RNA-seq Outlier Identification: From Technical Noise to Biological Discovery in Biomedical Research

RNA-seq outlier identification has evolved from a quality control measure to a powerful approach for biological discovery and clinical diagnostics.

RNA-seq Outlier Identification: From Technical Noise to Biological Discovery in Biomedical Research

Abstract

RNA-seq outlier identification has evolved from a quality control measure to a powerful approach for biological discovery and clinical diagnostics. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to implement robust outlier analysis, covering foundational concepts, methodological applications across rare diseases and oncology, troubleshooting of technical variations, and validation strategies. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging research, we demonstrate how transcriptomic outlier patterns can reveal novel disease mechanisms, identify therapeutic targets in difficult-to-treat cancers, and increase diagnostic yields in rare genetic disorders, ultimately advancing precision medicine approaches.

Beyond Quality Control: Understanding the Biological Significance of RNA-seq Outliers

In RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, an outlier sample is one that deviates significantly from the overall pattern of a distribution, potentially due to technical artifacts or genuine biological variation. Accurate identification of these outliers is critical because technical outliers introduce unnecessary variance that reduces statistical power, while removing true biological outliers can lead to underestimation of natural biological variance and spurious conclusions [1]. The complex, multi-step protocols in RNA-seq data acquisition—from mRNA isolation and reverse transcription to fragmentation, adapter ligation, PCR, and sequencing—create multiple opportunities for technical variations that may produce outlier samples [1] [2]. This guide provides comprehensive methodologies for detecting, understanding, and addressing outlier samples within the context of a broader research thesis on RNA-seq quality assurance.

Defining and Classifying RNA-Seq Outliers

What Constitutes an RNA-Seq Outlier?

An outlier in RNA-seq data is traditionally defined as "an observation that lies outside the overall pattern of a distribution" [1]. However, in high-dimensional RNA-seq data, this simple definition becomes increasingly difficult to apply without sophisticated statistical methods. outliers can be technically driven, stemming from issues during library preparation or sequencing, or they can represent true biological anomalies that may be of significant scientific interest [1].

Classification of Outlier Types

| Outlier Category | Primary Cause | Typical Impact | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technical Outliers | Protocol failures, contamination, or sequencing errors [3] [1] | Introduces noise and reduces statistical power [1] | Remove from analysis after confirmation |

| Biological Outliers | Genuine biological variation or rare biological states [1] | May represent important biological phenomena | Verify biologically before deciding to exclude |

| Confounded Outliers | Combination of technical and biological factors [4] | Difficult to interpret; may mask or mimic signals | Requires careful investigation of both aspects |

Methodologies for Outlier Detection

Robust Principal Component Analysis (rPCA)

Theoretical Framework: Classical PCA (cPCA) is highly sensitive to outlying observations, which often pull components toward them, potentially obscuring the true variation in the data. Robust PCA methods address this limitation by using statistical techniques that are resistant to outlier influence [1].

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Preparation: Begin with normalized count data, typically transformed using variance-stabilizing or log-like transformations

- Algorithm Selection: Implement either PcaHubert (higher sensitivity) or PcaGrid (lower false positive rate) from the

rrcovR package [1] - Outlier Identification: Samples flagged by the robust distance measure are potential outliers

- Visualization: Create PCA biplots comparing classical and robust methods to visualize outlier influence

Performance Metrics: In controlled tests, PcaGrid has demonstrated 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity across various simulated outlier scenarios, including both high-divergence and low-divergence outliers [1].

The OutSingle Algorithm for Outlier Detection

Theoretical Basis: OutSingle (Outlier detection using Singular Value Decomposition) uses a log-normal approach for count modeling combined with optimal hard threshold (OHT) method for noise detection via singular value decomposition (SVD) [4]. This method provides an efficient alternative to negative binomial distribution-based models.

Experimental Protocol:

- Initial Processing: Log-transform the RNA-seq count data and calculate gene-specific z-scores

- Confounder Control: Apply optimal hard thresholding to singular values obtained through SVD to remove technical noise

- Outlier Detection: Identify samples with extreme z-scores after confounder adjustment

- Validation: Compare detection rates with established methods on benchmark datasets

Performance Advantages: OutSingle outperforms previous state-of-the-art models like OUTRIDER, particularly in detecting real biological outliers masked by confounders, with significantly faster computation times [4].

Iterative Leave-One-Out (iLOO) Approach

Theoretical Framework: The iLOO method uses a probabilistic approach to measure deviation between an observation and the distribution generating the remaining data within an iterative leave-one-out design [5]. This approach addresses sensitivity issues with sparse data and heavy-tailed distributions common in RNA-seq.

Implementation:

- R Code Availability: The algorithm is implemented in R and publicly available [5]

- Design: Iteratively excludes each sample, calculates distribution parameters from remaining data, then quantifies the deviation of the excluded sample

- Application: Effective for both non-normalized and normalized negative binomial distributed data [5]

Comparative Analysis of Detection Methods

| Method | Algorithm Type | Strengths | Limitations | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rPCA (PcaGrid) | Robust statistics [1] | 100% sensitivity/specificity in tests; low false positive rate [1] | Requires high-quality normalization; may miss biologically relevant outliers | Small sample sizes; high-dimensional data |

| OutSingle | SVD-based [4] | Fast computation; handles confounders well; can inject artificial outliers [4] | Relies on log-normal assumption | Large datasets; confounder-heavy data |

| iLOO | Iterative probabilistic [5] | Handles sparse data; works with negative binomial distribution [5] | Computationally intensive for very large sample sizes | Small to medium datasets with sparse counts |

| Classical PCA | Standard dimensionality reduction [1] | Widely available; simple implementation | Highly sensitive to outliers; unreliable with outlier presence [1] | Initial exploration only |

| Visual Inspection | Subjective assessment [6] | Quick; intuitive | Unreliable; carries unconscious biases [1] | Preliminary screening |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common RNA-Seq Outlier Scenarios

FAQ: Addressing Specific Outlier Detection Challenges

Q: My MDS plot shows one clear outlier sample, but its sequencing QC metrics are normal. Should I remove it?

A: This scenario represents a classic outlier dilemma [6]. If the sample shows normal sequencing quality controls but clusters separately from biological replicates in dimensionality reduction plots, investigate further:

- Check if the outlier drives differential expression results (e.g., significant DEGs disappear when it's removed) [6]

- Examine if the genes driving separation are biologically plausible (e.g., contamination markers)

- When other samples cluster tightly and the outlier is extreme, removal is generally recommended even without a clear "smoking gun" [6]

Q: How can I distinguish between technical artifacts and true biological outliers?

A: This distinction requires systematic investigation:

- Technical Assessment: Verify library preparation logs, RNA quality metrics (RIN > 7), and reagent batches [3] [7]

- Biological Validation: Check if outlier expression patterns align with known biological pathways or potential contamination sources

- Experimental Context: Consider whether the sample comes from a unique biological context (e.g., severe disease end of spectrum) that might explain divergence [1]

- Statistical Evidence: Use robust methods like rPCA that objectively flag outliers rather than relying on visual inspection alone [1]

Q: What are the consequences of improperly handling outliers in RNA-seq analysis?

