RNA-seq Normalization Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a systematic comparison of RNA-seq normalization methods, addressing critical challenges in transcriptomic data analysis for researchers and drug development professionals.

RNA-seq Normalization Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of RNA-seq normalization methods, addressing critical challenges in transcriptomic data analysis for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore foundational concepts of normalization necessity, categorize methodological approaches by their underlying assumptions and applications, troubleshoot common pitfalls in data with high variability or global expression shifts, and validate method performance using established evaluation protocols and metrics. By synthesizing evidence from multiple benchmarking studies, this guide offers practical recommendations for selecting optimal normalization strategies to ensure accurate biological interpretations in differential expression analysis and clinical research applications.

The Critical Role of Normalization in RNA-seq Analysis: Understanding Sources of Technical Variation

FAQs: Core Concepts and Common Issues

Q1: What is the primary goal of normalizing RNA-seq data? The main goal is to adjust raw gene expression data to account for non-biological technical variations. This ensures that observed differences in gene expression between samples truly reflect underlying biology rather than technical artifacts like differing sequencing depths, variations in gene length, or sample-specific RNA composition [1] [2].

Q2: What are the key technical biases that normalization corrects for? Normalization primarily addresses three sources of technical bias [1] [2]:

- Sequencing Depth: The total number of reads obtained can vary per sample. Without correction, a sample with more reads would falsely appear to have higher gene expression.

- Gene Length: Longer genes generate more sequencing fragments than shorter genes expressed at the same biological level. Normalization enables meaningful comparison of expression levels between different genes within the same sample.

- RNA Composition: This bias occurs when a few highly expressed genes consume a large fraction of the sequencing reads in a sample, distorting the expression levels of all other genes. This is particularly important in experiments with global shifts in expression profiles.

Q3: My normalized data seems to have removed a biological signal I expected. What could be wrong? Some normalization methods, particularly those used for differential expression analysis like TMM and RLE, operate on the assumption that the majority of genes are not differentially expressed [3] [2]. If your experimental condition (e.g., a treatment causing widespread transcriptional shutdown) violates this core assumption, the normalization can be biased, potentially removing true biological signal. In such cases, exploring alternative strategies, such as using a spike-in control, may be necessary.

Q4: I am integrating multiple RNA-seq datasets from public repositories. Why is normalization still crucial? When combining datasets, you introduce "batch effects"—technical variations resulting from different laboratories, sequencing platforms, or library preparation dates [1]. These effects can be the strongest source of variation in the combined data, completely masking true biological differences. Normalization across datasets using batch correction methods like ComBat or Limma is essential to remove these confounders before any integrated analysis [1].

Q5: How does RNA quality impact normalization and downstream results? RNA quality, often measured by the RNA Integrity Number (RIN), is a critical factor that normalization cannot fully correct. Degraded RNA, with a low RIN, can lead to severe biases, especially against longer transcripts [4]. For poly(A)-enriched libraries, degradation directly impacts the 3' end of transcripts. While rRNA depletion methods can perform better with moderately degraded samples, high-quality RNA (RIN > 7 is a common threshold) is always recommended for accurate results [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Variability Between Biological Replicates After Normalization

Problem: Even after normalization, your biological replicates within the same condition show unacceptably high variability in their gene expression profiles.

Solutions:

- Check Experimental Design: Ensure you have a sufficient number of biological replicates. While three is often considered a minimum, more replicates are needed when biological variability is inherently high [5]. A lack of replication makes it impossible to distinguish technical noise from true biological variance.

- Re-assess RNA Quality: Re-check the RNA Integrity Numbers (RIN) and electropherograms from all samples. Degradation or DNA contamination (indicated by 260/280 and 260/230 ratios) can cause irreparable bias that normalization cannot fix [4].

- Verify Normalization Method: For differential expression analysis, ensure you are using a "between-sample" method like TMM (from edgeR) or RLE (from DESeq2). Using "within-sample" methods like TPM or FPKM for this purpose will not adequately control for variability between samples [3] [5] [1].

- Investigate Batch Effects: Confirm that your library preparation and sequencing were not confounded with your experimental groups. If all samples from one condition were processed on one day and the other on another day, this batch effect can introduce major variability. Use multivariate methods or batch correction tools in your analysis if this is the case [1] [6].

Issue 2: Choosing the Wrong Normalization Method for Your Analysis Goal

Problem: Your analysis yields confusing or biologically implausible results, which may be due to an inappropriate normalization method.

Solutions: Use the following table and logic to select the correct method. First, identify your primary goal, then consider your data type to narrow down the appropriate normalization technique.

Decision Guide: Normalization Method Selection

| Analysis Goal | Recommended Method(s) | Key Rationale | Common Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compare expression between different genes (Within a single sample) | TPM, FPKM/RPKM [1] [2] | Corrects for gene length & sequencing depth, enabling cross-gene comparison. | Not suitable for between-sample comparisons in DE analysis; sensitive to RNA composition bias [2]. |

| Compare a gene's expression across samples (Between samples) | TPM (for direct comparison), TMM, RLE (for DE analysis) [3] [1] | TPM sums to 1M per sample, aiding cross-sample comparison. TMM/RLE are designed for DE statistical frameworks. | Using FPKM for cross-sample comparison is discouraged due to inconsistent sum across samples [1]. |

| Differential Expression Analysis (Identify significant changes) | TMM (edgeR), RLE (DESeq2) [3] [5] [2] | Robustly accounts for library size and RNA composition; integrated into statistical models for DE testing. | Assumes most genes are not DE. Violation of this assumption (e.g., global transcriptomic shifts) can bias results [2]. |

| Integrating multiple datasets (Removing batch effects) | Limma, ComBat [1] | Uses statistical models to explicitly remove known batch effects while preserving biological signal. | Requires prior knowledge of batches (e.g., lab, date). Must be applied after within-dataset normalization. |

Issue 3: Poor Performance in Downstream Applications

Problem: After normalization, your data performs poorly in a specific downstream task, such as building metabolic models or disease classification.

Solutions:

- For Metabolic Modeling (GEMs): If you are mapping RNA-seq data onto Genome-scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) using algorithms like iMAT or INIT, benchmark studies show that between-sample normalization methods (RLE, TMM, GeTMM) produce more consistent and accurate models than within-sample methods (TPM, FPKM) [3] [7]. Consider re-normalizing your data with one of these recommended methods.

- For Disease Diagnosis/Classification: Some studies surprisingly suggest that raw count data, when used with appropriate statistical models (e.g., in DESeq2), can sometimes perform as well as or better than pre-normalized data (e.g., RPKM) for machine learning-based disease diagnosis [8]. This is because some normalization methods can reduce data entropy and potentially obscure signals. If diagnosis is your goal, benchmark your model performance using both raw counts (handled by a tool's internal normalization) and pre-normalized data.

- Validate with Positive Controls: If available, use positive control genes known to be affected by your experiment (e.g., from qPCR validation) to check if the normalization method recovers the expected fold-change direction and magnitude.

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

Protocol 1: Evaluating Normalization Efficacy Using Variance Analysis

This protocol helps you determine if your chosen normalization method effectively increases the proportion of variability attributable to biology versus technical noise [9].

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Begin with your raw count matrix.

- Application of Methods: Apply the normalization methods you wish to evaluate (e.g., TPM, TMM, RLE, Quantile) to the raw data.

- Statistical Modeling: For each normalized dataset, perform a two-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) for each gene. The model should be:

Expression ~ Batch + Condition, where "Batch" represents a known technical factor (e.g., sequencing lane) and "Condition" represents your biological groups. - Variance Decomposition: For each gene, calculate the proportion of total variance explained by the

Condition(desired biological signal) and theBatch(technical noise). - Evaluation: A successful normalization method will, on average across all genes, increase the proportion of variance explained by

Conditionand decrease the proportion fromBatchand residual error compared to the raw data [9].

Protocol 2: Testing for Linearity and Absence of Spurious Structure

This test checks if a normalization method preserves known linear relationships between samples or inadvertently introduces artificial patterns [9].

Methodology:

- Sample Design: Create mixture samples with known proportions (e.g., 75% from Sample A and 25% from Sample B; 50%/50%; 25%/75%).

