Short-Read vs. Long-Read RNA Sequencing: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

This article provides a definitive comparison of short-read and long-read RNA sequencing technologies for researchers and drug development professionals.

Short-Read vs. Long-Read RNA Sequencing: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a definitive comparison of short-read and long-read RNA sequencing technologies for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, platform-specific methodologies, and application-specific guidance for tumor biology, single-cell analysis, and target discovery. The content addresses key challenges like cost-benefit optimization, sample quality, and data analysis, offering a clear framework for technology selection. By synthesizing validation data and emerging trends, this guide empowers strategic decision-making to leverage transcriptomics in advancing precision medicine and therapeutic development.

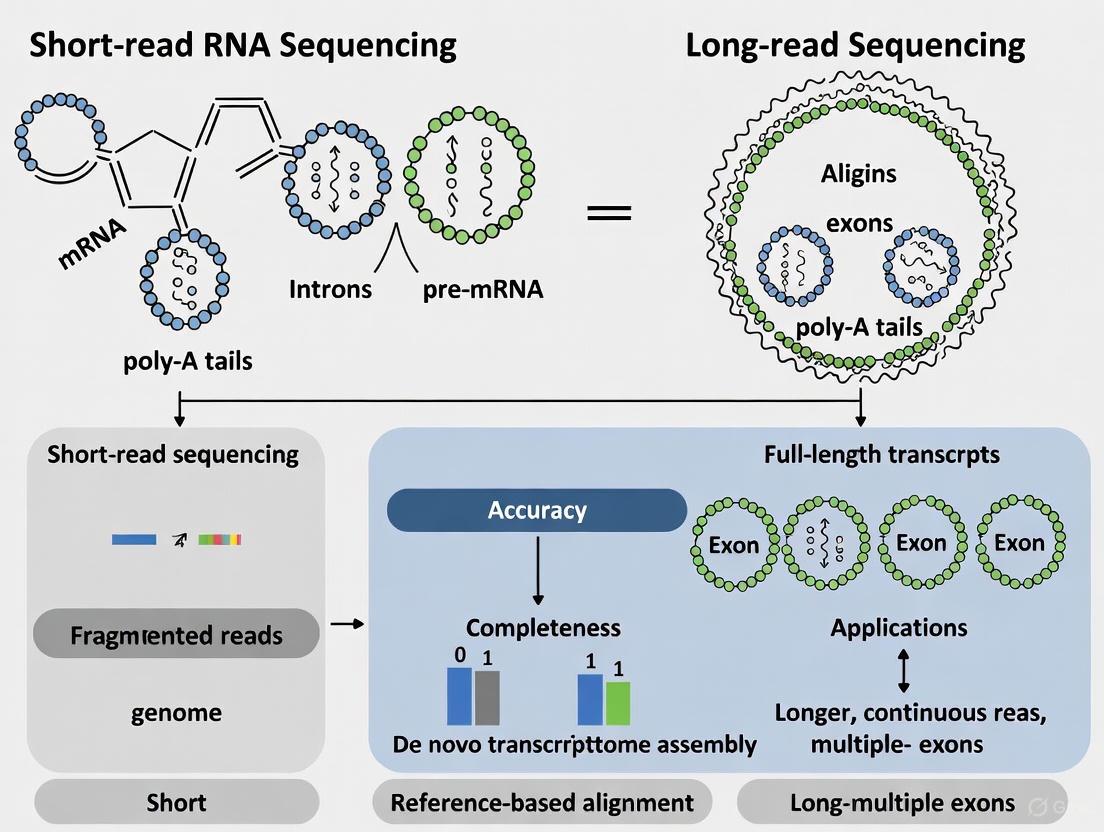

Core Technologies Demystified: How Short-Read and Long-Read Sequencing Work

The foundational choice between short-read and long-read sequencing technologies profoundly shapes the design, outcome, and interpretation of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) experiments. For over a decade, short-read sequencing (primarily Illumina) has been the undisputed gold standard for transcriptome profiling, offering high throughput and exceptional base accuracy [1]. Its dominance, however, is increasingly challenged by long-read sequencing technologies from Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), which enable the direct sequencing of full-length RNA transcripts in a single read [1] [2]. This capability is transformative for investigating the profound complexity of eukaryotic transcriptomes, where a single gene can produce numerous distinct isoforms through mechanisms like alternative splicing, alternative transcriptional start sites, and alternative polyadenylation [1]. While short-read methods infer this complexity indirectly by piecing together fragmented sequences, long-read technologies capture it directly, preserving the connectivity of distant exons [1]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these technologies, focusing on their core characteristics—read length, throughput, and chemistry—and summarizes key experimental data to inform researchers and drug development professionals navigating this evolving landscape.

Core Technical Specifications and Performance Comparison

The fundamental differences between short-read and long-read technologies are rooted in their underlying biochemistry and physics, leading to distinct performance profiles.

Table 1: Core Technical Specifications of Major RNA Sequencing Platforms

| Feature | Illumina Short-Read RNA-seq | PacBio Long-Read RNA-seq | ONT Long-Read RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Read Length | 50-300 bp [1] | Up to 25 kb [1] | Up to 4 Mb [1]; often 1,000-20,000+ bp [3] |

| Base Accuracy | ~99.9% [1] | ~99.9% (HiFi mode) [1] [3] | 95% - 99% (varies with chemistry) [1] |

| Throughput (per run/cell) | High (e.g., ~300,000 reads/cell in a scRNA-seq study [4]) | Moderate (improved with Kinnex/MAS-ISO-seq) [4] [1] | High (up to 277 Gb on PromethION flow cell) [1] |

| Core Chemistry | Sequencing-by-synthesis with fluorescently labelled nucleotides [5] | Single Molecule, Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing in zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs) [3] | Nanopore-based detection of ionic current changes [1] [5] |

| Key RNA-seq Applications | High-quality gene-level expression quantification [4] [6] | Full-length isoform discovery and quantification, variant detection [1] [3] | Full-length isoform analysis, direct RNA sequencing, detection of RNA modifications [1] [6] |

Short-read technology, exemplified by Illumina, is an ensemble method. It requires DNA polymerase and fluorescently labelled nucleotides to sequence millions of DNA clusters in parallel on a flow cell through sequencing-by-synthesis [5]. While it provides high-depth, high-accuracy data ideal for quantifying gene expression levels, its fundamental limitation is read length. The need to fragment transcripts before sequencing means the connectivity between distant exons is lost, making it challenging to resolve specific transcript isoforms [1].

In contrast, long-read platforms sequence single molecules. PacBio's HiFi sequencing employs circular consensus sequencing (CCS). DNA is circularized and sequenced multiple times by a polymerase immobilized at the bottom of a nanophotonic structure called a zero-mode waveguide (ZMW). This multi-pass approach generates a highly accurate consensus sequence (HiFi read) [3]. Oxford Nanopore's technology is physically distinct: it measures disruptions in an ionic current as a single RNA or DNA molecule is threaded through a protein nanopore. This allows for direct RNA sequencing without cDNA synthesis and enables the detection of RNA modifications [1] [6]. A key differentiator is that long reads can encompass a complete RNA transcript, directly revealing its full sequence and structure [2].

Experimental Comparisons and Benchmarking Data

Recent controlled studies provide empirical data on how these technical differences translate into practical performance.

Table 2: Key Findings from Comparative RNA-seq Studies

| Study (Source) | Experimental Design | Key Findings on Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma (ccRCC) Organoids [4] | Same 10x Genomics 3' cDNA from patient-derived organoids sequenced on Illumina (NovaSeq) and PacBio (Sequel IIe). | - Short-reads: Higher sequencing depth, recovered more UMIs per cell.- Long-reads: Retained transcripts <500 bp, enabled removal of truncated cDNA artefacts. Data from both methods were "highly comparable" for gene expression. |

| Singapore Nanopore Expression (SG-NEx) Project [6] | Systematic benchmark of 5 protocols (Illumina, ONT direct RNA, ONT direct cDNA, ONT PCR-cDNA, PacBio IsoSeq) across 7 human cell lines. | - Throughput: PCR-amplified cDNA (ONT & Illumina) generated highest throughput.- Read Length: PacBio IsoSeq and ONT direct RNA produced the longest reads.- Coverage: Long-read protocols showed more uniform 5'/3' coverage; short-reads had more reads assigned to multiple transcripts.- Bias: PacBio IsoSeq was depleted of shorter transcripts; PCR-based protocols over-amplified highly expressed genes. |

| Colorectal Cancer Genomics [7] | Comparison of Illumina whole-exome and Nanopore whole-genome sequencing on patient samples. | - Coverage: Illumina provided higher depth over target regions (e.g., ~105X vs ~21X for cancer samples).- Mapping Quality: Both were >99% accurate, with Illumina slightly higher (99.96% vs 99.89%). |

The SG-NEx project, a comprehensive benchmarking effort, found that while gene expression estimates are robustly correlated across all major RNA-seq protocols, each method introduces distinct biases [6]. For instance, PCR-amplified protocols (common in both short-read and some long-read workflows) can over-represent the most highly expressed genes, while PacBio's IsoSeq protocol was found to be significantly depleted of shorter transcripts [6]. This highlights that the library preparation method, not just the sequencing technology itself, is a critical source of bias.

