Unlocking the Secrets of Low Abundance Transcripts: A Comprehensive RNA-seq Guide for Biomedical Research

Detecting and accurately quantifying low abundance transcripts is a critical challenge in RNA-seq analysis, with significant implications for biomarker discovery and understanding disease mechanisms.

Unlocking the Secrets of Low Abundance Transcripts: A Comprehensive RNA-seq Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

Detecting and accurately quantifying low abundance transcripts is a critical challenge in RNA-seq analysis, with significant implications for biomarker discovery and understanding disease mechanisms. This article provides a complete guide for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of transcriptome biology and the technical hurdles of detecting rare RNAs. It explores advanced methodological solutions, from experimental library preparation to bioinformatics pipelines, and offers practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimization. By comparing the performance of various technologies and validation approaches, this resource equips scientists with the knowledge to design robust studies that fully leverage the potential of low-level transcript data for clinical and therapeutic insights.

The Hidden Transcriptome: Understanding the Biology and Challenges of Low Abundance RNAs

What are low abundance transcripts and why are they important?

Low abundance transcripts are RNA molecules present in cells at relatively low copy numbers. This category includes transcription factors, regulatory non-coding RNAs, and rare splice isoforms of genes [1]. Despite their low expression levels, these transcripts often play crucial regulatory roles. For instance, transcription factors can act as master regulators of downstream gene expression, and rare isoforms can encode proteins with specialized functions [1].

The study of these transcripts has revealed their significance in various biological processes. In ecological adaptation, low abundance transcripts differentiate subspecies of bluestem grasses with enhanced drought tolerance [1]. In medical research, single-cell RNA sequencing has identified low abundance transcripts in immune cell subtypes, providing insights into cellular heterogeneity and function [2] [3].

What are the key experimental design considerations for studying low abundance transcripts?

Sequencing Depth and Replicates

Adequate sequencing depth is critical for detecting low abundance transcripts. While standard RNA-seq for large genomes may recommend 20-30 million reads per sample, detecting rare transcripts often requires significantly deeper sequencing [4]. The LRGASP consortium found that greater read depth significantly improves quantification accuracy for these transcripts [5].

Biological replication is equally important. Studies with low biological variance within groups have greater power to detect subtle changes in gene expression [6]. For statistical robustness, include multiple biological replicates (typically n=3 or more) rather than pooling samples, as pooling removes the estimate of biological variance and can cause genes with high variance to appear differentially expressed [6].

Library Preparation and Sequencing Strategies

The table below compares RNA-seq approaches for studying low abundance transcripts:

Table 1: Comparison of RNA-Seq Approaches for Low Abundance Transcripts

| Method | Key Features | Best For | Limitations for Low Abundance Transcripts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Bulk RNA-Seq | Poly-A selection or rRNA depletion; 20-30 million reads for large genomes [4] | Transcriptome-wide expression profiling | May miss rare transcripts without sufficient depth/replication [6] |

| Ultra-Low Input RNA-Seq | Requires as little as 10 pg RNA or a few cells [4] | Limited sample availability | Similar limitations as standard RNA-seq but with higher technical noise [4] |

| Single-Cell RNA-Seq | Reveals cellular heterogeneity; identifies rare cell types [7] [8] | Cellular heterogeneity and rare cell populations | High background, technical noise, limited detection sensitivity [7] |

| Targeted Transcriptomics | Analyzes 400+ genes with minimal sequencing depth [2] [3] | Focused studies with limited sequencing budget | Restricted to predefined gene sets; not for discovery [2] [3] |

| Long-Read Sequencing | Captures full-length transcripts; better isoform resolution [5] | Identifying novel isoforms and splice variants | Higher error rates; lower throughput than short-read [5] |

Protocol selection significantly impacts detection capability. For single-cell RNA-seq, the SMART-Seq method is widely used, but requires careful technique to maintain cell viability and RNA integrity [7]. For full-length transcript identification, long-read sequencing (PacBio or Nanopore) outperforms short-read approaches, with libraries producing longer, more accurate sequences yielding more accurate transcripts [5].

Spike-in controls like the External RNA Controls Consortium (ERCC) synthetic RNA molecules help standardize RNA quantification across experiments. These controls enable researchers to determine the sensitivity, dynamic range, and accuracy of their RNA-seq experiments [4].

What computational strategies improve detection and quantification of low abundance transcripts?

Analysis Tools and Their Applications

Specialized statistical methods have been developed to handle the inherent noisiness of low-count transcripts:

Table 2: Computational Tools for Low Abundance Transcript Analysis

| Tool | Methodology | Advantages for Low Abundance Transcripts | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | Negative binomial distribution; shrinkage of LFC estimates [1] [9] | Shrinks LFC estimates toward zero when information is limited; improves stability [1] [9] | May be overly conservative for some applications [1] |

| edgeR robust | Negative binomial distribution; differential weighting [1] | Down-weights observations that deviate from model fit; reduces impact of outliers [1] | Requires careful specification of degrees of freedom parameter [1] |

| Cufflinks | Transcript assembly and abundance estimation [10] | Probabilistically assigns reads to isoforms; reports FPKM values with confidence intervals [10] | Incorporation of novel isoforms affects abundance estimates of known isoforms [10] |

Both DESeq2 and edgeR robust properly control family-wise type I error on low-count transcripts, with edgeR robust showing greater power and DESeq2 offering greater precision and accuracy [1].

Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs)

UMIs are random barcodes that label individual RNA molecules before PCR amplification. This enables bioinformatics tools to distinguish between technical duplicates (from PCR) and biological duplicates (actual transcript copies). UMIs are particularly valuable for:

- Correcting PCR bias and errors in abundance estimation [4]

- Experiments with deep sequencing (>50 million reads/sample) [4]

- Low-input library preparations [4]

Filtering Strategies

Traditional RNA-seq pipelines often filter out transcripts below arbitrary expression thresholds. However, recent assessments suggest that with modern statistical methods like DESeq2 and edgeR robust, such filtering may be unnecessary and could remove biologically relevant low-count transcripts [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Challenges and Solutions

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Issues with Low Abundance Transcripts

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| High background in negative controls | Contamination during library prep; insufficient bead cleanup | Maintain separate pre- and post-PCR workspaces; use strong magnetic device for bead separation [7] | Single-cell RNA-seq protocols emphasize clean technique and proper bead handling [7] |

| Low cDNA yield | Cell buffer interference; RNA degradation; suboptimal PCR cycles | Resuspend cells in EDTA-, Mg2+-, and Ca2+-free PBS; optimize PCR cycles for specific cell types [7] | Pilot experiments with control RNA help establish optimal conditions [7] |

| Inconsistent detection of low abundance transcripts across replicates | Insufficient sequencing depth; high biological variance; technical artifacts | Increase sequencing depth; include more biological replicates; use UMIs to account for technical noise [6] [4] | Technical variation is minimal compared to biological variation, but can substantially impact lowly expressed genes [6] |

| Poor identification of novel isoforms | Short-read sequencing limitations; incomplete annotation | Use long-read sequencing platforms; implement reference-free assembly approaches [5] | Long-read sequencing with reference-based tools performs best for transcript identification in well-annotated genomes [5] |

| Inaccurate quantification | PCR duplicates; mapping errors; incomplete transcript models | Implement UMI-based deduplication; use splice-aware aligners; integrate orthogonal data [4] [5] | Long-read tools currently lag behind short-read for quantification; incorporating replicates improves accuracy [5] |