- Sequencing and Processing: Sequence the original samples (A and B) and the mixture samples. Process all samples through your pipeline, including the normalization method to be tested.

- Linearity Check: For a set of housekeeping or non-differentially expressed genes, plot the expression values of the mixture samples against the values of the original samples. The values should fall on a straight line.

- Interpretation: A good normalization method will preserve this linear relationship. Methods that fail this test by introducing non-linear patterns (e.g., some implementations of Quantile normalization have been shown to do this) are adding unwanted structure to your data and should be avoided [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Materials for Robust RNA-seq Normalization

| Item | Function in Context of Normalization | Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization Reagents(e.g., PAXgene) | Preserves RNA integrity at collection, especially for sensitive samples like blood. Prevents degradation bias that normalization cannot fix [4]. | Critical for clinical or field samples where immediate freezing is not possible. |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA, increasing the sequencing depth of informative mRNAs and ncRNAs. This reduces required sequencing cost and complexity for normalization [4]. | More effective than poly-A selection for degraded samples or those rich in non-polyadenylated RNAs. |

| External RNA Controls(e.g., ERCC Spike-Ins) | Known quantities of synthetic RNA transcripts added to each sample. Provide an objective standard to assess technical variation and normalization accuracy [6]. | Especially useful when the "most genes not DE" assumption is violated. |

| Bioanalyzer/TapeStation | Provides quantitative assessment of RNA quality (RIN) via electropherograms. Essential QC to exclude samples with degradation that would bias normalization [4] [10]. | A RIN >7 is a common quality threshold for reliable results. |

| Stranded Library Prep Kits | Preserves information about which DNA strand a transcript originated from. Crucial for accurately quantifying overlapping genes and complex transcription, which affects count-based normalization [4]. | Stranded libraries are now considered best practice for most applications. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers(UMIs) | Short random barcodes that label each original RNA molecule before PCR amplification. Enable computational removal of PCR duplicates, correcting for amplification bias that normalization doesn't address [6]. | Becomes increasingly important with low-input RNA and high PCR cycle numbers. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common RNA-Seq Normalization Issues

FAQ 1: My single-cell RNA-seq analysis is missing key differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between cell types. What could be wrong?

- Problem: A common issue is the use of Count Per 10 Thousand (CP10K) or similar normalization methods that assume all cells have the same transcriptome size (total mRNA content). In reality, transcriptome size can vary significantly between different cell types, and CP10K normalization artificially eliminates this biological variation. This creates a scaling effect that can misrepresent true expression levels and obscure DEGs [11].

- Solution: Consider using normalization methods designed to preserve transcriptome size variation. The CLTS (Count based on Linearized Transcriptome Size) method, part of the ReDeconv toolkit, is one such approach that corrects for this issue and has been shown to improve the identification of DEGs in single-cell data [11].

- Experimental Protocol (Orthogonal Validation): To confirm your DEGs, validate your findings using an orthogonal method, such as quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) on a subset of the identified genes. High correlation between RNA-seq fold-changes (after proper normalization) and qRT-PCR results indicates reliable normalization [12].

FAQ 2: When integrating RNA-seq data from multiple studies for my analysis, the batch effects are overwhelming the biological signals. How can I correct for this?

- Problem: Data from different studies are often generated at different times, locations, and with varying protocols, leading to technical variations (batch effects) that can mask true biological differences [1].

- Solution: Apply batch correction methods after initial within-dataset normalization.

- For known batch factors: Use tools like Limma or ComBat, which employ empirical Bayes methods to adjust for known batch effects (e.g., sequencing date or facility) [1].

- For unknown factors: Implement Surrogate Variable Analysis (SVA) to identify and estimate unknown sources of technical variation [1].

- Key Consideration: Always perform standard within-dataset normalization (e.g., TMM, RLE) to account for sequencing depth and compositional biases before applying cross-dataset batch correction [1].

FAQ 3: My differential expression analysis is biased towards longer genes. How do I account for gene length?

- Problem: Longer genes naturally produce more reads at the same expression level. If not corrected, this length effect can skew within-sample gene expression comparisons and downstream analyses [1] [13].

- Solution: Use within-sample normalization methods that explicitly correct for gene length.

- TPM (Transcripts Per Million) is often preferred over FPKM/RPKM because the sum of all TPMs is consistent across samples, making inter-sample comparisons slightly more straightforward [1].

- Note: For differential expression analysis between samples, TPM data often requires further between-sample normalization (e.g., TMM) to be used effectively [3] [1].

FAQ 4: I am working with cancer RNA-seq data and suspect that copy number alterations (CNAs) are affecting my expression data. How should I normalize it?

- Problem: Standard normalization methods assume a diploid genome. In cancer samples, widespread CNAs alter DNA template numbers, which directly influences RNA transcript abundance. Normalizing without considering CNAs can introduce biological noise and reduce the accuracy of differential expression detection [14].

- Solution: If matched DNA-seq data is available, use an integrated normalization approach. This method uses the DNA copy number information to adjust the RNA-seq read counts, effectively reducing noise from CNA-driven expression changes and improving the detection of true differential expression [14].

Normalization Methods at a Glance

The table below summarizes common normalization methods and the primary sources of variation they address.

Table 1: RNA-Seq Normalization Methods and Their Applications

| Normalization Method | Scope of Application | Corrects for Library Size | Corrects for Gene Length | Corrects for Composition Effects | Key Characteristics & Best Uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM / CP10K [11] [1] | Within-sample | Yes | No | No | Simple scaling by total reads. Suitable for sample quality checks but not for cross-sample or cross-gene comparison. |

| FPKM/RPKM [1] | Within-sample | Yes | Yes | No | Enables within-sample gene comparison. Not ideal for between-sample comparison due to varying distribution sums. |

| TPM [1] | Within-sample | Yes | Yes | No | Improved version of FPKM; sum of TPMs is constant across samples, making it more comparable. |

| TMM [3] [1] [12] | Between-sample | Yes | No | Yes (partial) | Robust against highly differentially expressed genes. Often used for differential expression analysis. |

| RLE (e.g., DESeq2) [3] [12] | Between-sample | Yes | No | Yes (partial) | Assumes most genes are not DE. Works well for differential expression analysis. |

| CLTS [11] | Within-sample (scRNA-seq) | Yes | No | Yes (Transcriptome Size) | Specifically designed for single-cell data to preserve biological variation in transcriptome size across cell types. |

| GC-Content Normalization (e.g., CQN) [13] | Within- and Between-sample | Yes | Yes | Yes (GC-content) | Corrects for sample-specific GC-content biases which can confound fold-change estimates. |

| Quantile [1] [12] | Between-sample | - | - | - | Makes the distribution of expression values identical across samples. Assumes most technical variation is global. |

| Integrated (CNA-aware) [14] | Within- and Between-sample | Yes | Optional | Yes (CNA effects) | Uses matched DNA-seq data to remove variation due to copy number alterations. Ideal for cancer genomics. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Normalization Methods Using qRT-PCR Validation

This protocol is based on a study that compared normalization methods by validating RNA-seq results with quantitative RT-PCR [12].

- Sample Preparation: Obtain RNA samples (e.g., from the MAQC project for benchmark data).

- RNA Sequencing: Sequence the libraries on your chosen platform (e.g., Illumina), generating raw FASTQ files.

- Read Mapping & Quantification: Map the sequencing reads to a reference genome (e.g., using tools like STAR or HISAT2) and generate raw gene-level read counts.

- Data Normalization: Apply the normalization methods you wish to evaluate (e.g., TMM, RLE, RPKM, TPM) to the raw count data.

- Differential Expression Analysis: Perform differential expression analysis on the normalized data for each method.

- Orthogonal Validation: Compare the gene expression fold-changes from each normalized RNA-seq dataset with the expression values obtained from qRT-PCR for the same set of genes.

- Evaluation: Calculate the Spearman correlation coefficient between the RNA-seq results and the qRT-PCR results for each normalization method. The method yielding the highest correlation provides the most accurate representation of biological truth [12].

Protocol 2: Creating Condition-Specific Metabolic Models from RNA-seq Data

This protocol outlines how to use normalized RNA-seq data to build genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), a process highly sensitive to the choice of normalization [3].