In single-cell RNA-seq, a direct per-molecule comparison found that both Illumina and PacBio methods recover a large proportion of cells and transcripts from the same cDNA library, rendering "highly comparable results" for relevant gene signatures [4]. However, platform-specific processing allowed long-read sequencing to filter out artefacts identifiable only from full-length transcript data, demonstrating a unique advantage in data quality control [4].

Core Chemistry and Workflow Visualization

The experimental workflows for short-read and long-read sequencing are fundamentally different, from library preparation to base detection.

Diagram 1: Core Chemistry of Major Sequencing Platforms

This diagram illustrates the fundamental biochemical processes underlying the three major sequencing platforms.

Experimental Workflow for a Comparative Study

A typical experimental design for directly comparing sequencing technologies, as performed in the ccRCC organoid study [4], involves several key stages.

This workflow visualizes the methodology for a direct, per-molecule comparison of short and long-read sequencing from the same cDNA library [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of a comparative RNA-seq study requires careful selection of reagents and kits. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq Studies

| Item | Function | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium Single Cell 3' Kit | Partitions single cells into GEMs for barcoding and reverse transcription of full-length cDNA. | Used to generate the input cDNA for cross-platform sequencing in the ccRCC organoid study [4]. |

| PacBio MAS-ISO-seq for 10x Genomics Kit | Prepares 10x Genomics cDNA for long-read sequencing by removing TSO artefacts and concatenating transcripts. | Enabled high-throughput long-read scRNA-seq on the PacBio platform [4]. |

| Spike-in RNA Controls | Synthetic RNA molecules with known sequences and concentrations used to benchmark accuracy and quantification. | The SG-NEx project used Sequins, ERCC, and SIRVs to evaluate protocol performance [6]. |

| Solid-Phase Reversible Immobilization (SPRI) Beads | Used for post-reaction clean-up and size selection of cDNA libraries. | A standard step in both Illumina and PacBio library preparation protocols [4]. |

| Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) Cell | The nanofluidic device containing millions of ZMWs where PacBio sequencing occurs. | The core consumable for PacBio sequencing runs [3]. |

| Nanopore Flow Cell (e.g., PromethION) | The device containing the nanopore array where ONT sequencing occurs. | The core consumable for ONT sequencing runs [1]. |

| Pipercide | Pipercide - CAS 54794-74-0 - For Research Use | Pipercide is a natural insecticidal amide for entomology research. It targets voltage-gated sodium channels. This product is for research use only, not for human use. |

| Primin | Primin, CAS:15121-94-5, MF:C12H16O3, MW:208.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The choice between short-read and long-read RNA sequencing is not a simple matter of one technology being superior to the other. Instead, they offer complementary strengths. Short-read sequencing remains a powerful, cost-effective tool for applications where high-throughput, accurate gene-level quantification is the primary goal, such as differential gene expression studies in large cohorts [4] [6]. Long-read sequencing is transformative for applications that require resolving transcript isoform diversity, detecting fusion genes, characterizing non-coding RNAs, and identifying RNA modifications [1] [2]. Empirical data shows that while gene-level results are often highly correlated, long-reads provide a unique and often more accurate view of transcript-level biology [6].

The field continues to evolve rapidly. PacBio's Kinnex (formerly MAS-ISO-seq) and ONT's progressively more accurate chemistries are systematically addressing historical limitations of long-read technology, such as throughput and per-base accuracy [4] [1]. Concurrently, sophisticated computational tools and standardized pipelines like nf-core/nanoseq are maturing, making the analysis of long-read data more accessible [6]. For researchers and drug developers, the decision must be driven by the specific biological question. If the objective is to understand not just which genes are expressed but how they are spliced and processed into functional molecules, long-read RNA sequencing is increasingly becoming an indispensable, foundational technology [1] [8].

Short-read sequencing technologies are foundational to modern genomics, enabling high-throughput genetic analysis that drives research and drug development. These methods can be broadly categorized into three core biochemical approaches: Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS), Sequencing by Binding (SBB), and Sequencing by Ligation (SBL). Each technology employs distinct mechanisms for parallel sequencing of billions of DNA fragments, typically generating reads of 50 to 300 bases [9]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these methodologies, detailing their operational principles, performance characteristics, and experimental considerations to inform scientific and clinical application choices.

Core Technologies and Methodologies

Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS)

SBS methods utilize DNA polymerase to synthesize a complementary strand to the DNA template. Nucleotide incorporation is detected via one of two primary methods:

- Fluorescently-Labeled Nucleotides with Reversible Blockers: The process involves the incorporation of a fluorescently-labeled nucleotide, which also contains a reversible terminator that halts the synthesis reaction. After imaging to identify the incorporated base, the fluorescent dye and blocker are chemically removed, allowing the next nucleotide to be incorporated [9]. This cyclical process is characteristic of platforms like Illumina.

- Unmodified Nucleotides with Sequential Addition: In this "sequencing-by-synthesis-by-pH-change" method, unmodified nucleotides (A, T, G, C) are flowed sequentially. The incorporation of a nucleotide by polymerase releases a hydrogen ion, causing a detectable local pH change. The signal is proportional to the number of identical nucleotides incorporated consecutively. Unincorporated nucleotides are washed away before introducing the next type [9] [10]. This principle is used by Ion Torrent technology.

Sequencing by Binding (SBB)

SBB also uses a polymerase enzyme but separates the nucleotide identification and incorporation steps, creating a more natural DNA synthesis process [10]. The workflow for a single base extension is as follows:

- A primer hybridized to the template DNA has a reversible blocker attached.

- Fluorescently-labeled nucleotides are introduced. The complementary nucleotide binds transiently to the template, and its fluorescent signal is imaged.

- Because of the blocker, the labeled nucleotide cannot be incorporated and is washed away.

- The blocker on the primer is then chemically removed, and unlabeled nucleotides with reversible blockers are added, allowing the polymerase to extend the DNA strand by a single base [9].

This technology is implemented in platforms like the Element Biosciences AVITI System [10].

Sequencing by Ligation (SBL)

SBL employs DNA ligase instead of polymerase to determine the sequence. The process uses short oligonucleotide probes of known sequence that are fluorescently labeled. The ligase enzyme preferentially joins the probe that perfectly matches the template strand. The fluorescent signal of the successfully ligated probe identifies the base sequence. After imaging, the complex is cleaved to remove the fluorescent label and prepare for the next ligation cycle [9]. A historical example of this technology is SOLiD sequencing, which is noted to struggle with palindromic sequences that can form hairpin structures and evade ligation [9] [10].

The following diagram illustrates the core logical workflow and key differences between these three primary short-read sequencing methods.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The different chemistries of SBS, SBB, and SBL lead to distinct performance profiles, which are critical for experimental planning. The table below summarizes key quantitative and qualitative characteristics based on current technologies and literature.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Short-Read Sequencing Technologies

| Feature | Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) | Sequencing by Binding (SBB) | Sequencing by Ligation (SBL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read Length | 50-300 bp [9] | Up to 300 bp (e.g., AVITI System) [10] | 50-100 bp (historical) [10] |

| Primary Detection Method | Fluorescence (Illumina) or pH change (Ion Torrent) [9] [10] | Fluorescence (transient binding) [9] [10] | Fluorescence (ligation) [9] |

| Typical Accuracy | High (Q30+ common) [10] | Very High (Q40+ reported) [10] | High, but challenged by palindromes [9] |

| Throughput | Very High | High | Moderate to High (historical) |

| Library Prep Time | Varies; can be multistep [10] | Not specified in results | Multistep and laborious [10] |

| Key Strengths | High throughput, established workflows, low cost per base [11] [9] | High accuracy, reduced enzyme bias [10] | Robustness in some sequence contexts |

| Key Limitations | Amplification biases, short reads struggle with repeats [10] | Newer platform, smaller ecosystem | Inefficient with hairpin-forming sequences [9] |

| Example Platforms | Illumina, Ion Torrent [10] | Element Biosciences AVITI [10] | SOLiD (discontinued) [10] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of short-read sequencing requires a suite of specialized reagents and kits. The following table details key components used in typical workflows.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Short-Read Sequencing

