RNA-seq vs Microarray: A Modern Guide to Gene Expression Analysis for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of bulk RNA sequencing and microarray technologies for researchers and drug development professionals.

RNA-seq vs Microarray: A Modern Guide to Gene Expression Analysis for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of bulk RNA sequencing and microarray technologies for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, methodological workflows, and data analysis to guide platform selection. The content explores key advantages of RNA-seq, including its wider dynamic range and ability to detect novel transcripts, while also examining contexts where microarrays remain viable. Drawing from recent studies and systematic evaluations, the article delivers evidence-based insights for optimizing transcriptomic studies, from experimental design to data interpretation, supporting informed decision-making in biomedical and clinical research.

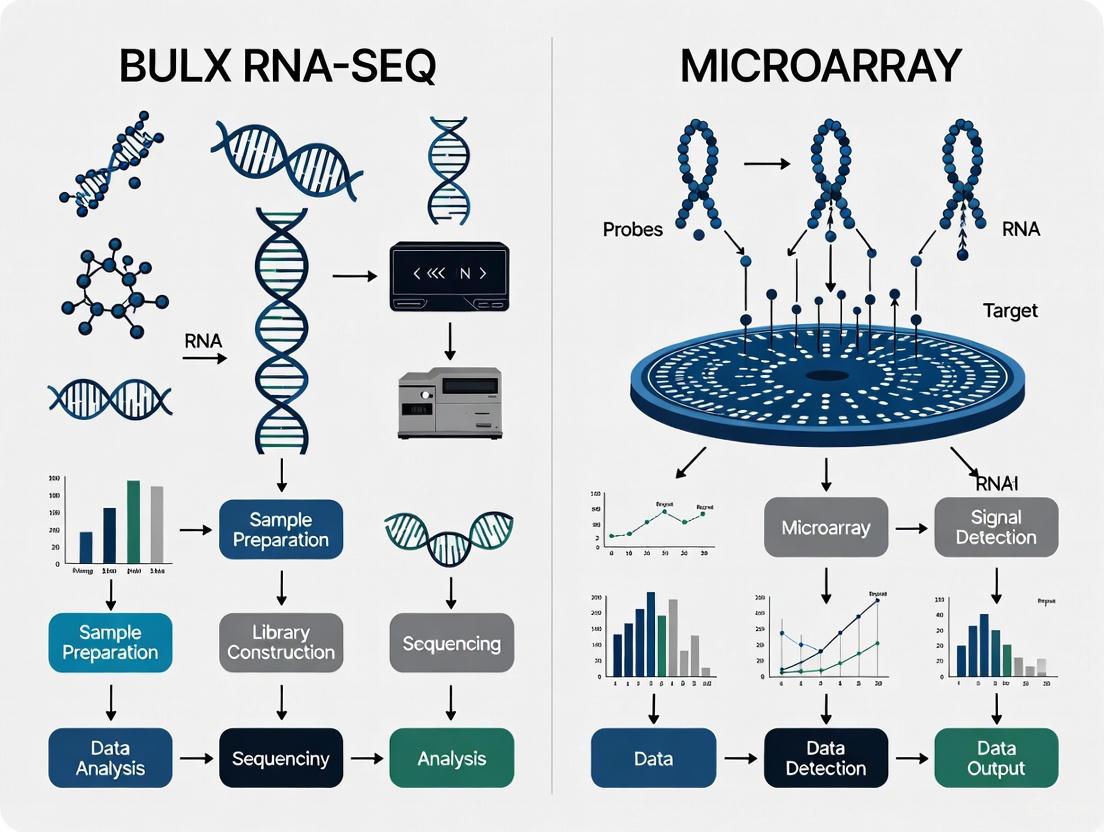

Core Principles: Understanding the Fundamental Differences Between RNA-seq and Microarrays

In the field of transcriptomics, two fundamentally distinct technological paradigms have enabled researchers to profile gene expression on a genome-wide scale: hybridization-based and sequencing-based methods. Hybridization-based technologies, primarily represented by DNA microarrays, determine expression levels by measuring the intensity of fluorescent signals when labeled nucleic acids bind to complementary probes fixed on a solid surface [1] [2]. In contrast, sequencing-based technologies, most notably RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq), directly determine the nucleotide sequence of cDNA molecules through massive parallel sequencing, providing digital counts of transcript abundance [3] [4].

These approaches operate on different biochemical principles, offer distinct advantages and limitations, and have followed contrasting trajectories in their adoption and development. Microarrays, developed earlier, maturely standardized, and more cost-effective, dominated the field for over a decade [3]. RNA-Seq, emerging later, offers a more flexible and comprehensive view of the transcriptome without relying on predefined probes [4]. Within the context of bulk RNA-seq versus microarray comparison research, understanding their core differences is essential for selecting the appropriate tool for specific biological questions, especially in drug discovery and development where accurate transcriptome profiling can identify novel therapeutic targets and biomarkers [5] [6].

Core Technological Principles and Workflows

The Hybridization-Based Approach (Microarrays)

The fundamental principle of microarray technology involves the specific base-pairing (hybridization) of fluorescently-labeled cDNA fragments from a sample to DNA probes attached to a solid surface in a predefined array.

Diagram 1: Microarray experimental workflow.

The detailed experimental protocol for microarrays typically follows these steps [3]:

- Sample Preparation & cDNA Synthesis: Total RNA is extracted from biological samples. Using reverse transcriptase and a T7-linked oligo(dT) primer, single-stranded cDNA is synthesized, which is then converted to double-stranded cDNA.

- Labeling: The double-stranded cDNA serves as a template for in vitro transcription (IVT) to synthesize complementary RNA (cRNA). This reaction incorporates biotinylated UTP and CTP, thereby labeling the cRNA.

- Hybridization: The biotin-labeled cRNA is fragmented and hybridized to the microarray chip, which contains hundreds of thousands of specific DNA probes. Hybridization occurs under controlled conditions (e.g., 45°C for 16 hours).

- Washing and Staining: After hybridization, the chip is washed to remove non-specifically bound material. It is then stained with a fluorescent dye (e.g., streptavidin-phycoerythrin) that binds to the biotin labels.

- Signal Detection: The chip is scanned with a laser, and the fluorescence intensity at each probe spot is measured. This intensity is proportional to the abundance of the corresponding transcript in the original sample.

- Data Processing: The raw image files are processed to generate cell intensity files. Background adjustment, quantile normalization, and summarization of probe-level data are performed using algorithms like the Robust Multi-chip Average to obtain normalized gene expression values.

The Sequencing-Based Approach (RNA Sequencing)

RNA-Seq abandons the concept of hybridization to predefined probes in favor of directly sequencing the entire population of cDNA molecules.

Diagram 2: RNA-seq experimental workflow.

The standard protocol for bulk RNA-Seq involves [3] [7]:

- RNA Extraction and Selection: Total RNA is extracted. Messenger RNA (mRNA) is typically enriched either by oligo(dT) magnetic beads that capture poly-adenylated transcripts or by ribosomal RNA depletion.

- Library Preparation: The enriched RNA is fragmented. cDNA is synthesized from the fragments, and then sequencing adapters are ligated to both ends. This creates a "library" of molecules ready for sequencing.

- Massively Parallel Sequencing: The library is loaded onto a sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina). The process involves amplification and cyclic sequencing-by-synthesis, generating millions to billions of short sequence reads.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Pre-processing & Alignment: Raw sequencing reads are quality-checked and trimmed. They are then aligned to a reference genome or transcriptome.

- Quantification: The number of reads mapped to each gene or transcript is counted, generating a digital expression value (e.g., read counts).

- Normalization & Differential Expression: Read counts are normalized to account for factors like sequencing depth and gene length. Statistical models (e.g., in DESeq2) are then applied to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between sample groups.

Performance Comparison: Key Metrics and Experimental Data

Direct comparisons between microarrays and RNA-Seq have been the subject of numerous studies. The table below synthesizes quantitative and qualitative findings from benchmark reports and reviews.