- Data Acquisition & Preprocessing: Download RNA-seq data from a relevant cohort (e.g., TCGA for cancer). Perform quality control (e.g., with FastQC) and adapter trimming (e.g., with Trimmomatic).

- Normalization: Normalize the raw read counts using various methods. The benchmark suggests that RLE, TMM, and GeTMM produce models with lower variability and higher accuracy for disease gene capture compared to TPM and FPKM [3].

- Covariate Adjustment: Adjust the normalized data for known clinical covariates (e.g., age, gender, batch) using linear models to remove potential confounding effects.

- Model Building: Map the normalized and adjusted gene expression data onto a generic human metabolic model (e.g., Recon3D) using algorithms like iMAT (Integrative Metabolic Analysis Tool) or INIT (Integrative Network Inference for Tissues) to build condition-specific GEMs.

- Model Analysis & Validation: Compare the resulting models (e.g., the number of active reactions, affected pathways) against known disease-associated metabolic changes or independent metabolomics data to assess biological relevance [3].

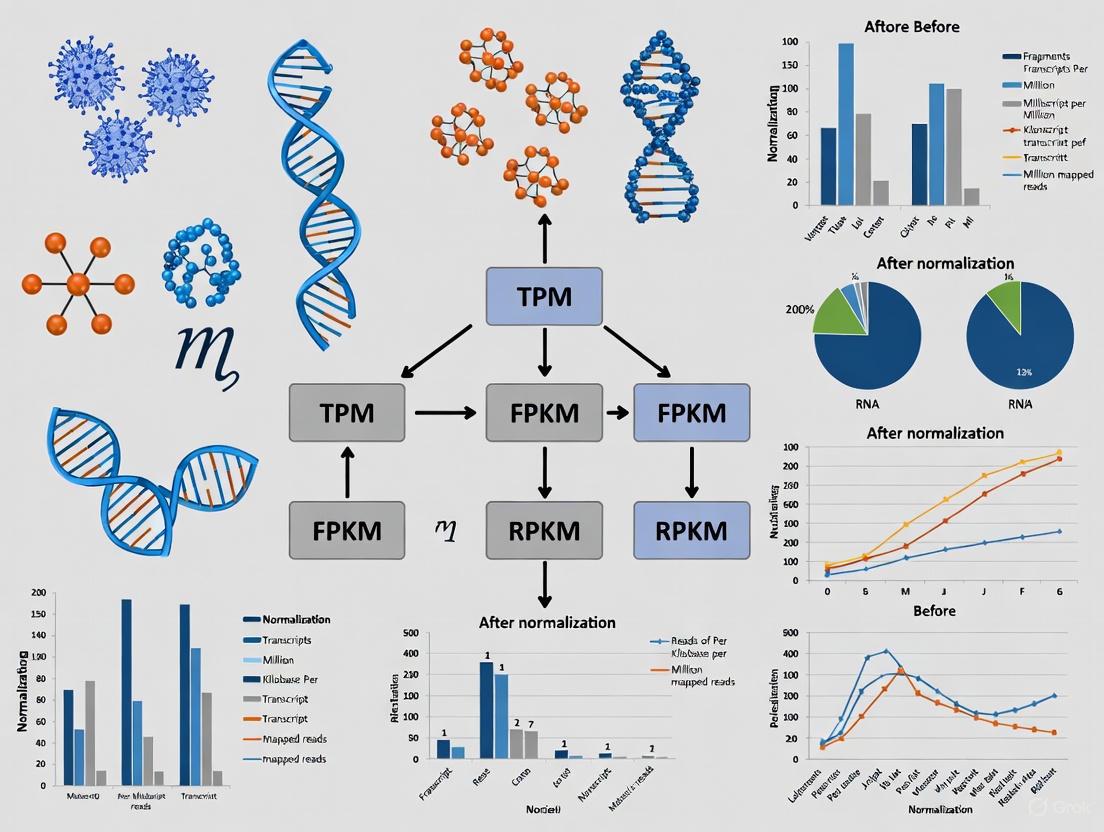

Workflow and Decision Diagrams

The diagram below illustrates a robust RNA-seq data analysis pipeline that incorporates steps to handle key sources of variation.

Diagram 1: A robust RNA-seq analysis pipeline integrating key normalization stages.

The following decision guide helps select the appropriate normalization method based on your experimental goals.

Diagram 2: A guide for selecting RNA-seq normalization methods based on analysis goals.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software Tools for RNA-Seq Normalization

| Tool / Resource Name | Function in Normalization / Analysis | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| ReDeconv [11] | scRNA-seq normalization and bulk deconvolution | Corrects for transcriptome size variation using the CLTS method. |

| edgeR [3] [12] [15] | Differential expression analysis | Implements the TMM normalization method. |

| DESeq2 [3] [12] [15] | Differential expression analysis | Uses the RLE (Relative Log Expression) normalization method. |

| Salmon [15] | Transcript quantification | Provides fast and accurate transcript-level abundance estimates. |

| RSEM [12] | Transcript quantification | Estimates gene and isoform abundances using an expectation-maximization algorithm. |

| EDASeq [13] | Exploratory data analysis and normalization | Provides methods for within-lane GC-content normalization. |

| Limma [1] [15] | Differential expression and batch correction | Contains functions for removing batch effects using empirical Bayes methods. |

| ComBat [1] | Batch effect correction | Adjusts for batch effects in high-throughput data using an empirical Bayes framework. |

| Seurat / Scanpy [11] | Single-cell RNA-seq analysis | Toolkits that commonly use CP10K normalization by default; may require advanced settings for transcriptome-size-aware normalization. |

A Framework for Testing Your Methodological Assumptions

Selecting the right analytical method is not a guessing game; it should be a deliberate process driven by evidence. The following framework provides a systematic way to identify and validate your riskiest methodological assumptions before you commit to a full analysis. This process consists of three phases [16]:

- Phase 1: Identify & Prioritize: Brainstorm and rank your assumptions based on their potential impact on your results and your current confidence in them. The riskiest assumptions are those with High Impact and Low Confidence [16].

- Phase 2: Design & Run Minimal Tests: For your top-priority assumption, design the fastest, cheapest experiment that can generate reliable data. This could be a small-scale pilot analysis or testing your method on a publicly available benchmark dataset [16] [17].

- Phase 3: Learn & Adapt: Analyze the findings from your test. Decide whether the evidence validates your assumption (Persevere) or invalidates it (Pivot and choose a different method), then define your next steps [16].

The diagram below illustrates this iterative process.

Selecting RNA-Seq Normalization Methods: A Decision Guide

A core challenge in bioinformatics is selecting a normalization method for RNA-Seq data. Your choice is highly dependent on your experimental conditions and analytical goals. Making an incorrect assumption about which method to use can introduce significant bias and lead to false conclusions [5] [3].

The table below summarizes the key normalization methods and their suitability for different experimental conditions, particularly for Differential Gene Expression (DGE) analysis.

| Method | Core Principle | Suitable for DGE? | Key Assumptions & Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) [3] [12] | Trims extreme log fold-changes and gene counts to calculate a scaling factor. | Yes [3] | Most genes are not differentially expressed. Best for between-sample comparisons with balanced library composition [3]. |

| RLE (Relative Log Expression) [3] | Calculates a size factor as the median of the ratio of counts to a reference sample. | Yes [3] | Similar assumption to TMM. Robust for between-sample comparisons and is the default in DESeq2 [5] [3]. |

| GeTMM (Gene-length corrected TMM) [3] | Combines TMM normalization with gene length correction. | Yes (Benchmarked for metabolic modeling) [3] | Useful when both between-sample comparison and gene length correction are required [3]. |

| TPM (Transcripts per Million) [5] [3] | Normalizes for both sequencing depth and gene length, scaling to 1 million. | No (Not recommended for DGE) [3] | A within-sample method. Good for comparing expression across different genes within the same sample, but can be problematic for comparing the same gene across samples due to library composition effects [5] [3]. |

| FPKM (Fragments per Kilobase Million) [5] [3] | Similar to TPM but the order of operations differs. Comparable to RPKM for single-end reads. | No (Not recommended for DGE) [3] | Same as TPM. A within-sample method with similar limitations for cross-sample DGE analysis [3]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: RNA-Seq Normalization FAQs

Q1: My RNA-Seq data has known covariates like age, gender, or batch effects. How does this affect my normalization choice? A: Covariates can significantly impact your results. A recent benchmark study on Alzheimer's and lung cancer data showed that applying covariate adjustment (e.g., using linear models to account for age, gender) to normalized data improved the accuracy of downstream metabolic models for all methods tested [3]. It is a best practice to identify potential covariates during experimental design and account for them statistically after normalization.