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Library Preparation Kits | Fragment DNA, repair ends, add platform-specific adapters, and amplify the library. | Used in all short-read protocols to convert raw nucleic acids into a sequencer-compatible format [10]. |

| Platform-Specific Flow Cells/ Chips | Solid surface where clonal amplification and the sequencing reaction occur. | Illumina's patterned flow cells for bridge amplification; Ion Torrent's chips for pH detection [10] [12]. |

| Polymerase or Ligase Enzymes | Key enzyme driving the sequencing reaction (SBS/SBB: polymerase; SBL: ligase). | Highly engineered enzymes are critical for incorporating nucleotides (SBS) or binding probes (SBB) with high fidelity and efficiency [9]. |

| Fluorescently-Labeled Nucleotides/Probes | Identify the base sequence during the detection phase of the cycle. | Reversible terminators in Illumina SBS; fluorescent probes in SBL [9]. |

| Unique Dual Indexes (UDIs) | Barcode sequences added during library prep to multiplex samples. | Allows pooling and simultaneous sequencing of dozens of samples, reducing cost per sample [4]. |

| Solid-Phase Reversible Immobilization (SPRI) Beads | Magnetic beads for size selection and cleanup of DNA fragments between library prep steps. | Used for purifying and selecting appropriately sized cDNA libraries after amplification [4]. |

| Quercetagitrin | Quercetagitrin, CAS:548-75-4, MF:C21H20O13, MW:480.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ayanin | Ayanin, CAS:572-32-7, MF:C18H16O7, MW:344.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Contextualizing Short-Reads in the Broader Sequencing Landscape

While powerful, short-read technologies have inherent limitations. Their primary challenge is the inability to sequence long, continuous stretches of DNA. Genomes must be fragmented, and computer programs assemble these short reads into a continuous sequence. This process can fail in complex regions, leading to gaps and ambiguities, particularly in areas with large structural variations, highly repetitive sequences, or to resolve specific transcript isoforms [10] [6].

This limitation is the driving force behind the development and adoption of long-read sequencing technologies (PacBio HiFi and Oxford Nanopore). Long-reads can span entire repetitive elements or genes in a single read, simplifying genome assembly and enabling the direct detection of isoform-level expression in transcriptomics [13] [10]. However, long-read sequencing has historically faced challenges with higher error rates and cost, though these have improved dramatically [13] [10].

The choice between short-read and long-read technologies is therefore application-dependent. Short-reads remain the gold standard for high-throughput, cost-effective applications like variant calling, gene expression quantification (gene-level), and targeted sequencing [9]. In contrast, long-reads are indispensable for de novo genome assembly, resolving structural variants, and full-length transcript isoform analysis [13] [6].

The transition from short-read to long-read RNA sequencing represents a paradigm shift in transcriptomics. While conventional short-read methods (50-300 bases) have provided valuable gene-level expression data, their inherent limitations in resolving complex isoforms, alternative splicing events, and base modifications have constrained our understanding of transcriptional regulation [13] [8]. Long-read technologies from Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) now enable end-to-end sequencing of full-length transcripts, capturing the complete complexity of RNA molecules without the need for assembly [14]. This technological advancement is particularly crucial for researchers and drug development professionals investigating diseases where alternative splicing, novel isoforms, and RNA modifications play critical roles, such as in cancer, neurological disorders, and rare genetic conditions [15] [16].

The fundamental distinction between these platforms lies in their underlying chemistry and data output characteristics. PacBio's HiFi (High Fidelity) sequencing employs circular consensus sequencing (CCS) to generate highly accurate long reads (15-20 kb) with quality scores exceeding Q30 (99.9% accuracy) [13] [14]. In contrast, Oxford Nanopore Technologies sequences native RNA or DNA molecules by detecting changes in electrical current as nucleic acids pass through protein nanopores, enabling ultra-long reads (sometimes exceeding 100 kb) and direct detection of RNA modifications [13] [17]. Each approach offers distinct advantages for specific research applications, from comprehensive isoform characterization to real-time detection of epigenetic modifications.

Technology Comparison: PacBio HiFi vs. Oxford Nanopore

Core Methodologies and Performance Characteristics

The following table summarizes the fundamental technical specifications and performance metrics of both platforms, providing researchers with objective data for platform selection.

Table 1: Technical comparison of PacBio HiFi and Oxford Nanopore sequencing platforms

| Parameter | PacBio HiFi Sequencing | Oxford Nanopore Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| Technology Principle | Fluorescent detection of nucleotide incorporation by polymerase in SMRT cells | Measurement of current changes as molecules pass through protein nanopores |

| Read Length | 500 bp - 20 kb [13] | 20 kb to >4 Mb; can exceed 100 kb [13] |

| Raw Read Accuracy | ~99.9% (Q30+) [13] [14] | ~99% (Q20) with recent improvements [13] [18] |

| Typical Run Time | 24 hours [13] | Up to 72 hours [13] |

| Typical Yield per Flow Cell | 60-120 Gb [13] | 50-100 Gb [13] |

| Input Requirements | DNA, cDNA [13] | Native DNA, RNA, cDNA [13] [17] |

| DNA Modification Detection | 5mC, 6mA without bisulfite treatment [13] | 5mC, 5hmC, 6mA; direct detection [13] |

| Variant Calling | SNVs, indels, structural variants [13] | SNVs, structural variants; challenges with indels in repetitive regions [13] |

| Base Calling | On-instrument (no additional cost) [13] | Off-instrument, often requires costly GPU servers [13] |

| Portable Sequencing | Not available | MinION, Flongle available [13] [14] |

| File Storage Requirements | 30-60 GB (BAM format) [13] | ~1,300 GB (FAST5/POD5 format) [13] |

Workflow and Data Analysis Considerations

Beyond the technical specifications, practical implementation factors significantly impact platform selection. PacBio systems perform basecalling on-instrument, generating analysis-ready BAM files with minimal computational overhead [13]. In contrast, Oxford Nanopore requires substantial computational resources for basecalling, often necessitating expensive GPU servers that increase the total cost of ownership [13]. Storage requirements also differ dramatically, with Nanopore datasets (~1,300 GB per genome) demanding approximately 20 times more storage than PacBio outputs (30-60 GB per genome) [13].

For transcriptomics, both platforms offer distinct approaches. PacBio's HiFi sequencing of cDNA provides exceptional accuracy for isoform quantification and discovery, while Oxford Nanopore enables direct RNA sequencing that preserves native modification information [6] [17]. The selection between these approaches depends on the research priorities: accurate quantification of known and novel isoforms (PacBio) versus detection of RNA modifications alongside sequence information (ONT Direct RNA Sequencing).

Diagram 1: Technology selection workflow for long-read RNA sequencing

Direct RNA Sequencing: A Specialized Nanopore Application

Oxford Nanopore's Direct RNA Sequencing (DRS) represents a distinctive approach that sequences native RNA molecules without reverse transcription or amplification [17]. This methodology preserves base modifications and eliminates amplification biases, providing a direct view of the epitranscriptome. The workflow begins with RNA extraction followed by adapter ligation to the 3' poly(A) tail. The prepared library is then loaded onto flow cells where motor proteins unwind RNA molecules and guide them through nanopores. As each RNA molecule passes through the pore, distinct current disruptions corresponding to specific RNA bases and their modifications are recorded in real-time [17].

Recent advancements in Nanopore chemistry, particularly the RNA004 kit with updated motor proteins and 9-mer signal detection, have substantially improved basecalling accuracy compared to previous versions [19] [17]. However, DRS still faces challenges with complete 5' end coverage since sequencing initiates at the 3' poly(A) tail, potentially missing information about 5' cap structures and beginning of transcripts [6]. Despite this limitation, the ability to simultaneously detect sequence information and RNA modifications in a single assay makes DRS uniquely valuable for studying the functional role of epitranscriptomic modifications in development, disease, and therapeutic response [19].

Experimental Design Considerations

Effective Direct RNA Sequencing requires careful experimental planning. The recommended input is 500 ng of poly(A)-enriched RNA, though lower inputs can be accommodated with potential trade-offs in library complexity [17]. Unlike cDNA-based approaches, DRS does not require fragmentation or amplification, simplifying library preparation but potentially introducing biases based on RNA secondary structure and modification density. Researchers should include appropriate controls, such as in vitro transcribed (IVT) RNA, to distinguish true modifications from sequence-specific artifacts [19].

