The Genome's Hidden Complexity

How Gene Editing Is Revealing Nature's Masterpiece

Article Navigation

More Than Just Code

Imagine being handed the most complex book ever written—one with 3.2 billion letters spanning thousands of chapters, where some pages repeat nonsense phrases while others contain instructions that bring the entire work to life. Now imagine trying to edit this book with precision, knowing that a single misplaced comma could alter its meaning entirely. This is the extraordinary challenge scientists face as they explore the human genome through gene editing technologies.

Genomic Book Metaphor

The human genome contains enough information to fill 200 phone books of 1000 pages each.

Precision Editing

Modern tools can target single base pairs among billions with remarkable accuracy.

For decades, we viewed our DNA through a simplified lens—a linear code that could be "corrected" like typos in a document. But recent discoveries have revealed a far more dynamic reality: our genome is a three-dimensional, resilient structure capable of withstanding significant rearrangements while maintaining function. This article explores how gene editing technologies, particularly CRISPR, are not just tools for modifying DNA but powerful microscopes revealing the breathtaking complexity of our genetic blueprint.

The CRISPR Revolution: From Bacterial Defense to Genetic Scalpel

The story of modern gene editing begins in an unexpected place: the immune systems of bacteria. In the 1980s, scientists noticed peculiar repetitive DNA sequences in bacterial genomes—Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)—but their function remained mysterious for decades 4 . Eventually, researchers discovered that these sequences served as a bacterial defense system, capturing snippets of viral DNA to create a molecular memory of past infections 1 .

Did you know? The CRISPR-Cas9 system was originally discovered in yogurt bacteria (Streptococcus thermophilus) where it provides immunity against viruses that infect these bacteria during fermentation.

The real breakthrough came when scientists recognized they could harness this system as a programmable genetic tool. At the heart of this tool is the Cas9 protein, often described as "molecular scissors" that can cut DNA at precise locations. The cutting guide is provided by a piece of RNA that researchers can custom-design to match any DNA sequence they wish to target 7 . When the cell repairs this cut, it can introduce genetic changes—either disrupting a gene or incorporating a new DNA template provided by scientists.

How CRISPR-Cas9 Works

1. Guide RNA Design

Researchers design a custom RNA sequence that matches the target DNA.

2. Complex Formation

The guide RNA binds to Cas9 protein, forming the CRISPR complex.

3. Target Recognition

The complex scans DNA for matching sequences next to a PAM site.

4. DNA Cleavage

Cas9 cuts both strands of DNA at the target location.

5. DNA Repair

The cell repairs the break, potentially incorporating new genetic material.

What makes CRISPR truly revolutionary is its unprecedented accessibility. Earlier gene-editing technologies like ZFNs and TALENs required designing custom proteins for each target—a complex, time-consuming process 5 . With CRISPR, researchers need only synthesize a short RNA sequence to redirect the same Cas9 protein to new genomic addresses 4 . This simplicity has democratized gene editing, enabling thousands of laboratories worldwide to explore gene function and develop potential therapies.

Evolution of Gene Editing Tools

| Technology | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZFNs | Zinc finger proteins fused to FokI nuclease | First programmable nucleases | Difficult to design; limited targeting |

| TALENs | TALE proteins fused to FokI nuclease | Simpler design than ZFNs | Large protein size; challenging delivery |

| CRISPR-Cas9 | RNA-guided Cas nuclease | Simple redesign; highly versatile | Off-target effects; PAM sequence requirement |

The Genome Shuffling Experiment: Revealing Unexpected Resilience

As CRISPR became commonplace in laboratories, scientists began noticing something puzzling: the outcomes of gene editing experiments were often more complex and unpredictable than expected. This observation led to a groundbreaking series of experiments in 2025 that would challenge fundamental assumptions about genome stability and function 2 .

Researchers from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, Imperial College London, and Harvard University set out to answer a critical question: How much structural change can the human genome tolerate? Previous gene editing efforts typically focused on changing a few nucleotides at a time, but this team aimed to create the most extensively engineered human cell lines ever attempted 2 .

Methodology: Genome Shuffling at Scale

The experimental approach was both creative and ambitious:

- Prime editing insertion: Scientists used a precise CRISPR technique called prime editing to insert thousands of identical recognition sequences throughout the genome of human cell lines 2 .

- Recombinase activation: They introduced an enzyme called recombinase that recognizes these sequences and "shuffles" the genome by causing large-scale rearrangements—deletions, duplications, and inversions of DNA segments 2 .

- Outcome monitoring: The team then used genome sequencing to track which cells survived these massive structural changes and which didn't, providing a window into the genome's tolerance limits 2 .

Surprising Results: The Resilient Genome

The findings overturned conventional wisdom. Scientists discovered that human genomes are far more resilient to structural changes than previously thought. As long as essential genes remained intact, cells could withstand massive deletions and rearrangements involving hundreds of genes and still function normally 2 .

Even more surprisingly, large-scale deletions in non-coding regions often had minimal impact on gene expression elsewhere in the genome. This suggested that much of our DNA might be more dispensable than we assumed, challenging the notion that every segment of our genome serves a vital function 2 .

Types of Structural Variations in the Human Genome

| Variation Type | Description | Potential Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Deletion | Loss of DNA segment | Gene disruption if affecting coding regions |

| Duplication | Copying of DNA segment | Increased gene dosage possible |

| Inversion | Reversal of DNA orientation | May affect gene regulation |

| Translocation | Movement between chromosomes | Can create fusion genes |

The Complex Genomic Landscape: Recent Revelations

While the genome shuffling experiment demonstrated remarkable resilience, other research has been revealing just how complex and variable our genomes truly are. The 1000 Genomes Project, an international research consortium, recently published the most complete view to date of human genetic variation using advanced long-read sequencing technologies 6 .

Discovery Highlight: Each human carries approximately 2,000-2,500 structural variants that affect millions of base pairs of DNA, accounting for more variable base pairs than single nucleotide variants.

These studies uncovered millions of structural variations—large differences where entire segments of DNA are deleted, duplicated, inverted, or inserted between individuals. These aren't rare occurrences; each of us carries thousands of such variations that make our genomes unique 6 . Some key insights from this research include:

Repetitive Elements

Once dismissed as "junk DNA," these elements play active roles in creating genetic diversity by moving stretches of DNA to new genomic locations 6 .

Centromeres

Chromosomal regions essential for cell division that were previously too complex to study contain significant variation that may contribute to disorders including immune diseases and cancer 6 .

Variation Maps

Using comprehensive variation maps as reference significantly improves identification of disease-associated variants compared to previous methods 6 .

These discoveries fundamentally change how we think about gene editing. We're not working with a static, linear code but a dynamic, three-dimensional structure where the position and spatial organization of genes may be as important as their sequence.

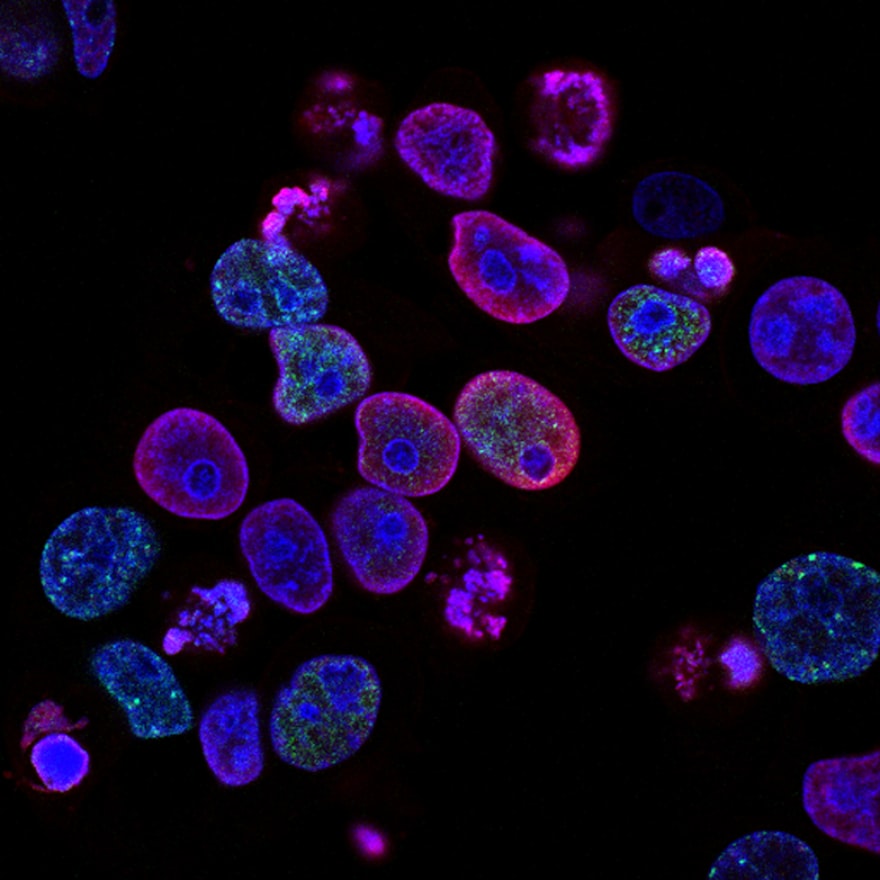

Distribution of different types of structural variations across human populations based on data from the 1000 Genomes Project. Deletions are the most common type of structural variation.

The Double-Edged Sword: Safety in Precision Editing

The complexity of the genome presents both opportunities and challenges for therapeutic gene editing. As CRISPR-based therapies move toward clinical use, scientists are discovering that the technology can sometimes cause unintended structural damage to the genome 9 .

Beyond the well-known concern of "off-target" edits at similar DNA sequences, researchers have observed more concerning patterns: large deletions, chromosomal rearrangements, and even megabase-scale losses (affecting millions of DNA letters) at the intended target sites 9 . These findings emerged from advanced detection methods that revealed consequences invisible to earlier analytical techniques.

Particularly concerning is that some strategies developed to enhance precise editing may inadvertently increase risks. For instance, inhibitors of DNA-PKcs—a protein involved in DNA repair—while boosting certain types of precise edits, can cause a thousand-fold increase in chromosomal translocations 9 . This creates a delicate balancing act for therapeutic development: how to maximize benefits while minimizing potential harm.

The recent approval of Casgevy, the first CRISPR-based therapy for sickle cell disease and transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia, demonstrates this balance in action 5 . The treatment edits a specific genomic region to reactivate fetal hemoglobin production, but studies show that the editing process can cause large deletions at the target site in hematopoietic stem cells 9 . The clinical significance of these findings remains unclear, but they highlight the critical need for continued safety optimization.

CRISPR Safety Considerations and Mitigation Strategies

| Safety Concern | Description | Current Mitigation Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Off-target effects | Editing at unintended similar sequences | High-fidelity Cas variants; improved gRNA design |

| On-target structural variations | Large deletions or rearrangements at target site | Advanced screening methods; alternative editors |

| Chromosomal translocations | Exchange between different chromosomes | Avoiding simultaneous cuts; modulating repair |

| p53 activation | Stress response potentially favoring mutant cells | Transient p53 inhibition; careful monitoring |

Future Directions: Navigating Complexity with New Tools

The evolving understanding of genomic complexity is driving development of more sophisticated editing tools. Among the most promising are:

Base Editing

Allows conversion of one DNA base to another without cutting both DNA strands, reducing structural variations 5 .

Prime Editing

Offers even greater precision for making specific DNA changes while minimizing DNA break-associated risks 1 .

Epigenome Editing

Modifies how genes are regulated without changing the underlying DNA sequence, potentially offering reversible treatments .

These technologies represent a paradigm shift from "cut and paste" approaches toward more subtle genomic fine-tuning that respects the complex architecture of the genome.

Emerging Trend: The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning is accelerating progress in gene editing. AI models can now predict both editing efficiency and potential off-target effects, optimizing guide RNA design . When combined with single-cell sequencing technologies that reveal how edits affect entire cellular networks, these approaches are helping researchers navigate the genome's complexity with increasing confidence.

Conclusion: Embracing Complexity

The journey of gene editing has evolved from a simple narrative of "fixing typos" in our genetic code to a far more profound recognition: we are working with a masterpiece of evolutionary engineering whose complexity we are only beginning to appreciate. The genome's resilience to structural change reveals a robustness that may ultimately make therapeutic editing safer than we feared, while its intricate architecture demands respect for unintended consequences we are only now learning to detect.

"If the genome was a book, you could think of a single nucleotide variant as a typo, whereas a structural variant is like ripping out a whole page. Through shuffling genomes at large scale, we've shown that our genomes are flexible enough to tolerate significant structural changes."

What emerges from these discoveries is a more nuanced relationship with our genetic blueprint—one that recognizes that precision requires understanding complexity, not simplifying it. As research continues, each revelation about the genome's hidden architecture provides not just new challenges but new opportunities to align our editing technologies with the elegant design of nature's oldest language.

This resilience offers both caution and comfort as we continue to explore the final frontier of human biology. The more we learn about the genome's hidden complexity, the more we appreciate that gene editing is not just about rewriting code, but about learning to read and respect one of nature's most sophisticated masterpieces.