RNA-seq Differential Gene Expression Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Clinical Applications

This comprehensive guide explores RNA-seq differential gene expression analysis, covering foundational principles, methodological approaches, troubleshooting strategies, and validation techniques.

RNA-seq Differential Gene Expression Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive guide explores RNA-seq differential gene expression analysis, covering foundational principles, methodological approaches, troubleshooting strategies, and validation techniques. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it addresses key applications in disease research, biomarker discovery, and therapeutic development. The content synthesizes current best practices for experimental design, statistical analysis, and interpretation while highlighting emerging technologies like single-cell RNA-seq that are transforming precision medicine and pharmaceutical research.

Understanding RNA-seq DGE Analysis: Core Principles and Biological Significance

Differential Gene Expression (DGE) analysis is a foundational bioinformatics technique for deciphering complex biological mechanisms by comparing gene expression levels between different conditions or treatments [1]. It aims to identify genes that exhibit statistically significant changes in expression, shedding light on key biological pathways and providing valuable insights into normal physiology and disease states [2] [1]. By examining which genes are turned on or off and to what extent, researchers can connect the information in our genome with functional protein expression, uncovering molecular factors underlying biological processes in health and disease [3] [2].

The core outcome of a DGE analysis is a list of differentially expressed genes (DEGs), which are identified by assessing both the magnitude (typically expressed as fold-change) and statistical significance (p-value) of expression differences between groups [2]. These genes collectively define a 'discovery set' that researchers can investigate for known associations with phenotypes of interest, as well as potentially novel associations that may require validation through molecular biology assays like PCR [2].

RNA-seq Technology and Workflow

RNA-seq Basics and Advantages

RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) has become the predominant technique for measuring gene expression in DGE studies, having largely superseded microarray technology due to several key advantages [3] [1]. Unlike hybridization-based approaches like microarrays that may require species-specific probes, RNA-seq can detect transcripts from organisms with previously undetermined genomic sequences, making it fundamentally superior for detecting novel transcripts and alterations [3]. Additional advantages include low background signal, as cDNA sequences can be precisely mapped to genomic regions to remove experimental noise, and better quantifiability across a wide dynamic range of expression levels [3].

RNA-seq investigates the transcriptome—the total cellular content of RNAs including mRNA, rRNA, and tRNA—providing information about which genes are activated or silenced in a cell, their transcription levels, and their activation timing [3]. Crucially, it captures information that would be missed by DNA sequencing alone, including alternative splicing events that produce different transcripts from a single gene sequence, and post-transcriptional modifications such as polyadenylation and 5' capping [3].

Experimental Protocol for RNA-seq

A standardized RNA-seq workflow involves multiple critical steps that must be carefully executed to generate high-quality data for differential expression analysis [3]:

Experiment Planning

Comprehensive planning is essential before commencing wet-lab work. Critical considerations include: determining the appropriate read depth and read length for your experimental goals; selecting between single-end or paired-end sequencing methods; deciding whether to use strand-specific protocols to retain information about which DNA strand was transcribed; ensuring adequate biological and technical replicates; choosing an appropriate reference genome if available; and establishing RNA purification methods [3]. Proper planning at this stage is crucial for generating statistically powerful data that can answer biological questions effectively.

RNA Extraction and Quality Control

The first wet-lab step involves RNA extraction and purification from biological samples. Isolating sufficient, high-quality RNA is critical, as poor sample quality can lead to protocol failure or misleading results [3]. Unlike DNA, RNA degrades rapidly, so samples must be handled carefully throughout isolation and purification. RNA quality and concentration should be determined using UV-visible spectroscopy, with particular attention to avoiding non-uniform degradation that could hinder comparison of transcription levels between genes or cause complete loss of low-level transcripts from the sequenced population [3].

cDNA Library Preparation and Sequencing

The population of RNA is converted into complementary DNA (cDNA) fragments through reverse transcription, creating a cDNA library that can be processed through NGS workflows [3]. The cDNA is fragmented, and platform-specific adapter sequences are added to each end of the fragments. These adapters contain functional elements that permit sequencing, including amplification elements for clonal amplification and primary sequencing priming sites [3]. For strand-specific protocols, amplification involves reverse transcriptase-mediated first strand synthesis followed by DNA polymerase-mediated second strand synthesis. Barcodes may be added to enable multiplexing of multiple samples in a single run [3]. After library quantification and quality checking, the cDNA library is sequenced to the desired depth using the chosen NGS platform.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential research reagents and materials for RNA-seq experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | Preserves RNA integrity post-collection | Prevents degradation by RNases; critical for accurate expression quantification |

| Reverse Transcriptase Enzymes | Converts RNA to complementary DNA (cDNA) | Essential for creating stable cDNA libraries from RNA templates |

| Adapter Oligonucleotides | Platform-specific sequences ligated to cDNA | Enables sequencing and amplification; may include barcodes for multiplexing |

| NGS Sequencing Kits | Provides reagents for sequencing chemistry | Platform-specific (e.g., Illumina, Ion Torrent); includes enzymes, buffers, nucleotides |

| RNA Quality Control Kits | Assesses RNA integrity and quantity | Uses methods like UV-visible spectroscopy or automated electrophoresis |

Differential Gene Expression Analysis Methods

Statistical Framework for DGE Analysis

Statistical methods are crucial for identifying genes with significant expression changes between conditions while controlling for false discoveries. The fundamental challenge in DGE analysis involves distinguishing true biological signals from technical noise and biological variability [4]. Methods must account for characteristics of gene expression data, particularly in single-cell RNA-seq where technical artifacts like dropout events, zero-inflation, and high cell-to-cell variability are prominent [4]. Furthermore, failing to account for pseudoreplication—where cells from the same biological sample are not statistically independent—can substantially inflate false discovery rates [4].

Comparison of DGE Analysis Methods

Table 2: Popular differential gene expression analysis methods and their characteristics

| Method | Underlying Model | Key Features | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| edgeR [4] [2] [1] | Negative binomial generalized linear models | Robust for small replicate numbers; handles common and rare genes effectively | Bulk RNA-seq with limited replicates; quasi-likelihood tests for complex designs |

| DESeq2 [4] [2] [1] | Negative binomial with shrinkage estimators | Improved dispersion estimation for low-count genes; handles batch effects | Larger numbers of replicates; Wald test or likelihood ratio test |

| Limma-voom [2] [1] | Linear modeling with empirical Bayes and precision weights | Transforms count data for linear modeling; combines precision weights with linear models | Limited replicate numbers; both microarray and RNA-seq data |

| MAST [4] | Generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) | Accounts for cellular detection rate; random effects for sample correlation | Single-cell RNA-seq; specifically designed for zero-inflated data |

| Traditional t-test [2] | Normal distribution assumptions | Simple comparison of means between two groups | Preliminary screening; basic two-group comparisons |

Method Selection Workflow

Special Considerations for Single-Cell RNA-seq

Single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) introduces specific challenges for DGE analysis that require specialized methodological approaches. The consensus in recent benchmarking studies indicates that although single-cell data contains distinctive technical noise artifacts, methods originally designed for bulk RNA-seq data often perform favorably compared to methods explicitly designed for scRNA-seq data [4]. Single-cell specific methods have been found to be particularly prone to wrongly labeling highly expressed genes as differentially expressed [4].

To account for within-sample correlations in scRNA-seq data, batch effect correction or aggregation of cell-type-specific expression values within an individual through pseudobulk generation should be applied prior to DGE analysis [4]. Both pseudobulk methods with sum aggregation (such as edgeR, DESeq2, or Limma) and mixed models (such as MAST with random effect setting) have been found to be superior compared to naive methods that do not account for these correlations, such as the popular Wilcoxon rank-sum test [4].

Applications in Biological Research and Drug Development

Differential gene expression analysis serves as a powerful discovery tool across multiple domains of biological research and pharmaceutical development:

In disease research, DGE analysis provides crucial insights into molecular mechanisms underlying various diseases by comparing gene expression profiles between healthy and diseased tissues [1]. This approach enables researchers to identify dysregulated genes and pathways associated with pathogenesis, potentially leading to novel diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets [1].