A: The impacts are significant and bidirectional:

- Keeping Technical Outliers: Increases unnecessary variance, reduces statistical power for detecting true differential expression, and may produce false positives [1]

- Removing Biological Outliers: Underestimates natural biological variance, increases risk of spurious conclusions, and may discard biologically meaningful signals [1]

- Best Practice: Always document and report outlier decisions transparently, and consider conducting analyses both with and without borderline cases

Research Reagent Solutions for Quality Assurance

| Reagent/Kit | Primary Function | Role in Outlier Prevention | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| QIAseq FastSelect | rRNA removal [8] | Reduces technical variation from ribosomal RNA contamination | Removes >95% rRNA in 14 minutes |

| SMARTer Stranded Total RNA-Seq Kit | Library preparation [8] | Maintains strand specificity with low inputs | Ideal for limited samples; reduces preparation artifacts |

| NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Kit | mRNA enrichment [7] | Ensures high-quality mRNA input for library prep | Requires high RNA integrity (RIN > 7) |

| PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit | RNA extraction from limited samples [7] | Preserves RNA quality from precious samples | Critical for single-cell or low-input protocols |

| TapeStation System | RNA quality assessment [8] | Identifies degraded samples before library prep | RIN < 7 indicates potential problems |

Experimental Design for Proactive Outlier Management

Preventing Outliers Through Better Experimental Planning

Sample Preparation Consistency:

- Standardize RNA extraction protocols across all samples [9]

- Process controls and experimental conditions simultaneously whenever possible [7]

- Minimize freeze-thaw cycles and maintain consistent handling procedures [7]

Library Preparation Considerations:

- Use cDNA library equalization to reduce technical variation and improve gene detection rates [10]

- Implement unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to address PCR amplification biases

- Consider ribosomal depletion instead of poly-A selection for degraded samples [2]

Sequencing Design:

- Sequence controls and experimental conditions on the same flow cell to minimize batch effects [7]

- Include technical replicates to assess protocol consistency

- Ensure sufficient sequencing depth based on experimental goals [2]

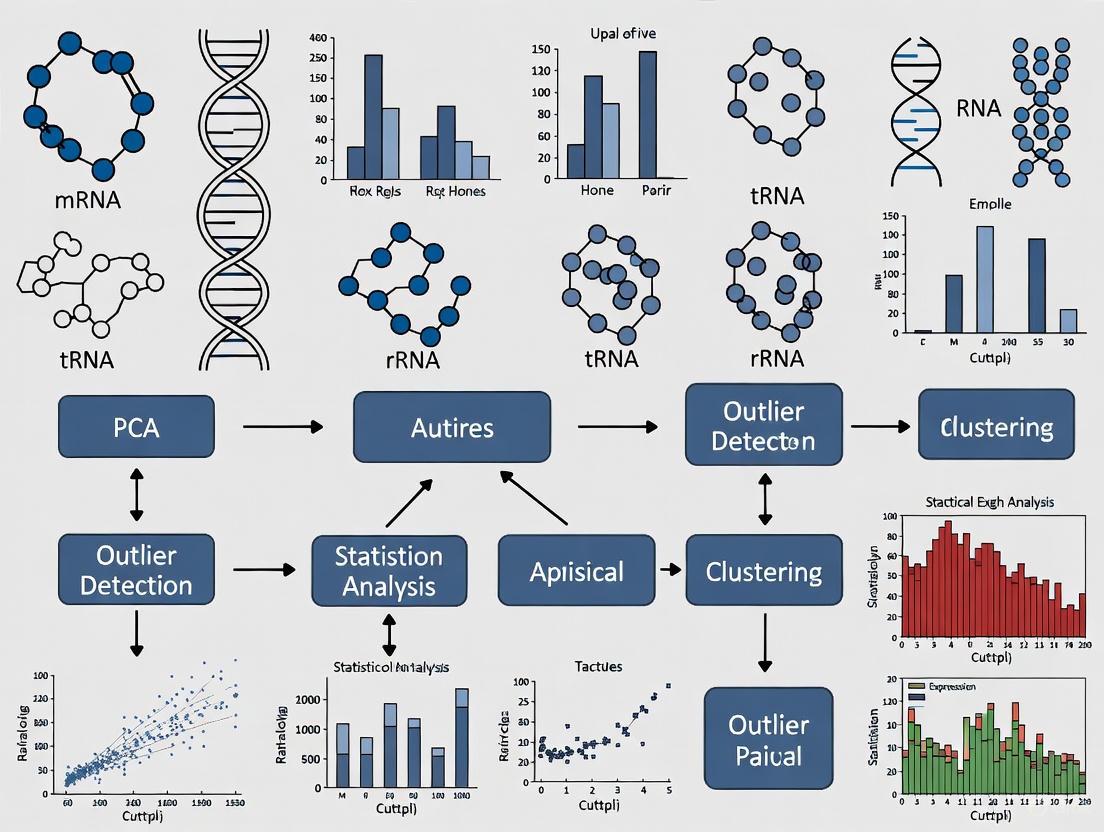

Visualization Workflow for Outlier Analysis

Effective identification and management of RNA-seq outliers requires a multifaceted approach combining robust statistical methods with biological reasoning. While methods like rPCA, OutSingle, and iLOO provide objective detection frameworks, researcher judgment remains essential for interpreting results within specific experimental contexts. Future directions in outlier management will likely involve improved integration of detection methods into standard analysis pipelines, development of more sophisticated classification algorithms distinguishing technical from biological outliers, and community standards for reporting outlier decisions in publications. By implementing these systematic approaches to outlier detection, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability and biological relevance of their RNA-seq findings.

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data analysis, outliers—samples or observations that deviate markedly from others—present a complex challenge. They are traditionally viewed as technical artifacts to be removed to ensure data integrity. However, emerging evidence reveals that many outliers represent genuine biological variation with significant diagnostic value [11]. This technical support document examines both perspectives, providing frameworks for identifying, interpreting, and addressing outliers in research and diagnostic settings.

The fundamental challenge lies in distinguishing technical artifacts from biological signals. Technical outliers arise from multiple sources, including variations in RNA extraction, library preparation, sequencing depth, and instrumentation [1] [2]. Conversely, biological outliers may stem from genuine rare genetic variations, spontaneous transcriptional activation, or unique cellular responses [11]. Understanding this dual nature is crucial for making informed analytical decisions.

Detection Methodologies: Statistical Frameworks and Tools

Computational Tools for Outlier Detection

Several specialized algorithms have been developed to identify outliers in RNA-seq data. The table below summarizes key methods and their applications.

Table: RNA-Seq Outlier Detection Methods and Applications

| Method/Tool | Underlying Approach | Primary Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| OUTRIDER | Autoencoder with Negative Binomial distribution | Detecting aberrant gene expression in rare disease diagnostics | [12] |

| FRASER/FRASER2 | Splicing outlier detection | Identifying transcriptome-wide splicing defects, including minor spliceopathies | [13] [14] |

| OutSingle | Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) with Optimal Hard Threshold | Confounder-controlled outlier detection in gene expression data | [4] |

| Robust PCA (PcaGrid) | Robust principal component analysis | Accurate outlier sample detection in high-dimensional data with small sample sizes | [1] |

| iLOO (Iterative Leave-One-Out) | Probabilistic approach with leave-one-out design | Feature-level outlier detection in negative binomial distributed data | [15] |

Practical Workflow for Outlier Analysis

A robust outlier analysis strategy involves multiple steps, from quality control to biological interpretation. The following diagram illustrates a recommended workflow for handling outliers in RNA-seq data analysis:

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How can I determine if an outlier sample results from technical error or genuine biological variation?

A1: Begin by examining quality control metrics. Technical outliers often exhibit:

- Low mapping percentages (<70% for human genome) [2]

- Abnormal GC content or gene length biases

- Irregular distribution of read coverage across transcripts

- Strand-specific biases in strand-preserving protocols

Biological outliers typically show:

- Normal QC metrics alongside specific aberrant expression patterns

- Co-regulation of functionally related genes [11]

- Reproducibility in independent experimental replicates

- Correlation with specific genetic variants or clinical phenotypes [13]

Q2: What is the minimum sample size required for reliable outlier detection?

A2: While some methods work with small sample sizes (n=2-6), detection power increases with larger cohorts. For rare biological event detection, studies with hundreds of samples dramatically improve identification of meaningful outliers [13]. Down-sampling analysis shows that even with only 8 individuals, approximately half of genes with extreme expression can be detected, with numbers increasing with sample size [11].

Q3: How do I handle outliers in single-cell RNA-seq data where dropout events are common?

A3: In scRNA-seq, embrace dropout patterns as potential biological signals rather than exclusively as noise:

- Use binarized expression (0/1 for undetected/detected) for co-occurrence clustering [16]

- Implement algorithms like M3Drop or scBFA that specifically model dropout characteristics

- Recognize that genes in the same pathway often exhibit similar dropout patterns across cell types

Q4: Can outlier removal improve differential expression analysis?

A4: Yes, when properly identified technical outliers are removed. One study demonstrated that removing outliers detected by robust PCA (PcaGrid) significantly improved the performance of differential gene detection and downstream functional analysis [1]. However, caution must be exercised—removing true biological outliers can lead to underestimation of natural biological variance and spurious conclusions.

Q5: How effective are NMD inhibitors in revealing splicing outliers?

