The Complete Beginner's Guide to Bulk RNA-seq Data Analysis: From Raw Data to Biological Insights

This comprehensive guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete foundation in bulk RNA-seq data analysis.

The Complete Beginner's Guide to Bulk RNA-seq Data Analysis: From Raw Data to Biological Insights

Abstract

This comprehensive guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete foundation in bulk RNA-seq data analysis. Covering everything from core sequencing technologies and experimental design principles to hands-on bioinformatics workflows using modern tools like Salmon, DESeq2, and limma, this article bridges the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application. Readers will learn to implement robust analysis pipelines, perform critical quality control, identify differentially expressed genes, conduct functional enrichment analysis, and avoid common pitfalls. The guide emphasizes best practices for troubleshooting, data validation, and interpretation to ensure reliable, reproducible results that can drive discoveries in disease mechanisms, therapeutic development, and clinical research.

Understanding Bulk RNA-seq: Core Concepts and Experimental Design

What is Bulk RNA-seq? Analyzing transcriptomes from cell populations.

Bulk RNA sequencing (Bulk RNA-seq) is a foundational technique in molecular biology used for the transcriptomic analysis of pooled cell populations, tissue sections, or biopsies [1]. This method measures the average expression level of individual genes across hundreds to millions of input cells, providing a global overview of gene expression differences between samples [1] [2]. By capturing the collective RNA from all cells in a sample, bulk RNA-seq offers powerful insights into the overall transcriptional state, making it invaluable for comparative studies between conditions, such as healthy versus diseased tissues, or treated versus untreated samples [2] [3].

As a highly sensitive and accurate tool for measuring expression across the transcriptome, bulk RNA-seq provides scientists with visibility into previously undetected changes occurring in disease states, in response to therapeutics, and under different environmental conditions [4]. The technique allows researchers to detect both known and novel features in a single assay, enabling the identification of transcript isoforms, gene fusions, and single nucleotide variants without the limitation of prior knowledge [4]. Despite the recent emergence of single-cell technologies, bulk RNA-seq remains a widely used method due to its cost-effectiveness, established analytical frameworks, and ability to provide robust average expression measurements for population-level analyses [2] [5].

Table 1: Key Comparisons of RNA Sequencing Technologies

| Aspect | Single-cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) | Bulk RNA Sequencing | Spatial Transcriptome Sequencing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Sequencing of single cells to obtain information about their transcriptome [2] | Analysis of gene expression in tissues and cell populations [2] | Simultaneously examines gene expression and spatial location information of cells [2] |

| Sample Processing | Isolation, lysis, and amplification of individual cells [2] | Direct RNA extraction and amplification of tissues and cell populations [2] | Sections or fixation according to sample needs [2] |

| Experimental Costs | Higher [2] | Relatively low [2] | Higher [2] |

| Primary Application | Analyzing individual cell phenotypes, cell developmental trajectories [2] | Analyzing overall gene expression of tissues and cell populations to study gene function and physiological mechanisms [2] | Analyzing spatial structure of different cell types in tissues, cellular interactions [2] |

The Bulk RNA-seq Workflow: From Sample to Sequence

The bulk RNA-seq workflow encompasses a series of standardized steps to transform biological samples into interpretable gene expression data. A well-executed experimental design forms the foundation of this process, requiring careful planning of sample groups, proper controls, and sufficient replicates to ensure results are both statistically sound and biologically relevant [6]. During sample preparation, RNA is extracted from samples using methods like column-based kits or TRIzol reagents, with rigorous quality assessment using tools such as Bioanalyzer or TapeStation to ensure RNA integrity before proceeding to library preparation [1] [5].

The construction of a sequencing library involves multiple critical steps that prepare the RNA for high-throughput sequencing. Ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which constitutes over 80% of total RNA, is typically removed through ribo-depletion or polyA-selection that enriches for messenger RNA (mRNA) [3]. The remaining RNA undergoes reverse transcription to create more stable complementary DNA (cDNA), followed by fragmentation into smaller pieces [5]. Adapter ligation adds short DNA sequences to both ends of the fragments, enabling binding to the sequencing platform and sample identification through barcoding in multiplexed protocols [1] [5]. Finally, amplification via PCR ensures sufficient material is available for sequencing [5].

The prepared libraries are loaded onto next-generation sequencing platforms, such as those from Illumina, which generate millions of short reads representing the original RNA fragments [5] [4]. The resulting data, typically in the form of FASTQ files, contain both the RNA sequences and quality scores that are essential for subsequent bioinformatic analysis [5]. Throughout this workflow, consistency in handling and processing is paramount, as small errors during library preparation can lead to biased or incomplete results [5].

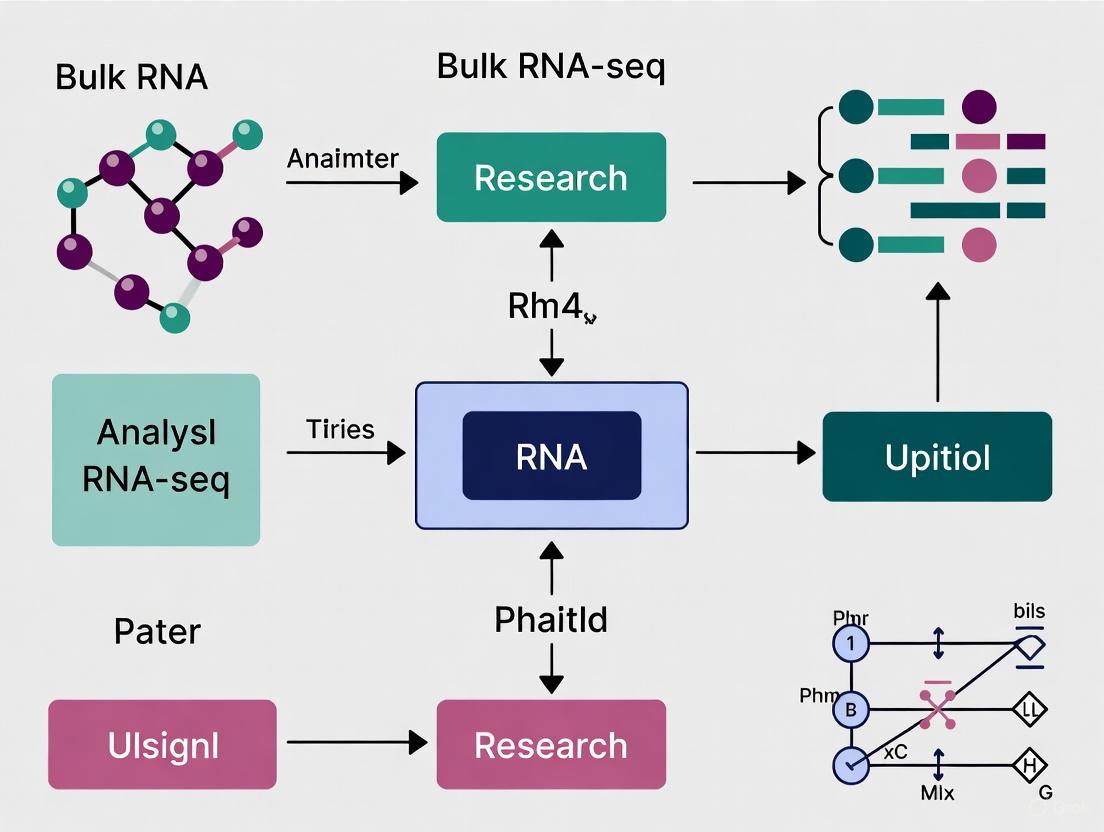

Diagram 1: Bulk RNA-seq Experimental Workflow

Bioinformatics Analysis: From Raw Data to Biological Insights

Once sequencing is complete, the raw data undergoes comprehensive bioinformatic processing to extract meaningful biological insights. This computational workflow involves multiple steps that transform raw sequencing reads into interpretable gene expression measurements.

Quality Control and Read Alignment

The initial quality control (QC) step is crucial for verifying data integrity. Tools like FastQC evaluate read quality, detect adapter contamination, and identify overrepresented sequences [5]. Following quality assessment, data cleaning is performed using tools such as Trimmomatic or Cutadapt to trim low-quality bases and remove adapter sequences [5] [7]. This cleaning process establishes a foundation for accurate downstream analysis.