For drug discovery, identifying differentially expressed genes in response to drug treatments can reveal molecular targets and mechanisms of action [1]. This knowledge aids in both drug discovery and the development of personalized medicine approaches by characterizing how pharmacological interventions alter transcriptional networks at the cellular level.

In developmental biology, DGE analysis enables exploration of gene regulatory networks during embryonic development, tissue differentiation, and organogenesis [1]. This helps uncover key genes and signaling pathways involved in these complex biological processes, providing insights into normal development and developmental disorders.

In environmental studies, comparing gene expression patterns in response to environmental factors provides insights into the impact of pollutants, toxins, and stressors on living organisms [1]. This application is particularly valuable in toxicology and environmental risk assessment.

Differential gene expression analysis represents a cornerstone technique in modern biological research, enabling scientists to identify molecular changes underlying biological processes, disease states, and treatment responses. While the field faces ongoing challenges related to data normalization, batch effects, and robust statistical approaches, continued methodological development and integration of multi-omics data will further enhance the accuracy and biological interpretation of DGE analysis [1]. As RNA-seq technologies continue to evolve and decrease in cost, differential gene expression analysis will remain an essential tool for connecting genomic information with functional outcomes across diverse research applications.

Gene expression profiling serves as a cornerstone in molecular biology and biotechnology, enabling researchers to assess gene activity and gain insights into gene function, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic responses [5]. Among the tools available for transcriptome analysis, Microarray technology and RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) have emerged as two of the most widely used techniques [5]. The choice between these platforms represents a critical decision point in experimental design, with implications for data quality, computational requirements, and biological insights. This application note provides a detailed comparison of these technologies, framed within the context of differential gene expression analysis research, to guide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting the appropriate platform for their specific needs.

Microarray Technology

Microarrays function as high-tech "snapshots" of gene activity through a hybridization-based approach [5]. The technology utilizes a grid of thousands of tiny DNA probes, each designed to bind with a specific RNA (mRNA) from a biological sample. When RNA from the sample hybridizes with these probes, it produces a fluorescence signal whose intensity correlates with the level of gene expression [5]. This method is particularly useful for targeted studies focusing on known genes or well-characterized gene sets, providing an efficient way to assess predefined gene expression across different experimental conditions [5].

RNA-Seq Technology

RNA-Seq represents a cutting-edge next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology that directly sequences RNA fragments after converting them to complementary DNA (cDNA) [5] [6]. This approach provides a "digital readout" of gene expression by mapping sequences back to a reference genome or transcriptome, generating precise counts of RNA abundance [5]. Unlike microarrays, RNA-Seq does not rely on predefined probes, enabling discovery of novel transcripts and alternative splicing events alongside quantitative gene expression measurement [5].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Technical Specifications

Table 1: Key technical differences between RNA-Seq and Microarray technologies

| Feature | RNA-Seq | Microarray |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity & Specificity | Higher sensitivity and specificity; detects low-abundance transcripts and novel genes [5] | Limited sensitivity; can miss low-abundance transcripts; restricted to known gene probes [5] |

| Dynamic Range | Wider dynamic range (up to 2.6×10âµ) [5] | Narrower dynamic range (up to 3.6×10³) [5] |

| Transcript Discovery | Can detect novel transcripts, alternative splicing, and gene isoforms [5] [7] | Limited to previously annotated sequences [5] |

| Background Noise | Low background noise [6] | Higher background noise due to non-specific hybridization [8] |

| Sample Requirements | Compatible with degraded samples (e.g., FFPE) using specific protocols [9] | Requires intact RNA for optimal results [5] |

| Sample Throughput | Moderate to high | High |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 2: Performance comparison based on empirical studies

| Performance Metric | RNA-Seq | Microarray |

|---|---|---|

| Detection of Differentially Expressed Genes | Identifies 40% more DEGs compared to microarrays [5] | Fewer DEGs detected, particularly for low-abundance transcripts [5] |

| rRNA Removal Efficiency | >90% with mRNA-Seq and Ribo-Zero protocols [9] | N/A (targeted detection) |

| Reads/Bases Mapping to Transcriptome | 62.3% in mRNA-Seq; 20-30% in rRNA-depletion protocols [9] | N/A |

| Gene Detection Level | 14 million reads required to match microarray detection [9] | Standard Agilent array detects comparable gene set [9] |

| Concordance with qPCR | High concordance [10] | Moderate concordance |

Experimental Design and Protocols

RNA-Seq Experimental Workflow

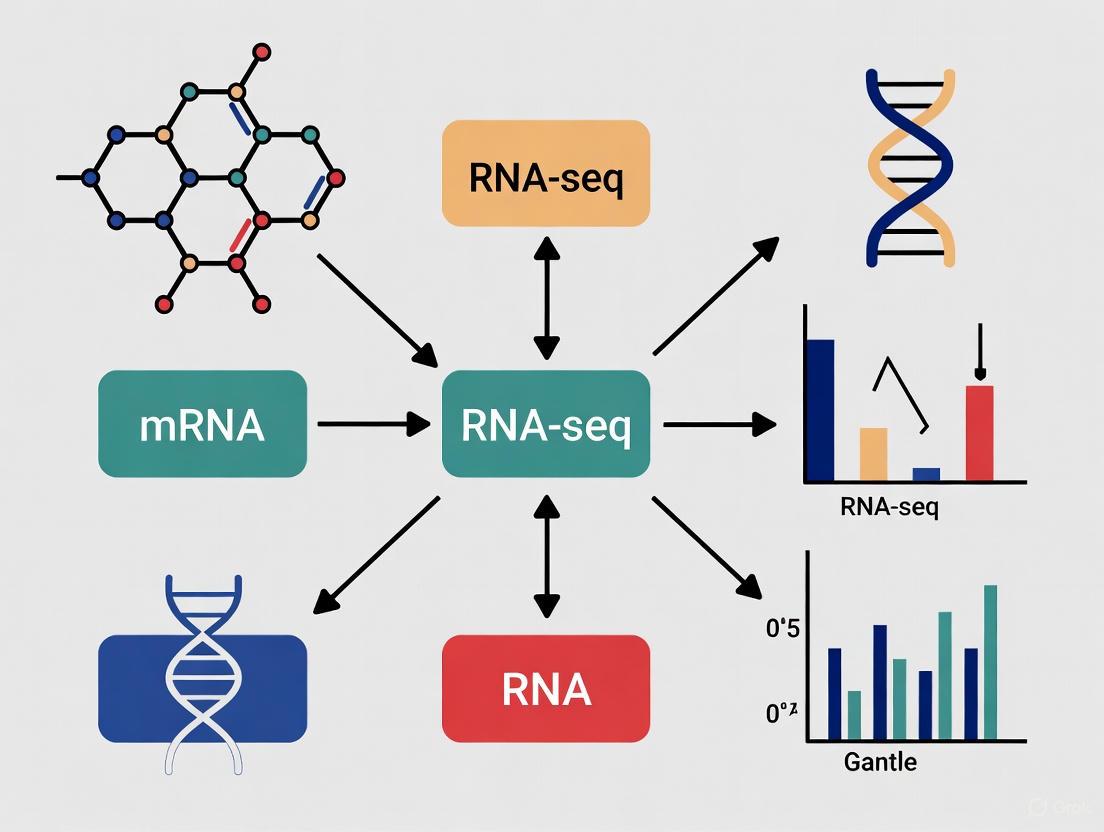

Diagram 1: RNA-Seq workflow

RNA-Seq Protocol: Detailed Methodology

Sample Preparation and Quality Control

- Isolate total RNA using silica-membrane columns or magnetic beads [8]

- Assess RNA purity using NanoDrop spectrophotometer (260/280 ratio) [8]

- Determine RNA integrity number (RIN) using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer with RNA 6000 Nano Reagent Kit [8]

- Minimum Quality Standards: RIN > 8.0, 260/280 ratio ~2.0 for optimal results [8]

Library Preparation (Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep)

- Poly(A) Selection: Purify messenger RNAs with polyA tails using oligo(dT) magnetic beads [8]

- Fragmentation: Fragment mRNA using divalent cations under elevated temperature [8]

- cDNA Synthesis:

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate Illumina sequencing adapters to blunt-ended, double-stranded cDNA fragments [8]

- Library Amplification: Enrich adapter-ligated fragments using PCR (typically 10-15 cycles) [8]

