of genes, you can perform the power analysis using only those genes, as their expression characteristics may differ from the genome-wide average [42].

Protocol: Mitigating the Impact of RNA Degradation on Power

RNA degradation can introduce bias and noise, effectively reducing your study's power. This protocol describes steps to manage this issue [43] [44] [46].

- Prevention through Standardization:

- Standardize the time from sample collection to preservation or RNA extraction across all samples.

- Use storage stabilizers like RNAlater whenever possible.

- Handle all samples in the experiment identically to avoid introducing a systematic bias between groups.

- Quality Control and Inclusion Threshold:

- Quantify RNA integrity using the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) or similar metrics for all samples.

- Establish a pre-defined RIN cutoff for sample inclusion. While there is no universal standard, a common threshold is RIN ≥ 7 [46]. Justify your threshold based on pilot data or literature.

- Wet-Lab Adjustment:

- If using samples with lower RIN, consider using ribosomal RNA depletion instead of poly-A enrichment, as the latter is more sensitive to degradation.

- Bioinformatic Correction:

- During differential expression analysis, include the RIN score as a covariate in your linear model. This can correct for a majority of the degradation-induced bias, provided that RIN is not associated with the effect of interest [43].

- For more advanced correction, consider using a tool like DegNorm, which performs gene-by-gene normalization for degradation bias [44].

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

RNA-seq Experimental Design and Power Optimization Workflow

The Confounding Effect of RNA Degradation on Coverage

| Tool or Reagent | Function in Powering Your Study | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| RnaSeqSampleSize (R package) | Estimates sample size and power using real data distributions for accuracy [42]. | Requires a reference dataset from a similar biological context for best results. |

| PROPER (R package) | Provides a simulation-based framework for power analysis in complex designs [45]. | Useful for comparing different experimental designs before wet-lab work begins. |

| RNALater Stabilization Solution | Preserves RNA integrity in tissues and cells immediately after collection, preventing degradation [43]. | Critical for field studies or when immediate freezing is not possible. |

| Bioanalyzer/TapeStation | Provides accurate assessment of RNA Quality (RIN) prior to library prep [46]. | Essential QC; do not rely on Nanodrop alone for RNA quality. |

| Ribo-Zero Depletion Kits | An alternative to poly-A selection for rRNA removal; can be more robust for partially degraded RNA [44]. | Consider if working with samples known to have moderate RNA degradation (e.g., FFPE). |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Molecular barcodes that label individual mRNA molecules to correct for PCR duplication bias [47]. | Improves accuracy of transcript counting, especially in low-input or single-cell protocols. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary functions of spike-in controls in an RNA-seq experiment? Spike-in controls are synthetic, known quantities of foreign RNA transcripts added to your samples before library preparation. They serve two primary functions: to provide an external standard for quantitative calibration and to monitor technical performance. By creating a standard curve between the known input RNA concentration and the resulting read counts, they allow for more accurate estimation of absolute transcript abundances in your biological sample [48]. Furthermore, they help identify technical biases, such as those related to GC content or transcript length, and can be used to directly measure global error rates, like false antisense strand calls in stranded protocols [48].

2. My RNA samples are degraded (low RIN). Can I still use spike-ins to get reliable data? Yes. While RNA degradation significantly impacts data quality, spike-in controls are particularly valuable in these scenarios. Degradation often leads to 3' bias, where coverage is lost from the 5' end of transcripts, and can cause unexpected gene expression variation [16]. Spike-ins help monitor and quantify this bias. Furthermore, specialized methods like the MFE-GSB framework have been developed to correct for co-existing biases in sequencing data, which can be applied to achieve more reliable results from compromised samples [49]. For heavily degraded RNA (e.g., from FFPE samples), full-length transcriptome methods like MERCURIUS FFPE-seq are optimized to work with low RIN material and are compatible with spike-in strategies [40].

3. Why are biological replicates more important than sequencing depth? Biological replicates (measuring different biological units per condition) are essential for capturing the natural variation within a population. Without sufficient replicates, it is impossible to distinguish true biological differences from random noise. While sequencing depth increases the detection of lowly expressed transcripts, it does not account for biological variability. With only two replicates, the ability to estimate variability and control false discovery rates is greatly reduced, and a single replicate does not allow for any statistical inference [50]. Increasing the number of replicates improves the power to detect true differences in gene expression, especially when biological variability is high [50].