Table 1: Performance comparison of hybridization-based microarrays and RNA-Seq.

| Feature | Hybridization-Based (Microarray) | Sequencing-Based (RNA-Seq) | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Analog fluorescence intensity | Digital read counts | [1] [4] |

| Dynamic Range | ~10³ (limited by background & saturation) | >10⁵ (wide, virtually unlimited) | [4] |

| Specificity & Sensitivity | Lower, especially for low-abundance transcripts | Higher, can detect more DEGs, including low-expression genes | [4] [7] |

| Ability to Detect Novel Features | No; limited to predefined probes on the array | Yes; can identify novel transcripts, isoforms, gene fusions, SNPs, and indels | [4] |

| Reproducibility | High correlation across technical replicates on same platform | High correlation, but inter-laboratory variation can be significant | [1] [7] |

| Typical Workflow Duration | Shorter, streamlined | Longer, more complex steps | Implied by [8] [9] |

| Cost per Sample | Generally lower | Generally higher | [3] |

| Data Analysis | Well-established, standardized methods | Complex, computationally intensive, evolving tools | [3] [7] |

| Concordance with "Ground Truth" | Moderate to high correlation with qPCR for well-expressed genes | High correlation with qPCR and spike-in controls; more accurate for absolute quantification | [7] |

A large-scale, real-world benchmarking study across 45 laboratories highlighted significant inter-laboratory variations in RNA-Seq performance, particularly when detecting subtle differential expression between samples with very similar transcriptome profiles [7]. This study emphasized that factors like mRNA enrichment protocol, library strandedness, and the choice of bioinformatics pipelines are major sources of variation. In contrast, microarray data from different platforms generally show high correlations, though concordance with sequencing-based methods like MPSS is only moderate [1] [2]. The discrepancies are often attributed to genes with low-abundance transcripts and technological limitations inherent to each method [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key research reagents and their functions in transcriptomics.

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Technology |

|---|---|---|

| Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads | Enriches for polyadenylated mRNA from total RNA | RNA-Seq |

| Biotinylated UTP/CTP | Labels cRNA for fluorescence detection after hybridization | Microarray |

| GeneChip PrimeView Array | A predefined microarray chip containing probes for human gene expression | Microarray |

| Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep Kit | Library preparation kit for creating sequencing-ready RNA libraries | RNA-Seq |

| EZ1 RNA Cell Mini Kit | Automated purification of total RNA from cell lysates | Both |

| External RNA Control Consortium (ERCC) Spike-Ins | Synthetic RNA controls added to samples to assess technical performance and accuracy | Both (QC) |

| DNase I | Digests contaminating genomic DNA during RNA purification | Both |

| Streptavidin-Phycoerythrin | Fluorescent dye that binds to biotin for signal detection | Microarray |

Hybridization-based microarrays and sequencing-based RNA-Seq are both powerful and important tools for transcriptome profiling [1] [2]. The choice between them is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather depends on the specific research goals, budget, and technical expertise.

For well-defined projects focused on profiling the expression of known genes, where cost-effectiveness, streamlined workflow, and access to well-established public databases are priorities, microarrays remain a viable and robust choice [3]. However, for discovery-oriented research that requires a comprehensive, unbiased view of the transcriptome, including the detection of novel transcripts, splice variants, and other genetic variations, RNA-Seq is the unequivocal leading technology [4].

The evolution of transcriptomics continues with the rise of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), which resolves cellular heterogeneity and is transforming target identification and validation in drug discovery [5]. Furthermore, the application of artificial intelligence to analyze large-scale pharmacotranscriptomic data is creating a new paradigm for drug screening and mechanism-of-action studies [6]. As sequencing costs decrease and analytical methods become more standardized and robust, RNA-Seq and its derivatives are poised to become even more central to biological and clinical research.

The choice of transcriptome profiling technology is a fundamental decision in genomics research, influencing the depth, accuracy, and scope of biological insights. For years, gene expression microarrays were the cornerstone of transcriptomics. The advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) introduced RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), which provides a fundamentally different approach to measuring RNA abundance. This guide offers an objective, data-driven comparison of these two platforms, focusing on the critical performance parameters of dynamic range, sensitivity, and specificity. Understanding these technical specifications is essential for researchers and drug development professionals to select the optimal technology for their experimental aims, whether for discovery-driven research or targeted clinical assay development.

The core distinction between microarrays and RNA-seq lies in their underlying mechanism for detecting RNA molecules. Microarrays are a hybridization-based technology that relies on fluorescence. In this process, RNA is extracted and reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA), which is labeled with fluorescent dyes. This labeled cDNA is then hybridized to pre-defined probes immobilized on a solid surface. The resulting fluorescence intensity at each probe spot is measured, and this signal serves as a proxy for the original RNA abundance [10].

In contrast, RNA-seq is a sequencing-based technology that provides digital, countable data. After RNA extraction, a library is constructed by fragmenting the RNA and converting it into cDNA. These cDNA fragments are then sequenced in a high-throughput manner using NGS platforms. The generated sequence reads are digitally mapped to a reference genome or transcriptome, and the abundance of each transcript is quantified by counting the number of reads that align to it [4] [10].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental differences in these workflows:

Direct Technical Comparison

The differing principles of microarrays and RNA-seq lead to significant disparities in their technical performance. The following table summarizes the key specifications for dynamic range, sensitivity, and specificity based on empirical comparisons.

Table 1: Technical Specifications of Microarray vs. RNA-seq

| Performance Parameter | Microarray | RNA-Seq | Experimental Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Range | ~10³ [4] | >10⁵ [4] | Broader linear range without upper saturation or background noise limits [4]. |

| Sensitivity | Lower, especially for low-abundance transcripts [4] | Higher; can detect rare and low-abundance transcripts (e.g., single transcripts per cell) [4] | RNA-seq identifies a higher percentage of differentially expressed genes (DEGs), particularly those with low expression [4] [11]. |

| Specificity | Limited by cross-hybridization between related sequences [3] | High; precise mapping of reads to the genome allows discrimination between homologous genes and isoforms [4] | RNA-seq provides improved specificity for detecting transcripts and specific isoforms [4]. |

| Novel Transcript Detection | Restricted to known, pre-defined probes [4] | Unbiased discovery of novel transcripts, splice variants, and gene fusions [4] [12] | RNA-seq can identify novel exons and transcript isoforms not annotated in reference databases [12]. |

Experimental Evidence and Validation

Concordance in Differential Expression and Pathway Analysis

Despite the superior technical performance of RNA-seq, studies have shown that both platforms can yield concordant biological interpretations under specific conditions. A 2025 toxicogenomics study compared microarray and RNA-seq using two cannabinoids, cannabichromene (CBC) and cannabinol (CBN). While RNA-seq identified a larger number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with a wider dynamic range, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed that the functions and pathways impacted by chemical exposure were equivalent between the platforms. Furthermore, transcriptomic point of departure (tPoD) values derived from benchmark concentration (BMC) modeling were on the same level for both CBC and CBN, indicating similar utility for quantitative risk assessment [3].

Another 2025 study analyzing human whole blood samples from youth with and without HIV also found a high correlation (median Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.76) in gene expression profiles between the platforms. Although RNA-seq identified 2,395 DEGs compared to 427 from microarrays, there was a statistically significant concordance in the 223 shared DEGs. Pathway analysis further showed that while RNA-seq perturbed 205 pathways versus 47 for microarrays, 30 key pathways were shared. The study concluded that with consistent non-parametric statistical methods, both platforms provide highly concordant results for downstream functional analysis [11] [13].

Clinical Endpoint Prediction

A critical large-scale analysis by the MAQC-III/SEQC consortium systematically compared the power of RNA-seq and microarray-based models for clinical endpoint prediction using 498 neuroblastoma samples. The study found that while RNA-seq vastly outperformed microarrays in characterizing the transcriptome (revealing >48,000 genes and 200,000 transcripts versus 21,101 genes on the microarray), this did not translate into superior predictive models. The development of 360 predictive models for six clinical endpoints demonstrated that prediction accuracies were most strongly influenced by the nature of the endpoint itself. The technological platform (RNA-seq vs. microarrays) did not significantly affect model performance. This suggests that for well-defined predictive tasks based on known transcript biomarkers, microarrays remain a viable tool [12].