A5: Cycloheximide (CHX) treatment significantly improves detection of transcripts subject to nonsense-mediated decay. Studies show CHX treatment increases expression of NMD-sensitive transcripts, enabling identification of splicing defects that would otherwise be masked [14]. Always include internal controls like SRSF2 transcripts to verify NMD inhibition efficacy.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Transcriptome-Wide Splicing Outlier Analysis

This protocol identifies individuals with rare spliceosome defects through intron retention patterns [13] [14]:

Sample Preparation:

- Collect whole blood in EDTA tubes

- Isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) using density gradient centrifugation

- Culture cells briefly with cycloheximide (CHX, 100μg/mL for 4-6 hours) to inhibit NMD

- Extract RNA using standard column-based methods

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Assess RNA integrity (RIN > 8 recommended)

- Perform ribosomal RNA depletion (do not use poly-A selection)

- Prepare strand-specific libraries with dUTP method

- Sequence on Illumina platform (minimum 30 million paired-end reads recommended)

Computational Analysis:

- Align reads to reference genome using STAR or HISAT2

- Run FRASER or FRASER2 to detect splicing outliers

- Focus on intron retention events in minor intron-containing genes (MIGs)

- Examine transcriptome-wide patterns rather than single-gene events

- Validate findings with Sanger sequencing of candidate variants

Protocol 2: Robust Outlier Sample Detection

This protocol identifies technical and biological outlier samples in a cohort study [1]:

Data Preprocessing:

- Perform standard RNA-seq quality control (FastQC, Trimmomatic)

- Align reads to reference genome/transcriptome

- Generate raw count matrix using featureCounts or HTSeq

Outlier Detection:

- Normalize counts using DESeq2 or edgeR median ratio method

- Apply robust PCA (PcaGrid function in rrcov R package)

- Calculate outlier distances for each sample

- Flag samples with distance > critical value (based on chi-square distribution)

- Compare with classical PCA to identify samples masked by non-robust methods

Validation:

- Correlate outlier status with clinical metadata and technical batch information

- Perform differential expression with and without outliers

- Use quantitative RT-PCR to validate key findings

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for a comprehensive outlier analysis that balances both technical and biological considerations:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents and Resources for RNA-Seq Outlier Research

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Purpose | Application Example | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cycloheximide (CHX) | Nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) inhibition | Revealing aberrant transcripts degraded by NMD | [14] |

| RNase Inhibitors | Prevention of RNA degradation during isolation | Maintaining RNA integrity for accurate quantification | [2] |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Removal of ribosomal RNA | Enhancing sequencing depth for mRNA | [13] [14] |

| Strand-Specific Library Prep Kits | Preservation of transcript orientation | Accurate identification of antisense transcripts | [2] |

| FRASER/FRASER2 Software | Splicing outlier detection | Identifying minor spliceopathies | [13] [17] |

| OUTRIDER Package | Aberrant expression detection | Diagnosing rare genetic disorders | [12] [14] |

| Robust PCA Algorithms | Outlier sample detection | Identifying technical artifacts in small sample studies | [1] |

Outliers in RNA-seq data present both challenges and opportunities. While technical artifacts must be identified and addressed to ensure data quality, biological outliers often contain valuable insights into rare genetic conditions, spontaneous transcriptional events, and novel regulatory mechanisms. By implementing robust detection methodologies, following standardized protocols, and maintaining a balanced perspective on the dual nature of outliers, researchers can maximize both the reliability and discovery potential of their RNA-seq analyses.

The field continues to evolve with new computational methods and experimental approaches that enhance our ability to distinguish biological signals from technical noise. Integrating these advances into standardized workflows will further unlock the diagnostic and research potential of transcriptomic outliers.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs for RNA-Seq Outlier Identification

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is outlier identification critical in RNA-Seq data analysis? Outliers in RNA-Seq data can significantly distort analytical results and lead to erroneous conclusions in downstream analyses, such as differential expression testing [18]. These extreme values may arise from technical artifacts, but recent research also identifies them as potential biological realities that should be investigated rather than automatically discarded [11]. Proper identification ensures the accuracy of transcript measurements and correct biological interpretations.

Q2: What is the fundamental difference between the IQR/Tukey's Fences and Z-score methods? The Interquartile Range (IQR) and Tukey's Fences method is a non-parametric approach based on data quartiles, making it robust to non-normal distributions and extreme values [19] [20]. In contrast, the Z-score method is parametric and assumes your data approximately follows a normal distribution, as it measures how many standard deviations a point is from the mean [21]. For RNA-Seq data, which often exhibits overdispersion and skewed distributions, Tukey's Fences is generally more reliable.

Q3: How do I choose the threshold (k-value) for Tukey's Fences?

The choice of k depends on how conservative you want to be:

- k = 1.5: Identifies "regular" outliers. This is a common default but can flag a high percentage of data points as outliers, especially in large samples [19] [22].

- k = 3.0: Identifies "far" or extreme outliers. This is more conservative and recommended for stringent outlier detection in RNA-Seq data to avoid removing biologically relevant but rare expression events [19] [11].

- k = 5.0: Used for very conservative identification of extreme over-expression in transcriptomic studies [11].

Q4: A sample in my RNA-Seq dataset was flagged as an outlier. Should I always remove it? Not necessarily. First, investigate the potential cause:

- Technical Error: Check for issues like low sequencing quality, adapter contamination, or high ribosomal RNA content using QC tools like RNA-QC-Chain or FastQC [18] [23]. If a technical error is confirmed, exclusion is justified.

- Biological Reality: Outlier expression may represent sporadic, genuine biological events [11]. If the outlier is reproducible and biological validation is possible, it might be worth further investigation instead of removal.

Comparison of Key Outlier Detection Methods

The following table summarizes the core components of the two primary outlier detection methods discussed.

| Feature | IQR & Tukey's Fences | Z-Score Method |

|---|---|---|

| Core Formula | IQR = Q3 - Q1Upper Fence = Q3 + k * IQRLower Fence = Q1 - k * IQR [24] [25] |

z = (x - μ) / σ [21] |

| Typical Threshold | k = 1.5 for regular outliersk = 3.0 for extreme outliers [19] |

z > 3 or z < -3 [21] |

| Distribution Assumption | Non-parametric; no assumption of normality [19] [20] | Parametric; assumes normal distribution [21] |

| Robustness to Extreme Values | High (uses quartiles, which are resistant to extremes) [26] | Low (mean and standard deviation are influenced by extremes) [19] |

| Primary Use Case in RNA-Seq | General-purpose outlier detection, especially for skewed data or data with potential outliers [11] | Can be used when data is known to be normally distributed, but less common for raw counts [21] |

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Identifying Outliers using Tukey's Fences in RNA-Seq Data

This protocol is ideal for gene expression values across samples.

- Prepare Data: Start with a normalized gene expression matrix (e.g., TPM, CPM). Work on a per-gene basis, analyzing the expression distribution of one gene across all samples [11].

- Calculate Quartiles:

- Compute Interquartile Range (IQR):

IQR = Q3 - Q1[24] [25]. - Establish Tukey's Fences:

- Lower Fence =

Q1 - k * IQR - Upper Fence =

Q3 + k * IQR - For a conservative approach in RNA-Seq, start with

k = 3[11].

- Lower Fence =

- Identify Outliers: Any sample where the gene's expression value falls below the Lower Fence or above the Upper Fence is considered an outlier for that gene [19] [20].

Protocol 2: Identifying Outliers using the Z-Score Method

Use this method with caution, primarily if the expression data is known to be normally distributed (e.g., after log-transformation).

- Prepare and Transform Data: Use a normalized and log-transformed expression matrix to better approximate a normal distribution.

- Calculate Mean and Standard Deviation:

- For a given gene, compute the mean (μ) expression across all samples.

- Compute the standard deviation (σ) of the expression values [21].

- Compute Z-Scores: For each sample's expression value (x) for the gene, calculate the Z-score:

z = (x - μ) / σ[21]. - Identify Outliers: Flag any sample with an absolute Z-score greater than your threshold (e.g.,

|z| > 3) as an outlier. A Z-score of 3 corresponds to a value more than 3 standard deviations from the mean, which is highly unlikely in a normal distribution [21].