Q2: I need to build condition-specific metabolic models using algorithms like iMAT or INIT. Which normalization method should I use? A: For this specific application, benchmark results strongly favor between-sample normalization methods. When mapping RNA-Seq data to genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), RLE, TMM, and GeTMM produced models with lower variability and more accurately captured disease-associated genes compared to TPM and FPKM [3].

Q3: Why are TPM and FPKM not recommended for direct differential expression analysis between samples? A: While TPM and FPKM are excellent for within-sample comparisons, they are sensitive to differences in library composition across samples [5] [3]. If a few genes are extremely highly expressed in one sample, they consume a large fraction of the total counts. This skews the normalized values for other genes when scaled to a million, making cross-sample comparisons less reliable. Methods like TMM and RLE are specifically designed to be robust to such composition biases [5].

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking Normalization Methods

To empirically validate which normalization method performs best for your specific dataset, you can run a comparative benchmark following this workflow. This is an effective way to test the assumption that your chosen method is optimal.

Detailed Methodology [3] [12]:

- Input Preparation: Start with a raw count matrix, which is the output from alignment and quantification tools like STAR/featureCounts or pseudoaligners like Salmon [5].

- Normalization: Apply the normalization methods you wish to compare (e.g., TMM, RLE, TPM) to the same raw count matrix. This can typically be done within R/Bioconductor packages like

edgeR(for TMM) andDESeq2(for RLE). - Downstream Analysis: Use the normalized data to perform the analysis central to your goal, such as:

- Differential Gene Expression (DGE): Identify differentially expressed genes between conditions.

- Metabolic Model Building: Reconstruct condition-specific metabolic models using an algorithm like iMAT or INIT.

- Validation Against Benchmark:

- Performance Evaluation: Quantify performance using metrics like:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

The following table lists essential software tools and their primary functions in RNA-Seq data normalization and analysis.

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Utility |

|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 [5] [3] | Differential expression analysis | Implements the RLE normalization method and provides a robust statistical framework for identifying differentially expressed genes. |

| edgeR [3] [12] | Differential expression analysis | Implements the TMM normalization method and uses a negative binomial model to assess differential expression. |

| RSEM [12] | Transcript abundance estimation | Uses an expectation-maximization algorithm to estimate gene and isoform abundances, which can then be normalized. |

| Salmon [5] | Transcript abundance estimation | A fast and accurate tool for transcript quantification that uses a "lightweight" alignment method, often used as input for tools like DESeq2. |

| FastQC [5] | Quality Control | Provides an initial report on raw sequence data quality, highlighting potential issues like adapter contamination or low-quality bases. |

| SAMtools [5] | Post-alignment processing | Used for processing and manipulating aligned sequence files (BAM), which is a prerequisite for generating count matrices. |

Why is normalization crucial in RNA-seq analysis?

Answer: Normalization is an essential step that adjusts raw RNA-seq data to account for technical variations, ensuring that differences in read counts reflect true biological changes rather than experimental artifacts. Without proper normalization, factors like sequencing depth (total number of reads per sample), gene length, and sample-to-sample variability can mask actual biological effects and lead to incorrect conclusions, such as inflated false positives in differential expression analysis [1] [18].

The primary goal is to transform raw read counts into meaningful measures of gene expression that accurately represent the absolute quantity of mRNA per cell [18]. Correct normalization ensures that:

- Non-differentially expressed genes have, on average, the same normalized counts across conditions.

- Differentially expressed genes have normalized count differences that faithfully represent the true differences in mRNA/cell [18].

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the core difference between within-sample and between-sample normalization?

The distinction lies in what comparisons the normalization enables.

| Normalization Type | Purpose | Common Methods | Suitable For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Within-Sample | Enables comparison of expression between different genes within the same sample. Corrects for gene length and sequencing depth [1]. | FPKM, RPKM, TPM [1] [19] | Comparing the relative abundance of genes A and B in a single sample. |

| Between-Sample | Enables comparison of the same gene across different samples or conditions. Corrects for technical variations like library size and composition [1] [18]. | TMM, RLE (used in DESeq2), GeTMM [3] | Identifying if gene A is differentially expressed between a treatment and control group. |

Note: While TPM is a within-sample measure, it is often mistakenly used for cross-sample comparisons. For this purpose, between-sample methods like TMM or RLE are generally more robust [19].

2. My data shows a global shift in expression in one condition. Which normalization method should I use?

Global shifts, where most or all genes are up- or down-regulated in one condition, violate the key assumption of many methods (that most genes are not differentially expressed) [18]. In such cases:

- Standard methods like TMM or RLE may perform poorly, as they can incorrectly normalize true biological signals [18].

- Consider per-gene normalization methods like Med-pgQ2 or UQ-pgQ2, which have been shown to improve specificity and control the false discovery rate (FDR) in datasets with widespread expression changes [20].

3. For building condition-specific metabolic models, which normalization method yields the most accurate results?

A 2024 benchmark study on human genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) found that between-sample normalization methods (RLE, TMM, GeTMM) are superior to within-sample methods (TPM, FPKM) for this purpose [3].

The study demonstrated that models built with RLE, TMM, or GeTMM normalized data:

- Exhibited lower variability in the number of active reactions between samples.

- More accurately captured disease-associated genes (e.g., ~80% accuracy for Alzheimer's disease).

- Helped reduce false positive predictions in the metabolic models [3].

4. I have replicated samples from the same model. Which quantification measure best groups these replicates together?

A comparative study on Patient-Derived Xenograft (PDX) models, which have inherent biological variability, provided compelling evidence for using normalized counts [19]. The study evaluated three measures:

| Quantification Measure | Replicate Grouping Performance | Median Coefficient of Variation | Intraclass Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normalized Counts | Most accurately grouped replicate samples [19] | Lowest [19] | Highest [19] |

| TPM | Less accurate than normalized counts [19] | Higher than normalized counts [19] | Lower than normalized counts [19] |

| FPKM | Less accurate than normalized counts [19] | Higher than normalized counts [19] | Lower than normalized counts [19] |

This indicates that for downstream analyses like clustering and cross-sample comparison, normalized counts (e.g., from DESeq2 or edgeR) are a better choice than TPM or FPKM [19].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Scenarios

Scenario 1: Inconsistent results after integrating multiple RNA-seq datasets.

- Problem: You are combining data from different studies, and technical batch effects (e.g., different sequencing facilities or dates) are the dominant source of variation, masking biological differences.

- Solution: Apply batch correction methods after initial between-sample normalization.

- Tools: Use algorithms like Limma or ComBat, which employ empirical Bayes statistics to adjust for known batches [1].

- Workflow: First, normalize your data within the dataset using a method like TMM or RLE. Then, apply the batch correction tool, specifying the known sources of variation (e.g., sequencing center) [1].

- For unknown factors: Surrogate Variable Analysis (SVA) can help identify and estimate unknown sources of variation [1].

Scenario 2: High variability in metabolic model predictions when using TPM/FPKM.

- Problem: When mapping RNA-seq data to genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) using algorithms like iMAT or INIT, the content and predictions of the models are unstable and highly variable across samples.

- Solution: Switch from within-sample to between-sample normalization.

- Recommended Methods: RLE (from DESeq2), TMM (from edgeR), or GeTMM [3].

- Rationale: These methods correct for library composition differences between samples, leading to more consistent model sizes (number of active reactions) and improved accuracy in identifying disease-associated metabolic genes [3].

Scenario 3: Suspected poor performance due to a few highly expressed genes.

- Problem: A small number of genes account for a large proportion of the total reads in one condition, which can create the false appearance that other, non-differentially expressed genes are down-regulated [18].