4. How can I correct for the effects of RNA degradation in my data analysis? If sample degradation is not uniform across groups, it can confound results. One effective method is to explicitly control for the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) during the statistical analysis of differential expression. Research has shown that by incorporating RIN as a covariate in a linear model framework (e.g., in tools like DESeq2 or edgeR), the majority of degradation-induced effects can be corrected, helping to recover the true biological signal [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Unexpected Results in Differential Expression Analysis

Potential Cause: Inadequate biological replication or unaccounted for batch effects. Solutions:

- Increase Replication: For hypothesis-driven experiments, avoid a single replicate per condition. While three replicates is often a minimum, more may be needed if biological variability is high [50]. A lack of replicates prevents robust statistical inference.

- Account for RNA Quality: If your samples have varying RIN values, include the RIN score as a covariate in your statistical model to correct for confounding effects of degradation [18].

- Minimize Batch Effects: Process and sequence samples from all experimental conditions in a randomized manner and on the same day to avoid introducing technical batch effects [46].

Problem 2: Suspected Technical Biases in Sequencing Data

Potential Cause: Biases introduced during library preparation or sequencing. Solutions:

- Use Spike-in Controls: Incorporate a spike-in mix like the ERCC RNA standards or SIRVs. Analyze the spike-in data to check for coverage biases, uneven GC content effects, and abnormal error rates [48] [51].

- Employ Bias-Correction Frameworks: Use computational tools like the MFE-GSB framework, which uses a self-benchmarking approach to correct for multiple co-existing biases at the k-mer level [49].

Problem 3: Working with Low-Quality or Degraded RNA

Potential Cause: RNA samples have degraded due to collection or storage conditions (e.g., FFPE tissues, field samples). Solutions:

- Choose a Specialized Protocol: Use RNA-seq methods specifically designed for degraded RNA, such as MERCURIUS FFPE-seq, which uses poly(A) tailing and barcoding to generate full-length coverage even from heavily fragmented RNA [40].

- Set a Realistic Quality Threshold: Establish a realistic RIN threshold for your sample type and study goals. While RIN ≥ 8 is often recommended, valuable data can be recovered from samples with RIN values as low as 4 using appropriate statistical corrections [18].

- Leverage 3' Bias-Mitigating Methods: If using standard poly-A selection protocols, be aware that degradation causes 3' bias. Consider quantification methods that are more robust to this bias or protocols that do not rely on intact poly-A tails [16] [40].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Spike-in RNA Controls

Purpose: To monitor technical performance and enable absolute quantification in RNA-seq experiments.

Materials:

- Commercially available spike-in RNA mixes (e.g., ERCC ExFold RNA Spike-In Mixes [48] or SIRVs [51])

- RNA samples

- Standard RNA library preparation kit

Methodology:

- Dilution: Prepare a working dilution of the spike-in mix according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Spike-in: Add a small, consistent volume of the spike-in mix to each of your RNA samples prior to the start of library preparation. A typical amount is 2% of the total RNA by mass [48].

- Library Preparation: Proceed with your standard RNA-seq library preparation protocol (e.g., poly-A selection, rRNA depletion) for all samples, including the spike-ins.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Sequence the libraries. During data analysis, the spike-in reads should be aligned to a dedicated reference file containing only the spike-in sequences. The known input concentrations and the observed read counts can then be used to generate a standard curve.

Protocol 2: Designing an Experiment with Biological Replicates

Purpose: To ensure robust and statistically powerful detection of differentially expressed genes.

Materials:

- Multiple biological units (e.g., cells from different cell culture flasks, tissues from different animals/patients)

Methodology:

- Define a Biological Replicate: A biological replicate is defined as data derived from an independent biological source (e.g., a different animal, patient, or a primary cell culture established from a different donor). Technical replicates (multiple libraries from the same RNA extract) are not a substitute.

- Determine Replicate Number: While the minimum standard is often three replicates per condition, the optimal number depends on the expected effect size and the biological variability in your system. Use power analysis tools (e.g., Scotty) if pilot data is available [50].