Workflow and Decision Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the statistical concepts and the decision pathway for handling outliers in an RNA-Seq experiment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| RNA-QC-Chain [18] | A comprehensive, all-in-one quality control pipeline for RNA-Seq data. It performs sequencing quality assessment, trims low-quality reads, filters ribosomal RNA, and identifies contamination. | Pre-processing of raw FASTQ files to ensure data quality before statistical analysis and outlier detection. |

| RSeQC [18] | Provides RNA-seq-specific quality control metrics based on alignment files, such as gene body coverage, read distribution, and strand specificity. | Post-alignment QC to identify biases that might lead to or explain outlier samples. |

| Normalized Expression Matrix (TPM/CPM) [11] | The starting material for outlier detection. Transcripts Per Million (TPM) or Counts Per Million (CPM) normalize for sequencing depth, allowing for sample comparison. | The fundamental data structure on which IQR or Z-score calculations are performed across samples for each gene. |

| Statistical Software (R/Python) | Provides the computational environment to calculate IQR, Tukey's Fences, Z-scores, and generate visualizations like boxplots and Q-Q plots. | The primary platform for implementing the statistical protocols outlined in this guide. |

| Tukey's Fences (k=3.0) [11] | A specific, conservative threshold for defining an "extreme outlier" in gene expression data, corresponding to a very low p-value under a normal assumption. | The recommended parameter for stringent outlier identification in RNA-Seq studies to avoid removing true biological signals. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the evidence that outlier gene expression is a biological phenomenon and not just technical noise?

Recent research demonstrates that outlier gene expression patterns are a biological reality, reproducible across tissues and species. A 2025 study analyzed multiple large datasets, including outbred and inbred mice, human GTEx data, and different Drosophila species, finding comparable general patterns of outlier gene expression in all. Crucially, these outliers were fully reproducible in independent sequencing experiments, confirming they are not technical artifacts. The study also used a three-generation family analysis in mice to show that most extreme over-expression is not inherited but appears sporadically, suggesting it may be linked to "edge of chaos" effects in gene regulatory networks [11].

FAQ 2: My dataset has limited samples. Which outlier detection method is recommended for small sample sizes?

For datasets with a small number of samples, OutPyR is specifically designed for this scenario. It uses Bayesian inference to identify abnormal RNA-Seq gene expression counts, incorporating data-augmentation techniques to efficiently infer parameters of the underlying negative binomial process while assessing inference uncertainty [27]. This approach is particularly valuable when large sample sizes are not available.

FAQ 3: How can I control for confounders that might mask true biological outliers in my RNA-Seq data?

The OutSingle algorithm provides an effective solution for confounder control. It uses Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) with the recently discovered optimal hard threshold (OHT) method for noise detection. This approach offers a deterministic, computationally efficient way to control for confounders without the complexity of autoencoder-based methods [4]. For sample-level outlier detection, robust Principal Component Analysis (rPCA) methods, particularly PcaGrid, have demonstrated 100% sensitivity and specificity in detecting outlier samples in RNA-Seq data, even with small sample sizes [1].

FAQ 4: What statistical cutoff should I use to define an extreme outlier expression value?

While common practice often uses multiples of the interquartile range (IQR), research specifically focused on extreme outliers recommends a conservative threshold of Q3 + 5 × IQR for defining "over outliers" (OO) and Q1 - 5 × IQR for "under outliers" (UO). This corresponds to approximately 7.4 standard deviations above the mean in a normal distribution (P-value ≈ 1.4 × 10⁻¹³), providing a very stringent cutoff that satisfies multiple testing corrections [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Difficulty Distinguishing Technical Artifacts from Biological Outliers

Problem: Suspected outliers in your data could be either technical errors or genuine biological signals.

Solution:

- Apply Reproducibility Testing: If resources allow, perform independent sequencing experiments on the same samples to verify if outlier patterns persist [11].

- Implement Robust PCA: Use rPCA methods (PcaGrid or PcaHubert) to objectively identify outlier samples rather than relying on subjective visual inspection of PCA biplots [1].

- Examine Co-regulation Patterns: Check if outlier genes form co-regulatory modules or known pathways, which suggests biological significance rather than random technical errors [11].

Issue: Outlier Detection Masked by Confounding Factors

Problem: True biological outliers are being hidden by technical batch effects or other confounding variables.

Solution:

- Apply OutSingle Algorithm: Implement this method which uses SVD with optimal hard thresholding to control for confounders while preserving true outlier signals [4].

- Utilize FRASER for Splicing Outliers: For aberrant splicing event detection, use FRASER which automatically controls for latent confounders while identifying statistically significant outlier splicing events [28].

- Leverage GTEx Data: Use large-scale reference datasets like GTEx to establish baseline covariation patterns specific to your tissue of interest [28].

Table 1: Prevalence of Extreme Outlier Genes Across Species and Tissues

| Species | Tissue | Sample Size | Genes with Extreme Outliers (≥1 per dataset) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse (Outbred) | Multiple organs | 48 individuals | 3-10% of all genes (~350-1350 genes) | [11] |

| Human (GTEx) | Multiple tissues | 543 donors | Comparable patterns observed | [11] |

| Drosophila | Head & trunk | 27 individuals | Comparable patterns observed | [11] |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Outlier Detection Methods

| Method | Approach | Strengths | Limitations | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OutSingle | Log-normal z-scores with SVD/OHT confounder control | Almost instantaneous computation; effective confounder control | Less performant on data with underexpressed outliers | Large datasets requiring fast processing [4] |

| rPCA (PcaGrid) | Robust principal component analysis | 100% sensitivity/specificity in tests; objective detection | Requires sufficient samples for PCA | Sample-level outlier detection [1] |

| OutPyR | Bayesian modeling of negative binomial distribution | Incorporates uncertainty assessment; works with small samples | Computationally demanding | Small datasets with limited samples [27] |

| FRASER | Beta-binomial distribution with autoencoder | Controls confounders; detects splicing outliers & intron retention | Complex implementation | Aberrant splicing detection [28] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Identification of Extreme Expression Outliers Using IQR Method

Purpose: To conservatively identify extreme outlier expression values in RNA-Seq data.

Materials:

- Normalized expression matrix (TPM, CPM, or normalized counts)

- Statistical software (R, Python, or equivalent)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Use normalized transcript fragment count data without log-transformation. Avoid pre-filtering of potential outlier samples [11].

- Calculate Quartiles: For each gene across samples, compute the 1st quartile (Q1) and 3rd quartile (Q3), then determine the interquartile range (IQR = Q3 - Q1).

- Set Conservative Thresholds:

- For "over outliers" (OO): Q3 + 5 × IQR

- For "under outliers" (UO): Q1 - 5 × IQR

- Identify Outlier Genes: Flag any gene expression values exceeding these thresholds in any sample.

- Validation: Examine outlier genes for co-regulatory patterns or pathway enrichment to confirm biological significance.

Notes: This threshold corresponds to approximately 7.4 standard deviations above the mean in a normal distribution (P ≈ 1.4 × 10⁻¹³) [11].

Protocol 2: Confounder-Control in Outlier Detection Using OutSingle

Purpose: To detect outliers in RNA-Seq gene expression data while controlling for confounding effects.

Materials:

- RNA-Seq count matrix (genes × samples)

- OutSingle software (https://github.com/esalkovic/outsingle)

Procedure:

- Input Data Preparation: Format your data as a J × N count matrix where J is genes and N is samples.

- Log-Normal Transformation: Convert counts using log-normal transformation to calculate gene-specific z-scores.

- Apply Optimal Hard Threshold: Use Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) with the Optimal Hard Threshold (OHT) method to denoise the z-score matrix and control for confounders.

- Outlier Identification: Detect outliers from the confounder-corrected z-scores.

- Optional Outlier Injection: Use OutSingle's inverse procedure to inject artificial outliers masked by confounding effects for method validation.

Notes: This method is particularly effective for identifying outliers masked by confounders and is significantly faster than autoencoder-based approaches [4].

Method Selection Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for RNA-Seq Outlier Research

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example/Reference | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference RNA Materials | Benchmarking and quality control | Quartet Project reference materials [29] | Enables assessment of subtle differential expression |

| ERCC Spike-In Controls | Technical controls for quantification | External RNA Control Consortium [30] | Assess accuracy of absolute measurements |

| OutSingle Software | Outlier detection with confounder control | https://github.com/esalkovic/outsingle [4] | Fast, deterministic method |

| rPCA Methods (PcaGrid) | Sample-level outlier detection | rrcov R package [1] | Objective detection vs. visual PCA inspection |

| FRASER Algorithm | Aberrant splicing event detection | Beta-binomial model [28] | Detects intron retention and alternative splicing |

| GTEX Data Reference | Baseline covariation patterns | GTEx Project dataset [28] | Tissue-specific reference for confounder control |

Frequently Asked Questions

What defines an RNA-seq sample as an "outlier"? An outlier sample shows global gene expression or splicing patterns that are significantly different from other samples in the dataset, even when standard quality control metrics appear normal. These samples can dramatically influence analysis results—for example, a single outlier might generate over 100 differentially expressed genes that disappear when the sample is removed [6].