- Solution: Use a robust between-sample method.

- TMM is specifically designed for this. It calculates scaling factors by first trimming (removing) the most extreme genes (both in terms of fold-change and expression intensity) before calculating the mean to be used for normalization, making it resistant to the influence of highly expressed genes [1] [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

The following table details essential computational tools and methods used in RNA-seq normalization research.

| Item | Function & Application | Key Context from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) | A between-sample normalization method that calculates a scaling factor relative to a reference sample, robust to highly expressed genes [1]. | Consistently performs well in differential expression analysis and metabolic model building [3] [19]. |

| Relative Log Expression (RLE) | The default normalization method in DESeq2, which calculates scaling factors as the median of the ratio of counts to a geometric mean reference [3]. | Shows high accuracy and low variability in generating personalized metabolic models [3]. |

| Gene length-corrected TMM (GeTMM) | A hybrid method combining gene-length correction (like TPM) with the between-sample robustness of TMM [1]. | Effectively reconciles within- and between-sample needs, performing on par with TMM and RLE [3]. |

| Housekeeping Gene Set (HKg) | A set of constitutively expressed genes used for experimental validation of expression signals [21]. | Used to measure the precision and accuracy of RNA-seq pipelines by qRT-PCR [21]. |

| qRT-PCR with Global Median Normalization | The "gold standard" experimental method for validating RNA-seq gene expression results [21]. | Used to benchmark the performance of 192 different RNA-seq analysis pipelines [21]. |

| Patient-Derived Xenograft (PDX) Models | Cancer models that recapitulate patient tumor biology, used for pre-clinical research [19]. | Provide a biologically variable test system for comparing quantification measures [19]. |

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking Normalization Methods

The following workflow visualizes a comprehensive approach for evaluating RNA-seq normalization methods, synthesizing methodologies from several key studies [21] [3] [19].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Dataset Selection:

- Use a dataset with biological replicates (samples from the same model or condition) to assess technical vs. biological variation [19]. Studies often use cell lines or patient-derived models (PDXs) with multiple replicates per condition [21] [19].

- For a more rigorous benchmark, include a dataset with a known "gold standard" set of differentially expressed genes, such as those from the Microarray Quality Control Project (MAQC) [20].

Data Pre-processing:

Application of Normalization Methods:

Downstream Analysis:

- Use the normalized data to perform key analyses like differential expression testing or building condition-specific metabolic models (e.g., using iMAT or INIT algorithms) [3].

Performance Validation:

- Computational Metrics: Calculate metrics like Coefficient of Variation (CV) and Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) to measure reproducibility across replicates [19]. Use Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) and False Discovery Rate (FDR) to assess accuracy against a known standard [20].

- Experimental Validation: Validate key findings using qRT-PCR on a set of housekeeping and target genes, using a robust normalization method like global median normalization [21].

Comparison and Conclusion:

- Synthesize all metrics to determine which normalization method(s) provide the most precise, accurate, and biologically meaningful results for your specific experimental context.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common experimental design mistake in RNA-seq studies? The most common mistake is using an insufficient number of biological replicates. With only two replicates, the ability to estimate biological variability and control false discovery rates is greatly reduced. A single replicate per condition does not allow for robust statistical inference. While three replicates are often considered the minimum standard, more are needed when biological variability within groups is high [5] [6].

My negative control sample shows high expression of metabolic genes. Which normalization method should I suspect? Suspect within-sample normalization methods like TPM and FPKM. These methods do not correct for library composition. If a few genes are extremely highly expressed in one sample, they consume a large fraction of the sequencing depth, making all other genes in that sample appear under-expressed in comparison. This can make negative controls look artificially active [5] [3].

After normalization, my treatment and control groups separate by batch, not by condition. What went wrong? This indicates a strong batch effect, a major source of technical variation. This often occurs when samples are not properly randomized during library preparation and sequencing. To mitigate this, use indexing and multiplex samples across all sequencing lanes. If this is impossible, use a blocking design that includes some samples from each experimental group on each lane [6].

I used a between-sample method, but my results miss known true positives. Is this expected? Yes, this is a known trade-off. Benchmark studies show that between-sample normalization methods like RLE (used by DESeq2) and TMM (used by edgeR) reduce false positive predictions but can do so at the expense of missing some true positive genes. If your priority is to minimize false positives, this is an acceptable outcome [3].

What is a simple first check for library composition bias? A simple check is to compare the total number of reads between your samples. If one sample has a drastically higher total count, it can dominate the analysis. Between-sample normalization methods are designed to correct for this, while simple methods like CPM are not [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Correcting for Violated Normalization Assumptions

A core assumption of statistical methods in tools like DESeq2 and edgeR is that most genes are not differentially expressed. Global expression shifts between conditions can violate this assumption.

Symptoms:

- An unusually high number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs).

- Poor separation of samples by experimental condition in a PCA plot, often clustering by lab batch or sequencing date instead.

- Negative control samples do not cluster together.

Step-by-Step Resolution:

- Confirm the Problem: Generate a PCA plot of your data. If samples cluster by a technical factor (like batch) rather than the biological condition, a batch effect is likely [6].

- Recalculate Size Factors: If a global shift is confirmed, inform your normalization tool. In DESeq2, you can experiment with different

typeof normalization in theestimateSizeFactorsfunction. - Apply Covariate Adjustment: If your dataset contains known technical covariates (e.g., sequencing lane, researcher) or biological covariates (e.g., patient age, sex), include them in your statistical model. For example, in DESeq2, you would use a design formula like

~ batch + condition[3]. - Consider Alternative Methods: In extreme cases, explore normalization methods that are more robust to global shifts or the use of spike-in controls.

Guide 2: Resolving Issues from Insufficient Sequencing Depth

Symptoms:

- Low correlation between technical or biological replicates.

- Inability to detect differential expression in low-abundance transcripts.

- Saturation plots (e.g., from tools like

Scotty) show that new genes are still being discovered even at your current depth.

Step-by-Step Resolution:

- Quality Control: Use tools like FastQC and MultiQC to check your raw sequencing depth and quality scores [5].

- Assess Saturation: Use a saturation analysis tool to determine if your current depth is adequate for your goals.

- Increase Depth or Replicates: If depth is insufficient, you may need to sequence your existing libraries more deeply. However, if your budget is limited, adding more biological replicates often provides greater statistical power than increasing sequencing depth for the same cost [6].

- Re-normalize and Re-analyze: After obtaining additional data, re-run your entire preprocessing and normalization pipeline to ensure consistency.

Normalization Method Benchmarking Data

The table below summarizes a benchmark of RNA-seq normalization methods based on their performance when used to create condition-specific metabolic models with the iMAT algorithm. This illustrates how the choice of method affects downstream biological conclusions [3].

- Dataset 1: Alzheimer's disease (ROSMAP) brain tissue data.

- Dataset 2: Lung adenocarcinoma (TCGA) data.

| Normalization Method | Type | Variability in Model Size (Number of Active Reactions) | Accuracy in Capturing Disease Genes (AD) | Key Assumption |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMM | Between-sample | Low variability | ~0.80 | Most genes are not DE |

| RLE (DESeq2) | Between-sample | Low variability | ~0.80 | Most genes are not DE |

| GeTMM | Between-sample | Low variability | ~0.80 | Most genes are not DE |

| TPM | Within-sample | High variability | Lower than between-sample methods | N/A |

| FPKM | Within-sample | High variability | Lower than between-sample methods | N/A |

Conclusion from Data: Between-sample normalization methods (TMM, RLE, GeTMM) produce more stable and reliable results for downstream integration with metabolic models than within-sample methods (TPM, FPKM). Covariate adjustment (for age, gender, etc.) further increased accuracy for all methods [3].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Robust RNA-seq Normalization Workflow

This protocol uses a standard bioinformatics pipeline for differential expression analysis.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| FastQC | Performs initial quality control on raw FASTQ files, identifying issues with adapter contamination, base quality, and sequence duplication [5]. |

| Trimmomatic | Removes adapter sequences and trims low-quality bases from reads, cleaning the data for more accurate alignment [5]. |

| HISAT2/STAR | Aligns (maps) the cleaned sequencing reads to a reference genome. STAR is more accurate for splice-aware alignment [5] [6]. |

| featureCounts | Quantifies the number of reads mapped to each gene, generating the raw count matrix used for statistical testing [5]. |

| DESeq2/edgeR | Performs normalization and statistical testing for differential expression. DESeq2 uses the RLE method, while edgeR uses TMM [5] [3]. |

Methodology:

- Quality Control & Trimming: Run FastQC on all raw FASTQ files. Use Trimmomatic to trim adapters and low-quality bases based on the QC report [5].