- Randomize Processing: To avoid confounding batch effects, randomly assign the biological replicates from different conditions to library preparation batches and sequencing lanes [46].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Common Spike-in RNA Controls

| Control Type | Source/Example | Key Features | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complex Mix (ERCC) | Synthetic sequences from B. subtilis and M. jannaschii [48] | Covers a wide (e.g., 2^20) concentration range; diverse GC content; minimal homology to mammalian genomes. | Assessing detection limits, dynamic range, and quantitative accuracy across expression levels. |

| Splicing Variants (SIRV) | Lexogen SIRV Suite [51] | Includes multiple alternatively spliced isoforms from a single gene. | Validating and benchmarking isoform-level quantification and splice junction detection. |

Table 2: Impact of Biological Replicate Number on RNA-seq Analysis

| Number of Replicates | Statistical Robustness | Key Limitations | Recommended Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 per condition | No statistical inference possible. | Cannot estimate biological variance or perform formal differential expression testing. | Exploratory, pilot studies only. |

| 2 per condition | Limited statistical power. | Greatly reduced ability to estimate variability and control false discovery rates [50]. | Not recommended for hypothesis-driven research. |

| 3 per condition | Allows for statistical testing. | Considered a minimum standard; may be underpowered for genes with low expression or high variability [50]. | Standard for many laboratory studies with controlled conditions. |

| >5 per condition | High statistical power and robustness. | Costly and computationally intensive. | Necessary for studies with high inherent variability (e.g., human cohorts, field samples). |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates how spike-in controls and biological replicates are integrated into a robust RNA-seq workflow for quality tracking.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| ERCC Spike-in Mixes | External RNA controls for absolute quantification and performance assessment. | Defined concentrations over a wide dynamic range; minimal sequence homology to eukaryotic genomes [48]. |

| SIRV Spike-in Mixes | Controls for validating isoform expression and splicing analysis. | Contains a set of synthetic alternatively spliced RNA variants of known sequence [51]. |

| UMI Adapters | Unique Molecular Identifiers to correct for PCR amplification bias and accurately count original RNA molecules. | Short random nucleotide sequences added to each molecule before amplification [40]. |

| RNase Inhibitors | Protect RNA samples from degradation during isolation and handling. | Essential for maintaining RNA integrity from sample collection through library prep. |

| Specialized FFPE-seq Kits | Library prep kits optimized for degraded RNA from formalin-fixed tissues. | Uses end-repair and poly(A)-tailing to barcode fragmented RNA, enabling full-length coverage [40]. |

Correcting Degradation Biases: Computational and Experimental Fixes

Why is Quality Control Critical in Bulk RNA-Seq?

In bulk RNA sequencing, the quality of your starting material is the most critical factor determining the success of your experiment. Analyzing a poor-quality sample can lead to biased, unreliable results and the waste of significant time and resources. The core challenge is establishing clear, quantitative cut-offs to objectively decide when a sample is of sufficient quality to sequence or when it should be excluded. This guide provides the necessary benchmarks and methodologies for making these decisions within the context of troubleshooting RNA degradation.

Key Quality Metrics and Exclusion Criteria

The following table summarizes the primary quantitative metrics used to evaluate sample quality for bulk RNA-seq, along with recommended pass/fail cut-offs.

| Quality Metric | Assessment Method | Recommended Cut-off | Rationale for Cut-off |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Integrity (RIN) | Agilent Bioanalyzer or TapeStation | RIN ≥ 7.0 [46] [52] | RIN values below 7 indicate significant RNA degradation, which introduces 3' bias and compromises quantification accuracy [46]. |

| RNA Concentration | Fluorometry (e.g., Qubit) | Depends on library prep kit | Ensures sufficient material for robust library preparation without excessive PCR amplification, which can introduce bias. |

| RNA Purity (Contaminants) | Spectrophotometry (e.g., NanoDrop) | A260/A280 ≈ 1.8 - 2.0A260/A230 > 2.0 [52] | Low A260/A280 suggests protein contamination. Low A260/A230 suggests guanidine salt or phenol contamination [52]. |

| % of rRNA in Sample | Bioanalyzer or RNA-seq alignment | Varies by protocol | High rRNA% (>30%) in poly(A)-selected libraries indicates failure of mRNA enrichment [53]. |

| Total Sequencing Reads | Sequencing output | ≥ 20-25 million reads/sample [53] | Fewer reads may not provide sufficient depth for accurate quantification of medium- and low-abundance transcripts. |