The bioinformatic analysis of DRS data demands specialized tools for basecalling, alignment, and modification detection. The standard workflow includes raw signal processing with Guppy or Dorado basecallers, alignment with minimap2 or GraphMap, and modification detection with specialized tools like m6Anet or Nanocompore [19] [17]. Computational requirements remain substantial, with basecalling typically requiring GPU acceleration and significant storage capacity for raw signal data (FAST5/POD5 files).

Diagram 2: Nanopore Direct RNA Sequencing workflow and advantages

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Evidence

Transcriptomics Applications

Recent comprehensive benchmarking studies provide critical insights into platform performance for transcript-level analysis. The Singapore Nanopore Expression (SG-NEx) project compared five RNA-seq protocols across seven human cell lines, offering one of the most systematic comparisons to date [6]. This study found that PacBio IsoSeq generated the longest reads on average and, together with Nanopore's PCR-amplified cDNA protocol, showed the most uniform coverage across transcript lengths and the highest proportion of reads spanning all exon junctions ("full-splice-match reads") [6].

For gene expression quantification, Nanopore long-read RNA-seq demonstrated the lowest estimation error and highest correlation with known spike-in RNA concentrations across multiple computational quantification methods [6]. However, PacBio's HiFi sequencing consistently outperforms for variant detection, with one study showing it detected approximately three times more true positive single nucleotide variants (SNVs) than Oxford Nanopore, making it particularly valuable for allele-specific expression studies [16]. The exceptional accuracy of HiFi reads also enables reliable detection of insertions and deletions (indels), which remains challenging for Nanopore technology, particularly in repetitive regions [13].

Table 2: Performance comparison in recent benchmarking studies

| Application | PacBio HiFi Performance | Oxford Nanopore Performance | Reference Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full-length Transcript Detection | Identified >180,000 mRNA isoforms (>50% novel) in lung adenocarcinoma [15] | Robust identification of major isoforms; lower uniformity with direct RNA [6] | SG-NEx [6] |

| SNV Detection | ~3× more true positives compared to ONT [16] | Lower SNP calling performance due to higher error rates [16] | HPRC Kinnex [16] |

| Species-level Taxonomic Resolution | 63% of sequences classified to species level [18] | 76% of sequences classified to species level [18] | Rabbit gut microbiota [18] |

| RNA Modification Detection | Not applicable for direct RNA modification detection | m6A detection: Dorado recall ~0.92, m6Anet recall ~0.51 at ≥10% modification sites [19] | RNA004 benchmarking [19] |

| Differential Expression Analysis | Strong concordance with Illumina (Pearson >0.9 gene level) with lower inferential variability [16] | High correlation with expected spike-in concentrations; some protocol-specific biases [6] | Kinnex benchmarking [16] |

Specialized Research Applications

Ultra-low Input Sequencing

Recent advancements have extended long-read sequencing to challenging sample types. PacBio's ultralow-input (ULI) protocol, now refined as the AmpliFi protocol, enables comprehensive variant detection with as little as 1-10 ng of input DNA [15]. This capability is particularly valuable for clinical samples where material is limited, such as tumor biopsies, fine-needle aspirates, and single cells. In application to hereditary colorectal cancer samples, ULI-HiFi sequencing revealed progressive tandem repeat expansion in a tumor suppressor gene across normal tissue, polyp, and adenocarcinoma samples, demonstrating the power of long-read sequencing for capturing dynamic genomic changes in disease progression [15].

Epigenetics and Methylation Profiling

For epigenomic studies, PacBio HiFi sequencing provides a more complete view of the DNA methylome compared to whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS). In a twin study, HiFi sequencing identified approximately 5.6 million more CpG sites than WGBS, particularly in repetitive elements and regions of low coverage with bisulfite-based methods [15]. The coverage pattern of HiFi sequencing showed a uniform distribution peaking at 28-30×, with over 90% of CpGs achieving ≥10× coverage, compared to approximately 65% in WGBS datasets [15]. This comprehensive coverage enables de novo DNA methylation analysis, reporting CpG sites beyond reference sequences without the DNA damage associated with bisulfite conversion.

Repeat Expansion Disorders

Long-read sequencing has revolutionized the diagnosis of repeat expansion disorders that often evade detection by short-read technologies. In one study of Familial Adult Myoclonic Epilepsy type 3 (FAME3), PacBio HiFi sequencing identified a pathogenic MARCHF6 intronic expansion that had been missed by multiple rounds of exome and genome testing [15]. The analysis revealed that affected individuals carried one allele with 15 TTTTA repeats and a second allele with a compound expansion of 661 TTTTA and 12 TTTCA repeats, with increasing repeat sizes in later generations [15]. This study highlighted that disease manifestation requires TTTCA repeats in tandem with TTTTA motifs, demonstrating the importance of assessing both repeat length and composition—a capability uniquely provided by long-read sequencing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational tools for long-read RNA sequencing

| Item | Function | Example Products/Platforms |

|---|---|---|

| Library Preparation Kits | Convert RNA to sequence-ready libraries | PacBio Kinnex RNA Single-Cell Kit, ONT Direct RNA Sequencing Kit (SQK-RNA004) |

| Polymerase Enzymes | Amplify cDNA for sequencing | KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (PacBio), Long Amp Taq (Nanopore) |

| Barcoding Systems | Multiplex samples in a single run | PacBio Multiplexed Barcoded Adapters, ONT Native Barcoding kits |

| Flow Cells/Consumables | Platform-specific sequencing substrates | SMRT Cells (PacBio), MinION/PromethION Flow Cells (ONT) |

| Basecalling Software | Convert raw signals to nucleotide sequences | Dorado (ONT), SMRT Link (PacBio) |

| Modification Detection Tools | Identify RNA modifications from sequencing data | m6Anet, Nanocompore (ONT) |

| Alignment & Quantification | Map reads and quantify expression | Minimap2, StringTie, Bambu |

| Quality Control Tools | Assess read quality and library preparation | NanoPlot (ONT), SMRT Link Quality Control (PacBio) |

| Reference Databases | Taxonomic classification and annotation | SILVA, Greengenes (16S rRNA); GENCODE, RefSeq (mRNA) |

| Rapanone | Rapanone, CAS:573-40-0, MF:C19H30O4, MW:322.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ryanodine | Ryanodine, CAS:15662-33-6, MF:C25H35NO9, MW:493.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The choice between PacBio HiFi and Oxford Nanopore technologies depends fundamentally on research priorities. PacBio's exceptional accuracy (Q30+) makes it ideally suited for applications requiring high-confidence variant calling, including SNVs, indels, and structural variants [13] [16]. This precision is particularly valuable in clinical research and diagnostic development where false positives carry significant consequences. Additionally, PacBio's uniform coverage and lower computational requirements provide practical advantages for laboratories with limited bioinformatics infrastructure [13].

Oxford Nanopore offers distinctive capabilities through its Direct RNA Sequencing platform, enabling simultaneous detection of sequence information and RNA modifications without additional chemical treatments or conversion steps [19] [17]. The platform's portability and real-time sequencing capabilities further expand its utility for field applications and rapid diagnostics [13] [14]. However, these advantages come with higher computational demands for basecalling and substantially larger storage requirements for raw signal data [13].

For drug development professionals, these technologies open new avenues for biomarker discovery, therapeutic target identification, and understanding drug mechanisms at the transcriptome level. The ability to fully characterize isoform-specific expression, allele-specific regulation, and epitranscriptomic modifications provides unprecedented insight into disease mechanisms and treatment responses [15] [16]. As these technologies continue to evolve, with both platforms demonstrating rapid improvements in accuracy, throughput, and accessibility, long-read RNA sequencing is positioned to become a foundational technology for both basic research and translational applications.

In the field of genomics, the fundamental requirement for nearly all applications is accurate base calling. The inherent limitations of sequencing technologies, however, introduce errors that researchers must carefully manage. This challenge is particularly pronounced in long-read sequencing, which, despite providing invaluable long-range genomic information, has historically been hampered by higher error rates compared to short-read technologies [1]. To bridge this accuracy gap, sophisticated computational methods have been developed, with circular consensus sequencing (CCS) emerging as a powerful approach for generating highly accurate long reads [20].

This guide provides a objective comparison of the accuracy and error profiles of modern sequencing platforms, focusing on the critical role of quality scores (Q scores) and consensus methods. We present summarized experimental data, detailed protocols, and analytical tools to help researchers and drug development professionals navigate the evolving landscape of sequencing technologies for their RNA research.