- Library QC: Validate library quality using Agilent Bioanalyzer and quantify by qPCR [8]

Sequencing

- Utilize Illumina platforms (NovaSeq, HiSeq, or MiSeq) [6]

- Recommended Sequencing Depth: 20-30 million reads per sample for standard differential expression analysis [6]

- Read Length: 75-150 bp paired-end reads recommended for transcriptome analysis [6]

Microarray Experimental Workflow

Diagram 2: Microarray workflow

Microarray Protocol: Detailed Methodology (Affymetrix Platform)

Sample Preparation and QC

- Isolate total RNA following similar protocols as RNA-Seq [8]

- Quality assessment using Nanodrop and Bioanalyzer [8]

Target Preparation (GeneChip 3' IVT PLUS Reagent Kit)

- First-Strand cDNA Synthesis: Generate single-stranded cDNA from 100-500 ng total RNA using reverse transcriptase and T7-linked oligo(dT) primer [8]

- Second-Strand cDNA Synthesis: Convert to double-stranded cDNA using DNA polymerase and RNase H [8]

- In Vitro Transcription: Synthesize biotin-labeled complementary RNA (cRNA) using T7 RNA polymerase with biotinylated UTP and CTP [8]

- cRNA Purification: Remove unincorporated nucleotides [8]

- Fragmentation: Fragment 12-20 μg cRNA using Mg²⺠at 94°C to produce 35-200 base fragments [8]

Hybridization, Staining, and Scanning

- Hybridization: Incubate fragmented cRNA with microarray chip in GeneChip Hybridization Oven 645 at 45°C for 16 hours [8]

- Washing and Staining: Process arrays on GeneChip Fluidics Station 450 using specific antibody amplification staining protocols [8]

- Scanning: Image arrays using GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G [8]

- Data Extraction: Convert image files (DAT) to cell intensity files (CEL) using GeneChip Command Console software [8]

Data Analysis Pipelines

RNA-Seq Data Analysis

Bioinformatics Workflow

Table 3: RNA-Seq bioinformatics tools and applications

| Analysis Step | Common Tools | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Quality Control | FastQC, MultiQC [6] [11] | Assess sequence quality, adapter contamination, GC content |

| Trimming | Trimmomatic, Cutadapt, fastp [6] [11] | Remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases |

| Alignment | STAR, HISAT2, TopHat2 [6] | Map reads to reference genome |

| Pseudoalignment | Kallisto, Salmon [6] | Rapid transcript quantification without full alignment |

| Quantification | featureCounts, HTSeq [6] | Generate count matrices for genes/transcripts |

| Differential Expression | DESeq2, edgeR, limma [10] [12] | Identify statistically significant DEGs |

| Functional Analysis | GSEA, clusterProfiler [12] | Pathway enrichment and biological interpretation |

Differential Expression Analysis with DESeq2

The DESeq2 package implements a robust statistical framework for differential expression analysis:

Normalization Approach

- Uses the geometric mean for normalization [12]

- Calculates size factors for each sample by comparing to a geometric mean reference sample [12]

- Assumes most genes are not differentially expressed [12]

Statistical Model

- Employs negative binomial distribution to model count data [10] [12]

- Implements shrinkage estimation for dispersion and fold changes [12]

- Uses Wald test or likelihood ratio test for significance testing [12]

Key Steps:

- Data Preprocessing: Import HTSeq-count data, filter low-count genes

- Normalization: Calculate size factors using geometric mean method

- Dispersion Estimation: Estimate gene-wise dispersions and shrink toward trended mean

- Model Fitting: Fit negative binomial generalized linear model

- Hypothesis Testing: Test for differential expression using Wald statistics

- Multiple Testing Correction: Apply Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to control false discovery rate (FDR)

Microarray Data Analysis

Data Processing Pipeline

Preprocessing Steps:

- Background Correction: Adjust for non-specific hybridization [8]

- Normalization: Apply quantile normalization to make distributions comparable across arrays [8]

- Summarization: Convert probe-level intensities to expression values using Robust Multi-array Average (RMA) algorithm [8]

Differential Expression Analysis:

- Utilize limma package for linear models with empirical Bayes moderation [10] [12]

- Apply false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple testing [12]

Application Contexts and Case Studies

Toxicogenomics and Regulatory Science

A 2025 comparative study of cannabinoids (CBC and CBN) demonstrated that while RNA-seq identified larger numbers of differentially expressed genes with wider dynamic ranges, both platforms yielded equivalent results in identifying impacted functions and pathways through gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) [8]. Importantly, transcriptomic point of departure (tPoD) values derived by benchmark concentration (BMC) modeling were comparable between platforms [8]. This suggests that for traditional transcriptomic applications like mechanistic pathway identification and concentration-response modeling, microarrays remain a viable choice, particularly considering their lower cost, smaller data size, and better-established analytical pipelines [8].

Clinical and FFPE Samples

For formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples, RNA-Seq with ribosomal RNA depletion protocols (Ribo-Zero-Seq) demonstrates significant advantages [9]. While poly(A) capture methods fail with degraded RNA from FFPE samples, rRNA depletion methods provide equivalent quantification between fresh frozen and FFPE RNAs, enabling gene expression profiling from archival clinical specimens [9].

Discovery Research vs Targeted Studies

RNA-Seq excels in discovery-oriented research where identification of novel transcripts, alternative splicing events, or genetic variants is paramount [13] [7]. Microarrays remain suitable for large-scale targeted studies focused on well-characterized gene sets, particularly when studying known pathways across many samples [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential research reagents and computational tools

| Category | Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep Kit | Library preparation for RNA-Seq |

| GeneChip 3' IVT PLUS Reagent Kit | Target preparation for microarray | |

| Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Kit | RNA quality assessment | |

| Ribo-Zero rRNA Removal Kit | rRNA depletion for degraded samples | |

| Poly(A) Magnetic Beads | mRNA enrichment for standard RNA-Seq | |

| Computational Tools | DESeq2 [12] | Differential expression analysis |

| edgeR [12] | Differential expression analysis | |

| FastQC [6] [11] | Quality control of raw sequences | |

| STAR aligner [6] | Spliced read alignment | |

| Trim Galore [11] | Adapter trimming and quality control | |

| IGV [11] | Visualization of aligned reads | |

| Icariside D2 | Icariside D2, CAS:38954-02-8, MF:C14H20O7, MW:300.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Irigenin | Irigenin, CAS:548-76-5, MF:C18H16O8, MW:360.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The choice between RNA-Seq and microarray technologies depends on multiple factors including research objectives, sample types, budget constraints, and computational resources. RNA-Seq offers superior sensitivity, broader dynamic range, and discovery capabilities for novel transcripts and isoforms [5] [7]. Microarrays provide a cost-effective, standardized approach for focused studies on known transcripts, particularly in large-scale applications [5] [8]. As sequencing costs continue to decline and analytical methods become more accessible, RNA-Seq is increasingly becoming the predominant platform for transcriptome analysis [13] [7]. However, microarrays remain relevant for specific applications where their lower cost, simpler data analysis, and established regulatory acceptance provide distinct advantages [8]. Researchers should carefully consider their specific needs, resources, and experimental goals when selecting between these powerful transcriptomic technologies.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has revolutionized molecular biology by providing a comprehensive, high-resolution view of the transcriptome—the complete set of transcripts in a cell, tissue, or organism at a specific developmental stage or physiological condition [14]. This high-throughput sequencing technique enables researchers to examine both the quantity and sequences of RNA in a sample using next-generation sequencing (NGS), revealing which genes encoded in our DNA are turned on or off and to what extent [3]. Unlike traditional microarray-based methods, RNA-seq offers several transformative advantages, including higher resolution, a broader dynamic range, and the critical ability to detect novel transcripts and alternative splicing events without dependence on prior sequence information [15] [3] [14].

The versatility of RNA-seq has made it an indispensable tool across biological research, fundamentally enhancing our ability to investigate disease mechanisms, accelerate drug discovery, and decipher developmental processes. By enabling the quantitative analysis of the transcriptome, RNA-seq provides researchers with a powerful methodology to identify genes differentially expressed between conditions—such as diseased versus healthy states—and to discover previously unannotated transcripts and alternative splicing events that can lead to diverse protein products [14]. The technology has evolved significantly since its emergence in the late 2000s, with substantial improvements in sequencing depth, read length, and data analysis tools transforming it into a widely adopted technique with applications ranging from basic research to clinical diagnostics [14].

Application in Disease Mechanism Investigation

Uncovering Molecular Basis of Pathologies

RNA-seq has become a fundamental technology for elucidating the molecular underpinnings of complex diseases, enabling researchers to move beyond descriptive phenomenology to mechanistic understanding. In neurological diseases, for instance, RNA-seq analyses have revealed specific transcriptional changes and splicing abnormalities that contribute to pathological processes [16]. The technology's ability to provide a system-wide view of transcriptional changes allows researchers to identify not just individual dysregulated genes, but entire functional networks and pathways disrupted in disease states [16]. This comprehensive approach has been particularly valuable in cancer research, where RNA-seq can detect fusion transcripts that drive oncogenesis and identify allele-specific expression patterns that may influence tumor behavior and treatment response [15].

Technical Workflow for Disease Mechanism Studies

The standard pipeline for investigating disease mechanisms through RNA-seq involves a multi-step process that transforms raw sequencing data into biological insights. The workflow begins with quality assessment of raw sequence reads using tools like FastQC, followed by grooming steps such as trimming low-quality bases [16]. Processed reads are then aligned to a reference genome using spliced aligners like Tophat2 or HISAT2, which can handle the complication of splice junctions [15] [16] [14]. Following alignment, gene expression is quantified by counting reads mapped to genomic features, and these counts are normalized to account for technical variations [16]. Differential expression analysis then identifies genes with statistically significant expression changes between disease and control conditions using specialized tools such as DESeq2 or edgeR [15] [16] [14]. The final stage involves biological interpretation through pathway analysis and gene ontology enrichment to place molecular findings in functional context [15].

Table 1: Key Analytical Tools for Disease Mechanism Investigation

| Tool Name | Application in Disease Research | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 [16] [14] | Differential gene expression analysis | Uses negative binomial distribution to model count data |

| edgeR [15] [14] | Differential gene expression analysis | Robust for experiments with limited replicates |

| STAR [16] [14] | Spliced read alignment | Fast handling of large genomes |

| FastQC [16] [14] | Quality control of raw sequences | Provides comprehensive quality metrics |

| GOSEQ [15] | Gene ontology enrichment | Accounts for transcript length bias |

Single-Cell Approaches to Disease Heterogeneity

The emergence of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has dramatically advanced disease mechanism research by enabling the investigation of cellular heterogeneity within complex tissues. This approach is particularly valuable in cancer and neurological disorders, where cellular diversity plays a crucial role in disease pathogenesis and progression [17]. The analytical workflow for scRNA-seq includes specialized steps such as cell filtering to remove low-quality cells, normalization to account for technical variations, and dimensionality reduction techniques like t-SNE and UMAP for visualization of cell populations [17] [18]. Differential expression analysis at the single-cell level can then identify molecular signatures distinguishing specific cell subtypes, potentially revealing rare pathogenic populations that might be masked in bulk tissue analyses [17].

Application in Drug Discovery and Development

Accelerating Target Identification and Validation

RNA-seq technologies have transformed early drug discovery by enabling comprehensive identification and prioritization of therapeutic targets. In pharmaceutical research, RNA-seq facilitates the discovery of novel drug targets by comparing transcriptomic profiles between diseased and healthy tissues, identifying genes with significant expression changes that may represent potential intervention points [14]. The technology's ability to detect alternative splicing events and novel transcripts further expands the universe of druggable targets beyond what was accessible through earlier genomic methods [3]. A key application in this domain is the identification of biomarkers for patient stratification, which enables the development of targeted therapies for specific molecular subtypes, ultimately contributing to more personalized and effective treatment approaches [14].

Advancing Toxicity Assessment and Compound Screening

Transcriptomic profiling using RNA-seq has become an invaluable tool for toxicological assessment during drug development. By analyzing global gene expression changes in response to compound exposure, researchers can identify potential toxicity mechanisms early in the development process, reducing late-stage failures [14]. The technology provides a more nuanced understanding of compound effects than traditional toxicological assays, revealing subtle changes in biological pathways that may indicate adverse effects [3]. Furthermore, RNA-seq enables mode-of-action studies for promising drug candidates, elucidating how compounds functionally alter cellular states by examining their effects on the transcriptome, which provides critical insights for lead optimization [3].

Table 2: Drug Discovery Applications of RNA-seq

| Application Area | RNA-seq Utility | Impact on Drug Development |

|---|---|---|

| Target Identification | Differential expression analysis between disease and normal states | Identifies novel therapeutic targets |

| Biomarker Discovery | Detection of consistently dysregulated genes or isoforms | Enables patient stratification and personalized medicine |

| Toxicology Studies | Analysis of transcriptomic changes after compound exposure | Predicts potential adverse effects earlier |

| Compound Screening | High-content assessment of compound effects on cellular transcriptomes | Prioritizes lead compounds with desired activity |

| Clinical Trial Analysis | Transcriptomic profiling of patient samples pre- and post-treatment | Provides pharmacodynamic biomarkers and mechanism evidence |

Technical Protocol for Drug Discovery Applications

A robust RNA-seq protocol for drug discovery applications requires careful experimental planning and execution. The process begins with sample preparation, where RNA is purified from appropriate model systems—such as cell lines, primary cells, or tissue samples—treated with compounds or targeting interventions [3]. The quality of isolated RNA is then rigorously assessed, as poor sample quality can severely compromise downstream analyses [3]. For transcriptome profiling, mRNA is typically enriched or ribosomal RNA depleted, followed by cDNA library preparation that includes fragmentation, adapter ligation, and amplification steps tailored to the specific sequencing platform [3]. Strand-specific protocols are preferred as they retain information about which DNA strand was transcribed, providing more comprehensive data [3]. Following sequencing, data analysis focuses not only on identifying differentially expressed genes but also on pathway enrichment to understand the broader biological processes affected by compound treatment, which helps contextualize the therapeutic potential and possible mechanisms of action [15].

Application in Developmental Biology

Elucidating Temporal Gene Regulation

Developmental biology has been profoundly transformed by RNA-seq technology, which enables detailed characterization of transcriptional dynamics throughout developmental processes. By analyzing transcriptomes across different time points, researchers can construct comprehensive timelines of gene activation and silencing that drive morphological and functional changes [14]. This temporal resolution is particularly powerful for understanding the molecular events underlying critical developmental transitions, such as embryonic patterning, organ formation, and cellular differentiation [14]. The technology's sensitivity allows detection of low-abundance transcripts, including transcription factors and signaling molecules that often play pivotal regulatory roles despite being expressed at low levels, providing unprecedented insights into the gene regulatory networks that orchestrate development.

Characterizing Cell Fate Decisions

A particularly powerful application of RNA-seq in developmental biology lies in deciphering the molecular mechanisms controlling cell fate determination and differentiation. Single-cell RNA sequencing has enabled researchers to investigate cellular heterogeneity within developing tissues and track lineage commitment in ways previously impossible [17] [18]. This approach can identify rare progenitor populations and transient cell states that are critical for proper development but would be masked in bulk tissue analyses [17]. Additionally, RNA-seq facilitates the discovery of novel transcripts and isoform switches that may drive developmental processes, expanding our understanding of how alternative splicing contributes to cellular diversity and specialization during development [14].

Experimental Framework for Developmental Studies

A specialized RNA-seq workflow is required for developmental studies to address their unique analytical challenges. The process typically begins with careful sample collection across multiple developmental stages, with particular attention to precise staging and rapid stabilization of RNA to preserve accurate transcriptional signatures [3]. Experimental designs should include sufficient biological replicates to account for natural variability between embryos or developmental systems [3]. For data analysis, specialized normalization approaches are often required to address technical variations introduced by comparing different stages, and trajectory inference algorithms can be applied to reconstruct developmental pathways from snapshot data [17]. The analysis typically extends beyond simple differential expression to include alternative splicing analysis, detection of novel developmental transcripts, and temporal clustering of co-expressed genes to identify functional modules [14].