Which visualization methods best reveal outlier samples? Multidimensional scaling (MDS) plots and principal component analysis (PCA) plots are most commonly used. In these visualizations, outlier samples appear separated from the main cluster of other samples. Sample distances plots with dendrograms also help identify outliers by showing which samples have dissimilar expression patterns [31] [32].

My data has an outlier sample but its sequencing quality is good. Should I remove it? Yes, generally. If an sample is a clear visual outlier on MDS/PCA plots and is driving differential expression results that disappear upon its removal, it should likely be excluded from analysis. This remains true even if standard sequencing QC metrics are acceptable, as the outlier status may reflect underlying biological or technical issues not captured by standard QC [6].

What tools can formally identify outlier samples beyond visual inspection? Several specialized tools exist:

- FRASER/FRASER2: Detect splicing outliers, particularly useful for identifying rare diseases affecting spliceosome function [13] [33]

- OUTRIDER: Identifies expression outliers using a negative binomial distribution model [4] [14]

- OutSingle: Uses singular value decomposition for rapid outlier detection in gene expression data [4]

Can outlier samples actually be biologically meaningful? Yes. While often removed as technical artifacts, outliers can sometimes reveal true biological phenomena. Recent research shows that samples with excess intron retention outliers in minor intron-containing genes can indicate rare genetic disorders affecting the minor spliceosome, known as "minor spliceopathies" [13] [33].

How do I handle outliers in a diagnostic setting? In clinical RNA-seq analysis, outliers should be carefully investigated rather than automatically removed. Transcriptome-wide outlier patterns can increase diagnostic yield for rare diseases. Removing them might discard valuable diagnostic information, particularly when patterns suggest spliceosome dysfunction [13] [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Single Sample Driving Differential Expression Results

Symptoms:

- Significant DEGs (100+) with all samples included

- Zero DEGs when one particular sample is removed

- Sample appears as visual outlier on MDS plot but has passing QC metrics

Investigation Steps:

- Confirm the outlier: Generate MDS and PCA plots to visually confirm the sample separates from others [6] [32]

- Check quality metrics: Verify mapping rates, read counts, and other standard metrics are comparable to other samples [31]

- Investigate biological causes: Use splicing outlier tools (FRASER) or expression outlier tools (OUTRIDER) to determine if the outlier pattern affects specific genes or pathways [13] [4]

- Examine experimental factors: Check if outlier corresponds to any known batch effects or processing differences

Resolution Paths:

- If technical artifact: Remove sample and proceed with analysis [6]

- If biological reality: Maintain sample but use robust statistical methods, or split analysis to investigate the outlier separately [13]

- If unclear provenance: Consider sample removal for conservative analysis, noting this decision in methods

Problem: Consistent Outlier Patterns Across Multiple Samples

Symptoms:

- Multiple samples cluster separately from main group

- Pattern correlates with known experimental factors (e.g., processing batch)

- Splicing or expression outliers affect specific functional groups of genes

Investigation Steps:

- Color PCA/MDS by experimental factors: Batch, processing date, sequencing lane, etc. [32]

- Test for batch effects: Use statistical methods to quantify variance explained by technical factors

- Analyze outlier gene patterns: Determine if outliers affect specific pathways (e.g., minor spliceosome genes) using FRASER or similar tools [13]

- Check for global splicing patterns: Examine whether outliers show excess intron retention in minor intron-containing genes, which might indicate spliceosome defects [33]

Resolution Paths:

- If batch effect: Include batch as covariate in analysis or use batch correction methods

- If biological subgroup: Analyze as separate group or include as factor in design matrix

- If spliceopathy pattern: Investigate further as potential rare disease diagnosis [13]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Outlier Detection in RNA-seq Data

Purpose: Systematically identify technical and biological outliers in RNA-seq datasets

Materials:

- Raw or normalized count matrix

- Sample metadata with experimental factors

- R or Python statistical environment

Procedure:

- Quality Control Assessment

- Calculate standard QC metrics: mapping rates, library sizes, gene detection counts [31]

- Check for samples with extreme values in any metric

Visual Outlier Detection

Statistical Outlier Detection

Differential Expression Sensitivity Analysis

- Perform DEG analysis with all samples

- Iteratively remove suspected outliers and re-run DEG analysis

- Note samples whose removal substantially changes results [6]

Biological Interpretation

- Identify genes driving outlier status

- Check if outlier genes belong to specific pathways (e.g., minor spliceosome)

- Correlate with available clinical or phenotypic data

Expected Results: Identification of samples that are technical outliers requiring removal, or biological outliers warranting further investigation.

Protocol 2: Splicing Outlier Analysis for Rare Disease Diagnosis

Purpose: Identify individuals with rare spliceosome disorders using transcriptome-wide splicing outlier patterns

Materials:

- RNA-seq data from whole blood or PBMCs

- FRASER/FRASER2 software

- Reference annotation of minor intron-containing genes

Procedure:

- Data Preparation

- Process RNA-seq data through standard alignment pipeline

- Generate splice junction counts for all samples

Splicing Outlier Detection

- Run FRASER on cohort to detect significant splicing outliers [13]

- Calculate outlier counts per sample for different splicing types (intron retention, exon skipping, etc.)

Minor Intron Analysis

- Extract minor intron-containing genes from reference [33]

- Calculate proportion of intron retention outliers in MIGs versus major introns

- Identify samples with significant enrichment of MIG intron retention (p < 0.05)

Variant Correlation

- For samples with MIG intron retention enrichment, examine minor spliceosome genes (RNU4ATAC, RNU6ATAC) for rare variants [33]

- Validate suspected variants through Sanger sequencing

Clinical Interpretation

- Correlate molecular findings with clinical presentation

- Compare to known minor spliceopathy phenotypes (e.g., microcephalic osteodysplastic primordial dwarfism) [13]

Expected Results: Identification of individuals with potential minor spliceopathies characterized by excess intron retention in minor intron-containing genes.

Comparative Methodologies

Table 1: RNA-seq Outlier Detection Methods

| Method | Primary Application | Statistical Approach | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Inspection (MDS/PCA) | Initial outlier screening | Dimensionality reduction | Fast, intuitive, requires no specialized tools | Subjective, may miss subtle outliers |

| FRASER/FRASER2 | Splicing outlier detection | Count-based modeling of splicing patterns | Specifically designed for splice defects, good for rare diseases | Computationally intensive, requires large sample sizes |

| OUTRIDER | Expression outlier detection | Negative binomial distribution with autoencoder | Specifically designed for outlier detection, handles confounders | Complex implementation, long run times |

| OutSingle | Expression outlier detection | Log-normal with SVD decomposition | Very fast execution, good performance | Newer method, less extensively validated |

| Z-score approaches | Simple outlier screening | Normal distribution assumption | Very simple to implement | Poor control of confounders, high false positive rate |

Table 2: Outlier Patterns in Rare Disease Contexts

| Outlier Pattern | Potential Biological Meaning | Associated Tools | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excess intron retention in minor introns | Minor spliceosome dysfunction | FRASER, FRASER2 | RNU4atac-opathy disorders (MOPD1, Roifman syndrome) |

| Global splicing outliers | Major spliceosome defects | FRASER, OUTRIDER | Various Mendelian spliceosomopathies |

| Expression outliers in specific pathways | Haploinsufficiency or regulatory defects | OUTRIDER, OutSingle | Tissue-specific genetic disorders |

| Monoallelic expression outliers | Regulatory variants | OUTRIDER, custom approaches | Dominant disorders with cis-regulatory effects |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for RNA-seq Outlier Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| FRASER/FRASER2 software | Splicing outlier detection | Essential for identifying spliceopathies; requires RNA-seq data from multiple samples |

| OUTRIDER package | Expression outlier detection | Uses autoencoder to control for confounders; good for rare disease cohorts |

| OutSingle tool | Rapid expression outlier detection | Fast alternative to OUTRIDER; uses SVD for confounder control |

| PBMC isolation kit | Source of clinical RNA | Minimally invasive tissue source; expresses ~80% of intellectual disability panel genes |

| Cycloheximide | NMD inhibition | Allows detection of nonsense-mediated decay substrates; use during cell culture |

| Reference annotations | Minor intron identification | Essential for identifying minor intron-containing genes (~0.5% of all introns) |

| Salmon or similar | Transcript quantification | Provides count data for downstream outlier analysis |

Workflow Diagrams

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My RNA-seq data shows samples with extreme expression levels for hundreds of genes. Are these technical artifacts I should discard? Historically, such samples were often excluded as technical noise. However, recent research confirms that extreme outlier expression is a biological reality observed across tissues and species, including mice, humans, and Drosophila [11] [34]. These outliers are not purely technical artifacts and can provide valuable biological insights. Before discarding, you should:

- Verify Reproducibility: Check if the outlier pattern is reproducible in independent sequencing runs [11].