- Read Alignment: Align the trimmed reads to the appropriate reference genome (e.g., GRCh38 for human) using a splice-aware aligner like STAR [5] [6].

- Post-Alignment QC & Quantification: Use tools like SAMtools and Qualimap to check alignment quality. Then, use featureCounts to generate a raw count matrix [5].

- Normalization & Differential Expression: Import the count matrix into R/Bioconductor. Use DESeq2 or edgeR to normalize the data (correcting for library composition) and perform statistical testing for differential expression [5] [3].

Protocol 2: Validating Findings with Covariate Adjustment

This protocol adds a critical step to account for known sources of variation.

Methodology:

- Identify Covariates: Before analysis, identify potential technical (e.g., sequencing batch, lane, RIN score) and biological (e.g., patient age, sex, BMI) covariates [3] [6].

- Incorporate into Model: Include these covariates in the statistical design formula of your analysis tool. In DESeq2, this is done when creating the

DESeqDataSetobject (e.g.,design = ~ age + sex + condition) [3]. - Evaluate Model Improvement: Compare the results, such as the number of DEGs or the sample clustering in a PCA plot, with and without covariate adjustment. Improved separation by condition in the PCA plot indicates successful adjustment.

Workflow and Decision Diagrams

RNA-seq Normalization Decision Guide

Robust Experimental Design Workflow

A Practical Guide to RNA-seq Normalization Methods: From Global Scaling to Machine Learning Approaches

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core purpose of library size normalization in RNA-seq data analysis? Library size normalization is an essential step to correct for differences in sequencing depth between samples. Without it, a gene in a sample sequenced to a greater depth would, on average, have a higher count than the same gene in a sample sequenced to a lower depth, even if its true expression level is unchanged. Normalization adjusts for this by scaling counts to make them comparable across samples, ensuring that technical variations do not obscure true biological differences [22] [23].

Q2: When should I use TMM, RLE, or UQ normalization? The choice depends on your data's characteristics and the analysis goals. The Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) is particularly effective when the RNA composition of the samples is different, for instance, when a large subset of genes is uniquely expressed in one condition. It is robust to such imbalances and is often the recommended default for differential expression analysis [22] [23]. The Relative Log Expression (RLE) method performs well under the assumption that most genes are not differentially expressed and is a strong choice for balanced designs [24] [23]. The Upper Quartile (UQ) method can be a good alternative but may be more sensitive to outliers in highly expressed genes [24] [23].

Q3: Why is simple Total Count scaling often considered insufficient? Scaling by total count (also known as counts per million) assumes that the total RNA output is constant across all samples. However, this assumption is frequently violated in real experiments. If a small number of genes are extremely highly expressed in one condition, they can consume a large proportion of the sequencing reads. This artificially deflates the counts for all other genes in that sample, making them appear down-regulated compared to other samples. Methods like TMM and RLE are designed to be robust to such composition biases [22].

Q4: How does the choice of normalization method impact downstream analysis beyond differential expression? The normalization method can significantly influence the results of exploratory analyses like Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Different normalization techniques alter the correlation patterns within the data, which can affect the complexity of the PCA model, the clustering of samples in the score plot, and the ranking of genes that contribute most to the variance. Consequently, the biological interpretation of the data can vary depending on the normalization method chosen [25].

Q5: Are there new developments that combine these methods? Yes, hybrid methods are being developed to improve performance. For example, the UQ-pgQ2 method is a two-step normalization that first applies a per-sample upper-quartile (UQ) global scaling, followed by a per-gene median (Q2) scaling. Studies have shown that this approach, when combined with specific statistical tests in differential expression analysis, can help better control false positives, especially when sample sizes are small [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inflated False Discovery Rate (FDR) in Differential Expression Analysis

Problem: Your analysis detects a very large number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs), and you suspect many may be false positives.

Solutions:

- Check Data Assumptions: TMM and UQ normalizations can sometimes be too liberal, leading to an inflated FDR, particularly with small sample sizes. If your sample size is small (e.g., n<5 per group), consider using the UQ-pgQ2 method combined with an exact test or a quasi-likelihood (QL) F-test, which has been shown to improve false positive control [24].

- Re-normalize and Re-test: Apply a different normalization method. If you started with UQ, try TMM or RLE. Re-run the differential expression analysis and compare the number of significant DEGs. A consistent result across methods increases confidence.

- Account for Latent Factors: Technical artifacts not corrected by library size normalization can inflate FDR. Use across-sample normalization methods like SVA (Surrogate Variable Analysis) or RUV (Remove Unwanted Variation) in conjunction with library size normalization to account for these hidden factors [23].

Issue 2: Poor Sample Separation in PCA or Clustering

Problem: Biological replicates from the same group do not cluster together in an unsupervised analysis.

Solutions:

- Verify Normalization Impact: Ensure that the normalization has been correctly applied. Plot the data before and after normalization to see if the normalization reduces the influence of extreme samples.

- Investigate Sample-Specific Biases: Poor clustering might be due to strong batch effects or RNA composition biases that library size normalization alone cannot fix.

Issue 3: Disagreement Between Normalization Methods

Problem: The list of significant DEGs changes dramatically when you use TMM versus RLE normalization.

Solutions:

- Benchmark with Simulated Data: If possible, use spike-in RNAs or simulated data where the true differential expression status is known. This allows you to evaluate which normalization method performs best for your specific data type in terms of sensitivity and specificity [24] [26].

- Prioritize Consistency: Focus on the genes that are consistently identified as DEGs across multiple reliable normalization methods (e.g., TMM and RLE). These genes are more likely to be true positives.

- Check Data Quality: Inspect your raw count data. A high discrepancy between methods can sometimes indicate underlying data quality issues, such as a few samples with extremely high or low library sizes, or a severe global imbalance in gene expression. Re-run quality control checks.

Comparison of Library Size Normalization Methods

The following table summarizes the key features, mechanisms, and recommended use cases for the four primary library size-based normalization methods.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Library Size Normalization Methods

| Method | Full Name & Key Citation | Core Mechanism | Key Assumption | Best For/Strengths | Potential Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMM | Trimmed Mean of M-values [22] [23] | Computes a scaling factor as a weighted mean of log-fold-changes (M-values) between a test sample and a reference, after trimming extreme genes. | The majority of genes are not differentially expressed, and the expression of the remaining genes is symmetric up- and down-regulation. | Data with different RNA compositions between groups; robust to outliers. | Performance may decrease if the majority-of-genes assumption is severely violated. |

| RLE | Relative Log Expression [24] [23] | Calculates a scaling factor as the median of the ratio of a gene's counts to its geometric mean across all samples. | The majority of genes are not differentially expressed. | Balanced experimental designs where RNA composition is similar between groups. | Can be too conservative, potentially leading to lower power to detect DEGs. |

| UQ | Upper Quartile [24] [23] | Scales counts using the sample's 75th percentile (upper quartile) of counts, excluding genes with zero counts. | The upper quartile of counts is representative of the sample's sequencing depth and is stable across samples. | A simple and fast method that is an alternative to total count. | Sensitive to changes in a few highly expressed genes which can influence the upper quartile. |

| Total Count | Total Count (TC) or Counts Per Million (CPM) [23] | Scales each sample's counts by its total library size, often expressed as counts per million (CPM). | The total RNA output (or total number of RNA molecules) is constant across all samples. | Simple and intuitive calculation. | Fails when a few genes are extremely abundant in one condition, skewing the counts for all others (RNA composition bias) [22]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Implementing Normalization for Differential Expression Analysis with edgeR/DESeq2

This protocol outlines the standard workflow for incorporating TMM (edgeR) or RLE (DESeq2) normalization into a differential expression analysis.

I. Research Reagent Solutions

- RNA-seq Count Data: A matrix where rows represent genes and columns represent samples.

- R/Bioconductor Environment: R programming language with Bioconductor packages installed.

- Analysis Packages:

edgeR(for TMM) orDESeq2(for RLE) and associated dependencies. - Sample Metadata: A table describing the experimental design and group assignments for each sample.

II. Methodology

- Data Loading and Pre-filtering:

- Load the raw count matrix and sample metadata into R.

- Perform initial pre-filtering to remove genes with very low counts across all samples (e.g., genes with counts per million (CPM) < 1 in at least

nsamples, wherenis the size of the smallest group). This step improves efficiency and reduces multiple testing burden.

Normalization and Model Fitting:

- For TMM with edgeR:

- Create a

DGEListobject from the count data and metadata. - Apply the

calcNormFactorsfunction withmethod = "TMM"to calculate normalization factors. This function does not change the raw counts but stores a scaling factor for each sample. - Estimate common, trended, and tagwise dispersions using

estimateDisp. - Fit a generalized linear model and test for differential expression using an exact test, quasi-likelihood (QL) F-test, or likelihood ratio test.

- Create a

- For RLE with DESeq2:

- Create a

DESeqDataSetfrom the count data and metadata. - Execute the core analysis with the single

DESeqfunction. This function performs an internal normalization using the RLE method (to estimate size factors), estimates dispersions, and fits models. - Extract results using the

resultsfunction.

- Create a

- For TMM with edgeR:

Result Interpretation:

- Examine the list of significant DEGs, paying attention to the log2 fold changes and adjusted p-values.

- Perform diagnostic checks, such as examining dispersion plots or PCA plots, to assess the quality of the model fit and the effect of normalization.

The logical flow of this protocol, including the parallel paths for edgeR and DESeq2, is visualized below.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Normalization Effectiveness Using PCA

This protocol describes how to assess the impact of different normalization methods on the data structure using Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

I. Research Reagent Solutions

- Normalized Data: Count data normalized using multiple methods (e.g., TMM, RLE, UQ).

- R/Bioconductor Environment: R with packages like

limma,edgeR, andggplot2. - Sample Metadata: A table with group and batch information for sample coloring in plots.

II. Methodology

- Apply Multiple Normalizations:

- Start with the same raw, pre-filtered count matrix.

- Apply different library size normalization methods (TMM, RLE, UQ) to create multiple normalized datasets. For example, use

edgeR'scpm()function with differentnormalization.methodarguments to get TMM and UQ scaled data, and useDESeq2'svarianceStabilizingTransformationon the RLE-normalized data.

Perform PCA:

- For each normalized dataset, perform PCA. This is typically done on the log-transformed normalized counts (e.g.,

log2(CPM + k)wherekis a small constant to avoid log(0)). - Extract the principal components (PCs) and the proportion of variance explained by each.

- For each normalized dataset, perform PCA. This is typically done on the log-transformed normalized counts (e.g.,

Visualize and Interpret:

- Create PCA score plots (PC1 vs. PC2) for each normalization method. Color the points by experimental group and, if applicable, by batch.

- Evaluate the plots:

- Clustering: Do biological replicates from the same group cluster together?

- Separation: Is there clear separation between the experimental groups of interest?

- Batch Effects: Does the variance associated with batch (if known) decrease after a particular normalization?

- Compare the gene loadings (which genes contribute most to the PCs) across different normalization methods. This can reveal how normalization alters the biological interpretation of the major axes of variation [25].

The workflow for this comparative analysis is straightforward, as shown below.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is within-sample normalization and why is it needed? Within-sample normalization allows you to compare the expression levels of different genes within the same single sample. It corrects for two key technical biases: gene length and sequencing depth. Without this, a longer gene would always appear more highly expressed than a shorter one, even if their true biological abundance is identical [1] [2].

2. What's the fundamental difference between RPKM/FPKM and TPM? The core difference lies in the order of operations during calculation [27] [28]. This results in a key practical property: for a given sample, the sum of all TPM values is always one million, whereas the sum of RPKM or FPKM values can vary from sample to sample [27]. This makes TPM a more reliable measure for comparing the relative proportion of a transcript across different samples.

3. I have TPM values. Can I use them for statistical tests to find differentially expressed genes? No. While TPM is an excellent metric for comparing gene expression within a sample or for visualizations, it is not suitable for direct use in differential expression analysis tools like DESeq2 or edgeR [1] [2]. These tools require raw or normalized counts and use their own sophisticated between-sample normalization methods (like DESeq2's "median-of-ratios" or edgeR's "TMM") which account for library composition and variance structure across multiple samples [5] [19] [3].

4. When should I use RPKM/FPKM versus TPM? TPM is now widely considered the superior metric [19] [29]. Its consistent sum across samples allows for more intuitive cross-sample comparisons of a gene's relative abundance. Due to this advantage, TPM has largely superseded RPKM/FPKM in modern RNA-seq analysis.

5. Can I directly compare TPM values from different sequencing protocols? Proceed with extreme caution. TPM values represent a transcript's proportion within the sequenced population. If you use different protocols (e.g., poly(A) selection vs. rRNA depletion), the composition of the sequenced RNA population changes dramatically. In such cases, a gene's TPM value can be vastly different even for the same biological sample, making direct comparisons invalid [30].

Comparison of Normalization Methods

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of RPKM, FPKM, and TPM.

| Feature | RPKM/FPKM | TPM |

|---|---|---|

| Full Name | Reads/Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads [27] [19] | Transcripts Per Million [27] [19] |

| Primary Use | Within-sample gene-level comparison [1] | Within-sample gene-level comparison; better for cross-sample comparison of proportions [27] [1] |

| Corrects for Sequencing Depth | Yes | Yes |

| Corrects for Gene Length | Yes | Yes |

| Order of Normalization | 1. Normalize for sequencing depth (RPM)2. Normalize for gene length [27] [28] | 1. Normalize for gene length (RPK)2. Normalize for sequencing depth [27] [28] |

| Sum of Normalized Values | Varies from sample to sample [27] | Constant (1,000,000) across all samples [27] |

| Interpretation | Reads/fragments per kilobase per million in this specific sample. | Proportion of transcripts (per million) that this gene represents in the sample's transcriptome. |

Note on FPKM vs. RPKM: FPKM is identical to RPKM in concept and calculation but is used for paired-end RNA-seq data where two reads can originate from a single fragment, preventing double-counting [27] [19].

Experimental Protocol & Calculation Workflow

This section outlines the standard workflow for quantifying gene expression from raw sequencing data to normalized values, applicable to most RNA-seq experiments [5] [19].

1. Raw Read Processing: Begin with FASTQ files containing raw sequencing reads. Perform quality control (e.g., with FastQC) and trim adapter sequences and low-quality bases (e.g., with Trimmomatic or fastp) [5].

2. Read Alignment or Pseudoalignment: Map the cleaned reads to a reference genome or transcriptome using aligners like STAR or HISAT2, or use faster pseudoaligners like Kallisto or Salmon that avoid generating large BAM files [5] [19].

3. Quantification: Count the number of reads mapped to each gene or transcript. This can be done from BAM files using tools like featureCounts or directly by pseudoaligners [5]. The output is a table of raw counts for each gene in each sample.

4. Within-Sample Normalization: Apply your chosen normalization method to the raw counts. The step-by-step calculations are shown in the diagram and details below.

The following diagram illustrates the calculation workflows for RPKM/FPKM and TPM, highlighting the critical difference in the order of operations.