Table 3: RNA-seq Applications in Developmental Biology

| Research Focus | RNA-seq Application | Biological Insight Gained |

|---|---|---|

| Embryonic Patterning | Temporal expression profiling across developmental stages | Identifies genes involved in axis formation and tissue specification |

| Stem Cell Differentiation | Comparison of progenitor and differentiated cell transcriptomes | Reveals regulatory networks controlling cell fate decisions |

| Organogenesis | Spatial and temporal transcriptome analysis during organ formation | Uncovers molecular mechanisms of tissue morphogenesis |

| Developmental Disorders | Comparison of wild-type and mutant model organism transcriptomes | Links genetic mutations to transcriptional consequences |

| Cellular Specialization | Single-cell RNA-seq of heterogeneous developing tissues | Maps lineage relationships and identifies rare cell types |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of RNA-seq applications depends on a suite of specialized reagents and computational tools that form the foundation of reproducible transcriptomic research.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for RNA-seq Applications

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in RNA-seq Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Quality Control Tools | FastQC [16] [14] | Assesses sequence quality of raw reads and identifies potential issues |

| Alignment Tools | Tophat2 [16], HISAT2 [14], STAR [16] [14] | Maps sequencing reads to reference genome, handling splice junctions |

| Quantification Tools | HTSeq [16], Kallisto [16] | Generates count data for genomic features (genes, transcripts) |

| Differential Expression Tools | DESeq2 [16] [14], edgeR [15] [14] | Identifies statistically significant expression changes between conditions |

| Functional Analysis Tools | GOSEQ [15], DAVID [15] | Interprets results in biological context through pathway and ontology enrichment |

| Single-Cell Analysis Tools | Partek Flow [18], Seurat | Processes scRNA-seq data with specialized normalization and clustering |

RNA-seq has firmly established itself as a cornerstone technology in biological research, providing unprecedented insights into disease mechanisms, drug discovery, and developmental biology. Its ability to comprehensively profile transcriptomes without dependence on prior sequence information has enabled discoveries across diverse biological domains, from revealing novel therapeutic targets to elucidating the temporal regulation of developmental genes [15] [14]. As the technology continues to evolve, with single-cell approaches and increasingly sophisticated analytical methods becoming more accessible, RNA-seq promises to further expand our understanding of complex biological systems. The ongoing development of standardized protocols, analytical pipelines, and data interpretation frameworks will continue to enhance the reproducibility and biological relevance of RNA-seq studies, solidifying its position as an essential tool for researchers seeking to connect genomic information with functional outcomes in health and disease [3] [16].

Core Terminology in RNA-seq Analysis

The following table defines and contextualizes the essential terminology for RNA-seq based differential gene expression analysis.

| Term | Definition | Role in RNA-seq Differential Expression |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptome | The complete set of RNA transcripts, including coding and non-coding species, in a cell at a specific point in time. [19] | Serves as the foundational entity being measured. RNA-seq provides a snapshot of the transcriptome, enabling a comparison between biological conditions to identify changes. [19] [20] |

| Read Counts | The number of sequencing reads that align to a particular gene or genomic feature. These are the raw data for quantification. [21] [20] | Represents the raw measure of a gene's expression level. Higher read counts for a gene indicate higher abundance of its mRNA. Statistical models for differential expression operate on tables of these counts. [21] |

| Fold Change (FC) | A measure of the magnitude of expression difference for a gene between two experimental conditions, typically calculated as a ratio. [22] | Provides an initial, biologically intuitive assessment of the size of an expression change. It is often used in conjunction with statistical measures to prioritize genes that are both large in magnitude and statistically reliable. [22] [23] |

| Statistical Significance | The probability that an observed expression change is not due to random chance. In RNA-seq, it is assessed using tests designed for count data. [20] [23] | Determines the reliability of observed fold changes. Given the thousands of genes tested simultaneously, standard significance is adjusted for multiple testing to avoid a high number of false positives. [24] [23] |

| False Discovery Rate (FDR) | The expected proportion of false positives among all genes declared as differentially expressed. An FDR of 5% means that 5% of the significant findings are expected to be false. [24] [25] | A critical method for correcting for multiple comparisons. Controlling the FDR, rather than the family-wise error rate (FWER), offers greater power to discover truly differentially expressed genes in high-dimensional genomic data. [24] [25] |

| q-value | The FDR analog of the p-value. A q-value threshold of 0.05 implies that 5% of the genes identified as significant are expected to be false positives. [24] [26] | Provides a directly interpretable measure for researchers when selecting a gene list for further validation. Each gene's q-value estimates the probability that it is a false discovery. [24] [26] |

Experimental Protocol: From RNA to Read Counts

This protocol details the standard wet-lab and computational steps to generate gene-level read counts from starting RNA material, which form the basis for all subsequent differential expression analysis. [19] [21] [20]

RNA Isolation and Library Preparation

- RNA Isolation: Extract total RNA from tissue or cells using a standardized isolation kit (e.g., PicoPure RNA isolation kit). Assess RNA quality and integrity using capillary electrophoresis (e.g., Agilent TapeStation) and assign an RNA Integrity Number (RIN). Only samples with high-quality RNA (e.g., RIN > 7.0) should proceed. [20]

- RNA Selection/Depletion: To enrich for signals of interest, process the isolated RNA. Common methods include:

- Poly(A) Selection: Use oligomers (e.g., poly(dT) covalently attached to magnetic beads) to selectively isolate eukaryotic mRNA with polyadenylated tails. This efficiently removes ribosomal RNA (rRNA) but will not capture non-polyadenylated RNA. [19]

- Ribosomal Depletion: Use probes complementary to rRNA to remove abundant ribosomal sequences, thereby retaining other RNA biotypes, including non-coding RNA. This is superior for degraded samples (e.g., from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue). [27] [19]

- cDNA Synthesis and Library Construction: Convert the enriched RNA into a sequencing library.

- Reverse Transcribe RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) because DNA is more stable and compatible with sequencing chemistry. [19]

- Fragment the cDNA (or RNA) via enzymes, sonication, or divalent ions to achieve appropriate fragment lengths for sequencing. [19]

- Ligate Adapters containing sequencing primer binding sites and sample-specific barcodes (indices) to the fragmented cDNA. This allows for multiplexing—pooling multiple libraries in a single sequencing lane. [19] [21]

Sequencing and Read Alignment

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Sequence the prepared libraries on a platform such as an Illumina NextSeq, which uses sequence-by-synthesis technology with reversible terminators. The output is raw sequencing reads in FASTQ file format. [19] [20]

- Read Alignment (Mapping): Align the sequencing reads from the FASTQ files to a reference genome (e.g., mm10 for mouse) using a specialized aligner. Common tools include:

- HISAT2: A fast and sensitive aligner for mapping next-generation sequencing reads. [21]

- STAR: A splice-aware aligner that is highly accurate for RNA-seq reads which must be mapped across exon-intron boundaries. [21]

- Subread: An aligner that uses a mapping paradigm based on exact subread matching. [21] This step results in a BAM file, a binary format containing all reads and their genomic coordinates.

Generation of Read Counts Table

- Read Counting: Process the aligned reads in the BAM file to count the number of reads overlapping with each annotated gene. Tools like HTSeq are commonly used for this purpose. [20] The final output is a table of raw read counts, where each row represents a gene and each column represents a sample. This count table is the direct input for statistical differential expression analysis. [21]

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete process from sample to countable data.