- Associate with Biology: Investigate if outlier genes are part of co-regulatory modules or known pathways, such as those involving prolactin and growth hormone [11].

- Check Heritability: Note that most extreme over-expression appears sporadically and is not inherited, which can help distinguish it from effects caused by genetic polymorphisms [11] [34].

Q2: My diagnostic pipeline for a rare disease keeps overlooking causal variants. What is a common type of pathogenic variant I might be missing? Your pipeline may be overlooking splice-disruptive variants. It is estimated that 15–30% of all disease-causing mutations may affect splicing [35] [36]. Standard clinical workflows often focus on variants in protein-coding regions and canonical splice sites, but many pathogenic variants lie in non-coding regions and can disrupt splicing regulation [35]. These include:

- Deep-intronic variants that create cryptic splice sites.

- Synonymous variants within exons that disrupt splicing enhancers or silencers.

- Variants affecting branch points or other regulatory elements [35] [36].

Q3: How can I distinguish a true, biologically relevant splicing outlier from background technical noise? Using dedicated statistical methods for splicing outlier detection is crucial. Tools like FRASER and FRASER2 are designed to identify aberrant splicing events, such as intron retention, from RNA-seq data [13]. A true biological signal often manifests as a coordinated pattern across multiple genes. For instance, an excess of intron retention outliers specifically in minor intron-containing genes (MIGs) can signal a defect in the minor spliceosome, potentially caused by variants in genes like RNU4ATAC [13]. Looking for these transcriptome-wide patterns provides a more robust signature than focusing on single-gene events.

Q4: What is monoallelic expression (MAE), and how can I detect it in my single-cell RNA-seq data? Monoallelic expression (MAE) occurs when a gene is expressed from only one of the two parental alleles [37] [38]. It can be constitutive, as seen in genomically imprinted genes, or random (rMAE), where the choice of allele is stochastic and can vary from cell to cell [37]. To detect it in scRNA-seq data, you need:

- Genotype Information: Whole-genome sequencing data or dense genotyping from the same individual to identify heterozygous single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) [37] [38].

- Allele-Resolved scRNA-seq Data: scRNA-seq data where reads covering these SNVs can be assigned to the maternal or paternal allele.

- Statistical Testing: A statistical framework (e.g., a chi-square test) to identify SNVs with significant allelic expression bias in a population of cells. An allele with a UMI fraction below 5% is often defined as exhibiting MAE [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Investigating Extreme Expression Outliers

Problem: One or more samples in a dataset show extreme over- or under-expression for a large number of genes.

Investigation Workflow:

- Confirm it's not technical: Check standard QC metrics (sequencing depth, RNA quality, adapter contamination) to rule out obvious technical failures.

- Quantify the outliers: Use a conservative statistical cutoff to define outliers. A robust method is Tukey’s fences, defining extreme over-expression outliers (OO) as values above Q3 + 5 × IQR, which corresponds to a very low P-value in a normal distribution [11].

- Analyze the pattern:

Diagram 1: Workflow for investigating extreme expression outliers.

Guide 2: Diagnosing Splicing Defects in Rare Diseases

Problem: A patient with a suspected rare genetic disease has undergone genomic sequencing, but no definitive causative variant has been found.

Investigation Workflow:

- Re-analyze with splicing-aware tools: Re-process genomic data using computational tools designed to predict splice-altering variants, even those in deep intronic or synonymous regions [35] [36].

- Incorporate RNA-seq: If patient tissue (e.g., whole blood) is available, perform RNA-seq.

- Run splicing outlier detection: Use algorithms like FRASER/FRASER2 on the RNA-seq data to identify aberrant splicing events genome-wide [13].

- Look for pathway signatures: Don't just look at single genes. Search for patterns, such as an enrichment of intron retention in minor intron-containing genes, which points to a specific spliceopathy [13].

- Experimental validation: Use RT-PCR or other molecular assays to confirm the predicted splicing defect [36].

Guide 3: Detecting Monoallelic Expression in Single-Cell Data

Problem: Characterizing allele-specific expression patterns in a heterogeneous cell population.

Investigation Workflow:

- Data prerequisites: Obtain scRNA-seq data and matched genotyping (WGS or SNP array) for the same individual to identify informative heterozygous SNVs [37] [38].

- Data processing: Map scRNA-seq reads and assign them to cells and alleles using the genotype information. Filter low-quality SNVs and potential somatic mutations [38].

- Cell type identification: Classify cells into types using standard scRNA-seq clustering methods, as MAE can be cell-type specific [37].

- Statistical testing for MAE:

Diagram 2: Workflow for detecting monoallelic expression in single-cell data.

Quantitative Data Reference

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research on expression and splicing outliers.

| Outlier Category | Quantitative Finding | Context / Method | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extreme Expression | ~3–10% of genes show extreme outlier expression in at least one individual. | Analysis of mouse transcriptome data (48 individuals) using a threshold of Q3 + 5 × IQR. | [11] |

| Extreme Expression | About 72% of genes in a dataset conform to a normal expression distribution; the remainder are potential outliers. | Shapiro-Wilk normality tests on RNA-seq data from multiple species. | [11] |

| Splicing Defects | 15–30% of disease-causing mutations are estimated to affect pre-mRNA splicing. | Review of splicing defects in rare diseases. | [35] [36] |

| Minor Splicing Defects | Identified 5 individuals with excess intron retention in minor intron-containing genes (MIGs) from a cohort of 385. | Splicing outlier analysis with FRASER/FRASER2 on rare disease cohort (GREGoR/UDN). | [13] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Explanation | |

|---|---|---|

| FRASER / FRASER2 | Statistical methods to detect aberrant splicing patterns (like intron retention) from RNA-seq data in an unbiased, transcriptome-wide manner. | [13] |

| ERCC Spike-In Mix | A set of synthetic RNA controls used to standardize RNA quantification, determine the sensitivity, dynamic range, and technical variation of an RNA-seq experiment. | [39] |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random barcodes that label individual mRNA molecules before PCR amplification, allowing for accurate digital counting and correction of PCR bias and errors. | [39] |

| scRNA-seq with Genotyping | A combined approach where single-cell RNA-sequencing is performed alongside whole-genome sequencing of the same individual. This is essential for identifying heterozygous SNVs used to trace monoallelic expression. | [37] [38] |

| Poly-A Selection & rRNA Depletion | Two common methods for library preparation in RNA-seq. Poly-A selection enriches for mRNA in eukaryotes, while rRNA depletion is needed for studying non-polyadenylated RNAs (e.g., lncRNAs) or bacterial transcripts. | [39] |

Practical Implementation: Tools and Techniques for Effective Outlier Detection

What are FRASER and FRASER 2.0, and why are they important for RNA-seq analysis in rare disease research?

FRASER (Find RAre Splicing Events in RNA-seq) is a computational algorithm specifically designed to detect aberrant splicing events from RNA sequencing data. It was developed to address the limitation that approximately 15-30% of variants causing inherited diseases affect splicing, many of which are missed by standard prediction tools that rely on genome sequence alone [28]. The method provides a count-based statistical test for aberrant splicing detection while automatically controlling for latent confounders, which are widespread in RNA-seq data and can substantially affect detection sensitivity [28]. Unlike earlier methods, FRASER captures not only alternative splicing but also intron retention events, which typically doubles the number of detected aberrant events [28].