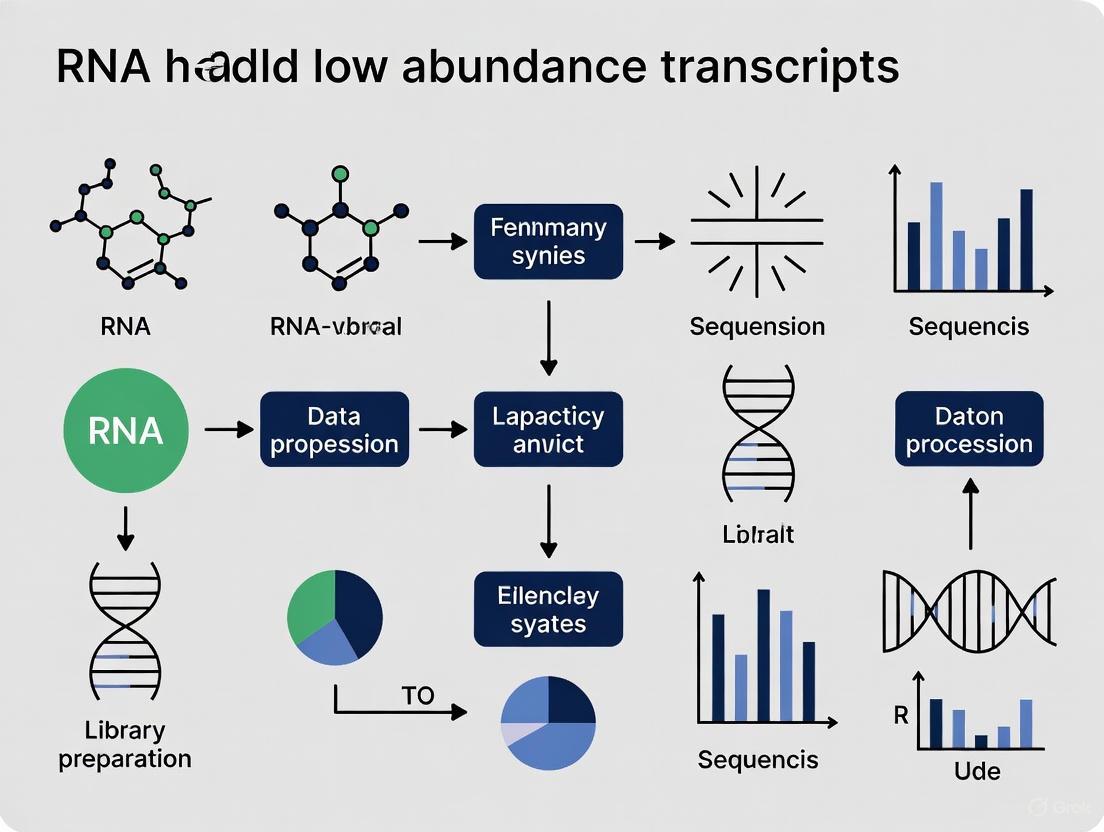

Workflow Diagrams for Low Abundance Transcript Analysis

Experimental Workflow for Targeted Low Abundance Transcript Detection

Computational Analysis Pipeline for Low Abundance Transcripts

Research Reagent Solutions for Low Abundance Transcript Studies

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ERCC Spike-In Mix | Synthetic RNA controls for standardization [4] | 92 transcripts across concentration range; enables QC metrics [4] |

| UMI Adapters | Unique barcodes for individual molecules [4] | Corrects PCR bias; essential for low-input protocols [4] |

| RNase Inhibitors | Prevents RNA degradation during processing [7] | Critical for single-cell and low-input workflows [7] |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA [4] | Improves detection of non-polyadenylated and low abundance transcripts [4] |

| Magnetic Beads | Sample cleanup and size selection [7] | Use low RNA/DNA-binding varieties to minimize sample loss [7] |

| Targeted Panels | Focused gene sets for efficient sequencing [2] [3] | Requires ~1/10th read depth while retaining sensitivity [2] [3] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What read depth is sufficient for detecting low abundance transcripts? A: While standard RNA-seq may require 20-30 million reads for large genomes, detecting low abundance transcripts typically requires significantly deeper sequencing. The exact depth depends on transcript rarity and study goals. The LRGASP consortium found that increased read depth improves quantification accuracy [5].

Q: Should I filter out low-count transcripts before differential expression analysis? A: Recent evidence suggests filtering at arbitrary thresholds may be unnecessary with modern statistical methods. Both DESeq2 and edgeR robust properly control type I error on low-count transcripts, making aggressive filtering potentially counterproductive [1].

Q: When should I use long-read vs. short-read sequencing for low abundance transcripts? A: Long-read sequencing excels at identifying novel isoforms and full-length transcripts, while short-read with sufficient depth may provide more accurate quantification. For comprehensive studies, a hybrid approach can be beneficial [5].

Q: How can I validate findings involving low abundance transcripts? A: Orthogonal validation methods include quantitative PCR for specific targets [8], cross-referencing with independent expression data [10], and utilizing spike-in controls to assess technical sensitivity [4].

Q: What special precautions are needed for single-cell studies of low abundance transcripts? A: Single-cell RNA-seq requires meticulous technique to minimize background, including using appropriate collection buffers, working quickly to prevent RNA degradation, and maintaining separate pre- and post-PCR workspaces [7]. Targeted approaches can improve detection while reducing required sequencing depth [2] [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: Detecting Low-Abundance Transcripts in RNA-Seq

Q1: My RNA-Seq data shows high background noise, masking low-abundance transcripts. What steps can I take?

A: High background noise often stems from ribosomal RNA (rRNA) contamination, which can constitute over 90% of total RNA and consume sequencing depth. To enhance the signal-to-noise ratio for detecting low-abundance targets:

- Implement Efficient rRNA Depletion: Use robust rRNA removal methods, such as FastSelect technology, which can remove >95% of rRNA/globin mRNA in a single step, even with fragmented RNA from FFPE samples [11]. This is superior to poly-A selection alone, which misses non-polyadenylated transcripts.

- Utilize Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): Incorporate UMIs during library preparation to correct for PCR amplification biases and errors [4] [12]. UMIs tag original cDNA molecules, allowing bioinformatic tools to accurately quantify transcript abundance and remove technical duplicates, which is crucial for deep sequencing to detect rare transcripts [4].

- Increase Sequencing Depth Strategically: While deeper sequencing (e.g., >50 million reads per sample for large genomes) can help capture rare transcripts, it also increases costs and noise [4] [13]. Combine increased depth with the above methods to maximize efficiency.

Q2: I have limited or degraded starting material (e.g., from FFPE or biopsies). How can I still obtain reliable data?

A: Working with low-input or degraded samples requires protocol adjustments to minimize sample loss and maximize data quality:

- Choose Specialized Low-Input Library Kits: Opt for library preparation chemistries explicitly designed for minimal RNA amounts (e.g., as low as 500 pg) [11]. These kits often have streamlined workflows with fewer purification steps to prevent sample loss.

- Employ Automated and Streamlined Workflows: Automation maximizes reproducibility and reduces handling errors, which is critical when sample is limited [12] [11]. Seek protocols that can be completed in a short time (e.g., 6 hours) to maintain RNA integrity.

- Select the Appropriate RNA Enrichment Method: For FFPE samples or other challenging types, rRNA depletion is strongly recommended over poly-A selection, as the latter is inefficient for fragmented RNA [4] [11]. For blood samples, combined rRNA and globin depletion is advised to improve detection of low-expression transcripts [4].

Q3: My differential expression analysis is sensitive to outliers. Are there more robust statistical methods?

A: Yes, standard methods like edgeR, SAMSeq, and voom+limma can be sensitive to outliers, leading to high false-positive rates. Consider:

- Robust t-statistic Models: Implement statistical models that use robust mean and variance estimators, such as those based on the minimum β-divergence method [14]. These models assign lower weight to outlying values, providing greater specificity and a lower false discovery rate (FDR) in the presence of data anomalies [14].

Q4: I am not detecting my target low-abundance transcript. How do I troubleshoot my workflow?

A: Systematically check each stage of your experimental and computational pipeline:

- Experimental Design:

- Replicates: Ensure you have an adequate number of biological replicates (not technical replicates or pooled samples) to reliably estimate biological variance and gain statistical power for detecting subtle expression changes [6].

- Sequencing Depth & Read Type: Confirm your sequencing depth is sufficient for your goal. Consider paired-end sequencing for better alignment and transcript isoform identification [6].

- Wet-Lab Protocol:

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Data Preprocessing: Use tools like

fastpfor quality control, adapter trimming, and UMI extraction/deduplication [4]. - Alignment and Quantification: Ensure reads are aligned with a splice-aware aligner (e.g., TopHat2, STAR) and accurately assigned to genes or transcripts [6].

- Data Integrity: Check for consistency in genome builds, chromosome names, and gene identifiers across all your input files, as mismatches are a common source of failure [15].

- Data Preprocessing: Use tools like

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the minimum number of reads recommended for detecting low-abundance transcripts?

A: While requirements vary by genome size and project goals, general recommendations are:

- Large genomes (human, mouse): 20-30 million reads per sample as a starting point [4]. Deeper sequencing (>50 million reads) may be necessary for comprehensive detection of low-abundance transcripts [4].

- Medium genomes: 15-20 million reads per sample [4].

- Small genomes (e.g., bacteria): 5-10 million reads per sample [4].

- De novo transcriptome assembly: 100 million reads per sample [4].

Q: Should I use poly-A selection or rRNA depletion for my study of low-abundance non-coding RNAs?

A: Use rRNA depletion. Poly-A selection only enriches for messenger RNAs with poly-A tails, thereby missing most long non-coding RNAs, primary miRNAs, and other non-polyadenylated transcripts. Total RNA sequencing with rRNA depletion provides a broader view of the transcriptome, essential for studying these RNA species [4] [12].

Q: When should I consider using Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) in my RNA-Seq experiment?

A: UMIs are highly recommended in two key scenarios [4]:

- Deep Sequencing: When performing deep sequencing (>50 million reads per sample) to accurately quantify transcript levels and correct for PCR duplicates.

- Low-Input Samples: When working with limited starting material for library preparation, where PCR amplification bias is more pronounced.

Q: Can I pool biological replicates before sequencing to reduce costs?

A: It is not generally recommended. While pooling replicates and using a binomial test can identify some differentially expressed genes, this approach removes the ability to estimate biological variance [6]. This can lead to false positives, especially for genes with high variance or low expression. Maintaining separate biological replicates and using statistical tests designed for them (e.g., based on a negative binomial distribution in DESeq2) provides greater power and reliability [6].

Data Presentation: Key Experimental Parameters

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Differential Expression Tools in Presence of Outliers

This table compares the performance of various statistical methods for identifying differentially expressed genes when the data contains outliers, based on a synthetic study [14]. Performance is measured using Area Under the Curve (AUC), where a higher value (closer to 1.0) indicates better performance.

| Method | 5% Outliers (AUC) | 10% Outliers (AUC) | 15% Outliers (AUC) | 20% Outliers (AUC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robust t-test (Proposed) | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.75 |

| edgeR | 0.56 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.56 |

| SAMSeq | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| voom+limma | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.41 |

| Standard t-test | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.46 |

Table 2: Recommended Solutions for Common Low-Abundance Challenges

This table summarizes key reagents and kits mentioned in the search results that address specific challenges in low-abundance transcript research.

| Challenge | Recommended Solution | Function |

|---|---|---|

| rRNA Contamination | QIAseq FastSelect rRNA removal kit [11] | Rapidly removes >95% of ribosomal and globin RNA to increase on-target reads. |

| Low-Input/FFPE RNA | QIAseq UPXome RNA Library Kit [11] | Library prep optimized for as little as 500 pg of input RNA, including fragmented FFPE samples. |

| PCR Amplification Bias | Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) [4] [12] | Molecular barcodes for cDNA molecules to correct for PCR duplicates and improve quantification accuracy. |

| Transcriptome Breadth | Total RNA-Seq (with rRNA depletion) [12] | Captures both coding and non-coding RNA species, providing a complete picture of the transcriptome. |

Workflow Visualization for Troubleshooting

Low Abundance Transcript RNA-Seq Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Low-Abundance Transcript Research

A detailed list of key materials and their specific functions to aid in experimental planning.

| Category | Item | Specific Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| rRNA Depletion | QIAseq FastSelect rRNA/globin kits [11] | Rapid, single-step removal of ribosomal and globin RNA to significantly improve the detection of informative, low-abundance transcripts. Critical for blood, FFPE, and total RNA-seq. |

| Library Preparation | QIAseq UPXome RNA Library Kit [11] | Enables library construction from ultralow input RNA (as little as 500 pg). Its streamlined protocol minimizes sample loss and is adaptable for 3' or complete transcriptome sequencing. |

| Sequencing Additives | ERCC Spike-In Mix [4] | A set of synthetic RNA controls of known concentration used to assess technical variation, sensitivity, and dynamic range of an RNA-Seq experiment. Not recommended for very low-concentration samples. |

| Molecular Barcodes | Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) [4] [12] | Short random nucleotide sequences added to each cDNA molecule during library prep. They allow for bioinformatic correction of PCR amplification bias and errors, ensuring accurate digital quantification. |

| Analysis Tools | Robust t-statistic methods [14] | Statistical approaches that use robust estimators (e.g., minimum β-divergence) to reduce the impact of outliers in the data, leading to lower false discovery rates in differential expression analysis. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the main sources of technical noise in single-cell and bulk RNA-seq? Technical noise originates from multiple stages of the RNA-seq workflow. In single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq), the very low starting amounts of RNA lead to incomplete reverse transcription and amplification, resulting in significant technical noise and inadequate coverage [16]. Common sources include:

- Amplification Bias: Stochastic variation during amplification causes skewed representation of genes, overestimating some expression levels [16] [17].

- Dropout Events: Transcripts, particularly low-abundance ones, can fail to be captured or amplified, leading to false-negative signals and an excess of reported zeros [16] [18].

- Batch Effects: Technical variations from different sequencing runs, library preparations, or experimenters can introduce systematic errors that confound biological results [16] [18].

- Low-Abundance Gene Bias: The quantification of genes with low expression levels is particularly prone to technical noise due to stochastic sampling and limits in sequencing depth [19].

2. How does technical noise impact the detection of low-abundance transcripts? Technical noise severely compromises the accurate detection and quantification of low-abundance transcripts. scRNA-seq data contains a large number of zeros; for lowly expressed genes, many of these zeros are "technical dropouts" (the gene was expressed but not detected) rather than true biological absences [18]. This high rate of missing data for low-level transcripts obscures genuine biological signal and can lead to:

- Underestimation of true expression levels.

- Inaccurate measures of cell-to-cell variability (noise) [20].

- Reduced power to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from background noise [21].

3. What computational methods can help mitigate technical noise? Several computational and statistical methods have been developed to address technical noise:

- Noise Regularization: Methods like

noisyRassess signal consistency across replicates to identify and filter out genes dominated by technical noise, improving downstream analysis like differential expression and gene network inference [19]. - Data Cleaning and Modeling: Tools like

RNAdeNoiseuse a data modeling approach to decompose observed counts into a "real signal" component (modeled with a negative binomial distribution) and a "random noise" component (modeled with an exponential distribution). It then subtracts the estimated maximum contribution of the random noise [21]. - Normalization and Imputation: Specialized scRNA-seq algorithms (e.g., SCTransform, scran, BASiCS) account for technical variability, though they may systematically underestimate true biological noise compared to gold-standard methods like smFISH [20]. Imputation methods can predict missing data from dropout events, but must be used cautiously to avoid introducing spurious correlations [16] [22].

4. How can I experimentally minimize technical variability? Good experimental design is crucial for managing technical noise.

- Use of Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): UMIs allow for the quantification of individual mRNA molecules, correcting for amplification bias [16] [18].

- Spike-in Controls: Adding known quantities of exogenous RNA transcripts helps monitor technical performance and control for variations in capture efficiency and amplification [16].

- Adequate Replication and Balanced Design: Including a sufficient number of biological replicates and randomizing samples across processing batches helps separate technical artifacts from true biological variation [6] [18].

- Standardized Protocols: Optimizing and standardizing steps from cell lysis and RNA extraction to library preparation maximizes RNA yield and quality, reducing technical variability [16] [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: High Proportion of Zero Counts and Suspected Dropout Events

Problem: Your scRNA-seq data shows an unexpectedly high number of genes with zero counts, especially among low to moderately expressed genes, making it difficult to distinguish technical dropouts from true biological silence.

Solution: Apply a systematic approach to identify, quantify, and mitigate the impact of dropout events.

Step 1: Diagnose the Extent of Dropouts Calculate the percentage of zeros per cell and per gene across your dataset. Compare this to the expected number of zeros based on the mean expression level to confirm a dropout problem [18].

Step 2: Apply a Noise Filtering or Cleaning Algorithm Use a tool like

RNAdeNoiseto clean your count data. The methodology is as follows:- Model the Distribution: The distribution of raw mRNA counts is modeled as a mixture of two independent processes: a real signal (Negative Binomial distribution) and a random, technical noise component (Exponential distribution) [21].

- Fit the Exponential Model: The exponential decay parameter is estimated by fitting the model to the low-count (near-zero) region of the data distribution, which is assumed to be primarily of technical origin [21].

- Calculate CleanStrength: Determine a subtraction threshold (CleanStrength parameter). This is the count value at which the exponential "tail" of the noise distribution falls below a defined significance level (e.g., 0.01) [21].

- Subtract Noise: Subtract the CleanStrength value from all mRNA counts in the sample. Any resulting negative values are set to zero [21].

Step 3: Validate Results After cleaning, re-examine the distribution of counts. The cleaned data should more closely follow a Negative Binomial distribution. Proceed with differential expression analysis on the cleaned data and observe if there is an increase in the number of detected DEGs, particularly for low to moderate abundance transcripts [21].

Issue: Batch Effects and Confounded Technical Variability

Problem: Unwanted technical variation, such as differences between sequencing lanes or library preparation dates, is a major source of variation in your dataset, potentially creating spurious clusters in dimensionality reduction plots (e.g., PCA, t-SNE) or masking true biological signals.

Solution: Identify, correct, and prevent batch effects.

Step 1: Detect Batch Effects Use exploratory data analysis to visualize whether cells or samples cluster by technical batch rather than by biological group. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plots are a standard tool for this. A strong association between a principal component and a known technical factor (e.g., sequencing lane) is indicative of a batch effect [18].

Step 2: Apply Batch Correction Use computational batch correction algorithms to remove systematic technical variation.

- Choose an Algorithm: Select a method appropriate for your data, such as Combat, Harmony, or Scanorama [16].

- Apply Correction: Input your normalized expression matrix and the batch covariate into the algorithm to obtain a corrected matrix.

Step 3: Prevent Batch Effects in Experimental Design The best solution is to prevent severe batch effects through careful experimental design [6] [18].

- Multiplexing: Whenever possible, index all samples and run them across all sequencing lanes to avoid confounding batch and biology.

- Blocking Design: If full multiplexing is not possible, use a balanced blocking design where samples from each biological group are distributed across all processing batches.

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies on technical noise and its impact on RNA-seq analysis.

Table 1: Quantitative Insights into Technical Noise in RNA-seq

| Finding | Metric/Value | Context / Implication | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| scRNA-seq Noise Underestimation | Systematic underestimation of noise fold-change | Compared to smFISH (gold standard), multiple scRNA-seq algorithms (SCTransform, scran, etc.) consistently underestimated the true magnitude of noise amplification. | [20] |

| IdU-induced Noise Amplification | ~73-88% of expressed genes showed increased noise (CV²) | A small molecule perturbation (IdU) was found to homeostatically amplify transcriptional noise across most of the transcriptome without altering mean expression levels. | [20] |

| RNAdeNoise Cleaning Threshold | Subtraction values ranged from 12 to 21 counts | The RNAdeNoise algorithm determined sample-specific thresholds for removing technical noise. This demonstrates that noise levels can vary significantly even between standardized samples. |

[21] |

| Low-Abundance Gene Bias | Higher technical noise and lower coverage uniformity | Genes with low expression levels show greater inconsistency in transcript coverage and are more severely affected by technical noise and dropout events. | [18] [19] |

Experimental Workflow: Differentiating Biological Signal from Technical Noise

The diagram below outlines a general workflow for handling technical noise in RNA-seq data analysis, from experimental design to validation.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and materials used to manage technical noise in RNA-seq experiments.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Managing Technical Noise in RNA-seq

| Reagent / Material | Function in Managing Technical Noise |

|---|---|

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences added to each molecule during library prep. They allow bioinformatic correction of amplification bias by collapsing PCR duplicates, leading to more accurate digital counting of original RNA molecules [16] [18]. |

| Spike-in Control RNAs | Known quantities of exogenous RNA (e.g., from the External RNA Control Consortium, ERCC) added to the sample. They are used to monitor technical sensitivity, estimate capture efficiency, and normalize for technical variation across samples [16]. |

| Cell Hashing Oligonucleotides | Antibodies conjugated to barcoded oligonucleotides that tag cells from different samples prior to pooling. This allows for sample multiplexing, reduces batch effects, and aids in identifying and removing cell doublets [16]. |

| Standardized Library Prep Kits | Commercial kits (e.g., from 10x Genomics, NuGEN) provide optimized, standardized protocols for steps like reverse transcription and amplification, which helps minimize protocol-specific technical noise and variability [6] [16]. |

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) research, the accurate recovery of rare transcripts is a significant challenge, particularly when working with degraded or low-input samples. These conditions, common in clinical fixed tissues, rare cell populations, or cadavers, exacerbate the natural limitations of sequencing technologies, where only a small fraction of a cell's transcripts are typically sequenced [23]. This technical noise disproportionately affects lowly and moderately expressed genes, making it difficult to distinguish true biological signals from artifacts. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these impacts is crucial for designing robust experiments and correctly interpreting data, especially when studying biologically meaningful variations in gene expression across cell types [23]. This guide addresses the specific technical hurdles posed by sample quality and provides actionable solutions for recovering rare transcriptional events.

FAQs: How Sample Quality Impacts Transcript Recovery

Q1: How does RNA degradation specifically affect rare transcript detection? RNA degradation fragments transcripts unevenly, with the 5' end typically degrading faster than the 3' end in FFPE samples. For rare transcripts, this means already sparse molecular evidence becomes even scarcer. Traditional poly-A enrichment methods fail because they require intact 3' polyadenylated tails [24]. Consequently, the already low probability of capturing rare transcripts diminishes further, as the available molecule fragments may not contain the sequences needed for library preparation, leading to their complete loss from the final dataset.

Q2: What are the key technical consequences of low-input RNA on library quality? Low-input RNA samples lead to several cascading technical issues:

- Reduced library complexity: With fewer starting RNA molecules, your sequencing library will represent a smaller fraction of the original transcriptome, increasing stochastic sampling effects.

- Amplification bias: Required amplification steps preferentially amplify abundant transcripts, further suppressing already rare transcripts.

- Increased background noise: The signal-to-noise ratio decreases, making it difficult to distinguish true low-expression genes from technical artifacts [23].

- Inflation of zero counts: A larger proportion of genes will show zero counts, not because they are truly unexpressed, but because they fell below the detection threshold [23].

Q3: Which RNA-seq methods perform best with degraded or low-input samples? Comparative studies have systematically evaluated various methods. The RNase H method demonstrated superior performance for chemically fragmented, low-quality RNA, effectively replacing oligo(dT)-based methods for standard RNA-seq [25]. For low-quantity RNA, SMART and NuGEN protocols showed distinct strengths [25]. More recently, sequence-specific capture methods (like RNA Exome Capture) that don't rely on polyadenylated transcripts have proven ideal for FFPE or degraded samples [24].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of RNA-Seq Methods for Challenging Samples

| Method | Best For | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNase H | Degraded/chemically fragmented RNA | Superior transcriptome annotation and discovery for low-quality RNA [25] | - |

| SMART | Low-quantity RNA | Effective with minimal input material [25] | - |

| NuGEN | Low-quantity RNA | Specific strengths for limited starting material [25] | - |

| RNA Exome Capture | FFPE/degraded samples | Does not rely on polyadenylated transcripts [24] | Focuses mainly on coding regions |

| Long-read RNA-seq | Full-length transcript recovery | Captures complete transcript isoforms even in mixed samples [5] | Higher error rates than short-read |

Q4: How can computational methods help recover signals from noisy data? Computational recovery methods like SAVER (Single-cell Analysis Via Expression Recovery) borrow information across genes and cells to obtain more accurate expression estimates for all genes [23]. These methods are particularly valuable for:

- Distinguishing true zeros from technical dropouts: Accurately determining which zero counts represent genuine non-expression versus technical artifacts [23].

- Recovering gene expression distributions: Preserving population-level characteristics like the Gini coefficient, which is crucial for identifying rare cell types [23].

- Maintaining biological variation: Retaining authentic cell-to-cell stochasticity while removing technical variation [23].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of SAVER in Downsampling Experiments

| Metric | Observed Data | SAVER Recovered | MAGIC/scImpute |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene-wise correlation | Baseline | Improved across all datasets [23] | Usually worse than observed data [23] |

| Cell-wise correlation | Baseline | Improved across all datasets [23] | Usually worse than observed data [23] |

| Differential expression detection | Much lower than reference | Most genes detected while maintaining FDR control [23] | - |

| Clustering accuracy (Jaccard index) | Baseline | Higher than observed for all datasets [23] | Consistently lower than observed [23] |

Experimental Protocols for Challenging Samples

Protocol: RNA Exome Capture for FFPE and Degraded Samples

Principle: This method uses sequence-specific capture probes that target coding regions without relying on intact polyadenylated tails, making it ideal for degraded samples [24].

Procedure:

- RNA Quality Assessment: Use appropriate quality control measures specific to FFPE samples (e.g., DV200 scores rather than RIN numbers).

- RNA Fragmentation: If necessary, fragment RNA to appropriate sizes (adapt duration based on degradation level).

- Library Preparation:

- Use random primers instead of oligo(dT) for first-strand cDNA synthesis.

- Ligate adapters compatible with your sequencing platform.

- Perform targeted enrichment using biotinylated probes designed against exonic regions.

- Post-Capture Amplification: Amplify the captured library with limited cycles to maintain representation.

- Quality Control: Verify library size distribution and concentration using appropriate methods.

Advantages: Overcomes 3' bias of degraded samples; provides more uniform coverage; enables analysis of samples with extensive degradation [24].

Protocol: Single-Cell RNA-seq Recovery Using SAVER

Principle: SAVER uses an empirical Bayes approach with Poisson Lasso regression to estimate true expression by borrowing information across genes and cells [23].

Procedure:

- Data Input: Provide a post-quality control UMI count matrix from your scRNA-seq experiment.

- Parameter Estimation:

- SAVER assumes counts follow a Poisson-Gamma mixture (negative binomial model).

- The method estimates prior parameters using Poisson Lasso regression with other genes as predictors.

- Expression Recovery:

- SAVER outputs the posterior distribution of true expression for each gene in each cell.

- The posterior mean is used as the recovered expression value.

- Downstream Analysis: Use recovered expression values for differential expression, clustering, and visualization.

Advantages: Preserves biological variation while reducing technical noise; provides uncertainty estimates; improves accuracy of gene-gene correlations and rare cell type identification [23].

Visualizing Experimental Strategies and Outcomes

Figure 1: Experimental strategies for recovering rare transcripts from challenging samples. This workflow illustrates how different sample quality challenges require specific experimental and computational solutions to achieve accurate rare transcript recovery.

Figure 2: Comparison of standard versus optimized approaches for rare transcript recovery. The optimized pathway combines specific experimental techniques with computational methods to overcome limitations of standard approaches when working with challenging samples.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Challenging RNA Samples

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Sample Compatibility | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNase H-based reagents | cDNA synthesis without poly-A dependency | Chemically fragmented, low-quality RNA [25] | Effective replacement for oligo(dT) methods |

| RNA Exome Capture panels | Targeted enrichment of coding transcriptome | FFPE and degraded samples [24] | Does not rely on polyadenylated transcripts |

| SMART technology | Template-switching cDNA amplification | Low-quantity RNA [25] | Effective with minimal input material |

| UMI adapters | Molecular barcoding for accurate quantification | Low-input and single-cell RNA-seq [23] | Distinguishes technical duplicates from biological expression |

| PhiX control | Sequencing process control | All sample types, especially challenging ones [26] | Acts as positive control for clustering efficiency |

The recovery of rare transcripts from degraded or low-input RNA samples remains challenging but tractable through integrated experimental and computational strategies. The field is moving toward approaches that combine optimized wet-lab protocols—like sequence-specific capture and random-primed library preparation—with sophisticated computational recovery tools that can distinguish technical artifacts from true biological signals. As long-read RNA-seq technologies mature, they offer promising avenues for capturing full-length transcript isoforms even from mixed-quality samples [5]. However, current evidence suggests that for well-annotated genomes, reference-based tools with orthogonal validation still provide the most accurate results [5]. For researchers pursuing drug development and clinical applications, adopting these multifaceted approaches is essential for extracting meaningful biological insights from the most challenging but scientifically valuable samples.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

1. My RNA-seq experiment failed to detect key, low-abundance transcripts. What are the primary factors I should investigate? The failure to detect low-abundance transcripts is often rooted in insufficient sequencing depth and suboptimal library complexity. For a global view of the transcriptome that includes less abundant transcripts, 30-60 million reads per sample is a typical requirement, while in-depth investigation or novel transcript assembly may require 100-200 million reads [27]. Furthermore, library preparation methods that fail to maximize complexity, such as those that do not account for RNA degradation or secondary structures, will reduce the chance of capturing rare transcripts [28] [29].

2. What is the minimum sequencing depth required for a standard toxicogenomics study with three biological replicates? A controlled study investigating a model toxicant found that a minimum of 20 million reads was sufficient to elicit key toxicity pathways and functions when using three biological replicates [29]. The identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) was positively associated with sequencing depth, showing improvement up to a certain point. This provides a benchmark for studies with a similar "three-sample" design [29].

3. How does library preparation impact the results of my RNA-seq study? The library preparation protocol is critical for reproducible results. Using the same library preparation method across your samples is vital for reproducible toxicological interpretation [29]. The choice between poly(A) selection and ribosomal RNA depletion is also crucial; poly(A) selection requires high-quality RNA, while ribosomal depletion is better for degraded samples or bacterial RNA [30]. Strand-specific library protocols are recommended for accurately quantifying antisense or overlapping transcripts [30].

4. What are common reverse transcription issues that affect library complexity and how can I fix them? Common issues during cDNA synthesis that lead to poor library complexity and truncated cDNA include [28]:

- Poor RNA Integrity: Always assess RNA quality prior to cDNA synthesis and minimize freeze-thaw cycles.

- Presence of Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors: Repurify RNA samples to remove inhibitors and consider using a reverse transcriptase that is resistant to common inhibitors.

- RNA Secondary Structures: Denature secondary structures by heating RNA to 65°C for ~5 minutes before reverse transcription and use a thermostable reverse transcriptase.

- Suboptimal Primers: For potentially degraded RNA, use random primers instead of oligo(dT) to ensure proper coverage across transcripts.

5. How do single-cell RNA-seq challenges differ from bulk RNA-seq when studying low-abundance transcripts? scRNA-seq presents unique challenges for detecting low-abundance transcripts, primarily due to low RNA input and amplification bias, which can skew the representation of specific genes [16]. Furthermore, dropout events (false-negative signals) are particularly problematic for lowly expressed genes. Solutions include using Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) to correct for amplification bias and employing computational methods to impute missing data [16].

Table 1: Recommended Sequencing Depth for Different RNA-Seq Goals

| Experiment Goal | Recommended Reads per Sample | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Targeted/Gene Expression Profiling | 5 - 25 million | Sufficient for a snapshot of highly expressed genes; allows for high multiplexing [27]. |

| Standard Whole Transcriptome | 30 - 60 million | Captures a global view of gene expression and some alternative splicing information; encompasses most published experiments [27]. |

| Novel Transcript Discovery/In-depth Analysis | 100 - 200 million | Required for assembling new transcripts and gaining an in-depth view of the transcriptome [27]. |

| Toxicogenomics (3 replicates) | Minimum 20 million | Found to be sufficient to elicit key toxicity pathways in a controlled study [29]. |

| Small RNA / miRNA Analysis | 1 - 5 million | Fewer reads are required due to the lower complexity of the small RNA transcriptome [27]. |

Table 2: Impact of Sequencing Depth on Transcript Detection (Experimental Data)

This table summarizes findings from a controlled study that subsampled sequencing reads from rat liver samples to evaluate the impact of depth on detecting AFB1-induced differential expression [29].

| Sequencing Depth (Million Reads) | Key Findings on DEG Identification and Pathway Enrichment |

|---|---|

| 20 Million | A minimum of 20 million reads was sufficient to elicit key toxicity functions and pathways [29]. |

| 20 - 60 Million | Identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) was positively associated with sequencing depth within this range [29]. |

| > 60 Million | Benefits of increasing depth began to plateau, with diminishing returns on the detection of additional relevant pathways [29]. |

Experimental Protocols

Methodology: Evaluating Sequencing Depth Sufficiency

This protocol is adapted from a study that investigated the impact of sequencing depth on toxicological interpretation [29].

- Sample Preparation and RNA Extraction: Expose biological replicates (e.g., n=3 per condition) to the toxicant/condition of interest and a vehicle control. Extract total RNA using a standardized method. Assess RNA integrity (e.g., RIN) and purity (e.g., A260/280 ratio) prior to library preparation [28] [29].

- Library Preparation and Deep Sequencing: Prepare RNA-seq libraries using a stranded, ribosomal depletion protocol to retain information on non-polyadenylated transcripts and minimize bias. Sequence all libraries to a very high depth (e.g., 100-150 million paired-end reads) to create a "ground truth" dataset [29] [30].

- Data Subsampling: Use bioinformatics tools (e.g., the Picard

DownsampleSammodule) to create in-silico subsampled datasets from the original high-depth BAM files. Typical subsampling depths include 20, 40, 60, and 80 million reads [29]. - Differential Expression and Pathway Analysis: Perform differential gene expression analysis on each subsampled dataset and the full dataset using a standardized pipeline (e.g., HISAT2 for alignment, featureCounts for quantification, and DESeq2 for statistical analysis). Identify Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) and perform pathway enrichment analysis (e.g., using GO or KEGG) for each depth [29] [30].

- Saturation Analysis: Compare the lists of DEGs and enriched pathways across the different sequencing depths. The point at which adding more reads yields minimal new high-confidence DEGs or key biological pathways indicates a sufficient sequencing depth for your experimental system [29].

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Fig 1. Low Transcript Detection Troubleshooting

Fig 2. RNA-seq Workflow for Low-Abundance Transcripts

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Ribosomal Depletion Kits | Removes abundant rRNA, increasing sequencing capacity for messenger and other non-coding RNAs. Essential for degraded samples, bacterial RNA, or when studying non-polyadenylated transcripts [30]. |

| Stranded Library Prep Kits | Preserves information on the originating DNA strand, enabling accurate quantification of antisense transcripts and genes with overlapping genomic loci [30]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short, random nucleotide sequences used to tag individual RNA molecules before PCR amplification. This allows for bioinformatic correction of PCR duplication bias, providing more accurate digital counts of transcript abundance [16]. |

| Thermostable Reverse Transcriptase | Enzymes that withstand higher reaction temperatures (e.g., 50°C or more). This helps denature RNA secondary structures that can cause reverse transcription to stall, leading to truncated cDNA and 3'-bias, thereby improving library complexity [28]. |

| RNase Inhibitors | Protects RNA templates from degradation during the reverse transcription and library preparation process, which is critical for maintaining the integrity of full-length transcripts [28]. |

| DNase Treatment Kits | Removes contaminating genomic DNA from RNA samples prior to reverse transcription, preventing false-positive signals and nonspecific amplification in downstream applications [28]. |

Advanced Methods for Enhanced Detection: From Library Prep to Bioinformatics

In the field of transcriptomics, accurately detecting and quantifying low-abundance transcripts remains a significant challenge. These rare transcripts, which can include key regulatory genes, mutation-bearing variants, or emerging biomarkers, are often masked by technical noise or more abundant RNA species. The choice between total RNA-seq (whole transcriptome sequencing) and targeted RNA-seq panels is pivotal and depends directly on the research goals, sample characteristics, and available resources. This guide provides a structured comparison and troubleshooting resource to help researchers and drug development professionals select and optimize the right RNA-seq method for their work on rare transcripts.

FAQ: RNA-seq Method Selection

1. What is the primary consideration when choosing a method for rare transcript detection? The decision hinges on the trade-off between discovery and sensitivity. Total RNA-seq is a discovery-oriented tool that profiles all RNA species without prejudice, making it ideal for identifying novel transcripts [31]. In contrast, targeted RNA-seq is a hypothesis-driven tool that focuses sequencing power on a pre-defined set of genes, resulting in much higher sensitivity and quantitative accuracy for those targets [31] [32].

2. My total RNA-seq experiment failed to detect my rare transcript of interest. What went wrong? This is a common limitation of total RNA-seq known as the "gene dropout" problem [31]. Due to the limited starting RNA in a sample and the need to spread sequencing reads across the entire transcriptome, coverage for any single gene—especially low-abundance ones—is inherently shallow. Targeted RNA-seq is specifically designed to overcome this by concentrating sequencing depth on your genes of interest, dramatically increasing the likelihood of detection [31] [32].

3. Can I use targeted RNA-seq for exploratory research where I don't have a pre-defined gene list? No. The principal drawback of targeted RNA-seq is its complete blindness to any gene not included in the pre-defined panel [31]. Its power comes from this focus, but it means you will miss unexpected findings, novel transcripts, or expression changes in genes outside your panel. For exploratory research, total RNA-seq is the required starting point.

4. How does sample quality impact the choice of method? Sample quality is a critical factor. Total RNA-seq, particularly protocols relying on poly(A) selection, generally requires high-quality, intact RNA [30] [33]. For degraded samples, such as those from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue, targeted RNA-seq panels or whole transcriptome protocols using ribosomal RNA depletion can be more robust, as they can be designed to target shorter fragments [34] [33].

Technical Comparison: Total RNA-seq vs. Targeted RNA-seq

Table 1: A side-by-side comparison of the two primary RNA-seq methodologies for rare transcript analysis.

| Feature | Total RNA-Seq (Whole Transcriptome) | Targeted RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Unbiased discovery and mapping [31] | Sensitive validation and quantification [31] |

| Thesis Context for Rare Transcripts | Can identify novel rare transcripts; limited by dropout for low-abundance targets [31] | Excellent for quantifying known rare transcripts; cannot discover new ones [32] |

| Sensitivity & Dynamic Range | Lower sensitivity for rare transcripts due to shallow coverage [31] | High sensitivity and large dynamic range due to deep, focused coverage [31] [32] |

| Cost & Scalability | Higher cost per sample for equivalent depth on targets; less scalable for large cohorts [31] | More cost-effective and scalable for large studies [31] [35] |

| Data Complexity | High; requires substantial computational resources and bioinformatics expertise [31] [30] | Lower; analysis is more streamlined and accessible [31] |

| Ideal Application Phase | Initial target discovery, building cell atlases, exploratory research [31] | Target validation, clinical biomarker screening, drug development [31] |

Table 2: A summary of alternative RNA analysis methods and their positioning.

| Feature | Total RNA-Seq | NanoString nCounter | Targeted RNA-Seq Panels |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coverage | Entire transcriptome | Selected genes (few hundred) | Predefined genes |

| Sensitivity | High (but limited for rare transcripts) | Moderate to High | High |

| Cost | High | Moderate | Moderate to Low |

| Ease of Use | Complex (requires NGS) | Simple (no sequencing) | Moderate (requires NGS) |

| Best For | Discovery, novel transcripts | Validation, focused studies with low resources | Focused, sensitive analysis of known targets [35] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Detection of Rare Transcripts in Total RNA-seq

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Insufficient Sequencing Depth

- Solution: Increase the total number of sequencing reads per sample. While expensive, this is the most direct way to improve detection of lowly expressed genes. Generate saturation curves to determine the optimal depth for your system [30].

- Cause: Inefficient mRNA Capture

- Solution: Optimize library preparation protocols. Consider using unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to correct for PCR amplification bias and more accurately quantify transcript counts.

- Cause: Transcripts Degraded by Nonsense-Mediated Decay (NMD)

- Solution: Treat cells with an NMD inhibitor, such as cycloheximide (CHX), prior to RNA extraction. This prevents the degradation of transcripts containing premature termination codons, allowing for their detection [36]. Always include an internal control like SRSF2 to confirm NMD inhibition efficacy.

Issue 2: High Background Noise in Targeted RNA-seq

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Off-Target Probe Hybridization

- Solution: Redesign capture probes or primers with stricter bioinformatic criteria to improve specificity. Optimize hybridization conditions (e.g., temperature, salt concentration) to enhance stringency [32].

- Cause: PCR Amplification Artifacts

- Solution: Use PCR protocols with reduced cycles and high-fidelity polymerases. Employ probe-based or molecular barcode-based enrichment methods, which can be more specific than multiplex PCR and reduce background [32].

Experimental Protocols for Enhanced Rare Transcript Detection

Protocol 1: NMD Inhibition for Detecting Unstable Transcripts

This protocol is critical for detecting rare transcripts that are degraded by the nonsense-mediated decay pathway, a common issue in rare genetic disorders and cancer [36].

- Cell Culture: Culture peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or other relevant cell lines in standard conditions.

- Inhibition: Treat cells with Cycloheximide (CHX) at a final concentration of 100 µg/mL for 4-6 hours to inhibit NMD.

- RNA Extraction: Lyse cells and extract total RNA using a column-based or phenol-chloroform method.

- Quality Control: Assess RNA integrity (RIN > 8.0 is ideal) and concentration using a Bioanalyzer or similar instrument.

- Validation: Confirm successful NMD inhibition by RT-qPCR for a known NMD-sensitive transcript, such as SRSF2. A significant increase in the NMD-sensitive isoform of SRSF2 in treated vs. untreated samples indicates effective inhibition [36].

Protocol 2: Targeted RNA-seq via Hybridization Capture

This workflow is optimized for formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples but is broadly applicable for sensitive rare transcript detection [34] [32].

- RNA Extraction & Fragmentation: Extract total RNA. Fragment RNA using controlled ultrasonication or enzymatic digestion to an average size of 100-500 bp.

- Library Construction: Convert fragmented RNA into double-stranded cDNA. Ligate Illumina-compatible adapters.

- Hybridization Capture: Hybridize the library with a pool of biotinylated DNA or RNA probes (e.g., from the Illumina TruSight RNA Fusion Panel) that target your genes of interest [34].

- Enrichment: Capture probe-bound fragments using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads. Wash stringently to remove non-specifically bound fragments.

- Amplification & Sequencing: Perform a limited-cycle PCR to amplify the enriched library. Sequence on an appropriate Illumina platform (e.g., MiSeq, NextSeq) to a depth of 3-5 million reads per sample as a starting point [34].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points and workflows for selecting and implementing the appropriate RNA-seq method.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Kits

Table 3: Key research reagents and kits for RNA-seq studies of rare transcripts.

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Cycloheximide (CHX) | Inhibits nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) | Allows detection of unstable, disease-associated rare transcripts that would otherwise be degraded [36]. |

| Illumina TruSight RNA Fusion Panel | Targeted panel for enrichment of 507 fusion-associated genes. | Highly sensitive detection of rare fusion transcripts in cancer from FFPE RNA [34]. |

| Strand-Specific Library Prep Kits | Preserves information on the originating DNA strand. | Crucial for accurate annotation of antisense transcripts and overlapping genes, resolving complex rare transcript signatures [30]. |

| Ribo-Depletion Kits | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA. | Essential for total RNA-seq of degraded samples (e.g., FFPE) or samples where poly(A) selection is unsuitable, preserving more transcript diversity [30] [33]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Tags individual RNA molecules before amplification. | Corrects for PCR duplication bias, enabling absolute quantification and improving accuracy for rare transcript measurement [6]. |

FAQ: Handling Low Input and Degraded Samples

Q1: Which library prep method is best for low-input samples or those with degraded RNA?

For samples with low RNA integrity or quantity, the choice of library preparation method is critical. Poly(A) selection methods, which rely on an intact poly-A tail, are not suitable for degraded samples (e.g., FFPE) [37] [38]. In these cases, rRNA depletion using an RNase H-based method is strongly recommended [38]. This method uses DNA probes that hybridize to rRNA, followed by RNase H digestion to remove the rRNA, thereby enriching for mRNA without requiring a poly-A tail [37] [38]. Furthermore, specific low-volume protocols like SHERRY have been developed that are optimized for inputs as low as 200 ng of total RNA and are more economical for gene expression quantification [39].

Q2: How can I improve the detection of low-abundance transcripts?

Detecting low-abundance transcripts is a common challenge, especially in single-cell RNA-seq or with suboptimal samples. Key strategies include:

- Increase Sequencing Depth: Deeper sequencing provides greater coverage, helping to capture rare transcripts, though cost must be considered [40].

- Use Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): UMIs correct for amplification bias and provide more accurate counts of individual mRNA molecules, which is crucial for quantifying low-expression genes [16].

- Optimized Amplification: Methods like SMART (Switching Mechanism at 5' End of RNA Template) technology offer higher sensitivity and can better detect low-abundance transcripts by using template-switching reverse transcription [16].

- rRNA Depletion: As mentioned above, removing abundant ribosomal RNA significantly increases the proportion of informative reads, making the detection of rare transcripts more cost-effective [38].

Q3: Why is my rRNA content still high after depletion, and how can I troubleshoot this?

High residual rRNA after depletion can result from several factors. The RNase H depletion method is generally more reproducible, though its enrichment for non-rRNA content might be more modest compared to other methods like probe hybridization [38]. To troubleshoot:

- Verify RNA Quality: Ensure your RNA has not been extensively degraded.

- Check Probe Specificity: Confirm that the depletion probes are specific and comprehensive for your sample species [38].

- Optimize Hybridization Conditions: Precisely follow protocol instructions for hybridization time and temperature to ensure efficient probe binding [37].

Q4: What are the key differences between stranded and non-stranded libraries?

The choice between stranded and non-stranded libraries depends on your research question.

- Stranded Libraries: These preserve the information about which DNA strand the transcript originated from. This is critical for identifying antisense transcription, accurately defining overlapping genes, and correctly assigning reads to the correct strand of non-coding RNAs [37] [38]. They are often constructed by incorporating dUTP during second-strand synthesis, which allows for enzymatic degradation of that strand later [37].

- Non-Stranded Libraries: These are simpler, cheaper, and can work with lower RNA input, but they lose strand-of-origin information [38].

For a comprehensive transcriptome analysis, particularly when studying novel transcripts or complex genomes, stranded libraries are preferred [38].

Troubleshooting Guide for Common Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Library Complexity | Insufficient RNA input, RNA degradation, or over-amplification [16]. | Use UMIs to correct amplification bias [16]. Verify RNA Integrity Number (RIN > 7) before library prep [38]. |

| High rRNA Background | Inefficient rRNA depletion, especially with degraded samples or wrong probe set [38]. | Use RNase H-based rRNA depletion for degraded samples [38]. Ensure species-specific probes are used [37]. |

| 3' Bias in Coverage | RNA degradation or using a protocol that fragments cDNA after reverse transcription with oligo(dT) primers [37]. | Fragment the mRNA before reverse transcription for more uniform coverage [37]. Use high-quality RNA (RIN ≥ 8) [37]. |

| Batch Effects | Technical variation from processing samples in different batches or on different days [41] [16]. | Randomize samples across library prep batches. Use batch correction algorithms (e.g., Combat, Harmony) during data analysis [16]. Include spike-in controls [41]. |

rRNA Depletion via RNase H Digestion

This methodology is key for working with degraded samples or non-polyadenylated RNA [38].

- Hybridization: DNA oligonucleotides (probes) are hybridized to the target rRNA sequences in the total RNA sample [37].

- Digestion: The enzyme RNase H is added, which specifically cleaves the RNA strand in an RNA-DNA hybrid [37] [38].

- Purification: The digested rRNA fragments are removed, leaving behind an enriched pool of mRNA and other non-ribosomal RNAs [37].

- Library Construction: The enriched RNA proceeds to standard library prep steps, typically involving RNA fragmentation, reverse transcription, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification [37].

Low-Input and Automated Protocols

For precious low-volume samples, consider:

- SHERRY Protocol: A 3'-end RNA-seq method that starts with 200 ng total RNA. It involves direct tagmentation of RNA/cDNA hybrids, eliminating the need for second-strand synthesis, which saves time and reduces biases [39].

- Automation: Liquid handling robots can be used to automate library prep (e.g., using the NEBNext kit on a Biomek i7 workstation). This significantly increases throughput, reduces hands-on time from 2 days to 9 hours for 84 samples, and enhances reproducibility by minimizing human error [42].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a generalized RNA-seq library preparation workflow, highlighting key decision points for handling challenging samples.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and their functions for optimizing library preparation for challenging samples.

| Reagent / Kit | Function in Protocol | Key Consideration for Low-Abundance Transcripts |

|---|---|---|

| RNase H Depletion Kit [37] [38] | Removes ribosomal RNA via DNA probe hybridization and enzymatic digestion. | Essential for degraded samples; increases useful sequencing reads for rare transcripts [38]. |

| Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads [37] | Purifies polyadenylated mRNA from total RNA. | Avoid with degraded RNA; causes 3' bias and loss of transcripts [37]. |

| rRNA Depletion Probes [37] [38] | Species-specific DNA probes that target rRNA for removal. | Must match the species of study; off-target effects can deplete genes of interest [38]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) [16] | Molecular barcodes for individual mRNA molecules. | Corrects amplification bias, providing absolute counts vital for low-abundance genes [16]. |

| DNase I [39] | Digests genomic DNA during RNA purification. | Prevents background from gDNA, ensuring reads originate from RNA [39]. |

| Stranded Library Prep Kit [37] | Preserves strand information (e.g., via dUTP incorporation). | Crucial for accurate annotation and discovery of antisense transcripts [37] [38]. |

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) research, the accurate detection of low-abundance transcripts is a significant challenge, particularly in samples with high concentrations of globin mRNA or ribosomal RNA (rRNA). These highly abundant RNA species can consume the majority of sequencing reads, dramatically reducing the coverage of informative, protein-coding transcripts and compromising data quality. Effective depletion strategies are therefore essential for researchers aiming to maximize sequencing economy and obtain biologically meaningful gene expression data, especially from complex sample types like whole blood.

FAQ: Understanding Depletion Methods

1. What is the primary difference between probe hybridization and RNase H enzymatic depletion methods?

Probe hybridization methods use specifically designed DNA oligonucleotides that bind to targeted RNA sequences (like globin mRNA or rRNA), followed by their removal via enzymatic degradation or magnetic bead purification. In contrast, RNase H-based enzymatic depletion methods directly digest the RNA:DNA hybrids formed when DNA oligonucleotides bind to their target RNAs [43].

2. Which depletion method performs better for whole blood transcriptome studies?

Comparative studies have demonstrated that probe hybridization methods generally outperform RNase H enzymatic depletion for mRNA sequencing from whole blood samples. This superiority is evidenced by:

- Detection of a higher number of genes and transcripts

- More uniform coverage across the entire gene body without 3' bias

- Generation of significantly more junction reads (37-40% vs 25-36% of total mapped reads)

- Higher correlation between replicates (R > 0.9 vs R > 0.85) [43]

3. Can I use the same globin depletion kit for human, mouse, and rat blood samples?

Yes, many commercial globin depletion kits are designed to support multiple species. For example, the TruSeq Stranded Ribo-Zero Globin kit is validated for human, mouse, and rat samples, and may be compatible with other species as well [44].

4. How much does globin depletion improve sequencing efficiency in blood samples?

In whole blood samples, globin genes typically comprise 70-90% of total RNA transcripts. Effective depletion methods can reduce this to below 1% of total mapped reads, thereby dramatically increasing the proportion of sequencing reads available for detecting informative transcripts [43].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High globin/rRNA reads after depletion | Insufficient depletion reaction, degraded reagents, incorrect protocol | Verify reagent concentrations and storage conditions; ensure proper reaction conditions and timing; include positive controls [43] |

| 3' bias in gene coverage | RNA degradation during depletion, especially with enzymatic methods | Use probe hybridization methods; minimize processing time; add DNaseI treatment for additional cleanup [43] |

| Low RNA recovery after depletion | Excessive cleanup steps, bead loss during separation | Allow complete bead separation before supernatant removal; use strong magnetic devices; optimize wash conditions [43] [45] |

| High background in negative controls | Contamination during library preparation | Maintain separate pre- and post-PCR workspaces; use clean room with positive air flow; wear appropriate protective equipment [45] |

Quantitative Comparison of Depletion Methods

Table 1: Performance metrics of different depletion methods for whole blood RNA-seq [43]

| Method Type | Specific Kit | Globin Read Percentage | Junction Reads (%) | 3' Bias | Genes Detected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probe Hybridization | GLOBINClear | 0.5% (±0.6%) | 37-40% | No | 22,228 |

| Probe Hybridization | Globin-Zero Gold (GZr) | <1% | 37-40% | No | 21,766 |

| RNase H Enzymatic | Ribo-Zero Plus (RZr) | <1% | 31-32% | Yes | 21,736 |

| RNase H Enzymatic | NEBNext Globin & rRNA | 6.3% (±2.3%) | 25-36% | Yes | Excluded due to high globin |

Table 2: Impact of depletion on blood RNA-seq metrics [43]

| Metric | Without Depletion | With Effective Depletion |

|---|---|---|

| Globin reads | 70-90% of total RNA | <1% of total mapped reads |

| Informative reads | 10-30% | >90% |

| Junction reads | Limited | 37-40% of total mapped reads |

| Detected transcripts | Reduced | 78,526-85,979 |

| Gene coverage | Severe 3' bias | Uniform coverage |

Experimental Protocols for Optimal Depletion

Recommended Workflow for Whole Blood RNA-seq

Detailed Depletion Protocol Using Probe Hybridization

Sample Requirements:

- Input: 1 μg high-quality total RNA from whole blood (RIN > 7.5)

- Sample Preparation: Include positive controls (10-100 pg control RNA) and negative controls (mock FACS buffer) [45]

Procedure:

- DNaseI Treatment: Treat extracted RNA with DNaseI for additional cleanup before depletion

- Probe Hybridization:

- Incubate RNA with biotinylated DNA oligonucleotides targeting globin transcripts and rRNA

- Use appropriate hybridization buffer and conditions according to kit specifications

- Removal of Hybridized Complexes:

- Add streptavidin-coated magnetic beads to capture biotinylated probe:RNA complexes

- Incubate with gentle mixing to ensure complete binding

- Purification:

- Place tube on magnetic stand until solution clears

- Carefully transfer supernatant containing depleted RNA to a new tube

- Perform additional bead cleanup if specified in protocol [43]

Quality Control:

- Assess depleted RNA using BioAnalyzer 2100 high sensitivity DNA chip

- Expected yield: 150-200 ng recovered RNA

- Verify depletion efficiency: globin reads should be <1% of total mapped reads in subsequent sequencing [43]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key reagents for effective rRNA and globin depletion

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probe Hybridization Kits | GLOBINClear, Globin-Zero Gold | Remove globin mRNA/rRNA via targeted probes | Better for full-length transcript preservation; higher RNA recovery |

| Enzymatic Depletion Kits | NEBNext Globin & rRNA, Ribo-Zero Plus | RNase H digestion of target RNAs | Faster processing; may cause RNA degradation |

| RNA Stabilization | PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes | Preserve RNA integrity during collection | Critical for accurate expression profiling |

| Quality Assessment | BioAnalyzer, RIN scores | Evaluate RNA integrity pre-depletion | RIN >7.5 recommended for optimal results |

| Library Prep | Stranded mRNA-Seq with poly-A+ selection | Final library construction | Enriches for protein-coding genes after depletion |

Advanced Applications and Integration Strategies

Combining Depletion with Single-Cell RNA-seq

For single-cell RNA-seq studies involving erythroid cells or blood samples, specialized approaches are required:

- Targeted insulin transcript depletion has been successfully used in pancreatic islet studies to enhance detection of lower abundance transcripts [46]

- Cell sorting optimization: Resuspend cells in EDTA-, Mg2+- and Ca2+-free PBS or appropriate sorting buffer to maintain RNA integrity [45]

- Minimize processing time: Process cells immediately after collection or snap-freeze in dry ice to prevent RNA degradation [45]

Integration with Long-Read Sequencing Technologies

Long-read RNA sequencing technologies present both opportunities and challenges for depletion strategies:

- Full-length transcript information enables comprehensive isoform detection but requires high-quality, depleted RNA [46]

- Advanced computational tools like TranSigner can improve transcript identification and quantification from long-read data after depletion [47]

- Error rates in long-read technologies (e.g., Oxford Nanopore) necessitate optimal starting RNA quality achieved through effective depletion [47]

Multi-Omics Integration for Comprehensive Analysis

The true power of depletion-enhanced RNA-seq emerges when integrated with other data modalities:

- Combined with epigenetic data: Depletion-enabled transcriptome profiles can be correlated with chromatin immunoprecipitation data to understand gene regulation mechanisms [48]

- Parallel protein profiling: Integrated analysis with protein expression data provides systems-level insights

- Time-course experiments: Monitor transcriptome dynamics during processes like erythroid differentiation of CD34+ cells [48]

Effective rRNA and globin depletion is not merely a technical prerequisite but a fundamental determinant of success in RNA-seq studies focusing on low-abundance transcripts. The choice between probe hybridization and enzymatic methods should be guided by experimental priorities—with probe hybridization generally providing superior sensitivity and coverage uniformity for transcript detection. By implementing the optimized protocols, troubleshooting strategies, and quality control measures outlined in this guide, researchers can dramatically enhance their sequencing economy and uncover biological insights that would otherwise remain obscured by highly abundant RNA species.

Incorporating Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) to Correct for Amplification Bias and PCR Duplicates

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why are UMIs particularly important for studying low abundance transcripts? UMIs are crucial for low abundance transcripts because these transcripts are more susceptible to being obscured by amplification bias and PCR duplicates. In standard RNA-seq, a single, rare transcript amplified many times can be mistaken for multiple abundant transcripts, leading to inaccurate quantification. UMIs allow you to distinguish the original molecules, ensuring that the count of a transcript reflects its true biological abundance rather than PCR artifacts. This is essential for achieving the sensitivity required to detect and quantify rare transcripts accurately [49] [50].