Quantitative Analysis and Statistical Frameworks

Fold Change (FC) Estimation and the Limit Fold Change Model

Fold change is a foundational metric, but its interpretation must be informed by absolute expression levels. The Limit Fold Change (LFC) model provides a sophisticated approach to this by recognizing that the variance of gene expression is a function of its absolute intensity. [22]

- Background: Using a single, arbitrary FC cutoff (e.g., 2.0) across all expression levels is problematic. Lowly expressed genes have greater inherent measurement error and are more likely to meet an arbitrary FC cutoff by chance, while highly expressed genes with less error may not meet the cutoff even when truly differential. [22]

- Protocol for LFC Model Application:

- Data Preprocessing: Set a minimal absolute expression threshold (At) to filter out noise (e.g., all values < 20 are set to 20). Remove genes with no measurable expression across all samples. [22]

- Calculate Fold Change: For each gene, compute the Highest Fold Change (HFC), defined as the maximum ratio of expression between any two experimental conditions. [22]

- Bin Genes by Expression Level: Systematically bin the remaining genes into narrow ranges based on their absolute expression levels. [22]

- Define the Limit Function: For each bin, evaluate the top X% of highest fold changes. Fit a function through these values across all bins. This function defines the limit fold change above which genes are considered outliers from the natural variability trend and thus likely to be truly differentially expressed. [22]

- Gene Selection: Select genes whose FC lies above the limit function for their respective expression bin. This model has been validated to show high concordance (85.7%) with RT-PCR data. [22]

Managing Multiple Testing with FDR and q-values

In an RNA-seq experiment, thousands of statistical tests (one per gene) are performed simultaneously, dramatically increasing the likelihood of false positives. The following table compares approaches to this problem.

| Method | Core Principle | Implication for RNA-seq Discovery | Key Advantage/Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Per Comparison Error Rate (PCER) | Controls the expected number of false positives out of all hypothesis tests. [24] | With 10,000 genes tested at alpha=0.05, 500 false positives are expected. | Too liberal for genomic studies as it guarantees a high number of false discoveries. [24] |

| Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER) | Controls the probability of at least one false positive among all tests. [24] | Stringent control, often implemented via the Bonferroni correction (alpha/# of tests). [24] | Too conservative, leading to many missed true discoveries (low power). [24] |

| False Discovery Rate (FDR) | Controls the expected proportion of false positives among all genes declared significant. [24] [25] | An FDR of 5% means that among 100 significant genes, ~5 are expected to be false positives. [24] | Ideal balance, offering greater power than FWER while controlling a meaningful error rate. [24] [25] |

- The Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) Procedure: A standard method for controlling FDR.

- Sort the p-values for all m genes from smallest to largest: P~(1)~ ≤ P~(2)~ ≤ ... ≤ P~(m)~.

- Find the largest k such that P~(k)~ ≤ (k / m) * α, where α is the desired FDR level (e.g., 0.05).

- Declare the genes corresponding to the first k p-values as differentially expressed. [25]

- q-values: The q-value of a gene is the minimum FDR at which that gene would be called significant. [24] It is an FDR-adjusted p-value. If a gene has a q-value of 0.03, it means that 3% of the genes that are as or more extreme than this gene are expected to be false positives. [24] [26] This provides a direct and intuitive measure for ranking and filtering genes.

The following diagram outlines the logical decision process for incorporating fold change and FDR in a robust differential expression analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Category | Item | Function in RNA-seq Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit [20] | For the extraction of high-quality total RNA from small numbers of cells or sorted populations, critical for single-cell or low-input protocols. |

| NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Kit [20] | For the enrichment of eukaryotic mRNA from total RNA by capturing the polyadenylated tail, reducing ribosomal RNA contamination. | |

| DNase I [20] | For the digestion of genomic DNA that may co-purify with RNA, preventing its amplification and interference in sequencing. | |

| Library Construction | NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit [20] | A widely used kit for the conversion of RNA into a sequencing-ready cDNA library, including steps for fragmentation, adapter ligation, and PCR enrichment. |

| Duplex-Specific Nuclease (DSN) [27] | An enzyme used to normalize cDNA libraries by degrading abundant (e.g., ribosomal) sequences, improving the coverage of less abundant transcripts. | |

| Sequencing & Analysis | Illumina Sequencing Platform (e.g., NextSeq 500) [20] | The workhorse technology for high-throughput, short-read sequencing, generating the raw FASTQ data files. |

| Alignment Software (HISAT2, STAR) [21] | Bioinformatics tools for accurately mapping sequencing reads to a reference genome, a crucial step before quantification. | |

| Counting Software (HTSeq) [20] | The tool that generates the final read counts table by summarizing the number of reads aligned to each genomic feature (e.g., gene). | |

| Bonducellin | Bonducellin, MF:C17H14O4, MW:282.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Yadanziolide B | Yadanziolide B, MF:C20H26O11, MW:442.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has emerged as a powerful genome-wide tool for measuring gene expression with unprecedented resolution. This application note provides a comprehensive protocol for conducting a complete RNA-seq study focused on differential gene expression analysis, covering critical stages from sample preparation through computational data interpretation. We outline robust methodologies for RNA extraction, library preparation, quality control, sequencing alignment, and statistical analysis for identifying differentially expressed genes. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide emphasizes best practices to ensure data integrity and reproducible results, framed within the broader context of transcriptomics research.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) is a methodology for RNA profiling based on next-generation sequencing that enables the measurement and comparison of gene expression patterns at unprecedented resolution [28]. As a powerful genome-wide gene expression analysis tool, RNA-seq can provide insights into cellular and disease mechanisms, allowing researchers to identify genes that are upregulated or downregulated under various experimental conditions, such as the presence of genomic mutations, drugs, or chemical stress [29]. The fundamental workflow involves extracting RNA molecules, converting them to a cDNA library, sequencing, aligning reads to a reference genome, and subsequently analyzing the data [29]. This application note details each step of this process, with a particular focus on differential gene expression analysis, which is essential for understanding gene function and regulation in biological systems and disease states.

Sample Preparation and RNA Extraction

RNA Extraction Methods

The initial phase of RNA-seq is critical, as the quality of extracted RNA directly impacts all subsequent steps. Obtain pure, high-quality RNA by carefully considering tissue storage conditions; RNA is more unstable than DNA, so long-term storage should be at -80°C to prevent degradation and ensure molecular integrity. RNA stabilization reagents can further help preserve RNA during storage and thawing [30].

For standard RNA-seq library preparation, start with between 100 ng to 1 µg of purified total RNA, with at least 500 ng often recommended by core facilities [30]. Several extraction methods are available, each with distinct advantages:

- Organic Extraction (e.g., TRIzol): Utilizes phenol and guanidinium thiocyanate in a single-phase solution to denature proteins and separate RNA from DNA and proteins. The mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit is an example that allows isolation of both small and large RNA molecules [30].

- Filter-Based Spin Column Methods: Uses silica-based membranes that bind RNA under specific buffer conditions. The PureLink RNA Mini Kit exemplifies this approach, providing a simple, reliable, rapid method for isolating large RNA molecules (mRNA and rRNA) but is not automation-compatible [30].

- Magnetic Particle Methods: Employs magnetic beads coated with RNA-binding matrices, ideal for high-throughput applications. The MagMAX for Microarrays Total RNA Isolation Kit is plate-based, automation-compatible, and can process up to 96 samples in under one hour [30].

Table 1: Comparison of RNA Extraction Kits for RNA-seq

| Product Name | Best For | Starting Material | RNA Types Isolated | Isolation Method | Prep Time | Automation Compatible? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PureLink RNA Mini Kit | Simple, reliable, rapid method | Bacteria, blood, cells, liquid samples | Large RNA only (mRNA, rRNA) | Silica spin column | 20 min | No |

| mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit | microRNA and total RNA | Bacteria, cells, tissue, viral samples | Small & large RNA molecules | Organic extraction + silica column | 30 min | No |

| MagMAX for Microarrays Total RNA Isolation Kit | High-throughput stringent applications | Blood, cells, liquid samples, tissue | Small & large RNA molecules | Organic extraction + magnetic beads | <1 hr | Yes |

| Dynabeads mRNA DIRECT Kit | mRNA sequencing | Cell lysate | mRNA only | Magnetic bead capture | 15 min | No |

| MagMAX FFPE DNA/RNA Ultra Kit | High-throughput from FFPE tissue | FFPE curls | Total RNA, microRNA, gDNA | Magnetic beads | 48 min (96 preps) | Yes |

RNA Storage and Quality Control

Once extracted, RNA must be stored in an RNase-free environment. Assess RNA quality and integrity using methods such as RNA Integrity Number (RIN), with higher RIN values (typically >8) indicating better RNA quality, especially important for poly(A) selection protocols [31].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

RNA Enrichment

To maximize relevant RNA-seq reads and reduce non-transcriptome related RNA (such as abundant ribosomal RNA), enrich for specific RNA targets. The two primary enrichment strategies are:

- Poly(A) Selection: Enriches for messenger RNA by capturing the polyadenylated tail. This requires RNA with minimal degradation (high RIN) but may miss non-polyadenylated transcripts [31].