Experimental Design and Protocols

Sample Size Considerations for RNA-seq

Robust gene expression analysis requires adequate sample sizes to minimize false positives and maximize true discoveries. A large-scale 2025 murine study, which profiled organs from wild-type and heterozygous mice with a maximum sample size of N=30 per group, provided empirical guidance. The study demonstrated that experiments with N=4 or fewer samples are highly misleading due to high false positive rates and poor sensitivity. The results indicated that a minimum of 6-7 biological replicates per group is required to consistently decrease the false positive rate below 50% and achieve detection sensitivity above 50% for a 2-fold expression difference cutoff. The study strongly recommended a sample size of 8-12 for significantly better performance, noting that "more is always better" for both metrics [14].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Platforms for Transcriptomic Profiling

| Category | Item | Function/Description | Example Products/Brands |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation | Total RNA Kit | Purifies high-quality, intact RNA from biological samples. | PAXgene Blood RNA Kit [11], RNeasy Plus Mini Kit [15] |

| Sample Quality Control | Bioanalyzer | Assesses RNA Integrity Number (RIN) to ensure sample quality. | Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer [3] [15] |

| Microarray Platform | Oligonucleotide Array | Contains pre-defined probes for hybridization-based expression profiling. | GeneChip Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array [11], Agilent 44k/PrimeView Arrays [3] [12] |

| RNA-seq Library Prep | Stranded mRNA Kit | Prepares sequencing libraries from RNA, including poly-A selection and adapter ligation. | Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep [3], NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit [11] |

| Sequencing Platform | NGS Sequencer | Performs high-throughput sequencing of cDNA libraries. | Illumina HiSeq [11] [15] |

| Data Analysis | Bioinformatics Tools | For processing, normalizing, and analyzing raw data (e.g., CEL files, FASTQ files). | Affymetrix TAC Software [3], R/Bioconductor (e.g., DESeq2) [13] [15], Trimmonatic, FASTQC [11] [15] |

RNA-seq Data Analysis Pipeline

The analysis of RNA-seq data is complex, with multiple algorithmic options at each step that can influence results. A comprehensive 2020 study systematically evaluated 192 alternative pipelines. The following diagram outlines a generalized, robust RNA-seq workflow based on its findings, highlighting key steps where methodological choices are critical [15].

The choice between microarray and RNA-seq is not a simple matter of one technology being universally "better" than the other. Instead, the decision should be guided by the specific research goals, budget, and bioinformatics capacity.

Choose RNA-seq when the research aims require unbiased discovery, such as identifying novel transcripts, splice variants, gene fusions, or non-coding RNAs. It is also the preferred technology for profiling organisms without a well-annotated genome, for projects requiring the widest possible dynamic range and sensitivity for low-abundance transcripts, and when digital counting and low background are priorities [4] [12].

Microarrays remain a viable and pragmatic choice for well-defined applications where the goal is to profile the expression of known genes in a high-throughput, cost-effective manner. This includes large-scale studies focused on validated gene signatures, clinical endpoint prediction where models have already been established, and targeted toxicogenomics applications like concentration-response modeling, where it has been shown to perform equivalently to RNA-seq for deriving points of departure [3] [12].

For many research programs, a complementary approach is highly effective. Microarrays can be used for initial large-scale screening due to their lower cost and simpler data analysis, while RNA-seq can be employed for deeper investigation and discovery on select samples. As the cost of sequencing continues to decline, RNA-seq is undoubtedly the future of transcriptomics. However, the vast repositories of high-quality legacy microarray data and its continued utility for targeted applications ensure its relevance for the foreseeable future [11] [13].

A critical challenge in modern genomics is the accurate characterization of the complete transcriptome. For years, microarray technology was the standard for gene expression profiling, but its dependence on predefined probes fundamentally limited its discovery potential. The advent of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has revolutionized the field, offering an unbiased method that dramatically enhances the ability to detect novel transcripts and genetic variants. This guide objectively compares the performance of these two technologies, providing supporting experimental data to underscore RNA-seq's superior discovery power.

Experimental Evidence and Performance Comparison

The superior discovery power of RNA-seq is not merely theoretical; it is consistently demonstrated in direct, head-to-head comparative studies and in applications requiring deep transcriptome characterization.

Quantitative Comparison: RNA-seq vs. Microarray

The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies, highlighting the distinct advantages of RNA-seq.

| Performance Metric | Microarray | RNA-seq (Short-Read) | Long-Read RNA-seq (lrRNA-seq) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Novel Transcript Detection | Limited to pre-designed probes; cannot discover novel transcripts [4]. | Can identify novel transcripts, splice junctions, and gene fusions [16] [4]. | Excellent; ideal for discovering full-length isoforms and complex splice variants [17] [18] [19]. |

| Dynamic Range | Limited (~10³), constrained by background noise and signal saturation [4]. | Wide (>10⁵), due to digital counting of reads [4]. | Wide; effective for quantifying transcript abundance across a broad range [18]. |

| Variant Detection | Cannot detect sequence-level variants (SNVs, indels) [4]. | Can detect single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and insertions/deletions (indels) [16] [4]. | Excellent for detecting expressed mutations and linking them to specific transcript isoforms [16] [19]. |

| Data from Recent Studies | In a 2025 toxicogenomic study, microarrays identified fewer DEGs with a narrower dynamic range compared to RNA-seq [3]. | A 2025 multi-center study highlighted RNA-seq's utility for clinical diagnostics, though it also noted inter-laboratory variations [7]. | A 2024 benchmark study found lrRNA-seq effectively reconstructs full-length transcripts, with longer, more accurate reads improving detection [18]. A 2025 study identified ~47,000 novel isoforms in human blood [17]. |

Case Studies in Discovery

Revealing the "Dark Transcriptome": A 2025 study using long-read RNA-seq on human whole blood from healthy individuals identified an average of about 46,000 genes and 185,000 isoforms using the GRCh38 reference genome. Strikingly, approximately 90,000 of these isoforms (47%) were novel, previously unannotated transcripts. This study underscores lrRNA-seq's power to expand our map of the human transcriptome, a feat impossible with microarray technology [17].

Uncovering Transcript-Specific Regulation in Neurons: Research employing nanopore long-read sequencing in human-derived cortical neurons, induced pluripotent stem cells, and fibroblasts uncovered extensive transcript diversity, with over 15,000 transcripts identified in neurons. The analysis revealed 35,519 differential transcript expression events and 5,135 differential transcript usage events across cell types. This detailed view exposed transcript-specific changes in disease-relevant genes like APP (Alzheimer's disease) and KIF2A (neuronal migration disorders), which are obscured in traditional gene-level expression analyses [19].

Bridging the DNA-Protein Divide in Oncology: Targeted RNA-seq has proven its clinical utility by identifying expressed mutations that are missed or unverified by DNA sequencing alone. In one study, RNA-seq provided functional evidence that allowed for the reclassification of variants found by exome and genome sequencing in a significant number of cases. It uniquely identified variants with high pathological relevance, demonstrating its power to uncover clinically actionable mutations that DNA-based methods may suggest but cannot confirm are expressed [16] [20].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure the reproducibility of the powerful results cited above, here are the detailed methodologies from key studies.

Protocol 1: Long-Read RNA-seq for Novel Isoform Discovery in Whole Blood

This protocol is adapted from a 2025 study that identified thousands of novel isoforms in human blood [17].

- 1. RNA Extraction: Collect peripheral whole blood in PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes. Extract total RNA using the PAXgene Blood RNA Kit.

- 2. RNA Quality Control: Assess RNA integrity using an Agilent Bioanalyzer with the RNA 6000 Nano Kit. Confirm RNA Integrity Number (RIN) ≥7 before proceeding.

- 3. cDNA Synthesis & Amplification: Synthesize and amplify cDNA from total RNA using the Iso-Seq Express 2.0 kit (PacBio).

- 4. SMRTbell Library Preparation: Ligate SMRTbell adapters to the 5' and 3' ends of the prepared cDNA using the SMRTbell prep kit 3.0 (PacBio).

- 5. Sequencing: Sequence the cDNA libraries on a PacBio Sequel IIe system.

- 6. Bioinformatics Analysis:

- Alignment: Map raw PacBio reads to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38 or T2T-CHM13) using the

pbmm2aligner. - Isoform Identification: Process aligned data with the

Isoseqbioinformatics suite to identify and classify full-length isoforms. - QC and Annotation: Use tools like

SQANTI3for quality control and annotate isoforms against a reference transcriptome (e.g., from UCSC Genome Browser).

- Alignment: Map raw PacBio reads to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38 or T2T-CHM13) using the

Protocol 2: Targeted RNA-seq for Expressed Mutation Detection

This protocol is based on a 2025 study that used targeted RNA-seq to complement DNA-based cancer mutation panels [16].

- 1. RNA Library Preparation: Prepare sequencing libraries from total RNA using targeted RNA-seq panels (e.g., Agilent Clear-seq or Roche Comprehensive Cancer panels). These panels are designed with probes to enrich for genes of interest and often include exon-exon junction spanning probes.

- 2. Sequencing: Perform high-depth sequencing on the enriched libraries using a next-generation sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina).

- 3. Bioinformatics Analysis for Variant Calling:

- Alignment: Map sequencing reads to the human reference genome.

