Troubleshooting Differential Expression Analysis: A Modern Guide to Overcoming Statistical Pitfalls and Improving Reproducibility

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and bioinformaticians facing challenges in differential expression (DE) analysis.

Troubleshooting Differential Expression Analysis: A Modern Guide to Overcoming Statistical Pitfalls and Improving Reproducibility

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and bioinformaticians facing challenges in differential expression (DE) analysis. Covering both bulk and single-cell RNA-seq data, we explore foundational statistical concepts, common methodological errors, and advanced solutions for complex data types like spatial transcriptomics. We dissect major pitfalls, including false positives from unaccounted spatial correlations, the 'curse of zeros' in single-cell data, and poor cross-study reproducibility. The guide offers practical troubleshooting strategies, compares modern tools and pipelines, and outlines robust validation frameworks to ensure biologically meaningful and reproducible DE findings for drug discovery and clinical research.

Understanding the Core Challenges and Statistical Pitfalls in DE Analysis

The Critical Importance of Experimental Design and Biological Replicates

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why are biological replicates considered more important than technical replicates or increased sequencing depth in RNA-seq experiments?

Biological replicates are essential because they allow researchers to measure the natural biological variation that exists between different individuals or samples from the same condition. This variation is typically much larger than technical variation introduced during library preparation or sequencing. While technical replicates can measure experimental noise, they provide no information about whether an observed effect is reproducible across different biological subjects. Furthermore, investing in more biological replicates generally yields a greater return in statistical power for identifying differentially expressed genes than investing the same resources in deeper sequencing [1] [2].

FAQ 2: What is the minimum number of biological replicates required for a reliable differential expression analysis?

There is no universal minimum, but the common practice of using only 2-3 replicates is widely considered inadequate. Studies have shown that with only three replicates, statistical power is low, leading to a high false discovery rate and an inability to detect anything but the most dramatically changing genes. It is strongly recommended to use a minimum of 4-6 biological replicates per condition, with more replicates required for detecting subtle expression changes or when biological variation is high [2].

FAQ 3: How can I tell if my experiment has a "batch effect," and what can I do to fix or prevent it?

You likely have batches if your RNA isolations, library preparations, or sequencing runs were performed on different days, by different people, using different reagent lots, or in different locations [1]. To prevent confounding from batch effects, do NOT process all samples from one condition in one batch and all from another condition in a separate batch. Instead, DO intentionally split your biological replicates from all conditions across the different batches. This design allows you to account for the batch effect statistically during your analysis [1] [3].

FAQ 4: My single-cell RNA-seq analysis is identifying hundreds of differentially expressed genes, many of which are highly expressed. Could this be a false discovery?

Yes, this is a common pitfall. Methods that analyze single-cell data on a cell-by-cell basis, rather than aggregating counts by biological replicate, are systematically biased towards identifying highly expressed genes as differentially expressed, even when no true biological difference exists [4]. To avoid these false discoveries, you should use "pseudobulk" methods. This approach involves aggregating counts for each gene within each biological sample (replicate) to create a single profile per sample, and then performing differential expression testing between groups of these sample profiles using established bulk RNA-seq tools like edgeR or DESeq2 [4] [5].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

Problem 1: High False Discovery Rate (FDR) and Low Sensitivity in Differential Expression Analysis

- Symptoms: The analysis produces a list of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) that has a high false positive rate upon validation, or it fails to detect genes known to be changing.

- Root Cause: The most common cause is an inadequate number of biological replicates, which leads to poor estimation of biological variation and low statistical power [2].

- Solution:

- Increase Replicates: Prioritize more biological replicates over higher sequencing depth. While 30-60 million reads may be sufficient for many analyses, strive for at least 4-6 biological replicates per condition [1] [2].

- Leverage Multiplexing: To make this cost-effective, use early-multiplexing library preparation techniques (e.g., Decode-seq, BRB-seq) that use sample barcodes to pool many samples early in the workflow, drastically reducing per-sample cost and enabling a higher number of replicates [2].

Table 1: Impact of Replicate Number on Analysis Performance [2]

| Number of Replicate Pairs | Sensitivity (%) | False Discovery Rate (FDR%) |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | 31.0% | 33.8% |

| 5 | 52.5% | 25.5% |

| 10 | 82.4% | 18.9% |

| 30 | 95.1% | 14.2% |

Problem 2: Analysis Failure or Errors Due to Insufficient Data

- Symptoms: The differential expression analysis pipeline fails to run and returns an error, often related to the model being unable to estimate variation. An example error is:

Error in .local(x, ...) : min_samps_gene_expr >= 0 && min_samps_gene_expr <= ncol(x@counts) is not TRUE[6]. - Root Cause: The statistical model (e.g., in tools like DRIMSeq) requires a minimum number of samples with non-zero counts for a gene to reliably estimate its expression. With too few replicates, this condition is not met.

- Solution: The primary solution is to increase the number of biological replicates. As a temporary workaround, you may adjust the model's filtering parameters (e.g.,

min_samps_gene_expr), but this is not a substitute for proper experimental design and may lead to less reliable results.

Problem 3: Confounded Experimental Design

- Symptoms: It is impossible to determine whether observed gene expression changes are due to the experimental condition of interest or another, unaccounted-for variable.

- Root Cause: The experimental groups are systematically different in more than one way. For example, if all control samples are from female mice and all treatment samples are from male mice, the effects of treatment and sex are confounded [1].

- Solution:

- At the design stage: Ensure that animals or samples in each condition are matched for variables like sex, age, litter, and genetic background.

- If matching is impossible: Balance these variables across conditions. For instance, ensure that each condition has an equal number of male and female subjects, and then include "sex" as a factor in the statistical model during analysis.

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental difference between a confounded design and a proper, balanced design that avoids confounding with batch effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for RNA-seq Experiments

| Item | Function / Description | Example Kits / Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation Kit | Extracts high-quality, intact total RNA from cells or tissues. RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 7.0 is often recommended. | PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit [3], RNeasy Kits |

| Poly(A) mRNA Enrichment Kit | Selects for messenger RNA by capturing the poly-A tail, enriching for mature transcripts and removing ribosomal RNA. | NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module [3] |

| cDNA Library Prep Kit | Converts RNA into a sequencing-ready cDNA library. Includes steps for fragmentation, adapter ligation, and index/barcode incorporation. | NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit [3] |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences added to each cDNA molecule during reverse transcription. They allow for accurate digital counting of original transcripts by correcting for PCR amplification bias [2]. | Included in Smart-seq2, Decode-seq, BRB-seq protocols |

| Sample Multiplexing Barcodes | Unique DNA sequences (indexes) added to each sample's library, allowing multiple libraries to be pooled and sequenced in a single run. | Illumina TruSeq indexes, Decode-seq USIs [2] |

Experimental Design and Analysis Workflow

A robust differential expression analysis rests on a foundation of sound experimental design. The following workflow outlines the critical steps, from initial planning to final analysis, that safeguard against common pitfalls and false discoveries.

Table 3: Recommended Sequencing Depth for Different RNA-seq Analyses [1]

| Analysis Type | Recommended Read Depth per Sample | Recommended Read Length | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Gene-level DE | 15-30 million single-end reads | >= 50 bp | 15 million may be sufficient with >3 replicates; ENCODE recommends 30 million. |

| Detection of Lowly Expressed Genes | 30-60 million reads | >= 50 bp | Deeper sequencing helps capture rare transcripts. |

| Isoform-level DE (Known Isoforms) | At least 30 million paired-end reads | >= 50 bp (longer is better) | Paired-end reads are crucial for mapping exon junctions. |

| Isoform-level DE (Novel Isoforms) | > 60 million paired-end reads | Longer is better | Requires substantial depth for confident discovery and quantification. |

FAQ 1: Are all zeros in my single-cell RNA-seq data missing values that should be imputed?

The Misconception: All zero counts in a single-cell RNA-seq dataset represent technical failures ("dropouts") and should be imputed to recover the true expression value.

The Reality: Zeros in scRNA-seq data represent a mixture of technical artifacts and biological reality. While some zeros result from technical limitations where low-abundance transcripts fail to be captured (true "dropouts"), many zeros accurately reflect the absence of gene expression in certain cell types or states. [7] [8]

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Determine Zero Origin: Investigate whether zeros are biologically meaningful by checking if they correlate with cell type markers or specific biological conditions. Technically driven zeros are more likely to occur for genes with low to moderate expression levels. [7]

- Use specialized models like DropDAE, a denoising autoencoder enhanced with contrastive learning, which is specifically designed to handle dropout events without making strong parametric assumptions about the data distribution. [7]

- Consider alternative approaches like Dropout Augmentation (DA), which regularizes models by adding synthetic dropout noise during training rather than imputing all zeros. This approach improves model robustness against zero-inflation. [8]

FAQ 2: Can I treat individual cells as biological replicates in differential expression analysis?

The Misconception: In single-cell RNA-seq experiments with multiple cells from few subjects, individual cells can be treated as independent biological replicates for statistical testing.

The Reality: Treating cells from the same biological sample as independent replicates constitutes "pseudoreplication" and dramatically increases false positive rates in differential expression analysis. Biological replicates (multiple independent subjects or samples per condition) are essential for statistically robust inference. [9]

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Implement Pseudobulk Methods: Account for between-sample variation by aggregating cell-level data into pseudo-bulk samples for each biological replicate and cell type, then apply bulk RNA-seq DE methods like edgeR, DESeq2, or limma-voom. [10] [9]

- Use Individual-Level Methods: Employ specialized single-cell methods like DiSC that extract multiple distributional characteristics from expression data and test their association with variables of interest while accounting for individual-level variability. [10]

- Experimental Design: Ensure your study includes sufficient biological replicates (multiple independent subjects) rather than just technical replicates (multiple cells from the same subject). [9]

Table 1: Characteristics of Zeros in Single-Cell RNA-seq Data

| Zero Type | Cause | Recommended Action | Tools/Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technical Zeros (Dropouts) | Technical limitations in transcript capture | Statistical modeling or imputation | DropDAE [7], DCA [7] |

| Biological Zeros | Genuine absence of gene expression | Preserve in analysis | None (keep original zeros) |

| Undetermined Zeros | Unknown origin | Cautious handling | DAZZLE with Dropout Augmentation [8] |

FAQ 3: Are bulk and single-cell RNA-seq data analysis pipelines interchangeable?

The Misconception: The same computational pipelines and statistical models can be applied interchangeably to both bulk and single-cell RNA-seq data.

The Reality: Bulk and single-cell RNA-seq data have fundamentally different statistical characteristics and require specialized analytical approaches. Single-cell data exhibits substantial zero-inflation, over-dispersion, and multi-level variability not present in bulk data. [7] [10]

Troubleshooting Guide:

- For Bulk RNA-seq: Use established bulk methods like limma, DESeq2, or edgeR that model gene counts without special zero-handling mechanisms. These assume relatively low zero frequencies and model biological variation between samples. [11] [12]

- For Single-Cell RNA-seq: Employ specialized frameworks like DiSC for individual-level analysis, MAST for zero-inflated data, or scDD for differential distributions that specifically address single-cell data characteristics. [10]

- Adapt Multi-Species Protocols: For multi-species samples, use enrichment strategies (rRNA depletion, targeted capture) and organism-specific alignment to address proportional composition differences. [13]

Table 2: Experimental Design Specifications for Robust Differential Expression Analysis

| Parameter | Bulk RNA-seq | Single-Cell RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum Biological Replicates | 3-5 per condition [12] | 3-5 subjects per condition [9] |

| Sequencing Depth | 20-30 million reads per sample [12] | 20,000-50,000 reads per cell [14] |

| Zero Handling | Limited need for special zero handling | Essential to use zero-aware methods [7] [8] |

| Replicate Unit | Biological sample (tissue, cell culture) | Biological subject (individual organism) [9] |

| Primary DE Methods | limma, DESeq2, edgeR [11] [12] | Pseudobulk + bulk methods, or specialized single-cell methods [10] [9] |

FAQ 4: Do I need different experimental designs for multi-species RNA-seq studies?

The Misconception: The same experimental design and sequencing depth used for single-species transcriptomics will suffice for multi-species studies.

The Reality: Multi-species transcriptomics requires special consideration of relative organism abundance, enrichment strategies, and sufficient sequencing depth to adequately capture the minor organism's transcriptome. [13]

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Estimate Proportional Composition: Use qRT-PCR or test sequencing to determine the relative abundance of each organism's RNA in your samples before full-scale sequencing. [13]

- Implement Enrichment Strategies: When the minor organism represents a small fraction of total RNA, use physical enrichment methods (FACS, laser capture microdissection) or molecular enrichment (rRNA depletion, targeted capture panels) to increase reads from the minor organism. [13]

- Apply Organism-Specific Alignment: Use separate reference genomes for each organism and sort reads accordingly before quantification to ensure accurate mapping and avoid cross-species misalignment. [13]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for RNA-seq Experiments

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| 10X Genomics 3' Gene Expression Kit [9] | Library prep for 3' scRNA-seq using polyA capture | Standard single-cell gene expression profiling |

| 10X Genomics 5' Gene Expression Kit [9] | Library prep for 5' scRNA-seq with immune profiling | Immune receptor sequencing (VDJ analysis) |

| NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit [13] | Removal of ribosomal RNA from total RNA | Prokaryotic transcriptomics or multi-species studies |

| Illumina Ribo-Zero rRNA Removal Kit [13] | Selective removal of ribosomal RNA | Enrichment of non-ribosomal transcripts |

| Targeted Capture Panels [13] | Custom probes for specific transcript enrichment | Minor organism enrichment in multi-species studies |

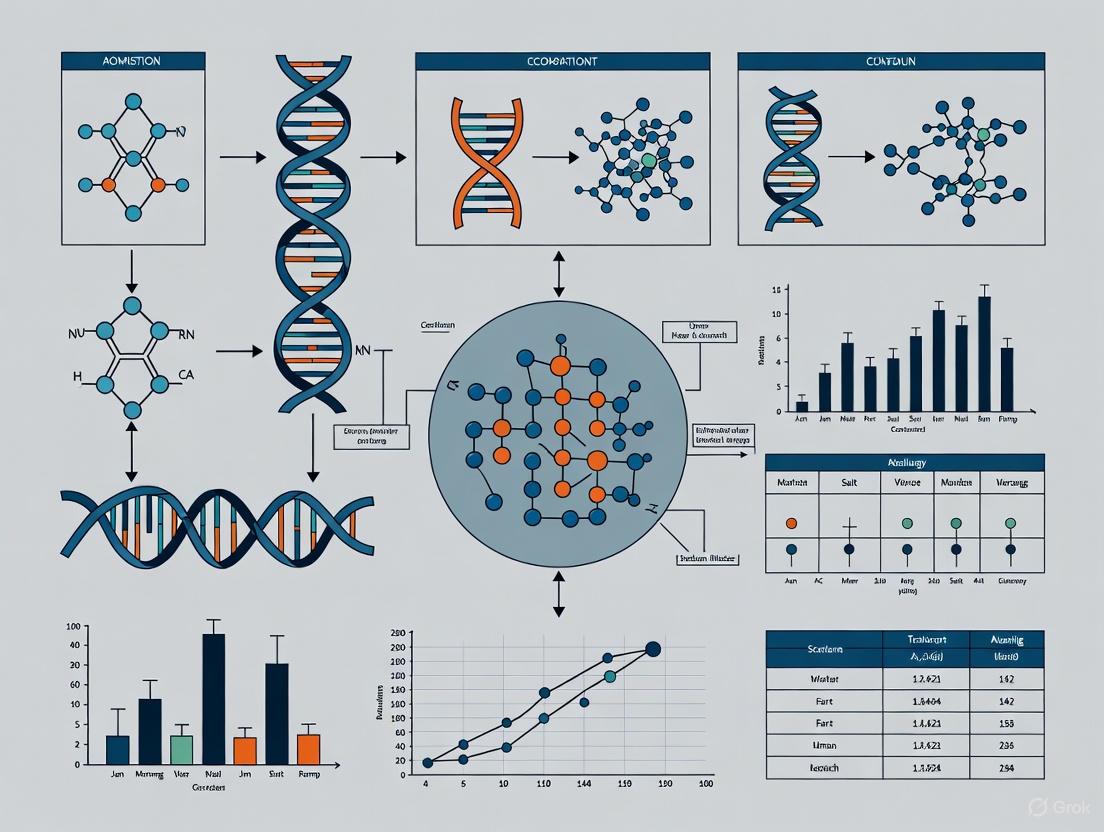

Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Bulk RNA-seq Analysis Workflow

Single-Cell RNA-seq Analysis Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions

What is spatial correlation in transcriptomic data, and why is it a problem? Spatial correlation refers to the phenomenon where nearby locations in a tissue sample have more similar gene expression patterns than distant locations. This is a natural property of biological tissues. However, in statistical analysis, it violates the common assumption that data points are independent. When this non-independence is not accounted for, it can dramatically inflate false-positive rates, leading you to believe you have found important biological signals when you have not [15].

I am using a standard Gene-Category Enrichment Analysis (GCEA) pipeline. How could spatial correlation affect my results? Standard GCEA often uses a "random-gene null" model, which assumes genes are independent. In spatially correlated data, genes within functional categories are often co-expressed, meaning their expression patterns are similar across space. When tested against a random null model, these categories appear to be significantly enriched far more often than they should. One study found that some Gene Ontology (GO) categories showed over a 500-fold average inflation of false-positive associations with random neural phenotypes [15].

What are the specific technical drivers of this false-positive bias? Two main drivers work in concert [15]:

- Within-category gene-gene coexpression: Genes that share a biological function are often expressed together.

- Spatial autocorrelation: Both gene expression maps and the spatial phenotypes you compare them to (e.g., disease severity gradients) are often smooth across the tissue. Two smooth, autocorrelated maps have a higher chance of correlating by chance.

Are there statistical methods designed to correct for this bias? Yes, newer methods are being developed that use more appropriate null models. Instead of randomizing gene labels ("random-gene null"), these methods use ensemble-based null models that assess significance relative to ensembles of randomized phenotypes. This approach accounts for the underlying spatial structure of the data [15]. Another method, SpatialCorr, is specifically designed to identify gene sets with spatially varying correlation structure, which can help uncover coordinated biological processes that are not detectable by analyzing individual genes alone [16].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Mitigating Spatial False Positives

Symptom: High Enrichment of Common Functional Categories

You run a GCEA on your spatial transcriptomic dataset and find strong enrichment for very general GO categories like "chemical synaptic transmission" or "metabolic process." You notice these same categories are reported as significant across many published studies, even when the studied phenotypes are vastly different [15].

- Potential Diagnosis: False-positive bias due to spatial correlation.

- Investigation & Solution:

- Benchmark with Random Phenotypes: Generate a set of random spatial maps with similar autocorrelation structure to your real phenotype. Run your GCEA pipeline on these random maps.

- Quantify Inflation: Calculate how often your GO categories are significantly enriched against these random maps. A high false discovery rate indicates your pipeline is biased.

- Adopt a Robust Null Model: Switch from a random-gene null to an ensemble-based null model that randomizes the phenotype while preserving its spatial autocorrelation [15].

Symptom: Concerns in Differential Expression (DE) Analysis

You are conducting a DE analysis between two tissue regions (e.g., tumor vs. normal) but are concerned that spatial autocorrelation and other technical artifacts are distorting your results.

- Potential Diagnosis: The "four curses" of single-cell DE analysis, which include challenges with excessive zeros, normalization, donor effects, and cumulative biases, can be compounded by spatial structure [17].

- Investigation & Solution:

- Validate DE Method Choice: Ensure your DE method (e.g., GLIMES, which uses a generalized Poisson/Binomial mixed-effects model) can account for batch effects and within-sample variation, and is robust to the high number of zero counts typical in single-cell data [17].

- Careful Normalization: Be aware that common normalization methods like Counts Per Million (CPM) convert absolute UMI counts into relative abundances, which can erase valuable biological information and introduce noise. Consider methods that preserve absolute counts [17].

- Account for Donor Effects: Use statistical models that include donor as a random effect to avoid false discoveries caused by correlations between cells from the same individual [17].

Quantitative Data on False-Positive Bias

Table 1: Factors Contributing to False Positives in Spatial Transcriptomic Analysis

| Factor | Description | Impact on False Positives |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Autocorrelation | The tendency for nearby locations to have similar values. | Greatly increases the chance of spurious correlations between a gene's expression and a spatial phenotype [15]. |

| Gene-Gene Coexpression | Genes within the same functional category have correlated expression patterns. | Causes standard "random-gene" null models to be invalid, leading to inflated significance for co-expressed categories [15]. |

| Inappropriate Normalization | Using methods like CPM that convert absolute UMI counts to relative abundances. | Can obscure true biological variation and introduce noise, affecting downstream DE results [17]. |

| Ignoring Donor Effects | Not accounting for the non-independence of cells from the same donor. | Leads to an overstatement of statistical significance and false discoveries [17]. |

Table 2: Comparison of Analytical Approaches

| Method / Approach | Key Principle | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard GCEA (Random-Gene Null) | Assesses significance by randomizing gene-to-category annotations [15]. | Simple, widely used. | Highly susceptible to false-positive inflation from spatial correlation and gene coexpression [15]. |

| Ensemble-Based Null Models | Assesses significance by randomizing the spatial phenotype (e.g., using spin tests) to preserve spatial autocorrelation [15]. | Accounts for spatial structure; dramatically reduces false positives. | Less commonly implemented in standard software packages. |

| SpatialCorr | Identifies gene sets with correlation structures that change across space (differential correlation) [16]. | Detects coordinated biological signals beyond changes in mean expression. | Does not test for enrichment against a pre-defined database like GO. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluating False-Positive Rate in Your GCEA Pipeline

This protocol helps you diagnose if your current enrichment analysis is affected by spatial bias [15].

- Generate Null Phenotypes: Create a large set (e.g., n=1000) of synthetic spatial maps that mimic the autocorrelation structure of your real phenotype. This can be done using spatial permutation techniques like spin tests or simulating Gaussian random fields.

- Run GCEA: Process each null phenotype through your exact GCEA pipeline (e.g., correlation with gene expression, then gene-set enrichment).

- Calculate False Discovery: For each Gene Ontology category, compute the fraction of null phenotypes for which it was significantly enriched (e.g., p < 0.05). This is its empirical false-positive rate.

- Interpretation: Categories with a high false-positive rate (>5%) are likely to be reported as significant in your real analysis due to bias rather than true biological signal.

Protocol 2: Identifying Spatially Varying Gene-Gene Interactions with SpatialCorr

This protocol outlines the steps for using SpatialCorr to find gene sets whose co-expression patterns change across a tissue [16].

- Input Preparation:

- Data: A spatial transcriptomics dataset (e.g., from 10X Visium).

- Gene Sets: Pre-defined sets of genes (e.g., from GO, KEGG, or custom pathways).

- Tissue Regions: (Optional) Pre-annotation of tissue regions (e.g., tumor, stroma).

- Parameter Estimation: SpatialCorr uses a Gaussian kernel to estimate a spot-specific correlation matrix for the genes in your set, capturing how correlations change smoothly across space.

- Hypothesis Testing:

- Within-Region Test (WR-test): For each region, tests if the correlation structure among genes is constant or varies significantly across spots within that region.

- Between-Region Test (BR-test): For regions with stable internal correlation, tests if the correlation structure is significantly different between two regions.

- Significance Assessment: p-values for both tests are computed via a sequential Monte Carlo (SMC) permutation procedure, and false discovery rate (FDR) is controlled using the Benjamini-Hochberg method.

- Output: A list of gene sets with significant spatially varying correlation, along with visualizations and gene-pair rankings showing which interactions drive the signal.

Methodologies and Workflows

GCEA with Ensemble-Based Null Models

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for a robust Gene-Category Enrichment Analysis that accounts for spatial structure.

The SpatialCorr Analysis Pipeline

This diagram outlines the key steps in the SpatialCorr method for detecting spatially varying gene-gene correlations [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Spatial Transcriptomics Analysis

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Ensemble-Based Null Model Software | Provides statistical methods to test for significance against spatially-aware random phenotypes, controlling for false positives. | Used in GCEA to avoid reporting biased GO categories [15]. |

| SpatialCorr (Python Package) | Identifies pre-defined gene sets whose correlation structure changes within or between tissue regions. | Discovering coordinated immune response pathways in cancer that vary by proximity to tumor cells [16]. |

| GLIMES (R/Package) | A differential expression framework using a generalized Poisson/Binomial mixed-effects model that handles zeros and donor effects. | Performing accurate DE analysis between cell types or tissue regions in single-cell or spatial data [17]. |

| Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) | A normalization method that adjusts for differences in library size and RNA composition between samples. | Normalizing RNA-seq data before DE analysis to reduce technical variability [18]. |

| Spatial Permutation Algorithms | Algorithms (e.g., spin tests) that generate null spatial maps preserving the original autocorrelation structure. | Creating negative controls for any spatial correlation analysis to establish a baseline false-positive rate [15]. |

Defining Differential Expression Beyond Simple Mean Differences

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of a "duplicate row.names" error in DESeq2? This error occurs when DESeq2 expects individual count files for each sample but receives a combined count matrix instead. DESeq2 requires distinct count files for each sample, where sample names are read from the files and factor labels are input on the analysis form. If using a count matrix, alternative tools like Limma or EdgeR are more appropriate as they accept this input format. Ensure each sample has a unique label and every line in your file contains the same number of columns. [19]

Why do DESeq2 and edgeR sometimes produce high false discovery rates (FDR) in population-level studies? With large sample sizes (dozens to thousands of samples), parametric methods like DESeq2 and edgeR can exhibit inflated false discovery rates, sometimes exceeding 20% when targeting 5% FDR. This occurs due to violations of the negative binomial distribution assumption, particularly when outliers exist in the data. For population-level RNA-seq studies with large sample sizes, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test is recommended as it better controls FDR in these scenarios. [20]

How many biological replicates are sufficient for differential expression analysis? Statistical power increases significantly with more biological replicates. While many studies use only 2-3 replicates due to cost constraints, this provides limited power to detect anything but the most strongly changing genes. Research shows that increasing replicates from 3 to 30 can improve sensitivity from 31.0% to 95.1% while reducing false discovery rates from 33.8% to 14.2%. A minimum of 3 biological replicates per condition is recommended, with more for complex experiments. [2]

What are the key differences between DESeq2, edgeR, and Limma?

- DESeq2 uses negative binomial generalized linear models with shrinkage estimation for dispersion and fold changes. It's robust to outliers and low count genes. [21]

- edgeR also employs a negative binomial model but offers greater flexibility in experimental design and implements empirical Bayes methods for improved performance with small sample sizes. [21]

- Limma was originally developed for microarray analysis but can be applied to RNA-seq data after appropriate transformations. It uses linear models and empirical Bayes methods, handling complex experimental designs well. [21]

How should I handle gene identifiers to avoid errors in differential expression tools? Use R-friendly identifiers: one word with no spaces, not starting with a number, and containing only alphanumeric characters and underscores. Avoid special characters like dots, pipes, or spaces, as these can cause problems with Bioconductor tools. If your identifiers include version numbers (e.g., "transcript_id.1"), try removing the ".1" and check for accidental duplicates. [22]

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Error Messages and Solutions

| Error Message | Tool | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| "duplicate row.names" | DESeq2 | Input is a count matrix instead of individual files | Supply individual count files for each sample or switch to Limma/edgeR with count matrix option [19] |

| "value out of range in 'lgamma'" | edgeR | Attempting to estimate dispersion from insufficient data | Use adequate biological replicates and ensure proper filtering with filterByExpr instead of custom filters [23] |

| FDR inflation with large sample sizes | DESeq2/edgeR | Violation of negative binomial distribution assumptions | For population-level studies with large N, use Wilcoxon rank-sum test instead [20] |

| "minsampsgene_expr >= 0 ... is not TRUE" | DRIMSeq | Filtering parameters incompatible with data structure | Check sample size and filtering criteria; adjust parameters to match data dimensions [6] |

Experimental Design Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Symptom | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate replication | Low power to detect DEGs; high false discovery rate | Increase biological replicates to at least 6-8 per condition; use power analysis to determine optimal N [2] |

| Poor data quality | High adapter dimer signals; flat coverage; high duplication rates | Implement rigorous QC; check RNA quality; verify quantification methods; optimize library preparation [24] |

| Batch effects | Unsupervised clustering shows grouping by processing date rather than condition | Include batch in statistical model; use batch correction methods (ComBat, SVA); randomize processing order [21] |

| Violation of distributional assumptions | Inflated FDR in permutation tests | For large sample sizes, use non-parametric methods (Wilcoxon); check model fit with diagnostic plots [20] |

Performance Comparison of Differential Expression Methods

| Method | Type | Best Use Case | FDR Control | Power with Small N | Power with Large N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | Parametric | Standard RNA-seq with adequate replicates | Moderate [20] | Good [25] | Good but with FDR issues [20] |

| edgeR | Parametric | Complex experimental designs | Moderate [20] | Good [25] | Good but with FDR issues [20] |

| Limma-voom | Parametric | Microarray data or transformed RNA-seq | Moderate [20] | Good | Good |

| Wilcoxon | Non-parametric | Population-level studies with large N | Excellent [20] | Poor with N<8 [20] | Excellent [20] |

| NOISeq | Non-parametric | Low replication studies | Good [20] | Moderate | Good |

Impact of Replication on Analysis Performance

| Number of Replicates | Sensitivity (%) | False Discovery Rate (%) | Cost & Practicality |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Very Low | Very High | Low cost but inadequate |

| 3 | 31.0 [2] | 33.8 [2] | Common but underpowered |

| 6-8 | Moderate | Moderate | Good balance |

| 12+ | High | Low | Ideal but expensive |

| 30 | 95.1 [2] | 14.2 [2] | Excellent but often impractical |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard RNA-seq Differential Expression Analysis with DESeq2

Methodology

- Input Preparation: Prepare individual count files for each sample with unique sample identifiers. Ensure gene identifiers use only alphanumeric characters and underscores. [22]

- Experimental Design: Assign factor levels (e.g., "Control", "Treatment") using only alphanumeric characters, avoiding spaces or special characters. [22]

- Data Preprocessing: Enable pre-filtering to remove genes with very low counts (default: pre-filter value = 1). [19]

- Normalization: DESeq2 automatically applies its median of ratios method to account for library size differences. [21]

- Dispersion Estimation: The tool estimates gene-wise dispersions and shrinks these estimates using an empirical Bayes approach. [25]

- Statistical Testing: Perform Wald tests or likelihood ratio tests to identify differentially expressed genes. [21]

- Multiple Testing Correction: Apply Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to control false discovery rate. [25]

Validation

- Confirm results with qPCR for selected genes using independent biological samples [21]

- Check distribution of p-values for uniformity under null hypothesis [25]

- Perform exploratory data analysis with PCA and sample-to-sample distance heatmaps

Protocol 2: Large-Sample Differential Expression with Robust Non-Parametric Approach

Methodology

- Data Preparation: For population-level studies with large sample sizes (N > 50 per group), use count normalized using TPM or similar methods. [21]

- Statistical Testing: Apply Wilcoxon rank-sum test instead of parametric methods to avoid FDR inflation. [20]

- Multiple Testing Correction: Use Benjamini-Hochberg procedure with Storey-Tibshirani adaptation for improved FDR control. [25]

- Outlier Handling: The rank-based approach naturally minimizes the influence of outliers without requiring specific filtering. [20]

Advantages

- Maintains appropriate false discovery rate control with large sample sizes [20]

- Robust to violations of distributional assumptions [20]

- Less sensitive to outliers in expression data [20]

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Decode-seq Method | Early multiplexing with barcoding | Enables profiling of many replicates simultaneously; reduces library prep cost to ~5% and sequencing depth to 10-20% [2] |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Corrects for PCR amplification bias | Attached during reverse transcription; enables accurate transcript quantification by counting distinct molecules [2] |

| Sample Barcodes (USIs) | Multiplexing multiple samples | Allows pooling of samples early in workflow; significantly reduces processing time and cost [2] |

| PhiX Control Library | Increases sequence diversity | Improves base calling accuracy when sequencing low-diversity libraries [2] |

| BRB-seq | 3' end barcoding and enrichment | Alternative cost-effective method for bulk RNA-seq; requires specialized sequencing setup [2] |

Quality Control Checklist

- Verify RNA integrity (RIN > 8 for most applications)

- Confirm accurate quantification using fluorometric methods (Qubit) rather than UV absorbance [24]

- Check for adapter contamination in FastQC reports [24]

- Ensure sufficient sequencing depth (typically 20-30 million reads per sample for standard RNA-seq)

- Confirm that reference genome, transcriptome, and annotation use consistent identifiers [22]

- Validate that all samples have the same number of columns in count files [19]

- Check for batch effects in PCA plots [21]

Workflow Diagrams

Differential Expression Analysis Troubleshooting Workflow

Experimental Design Decision Framework

Selecting and Applying Robust DE Methods for Bulk and Single-Cell Data

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does Salmon collapse identical transcript sequences in its index, and how does this affect my analysis? Salmon's indexing step automatically removes or collapses transcripts with identical sequences [26]. This is problematic because it means expression from multiple distinct genomic loci that produce identical transcripts will be attributed to a single, arbitrarily chosen transcript. If your analysis requires distinguishing between these duplicated regions, you should pre-process your transcriptome FASTA file to ensure each transcript entry is unique before building the Salmon index [26].

Q2: I received a warning from voom: "The experimental design has no replication. Setting weights to 1." What does this mean?

This warning occurs when voom cannot find any residual degrees of freedom to estimate the variability between samples. The most common cause is a design matrix that is too complex for your sample size, effectively leaving no replication for any experimental condition [27]. To fix this:

- Check your design matrix: Ensure the number of linearly independent columns is much smaller than the number of samples. A good rule of thumb is to have several more samples than parameters in your model [27].

- Simplify your model: Avoid including every available quality metric (like RIN, ribosomal content, or yield) as covariates. Start with a model that includes only the key factors of your experimental design [27].

Q3: Can I use limma-voom for an experiment that has no biological replicates?

While it is technically possible, it is strongly discouraged. Analysis without replicates does not provide a reliable estimate of within-group variability, making valid statistical inference for differential expression nearly impossible [28]. If you must proceed with no replicates, be aware that the results are exploratory and should not be used for drawing definitive biological conclusions. Some users may explore methods described in the edgeR vignette for this scenario, but these are not standard [28].

Q4: My pipeline failed because of a gene annotation error related to "names must be a character vector." What happened? This error often originates from the gene annotation file provided to the limma-voom pipeline. The tool expects a specific format [29]:

- The file must have a header row.

- The first column must contain the gene IDs.

- The second column is used for gene labels in plots.

- All rows must be unique. If your annotation tool (like

annotateMyIDs) produces a one-to-many mapping, it can create duplicate gene IDs, leading to this failure. Rerun your annotation tool and select the option to "Remove duplicates" to keep only the first occurrence of each gene ID [29].

Q5: Are the precision weights from voom being used correctly in my pseudobulk analysis?

There is a known issue in some implementations (e.g., in the muscat package) where the voom weights might be overwritten when additional sample-level weights (like those based on cell counts in single-cell RNA-seq) are passed to limma::lmFit [30]. A more correct procedure involves calculating the sample-level weights, passing them to voom, and then allowing lmFit to use the combined weights computed by voom without being overridden. Always check the documentation of your specific wrapper package to understand how it handles weights [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Read Mapping Rate in Salmon

A low mapping rate indicates that a small percentage of your reads are being successfully assigned to the transcriptome.

Solutions:

- Check RNA Quality: Inspect your raw read quality with FastQC. Degraded RNA with 3' bias can reduce mappability [31].

- Use a Decoy-Aware Transcriptome: This mitigates spurious mapping of reads originating from unannotated genomic loci that are sequence-similar to annotated transcripts. You can generate a decoy-aware transcriptome by mapping your transcripts against a hard-masked genome or by using the entire genome as a decoy [32].

- Adjust the k-mer Size: The

-kparameter during indexing sets the minimum acceptable length for a valid match. The default of 31 works for reads ≥75bp. For shorter reads, use a smaller k-mer size (e.g., 21 or 25) to improve sensitivity [32]. - Ensure Selective Alignment is Active: Selective alignment (

--validateMappings) is more sensitive and accurate. It is now the default in recent Salmon versions, but explicitly including the flag is good practice [32].

Problem: Errors During limma-voom Analysis Due to the Design Matrix

Errors or warnings related to the design matrix often stem from its structure being incompatible with the statistical model.

Solutions:

- Ensure Proper Replication: The design matrix must have fewer columns than rows, with ample residual degrees of freedom to estimate sample variability. A matrix with 9 samples should not have 8 or more predictor variables [27].

- Avoid Linearly Dependent Columns: Your design matrix columns must be linearly independent. For example, if you have a factor with three levels (A, B, C), your model should not include an intercept and three columns each representing a level.

limmawill automatically remove redundant columns, leading to "Partial NA coefficients" warnings [27]. - Use a Simple, Powerful Design: The power of limma-voom comes from sharing information across genes, not from over-parameterizing the model. Begin with a simple design (e.g.,

~0 + group) and only include necessary technical covariates known to have a significant effect [27].

Problem: Inconsistent Differential Expression Results

Unexpected or inconsistent DE results can arise from several points in the workflow.

Debugging Steps:

- Inspect Normalization: Confirm that normalization factors were calculated correctly using

calcNormFactorsinedgeRbefore runningvoom[33]. - Review the Workflow: Check that you have followed all steps in the established workflow, from quality control and filtering to the final model fitting. The diagram below outlines the critical steps and their logical relationships.

Workflow Diagram

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for bulk RNA-seq analysis, from raw data to differential expression results, highlighting key decision points.

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Salmon Quantification with Selective Alignment

This protocol describes how to quantify transcript abundance from bulk RNA-seq data using Salmon in mapping-based mode with selective alignment, which enhances accuracy [32].

1. Prerequisites:

- Software: Salmon installed.

- Data: A FASTA file of reference transcripts (

transcripts.fa) and paired-end FASTQ files (reads1.fq,reads2.fq).

2. Generating a Decoy-Aware Transcriptome (Recommended): To reduce spurious mappings, use a decoy-aware transcriptome. One method is to use the entire genome as a decoy.

- Concatenate the transcriptome and genome sequences:

cat transcripts.fa genome.fa > gentrome.fa - Create a decoys file (

decoys.txt) listing the names of all genome chromosomes.

3. Indexing the Transcriptome:

Build the Salmon index. Use a -k value smaller than 31 for shorter reads.

4. Quantification:

Run the quantification step on your reads. The library type (-l) must be specified correctly and before the read files.

Detailed Methodology: Differential Expression with limma-voom

This protocol covers the steps for a differential expression analysis after obtaining count data, for example, from Salmon [33].

1. Load and Prepare the Data:

2. Filtering and Normalization: Filter very lowly expressed genes to reduce noise and calculate normalization factors to adjust for library composition.

3. voom Transformation:

The voom function transforms the count data to log2-counts-per-million and computes precision weights for each observation.

4. Model Fitting and Hypothesis Testing: Fit a linear model and apply empirical Bayes moderation to the standard errors.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Software for Bulk RNA-seq Analysis

| Item Name | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Salmon | A fast and accurate tool for transcript quantification from RNA-seq data that can use either raw reads or alignments [32]. |

| limma (with voom) | An R package for the analysis of gene expression data. The voom function enables the analysis of RNA-seq count data using linear models [33]. |

| edgeR | An R package used for differential expression analysis. It is required for creating the DGEList object and for calculating normalization factors prior to voom [33]. |

| Decoy-Aware Transcriptome | A reference where decoy sequences (e.g., the genome) are appended to the transcriptome. This helps prevent misassignment of reads from unannotated loci [32]. |

| FASTQC | A quality control tool that provides detailed reports on raw sequencing data, including per-base sequence quality, GC content, and adapter contamination [31]. |

| Trimmomatic | A flexible tool for removing adapters and trimming low-quality bases from sequencing reads to improve overall data quality and mappability [31]. |

Table 2: Critical Parameters for Running Salmon Effectively

| Parameter | Typical Setting | Purpose and Notes |

|---|---|---|

-k |

31 (for reads ≥75bp) |

The k-mer size for the index. Use a smaller value (e.g., 21-25) for shorter reads to improve sensitivity [32]. |

--decoys |

decoys.txt |

File with decoy sequence names. Using a decoy-aware transcriptome is highly recommended to reduce spurious mapping [32]. |

--validateMappings |

[Enabled] |

Enables the selective alignment algorithm, which is more sensitive and accurate. It is now the default but specifying it is good practice [32]. |

-l |

A (automatic), IU (paired-end) |

Specifies the library type. Must be specified before read files on the command line [32]. |

Table 3: Common limma-voom Errors and Their Resolutions

| Error / Warning Message | Likely Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| "The experimental design has no replication. Setting weights to 1." | Design matrix is too complex (saturated), leaving no degrees of freedom to estimate variance [27]. | Simplify the design matrix by reducing the number of covariates. Ensure #samples > #parameters. |

| "Partial NA coefficients for X probe(s)" | The design matrix contains columns that are linearly dependent (redundant) [27]. | limma automatically handles this by removing redundant columns. Review your design for perfect co-linearity. |

| Analysis fails without replicates. | Statistical tools require replication to estimate biological variability [28]. | Always include biological replicates in your experimental design. Analysis without them is statistically unreliable. |

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our ability to study cellular heterogeneity, but differential expression (DE) analysis in this context presents unique computational challenges. Researchers face several obstacles including excessive zeros in the data, normalization complexities, donor effects, and cumulative biases that can lead to false discoveries [17]. This technical support center addresses these challenges through targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs, providing researchers with practical solutions for robust differential expression analysis.

Differential Expression Methods Comparison

The table below summarizes key differential expression methods, their statistical approaches, and optimal use cases:

| Method | Statistical Foundation | Data Type | Key Features | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAST | Two-part generalized linear model | Single-cell RNA-seq | Models cellular detection rate as covariate; handles zero-inflation | Testing DE across cell types or conditions accounting for technical zeros [34] [35] |

| GLIMES | Generalized Linear Mixed-Effects models | Single-cell with multiple samples | Uses raw UMI counts without pre-normalization; accounts for donor effects | Multi-sample studies with batch effects; requires donor-level replication [17] [36] |

| Wilcoxon | Rank-sum non-parametric test | Single-cell RNA-seq | Default in Seurat; robust to outliers | Initial exploratory DE analysis [35] |

| DESeq2 | Negative binomial model | Bulk or single-cell RNA-seq | Uses shrinkage estimation for dispersion; robust for low counts | UMI-based datasets with complex experimental designs [37] [35] |

Data Handling Across Methods

| Method | Normalization Approach | Zero Handling | Batch Effect Correction | Replicate Handling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAST | Requires pre-normalized data | Explicitly models as technical and biological events | Through inclusion in design formula | Not explicitly addressed |

| GLIMES | Uses raw UMI counts without normalization | Separate modeling of counts and zero proportions | Mixed model with random effects for batches/donors | Explicitly models donor effects [17] [36] |

| DESeq2 | Median of ratios size factors | Incorporated in negative binomial distribution | Through design formula | Handled via biological replicates [37] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Comprehensive Single-Cell Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated single-cell analysis workflow incorporating both MAST and GLIMES:

GLIMES Implementation Protocol

Methodology: GLIMES employs a two-model approach using raw UMI counts without pre-normalization:

- Poisson GLMM: Models UMI counts with random effects for donors/batches

- Binomial GLMM: Models zero proportions with the same random effects structure

Implementation Code:

MAST Implementation Protocol

Methodology: MAST uses a two-part generalized linear model that separately models:

- The probability of expression (hurdle component)

- The level of expression conditional on detection (Gaussian component)

Implementation Code:

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: MAST Returns No Differentially Expressed Genes

Problem: MAST differential expression analysis returns no significant genes despite clear biological differences between groups.

Solutions:

- Adjust filtering parameters: Lower

min.pctandlogfc.thresholdvalues

- Check cellular detection rate: MAST uses this as a covariate; ensure proper calculation

- Verify data normalization: MAST expects normalized data; confirm proper normalization

- Update packages: Ensure MAST and Seurat are updated to latest versions [38]

FAQ 2: Handling Excessive Zeros in Single-Cell Data

Problem: High zero counts in scRNA-seq data impacting DE analysis sensitivity.

Solutions:

- Understand zero sources: Distinguish between technical zeros (dropouts) and biological zeros (true non-expression)

- Method selection: Choose methods specifically designed for zero-inflated data (MAST, GLIMES)

- Avoid aggressive filtering: Maintain genes with biological zeros that may contain important information [17]

- GLIMES advantage: Uses raw UMI counts without imputation, preserving biological zeros [36]

FAQ 3: Addressing Donor Effects and Batch Confounding

Problem: False discoveries due to unaccounted donor-to-donor variation in multi-sample studies.

Solutions:

- Use mixed models: Implement GLIMES with donor as random effect

- Design consideration: Plan experiments with multiple biological replicates (donors)

- Batch correction: Apply appropriate integration methods (Harmony, scVI, CCA) before DE analysis [39]

FAQ 4: Normalization-Induced Artifacts

Problem: Normalization methods obscuring true biological signals or introducing artifacts.

Solutions:

- Method-specific considerations:

- GLIMES: Uses raw UMI counts, avoiding normalization artifacts [17]

- MAST: Requires properly normalized data as input

- DESeq2: Applies internal size factor normalization

- Library size awareness: Be cautious with CPM normalization which converts absolute UMI counts to relative abundances [17]

- Preserve absolute counts: For methods using raw counts (GLIMES), avoid pre-emptive normalization

FAQ 5: Selecting Appropriate DE Method for Experimental Design

Problem: Choosing suboptimal DE method for specific experimental designs.

Decision Framework:

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Corrects amplification bias; enables absolute quantification | Essential for GLIMES; preserves absolute counts [40] |

| DoubletFinder | Detects and removes cell doublets | Quality control before DE analysis [39] |

| SoupX | Corrects for ambient RNA contamination | Quality control for droplet-based protocols [39] |

| scran | Pooling normalization for single-cell data | Normalization for methods requiring pre-normalized data [39] |

| Harmony/scVI | Data integration and batch correction | Multi-sample studies before DE analysis [39] |

Experimental Quality Control Reagents

| Reagent/Control | Purpose | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Control RNA | Verify protocol efficiency | Use RNA mass similar to experimental samples (1-10 pg for single cells) [41] |

| Negative Control | Detect background contamination | Mock FACS sample buffer processed identically to experimental samples [41] |

| EDTA-/Mg2+-free PBS | Cell suspension buffer | Prevents interference with reverse transcription reaction [41] |

| RNase Inhibitor | Prevent RNA degradation | Include in lysis buffer during cell collection [41] |

Advanced Troubleshooting Scenarios

Complex Experimental Designs

Scenario: Dose-response studies with multiple time points and donors.

Solution:

- Use GLIMES with complex random effects structure

- Include interaction terms in model design

- Consider likelihood ratio tests for nested model comparisons

Implementation:

Visualization and Quality Assessment

Importance: Visual feedback is crucial for verifying model appropriateness and detecting analysis problems [42].

Recommended Visualizations:

- Parallel coordinate plots: Assess relationships between variables and identify problematic patterns

- Scatterplot matrices: Compare variability between replicates vs. treatment groups

- Mean-variance relationships: Check dispersion model assumptions

Tools:

bigPintR package for interactive differential expression visualization- Standard diagnostic plots from DESeq2 and MAST

- Custom visualizations of zero proportions versus mean expression

Successful navigation of the single-cell differential expression toolbox requires understanding both the statistical foundations of methods like MAST and GLIMES and their practical implementation challenges. By selecting methods appropriate for experimental designs, properly addressing zero inflation and donor effects, and employing rigorous quality control and visualization, researchers can overcome the key challenges in single-cell DE analysis. This technical support framework provides the necessary guidance for researchers to troubleshoot common issues and implement robust differential expression analyses in their single-cell studies.

FAQ 1: Why should I move beyond the Wilcoxon test for spatial transcriptomics data?

The Wilcoxon rank-sum test, while a default in popular tools like Seurat, is not ideal for spatial transcriptomic data because it assumes that all measurements are independent of one another [43]. Spatial transcriptomics data contains spatial autocorrelation, meaning that measurements from spots or cells close to each other are more likely to have similar gene expression levels than those farther apart [44]. Ignoring this dependency leads to an inaccurate estimation of variance, which causes:

- Inflated Type I Error Rates: The test produces artificially small p-values, identifying many genes as differentially expressed when they are not (false positives) [44] [43].

- Misleading Biological Conclusions: Enrichment analyses based on these false positives can highlight pathways unrelated to the actual biology being studied [43].

Statistical models that incorporate spatial information, such as Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) and Generalized Score Tests (GST), explicitly account for this spatial correlation, providing more reliable and valid results [44] [43].

FAQ 2: What are GEE and GST frameworks, and how do they help?

Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) are a statistical framework designed for analyzing correlated data. Instead of modeling the source of correlation (as with random effects in mixed models), GEEs use a "working" correlation matrix to account for the dependencies between nearby spatial measurements, making them robust and computationally efficient [43].

The Generalized Score Test (GST) is a specific test within the GEE framework. Its key advantage is that it only requires fitting the statistical model under the null hypothesis (no differential expression), which enhances numerical stability and reduces computational burden. This is particularly beneficial for genome-wide scans testing thousands of genes [43].

Extensive simulations show that the GST framework offers:

- Superior Type I Error Control: It effectively prevents the inflation of false positives common with the Wilcoxon test [43].

- Comparable Statistical Power: It identifies truly differentially expressed genes as effectively as other methods [43].

FAQ 3: How do I implement a spatial analysis using these methods?

The workflow for a spatially-aware differential expression analysis involves several key steps, from pre-processing to statistical testing. The diagram below outlines the core process for implementing a GEE/GST analysis.

Detailed Methodologies:

- Data Pre-processing: Begin with raw spatial data (e.g., from 10x Visium, Nanostring GeoMx or CosMx SMI). Use standard tools like

Space Rangerfor initial processing andSeuratorScanpyfor quality control, normalization, and initial clustering to define tissue domains or niches [45] [46]. - Formulate the Hypothesis: Clearly define the comparison for differential expression analysis. This is typically between two or more pre-defined tissue domains, pathology grades (e.g., ductal carcinoma in situ vs. invasive carcinoma), or cell types [44] [43].

- Model Fitting with GEE/GST: For each gene, fit a GEE model that includes the group label (e.g., tumor vs. normal) as a fixed effect and specifies a spatial correlation structure (e.g., exponential) for the "working" correlation matrix. The GST is then used to compute the p-value for the fixed effect [43].

- Implementation: The proposed GST method has been implemented in the R package

SpatialGEE, available on GitHub [43].

FAQ 4: When is it acceptable to use a non-spatial method?

While spatial models are generally recommended, non-spatial methods like the Wilcoxon test may be acceptable in specific scenarios. Research indicates that for platforms like Nanostring's GeoMx, where Regions of Interest (ROIs) are often selected to be spatially distant from one another, the spatial correlation between measurements is minimal. In such cases, non-spatial models might provide a satisfactory fit to the data [44]. However, for densely sampled technologies like 10x Visium or CosMx SMI, spatial models consistently provide a better fit and should be preferred [44].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High false positive rates | Use of non-spatial tests (e.g., Wilcoxon) on correlated spatial data, leading to variance underestimation [44] [43]. | Switch to a spatial method like GEE/GST or spatial linear mixed models (LMMs) that account for spatial autocorrelation [44] [43]. |

| Poor model convergence | High-dimensional, zero-inflated count data can cause convergence issues in complex models like Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMM) [43]. | Use the GST framework within GEE, which only requires fitting the null model and is more numerically stable [43]. Ensure data is properly normalized. |

| Weak or no spatial signal | ROIs or spots are too far apart, or the biological effect is not spatially structured [44]. | Verify the spatial autocorrelation in your data. For non-densely sampled designs (e.g., some GeoMx experiments), a non-spatial model might be sufficient [44]. |

Performance Comparison of Statistical Methods

The table below summarizes a comparative study of different statistical methods for identifying differentially expressed genes, based on simulations and real data applications [43].

| Method | Framework | Accounts for Spatial Structure? | Type I Error Control | Computational Efficiency | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test | Non-parametric | No | Inflated | High | Not recommended for standard spatial DE analysis due to false positives [43]. |

| Spatial Linear Mixed Model (LMM) | Mixed Effects | Yes (with random effects) | Good | Medium to Low | Densely sampled data (Visium, SMI); when random effects are explicitly needed [44]. |

| GEE with Robust Wald Test | Marginal / GEE | Yes (with "working" correlation) | Can be inflated | Medium | Correlated data analysis; less stable than GST for some data types [43]. |

| GEE with Generalized Score Test (GST) | Marginal / GEE | Yes (with "working" correlation) | Superior | High (only fits null model) | Recommended for genome-wide spatial DE analysis; robust and efficient [43]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Spatial Transcriptomics Experiment |

|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Visium | A commercial platform for NGS-based, whole-transcriptome spatial profiling at multi-cellular (spot-based) resolution [47] [46]. |

| Nanostring GeoMx | A commercial platform for targeted spatial profiling that allows user-selection of Regions of Interest (ROIs) based on morphology [44] [48]. |

| Nanostring CosMx SMI | A commercial platform for targeted, high-plex, sub-cellular resolution spatial imaging using in situ hybridization [44] [47]. |

| Seurat | A widely-used R toolkit for the analysis of single-cell and spatial transcriptomics data, often used for initial clustering and visualization [43] [46]. |

| Giotto | An R toolbox specifically designed for integrative analysis and visualization of spatial expression data, offering suite of spatial analysis methods [46]. |

| SpatialGEE | A specialized R package (available on GitHub) that implements the Generalized Score Test (GST) within the GEE framework for robust differential expression analysis [43]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the core purpose of pseudo-bulking in single-cell studies? Pseudo-bulking is a computational strategy used to account for donor effects and within-sample correlations in single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) studies. When you have multiple cells from the same donor, these cells are not statistically independent. Failing to account for this inherent correlation during differential gene expression (DGE) analysis leads to pseudoreplication, which artificially inflates the false discovery rate (FDR). Pseudo-bulking mitigates this by aggregating gene expression counts for each cell type within an individual donor before statistical testing [5].

2. When should I use a pseudo-bulk approach instead of cell-level methods? You should prioritize pseudo-bulk methods when your experimental design involves multiple biological replicates (e.g., multiple patients or donors) and you are testing for differences between conditions (e.g., disease vs. control) within a specific cell type. Bulk RNA-seq methods like edgeR and DESeq2, applied to pseudo-bulk data, have been found to perform favorably compared to many methods designed specifically for single-cell data, which can be prone to falsely identifying highly expressed genes as differentially expressed [5].

3. My data has strong batch effects. Should I correct for them before or after pseudo-bulking? Batch effect correction is a critical step that should be addressed. A recent evaluation of batch correction methods found that many introduce artifacts into the data [49]. The study recommends using Harmony, as it was the only method that consistently performed well without considerably altering the data [49]. It is generally advisable to perform any necessary batch effect correction before creating your pseudo-bulk counts.

4. What are the common methods for aggregating counts in a pseudo-bulk analysis? The two most common aggregation methods are the sum and the mean of gene expression counts across all cells of a given type from the same donor. While a consensus on the optimal approach is still emerging, pseudo-bulk methods using sum aggregation with tools like edgeR or DESeq2 are currently considered superior to naive cell-level methods [5].

5. What is a major technical source of variation I should consider in my experimental design? A significant source of technical variation is the batch effect, which arises from processing samples across different sequencing runs, days, or with different reagents [50]. Other sources include cell isolation efficiency, RNA capture efficiency, and PCR amplification biases, all of which can obscure true biological differences [50].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inflated False Discovery Rate (FDR) in DGE Results

Symptoms: Your differential expression analysis returns an unexpectedly high number of significant genes, many of which may not be biologically plausible.

Diagnosis: This is a classic sign of pseudoreplication. It occurs when statistical tests treat individual cells from the same donor as independent observations, ignoring the fact that cells from the same individual are more correlated with each other than with cells from other individuals [5].

Solution:

- Implement Pseudo-bulking: Re-analyze your data using a pseudo-bulk approach. For each donor and each cell type, aggregate the gene expression counts.

- Use Appropriate DGE Tools: Perform differential expression testing on the aggregated pseudo-bulk counts using robust methods designed for bulk RNA-seq, such as edgeR or DESeq2, which properly model biological variability between replicates [5].

Problem 2: Inability to Detect Statistically Significant DGE

Symptoms: Even when strong biological effects are expected, your DGE analysis returns very few or no significant genes.

Diagnosis: This can result from insufficient sequencing depth or too few biological replicates (donors). Low sequencing depth leads to sparse data and an underrepresentation of low-abundance transcripts, while few replicates provide low statistical power to estimate biological variance accurately [51] [52].

Solution:

- Optimize Sequencing Depth: Prior to a large study, conduct a pilot experiment to determine the optimal sequencing depth. Research suggests that for some cell types, a depth of 1.5 million reads per cell from 75 single cells can effectively quantify most genes [53].

- Increase Biological Replicates: Ensure your experiment includes a sufficient number of independent biological replicates (e.g., multiple donors per condition) rather than just many cells from a few donors. This is crucial for obtaining reliable DGE results [51] [52].

Problem 3: Persistent Batch Effects After Integration

Symptoms: Cells still cluster strongly by batch (e.g., sequencing run or processing day) rather than by biological group or cell type after attempted integration.

Diagnosis: The batch effect in your data is strong and may not have been effectively removed by the chosen correction method. Some batch correction methods can introduce artifacts or be poorly calibrated [49].

Solution:

- Choose a Recommended Method: Switch to a batch correction method that is less likely to introduce artifacts. According to a recent comparative study, Harmony is the best choice as it consistently performed well without considerably altering the data [49].

- Improve Experimental Design: For future studies, use blocking designs and multiplex samples across sequencing lanes to minimize the confounding of technical batches with biological conditions of interest [51].

Table 1: Comparison of Differential Gene Expression Methods for Single-Cell Data

| Method Type | Example Tools | Key Strength | Key Weakness | Recommendation for Donor Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudobulk (Sum) | edgeR, DESeq2, Limma | Accounts for within-donor correlation; high consensus performance [5] | Aggregates cellular heterogeneity | Recommended |

| Pseudobulk (Mean) | Custom pipelines | Accounts for within-donor correlation [5] | Performance relative to sum aggregation requires further investigation [5] | Use with Consideration |

| Mixed Models | MAST (with random effects) | Models cell-level data with donor as a random effect [5] | Computationally intensive; can be less robust than pseudobulk [5] | A Viable Alternative |

| Naive Cell-Level | Wilcoxon rank-sum, Seurat's latent models | Simple and fast | Severely inflates false discovery rate (FDR) by ignoring donor effects [5] | Not Recommended |

Table 2: Evaluation of Common scRNA-seq Batch Correction Methods

| Method | Changes Count Matrix? | Key Finding in Performance Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Harmony | No | The only method that consistently performed well without introducing measurable artifacts [49]. |

| ComBat | Yes | Introduces artifacts that could be detected in the evaluation setup [49]. |

| ComBat-seq | Yes | Introduces artifacts that could be detected in the evaluation setup [49]. |

| BBKNN | No | Introduces artifacts that could be detected in the evaluation setup [49]. |

| Seurat | Yes | Introduces artifacts that could be detected in the evaluation setup [49]. |

| MNN | Yes | Performed poorly, often altering the data considerably [49]. |

| SCVI | Yes/Imputes new values | Performed poorly, often altering the data considerably [49]. |

| LIGER | No | Performed poorly, often altering the data considerably [49]. |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Pseudo-bulk DGE Analysis with edgeR

This protocol is based on the analysis of a peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) dataset from 8 Lupus patients before and after interferon-beta treatment (16 samples total) [5].

1. Data Preparation and Quality Control

- Load Data: Start with a raw count matrix from a scRNA-seq experiment where

n_obsis the number of cells andn_varsis the number of genes. - Basic Filtering: Filter out cells with fewer than 200 genes detected and genes that are expressed in fewer than 3 cells to reduce noise [5].

- Ensure Raw Counts: Verify that the data object (

adata.X) contains raw counts for a negative binomial model. Store these in a dedicated layer.

2. Pseudo-bulk Count Aggregation

- Define Aggregation Groups: For each cell type of interest, and for each individual donor, aggregate the gene expression counts. This creates a new count matrix where rows are donor-cell-type combinations, and columns are genes.

- Summation: The standard approach is to sum the raw counts for each gene across all cells belonging to the same cell type and donor. This creates a "pseudo-bulk" library representing that cell type in that donor.

3. Differential Expression Analysis with edgeR in R

- Create DGEList Object: In R, load the aggregated count matrix and associated sample information (donor IDs, conditions, etc.) into a DGEList object, the core data structure for edgeR.

- Filter and Normalize: Filter out lowly expressed genes and apply the Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) normalization to correct for library composition.

- Design Matrix and Dispersion Estimation: Create a design matrix that models the experimental conditions. Then, estimate the common, trended, and tagwise dispersions to assess the variability of genes.

- Quasi-Likelihood F-Test: Fit a generalized linear model and test for differential expression using a robust quasi-likelihood F-test.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences used to tag individual mRNA molecules before PCR amplification. This allows for the accurate counting of original molecules, correcting for amplification bias [53]. |

| ERCC Spike-in RNA Controls | A set of synthetic RNA transcripts of known concentration and sequence added to the sample. They are used to monitor technical variation, including RNA capture efficiency and sequencing depth, but have limitations in matching the properties of endogenous RNA [53]. |

| Harmony | A computational batch integration tool for scRNA-seq data. It is recommended for correcting for batch effects without introducing significant artifacts, making it a key pre-processing step before pseudo-bulking [49]. |

| edgeR | A statistical software package in R for analyzing DGE from bulk or pseudo-bulk count data. It uses empirical Bayes methods and negative binomial models to provide robust DGE testing [5]. |

| DESeq2 | Another widely used R package for DGE analysis of bulk or pseudo-bulk data. It similarly uses a negative binomial model and shrinkage estimation for fold changes and dispersion [5]. |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Pseudo-bulk analysis workflow for DGE.

Diagnosing and Solving Common DE Analysis Failures

Addressing False Discovery Rate Inflation in Spatially Correlated Data

Why does my spatial transcriptomics analysis produce so many false positives?

In spatially correlated data, measurements from nearby locations are not independent, which violates a key assumption of many standard statistical tests. Using methods that ignore this spatial structure, such as the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (the default in popular platforms like Seurat), leads to an inflated number of false positives [43].

The underlying issue is that spatial dependence causes the data to contain less unique information than it would if all measurements were independent. When a statistical test that assumes independence is used, it overestimates the effective sample size. This overestimation increases the apparent statistical significance of differences, causing the False Discovery Rate (FDR) to rise beyond the nominal control level (e.g., 5%) [43] [54]. Essentially, the test is fooled into thinking the evidence is stronger than it truly is.

What specific methods should I use to control FDR in spatially correlated data?

You should replace non-spatial methods with statistical models that explicitly account for spatial correlation. The following table compares common problematic methods with recommended alternatives.

| Method Name | Type | Key Principle | Suitability for Spatial Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test | Non-parametric test | Ranks expression values to compare groups [43] | Poor. Assumes data independence; leads to inflated FDR [43]. |

| Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) with Generalized Score Test (GST) | Marginal model | Uses a "working" correlation matrix to model spatial dependence [43] | Superior. Demonstrates superior Type I error control and comparable power [43]. |

| Linear Mixed Model (LMM) | Conditional model | Models spatial correlation via random effects (e.g., exponential covariance) [43] | Good. Flexible for complex dependencies but can be computationally challenging for high-dimension data [43]. |