Read mapping aligns the cleaned sequencing reads to a reference genome or transcriptome, identifying the genomic origin of each RNA fragment. Splice-aware aligners like STAR are commonly used for this purpose, as they can accommodate alignment gaps caused by introns [8] [9]. For organisms without a reference genome, de novo assembly tools like Trinity can reconstruct the transcriptome from scratch [5]. Accurate alignment is essential, as errors at this stage can propagate through subsequent analyses.

Expression Quantification and Normalization

Following alignment, expression quantification measures the number of reads aligning to each gene using tools such as featureCounts or HTSeq-count [5] [9]. This process generates a gene expression matrix where rows represent genes and columns represent samples, forming the foundation for all subsequent analyses [5].

Normalization adjusts raw read counts to account for technical variations between samples, such as differences in sequencing depth or library size [5]. Common normalization methods include TPM (Transcripts Per Million), RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads), and statistical methods implemented in packages like DESeq2 [5] [9]. Proper normalization ensures valid comparisons of expression levels across samples.

Table 2: Key Bioinformatics Tools for Bulk RNA-seq Analysis

| Analysis Step | Commonly Used Tools | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Quality Control | FastQC, Trimmomatic, Cutadapt, fastp [5] [7] | Assess read quality, remove adapter sequences, trim low-quality bases [5] |

| Read Alignment | STAR, HISAT2, Bowtie2 [8] [5] | Map sequencing reads to reference genome or transcriptome [8] [5] |

| Expression Quantification | featureCounts, HTSeq-count, Salmon, kallisto [8] [5] [9] | Count reads mapped to each gene/transcript [5] [9] |

| Differential Expression | DESeq2, limma, edgeR [8] [10] [9] | Identify statistically significant expression changes between conditions [10] [9] |

Differential Expression Analysis and Interpretation

Differential expression (DE) analysis represents a primary objective of most bulk RNA-seq studies, aiming to identify genes that show statistically significant expression differences between experimental conditions [8] [5]. This analysis employs specialized statistical methods designed to handle the unique characteristics of RNA-seq count data while accounting for biological variability and technical noise.

Statistical Frameworks for DE Analysis

The negative binomial distribution has emerged as the standard model for RNA-seq count data, as it effectively handles over-dispersion commonly observed in sequencing experiments [9]. Widely used packages like DESeq2 and edgeR implement this distribution in their generalized linear models (GLMs) to test for differential expression [9]. An alternative approach is provided by limma, which uses a linear modeling framework with precision weights to analyze RNA-seq data [8]. These tools typically generate results including log2 fold-change values, statistical test results (p-values), and multiple testing corrected p-values (adjusted p-values or q-values) to control the false discovery rate (FDR) [10] [9].

The interpretation of DE results is facilitated by various visualization approaches. Volcano plots simultaneously display statistical significance versus magnitude of expression change, allowing researchers to quickly identify genes with both large fold-changes and high significance [10] [5]. Heatmaps visualize expression patterns across samples and can reveal co-expressed genes or sample clusters [5]. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) reduces the high-dimensionality of the expression data, enabling visualization of overall sample relationships and identification of batch effects or outliers [6] [10].

Functional Enrichment Analysis

Following the identification of differentially expressed genes, functional enrichment analysis helps decipher their biological significance by testing whether certain biological processes, pathways, or functional categories are overrepresented in the gene set [5]. Tools like DAVID (Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery) and GSEA (Gene Set Enrichment Analysis) can identify pathways, gene ontology terms, or other functional annotations associated with the differentially expressed genes [5]. This step moves the analysis beyond individual genes to broader biological interpretations, connecting expression changes to cellular mechanisms, metabolic pathways, or signaling cascades that may be perturbed between experimental conditions.

Diagram 2: Differential Expression Analysis Workflow

Advanced Applications and Integrative Approaches

Bulk RNA-seq serves as a versatile tool with diverse applications across biological research and drug development. In disease research, it enables the identification of molecular mechanisms by comparing gene expression between healthy and diseased tissues, facilitating the discovery of biomarkers and therapeutic targets [5]. For drug development, bulk RNA-seq reveals how cells respond to pharmacological treatments, helping to identify mechanisms of action and predictors of treatment response [5]. The technology also supports personalized medicine approaches by characterizing molecular subtypes of diseases that may respond differently to therapies [5].

More recently, integrative approaches that combine bulk RNA-seq with other technologies have enhanced our ability to extract biological insights. For example, in cancer research, bulk RNA-seq data can be deconvoluted using cell-type-specific signatures derived from single-cell RNA-seq to estimate the proportions of different cell populations within tumor samples [2]. Similarly, combining bulk RNA-seq with spatial transcriptomics allows researchers to connect gene expression patterns with tissue architecture, providing context for expression changes observed in bulk data [2].

A case study on triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) demonstrated the power of multi-scale RNA sequencing analysis, where bulk RNA-seq was integrated with single-cell and spatial transcriptomics to explore how homologous recombination defects (HRDs) influence the tumor microenvironment and response to immune checkpoint inhibitors [2]. This integrated approach revealed distinct tumor microenvironments in HRD samples, including altered immune cell infiltration and fibroblast composition, highlighting how bulk RNA-seq contributes to comprehensive molecular profiling in complex biological systems [2].

Successful bulk RNA-seq experiments require careful selection of reagents and resources throughout the workflow. The following table outlines key components essential for generating high-quality data.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Bulk RNA-seq

| Category | Item | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction | TRIzol Reagent, Column-based Kits [1] [5] | Isolate high-quality total RNA from cells or tissues while preserving RNA integrity [5] |

| Quality Assessment | Bioanalyzer, TapeStation, Qubit [1] [6] | Evaluate RNA quality, concentration, and integrity (RIN) to ensure sample suitability for sequencing [1] [5] |

| Library Preparation | Oligo(dT) Beads, rRNA Depletion Kits, Reverse Transcriptase, Adapters with Barcodes [1] [4] | Enrich for mRNA, convert RNA to cDNA, and add platform-specific adapters for multiplexing and sequencing [1] [5] |

| Sequencing | Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep, Illumina RNA Prep with Enrichment [4] | Prepare sequencing libraries with options for polyA selection, ribodepletion, or targeted enrichment [4] |

Bulk RNA-seq remains an indispensable technique in modern transcriptomics, providing a robust method for profiling gene expression across cell populations and tissues. While newer technologies like single-cell RNA-seq offer higher resolution, bulk RNA-seq continues to deliver valuable insights for comparative transcriptomics, biomarker discovery, and pathway analysis [2]. The comprehensive workflow from sample preparation through bioinformatic analysis has been refined over nearly two decades of use, making it a reliable and accessible approach for researchers [2] [5].

As sequencing technologies continue to evolve and computational methods become more sophisticated, bulk RNA-seq analysis is likely to see further improvements in accuracy, efficiency, and integration with other data modalities. The ongoing development of standardized processing pipelines, such as those implemented by the nf-core community and institutional cores, enhances reproducibility and accessibility for researchers without extensive bioinformatics backgrounds [8] [3]. By following established best practices in experimental design, sample processing, and computational analysis, researchers can continue to leverage bulk RNA-seq to address diverse biological questions and advance our understanding of gene regulation in health and disease.

The evolution of DNA sequencing technologies has fundamentally transformed biological research, enabling scientists to decode the language of life with ever-increasing speed, accuracy, and affordability. This technological progression has been particularly revolutionary for transcriptomic studies, including bulk RNA-seq, which relies on these platforms to generate comprehensive gene expression data. From its beginnings with Sanger sequencing in the 1970s, the field has advanced through next-generation sequencing (NGS) to the latest third-generation platforms, each generation offering distinct advantages and confronting unique challenges [11] [12]. For researchers embarking on bulk RNA-seq analysis, understanding this technological landscape is crucial for selecting appropriate methodologies, designing robust experiments, and accurately interpreting results.

The global market for DNA sequencing, predicted to grow from $15.7 billion in 2021 to $37.7 billion by 2026, reflects the expanding influence of these technologies [11]. This growth is propelled by rising applications in viral disease research, oncology, and personalized medicine. In bulk RNA-seq, the choice of sequencing platform directly impacts key parameters including read length, throughput, accuracy, and cost, thereby shaping every subsequent analytical decision [13] [5]. This guide provides a technical overview of sequencing technology evolution, framed within the practical context of bulk RNA-seq data analysis for beginner researchers.

Generations of Sequencing Technology

First-Generation: Sanger Sequencing

Developed in 1977, Sanger sequencing represents the first generation of DNA sequencing technology and remained the gold standard for decades [12] [5]. This method relies on the chain termination principle using dideoxynucleoside triphosphates (ddNTPs) that lack the 3'-hydroxyl group necessary for DNA strand elongation. When incorporated during DNA synthesis, these ddNTPs terminate the growing chain, producing DNA fragments of varying lengths that can be separated by capillary electrophoresis to determine the nucleotide sequence [12].

For contemporary researchers, Sanger sequencing maintains relevance for specific applications despite being largely superseded by NGS for large-scale projects. Its key advantages include long read lengths (500-1000 bases) and exceptionally high accuracy (Phred score > Q50, representing 99.999% accuracy) [12]. In RNA-seq workflows, Sanger sequencing is primarily employed for confirming specific variants identified through NGS, validating DNA constructs (such as plasmids), and sequencing PCR products where high certainty at defined loci is required [12].

Second-Generation: Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

The advent of NGS, also known as massively parallel sequencing (MPS), marked a revolutionary departure from Sanger technology by enabling the simultaneous sequencing of millions to billions of DNA fragments [11] [12]. This paradigm shift dramatically reduced the cost per base while exponentially increasing data output. The core principle unifying NGS technologies is sequencing by synthesis, where fluorescently labeled, reversible terminators are incorporated one base at a time across millions of clustered DNA fragments on a solid surface [12]. After each incorporation cycle, the fluorescent signal is imaged, the terminator is cleaved, and the process repeats [12].

NGS platforms can be categorized based on their DNA amplification techniques:

- Emulsion PCR: Used by Ion Torrent and GenapSys platforms

- Bridge amplification: Employed by Illumina platforms

- DNA nanoball generation: Utilized by BGI Group [11]

Illumina currently dominates the NGS market, having driven sequencing costs from billions of dollars during the Human Genome Project to less than $1,000 per whole genome today [11]. Thermo Fisher Scientific represents another major player with its Ion Torrent series [11]. NGS accounts for approximately 58.6% of the DNA sequencing market and has become the cornerstone technology for bulk RNA-seq due to its high throughput, excellent accuracy, and cost-effectiveness for transcriptome-wide analyses [11] [5].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Sequencing Technology Generations

| Feature | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Third-Generation Sequencing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Method | Chain termination with ddNTPs | Massively parallel sequencing by synthesis | Single-molecule real-time sequencing |

| Read Length | 500-1000 bp (long contiguous reads) | 50-300 bp (short reads) | >15,000 bp (long reads) |

| Throughput | Low to medium | Extremely high | High |

| Accuracy | Very high (>Q50) | High (improved by high coverage) | Variable (improving with new chemistries) |

| Primary RNA-seq Role | Targeted confirmation | Whole transcriptome analysis, differential expression | Full-length isoform detection, structural variation |

| Cost per Base | High | Low | Moderate to high |

Third-Generation Sequencing

Third-generation sequencing technologies emerged to address a fundamental limitation of NGS: short read lengths. Platforms such as Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) enable the sequencing of single DNA molecules in real time, producing significantly longer reads that can span complex genomic regions and full-length transcripts [11] [14]. PacBio employs Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing, which detects nucleotide incorporations through fluorescent signals in zero-mode waveguides, while ONT technology measures changes in electrical current as DNA strands pass through protein nanopores [11] [14].

Recent advances have substantially improved the accuracy of third-generation sequencing. PacBio's HiFi reads now achieve >99.9% accuracy with reads over 15 kb, making them ideal for applications requiring high precision in transcript isoform discrimination [11]. ONT's PromethION systems can generate up to 200 Gb per flow cell with improving basecalling algorithms like Dorado, pushing the technology toward population-scale genomics applications [11]. For bulk RNA-seq, these platforms excel at resolving structural variants, alternative splicing events, haplotyping, and methylation detection without requiring PCR amplification [11].

Impact on Bulk RNA-Seq Analysis

Practical Implications for Experimental Design

The choice of sequencing technology profoundly influences bulk RNA-seq experimental design and achievable outcomes. NGS remains the preferred choice for most differential gene expression studies due to its proven cost-effectiveness, high accuracy, and established bioinformatics pipelines [13] [5]. The massive parallel processing capability of NGS enables sensitive detection of low-abundance transcripts across multiple samples simultaneously, which is essential for robust statistical analysis in expression studies [5].

Third-generation sequencing offers compelling advantages for specific RNA-seq applications where long reads provide decisive benefits. These include comprehensive transcriptome characterization without assembly, direct detection of base modifications (epitranscriptomics), and resolution of complex gene families with high sequence similarity [11]. However, these platforms typically require more input RNA and involve higher per-sample costs than NGS, making them less practical for large-scale differential expression studies with multiple replicates [5].

Table 2: Sequencing Platform Selection Guide for Bulk RNA-Seq Applications

| Research Goal | Recommended Technology | Rationale | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Gene Expression | NGS (Illumina) | Cost-effective for multiple replicates; high accuracy for quantitation | 15-20 million reads per sample typically sufficient |

| Alternative Splicing Analysis | Third-generation (PacBio HiFi) | Long reads capture full-length transcripts | Higher cost; may require deeper sequencing |

| Novel Transcript Discovery | Third-generation (ONT or PacBio) | Identifies previously unannotated isoforms without assembly | Computational resources for long-read data analysis |

| Validation Studies | Sanger sequencing | Gold-standard accuracy for confirming specific variants | Low throughput; not for genome-wide studies |

| Clinical Diagnostics | NGS (targeted panels) | Balanced throughput, accuracy, and cost | Rapid turnaround with automated systems like Ion Torrent Genexus |

The Bulk RNA-Seq Workflow

The standard bulk RNA-seq workflow consists of sequential steps that transform biological samples into interpretable gene expression data [13] [5]:

Sample Preparation and Library Construction: RNA is extracted from tissue or cell populations, assessed for quality (using RIN scores), and converted to sequencing libraries through reverse transcription, fragmentation, adapter ligation, and amplification [5].

Sequencing: Libraries are loaded onto platforms such as Illumina, which generate millions of short reads (typically 75-150 bp) in a high-throughput manner [13].

Bioinformatics Analysis: Raw sequencing data (in FASTQ format) undergoes quality control (FastQC), read trimming (Trimmomatic, fastp), alignment to a reference genome (STAR, HISAT2), gene expression quantification (featureCounts), and differential expression analysis (DESeq2, edgeR) [13] [7] [5].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in bulk RNA-seq data analysis:

Essential Tools and Reagents for RNA-Seq

Successful bulk RNA-seq experiments require both laboratory reagents for sample preparation and computational tools for data analysis. The following table outlines key components of the researcher's toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools for Bulk RNA-Seq

| Category | Item | Function in RNA-Seq Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | RNA Stabilization Reagents (e.g., TRIzol) | Preserve RNA integrity during sample collection and storage |

| Poly(A) Selection or rRNA Depletion Kits | Enrich for mRNA by removing ribosomal RNA | |

| Reverse Transcriptase Enzymes | Convert RNA to more stable cDNA for sequencing | |

| Library Preparation Kits (e.g., NEBNext) | Fragment DNA, add platform-specific adapters, and amplify | |

| Sequencing Consumables | Flow Cells (Illumina) | Solid surface for clustered amplification and sequencing |

| Sequencing Chemistry Kits | Provide enzymes and nucleotides for sequencing-by-synthesis | |

| Computational Tools | FastQC | Assesses raw read quality before analysis |

| Trimmomatic/fastp | Removes adapter sequences and low-quality bases | |

| STAR/HISAT2 | Aligns RNA-seq reads to reference genome | |

| featureCounts/HTSeq | Quantifies reads overlapping genomic features | |

| DESeq2/edgeR | Identifies statistically significant differentially expressed genes | |

| R/Bioconductor | Primary environment for statistical analysis and visualization |

The DNA sequencing landscape continues to evolve rapidly, with new technologies promising to further transform bulk RNA-seq applications. Recent developments include Roche's Sequencing by Expansion (SBX) technology, announced in early 2025, which introduces novel chemistry that amplifies DNA into "Xpandomers" for rapid base-calling [11]. Illumina's 5-base chemistry enables simultaneous detection of standard bases and methylation states, potentially revolutionizing epigenetic analysis in multi-omic workflows [11]. Emerging platforms like Element Biosciences' AVITI System and MGI Tech's DNBSEQ platforms offer improved accuracy and cost-effectiveness, providing researchers with more options tailored to specific project needs [11].

For researchers conducting bulk RNA-seq analyses, understanding sequencing technology evolution is not merely historical context but practical knowledge that informs experimental design and interpretation. While NGS remains the workhorse for standard differential expression studies, third-generation platforms offer powerful alternatives for applications requiring long reads, and Sanger sequencing maintains its role for targeted validation. As sequencing technologies continue to advance, becoming faster, more accurate, and more accessible, they will undoubtedly unlock new possibilities for transcriptomic research and deepen our understanding of gene expression in health and disease. The future of bulk RNA-seq analysis lies in selecting the right technological tools for specific biological questions, leveraging the unique strengths of each sequencing platform to extract maximum insight from transcriptomic data.

Bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become a cornerstone technology in biomedical research, enabling comprehensive analysis of gene expression profiles across entire transcriptomes. This powerful technique provides researchers with the ability to decode complex cellular mechanisms by quantifying RNA transcripts present in populations of cells. The applications of bulk RNA-seq span from fundamental investigations of disease pathology to accelerating therapeutic development and advancing personalized treatment strategies. This technical guide explores the key methodologies and experimental protocols that make bulk RNA-seq an indispensable tool for modern biomedical research, providing a foundational resource for scientists and drug development professionals embarking on transcriptomic studies.

Bulk RNA-seq is a high-throughput sequencing technology that analyzes the transcriptome—the complete set of RNA transcripts in a biological sample consisting of pools of cells [8] [5]. Unlike single-cell approaches, bulk RNA-seq provides a population-average view of gene expression, making it particularly valuable for understanding systemic biological responses and identifying consistent molecular patterns across tissue samples or experimental conditions. The fundamental principle involves converting RNA populations to complementary DNA (cDNA) libraries, followed by next-generation sequencing (NGS) to generate millions of short reads that represent fragments of the original transcriptome [5] [15].

The typical workflow begins with careful experimental design and sample preparation, proceeds through library preparation and sequencing, and culminates in bioinformatic analysis of the resulting data [5] [15]. This process enables researchers to address diverse biological questions by quantifying expression levels across thousands of genes simultaneously. The decreasing costs of sequencing and the development of robust analytical pipelines have made bulk RNA-seq accessible to researchers across biomedical disciplines, transforming our ability to investigate gene regulation, cellular responses, and disease processes at unprecedented scale and resolution [6].

Table: Comparison of Sequencing Technologies for Transcriptomics

| Technology | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Best Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanger Sequencing | Chain-terminating nucleotides | High accuracy per read | Low throughput, slow processing | Validation studies, small-scale sequencing |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Massive parallel processing | High throughput, scalability, cost-effective | Short read lengths | Most bulk RNA-seq applications, gene expression profiling |

| Third-Generation Sequencing | Long-read technologies | Identifies complex RNA structures, alternative splicing | Higher costs, lower accuracy | Specialized applications requiring isoform resolution |

Applications in Disease Mechanism Research

Bulk RNA-seq plays a transformative role in elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying various diseases. By comparing transcriptomic profiles between healthy and diseased tissues, researchers can identify genes and pathways that are dysregulated in pathological conditions, providing crucial insights into disease initiation and progression [5]. For example, in cancer research, bulk RNA-seq analysis of tumor tissues versus normal adjacent tissues has revealed genes driving tumor growth, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance [5]. Similarly, in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's, transcriptomic studies have uncovered how disrupted gene activity contributes to disease processes [5].

The technology also enables the study of host-pathogen interactions in infectious diseases by examining how pathogens alter host gene expression [5]. This application has been particularly valuable during the COVID-19 pandemic, where RNA-seq has helped characterize the host response to SARS-CoV-2 infection and identify potential therapeutic targets. Furthermore, bulk RNA-seq can detect novel transcripts, splice variants, and fusion genes that may contribute to disease pathogenesis, expanding our understanding of molecular diversity in diseased states [15].

Experimental Protocol for Disease Mechanism Studies

Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Obtain tissue samples from both diseased and healthy control subjects, ensuring proper preservation of RNA integrity. Immediate stabilization using liquid nitrogen, dry-ice ethanol baths, or -80°C freezing is critical [16].

- Extract total RNA using column-based kits or TRIzol reagents, with careful attention to preventing RNase contamination [5].

- Assess RNA quality using Agilent TapeStation or Bioanalyzer to determine RNA Integrity Number (RIN). Aim for RIN values of 7-10 for high-quality samples [16].

- Quantify RNA concentration using Nanodrop spectrophotometry, ensuring 260/280 ratios of approximately 2.0 and 260/230 ratios of 2.0-2.2 [16].

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- For eukaryotic samples, perform either poly(A) selection to enrich for mRNA or ribosomal RNA depletion to capture both coding and non-coding transcripts [15].

- Convert RNA to cDNA using reverse transcription, followed by fragmentation, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification [5].

- Use strand-specific library preparation protocols (e.g., dUTP method) to preserve information about the transcribed strand, which is crucial for identifying antisense transcripts [15].

- Sequence libraries using Illumina platforms, aiming for 15-20 million reads per sample for standard gene expression studies, though deeper sequencing may be required for detecting low-abundance transcripts [13] [15].

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Perform quality control on raw sequencing reads using FastQC to assess base quality scores, adapter contamination, and GC content [13] [17].

- Trim low-quality bases and adapter sequences using tools like Trimmomatic or Cutadapt [13] [16].

- Align processed reads to a reference genome using splice-aware aligners such as STAR or HISAT2 [13] [16].

- Quantify gene-level counts using featureCounts or HTSeq, counting only uniquely mapped reads that fall within exonic regions [13].

- Identify differentially expressed genes between diseased and control samples using statistical methods in DESeq2 or edgeR [13] [9].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for bulk RNA-seq analysis in disease mechanism research

Applications in Drug Development

Bulk RNA-seq has become an integral component of modern drug development pipelines, accelerating therapeutic discovery and validation. In preclinical stages, transcriptomic profiling enables researchers to identify novel drug targets by pinpointing genes and pathways that are dysregulated in disease states [5]. By analyzing how cells respond to compound treatments, researchers can assess drug efficacy, understand mechanisms of action, and identify potential off-target effects [5]. This approach supports the transition from phenotypic screening to target-based drug development by providing comprehensive molecular signatures of drug response.

In toxicity assessment, bulk RNA-seq can reveal subtle changes in gene expression that predict adverse effects before they manifest clinically. The technology also plays a crucial role in biomarker discovery, identifying gene expression signatures that can stratify patient populations most likely to respond to specific therapies [5]. Furthermore, during clinical trials, transcriptomic analysis of patient samples helps validate drug mechanisms and identify resistance pathways, informing combination therapy strategies and guiding trial design.

Experimental Protocol for Drug Response Studies

Study Design Considerations:

- Include appropriate controls (vehicle-treated) and multiple dose concentrations to establish dose-response relationships.

- Incorporate time-course designs to capture dynamic transcriptional changes following drug exposure.

- Use sufficient biological replicates (typically n=3-5 per condition) to ensure statistical power for detecting subtle expression changes [15].

- Randomize sample processing and sequencing across multiple batches to minimize technical confounding [6].

Data Analysis Workflow:

- Process raw sequencing data through standard quality control and alignment pipelines as described in Section 2.1.

- Perform principal component analysis (PCA) to assess overall transcriptomic similarity between treatment groups and identify potential outliers [6] [9].

- Conduct differential expression analysis comparing drug-treated samples to controls, using appropriate multiple testing corrections (e.g., Benjamini-Hochberg FDR) [9].

- Apply gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) or similar pathway analysis methods to identify biological processes and pathways affected by drug treatment [17] [18].

- Develop gene expression signatures predictive of drug response using machine learning approaches.

Table: Key Analytical Tools for Drug Development Applications

| Analysis Type | Tool Options | Key Outputs | Interpretation in Drug Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Expression | DESeq2, edgeR, limma | Fold changes, p-values, FDR | Target engagement, efficacy biomarkers |

| Pathway Analysis | GSEA, DAVID, Reactome | Enriched pathways, gene sets | Mechanism of action, off-target effects |

| Time-course Analysis | DESeq2, maSigPro | Temporal expression patterns | Pharmacodynamics, response kinetics |

| Biomarker Discovery | Random Forest, SVM | Predictive signatures | Patient stratification, companion diagnostics |

Diagram 2: Bulk RNA-seq applications throughout the drug development pipeline

Applications in Personalized Medicine

Bulk RNA-seq enables personalized medicine approaches by generating molecular profiles that guide treatment selection for individual patients. In oncology, transcriptomic subtyping of tumors has revealed distinct molecular classifications with prognostic and therapeutic implications [5]. For example, breast cancer subtypes identified through gene expression profiling (luminal A, luminal B, HER2-enriched, basal-like) demonstrate different clinical outcomes and responses to targeted therapies. Similar molecular stratification approaches have been applied across cancer types, enabling more precise treatment matching.

Beyond oncology, bulk RNA-seq supports personalized medicine through expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) mapping, which identifies genetic variants that influence gene expression levels [15]. These analyses help interpret the functional consequences of disease-associated genetic variants identified through genome-wide association studies (GWAS), bridging the gap between genetic predisposition and molecular mechanisms. Additionally, transcriptomic profiling of immune cells in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases can identify patient subsets most likely to respond to specific immunomodulatory therapies.

Experimental Protocol for Personalized Medicine Applications

Patient Cohort Design:

- Recruit well-characterized patient cohorts with comprehensive clinical annotation, including treatment outcomes and follow-up data.

- Ensure appropriate sample sizes based on power calculations, considering expected effect sizes and patient population heterogeneity.

- Collect matched normal tissue when possible to control for germline genetic influences on gene expression.

- Implement strict quality control measures to maintain sample integrity throughout collection, processing, and storage.

Analytical Approaches for Clinical Translation:

- Perform unsupervised clustering (hierarchical clustering, k-means) to identify molecular subtypes based on gene expression patterns.

- Develop predictive classifiers using machine learning algorithms (e.g., random forests, support vector machines) trained on expression data and clinical outcomes.

- Conduct survival analysis (Cox proportional hazards models) to associate expression signatures with clinical outcomes.

- Validate identified signatures in independent patient cohorts to ensure robustness and generalizability.

- Establish clinically applicable assay formats (e.g., targeted RNA-seq panels, nanostring) for implementation in diagnostic settings.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Bulk RNA-seq Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations for Personalized Medicine |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization | RNAlater, PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes | Preserves RNA integrity at collection | Enables standardized collection in clinical settings |

| RNA Extraction Kits | QIAseq UPXome RNA Library Kit, PicoPure RNA isolation kit | Isolates high-quality RNA from limited samples | Compatible with small biopsy specimens |

| Library Preparation | SMARTer Stranded Total RNA-Seq Kit, Illumina TruSeq stranded mRNA kit | Converts RNA to sequenceable libraries | Maintains strand information for complex annotation |

| rRNA Depletion | QIAseq FastSelect, NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation | Enriches for mRNA or depletes rRNA | Captures both coding and non-coding transcripts |

| Quality Control | Agilent TapeStation, Bioanalyzer, Qubit | Assesses RNA quantity and quality | Critical for clinical grade assay validation |

Integrated Analysis and Interpretation

The true power of bulk RNA-seq in biomedical research emerges through integrated analysis approaches that combine transcriptomic data with other data types and biological knowledge. Multi-omics integration, combining RNA-seq with genomic, epigenomic, and proteomic data, provides a more comprehensive understanding of disease mechanisms and therapeutic responses [15]. For instance, integrating mutation data with expression profiles can reveal how specific genetic alterations dysregulate transcriptional networks, while combining chromatin accessibility data with expression patterns can elucidate regulatory mechanisms.

Functional interpretation of RNA-seq results typically involves gene set enrichment analysis to identify biological processes, pathways, and molecular functions that are overrepresented among differentially expressed genes [17] [18]. Tools such as DAVID, GSEA, and Reactome facilitate this biological contextualization, helping researchers move from lists of significant genes to coherent biological narratives. Visualization techniques including heatmaps, volcano plots, and pathway diagrams further enhance interpretation and communication of findings [13] [9].

Effective integration and interpretation require careful consideration of statistical issues, particularly multiple testing corrections when evaluating numerous pathways or gene sets. Additionally, researchers must remain alert to potential confounding factors such as batch effects, cell type composition differences, and technical artifacts that could misleadingly influence results [6]. Transparent reporting of analytical methods and parameters ensures reproducibility and enables proper evaluation of findings.

Bulk RNA-seq has firmly established itself as a foundational technology in biomedical research, providing critical insights into disease mechanisms, accelerating drug development, and advancing personalized medicine. The applications discussed in this guide demonstrate the versatility and power of this approach for addressing diverse biological and clinical questions. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve and analytical methods become more sophisticated, the resolution and scope of transcriptomic investigations will further expand.

For researchers embarking on bulk RNA-seq studies, attention to experimental design, rigorous quality control, and appropriate analytical strategies is paramount for generating robust, interpretable data. The protocols and methodologies outlined here provide a framework for conducting such investigations effectively. By leveraging these approaches and continuing to innovate in both wet-lab and computational methods, the biomedical research community can further unlock the potential of transcriptomic profiling to advance human health.

The power of bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) to profile gene expression across entire transcriptomes has made it an indispensable tool in biological research and drug development [6]. However, the technical complexity and multi-step nature of the process mean that the biological insights gained are profoundly influenced by the initial decisions made during experimental planning [7]. A well-constructed design establishes the foundation for a statistically robust and biologically meaningful analysis, while a flawed design can undermine even the most sophisticated computational approaches applied downstream. This guide details the critical first steps—defining clear objectives, implementing appropriate controls, and designing effective replication strategies—within the broader context of building a comprehensive thesis on bulk RNA-seq data analysis for beginner researchers.

Defining research objectives and hypotheses

The initial stage of any bulk RNA-seq experiment requires precise articulation of the biological question. A clearly defined objective determines every subsequent choice in the experimental design, from sample preparation to computational analysis.

Formulating the primary biological question

The research objective should be framed as a specific, testable hypothesis. Vague questions like "What genes are different?" provide insufficient guidance for designing a powerful experiment. Instead, hypotheses should be precise, such as: "Does Drug X, a known inhibitor of the NF-κB pathway, alter the expression of inflammatory genes in primary human airway smooth muscle cells within 18 hours of treatment?" [19]. This specificity directly informs the selection of model systems, treatment conditions, and time points.

Aligning objectives with analytical outcomes

Different biological questions lead to different analytical priorities and therefore different design considerations. The table below outlines how common research objectives align with analytical outcomes and their implications for experimental design.

Table 1: Aligning Research Objectives with Analytical Outcomes and Design Considerations

| Research Objective | Primary Analytical Outcome | Key Design Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Discovery of novel biomarkers | Identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between conditions | Sufficient biological replicates to power detection of subtle, reproducible expression changes [6]. |

| Validation of a targeted intervention | Confirmation of expected expression changes in a specific pathway | Inclusion of positive and negative controls to establish assay sensitivity and specificity. |

| Characterization of transcriptome dynamics | Analysis of co-regulated gene clusters and pathways over time/conditions | Controlled conditions and matched samples to minimize batch effects and isolate biological signal [6]. |

The cornerstone of reliability: Controls and replication

The accuracy and reproducibility of RNA-seq data hinge on careful experimental control and appropriate replication. These elements are non-negotiable for distinguishing true biological signal from technical noise and random biological variation.

Implementing effective controls

Controls are essential for verifying that the experimental system is functioning as expected and that observed changes are a result of the manipulated variable.

- Positive Controls: These demonstrate that the experiment can detect a known effect. For example, in a study of glucocorticoid response, one could include a sample treated with a well-characterized steroid like dexamethasone to confirm that known anti-inflammatory target genes are successfully detected as differentially expressed [19].

- Negative Controls: These establish a baseline in the absence of the experimental perturbation. For instance, untreated vehicle controls (e.g., cells treated with DMSO) are crucial for distinguishing the effect of a drug from non-specific effects of the delivery method.

Strategic replication to capture variation

Replication is the means by which scientists estimate variability, which is a prerequisite for statistical inference. In RNA-seq, different types of replication address different sources of variation.

- Biological Replicates: These are measurements taken from biologically distinct samples (e.g., cells from different individuals, cultures derived from different animals) [6]. They capture the natural variation within a population and are absolutely essential for making generalizable inferences about the biological condition under study. Statistical power to detect differential expression improves dramatically with increasing numbers of biological replicates [20].

- Technical Replicates: These are multiple measurements of the same biological sample (e.g., splitting an RNA sample for multiple library preparations or sequencing runs). They primarily help characterize and account for technical noise introduced during library preparation and sequencing. While useful for assessing protocol consistency, technical replication cannot substitute for biological replication [20] [6].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical sequence of decisions involved in planning a bulk RNA-seq experiment, from hypothesis formulation to final replication strategy.

Diagram 1: Workflow for designing a bulk RNA-seq experiment.

Power analysis and replication decisions

For researchers with a fixed budget, a critical design question is whether to increase the sequencing depth per sample or to increase the number of biological replicates. Multiple studies have quantitatively demonstrated that power to detect differential expression is gained more effectively through the use of biological replicates than through increased sequencing depth [20]. One study found that sequencing depth could be reduced significantly (e.g., to as low as 15% in some scenarios) without substantial impacts on false positive or true positive rates, provided an adequate number of biological replicates were used [20]. The following table summarizes a comparison of experimental design choices based on a simulation study.

Table 2: Impact of Experimental Design Choices on Power to Detect Differential Expression (Based on [20])

| Design Factor | Impact on Power to Detect DE | Key Finding from Simulation Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Biological Replicates | High positive impact | Increasing biological replication (e.g., from n=2 to n=5) provides the greatest gain in statistical power [20]. |

| Sequencing Depth | Lower positive impact (with diminishing returns) | Power can be maintained even with reduced sequencing depth when sufficient biological replicates are used [20]. |

| Number of Technical Replicates | Low impact for biological inference | Technical replication helps characterize technical noise but is a less efficient use of resources for increasing power compared to biological replication [20]. |

Practical workflow planning and material preparation

With the core design principles established, the next step is to plan the practical execution of the experiment, from sample preparation to data generation.

Minimizing batch effects

Batch effects are technical sources of variation that can confound biological results, arising from processing samples on different days, by different personnel, or across different sequencing lanes [6]. Proactive design is the most effective way to manage them.

- Randomization and Blocking: Distribute samples from all experimental conditions across different processing batches (e.g., days, library prep kits, sequencing lanes). If a perfect balance is not possible, the design should "block" on the known technical factor to account for it statistically during analysis [20] [6].

- Temporal Consistency: Process controls and experimental samples simultaneously whenever possible. Harvest biological material at the same time of day and perform RNA isolation and library preparation for all samples in a single batch to minimize technical variability [6].

The scientist's toolkit: Essential research reagents

A successful RNA-seq experiment relies on a suite of high-quality reagents and materials. The table below lists key resources and their functions.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for a Bulk RNA-seq Experiment

| Item / Reagent | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| High-Quality RNA Sample | The starting material; integrity (e.g., RIN > 7.0) is critical for generating a representative library [6]. |

| Poly(A) Selection or rRNA Depletion Kits | To enrich for messenger RNA (mRNA) from total RNA, removing abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA) [6]. |

| cDNA Library Prep Kit | Converts RNA into a sequencing-ready library, involving fragmentation, adapter ligation, and index/barcode incorporation [6] [8]. |

| Indexing Barcodes | Unique short DNA sequences ligated to each sample's fragments, enabling multiplexing by allowing pooled libraries to be computationally deconvoluted after sequencing [8] [20]. |

| Reference Genome Fasta File | The genomic sequence for the organism being studied, used for alignment and quantification (e.g., from ENSEMBL, GENCODE) [8] [19]. |

| Annotation File (GTF/GFF) | File containing genomic coordinates of known genes and transcripts, used to assign sequenced fragments to genomic features [8]. |

The following diagram maps these key materials onto a simplified overview of the bulk RNA-seq laboratory and computational workflow.

Diagram 2: Key stages of the bulk RNA-seq laboratory and computational workflow.

The journey of a bulk RNA-seq experiment is complex, but its success is determined at the very beginning. A rigorous design, built upon a precise hypothesis, a robust strategy for controls and replication, and a proactive plan to minimize batch effects, is not merely a preliminary step—it is the most critical phase of the research. By investing time in these foundational principles, researchers ensure that their data is capable of producing valid, reproducible, and biologically insightful results, thereby solidifying the integrity of their scientific conclusions.

For researchers embarking on bulk RNA-seq analysis, sample preparation and quality assessment form the critical foundation upon which all subsequent data rests. The quality of extracted RNA directly determines the reliability and interpretability of gene expression data, making rigorous quality control (QC) an indispensable first step in any sequencing workflow. Within this context, the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) has emerged as a standardized metric that provides an objective assessment of RNA quality, helping researchers determine whether their samples are suitable for downstream applications like RNA sequencing [21]. This guide provides a comprehensive technical overview of RNA quality assessment, focusing specifically on practical methodologies for sample preparation, RIN evaluation, and integration of these QC measures within a bulk RNA-seq framework designed for researchers new to the field.

Understanding RNA integrity number (RIN) and related metrics

The principle of RNA integrity assessment

RNA integrity assessment relies on the electrophoretic separation of RNA molecules to visualize and quantify the degradation state of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) subunits, which constitute the majority of total RNA in a cell. In intact, high-quality RNA, distinct peaks are visible for the 18S and 28S eukaryotic ribosomal RNAs (or 16S and 23S for prokaryotic samples), with a baseline that remains relatively flat between these markers. As RNA degrades, this profile shifts noticeably: the ribosomal peaks diminish while the baseline elevates due to the accumulation of RNA fragments of various sizes [21]. The RIN algorithm, developed by Agilent Technologies, systematically quantifies these electrophoretic trace characteristics to generate a standardized score on a 1-10 scale, with 10 representing perfect RNA integrity and 1 indicating completely degraded RNA [21].

Commercial systems and quality metrics

Several automated electrophoresis systems are available for RNA quality control, each employing slightly different but related metrics for assessing RNA integrity. The table below summarizes the primary platforms and their respective RNA quality metrics:

Table 1: Commercial RNA Quality Assessment Systems and Metrics

| System | Quality Metric | Metric Scale | Key Application Notes | Relevant Kits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2100 Bioanalyzer | RNA Integrity Number (RIN) | 1-10 [21] | Standard for total RNA QC; requires specific kits for different RNA types [21] | RNA 6000 Nano, RNA 6000 Pico [22] [21] |

| Fragment Analyzer | RNA Quality Number (RQN) | 1-10 [21] | Provides excellent resolution of total RNA profiles [21] | RNA Kit (15 nt), HS RNA Kit (15 nt) [21] |

| TapeStation | RIN Equivalent (RINe) | 1-10 [21] | Provides RIN values directly comparable to Bioanalyzer [21] | RNA ScreenTape, High Sensitivity RNA ScreenTape [21] |

| Femto Pulse | RNA Quality Number (RQN) | 1-10 [21] | Designed for ultralow concentration samples [21] | Ultra Sensitivity RNA Kit [21] |

For most bulk RNA-seq applications, a RIN value of ≥7.0-8.0 is generally considered the minimum threshold for proceeding with library preparation, though this may vary based on experimental goals and sample types [23]. In a recent study monitoring clinical blood samples stored for 7-11 years, 88% of samples maintained RIN values ≥8.0, demonstrating that proper preservation enables excellent long-term RNA integrity [23].

Sample preparation and preservation methodologies

Sample preservation strategies

Maintaining RNA integrity begins at sample collection, with rapid stabilization being critical for preventing degradation by ubiquitous RNases. For cell cultures, immediate preservation in commercial stabilization reagents like Zymo DNA/RNA Shield is recommended before RNA extraction [24]. For tissue samples, optimized fixation and dehydration protocols significantly impact downstream RNA quality. A 2025 study on bovine mammary epithelial cells demonstrated that a protocol combining chilled 70% ethanol fixation, staining with RNase inhibitors, and dehydration in absolute ethanol followed by xylene clearing effectively preserved RNA quality during laser capture microdissection procedures [25].

The timing of sample processing also critically affects RNA integrity. In laser capture microdissection applications, limiting the dissection time to less than 15 minutes (specifically 13.6 ± 0.52 minutes) significantly reduces RNA degradation [25]. Similarly, staining and dehydration steps should be optimized to minimize tissue exposure to aqueous media, ideally completing these procedures within 5 minutes to preserve RNA quality [25].

RNA extraction and storage considerations

Following preservation, RNA extraction should be performed using commercially available kits that include DNase digestion steps to remove genomic DNA contamination, particularly when using extraction methods that don't include this elimination [26]. For long-term storage, maintaining RNA at -80°C in RNase-free buffers ensures integrity preservation over extended periods, with studies confirming that RNA stored in PAXgene Blood RNA tubes at -80°C retained high quality and sequencing suitability for up to 11 years [23].

Table 2: Sample Input Guidelines for RNA-seq from Animal Cells

| Cell Type | Recommended Cell Number | Preservative | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical cultured cells (e.g., HeLa) | 1-2 × 10^5 cells | 50 µL Zymo DNA/RNA Shield | Default to higher end of range when possible [24] |

| Cells with lower RNA content (e.g., resting lymphocytes) | 2.5-5 × 10^5 cells | 50 µL Zymo DNA/RNA Shield | Requires more cells to obtain sufficient RNA yield [24] |

| Cells with high RNA content (e.g., hepatocytes) | 2.5-7.5 × 10^4 cells | 50 µL Zymo DNA/RNA Shield | Lower cell numbers sufficient due to high RNA content [24] |

Practical protocols for RNA quality assessment

RNA integrity measurement using bioanalyzer systems

The following workflow outlines the standard procedure for assessing RNA integrity using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer system, one of the most widely used platforms for this application:

This process involves several key steps. First, researchers must select the appropriate kit based on their expected RNA concentration: the RNA 6000 Nano kit for samples with higher concentrations or the RNA 6000 Pico kit for limited or dilute samples [21]. The system then performs electrophoretic separation, generating an electropherogram that displays the ribosomal RNA peaks (18S and 28S for eukaryotic samples) and any degradation products. Finally, the proprietary algorithm analyzes multiple features of this electrophoretic trace, including the ratio between ribosomal peaks, the presence of small RNA fragments, and the resolution between peaks, to calculate the RIN value [21].

Alternative assessment methods

While automated electrophoresis systems represent the gold standard, alternative methods can provide complementary RNA quality information. Traditional agarose gel electrophoresis remains a viable option for initial quality checks, allowing visualization of ribosomal RNA bands without specialized equipment [26]. For more precise quantification of RNA degradation in specific genomic regions, particularly in challenging samples like wastewater or archived specimens, digital RT-PCR methods offer targeted assessment of RNA integrity. A 2026 study introduced a Long-Range RT-digital PCR (LR-RT-dPCR) approach that evaluates RNA integrity by measuring detection frequencies of fragments across viral genomes, revealing that factors beyond fragment length—including intrinsic sequence characteristics of specific genomic regions—can influence RNA stability [27].

The scientist's toolkit: Essential reagents and materials

Successful RNA quality assessment requires specific reagents and materials throughout the workflow. The following table outlines key solutions and their functions:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for RNA Quality Assessment

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| DNA/RNA Shield or similar | Immediate RNase inhibition during sample collection | Cell culture preservation before RNA extraction [24] |

| RNase inhibitors | Prevention of RNA degradation during processing | Added to staining solutions for tissue sections [25] |

| DNase digestion reagents | Genomic DNA removal | Treatment after initial RNA extraction to prevent DNA contamination [26] |

| RNA Clean Beads | RNA purification and concentration | Post-DNase treatment clean-up; size selection [26] |

| Agilent RNA kits | Electrophoretic matrix and dyes | RNA 6000 Nano/Pico for Bioanalyzer systems [22] [21] |

| PAXgene Blood RNA tubes | RNA stabilization in blood samples | Long-term stability studies (up to 11 years) [23] |

| Ethanol/Xylene | Tissue fixation and dehydration | Preservation of RNA quality in tissue sections [25] |

Integration with bulk RNA-seq workflow

Quality control in the RNA-seq pipeline

RNA quality assessment represents the critical first step in a comprehensive bulk RNA-seq workflow. Following RIN determination, high-quality RNA proceeds through library preparation, with specific input requirements—for example, the SHERRY RNA-seq protocol is optimized for 200 ng of total RNA input [26]. Subsequent sequencing generates data that undergoes further QC using tools like RNA-SeQC, which provides metrics on alignment rates, ribosomal RNA content, coverage uniformity, 3'/5' bias, and other quality parameters essential for data interpretation [28]. This multi-stage quality assessment, spanning from wet-lab procedures to computational analysis, ensures that only robust, high-quality data informs biological conclusions.

Impact of RNA quality on downstream applications

RNA integrity directly influences sequencing outcomes and data interpretation. Degraded RNA samples typically exhibit 3' bias in coverage, as fragmentation preferentially preserves the 3' ends of transcripts [28]. This bias can lead to inaccurate gene expression quantification, particularly for longer transcripts, and may result in false conclusions in differential expression analyses. Additionally, samples with low RIN values often show reduced alignment rates and increased technical variation, potentially obscuring biological signals and reducing statistical power. Therefore, establishing and maintaining stringent RNA quality thresholds throughout sample processing is not merely a procedural formality but a fundamental requirement for generating biologically meaningful RNA-seq data.

Comprehensive RNA quality assessment, with RIN evaluation at its core, forms an indispensable component of robust bulk RNA-seq study design. From careful sample preservation through standardized integrity measurement, these quality control steps ensure that downstream gene expression data accurately reflects biological reality rather than technical artifacts. As RNA sequencing technologies continue to evolve and find applications across diverse fields—from clinical research to environmental virology [27]—maintaining rigorous standards for RNA quality will remain essential for producing reliable, reproducible results. For researchers beginning their journey into transcriptomics, mastering these fundamental practices provides the necessary foundation for successful experimentation and valid biological discovery.

This guide details the core steps of bulk RNA-seq library preparation, a foundational phase that transforms RNA into a sequence-ready library [29]. Mastering these fundamentals is crucial for generating robust and reliable gene expression data.

In bulk RNA-seq, library preparation is the process of converting a population of RNA molecules into a collection of cDNA fragments with attached adapters, making them compatible with high-throughput sequencing platforms [29]. The goal is to preserve the relative abundance of original transcripts while incorporating necessary sequences for amplification, sequencing, and sample indexing [29]. The standard workflow involves several key enzymatic and purification steps, which are summarized in the diagram below.

RNA Qualification and Fragmentation

The process begins with high-quality RNA. RNA Integrity (RIN) values greater than 7 are recommended, with clear 28S and 18S ribosomal RNA bands showing a 2:1 ratio on an electrophoretic gel [30]. The typical input requirement is 100 ng to 1 µg of total RNA [29].

Fragmentation breaks RNA into smaller, uniform pieces suitable for sequencing. This can be done enzymatically, chemically, or by sonication [29] [5]. The chosen method and conditions determine the final insert size in the library.

Reverse Transcription and cDNA Synthesis

Reverse transcription converts single-stranded RNA fragments into more stable complementary DNA (cDNA). This critical step uses reverse transcriptase enzymes to synthesize a complementary DNA strand from the RNA template [5] [29]. A common subsequent step is second-strand synthesis, which creates double-stranded cDNA (ds-cDNA) using a DNA polymerase, forming the physical template for the rest of the library preparation [30].

Table 1: Key Reagents for Reverse Transcription and cDNA Synthesis

| Reagent | Function |

|---|---|

| Reverse Transcriptase | Enzyme that synthesizes a complementary DNA strand from an RNA template [5]. |

| dNTPs (deoxynucleotide triphosphates) | Building blocks (A, dTTP, dGTP, dCTP) for synthesizing the cDNA strand [31]. |

| Primer (Oligo-dT or Random Hexamers) | Binds to the RNA template to initiate reverse transcription; oligo-dT primes from poly-A tails, while random hexamers prime throughout the transcriptome [29]. |

| RNase Inhibitor | Protects the RNA template from degradation by RNases during the reaction [31]. |

End Repair and Adapter Ligation

The blunt-ended, double-stranded cDNA fragments are not yet ready for ligation. The process involves:

- End Repair: The cDNA fragments are treated with enzymes to create blunt ends by repairing any damaged or overhanging bases [29].

- dA-Tailing: A single 'A' nucleotide is added to the 3' ends of the blunt fragments. This creates a complementary overhang for ligating adapters that have a single 'T' nucleotide overhang, improving ligation efficiency and specificity [30].

Adapter ligation attaches short, synthetic DNA sequences to both ends of the cDNA fragments. These adapters are essential for the sequencing process and typically contain three key elements:

- Sequencing Primers: Binding sites for the primers used during sequencing-by-synthesis on the flow cell [29].

- Sample Indexes/Barcodes: Short, unique DNA sequences that allow multiple libraries to be pooled and sequenced together (multiplexing), while retaining the ability to bioinformatically separate the data later [29].

- Flow Cell Binding Motifs: Sequences that allow the library fragments to bind to the complementary oligonucleotides on the surface of the sequencing flow cell [29].

This ligation step is typically performed using a DNA ligase enzyme like T4 DNA Ligase in a suitable reaction buffer [31].

Table 2: Overview of Core Library Preparation Steps

| Step | Primary Objective | Key Reagents & Enzymes |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Fragmentation | Produce RNA/DNA fragments of optimal size for sequencing. | Fragmentation enzymes or buffers [29]. |

| Reverse Transcription | Generate stable single-stranded cDNA from RNA. | Reverse Transcriptase, Primers, dNTPs, RNase Inhibitor [5] [31]. |

| Second Strand Synthesis | Create double-stranded cDNA. | DNA Polymerase, dNTPs [30]. |

| End Repair & dA-Tailing | Create uniform, ligation-ready ends on ds-cDNA. | End repair enzymes, dA-tailing enzyme [30] [29]. |

| Adapter Ligation | Attach platform-specific adapters and indexes to fragments. | T4 DNA Ligase, Ligation Buffer, Adapter Oligos [31] [29]. |

Library Amplification and Final QC

The adapter-ligated library is amplified by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) to generate sufficient material for sequencing. This enrichment step uses primers complementary to the adapter sequences [29]. Finally, the prepared library undergoes rigorous quality control, including quantification and assessment of size distribution using tools like a Bioanalyzer, to ensure success in sequencing [29].

Hands-On Bioinformatics Workflow: From FASTQ to Biological Interpretation

Within the broader context of a bulk RNA-seq data analysis workflow, quality control (QC) of the raw sequencing data is the critical first step that determines the reliability of all subsequent results, from differential gene expression to pathway analysis. The raw data delivered from sequencing centers, typically in the form of FASTQ files, can contain technical artifacts such as adapter sequences, low-quality bases, and contaminants. For researchers and drug development professionals, failing to identify and address these issues can lead to inaccurate biological interpretations, wasted resources, and invalid conclusions.

This guide focuses on two indispensable tools for this initial phase: FastQC, which provides a comprehensive assessment of read quality, and Trimmomatic, which cleans the data based on that assessment. Together, they form a robust pipeline for ensuring that your data is of sufficient quality to proceed with alignment and quantification, forming a solid foundation for your thesis research [32] [16].

The Quality Control Workflow: From Raw Reads to Clean Data

The standard QC procedure is a sequential process where the output of one tool informs the use of the next. The overarching workflow, from raw data to analysis-ready reads, is summarized below. This process ensures that only high-quality data is used for downstream alignment and differential expression analysis with tools like DESeq2 or edgeR [9] [13].

Read Assessment with FastQC

FastQC is a tool that provides a simple, automated way to generate a quality control report for raw sequence data coming from high-throughput sequencing pipelines [13] [33]. It does not perform any cleaning itself but gives you a diagnostic overview of the health of your sequencing run.

Key FastQC Modules and Interpretation

A FastQC report consists of several analysis modules. For beginners, the following modules are most critical for assessing RNA-seq data [13] [33]:

- Per Base Sequence Quality: This is often the most important graph. It shows the average quality score (Phred score) at each position across all reads. The goal is to have the majority of bases in the green (quality ≥ 28). A drop in quality at the ends of reads, particularly the 3' end, is common and may require trimming.

- Adapter Content: This plot shows the proportion of reads that contain adapter sequences at each position. Significant adapter contamination (>>0% in the first ~50 bases) requires trimming, as adapters can interfere with alignment.

- Per Sequence Quality Scores: This graph displays the average quality per read. It is useful for identifying a population of reads with universally low quality, which might indicate a specific problem during sequencing.

- Sequence Duplication Levels: Shows the proportion of duplicate sequences. High duplication levels in RNA-seq can be a sign of PCR over-amplification during library prep or low expression levels where the same transcript fragment is sequenced repeatedly.

- Overrepresented Sequences: Lists sequences that appear more frequently than expected. This can help identify contaminants or highly abundant RNAs (e.g., ribosomal RNA).

Running FastQC

The basic command to run FastQC on a single FASTQ file is straightforward [13]:

For paired-end data, you simply specify both files:

Aggregating Reports with MultiQC

When working with multiple samples, reviewing individual FastQC reports is inefficient. MultiQC is a tool that aggregates the results from FastQC (and many other bioinformatics tools) across all samples into a single, interactive HTML report [34] [33]. This allows for quick comparison and identification of systematic issues or outliers in your dataset. Running MultiQC is as simple as:

Read Cleaning with Trimmomatic

Once the quality issues have been diagnosed with FastQC, the next step is to clean the data using Trimmomatic. Trimmomatic is a flexible, efficient tool for trimming and filtering Illumina sequence data [32] [35]. It can remove adapters, trim low-quality bases from the ends of reads, and drop reads that fall below a minimum length threshold.

Core Trimmomatic Functions

Trimmomatic operates by applying a series of "steps" or functions in a user-defined order. The key functions for basic RNA-seq QC are [35]:

- ILLUMINACLIP: This step is crucial for removing adapter sequences. It requires a file containing the adapter sequences and parameters to control the stringency of the search.

- SLIDINGWINDOW: This performs a sliding window trimming, cutting reads once the average quality within the window falls below a specified threshold. This is more sensitive than whole-read trimming as it can remove poor-quality segments in the middle of a read.

- LEADING and TRAILING: These steps remove bases from the start (leading) or end (trailing) of a read if their quality is below a defined threshold.

- MINLEN: This step filters out reads that have been trimmed too short to be reliable in downstream alignment. The threshold depends on the aligner and reference genome, but a common value is 36 bases.

Trimmomatic in Practice: Commands and Parameters

The command structure for Trimmomatic differs for single-end (SE) and paired-end (PE) data. For paired-end data, which is common in RNA-seq, the command is more complex because it must handle both read pairs and generate output for reads where one partner was lost during trimming [13] [34].

Example Paired-End Command [13]:

Explanation of Parameters in the Command:

| Parameter | Function | Typical Value |

|---|---|---|

ILLUMINACLIP |

Removes adapter sequences. | TruSeq3-PE.fa:2:30:10 |

LEADING |

Removes low-quality bases from the start. | 3 |

TRAILING |

Removes low-quality bases from the end. | 3 |

SLIDINGWINDOW |

Scans read with a 4-base window, cuts if average quality drops below 15. | 4:15 |

MINLEN |

Drops reads shorter than 36 bases after all other trimming. | 36 |

Note: The ILLUMINACLIP parameters are complex. TruSeq3-PE.fa is the adapter file; 2 specifies the maximum mismatch count; 30 the palindrome clip threshold; and 10 the simple clip threshold [35].

After running Trimmomatic, it is a critical best practice to run FastQC again on the trimmed FASTQ files to confirm that the quality issues (e.g., low-quality ends, adapter content) have been successfully resolved [13].

The following table details the key software "reagents" required to implement this QC workflow effectively.

| Tool Name | Function in Workflow | Key Specification / "Function" |

|---|---|---|

| FastQC [13] [33] | Initial and final quality assessment of FASTQ files. | Generates a HTML report with multiple diagnostic graphs to visualize sequence quality, adapter contamination, GC content, etc. |

| Trimmomatic [32] [35] | Read cleaning and filtering. | Removes adapter sequences and low-quality bases using a variety of user-defined algorithms (e.g., SLIDINGWINDOW, ILLUMINACLIP). |

| MultiQC [34] [33] | Aggregation of multiple QC reports. | Parses output from FastQC, Trimmomatic, and other tools across many samples into a single, interactive summary report. |