- Variant Calling: Utilize multiple callers (e.g., VarDict, Mutect2, LoFreq) in a consolidated pipeline to maximize sensitivity.

- Filtering: Apply stringent filters based on variant allele frequency (VAF ≥2%), total read depth (DP ≥20), and alternative allele depth (ADP ≥2) to control the false positive rate.

Workflow and Relationship Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the foundational workflow of RNA-seq and the key technological differences that underpin its superior discovery power compared to microarrays.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful transcriptome discovery relies on a suite of specialized reagents and computational tools. The table below lists key solutions used in the featured experiments.

| Item Name | Function/Benefit | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| PacBio Iso-Seq Express 2.0 Kit | Enables synthesis of high-quality cDNA for long-read sequencing, facilitating full-length transcript capture. | Generating sequencing-ready SMRTbell libraries from blood RNA for novel isoform discovery [17]. |

| Oxford Nanopore Technology | Provides a platform for direct RNA and cDNA sequencing, producing very long reads that span entire transcripts. | Profiling transcriptomes of cortical neurons to analyze differential transcript usage [19]. |

| Targeted RNA-seq Panels | Probe sets designed to enrich for specific genes/transcripts of interest, allowing for deeper coverage and more sensitive variant detection. | Complementing DNA-seq results in cancer samples to identify and validate expressed mutations [16]. |

| ERCC RNA Spike-In Controls | A set of synthetic RNA molecules at known concentrations used to assess technical performance, accuracy, and dynamic range of the RNA-seq assay. | Serving as built-in truth for benchmarking in multi-center RNA-seq studies [7]. |

| SQANTI3 | A comprehensive computational tool for the quality control, classification, and annotation of long-read transcripts. | Classifying and filtering identified isoforms as known or novel after long-read sequencing [17]. |

The collective evidence firmly establishes that RNA-seq, particularly long-read sequencing, offers a transformative advantage over microarrays for the discovery of novel transcripts and variants. Its unbiased nature, wider dynamic range, and single-base resolution make it an indispensable tool for advancing genomic research and precision medicine.

For researchers aiming to maximize discovery power, the following best practices are recommended:

- Prioritize Long-Read Sequencing for projects where the primary goal is the discovery of novel isoforms, the resolution of complex splice variants, or the accurate quantification of transcript usage [18] [19].

- Utilize Targeted RNA-seq Panels in a clinical or diagnostic setting to achieve high sensitivity for detecting expressed mutations in specific genes of interest, thereby bridging the gap between DNA findings and protein function [16].

- Incorporate Spike-In Controls and use standardized reference materials, such as those from the Quartet project, to ensure technical accuracy and enable meaningful cross-laboratory comparisons, especially when detecting subtle differential expression [7].

- Leverage Specialized Bioinformatics Pipelines that are tailored for the specific sequencing technology and analytical goal, as the choice of alignment, quantification, and differential expression tools significantly impacts results [7] [21].

In the evolving landscape of transcriptomics, next-generation RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has emerged as a powerful tool with unprecedented discovery power. Yet, within this context of technological advancement, microarray technology maintains distinct advantages in specific, well-defined research scenarios. The established strength of microarray standardization, coupled with its cost-effectiveness and robust analytical frameworks, makes it a compelling choice for applications where detecting predefined transcripts is sufficient and operational efficiency is paramount. This guide objectively examines the performance characteristics of both platforms, providing researchers with data-driven insights to inform their experimental design.

Key Strengths of Microarray Technology

Proven Standardization and Analytical Maturity

Microarray technology benefits from decades of development, resulting in a highly standardized ecosystem.

- Established Standards: Initiatives like the Microarray Gene Expression Data Society (MGED) have produced consensus standards for data reporting (MIAME), analysis, and interpretation, ensuring reproducibility across laboratories [22].

- Mature Bioinformatics: Data processing pipelines, such as the Robust Multi-array Average (RMA) algorithm, are well-established and widely validated, reducing analytical variability [3] [23].

- Regulatory Familiarity: The long-standing use of microarrays has fostered comfort with the technology in regulatory contexts for risk assessment of chemicals and pharmaceuticals [3].

Cost-Effectiveness and Operational Efficiency

For large-scale studies with constrained budgets, microarrays offer significant practical advantages.

- Lower Sequencing Costs: The per-sample cost of microarrays is generally lower than that of RNA-seq, making them suitable for high-throughput screening applications [3].

- Reduced Data Storage and Computational Demands: Microarray data files are substantially smaller and require less computational power for processing and analysis compared to the vast datasets generated by RNA-seq [3] [12].

Equivalent Performance in Targeted Applications

Contrary to common assumption, microarrays can perform on par with RNA-seq for specific, targeted research goals.

- Clinical Endpoint Prediction: A landmark study on 498 neuroblastoma samples found that predictive models for clinical outcomes performed similarly regardless of whether they were based on microarray or RNA-seq data. The nature of the clinical endpoint itself was a far more significant factor than the technology platform [24] [12].

- Pathway Analysis in Toxicogenomics: Research on cannabinoids demonstrated that while RNA-seq identified more differentially expressed genes, functional pathway analysis through Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) yielded equivalent biological insights from both platforms [3].

- Concentration-Response Modeling: In quantitative toxicogenomics, transcriptomic point of departure (tPoD) values derived from microarray and RNA-seq data were comparable, affirming microarray's utility for benchmark concentration (BMC) modeling [3].

Head-to-Head Technology Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Microarray and RNA-Seq Technologies

| Feature | Microarray | RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Hybridization-based with predefined probes [10] | Sequencing-based with direct cDNA sequencing [10] |

| Prior Sequence Knowledge Required | Yes [4] [10] | No [4] [10] |

| Dynamic Range | ~10³ [4] | >10⁵ [4] |

| Ability to Detect Novel Transcripts | No [4] | Yes (e.g., novel genes, isoforms, fusions) [4] [12] |

| Sensitivity for Low-Abundance Transcripts | Limited by background noise and saturation [4] [23] | High; can be improved by increasing sequencing depth [4] [23] |

| Typical Cost per Sample | Lower [3] | Higher |

| Data Output & Complexity | Smaller data size, simpler analysis [3] | Large, complex data requiring substantial storage and computing [3] |

| Standardization & Established Workflows | High; well-established standards and pipelines [3] [22] | Evolving standards and methodologies [22] |

Table 2: Experimental Evidence from Direct Comparative Studies

| Study Context | Key Finding on Microarray Performance | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Endpoint Prediction (Neuroblastoma) | Microarray-based classifiers performed similarly to RNA-seq-based models for predicting patient outcomes. | [24] [12] |

| Toxicogenomics (Cannabinoids) | Transcriptomic points of departure (tPoD) and enriched pathways were equivalent to those identified by RNA-seq. | [3] |

| Ligament Tissue Transcriptomics | Showed high internal reproducibility (r=0.97); cross-platform concordance with RNA-seq was moderate (r=0.64). | [23] |

| Asthma Biomarker Development | While the study developed an RNA-seq risk score, it noted the historical use and validation context of microarrays. | [25] |

Methodological Spotlight: Concentration-Response Modeling

The following workflow, derived from a toxicogenomics study, illustrates a key area where microarray standardization delivers robust results [3].

Diagram 1: Microarray concentration-response workflow.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

This protocol is adapted from a 2025 comparative study of cannabichromene and cannabinol [3].

Cell Culture & Exposure:

- Culture iPS-derived hepatocytes (e.g., iCell Hepatocytes 2.0) in a collagen-coated 24-well plate using a specialized plating and maintenance medium.

- On culture day 6, expose cells to varying concentrations of the test compound (e.g., cannabinoids diluted in DMSO). Include a vehicle control (0.5% DMSO). Incubate for 24 hours at 37°C and 5% CO₂.

RNA Sample Preparation:

- Lyse cells in a denaturing guanidinium-thiocyanate-containing buffer (e.g., RLT buffer) supplemented with β-mercaptoethanol.

- Homogenize lysates and purify total RNA using automated systems (e.g., EZ1 Advanced XL) with integrated DNase digestion to remove genomic DNA.

- Assess RNA concentration and purity (Nanodrop) and RNA integrity (RIN) using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer.

Microarray Processing (Affymetrix Platform):

- Starting with 100 ng of total RNA, generate double-stranded cDNA using a T7-linked oligo(dT) primer.

- Perform in vitro transcription (IVT) with biotinylated nucleotides to produce labeled complementary RNA (cRNA).

- Fragment the cRNA and hybridize to the microarray chip (e.g., GeneChip PrimeView Human Array) for 16 hours.

- Wash and stain the array on a fluidics station and scan it to generate image (DAT) files.

- Convert image files to cell intensity (CEL) files using the manufacturer's software (e.g., Affymetrix Command Console).

Data Analysis & BMC Modeling:

- Import CEL files into an analysis console (e.g., Affymetrix Transcriptome Analysis Console).

- Perform background adjustment, quantile normalization, and summarization using the RMA algorithm.

- Identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with a fold-change threshold and false-discovery rate (FDR) adjustment.

- Fit the expression data of significant DEGs to a concentration-response curve to calculate the Benchmark Concentration (BMC).

- The transcriptomic Point of Departure (tPoD) is defined as the lowest BMC among the significant DEGs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Microarray Experiments

| Reagent / Kit | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|

| TRIzol / RLT Buffer | Cell lysis and initial RNA stabilization [3] [23]. |

| DNase I Digestion Kit | Removal of contaminating genomic DNA during RNA purification [3]. |

| 3' IVT PLUS Reagent Kit | For cDNA synthesis, in vitro transcription, and biotin-labeling of target RNA [3]. |

| GeneChip Hybridization Kit | Contains buffers and controls for hybridizing labeled cRNA to the microarray [3]. |

| Fluidics Station & Scanner | Automated washing, staining, and imaging of the processed microarray chip [3] [22]. |

Microarray technology, with its proven standardization, cost-effectiveness, and analytical maturity, retains a vital role in the transcriptomics toolkit. For applications focused on targeted gene expression profiling, clinical prediction where models are established, and large-scale toxicogenomic screening, it provides a reliable and efficient solution. The choice between microarray and RNA-seq should be guided not by technological trend alone, but by a clear alignment between the platform's strengths and the specific biological questions and operational constraints of the research project.

While RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has emerged as the dominant platform for novel transcriptome profiling, offering a wider dynamic range and detection of novel features, microarrays remain a powerful, cost-effective tool for many applications. The choice between them is no longer a simple question of which is "better," but rather which is more fit-for-purpose based on specific research goals, budget, and analytical requirements. Recent evidence shows that for established applications like toxicogenomic pathway analysis and clinical endpoint prediction, both platforms can yield highly concordant biological conclusions [3] [12].

Platform Performance: A Quantitative Comparison

The table below summarizes a direct comparison of key performance metrics based on recent, head-to-head experimental studies.

Table 1: Experimental Comparison of Microarray and RNA-Seq Performance

| Performance Metric | Microarray | RNA-Seq | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Range | Limited by background and saturation [26] | Wider, precise for low and high abundance transcripts [26] | Toxicogenomic study in rat liver [26] |

| Protein-Coding DEGs Detected | Baseline | 1.5 to 5.6 times more DEGs identified [26] [13] | Study on human whole blood (223 vs. 2395 DEGs) [13] |

| Non-Coding RNA Detection | Limited to predefined probes | Comprehensive (lncRNA, miRNA, pseudogenes) [3] [26] | Cannabinoid toxicogenomics study [3] |

| Transcript/Splice Variant Resolution | No | Yes, enables detection of discordant transcript variants [12] | Neuroblastoma clinical endpoint prediction study [12] |

| Concordance in Pathway Analysis | High functional concordance despite differences in raw DEG lists [3] [26] | High functional concordance despite differences in raw DEG lists [3] [26] | Both platforms enriched similar liver toxicity pathways [26] |

| Performance in Clinical Prediction | Equivalent to RNA-seq for endpoint prediction [12] | Equivalent to microarray for endpoint prediction [12] | 360 models across 6 clinical endpoints in neuroblastoma [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Platform Comparison

To ensure valid and reproducible comparisons between platforms, a rigorous experimental methodology is required. The following protocol, derived from recent literature, outlines the key steps.

Core Principle

The most robust comparisons are performed by analyzing the same RNA samples on both platforms in parallel, minimizing biological variability and allowing direct assessment of technological differences [3] [26].

Detailed Workflow

Diagram 1: Experimental comparison workflow. RMA: Robust Multi-array Average; IVT: In Vitro Transcription; GSEA: Gene Set Enrichment Analysis; IPA: Ingenuity Pathway Analysis.

Key Methodological Considerations

- RNA Quality: Use high-quality total RNA (RNA Integrity Number, RIN ≥ 9) for both platforms [26].

- Library Preparation: For RNA-seq, use stranded, poly-A-enriched library kits (e.g., Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep) to enable direct comparison with microarray data focused on coding mRNA [3] [26].

- Data Transformation for Comparability: To directly integrate or compare data from both platforms, transform high-dimensional gene-level data into gene set enrichment scores (e.g., using single-sample GSEA). This filters out platform-specific noise and increases the biological concordance of the results [27].

Enhancing Cross-Platform Comparability

A significant challenge in the field is the direct integration of data from legacy microarray studies with modern RNA-seq datasets. Research has shown that transforming gene-level data into pathway-level scores significantly improves correlation.

Diagram 2: Cross-platform analysis via enrichment scores. ssGSEA: single-sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful transcriptomic profiling, regardless of platform, relies on a foundation of high-quality reagents and well-established protocols.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Transcriptomics

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Products / Kits |

|---|---|---|

| Total RNA Isolation Kit | Purifies intact RNA from cells or tissue; critical first step for both platforms. | QIAGEN RNeasy Plus kits, PAXgene Blood RNA Kit [3] [13] |

| Globin mRNA Depletion Reagents | Reduces high abundance of globin transcripts in whole blood RNA, improving detection of other mRNAs. | GLOBINclear Kit [13] |

| Microarray Target Prep Kit | Converts RNA into fluorescently labeled cDNA for hybridization. | GeneChip 3' IVT Plus Reagent Kit [3] [13] |

| RNA-seq Library Prep Kit | Converts RNA into a sequencing-ready library of cDNA fragments with adapters. | Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep, TruSeq Stranded mRNA Kit, NEBNext Ultra II [3] [26] [13] |

| Reference Genome & Annotation | Essential for RNA-seq read alignment and quantification. | ENSEMBL, UCSC Genome Browser, GENCODE [28] [29] |

| Enrichment Analysis Software | For functional interpretation of gene lists and cross-platform data transformation. | Qiagen IPA, GSEA [26] [27] [13] |

Statistical Analysis and Sample Size Considerations

The statistical pipeline for RNA-seq data is well-established, with tools like DESeq2 and limma-voom being standards for differential expression analysis [29] [30]. A critical consideration for robust RNA-seq studies is sample size.

- Underpowered studies (N < 5) yield highly misleading results with high false positive rates and poor sensitivity [14].

- Minimum sample size should be 6-7 biological replicates per group to achieve a false positive rate below 50% and sensitivity above 50% for a 2-fold change cutoff [14].

- Adequate sample size of 8-12 replicates per group significantly improves the recapitulation of true biological effects and is strongly recommended [14].

The evolving landscape of transcriptomics is not a simple story of one technology replacing another. RNA-seq is the undisputed leader for discovery-phase research, offering an unparalleled view of the transcriptome's complexity. However, microarrays maintain their relevance due to lower cost, smaller data sizes, and extensive curated public databases. The trend in platform adoption is increasingly guided by the research question: use RNA-seq for discovery and microarrays for focused, high-throughput applications. Furthermore, methods like gene set enrichment scoring are breaking down barriers between platforms, allowing the vast legacy of microarray data to be leveraged alongside modern RNA-seq datasets, ensuring that valuable biological information remains relevant in the sequencing era.

From Sample to Insight: Practical Workflows and Research Applications

The evolution of transcriptomic technologies has fundamentally transformed biological research and drug discovery. For over a decade, whole-genome microarrays served as the primary platform for transcriptome-wide gene expression profiling, utilizing a hybridization-based approach to measure fluorescence intensity of predefined transcripts [3]. While microarrays offer advantages in relatively simple sample preparation, lower per-sample costs, and well-established data processing methodologies, they suffer from limitations including a restricted dynamic range, high background noise, and an inability to detect novel transcripts such as splice variants and non-coding RNAs [3]. The mid-2000s witnessed the emergence of next-generation RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) as a powerful alternative based on counting reads that can be reliably aligned to a reference sequence. This fundamental shift provides virtually unlimited dynamic range and enables discovery of previously undetectable transcripts [3] [31].