Understanding Q Scores and Consensus Sequencing

The Metric of Accuracy: Q Scores

In sequencing data, a Q score (or Phred quality score) is a logarithmic measurement that predicts the probability of an incorrect base call. A higher Q score indicates a lower probability of error. For example, a Q score of 30 (Q30) corresponds to a 1 in 1,000 error rate, or 99.9% accuracy. The relationship between Q scores and accuracy follows a logarithmic scale, where each 10-point increase represents a tenfold decrease in error probability [10] [20].

The Path to Precision: Consensus Sequencing

Consensus sequencing is a strategy that sequences the same DNA molecule multiple times to generate a highly accurate consensus sequence. This approach effectively randomizes and cancels out stochastic errors inherent in single reads. Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS), also known as HiFi sequencing from PacBio, implements this by circularizing DNA molecules and sequencing them multiple passes to produce highly accurate (99.8%) long reads [21] [20]. This method has revolutionized long-read genomics by providing both length and accuracy.

Technology Comparison: Accuracy and Error Profiles

Table 1: Sequencing Platform Performance Characteristics

| Platform/Technology | Read Length | Raw Read Accuracy | Consensus Accuracy (CCS) | Primary Error Type | Optimal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PacBio HiFi (CCS) | 10-25 kb [1] [20] | ~90% (single pass) [20] | 99.9% (Q30) [1] [20] | Homopolymer indels [20] | Genome assembly, variant detection, haplotype phasing [20] |

| Oxford Nanopore (ONT) | Up to 4 Mb [1] | 95%-99% (R10.4 chemistry) [1] | >99% (with deep coverage) [10] | Systematic errors [10] | Direct RNA sequencing, structural variants, real-time analysis [1] |

| Illumina Short-Read | 50-300 bp [1] | 99.9% [1] | N/A | Substitution errors [20] | SNV detection, expression quantification, targeted sequencing [1] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Benchmarks from Recent Studies

| Performance Metric | PacBio HiFi | Oxford Nanopore | Illumina Short-Read |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNV Precision/Recall | >99.91% [20] | >99.9% (with Clair3/DeepVariant) [22] | >99.9% [20] |

| Indel Precision/Recall | 95.98% [20] | High (with deep learning callers) [22] | >99% [20] |

| Mapping Rate | Highest (97.5%) [20] | ~85% [23] | 94.8% [20] |

| Homopolymer Error Rate | 1 per 477 bp [20] | Improved with R10.4 chemistry [22] | Very low |

| Mismatch Rate | 1 per 13,048 bp [20] | Higher than short-read (context-dependent) [23] | 1 per 225,000 bp [20] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Accuracy

Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) Library Preparation

The following protocol for generating high-accuracy long reads has been optimized for PacBio systems [21] [20]:

DNA Fragmentation and Size Selection: High molecular weight (HMW) DNA is extracted and sheared to a tight size distribution around 15 kb using systems like the Megaruptor 3. This controlled fragmentation is crucial for optimizing polymerase read length and consensus accuracy.

Library Construction with Pre-extension: The sheared DNA is converted to a SMRTbell library via end-repair, A-tailing, and hairpin adapter ligation. A critical "pre-extension" step is employed where the polymerase extends without laser illumination. This eliminates polymerases on damaged templates before sequencing begins, significantly improving read length and yield.

Sequencing and Consensus Generation: The library is sequenced on PacBio Sequel IIe or Revio systems with collection times adjusted to maximize polymerase survival. The circularized molecules are sequenced multiple times (typically ≥10 passes), and CCS algorithms generate highly accurate consensus sequences from these subreads with calibrated quality scores.

Accuracy Validation and Benchmarking

To validate the accuracy of consensus sequences and quality scores, researchers employ these established methods [21] [20] [23]:

GIAB Benchmark Comparison: Sequence data is aligned to well-characterized human reference genomes from the Genome in a Bottle (GIAB) Consortium, such as HG002/NA24385. Precision and recall are calculated for single nucleotide variants (SNVs), insertions/deletions (indels), and structural variants against the validated benchmark variant set.

Umbilical Cord Blood Analysis: For somatic variant calling applications, sequencing data from umbilical cord blood (which has an exceedingly low number of true somatic variants due to its relatively young age) is analyzed. Bases that differ from the reference but are not at germline variant locations are counted as errors, providing a real-world measure of accuracy.

Read-to-Read Alignment: An independent method where reads are aligned to each other instead of a reference genome. This approach estimates error rates and identifies artifacts like molecular chimeras (0.5% in CCS reads) and low-quality base runs, providing orthogonal validation of sequence quality.

Visualizing Sequencing and Analysis Workflows

Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) Workflow

Diagram 1: CCS sequencing generates highly accurate long reads by sequencing circularized DNA molecules multiple times and deriving a consensus sequence from the subreads [21] [20].

TopoQual Error Correction and Quality Refinement

Diagram 2: The TopoQual algorithm uses partial order alignment and deep learning to polish consensus sequences and predict more accurate base quality scores [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for Sequencing Accuracy Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| TopoQual [21] | Software | Polishes CCS data using partial order alignments and deep learning | Corrects ~31.9% of errors in PacBio consensus sequences; validates base qualities up to q59 |

| MAS-ISO-seq/Kinnex [4] | Library Prep | Concatenates transcripts for efficient long-read RNA sequencing | Enables high-throughput scRNA-seq with isoform resolution; retains transcripts <500 bp |

| DeepVariant/Clair3 [22] | Variant Caller | Deep learning-based variant detection from sequencing data | Significantly outperforms traditional methods on ONT data; matches/exceeds Illumina accuracy |

| GIAB Reference Materials [20] [23] | Benchmark | Well-characterized human genome standards for validation | Provides ground truth for accuracy assessment across platforms and pipelines |

| SMRTbell Prep Kit [20] | Library Prep | Reagents for constructing circular sequencing libraries | Essential for PacBio HiFi sequencing with optimized adapter ligation |

| Nanoseq Pipeline [6] | Bioinformatics | Community-curated workflow for long-read RNA-seq data | Performs quality control, alignment, transcript discovery, and quantification |

| Sorbifolin | Sorbifolin|High-Purity Flavone|Research Use Only | Sorbifolin, a bioactive flavone for research. Explore its applications in antiviral, antioxidant, and anticancer studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Sennidin A | Sennidin A, CAS:641-12-3, MF:C30H18O10, MW:538.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The evolution of sequencing technologies, particularly through consensus methods like PacBio HiFi, has dramatically narrowed the accuracy gap between long-read and short-read platforms. While each technology maintains distinct error profiles—with long reads excelling in complex genomic regions and short reads providing exceptional base-level precision—the emergence of sophisticated computational tools like TopoQual and DeepVariant further enhances data quality [21] [22].

For researchers designing sequencing studies, the choice between platforms now depends less on raw accuracy alone and more on the specific genomic contexts of interest, required read lengths, and the complementarity of these technologies. The experimental protocols and benchmarking frameworks presented here provide a foundation for rigorous assessment of sequencing accuracy in diverse research applications, from basic transcriptome characterization to clinical diagnostics and drug development.

The field of genomic sequencing has undergone a revolutionary transformation with the advent of third-generation sequencing (TGS) technologies. Unlike their second-generation predecessors, which rely on amplified DNA fragments and produce short reads, TGS platforms from Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) enable single-molecule, real-time sequencing of long nucleic acid fragments. This evolution has fundamentally addressed one of the most significant initial limitations of TGS: high error rates. Through continuous technological refinement, TGS has progressed to offer remarkable fidelity while maintaining its inherent advantages for resolving complex genomic regions, characterizing structural variations, and providing full-length transcriptomic views. This guide objectively compares the performance of modern high-fidelity TGS with both short-read sequencing and earlier long-read approaches, providing researchers with critical insights for selecting appropriate sequencing strategies.

Historical Context and Technological Foundations

The Sequencing Technology Landscape

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) encompasses several technological generations that have progressively enhanced our ability to decode genetic information. First-generation sequencing, exemplified by Sanger's chain-termination method, provided accurate but low-throughput sequencing capabilities [24]. Second-generation sequencing (short-read technologies) from platforms like Illumina revolutionized genomics through massive parallel sequencing, offering high accuracy at reduced costs but producing fragments typically between 50-300 base pairs [24] [25]. These short reads struggle to resolve repetitive elements, structural variations, and complex genomic regions.

Third-generation sequencing emerged around 2011 with fundamentally different approaches [26]. PacBio's Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) technology and ONT's nanopore sequencing enabled the direct sequencing of single DNA or RNA molecules without amplification, producing reads that can span thousands to hundreds of thousands of bases [24] [26]. This technological leap came with an initial trade-off: early TGS platforms exhibited error rates substantially higher than Illumina's >99.9% base-calling accuracy [27] [25].