- Ribosomal Depletion: Uses probes to remove ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which typically constitutes over 90% of total RNA. This is suitable for degraded samples (like FFPE tissues) or bacterial samples where mRNA is not polyadenylated. RiboMinus technology can deplete up to 99.9% of rRNA [30] [31].

Consider whether to generate strand-preserving libraries, which retain information about the DNA strand from which the RNA was transcribed. Strand-specific protocols, such as the widely used dUTP method, are crucial for accurately analyzing antisense or overlapping transcripts [31].

Library Construction and Controls

Library construction involves converting RNA into cDNA with adapters ligated to the ends, then amplifying the cDNA using primers complementary to the adapters [30]. For data validation and comparison between runs, use controls such as the External RNA Controls Consortium (ERCC) RNA Spike-In Mixes. These synthetic RNA mixes help quantify fold-change in expression levels and measure the dynamic range and lower limit of detection of the RNA-seq assay [30].

To increase throughput and reduce costs, utilize RNA barcoding (indexing), which assigns unique identifiers to samples, allowing multiple libraries to be pooled and sequenced in a single run [30].

Sequencing Considerations

Key sequencing parameters include:

- Read Type: Single-end (SE) or paired-end (PE). PE is preferable for de novo transcript discovery or isoform expression analysis [31].

- Read Length: Longer reads improve mappability and transcript identification [31].

- Sequencing Depth: The number of sequenced reads per sample. While five million mapped reads may suffice to quantify medium-highly expressed genes, 100 million reads may be needed for precise quantification of low-abundance transcripts [31].

- Replicates: The number of biological replicates is crucial for statistical power. The number depends on technical variability, biological variability of the system, and the desired statistical power for detecting expression differences [31].

Computational Data Analysis

Quality Control Checkpoints

Quality control should be applied at multiple stages of the analysis pipeline [31].

- Raw Reads: Analyze sequence quality, GC content, adaptor presence, overrepresented k-mers, and duplicated reads to detect sequencing errors or contamination. Use tools like FastQC [31] or Trimmomatic [29] to trim adapters and remove poor-quality bases.

- Read Alignment: Map reads to a reference genome or transcriptome using aligners such as bowtie2 [29] or tophat [29]. Monitor the percentage of mapped reads (70-90% expected for human genome), uniformity of read coverage, and strand specificity. Tools like RSeQC [31] or Qualimap [31] are useful here.

- Quantification: Generate a count matrix representing the number of reads mapped to each genomic feature (e.g., genes, exons) for each sample using tools like htseq-count [32] [29]. Check for GC content and gene length biases.

The following diagram illustrates the major steps of the RNA-seq data analysis workflow:

Read Alignment and Quantification

Alignment involves mapping the processed reads to a reference genome or transcriptome. For organisms with well-annotated genomes, mapping against the genome is standard. For organisms without a reference genome, a de novo transcriptome assembly is required [31]. The output is a count matrix, where rows represent genomic features (genes), columns represent samples, and values are the number of reads mapped to each feature [32] [33]. This matrix is the primary input for differential expression analysis.

Normalization and Data Transformation

The raw count matrix must be normalized to account for differences in sequencing depth and gene length. While RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads) and FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase per Million) are common normalization methods [33], for differential expression analysis, methods used by packages like DESeq2 and edgeR are preferred as they model the count data more accurately.

For quality control and visualization, data transformation is often necessary. The DESeq2 package offers a variance stabilizing transformation (VST) that removes the dependence of the variance on the mean, making the data more suitable for techniques like principal component analysis (PCA) and clustering [32].

Differential Expression Analysis

Statistical Testing for Differential Expression

Differential expression analysis identifies genes whose expression levels change significantly between experimental conditions (e.g., treated vs. untreated). This is performed using statistical methods that model the count data, typically employing a negative binomial distribution to account for over-dispersion common in sequencing data [33].

Two main R packages are widely used for this analysis:

- DESeq2: Provides methods for testing differential expression based on a model using the negative binomial distribution. It includes steps for data normalization, dispersion estimation, and statistical testing [32] [29].

- edgeR: Uses a similar statistical approach, also based on the negative binomial distribution, and is particularly powerful for experiments with a small number of replicates [32].

The analysis begins by creating a DESeqDataSet or DGEList object from the count matrix and sample information. The statistical test will then compare expression levels between the groups defined in the experimental design (e.g., "PrimarysolidTumor" vs. "SolidTissueNormal") [32].

Visualization and Interpretation

Visualization is critical for interpreting the results of a differential expression analysis.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Reduces the dimensionality of the data to visualize the overall similarity between samples. In a well-controlled experiment, biological replicates should cluster together, and samples from different conditions should separate [32].

- Sample-Sample Heatmaps: Display hierarchical clustering of samples based on their gene expression profiles, providing another view of sample relatedness [32].

- Volcano Plots: Show the relationship between the statistical significance (p-value or adjusted p-value) and the magnitude of change (fold change) for all tested genes, allowing for the easy identification of the most significantly deregulated genes.

- MA Plots: Visualize the differences between two sample groups by plotting the average expression (M) versus the log fold change (A) for each gene.

After identifying a list of differentially expressed genes, perform functional analysis using gene ontology (GO) enrichment or pathway analysis (e.g., KEGG) to understand the biological processes, molecular functions, and pathways that are most affected in the experiment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Successful execution of an RNA-seq study requires a combination of wet-lab reagents and computational tools. The following table details key solutions and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Software for RNA-seq

| Category | Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction | PureLink RNA Mini Kit | Reliable, rapid isolation of large RNA molecules via silica spin column [30]. |

| mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit | Isolation of both small (e.g., miRNA) and large RNA molecules using organic extraction [30]. | |

| MagMAX Kits | High-throughput, automation-compatible RNA isolation using magnetic beads [30]. | |

| Library Prep | RiboMinus Technology | Depletes ribosomal RNA (up to 99.9%) to enrich for transcriptome-wide RNA [30]. |

| ERCC RNA Spike-In Mixes | External RNA controls for validating data and comparing results between runs [30]. | |

| Sequencing | Illumina Platforms | Short-read sequencing (150-300 bp); most common platform for RNA-seq [29]. |

| PAC Biosystem & Nanopore | Long-read sequencing (up to several Kbp-Mbp) for improved transcript isoform detection [29]. | |

| Quality Control | FastQC | Quality control tool for high throughput sequence data (raw reads) [29]. |

| Trimmomatic | Flexible read trimming tool for Illumina data to remove adapters and low-quality bases [29]. | |

| Alignment | bowtie2 / tophat | Fast and memory-efficient alignment of short sequencing reads to a reference genome [29]. |

| STAR | Spliced read aligner for RNA-seq data. | |

| Quantification | htseq-count | Feature counting tool to generate count matrix from aligned reads [29]. |

| Differential Expression | DESeq2 | R/Bioconductor package for differential analysis of count data using negative binomial distribution [32] [29]. |

| edgeR / limma | R/Bioconductor packages for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data [32]. | |

| Visualization | RColorBrewer / pheatmap | R packages for creating color palettes and heatmaps [32]. |

| PCAtools | R package for Principal Component Analysis and visualization [32]. | |

| Integrated Genomics Viewer (IGV) | High-performance visualization tool for interactive exploration of large genomic datasets [29]. | |

| HIV Protease Substrate IV | HIV Protease Substrate IV, CAS:128340-47-6, MF:C49H83N15O13, MW:1090.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-phenyl-1H-1,2,3-triazole | 4-Phenyl-1H-1,2,3-triazole|CAS 1680-44-0 | 4-Phenyl-1H-1,2,3-triazole is a versatile chemical reagent for HIV-1 and cancer research. This product is for research use only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

This application note has outlined a complete workflow for RNA-seq analysis, from critical sample preparation steps through the computational identification of differentially expressed genes. The robustness of the final results depends on careful execution at every stage: high-quality RNA extraction, appropriate library preparation and sequencing strategies, rigorous quality control, and the use of statistically sound methods for differential expression testing. By following this structured protocol and utilizing the essential tools detailed in the Scientist's Toolkit, researchers can reliably generate and interpret RNA-seq data to uncover meaningful biological insights in fields ranging from basic molecular biology to drug development.