Despite its gradual adoption as the mainstream transcriptomic platform, RNA-seq analysis presents substantial challenges for researchers. The process involves multiple intricate steps, each requiring specific tools and parameters, with the added complexity of species-specific considerations that impact tool performance [32]. For researchers lacking extensive bioinformatics backgrounds, constructing an optimal analysis workflow from the array of available tools represents a significant hurdle [32]. This deconstruction of the RNA-seq workflow aims to provide clarity and guidance for navigating these critical decisions, with particular emphasis on how these choices impact the reliability and interpretability of results in both basic research and drug development contexts.

Workflow Breakdown: Tools, Comparisons, and Methodologies

A typical RNA-seq analysis pipeline progresses through three primary phases: primary analysis (processing raw sequencing data), secondary analysis (aligning and quantifying pre-processed reads), and tertiary analysis (extracting biologically relevant information) [33]. The following sections deconstruct the critical steps of this workflow, comparing popular tools and providing experimental protocols.

Primary Analysis: From Raw Sequences to Processed Reads

The initial processing of raw sequencing data includes quality control, demultiplexing, adapter trimming, and quality filtering. This primary analysis phase is crucial, as the quality of output directly impacts all subsequent results.

Base calling and demultiplexing begin the pipeline. Sequencing instruments generate raw data in binary base call (BCL) format, which is converted to FASTQ files—the standard format for storing unaligned NGS reads containing both sequence and quality score information [33]. For multiplexed samples sequenced together, demultiplexing sorts reads into individual files based on their unique index (barcode) sequences. Tools for this step include Illumina's proprietary bcl2fastq and Lexogen's iDemux, with dual index sequencing providing the best opportunity for error correction and data salvage [33].

Read trimming follows demultiplexing, removing undesirable adapter contamination, poly(A) tails, poly(G) sequences (common in Illumina sequencers with 2-channel chemistry), and poor-quality sequences. Failure to remove these artifacts reduces alignment rates and increases false alignments [33]. Popular trimming tools include Cutadapt and Trimmomatic [33], with fastp and Trim_Galore also being widely used options [32].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Analysis Tools

| Tool | Primary Function | Key Features | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| fastp [32] | Filtering & Trimming | Rapid analysis; simple operation; integrated quality control | Significantly enhances processed data quality [32] |

| Trim_Galore [32] | Filtering & Trimming | Integrates Cutadapt & FastQC; comprehensive QC in single step | May cause unbalanced base distribution in tail [32] |

| Cutadapt [33] | Read Trimming | Effective adapter removal | Often used through Trim_Galore wrapper |

| Trimmomatic [33] | Read Trimming | Highly customizable parameters | Complex parameter setup; no speed advantage [32] |

| iDemux [33] | Demultiplexing | Handles i7, i5, and i1 indices; sophisticated error correction | Maximizes data output by rescuing reads with index errors |

Quality control assessment uses tools like FastQC for initial quality checks on raw sequence data, with MultiQC providing consolidated reports across multiple samples [34]. Key metrics include the Q30 score (percentage of bases with quality score ≥30, indicating 99.9% base-calling accuracy), cluster density, and percentage of reads passing filter [33]. The decision to trim reads is based on these QC results, considering factors like poor-quality bases, adapter contamination, and unbalanced base composition [34].

Secondary Analysis: Alignment and Quantification

Secondary analysis involves aligning processed reads to a reference genome and summarizing them into quantitative expression values.

Read alignment requires specialized, splice-aware algorithms because RNA-seq reads originate from spliced mRNA transcripts. Generic DNA aligners like BWA or Bowtie2 are unsuitable as they cannot handle reads spanning exon-intron junctions [34]. The alignment process matches reads to specific genomic regions, with the percentage of successfully and uniquely aligned reads serving as a key quality metric [31].

Table 2: Comparison of Splice-Aware Alignment Tools

| Tool | Algorithm Type | Key Features | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| STAR [31] [5] | Spliced Transcripts Alignment to Reference | Fast, accurate splice junction discovery; handles large volumes of data | High memory requirements |

| HISAT2 [34] | Hierarchical Indexing | Successor to TopHat2; fast with low memory requirements | Standard choice for many RNA-seq pipelines |

| TopHat2 [31] | Spliced Read Mapper | Previously popular; uses Bowtie for alignment | Largely superseded by newer tools |

Alignment experimental protocol typically begins with building a genome index, followed by mapping read pairs to the indexed genome. For example, with HISAT2, the commands would be [34]:

The alignment output is typically in Sequence Alignment/Map (SAM) or its binary equivalent (BAM) format [31].

Read summarization counts the mapped reads corresponding to known genes, exons, or transcripts, producing a count matrix that serves as input for differential expression analysis [31]. This step requires an annotation file (GTF or GFF) linking reads to genomic features. The four most common annotation databases are RefSeq, UCSC, Ensembl, and GENCODE [31].

Table 3: Comparison of Read Quantification Tools

| Tool | Counting Approach | Key Features | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| featureCounts [31] | Gene-level or exon-level | Fast; low memory requirements; part of Subread package | Count matrix (genes × samples) |

| HTSeq-count [31] | Gene-level | Flexible counting modes; well-established | Count matrix (genes × samples) |

The quantification command with featureCounts might appear as:

Tertiary Analysis: Differential Expression and Functional Interpretation

The final phase focuses on extracting biological meaning from quantitative expression data, with differential expression (DE) analysis as its cornerstone.

Differential expression analysis identifies genes whose expression patterns significantly differ across experimental conditions or phenotypes. Unlike microarray data analysis, which often uses t-tests or similar parametric tests, RNA-seq count data requires specialized statistical methods that account for its discrete nature and inherent technical variability [31]. Common normalization approaches include Reads Per Kilobase Million (RPKM), Fragments Per Kilobase Million (FPKM), Counts Per Million (CPM), and Transcripts Per Kilobase Million (TPM), which adjust for gene length and sequencing depth variations [31].

Experimental protocol for DE analysis typically utilizes tools like DESeq2, which employs a negative binomial distribution to model count data and estimate dispersion. A basic DESeq2 analysis in R would follow this structure [34]:

Functional enrichment analysis follows DE analysis, interpreting the biological significance of differentially expressed genes through Gene Ontology (GO) term analysis, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway mapping, or other gene set enrichment methods [31] [33]. This step translates gene lists into actionable biological insights about affected pathways, functions, and processes.

Critical Considerations in Experimental Design

The Critical Role of Sample Size

Appropriate sample size determination is arguably the most crucial consideration in RNA-seq experimental design. Underpowered studies with too few replicates yield unreliable results characterized by excessive false positives, false negatives, and inflated effect sizes—a major factor driving irreproducibility in scientific literature [14].

A comprehensive 2025 study examining murine RNA-seq experiments provided empirical evidence for sample size requirements. Using large cohorts (N=30) of wild-type and genetically modified mice as gold standards, researchers systematically evaluated how results from smaller sample sizes recapitulated full datasets [14]. The findings demonstrated that experiments with N=4 or fewer replicates were "highly misleading," with false discovery rates (FDR) exceeding 38% for N=3 in some tissues [14].

Table 4: Sample Size Recommendations from Empirical Data [14]

| Sample Size (N) | False Discovery Rate | Sensitivity | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| N ≤ 4 | Very High (>38%) | Very Low | Highly misleading; insufficient for reliable results |

| N = 5 | High | Low | Fails to recapitulate full signature |

| N = 6-7 | <50% | >50% | Minimum for 2-fold expression differences |

| N = 8-12 | Significantly Lower | Significantly Higher | Significantly better; recommended range |

| N > 12 | Approaches 0% | Approaches 100% | Diminishing returns; ideal but resource-intensive |

The study further demonstrated that simply raising the fold-change threshold cannot compensate for inadequate sample sizes, as this strategy results in consistently inflated effect sizes and substantially reduced detection sensitivity [14]. Researchers should aim for a minimum of 6-7 biological replicates per condition, with 8-12 replicates providing significantly more reliable results [14].

Bulk RNA-seq vs. Microarray: An Updated Comparison

While RNA-seq has largely superseded microarrays in many applications, recent evidence suggests microarrays remain viable for specific use cases. A 2024 comparative study of cannabinoid effects using both platforms revealed that despite RNA-seq identifying larger numbers of differentially expressed genes with wider dynamic ranges, both platforms displayed equivalent performance in identifying impacted functions and pathways through gene set enrichment analysis [3].