The High Error Rate Challenge

The initial limitations of TGS stemmed from their distinct sequencing chemistries. Early PacBio SMRT sequencing was prone to indels due to the instability of molecular machinery, while ONT's signal interpretation was complicated by adjacent base signal interference [27]. These technical challenges resulted in error rates that could reach 10-15% in some applications, posing significant obstacles for detecting single-nucleotide variants within the context of minimal genetic variation between individuals [24] [27].

The Path to High Fidelity: Technological Advancements

PacBio's HiFi Sequencing Breakthrough

Pacific Biosciences addressed accuracy challenges through the development of HiFi (High-Fidelity) sequencing. This approach uses circular consensus sequencing (CCS), where DNA molecules are sequenced repeatedly in a looped format. By generating multiple observations of each base, HiFi sequencing achieves accuracy exceeding 99.9% while maintaining read lengths of 10-25 kilobases [28] [24]. This technological advancement has made PacBio HiFi suitable for applications requiring both long reads and high accuracy, including variant detection, haplotype phasing, and assembly of complex genomes.

Nanopore's Accuracy Enhancements

Oxford Nanopore Technologies has progressively improved its sequencing accuracy through enhanced nanopore chemistries, motor enzymes, and base-calling algorithms. While early ONT platforms had error rates around 5-15%, recent developments have substantially improved performance [24] [6]. The SG-NEx project benchmarking demonstrated that ONT can now robustly identify major isoforms and detect complex transcriptional events, though it still trails PacBio in certain SNP calling applications [6].

Comparative Performance of Modern Sequencing Platforms

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Major Sequencing Technologies

| Platform | Read Length | Accuracy | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | 50-300 bp | >99.9% | High throughput, low cost per base, well-established bioinformatics | Short reads struggle with repeats and structural variants |

| PacBio HiFi | 10,000-25,000 bp | >99.9% | Long reads with high accuracy, excellent for structural variants and haplotype phasing | Higher cost per base, lower throughput than Illumina |

| PacBio Onso | 100-200 bp | High (SBB chemistry) | Targeted sequencing with binding chemistry | Higher cost compared to other targeted approaches |

| Oxford Nanopore | 10,000-30,000+ bp | Improved (recent platforms) | Ultra-long reads, direct RNA sequencing, portability | Higher error rates than HiFi, though improving |

Table 2: RNA Sequencing Protocol Comparisons (SG-NEx Benchmark)

| Protocol | Average Read Length | Throughput | 5'/3' Coverage | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina Short-Read | Fixed by protocol | Very high | Fragmentation biases | Gene-level expression, large sample numbers |

| PacBio Iso-Seq | Longest on average | High (with Kinnex) | Uniform coverage | Full-length isoform discovery, novel splicing |

| Nanopore Direct RNA | Long | Moderate | Higher at 3' end | Native RNA detection, modification analysis |

| Nanopore cDNA PCR | Long | Highest for Nanopore | Uniform coverage | Standard isoform expression profiling |

Experimental Evidence: Demonstrating Modern TGS Performance

Benchmarking Studies and Performance Metrics

Recent comprehensive benchmarks have quantitatively established the capabilities of modern TGS. The Singapore Nanopore Expression (SG-NEx) project, one of the most extensive comparisons of RNA sequencing protocols, found that long-read RNA sequencing more robustly identifies major isoforms compared to short-read approaches [6]. The study reported that PacBio IsoSeq generated the longest reads on average with uniform coverage across transcripts, while Nanopore cDNA sequencing achieved the highest throughput for long-read protocols [6].

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Comparison

A systematic comparison of single-cell long-read and short-read sequencing demonstrated that both methods yield highly comparable results for standard gene expression analysis [4]. However, long-read sequencing provided the crucial advantage of isoform resolution, enabling the identification of 44,325 transcript isoforms in mouse retina cells, with 38% previously uncharacterized and 17% expressed exclusively in distinct cellular subclasses [29]. This study highlighted that while short-read sequencing provided higher sequencing depth, long-read sequencing allowed for identification of full-length transcripts and removal of technical artifacts [4].

Targeted Benchmarking of PacBio Kinnex

Recent evaluations of PacBio's high-throughput Kinnex kits revealed exceptionally strong concordance with Illumina data, with Pearson correlations exceeding 0.9 at the gene level and approaching 0.9 at the transcript level [16]. Importantly, the study found that "Illumina exhibited substantially higher inferential variability compared to Kinnex," with greater replicate-to-replicate fluctuations in transcript abundance estimates [16]. This demonstrates that modern TGS not only matches short-read accuracy but exceeds it in quantification consistency for complex isoforms.

Methodologies: Experimental Protocols for TGS Applications

PacBio HiFi Metagenomics Protocol

Metagenomics studies have particularly benefited from HiFi sequencing. The standard protocol involves:

- DNA Extraction: High-molecular-weight DNA extraction using kits optimized for long fragments

- Library Preparation: SMRTbell library construction with DNA repair, end-prep, and adapter ligation

- Size Selection: BluePippin or Circulomics size selection to enrich for longer fragments

- Sequencing: Loading on SMRT cells for circular consensus sequencing on Sequel IIe or Revio systems

- Data Processing: CCS read generation yielding HiFi reads with >99.9% accuracy [28]

This approach has demonstrated superior capability in recovering complete and coherent microbial genomes from complex microbiomes compared to both short-read and earlier long-read technologies [28].

Single-Cell Isoform Sequencing (Iso-Seq) Workflow

For comprehensive transcriptome profiling, the Iso-Seq protocol enables full-length transcript characterization:

- cDNA Synthesis: Full-length cDNA generation with template-switching reverse transcription

- PCR Optimization: Amplification with minimal bias using high-fidelity polymerases

- SMRTbell Library Preparation: Construction of libraries suitable for PacBio sequencing

- Size Selection: Fractionation to prioritize longer transcripts

- Sequencing: Single-molecule real-time sequencing capturing complete transcripts

- Bioinformatic Processing: CCS analysis, isoform clustering, and quantification [29] [16]

This methodology has been instrumental in revealing previously unannotated isoforms, with studies identifying approximately 40% novel transcripts not present in reference annotations [16].

Nanopore Direct RNA Sequencing Protocol

For native RNA analysis without cDNA conversion:

- RNA Quality Control: Assessment of RNA integrity number (RIN) >8.5

- Adapter Ligation: Poly(A) tail capture and adapter ligation

- Library Loading: Direct loading of RNA-library complexes onto flow cells

- Sequencing: Real-time sequencing through nanopores

- Base Calling: Signal processing to sequence while preserving modification information [6]

This approach uniquely enables direct detection of RNA modifications including N6-methyladenosine (m6A) alongside sequence information [6].

Visualization of Third-Generation Sequencing Workflows

PacBio SMRT Sequencing Technology

Third-Generation Sequencing Evolution

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Third-Generation Sequencing

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| SMRTbell Libraries | Template for PacBio sequencing; enables circular consensus | HiFi sequencing, structural variant detection |

| MAS-ISO-seq/Kinnex Kits | Transcript concatenation for higher throughput | Single-cell isoform sequencing, full-length RNA-seq |

| Direct RNA Sequencing Kits | Native RNA sequencing without cDNA conversion | RNA modification analysis, epitranscriptomics |

| High-Molecular-Weight DNA Kits | Preservation of long DNA fragments | Metagenomics, genome assembly, structural variants |

| Barcoded Adapters | Sample multiplexing in single runs | Multi-sample experiments, cost reduction |

| Polymerase Binding Kits | Preparation of sequencing complexes | PacBio SMRT sequencing efficiency |

| Sigmoidin B | Sigmoidin B|5-Lipoxygenase Inhibitor|CAS 87746-47-2 | Sigmoidin B is a selective 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) inhibitor with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Silydianin | Silydianin, CAS:29782-68-1, MF:C25H22O10, MW:482.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Third-generation sequencing has unequivocally evolved from its initial high-error state to become a high-fidelity technology that competes directly with short-read sequencing in accuracy while offering substantial advantages in resolving power. PacBio's HiFi sequencing now delivers >99.9% accuracy with read lengths of 10-25 kb, while Nanopore technologies continue to improve in both accuracy and read length capabilities. The choice between short-read and modern long-read sequencing now depends primarily on the specific research question rather than fundamental accuracy concerns. For applications requiring resolution of complex genomic regions, characterization of structural variants, detection of base modifications, or comprehensive transcript isoform analysis, third-generation sequencing offers unparalleled capabilities that continue to expand the frontiers of genomic research.