FRASER 2.0 represents a significant evolution of the original algorithm, introducing a more robust intron-excision metric called the intron Jaccard index that combines alternative donor, alternative acceptor, and intron retention signals into a single value [40]. This improvement came from the observation that FRASER's three original splice metrics were partially redundant and sensitive to sequencing depth [40] [41]. Through optimization of model parameters and filter cutoffs using candidate rare-splice-disrupting variants as independent evidence, FRASER 2.0 calls typically 10 times fewer splicing outliers while increasing the proportion of candidate rare-splice-disrupting variants by 10-fold [40]. This substantial reduction in outlier calls with minimal loss of sensitivity makes FRASER 2.0 particularly valuable for rare disease diagnostics, where reducing false positives is crucial for efficient diagnosis.

Key Methodological Components and Workflow

How do FRASER and FRASER 2.0 technically detect splicing outliers?

Both FRASER and FRASER 2.0 employ a sophisticated computational workflow that transforms raw RNA-seq data into statistically robust outlier calls. The core process involves multiple stages of data processing, normalization, and statistical testing.

Core Splicing Metrics

The original FRASER algorithm computes three primary metrics from RNA-seq data [28]:

- ψ5 metric: Quantifies alternative acceptor usage, defined as the fraction of split reads from an intron of interest over all split reads sharing the same donor.

- ψ3 metric: Quantifies alternative donor usage, analogously defined for the acceptor.

- θ metric: Represents splicing efficiency, defined as the fraction of split reads among split and unsplit reads overlapping a given donor or acceptor site.

FRASER 2.0 introduces a unified metric called the intron Jaccard index (J) that combines these signals [40]. For a given sample i and intron j, it is calculated as:

[ J{ij} = \frac{|D{ij} \cap A{ij}|}{|D{ij} \cup A{ij}|} = \frac{s{ij}}{\sum{d \in Lj} s{id} + \sum{a \in Rj} s{ia} + \sum{t \in {dj,aj}} u{it} - s_{ij}} ]

Where (s{ij}) denotes the count of split reads mapping to intron j, (dj) is the donor site, (aj) is the acceptor site, (Lj) is the set of introns using (dj), (Rj) is the set of introns using (aj), and (u{it}) denotes the count of non-split reads spanning the exon-intron boundary at a splice site t [40].

Denoising Autoencoder for Controlling Confounders

A key innovation in FRASER is the use of a denoising autoencoder to control for technical and biological confounders [28] [40]. Strong covariations in splicing metrics have been observed across RNA-seq datasets, arising from factors such as sex, population structure, batch effects, or variable RNA integrity [28]. The autoencoder models these covariations by fitting a low-dimensional latent space for each tissue separately using principal component analysis (PCA) on logit-transformed splicing metrics [28]. The optimal dimension for this latent space is determined by maximizing the area under the precision-recall curve when calling artificially injected aberrant values [28].

Statistical Testing and Outlier Calling

FRASER uses a beta-binomial distribution to model read counts and identify statistically significant outlier data points [28] [42]. After controlling for confounders via the autoencoder, the method calculates p-values representing the probability that an observed splicing metric deviates significantly from its expected value. These p-values are then corrected for multiple testing using false discovery rate (FDR) control, with default FDR < 0.1 and |Δψ| ≥ 0.3 for significance calling [40].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in FRASER's analysis process:

Comparative Analysis: FRASER vs. FRASER 2.0

What are the key differences between FRASER and FRASER 2.0, and how do they impact performance?

The evolution from FRASER to FRASER 2.0 brought significant improvements in precision and robustness. The table below summarizes the key methodological and performance differences between the two versions:

| Feature | FRASER (Original) | FRASER 2.0 |

|---|---|---|

| Core Metrics | Three partially redundant metrics: ψ5, ψ3, θ [28] | Single unified metric: Intron Jaccard Index [40] |

| Sensitivity to Sequencing Depth | Significant sensitivity observed [40] | Substantially reduced effect of sequencing depth [40] |

| Outlier Call Rate | Higher number of calls per sample [40] | 10x fewer splicing outliers on average [40] |

| Variant Enrichment | Baseline performance | 10x increase in proportion of candidate rare-splice-disrupting variants [40] |

| Intron Retention Detection | Captured through θ metric [28] | Integrated into Jaccard Index alongside other event types [40] |

| Multiple Testing Burden | Higher due to transcriptome-wide approach [40] | Reduced burden; option to test specific gene subsets [40] |

The performance improvements in FRASER 2.0 were validated on large datasets including 16,213 GTEx samples and 303 rare-disease samples, confirming both the reduction in outlier calls and maintenance of high sensitivity [40]. In practical diagnostic applications, FRASER 2.0 recovered 22 out of 26 previously identified pathogenic splicing cases with default cutoffs, and 24 when multiple-testing correction was limited to OMIM genes containing rare variants [40].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Standard Analysis Workflow

What are the key steps for implementing FRASER/FRASER 2.0 in a research pipeline?

The typical workflow for implementing FRASER or FRASER 2.0 involves both computational and analytical steps:

Data Preparation: Process raw RNA-seq data through alignment to generate BAM files. The DROP pipeline (v.1.1.3) is commonly used for count quantification and FraserDataSet creation [40].

Read Counting: Extract split reads and non-split reads using the FRASER package. Split reads are those whose ends align to two separated genomic locations of the same chromosome strand, providing evidence of splicing events [28]. Non-split reads spanning exon-intron boundaries are used for intron retention detection [28].

Quality Control and Filtering: Apply standard filters such as RNA integrity number (RIN) > 5.7, removal of tissues with <100 samples (for large studies), and intron-level filtering (95% of samples with n ≥ 1 read and at least one sample with an intron count ≥20) [40].

Model Fitting: Execute the FRASER algorithm with default parameters (FDR < 0.1, |Δψ| ≥ 0.3, minimal intron coverage ≥ 5 reads) or customized settings based on research goals [40].

Result Interpretation: Analyze outlier calls in the context of known rare variants, gene annotations, and potential clinical relevance.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

What challenges might researchers encounter when using FRASER, and how can they address them?

| Issue | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excessive outlier calls | Inadequate control for confounders; overly lenient thresholds [28] | Use FRASER 2.0; apply stricter filters (e.g., | Δψ | ≥ 0.3); limit testing to OMIM genes with rare variants [40] |

| Low concordance between replicates | Technical batch effects; poor RNA quality [28] | Check RNA integrity (RIN > 5.7); ensure consistent processing; include batch in autoencoder [40] | ||

| Missed validated splicing events | Overly stringent filtering; low sequencing depth [40] | Adjust count thresholds; increase sequencing depth; use FRASER 2.0 for better sensitivity [40] | ||

| Computational performance issues | Large sample sizes; whole transcriptome analysis [40] | Use gene-specific testing mode; increase computational resources; leverage BiocParallel for parallelization [40] [42] | ||

| Inconsistent results across metrics | Partial redundancy between ψ5, ψ3, and θ [40] | Implement FRASER 2.0 with unified Jaccard Index; prioritize events significant across multiple metrics [40] |

What computational tools and resources are essential for implementing FRASER in a research environment?

The table below outlines key resources in the FRASER ecosystem:

| Resource | Function | Implementation Details |

|---|---|---|

| FRASER R Package | Core analysis functionality [42] | Available through Bioconductor; supports aberrant(), calculatePvalues(), results() for key operations [42] |

| DROP Pipeline | Automated RNA-seq quantification and outlier detection [40] | Integrates FRASER with other outlier detection methods; processes BAM to results [40] |

| GTEx Dataset | Reference dataset for expected splicing patterns [28] | 7,842 RNA-seq samples from 48 tissues of 543 donors; provides baseline splicing distribution [28] |

| BiocParallel | Parallel computing framework [42] | Accelerates computation for large datasets; integrated in FRASER package [42] |

| GENCODE Annotation | Reference transcriptome [28] | Release 28 used in original FRASER publication; essential for annotation [28] |

FAQs on FRASER Applications and Limitations

What are the most common questions researchers have about implementing and interpreting FRASER results?

Q1: What types of splicing events can FRASER detect that other tools might miss? FRASER is particularly effective at detecting intron retention events, which are often missed by other splicing detection algorithms [28]. The original FRASER implementation typically doubled the number of detected aberrant events by capturing these retention events [28]. Additionally, FRASER can identify aberrant splicing from novel splice sites detected de novo from the RNA-seq data, not limited to previously annotated sites [28].

Q2: How does FRASER handle different tissue types in large cohort studies? FRASER is designed to model tissue-specific splicing patterns by fitting separate models for each tissue type [28]. In the GTEx analysis, FRASER created tissue-specific splice site maps containing on average 137,058 donor sites and 136,743 acceptor sites per tissue, with distinct covariation structures observed for each tissue [28]. This tissue-specific modeling is crucial as splicing regulation varies significantly across tissues.