Calculation Workflow for RPKM/FPKM vs. TPM

Step-by-Step Formulas:

Calculating RPKM/FPKM [27]:

- RPM = (Reads mapped to gene) / (Total mapped reads / 1,000,000)

- RPKM = RPM / (Gene length in kilobases)

-

- RPK = (Reads mapped to gene) / (Gene length in kilobases)

- Per Million Scaling Factor = (Sum of all RPK values in the sample) / 1,000,000

- TPM = RPK / Per Million Scaling Factor

The Scientist's Toolkit

The table below lists essential reagents, software, and computational tools for performing RNA-seq analysis and normalization.

| Category | Item/Software | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Oligo(dT) Beads | Enriches for polyadenylated mRNA from total RNA [30]. |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA to sequence other RNA types [30]. | |

| Fragmentation Buffers | Randomly fragments RNA or cDNA to an appropriate size for sequencing [5]. | |

| Computational Tools | FastQC / MultiQC | Performs initial quality control on raw FASTQ files; MultiQC aggregates reports from multiple samples [5]. |

| Trimmomatic / Cutadapt | Trims adapter sequences and low-quality bases from reads [5]. | |

| STAR / HISAT2 | Aligns (maps) sequenced reads to a reference genome [5] [19]. | |

| Kallisto / Salmon | Performs ultra-fast pseudoalignment and transcript quantification, outputting TPM values directly [5] [19]. | |

| featureCounts | Counts the number of reads mapped to each gene from a BAM file, generating raw counts [5]. | |

| DESeq2 / edgeR | R packages for differential gene expression analysis; use their built-in normalization methods (RLE, TMM) for cross-sample comparisons [5] [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary goal of between-sample normalization? The main goal is to adjust raw read counts to account for technical variations between samples, such as differences in sequencing depth (total number of reads) and library composition, which if left uncorrected, can lead to false conclusions in downstream analyses like differential expression [18] [5].

My experiment has a global shift in expression in one condition. Which normalization method should I use? Global shifts in expression, where most or all genes are differentially expressed, violate the assumption (made by methods like TMM and RLE) that most genes are not DE [18]. In such cases, consider methods that use spike-in controls [31] or negative control genes, as they do not rely on this assumption.

What is the difference between TPM and RLE normalization? TPM (Transcripts per Million) is a within-sample normalization method that corrects for both sequencing depth and gene length, making it suitable for comparing the relative abundance of different transcripts within the same sample [5] [1]. RLE (Relative Log Expression), used by DESeq2, is a between-sample method that calculates a scaling factor (size factor) for each sample based on the median of ratios to a pseudo-reference, primarily correcting for sequencing depth and library composition for comparisons across samples [5] [3].

How does normalization affect the construction of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs)? The choice of normalization method significantly impacts the content and predictive accuracy of condition-specific GEMs. Between-sample methods like RLE, TMM, and GeTMM generally produce models with lower variability and more accurately capture disease-associated genes compared to within-sample methods like TPM and FPKM [3].

What should I do if I need to integrate multiple datasets from different batches or sequencing runs? For integrating multiple datasets, it is crucial to correct for batch effects. After initial between-sample normalization (e.g., with TMM or RLE), use batch correction tools like ComBat or Harmony to remove technical variations introduced by different batches, labs, or platforms [1] [32].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inflated false positives in differential expression analysis.

- Potential Cause 1: Incorrect normalization that fails to account for differences in library composition, especially when a few genes are extremely highly expressed in one condition [18] [5].

- Solution:

- Verification: Check the distribution of read counts across samples. A few genes constituting a very large proportion of the total reads in a sample indicates a potential library composition issue.

Problem: Poor separation between biological groups in PCA plots, with samples clustering by batch.

- Potential Cause: Strong batch effects or other unknown sources of technical variation are present in the data [31].

- Solution:

- Verification: Perform PCA on the normalized data before and after batch correction. Successful correction should show better clustering by biological condition.

Problem: Normalization method performs poorly due to a global shift in gene expression.

- Potential Cause: The assumption made by most common methods (that the majority of genes are not DE) is violated [18] [31].

- Solution: Employ a control-based normalization strategy.

- Spike-in controls: Use externally added RNA spike-in controls (e.g., ERCC spikes) during library preparation and apply methods like RUVg that leverage these controls for normalization [31].

- In-silico controls: If spike-ins are unavailable, methods like RUVr can use residuals from a first-pass DE analysis, or a set of stable housekeeping genes can be defined as empirical controls [31].

Comparison of Common Between-Sample Normalization Methods

The table below summarizes key methods used for between-sample normalization. Note that TPM and FPKM are included for context but are primarily within-sample methods.

Table 1: Common RNA-Seq Normalization Methods

| Method | Category | Key Principle | Corrects For | Best Suited For | Common Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM | Within-Sample | Simple scaling by total reads | Sequencing depth | Comparing counts within a sample, not for DE analysis | Basic calculation [5] |

| TPM/FPKM | Within-Sample | Accounts for transcript length and sequencing depth | Sequencing depth, Gene length | Comparing gene expression within a single sample [5] [1] | Basic calculation |

| TMM | Between-Sample | Trimmed Mean of M-values; assumes most genes are not DE | Sequencing depth, Library composition | Standard DE analysis where composition bias is a concern | edgeR [33] [3] |

| RLE (Median of Ratios) | Between-Sample | Relative Log Expression; median ratio to a pseudo-reference | Sequencing depth, Library composition | Standard DE analysis; robust to composition biases | DESeq2 [5] [3] |

| Upper Quartile (UQ) | Between-Sample | Scales based on upper quartile of counts | Sequencing depth | An alternative to total count, but can be biased by high-expression genes [12] | edgeR & others [33] |

| Quantile | Between-Sample | Makes the distribution of expression values identical across samples | Sequencing depth, Distribution shape | Making sample distributions comparable; often used in microarray and RNA-seq | Various packages [1] |

| RUV (e.g., RUVg) | Between-Sample / Batch Correction | Uses control genes/samples to estimate unwanted variation | Known & unknown batch effects, Library prep artifacts | Complex experiments with batch effects or global expression shifts | RUVSeq [31] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Between-Sample Normalization with TMM or RLE for Differential Expression Analysis

This protocol is suitable for most standard RNA-seq experiments where the assumption of non-DE for most genes holds.

- Input Data: A raw count matrix (genes x samples) generated by aligners like STAR or HISAT2 and quantifiers like featureCounts or HTSeq [5].

- Filtering: Remove genes with very low counts across all samples (e.g., genes with less than 10 counts in all samples) to reduce noise.

- Normalization:

- For TMM: Use the

calcNormFactorsfunction in theedgeRR package. This calculates scaling factors for each library, which are then incorporated into the subsequent DE model [33] [3]. - For RLE: This is automatically performed by the

DESeq2R package when you use theDESeqfunction on aDESeqDataSetobject. It calculates size factors using the median-of-ratios method [5] [3].

- For TMM: Use the

- Downstream Analysis: Proceed with differential expression testing using

edgeRorDESeq2's statistical frameworks.

Protocol 2: Normalization with Batch Effect Correction Using RUV

This protocol is for experiments with known or suspected batch effects (e.g., from multiple sequencing runs or labs) [31].

- Input Data: A raw count matrix.

- Preprocessing: Perform a basic filtering step as in Protocol 1.

- Initial Normalization (Optional): Some RUV approaches can be applied to raw counts or on residuals after an initial adjustment.

- Defining Controls:

- Apply RUV: Use the

RUVSeqR package. For example, theRUVgfunction can be used by providing the count matrix and the set of control genes. The parameterkspecifies the number of unwanted factors to estimate and remove. - Differential Expression: Use the normalized counts and the estimated factors of unwanted variation as covariates in your DE analysis model (e.g., in

DESeq2oredgeR).

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting an appropriate normalization strategy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Normalization

| Item | Function in Normalization |

|---|---|

| ERCC Spike-In Controls | A set of synthetic RNA transcripts added to each sample in known concentrations. They serve as negative controls for normalization, especially when global expression changes are expected or to account for technical variability during library preparation [31]. |

| UMI (Unique Molecular Identifier) | Short random nucleotide sequences ligated to each RNA molecule before PCR amplification. UMIs allow for the accurate counting of original mRNA molecules, correcting for PCR amplification bias, which is particularly crucial in single-cell RNA-seq but also beneficial in bulk [34]. |

| Reference RNA Samples | Commercially available standardized RNA samples (e.g., from Stratagene or Ambion). They can be used across experiments or labs as a benchmark to assess technical performance and normalization efficacy [12]. |

| Stable Housekeeping Genes | A set of endogenous genes empirically determined to have constant expression across all conditions in your experiment. They can be used as in-silico control genes for methods like RUV [31]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is per-gene normalization, and how does it differ from global normalization methods?