RNA-seq vs qPCR: A Modern Guide to Differential Expression Validation

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the complementary roles of RNA-seq and qPCR in differential expression analysis.

RNA-seq vs qPCR: A Modern Guide to Differential Expression Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the complementary roles of RNA-seq and qPCR in differential expression analysis. It covers the foundational principles of each technology, explores their optimal applications from discovery to validation, and delivers practical troubleshooting strategies. By synthesizing evidence from large-scale benchmarking studies, it offers clear guidance on experimental design, data analysis pipelines, and the critical question of when orthogonal validation is necessary to ensure robust, reproducible results in biomedical research.

Understanding the Core Technologies: From qPCR Gold Standard to RNA-seq Discovery

In the field of gene expression analysis, the debate between adopting comprehensive RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) technologies and established targeted methods remains active. While next-generation sequencing provides an unbiased, genome-wide view of the transcriptome, its accuracy for quantifying specific genes of interest requires rigorous validation. Within this context, quantitative PCR (qPCR) maintains its position as the established gold standard for targeted gene quantification, offering unparalleled accuracy, sensitivity, and reproducibility for validating gene expression data. This guide objectively compares the performance of qPCR against RNA-seq, presenting experimental data that underscores their respective strengths in research and drug development.

Methodological Foundations: How qPCR and RNA-seq Work

The fundamental differences in how qPCR and RNA-seq quantify gene expression underlie their performance characteristics. The workflows below illustrate the distinct steps involved in each process.

qPCR Workflow

RNA-seq Workflow

qPCR operates on the principle of amplifying a specific DNA target using sequence-specific primers, with fluorescence accumulation monitored in real-time. The cycle at which fluorescence crosses a threshold (Cq) is inversely proportional to the starting quantity of the target [1]. This direct relationship between signal and target concentration provides a highly precise quantification method.

RNA-seq utilizes high-throughput sequencing to capture fragments from the entire transcriptome. The resulting reads are mapped to a reference genome or transcriptome, and expression levels are inferred based on read counts [2]. This approach provides a comprehensive view but introduces mapping ambiguities and computational complexities that can affect quantification accuracy, especially for polymorphic gene families like HLA [3].

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Experimental Data

Direct comparisons between qPCR and RNA-seq reveal important differences in their quantification performance. The following table summarizes key findings from controlled studies that benchmarked these technologies head-to-head.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of qPCR vs. RNA-seq Performance

| Performance Metric | qPCR Performance | RNA-seq Performance | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Correlation | Reference Standard | Moderate correlation (rho: 0.20-0.53) for HLA genes [3] | HLA class I gene expression in PBMCs from 96 healthy donors [3] |

| Fold Change Concordance | Reference Standard | 80-85% of genes show consistent fold changes with qPCR [2] | MAQCA/MAQCB reference samples; 18,080 protein-coding genes [2] |

| Non-concordant Genes | Reference Standard | 15-20% of genes show discordant differential expression [4] | Analysis of five RNA-seq workflows vs. qPCR [2] [4] |

| Technology-specific Biases | Minimal | Specific gene sets with inconsistent expression; typically shorter, lower expressed genes with fewer exons [2] | Systematic benchmarking using whole-transcriptome qPCR data [2] |

| Dynamic Range | High (6-8 orders of magnitude with proper validation) [5] | Broader in theory but limited for low-abundance transcripts | Dilution series with known standards [5] |

The moderate correlation between qPCR and RNA-seq for highly polymorphic HLA genes highlights the particular challenges RNA-seq faces with complex gene families [3]. While approximately 85% of genes show consistent fold-change relationships between the technologies, the remaining 15% discordance rate necessitates careful validation for key targets [2] [4].

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

qPCR Assay Validation Protocol

For reliable qPCR results, the following validation steps must be implemented according to MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines [5] [6]:

- Inclusivity and Exclusivity Testing: Verify that primers detect all intended target variants (inclusivity) and do not amplify non-targets (exclusivity) through both in silico analysis and experimental testing [5].

- Dynamic Range and Efficiency: Prepare a seven-point 10-fold dilution series of the target template in triplicate. The assay should demonstrate a linear dynamic range of 6-8 orders of magnitude with amplification efficiencies between 90-110% [5].

- Limit of Detection (LOD) and Quantification (LOQ): Determine the lowest concentration that can be detected (LOD) and reliably quantified (LOQ) with acceptable precision [5].

- Precision and Accuracy: Assess intra- and inter-assay variability, with accuracy measured as closeness to the true value and precision as agreement between replicates [6].

RNA-seq Validation Using qPCR

When using qPCR to validate RNA-seq findings:

- Reference Gene Selection: Identify stable, highly expressed reference genes specifically for your experimental system. RNA-seq data itself can be mined to identify optimal reference genes, moving beyond traditional housekeeping genes that may vary under different conditions [7] [8].

- Candidate Gene Prioritization: Focus validation efforts on genes with fold changes >2 and adequate expression levels (e.g., log2 TPM >5) to ensure reliable detection by qPCR [8].

- Sample Overlap: Ideally, use the same RNA samples for both RNA-seq and qPCR validation to remove biological variation from the comparison [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for qPCR Experiments

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence-Specific Primers | Amplify target sequence | Must be validated for inclusivity/exclusivity; designed to avoid secondary structures [5] |

| Fluorescent Detection System | (e.g., SYBR Green, hydrolysis probes) | Enable real-time monitoring of amplification; probes offer higher specificity [1] |

| Reverse Transcriptase Enzyme | Convert RNA to cDNA | Efficiency impacts overall quantification accuracy; must be consistent across samples [6] |

| Quantification Standards | (e.g., synthetic oligos, purified amplicons) | Create standard curve for absolute quantification; should mimic sample amplification [1] |

| RNA Isolation Reagents | Purify intact RNA from samples | Quality critical; must remove genomic DNA contamination [6] |

| Reference Genes | Normalize technical and biological variation | Must be stably expressed across experimental conditions; not necessarily traditional housekeepers [7] [8] |

Decision Framework: When to Use Each Technology

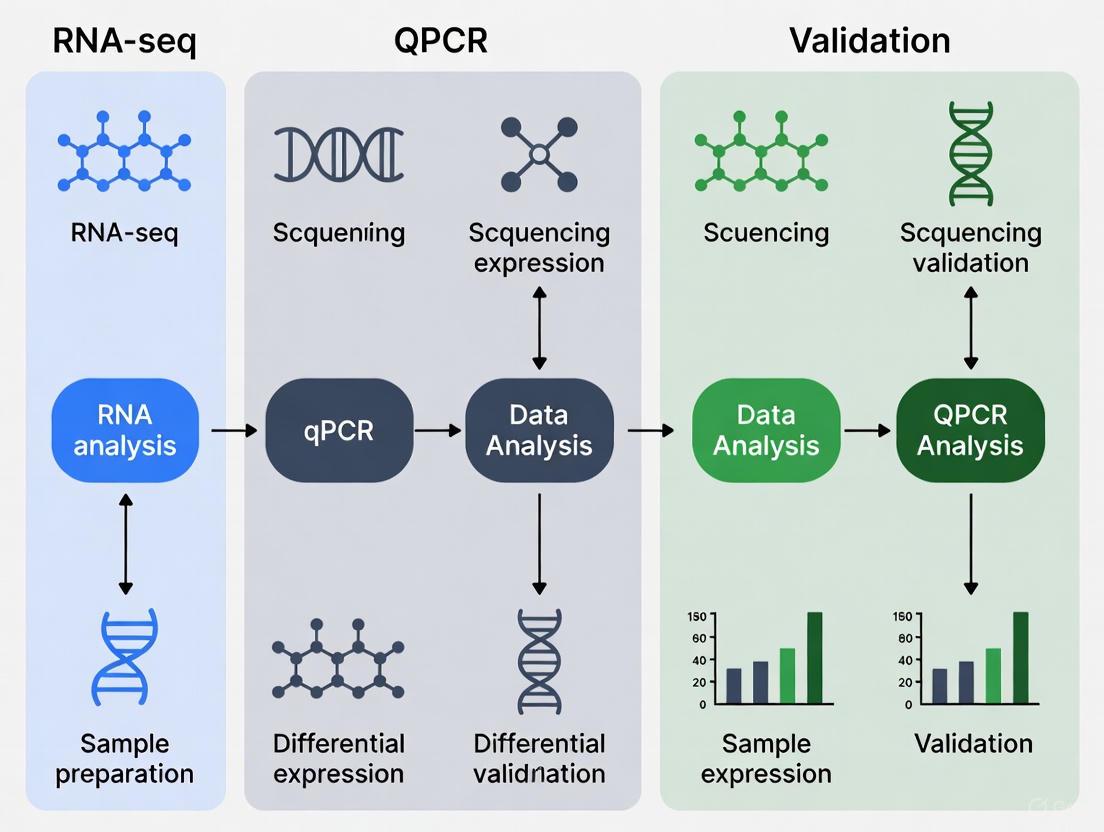

The relationship between qPCR and RNA-seq is often complementary rather than competitive. The following diagram illustrates their interplay in a rigorous gene expression study.

Appropriate Applications for qPCR:

- Targeted validation of genes identified in discovery-phase RNA-seq studies

- High-throughput clinical screening of established biomarker panels

- Regulated environments requiring validated assays (e.g., diagnostic test development)

- Studies with limited sample material where maximum sensitivity is required

- Rapid turnaround projects with constrained computational resources

Appropriate Applications for RNA-seq:

- Discovery-phase research to identify novel transcripts and splice variants

- Comprehensive transcriptome profiling without prior knowledge of targets

- Studies of structural variants, fusion genes, or allele-specific expression

- Organisms without established genomes (using de novo assembly approaches)

In the evolving landscape of gene expression analysis, qPCR maintains its critical role as the gold standard for targeted quantification. Its superior accuracy, sensitivity, and reproducibility make it indispensable for validating RNA-seq findings, particularly for clinically significant targets. While RNA-seq provides an unparalleled discovery platform, the 15-20% discordance rate between the technologies necessitates orthogonal validation for key results. Researchers should view these technologies as complementary components of a rigorous gene expression workflow, leveraging the strengths of each to generate reliable, reproducible data that advances scientific understanding and drug development.

For decades, gene expression analysis was constrained by targeted approaches, with quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) serving as the gold standard for measuring the expression of a limited number of pre-selected genes. While qRT-PCR offers excellent sensitivity and reproducibility for focused studies, its reliance on a priori knowledge of target genes inherently biases discovery and prevents a holistic understanding of cellular states [9]. The advent of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has fundamentally transformed this paradigm by providing an unbiased, genome-wide platform for transcriptome exploration. This technology enables researchers to quantify gene expression across the entire transcriptome, detect novel transcripts, identify alternative splicing events, and discover fusion genes—all without any prior assumptions about the genome [10].

This guide objectively compares the performance of RNA-seq against established technologies like qRT-PCR and microarrays, providing supporting experimental data and detailed methodologies to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals navigate this powerful landscape.

Technology Comparison: RNA-seq vs. qPCR and Microarrays

Key Characteristics at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core differences between RNA-seq and its primary alternatives.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Gene Expression Analysis Technologies

| Feature | RNA-seq | qPCR | Microarrays |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput | High (entire transcriptome) | Medium (tens to hundreds of targets) | High (known transcriptome) |

| Prior Knowledge Required | No (can discover novel features) | Yes (specific primers/probes needed) | Yes (probes designed from known sequences) |

| Dynamic Range | >9,000-fold [10] | ~7-log range [9] | ~3,000-fold |

| Sensitivity | High (can detect low-abundance transcripts) | Very High (can detect single copies) | Lower (background noise limitations) |

| Applications | Differential expression, novel transcripts, splicing, fusions, allele-specific expression [10] | Targeted differential expression, validation [9] | Differential expression (known transcripts) |

| Quantitative Nature | Digital (read counting) | Analog (fluorescence-based) | Analog (fluorescence-based) |

| Cost per Sample | Higher | Lower for limited targets | Moderate |

The Complementary Role of qPCR in RNA-seq Workflows

Rather than being a simple replacement, qPCR often works in tandem with RNA-seq to generate trustworthy results [9]. Its role is critical both upstream and downstream of an RNA-seq experiment:

- Upstream: TaqMan qPCR is commonly used to check cDNA integrity prior to library preparation for NGS, ensuring that input material is of sufficient quality [9].

- Downstream: qPCR remains the go-to method for validating RNA-seq results. For follow-up studies focusing on a targeted panel of transcripts discovered during the NGS screen, qPCR is the gold-standard technology [9] [8].

RNA-seq Experimental Design and Data Analysis

Core Workflow and Essential Bioinformatics Tools

A standard RNA-seq analysis involves several sequential steps, with critical decisions required at each stage. The diagram below illustrates this workflow and the common tool choices.

Figure 1: The core stages of an RNA-seq data analysis workflow and the associated bioinformatics tools for each step [11] [10].

Validating Differential Expression Analysis Methods

Given the variety of statistical tools available for identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs), independent validation is crucial. One study experimentally validated DEGs identified by four common methods (Cuffdiff2, edgeR, DESeq2, and TSPM) using high-throughput qPCR on independent biological samples [12].

Table 2: Performance of DEG Analysis Methods Validated by qPCR

| Method | Sensitivity | Specificity | False Positivity Rate | False Negativity Rate | Positive Predictive Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| edgeR | 76.67% | 90.91% | 9% | 23.33% | 90.20% |

| Cuffdiff2 | 51.67% | 45.45% | High (54.55%) | 48.33% | 39.24% |

| DESeq2 | 1.67% | 100% | 0% | 98.33% | 100% |

| TSPM | 5.00% | 90.91% | 9% | 95% | 37.50% |

The results highlight a significant trade-off: DESeq2 was the most specific but least sensitive method, while Cuffdiff2 generated a high false positivity rate. Among the tested methods, edgeR demonstrated the best balance of sensitivity and specificity, with a high positive predictive value, making its findings most likely to be confirmed by an independent gold-standard method like qPCR [12]. This underscores the need for careful tool selection based on the research goals—whether prioritizing novel discovery (favoring sensitivity) or confident validation of a smaller gene set (favoring specificity).

The Validation Loop: Integrating RNA-seq and qPCR

The relationship between RNA-seq and qPCR is not competitive but collaborative. The following diagram outlines a robust workflow for using these technologies together to ensure discovery and validation.

Figure 2: An integrated RNA-seq and qPCR workflow for discovery and validation, highlighting the critical step of appropriate gene selection [9] [8].

A critical, often neglected step in this process is the informed selection of reference genes for qPCR validation. Traditional housekeeping genes (e.g., ACTB, GAPDH) may exhibit variable expression under different biological conditions, leading to normalization errors and misinterpretation of results [8]. Tools like the Gene Selector for Validation (GSV) software now leverage RNA-seq data itself to identify the most stable, highly expressed reference genes and the most variable candidate genes for validation, ensuring reliable and cost-effective qPCR experiments [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Platforms for RNA-seq

| Item / Platform | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Library Prep Kits (e.g., NuGEN Ovation) | Convert RNA into sequence-ready cDNA libraries. | Protocol efficiency, bias correction, compatibility with low-input RNA. |

| TaqMan qPCR Assays | Validate RNA-seq results and check cDNA integrity. | Predesigned assays for most exon-exon junctions; require variant-specific design for isoform detection [9]. |

| Alignment & Quantification Tools (STAR, HISAT2, Salmon) | Map reads to a reference and quantify gene/transcript abundance. | STAR is fast but memory-intensive; HISAT2 has a smaller footprint; Salmon is alignment-free and fast [11]. |

| Differential Expression Software (DESeq2, edgeR, Limma-voom) | Statistically identify genes changed between conditions. | DESeq2 good for small-n studies; edgeR for well-replicated experiments; Limma-voom excels with large cohorts [11] [12]. |

| Integrated Commercial Platforms (Partek Flow, CLC Genomics) | GUI-based, end-to-end analysis from raw data to results. | Reduce bioinformatics burden; offer validated workflows for regulated environments [11]. |

| Single-Cell Platforms (Nygen, BBrowserX) | Analyze transcriptomes at single-cell resolution. | Handle cell clustering, annotation, and multi-omics integration; often cloud-based with AI-powered insights [13]. |

RNA-seq has firmly established itself as the premier technology for unbiased, genome-wide transcriptome exploration, enabling discoveries that are simply impossible with targeted approaches. Its power, however, does not render older methods like qPCR obsolete. Instead, a synergistic workflow, where RNA-seq drives hypothesis-free discovery and qPCR provides robust, targeted validation, represents the current gold standard in gene expression research. As the field continues to evolve with lower costs, longer reads, and integrated single-cell and spatial modalities [13], this foundational principle of collaborative technology application will continue to ensure the generation of reliable and impactful biological insights.

In transcriptomics research, a central question has long been whether gene expression data obtained through high-throughput sequencing technologies require validation by targeted amplification methods like quantitative PCR (qPCR). Next-generation sequencing (NGS), particularly RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), provides an unbiased, genome-wide view of the transcriptome, while qPCR offers high sensitivity and specificity for quantifying a limited number of targets. This guide objectively compares the technical performance of these two paradigms—broad sequencing and targeted amplification—within the context of differential gene expression analysis, providing researchers with the data needed to inform their validation strategies.

Core Technological Principles

Amplification-Based Quantification: qPCR

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) is a targeted method for gene expression analysis that relies on the enzymatic amplification of specific cDNA sequences. Its function is to quantify the abundance of a transcript by measuring the amplification kinetics, with the cycle threshold (Cq) indicating the starting quantity. The process involves reverse transcribing RNA into cDNA, followed by thermal cycling that uses DNA polymerase to exponentially amplify target sequences, with fluorescence intensity measured in real time to track product accumulation [4] [8].

Sequencing-Based Quantification: RNA-Seq

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) is a comprehensive method that determines the sequence of nucleotides in a population of RNA molecules. Its primary function is to identify and quantify the multitude of RNA transcripts in a sample, from known genes to novel isoforms. In the predominant short-read sequencing approach (e.g., Illumina), the workflow involves fragmenting RNA, converting it to cDNA, attaching adapters, and then using sequencing-by-synthesis chemistry on a massively parallel scale to generate billions of short reads that are subsequently mapped to a reference genome for quantification [14] [15] [16].

Direct Performance Comparison in Differential Expression

Independent benchmarking studies have systematically compared the performance of RNA-seq and qPCR for identifying differentially expressed genes, providing critical data for evaluating the need for validation.

A comprehensive benchmark study compared five RNA-seq analysis workflows against whole-transcriptome qPCR data for over 18,000 protein-coding genes. The results demonstrated a high overall correlation for gene expression fold changes between RNA-seq and qPCR, with Pearson correlation coefficients (R²) ranging from 0.927 to 0.934 across different computational methods [2].

The study revealed that approximately 85% of genes showed consistent differential expression calls between RNA-seq and qPCR. However, about 15% of genes showed non-concordant results, where the two methods disagreed on differential expression status or direction. Importantly, of these non-concordant genes, 93% had fold-change differences (ΔFC) of less than 2, and approximately 80% had ΔFC less than 1.5, indicating that most discrepancies were of small magnitude [4] [2].

Characteristics of Problematic Genes

Research indicates that the small fraction of genes with severe discrepancies (approximately 1.8%) are typically characterized by specific features. These non-concordant genes with ΔFC > 2 were predominantly shorter, lower expressed genes with fewer exons compared to genes with consistent expression measurements [4] [2].

Figure 1: Concordance and discrepancy patterns between RNA-seq and qPCR in differential expression analysis.

Experimental Design and Protocol Considerations

RNA-Seq Experimental Workflows

Multiple RNA-seq library preparation and sequencing protocols exist, each with distinct technical considerations that impact their performance relative to qPCR.

Short-Read vs. Long-Read Sequencing

The recent SG-NEx project systematically benchmarked five RNA-seq protocols, including short-read cDNA sequencing, Nanopore long-read direct RNA, amplification-free direct cDNA, PCR-amplified cDNA sequencing, and PacBio IsoSeq. The study found that while short-read data generate robust estimates for gene expression, long-read sequencing more reliably identifies major isoforms and complex transcriptional events, though with different cost and throughput considerations [17].

Amplification in Library Preparation

A rigorous 2024 comparison of Nanopore direct cDNA and PCR-cDNA sequencing for bacterial transcriptomes demonstrated that PCR-based amplification substantially improves sequencing yield with largely unbiased assessment of core gene expression. However, a small risk of technical bias was identified, which appeared greater for genes with unusually high (>52%) or low (<44%) GC content [18].

qPCR Validation Protocols

For rigorous validation of RNA-seq results by qPCR, specific methodological considerations are essential.

Reference Gene Selection

Traditional use of housekeeping genes (e.g., actin, GAPDH) as reference genes for normalization is problematic, as their expression can vary across biological conditions. Computational tools like Gene Selector for Validation (GSV) have been developed to identify optimal reference genes directly from RNA-seq data based on stability and expression level across experimental conditions [8].

The GSV algorithm applies multiple filtering criteria to select optimal reference genes:

- Expression >0 TPM in all samples

- Standard variation of log2(TPM) <1

- No exceptional expression in any library (<2× average log2 expression)

- Average log2 expression >5

- Coefficient of variation <0.2 [8]

Technical Comparison Tables

Performance Characteristics for Differential Expression

Table 1: Comparative performance of RNA-seq and qPCR for differential expression analysis

| Performance Metric | RNA-Seq | qPCR | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Genome-wide (all transcripts) | Targeted (dozens to hundreds) | [4] [2] |

| Fold Change Correlation | R² = 0.93-0.94 vs qPCR | Reference method | [2] |

| Concordance Rate | ~85% with qPCR | ~85% with RNA-seq | [4] [2] |

| Problematic Genes | Shorter, lower expressed genes with fewer exons | Less affected by transcript features | [4] [2] |

| Dynamic Range | Broad (~5-6 orders of magnitude) | Very broad (>7 orders of magnitude) | [4] |

Technical Specifications and Methodological Considerations

Table 2: Technical specifications and methodological requirements

| Characteristic | RNA-Seq | qPCR | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Input | 10 ng - 1 μg total RNA | 1 pg - 100 ng total RNA | [17] [18] |

| Amplification Required | Yes (library preparation) | Yes (target amplification) | [15] [18] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Very high (multiple samples per run) | Moderate (dozens of targets per run) | [15] |

| Hands-on Time | Moderate to high | Low to moderate | [18] |

| Data Analysis Complexity | High (bioinformatics expertise) | Low to moderate (standard curves) | [15] [8] |

| Cost per Sample | $50 - $1000+ | $5 - $50 | Platform dependent |

Decision Framework for Validation Requirements

When qPCR Validation Is Recommended

Evidence suggests that qPCR validation provides the most value in specific scenarios:

- When an entire biological conclusion rests on differential expression of only a few genes

- For genes with low expression levels and/or small fold changes (<1.5-2)

- When extending findings to additional samples, strains, or conditions beyond the original RNA-seq experiment [4]

- For specific challenging gene families, such as HLA genes, where moderate correlations (rho = 0.2-0.53) have been observed between RNA-seq and qPCR [3]

When RNA-Seq Stands Alone

Under optimal experimental conditions, RNA-seq data may not require qPCR validation:

- When studies include a sufficient number of biological replicates

- When following established minimum information guidelines (e.g., MINSEQE for sequencing, MIABiE for biofilm experiments)

- When using state-of-the-art data analysis pipelines

- For genes with moderate to high expression levels and substantial fold changes [4]

Figure 2: Decision framework for determining when qPCR validation of RNA-seq results is most beneficial.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key research reagents and their applications in amplification and sequencing workflows

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(A) Polymerase | Adds poly(A) tails to bacterial mRNA | Nanopore sequencing of prokaryotic transcriptomes [18] |

| RNase Inhibitor | Prevents RNA degradation during library prep | All RNA-seq workflows, especially long protocols [18] |

| Oligo(dT) Primers | Binds to poly(A) tails for cDNA synthesis | mRNA enrichment in eukaryotic transcriptomics [18] |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA | Bacterial RNA-seq to increase mRNA sequencing depth [18] |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesizes cDNA from RNA templates | Essential first step in both qPCR and RNA-seq [4] [8] |

| DNA Polymerase | Amplifies DNA templates | qPCR and amplification-based sequencing libraries [18] |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers | Tags individual molecules | Multiplexing samples in NGS library preparation [15] |

The choice between amplification and sequencing technologies for gene expression analysis involves balancing throughput, precision, and practical considerations. RNA-seq has matured to provide highly reliable differential expression results for the majority of genes, potentially reducing the need for systematic qPCR validation. However, targeted amplification remains indispensable for validating critical findings, particularly for low-expressed genes or those with challenging sequence features. By understanding the specific technical differences and performance characteristics outlined in this guide, researchers can make evidence-based decisions about when amplification-based validation is truly necessary, optimizing their experimental workflows for robust and efficient transcriptome analysis.

In differential expression research, the choice between quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) is foundational. While RNA-Seq provides a comprehensive, hypothesis-free view of the transcriptome, qPCR offers a sensitive, targeted, and highly precise approach for quantifying specific transcripts. The prevailing practice of using qPCR to validate RNA-Seq results is common, yet the relationship between these technologies is more nuanced than simple verification. A deeper understanding of their respective strengths, limitations, and optimal application spaces enables researchers to design more efficient and cost-effective studies. This guide objectively compares their performance based on experimental data, detailing methodologies to inform strategic decisions in biomedical research and drug development.

Performance and Capability Comparison

The following tables summarize the core technical and operational characteristics of qPCR and RNA-Seq, providing a direct comparison of their performance.

Table 1: Key Technical and Performance Specifications

| Feature | qPCR | Bulk RNA-Seq | Single-Cell/Nucleus RNA-Seq (sc/snRNA-Seq) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Low to medium (tens to hundreds of targets) | High (entire transcriptome) | Very High (thousands to millions of cells) |

| Sensitivity | Very High (can detect single copies) [19] | High (requires ~20-30M reads/sample for robust DGE) [20] | Low at single-cell level; improves with cell count [21] |

| Dynamic Range | ~7-8 logs | >5 logs | Constrained by high dropout rates [21] |

| Accuracy & Precision | High, mature technology | High for gene-level expression; lower for isoforms | Generally low at single-cell level [21] |

| Primary Application | Targeted quantification, validation | Discovery, differential expression, splicing | Cellular heterogeneity, rare cell types [21] [22] |

| Best Suited For | - Validating a limited number of genes- Low-abundance transcripts- High sample throughput studies | - Unbiased transcriptome discovery- Detecting novel transcripts/isoforms- Splice variant analysis | - Deconstructing cellular heterogeneity- Identifying novel cell types/states- Developmental trajectories |

Table 2: Cost and Workflow Considerations

| Consideration | qPCR | RNA-Seq (using Illumina TruSeq on NovaSeq S4 flow cell) |

|---|---|---|

| Cost per Sample (Library Prep & Sequencing) | Low (cost-effective for few targets) | ~$36.9 - $113.9, highly dependent on multiplexing and read depth [23] |

| Hands-on Time | Low (workflow is simple and fast) | ~3-4 days [23] |

| Data Analysis Complexity | Low (straightforward ΔΔCq method) | High (requires bioinformatics expertise) [20] [22] |

| Required Replicates | 3+ (standard for statistical power) | Minimum 3+; more needed for high variability [20] |

| Key Cost/Design Drivers | - Number of targets- Number of samples | - Library prep method ($24-$68.7/sample) [23]- Sequencing depth (5M-30M+ reads/sample) [23]- Level of multiplexing [23] |

Experimental Data and Validation Paradigms

When is qPCR Validation Appropriate?

The requirement for qPCR validation of RNA-Seq data is context-dependent. It is most appropriate in two key scenarios:

- For Independent Confirmation: When a second, orthogonal method is required to confirm a critical finding, such as for publication in a high-impact journal where reviewers demand confirmation via a different technical approach [24].

- For Underpowered RNA-Seq Studies: When the original RNA-Seq data is based on a small number of biological replicates, limiting the statistical power. Using qPCR to assay more samples for a focused set of targets can validate and extend the study findings [24].

A Case Study in Ovarian Cancer Diagnostics

A 2025 study on ovarian cancer detection provides a clear example of the complementary strengths of these technologies. Researchers used RNA-Seq as a discovery tool to analyze platelet RNA from patient blood samples, identifying a panel of 10 splice-junction-based biomarkers that differentiated ovarian cancer from benign conditions [25].

Subsequently, they developed a qPCR-based algorithm for clinical application. This targeted approach demonstrated 94.1% sensitivity and 94.4% specificity (AUC = 0.933) [25]. The study highlights a powerful workflow: using RNA-Seq's broad profiling capability for biomarker discovery, then leveraging qPCR's accessibility, low cost, and simplicity for a robust, deployable diagnostic test, especially where NGS is too costly for widespread use [25].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: High-Sensitivity qPCR for Low-Abundance Transcripts (STALARD Method)

Background: Conventional RT-qPCR becomes unreliable for quantification cycle (Cq) values above 30-35 [19]. The STALARD (Selective Target Amplification for Low-Abundance RNA Detection) method overcomes this by incorporating a targeted pre-amplification step [19].

Methodology:

Primer Design:

- Design a Gene-Specific Primer (GSP) that matches the known 5'-end sequence of the target RNA (with T substituted for U). The GSP should have a Tm of ~62°C and 40-60% GC content.

- Synthesize a GSP-tailed oligo(dT) primer (GSoligo(dT)), which is an oligo(dT)24VN primer with the GSP sequence at its 5' end [19].

Reverse Transcription:

- Perform first-strand cDNA synthesis using 1 µg of total RNA and the GSoligo(dT) primer. This produces cDNA molecules that have the GSP sequence incorporated at both ends [19].

Targeted Pre-amplification:

- Perform a limited-cycle PCR (9-18 cycles) using only the GSP. This selectively amplifies the full-length cDNA of the target transcript.

- Reaction Setup:

- 1 µL of cDNA from step 2.

- 1 µL of 10 µM GSP.

- SeqAmp DNA Polymerase (Takara) [19].

- Thermal Cycling:

- 95°C for 1 min (initial denaturation).

- 9-18 cycles of: 98°C for 10 s, 62°C for 30 s, 68°C for 1 min/kb.

- 72°C for 10 min (final extension) [19].

Purification and Quantification:

- Purify the PCR product using AMPure XP beads.

- Use the purified product as the template for standard qPCR quantification with isoform-specific primers [19].

Protocol: Bulk RNA-Seq Library Preparation and Sequencing

Background: This protocol outlines the standard workflow for bulk RNA-Seq, which is the foundation for differential expression analysis [20].

Methodology:

RNA Extraction and QC:

- Extract total RNA using a solvent-based method (e.g., TRIzol, ~$2.2/sample) or a silica-based column kit (e.g., QIAgen RNeasy, ~$7.1/sample) [23].

- Assess RNA quality and integrity using an instrument like the Bioanalyzer. An RNA Integrity Number (RIN) ≥ 7 or distinct ribosomal RNA peaks are typically required [25].

Library Preparation:

- Option 1 (Standard): Use a kit like Illumina's TruSeq Stranded mRNA (~$64.4/sample) which involves mRNA enrichment, fragmentation, reverse transcription, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification [23].

- Option 2 (Cost-Effective): Use a 3'-end multiplexing kit like the Alithea MERCURIUS BRB-seq kit (~$24/sample), which uses early barcoding and pooling to drastically reduce costs [23].

- Critical Parameter: The number of PCR cycles during amplification must be optimized. Using more cycles than recommended for a given RNA input (e.g., <125 ng) leads to a high rate of PCR duplicates, reduced library complexity, and increased noise [26].

- Check final library quality and fragment size using a Bioanalyzer DNA chip [23].

Sequencing:

Technology Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the key procedural steps for RNA-Seq and qPCR, highlighting their divergent paths from sample to answer.

Diagram 1: Technology Workflow Comparison. This graph contrasts the comprehensive, sequencing-driven RNA-Seq pathway with the streamlined, amplification-focused qPCR pathway, showing their divergence based on the experimental goal.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Kits for RNA Expression Analysis

| Reagent/Kits | Primary Function | Example Products & Cost |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality total RNA from samples. | - TRIzol (~$2.2/sample) [23]- QIAgen RNeasy Kit (~$7.1/sample) [23] |

| RNA Quality Control | Assess RNA integrity (RIN) and quantity. | - Agilent Bioanalyzer RNA-6000 Nano Kit (~$4.1/sample) [23] |

| qPCR Master Mix | Provides enzymes, dNTPs, and buffer for efficient and specific amplification. | - Not specified in search results, but numerous commercial options exist (e.g., from Bio-Rad, Thermo Fisher). |

| RNA-Seq Library Prep Kits | Convert RNA into sequencer-ready DNA libraries. | - Illumina TruSeq mRNA Stranded (~$64.4/sample) [23]- NEBnext Ultra II RNA (~$37/sample) [23]- Alithea MERCURIUS BRB-seq (~$19.7/sample) [23] |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences added to RNA fragments to tag and identify PCR duplicates [26]. | - Incorporated into many modern library prep kits. |

The decision between qPCR and RNA-Seq is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with research goals. RNA-Seq is the undisputed tool for unbiased discovery, profiling entire transcriptomes, and detecting novel features. qPCR excels in targeted quantification, offering high sensitivity, low cost, and operational simplicity for validating key findings or conducting high-throughput screens of known targets.

A modern, robust approach involves using these technologies in concert: leveraging RNA-Seq's power for initial discovery and then employing qPCR's precision for validation and expansion on larger sample cohorts. Furthermore, best practices in experimental design—such as including sufficient biological replicates, optimizing PCR cycles to minimize duplicates, and utilizing UMIs—are critical for ensuring the reliability of data from either technology, ultimately leading to more reproducible and impactful scientific outcomes.

Designing Your Workflow: From RNA-seq Discovery to qPCR Confirmation

The debate in transcriptomics research often positions quantitative PCR (qPCR) and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) as competing technologies. However, a more powerful approach emerges when they are used as complementary tools within an integrated workflow. RNA-seq provides an unbiased, genome-wide view of the transcriptome, enabling novel discovery, while qPCR delivers highly sensitive, specific, and reproducible quantification for targeted gene analysis. This guide objectively compares their performance and demonstrates how their strategic integration—using qPCR both upstream to ensure input quality and downstream to verify key findings—creates a robust framework for reliable gene expression research, ultimately strengthening experimental conclusions for drug development and clinical applications [9] [24].

Core Principles and Comparative Strengths

qPCR is a targeted technique that quantifies the amplification of specific cDNA sequences in real-time using fluorescent reporters. Its maturity, simplicity, and low operational cost make it the gold standard for validating a limited number of genes with high sensitivity and a wide dynamic range [9] [24].

RNA-seq is a discovery-oriented technology that involves converting RNA into a library of cDNA fragments, sequencing them using high-throughput platforms (e.g., Illumina, Nanopore, PacBio), and aligning the resulting millions of short reads to a reference genome to determine transcript abundance and structure [27] [28].

Table: Core Technical Comparison of qPCR and RNA-seq

| Feature | qPCR | RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Low (dozens to hundreds of targets) | High (entire transcriptome) |

| Target Selection | Requires a priori knowledge | Unbiased, capable of novel discovery |

| Sensitivity & Dynamic Range | High | Sufficient for most applications, though highly sensitive detection requires deep sequencing [9] |

| Primary Output | Cycle threshold (Cq) | Read counts (e.g., raw counts, TPM) |

| Key Advantage | High reproducibility, low cost per target, simple workflow | Comprehensive coverage, can detect novel transcripts, isoforms, and fusions [9] [28] |

| Typical Cost & Time | Lower cost and faster for studies with few targets/samples [9] | Higher cost and longer turnaround, especially when outsourced [9] |

The Integrated Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the synergistic workflow of using qPCR at critical points before and after RNA-seq.

Diagram: Integrated qPCR and RNA-seq Workflow. qPCR is used upstream to check cDNA quality before RNA-seq and downstream to validate key findings on new samples.

The Upstream Role: Using qPCR for Quality Control

The sensitivity and accuracy of RNA-seq are fundamentally dependent on the quality and quantity of the input RNA and cDNA [29]. Using qPCR upstream provides a functional quality check that is more specific than spectrophotometry.

Experimental Protocol: cDNA Integrity Check

This protocol is used prior to costly RNA-seq library preparation to confirm that reverse transcription has been successful.

- Step 1: RNA Quantification. Isolate total RNA using a dedicated kit (e.g., PureLink RNA Mini Kit, MagMAX-96 Total RNA Isolation Kit). Quantify RNA precisely using a fluorometric method like the Qubit RNA assay, which is more specific and sensitive for RNA than UV absorbance readings from a NanoDrop, as it minimizes interference from contaminants [29].

- Step 2: Reverse Transcription. Synthesize first-strand cDNA using a high-performance reverse transcriptase master mix (e.g., SuperScript IV VILO Master Mix). This step is critical for reducing amplification bias and ensuring superior linearity across a broad range of input material [29].

- Step 3: qPCR Quality Control. Perform qPCR on the resulting cDNA using TaqMan Gene Expression Assays targeting a set of stable, well-characterized housekeeping genes (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB). The criteria for passing this QC step include [9]:

- Low Cq Values: The quantification cycle (Cq) for control genes should be low and consistent across samples, indicating efficient cDNA synthesis from high-quality RNA.

- Minimal Replicate Variation: Technical replicates should show low variability (e.g., Cq standard deviation < 0.2).

- Step 4: Proceed to Library Prep. Only samples passing the cDNA QC threshold should proceed to RNA-seq library preparation, ensuring that sequencing resources are not wasted on degraded or inefficiently converted samples.

The Downstream Role: Using qPCR for Validation and Follow-up

Following RNA-seq and bioinformatic analysis, qPCR is deployed downstream to verify the expression patterns of a subset of critical genes, thereby bolstering confidence in the RNA-seq results.

Experimental Protocol: Validating Differential Expression

This protocol is for independently confirming the differential expression of key genes identified by RNA-seq.

- Step 1: Select Key Targets. From the RNA-seq results, select genes of high biological interest (e.g., most significantly differentially expressed genes, genes central to a key pathway). The number of targets is typically limited to what fits on a 96- or 384-well qPCR plate.

- Step 2: Choose an Independent Sample Set. For the most robust validation, perform qPCR on a new, larger set of biological replicates that were not used in the initial RNA-seq experiment. This validates both the technology and the underlying biology [24].

- Step 3: Perform qPCR with Rigorous Design. Use a pre-designed platform like TaqMan Array plates or cards for efficiency. The experiment must be designed with proper biological replication (e.g., n ≥ 3 per group) and technical replication (e.g., duplicates or triplicates per sample). It is crucial to use stable reference genes selected specifically for the biological system under study [8].

- Step 4: Data Analysis and Concordance Check. Analyze qPCR data using the ΔΔCq method. Determine concordance by comparing the direction (up/down-regulated) and magnitude (fold-change) of expression differences between the RNA-seq and qPCR results.

Evidence for Concordance and Its Limits

A comprehensive benchmark study analyzing over 18,000 protein-coding genes found a high level of concordance between RNA-seq and qPCR, with only about 1.8% of genes showing severe non-concordance. Notably, the majority of non-concordant results occurred in genes with low expression levels (fold-change < 2) [4]. This evidence supports the practice of using qPCR for validation, while also highlighting that validation is most critical when a study's conclusions hinge on a few genes, particularly those with low expression or small fold-changes [4] [24].

Table: Scenarios for Downstream qPCR Validation

| Scenario | Appropriate for qPCR Validation? | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Small number of RNA-seq replicates | Yes, highly appropriate [24] | qPCR on a larger sample set statistically confirms the biological effect. |

| Conclusions rely on a few key, low-expression genes | Yes, highly appropriate [4] | Confirms findings in a domain where RNA-seq pipelines can be variable [30]. |

| RNA-seq is a hypothesis-generating screen | Often unnecessary [24] | Resources are better directed toward functional protein-level studies. |

| Planning a larger, confirmatory RNA-seq study | Unnecessary [24] | The subsequent RNA-seq study itself serves as validation. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and their functions for executing the integrated workflow.

Table: Essential Reagents for the qPCR and RNA-seq Workflow

| Product Category | Example Products | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation Kits | PureLink RNA Mini Kit, MagMAX-96 Total RNA Isolation Kit, mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit, RNAqueous-Micro Kit [29] | Purify high-quality RNA from various sample types (fresh/frozen cells, tissue, FFPE), with options for total RNA or specific RNA-size populations. |

| RNA Quantification Assays | Qubit RNA Assay, Quant-iT RNA Assay [29] | Provide specific, sensitive quantification of RNA concentration with minimal interference from common contaminants, superior to UV absorbance. |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | SuperScript IV VILO Master Mix [29] | Generate high-quality first-strand cDNA with reduced amplification bias, available in convenient single-tube formats. |

| qPCR Assays & Plates | TaqMan Gene Expression Assays, TaqMan Array Plates (96- or 384-well), TaqMan OpenArray Plates [9] | Enable highly specific and reproducible quantification of targeted gene expression, available in various throughput formats to suit experimental scale. |

| RNA-seq Library Prep Kits | TruSeq stranded mRNA kit (Illumina), SureSelect XTHS2 RNA kit (Agilent) [31] | Prepare sequencing libraries from RNA, often involving mRNA enrichment, fragmentation, adapter ligation, and index addition. |

| Reference Gene Selection Software | GSV (Gene Selector for Validation) Software [8] | Identifies the most stable and highly expressed reference genes from RNA-seq data (TPM values) for optimal normalization in downstream qPCR validation. |

The question is not whether to use qPCR or RNA-seq, but how to best use them together. The integrated workflow—employing qPCR upstream for quality control of cDNA and downstream for validation of critical findings on independent samples—creates a powerful, self-reinforcing cycle of discovery and verification. This approach maximizes data integrity, increases confidence in results for manuscript publication, and provides a cost-effective strategy for robust transcriptomic analysis in research and drug development. By understanding the distinct strengths and optimal applications of each technology, scientists can design more reliable and impactful gene expression studies.

Within the context of gene expression analysis, the choice between RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) is not necessarily an either/or decision. While qPCR remains the gold standard for targeted gene expression quantification due to its wide dynamic range, low quantification limits, and cost-effectiveness for analyzing a limited number of genes, RNA-seq provides an unbiased, genome-scale view of the transcriptome [9] [32]. A critical component of harnessing the power of RNA-seq is the construction of a robust bioinformatics pipeline, the design of which directly impacts the accuracy, reproducibility, and biological validity of the results [33] [34]. This guide objectively compares the performance of common tools and methods for alignment, quantification, and normalization, providing supporting experimental data to inform researchers and drug development professionals designing pipelines for differential expression research.

RNA-seq Workflow and Key Decision Points

A typical RNA-seq data analysis begins with raw sequencing reads and proceeds through a series of preprocessing steps before biological interpretation can occur. The key stages and the choices made at each point significantly influence the downstream results [33].

Key stages and tool choices in the RNA-seq preprocessing pipeline [33].

Experimental Insights from Multi-Center Benchmarking

Large-scale benchmarking studies provide critical empirical data on how pipeline choices affect real-world outcomes. A landmark study involving 45 laboratories, which generated over 120 billion reads from 1080 libraries, systematically evaluated 26 experimental processes and 140 bioinformatics pipelines [34]. This study revealed that each bioinformatics step, as well as experimental factors like mRNA enrichment and library strandedness, are primary sources of variation in gene expression measurements. Notably, inter-laboratory variations were significantly greater when detecting subtle differential expression—a common scenario in clinical diagnostics—compared to large expression differences [34].

Alignment Tools: Performance Comparison

The alignment (or mapping) step involves matching sequencing reads to a reference transcriptome or genome to identify their genomic origin. Researchers can choose between traditional alignment-spliced alignment tools and pseudoalignment methods, which estimate transcript abundances without base-by-base alignment [33].

Table 1: Comparison of RNA-seq Alignment and Quantification Tools

| Tool | Type | Key Features | Considerations | Benchmarking Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAR [33] | Spliced Aligner | Aligns non-contiguous reads across introns; precise mapping | Higher computational memory requirements | Widely used; performance varies with library preparation [34] |

| HISAT2 [33] | Spliced Aligner | Memory-efficient; fast alignment using global FM index | Common in benchmarks; influenced by experimental protocol [34] | |

| TopHat2 [33] | Spliced Aligner | Early standard for spliced alignment; uses Bowtie2 | Largely superseded by STAR and HISAT2 | |

| Kallisto [33] [31] | Pseudoaligner | Ultra-fast; uses kallisto index for abundance estimation; bootstrapping for uncertainty | Does not produce base-by-base genomic coordinates | Faster, less memory; accurate for expression estimation [33] |

| Salmon [33] | Pseudoaligner | Fast, bias-corrected quantification; models fragment GC-content bias | Does not produce base-by-base genomic coordinates | Faster, less memory; accurate for expression estimation [33] |

Quantification and Normalization Strategies

Following alignment, reads are assigned to genomic features such as genes or transcripts (quantification), and the resulting counts are adjusted to make samples comparable (normalization).

Read Quantification

Quantification tools generate a raw count matrix, where the number of reads mapped to each gene in each sample is summarized. A higher number of reads indicates higher expression of that gene [33]. Tools like featureCounts and HTSeq-count are commonly used for this purpose when starting from aligned BAM files. Alternatively, pseudoaligners like Kallisto and Salmon perform alignment and quantification simultaneously, outputting transcript abundances directly [33] [31].

Normalization Methods

Normalization is a critical statistical adjustment to remove technical biases, such as differences in sequencing depth between samples. Without proper normalization, samples with more total reads would appear to have higher gene expression across the board, obscuring true biological differences [33].

Table 2: Common RNA-Seq Normalization Methods and Their Applications

| Method | Sequencing Depth Correction | Gene Length Correction | Library Composition Correction | Suitable for DE Analysis | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM (Counts per Million) [33] | Yes | No | No | No | Simple scaling by total reads; highly affected by a few highly expressed genes. |

| RPKM/FPKM [33] | Yes | Yes | No | No | Enables within-sample comparison; not for cross-sample comparison due to composition bias. |

| TPM (Transcripts per Million) [33] | Yes | Yes | Partial | No | Scales sample to a constant total (1 million); good for cross-sample comparison. |

| Median-of-Ratios (DESeq2) [33] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Robust to composition bias; assumed majority of genes are not differentially expressed. |

| TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values, edgeR) [33] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Robust to composition bias; similar assumptions to median-of-ratios. |

The choice of normalization method is pivotal for the accuracy of differential gene expression (DGE) analysis. Methods like CPM, FPKM, and TPM are not considered suitable for DGE analysis because they do not adequately correct for library composition biases. In contrast, the median-of-ratios method (used by DESeq2) and the TMM method (used by edgeR) are specifically designed for this purpose and incorporate statistical models that account for inter-sample variability [33].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

Large-Scale Multi-Center Benchmarking Design

The design of the Quartet project provides a robust template for evaluating RNA-seq pipelines [34]:

- Reference Materials: Four well-characterized RNA samples from a family quartet (parents and monozygotic twins) with small biological differences, spiked with ERCC RNA controls. MAQC samples with larger biological differences were used in parallel.

- Sample Mixing: Two additional samples (T1, T2) were created by mixing two Quartet samples at defined ratios (3:1 and 1:3), providing a built-in truth for ratio-based expression changes.

- Data Generation and Analysis: 45 independent laboratories processed the same sample panel using their in-house experimental protocols and bioinformatics pipelines (totaling 140 distinct pipelines). This design captured real-world technical variation.

- Performance Metrics: Accuracy was assessed against multiple ground truths, including TaqMan qPCR data (for absolute expression), known spike-in concentrations (ERCC), and expected mixing ratios. Reproducibility was measured across technical replicates and laboratories [34].

Protocol for Cross-Study Predictive Performance

To assess how preprocessing affects a pipeline's generalizability, the following protocol can be implemented [35]:

- Dataset Splitting: A large dataset (e.g., TCGA with ~7,870 samples) is split into training (80%) and internal test (20%) sets.

- Independent Validation: The model is tested on completely independent datasets (e.g., GTEx with ~3,340 samples or combined ICGC/GEO with ~876 samples).

- Preprocessing Variations: Different combinations of normalization (e.g., Quantile Normalization), batch effect correction (e.g., ComBat), and data scaling are applied to the training set.

- Model Training and Evaluation: A classifier (e.g., Support Vector Machine) is trained on the preprocessed data and evaluated on the independent test sets. Performance metrics (e.g., F1-score) reveal which preprocessing steps improve cross-study predictions [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Software for RNA-seq Analysis

| Item | Function | Example Products/Tools |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation Kit | Purifies intact, high-quality total RNA from samples. | AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen), AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit (Qiagen) [31]. |

| Library Prep Kit | Converts RNA into a sequenceable library; often includes mRNA enrichment and adapter ligation. | TruSeq stranded mRNA kit (Illumina), SureSelect XTHS2 RNA kit (Agilent) [31] [36]. |

| Quality Control Software | Assesses raw read quality, adapter contamination, and other potential issues. | FastQC, multiQC, RSeQC [33] [31]. |

| Alignment Software | Maps sequencing reads to a reference genome/transcriptome. | STAR, HISAT2 [33] [31]. |

| Quantification Software | Counts the number of reads mapped to each gene or transcript. | featureCounts, HTSeq-count, Kallisto, Salmon [33] [31]. |

| Differential Expression Tools | Performs statistical analysis to identify genes expressed at different levels between conditions. | DESeq2, edgeR [33]. |

Designing an RNA-seq pipeline requires careful consideration of the trade-offs associated with each tool and method. Large-scale benchmarking studies reveal that the choices for alignment, quantification, and normalization are not merely technical details but are primary sources of variation that can significantly impact results, especially when seeking to identify subtle differential expression [34]. While pseudoalignment tools like Kallisto and Salmon offer speed advantages, traditional aligners like STAR provide genomic mapping. For normalization, methods embedded in dedicated DGE tools like DESeq2 and edgeR are specifically designed for robust cross-sample comparison. The optimal pipeline is often dictated by the specific biological question, the required precision, and the available computational resources. Furthermore, in the broader context of RNA-seq and qPCR, the two methods are frequently complementary; qPCR serves as a valuable independent technique for validating key findings from large-scale RNA-seq screens [9].

Selecting Optimal Reference Genes for qPCR Using RNA-seq Data

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) remains the gold standard technique for validating gene expression data obtained from high-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) due to its superior sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility [37]. However, the accuracy of qPCR data critically depends on proper normalization to account for technical variations introduced during RNA isolation, reverse transcription, and amplification [37]. Inadequate normalization can lead to misinterpretation of biological results, with false positives or negatives potentially exceeding 20-fold in extreme cases [37].

The traditional approach utilizes reference genes (RGs)—preferably multiple—that are stably expressed across all experimental conditions [38]. The Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines strongly recommend validating reference genes for each specific experimental system [38] [39]. With the exponential growth of publicly available RNA-seq datasets, researchers now have an unprecedented opportunity to mine these resources for identifying optimal reference genes in silico before laboratory validation [40]. This guide comprehensively compares methods for selecting reference genes using RNA-seq data, providing researchers with actionable protocols and performance evaluations.

Methodological Framework: From RNA-seq Data to Validated Reference Genes

RNA-seq Mining for Stable Gene Identification

The foundational approach involves computational mining of RNA-seq datasets to identify genes with stable expression across diverse conditions relevant to your experimental design. This method leverages large-scale transcriptomic data to pre-screen potential reference genes before laboratory validation.

Experimental Protocol:

- Dataset Curation: Compile RNA-seq data encompassing the biological conditions of interest (e.g., tissues, treatments, developmental stages). The tomato study utilized TomExpress database containing 394 biological conditions [40].

- Expression Quantification: Extract normalized expression values (e.g., TPM, FPKM) for all genes across all samples.

- Stability Calculation: Calculate expression stability statistics for each gene, typically focusing on variance or coefficient of variation across samples.

- Candidate Selection: Identify genes with lowest variation, ensuring they have appropriate expression levels (Cq values between 20-30 for optimal qPCR quantification) [40].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Traditional Housekeeping Genes Versus RNA-seq Identified Genes

| Gene Category | Example Genes | Mean Cq Range | Stability (LVS)* | Tissue Variability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical HKGs | GAPDH, ACTB, TUB | 18-25 | Variable (0.1-0.9) | High across tissues |

| RNA-seq Identified | IMP-b, RPS18, STAU1 | 20-26 | Consistently high (>0.8) | Low across tissues |

| Low Variance Genes | Ta2776, Ref2, Ta3006 | 22-28 | Highest (>0.95) | Minimal variability |

LVS: Low Variance Score, where 1 represents the most stable gene among those with similar expression levels [40].

The Gene Combination Method

A more sophisticated approach identifies optimal combinations of genes whose expressions balance each other across experimental conditions, even when individual genes show some variability [40]. This method recognizes that a combination of non-stable genes may provide more robust normalization than single stable genes.

Experimental Protocol:

- Target Gene Mean Calculation: Determine the mean expression level of your target gene from RNA-seq data.

- Candidate Pool Selection: Extract the top 500 genes with mean expressions similar to or greater than your target gene [40].

- Combination Optimization: Systematically test all possible geometric and arithmetic combinations of k genes (typically k=2-4) to identify sets where expressions counterbalance.

- Stability Assessment: Select the optimal combination based on two criteria: geometric mean ≥ target gene mean expression, and lowest variance among arithmetic means [40].

Alternative Normalization Strategies

While reference genes remain the most common approach, alternative normalization methods can be preferable in specific scenarios. The global mean (GM) method calculates the average expression of all reliably detected genes in a sample and uses this value for normalization [41]. Algorithm-based approaches like NORMA-Gene use least squares regression to calculate a normalization factor that minimizes technical variation across samples [38].

Table 2: Comparison of Normalization Methods for qPCR Data

| Normalization Method | Minimum Genes Required | Best Application Context | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Reference Gene | 1 | Preliminary studies with limited targets | Variable; high risk of bias |

| Multiple Reference Genes | 2-3 | Standard gene expression studies | CV: 0.275-0.356 [41] |

| Global Mean (GM) | 55+ | High-throughput qPCR (≥55 genes) | Lowest mean CV across tissues [41] |

| NORMA-Gene | 5+ | Studies with no optimal reference genes | Better variance reduction than RGs [38] |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Direct Method Comparison in Experimental Systems

Recent studies have directly compared the performance of different normalization strategies. In canine gastrointestinal tissues, the global mean method outperformed reference gene-based approaches when profiling 81 genes, showing the lowest coefficient of variation across tissues and pathological conditions [41]. In sheep liver studies, NORMA-Gene provided more reliable normalization than traditional reference genes, particularly for oxidative stress genes like GPX3, where interpretation of treatment effects differed significantly between methods [38].

The gene combination method demonstrated particular superiority in tomato studies, where combinations of non-stable genes identified through RNA-seq mining outperformed both classical housekeeping genes and single low-variance genes [40]. This approach recognizes that co-regulated genes with counterbalancing expression patterns can provide more robust normalization than individual stably expressed genes.

Impact on Biological Interpretation

The choice of normalization strategy directly impacts biological conclusions. In wheat studies, normalization using appropriate reference genes (Ref2 and Ta3006) revealed significant differences between absolute and normalized expression values for the TaIPT5 gene across most tissues, while results for TaIPT1 remained consistent regardless of normalization method [42]. This highlights how gene-specific characteristics influence normalization sensitivity.

Diagram 1: RNA-seq to qPCR Reference Gene Pipeline

Implementation Protocols

Laboratory Validation Workflow

After in silico identification of candidate reference genes through RNA-seq mining, rigorous laboratory validation is essential.

Experimental Protocol:

- Primer Design: Design primers with melting temperatures of 57-60°C, GC content of 50-70%, and product sizes of 70-200 base pairs, ensuring they span exon-exon junctions [38].

- Specificity Verification: Confirm primer specificity through sequencing of PCR products and melting curve analysis with single peaks [38] [42].

- Efficiency Calculation: Perform serial dilutions to determine PCR efficiency (ideally 90-110%) using the formula E = 10^(-1/slope) - 1 [41].

- Stability Validation: Analyze candidate gene expression across all experimental conditions using multiple algorithms (geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper) [43] [42].

- Comprehensive Ranking: Utilize RefFinder or BruteAggreg to integrate results from all algorithms for final ranking [43] [38].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Common challenges in reference gene selection include unexpected variability of classical housekeeping genes, insufficient expression stability across conditions, and co-regulation of candidate genes. Ribosomal protein genes frequently show high stability but should not be used exclusively due to potential co-regulation [41]. When traditional reference genes prove unstable, consider algorithm-based approaches like NORMA-Gene or the global mean method, particularly when profiling large gene sets [38] [41].

Diagram 2: Normalization Method Decision Tree

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Reference Gene Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Specification Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization | Preserves RNA integrity during storage | RNAlater for tissue preservation [41] |

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality total RNA | RNeasy kits; check RIN/RQI values [38] [37] |

| Reverse Transcriptase | cDNA synthesis from RNA templates | Multiscribe Reverse Transcriptase with random hexamers [38] [44] |

| qPCR Master Mix | Amplification with fluorescence detection | SYBR Green I or TaqMan probes [37] [44] |

| Stability Analysis Software | Reference gene validation | GeNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, RefFinder [43] [38] |

| RNA-seq Databases | In silico reference gene mining | TomExpress (plants), GEO (general) [40] |

The integration of RNA-seq data with qPCR experimental design represents a paradigm shift in reference gene selection. Rather than relying on presumed housekeeping genes, researchers can now make evidence-based decisions using comprehensive transcriptomic datasets. The gene combination method emerging from tomato studies demonstrates that optimal normalization may involve multiple genes whose expressions balance each other, rather than individually stable genes [40].

For researchers designing qPCR validation studies, the following evidence-based recommendations are proposed:

- Prioritize RNA-seq Mining: Whenever possible, leverage existing RNA-seq data from your experimental system to pre-screen candidate reference genes in silico [40].

- Implement Combinatorial Approaches: Explore combinations of 2-4 genes identified through RNA-seq analysis, as these often outperform single reference genes [40].

- Validate Extensively: Laboratory validation across all experimental conditions remains essential, using multiple algorithms for comprehensive stability assessment [43] [42].

- Consider Alternatives: For large gene sets (>55 genes), the global mean method provides excellent normalization without requiring reference gene validation [41].

This comparative analysis demonstrates that RNA-seq informed reference gene selection significantly enhances the accuracy and reliability of qPCR data normalization, ultimately strengthening gene expression studies in both basic research and drug development applications.

In the field of gene expression analysis, a fundamental challenge persists: how to reliably interpret and validate differences in gene expression across measurement platforms. The convergence of high-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and highly specific quantitative PCR (qPCR) technologies has created a critical need for standardized approaches to assess expression concordance. For researchers in drug development and biomedical research, the accurate identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) has direct implications for understanding disease mechanisms, identifying therapeutic targets, and developing biomarkers. This guide examines the core principles of expression concordance assessment, focusing on the complementary roles of correlation coefficients and fold-change measurements in validating transcriptomic data across platforms.

The relationship between RNA-seq and qPCR is inherently synergistic rather than competitive. While RNA-seq provides an unbiased, genome-wide discovery platform, qPCR offers a targeted, highly sensitive validation approach [43] [45]. This complementary relationship necessitates robust methods for cross-platform validation, where correlation statistics quantify the strength of agreement between measurements, and fold-change values assess the magnitude and biological significance of expression differences [46]. Understanding how to interpret these metrics in tandem is essential for establishing confidence in expression findings and ensuring research reproducibility.

Foundational Concepts: Correlation and Fold-Change

Correlation Analysis in Expression Studies

Correlation coefficients, particularly Pearson's r and Spearman's ρ, serve as primary metrics for assessing the technical agreement between RNA-seq and qPCR platforms. These statistics measure how consistently both platforms rank gene expression levels across samples, with values closer to 1.0 indicating perfect agreement. Pearson correlation assesses linear relationships, while Spearman correlation captures monotonic relationships, making the latter more robust to outliers and non-linear amplification effects common in qPCR [47]. High correlation values (typically r > 0.85-0.90) provide confidence that expression patterns detected by RNA-seq reflect true biological signals rather than technical artifacts.

Correlation analysis primarily validates the directional consistency of expression measurements but does not directly address the accuracy of fold-change magnitude. This limitation necessitates complementary analysis using fold-change metrics, particularly for genes with large expression differences where accurate quantification is critical for biological interpretation. The strength of correlation can be influenced by multiple factors including expression level (highly expressed genes typically show better correlation), gene length, and the dynamic range of detection for each platform [47] [17].

Fold-Change as a Biological Significance Metric

Fold-change represents the magnitude of expression difference between conditions and serves as a primary metric for assessing biological significance. In contrast to correlation, fold-change quantification focuses specifically on the effect size that drives biological interpretation. The log2 fold-change (LFC) transformation is standard practice, as it produces symmetric values (e.g., LFC of 1 = 2-fold upregulation, LFC of -1 = 2-fold downregulation) and improves statistical properties for downstream analysis [46].

A critical challenge in fold-change interpretation stems from the systematic differences between platforms. RNA-seq fold-change estimates can be influenced by normalization methods, sequencing depth, and data transformation approaches [46] [48], while qPCR fold-change calculations depend heavily on proper reference gene selection and amplification efficiency corrections [43] [40]. These methodological differences can lead to discrepancies in absolute fold-change magnitude even when directional consistency remains high. Establishing pre-defined thresholds for biological significance (commonly LFC > 1 or 2) helps standardize interpretation across platforms and experimental designs [46].

Quantitative Comparison of RNA-seq and qPCR Platforms

Table 1: Technical Comparison of RNA-seq and qPCR Platforms for Gene Expression Analysis

| Feature | RNA-seq | qPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Genome-wide, discovery-oriented [49] | Targeted, validation-focused [45] |

| Dynamic Range | >5 orders of magnitude [47] | 6-8 orders of magnitude [45] |

| Sensitivity | Detects low-abundance transcripts [46] | High sensitivity for rare transcripts [45] |

| Fold-Change Accuracy | Varies by method; DESeq2 recommended for n≥6 [48] | Highly accurate with proper normalization [43] |

| Sample Throughput | High (multiple samples simultaneously) | Medium to high (plate-based) |

| Cost per Sample | Higher | Lower |

| Technical Variability | Moderate; improved with larger sample sizes [49] [48] | Low with technical replicates |

Table 2: Performance of RNA-seq Differential Expression Methods Based on Simulation Studies

| Method | Recommended Sample Size | FDR Control | Power | Stability | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBSeq | n = 3 per group [48] | Good | Good | Good | Very small sample sizes |

| DESeq2 | n ≥ 6 per group [48] | Good | Good | Good | Standard experiments |

| edgeR | n ≥ 6 per group [48] | Moderate | Good | Moderate | Standard experiments |

| limma | n ≥ 6 per group [48] | Good | Moderate | Good | Log-normal distributed data |

| SAMSeq | n ≥ 6 per group [49] | Good | Good | Good | Non-parametric analysis |

Experimental Protocols for Cross-Platform Validation

RNA-seq Experimental Workflow

A standardized RNA-seq protocol begins with RNA extraction using high-quality kits that maintain RNA integrity (RIN > 8.0). Library preparation typically employs stranded protocols to maintain transcript orientation information, with sequencing depth recommendations of 20-40 million reads per sample for standard differential expression studies [47]. The computational workflow involves multiple critical steps: quality control (FastQC), adapter trimming (Trimmomatic, Cutadapt), alignment (STAR, HISAT2), quantification (featureCounts, HTSeq), and normalization (TMM, RLE) [47].

For differential expression analysis, method selection should be guided by sample size and data characteristics. Based on comprehensive evaluations, DESeq2 is recommended for studies with at least 6 replicates per group, while EBSeq shows advantages for very small sample sizes (n = 3) [48]. The voom transformation in combination with limma provides robust performance when applying linear models to RNA-seq data [49] [48]. Normalization is critical, with TMM (trimmed mean of M-values) and RLE (relative log expression) methods demonstrating superior performance compared to simple library size normalization [49].

Figure 1: RNA-seq Experimental Workflow: From sample preparation to differential expression analysis.

qPCR Validation Protocol

The qPCR validation workflow begins with careful experimental design, including selection of appropriate reference genes. The MIQE guidelines recommend using at least two validated reference genes for normalization [40] [45]. Reference gene stability should be assessed using multiple algorithms (geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper) integrated through RefFinder [43] [45]. RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis protocols must be optimized to minimize degradation and ensure efficient reverse transcription.

For assay design, primers should demonstrate 90-110% amplification efficiency with R² > 0.98 in standard curves [45]. Each reaction should include technical triplicates and no-template controls. Data analysis typically uses the ΔΔCt method for relative quantification, with efficiency correction when necessary [45]. The selection of target genes for validation should include both strongly differentially expressed genes and those with moderate fold-changes to properly assess the dynamic range of concordance.

Figure 2: qPCR Validation Workflow: From experimental design to concordance assessment.

Analytical Framework for Concordance Assessment

Statistical Assessment of Platform Agreement

A robust concordance assessment integrates both correlation and fold-change metrics. The analysis should begin with scatter plots of expression values (log-transformed) from both platforms, with calculation of Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients. However, correlation alone is insufficient, as it can be inflated by genes with extreme expression values. Bland-Altman analysis (plotting the difference between measurements against their mean) provides additional insight into systematic biases between platforms [47].

For fold-change comparison, scatter plots of LFC values should demonstrate clustering around the y=x line. The concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) integrates both precision (correlation) and accuracy (deviation from y=x) in a single metric. Pre-defined acceptance criteria should be established, such as >85% of validated genes showing directional consistency and >80% showing LFC ratios (RNA-seq/qPCR) between 0.5-2.0 [46] [47]. Statistical significance should be considered alongside effect size, as small expression changes with low p-values may lack biological relevance.

Interpretation Guidelines for Discrepant Results