RNA-seq DGE Methodologies: From Experimental Design to Computational Analysis

Ribonucleic acid sequencing (RNA-seq) has become the predominant method for genome-wide differential gene expression (DGE) experiments, enabling researchers to quantify transcriptional changes with unprecedented resolution and accuracy [6] [10]. The reliability of conclusions drawn from RNA-seq data, however, is profoundly influenced by upstream experimental design decisions. Choices regarding biological replication, sequencing depth, and library read configuration establish the fundamental limits of an experiment's statistical power, reproducibility, and biological validity [34] [35]. Within the broader context of a thesis on RNA-seq for differential gene expression analysis, this document provides detailed application notes and protocols focused on these three critical design parameters. By optimizing these elements, researchers and drug development professionals can ensure their experiments are robustly designed to detect true biological signals with confidence, thereby generating meaningful data for downstream analysis and interpretation.

The Critical Role of Biological Replication

Biological replicates—samples representing distinct biological units processed independently through the entire experimental workflow—are essential for capturing the natural variation within a population and for enabling statistically sound inference to that population [36]. The number of replicates directly determines an experiment's ability to distinguish true differential expression from background noise.

Quantitative Guidelines for Replicate Numbers

Evidence-based recommendations for biological replication have been established through systematic benchmarking studies. While three biological replicates are often considered an absolute minimum for any statistical inference, this number provides limited detection power [35]. A landmark study performing an RNA-seq experiment with 48 biological replicates per condition demonstrated that with only three replicates, most differential expression tools identified a mere 20–40% of the significantly differentially expressed (SDE) genes detectable with 42 replicates [35]. Performance improves substantially for genes with large expression changes; for SDE genes altering expression by more than fourfold, over 85% can be detected with just three replicates. However, to achieve >85% detection power for all SDE genes, regardless of their fold-change magnitude, more than 20 biological replicates are required [35]. For typical research applications, a minimum of six biological replicates is advised, increasing to at least 12 when it is critical to identify SDE genes across all fold changes [35].

Table 1: Recommended Number of Biological Replicates Based on Experimental Goals

| Experimental Goal | Minimum Recommended Replicates | Detection Power & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Exploratory/Pilot Studies | 3 (absolute minimum) | Limited power; detects only 20-40% of all SDE genes, but >85% of >4-fold changes [35]. |

| Standard DGE Analysis | 6 | Superior combination of true positives and false positives; recommended for most studies [35]. |

| High-Resolution DGE | 12+ | >85% power to detect SDE genes of all fold changes; essential for subtle but biologically important changes [35]. |

Replicates versus Sequencing Depth

A critical trade-off in experimental design involves allocating resources between additional biological replicates and greater sequencing depth. Multiple studies conclusively demonstrate that increasing the number of replicate samples provides substantially greater detection power for differential expression than increasing the number of sequenced reads per sample [10] [35]. Therefore, for a fixed budget, prioritizing more biological replicates over deeper sequencing is almost always the optimal strategy for DGE analysis.

Determining Optimal Sequencing Depth

Sequencing depth refers to the number of sequenced reads per sample and directly influences the ability to detect and quantify transcripts, especially those that are lowly expressed.

Depth Recommendations by Application

The appropriate sequencing depth depends on the complexity of the transcriptome and the specific research objectives. For standard DGE analyses focusing on coding messenger RNA, a depth of 20–30 million paired-end reads per sample is often sufficient [6]. The National Cancer Institute's CCR Best Practices guidelines recommend 10–20 million paired-end reads for mRNA library preps using high-quality RNA (RIN > 8) [34]. When the research interest extends to long non-coding RNAs, or if the RNA sample is partially degraded, a total RNA library prep method is recommended, with a higher sequencing depth of 25–60 million paired-end reads [34]. Adequate depth ensures sufficient coverage across a wide dynamic range of expression levels, but excessive depth provides diminishing returns; the resources are typically better invested in additional biological replicates [10].

Table 2: Sequencing Depth Guidelines for Different RNA-seq Applications

| Library Type / Research Focus | Recommended Sequencing Depth (Paired-End Reads) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| mRNA (Coding Transcripts) | 10 - 30 million | Requires high-quality RNA (RIN > 8) [34] [6]. |

| Total RNA (incl. Non-Coding RNA) | 25 - 60 million | Suitable for degraded RNA samples; captures a broader transcriptome [34]. |

| Differential Gene Expression | 20 - 30 million | Standard depth for most DGE studies; balance with replication [6]. |

Configuring Read and Strand Specificity

The configuration of sequencing reads—whether single-end or paired-end—and the strandedness of the library are crucial technical considerations that impact data quality, mappability, and interpretability.

Paired-End vs. Single-End Reads

In paired-end sequencing, both ends of a DNA fragment are sequenced, generating "read 1" and "read 2." In a standard Illumina paired-end run, these reads are expected to align to the forward and reverse strands, respectively, pointing toward each other; this is known as "FR" orientation [37]. Paired-end configuration provides several advantages: it improves the accuracy of read alignment, especially across splice junctions, and facilitates the detection of structural variants. While single-end sequencing is more economical, paired-end sequencing is generally recommended for de novo transcriptome assembly and for regions with complex or repetitive sequences [34]. For standard DGE analysis in a well-annotated organism, single-end sequencing may be sufficient, but paired-end is preferred for its robustness.

Strand-Specific Library Preparation

Stranded (strand-specific) RNA-seq libraries preserve the information about which original DNA strand the RNA was transcribed from. This prevents ambiguity in assigning reads to genes that overlap on opposite strands and allows for the identification of antisense transcription. Common methods for creating stranded libraries include dUTP-based methods (e.g., Illumina TruSeq Stranded Total RNA) and ligation-based methods [38]. The strandedness of the library must be correctly specified during data analysis for tools that rely on this information for read counting and quantification. Mis-specification can lead to a significant loss of data or incorrect gene assignment.

Table 3: Common Strand-Specific Library Types and Corresponding Software Settings

| Library Type (Example Kits) | Common Designation | HISAT2 (--rna-strandness) |

featureCounts (-s) |

HTSeq (--stranded) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstranded (Standard Illumina) | fr-unstranded |

NONE |

0 |

no |

| Stranded (dUTP Method) (NEBNext Ultra II Directional) | RF/fr-firststrand |

R |

2 |

reverse |

| Stranded (Ligation Method) (NuGEN Encore) | FR/fr-secondstrand |

F |

1 |

yes |

Integrated Experimental Workflow

A well-designed RNA-seq experiment integrates all aforementioned considerations into a coherent workflow, from initial planning to final data interpretation. The following diagram summarizes this end-to-end process, highlighting key decision points for replicates, depth, and configuration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for executing a robust RNA-seq experiment, along with their critical functions in the workflow.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq Experiments

| Item | Function & Importance in RNA-seq Workflow |

|---|---|

| Strand-Specific RNA Library Prep Kit (e.g., Illumina TruSeq Stranded, NEBNext Ultra II Directional) | Converts RNA into a sequence-ready library while preserving strand-of-origin information, which is crucial for accurate transcript assignment [38]. |

| RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 8 | A critical quality metric for mRNA library prep. High-quality RNA is essential for generating representative libraries and avoiding 3' bias [34]. |

| High-Quality Reference Genome & Annotation (GTF/GFF file) | Essential for read alignment and gene quantification. The accuracy and completeness of annotation directly impact all downstream analyses [16]. |

| Barcoded Index Adapters | Enable multiplexing of multiple samples in a single sequencing lane, reducing batch effects and costs [34]. |

| Spike-In RNA Controls | Exogenous RNA added in known quantities to the sample. Useful for monitoring technical performance and sometimes for normalization [34]. |

| RNA-seq Aligned Software (e.g., STAR, HISAT2) | Maps sequenced reads to the reference genome, identifying which genes and isoforms are expressed. HISAT2 is recommended for standard DGE due to its speed and accuracy [6]. |

| Differential Expression Analysis Tool (e.g., DESeq2, edgeR) | Statistical software that identifies genes with significant expression changes between conditions. DESeq2 and edgeR are widely adopted and perform well [35]. |

| Simmondsin | Simmondsin, CAS:51771-52-9, MF:C16H25NO9, MW:375.37 g/mol |

| Milbemycin A4 | Milbemycin A4, CAS:51596-11-3, MF:C32H46O7, MW:542.7 g/mol |