Q3: What evidence validates FRASER's performance in diagnostic settings? Multiple studies have validated FRASER's diagnostic utility. In one analysis of rare disease samples, FRASER 2.0 recovered 22 out of 26 previously identified pathogenic splicing cases with default cutoffs [40]. Another study applying FRASER to 385 individuals from rare disease cohorts successfully identified five individuals with excess intron retention outliers in minor intron-containing genes, all of whom harbored rare, bi-allelic variants in minor spliceosome snRNAs [13].

Q4: How does FRASER address the multiple testing problem in transcriptome-wide analyses? FRASER employs beta-binomial testing with false discovery rate (FDR) correction, which reduces the number of calls by two orders of magnitude compared to commonly applied z-score cutoffs [28]. FRASER 2.0 further addresses this by offering an option to select specific genes for testing in each sample instead of a transcriptome-wide approach, which is particularly useful when prior information such as candidate variants is available [40].

Q5: What are the key considerations for sample size when using FRASER? While FRASER can work with smaller sample sizes, its denoising autoencoder benefits from larger cohorts. The fitted encoding dimension for the latent space grows approximately linearly with sample size, resulting in larger encoding dimensions in tissues with more samples [28]. For tissues with limited samples, researchers should consider leveraging cross-tissue resources or adjusting model parameters accordingly.

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between key splicing concepts and FRASER's detection approach:

FRASER and its enhanced version FRASER 2.0 represent specialized algorithms that significantly advance the detection of splicing outliers in RNA-seq data. Through their denoising autoencoder approach, beta-binomial statistical testing, and optimized metrics—particularly the unified intron Jaccard index in FRASER 2.0—these tools address critical challenges in rare disease diagnostics and splicing research. The evolution from FRASER to FRASER 2.0 demonstrates how methodological refinements can dramatically reduce false positive rates while maintaining sensitivity, making these algorithms invaluable for researchers and clinicians seeking to identify pathogenic splicing events in rare disease patients. As RNA-seq continues to play an expanding role in diagnostic settings, FRASER's ability to systematically detect aberrant splicing events positions it as an essential component in the modern genomic analysis toolkit.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary function of the OUTRIDER tool? OUTRIDER (Outlier in RNA-Seq Finder) is a statistical algorithm designed to identify aberrantly expressed genes in RNA sequencing data. It uses an autoencoder to model read-count expectations based on gene covariation and identifies outliers as read counts that significantly deviate from a negative binomial distribution. It is particularly useful for rare disease diagnostic platforms [43].

When should I use a comparative analysis framework like CARE instead of OUTRIDER? The CARE (Comparative Analysis of RNA Expression) framework is particularly beneficial when analyzing ultra-rare cancers or diseases where no actionable mutations are found through DNA profiling alone. It identifies targetable overexpression genes and pathways by comparing a patient's tumor RNA-Seq profile to large compendiums of tumor data (e.g., over 11,000 samples). OUTRIDER is generally used for identifying aberrant expression within a dataset, while CARE is for placing a single sample in a broad disease context to nominate treatments [44].

My analysis has identified a list of outlier genes. What is the critical next step before concluding they are biologically relevant? Validation is a crucial next step. The golden standard is to validate findings with wet lab experiments. If that is not possible, you should use multiple data types and sources. For example, you can validate RNA-seq outliers with protein-level data (e.g., Western blot) or use publicly available datasets to see if the same conclusions are supported. Over-interpreting results without considering biological relevance is a common pitfall [45] [9].

What is a major statistical pitfall when performing differential expression analysis on single-cell RNA-seq data? A common mistake is grouping all cells from each condition together and performing differential gene expression tests at the individual cell level. The cells from each sample are not independent, and using a large number of cells can lead to artificially small p-values. The recommended best practice is to use a pseudo-bulk approach instead [45].

How does the choice of comparator cohort impact outlier detection in gene expression? The utility of RNA-Seq for identifying therapeutic targets is highly dependent on the comparator cohorts. Using large, uniformly processed datasets from multiple institutions and studies allows for the identification of molecularly similar tumors that may not be expected based on tumor histology alone. The impact of cohort selection on outlier detection is significant, and personalized comparator cohorts improve the identification of relevant overexpression outliers [44].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Non-uniform p-value distribution in outlier detection

- Problem: When analyzing RNA-seq data to infer differential expression or outliers, the p-value distribution for null-hypothesis data is not uniform, leading to inaccurate estimates of False Discovery Rates (FDRs). This can cause a loss of power to detect true differential expression [46].

- Solution:

- Tool Selection: Use tools that accurately control for FDR. Studies have shown that the QLSpline implementation of QuasiSeq performs well in achieving a low and accurately estimated FDR when there are at least four biological replicates per condition. edgeR and DESeq2 are also among the next best-performing packages [46].

- Algorithmic Adjustment: For two-class datasets with a sufficient number of biological replicates (approximately 6 or more), an extension called Polyfit can be used with edgeR or DESeq. Polyfit adapts the Storey-Tibshirani procedure to address the problem of a non-uniform null p-value distribution [46].

Issue 2: Low diagnostic yield in RNA-driven analysis of rare diseases

- Problem: When using blood RNA-seq for rare disease diagnosis in cases where no candidate variants were found from prior exome/genome sequencing (ES/GS), the diagnostic uplift from a purely RNA-driven approach can be modest (e.g., 2.7%) [47].

- Solution:

- Strategy Change: Adopt an RNA-complementary approach instead of an RNA-driven one. Use RNA-seq to refine findings from DNA-sequencing, particularly for interpreting Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS). This strategy has been shown to provide a much higher diagnostic uplift (60% in cases with candidate splicing VUS) [47].

- Pipeline Application: Employ a standardized pipeline like DROP for the detection of aberrant expression (AE) and aberrant splicing (AS) outliers. In the "RNA-complementary" approach, the OUTRIDER module of the DROP pipeline is often used specifically for cases where no aberrant splicing is detected, as abnormal transcripts may be degraded and thus mask splicing outliers [47].

Issue 3: Over-interpretation of data visualization

- Problem: Incorrectly interpreting the distance between points on a UMAP plot as a measure of biological similarity or difference [45].

- Solution:

- Remember that UMAP is a non-linear dimension reduction technique. The algorithm prioritizes the preservation of local structure over global distances. Therefore, the distance between clusters should not be over-interpreted. UMAP is excellent for visualization but should not be used for quantitative conclusions about relationships between distant cell clusters [45].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Key RNA-seq Outlier Detection Tools and Their Applications

| Tool / Framework Name | Primary Function | Statistical Foundation | Key Application Context | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OUTRIDER | Detects aberrantly expressed genes within a dataset | Autoencoder for covariation control, Negative Binomial distribution for outlier calling | Rare disease diagnostics; identifying aberrant expression in a cohort | [43] |

| CARE Framework | Identifies targetable overexpression by comparing a sample to large tumor compendiums | Z-score based outlier detection against personalized comparator cohorts | Precision oncology for rare pediatric and adult cancers; treatment nomination | [44] |

| DROP Pipeline | Detects Aberrant Expression (AE) and Aberrant Splicing (AS) | Multiple; incorporates OUTRIDER for AE analysis | Rare disease diagnostics, particularly following exome/genome sequencing | [47] |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Differential Expression Packages

This table summarizes findings from a comparative analysis of several R packages for differential expression analysis, based on their ability to accurately estimate the False Discovery Rate (FDR) [46].

| Software Package | Model / Foundation | Recommended Minimum Replicates | Performance Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| QLSpline (QuasiSeq) | Quasi-likelihood with information sharing across genes | 4 | Achieves a low FDR that is accurately estimated, but has a slow run time. |

| edgeR | Negative Binomial model | Not specified | Next best performing package after QLSpline. |

| DESeq2 | Negative Binomial model with shrinkage estimation | Not specified | Next best performing package after QLSpline. |

| Polyfit (with DESeq) | Negative Binomial model with adapted FDR procedure | ~6 | Improves DESeq performance with sufficient replicates, making it comparable to edgeR/DESeq2. |

OUTRIDER Algorithm Workflow

CARE Framework Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| PAXgene Blood RNA Tube | Stabilizes RNA in whole blood samples immediately upon drawing, ensuring an accurate representation of the transcriptome for rare disease studies [47]. |