Strategic Application in Research: Choosing the Right Tool for Your Biological Question

For researchers and drug development professionals investigating gene expression profiles and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), short-read RNA sequencing has established itself as the cornerstone technology. Platforms like Illumina, Ion Torrent, and Element Biosciences generate sequences spanning tens to hundreds of base pairs, offering an unmatched combination of high accuracy, cost-effectiveness, and scalability [30]. While long-read technologies from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore Technologies excel at resolving complex isoform structures, the domain of high-throughput gene expression and SNP analysis remains powerfully addressed by short-read methodologies [6] [10]. This guide objectively compares the performance of short-read and long-read RNA sequencing, providing supporting experimental data to illustrate why short-read platforms continue to be the default choice for large-scale transcriptomic studies in drug discovery and basic research.

Technology Comparison: How Short-Reads and Long-Reads Measure Up

Core Technical Characteristics

The fundamental differences in technology architecture between short-read and long-read platforms create a natural division in their optimal applications.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Short-Read and Long-Read RNA-Sequencing Technologies

| Feature | Short-Read cDNA-Seq | Long-Read cDNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Representative Platforms | Illumina, Ion Torrent, Element Biosciences AVITI [10] | PacBio, Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) [30] |

| Typical Read Length | Tens to hundreds of base pairs [30] | Thousands to hundreds of thousands of base pairs [10] |

| Key Strengths | Very high throughput, high accuracy (Q40+), cost-effective, scalable, well-understood bias and error profiles [30] [10] | Captures full-length transcripts, simplifies isoform discovery and fusion transcript detection [30] |

| Primary Limitations | Limited direct isoform detection, introduction of amplification biases [30] | Low to medium throughput, higher cost per sample, more complex data processing [30] |

Performance in Gene Expression and SNP Detection

Recent comparative studies quantify the performance gap in core applications. Short-read sequencing provides higher sequencing depth, which is critical for confidently detecting subtle gene expression changes and low-frequency SNPs [4]. In a 2025 study that sequenced the same 10x Genomics 3' cDNA using both Illumina and PacBio platforms, short-reads demonstrated a superior ability to recover more unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) per cell, a key metric for quantitative single-cell gene expression analysis [4].

Long-read sequencing, while transformative for isoform resolution, has not surpassed short-reads for pure gene-level quantification. The SG-NEx (Singapore Nanopore Expression) project, a comprehensive benchmark published in Nature Methods in 2025, found that while long-read protocols can robustly estimate gene expression, the massive throughput of short-read data makes it exceptionally reliable for this purpose [6]. For SNP detection, the high per-base accuracy of short-reads (often exceeding Q40 on modern platforms like the Element Biosciences AVITI System) is a decisive advantage for identifying single-nucleotide variants with high confidence [10].

Experimental Evidence: A Head-to-Head Comparison

Methodology of a Paired-Study

To ensure a fair comparison, researchers have designed experiments that sequence the same cDNA library with both short- and long-read technologies.

- Sample Preparation: A typical protocol begins with the conversion of RNA to cDNA, tagged with cell barcodes and UMIs. For example, one study used the 10x Genomics Chromium Single Cell 3' Reagent Kit (v3.1 Chemistry Dual Index) on patient-derived organoid cells [4].

- Library Splitting: The same pool of amplified, full-length cDNA is then split for two separate library preparations.

- Illumina (Short-Read) Library: The cDNA is enzymatically sheared to a target size of 200-300 bp. Following end repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation, a sample index PCR is performed. Sequencing is done on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 to achieve a high depth of ~300,000 reads per cell [4].

- PacBio (Long-Read) Library: The same cDNA is used for single-cell MAS-ISO-seq (Multiplexed Array Isoform Sequencing) library preparation. This involves a PCR step to remove template-switching oligo (TSO) artefacts, followed by directional assembly of cDNA segments into long concatenated arrays (10-15 kb) for efficient sequencing on a PacBio Sequel IIe system [4].

- Data Analysis: Reads are demultiplexed, aligned to the reference genome, and mapped to genes. For the comparison, molecules are matched by their cell barcode and UMI to enable a per-molecule cross-comparison [4].

Key Quantitative Findings from Direct Comparisons

This paired experimental design yields clear, data-driven results.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data from a Paired Sequencing Study [4]

| Performance Metric | Illumina Short-Reads | PacBio Long-Reads | Implication for Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Depth | High (Target: ~300,000 reads/cell) | Lower (~2 million reads total per SMRT cell) | Short-reads offer greater depth for statistical power in DGE and SNP calling. |

| UMIs Recovered per Cell | Higher | Lower | Enables more precise quantification of transcript molecules in single-cell studies. |

| Transcript Length Bias | Recovered fewer transcripts <500 bp | Retained transcripts shorter than 500 bp | Long-reads can profile very short transcripts missed by standard short-read protocols. |

| Handling of Artefacts | Standard filtering | Stringent filtering of TSO-contaminated cDNA | Long-read library prep can remove specific artefacts, potentially purifying the data. |

| Gene Count Correlation | High correlation between methods | Correlation reduced after filtering long-read artefacts | Highlights that platform-specific processing impacts final gene expression matrices. |

The overarching finding is that both methods are highly comparable and recover a large proportion of cells and transcripts [4]. However, the higher throughput and UMI recovery of short-read sequencing make it particularly suited for studies where quantifying the expression levels of thousands of genes across many samples is the primary goal.

The Researcher's Toolkit for Short-Read RNA-Seq

Successful gene expression and SNP detection studies rely on a suite of trusted reagents and methodologies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Short-Read RNA-Seq

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Considerations for Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(A) Capture Beads | Enriches for polyadenylated mRNA by hybridization to oligo(dT) probes. | Not suitable for degraded RNA or non-polyA RNAs (e.g., some lncRNAs) [31]. |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Reduces the ~80% of cellular RNA that is ribosomal, increasing informative reads. | More cost-effective for transcriptome coverage; assess off-target effects on genes of interest [32]. |

| Stranded Library Prep Kits | Preserves the original orientation of the transcript during cDNA synthesis. | Critical for identifying overlapping genes, novel RNAs, and accurate isoform assignment [32]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random sequences added to each molecule pre-amplification to correct for PCR bias. | Enables precise digital counting of transcripts, essential for single-cell RNA-seq [4]. |

| Size Selection Beads | Performs a solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) to select for a specific cDNA fragment size. | Standard post-amplification clean-up and double-sided size selection are common in Illumina protocols [4]. |

| Sinapaldehyde | Sinapaldehyde, CAS:4206-58-0, MF:C11H12O4, MW:208.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sinapinic acid | Sinapic Acid|High-Purity Reagent for Research |

Decision Workflows and Experimental Design

The choice between sequencing technologies is a fundamental step in experimental design. The following workflow diagram outlines the key decision points based on the primary research goal.

In the context of a broader comparison of RNA sequencing technologies, the evidence confirms that short-read sequencing remains the dominant force for high-throughput gene expression analysis and SNP detection. Its unparalleled throughput, high accuracy, and cost-efficiency make it the practical and powerful choice for transcriptomic studies in drug discovery, biomarker identification, and population-scale genomics [4] [30] [34]. While long-read sequencing opens up transformative possibilities for understanding transcriptome complexity, the quantitative strengths of short-reads ensure their continued central role in the molecular biologist's toolkit for years to come.

Long-read sequencing technologies have emerged as transformative tools for transcriptomics, enabling the direct observation of full-length RNA molecules. This capability is proving critical for discovering novel transcript isoforms and unraveling the complexity of gene regulation in health and disease. While short-read sequencing has been the workhorse for gene-level expression analysis, its limitations in resolving complete RNA structures have become increasingly apparent. This guide objectively compares the performance of long-read and short-read RNA sequencing technologies, supported by recent experimental data that highlight the unique advantages of long-read approaches for isoform-level analysis.

RNA sequencing has revolutionized how scientists study gene expression, providing an unbiased approach to gene detection and quantification [2]. For years, short-read sequencing has been the gold standard, offering high-throughput and cost-effective gene expression profiling [4]. However, a significant limitation persists: short reads (typically 100-200 base pairs) must be computationally assembled to approximate full transcripts, introducing ambiguity when resolving complex splicing patterns or distinguishing highly similar isoforms [35]. Long-read sequencing technologies from Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) directly address this limitation by sequencing full-length cDNA or RNA molecules in single reads, preserving exon connectivity and enabling direct observation of transcript structures [36] [2]. This capability is particularly valuable for understanding complex biological systems where alternative splicing generates multiple protein isoforms with distinct functions from a single gene.

