RNA-Binding Proteins: Master Regulators of Gene Expression and Emerging Therapeutic Targets

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical roles RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) play in post-transcriptional gene regulation, a rapidly advancing field with profound implications for understanding disease and developing...

RNA-Binding Proteins: Master Regulators of Gene Expression and Emerging Therapeutic Targets

Abstract

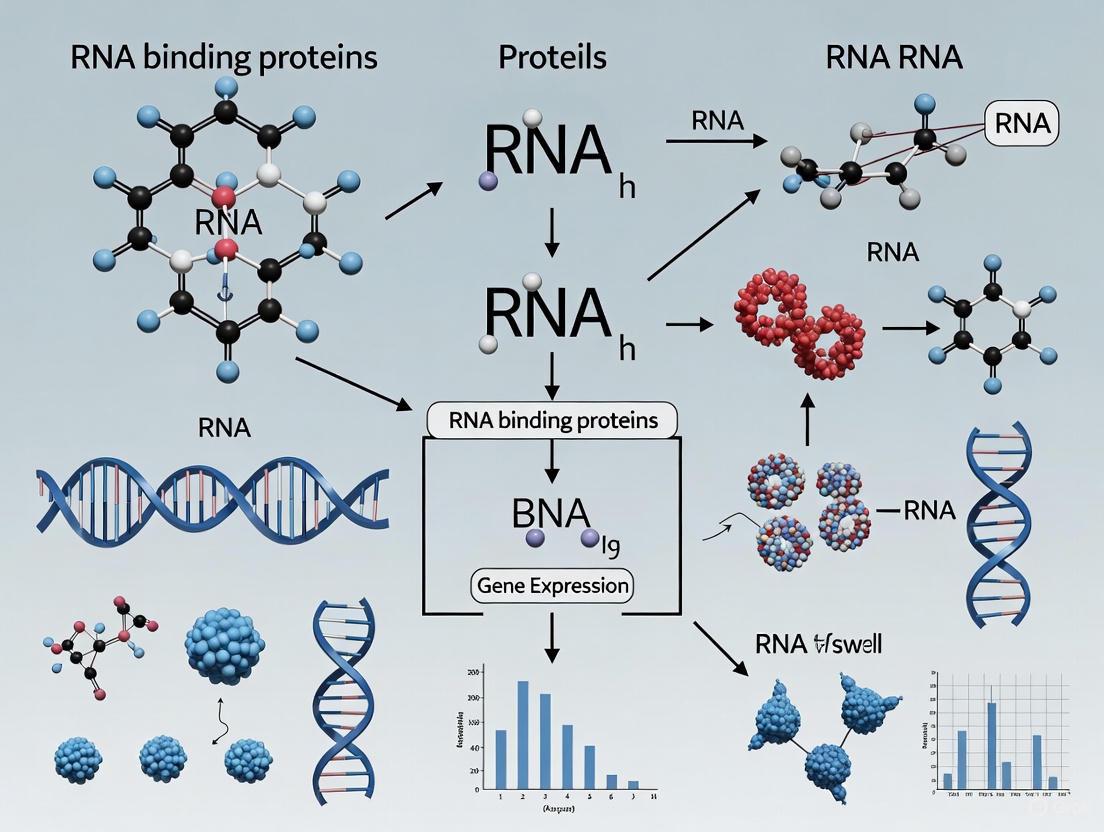

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical roles RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) play in post-transcriptional gene regulation, a rapidly advancing field with profound implications for understanding disease and developing novel therapeutics. We first explore the foundational biology of RBPs, detailing their diverse structural domains and mechanisms of action across the RNA life cycle. The discussion then progresses to methodological innovations, highlighting high-throughput screening techniques and computational tools that are accelerating RBP research and drug discovery. A dedicated section addresses the troubleshooting of challenges associated with targeting RBPs, focusing on their dysregulation in human diseases like cancer and neurodegeneration. Finally, we present a comparative analysis of RBP functions across model organisms and their validation as therapeutic targets, synthesizing key findings to outline future directions for biomedical and clinical research aimed at harnessing the regulatory power of RBPs.

The RBP Toolkit: Domains, Mechanisms, and Ubiquitous Roles in RNA Metabolism

RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) are pivotal actors in the post-transcriptional control of gene expression. Traditionally defined as proteins that bind single or double-stranded RNA to form ribonucleoprotein complexes (RNPs), RBPs are integral to virtually every aspect of RNA metabolism, including splicing, polyadenylation, mRNA stability, localization, and translation [1]. The conventional view of RBPs as proteins containing canonical RNA-binding domains (RBDs) has been radically transformed by proteome-wide studies, which have more than tripled the number of proteins implicated in RNA binding [2]. This expansion reveals an unexpected diversity of RBPs that includes metabolic enzymes, membrane proteins, and many other "well-known" proteins not previously associated with RNA binding, suggesting the existence of previously unidentified modes of RNA binding and new biological functions for protein-RNA interactions [3] [2]. This whitepaper examines the defining characteristics of RBPs, from their core structural complexes to their roles in vast regulatory networks, with particular emphasis on implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Defining Features and Structural Motifs of RBPs

Classical RNA-Binding Domains

RBPs recognize their RNA targets through specialized structural motifs that provide specificity and affinity. The most prevalent of these is the RNA recognition motif (RRM), a domain of 75-85 amino acids that forms a four-stranded β-sheet flanked by two α-helices [1]. Typically, the β-sheet surface interacts with 2-3 nucleotides, with specificity achieved through combinations of multiple RRMs and inter-domain linkers [1]. Another common motif is the double-stranded RNA-binding domain (dsRBD), a 70-75 amino acid domain that recognizes the sugar-phosphate backbone of RNA duplexes without sequence-specific contacts, playing critical roles in RNA interference, editing, and localization [1]. Additional important domains include zinc fingers and KH domains, which provide diverse recognition capabilities across the RBP repertoire [4].

Unconventional RNA-Binding Regions

Recent experimental approaches, particularly RNA interactome capture (RIC), have identified hundreds of unconventional RBPs that lack canonical RBDs [2]. These novel RBPs utilize various unexpected regions for RNA binding, including:

- Intrinsically disordered regions that may undergo folding upon RNA binding

- Protein-protein interaction interfaces that dual-function in RNA binding

- Enzymatic cores of metabolic enzymes and other catalytic proteins

- DNA-binding domains that exhibit promiscuous RNA binding activity [2]

These unconventional RBPs are conserved from yeast to humans and respond to environmental and physiological cues, suggesting RNA control of protein function may occur more commonly than previously anticipated [2].

Table 1: Major RNA-Binding Domain Classes and Their Characteristics

| Domain Type | Size | Structural Features | Recognition Properties | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRM | 75-85 amino acids | Four-stranded β-sheet with two α-helices | Binds 2-3 nucleotides; specificity from domain combinations | mRNA processing, splicing, stability, translation regulation |

| dsRBD | 70-75 amino acids | αβββα fold | Recognizes RNA duplex structure; minimal sequence specificity | RNA interference, editing, localization |

| Zinc Finger | Variable | Coordination by zinc ions | Diverse recognition capabilities | Various post-transcriptional regulations |

| KH Domain | ~70 amino acids | β-sheet packed against two α-helices | Recognizes single-stranded RNA | Splicing, translation regulation |

| Rotundic Acid | Rotundic Acid, CAS:20137-37-5, MF:C30H48O5, MW:488.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals | |

| N-Methyl-1-(piperidin-4-YL)methanamine | N-Methyl-1-(piperidin-4-YL)methanamine, CAS:126579-26-8, MF:C7H16N2, MW:128.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The RBPome: Quantitative Landscape and System Properties

Genomic Scale and Diversity

The human genome encodes an extensive repertoire of RBPs. According to the Eukaryotic RBP Database (EuRBPDB), there are 2,961 genes encoding RBPs in humans [1]. However, this number continues to expand with the identification of unconventional RBPs, with recent estimates suggesting the actual RBPome may be substantially larger [2]. This diversity enables eukaryotic cells to utilize RNA exons in various arrangements, giving rise to unique RNPs for each RNA [1]. The dramatic increase in RBP diversity during evolution correlates with the increase in intron number, supporting the hypothesis that RBPs were crucial for the development of complex regulatory networks in higher organisms.

Network Architecture and Hierarchical Organization

Systematic investigation of approximately fifty thousand interactions between RBPs and the UTRs of RBP mRNAs has revealed two fundamental structural features in the RBP regulatory network [5]. RBP clusters are groups of densely interconnected RBPs that co-bind their targets, suggesting tight control of cooperative and competitive behaviors. RBP chains represent hierarchical structures connecting RBP clusters, with evolutionarily ancient RBPs often occupying central positions [5]. Under this model, regulatory signals flow through chains from one cluster to another, implementing elaborate regulatory plans that coordinate different cellular programs. This network architecture suggests that RBP-RBP interactions form a backbone driving post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression [5].

Core Complexes: The Editosome Case Study

A prime example of RBPs functioning in a defined macromolecular complex comes from studies of the U-insertion/deletion editosome in trypanosomal mitochondria. This complex exemplifies how RBPs assemble into functional units with specialized roles in RNA processing [6].

The editosome consists of two major macromolecular constituents:

- RNA Editing Core Complex (RECC): Embedded with enzymes that catalyze the U-insertion/deletion editing cascade through sequential reactions of mRNA cleavage, U-addition or U-removal, and ligation [6].

- RNA Editing Substrate Binding Complex (RESC): A ~23-polypeptide tripartite assembly responsible for recognizing guide RNAs (gRNAs) and pre-mRNA substrates, editing intermediates, and products [6].

This ~40S RNA editing holoenzyme functions as an interface between mRNA editing, polyadenylation, and translation. The RESC complex demonstrates distinct metabolic fates for different RNA types: gRNAs are degraded in an editing-dependent process, while edited mRNAs undergo 3' adenylation/uridylation prior to translation [6]. This case study illustrates how defined RBP complexes execute precise regulatory programs through coordinated action of multiple protein components.

Methodologies for Characterizing RNA-Protein Interactions

Experimental Approaches for Mapping RBP Interactions

Several powerful methods have been developed to characterize protein-RNA interactions, each with distinct strengths and limitations:

RNA Bind-n-Seq (RBNS) is a quantitative high-throughput method that comprehensively characterizes sequence and structural specificity of RBPs [7]. In RBNS, recombinantly expressed and purified RBPs are incubated with a pool of randomized RNAs (typically 40 nt flanked by primers) at multiple protein concentrations (from low nanomolar to low micromolar) [7]. The RBP is captured via a streptavidin binding peptide tag, and bound RNA is reverse-transcribed into cDNA for deep sequencing. RBNS offers several advantages:

- Identifies both canonical and near-optimal binding motifs

- Calculates dissociation constants that correlate with surface plasmon resonance measurements

- Assesses effects of RNA secondary structure on binding

- Complements crosslinking-based methods by identifying high-confidence splicing-associated binding sites [7]

Cross-linking and immunoprecipitation (CLIP) methods enable transcriptome-wide mapping of RBP binding sites in vivo [1]. Although powerful, CLIP is laborious and may introduce biases, such as preferential detection of uridine-rich sequences [7]. CLIP does not distinguish binding by a single protein from binding of protein complexes [7].

RNA interactome capture (RIC) has been instrumental in expanding the known RBP repertoire. This method uses UV crosslinking of living cells to covalently link RBPs to their RNA targets, followed by oligo(dT) capture of polyadenylated RNAs and identification of crosslinked proteins by mass spectrometry [2]. RIC revealed hundreds of previously unknown RBPs in both HeLa and HEK293 cells [2].

Computational and Modeling Approaches

RBPreg is a computational pipeline that identifies RBP regulators by integrating single-cell RNA-Seq and RBP binding data [8]. This method scans gene sequences to identify RBP binding motifs, calculates RBP-gene regulatory correlations based on expression correlation, and evaluates RBP activities in specific cell types using AUCell [8]. Applied to pan-cancer single-cell transcriptomes (N = 233,591 cells), RBPreg has revealed that RBP regulators exhibit cancer and cell type specificity, with perturbations of RBP regulatory networks involved in cancer hallmark-related functions [8].

Quantitative thermodynamic modeling approaches have been developed to predict RBP binding landscapes. For the human Pumilio proteins PUM1 and PUM2, researchers used the RNA-MaP platform to directly measure equilibrium binding for thousands of designed RNAs and construct predictive models [9]. These models revealed widespread residue flipping and positional coupling, with quantitative agreement between predicted affinities and in vivo occupancies, suggesting a thermodynamically driven, continuous binding landscape [9].

RBP Functions in RNA Processing and Metabolic Regulation

Post-transcriptional RNA Processing

RBPs govern multiple steps of RNA metabolism, creating complex regulatory networks that fine-tune gene expression:

Alternative Splicing: RBPs such as NOVA1 and SR proteins regulate the alternative splicing of heterogeneous nuclear RNA (hnRNA) by recognizing specific sequences (e.g., YCAY for NOVA1) and recruiting splicesomal components [1]. RBPs bind to cis-acting RNA elements including exonic splicing enhancers (ESEs), exonic splicing silencers (ESSs), intronic splicing enhancers (ISEs), and intronic splicing silencers (ISSs) to promote or repress exon inclusion [1].

RNA Editing: The ADAR protein family catalyzes the conversion of adenosine to inosine in mRNA transcripts, effectively changing the RNA sequence from that encoded by the genome and expanding the diversity of gene products [1]. While most editing occurs in non-coding regions, protein-encoding RNAs like the glutamate receptor mRNA can be edited, resulting in functionally altered proteins [1].

Polyadenylation: RBPs including CPSF and poly(A)-binding protein recognize the AAUAAA sequence and recruit poly(A) polymerase, which adds ~200 adenylate residues to the 3' end of mRNAs, influencing nuclear transport, translation efficiency, and stability [1].

mRNA Localization and Translation: RBPs such as ZBP1 bind to β-actin mRNA at the site of transcription, localize it to specific cellular regions (e.g., lamella in asymmetric cells), and repress translation until the mRNA reaches its destination [1]. This provides a mechanism for spatially regulated protein production that is particularly important during development [1].

Emerging Roles in Riboregulation of Protein Function

The discovery of unconventional RBPs suggests a new paradigm of riboregulation - where RNA binding controls protein function rather than proteins simply regulating RNA [3] [2]. Metabolic enzymes, transcription factors, and signaling proteins can be allosterically regulated by RNA binding, potentially creating feedback loops that connect cellular metabolism with gene expression [3]. This riboregulation represents an underexplored layer of cellular regulation with broad implications for understanding cellular physiology and disease mechanisms.

RBPs in Disease and Therapeutic Development

Cancer-Specific RBP Regulatory Networks

Pan-cancer analyses at single-cell resolution have revealed that RBP regulators exhibit cancer and cell type specificity, with perturbations of RBP regulatory networks involved in cancer hallmark-related functions [8]. HNRNPK has been identified as an oncogenic RBP highly expressed in tumors and associated with poor prognosis [8]. Functional assays demonstrate that HNRNPK promotes cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in vitro and in vivo through direct binding to MYC and perturbation of MYC target pathways [8]. This HNRNPK-MYC signaling pathway represents a promising therapeutic target in lung cancer and potentially other malignancies.

Table 2: Key Cancer-Associated RBPs and Their Functions

| RBP | Cancer Types | Mechanism | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| HNRNPK | Lung, Colorectal, Ovarian | Binds MYC, perturbs MYC targets | Promotes proliferation, migration, invasion |

| PUM2 | Ovarian | Not fully characterized | Associated with cisplatin resistance |

| SERBP1 | Glioblastoma | Bridges cancer metabolism and epigenetic regulation | Oncogenic function |

| FXR1 | Multiple | Drives cMYC translation via eIF4F recruitment | Promotes tumorigenesis |

| ELAVL1 | Lung | Regulates mRNA stability of oncogenes | Critical role in lung cancer progression |

| HNRNPDL | T cells (Lung cancer) | Regulates pre-T cell receptor signaling | Affects T cell differentiation and migration |

Neurodegenerative and Other Diseases

Dysregulation of RBPs contributes to various pathologies beyond cancer. In myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1), expanded CUG repeats in the 3' UTR of DMPK mRNAs sequester MBNL proteins, while simultaneously stabilizing CELF1 proteins through hyperphosphorylation [7]. This imbalance disrupts the normal antagonistic relationship between MBNL and CELF proteins that sharpens developmental splicing transitions, leading to mis-splicing events and disease pathology [7]. Similarly, RBP dysfunction has been implicated in other neurological disorders, metabolic diseases, and genetic instability syndromes [4].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RBP Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant SBP-tagged RBPs | Protein | In vitro binding studies | RBNS, affinity measurements, structural studies |

| Randomized RNA pools (λ=40 nt) | Nucleic Acid | Target for binding assays | RBNS, SELEX, RNAcompete |

| CLIP-grade antibodies | Antibody | Immunoprecipitation of RBPs | CLIP-seq, PAR-CLIP, HITS-CLIP |

| Single-cell RNA-Seq kits | Assay Kit | Single-cell transcriptomics | RBPreg analysis, cell type-specific regulation |

| RNA-MaP platform | Platform | Equilibrium binding measurements | Thermodynamic modeling, Kd determinations |

| RBPreg webserver | Computational Tool | Identification of RBP regulators | Cancer RBP network analysis, biomarker discovery |

| MEME Suite | Software | Motif discovery and analysis | De novo RBP motif identification |

The definition of RNA-binding proteins has expanded dramatically from proteins with canonical RNA-binding domains to include a diverse array of unconventional RBPs with unexpected RNA-binding activities. This redefinition has transformed our understanding of the RBP-RNA regulatory network, revealing it as a complex, hierarchical system with crucial roles in cellular homeostasis and disease. Future research will likely focus on several key areas: (1) elucidating the structural basis of RNA recognition by unconventional RBPs; (2) understanding how riboregulation controls protein function; (3) developing quantitative models that predict RBP binding and function across cellular contexts; and (4) leveraging this knowledge for therapeutic intervention in cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and other disorders. As methods for characterizing RBPs continue to advance, so too will our appreciation of their fundamental importance in gene regulation and human health.

RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) are critical regulators of gene expression, functioning at nearly every stage of the RNA life cycle—from transcription and splicing to transport, localization, stability, and translation [1] [10]. They achieve this remarkable functional diversity through specialized modular components known as RNA-binding domains (RBDs). These domains allow RBPs to recognize and interact with specific RNA sequences, structural motifs, or chemical modifications [11] [12]. It is estimated that humans encode over 1,500 RBPs, representing approximately 7.5% of protein-coding genes, highlighting their fundamental importance to cellular function [11] [12]. Dysregulation of these proteins is implicated in a wide array of diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and autoimmune conditions, making them compelling targets for therapeutic intervention [13] [10]. This guide provides a detailed overview of the most prevalent and well-characterized RNA-binding domains, focusing on their structures, mechanisms of RNA recognition, and functional roles within the broader context of RBP-mediated gene regulation.

Core RNA-Binding Domains: Structure and Function

The following table summarizes the key structural and functional characteristics of the major RNA-binding domains.

Table 1: Characteristics of Major RNA-Binding Domains

| Domain | Name | Typical Size | Key Structural Features | RNA Recognition Specificity | Primary Functional Roles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRM | RNA Recognition Motif | 75-90 amino acids [12] | Four-stranded β-sheet stacked against two α-helices (βαββαβ topology) [1] [12] | Primarily single-stranded RNA via the β-sheet surface; typically 2-8 nucleotides per RRM [11] [12] | Splicing, polyadenylation, transport, translation, stability [1] |

| KH | K Homology | ~70 amino acids [12] | Three-stranded β-sheet flanked by three α-helices; Type I (βααββα) and Type II (αββααβ) topologies [12] | Single-stranded RNA/DNA; conserved (I/L/V)-I-G-X-X-G-X-X-(I/L/V) motif is functionally critical [12] | Splicing, translation; mutations linked to Fragile X syndrome [12] |

| dsRBM | Double-Stranded RNA-Binding Motif | 70-90 amino acids [1] [12] | αβ domain structure [12] | Sequence-independent recognition of double-stranded RNA backbone; interacts with two minor grooves and one major groove [1] [12] | RNA editing, interference, localization, translational repression [1] |

| Zinc Fingers | - | Varies by type | Stabilized by zinc ions; types include C2H2, CCCH, and CCHC, often in tandem repeats [12] | Diverse; can recognize DNA and RNA via hydrogen bonding and structural recognition [12] | Transcription, mRNA degradation (e.g., via AU-rich elements) [12] |

RNA Recognition Motif (RRM)

The RRM, also known as the RNA-binding domain (RBD) or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) motif, is the most abundant and well-studied RNA-binding domain [12]. Found in 0.5%–1% of all human genes, it participates in nearly all post-transcriptional processes [11] [12]. The canonical RRM fold consists of 80-90 amino acids arranged in a βαββαβ topology, forming a four-stranded antiparallel β-sheet packed against two α-helices [1] [12]. The β-sheet surface serves as the primary platform for binding single-stranded RNA, typically recognizing 2-8 nucleotides [11] [12]. The affinity and specificity of RNA recognition are often enhanced when RRMs are present in multiple copies within a single polypeptide, allowing the protein to bind longer RNA sequences with high specificity [14] [11]. Proteins containing RRMs, such as heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs), can form multi-domain structures that act as molecular switches in post-transcriptional regulation [12].

K Homology (KH) Domain

The KH domain is another prevalent module that binds single-stranded RNA or DNA and is conserved across eukaryotes, bacteria, and archaea [12]. Its structure of approximately 70 amino acids folds into a three-stranded β-sheet flanked by three α-helices, with two known topological arrangements: Type I (βααββα) and Type II (αββααβ) [12]. A conserved central motif, (I/L/V)-I-G-X-X-G-X-X-(I/L/V), is essential for its function, and mutations in this motif—for example, in the FMR1 gene—can cause Fragile X syndrome, highlighting its critical role in neuronal function [12].

Double-Stranded RNA-Binding Motif (dsRBM)

The dsRBM is a compact domain of 70-90 amino acids that specifically recognizes double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) in a sequence-independent manner [1] [12]. Unlike the RRM and KH domains, the dsRBM does not interact with nucleotide bases. Instead, it binds to the sugar-phosphate backbone of the RNA duplex, making contacts across two adjacent minor grooves and one major groove [1] [12]. This mode of recognition allows a single dsRBM to interact with a wide variety of dsRNA sequences. Proteins like ADAR1, which is involved in RNA editing, integrate dsRBDs to target dsRNA substrates for modification and to maintain immune homeostasis [12].

Zinc Finger Domains

Initially identified in DNA-binding proteins, zinc finger domains also play significant roles in RNA binding [12]. These domains are stabilized by zinc ions and come in several types, including C2H2, CCCH, and CCHC, often present as tandem repeats [12]. The transcription factor TFIIIA, for instance, contains nine zinc fingers that can interact with both DNA and RNA [12]. CCCH-type zinc finger proteins, such as Tis11d, are known to regulate mRNA degradation by binding to AU-rich elements (AREs) in the 3' untranslated regions of target transcripts [12].

Experimental Methods for Studying RNA-Protein Interactions

Understanding the specific interactions between RBPs and their RNA targets is fundamental to deciphering their regulatory roles. The following diagram illustrates a common high-throughput workflow for identifying RBP binding sites.

Figure 1: CLIP-seq Workflow for Mapping RBP-RNA Interactions

Several key methodologies enable the identification and characterization of RNA-protein interactions:

RNA Immunoprecipitation (RIP): This method uses a specific antibody to enrich a target RBP and its associated RNAs from a cell lysate. After purification, the bound RNAs can be identified using quantitative PCR (qPCR) or high-throughput sequencing (RIP-seq) [12]. This approach is useful for studying endogenous RNA-protein complexes.

Crosslinking and Immunoprecipitation (CLIP): CLIP builds upon RIP by incorporating an in vivo UV crosslinking step that covalently links RNAs to proteins that are in direct contact. This step reduces false positives by eliminating transient interactions. Subsequent immunoprecipitation and sequencing (e.g., HITS-CLIP) allow for the precise, genome-wide mapping of protein-RNA binding sites [12] [15]. As shown in Figure 1, the core steps involve crosslinking in live cells, cell lysis, immunoprecipitation of the protein-RNA complex, and sequencing of the bound RNA.

RNA Pull-Down Assay: This is an in vitro technique where a labeled (e.g., biotinylated) RNA probe is used as bait to capture interacting proteins from a cell lysate. The associated proteins are then separated and identified by Western blot or mass spectrometry [12].

Biophysical Binding Assays: Techniques such as Fluorescence Polarization (FP) and Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) are widely used to screen for small molecules that disrupt RNA-protein interactions and to quantify binding affinity and kinetics in vitro [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table lists essential reagents and methodologies utilized in the study of RBPs and their domains.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Methods for RBP Studies

| Reagent / Method | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| CLIP-seq [12] [15] | Genome-wide mapping of in vivo RBP binding sites | Utilizes UV crosslinking for high-resolution; variants include HITS-CLIP, iCLIP. |

| Fluorescence Polarization (FP) [13] | In vitro screening for RBP-RNA interaction inhibitors | Measures change in polarized emission when a small molecule disrupts a fluorescent RNA-protein complex. |

| RIP-seq [15] | Transcriptome-wide identification of RNAs bound by a specific RBP | Does not always use crosslinking; can be performed under different buffer conditions (e.g., G4-stabilizing) [15]. |

| Antibodies (for RIP/CLIP) [12] | Immunoprecipitation of specific RBPs or epitope tags (e.g., His₆) [15] | Critical for specificity; quality directly impacts signal-to-noise ratio. |

| Recombinant His-Tagged RBP Domains [15] | In vitro binding studies and structural biology | Allows purification and study of isolated domains (e.g., C-terminal FUS). |

| Cat-ELCCA [13] | High-throughput screening for RBP inhibitors | Uses click chemistry and enzyme-catalyzed signal amplification; robust and sensitive. |

| X-ray Crystallography & NMR [14] [11] | Determining atomic-level 3D structures of RBDs and RBD-RNA complexes | Provides mechanistic insights into RNA recognition specificity. |

| Chlormidazole hydrochloride | Chlormidazole hydrochloride, CAS:74298-63-8, MF:C15H14Cl2N2, MW:293.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Mandipropamid | Mandipropamid, CAS:374726-62-2, MF:C23H22ClNO4, MW:411.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

RNA Recognition Mechanisms: Specificity and Collaboration

RBPs achieve precise target recognition through diverse molecular strategies, as illustrated in the following diagram of specific and non-specific binding mechanisms.

Figure 2: Mechanisms of RNA Recognition by RBPs

Sequence-Specific and Non-Sequence-Specific Recognition

RNA recognition by RBPs can be broadly categorized into sequence-specific and non-sequence-specific mechanisms, which are not mutually exclusive and can be combined.

Sequence-Specific Recognition: This is often achieved by combining multiple modular domains, such as RRMs or KH domains, to create an extended binding surface that recognizes a longer, specific RNA sequence [14]. A classic example is the Pentatricopeptide Repeat (PPR) protein family, where each repeat recognizes a single RNA nucleotide through a combinatorial amino acid code, and a tandem array of repeats binds a specific single-stranded RNA sequence with high affinity [14].

Non-Sequence-Specific Recognition: Many RBPs recognize target RNAs in a sequence-independent manner by associating with marker groups at the 5' or 3' ends of RNAs or with specific RNA secondary structures [14]. For instance, the innate immune effector IFIT5 contains a deep positively charged pocket that specifically recognizes the 5' triphosphate group of viral RNAs, allowing it to distinguish non-self RNA from host RNA that possesses a different 5' cap structure [14]. Similarly, proteins like RIG-I and MDA5 recognize double-stranded RNA viral signatures primarily through contacts with the RNA's sugar-phosphate backbone and 2'-hydroxyl groups, paying little attention to the underlying base sequence [14].

The Role of RNA Structure in Protein Recognition

RNA secondary and tertiary structures are pivotal regulators of protein interactions [15]. A prominent example is the G-quadruplex (G4), a stable four-stranded structure formed by G-rich sequences. Recent research has shown that the RNA-binding protein FUS, implicated in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and cancer, has a high affinity for RNA G4 structures through its RGG-rich domains [15]. Transcriptome-wide studies using modified RIP-seq under G4-stabilizing conditions have demonstrated that G4 structures directly modulate FUS binding to hundreds of target RNAs, illustrating how RNA structure can be a primary determinant of recognition, sometimes overriding the influence of sequence alone [15].

The architectural diversity of RNA-binding domains—including the RRM, KH, dsRBM, and zinc fingers—provides the structural foundation for the vast functional repertoire of RBPs. These domains enable precise recognition of RNA sequences, structures, and chemical modifications, allowing RBPs to orchestrate the complex post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression. Continued advancements in structural biology (e.g., X-ray crystallography, NMR) and the development of sophisticated interaction mapping techniques (e.g., CLIP-seq) are deepening our understanding of these mechanisms. As research progresses, the insights gained into the structure and function of RBDs are paving the way for novel therapeutic strategies that target RNA-protein interactions in diseases such as cancer and neurodegeneration, marking a promising frontier in drug discovery.

The precise regulation of gene expression is a fundamental process in biology, orchestrated by a complex interplay of specific molecular interactions. At the heart of cellular machinery such as RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) lie non-covalent forces—hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, and stacking interactions—that collectively enable the exquisite specificity required for gene regulation. These interactions facilitate the selective binding of RBPs to their RNA targets, guiding essential processes including RNA modification, splicing, polyadenylation, localization, translation, and decay [16]. The balance and cooperation between these forces determine not only binding affinity and specificity but also the dynamic assembly of macromolecular complexes and biomolecular condensates that underlie transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation. Understanding the precise contributions of these interactions provides crucial insights into the molecular mechanisms of gene regulation and offers novel avenues for therapeutic intervention in diseases ranging from cancer to neurodegenerative disorders.

Fundamental Forces in Molecular Recognition

Hydrogen Bonding

Hydrogen bonds (HBs) represent one of the most directional and specific non-covalent interactions in biological systems. These interactions occur between a hydrogen atom bonded to an electronegative donor (such as oxygen or nitrogen) and an electronegative acceptor atom. In the context of RNA-protein interactions, HBs provide precise molecular recognition through complementary pairing patterns that discriminate between potential binding partners. Recent investigations into the fusion enthalpies of molecular systems have revealed that hydrogen bonding significantly influences thermodynamic properties, with studies enabling the quantitative division of fusion enthalpy into van der Waals and specific interaction contributions [17]. The strength of hydrogen bonding changes during phase transitions can be evaluated using the Badger-Bauer rule, which correlates spectral shifts with interaction energy [17]. For alcohols, phenols, carboxylic acids, and water, these approaches have demonstrated consistent agreement in quantifying hydrogen bonding effects, with estimates typically within 1.1 kJ mol−1 of independently calculated values [17].

Van der Waals Forces

Van der Waals forces encompass weak, non-directional attractive interactions between temporary or permanent dipoles that play a crucial role in molecular packing and complementarity. These forces include London dispersion forces, dipole-dipole interactions, and dipole-induced dipole interactions. Though individually weak, their collective contribution becomes significant in macromolecular interfaces with extensive surface area contact. In molecular cocrystals, van der Waals interactions contribute substantially to lattice stabilization, particularly through stacking and T-type interactions that optimize intermolecular dispersion [18]. The relationship between enthalpy-to-volume ratio and molecular sphericity parameters has enabled researchers to quantitatively separate van der Waals contributions from specific interaction components in fusion enthalpies [17]. This approach has proven particularly valuable for understanding how non-directional forces contribute to the overall stability of molecular complexes.

Stacking Interactions

Stacking interactions involve the attractive contact between aromatic rings or between aromatic and aliphatic systems, operating through a combination of van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions, and hydrophobic effects. These interactions can manifest in several configurations: offset face-to-face (most energetically favorable), edge-to-face (T-shaped), and eclipsed face-to-face (generally unfavorable due to π electron cloud repulsion) [18]. In biological systems, stacking interactions are particularly important for nucleic acid base pairing, protein-carbohydrate recognition, and RBP-RNA complexes. A comprehensive analysis of cocrystals revealed that stacking and T-type interactions are equally important as hydrogen bonds in molecular cocrystals, with over 50% of molecular contacts involving these dispersion-dominated interactions [18]. CH-π stacking interactions, which occur between carbohydrate CH groups and aromatic protein residues, have emerged as critical drivers of protein-carbohydrate recognition, offering orientational flexibility that complements the directionality of hydrogen bonds [19].

Table 1: Quantitative Contributions of Non-Covalent Interactions to Cocrystal Stability

| Interaction Type | Frequency in Cocrystal Dimers | Relative Contribution to Stabilization | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strong Hydrogen Bonds | 20% | High | Directional, specific, energy range 4-40 kJ/mol |

| Stacking/T-type Interactions | >50% | High | Optimize intermolecular dispersion, multiple configurations |

| Halogen Bonds | Variable | Moderate to High | Directional, specific to halogen atoms |

| Weak Hydrogen Bonds | Variable | Low to Moderate | Less directional, cumulative effect |

Table 2: Energetic Contributions to Fusion Enthalpy

| Molecular System | Total Fusion Enthalpy (kJ mol−1) | Van der Waals Contribution | Hydrogen Bonding Contribution | Experimental Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohols | Variable | Derived from volume-sphericity relationship | Calculated via Badger-Bauer rule | Calorimetric, volumetric, spectroscopic |

| Phenols | Variable | Derived from volume-sphericity relationship | Calculated via Badger-Bauer rule | Calorimetric, volumetric, spectroscopic |

| Carboxylic Acids | Variable | Derived from volume-sphericity relationship | Calculated via Badger-Bauer rule | Calorimetric, volumetric, spectroscopic |

| Water | Variable | Derived from volume-sphericity relationship | Calculated via Badger-Bauer rule | Calorimetric, volumetric, spectroscopic |

Experimental Methodologies for Studying Molecular Interactions

Spectroscopic, Calorimetric, and Volumetric Approaches

The quantitative dissection of interaction contributions requires sophisticated methodological approaches. Recent work has developed integrated strategies combining spectroscopic, calorimetric, and volumetric data to analyze the balance between hydrogen bonding and van der Waals forces in fusion enthalpies [17]. The experimental protocol involves:

- Calorimetric Measurements: Determining fusion enthalpies using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) to obtain total thermal energy required for phase transition.

- Volumetric Analysis: Measuring volume changes upon melting to establish correlation with enthalpy changes and molecular sphericity parameters.

- Spectroscopic Assessment: Applying the Badger-Bauer rule to infrared or Raman spectral shifts to quantify hydrogen bonding strength changes during melting.

- Data Integration: Combining these datasets to separate van der Waals and specific interaction contributions through mathematical relationships between enthalpy-to-volume ratios and molecular parameters.

This multifaceted approach has been successfully applied to associated molecular substances including alcohols, phenols, carboxylic acids, and water, providing unprecedented insight into the thermodynamic balance of molecular interactions [17].

Structural Biology and Database Analysis

Comprehensive analysis of molecular interactions benefits greatly from structural databases and statistical approaches:

- Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) Mining: Systematic analysis of 1:1 two-component cocrystals in the CSD reveals prevalence and geometry of different interaction types [18]. The dataset of 3,082 structures with 1:1 stoichiometry and Z' = 1 enables robust statistical analysis.

- Interaction Energy Calculations: Computational evaluation of dimer interaction energies in cocrystals quantifies relative contributions of different interaction types to overall lattice stability.

- Geometric Analysis: Assessment of interaction geometries (distances, angles) provides insight into preferred configurations and their energetic optimizations.

This methodology revealed that only 20% of cocrystal dimers are stabilized solely by strong hydrogen bonds, while over 50% involve significant stacking and T-type interactions [18].

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Molecular Interaction Analysis

Computational Prediction of RNA-Protein Interactions

Advanced computational methods have emerged to predict RNA-protein interactions by leveraging deep learning architectures:

PaRPI Framework: This method predicts RNA-protein binding sites through bidirectional RBP-RNA selection, integrating experimental data from different protocols and batches [20]. The framework includes:

- Protein sequence encoding using ESM-2 pre-trained language model

- RNA representation combining k-mer encoding with BERT modeling

- Secondary structure feature extraction using icSHAPE and RNAplfold

- Graph construction integrating sequence and structural information

- Interaction modules combining GraphConv and Transformer architectures

Training and Validation: PaRPI was trained on 261 RBP datasets from eCLIP and CLIP-seq experiments across multiple cell lines (K562, HepG2, HEK293, HEK293T, HeLa, H9) [20]. The model demonstrates exceptional performance in accurately identifying binding sites, surpassing state-of-the-art models and showing robust generalization to predict interactions with previously unseen RNA and protein receptors.

Cross-Protocol Integration: Unlike traditional methods tailored to specific RBPs and experimental conditions, PaRPI groups datasets by cell lines, enabling development of unified computational models that capture both shared and distinct interaction patterns across different proteins [20].

Integration with RNA-Binding Protein Research

The Expanding RBPome

RNA-binding proteins represent a rapidly expanding class of regulatory proteins, with the number of recognized RBPs in mammalian cells more than tripling in recent years to include many "well-known" proteins such as metabolic enzymes and membrane proteins [3]. This expansion has sparked debate about the biological relevance of their RNA binding, yet growing evidence suggests these interactions represent a fundamental layer of gene regulation. The molecular forces governing RBP-RNA recognition—hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, and stacking interactions—provide the physical basis for this regulatory network, with specificity emerging from the precise combination and spatial arrangement of these interactions.

Small Biomolecule Modulation of RBPs

Small biomolecules (SBMs)—including sugars, nucleotides, metabolites such as S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) and NAD(P)H, and drugs—can directly bind RBPs and modulate their structure, localization, and RNA-binding activity [16]. These context-dependent and concentration-dependent interactions link RBP regulation to cellular metabolism, creating a dynamic interface between metabolic state and gene expression. The molecular interactions between SBMs and RBPs employ the same fundamental forces—hydrogen bonding, van der Waals contacts, and stacking—that govern RNA-protein recognition, suggesting competitive and allosteric mechanisms for regulatory control.

Table 3: Small Biomolecules that Modulate RBP Function

| Small Biomolecule | RBP Targets | Regulatory Mechanism | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) | m6A methyltransferases | Cofactor binding | RNA modification patterning |

| NAD(P)H | Various metabolic RBPs | Redox-sensitive binding | Linking metabolic state to RNA regulation |

| Nucleotides | Multiple RBPs | Competitive binding | Altering RNA-binding affinity |

| Sugars | Glycolytic enzyme RBPs | Allosteric regulation | Metabolic pathway coordination |

Technological Advances in RBP Research

Recent technological innovations are dramatically enhancing our ability to study RNA-protein interactions and the molecular forces that govern them:

SCOPE Tool: A molecular tool that incorporates a guide RNA and a special archaea-derived amino acid (AbK) that forms strong, enduring bonds with nearby proteins upon UV light exposure [21]. This system enables precise identification of proteins bound to specific genomic locations with high sensitivity, detecting weakly and transiently bound proteins that traditional methods miss.

RNAproDB: A webserver and interactive database for analyzing protein-RNA interactions, freely available to researchers [22]. This resource integrates structural data on protein-nucleic acid binding, enabling systematic analysis of molecular recognition principles.

Interpretable Graph Representation Learning: Models like IRGL-RRI use graph representation learning with masking strategies and regularization to enhance RNA feature extraction, combining Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KAN) and multi-scale fusion to resolve complex dynamic interaction mechanisms [23]. This approach improves both prediction accuracy and model interpretability for plant RNA-RNA interactions.

Diagram 2: Molecular Forces in RBP Function & Applications

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Studying Molecular Interactions

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCOPE Tool [21] | Molecular Biology Tool | Precise identification of DNA-bound proteins | Capturing weakly/transiently bound proteins at specific genomic loci |

| PaRPI [20] | Computational Framework | Prediction of RNA-protein binding sites | Bidirectional RBP-RNA selection modeling across cell lines |

| RNAproDB [22] | Database/Webserver | Analysis of protein-RNA interactions | Structural analysis of molecular recognition principles |

| Cambridge Structural Database [18] | Structural Database | Repository of small molecule crystal structures | Statistical analysis of interaction frequencies and geometries |

| ESM-2 [20] | Protein Language Model | Protein sequence representation | Encoding evolutionary and contextual signals from protein sequences |

| icSHAPE & RNAplfold [20] | RNA Structure Tools | RNA secondary structure prediction | Extracting structural features for binding preference analysis |

| IRGL-RRI [23] | Computational Model | Plant RNA-RNA interaction prediction | Interpretable graph representation learning for interaction discovery |

The specificity of molecular interactions in gene regulation emerges from the sophisticated balance and cooperation between hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, and stacking interactions. Rather than any single interaction type dominating, biological systems exploit the unique advantages of each: the directionality of hydrogen bonds enables precise molecular recognition, the additive nature of van der Waals forces facilitates extensive surface complementarity, and the versatile geometries of stacking interactions allow optimal spatial arrangement. In RNA-binding proteins, this interplay creates a sophisticated recognition system that integrates direct readout of nucleotide sequences with structural and dynamic information encoded in RNA molecules. The expanding toolkit for studying these interactions—from integrated calorimetric-spectroscopic-volumetric approaches to advanced computational predictions and novel molecular tools like SCOPE—promises to unravel the intricate balance of forces that govern gene regulatory networks. As our understanding of these fundamental principles deepens, so too does our ability to manipulate them for therapeutic benefit, diagnostic application, and synthetic biology innovation.

The regulation of the messenger RNA (mRNA) lifecycle represents a critical control point in gene expression, directly influencing cellular physiology, development, and disease pathogenesis. This complex process, encompassing splicing, localization, translation, and decay, is predominantly orchestrated by RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) [24] [10]. These proteins recognize specific sequences or structural motifs in RNA molecules through specialized domains like the RNA Recognition Motif (RRM) and K-homology (KH) domains to direct post-transcriptional fate [24]. A comprehensive understanding of these coordinated mechanisms provides the foundation for developing novel therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating gene expression in human diseases, including cancer and neurodegenerative disorders [25] [10].

mRNA Splicing and Processing

Alternative Splicing Mechanisms

Alternative splicing (AS) dramatically expands proteomic diversity by enabling the production of multiple mRNA isoforms from a single gene. This process is predominantly regulated by RBPs such as Serine/Arginine-Rich (SR) proteins and heterogeneous nuclear Ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs), which bind to pre-mRNA transcripts and modulate splice site selection [10]. Research using deep RNA-Seq data from sepsis patients revealed 220,779 splicing events, of which 2,158 were significantly differentially frequent, with exon skipping (ES) being the predominant subtype [26]. Splicing decisions can introduce premature termination codons (PTCs) via frameshifts, thereby coupling splicing to downstream mRNA decay pathways [26].

Interplay with RNA Editing

RNA editing, particularly adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) deamination catalyzed by ADAR enzymes, represents another layer of post-transcriptional regulation that extensively intersects with splicing [27]. Global analyses have revealed that >95% of A-to-I editing occurs cotranscriptionally in chromatin-associated RNA prior to polyadenylation [27]. This timing enables RNA editing to directly influence splice site selection, with studies identifying approximately 500 editing sites in 3' acceptor sequences that can alter exon inclusion [27]. These functional editing sites often reside within highly conserved exons in genes critical for cellular function, highlighting the physiological importance of this regulatory crosstalk [27].

Table 1: Splicing Event Analysis in Sepsis Patients

| Analysis Category | Control Group | Sepsis Group | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Splicing Events Analyzed | 220,779 | 220,779 | N/A |

| Significantly Differentially Frequent Events | N/A | 2,158 (1%) | Adjusted P < 0.05, |DeltaPsi| > 0.1 |

| Events More Frequent in Sepsis | N/A | 1,014 (47%) | Probability ≥ 0.9 |

| Events Less Frequent in Sepsis | N/A | 1,144 (53%) | Probability ≥ 0.9 |

| Median Percent Spliced In (Psi) | 1.98% | 40.4% | P < 0.0001 |

| Exon Skipping (ES) Frequency | 76.3% of splicing events | 44.7% of splicing events | Significant decrease |

Subcellular mRNA Localization and Transport

RBPs play indispensable roles in directing mRNA molecules to specific subcellular compartments, thereby creating spatial regulation of gene expression. Proteins such as the Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein (FMRP) and Staufen facilitate mRNA transport to precise locations like dendrites and synapses, where localized translation occurs in response to synaptic activity and cellular signals [10]. This spatial control ensures that protein synthesis occurs at sites where the products are required, optimizing cellular function and resource utilization [28].

Emerging research indicates that metabolic adaptations require subcellular reorganization of mRNA translation, with localized translation associated with specific organelles regulating cellular metabolic needs [28]. This compartmentalization provides a unique mechanism for cellular regulation, particularly in polarized cells such as neurons, where dendritic translation supports synaptic plasticity and learning [10].

Translation Regulation

Mechanisms of Translational Control

The initiation, elongation, and termination phases of translation are extensively regulated by RBPs. Proteins such as the Poly(A)-Binding Protein (PABP) and eukaryotic Initiation Factors (eIFs) interact with translation machinery components and regulatory elements within mRNAs to modulate translational efficiency [10]. Recent studies have revealed specialized subcellular machinery that coordinates the crosstalk between metabolism and mRNA translation, allowing cells to rapidly adapt their proteome to changing metabolic states [28].

The regulation of translation termination is particularly crucial for nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD). According to the "faux-UTR model," efficient translation termination depends on interactions between release factors (eRF1 and eRF3) and proteins bound to the 3'-UTR and polyA tail [29]. When a premature termination codon (PTC) is positioned too far from these elements, termination is impaired, allowing the NMD machinery to associate with the stalled ribosome and initiate mRNA degradation [29].

Upstream Open Reading Frames and Regulatory Transcripts

Upstream open reading frames (uORFs) represent a common translational control mechanism, with RBPs modulating their impact on downstream translation. Only some mRNAs with uORFs are targeted by the NMD pathway, while others exhibit resistance potentially due to sequences near the uORF stop codon that recruit factors facilitating efficient termination, such as Pub1 [29].

Long undecoded transcript isoforms (LUTIs) represent another regulatory mechanism where 5'-extended transcripts containing multiple uORFs repress expression of canonical protein-coding isoforms [29]. These LUTIs play crucial roles in meiosis, the unfolded protein response, and metabolic regulation, as demonstrated by the DAL5 LUTI which regulates DAL5 protein-coding mRNA expression in response to environmental nitrogen changes [29].

mRNA Decay Pathways

Nonsense-Mediated mRNA Decay

Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) is a highly conserved surveillance pathway that degrades mRNAs containing premature termination codons (PTCs), thereby preventing the production of truncated proteins [26] [29]. The core NMD pathway, conserved from yeast to humans, involves key proteins UPF1, UPF2, and UPF3 [29]. Research in critically ill patients has demonstrated that the rate of NMD is significantly higher in sepsis and deceased patient groups compared to control and survived groups, suggesting aberrant splicing due to altered physiology in critical illness [26].

Computational pipelines have been developed to predict how splicing events introduce PTCs via frameshifts and subsequently influence NMD rates [26]. These tools have revealed that the predominance of non-exon skipping events is associated with disease and mortality states, highlighting the clinical relevance of NMD regulation [26].

Additional mRNA Decay Mechanisms

Beyond NMD, cells employ several other mRNA decay pathways, including those mediated by AU-rich element-binding proteins (ARE-BPs) that target transcripts for degradation by recognizing specific sequence elements [10]. The degradation of mRNAs can occur through multiple mechanisms, including deadenylation-dependent decay, which is initiated by shortening of the polyA tail, and specialized decay pathways involving decapping enzymes such as DCP2 [29].

Table 2: RNA-Binding Protein Domains and Functions

| Domain Type | Structure Features | Recognized Sequences/Structures | Example RBPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| RRM (RNA Recognition Motif) | ~90 amino acids, β1α1β2β3α2β4 conformation with RNP1/RNP2 sequences | Specific RNA sequences | UBP1, UBP2, RBP40, RBP19 [24] |

| KH (K-homology) | Three α-helices around central antiparallel β-sheet | Four nucleic acid bases in protein groove | Unknown in trypanosomes [24] |

| RGG Box | Low sequence complexity with arginine and glycine repeats | RNA bases via hydrophobic stacking | Unknown in trypanosomes [24] |

| Pumilio/PUF | Multiple tandem repeats of 35-39 amino acids | Specific RNA bases | PUF6 [24] |

| PAZ | OB-like folding (oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide binding) | 3'-ends of single-stranded RNAs | Dicer, Argonaute [24] |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Transcriptome-Wide Mapping Techniques

Next-generation sequencing technologies have revolutionized the study of RNA processing by enabling transcriptome-wide analyses of various RNA modifications and processing events [30]. Specialized methods include MeRIP-seq and m6A-seq for mapping methylation sites, Pseudo-seq and Ψ-seq for identifying pseudouridylation, and RiboMeth-seq for ribosomal RNA modification analysis [30]. These approaches typically involve specific capture of RNA species containing particular modifications through antibody binding or chemical treatment, followed by high-throughput sequencing [30].

For comprehensive splicing analysis, tools like Whippet process RNA-Seq data to quantify splicing events based on the percent spliced in (Psi) metric, with statistical significance thresholds typically set at probability ≥0.9 and |DeltaPsi| > 0.1 for differential splicing analysis [26]. Differential gene expression is often determined using thresholds of adjusted P < 0.05 and |log2 fold change| > 2 [26].

Subcellular Fractionation and RNA Editing Analysis

To elucidate the timing of RNA processing events during mRNA maturation, researchers employ subcellular fractionation to isolate RNA from chromatin-associated (Ch), nucleoplasmic (Np), and cytoplasmic (Cp) fractions [27]. This approach demonstrated that >95% of A-to-I RNA editing occurs cotranscriptionally in chromatin-associated RNA prior to polyadenylation [27]. The protocol involves:

- Cell Fractionation: Sequential separation of cellular compartments using differential centrifugation and detergent-based methods, with separation quality confirmed by Western blot analysis for compartment-specific markers [27].

- RNA Extraction: Isolation of both polyadenylated and nonpolyadenylated RNA from each fraction to capture nascent transcripts [27].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Construction of sequencing libraries from each fraction, typically in biological triplicates to ensure reproducibility [27].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Read mapping using specialized algorithms that handle single-nucleotide variants effectively, followed by identification of editing sites and comparison across fractions [27].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for mRNA Lifecycle Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Sequencing Kits | MeRIP-seq, m6A-seq, Pseudo-seq, Ψ-seq, PA-m5C-seq, RiboMeth-seq | Mapping specific RNA modifications transcriptome-wide [30] |

| Subcellular Fractionation Kits | Chromatin-associated, Nucleoplasmic, Cytoplasmic fractionation systems | Isolating RNA from distinct subcellular compartments to study processing timing [27] |

| NMD Pathway Components | UPF1, UPF2, UPF3 antibodies; UPF1 knockout/knockdown cells | Investigating nonsense-mediated decay mechanisms and substrates [29] |

| RBP Immunoprecipitation Reagents | Anti-RBP antibodies; CLIP-seq kits (e.g., m6A-CLIP, methylation-iCLIP) | Identifying RBP binding sites and targets [30] [25] |

| Splicing Analysis Tools | Whippet software; RNA-Seq alignment tools | Quantifying splicing events (e.g., exon skipping, retained intron) and calculating Psi values [26] |

| Ribosome Profiling Reagents | 40S ribosome profiling protocols; translation inhibitors | Identifying translation events and efficiency genome-wide [29] |

Visualization of Pathways and Workflows

RBP Regulatory Network in mRNA Lifecycle

Diagram 1: RBP regulation across the mRNA lifecycle. RBPs (yellow) control each stage from splicing to decay.

Nonsense-Mediated Decay Pathway

Diagram 2: NMD pathway distinguishing normal and premature translation termination.

The intricate coordination of splicing, localization, translation, and decay processes throughout the mRNA lifecycle represents a sophisticated regulatory network essential for cellular homeostasis. RNA-binding proteins stand at the center of this network, integrating signals from various pathways to fine-tune gene expression outputs. Disruptions in these processes, whether through mutations in RBPs or dysregulation of decay pathways, contribute significantly to human diseases including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and critical illness [26] [25] [10]. As experimental methodologies continue to advance, particularly in single-cell and spatial transcriptomics, our understanding of these mechanisms will deepen, revealing new therapeutic opportunities for modulating gene expression in disease contexts.

RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) have traditionally been characterized as effectors of mRNA metabolism, governing the fate of protein-coding transcripts from synthesis to decay. However, contemporary research has unveiled a more expansive landscape where RBPs engage in intricate cross-talk with diverse non-coding RNA (ncRNA) species to form sophisticated ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. These complexes represent fundamental regulatory units that control critical cellular processes, and their dysregulation underpins various human pathologies, including cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and genetic disorders [31] [3] [32]. The RBP repertoire itself has dramatically expanded, now encompassing over a thousand proteins in mammalian cells, including many well-known metabolic enzymes and membrane proteins whose RNA-binding activities were previously unrecognized [3]. This whitepaper examines the molecular mechanisms governing RBP interactions with ncRNAs, the assembly and function of RNPs, and the experimental frameworks essential for probing this complex regulatory network, providing a comprehensive resource for researchers and therapeutic developers in the field of gene regulation.

Molecular Mechanisms of RBP-ncRNA Crosstalk

The interaction between RBPs and ncRNAs forms a dynamic regulatory network that fine-tunes gene expression at multiple levels. This crosstalk is particularly consequential in disease contexts such as cancer, where it influences metabolic reprogramming, immunity, drug resistance, metastasis, and ferroptosis [31].

Table 1: Regulatory Mechanisms of RBPs in Collaboration with ncRNAs

| Mechanism | RBP/ncRNA Involved | Molecular Function | Biological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative Splicing | RBFOX2, ESRP2 [25] | Binds pre-mRNA to modulate splice site selection; can be guided by lncRNAs. | Generates protein isoforms with different functions. |

| mRNA Stability | Rox8, LIN28, MSI2, QKI5 [25] | RBP recruits/stabilizes miRNAs (e.g., miR-8) to target sites or directly binds mRNA. | Promotes decay or stabilization of target transcripts (e.g., Yki/YAP, LATS2). |

| Translation Regulation | YTHDF1, MSI2 [25] | Binds mRNA to facilitate or inhibit ribosome recruitment and initiation. | Fine-tunes protein synthesis rates, often in response to stimuli. |

| Phase Separation | FUS, TDP-43 [33] | RBPs with IDRs drive liquid-liquid phase separation with RNAs. | Forms membrane-less organelles (e.g., stress granules, P-bodies). |

| Chromatin Remodeling | lncRNA Evf2 [34] | lncRNA acts as a scaffold, recruiting RBPs and chromatin modifiers to DNA. | Activates or represses transcription, guides enhancer-promoter loops. |

Functional Consequences of RBP-ncRNA Interactions

The collaboration between RBPs and ncRNAs creates a multi-layered regulatory system with several emergent properties:

Scaffolding and Recruitment: Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) often function as modular scaffolds, assembling specific RBP complexes to execute coordinated functions. For instance, the lncRNA Evf2 facilitates a sophisticated system of gene regulation during brain development by guiding enhancers to chromosomal sites and recruiting RBPs, thereby influencing the expression of seizure-related genes and revealing a novel chromosome organizing principle [34]. Similarly, the honeybee lncRNA LOC113219358 interacts with over 100 proteins to modulate detoxification, neuronal signaling, and energy metabolism pathways [35].

Competitive Binding and "Sponging": Circular RNAs (circRNAs) and other ncRNAs can act as competitive endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) by sequestering miRNAs or RBPs, thereby liberating their target mRNAs. A defined circuit involving circCSPP1, which binds to miR-10a to elevate BMP7 expression, promotes dermal papilla cell proliferation in Hu sheep [35]. This ceRNA network logic is a recurring theme in diverse biological contexts, from oncology to reproduction.

Post-Transcriptional Coordination: RBPs and ncRNAs cooperate to control mRNA fate. A conserved mechanism involves the RBP Rox8, which recruits and stabilizes miRNA-8-containing RISC complexes on the 3'UTR of yki mRNA (YAP in mammals), leading to its degradation [25]. This interplay demonstrates how an RBP can enhance the efficacy and specificity of a miRNA.

Architecture and Assembly of Ribonucleoprotein Complexes

RNPs are not simple binary complexes but often exist as stable, higher-order multimers whose assembly is a highly regulated process. Understanding their structure is key to understanding their function and dysfunction in disease.

Principles of RNP Multimerization

Similar to proteins, RNPs can form homomeric or heteromeric oligomers, providing functional advantages such as allosteric control, increased binding strength through multivalency, creation of new active sites at subunit interfaces, and structural stabilization [36]. Multimerization can occur via RNA-RNA, RNA-protein, and/or protein-protein interactions.

Table 2: Examples of Multimeric Ribonucleoprotein Complexes

| RNP Complex | Composition | Function | Multimerization Interface |

|---|---|---|---|

| Box C/D snoRNP | s(no)RNA, L7Ae/15.5K, Nop5, Fibrillarin [36] | 2'-O-ribose methylation of rRNA | Nop5 homodimerization via coiled-coil domain, forming a di-sRNP. |

| Telomerase RNP | Telomerase RNA, TERT, associated proteins [32] | Telomere maintenance | Dynamic assembly; mutations linked to cancer and dyskeratosis congenita. |

| U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP | U4, U6, U5 snRNAs, and multiple proteins [36] | Pre-mRNA splicing | Protein-protein and RNA-RNA interactions between snRNPs. |

| Signal Recognition Particle (SRP) | 7S RNA, SRP proteins [37] | Protein targeting to ER | Heteromeric complex involving multiple RNA-protein contacts. |

A prime example of functional multimerization is the archaeal box C/D sRNP (and its eukaryotic counterpart, the snoRNP), which performs 2'-O-ribose methylation of rRNA. Structural and biochemical studies reveal it functions as a stable dimer. The assembly begins with the L7Ae protein binding to the kink-turn (k-turn) and k-loop structures in the sRNA's C/D and C'/D' motifs. This is followed by the recruitment of Nop5, which homodimerizes through an extensive coiled-coil domain, effectively bridging the two methylation guide modules. The methyltransferase fibrillarin then completes the complex by binding to Nop5. This dimeric architecture allows for coordinated regulation and potentially communication between the two active sites [36].

The Role of Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs)

A paradigm shift in understanding RBP structure has been the recognition of the critical role played by intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs). These regions lack a fixed 3D structure and are enriched within RBPs, often constituting a larger fraction of the sequence than the canonical RNA-binding domains (RBDs) themselves [38].

IDRs contribute to RNA binding and RNP function in several key ways:

- Direct RNA Contact: IDRs, particularly those containing arginine-rich motifs (ARMs) or SR/RG repeats, can directly interact with RNA, sometimes undergoing a disorder-to-order transition upon binding [38].

- Domain Orientation: The disordered linkers between structured RBDs control their relative orientation and spatial flexibility, which is crucial for binding to complex RNA targets [38].

- Phase Separation: IDRs are primary drivers of liquid-liquid phase separation, a process that leads to the formation of membrane-less organelles like stress granules and P-bodies. These compartments represent large, dynamic RNP assemblies that regulate RNA metabolism, translation, and degradation in response to cellular signals [33].

Experimental Toolkit for Studying RNPs and RBP-ncRNA Interactions

Deciphering the complexities of RNP biology requires a multifaceted experimental approach. The following protocols and reagents represent key methodologies in the field.

Key Methodologies and Workflows

RNA Interactome Capture (RIC) is a powerful proteome-wide method for identifying the full complement of RBPs under specific conditions. The updated workflow for plant leaves involves the following steps [37]:

- In Vivo Crosslinking: Cells or tissues are exposed to UV light (254 nm) to covalently crosslink RBPs to their bound RNAs.

- Cell Lysis and Oligo(dT) Capture: The lysate is incubated with oligo(dT) magnetic beads under high-salt conditions to capture polyadenylated RNAs and their crosslinked proteins.

- Stringent Washing: Beads are extensively washed to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- RNase Elution: Proteins are released from the beads by digesting the RNA scaffold.

- Proteomic Analysis: The eluted proteins are identified using mass spectrometry, revealing the RNA-bound proteome.

Mapping RBP Binding Determinants via Mutagenesis: To distinguish the contributions of predicted RBDs and IDRs, systematic truncation mutants can be generated and analyzed using methods like RNA tagging [38].

- Construct Design: Create a series of truncation or point mutations targeting predicted RBDs and IDRs within the RBP of interest.

- In Vivo Binding Assay: Transfer the mutant constructs into a model system (e.g., S. cerevisiae).

- Transcriptome-Wide Binding Profiling: Use techniques like CLIP (Cross-Linking and Immunoprecipitation) or RNA tagging to map the binding sites and affinity of the mutant RBP.

- Data Analysis: Compare the binding patterns of mutants to the wild-type RBP to identify regions essential for affinity and specificity. A key finding from such studies is that many predicted RBDs are not individually essential, while IDRs often play a critical role in determining binding patterns in vivo [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for RNP Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads | Capture polyadenylated RNA and crosslinked RBPs. | Core component of RNA Interactome Capture [37]. |

| UV Crosslinker (254 nm) | Creates covalent bonds between RBPs and RNA at zero-distance. | In vivo crosslinking for RIC and CLIP-based methods [37]. |

| Crosslinking and Immunoprecipitation (CLIP) Kits | Genome-wide mapping of RBP binding sites on RNA. | Identifying the transcriptome-wide targets of an RBP like FUS or QKI [25]. |

| Mass Spectrometry | Identification and quantification of proteins. | Proteomic analysis of proteins eluted in RIC or co-IP experiments [37]. |

| Single-Molecule FISH (smFISH) | Direct visualization and quantification of RNA molecules in fixed cells. | Validating RNA localization and investigating co-localization with RBPs [33]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Knockout Cells | Generate loss-of-function models for genes encoding RBPs or ncRNAs. | Functional validation of RBP-ncRNA interactions (e.g., study Evf2 function) [34]. |

| Moracin C | ||

| 2-keto-L-Gulonic acid | 2-keto-L-Gulonic acid, CAS:526-98-7, MF:C6H10O7, MW:194.14 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualization of RNP Dynamics and Function

The following diagrams illustrate key concepts in RNP assembly and experimental interrogation.

RNP Assembly and ncRNA Interaction Networks

Diagram Title: RNP Assembly and ncRNA Interaction Networks. This diagram illustrates how RNA-binding proteins (RBPs), composed of structured RNA-binding domains (RBDs) and intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs), multimerize and interact with different non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs, circRNAs, miRNAs) to regulate mRNA fate through various mechanisms, including phase separation.

Experimental Workflow for RNA Interactome Capture

Diagram Title: RNA Interactome Capture Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps in the RNA Interactome Capture (RIC) protocol, used for the proteome-wide identification of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) that are bound to polyadenylated RNAs.

Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Perspectives

The fundamental role of RNP complexes and RBP-ncRNA networks in cellular homeostasis makes them critical players in human disease and attractive targets for therapeutic intervention.

Cancer and Targeted Resistance: The interplay between RBPs and ncRNAs can drive oncogenesis and therapy resistance. For example, restoring the tumor-suppressive miR-142-3p overcomes tyrosine-kinase-inhibitor resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) by targeting YES1 and TWF1, which converge on YAP1 phosphorylation and autophagy pathways [35]. This highlights the therapeutic potential of targeting specific nodes within RBP-ncRNA networks.

Neurological Disorders: Mislocalization and aggregation of RBPs like TDP-43 and FUS are hallmarks of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and other motor neuron diseases. These aggregates disrupt RNP complexes, impairing RNA transport and local translation at the synapse, which is critical for neuronal function [33]. Furthermore, mislocalization of the translation regulatory BC200 RNA contributes to synaptic dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease [33].

Rare Genetic Diseases: Mutations in proteins involved in the biogenesis of essential RNPs like the ribosome and telomerase are responsible for a class of rare genetic disorders known as ribosomopathies (e.g., Diamond-Blackfan anemia, Shwachman-Diamond syndrome) and dyskeratosis congenita [32]. Telomerase, itself an RNP, is activated in 80% of cancers, making its biogenesis factors attractive therapeutic targets [32].

The future of therapeutics in this arena lies in precision engineering. For ncRNA-based therapies, this involves iterative design cycles that optimize chemistry, delivery, and rigorous on- and off-target evaluation [35]. The most promising applications will be in disease contexts where coordinated modulation of multiple regulatory nodes by targeting a central RBP or ncRNA provides a strategic advantage.

The world of RBPs and RNPs extends far beyond the regulation of mRNA. It encompasses a vast, dynamic network of interactions between a diverse proteome of RBPs (including many non-canonical players) and a sophisticated transcriptome of ncRNAs. These interactions give rise to complex RNP machines that control virtually every aspect of nucleic acid metabolism and gene expression. The field is moving from discovery to mechanistic elucidation and is beginning to harness engineering principles to translate this knowledge into therapeutic strategies. Understanding the principles of RNP assembly, the functional outcomes of RBP-ncRNA crosstalk, and the methodological approaches to study them is fundamental for researchers and drug developers aiming to target the RNA-protein interface for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes.

From Binding Sites to Therapeutics: Tools and Strategies for RBP Investigation and Targeting

The regulation of gene expression is a complex, multi-layered process where RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) play a central role in directing the fate of cellular RNAs. With the human genome encoding an estimated 2,500 RBPs [39], these proteins regulate every aspect of RNA metabolism, including splicing, polyadenylation, transport, localization, translation, and decay [24] [39]. A significant paradigm shift has emerged in recent years, revealing that many transcription factors and epigenetic regulators also function as RBPs, directly binding RNA to fine-tune transcriptional programs and chromatin states [39]. Understanding the intricate networks of RNA-protein interactions is therefore fundamental to deciphering the molecular basis of gene regulation.

High-throughput techniques have been developed to map these interactions on a global scale. Among the most powerful are Cross-Linking and Immunoprecipitation (CLIP-seq) and its variant, RNA Interaction by Ligation and Sequencing (RIL-seq). These methods enable the systematic identification of RBP binding sites and RNA-RNA interactions at nucleotide resolution, providing unprecedented insights into the post-transcriptional regulatory landscape. This technical guide explores the principles, methodologies, and applications of these techniques, framing them within the broader context of elucidating the functional role of RBPs in health and disease.

Technique Deep Dive: Core Methodologies and Principles

CLIP-seq: Mapping RBP-RNA Interactions

CLIP-seq and its advanced version, HITS-CLIP, provide a robust framework for identifying the transcriptome-wide binding sites of a specific RBP. The core principle involves in vivo crosslinking of proteins to RNA using UV light, which creates covalent bonds between the RBP and its bound RNA molecules without involving protein-protein crosslinks. This is followed by immunoprecipitation of the protein-RNA complexes using an antibody against the RBP of interest. The crosslinked RNAs are then extracted, reverse-transcribed, and sequenced [40].

A key challenge in comparative studies is identifying differential RBP binding under varying conditions. Tools like dCLIP use a hidden Markov model and Viterbi algorithm for this purpose. More recently, DeepRNA-Reg, a deep learning-based algorithm, has demonstrated superior sensitivity and precision in detecting differentially enriched sites from paired HITS-CLIP data. In benchmark tests, DeepRNA-Reg identified over 80% more canonical miRNA seed binding sequences than dCLIP and provided predictions that were more precisely centered on the actual binding sites [40].

RIL-seq and iRIL-seq: Charting RNA Interaction Networks

While CLIP-seq focuses on a single RBP, RIL-seq is designed to profile the global RNA-RNA interactome mediated by RNA chaperones like Hfq or ProQ in bacteria. The standard RIL-seq protocol relies on UV crosslinking, immunoprecipitation of the chaperone protein, and proximity ligation of interacting RNA pairs in vitro to create chimeric RNA fragments for sequencing [41]. These chimeras represent direct RNA-RNA interactions, such as those between small non-coding RNAs (sRNAs) and their target mRNAs.

A significant innovation is intracellular RIL-seq (iRIL-seq), which streamlines the process by performing the RNA ligation step inside living cells. This is achieved by pulse-expressing T4 RNA ligase 1 from an inducible promoter, enabling in vivo proximity ligation of interacting RNA pairs crosslinked to Hfq. After a brief induction period, Hfq-bound ligation products are enriched by co-immunoprecipitation and sequenced [41]. This approach eliminates the need for lengthy in vitro enzymatic steps, reducing artifacts and biases. iRIL-seq generates a high number of "informative" non-rRNA/tRNA chimeras (approximately 8,000 chimeras per million reads) and exhibits strong directionality, with over 90% of sRNAs located at the 3' end of the chimeric fragments [41].

Table 1: Key High-Throughput Techniques for Mapping RNA Interactions

| Technique | Primary Target | Crosslinking | Ligation Step | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLIP-seq/HITS-CLIP | RNA-Protein Interactions | UV in vivo | Not Applicable | Identifies binding sites for a specific RBP at nucleotide resolution. |

| RIL-seq | RNA-RNA Interactions | UV in vivo | In vitro (T4 RNA ligase) | Maps global RNA interaction networks mediated by a specific chaperone. |

| iRIL-seq | RNA-RNA Interactions | UV in vivo | In vivo (T4 RNA ligase) | More streamlined; reduces in vitro artifacts; captures dynamic interactions in live cells. |

Experimental Protocols: From Bench to Sequencing