Furthermore, transcriptomic point of departure (tPoD) values derived through benchmark concentration (BMC) modeling were nearly identical between platforms [3]. Considering the relatively low cost, smaller data size, and better availability of software and public databases for analysis, microarray technology may still be appropriate for traditional transcriptomic applications like mechanistic pathway identification and concentration-response modeling [3].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

RNA-seq has become indispensable throughout the drug discovery and development pipeline, contributing significantly to multiple stages from target identification to clinical application.

In target discovery and selection, RNA-seq helps uncover genes and pathways playing important roles in disease mechanisms [35]. Once candidate drugs are identified, RNA-seq detects drug-induced genome-wide changes in gene expression, helping to elucidate mechanisms of action [35]. The technology also contributes to biomarker discovery, where transcriptomic profiles correlate with disease presence, progression, or severity, enabling early diagnosis and providing potential therapeutic targets [35].

Additional applications include identifying genes involved in drug resistance and sensitivity, assessing drug toxicity by monitoring changes in gene expression caused by drug exposure, and drug repurposing by screening for new therapeutic targets [35]. The emergence of time-resolved RNA-seq addresses a critical limitation of conventional approaches by enabling observations of RNA abundances over time, distinguishing between primary (direct) and secondary (indirect) drug effects [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Essential Reagents and Materials for RNA-seq Experiments

| Item | Function/Purpose | Examples/Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation Kits | Extract high-quality RNA from biological samples | Quality critical; assess with RIN (RNA Integrity Number) |

| Poly-A Selection Kits | Enrich for mRNA by binding poly-A tails | Standard for mRNA sequencing; excludes non-polyadenylated RNAs |

| Ribo-Depletion Kits | Remove ribosomal RNA | Alternative to poly-A selection; preserves non-coding RNAs |

| Stranded Library Prep Kits | Create sequencing libraries preserving strand information | Essential for determining transcript orientation |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Tag individual RNA molecules pre-amplification | Correct for PCR amplification bias; enable digital counting |

| Quality Control Instruments | Assess RNA and library quality | Bioanalyzer/Tapestation (RIN), Qubit (quantification) |

| Reference Genome | Map sequenced reads to genomic coordinates | Species-specific (e.g., GRCh38 for human, GRCm39 for mouse) |

| Annotation File (GTF/GFF) | Define genomic features for read summarization | Sources: Ensembl, GENCODE, RefSeq |

Visualizing the RNA-seq Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete RNA-seq analysis workflow, from raw data to biological interpretation, highlighting key decision points at each stage.

RNA-seq Analysis Workflow: This diagram outlines the primary steps in RNA-seq data analysis, from raw data processing to biological interpretation, highlighting essential tools and decision points.

The deconstruction of the RNA-seq workflow reveals a sophisticated analytical pipeline with critical decision points at each stage. Tool selection—from trimming and alignment algorithms to quantification and statistical analysis methods—significantly impacts results and their biological interpretation. The empirical evidence demonstrating the necessity of adequate sample sizes (N=8-12 replicates per condition) provides crucial guidance for experimental design, addressing the reproducibility crisis in transcriptomic literature [14]. While RNA-seq offers distinct advantages over microarrays in detection range and novel transcript discovery, microarray technology remains viable for specific applications like pathway analysis and concentration-response modeling [3].

For researchers in drug discovery and development, RNA-seq provides powerful capabilities throughout the pipeline, from target identification to mechanism elucidation and biomarker discovery. The implementation of robust, well-designed RNA-seq workflows, informed by the comparative data and methodologies presented here, will continue to drive advances in both basic biological understanding and therapeutic development.

Gene expression analysis is a cornerstone of modern molecular biology, enabling researchers to understand cellular processes, disease mechanisms, and drug responses. Among the technologies developed for this purpose, DNA microarrays represent a well-established and robust platform. This guide provides a detailed examination of the microarray workflow, focusing on its core steps of labeling, hybridization, and signal detection, while objectively comparing its performance with the increasingly popular RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) technology. Understanding the technical specifics and performance characteristics of microarrays is essential for researchers and drug development professionals to select the appropriate gene expression analysis tool for their specific applications.

Microarray Workflow: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

The microarray process involves a series of coordinated steps to convert RNA samples into quantifiable gene expression data.

Sample Labeling

The process begins with the extraction of total RNA from biological samples. In the most common fluorescent labeling approaches, RNA is reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) while incorporating labeled nucleotides or using labeled primers [3] [36].

Key Labeling Methods:

- Direct Incorporation: Fluorophore-conjugated nucleotides (e.g., Cy3 or Cy5) are directly incorporated during the reverse transcription reaction. This method is straightforward but can suffer from lower cDNA yields due to steric hindrance from the fluorescent moieties [36].

- Indirect (Aminoallyl) Method: Modified aminoallyl nucleotides are incorporated during cDNA synthesis and are later chemically coupled with the fluorescent dye. This two-step process provides higher dye incorporation and reduces dye bias, making it a benchmark for dual-labeling experiments [36].

- Direct Random-Primed Labeling: This one-step method uses 5'-labeled random nonamer primers during reverse transcription, followed by RNA template hydrolysis and cleanup. It offers a rapid, cost-effective alternative with excellent reproducibility, increasing the statistical confidence in identifying differentially expressed genes [36].

After labeling, the cDNA yield, dye incorporation (pmol of dye per μg of cDNA), and fragment size distribution are assessed to ensure quality before hybridization [36].

Hybridization

The fluorescently labeled cDNA is applied to the microarray slide, which contains thousands of predefined DNA probes immobilized in a grid-like pattern on a solid surface [37] [38]. These probes are short, synthetic sequences complementary to specific genes of interest.

Hybridization occurs under controlled conditions (temperature, salt concentration, and time) that promote specific binding between the labeled cDNA targets and their complementary probes on the array [37]. Stringent washing steps follow to remove any non-specifically bound cDNA, thereby reducing background noise and improving data accuracy [39] [40].

Signal Detection and Data Processing

After hybridization and washing, the microarray is scanned using a specialized fluorescence scanner [37]. This scanner measures the fluorescence intensity at each spot on the array, with the signal intensity corresponding to the abundance of that particular transcript in the original sample [38].

The resulting image file is then processed through several steps:

- Background Correction: Local background distortions are minimized by calculating the average background signal from a wider area around each spot, preserving the overall variability across the slide [39].

- Normalization: Scale factors are applied to correct for technical variations, such as differences in dye properties and hybridization efficiency across the slide. Methods like the "constant majority" assume most probes do not change in concentration and use local regression (e.g., LOWESS) to adjust for intensity- and spatial-dependent biases [39].

- Differential Expression Scoring: Statistical methods are applied to identify array elements that are significantly differentially hybridized between experimental conditions [39].

Performance Comparison: Microarray vs. RNA-Seq

While both microarrays and RNA-seq are powerful tools for gene expression profiling, they exhibit distinct technical and performance characteristics.

Technical and Analytical Comparison

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Microarray and RNA-Seq

| Aspect | Microarray | RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Technology Principle | Hybridization-based; fluorescence detection of predefined probes [38] | Sequencing-based; digital counting of sequenced reads [41] [38] |

| Coverage | Known transcripts only [38] | All transcripts, including novel genes, splice variants, and non-coding RNAs [38] |

| Dynamic Range | Narrower [3] [38] | Wide [3] [38] |

| Sensitivity | Moderate; lower for low-abundance transcripts [38] | High; capable of detecting rare transcripts [38] |

| Data Complexity | Lower; well-established, standardized analysis pipelines [3] [38] | Higher; requires more complex bioinformatics pipelines [38] |

| Cost per Sample | Lower [3] [38] | Higher [38] |

Experimental Data and Concordance

Recent studies have systematically compared the outputs of both platforms. A 2025 study on cannabinoids found that despite RNA-seq identifying larger numbers of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with a wider dynamic range, both platforms revealed similar overall gene expression patterns and equivalent performance in identifying impacted functions and pathways through gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) [3]. Furthermore, transcriptomic point of departure (tPoD) values derived from benchmark concentration (BMC) modeling were on the same level for both platforms [3].

Another study from 2025, analyzing samples from youth with and without HIV, found a high median Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.76 for gene expression profiles between the two platforms [41]. However, RNA-seq identified 2,395 DEGs compared to 427 by microarray, with 223 DEGs shared between them, representing 52.2% of microarray DEGs and 9.3% of RNA-seq DEGs [41]. This indicates significant concordance in the overlapping DEGs, but also highlights the broader detection capability of RNA-seq.

Table 2: Comparative Performance in Differential Gene Expression Analysis

| Performance Metric | Microarray | RNA-Seq | Study Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) | 427 | 2,395 | HIV study [41] |

| Shared DEGs | 223 (52.2% of its total) | 223 (9.3% of its total) | HIV study [41] |

| Correlation of Expression Profiles | Median Pearson r = 0.76 with RNA-seq | Median Pearson r = 0.76 with microarray | HIV study [41] |

| Pathway Analysis | 47 perturbed pathways identified | 205 perturbed pathways identified | HIV study [41] |

| Transcriptomic Point of Departure (tPoD) | Equivalent levels for both platforms | Equivalent levels for both platforms | Cannabinoid toxicogenomics study [3] |

Essential Reagents and Tools for Microarray Experiment

A successful microarray experiment relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microarray Workflow

| Item | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Total RNA Extraction Kit | Isolates high-quality, intact RNA from biological samples. | PAXgene Blood RNA Kit [41], RNeasy Plus Mini Kit [15] |

| Globin Reduction Kit | Depletes abundant globin mRNA from blood samples to improve detection of other transcripts. | GLOBINclear Kit [41] |

| Labeling Kit | Converts RNA into fluorescently labeled cDNA for hybridization. | GeneChip 3' IVT Plus Reagent Kit [3], Direct Random-Primed Labeling reagents [36] |

| Microarray Chip | Solid support with immobilized DNA probes for specific transcript detection. | GeneChip PrimeView Human Gene Expression Array [3] |

| Hybridization System | Provides controlled conditions for specific probe-target binding. | GeneChip Hybridization Oven [3] |

| Fluidics Station | Automates the washing and staining steps post-hybridization. | GeneChip Fluidics Station [3] |

| Scanner | Detects fluorescence signals from hybridized arrays. | GeneChip Scanner [3] |

| Analysis Software | Processes raw image data, performs normalization, and identifies DEGs. | Affymetrix Transcriptome Analysis Console (TAC) [3], ExpressYourself [39] |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram summarizes the core steps of the microarray workflow and how it compares to the RNA-seq process.

Microarray technology remains a viable and effective platform for gene expression analysis, particularly in contexts where the study focuses on well-annotated genomes, cost-effectiveness is a priority, and standardized, accessible data processing is desired [3] [38]. Its workflow—encompassing sample labeling, hybridization to predefined probes, and fluorescence-based signal detection—is well-established and robust. While RNA-seq offers a broader dynamic range, superior sensitivity, and the ability to discover novel transcripts, both platforms can produce highly concordant results in functional pathway analysis and concentration-response modeling [3] [41]. The choice between microarray and RNA-seq should therefore be guided by the specific research questions, genomic resources, and analytical capabilities at hand.

For decades, transcriptomics has been a cornerstone of molecular biology, with bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and microarray standing as the two primary technologies for gene expression analysis. While RNA-seq is often viewed as a successor, microarray technology remains a viable and robust platform for many applications. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance, supported by experimental data, to help researchers align platform selection with their specific research objectives.

Bulk RNA-seq and microarray technologies operate on fundamentally different principles. Microarrays use a hybridization-based approach, where fluorescently-labeled nucleic acids bind to predefined probes on a chip, providing a relative measure of gene expression [3] [42]. In contrast, RNA-seq is a sequencing-based method that involves converting RNA into a cDNA library, followed by high-throughput sequencing and alignment of the resulting reads to a reference genome to enable digital counting of transcripts [3] [42].

The core strengths of each platform derive from their underlying methodologies:

Microarray

- Cost-Effectiveness: Lower per-sample cost, making it suitable for large-scale studies [3] [43].

- Established Analysis: Well-standardized, user-friendly software and public databases for data interpretation [3].

- Focused Data: Smaller, more manageable data sizes with a focus on known, annotated transcripts [3].

Bulk RNA-Seq

- Dynamic Range and Discovery: Unrestricted dynamic range and ability to detect novel transcripts, including splice variants, non-coding RNAs, and gene fusions [3] [42].

- Precision and Sensitivity: Higher precision and lower background noise compared to microarray [3].

- Multi-Faceted Data: Can reveal a wider range of genomic alterations, including mutations, indels, and alternative splicing, from a single assay [42].

Direct Experimental Comparison: A 2025 Case Study

A direct comparative study published in 2025 provides robust, quantitative data on the performance of both platforms in a toxicogenomic context. The research used two cannabinoids, cannabichromene (CBC) and cannabinol (CBN), as case studies in human iPSC-derived hepatocytes to assess their capabilities in concentration-response modeling and pathway analysis [3].

Experimental Protocol

- Cell Culture & Exposure: Commercial iPSC-derived hepatocytes (iCell Hepatocytes 2.0) were cultured and exposed to varying concentrations of CBC and CBN for 24 hours [3].

- RNA Sample Preparation: Total RNA was purified using an EZ1 Advanced XL automated instrument. RNA concentration, purity, and integrity (RIN) were rigorously checked [3].

- Microarray Data Generation: From 100 ng of total RNA, biotin-labeled cRNA was synthesized and hybridized onto GeneChip PrimeView Human Gene Expression Arrays. Arrays were scanned, and CEL files were processed using the Affymetrix Transcriptome Analysis Console (TAC) software (v4.0) with the RMA algorithm for normalization [3].

- RNA-seq Data Generation: Sequencing libraries were prepared from 100 ng of total RNA using the Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep, Ligation Kit. PolyA-tailed mRNAs were purified for library construction [3].

- Data Analysis: Both datasets were analyzed for differentially expressed genes (DEGs), followed by gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA). Benchmark concentration (BMC) modeling was performed to derive transcriptomic points of departure (tPoD) [3].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison from Cannabinoid Case Studies [3]

| Performance Metric | Microarray Findings | Bulk RNA-Seq Findings | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) | Identified a robust but smaller set of DEGs. | Detected larger numbers of DEGs with a wider dynamic range. | RNA-seq has higher sensitivity and a broader detection range. |

| Functional Pathway Analysis (GSEA) | Effectively identified functions and pathways impacted by exposure. | Revealed equivalent performance in identifying impacted functions and pathways. | Key biological conclusions were consistent across platforms. |

| Transcriptomic Point of Departure (tPoD) | tPoD values for CBC and CBN were on specific levels. | Produced tPoD values that were on the same levels for both compounds. | Both platforms are equally effective for quantitative risk assessment. |

| Additional Capabilities | Limited to predefined, known transcripts. | Identified various non-coding RNA transcripts (e.g., miRNA, lncRNA). | RNA-seq is superior for discovery-based research. |

This experimental data demonstrates that while RNA-seq possesses superior technical capabilities, the two platforms can yield equivalent conclusions for traditional applications like pathway identification and concentration-response modeling [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials used in the featured comparative experiment, which can serve as a reference for designing similar studies [3].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Example Product/Brand |

|---|---|---|

| iPSC-derived Hepatocytes | Biologically relevant in vitro model for toxicology and drug metabolism studies. | iCell Hepatocytes 2.0 (FUJIFILM Cellular Dynamics) |

| RNA Purification Kit | Automated purification of high-quality total RNA, including DNase digestion step. | EZ1 RNA Cell Mini Kit (Qiagen) on EZ1 Advanced XL instrument |

| RNA Quality Control | Assessment of RNA Integrity Number (RIN) to ensure sample quality. | RNA 6000 Nano Reagent Kit on Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer |

| Microarray Platform | Array for whole-genome expression profiling of known human transcripts. | GeneChip PrimeView Human Gene Expression Array (Affymetrix) |

| Microarray Labeling & Processing | Kit for sample preparation, including IVT-based cDNA and cRNA synthesis. | GeneChip 3' IVT PLUS Reagent Kit (Affymetrix) |

| RNA-seq Library Prep Kit | Kit for construction of stranded, sequencing-ready RNA-seq libraries from polyA-selected mRNA. | Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep, Ligation Kit |

| Microarray Analysis Software | Software suite for processing, normalizing, and analyzing microarray CEL files. | Affymetrix Transcriptome Analysis Console (TAC) (v4.0) |

Workflow and Data Analysis Diagrams

The following diagrams illustrate the core experimental workflows and the logical process of data analysis and interpretation for the two platforms.

Microarray and RNA-seq Experimental Workflows

Transcriptomic Data Analysis and Application Logic

Decision Framework: Selecting the Right Tool

The choice between bulk RNA-seq and microarray is not a matter of which is universally better, but which is the right fit for the research question, budget, and analytical constraints.

Table 3: Platform Selection Guide Based on Research Goals