Technical Comparison: Long-Read vs. Short-Read Sequencing

The fundamental differences between short-read and long-read technologies create distinct advantages and limitations for transcriptome analysis.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of RNA Sequencing Approaches

| Feature | Short-Read Sequencing | Long-Read Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Read Length | 100-200 bp | 1,000 - 20,000+ bp |

| Isoform Resolution | Indirect inference through assembly | Direct observation of full-length isoforms |

| Primary Applications | Gene expression quantification, differential expression | Isoform discovery, alternative splicing analysis, fusion detection |

| Splice Junction Mapping | Ambiguous for complex genes | Precise determination of exon connectivity |

| Throughput | Very high | Moderate to high (increasing with newer platforms) |

| Error Profile | Low random errors (~0.1%) | Higher single-pass error rates, mitigated by circular consensus sequencing (HiFi) |

| Identification of Novel Features | Limited by read length | Comprehensive discovery of novel isoforms, exons, and gene fusions |

Key Advantages of Long-Read Sequencing

- Full-Length Transcript Coverage: Long reads can capture complete transcripts from 5' to 3' end in a single read, providing unambiguous isoform information [2] [35].

- Discovery of Novel Isoforms: Multiple studies have demonstrated long-read technologies identify tens of thousands of previously unannotated isoforms. Research on human whole blood identified approximately 90,000 novel isoforms using PacBio long-read RNA-seq [37].

- Resolution of Complex Loci: Genes with numerous alternative exons or long repetitive regions, which are challenging for short-read assembly, can be fully characterized with long reads [38].

- Phasing Capability: Long reads preserve haplotype information, enabling allele-specific expression analysis of isoforms [2].

Experimental Evidence: Performance Benchmarks

Recent large-scale benchmarking studies and targeted investigations have quantitatively compared the performance of long-read and short-read technologies for transcriptome analysis.

The LRGASP Consortium Benchmark

The Long-read RNA-Seq Genome Annotation Assessment Project (LRGASP) Consortium conducted a systematic evaluation of long-read RNA-seq methods for transcript identification and quantification [39]. This comprehensive effort generated over 427 million long-read sequences from human, mouse, and manatee samples using multiple protocols and sequencing platforms.

Table 2: LRGASP Performance Metrics for Transcript Detection

| Metric | cDNA-PacBio | cDNA-ONT | R2C2-ONT | CapTrap-PacBio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Read Length | Longest distributions | Moderate | Longest distributions | Moderate |

| Sequence Quality | High | Lower | High | High |

| Throughput (reads) | Moderate | ~10x higher than other methods | Moderate | Moderate |

| FSM Detection | High with Bambu, IsoQuant, FLAIR | Variable across tools | Not specified | Not specified |

| Novel Transcript Support | High full support for novel transcripts | Lower support for novel transcripts | Not specified | Not specified |

The consortium found that libraries with longer, more accurate sequences (such as cDNA-PacBio) produced more accurate transcripts than those with increased read depth, while greater read depth improved quantification accuracy [39]. For well-annotated genomes, tools based on reference sequences (including Bambu, FLAIR, FLAMES, and IsoQuant) demonstrated the best performance in detecting known transcripts with high percentages of full splice matches.

Direct Platform Comparison Studies

A focused study comparing single-cell long-read and short-read sequencing of the same 10x Genomics complementary DNA (cDNA) libraries found that both methods recovered a large proportion of cells and transcripts with highly comparable results [4]. However, platform-dependent cDNA library processing introduced specific biases:

- Short-read sequencing provided higher sequencing depth

- Long-read sequencing (PacBio MAS-ISO-seq) retained transcripts shorter than 500 bp and enabled removal of degraded cDNA contaminated by template switching oligos

- Filtering of artifacts identifiable only from full-length transcripts reduced gene count correlation between the two methods

The Singapore Nanopore Expression (SG-NEx) project provided additional insights through a systematic benchmark of Nanopore long-read RNA sequencing for transcript-level analysis in human cell lines [6]. This comprehensive resource compared five RNA-sequencing protocols across seven human cell lines and reported that:

- PCR-amplified cDNA sequencing generated the highest throughput among long-read protocols

- PacBio IsoSeq generated the longest reads on average

- Long-read protocols showed higher coverage at the 5' and 3' ends of transcripts compared to short-read RNA-seq

- Gene expression estimates from Nanopore long-read RNA-seq data showed low estimation error and high correlation with expected spike-in concentrations

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To illustrate the practical application of long-read sequencing for isoform discovery, we detail two key methodologies from recent studies.

Protocol 1: MAS-ISO-seq for Single-Cell Isoform Sequencing

The MAS-ISO-seq (Multiplexed Array isoform sequencing) method, now relabeled as Kinnex full-length RNA sequencing, was used to profile patient-derived clear cell renal cell carcinoma organoids [4].

Library Preparation Workflow:

- cDNA Synthesis: Full-length cDNA was generated using the 10x Genomics Chromium Single Cell 3' Reagent Kits (v3.1 Chemistry Dual Index).

- TSO Artefact Removal: Template-switching oligonucleotide (TSO) priming artefacts generated during cDNA synthesis were removed using PCR with a modified primer (MAS capture primer Fwd) to incorporate a biotin tag into desired cDNA products, followed by capture with streptavidin-coated MAS beads.

- Segment Assembly: Purified cDNA was processed with programmable segmentation adapter sequences in 16 parallel PCR reactions per sample, followed by directional assembly of amplified cDNA segments into linear arrays of 10-15 kb.

- Library Construction: MAS arrays were DNA damage repaired and nuclease treated to produce final single-cell MAS-ISO-seq libraries.

- Quality Control: Library quantity and quality were measured by Qubit 1X dsDNA High Sensitivity Kit and pulse-field capillary electrophoresis system Femto Pulse.

- Sequencing: Libraries were sequenced on PacBio Sequel IIe systems using 3.2 binding chemistry on 8M SMRT cells.

This protocol demonstrated the ability to retain transcripts shorter than 500 bp and remove a large proportion of truncated cDNA contaminated by TSO artefacts [4].

Protocol 2: Nanopore Amplicon Sequencing for Neuropsychiatric Risk Genes

A specialized approach for deeply profiling the RNA isoform repertoire of 31 high-confidence neuropsychiatric disorder risk genes in human brain utilized nanopore long-read amplicon sequencing [38].

Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Collection: Seven regions of post-mortem human brain were collected from five control individuals, encompassing transcriptionally divergent regions and those implicated in mental health disorders.

- Amplicon Design: Primers were designed to cover the full coding region of target genes, running from the first to the last exon where possible.

- Multiple Primer Strategy: For genes with alternative transcriptional initiation and termination exons, multiple primer sets were employed to profile as many potential alternative isoforms as possible.

- Sequencing: Amplified products were sequenced using Oxford Nanopore Technologies.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: The custom pipeline IsoLamp was developed specifically for isoform discovery from amplicon sequencing data, demonstrating superior performance in benchmarking studies compared to existing tools.

This approach identified 363 novel isoforms and 28 novel exons in neuropsychiatric risk genes, with genes such as ATG13 and GATAD2A showing most expression from previously undiscovered isoforms [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful long-read transcriptomics requires specialized reagents and computational tools. The following table details essential solutions for conducting long-read RNA sequencing studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Long-Read Transcriptomics

| Category | Specific Products/Tools | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Library Prep Kits | PacBio Iso-Seq Express 2.0, ONT PCR-cDNA Kit | Convert RNA to sequencing-ready libraries with optimized protocols for full-length transcript capture |

| Spike-In Controls | SIRV Sets, ERCC RNA Spike-In Mixes | Assess technical performance, quantify detection limits, and normalize across experiments |

| Quality Control | Agilent 4200 TapeStation, Qubit dsDNA HS Assay | Evaluate RNA integrity, cDNA quality, and final library quantification before sequencing |

| Sequencing Platforms | PacBio Revio/Sequel IIe, ONT PromethION/P2 Solo | Generate long-read data with platform-specific advantages in read length and accuracy |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | IsoLamp, Bambu, FLAIR, IsoQuant, TALON | Process raw data, discover novel isoforms, and quantify transcript expression |

| Reference Annotations | GENCODE, RefSeq, CHM13 T2T | Provide baseline transcript models for comparison and novel isoform classification |

| Validation Tools | SQANTI3, Isoseq v4.0, Pigeon | Perform quality control of long-read defined transcriptomes and classify full-length isoforms |

| Solanesol | Solanesol|High-Purity Natural Product for Research | High-purity Solanesol for RUO. Explore its applications in pharmaceutical research, including antioxidant and anti-inflammatory studies. For Research Use Only. |

| Solanidine | Solanidine | Solanidine, a steroidal alkaloid for CYP2D6 activity research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |