RNA-seq vs qPCR: A Strategic Guide for Gene Expression Analysis in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) for gene expression analysis, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

RNA-seq vs qPCR: A Strategic Guide for Gene Expression Analysis in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) for gene expression analysis, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of both technologies, guides method selection based on experimental goals like discovery versus targeted quantification, and addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges. The content also explores how these methods can be synergistically combined, with RNA-seq for hypothesis generation and qPCR for validation, to enhance the reliability and depth of gene expression data in both basic and clinical research settings.

Core Principles: How RNA-seq and qPCR Work from Sample to Data

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) and its counterpart for RNA analysis, reverse transcription qPCR (RT-qPCR), are cornerstone techniques in molecular biology laboratories worldwide. These methods provide a precise and sensitive means to amplify and quantify specific nucleic acid sequences, enabling applications from gene expression analysis to pathogen detection. In the context of modern gene expression research, qPCR often serves as a validation tool for high-throughput technologies like RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). This guide objectively examines the complete qPCR workflow, its strengths, limitations, and how its performance compares to RNA-seq, providing researchers with the data needed to select the appropriate method for their experimental goals.

The qPCR Workflow: A Detailed Breakdown

The qPCR process transforms a sample containing a target nucleic acid into a quantifiable data point. This workflow can be divided into several critical stages, from sample preparation to final analysis.

Reverse Transcription

For gene expression studies, the process begins with RNA. RT-qPCR uses reverse transcription to convert RNA into a more stable complementary DNA (cDNA) template prior to amplification [1] [2].

One-step vs. Two-step RT-qPCR: The reverse transcription and amplification steps can be combined or separated.

- One-step reactions combine reverse transcription and PCR in a single tube and buffer, minimizing pipetting steps and reducing contamination risk, making them suitable for high-throughput applications [1] [2].

- Two-step reactions perform reverse transcription and PCR in separate tubes with individually optimized conditions. This allows a single cDNA synthesis to supply multiple amplification reactions and provides greater flexibility for assay optimization [1] [2].

Priming Strategies: The choice of primer for the reverse transcription reaction influences cDNA yield and coverage.

- Oligo(dT) primers anneal to the poly-A tail of mRNA, promoting the synthesis of full-length, coding-sequence-enriched cDNA.

- Random primers anneal at multiple points along all RNA transcripts (including rRNA and tRNA), which can be useful for genes with low expression or significant secondary structure, or for non-polyadenylated RNAs.

- Sequence-specific primers generate the most specific cDNA pool, targeting only the gene of interest [1].

Reverse Transcriptase Enzyme: Selecting a reverse transcriptase with high thermal stability is ideal, as it allows cDNA synthesis to be performed at higher temperatures, helping to denature RNA secondary structures and produce higher cDNA yields [1].

Amplification and Quantification

The cDNA (or DNA, in the case of qPCR) is then subjected to a series of temperature cycles that amplify the target sequence, with fluorescence used to monitor product accumulation in real time [2].

Detection Chemistry: Two primary types of fluorescent reporters are used.

- DNA-binding dyes (e.g., SYBR Green) intercalate with double-stranded DNA PCR products. They are cost-effective and do not require probe design, but they are not sequence-specific, making validation via melt curve analysis essential [3] [2].

- Labeled probes (e.g., Hydrolysis or Hairpin probes) provide sequence-specific detection. The 5' nuclease assay in hydrolysis probes, for example, cleaves a reporter dye from a quencher dye during amplification, generating a fluorescent signal proportional to the target amount. This allows for multiplexing and increases specificity [2].

The Amplification Curve and Cq Value: The core of qPCR quantification lies in the amplification plot, which tracks fluorescence versus cycle number. The cycle threshold (Cq), also known as quantification cycle, is defined as the intersection between the amplification curve and a threshold line set above the background baseline [3]. The Cq value is inversely correlated with the starting quantity of the target; a lower Cq indicates a higher initial amount of the target molecule.

Data Analysis and Normalization

Accurate interpretation of Cq values is critical for reliable results.

Absolute vs. Relative Quantification: Absolute quantification determines the exact copy number of a target by comparing Cq values to a standard curve of known concentrations. Relative quantification, more common in gene expression studies, compares the expression level of a target gene between samples relative to a reference gene or group of genes [3].

The Importance of Normalization: Normalization controls for technical variation introduced during sample processing. The most common strategy uses reference genes (RGs), such as GAPDH or ACTB, which are presumed to have stable expression across experimental conditions [4]. Research shows that using multiple, validated RGs is crucial, as the expression of classic "housekeeping" genes can vary under different pathological or physiological conditions [4]. An alternative method, the global mean (GM), uses the average expression of a large set of genes and can be a superior normalizer when profiling dozens to hundreds of genes [4].

qPCR Analysis Methods: The popular 2−ΔΔCT method for calculating fold changes assumes perfect amplification efficiency for both target and reference genes. However, multivariable linear models (MLMs) are now shown to outperform the 2−ΔΔCT method, as they provide correct significance estimates even when amplification efficiency is less than ideal or differs between genes [5].

qPCR vs. RNA-seq: An Objective Performance Comparison

While qPCR is a targeted method for quantifying specific sequences, RNA-seq provides a comprehensive, hypothesis-free view of the entire transcriptome. The table below summarizes their comparative performance based on published data.

Table 1: Key Performance Indicators - qPCR vs. RNA-seq

| Feature | qPCR | RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Low to medium; optimal for ≤ 20 targets [6] | High; can profile >1000 targets in a single assay [6] |

| Dynamic Range | Wide, but can be limited by sample quality and inhibitors | Very wide, capable of quantifying very low and highly expressed transcripts [6] |

| Sensitivity | High, capable of detecting rare transcripts [6] | High; can detect gene expression changes down to 10% [6] |

| Discovery Power | Limited to known, pre-defined sequences [6] | High; can detect novel transcripts, splice variants, and fusion genes [7] [6] |

| Expression Correlation | Considered the gold standard for validation | High correlation with qPCR (e.g., R² ~0.84-0.93), though a subset of genes shows inconsistent results [8] [7] |

| Cost & Accessibility | Lower instrument cost, accessible to most labs | Higher startup and operational cost, specialized expertise needed |

| Workflow Speed | Faster for a small number of targets | Longer workflow from library prep to data analysis |

Experimental data from benchmark studies reinforce these comparisons. One study comparing RNA-seq workflows using whole-transcriptome RT-qPCR data found high expression correlations (R² up to 0.845) and high fold-change correlations (R² up to 0.934) between the technologies [7]. However, it also identified a small but consistent subset of genes (e.g., those that are smaller, have fewer exons, and are lower expressed) for which the methods provided inconsistent results, indicating a need for careful validation [7]. Another study focusing on the challenging HLA genes reported only a moderate correlation (0.2 ≤ rho ≤ 0.53) between expression estimates from qPCR and RNA-seq, highlighting how technical factors like extreme polymorphism can impact concordance [8].

Essential Reagents and Research Solutions

A successful qPCR experiment relies on a suite of optimized reagents. The following table details key components and their functions.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for the qPCR Workflow

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesizes cDNA from an RNA template. | High thermal stability and processivity are key for efficient transcription of structured RNAs [1] [9]. |

| qPCR Master Mix | Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and buffer optimized for amplification. | Choice depends on detection method (dye- or probe-based). Should have high efficiency and robustness. |

| Detection Chemistry | Fluorescent reporting of amplified product (e.g., DNA-binding dyes, hydrolysis probes). | Dyes are cost-effective; probes offer multiplexing and higher specificity [2]. |

| Nuclease-free Water | Solvent for preparing reagents and dilutions. | Essential for preventing RNA and DNA degradation. |

| Reference Gene Assays | Primers and probes for stably expressed genes used for data normalization. | Must be validated for stability in the specific tissues and experimental conditions under study [4]. |

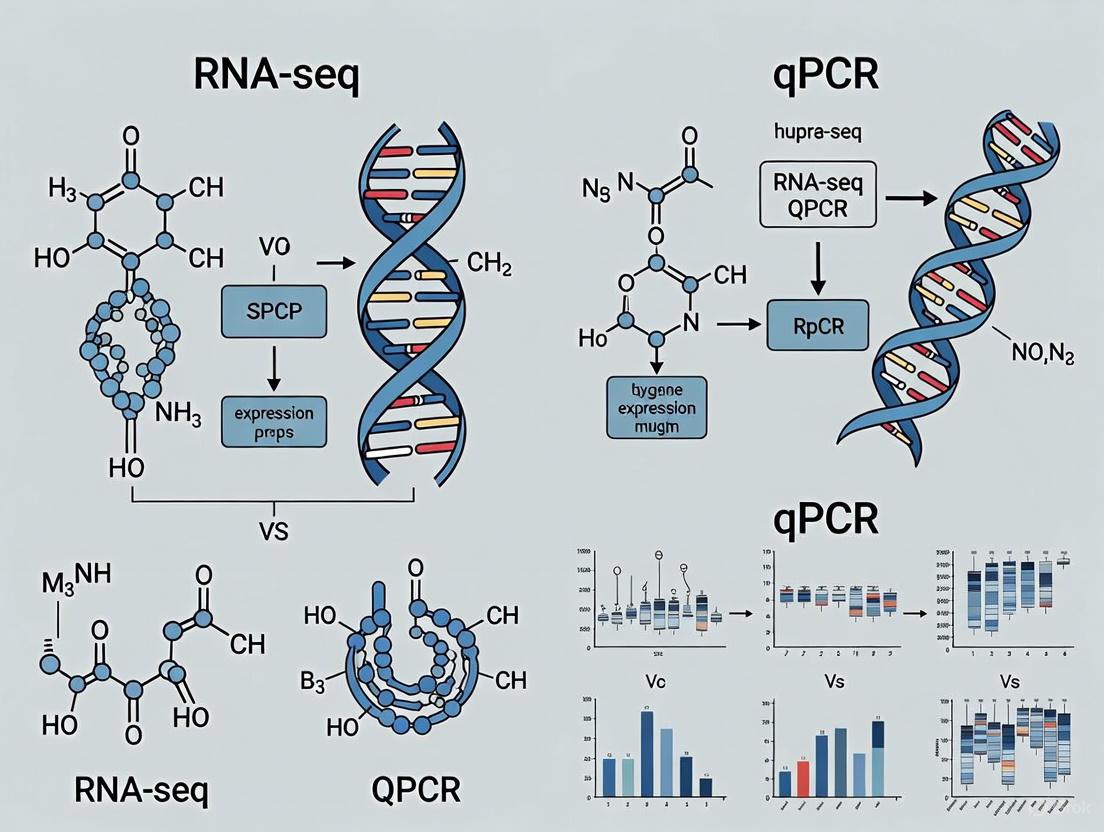

Visualizing the Workflows and Decision Pathway

The following diagrams summarize the core qPCR workflow and the decision process for choosing between qPCR and RNA-seq.

Choosing Between qPCR and RNA-seq

The qPCR workflow, from reverse transcription to Cq quantification, remains a powerful, precise, and accessible method for targeted gene expression analysis. Its role in validating findings from discovery-based platforms like RNA-seq is indispensable. However, the choice between qPCR and RNA-seq is not a matter of which is superior, but which is most appropriate for the research question. For focused, high-precision quantification of a limited number of known targets, qPCR is unmatched in its efficiency and cost-effectiveness. For exploratory transcriptome-wide studies, discovery of novel isoforms, or profiling thousands of genes, RNA-seq is the unequivocal choice. By understanding the capabilities, limitations, and complementary nature of these two techniques, researchers can design more robust gene expression studies and generate more reliable data.

In the field of gene expression analysis, reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) has long been the gold standard for targeted gene expression quantification due to its sensitivity, reproducibility, and accessibility [10]. However, the emergence of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has revolutionized transcriptome studies by providing a comprehensive, hypothesis-free approach that enables researchers to move beyond the constraints of pre-defined targets [6]. While RT-qPCR is limited to detecting known sequences, RNA-seq offers unbiased discovery power to detect novel transcripts, alternatively spliced isoforms, and non-coding RNAs without prior sequence knowledge [6].

The fundamental difference in discovery capability stems from the underlying methodologies: RT-qPCR relies on predetermined primers and probes for specific targets, whereas RNA-seq utilizes a sequencing-by-synthesis approach to capture sequence information from the entire transcriptome [11] [6]. This guide provides a detailed examination of the RNA-seq technical pipeline—from library preparation through sequencing and alignment—and presents objective performance comparisons with RT-qPCR to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting the appropriate methodology for their gene expression research questions.

RNA-seq Workflow: From Sample to Data

The RNA-seq pipeline transforms RNA samples into analyzable gene expression data through a multi-stage process. The workflow involves converting RNA into a sequenceable library, high-throughput sequencing, and computational alignment of the resulting reads.

Library Preparation: Constructing Sequenceable Fragments

Library preparation begins with RNA isolation and purification to remove ribosomal RNA, which constitutes the majority of total RNA. This can be achieved through poly(A) enrichment (capturing mRNA via poly-A tails) or ribosomal RNA depletion (removing rRNA molecules) [12] [11]. The purified RNA is then fragmented, reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA), and ligated with platform-specific adapters to enable amplification and sequencing [11].

A critical consideration is choosing between stranded versus unstranded protocols. In unstranded library preparation, both cDNA strands are amplified for sequencing, resulting in loss of transcriptional strand orientation information. Stranded protocols preserve this information by incorporating dUTPs during second-strand cDNA synthesis and selectively degrading the newly synthesized strand, allowing researchers to determine whether reads originate from the sense or antisense strand—crucial information for identifying overlapping genes and antisense transcription [11].

Recent advances have enabled miniaturized and automated library preparation methods that significantly reduce reagent usage and processing time. One study demonstrated a 1/10th scale reaction volume for cDNA synthesis and library generation using liquid handlers, achieving substantial cost savings while maintaining library quality and reproducibility [12]. These miniaturized protocols maintain similar gene detection rates and sample clustering patterns compared to full-volume preparations, making RNA-seq more accessible for studies with limited starting material or budget constraints [12].

High-Throughput Sequencing: Cluster Amplification and Sequencing by Synthesis

Once libraries are prepared, molecules undergo cluster amplification on a flow cell coated with immobilized oligonucleotides. Templates are copied from hybridized primers using high-fidelity DNA polymerase, followed by bridge amplification where templates loop over to hybridize to adjacent oligonucleotides, creating dense clonal clusters containing approximately 2,000 molecules each [11].

The actual sequencing occurs through a sequencing-by-synthesis process where a polymerase adds fluorescently tagged dNTPs to the growing DNA strand. Each of the four bases has a unique fluorophore, and after each round, the instrument records which base was added. The fluorophore is then washed away, and the process repeats [11]. Sequencing can be performed as single-end (reading from one end) or paired-end (reading from both ends), with paired-end sequencing providing improved mapping accuracy, especially in repetitive regions [11].

Read Alignment and Quality Control: From Raw Sequences to Expression Data

The sequencing output is stored in FASTQ files, which contain sequence identifiers, nucleotide sequences, and quality scores encoded in Phred values [11]. Before alignment, quality control checks are performed using tools like FastQC to assess per-base sequence quality, sequence duplication levels, adapter contamination, and other potential issues [11].

Read alignment involves mapping sequences to a reference genome or transcriptome using specialized tools. The choice of alignment algorithm and reference annotation significantly impacts results. Studies have shown that more comprehensive annotations like AceView capture a higher percentage of reads (97.1%) compared to RefSeq (85.9%) or GENCODE (92.9%), highlighting the importance of annotation selection [13]. Following alignment, expression quantification assigns reads to genomic features, generating count tables that represent gene expression levels for downstream analysis [11].

Performance Benchmarking: RNA-seq vs. qPCR

Technical Comparison of Methodologies

Table 1: Technical Comparison of RNA-seq and qPCR

| Feature | RNA-seq | qPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | High: Can profile thousands of genes simultaneously [6] | Low to Medium: Best for ≤20 targets [6] |

| Discovery Power | High: Detects novel transcripts, splice variants, and fusion genes [6] | None: Limited to known, pre-defined sequences [6] |

| Dynamic Range | >10âµ without signal saturation [6] | ~10â· but subject to background noise at low end [6] |

| Sensitivity | Can detect expression changes as subtle as 10% [6] | High but limited to abundant transcripts |

| Absolute Quantification | Possible through unique molecular identifiers | Requires standard curves |

| Sample Throughput | High: Multiple samples multiplexed in single run | Medium: Limited by number of reactions |

| Hands-on Time | Moderate to High (library preparation) | Low (reaction setup) |

| Cost per Sample | $50-$500 (decreasing over time) | $2-$10 per reaction |

| Equipment Requirements | High-cost sequencers | Moderate-cost thermocyclers |

Accuracy and Reproducibility Assessment

Large-scale multi-center studies have systematically evaluated RNA-seq performance for gene expression analysis. The Quartet project, encompassing 45 laboratories and generating over 120 billion reads, revealed that RNA-seq demonstrates high reproducibility for absolute gene expression measurements, with Pearson correlation coefficients of 0.876 when compared to TaqMan qPCR datasets [14]. However, the study identified significant inter-laboratory variations when detecting subtle differential expression—particularly challenging when biological differences between sample groups are minimal, as often occurs in clinical samples [14].

The Sequencing Quality Control (SEQC/MAQC-III) project, a comprehensive multi-site cross-platform analysis, demonstrated that RNA-seq provides highly reproducible relative expression measurements across laboratories and platforms when appropriate filters are applied [13]. Both RNA-seq and qPCR exhibited gene-specific biases in absolute measurements, indicating that neither technology provides perfectly accurate absolute quantification without calibration [13]. For junction discovery, RNA-seq demonstrated remarkable capability, with over 80% of unannotated exon-exon junctions validated by qPCR [13].

Break-even Analysis: Economic Considerations

While RNA-seq running costs have decreased markedly since its introduction, making it accessible to more research groups, economic considerations remain important for experimental design [15]. A break-even analysis comparing RT-qPCR and RNA-seq reveals that RNA-seq becomes economically competitive when studying larger gene sets, though the exact break-even point depends on specific laboratory pricing and throughput [15]. For studies focusing on a small number of genes (<20), qPCR remains more cost-effective, while RNA-seq offers superior value for comprehensive transcriptome analysis [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Miniaturized RNA-seq Library Preparation Protocol

Recent methodological advances have focused on reducing RNA-seq costs through miniaturization. The following protocol, adapted from a 2020 study, demonstrates a cost-effective approach for Illumina-compatible libraries [12]:

Poly(A) mRNA Isolation (1/20th scale)

- Input: 100 ng total RNA in 2.5 μL

- Use NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module at 1/20th reaction volume

- Modify manufacturer's protocol: Include two rounds of mRNA elution and rebinding with increased incubation time (10 minutes instead of 5)

- Elute mRNA in 1.5 μL First Strand Synthesis Reaction Buffer and Random Primer mix

cDNA Synthesis (1/10th scale)

- Fragment RNA by incubating at 94°C for 10 minutes (reduced from 15 minutes)

- Perform first-strand synthesis with extended incubation: 50 minutes at 42°C instead of 15 minutes

- Use NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit at 1/10th reaction volume

Library Generation (1/10th scale)

- Ligate adapters using 500 nL of NEBNext Adaptor diluted to 0.75 μM

- Amplify libraries with 14 PCR cycles

- Purify with a two-part SPRI clean: first with 1.2× PCRClean DX SPRI beads, followed by addition of SPRI buffer equivalent to a 0.9× cut

This miniaturized approach reduces reagent usage by 90% for library preparation steps while maintaining data quality comparable to full-volume reactions [12].

Reference Materials for Quality Control

The Quartet project has developed reference materials specifically designed for assessing performance in detecting subtle differential expression [14]. These include:

- Four RNA samples from a Chinese quartet family (parents and monozygotic twin daughters)

- Two samples constructed by mixing two of the quartet samples at defined ratios (3:1 and 1:3)

- ERCC spike-in controls with known concentrations

These materials enable ratio-based quality assessment and are particularly valuable for laboratories implementing RNA-seq for clinical applications where detecting subtle expression changes is critical [14].

Decision Framework and Best Practices

Technology Selection Guide

The choice between RNA-seq and qPCR depends on multiple factors, including research objectives, sample number, target gene count, and budget. The following decision pathway provides guidance for selecting the appropriate methodology:

Figure 1: Technology selection decision pathway for gene expression analysis.

Best Practices for RNA-seq Experimental Design

Based on multi-center benchmarking studies, the following practices enhance RNA-seq data quality and reproducibility [14]:

- Replicate Strategy: Include sufficient biological replicates (minimum 3-5 per condition) to ensure statistical power, especially for detecting subtle expression differences

- RNA Quality: Use high-quality RNA (RIN > 8) to minimize technical variation

- Spike-in Controls: Incorporate ERCC or other synthetic RNA controls to monitor technical performance

- Stranded Protocol: Select stranded library preparation to preserve strand orientation information

- Sequencing Depth: Target 20-50 million reads per sample for standard differential expression studies

- Batch Design: Balance experimental groups across sequencing batches to avoid confounding technical and biological effects

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for RNA-seq Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality total RNA | QIAzol Lysis Reagent, TRIzol [10] |

| Poly(A) Enrichment | mRNA selection via poly-A tail capture | NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module [12] |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Removal of ribosomal RNA | NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit [12] |

| Library Prep Kits | Construction of sequenceable libraries | NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit [12] |

| mRNA Seq Kits | Integrated solutions for coding transcriptome | Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep [6] |

| Targeted RNA Panels | Focused analysis of gene sets | RNA Prep with Enrichment + targeted panels [6] |

| Quality Control | Assessment of RNA and library quality | Fragment Analyzer, Agilent Bioanalyzer [12] |

| Quantification Kits | Fluorometric measurement of library concentration | SYBR Green I nucleic acid gel stain [12] |

| Buffer Systems | Maintaining reaction conditions | First Strand Synthesis Reaction Buffer [12] |

The RNA-seq pipeline represents a powerful methodology for comprehensive transcriptome analysis, offering distinct advantages in discovery power and throughput compared to qPCR. While qPCR remains the optimal choice for targeted gene expression analysis of limited gene sets, RNA-seq provides unparalleled capability for novel transcript discovery, isoform characterization, and systems-level biology.

Recent advances in miniaturized protocols [12], standardized reference materials [14], and bioinformatics pipelines have enhanced the reproducibility and accessibility of RNA-seq, positioning it as an indispensable tool for modern genomics research. The development of best practices through large-scale benchmarking studies enables researchers to design robust experiments capable of detecting biologically meaningful expression changes, even in challenging clinical scenarios with subtle differential expression.

As sequencing costs continue to decrease and methodologies improve, RNA-seq is poised to become increasingly integral to both basic research and clinical applications, complementing rather than completely replacing qPCR in the gene expression analysis toolkit.

In the field of gene expression research, the transition from traditional methods like quantitative PCR (qPCR) to advanced sequencing technologies has revolutionized how scientists define and study the transcriptome. While qPCR remains the gold standard for quantifying the expression of a limited number of pre-defined genes, next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies offer two powerful, comprehensive approaches: whole-transcriptome sequencing and targeted RNA sequencing [16] [6]. Whole-transcriptome sequencing (often used interchangeably with RNA-Seq) provides a hypothesis-free, global view of all RNA molecules in a sample. In contrast, targeted RNA sequencing uses probes to enrich for a specific subset of transcripts of interest prior to sequencing [16]. This guide objectively compares the performance, applications, and experimental considerations of these two pivotal methods for transcriptome analysis.

Core Technology Comparison

The fundamental difference between these methods lies in their scope and approach to capturing the transcriptome. The table below summarizes their core characteristics and performance metrics.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Whole-Transcriptome and Targeted RNA Sequencing

| Feature | Whole-Transcriptome Sequencing | Targeted RNA Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Unbiased discovery of novel and known transcripts [6] | Focused analysis of a pre-defined set of genes [16] |

| Transcript Coverage | Comprehensive; detects mRNA, miRNA, tRNA, non-coding RNA, and novel isoforms [16] [6] | Limited to a targeted panel (e.g., hundreds to thousands of genes) [16] [6] |

| Key Strength | Novel transcript discovery, alternative splicing analysis, fusion gene detection [6] [17] | High sensitivity for low-abundance transcripts, cost-effective for focused studies [18] |

| Optimal Use Cases | Exploratory research, biomarker discovery, studying splice variants [16] [17] | Validation studies, screening known gene panels, clinical diagnostics [16] [18] |

| Compatibility with Low-Quality RNA | Lower; typically requires high-quality RNA input [17] | Higher; some depletion-based WTS methods can tolerate lower RIN scores [17] |

Performance and Experimental Data

Independent studies have systematically evaluated these methods, providing critical data to inform your choice. One key comparison involves their ability to detect differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Research using the classic whole-transcript method (KAPA Stranded mRNA-Seq kit) and a 3'-targeted method (Lexogen QuantSeq kit) on mouse liver samples found that the whole-transcript method consistently detected a greater number of differentially expressed genes across varying sequencing depths [19].

Another critical performance aspect is transcript length bias. In whole-transcriptome methods, longer transcripts generate more sequencing fragments, leading to higher read counts independent of their true abundance. Targeted methods, particularly those with a 3' bias, are largely insensitive to transcript length, assigning reads more proportionally to the actual number of transcripts [19]. This makes targeted approaches particularly advantageous for accurately quantifying short transcripts, especially at lower sequencing depths [19].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison Based on Peer-Reviewed Studies

| Performance Metric | Whole-Transcriptome Sequencing | Targeted RNA Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Detection of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) | Detects more DEGs, enriched for longer transcripts [19] | Detects fewer DEGs; more effective for short transcripts [19] |

| Sensitivity for Rare Transcripts/Variants | Moderate; can be improved with very high sequencing depth at greater cost [16] | High; enrichment enables deep coverage of targets, detecting variants with ~1% allele frequency [6] [18] |

| Reproducibility | High and reproducible [19] | High and reproducible [19] |

| Variant Detection Power | Can identify novel somatic mutations [18] | High accuracy for known, expressed variants; can miss low-expressed or non-transcribed variants [18] |

| Correlation with qPCR (Gold Standard) | Moderate correlation (e.g., rho ~0.2-0.53 for HLA genes) [8] [20] | High concordance with qPCR and other targeted methods like TaqMan assays [16] |

Method Selection and Experimental Protocols

Choosing the Right Method

The choice between these methods is not a matter of superiority, but of aligning the technology with the research goals [16]. The following diagram outlines the key decision-making workflow.

Complementary Roles in a qPCR Workflow

Rather than being competing technologies, qPCR and NGS are often complementary [16]. A common integrated workflow uses whole-transcriptome sequencing for initial, unbiased discovery to identify candidate genes of interest. Subsequently, targeted RNA-seq or qPCR is used for validation and follow-up studies on a larger number of samples [16] [21]. Furthermore, RNA-seq data can be leveraged to identify stably expressed genes for use as superior reference genes in qPCR experiments, moving beyond traditional housekeeping genes which can show high expression variance [21].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and kits used in the featured experiments, providing a practical resource for experimental planning.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Transcriptome Profiling

| Reagent / Kit Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| KAPA Stranded mRNA-Seq Kit [19] | Whole-Transcriptome | Prepares sequencing libraries from fragmented mRNA | Provides uniform coverage across transcripts; ideal for detecting DEGs and novel isoforms |

| Lexogen QuantSeq 3' mRNA-Seq Kit [19] | Targeted (3'-Sequencing) | Prepares libraries from the 3' end of transcripts | Minimizes transcript length bias; cost-effective for high-sample-number studies |

| Ion AmpliSeq Transcriptome Kit [16] | Targeted (Whole Transcriptome) | Enables targeted sequencing of >20,000 human RefSeq genes | Focuses on known transcriptome; requires low RNA input |

| TaqMan Gene Expression Assays [16] | qPCR | Provides primers and probe for quantifying specific mRNAs | Gold standard for target validation; used downstream of NGS for confirmation |

| Agilent Clear-seq & Roche Comprehensive Cancer Panels [18] | Targeted (DNA & RNA) | Captures and sequences genes relevant to cancer | Designed for detecting expressed mutations in precision oncology |

Whole-transcriptome and targeted RNA sequencing are both powerful techniques that serve distinct purposes in the modern molecular biology toolkit. Whole-transcriptome sequencing is the undisputed choice for exploratory, discovery-driven research where the goal is to characterize the entire RNA landscape without prior assumptions. Targeted RNA sequencing offers a cost-effective, sensitive, and focused alternative for projects centered on specific gene panels, clinical applications, or large-scale validation studies. The most robust research strategies often leverage the strengths of both—using whole-transcriptome sequencing for initial discovery and targeted approaches, including qPCR, for validation and precise quantification—to generate comprehensive and reliable transcriptomic data.

In the context of comparing RNA-seq and qPCR for gene expression research, understanding the distinction between the relative quantification of Quantitative PCR (qPCR) and the absolute quantification of Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) is fundamental. While RNA-seq provides a broad, discovery-oriented view of the transcriptome, both qPCR and ddPCR offer targeted validation with high sensitivity. However, their core outputs—relative versus absolute quantification—fundamentally shape their application, data interpretation, and reliability. This guide objectively compares the performance of these two established methods, supported by experimental data, to help researchers and drug development professionals select the optimal tool for their specific gene expression analysis needs.

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Workflows

The divergence in the outputs of qPCR and ddPCR originates from their core quantification methodologies. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) relies on relative quantification, determining the amount of a target nucleic acid relative to a reference gene or a standard curve. It monitors the amplification of DNA in real-time, with the cycle threshold (Cq) indicating the starting quantity. The common ΔΔCq method calculates fold-changes in gene expression between experimental and control groups [22] [23]. In contrast, Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) provides absolute quantification by partitioning a PCR reaction into thousands of nanoliter-sized droplets. Following end-point amplification, the fraction of positive droplets is counted, and Poisson statistics are applied to calculate the absolute copy number concentration of the target molecule in units of copies per microliter, without the need for a standard curve [22] [24].

The diagram below illustrates the key procedural and analytical differences between the two workflows.

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data and Applications

Direct comparative studies reveal how the fundamental differences in principle translate into performance variations across key metrics, influencing the ideal application for each technology.

Side-by-Side Performance Comparison

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of qPCR and ddPCR based on objective comparisons.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of qPCR and ddPCR

| Feature | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Quantification Method | Relative (ΔΔCq); requires standard curve [22] [25] | Absolute (copies/µL); no standard curve [22] [25] |

| Dynamic Range | Wide (6-7 orders of magnitude) [23] [25] | Narrower (~4 orders of magnitude) [23] [25] |

| Precision & Sensitivity | Good for mid/high abundance targets; diminishes for low-abundance targets and subtle fold-changes (<2x) [22] | Higher precision; reliable detection of low-abundance targets and subtle fold-changes (<2x) [22] [25] |

| Multiplexing | Requires validation for matched amplification efficiency [22] | Simplified multiplexing without optimization for efficiency [22] |

| Impact of Inhibitors | Susceptible; can reduce amplification efficiency [23] [25] | Resilient; partitioning minimizes impact [22] [25] |

| Throughput & Cost | High throughput (96-/384-well plates), lower cost per reaction [23] [25] | Lower throughput, higher instrument and reagent cost [23] [25] |

Experimental Data from a Direct Gene Expression Study

A comparative study using identical cDNA samples and primer sets for qPCR (CFX Opus System) and ddPCR (QX600 System) highlights their performance in a real-world scenario, particularly for genes with varying expression levels [22].

Table 2: Measured Fold Change in Gene Expression (qPCR vs. ddPCR) This table shows the measured fold change for a low-abundance target (BCL2) and a more abundant target (GADD45A) following cisplatin treatment. "ns" indicates the result was not statistically significant.

| Target Gene | Singleplex Fold Change (qPCR) | Singleplex Fold Change (ddPCR) | Multiplex Fold Change (qPCR) | Multiplex Fold Change (ddPCR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCL2 (Low Abundance) | ns | 2.07 | ns | 2.03 |

| GADD45A | 2.36 | 2.30 | 2.66 | 2.60 |

Key Insight from Data: While both technologies detected the low-abundance target BCL2, qPCR failed to identify a statistically significant fold change, whereas ddPCR resolved a significant ~2-fold difference with tighter error bars [22]. This demonstrates ddPCR's superior precision and sensitivity for quantifying subtle expression changes in challenging targets.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and high-quality data, following standardized protocols for both technologies is crucial. The methodologies below are adapted from the comparative studies cited.

Protocol: Gene Expression Analysis via qPCR

This protocol is designed for relative quantification using the ΔΔCq method on a system like the Bio-Rad CFX Opus [22].

- Step 1: cDNA Synthesis. Convert purified RNA to cDNA using a reverse transcriptase kit. Use a consistent amount of total RNA (e.g., 1 µg) across all samples.

- Step 2: Reaction Setup. Prepare a qPCR master mix containing:

- cDNA template

- Forward and reverse primers (e.g., PrimePCR Assays)

- Fluorescent probe-based supermix (e.g., TaqMan)

- Nuclease-free water

- Step 3: Real-Time PCR Amplification. Load the reaction mix into a 96- or 384-well plate and run on the qPCR instrument with a standard thermal cycling protocol (e.g., 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 30 sec).

- Step 4: Data Analysis. Use instrument software (e.g., CFX Maestro) to determine Cq values. Normalize target gene Cqs to reference genes (e.g., ACTB, PGK1) using the ΔΔCq method to calculate relative fold-change expression [22].

Protocol: Gene Expression Analysis via ddPCR

This protocol is designed for absolute quantification on a system like the Bio-Rad QX600 [22].

- Step 1: cDNA Synthesis. Identical to the qPCR protocol.

- Step 2: Reaction Setup. Prepare a ddPCR master mix containing:

- cDNA template

- Forward and reverse primers

- Fluorescent probe-based ddPCR supermix

- Nuclease-free water

- Step 3: Droplet Generation. Transfer the reaction mix to a DG8 cartridge for the QX600 system. Using a droplet generator, the sample is partitioned into ~20,000 nanoliter-sized oil-emulsion droplets.

- Step 4: PCR Amplification. Transfer the droplets to a 96-well PCR plate and perform end-point PCR on a thermal cycler (e.g., 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec and 60°C for 60 sec, followed by a 98°C hold for 10 min).

- Step 5: Droplet Reading and Analysis. Place the plate in a droplet reader, which flows droplets one-by-one past a two-color optical detection system. The software (e.g., QX Manager) counts the positive and negative droplets for each target and uses Poisson statistics to calculate the absolute concentration (copies/μL) [22].

Technology Selection Guide

Choosing between qPCR and ddPCR depends on the specific requirements of the experiment. The following decision pathway aids in selecting the appropriate technology.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of qPCR and ddPCR assays relies on a set of core reagents and tools. The following table details key materials and their functions.

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for qPCR and ddPCR Workflows

| Item | Function | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-optimized Assays | Primer/probe sets for specific gene targets that are validated for use across platforms. | Bio-Rad's PrimePCR Assays allow seamless transition between qPCR and ddPCR without re-optimization [22]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase Kits | Converts RNA to cDNA for gene expression studies. | A critical first step for both RT-qPCR and RT-ddPCR workflows. |

| Probe-based Supermix | PCR master mix optimized for specific chemistry (TaqMan) and platform. | Ensures high amplification efficiency and robust fluorescence signal [22]. |

| Reference Genes | Genes used for normalization in qPCR to control for sample input and variability. | Selection is crucial; stability must be validated for specific experimental conditions (e.g., ACTB, PGK1) [22] [26]. |

| Droplet Generation Oil | Creates a stable water-in-oil emulsion for partitioning in ddPCR. | A proprietary consumable essential for the ddPCR workflow [22]. |

| RNA-seq Databases | Publicly available datasets for in-silico mining of stable reference genes. | Tools like TomExpress can be used to identify optimal gene combinations for qPCR normalization [26]. |

In gene expression research, quantitative PCR (qPCR) and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) are foundational technologies, each with distinct inherent biases that can significantly impact data interpretation. qPCR is influenced primarily by amplification efficiency, a critical parameter affecting quantitative accuracy [27]. Meanwhile, RNA-seq data is confounded by GC-content bias, where the guanine-cytosine composition of sequences influences read count abundance independently of true expression levels [28] [29]. Understanding these biases is not merely a technical exercise but a prerequisite for producing biologically valid conclusions. This guide objectively compares the performance of these two technologies by detailing the nature, impact, and correction methods for their principal biases, supported by experimental data and protocols.

PCR Amplification Efficiency in qPCR

Definition and Ideal Performance

PCR amplification efficiency defines the proportion of template DNA molecules that are duplicated in each cycle of the PCR reaction [27]. The theoretical maximum, 100% efficiency (often represented as an efficiency of 2.0 or 100%), corresponds to a perfect doubling of every target molecule every cycle [30] [27]. This ideal performance is predicated on optimal reaction conditions, including flawless primer design and the absence of inhibitors. The cycle threshold (Ct) value obtained from a qPCR reaction exhibits an inverse exponential relationship with the original template quantity, making the assumed efficiency fundamental to accurate quantification [27].

Causes and Impact of Altered Efficiency

Deviations from 100% efficiency are common and problematic. Efficiencies below 90% are typically caused by suboptimal primer design, formation of secondary structures (e.g., primer-dimers, hairpins), or non-ideal reagent concentrations [30]. Perhaps counterintuitively, efficiencies exceeding 100% are also possible and are frequently indicative of the presence of polymerase inhibitors in the reaction [30]. These inhibitors, which can include carryover contaminants from nucleic acid isolation like ethanol, phenol, or heparin, are more concentrated in less diluted samples. This concentration-dependent effect flattens the standard curve slope, leading to a calculated efficiency of over 100% [30].

The quantitative impact of non-ideal efficiency is profound. For a Ct value of 20, an assay with 80% efficiency will calculate an 8.2-fold lower quantity compared to an assay with 100% efficiency [27]. This error is magnified in the popular ΔΔCt method for relative quantification. If this method is used when the target and reference genes have different efficiencies, a significant miscalculation occurs; for example, a PCR efficiency of 0.9 (90%) at a threshold cycle of 25 can result in a 261% error, meaning the calculated expression level is 3.6-fold less than the actual value [31].

Assessing Amplification Efficiency

The standard method for assessing efficiency involves generating a standard curve using a serial dilution of a template [27] [31]. The Ct values are plotted against the logarithm of the starting concentration, and the slope of the resulting line is used to calculate efficiency (E) using the formula: E = 10^(-1/slope) - 1 [31]. A slope of -3.32 corresponds to the ideal 100% efficiency [27].

However, this method is prone to error from pipetting inaccuracies, inhibitor contamination, and improper dilution series preparation, which can lead to misleading efficiency values, including those over 100% [27]. A robust alternative is the visual assessment of amplification plots. When the fluorescence is plotted on a logarithmic (log) scale, the geometric phases of different reactions should appear as parallel lines. Non-parallel slopes are a direct visual indicator of differing amplification efficiencies, a method that is not affected by pipetting errors [27].

Experimental Protocol for Determining qPCR Efficiency

This protocol outlines the creation of a standard curve to determine the amplification efficiency of a qPCR assay [31].

- Template Dilution: Prepare a 5-point or 10-fold serial dilution series of a known template. The template can be a plasmid containing the target sequence, genomic DNA, or a cDNA sample with high expression of the target gene. The dilution series should span a concentration range of at least 3 to 4 orders of magnitude (e.g., 100 ng/µL, 10 ng/µL, 1 ng/µL, 0.1 ng/µL, 0.01 ng/µL).

- qPCR Run: Amplify each dilution in the series, including a no-template control (NTC), in triplicate using your standard qPCR protocol (e.g., hot start at 95°C for 20 seconds, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 1 second and 60°C for 10 seconds) [32].

- Data Collection: Record the Ct value for each reaction.

- Standard Curve Generation: Plot the average Ct value (Y-axis) against the logarithm of the starting template concentration (X-axis) for each dilution.

- Efficiency Calculation: Perform linear regression on the data points to obtain the slope of the trendline. Calculate the amplification efficiency (E) using the formula: E = 10^(-1/slope) - 1. An efficiency between 90% and 110% is generally considered acceptable [30] [32]. The linear regression correlation coefficient (R²) should also be calculated; a value of ≥0.985 is desirable for a reliable assay [32].

GC-Content Bias in RNA-Seq

Nature of the GC Bias

GC-content bias in RNA-seq refers to the technical artifact where the number of sequencing reads mapping to a gene is influenced by the gene's guanine and cytosine nucleotide composition, rather than solely reflecting its true expression level [28] [29]. This bias exhibits a unimodal pattern, meaning both GC-rich and AT-rich (GC-poor) fragments are under-represented in the final sequencing library [29]. The consequence is that genes with mid-range GC content receive disproportionately high read counts. This bias is sample-specific and lane-specific, meaning it cannot be assumed to cancel out when comparing expression between samples, thus directly confounding differential expression analysis [28].

Evidence strongly implicates PCR amplification during library preparation as a primary cause of this bias [29]. The GC content of the entire DNA fragment, not just the sequenced read portion, has been shown to be the dominant factor influencing final read counts [29]. This bias can introduce large fluctuations in coverage, with differences of over 2-fold observed even in large 100 kb genomic bins [29].

Impact on Gene Expression Quantification

GC-content bias presents a significant challenge for the biological interpretation of RNA-seq data. Because GC content varies throughout the genome and is often correlated with genomic features and functionality, it can be difficult to distinguish technical bias from true biological signal [28]. Failure to account for this effect can mislead differential expression analysis, as observed variability may be attributed to biological conditions when it is, in fact, technically driven [28].

The sample-specific nature of the bias is particularly problematic. As noted by [28], the common initial belief was that for a given gene, the GC-content effect would be constant across samples and thus cancel out in differential expression analysis. However, it is now understood that the effect is lane-specific, meaning the read counts for a given gene are not directly comparable between lanes or samples without proper normalization [28]. This directly compromises the core objective of most RNA-seq studies: accurately identifying differentially expressed genes.

Normalization Strategies for GC Bias

Correction of GC-content bias is a crucial data processing step. Early methods involved binning genes or exons by GC content and calculating enrichment factors or using loess regression to model and correct the bias [28]. More sophisticated within-lane normalization approaches have been developed. These include:

- Conditional Quantile Normalization (CQN): This method incorporates GC-content and gene length effects as smooth functions in a robust regression model, followed between-lane normalization to account for distributional differences [28].

- Polynomial Regression Approaches: Some methods model bin-level counts as a function of GC-content using a default polynomial degree of three to capture the unimodal relationship [29].

- Within-Lane then Between-Lane Normalization: A general effective strategy involves first applying a within-lane procedure to remove the gene-specific GC bias, followed by a between-lane procedure (e.g., based on quantiles) to adjust for technical distribution differences between samples [28].

Experimental and Analytical Workflow for GC-Content Normalization

This protocol describes a generalized workflow for assessing and correcting GC-content bias, adaptable to various software tools.

- Read Alignment and Quantification: Process raw RNA-seq reads through a standard alignment-based (e.g., STAR-HTSeq) or pseudoalignment-based (e.g., Salmon, Kallisto) workflow to obtain gene-level read counts or transcript-level abundances [7].

- Bias Assessment: Calculate the GC content for each gene (or transcript) based on the reference genome sequence. Generate a plot showing normalized read count (or coverage) versus GC content for a single sample. A non-flat, typically unimodal curve indicates a strong GC-content bias [28] [29].

- Apply Normalization: Use a dedicated software tool or package that implements GC-content normalization.

- Tool Example - EDASeq: The EDASeq package in R/Bioconductor provides functions for exploratory data analysis and normalization of RNA-seq data, including within-lane normalization procedures to adjust for GC-content bias [28].

- Method: The procedure involves calculating a GC-content dependent correction factor for each gene within each sample and then adjusting the raw counts accordingly. This is often followed by a between-lane normalization method to equalize count distributions across samples [28].

- Validation: Re-plot the normalized read counts against GC content. A successful correction will show a flattened relationship, where read count is no longer strongly dependent on GC content.

Comparative Performance Data

The table below provides a direct comparison of the key biases associated with qPCR and RNA-seq.

Table 1: Direct Comparison of Key Biases in qPCR and RNA-seq

| Feature | qPCR: Amplification Efficiency Bias | RNA-seq: GC-Content Bias |

|---|---|---|

| Nature of Bias | Kinetic bias in the amplification reaction | Selection and amplification bias during library prep |

| Primary Cause | Primer design, reaction conditions, inhibitors | PCR during library prep; unimodal under-representation of extreme GC fragments [29] |

| Main Impact | Incorrect absolute and relative quantification | Skewed read counts, confounding differential expression analysis [28] |

| Correlation between Techniques | Moderate correlation observed between expression estimates from qPCR and RNA-seq (e.g., 0.2 ≤ rho ≤ 0.53 for HLA genes) [8] | |

| Key Correction Methods | - Optimized primer/probe design- Standard curve efficiency assessment- ΔΔCt with efficiency correction [31] | - Within-lane GC normalization (e.g., CQN)- Combined within- and between-lane normalization [28] |

| Ideal Performance | 100% efficiency for all assays | No dependence between read count and GC content |

Experimental Data from Comparative Studies

Independent benchmarking studies provide quantitative data on how RNA-seq and qPCR results correlate. One study compared five common RNA-seq workflows (Tophat-HTSeq, Tophat-Cufflinks, STAR-HTSeq, Kallisto, Salmon) against whole-transcriptome RT-qPCR data.

Table 2: Correlation between RNA-seq Workflows and qPCR Expression Data

| Workflow | Expression Correlation (Pearson R² with qPCR) | Fold-Change Correlation (Pearson R² with qPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Salmon | 0.845 | 0.929 |

| Kallisto | 0.839 | 0.930 |

| Tophat-Cufflinks | 0.798 | 0.927 |

| Tophat-HTSeq | 0.827 | 0.934 |

| STAR-HTSeq | 0.821 | 0.933 |

Data adapted from [7].

The data shows high overall concordance, with fold-change correlations being particularly strong (R² > 0.92 for all workflows) [7]. However, a fraction of genes (15-19%) showed non-concordant differential expression calls between RNA-seq and qPCR, with alignment-based algorithms (e.g., Tophat-HTSeq) having a slightly lower non-concordant fraction [7]. These discrepant genes tended to be lower expressed, smaller, and have fewer exons, highlighting that biases can affect specific gene sets more severely [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Bias Management

| Item | Function in qPCR / RNA-seq | Role in Managing Bias |

|---|---|---|

| TaqMan Assays / Optimized Primers | Target-specific amplification in qPCR | Ensures high, consistent amplification efficiency (~100%), minimizing quantification error [27]. |

| qPCR Master Mix (Inhibitor-Tolerant) | Chemical environment for qPCR reaction | Reduces impact of sample carry-over inhibitors, preventing artificial inflation of efficiency values [30]. |

| Nucleic Acid Purification Kits | Isolation of DNA/RNA from samples | Removes contaminants that act as PCR inhibitors; purity (A260/280 ratios of ~1.8 for DNA, ~2.0 for RNA) is critical [30]. |

| Strand-Specific RNA Library Prep Kits | Conversion of RNA to sequencer-ready library | Specific protocols can influence the profile and magnitude of GC bias. Kits designed to reduce bias are available. |

| Normalization Software (e.g., EDASeq, CQN) | Bioinformatic correction of sequencing data | Implements algorithms for GC-content and length normalization within and between samples [28]. |

| Standard Reference Materials (e.g., ERCC RNA Spike-Ins) | Exogenous controls added to samples | Provides a known standard to monitor and correct for technical biases, including those related to GC content, in both qPCR and RNA-seq. |

| 5-(4-Hydroxybutyl)imidazolidine-2,4-dione | 5-(4-Hydroxybutyl)imidazolidine-2,4-dione|C7H12N2O3 | 5-(4-Hydroxybutyl)imidazolidine-2,4-dione (CAS 5458-06-0) is a hydantoin derivative for research. This product is For Research Use Only and not for human or veterinary use. |

| 8-Hydroxygenistein | 8-Hydroxygenistein|CAS 13539-27-0|For Research |

Both qPCR and RNA-seq are powerful but imperfect tools for gene expression analysis. The choice between them often involves a trade-off between their respective biases and the goals of the study. qPCR's primary strength lies in its potential for highly precise and sensitive quantification of a limited number of targets, but this is entirely dependent on maintaining near-optimal amplification efficiency. RNA-seq's main advantage is its untargeted, genome-wide scope, but this comes at the cost of navigating complex data biases, most notably the GC-content effect, which requires sophisticated bioinformatic correction.

Awareness and proactive management of these inherent biases are non-negotiable for rigorous science. For qPCR, this means rigorous assay validation and efficiency monitoring. For RNA-seq, it mandates the routine application of appropriate normalization strategies. As the data shows, while the correlation between the two technologies is generally high, systematic discrepancies exist [8] [7]. Therefore, the most robust research findings often leverage the strengths of both methods, using qPCR to validate key results from RNA-seq explorations on a focused gene set.

Choosing Your Weapon: A Strategic Guide to Applications and Workflow Integration

In the field of gene expression research, the choice between quantitative PCR (qPCR) and RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) is not a matter of selecting a superior technology, but rather of applying the right tool for the specific research question. While RNA-Seq provides unparalleled discovery power for transcriptome-wide exploration, qPCR remains the gold standard for targeted hypothesis-testing and validation of specific genetic targets. This guide objectively compares the performance characteristics of both technologies to help researchers make evidence-based decisions for their experimental workflows, particularly when working with known targets or requiring rigorous validation of findings.

The fundamental distinction lies in their operating principles: RNA-Seq is a hypothesis-generating approach capable of detecting both known and novel transcripts without prior sequence knowledge, while qPCR is a hypothesis-testing method that delivers exceptional sensitivity and precision for quantifying predefined targets. Understanding when and why to deploy each technology—and how they can be powerfully combined—is essential for robust experimental design in both basic research and drug development contexts.

Technical Comparison: qPCR vs. RNA-Seq Performance Characteristics

The table below summarizes the key technical characteristics of qPCR and RNA-Seq to inform technology selection:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of qPCR and RNA-Seq

| Characteristic | qPCR | RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Amplification of known sequences with specific primers/probes | Sequencing of all transcripts without requiring prior knowledge |

| Throughput | Low to medium (typically ≤ 20 targets simultaneously) | High (thousands of genes across multiple samples) |

| Sensitivity | Excellent (can detect rare transcripts with low abundance) | Very good, but requires sufficient sequencing depth |

| Dynamic Range | ~6-8 orders of magnitude | >5 orders of magnitude, dependent on sequencing depth |

| Quantification | Relative or absolute (with standards) | Absolute (based on read counts) |

| Discovery Power | None (limited to known targets) | High (detects novel transcripts, splice variants, fusions) |

| Sample Throughput | High for limited targets | Medium to high (scales with multiplexing) |

| Hands-on Time | Low to medium | Medium to high (library preparation) |

| Data Analysis Complexity | Low (straightforward Ct analysis) | High (requires bioinformatics expertise) |

| Cost per Sample | Low for limited targets | Medium to high |

RNA-Seq provides several distinct advantages for discovery-focused research. It can identify novel transcripts, alternatively spliced isoforms, and sequence variations without prior knowledge of the transcriptome. Additionally, certain RNA-Seq methods can detect subtle changes in gene expression (down to 10%) and profile over 1,000 target regions in a single assay. [6]

However, for studies focused on a limited number of predefined targets, qPCR offers significant practical advantages. The familiar workflow and accessible equipment available in most laboratories make it particularly suitable for rapid screening or validation studies. The technology provides excellent sensitivity and a wide dynamic range sufficient for most targeted gene expression applications. [16] [6]

When to Choose qPCR: Specific Applications and Use Cases

Validation of RNA-Seq Findings

qPCR serves as the primary orthogonal validation method for confirming RNA-Seq results, especially when a research story hinges on the differential expression of only a few genes. [33] [34] Dr. Christopher Mason from Weill Cornell Medicine emphasizes this practice: "We use RNA sequencing extensively... However, qPCR is the most sensitive method we use to validate gene fusion events, expression changes, or isoform variations. I still consider qPCR the high bar for validation." [34]

This validation is particularly crucial for genes with low expression levels or small fold-changes, where technical artifacts may occur. While RNA-Seq methods are generally robust, studies indicate that approximately 1.8% of genes show severe non-concordance between RNA-Seq and qPCR results, typically among lower-expressed and shorter genes. [33]

Targeted Analysis of Known Genes and Pathways

When researching well-characterized biological pathways involving a limited number of genes, qPCR provides a cost-effective and efficient solution. For studies involving ≤ 20 target genes, qPCR typically offers shorter turnaround times and lower costs compared to RNA-Seq. [16] [6] The technology is ideally suited for:

- Biomarker validation studies following discovery phases

- Time-course experiments tracking expression of known gene sets

- Pharmacodynamic studies measuring drug response in specific pathways

- Quality control assays in bioprocessing and manufacturing

Clinical and Diagnostic Applications

qPCR remains firmly established in clinical settings due to its robustness, reproducibility, and regulatory acceptance. Key clinical applications include:

- Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) monitoring to track cancer recurrence

- Infectious disease testing for pathogen detection and quantification

- Pharmacogenetics applications guiding therapeutic decisions

For MRD monitoring specifically, qPCR's high sensitivity enables researchers to "track mutations like EGFR in a patient's blood after therapy," allowing clinicians to monitor cancer evolution and guide treatment decisions. [34]

Situations Requiring High-Sensitivity Detection

qPCR excels in applications demanding exceptional sensitivity to detect low-abundance targets, such as:

- Single-cell gene expression analysis

- Rare transcript detection

- Analysis of degraded or limited samples (e.g., FFPE tissue, liquid biopsies)

- Viral load quantification in early infection stages

The technology's ability to detect minute quantities of nucleic acid makes it indispensable for these challenging applications where RNA-Seq might require impractical sequencing depths to achieve similar sensitivity.

Experimental Design and Validation Protocols

Establishing a Validated qPCR Assay

Proper validation of qPCR assays is essential for generating reliable, publication-quality data. The table below outlines key validation parameters and their implementation:

Table 2: Essential qPCR Validation Parameters and Implementation

| Validation Parameter | Description | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusivity | Ability to detect all intended target strains/isolates | Test against 50 well-defined certified strains of target organism |

| Exclusivity/Cross-reactivity | Ability to exclude genetically similar non-targets | Validate against common cross-reactive species |

| Linear Dynamic Range | Range where signal is proportional to template concentration | Use 7-point 10-fold dilution series in triplicate |

| Amplification Efficiency | Rate of PCR amplification per cycle | Should be 90-110% with R² ≥ 0.980 |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Lowest concentration reliably detected | Determine via serial dilution of known standards |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | Lowest concentration reliably quantified | Establish with precision profile experiments |

| Precision | Closeness of repeated measurements | Assess through inter-run and intra-run replication |

Both inclusivity and exclusivity validation should include both in silico and experimental components. The in silico phase involves checking oligonucleotide, probe, and amplicon sequences against genetic databases for similarities and differences. The experimental phase confirms that the assay detects all intended targets while excluding non-targets. [35]

Reference Gene Selection for Reliable Normalization

Appropriate reference gene selection is critical for accurate qPCR data interpretation. Traditional housekeeping genes (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB) often show unacceptable variability across different biological conditions. [34] [37] A systematic approach to reference gene selection includes:

- Using RNA-Seq data to identify stably expressed genes in specific experimental conditions

- Employing computational tools like GSV (Gene Selector for Validation) that filter candidates based on expression stability and level

- Validating multiple reference genes across experimental conditions

- Avoiding genes with exceptionally low or high expression that may fall outside the assay's linear range

Research demonstrates that traditional reference genes may be less stable than specifically selected candidates in many experimental systems. For example, in Aedes aegypti studies, genes such as eiF1A and eiF3j showed superior stability compared to traditionally used reference genes. [37]

Sample Quality Assessment and Workflow Integration

Robust qPCR validation requires careful attention to pre-analytical factors:

- RNA quality assessment using appropriate metrics (RIN, DV200)

- cDNA synthesis protocol standardization with minimal batch-to-batch variation

- Inhibition testing using spike-in controls

- Implementation of the MIQE guidelines (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) to ensure experimental rigor [35] [36]

For clinical research applications, additional validation according to the CardioRNA consortium consensus guidelines is recommended to bridge the gap between research-use-only and in vitro diagnostic applications. [36]

Integrated Workflows: Combining RNA-Seq and qPCR

The most powerful gene expression studies strategically combine both RNA-Seq and qPCR technologies. The complementary relationship between these methods can be visualized in the following workflow:

Diagram 1: Integrated RNA-Seq and qPCR Workflow

This integrated approach leverages the respective strengths of each technology:

- RNA-Seq generates comprehensive hypotheses about transcriptome-wide changes

- qPCR provides rigorous validation of key findings in expanded sample sets

- The validated targets can then be deployed in focused applications including clinical assays

In practice, qPCR can be applied both upstream and downstream of NGS workflows. Upstream, it can check cDNA integrity prior to RNA-Seq. Downstream, it verifies results and enables focused studies on targets discovered during NGS screening. [16] This complementary relationship ensures both discovery power and validation rigor in comprehensive gene expression studies.

Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR Experiments

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Their Functions in qPCR

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in qPCR Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Probe Chemistries | Hydrolysis (TaqMan) probes, Molecular Beacons, Dual Hybridization Probes, Eclipse Probes | Target-specific detection with fluorescent signal generation |

| Reference Gene Assays | TaqMan Gene Expression Assays, Custom designed assays | Normalization of sample input and processing variations |

| RNA Quality Controls | RNA Integrity Number (RIN), DV200 metrics | Assessment of sample quality and suitability for analysis |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit | Conversion of RNA to cDNA with high efficiency and reproducibility |

| qPCR Master Mixes | TaqMan Universal Master Mix, SYBR Green Master Mix | Provision of enzymes, nucleotides, and buffers for amplification |

| Pre-spotted Assay Plates | TaqMan Array Cards, OpenArray Plates | High-throughput formatted assays for multiple targets |

| Automation Solutions | Liquid handling systems, Automated nucleic acid extractors | Standardization and increased throughput of sample processing |

Different probe chemistries offer distinct advantages for specific applications. Hydrolysis (TaqMan) probes dominate the market (approximately 50%) due to their simplicity, high sensitivity, and widespread availability. Molecular beacons (approximately 25% market share) offer improved specificity through their hairpin structure that only fluoresces upon hybridization to the target sequence. Dual hybridization probes (approximately 10%) provide enhanced specificity by requiring hybridization to two different target sites. [38]

For clinical research applications, selection of properly validated assays is essential. The field is moving toward standardized "Clinical Research (CR) assays" that fill the gap between research-use-only and fully regulated in vitro diagnostic products, providing greater confidence in biomarker study results. [36]

qPCR remains an indispensable technology for hypothesis-testing approaches focused on known targets and validation of high-throughput screening results. Its exceptional sensitivity, precision, and practical efficiency make it particularly valuable for:

- Orthogonal validation of RNA-Seq findings

- Targeted analysis of predefined gene sets in pathway-focused studies

- Clinical applications requiring robust, reproducible quantification

- Situations demanding high sensitivity for low-abundance targets

The most effective gene expression research strategies recognize that qPCR and RNA-Seq are complementary technologies rather than competing alternatives. By leveraging the discovery power of RNA-Seq for hypothesis generation and the precision of qPCR for hypothesis testing, researchers can build robust, reproducible experimental workflows that advance both basic scientific knowledge and clinical applications.

As Dr. Christopher Mason summarizes, "We use RNA sequencing extensively... However, qPCR is the most sensitive method we use to validate gene fusion events, expression changes, or isoform variations. I still consider qPCR the high bar for validation." [34] This expert perspective underscores the enduring value of qPCR in an era dominated by high-throughput sequencing technologies.

In the context of gene expression research, the choice between quantitative PCR (qPCR) and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) is fundamental and dictated by the research objective. While qPCR is the established gold standard for targeted, hypothesis-driven validation of a predefined set of genes, RNA-seq is the premier tool for unbiased, genome-wide, hypothesis-generating discovery [16]. This guide objectively compares their performance for identifying novel transcripts and isoforms, providing the experimental data and frameworks necessary to inform your experimental design.

Section 1: Performance Comparison for Discovery

The core strength of RNA-seq lies in its ability to survey the entire transcriptome without prior knowledge of its sequence, offering a dynamic range that spans over five orders of magnitude [39].

Table 1: Core Technology Comparison for Discovery Applications

| Feature | RNA-seq | qPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Unbiased discovery, novel isoform identification [40] [41] | Targeted validation and quantification of known sequences [16] |

| Throughput | Genome-wide; all transcripts in a single run [39] | Low-throughput; typically 10s to 100s of targets [16] |

| Dependence on Genome Sequence | Not required for all methods (e.g., de novo assembly) [39] | Required for assay design |

| Ability to Distinguish Isoforms | High; can identify alternative splicing, start/end sites, and novel isoforms [39] [40] | Limited; requires bespoke, isoform-specific assay design [16] |

| Novel Transcript Discovery | Excellent [39] [42] | Not possible |

Quantitative Correlation with qPCR

While RNA-seq is a powerful discovery tool, its quantification accuracy is often validated against qPCR. Benchmarking studies using whole-transcriptome qPCR data show high concordance but also reveal important technical discrepancies.

Table 2: Benchmarking RNA-seq Workflows Against qPCR Gold Standard A study compared gene expression fold changes between two reference samples (MAQCA and MAQCB) using different RNA-seq workflows versus qPCR data for 18,080 protein-coding genes [7].

| RNA-seq Analysis Workflow | Fold Change Correlation with qPCR (R²) | Non-Concordant Genes |

|---|---|---|

| Tophat-HTSeq | 0.934 | 15.1% |

| STAR-HTSeq | 0.933 | Not Specified |

| Tophat-Cufflinks | 0.927 | 16.1% |

| Kallisto | 0.930 | 17.8% |

| Salmon | 0.929 | 19.4% |

The table shows all methods have high overall fold change correlation with qPCR. However, a portion of genes (non-concordant) show inconsistent results between RNA-seq and qPCR. These genes are typically smaller, have fewer exons, and are lower expressed, indicating a class of genes where careful validation is warranted [7]. A separate study focusing on the highly polymorphic HLA genes found only a moderate correlation (0.2 ≤ rho ≤ 0.53) between qPCR and RNA-seq expression estimates, highlighting challenges with specific gene families [8].

Section 2: The Superiority of Long-Read RNA-seq for Isoform Resolution

A critical limitation of standard short-read RNA-seq is its inability to sequence entire transcripts from end to end. Instead, it fragments RNA into short pieces (100-300 bp) that must be computationally reassembled, which often fails to accurately reconstruct complex or novel isoforms [41].

Long-read RNA-seq technologies, such as Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) Iso-Seq and Oxford Nanopore, directly sequence full-length cDNA molecules, producing reads that can span 10 kb or more, effectively capturing complete isoform structures without assembly [40] [42].

Experimental Evidence: Long vs. Short Reads

Application in Muscle Research: A study of large, repetitive structural genes in muscle (e.g., Titin (106 kb), Nebulin (22 kb)) demonstrated the power of long-read sequencing [43].

- Short-read RNA-seq struggled with ambiguous mapping across repetitive regions, leading to many likely false-positive novel splice junctions.

- Long-read RNA-seq (PacBio) unambiguously resolved the full splicing patterns and identified three novel exons in the Nebulin gene, which were confirmed by endpoint PCR and Sanger sequencing [43].

- The study also developed a novel exon phasing approach to enable accurate quantification of these very long transcripts from long-read data [43].

Diagram 1: Short-read RNA-seq workflow for isoform detection.

Diagram 2: Long-read RNA-seq workflow for isoform detection.

Section 3: Experimental Design and Protocols

Choosing and correctly implementing an RNA-seq workflow is paramount for successful discovery.

Choosing a Library Preparation Method

The choice of library prep method dictates the type of information you can obtain [44].

Table 3: Selecting an RNA-seq Library Preparation Method

| Method | Best For | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3’ mRNA-Seq (e.g., Lexogen) | Simple, high-throughput gene expression profiling [44] | Cost-effective; high multiplexing; low computational needs [44] | Cannot assess alternative splicing or discover novel isoforms [44] |

| Whole-Transcriptome (with rRNA depletion) | Discovering all RNA types (mRNA, non-coding RNA) [44] | Unbiased view of the transcriptome; no poly-A requirement [44] | More complex data analysis |

| Long-Read RNA-seq (e.g., PacBio Iso-Seq) | Comprehensive isoform discovery and characterization [40] | End-to-end transcript sequencing; no assembly needed; reveals complex splicing [40] [42] | Higher cost per sample; lower throughput; specialized analysis |

Key Experimental Parameters

- Replicates: A minimum of three biological replicates per condition is standard, though more are needed for higher statistical power or when biological variability is high [45].

- Sequencing Depth: For standard differential expression analysis, 20–30 million reads per sample is often sufficient. Discovery-focused projects, especially those investigating low-abundant transcripts, may require greater depth [45].

Section 4: A Workflow for Discovery and Validation

The most robust research strategy uses RNA-seq and qPCR together, not in opposition [16].

Diagram 3: Integrated workflow for isoform discovery and validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Tools

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq Discovery

| Item | Function | Example Products/Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Full-Length cDNA Synthesis Kit | Generates high-quality, full-length cDNA templates for long-read sequencing. | PacBio Iso-Seq Express 2.0 Kit [40] |

| Long-Read Sequencing Platform | Sequences entire cDNA molecules to reveal complete isoform structures. | PacBio Revio & Sequel II Systems [40] |

| RNA-seq Alignment & Quantification Software | Maps sequencing reads to a reference and quantifies transcript abundance. | STAR, HISAT2, Kallisto, Salmon [45] [7] |

| Isoform Detection & Analysis Workflow | Identifies and characterizes known and novel isoforms from long-read data. | PacBio SMRT Link Iso-Seq workflow [40] |

| qPCR Assays for Validation | Provides high-sensitivity, targeted confirmation of discovered transcripts. | TaqMan Gene Expression Assays [16] |

| Serotonin maleate | Serotonin maleate, CAS:18525-25-2, MF:C14H16N2O5, MW:292.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Isosilybin A | Isosilybin A, CAS:142796-21-2, MF:C25H22O10, MW:482.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |